Abstract

An elevated resting heart rate (RHR) is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified > 350 loci. Uniquely, in this study we applied genetic fine-mapping leveraging tissue specific chromatin segmentation and colocalization analyses to identify causal variants and candidate effector genes for RHR. We used RHR GWAS summary statistics from 388,237 individuals of European ancestry from UK Biobank and performed fine mapping using publicly available genomic annotation datasets. High-confidence causal variants (accounting for > 75% posterior probability) were identified, and we collated candidate effector genes using a multi-omics approach that combined evidence from colocalisation with molecular quantitative trait loci (QTLs), and long-range chromatin interaction analyses. Finally, we performed druggability analyses to investigate drug repurposing opportunities. The fine mapping pipeline indicated 442 distinct RHR signals. For 90 signals, a single variant was identified as a high-confidence causal variant, of which 22 were annotated as missense. In trait-relevant tissues, 39 signals colocalised with cis-expression QTLs (eQTLs), 3 with cis-protein QTLs (pQTLs), and 75 had promoter interactions via Hi-C. In total, 262 candidate genes were highlighted (79% had promoter interactions, 15% had a colocalised eQTL, 8% had a missense variant and 1% had a colocalised pQTL), and, for the first time, enrichment in nervous system pathways. Druggability analyses highlighted ACHE, CALCRL, MYT1 and TDP1 as potential targets. Our genetic fine-mapping pipeline prioritised 262 candidate genes for RHR that warrant further investigation in functional studies, and we provide potential therapeutic targets to reduce RHR and cardiovascular mortality.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00439-024-02684-z.

Introduction

An elevated resting heart rate (RHR) has been associated with an increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality independent of traditional risk factors (Zhang et al. 2016). Reduction of heart rate using pharmacological intervention is an important component of therapy of a number of cardiovascular conditions including angina pectoris and heart failure. For example, direct inhibition of the pacemaker current with ivabradine reduces cardiovascular events in heart failure (Cargnoni et al. 2006), suggesting that RHR is a modifiable risk factor. However, the exact mechanisms linking RHR to risk are still not clear.

Genetics contributes to up to 20% of the interindividual variance in RHR (van de Vegte et al. 2023) and, at present, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and exome-array wide association studies have identified > 350 loci for RHR explaining > 5% of this variance (den Hoed et al. 2013; Eijgelsheim et al. 2010; Eppinga et al. 2016; Guo et al. 2019; van de Vegte et al. 2023; van den Berg et al. 2017). The underlying effector genes remain unknown for most of these loci, which limits our understanding of the genetic and biological mechanisms of RHR. Utilising a fine-mapping approach could identify responsible effector genes and biological pathways explaining the mechanisms underlying RHR and its relation to cardiovascular risk, as well as novel therapeutic targets.

One promising avenue to improve prioritization of causal variants and candidate genes is the integration of GWAS with functional genomic information data to fine map GWAS loci. Previous studies have shown it can substantially improve the causal-variant resolution for risk loci for Type-2 diabetes (Mahajan et al. 2018) and blood pressure(van Duijvenboden et al. 2023). These studies leveraged European ancestry GWAS to avoid the calibration issues of fine-mapping across multi-ancestry meta-analysis GWAS (Kanai et al. 2022).

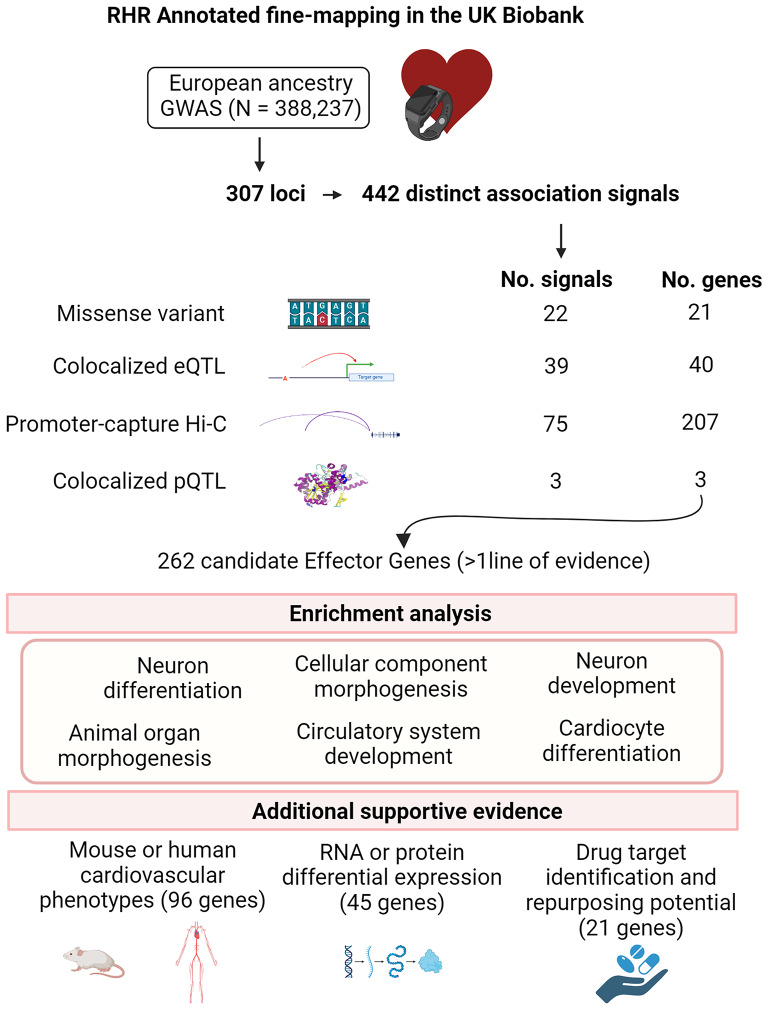

In the present work, we performed an annotation-informed fine-mapping analysis using a European ancestry GWAS to identify causal variants and candidate effector genes for RHR. Prioritisation of candidate effector genes was based on evidence from functional annotation, colocalisation analyses with expression and protein quantitative trait loci (eQTLs and pQTLs) and promoter capture Hi-C interactions in relevant RHR tissues. We investigated the biological pathways of the prioritised effector genes. We also investigated additional evidence of support for effector genes from mouse and human phenotypes and differential expression. Finally, we assessed the potential of the prioritised effector genes for drug target identification and repurposing opportunities. An overview of the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the study and summary of main findings. Created with BioRender.com. eQTL, expression quantitative locus; GWAS, genome-wide association study; Hi-C, long-range chromatin interaction; pQTL, protein quantitative locus; RHR, resting heart rate; RNA, ribosomal nucleic acid

Methods

Identification of distinct associations signals for fine-mapping

We conducted a fine-mapping analysis of RHR GWAS summary statistics of 388,237 individuals of European ancestry from UK Biobank (Mensah-Kane et al. 2021). The work was undertaken as part of UK Biobank application 8256. We initially defined loci as mapping 500 kb up- and down-stream of each lead SNV (at genome-wide significance, P < 5 × 10− 8). Where loci boundaries overlapped, they were combined as a single locus. We then performed approximate conditional analyses using GCTA-COJO(Yang et al. 2012) to detect distinct association signals at each locus using unrelated individuals with European ancestry as a reference for linkage disequilibrium (LD). Within each locus, variants attaining genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10− 8) in the joint GCTA-COJO model were selected as index SNVs for distinct association signals.

Enrichment of RHR associations for genomic annotations

We used fGWAS(Pickrell 2014) to identify genomic annotations from a total of 253 functional and regulatory annotations (via GENCODE and Roadmap Epigenomics)(Harrow et al. 2012; Kundaje et al. 2015) that were enriched for RHR association signals (Supplemental Methods). We then used an iterative approach to identify a joint model of enriched annotations using a forward-selection approach. At each iteration, we added the annotation to the joint fGWAS model that maximised the improvement in the penalised likelihood. We continued until no additional annotations improved the fit of the joint model (P < 0.00020, Bonferroni correction for 253 annotations).

Fine-mapping distinct association signals for RHR

For each  th variant at the

th variant at the  th distinct signal, we first estimated its prior probability of causality using an annotation-informed prior model:

th distinct signal, we first estimated its prior probability of causality using an annotation-informed prior model:

|

,

where the summation is over the enriched annotations,  is the estimated log-fold enrichment of the

is the estimated log-fold enrichment of the  th annotation from the final joint fGWAS model, and

th annotation from the final joint fGWAS model, and  is an indicator variable taking the value 1 if the

is an indicator variable taking the value 1 if the  th variant maps to the

th variant maps to the  th annotation, and 0 otherwise. We then approximated the Bayes’ factor,

th annotation, and 0 otherwise. We then approximated the Bayes’ factor,  , using the European ancestry summary statistics, as previously described(van Duijvenboden et al. 2023) (Supplemental Methods). Finally, we estimated the

, using the European ancestry summary statistics, as previously described(van Duijvenboden et al. 2023) (Supplemental Methods). Finally, we estimated the  th variant posterior probability of causality as

th variant posterior probability of causality as  .

.

Next, we derived a 99% credible set for the  th distinct association signal by: (i) ranking all SNVs according to

th distinct association signal by: (i) ranking all SNVs according to  ; and (ii) including ranked variants until their cumulative posterior probability attains or exceeds 99%(van Duijvenboden et al. 2023). The credible set would, then, include the minimum number of variants that jointly explained ≥ 99% of the posterior probability of driving the RHR association under the annotation-informed prior. We defined high-confidence causal variants as single variants from the credible sets accounting for more than 75% of the posterior probability.

; and (ii) including ranked variants until their cumulative posterior probability attains or exceeds 99%(van Duijvenboden et al. 2023). The credible set would, then, include the minimum number of variants that jointly explained ≥ 99% of the posterior probability of driving the RHR association under the annotation-informed prior. We defined high-confidence causal variants as single variants from the credible sets accounting for more than 75% of the posterior probability.

Functional annotation of variants

We used variant-effect predictor (VEP) analysis(McLaren et al. 2016) to annotate the high-confidence causal variants from the credible sets, and selected those annotated as missense variants.

Colocalisation with gene expression data

We integrated genetic fine-mapping data with cis-eQTL in adrenal gland, artery, heart, nerve and brain tissues from the GTEx Consortium version 8 (tissue selection was informed by tissue enrichment analysis from prior GWAS(Eppinga et al. 2016) and biological mechanisms known to regulate RHR, Supplemental Methods). We first did a lookup of significant lead eQTL variants in the 99% credible sets. For each signal where we detected overlap, we formally assessed whether the annotation informed Bayes’ factor for the credible set variants of the corresponding signal colocalised with the eQTL results, as previously described(van Duijvenboden et al. 2023).

Long-range chromatin interaction (Hi–C) analyses

We identified potential target genes of regulatory SNVs using long-range chromatin interaction (Hi–C) data from adrenal gland, aorta, left and right ventricles, hippocampus and cortex(Jung et al. 2019) - similar tissues as selected for eQTL analysis. Hi–C data was corrected for genomic biases and distance using the Hi–C Pro and Fit-Hi-C pipelines according to Schmitt et al(Schmitt et al. 2016). From the Hi–C data, we report the target genes with which these high regulatory potential SNVs interact (Supplemental Methods).

Colocalisation with protein expression data

We additionally integrated genetic fine-mapping data with protein quantitative trait loci (cis-pQTL) in plasma(Ferkingstad et al. 2021). We performed the same Bayesian statistical procedure as for eQTL colocalisation to assess whether those signals for which a 99% credible set variant was the lead pQTL variant, colocalised with pQTL results.

Prioritisation of candidate effector RHR genes

A full list of candidate effector genes for RHR was collated from the results of our fine-mapping pipeline and computational approaches, similar to our studies on blood pressure as reported recently(van Duijvenboden et al. 2023). A gene was indicated for a signal if there was support from a coding and high-confidence variant in the gene at the locus, or if the gene was indicated from eQTL, pQTL colocalization or promoter capture Hi-C analyses.

Effector gene pathway analysis

We used the Gene2Function analysis tool in FUMA (v1.4.0) to perform gene set enrichment on the prioritised list of candidate genes, and to identify significantly associated Gene Ontology (GO) terms and pathways(Watanabe et al. 2017). Redundant GO terms were removed using the Reduce and Visualize Gene Ontology (REVIGO) web application(Supek et al. 2011). Dispensability cut off < 0.7 was used in this analysis to remove redundant terms.

Additional evidence for effector genes from mouse and human phenotypes and differential expression

We collated additional information for each prioritised candidate gene using data from GeneCards (https://genealacart.genecards.org). This included evidence from mouse model phenotypes, from the Human Phenotype Ontology database, from differential RNA and protein expression of the candidate gene in the GTEx database in cardiovascular tissues (Supplemental Methods).

Druggability of prioritised effector genes

To identify candidate druggable targets, a look-up was done of the prioritised list of candidate genes in a previously published database of the druggable genome (Finan et al. 2017). This database categorises gene targets into tiers according to whether they are existing targets of approved drugs or drugs under development (Tier 1), greater than 50% shared protein sequence identity to existing targets (Tier 2), and extracellular proteins or members of key druggable gene families not already in Tier 1 or Tier 2 (Tier 3). To identify opportunities for drug repurposing, a look-up of each candidate gene was performed for Tier 1 to identify targets of licensed medication using the KEGG drug database (Supplementary Methods). The open targets database was interrogated to identify disease associations with each gene to identify overlap that could indicate a promising drug target. To identify enrichment of candidate effector genes in clinical indication categories and potentially re-positional drugs, we utilised the Genome for REPositioning drugs (GREP) software. A pathway-set enrichment analysis was also performed using Gene2Drug to identify drug repositioning candidates. Using RHR significant GO biological processes as input, pathway expression profiles are created and ranked according to the p-value of their Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic that is used to search for drugs that up-regulate or dysregulate most pathways in the set(Napolitano et al. 2017).

Results

Fine-mapping and genomic annotation reveals high-confidence causal variants

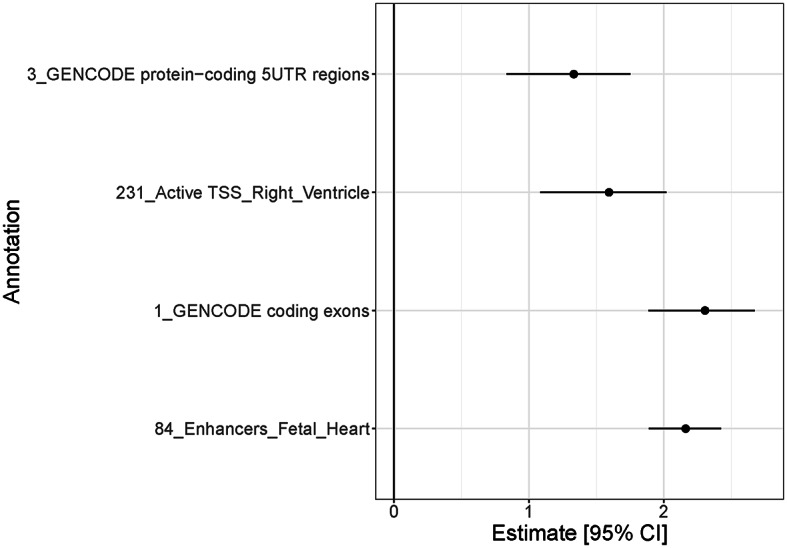

There were 307 genome-wide significant loci in the European GWAS performed by Mensah-Kane et al. (Mensah-Kane et al. 2021). We partitioned these loci into a total of 442 distinct association signals (Supplemental Table 1). We observed significant joint enrichment for RHR associations mapping to protein coding exons and 5’ UTRs, enhancers in the heart, and promoters in the right ventricle (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Results from genomic enrichment annotation for RHR. Estimate and 95% confidence interval of the log-fold enrichment at the most significant annotations for RHR, calculated using functional GWAS. UTR, untranslated region; TSS, transcription start site; RHR, resting heart rate

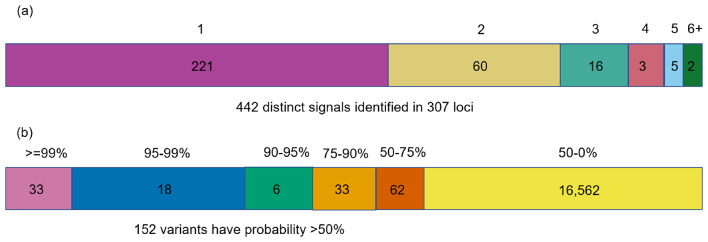

Using the enriched annotations, for each of the 442 distinct signals, we derived 99% credible sets of variants. The median 99% credible set size was 26 variants (Supplemental Table 1). For 90 (20.4%) RHR signals, a single SNV accounted for > 75% of the posterior probability of driving the RHR association under the annotation-informed prior, which we defined as “high-confidence” for causality (Fig. 3, Supplemental Table 3).

Fig. 3.

(a) Distinct RHR association signals. Summary of distinct association signals for RHR. A single signal at 221 genomic regions and at least two at 52. (b) Distribution of the posterior probability of causality of the variants in credible sets. RHR, resting heart rate

Missense variants implicate causal genes

From the 90 high-confidence variants, 22 were missense variants in 21 genes (Table 1), of which seven were annotated as damaging and deleterious by PolyPhen and SIFT, respectively.

Table 1.

High-confidence variants annotated as missense

| Missense variant | Signal ID | Sentinel SNV | Canonical transcript | Gene | CHR | BP | Amino acid change | Polyphen | SIFT | PP | MAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs709209 | 1_1 | rs709209 | ENST00000377939.4 | RNF207 | 1 | 6,278,414 | p.Asn573Ser | Ben | Tol low conf | 0.997 | 0.342 |

| rs1260326 | 34_1 | rs1260326 | ENST00000264717.2 | GCKR | 2 | 27,730,940 | p.Leu446Pro | Ben | Tol | 0.994 | 0.396 |

| rs3100246 | 35_1 | rs3100246 | ENST00000401605.1 | CLIP4 | 2 | 29,383,256 | p.Arg486Leu | Ben | Del | 0.998 | 0.152 |

| rs17362588 | 51_3 | rs17362588 | ENST00000343876.2 | CCDC141 | 2 | 179,721,046 | p.Arg379Trp | Prob Dam | Del | 0.978 | 0.088 |

| rs10497529 | 51_5 | rs10497529 | ENST00000420890.2 | CCDC141 | 2 | 179,839,888 | p.Ala141Val | Prob Dam | Del | 1.000 | 0.037 |

| rs4833772 | 96_1 | rs4833772 | ENST00000424958.1 | AC079341.1 | 4 | 122,687,491 | p.Asp98His | Unknown | - | 0.790 | 0.488 |

| rs28925904 | 97_1 | rs28925904 | ENST00000262995.4 | GAB1 | 4 | 144,359,490 | p.Pro311Leu | Poss dam | Del | 0.990 | 0.025 |

| rs2307111 | 106_1 | rs2307111 | ENST00000428202.2 | POC5 | 5 | 75,003,678 | p.His36Arg | Ben | Tol | 1.000 | 0.395 |

| rs12514461 | 108_1 | rs12514461 | ENST00000446378.2 | CMYA5 | 5 | 79,041,057 | p.Lys3583Glu | Poss dam | Tol | 0.940 | 0.116 |

| rs1015149 | 127_1 | rs9471627 | ENST00000230323.4 | TFEB | 6 | 41,658,889 | p.His21Gln | - | - | 0.803 | 0.459 |

| rs80095409 | 147_1 | rs150990106 | ENST00000393561.1 | LAMB1 | 7 | 107,600,211 | p.Arg819Gly | Prob Dam | Del | 0.709 | 0.014 |

| rs6271 | 175_2 | rs6271 | ENST00000393056.2 | DBH | 9 | 136,522,274 | p.Arg549Cys | Poss dam | Tol | 0.990 | 0.074 |

| rs7102584 | 205_3 | rs7102584 | ENST00000338350.4 | KCNJ5 | 11 | 128,782,012 | p.Gln282Glu | Ben | Tol | 0.999 | 0.018 |

| rs3184504 | 221_2 | rs10774625 | ENST00000538307.1 | SH2B3 | 12 | 111,884,608 | p.Trp60Arg | Ben | Del | 0.701 | 0.481 |

| rs12889267 | 230_1 | rs12889267 | ENST00000555038.1 | ARHGEF40 | 14 | 21,542,766 | p.Lys293Glu | Poss dam | Del | 1.000 | 0.167 |

| rs365990 | 231_1 | rs365990 | ENST00000356287.3 | MYH6 | 14 | 23,861,811 | p.Val1101Ala | Ben | Tol | 1.000 | 0.370 |

| rs5742915 | 243_4 | rs5742915 | ENST00000268058.3 | PML | 15 | 74,336,633 | p.Phe645Leu | Ben | Tol | 1.000 | 0.461 |

| rs238238 | 258_1 | rs238238 | ENST00000323997.6 | ENO3 | 17 | 4,856,376 | p.Asn71Ser | Ben | Tol low conf | 0.680 | 0.296 |

| rs61735998 | 276_3 | rs61735998 | ENST00000590592.1 | FHOD3 | 18 | 34,289,285 | p.Val822Phe | Poss dam | Del | 1.000 | 0.025 |

| rs7412 | 290_1 | rs190712692 | ENST00000252486.4 | APOE | 19 | 45,412,079 | p.Arg176Cys | Prob Dam | Del | 0.810 | 0.081 |

| rs17265513 | 297_1 | rs17265513 | ENST00000544979.2 | ZHX3 | 20 | 39,832,628 | p.Asn310Ser | Poss dam | Tol | 0.979 | 0.199 |

| rs148377517 | 298_1 | rs148377517 | ENST00000396825.3 | FITM2 | 20 | 42,939,693 | p.Met32Ile | Ben | Tol | 1.000 | 0.015 |

CHR, chromosome; BP, base pair position in human genome build 37; sentinel SNV, lead variant in the signal; Missense.variant, high-confident variant in the signal annotated as missense; PP, posterior probability of the high-confidence variant driving the association with RHR; MAF, minor allele frequency of the missense variant; Polyphen and SIFT columns indicate the consequence prediction from each tool, respectively; Tol, tolerated consequence; Del, deleterious consequence; Ben, benign consequence; Prob Dam, probably damaging consequence; Poss dam, possibly damaging consequence; conf, confidence

Four variants were annotated as probably damaging and deleterious were in CCDC141 (rs17362588, p.Arg379Trp and rs10497529, p.Ala141Val), APOE (rs7412, p.Arg176Cys), and LAMB1 (rs80095409, p.Arg819Gly), Table 1). We found two missense variants in CCDC141. This gene is involved in axon guidance and cell adhesion and plays a critical role in radial migration and centrosomal function(Saengkaew et al. 2021). It has been identified by previous analyses for RHR(van den Berg et al. 2017), RHR dynamics(Ramírez et al. 2018; Verweij et al. 2018) and sick sinus syndrome(Thorolfsdottir et al. 2021). However, there are yet no functional studies investigating the mechanistic link of CCDC141 and RHR. The APOE variant, rs7412, determines the APOE2 isoform, which has been shown in both human and animal studies to be protective against Alzheimer’s Disease and is additionally associated with longevity independent of Alzheimer’s Disease (Shinohara et al. 2020). Previous studies suggest that laminins have important roles in human heart development and function(Haag et al. 1999). In particular for LAMB1 (Laminin Subunit Beta 1) zebrafish embryos had mild morphogenetic defects and progressive cardiomegaly, as well as a limited heart size during cardiac development(Derrick et al. 2021).

Three missense variants were annotated as possibly damaging and deleterious by PolyPhen and SIFT: FHOD3 (rs61735998, p.Val822Phe), ARHGEF40 (rs12889267, p.Lys293Glu) and GAB1 (rs28925904, p.Pro311Leu). The variants in FHOD3 and ARHGEF40 had a 100% posterior probability of driving the RHR signal. FHOD3 is essential for myofibrillogenesis at an early stage of heart development(Kan-O et al. 2012) and has been identified as a causal gene for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with related heart rate abnormalities in humans (Ochoa et al. 2018). ARHGEF40 has previously been associated with all-cause mortality (Eppinga et al. 2016), but is less functionally characterised and encodes a protein similar to guanosine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho GTPases. Finally, GAB1 is an adapter protein that plays a role in intracellular signalling cascades triggered by activated receptor-type kinases (Yousaf et al. 2018). Cardiac-specific GAB1 knock-out in mice has been reported to lead to dilated cardiomyopathy associated with mitochondrial damage and cardiomyocyte apoptosis (Zhao et al. 2016).

Genes identified using gene expression in disease relevant tissues

Convincing support for colocalization with gene expression in at least one tissue was identified for 39 distinct signals at 40 genes (Supplemental Table 4). A total of 21 signals (for 21 genes) colocalised at a single tissue, 18 at heart or arterial tissue and 3 at brain. There were no specific colocalisations in adrenal gland tissues (Supplemental Fig. 1). We observed 14 signals (for 14 genes) that colocalised at more than one tissue. For the 4 remaining signals, one signal indicated two genes (AC009264.1 and CHRM2) in the heart left ventricle, there were two signals for one gene (CPNE5) in the heart left ventricle, and for the last signal two genes (FLCN and PLD6) were colocalised in multiple tissues (brain, heart and artery).

An interesting gene with heart-specific colocalisation is PLEC. PLEC knock out mouse models show right bundle branch block and abnormal heart morphology, and a missense variant in PLEC has been reported to increase risk of atrial fibrillation in humans(Thorolfsdottir et al. 2017).

There were a few genes with brain-specific colocalisations, including NKX2-5, LEMD2 and UCK1. NKX2-5’s reported function is a regulator of cardiovascular development(Bruneau 2008), with mouse and zebrafish models showing abnormalities in heart rate, among other cardiovascular phenotypes (Table 2). However, the function of NKX2-5 in the brain is not reported. There are LEMD2 mouse and human models that include an arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy phenotype(Gerull and Brodehl 2020). Finally, UCK1 phosphorylates uridine and cytidine to uridine monophosphate and cytidine monophosphate (GeneCards), but there is no data indicating association with RHR or cardiovascular phenotypes.

Table 2.

Twenty-three candidate genes for RHR with additional evidence of support from mouse or human phenotypes and RNA or protein differential expression

| Bioinformatics support | Gene | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal ID | rsID | Index SNV | Missense high-confidence SNV | eQTL colocalisation | Hi.C gene | pQTL colocalisation | |

| 28_1 | rs12724121 | 1:236852282:A: T | ACTN2(1) | ACTN2* | |||

| 51_3 | rs17362588 | 2:179721046:G: A | CCDC141 | CCDC141 | |||

| 67_1 | NA | 3:37551515:C: CT | ITGA9(1) | ITGA9 | |||

| 67_4 | rs7372712 | 3:38686192:C: T | SCN10A(1) | SCN10A* | |||

| 70_3 | rs9819463 | 3:53672471:T: C | CACNA1D(1) | CACNA1D* | |||

| 108_1 | rs12514461 | 5:79041057:A: G | CMYA5 | CMYA5 | |||

| 119_1 | rs10071514 | 5:172669771:A: G | NKX2-5(2) | NKX2-5* | |||

| 146_3 | rs13244629 | 7:100509253:A: C | ACHE(4) | ACHE* | |||

| 153_1 | rs1424569 | 7:136569416:T: C | CHRM2(1) | CHRM2* | |||

| 188_1 | rs10787270 | 10:112459906:G: A | RBM20(2) | RBM20* | |||

| 205_3 | rs7102584 | 11:128782012:C: G | KCNJ5 | KCNJ5* | |||

| 221_2 | rs10774625 | 12:111910219:A: G | SH2B3 | SH2B3(1) | SH2B3 | ||

| 231_1 | rs365990 | 14:23861811:A: G | MYH6 | MYH6* | |||

| 231_3 | rs117526881 | 14:23908895:G: C | IL25(1) | IL25 | |||

| 254_1 | rs8048448 | 16:30692208:T: C | FBXL19(5) | FBXL19 | |||

| 254_1 | rs8048448 | 16:30692208:T: C | YPEL3(2) | YPEL3 | |||

| 273_1 | rs4800401 | 18:20003625:C: T | GATA6(3) | GATA6* | |||

| 276_3 | rs61735998 | 18:34289285:G: T | FHOD3 | FHOD3* | |||

| 290_1 | rs190712692 | 19:45425178:G: A | CKM(1) | CKM | |||

| 296_1 | rs6123471 | 20:36840156:T: C | GHRH(1) | GHRH | |||

| 296_1 | rs6123471 | 20:36840156:T: C | TGM2(1) | TGM2* | |||

| 298_1 | rs148377517 | 20:42939693:C: T | FITM2 | FITM2 | |||

| 305_1 | rs749085725 | 22:20098887:CT: C | SCARF2(1) | SCARF2 | |||

Signal.ID, distinct signal identifier, based on the locus number and signal number within the locus; rsID, rsID of the lead SNV in the signal; Index.SNV, chromosome: base pair in build 37:reference allele: other allele; SNV, single-nucleotide variant; eQTL, expression quantitative locus; Hi.C, long-range high-chromatin interaction; pQTL, protein quantitative locus. The number in brackets in the eQTL and Hi.C columns indicate the number of tissues at which we found support. *Indicates there is a mouse or human abnormal heart rate phenotype, as indicated in Supplementary Table 7

Identification of genes using long-range chromatin interactions

Promoter interactions were identified for 75 distinct signals mapping to 207 genes at 66 loci (Supplemental Table 5). A total of 107 genes were indicated in a single tissue, of which 14 (13%) were in left or right ventricle, 83 (78%) in brain, and 10 (9%) in the adrenal gland. From the genes specifically indicated in heart tissue, SCN10A has been thoroughly characterised as a RHR modifier(Eppinga et al. 2016; Ramírez et al. 2018)Table 2) and CASZ1 is involved in cardiac morphogenesis and development, and there are abnormal mouse phenotypes including congenital and structural cardiomyopathies(Spielmann et al. 2022). There are also some genes that do not have experimental support for cardiovascular traits, these include CABLES1, BET1 and SLC22A17. CABLES1 encodes a protein involved in regulation of the cell cycle through interactions with several cyclin-dependent kinases(Malumbres 2014). BET1 encodes a golgi-associated membrane protein that participates in vesicular transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi complex(Hay et al. 1996). SLC22A17 is a cell surface receptor for Lipocalin 2, an antibacterial protein that acts by sequestering iron during bacterial infection and has recently been reported to be involved in various pathophysiological conditions in various organs and tissues, including the heart and brain(Lim et al. 2021).

Two genes indicated in brain tissue with a low (2a) regulome score include CEP68, and CISD3 (Supplemental Table 5). CEP68 has a mouse cardiovascular phenotype (increased heart weight), and variants at this locus have previously been associated with atrial fibrillation (Christophersen et al. 2017). CISD3 may play a role in regulating electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation(Wiley et al. 2007), and diseases associated with this gene include Wolfram Syndrome, a disorder which is associated with childhood diabetes, optic atrophy and deafness (OMIM number 222,300).

Genes identified using protein expression

We identified significant pQTLs for three genes, GCKR, ENO3 and MXRA7 (Supplemental Table 6). These three genes also had support from other analyses; missense annotation (GCKR), and eQTL analyses (ENO3 and MXRA7). GCKR regulates glucokinase by forming an inactive complex with this enzyme. Postprandial triglyceridemia is an emerging risk factor for cardiovascular disease and GCKR gene polymorphisms affect postprandial lipemic response in a dietary intervention study(Shen et al. 2009). ENO3 has demonstrated increased differential expression in the left ventricle in rats(Giusti et al. 2009). The role of MXRA7 (matrix-remodeling-associated protein 7) in potentially modulating RHR and cardiovascular disease is less known; but it has previously been associated with a cardiorespiratory fitness polygenic risk score(Cai et al. 2023).

Candidate gene prioritisation

From the complementary fine mapping and computational approaches, we prioritised a total of 262 candidate genes for RHR that had at least one line of evidence (Supplemental Table 7). This list includes 21 genes with high-confidence missense variants (Table 1), 40 genes with colocalised eQTLs (Supplemental Table 4), 207 genes with Hi-C interactions (Supplemental Table 5) and 3 genes with colocalised pQTLs (Supplemental Table 6).

Biological pathways

To gain insights into the biological role of the 262 candidate genes for RHR, we performed gene-set enrichment analyses via FUMA (Methods). We found significant enrichment for 41 unique GO biological processes (Supplemental Table 8). The most significant biological processes included cellular component morphogenesis (P = 2.1 × 10− 4), neuron differentiation (P = 4.6 × 10− 4), and neuron development (P = 8.9 × 10− 4).

Additional functional evidence for RHR candidate effector genes

To explore the function of the 262 prioritised candidate genes, additional evidence for each candidate effector gene was assessed using mouse model data, human cardiovascular phenotypes and assessing differential expression of RNA/protein in cardiovascular tissues. We observed 74 of the 262 prioritised candidate genes (28.2%) to have support from mouse model data and 45 (17.2%) from human cardiovascular phenotypes (96 genes had support from mouse or human cardiovascular phenotypes). We also found 45 candidate genes (4.2%) had support from RNA or protein differential expression. In total, 23 candidate genes (9.2%) had additional functional evidence from both phenotypes and differential expression, and 12 of these 23 genes directly showed an abnormal heart rate phenotype in mouse or human experimental models (Table 2, Supplemental Table 7).

Drug target identification and repositioning opportunities

We found 21 of the 262 candidate effector genes were existing targets of small molecules or biotherapeutics and clinical drug candidates (Tier 1, Supplemental Table 9). Of these, 5 were among the 23 candidate genes with additional functional evidence, SCN10A, CACNA1D, ACHE, CHRM2 and MYH6 (all directly liked to RHR through abnormal mouse or human phenotypes). CACNA1D, MYH6 and SCN10A had a cardiovascular disease as their top disease association (sinoatrial node dysfunction, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and AF, respectively). CHRM2 and CACNA1D are established targets of drugs with an intention to either increase (atropine) or decrease (Diltiazem, Verapamil) RHR. In the remaining genes, the cardiovascular system was not implicated as top disease association, suggesting potential drug repurposing. For example, ACHE is a target of drugs for Alzheimer’s disease, including Donepezil and Galantamine, which cause bradycardia as a side effect.

The 262 candidate effector genes were enriched for gene-sets targeted by drugs for the nervous system, anaesthetics and gastrointestinal disorders (Supplemental Table 10). Pathway-directed investigation identified 48 drugs with support that dysregulate the GO biological processes either by up or down-regulation, including Isoprenaline and Atenolol (Supplemental Table 11). Of the top 10 drugs, Buspirone (5-Hydroxytryptamine 1 A receptor antagonist)(Osei-Owusu and Scrogin 2004) and Oxybuprocaine (anaesthetic) (Hung et al. 2010) have experimental evidence for an effect on RHR but are not current drug targets for cardiovascular diseases. The compound 2,6-dimethylpiperidine has previously demonstrated antiarrhythmic activity in a dog model however to the best of our knowledge, has not undergone further investigation (Hoefle et al. 1991).

Discussion

In the present work, we employed a functionally informed statistical framework to advance from initial broadly associated genomic regions to the prioritisation of 262 candidate effector genes for RHR. From these, 23 had additional functional evidence and 21 were existing drug targets.

We used a functionally informed fine-mapping approach to specify plausible causal variants and 262 candidate genes for RHR using biologically interpretable annotations that were identified without prior knowledge of the trait. A recent paper by Van de Vegte et al., used a scoring system for gene prioritisation based on four criteria: proximity, coding, eQTL and evidence from Data-driven Expression Prioritized Integration for Complex Traits (DEPICT). They highlighted a lower number of effector genes, 39 genes with high level of support, PHACTR2, ENO3 and SENP2 being their top effector genes(van de Vegte et al. 2023). A direct comparison with our results is difficult because of methodological differences. First, our pipeline ranks variants based on annotation-informed posterior probability of causality, instead of P-values. Second, we included evidence from Hi-C interactions (79% of candidate effector genes had Hi-C interaction support). Third, our study focused on individuals with European ancestry, whereas they conducted a multi-ancestry approach, hence reporting additional loci from their GWAS, therefore the number of starting signals is different. However, looking at their 39 prioritised genes, we found 32 of the genomic regions where these genes mapped to were genome-wide significant in our European GWAS, demonstrating positional overlap (Supplemental Table 12). At these 32 signals, our fine-mapping pipeline indicated 18 had a high-confidence variant and were, thus, considered for candidate effector gene prioritization. Our methodology provided support for 12 genes indicated by the 18 signals (31% of the genes prioritised by van de Vegte et al.), including ENO3, and 5 of these 12 (42%) were in our list of 23 genes with additional evidence (CCDC141, CMYA5, KCNJ5, MYH6 and FHOD3, Supplemental Table 12). At the remaining 6 signals, our methodology prioritised a different effector gene. The comparison between studies highlights that our annotation-informed fine-mapping approach, which utilises numerous layers of multi-omics data following the identification of signals with high-confidence causal variants, along with validating previously reported effector genes, has prioritised important candidate genes for RHR for the first time.

Previous studies have reported enrichment of associations in pathways involved in cardiac tissue development, muscle cell differentiation and pro-arrhythmic pathways for RHR(den Hoed et al. 2013; van de Vegte et al. 2023; van den Berg et al. 2017). Experimental studies have generally focused on providing functional evidence for RHR genes involved in the cardiovascular system(Liaqat et al. 2019). However, our enrichment results provide, for the first time, support for nervous system pathways, a role that is supported by existing knowledge for autonomic regulation of heart rate. The genes involved in these pathways, therefore, warrant further investigation in functional studies.

Twenty-nine of the 41 (> 50%) of the significant biological pathways identified using the 262 prioritised candidate genes implicate at least one of the 23 candidate genes with additional functional evidence. We highlight two of these 23 not previously prioritised as candidate genes for RHR, CACNA1D and RBM20. CACNA1D, which was identified in this work as an existing target of calcium channel blockers, is present in the membrane of most excitable cells and mediates calcium influx in response to depolarization(Fourbon et al. 2017). Associated diseases include sinoatrial node dysfunction and deafness(Liaqat et al. 2019). RBM20 acts as a regulator of mRNA splicing of a subset of genes encoding key structural proteins involved in cardiac development, such as TTN, CACNA1C, CAMK2D or PDLIM5/ENH(Vieira-Vieira et al. 2022). Mutations in this gene have been associated with familial dilated cardiomyopathy(Hoogenhof et al. 2018).

Druggability analyses highlighted three candidate genes as top gene targets for cardiovascular disease and four for a neurological disease with repurposing potential, ACHE, CALCRL, MYT1 and TDP1. ACHE is a target of drugs for Alzheimer’s disease including Donepezil and Galantamine, which cause bradycardia as a side effect. CALCRL is a target of drugs for migraine disorder. It is a receptor for adrenomedullin, together with RAMP2(Mackie et al. 2018). One of the reported mouse phenotypes is differences in heart rate of heterozygous CALCRL female and male mice(Pawlak et al. 2017). MYT1 is a drug target for autism spectrum disorder and is less characterised, it binds to the promoter regions of proteolipid proteins of the central nervous system and plays a role in the developing nervous system(Lee et al. 2019). Finally, TDP1 is a drug target for spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 with axonal neuropathy(Hirano et al. 2007), which correlates with cardiac autonomic dysfunction, predominantly parasympathetic(Pradhan et al. 2008). Future work should evaluate the causal link between these drug targets and RHR using Mendelian Randomisation analyses, as done recently(Schmidt et al. 2020).

We found limited overlap across the different lines of evidence for each candidate gene (Supplementary Table 7), as previously described(Gazal et al. 2022). The use of cis-eQTL analyses for candidate gene prioritisation has been demonstrated to have a high precision but a lower recall, whereas promoter-capture Hi-C data add specificity, resulting in a complementary approach. Nevertheless, the strong benefit of including Hi-C data is that it provides evidence of tissue-specific physical 3D contact between the candidate cis-regulatory element and a specific protein coding gene’s promoter. Furthermore, we observed that the Hi-C analysis was the line of evidence contributing most of the genes. This can be supported by a recent re-evaluation of the a priori functional likelihood of eQTLs, due to their skew towards promoter loci and large effect sizes(Mostafavi et al. 2023).

There are some limitations to our study, firstly the lack of population diversity in our analyses. The annotation-informed fine mapping analyses were performed in a European ancestry GWAS from UK Biobank despite larger meta-analyses including other ancestries being available(van de Vegte et al. 2023). The reason of this was to avoid the calibration issues of meta-analysis fine-mapping and the heterogeneities and noise in phenotyping found in large meta-analyses(Kanai et al. 2022). An additional weakness is that whilst benefitting from dense genotyping and imputation of common variants, this is not exhaustive in capturing all the potential phenotypically associated genetic variation within each locus. This will miss the possible impact of rare variants, as well as any poorly tagged larger variant (copy number variants, short tandem repeats, inversions, etc.). Finally, we used an established tool, fGWAS(Pickrell 2014), to perform a joint analysis of functional genomic and GWAS data, as done by other studies(Jagadeesh et al. 2022; Liu and Montgomery 2020), followed by a previously reported methodology(Mahajan et al. 2018; Morris et al. 2019; van Duijvenboden et al. 2023) as our fine-mapping approach. Other functionally informed fine-mapping tools, like PolyFun(Weissbrod et al. 2020), could have alternatively been used.

In conclusion, we have prioritised 262 candidate genes using annotation-informed fine mapping and implicated, along with previously observed enriched tissues, nervous system pathways for the first time. Our findings inform further investigations to improve the functional understanding of the biology underlying RHR and may enable novel preventive and therapeutic opportunities.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

JR acknowledges fellowship RYC2021-031413-I and grant PID2021-128972OA-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union ‘‘NextGenerationEU/PRTR’’. PBM, AT and WJY acknowledge the support of the National Institute for Health and Care Research Barts Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR203330); a delivery partnership of Barts Health NHS Trust, Queen Mary University of London, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and St George’s University of London, and Medical Research Council grant MR/N025083/1. WJY recognises the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Integrated Academic Training programme, which supports his Academic Clinical Lectureship post. PDL is supported by BHF, UCL and UCLH Biomedicine National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). CGB is supported by Impetus Hevolution, BrightFocus, and Barts Charity. APM acknowledges support from the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR203308). This research utilised Queen Mary’s Apocrita HPC facility, supported by QMUL Research-IT.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data analysis was mainly performed by JR and SvD and supervised by CGB, AM and PBM. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JR, SvD and PBM and all authors provided feedback and contributed to this draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. JR acknowledges funding from the European Union-NextGenerationEU, fellowship RYC2021-031413-I from MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and from the European Union ‘‘NextGenerationEU/PRTR’’ and from grant PID2021-128972OA-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. PBM, AT and WJY acknowledge the support of the National Institute for Health and Care Research Barts Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR203330); a delivery partnership of Barts Health NHS Trust, Queen Mary University of London, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and St George’s University of London, and Medical Research Council grant MR/N025083/1. WJY recognises the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Integrated Academic Training programme, which supports his Academic Clinical Lectureship post. PDL is supported by BHF, UCL and UCLH Biomedicine National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). CGB is supported by Impetus Hevolution, BrightFocus, and Barts Charity. APM acknowledges support from the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR203308). This research utilised Queen Mary’s Apocrita HPC facility, supported by QMUL Research-IT.

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Data availability

The data generated during the analyses performed in this study can be found in the main and supplementary material.

Declarations

Ethical approval

The UK Biobank study has approval from the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee, and all participants provided informed consent. Data used in this study were part of the UK Biobank application number 8256.

Consent to participate

The UK Biobank study has approval from the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee, and all participants provided informed consent. Data used in this study were part of the UK Biobank application number 8256.

Consent to publication

Our manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data in any form.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Julia Ramírez and Stefan van Duijvenboden contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Julia Ramírez, Email: Julia.Ramirez@unizar.es.

Stefan van Duijvenboden, Email: stefan.vanduijvenboden@ndph.ox.ac.uk.

Patricia B. Munroe, Email: p.b.munroe@qmul.ac.uk

References

- Bruneau BG (2008) The developmental genetics of congenital heart disease. Nature 451:943–948. 10.1038/nature06801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Gonzales T, Wheeler E, Kerrison ND, Day FR, Langenberg C, Perry JRB, Brage S, Wareham NJ (2023) Causal associations between cardiorespiratory fitness and type 2 diabetes. Nat Commun 14:3904. 10.1038/s41467-023-38234-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargnoni A, Ceconi C, Stavroula G, Ferrari R (2006) Heart rate reduction by pharmacological if current inhibition. Adv Cardiol 43:31–44. 10.1159/000095404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophersen IE, Rienstra M, Roselli C, Yin X, Geelhoed B, Barnard J, Lin H, Arking DE, Smith AV, Albert CM, Chaffin M, Tucker NR, Li M, Klarin D, Bihlmeyer NA, Low S-K, Weeke PE, Müller-Nurasyid M, Smith JG, Brody JA, Niemeijer MN, Dörr M, Trompet S, Huffman J, Gustafsson S, Schurmann C, Kleber ME, Lyytikäinen L-P, Seppälä I, Malik R, Horimoto ARVR, Perez M, Sinisalo J, Aeschbacher S, Thériault S, Yao J, Radmanesh F, Weiss S, Teumer A, Choi SH, Weng L-C, Clauss S, Deo R, Rader DJ, Shah SH, Sun A, Hopewell JC, Debette S, Chauhan G, Yang Q, Worrall BB, Paré G, Kamatani Y, Hagemeijer YP, Verweij N, Siland JE, Kubo M, Smith JD, Van Wagoner DR, Bis JC, Perz S, Psaty BM, Ridker PM, Magnani JW, Harris TB, Launer LJ, Shoemaker MB, Padmanabhan S, Haessler J, Bartz TM, Waldenberger M, Lichtner P, Arendt M, Krieger JE, Kähönen M, Risch L, Mansur AJ, Peters A, Smith BH, Lind L, Scott SA, Lu Y, Bottinger EB, Hernesniemi J, Lindgren CM, Wong JA, Huang J, Eskola M, Morris AP, Ford I, Reiner AP, Delgado G, Chen LY, Chen Y-DI, Sandhu RK, Li M, Boerwinkle E, Eisele L, Lannfelt L, Rost N et al (2017) Large-scale analyses of common and rare variants identify 12 new loci associated with atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet 49:946–952. 10.1038/ng.3843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hoed M, Eijgelsheim M, Esko T, Brundel BJJM, Peal DS, Evans DM, Nolte IM, Segrè AV, Holm H, Handsaker RE, Westra H-J, Johnson T, Isaacs A, Yang J, Lundby A, Zhao JH, Kim YJ, Go MJ, Almgren P, Bochud M, Boucher G, Cornelis MC, Gudbjartsson D, Hadley D, van der Harst P, Hayward C, den Heijer M, Igl W, Jackson AU, Kutalik Z, Luan Ja, Kemp JP, Kristiansson K, Ladenvall C, Lorentzon M, Montasser ME, Njajou OT, O’Reilly PF, Padmanabhan S, St. Pourcain B, Rankinen T, Salo P, Tanaka T, Timpson NJ, Vitart V, Waite L, Wheeler W, Zhang W, Draisma HHM, Feitosa MF, Kerr KF, Lind PA, Mihailov E, Onland-Moret NC, Song C, Weedon MN, Xie W, Yengo L, Absher D, Albert CM, Alonso A, Arking DE, de Bakker PIW, Balkau B, Barlassina C, Benaglio P, Bis JC, Bouatia-Naji N, Brage S, Chanock SJ, Chines PS, Chung M, Darbar D, Dina C, Dörr M, Elliott P, Felix SB, Fischer K, Fuchsberger C, de Geus EJC, Goyette P, Gudnason V, Harris TB, Hartikainen A-L, Havulinna AS, Heckbert SR, Hicks AA, Hofman A, Holewijn S, Hoogstra-Berends F, Hottenga J-J, Jensen MK, Johansson Å, Junttila J, Kääb S, Kanon B, Ketkar S, Khaw K-T, Knowles JW, Kooner AS et al (2013) Identification of heart rate–associated loci and their effects on cardiac conduction and rhythm disorders. Nature Genetics 45: 621–631. 10.1038/ng.2610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Derrick CJ, Pollitt EJG, Sanchez Sevilla Uruchurtu A, Hussein F, Grierson AJ, Noël ES (2021) Lamb1a regulates atrial growth by limiting second heart field addition during zebrafish heart development. Development 148. 10.1242/dev.199691 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Eijgelsheim M, Newton-Cheh C, Sotoodehnia N, de Bakker PIW, Müller M, Morrison AC, Smith AV, Isaacs A, Sanna S, Dörr M, Navarro P, Fuchsberger C, Nolte IM, de Geus EJC, Estrada K, Hwang S-J, Bis JC, Rückert I-M, Alonso A, Launer LJ, Hottenga JJ, Rivadeneira F, Noseworthy PA, Rice KM, Perz S, Arking DE, Spector TD, Kors JA, Aulchenko YS, Tarasov KV, Homuth G, Wild SH, Marroni F, Gieger C, Licht CM, Prineas RJ, Hofman A, Rotter JI, Hicks AA, Ernst F, Najjar SS, Wright AF, Peters A, Fox ER, Oostra BA, Kroemer HK, Couper D, Völzke H, Campbell H, Meitinger T, Uda M, Witteman JCM, Psaty BM, Wichmann H-E, Harris TB, Kääb S, Siscovick DS, Jamshidi Y, Uitterlinden AG, Folsom AR, Larson MG, Wilson JF, Penninx BW, Snieder H, Pramstaller PP, van Duijn CM, Lakatta EG, Felix SB, Gudnason V, Pfeufer A, Heckbert SR, Stricker BHC, Boerwinkle E, O’Donnell CJ (2010) Genome-wide association analysis identifies multiple loci related to resting heart rate. Hum Mol Genet 19:3885–3894. 10.1093/hmg/ddq303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppinga RN, Hagemeijer Y, Burgess S, Hinds DA, Stefansson K, Gudbjartsson DF, van Veldhuisen DJ, Munroe PB, Verweij N, van der Harst P (2016) Identification of genomic loci associated with resting heart rate and shared genetic predictors with all-cause mortality. Nat Genet 48:1557–1563. 10.1038/ng.3708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferkingstad E, Sulem P, Atlason BA, Sveinbjornsson G, Magnusson MI, Styrmisdottir EL, Gunnarsdottir K, Helgason A, Oddsson A, Halldorsson BV, Jensson BO, Zink F, Halldorsson GH, Masson G, Arnadottir GA, Katrinardottir H, Juliusson K, Magnusson MK, Magnusson OT, Fridriksdottir R, Saevarsdottir S, Gudjonsson SA, Stacey SN, Rognvaldsson S, Eiriksdottir T, Olafsdottir TA, Steinthorsdottir V, Tragante V, Ulfarsson MO, Stefansson H, Jonsdottir I, Holm H, Rafnar T, Melsted P, Saemundsdottir J, Norddahl GL, Lund SH, Gudbjartsson DF, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K (2021) Large-scale integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat Genet 53:1712–1721. 10.1038/s41588-021-00978-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan C, Gaulton A, Kruger FA, Lumbers RT, Shah T, Engmann J, Galver L, Kelley R, Karlsson A, Santos R, Overington JP, Hingorani AD, Casas JP (2017) The druggable genome and support for target identification and validation in drug development. Sci Transl Med 9:eaag1166. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourbon Y, Guéguinou M, Félix R, Constantin B, Uguen A, Fromont G, Lajoie L, Magaud C, Lecomte T, Chamorey E, Chatelier A, Mignen O, Potier-Cartereau M, Chantôme A, Bois P, Vandier C (2017) Ca2 + protein alpha 1D of CaV1.3 regulates intracellular calcium concentration and migration of colon cancer cells through a non-canonical activity. Sci Rep 7:14199. 10.1038/s41598-017-14230-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazal S, Weissbrod O, Hormozdiari F, Dey KK, Nasser J, Jagadeesh KA, Weiner DJ, Shi H, Fulco CP, O’Connor LJ, Pasaniuc B, Engreitz JM, Price AL (2022) Combining SNP-to-gene linking strategies to identify disease genes and assess disease omnigenicity. Nat Genet 54:827–836. 10.1038/s41588-022-01087-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerull B, Brodehl A (2020) Genetic animal models for Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Front Physiol 11. 10.3389/fphys.2020.00624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Giusti B, Marini M, Rossi L, Lapini I, Magi A, Capalbo A, Lapalombella R, di Tullio S, Samaja M, Esposito F, Margonato V, Boddi M, Abbate R, Veicsteinas A (2009) Gene expression profile of rat left ventricles reveals persisting changes following chronic mild exercise protocol: implications for cardioprotection. BMC Genomics 10:342. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Chung W, Zhu Z, Shan Z, Li J, Liu S, Liang L (2019) Genome-wide Assessment for resting Heart Rate and Shared Genetics with Cardiometabolic traits and Type 2 diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol 74:2162–2174. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag TA, Haag NP, Lekven AC, Hartenstein V (1999) The role of cell adhesion molecules inDrosophilaHeart morphogenesis:faint sausage, Shotgun/DE-Cadherin, andLaminin AAre required for Discrete stages in Heart Development. Dev Biol 208:56–69. 10.1006/dbio.1998.9188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM, Tapanari E, Diekhans M, Kokocinski F, Aken BL, Barrell D, Zadissa A, Searle S, Barnes I, Bignell A, Boychenko V, Hunt T, Kay M, Mukherjee G, Rajan J, Despacio-Reyes G, Saunders G, Steward C, Harte R, Lin M, Howald C, Tanzer A, Derrien T, Chrast J, Walters N, Balasubramanian S, Pei B, Tress M, Rodriguez JM, Ezkurdia I, van Baren J, Brent M, Haussler D, Kellis M, Valencia A, Reymond A, Gerstein M, Guigó R, Hubbard TJ (2012) GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for the ENCODE Project. Genome Res 22:1760–1774. 10.1101/gr.135350.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JC, Hirling H, Scheller RH (1996) Mammalian vesicle trafficking proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum and golgi apparatus (∗). J Biol Chem 271:5671–5679. 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano R, Interthal H, Huang C, Nakamura T, Deguchi K, Choi K, Bhattacharjee MB, Arimura K, Umehara F, Izumo S, Northrop JL, Salih MA, Inoue K, Armstrong DL, Champoux JJ, Takashima H, Boerkoel CF (2007) Spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy: consequence of a Tdp1 recessive neomorphic mutation? EMBO J 26:4732–4743. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefle ML, Blouin LT, Fleming RW, Hastings S, Hinkley JM, Mertz TE, Steffe TJ, Stratton CS, Werbel LM (1991) Synthesis and antiarrhythmic activity of.alpha.-[(diarylmethoxy)methyl]-1-piperidineethanols. J Med Chem 34:7–12. 10.1021/jm00105a002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenhof MMGvd, Beqqali A, Amin AS, Made Ivd, Aufiero S, Khan MAF, Schumacher CA, Jansweijer JA, Spaendonck-Zwarts KYv, Remme CA, Backs J, Verkerk AO, Baartscheer A, Pinto YM, Creemers EE (2018) RBM20 mutations induce an arrhythmogenic dilated cardiomyopathy related to disturbed Calcium Handling. Circulation 138:1330–1342. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C-H, Liu K-S, Shao D-Z, Cheng K-I, Chen Y-C, Chen Y-W (2010) The systemic toxicity of Equipotent Proxymetacaine, Oxybuprocaine, and Bupivacaine during continuous intravenous infusion in rats. Anesth Analgesia 110:238–242. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181bf6acf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadeesh KA, Dey KK, Montoro DT, Mohan R, Gazal S, Engreitz JM, Xavier RJ, Price AL, Regev A (2022) Identifying disease-critical cell types and cellular processes by integrating single-cell RNA-sequencing and human genetics. Nat Genet 54:1479–1492. 10.1038/s41588-022-01187-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung I, Schmitt A, Diao Y, Lee AJ, Liu T, Yang D, Tan C, Eom J, Chan M, Chee S, Chiang Z, Kim C, Masliah E, Barr CL, Li B, Kuan S, Kim D, Ren B (2019) A compendium of promoter-centered long-range chromatin interactions in the human genome. Nat Genet 51:1442–1449. 10.1038/s41588-019-0494-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan -OM, Takeya R, Abe T, Kitajima N, Nishida M, Tominaga R, Kurose H, Sumimoto H (2012) Mammalian formin Fhod3 plays an essential role in cardiogenesis by organizing myofibrillogenesis. Biology Open 1:889–896. 10.1242/bio.20121370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai M, Elzur R, Zhou W, Zhou W, Kanai M, Wu K-HH, Rasheed H, Tsuo K, Hirbo JB, Wang Y, Bhattacharya A, Zhao H, Namba S, Surakka I, Wolford BN, Lo Faro V, Lopera-Maya EA, Läll K, Favé M-J, Partanen JJ, Chapman SB, Karjalainen J, Kurki M, Maasha M, Brumpton BM, Chavan S, Chen T-T, Daya M, Ding Y, Feng Y-CA, Guare LA, Gignoux CR, Graham SE, Hornsby WE, Ingold N, Ismail SI, Johnson R, Laisk T, Lin K, Lv J, Millwood IY, Moreno-Grau S, Nam K, Palta P, Pandit A, Preuss MH, Saad C, Setia-Verma S, Thorsteinsdottir U, Uzunovic J, Verma A, Zawistowski M, Zhong X, Afifi N, Al-Dabhani KM, Al Thani A, Bradford Y, Campbell A, Crooks K, de Bock GH, Damrauer SM, Douville NJ, Finer S, Fritsche LG, Fthenou E, Gonzalez-Arroyo G, Griffiths CJ, Guo Y, Hunt KA, Ioannidis A, Jansonius NM, Konuma T, Michael Lee MT, Lopez-Pineda A, Matsuda Y, Marioni RE, Moatamed B, Nava-Aguilar MA, Numakura K, Patil S, Rafaels N, Richmond A, Rojas-Muñoz A, Shortt JA, Straub P, Tao R, Vanderwerff B, Vernekar M, Veturi Y, Barnes KC, Boezen M, Chen Z, Chen C-Y, Cho J, Smith GD, Finucane HK, Franke L, Gamazon ER, Ganna A, Gaunt TR et al (2022) Meta-analysis fine-mapping is often miscalibrated at single-variant resolution. Cell Genomics 2:100210. 10.1016/j.xgen.2022.100210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundaje A, Meuleman W, Ernst J, Bilenky M, Yen A, Heravi-Moussavi A, Kheradpour P, Zhang Z, Wang J, Ziller MJ, Amin V, Whitaker JW, Schultz MD, Ward LD, Sarkar A, Quon G, Sandstrom RS, Eaton ML, Wu Y-C, Pfenning A, Wang X, ClaussnitzerYaping Liu M, Coarfa C, Alan Harris R, Shoresh N, Epstein CB, Gjoneska E, Leung D, Xie W, David Hawkins R, Lister R, Hong C, Gascard P, Mungall AJ, Moore R, Chuah E, Tam A, Canfield TK, Scott Hansen R, Kaul R, Sabo PJ, Bansal MS, Carles A, Dixon JR, Farh K-H, Feizi S, Karlic R, Kim A-R, Kulkarni A, Li D, Lowdon R, Elliott G, Mercer TR, Neph SJ, Onuchic V, Polak P, Rajagopal N, Ray P, Sallari RC, Siebenthall KT, Sinnott-Armstrong NA, Stevens M, Thurman RE, Wu J, Zhang B, Zhou X, Abdennur N, Adli M, Akerman M, Barrera L, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Ballinger T, Barnes MJ, Bates D, Bell RJA, Bennett DA, Bianco K, Bock C, Boyle P, Brinchmann J, Caballero-Campo P, Camahort R, Carrasco-Alfonso MJ, Charnecki T, Chen H, Chen Z, Cheng JB, Cho S, Chu A, Chung W-Y, Cowan C, Athena Deng Q, Deshpande V, Diegel M, Ding B, Durham T, Echipare L, Edsall L, Flowers D, Genbacev-Krtolica O et al (2015) Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature 518:317–330. 10.1038/nature14248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Taylor CA, Barnes KM, Shen A, Stewart EV, Chen A, Xiang YK, Bao Z, Shen K (2019) A Myt1 family transcription factor defines neuronal fate by repressing non-neuronal genes. eLife 8:e46703. 10.7554/eLife.46703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaqat K, Schrauwen I, Raza SI, Lee K, Hussain S, Chakchouk I, Nasir A, Acharya A, Abbe I, Umair M, Ansar M, Ullah I, Shah K, Bamshad MJ, Nickerson DA, Ahmad W, Leal SM, University of Washington Center for Mendelian G (2019) Identification of CACNA1D variants associated with sinoatrial node dysfunction and deafness in additional Pakistani families reveals a clinical significance. J Hum Genet 64:153–160. 10.1038/s10038-018-0542-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D, Jeong J-h, Song J (2021) Lipocalin 2 regulates iron homeostasis, neuroinflammation, and insulin resistance in the brains of patients with dementia: evidence from the current literature. CNS Neurosci Ther 27:883–894. 10.1111/cns.13653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Montgomery SB (2020) Identifying causal variants and genes using functional genomics in specialized cell types and contexts. Hum Genet 139:95–102. 10.1007/s00439-019-02044-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie DI, Al Mutairi F, Davis RB, Kechele DO, Nielsen NR, Snyder JC, Caron MG, Kliman HJ, Berg JS, Simms J, Poyner DR, Caron KM (2018) hCALCRL mutation causes autosomal recessive nonimmune hydrops fetalis with lymphatic dysplasia. J Exp Med 215:2339–2353. 10.1084/jem.20180528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan A, Taliun D, Thurner M, Robertson NR, Torres JM, Rayner NW, Payne AJ, Steinthorsdottir V, Scott RA, Grarup N, Cook JP, Schmidt EM, Wuttke M, Sarnowski C, Mägi R, Nano J, Gieger C, Trompet S, Lecoeur C, Preuss MH, Prins BP, Guo X, Bielak LF, Below JE, Bowden DW, Chambers JC, Kim YJ, Ng MCY, Petty LE, Sim X, Zhang W, Bennett AJ, Bork-Jensen J, Brummett CM, Canouil M, Ec kardt K-U, Fischer K, Kardia SLR, Kronenberg F, Läll K, Liu C-T, Locke AE, Luan Ja, Ntalla I, Nylander V, Schönherr S, Schurmann C, Yengo L, Bottinger EP, Brandslund I, Christensen C, Dedoussis G, Florez JC, Ford I, Franco OH, Frayling TM, Giedraitis V, Hackinger S, Hattersley AT, Herder C, Ikram MA, Ingelsson M, Jørgensen ME, Jørgensen T, Kriebel J, Kuusisto J, Ligthart S, Lindgren CM, Linneberg A, Lyssenko V, Mamakou V, Meitinger T, Mohlke KL, Morris AD, Nadkarni G, Pankow JS, Peters A, Sattar N, Stančáková A, Strauch K, Taylor KD, Thorand B, Thorleifsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Tuomilehto J, Witte DR, Dupuis J, Peyser PA, Zeggini E, Loos RJF, Froguel P, Ingelsson E, Lind L, Groop L, Laakso M, Collins FS, Jukema JW, Palmer CNA, Grallert H, Metspalu A et al (2018) Fine-mapping type 2 diabetes loci to single-variant resolution using high-density imputation and islet-specific epigenome maps. Nat Genet 50:1505–1513. 10.1038/s41588-018-0241-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M (2014) Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol 15:122. 10.1186/gb4184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren W, Gil L, Hunt SE, Riat HS, Ritchie GRS, Thormann A, Flicek P, Cunningham F (2016) The Ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol 17:122. 10.1186/s13059-016-0974-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensah-Kane J, Schmidt AF, Hingorani AD, Finan C, Chen Y, van Duijvenboden S, Orini M, Lambiase PD, Tinker A, Marouli E, Munroe PB, Ramírez J (2021) No clinically relevant Effect of Heart rate increase and Heart Rate Recovery during Exercise on Cardiovascular Disease: a mendelian randomization analysis. Front Genet 12. 10.3389/fgene.2021.569323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Morris AP, Le TH, Wu H, Akbarov A, van der Most PJ, Hemani G, Smith GD, Mahajan A, Gaulton KJ, Nadkarni GN, Valladares-Salgado A, Wacher-Rodarte N, Mychaleckyj JC, Dueker ND, Guo X, Hai Y, Haessler J, Kamatani Y, Stilp AM, Zhu G, Cook JP, Ärnlöv J, Blanton SH, de Borst MH, Bottinger EP, Buchanan TA, Cechova S, Charchar FJ, Chu P-L, Damman J, Eales J, Gharavi AG, Giedraitis V, Heath AC, Ipp E, Kiryluk K, Kramer HJ, Kubo M, Larsson A, Lindgren CM, Lu Y, Madden PAF, Montgomery GW, Papanicolaou GJ, Raffel LJ, Sacco RL, Sanchez E, Stark H, Sundstrom J, Taylor KD, Xiang AH, Zivkovic A, Lind L, Ingelsson E, Martin NG, Whitfield JB, Cai J, Laurie CC, Okada Y, Matsuda K, Kooperberg C, Chen Y-DI, Rundek T, Rich SS, Loos RJF, Parra EJ, Cruz M, Rotter JI, Snieder H, Tomaszewski M, Humphreys BD, Franceschini N (2019) Trans-ethnic kidney function association study reveals putative causal genes and effects on kidney-specific disease aetiologies. Nat Commun 10:29. 10.1038/s41467-018-07867-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafavi H, Spence JP, Naqvi S, Pritchard JK (2023) Systematic differences in discovery of genetic effects on gene expression and complex traits. Nat Genet 55:1866–1875. 10.1038/s41588-023-01529-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano F, Carrella D, Mandriani B, Pisonero-Vaquero S, Sirci F, Medina DL, Brunetti-Pierri N, di Bernardo D (2017) gene2drug: a computational tool for pathway-based rational drug repositioning. Bioinformatics 34:1498–1505. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa JP, Sabater-Molina M, García-Pinilla JM, Mogensen J, Restrepo-Córdoba A, Palomino-Doza J, Villacorta E, Martinez-Moreno M, Ramos-Maqueda J, Zorio E, Peña-Peña ML, García-Granja PE, Rodríguez-Palomares JF, Cárdenas-Reyes IJ, de la Torre-Carpente MM, Bautista-Pavés A, Akhtar MM, Cicerchia MN, Bilbao-Quesada R, Mogollón-Jimenez MV, Salazar-Mendiguchía J, Mesa Latorre JM, Arnaez B, Olavarri-Miguel I, Fuentes-Cañamero ME, Lamounier A, Pérez Ruiz JM, Climent-Payá V, Pérez-Sanchez I, Trujillo-Quintero JP, Lopes LR, Repáraz-Andrade A, Marín-Iglesias R, Rodriguez-Vilela A, Sandín-Fuentes M, Garrote JA, Cortel-Fuster A, Lopez-Garrido M, Fontalba-Romero A, Ripoll-Vera T, Llano-Rivas I, Fernandez-Fernandez X, Isidoro-García M, Garcia-Giustiniani D, Barriales-Villa R, Ortiz-Genga M, García-Pavía P, Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Monserrat L (2018) Formin Homology 2 Domain containing 3 (FHOD3) is a genetic basis for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 72:2457–2467. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Owusu P, Scrogin KE (2004) Buspirone raises blood pressure through activation of sympathetic nervous system and by direct activation of α1-Adrenergic receptors after severe hemorrhage. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 309:1132–1140. 10.1124/jpet.103.064626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak JB, Wetzel-Strong SE, Dunn MK, Caron KM (2017) Cardiovascular effects of exogenous adrenomedullin and CGRP in Ramp and Calcrl deficient mice. Peptides 88:1–7. 10.1016/j.peptides.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell Joseph K (2014) Am J Hum Genet 94:559–573. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.004. Joint Analysis of Functional Genomic Data and Genome-wide Association Studies of 18 Human Traits [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pradhan C, Yashavantha BS, Pal PK, Sathyaprabha TN (2008) Spinocerebellar ataxias type 1, 2 and 3: a study of heart rate variability. Acta Neurol Scand 117:337–342. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00945.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez J, Duijvenboden Sv, Ntalla I, Mifsud B, Warren HR, Tzanis E, Orini M, Tinker A, Lambiase PD, Munroe PB (2018) Thirty loci identified for heart rate response to exercise and recovery implicate autonomic nervous system. Nature Communications 9: 1947. 10.1038/s41467-018-04148-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Saengkaew T, Ruiz-Babot G, David A, Mancini A, Mariniello K, Cabrera CP, Barnes MR, Dunkel L, Guasti L, Howard SR (2021) Whole exome sequencing identifies deleterious rare variants in CCDC141 in familial self-limited delayed puberty. npj Genomic Med 6:107. 10.1038/s41525-021-00274-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AF, Finan C, Gordillo-Marañón M, Asselbergs FW, Freitag DF, Patel RS, Tyl B, Chopade S, Faraway R, Zwierzyna M, Hingorani AD (2020) Genetic drug target validation using mendelian randomisation. Nat Commun 11:3255. 10.1038/s41467-020-16969-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt Anthony D, Hu M, Jung I, Xu Z, Qiu Y, Tan Catherine L, Li Y, Lin S, Lin Y, Barr Cathy L, Ren B (2016) A compendium of chromatin contact maps reveals spatially active regions in the Human Genome. Cell Rep 17:2042–2059. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Pollin TI, Damcott CM, McLenithan JC, Mitchell BD, Shuldiner AR (2009) Glucokinase regulatory protein gene polymorphism affects postprandial lipemic response in a dietary intervention study. Hum Genet 126:567–574. 10.1007/s00439-009-0700-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara M, Kanekiyo T, Tachibana M, Kurti A, Shinohara M, Fu Y, Zhao J, Han X, Sullivan PM, Rebeck GW, Fryer JD, Heckman MG, Bu G (2020) APOE2 is associated with longevity independent of Alzheimer’s disease. eLife 9:e62199. 10.7554/eLife.62199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielmann N, Miller G, Oprea TI, Hsu C-W, Fobo G, Frishman G, Montrone C, Haseli Mashhadi H, Mason J, Munoz Fuentes V, Leuchtenberger S, Ruepp A, Wagner M, Westphal DS, Wolf C, Görlach A, Sanz-Moreno A, Cho Y-L, Teperino R, Brandmaier S, Sharma S, Galter IR, Östereicher MA, Zapf L, Mayer-Kuckuk P, Rozman J, Teboul L, Bunton-Stasyshyn RKA, Cater H, Stewart M, Christou S, Westerberg H, Willett AM, Wotton JM, Roper WB, Christiansen AE, Ward CS, Heaney JD, Reynolds CL, Prochazka J, Bower L, Clary D, Selloum M, Bou About G, Wendling O, Jacobs H, Leblanc S, Meziane H, Sorg T, Audain E, Gilly A, Rayner NW, Aguilar-Pimentel JA, Becker L, Garrett L, Hölter SM, Amarie OV, Calzada-Wack J, Klein-Rodewald T, da Silva-Buttkus P, Lengger C, Stoeger C, Gerlini R, Rathkolb B, Mayr D, Seavitt J, Gaspero A, Green JR, Garza A, Bohat R, Wong L, McElwee ML, Kalaga S, Rasmussen TL, Lorenzo I, Lanza DG, Samaco RC, Veeraragaven S, Gallegos JJ, Kašpárek P, Petrezsélyová S, King R, Johnson S, Cleak J, Szkoe-Kovacs Z, Codner G, Mackenzie M, Caulder A, Kenyon J, Gardiner W, Phelps H, Hancock R, Norris C, Moore MA, Seluke AM, Urban R, Kane C, Goodwin LO, Peterson KA, McKay M et al (2022) Extensive identification of genes involved in congenital and structural heart disorders and cardiomyopathy. Nat Cardiovasc Res 1:157–173. 10.1038/s44161-022-00018-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statements & Declarations

- Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, Šmuc T (2011) REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of Gene Ontology terms. PLoS ONE 6:e21800. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorolfsdottir RB, Sveinbjornsson G, Sulem P, Helgadottir A, Gretarsdottir S, Benonisdottir S, Magnusdottir A, Davidsson OB, Rajamani S, Roden DM, Darbar D, Pedersen TR, Sabatine MS, Jonsdottir I, Arnar DO, Thorsteinsdottir U, Gudbjartsson DF, Holm H, Stefansson K (2017) A missense variant in PLEC increases risk of Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 70:2157–2168. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorolfsdottir RB, Sveinbjornsson G, Aegisdottir HM, Benonisdottir S, Stefansdottir L, Ivarsdottir EV, Halldorsson GH, Sigurdsson JK, Torp-Pedersen C, Weeke PE, Brunak S, Westergaard D, Pedersen OB, Sorensen E, Nielsen KR, Burgdorf KS, Banasik K, Brumpton B, Zhou W, Oddsson A, Tragante V, Hjorleifsson KE, Davidsson OB, Rajamani S, Jonsson S, Torfason B, Valgardsson AS, Thorgeirsson G, Frigge ML, Thorleifsson G, Norddahl GL, Helgadottir A, Gretarsdottir S, Sulem P, Jonsdottir I, Willer CJ, Hveem K, Bundgaard H, Ullum H, Arnar DO, Thorsteinsdottir U, Gudbjartsson DF, Holm H, Stefansson K, Consortium DG (2021) Genetic insight into sick sinus syndrome. Eur Heart J 42:1959–1971. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa110836282123 [Google Scholar]

- van de Vegte YJ, Eppinga RN, van der Ende MY, Hagemeijer YP, Mahendran Y, Salfati E, Smith AV, Tan VY, Arking DE, Ntalla I, Appel EV, Schurmann C, Brody JA, Rueedi R, Polasek O, Sveinbjornsson G, Lecoeur C, Ladenvall C, Zhao JH, Isaacs A, Wang L, Luan Ja, Hwang S-J, Mononen N, Auro K, Jackson AU, Bielak LF, Zeng L, Shah N, Nethander M, Campbell A, Rankinen T, Pechlivanis S, Qi L, Zhao W, Rizzi F, Tanaka T, Robino A, Cocca M, Lange L, Müller-Nurasyid M, Roselli C, Zhang W, Kleber ME, Guo X, Lin HJ, Pavani F, Galesloot TE, Noordam R, Milaneschi Y, Schraut KE, den Hoed M, Degenhardt F, Trompet S, van den Berg ME, Pistis G, Tham Y-C, Weiss S, Sim XS, Li HL, van der Most PJ, Nolte IM, Lyytikäinen L-P, Said MA, Witte DR, Iribarren C, Launer L, Ring SM, de Vries PS, Sever P, Linneberg A, Bottinger EP, Padmanabhan S, Psaty BM, Sotoodehnia N, Kolcic I, Roshandel D, Paterson AD, Arnar DO, Gudbjartsson DF, Holm H, Balkau B, Silva CT, Newton-Cheh CH, Nikus K, Salo P, Mohlke KL, Peyser PA, Schunkert H, Lorentzon M, Lahti J, Rao DC, Cornelis MC, Faul JD, Smith JA, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Bandinelli S, Concas MP, Sinagra G, Meitinger T et al (2023) Genetic insights into resting heart rate and its role in cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun 14:4646. 10.1038/s41467-023-39521-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg ME, Warren HR, Cabrera CP, Verweij N, Mifsud B, Haessler J, Bihlmeyer NA, Fu Y-P, Weiss S, Lin HJ, Grarup N, Li-Gao R, Pistis G, Shah N, Brody JA, Müller-Nurasyid M, Lin H, Mei H, Smith AV, Lyytikäinen L-P, Hall LM, van Setten J, Trompet S, Prins BP, Isaacs A, Radmanesh F, Marten J, Entwistle A, Kors JA, Silva CT, Alonso A, Bis JC, de Boer R, de Haan HG, de Mutsert R, Dedoussis G, Dominiczak AF, Doney ASF, Ellinor PT, Eppinga RN, Felix SB, Guo X, Hagemeijer Y, Hansen T, Harris TB, Heckbert SR, Huang PL, Hwang S-J, Kähönen M, Kanters JK, Kolcic I, Launer LJ, Li M, Yao J, Linneberg A, Liu S, Macfarlane PW, Mangino M, Morris AD, Mulas A, Murray AD, Nelson CP, Orrú M, Padmanabhan S, Peters A, Porteous DJ, Poulter N, Psaty BM, Qi L, Raitakari OT, Rivadeneira F, Roselli C, Rudan I, Sattar N, Sever P, Sinner MF, Soliman EZ, Spector TD, Stanton AV, Stirrups KE, Taylor KD, Tobin MD, Uitterlinden A, Vaartjes I, Hoes AW, van der Meer P, Völker U, Waldenberger M, Xie Z, Zoledziewska M, Tinker A, Polasek O, Rosand J, Jamshidi Y, van Duijn CM, Zeggini E, Jukema JW, Asselbergs FW, Samani NJ, Lehtimäki T et al (2017) Discovery of novel heart rate-associated loci using the Exome Chip. Hum Mol Genet 26:2346–2363. 10.1093/hmg/ddx113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duijvenboden S, Ramírez J, Young WJ, Olczak KJ, Ahmed F, Alhammadi MJAY, Bell CG, Morris AP, Munroe PB (2023) Integration of genetic fine-mapping and multi-omics data reveals candidate effector genes for hypertension. bioRxiv: 2023.01.26.525702. 10.1101/2023.01.26.525702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Verweij N, van de Vegte YJ, van der Harst P (2018) Genetic study links components of the autonomous nervous system to heart-rate profile during exercise. Nat Commun 9:898. 10.1038/s41467-018-03395-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira-Vieira CH, Dauksaite V, Sporbert A, Gotthardt M, Selbach M (2022) Proteome-wide quantitative RNA-interactome capture identifies phosphorylation sites with regulatory potential in RBM20. Mol Cell 82:2069–2083e8. 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Taskesen E, van Bochoven A, Posthuma D (2017) Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat Commun 8:1826. 10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissbrod O, Hormozdiari F, Benner C, Cui R, Ulirsch J, Gazal S, Schoech AP, van de Geijn B, Reshef Y, Márquez-Luna C, O’Connor L, Pirinen M, Finucane HK, Price AL (2020) Functionally informed fine-mapping and polygenic localization of complex trait heritability. Nat Genet 52:1355–1363. 10.1038/s41588-020-00735-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley SE, Murphy AN, Ross SA, van der Geer P, Dixon JE (2007) MitoNEET is an iron-containing outer mitochondrial membrane protein that regulates oxidative capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104:5318–5323. 10.1073/pnas.0701078104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Ferreira T, Morris AP, Medland SE, Madden PAF, Heath AC, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Weedon MN, Loos RJ, Frayling TM, McCarthy MI, Hirschhorn JN, Goddard ME, Visscher PM (2012) Genetic Investigation of ATC, Replication DIG, Meta-analysis C Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nature Genetics 44: 369–375. 10.1038/ng.2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yousaf R, Ahmed ZM, Giese APJ, Morell RJ, Lagziel A, Dabdoub A, Wilcox ER, Riazuddin S, Friedman TB, Riazuddin S (2018) Modifier variant of METTL13 suppresses human GAB1–associated profound deafness. J Clin Investig 128:1509–1522. 10.1172/JCI97350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Shen X, Qi X (2016) Resting heart rate and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population: a meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J 188:E53–E63. 10.1503/cmaj.150535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Yin M, Deng H, Jin FQ, Xu S, Lu Y, Mastrangelo MA, Luo H, Jin ZG (2016) Cardiac Gab1 deletion leads to dilated cardiomyopathy associated with mitochondrial damage and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 23:695–706. 10.1038/cdd.2015.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Pickrell Joseph K (2014) Am J Hum Genet 94:559–573. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.004. Joint Analysis of Functional Genomic Data and Genome-wide Association Studies of 18 Human Traits [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during the analyses performed in this study can be found in the main and supplementary material.