Abstract

Background

Stroke-associated pneumonia (SAP) and gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) are common medical complications after stroke. The previous study suggested a strong association between SAP and GIB after stroke. However, little is known about the time sequence of SAP and GIB. In the present study, we aimed to verify the association and clarify the temporal sequence of SAP and GIB after ischemic stroke.

Methods

Patients with ischemic stroke from in-hospital Medical Complication after Acute Stroke study were analyzed. Data on occurrences of SAP and GIB during hospitalization and the intervals from stroke onset to diagnosis of SAP and GIB were collected. Multiple logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between SAP and GIB. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the time intervals from stroke onset to diagnosis of SAP and GIB.

Results

A total of 1129 patients with ischemic stroke were included. The median length of hospitalization was 14 days. Overall, 86 patients (7.6%; 95% CI, 6.1-9.2%) developed SAP and 47 patients (4.3%; 95% CI, 3.0-5.3%) developed GIB during hospitalization. After adjusting potential confounders, SAP was significantly associated with the development of GIB after ischemic stroke (OR = 5.13; 95% CI, 2.02-13.00; P < 0.001). The median time from stroke onset to diagnosis of SAP was shorter than that of GIB after ischemic stroke (4 days vs. 5 days; P = 0.039).

Conclusions

SAP was associated with GIB after ischemic stroke, and the onset time of SAP was earlier than that of GIB. It is imperative to take precautions to prevent GIB in stroke patients with SAP.

Keywords: Pneumonia, Gastrointestinal bleeding, Stroke, Temporal sequence

Introduction

Medical complications are frequent among patients after ischemic stroke or hemorrhagic stroke. They can prolong length of hospitalization and increase the costs of care [1–3]. A lot of studies have revealed that the medical complications after stroke were associated with a poor prognosis [4–8]. The complications after stroke can hinder neurological recovery and significantly increase the odds of death [4, 5, 8]. Of the post-stroke complications, pneumonia is one of the most common medical complications with a prevalence of 10% in patients after stroke [9]. Stroke-associated pneumonia (SAP) can increase a higher risk of mortality at discharge, 90 days, and 1 year [10]. Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB), as another common post-stroke complication, is a systemic complication. The frequency of GIB is varied considerably from 1.2 to 8.0% [11–14]. GIB may affect the therapy for acute ischemic stroke (AIS) such as antiplatelet or anticoagulant treatments [13]. Additionally, GIB can increase the risk of severe dependence and long-term mortality [11].

Despite the well-documented association between post-stroke complications and outcome, little is known about the interrelationship between the post-stroke complications. In our previous study, we found that SAP was significantly correlated with non-pneumonia medical complications after AIS [15]. Especially, compared with patients without SAP, the odds ratio of development of GIB in patients with SAP was 8.35 (95% CI 6.27–11.1) after adjusted for potential covariates [15]. However, the temporal sequence of these medical complications after AIS is unclear. Better understanding the characteristics of the complication after stroke can timely identified patients with a higher risk and take measures to prevent the subsequent complications. In the present study, we aimed to (1) evaluate the incidence of SAP and GIB, (2) verify the association between SAP and GIB, and (3) clarify the temporal sequence of SAP and GIB.

Method

Study patients

All patients with AIS registered in in-hospital Medical Complication after Acute Stroke (iMCAS) were included in this study. iMCAS is a prospective cohort study which is designed to (1) compare the risk of medical complications by stroke subtypes, (2) investigate the potential interrelationship between common in-hospital medical complications after stroke and (3) explore bio-markers or neuroimaging-markers for post-stroke medical complications. Patients admitted into the department of neurology at Beijing Tiantan hospital from May 2014 to May 2016 were consecutively registered in the iMCAS. Patients were eligible in this study if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) age 18 or older; (2) hospitalized with a diagnosis of AIS according to the World Health Organization criteria; (3) confirmed by head computerized tomography and /or brain magnetic resonance imaging; (4) time from stroke onset to hospital admission within 7 days.

Data collection and definitions

Data were collected by trained research coordinators using standardized electronic Case Report Form. The following data were documented through medical records or face-to-face interview: demographics (age, gender), stroke risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease, history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, and current smoking), history of using antiplatelet (aspirin, clopidogrel) and anticoagulation (warfarin), comorbidities (valvular heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral artery disease, hepatic cirrhosis, peptic ulcer, renal failure, arthritis and cancer), prestroke dependence (modified Rankin Scale score [mRS] ≥ 3), the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score at admission, in-hospital interventions (antiplatelet therapy within 48 h and recombinant tissue plasminogen activator), complications in hospital, length of hospitalization, and death in hospital. Additionally, time intervals from stroke onset to the diagnosis of SAP and GIB were calculated.

SAP and GIB were defined as previous studies [11, 15–17]. SAP was defined as clinical and laboratory indices of respiratory tract infection (fever, cough, auscultatory respiratory crackles, new purulent sputum, or positive sputum culture), and supported by typical chest X-ray findings. GIB was defined as clinical (any episode of fresh blood or coffee ground emesis, hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia), laboratory or radiographic evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Statistics analysis

We used mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) to describe characteristics for continuous variables, and percentages for categorical variables. According to the presence of GIB, the patients were categorized into two groups. Chi-square test, Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test was applied to test the difference between groups. To estimate the incidence of SAP and GIB, the number of patients diagnosed with SAP or GIB was as numerator and the number of included patients was as denominator. We used a series of logistic regression models to examine the association between SAP and GIB. In the model 1, no covariate was adjusted. In the model 2, we adjusted age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, smoking, prestroke dependence. In the model 3, we adjusted the covariates in model 2 plus NIHSS score, hepatic cirrhosis, peptic ulcer, and cancer. In model 4, we adjusted the covariates in model 3 plus pre-hospital antiplatelet drug, pre-hospital anticoagulant, antiplatelet therapy within 48 h, intravenous thrombolysis, and length of hospitalization. Considering the non-normal distribution of timing, Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the timing from SAP and GIB. Additionally, a stratified analysis by stroke severity (NIHSS < 16 vs. NIHSS ≥ 16) and infarct location (posterior circulation infarct vs. non-posterior circulation infarct) was performed.

Results

Baseline characteristics and incidence of SAP and GIB

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of patients. From May 2014 to May 2016, a total of 1129 patients with ischemic stroke were enrolled in the study. The mean age was 58.7 ± 2.5 and 899 (79.6%) were male. The median length of hospitalization was 14 days (IQR 11–16). Compared with the patients without GIB, the patients experiencing GIB were more likely to be with a history of atrial fibrillation (17.0% vs. 5.6%, P = 0.001), higher NIHSS score (13 vs. 4, P < 0.001), have longer hospitalization (21 days vs. 13 days, P < 0.001) and higher in hospital mortality (8.5% vs. 0.2%, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in relation to the status of gastrointestinal bleeding

| Overall (N = 1129) |

Without GIB (N = 1082) |

With GIB (N = 47) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.6 ± 12.5 | 58.6 ± 12.5 | 60.6 ± 11.4 | 0.276 |

| Males, n (%) | 899 (79.6%) | 862 (79.7%) | 37 (78.7%) | 0.875 |

| Stroke risk factors, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 755 (66.9%) | 720 (66.5%) | 35 (74.5%) | 0.259 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 341 (30.2%) | 325 (30.0%) | 16 (34.0%) | 0.558 |

| Dyslipidemia | 206 (18.2%) | 202 (18.7%) | 4 (8.5%) | 0.078 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 69 (6.1%) | 61 (5.6%) | 8 (17.0%) | 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 151 (13.4%) | 145 (13.4%) | 6 (12.8%) | 0.900 |

| History of stroke/TIA | 265 (23.5%) | 251(23.2%) | 14 (29.8%) | 0.297 |

| Current smoking | 628 (55.6%) | 601 (55.5%) | 27 (57.4%) | 0.797 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Valvular heart disease | 10(0.9%) | 9 (0.8%) | 1(2.1%) | 0.353 |

| COPD | 26 (2.3%) | 24 (2.2%) | 2 (4.3%) | 0.362 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 8 (0.7%) | 7 (0.6%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.236 |

| Hepatic cirrhosis | 17 (1.5%) | 14 (1.3%) | 3 (6.4%) | 0.005 |

| Peptic ulcer | 21 (1.9%) | 20 (1.8%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.890 |

| Renal failure | 7 (0.6%) | 6 (0.6%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.179 |

| Arthritis | 16 (1.4%) | 15 (1.4%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.674 |

| Cancer | 14 (1.2%) | 13 (1.2%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.574 |

| Medication | ||||

| Antiplatelet drug | 144 (12.8%) | 137 (12.7%) | 7 (14.9%) | 0.653 |

| Anticoagulants | 20 (1.8%) | 19 (1.8%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.850 |

| In-hospital interventions | ||||

| Antiplatelet therapy within 48 h | 1098 (97.3%) | 1057 (97.7%) | 41 (87.2%) | < 0.001 |

| rTPA | 121 (10.8%) | 116 (10.8%) | 5 (10.6%) | 0.977 |

| Admission NIHSS score, median (IQR) | 4 (2–8) | 4 (2–8) | 13 (7–20) | < 0.001 |

| Infarct location | ||||

| Posterior circulation infarct, n (%) | 481 (42.6%) | 454 (40.2%) | 27 (57.45%) | 0.049 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 86 (7.6%) | 62 (5.7%) | 24 (51.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Length of hospitalization (days), median (IQR) | 14 (11–16) | 13 (11–16) | 21 (13–26) | < 0.001 |

| Mortality | 6 (0.5%) | 2 (0.2%) | 4 (8.5%) | < 0.001 |

TIA indicated transient ischemic attack; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; rTPA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; IQR, interquartile range

Overall, 86 patients (7.6%; 95% CI, 6.1-9.2%) developed SAP and 47 patients (4.3%; 95% CI, 3.0-5.3%) developed GIB during hospitalization.

Association between SAP and GIB

The unadjusted regression model indicated that SAP was significantly associated with the development of GIB after AIS (OR = 17.17; 95% CI, 9.17–32.13; P < 0.001). After adjusted for age, gender, and other potential confounders, SAP was still significantly associated with the development of GIB from model 2 to model 4 (Table 2). In the model 4, the odds ratio of development of GIB in the patients with SAP was 5.10 (95% CI, 2.01–12.95) compared with patients without SAP.

Table 2.

Odds ratio (OR) for gastrointestinal bleeding after ischemic stroke

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 17.17 (9.17–32.13) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 20.37 (10.22–40.62) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 7.49 (3.23–17.34) | < 0.001 |

| Model 4 | 5.10 (2.01–12.95) | < 0.001 |

Model 1 is crude model; Mode 2 adjusted for age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, smoking, prestroke dependence (modified Rankin Scale score ≥ 3); Model 3 adjusted for model 2 plus National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, and comorbidities (hepatic cirrhosis, peptic ulcer, cancer); Model 4 adjusted for model 3 plus pre-hospital antiplatelet drug, pre-hospital anticoagulant, antiplatelet therapy within 48 h, intravenous thrombolysis, and length of hospitalization. OR indicates odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Temporal sequence of SAP and GIB after acute ischemic stroke

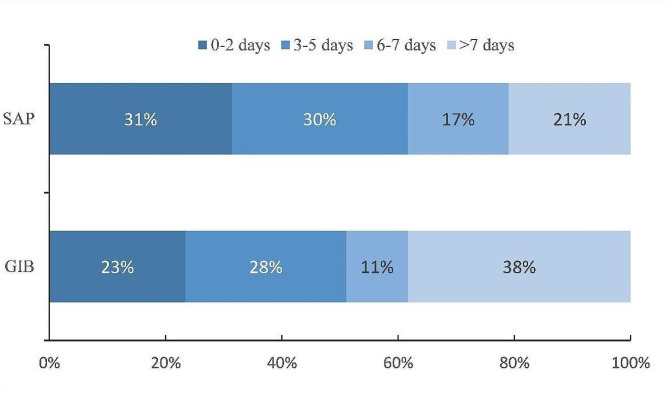

Within the first 48 h from stroke onset, 27 (31.4%) of the patients with SAP and 11 (23.4%) of the patients with GIB were diagnosed. Up to 7 days from stroke onset, 79.1% and 61.7% of patients with PNE and GIB, respectively, was diagnosed with corresponding complications (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The proportion distribution of days from ischemic stroke onset to complications diagnosis in patients with pneumonia and gastrointestinal bleeding. SAP, stroke-associated pneumonia; GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding

The distribution of timing (days) from stroke onset to diagnosis of SAP and GIB are shown in Fig. 2. Overall, the median time from stroke onset to diagnosis of SAP was significantly shorter than that of GIB after acute stroke (4 days vs.5 days; P = 0.039). When the patients were stratified by severity of stroke and infarct location, only in patients with NIHSS ≥ 16 the significant difference was observed (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

The distribution of days from ischemic stroke onset to pneumonia and gastrointestinal bleeding diagnosis. SAP, stroke-associated pneumonia; GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding

Table 3.

Days from stroke onset to diagnosis of pneumonia and gastrointestinal bleeding stratified by NIHSS and infarct location

| Days from stroke onset to diagnosis of SAP, median (IQR) | Days from stroke onset to diagnosis of GIB, median (IQR) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIHSS < 16 | 6 (3–8) | 5 (3–10) | 0.784 |

| NIHSS ≥ 16 | 3 (1–4) | 6 (3–15) | 0.004 |

| Posterior circulation infarct | 5 (2–15) | 4 (2–7) | 0.110 |

| Non-posterior circulation infarct | 4 (2–7) | 5.5 (3-10.5) | 0.154 |

NIHSS indicated National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SAP, stroke-associated pneumonia, GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding

Discussion

In the present study, the incidence of SAP and GIB after stroke was 7.6% and 4.3% during hospitalization. We found that SAP was associated with GIB after ischemic stroke and the time interval from stroke onset to SAP diagnosis was earlier than that of GIB. Our findings suggested that SAP may be a risk factor or risk marker for GIB in patients with ischemic stroke.

Previous studies have identified several risk factors of GIB after ischemic stroke, such as age, previous history of peptic ulcer, severe stroke, hypertension, hepatic cirrhosis, renal failure, and cancer [11, 18, 19]. In the present study, the mean age was older and the proportion of previous peptic ulcer, hypertension, renal failure and cancer was higher in GIB patients compared with non-GIB patients. However, the univariate analysis did not reveal any statistically significant difference in these factors between GIB group and non-GIB group. This may due to small sample size and population characteristics. However, there were few studies investigated the association between SAP and GIB in patients with stroke. Cook, D. J. et al. [20] analyzed 2252 patients admitted to intensive care units and found respiratory failure was one of the strong independent risk factors for GIB. Rumalla, K. et al. [12] examined the association of GIB with other in-hospital complications in patients with AIS and indicated that GIB was significantly associated with SAP. This was consistent with our present study. Additionally, in our previous study, we analyzed 11 common stroke-associated medical complications and observed SAP was strongly associated with the development of GIB after AIS and hemorrhagic stroke [15]. However, all of these studies failed to explore the temporal sequence of SAP and GIB. Stroke can suppress systemic immune response namely immunosuppression, leading to more vulnerable to infection after stroke, such as pneumonia [21, 22]. However, prophylactic antibiotic treatment cannot significantly reduce the risk of SAP, although it may lower the risk of total and urinary tract infections [21]. Recent research suggested that stroke and myocardial infarction can cause a significant loss of intestinal B and T cells through the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and DNase-I therapy may be a potential treatment for patients with stroke [22]. The pathophysiological mechanism through which patients after stroke developed GIB was not entirely understood. Stress, antiplatelet use, systemic inflammation, and oxidative stress have been proposed to illustrate the mechanism of post-stroke GIB [23]. The axis between the central nervous system and gastrointestinal system may be interrupted because of cerebral ischemia, which in turn lead to the gastrointestinal symptoms such as GIB [24]. In a porcine model of peritonitis and hemorrhage, gut blood flow and intramucosal pH were all decreased and the intramucosal pH decrease preceded that of blood flow [25]. A decreasing intramucosal pH was associated with an increased oxygen extraction ratio, which was not sufficient to maintain aerobic metabolism [25]. In critical illness patients, Mutlu, Go˙khan M. et al. [26]. suggested mechanical ventilation (MV) may potentiate the adverse effects of an underlying critical illness and worsen gastrointestinal pathophysiology. They proposed a mechanism for the development of gastrointestinal complications during MV. On the one hand, MV can affect splanchnic blood flow. On the other hand, MV can increase the release of proinflammatory mediators [27]. The proinflammatory mediators have an effect on splanchnic hypoperfusion and may impair intestinal smooth muscle function [28, 29]. Lung injuries or acute respiratory distress syndrome could induce multiple organ dysfunction syndromes by releasing inflammatory mediators into blood [30, 31]. However, the relationship between inflammatory response and SAP and their effect on GIB are complex. The coexistence of inflammatory response after stroke makes it impossible to illustrate whether the SAP directly contributes to the GIB. In our previous study, we hypothesized four stages to explain pathophysiological mechanisms for the interrelationship between SAP and non-SAP complications [15]. Based on this evidence, we suggested a potentially critical role for SAP in the initiation and propagation of systemic inflammatory response which may lead to GIB.

While we are unable to conclude the direct causal relationship between SAP and GIB, the association and temporal sequence for SAP and GIB can guide further research. The pathophysiological mechanism for SAP contributing to GIB after stroke should be studied further. Additionally, it seems reasonable to pay additional attention to patients with SAP after stroke and the prophylactic interventions can be taken to prevent GIB. It was supposed that prophylactic acid suppression therapies, such as H2 antagonists and proton pump inhibitor therapies, may reduce the risk of GIB [11]. However, the evidence on prophylactic medication to prevent GIB in stroke patients was limited. Further clinical studies were needed to evaluate the clinical efficacy of prophylactic acid suppression therapies on GIB after stroke.

To our knowledge, this is the first time to examine the temporal sequence of SAP and GIB in patients with AIS. Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the etiology of GIB was not recorded. Although, previous studies revealed that the bleeding mainly originated in upper gastrointestinal tracts and more than one fifth could not identify despite endoscopic examination [14, 32]. Secondly, the details about severity for SAP and GIB were not reported in consequence of unable to explore whether the dose-response relationship existed. Thirdly, we failed to obtain the information on medication to prevent stress ulcers. Fourthly, since the clinical symptoms of GIB was insidious, it may be not accuracy to define the timing of GIB in terms of diagnosis establishment. The occurrence of disease is a continuous process and it is practicable to the diagnosis timing to define the occurrence of disease. In order to reduce this bias, we used multiple evidence, including clinical, laboratory or radiographic evidence to define the timing of GIB occurred.

Conclusions

In conclusion, GIB after stroke was associated with SAP and the median timing from stroke onset to SAP diagnosis was earlier than that of GIB diagnosis. When the patients after stroke were diagnosed with SAP, it should be paid more attention and take measures to prevent GIB.

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to all participants and investigators of the iMCAS.

Abbreviations

- AIS

Acute ischemic stroke

- SAP

Stroke-associated pneumonia

- GIB

Gastrointestinal bleeding

- NIHSS

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

- mRS

Modified Rankin Scale score

- TIA

Transient ischemic attack

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- rTPA

Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

- IQR

Interquartile range

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- MV

Mechanical ventilation

Author contributions

RJJ, RHZ and YJW were involved in the study design. RHZ and HQH were involved in the drafting of text. RHZ, HQH, RJJ and XQZ were responsible for data collection. XQZ, LPL, YLW,GFL and YJW critically reviewed the drafts. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (L223028), Beijing Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (Grant No. 2020-1-2041, No. 2022-2G-2049), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No. 81471208).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The iMCAS was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Tiantan hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kumar S, Selim MH, Caplan LR. Medical complications after stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:105–18. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingeman A, Andersen G, Hundborg HH, Svendsen ML, Johnsen SP. In-hospital medical complications, length of stay, and mortality among stroke unit patients. Stroke. 2011;42:3214–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.610881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bijani B, Mozhdehipanah H, Jahanihashemi H, Azizi S. The impact of pneumonia on hospital stay among patients hospitalized for acute stroke. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2014;19:118–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong KS, Kang DW, Koo JS, Yu KH, Han MK, Cho YJ, et al. Impact of neurological and medical complications on 3-month outcomes in acute ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:1324–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grube MM, Koennecke HC, Walter G, Meisel A, Sobesky J, Nolte CH, et al. Influence of acute complications on outcome 3 months after ischemic stroke. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e75719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang PL, Zhao XQ, Du WL, Wang AX, Ji RJ, Yang ZH, et al. In-hospital medical complications associated with patient dependency after acute ischemic stroke: data from the China National Stroke Registry. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:1236–41. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.20122573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang P, Wang Y, Zhao X, Du W, Wang A, Liu G, et al. In-hospital medical complications associated with stroke recurrence after initial ischemic stroke: a prospective cohort study from the China National Stroke Registry. Med (Baltim) 2016;95:e4929. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janus-Laszuk B, Mirowska-Guzel D, Sarzynska-Dlugosz I, Czlonkowska A. Effect of medical complications on the after-stroke rehabilitation outcome. NeuroRehabilitation. 2017;40:223–32. doi: 10.3233/NRE-161407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westendorp WF, Nederkoorn PJ, Vermeij JD, Dijkgraaf MG, van de Beek D. Post-stroke infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teh WH, Smith CJ, Barlas RS, Wood AD, Bettencourt-Silva JH, Clark AB, et al. Impact of stroke-associated pneumonia on mortality, length of hospitalization, and functional outcome. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;138:293–300. doi: 10.1111/ane.12956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Donnell MJ, Kapral MK, Fang J, Saposnik G, Eikelboom JW, Oczkowski W, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding after acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2008;71:650–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319689.48946.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rumalla K, Mittal MK. Gastrointestinal bleeding in Acute ischemic stroke: a Population-based analysis of hospitalizations in the United States. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:1728–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou YF, Weng WC, Huang WY. Association between gastrointestinal bleeding and 3-year mortality in patients with acute, first-ever ischemic stroke. J Clin Neurosci. 2017;44:289–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2017.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu HL, Lin YH, Huang YC, Weng HH, Lee M, Huang WY, et al. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage after acute ischemic stroke and its risk factors in asians. Eur Neurol. 2009;62:212–8. doi: 10.1159/000229018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji R, Wang D, Shen H, Pan Y, Liu G, Wang P, et al. Interrelationship among common medical complications after acute stroke: pneumonia plays an important role. Stroke. 2013;44:3436–44. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalra L, Irshad S, Hodsoll J, Simpson M, Gulliford M, Smithard D, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics after acute stroke for reducing pneumonia in patients with dysphagia (STROKE-INF): a prospective, cluster-randomised, open-label, masked endpoint, controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1835–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Z, Lin W, Zhang F, Cao W. Risk factors and prognosis analysis of Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with acute severe cerebral stroke. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2024;58:440–6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji R, Shen H, Pan Y, Wang P, Liu G, Wang Y et al. Risk score to predict gastrointestinal bleeding after acute ischemic stroke. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Cook DJ, Fuller HD, Guyatt GH, Marshall JC, Leasa D, Hall R, et al. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. Canadian critical care trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:377–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402103300601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi K, Wood K, Shi FD, Wang X, Liu Q. Stroke-induced immunosuppression and poststroke infection. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2018;3:34–41. doi: 10.1136/svn-2017-000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuz AA, Ghosh S, Karsch L, Ttoouli D, Sata SP, Ulusoy Ö, et al. Stroke and myocardial infarction induce neutrophil extracellular trap release disrupting lymphoid organ structure and immunoglobulin secretion. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2024;3:525–40. doi: 10.1038/s44161-024-00462-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camara-Lemarroy CR, Ibarra-Yruegas BE, Gongora-Rivera F. Gastrointestinal complications after ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2014;346:20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaller BJ, Graf R, Jacobs AH. Pathophysiological changes of the gastrointestinal tract in ischemic stroke. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1655–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonsson JB, Engstrom L, Rasmussen I, Wollert S, Haglund UH. Changes in gut intramucosal pH and gut oxygen extraction ratio in a porcine model of peritonitis and hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1872–81. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199511000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mutlu GM, Mutlu EA, Factor P. GI complications in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2001;119:1222–41. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.4.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranieri VM, Suter PM, Tortorella C, De Tullio R, Dayer JM, Brienza A, et al. Effect of mechanical ventilation on inflammatory mediators in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:54–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cullen JJ, Ephgrave KS, Caropreso DK. Gastrointestinal myoelectric activity during endotoxemia. Am J Surg. 1996;171:596–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lodato RF, Khan AR, Zembowicz MJ, Weisbrodt NW, Pressley TA, Li YF, et al. Roles of IL-1 and TNF in the decreased ileal muscle contractility induced by lipopolysaccharide. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G1356–1362. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.6.G1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gharib SA, Liles WC, Klaff LS, Altemeier WA. Noninjurious mechanical ventilation activates a proinflammatory transcriptional program in the lung. Physiol Genomics. 2009;37:239–48. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00027.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Del Sorbo L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ failure. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:1–6. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283427295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogata T, Kamouchi M, Matsuo R, Hata J, Kuroda J, Ago T, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding in acute ischemic stroke: recent trends from the Fukuoka stroke registry. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2014;4:156–64. doi: 10.1159/000365245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.