Summary

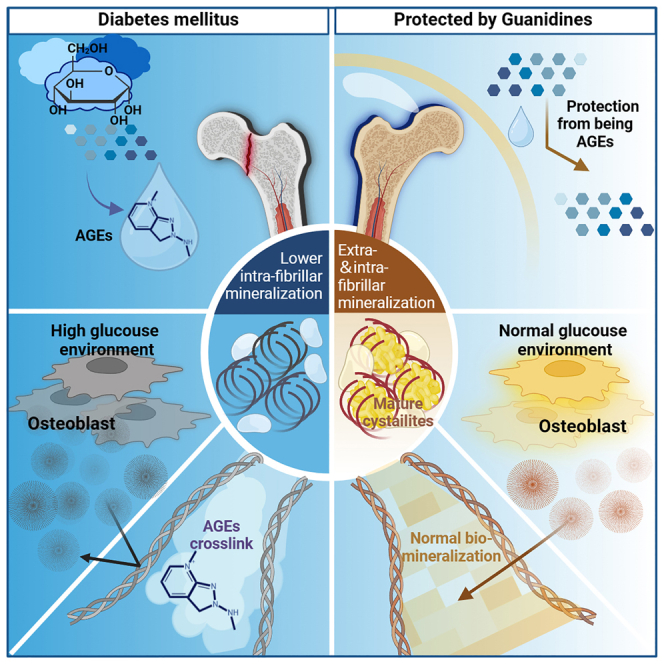

Patients with diabetes often experience fragile fractures despite normal or higher bone mineral density (BMD), a phenomenon termed the diabetic bone paradox (DBP). The pathogenesis and therapeutics opinions for diabetic bone disease (DBD) are not fully explored. In this study, we utilize two preclinical diabetic models, the leptin receptor-deficient db/db mice (DB) mouse model and the streptozotocin-induced diabetes (STZ) mouse model. These models demonstrate higher BMD and lower mechanical strength, mirroring clinical observations in diabetic patients. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) accumulate in diabetic bones, causing higher non-enzymatic crosslinking within collagen fibrils. This inhibits intrafibrillar mineralization and leads to disordered mineral deposition on collagen fibrils, ultimately reducing bone strength. Guanidines, inhibiting AGE formation, significantly improve the microstructure and biomechanical strength of diabetic bone and enhance bone fracture healing. Therefore, targeting AGEs may offer a strategy to regulate bone mineralization and microstructure, potentially preventing the onset of DBD.

Keywords: diabetes bone disease, bone quality, biomineralization, bone fracture, advanced glycation end products, AGEs, collagen mineralization, aminoguandine, metformin, type 2 diabetes mellitus

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) disrupt biomineralization in diabetic bone

-

•

AGEs increase non-enzymatic crosslinking of COL1, blocking mineralization

-

•

Guanidines inhibit AGEs, improving bone quality in diabetes

-

•

Targeting AGEs offers a therapeutic strategy to enhance diabetic bone health

Gao et al. explore the therapeutic implication and underlying mechanism of diabetic bone paradox (DBP). They demonstrate that advanced glycation end products (AGEs) disrupt collagen fibril mineralization in diabetic bones by promoting non-enzymatic crosslinking.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, particularly type 2 diabetes (T2D), presents a multifaceted challenge to bone health.1 Patients with T2D have a 1.9-fold higher risk of fractures compared to non-diabetic individuals.2,3 Paradoxically, despite exhibiting higher BMD, individuals with diabetes demonstrate a higher susceptibility to fractures, and glycemic control does not reduce this fracture risk,4,5 a phenomenon known as diabetic bone paradox (DBP).6,7 Bone quality, which encompasses more than bone quantity, plays a crucial role in this paradox. While often associated with the process of bone biomineralization and microstructure,8,9 bone quality includes a variety of properties that contribute to bone strength, reflecting a comprehensive measure of the bone’s structural integrity and resistance to fractures.10

Biomineralization, the process of depositing hydroxyapatite crystal onto the collagenous matrix primarily composed of collagen I (COL1),11 is essential for bone strength and toughness.12 The collagen scaffold guides the placement of hydroxyapatite, optimizing bone’s mechanical properties.13 In this process, collagen fibrils undergo mineralization both within (intrafibrillar) and outside (extrafibrillar) their structure.14 Intrafibrillar mineralization involves the nucleation and subsequent growth of hydroxyapatite crystals within the gaps of the collagen fibrils where the collagen matrix acts as a template, directing the mineral deposition.15 These intrafibrillar minerals confer tensile strength to the bone.16,17 Conversely, extrafibrillar mineralization occurs on the surface of collagen fibrils, with hydroxyapatite crystals forming independently of the fibrillar structure, contributing to the bone’s compressive strength.18 The nucleation process in extrafibrillar mineralization is less constrained, allowing for the formation of larger and more dispersed mineral aggregates.19 The distinct nucleation and growth mechanisms of intrafibrillar and extrafibrillar mineralization are critical for the mechanical properties of bone and are influenced by various biological and physicochemical factors.20

In diabetes, the biomineralization process is compromised due to the elevated glucose environment. Hyperglycemia disrupts the maturation of osteoblasts, directly impairing bone matrix formation.21 Collagen crosslinking, which includes enzymatic and non-enzymatic processes, is typically influenced by this disruption. Under physiological conditions, enzymatic crosslinks, such as hydroxylysine pyridinoline mediated by lysyl oxidase, are prevalent.22 However, in the pathological state of diabetes, the persistent high-glucose environment fosters the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). These AGEs create non-enzymatic crosslinks between collagen molecules,23,24 which not only affect the mechanical strength of collagen25,26 but also alter the manner of mineral deposition.27 These insights underscore the complex impact of diabetes on bone biomineralization and highlight the importance of understanding these mechanisms to develop effective treatments for improving bone quality in diabetic patients.

Metformin (MET) and aminoguanidine (AG) are well-known derivatives of guanidine. MET, a biguanide class of antidiabetic medications, is primarily used for treating T2D and is noted for its osteogenic properties in addition to its role in lowering plasma glucose levels in diabetic bone diseases (DBDs). MET enhances the expression of osteogenic markers and scavenges reactive oxygen species, facilitating bone formation and mineralization through pathways such as the ROS-AKT-mTOR axis, the AMPK/eNOS/BMP-2 axis, and by suppressing the YAP1/TAZ axis.28,29,30,31 AG, a derivative of guanidine where an amino group replaces one of the hydrogen atoms, is commonly used in age-related bone diseases and sometimes in DBDs.32,33 It is recognized for its inhibitory effect on the formation of AGEs and is reported to indirectly promote osteogenesis. Although the impact of AGEs on bone quality has been partially explored, existing research has yet to fully elucidate the mechanisms underlying the DBP.34

Therefore, from a proof-of-concept perspective, we hypothesize that abnormal crosslinking of COL1 inhibits the intrafibrillar mineralization of collagen in bone, thereby compromising bone microstructure and bone quality. By examining bones from diabetic patients and mouse models, including db/db (DB) mice and streptozotocin (STZ) mice, we explored the nuances of mineral distribution in diabetic bone and demonstrated how AGEs mediated abnormal collagen crosslinking, which then inhibited intrafibrillar mineralization. Additionally, guanidines were employed in the healing of diabetic bone fractures to verify the practicability of this mechanism. The therapeutic effects of guanidines were significant, notably in inhibiting the accumulation of AGEs. We utilized both in vitro and in vivo models to investigate the underlying mechanisms of the DBP, focusing on the role of AGEs in disrupting collagen biomineralization, and identified guanidines as potential therapeutic agents for DBD. This paper offers insights into the understanding of DBP and potential therapeutic interventions, highlighting the efficacy of guanidines in improving bone quality by mitigating AGE-related damage.

Results

Diabetic bone shows higher bone mineral density but lower bone strength

To better understand DBD, we utilized two mouse models that closely mimic the conditions observed in clinical diabetic patients.4,5 As illustrated in Figure S1, patients with T2D have a slightly higher bone mineral density (BMD) than the control group. The DB mouse model and the STZ mouse model were established for the investigation of diabetic osteopathy.35 Compared to normal wild-type (WT) mice, both DB and STZ mice exhibited elevated weight and blood glucose levels, confirming the successful induction of diabetic conditions (Figures S2A–S2C, S5C, and S5D).

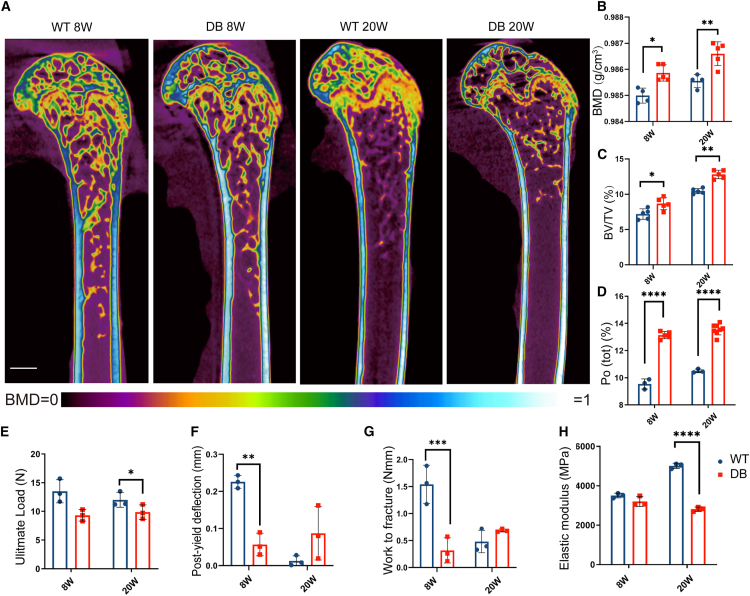

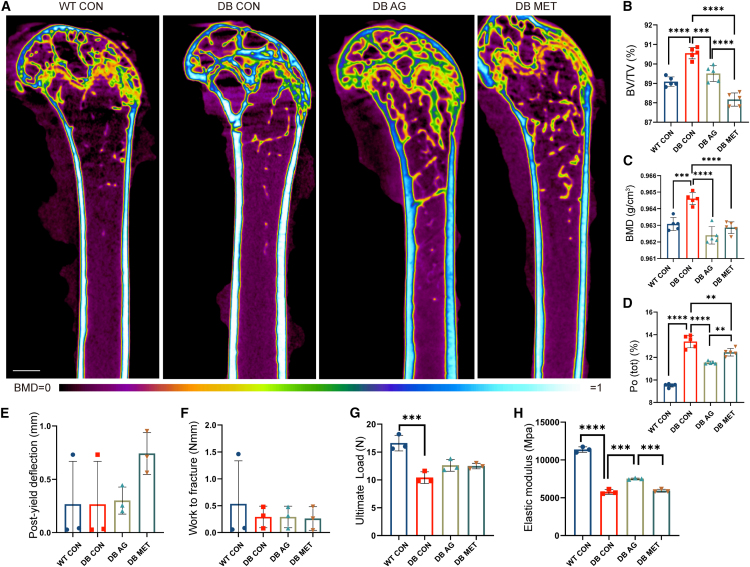

Micro-computed tomography (μCT) analysis of the right femurs from 8- and 20-week-old WT and DB mice revealed a higher BMD in DB mice (Figures 1A, 1B, S5A, S5B, and S5E), despite a minor reduction in trabecular BMD (Figure S3C). Both the 8- and 20-week-old diabetic groups demonstrated an elevated bone volume to tissue volume ratio (BV/TV) in cortical bone shaft (Figures 1C and S5F) but with diminished structural integrity,36 indicated by reduced structural thickness (Figure S3B). By 20-week mark, DB group exhibited higher cortical bone porosity (Figures 1D and S5G), alongside variations in trabecular bone metrics, including thickness, number, and separation (Figures S3D–S3F), suggesting significant alterations in bone microstructure attributable to the diabetic condition.

Figure 1.

Diabetic mice show higher bone mineral content and lower bone strength

(A) Representative μCT reconstruction images of the right femurs from 8- and 20-week-old WT and DB groups with pseudo color (present BMD from 0 to 1); bar, 1 mm; WT, wild-type mice; DB, db/db mice.

(B) BMD of the femur shafts from WT and DB groups; n = 5 for each group; BMD, bone mineral density.

(C) BV/TV of the femur shafts from WT and DB groups; n = 5 for each group; BV, bone volume; TV, tissue volume.

(D) Po (tot) of the cortical femur shafts from WT and DB groups; n = 5 for each group; Po (tot), total porosity (percent).

(E–H) Quantitative analysis of the right femurs from WT and DB groups in three-point bending test; n = 3 for each group. Data were represented as mean ± SD (error bars) from biological replicates; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. Those not marked showed statistically no significant differences. See also Figures S1–S5.

To assess the functional implications of these microstructural alterations, we performed three-point bending test (Figures S4A and S4B), analyzing the mechanical properties of whole right femurs derived from WT, DB, and STZ mice (Figures S4C–S4F, S5B, and S5C). According to load-deflection curves, DB mice showed a significantly lower ultimate load at 20 weeks (Figure 1E) and a significantly lower fracture load at 8 weeks (Figure S4H) than WT mice, suggesting that the femurs from DB mice could withstand lower force before failing. The DB group showed a significantly lower post-yield deflection at 8 weeks (Figure 1F), while the STZ mice exhibited higher post-yield deflection at 20 weeks (Figure S5L) than WT mice, suggesting the post-yield deflection might change by age in diabetic mice. WT mice maintained higher work-to-fracture values compared to both DB and STZ mice at 8 weeks (Figures 1G and S5M). The elastic modulus of DB and STZ groups were significantly lower at 8 weeks and 20 weeks (Figures 1H and S5N), implying that the femurs are more deformable under stress in this condition compared to WT groups.

Similar patterns were observed in both DB groups and STZ counterparts, corroborating the adverse impact of diabetes on bone mechanical properties, as supported by both our in vitro assessments and corroborative clinical data from other studies. Studies have consistently shown a decrease in bone material strength index (BMSi) among T2D, which occurs despite often higher BMD measurements. For instance, a study involving different racial groups with early-stage diabetes demonstrated BMSi notably declined in blacks with T2D.37 Another investigation focusing on postmenopausal women with T2D revealed a marked reduction in BMSi,38 with values decreasing from 78.2 ± 7.5 in controls to 74.6 ± 7.6 in diabetic subjects. Similarly, research conducted on elderly women with T2D reported a decrease in BMSi from 78.2 ± 7.5 in non-diabetics to 74.6 ± 7.6 in diabetics,39 despite these patients presenting higher areal BMD. These data collectively suggest a significant deterioration in bone material properties in diabetic patients, contributing to an elevated fracture risk, and underscore the importance of evaluating bone quality in addition to density in this patient population.

Diabetic bone shows irregular mineral deposition and collagen fibril distribution

To gain deeper insights into the microstructural alterations within diabetic bone, femoral cortical bone from WT, DB, and STZ mice groups was scrutinized, as indicated by previous studies.13,40 The human skeletal system exhibits a complex hierarchical microarchitecture that spans multiple dimensional scales. At the most fundamental level, this architecture comprises COL1 fibrils, which can extend up to 15 μm in length and measure between 50 and 70 nm in diameter. These fibrils are intertwined with and embedded by carbonated hydroxyapatite nanocrystals, typically tens of nanometers in length and 2–3 nm in width, forming the essential building blocks of bone structure.41

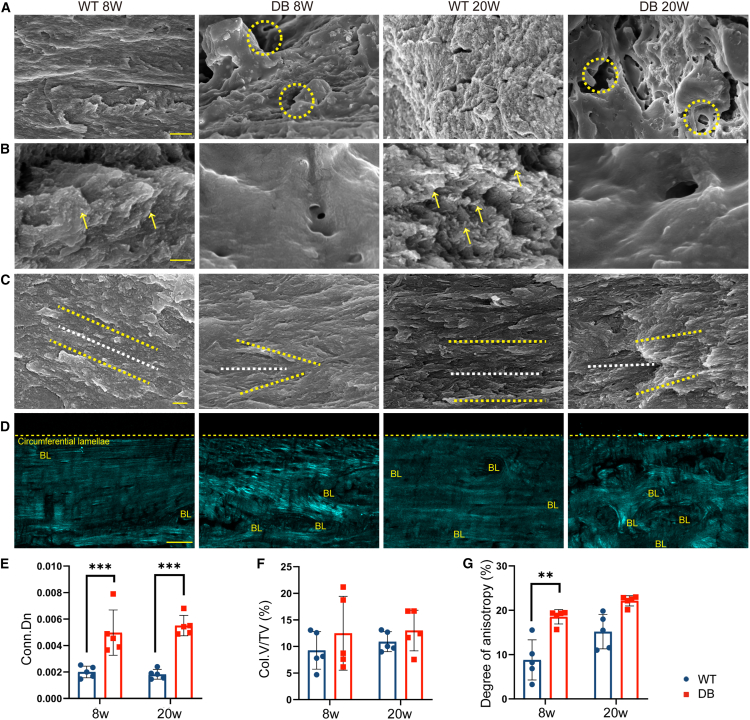

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images provided qualitative evidence of cross-fracture surfaces prepared under three-point bending test42 and longitudinal fracture surfaces prepared with the assistance of liquid nitrogen freezing43 (Figures 2A, 2B, S6A, and S6B). Notably, in the lower resolution cross-section images (Figures 2A and S6A), more pronounced pores were in the DB and STZ groups. In the higher resolution cross-section images, pronounced deformations and tearing of mineralized collagen fibrils were evident in WT groups due to fracture, while fibrils in DB and STZ groups were covered with obvious organic matters presenting a smooth surface44 (Figures 2B and S6B), which may indicate poor integration of collagen and minerals.45

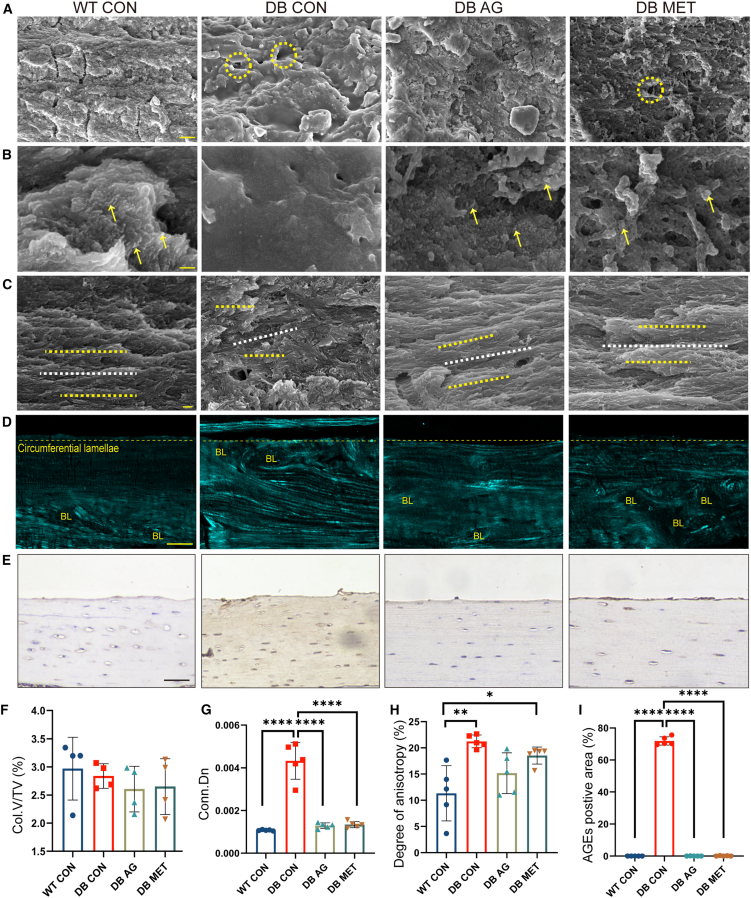

Figure 2.

Diabetic bones show mineralization disorder

(A) Representative SEM images with lower resolution of cross-section of cortical bone samples from WT 8W, DB 8W, WT 20W, and DB 20W groups; yellow hollow circles mark cortical bone pores; bar, 1 μm; WT, wild-type mice; DB, db/db mice; W, week.

(B) Representative SEM images with higher resolution of cross-section of cortical bone samples from WT 8W, DB 8W, WT 20W, and DB 20W groups; yellow arrows represent the broken ends of collagen fibrils; bar, 100 nm.

(C) Representative SEM images of longitudinal section of cortical bone samples from WT 8W, DB 8W, WT 20W, and DB 20W groups; both white and yellow lines mark the orientation of adjacent mineralized collagen in circumferential lamellae of cortical bone; bar, 10 μm.

(D) Representative BSHG images of femur slices from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; the dashed lines mark the edges of the cortical bone; bar, 100 μm. BL, bone lacunae.

(E–G) Quantitative analysis of the BSHG images in (D); n = 5 for each group; Conn.Dn, connected density; Col.V, collagen volume; TV, tissue volume. Data were represented as mean ± SD (error bars) from biological replicates; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. Those not marked showed statistically no significant differences. See also Figures S6 and S7.

The templating effect of the collagen matrix normally guides the longitudinal alignment of hydroxyapatite crystals within the fibrils, paralleling the collagen fibrils themselves. Outside the fibril, most extracellular minerals also align with these fibrils, although localized variations in alignment are observed in the less ordered regions of bone. The crystals, both intra- and extrafibrillar, generally measure 2 to 7 nm in thickness, 10 to 80 nm in width, and 15 to 200 nm in length.46 However, longitudinal section images underscored a mismatch in the direction of adjacent collagen fiber alignment in DB and STZ groups compared to WT groups in Figures 2C and S6C. This misalignment indicates altered mineralization processes in diabetic bone, including the deposition of minerals and the quantity of minerals.

As mentioned, the location of mineralization is closely related to the collagen template. The collagen crosslinking density plays a crucial role on tissue mechanical properties and integrity, which may be significantly altered in various pathological conditions. Second harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy enables the quantification of these changes by exploiting the non-linear optical properties of collagen, where the intensity of the SHG signal is closely related to the organization and density of collagen fibrils. Comparative research employing SHG microscopy across different diseases has highlighted the versatility of this technique in revealing disease-specific alterations in collagen structure. For instance, in liver fibrosis, SHG imaging has highlighted the excessive accumulation and altered organization of collagen fibrils, contributing to tissue stiffness and impaired function.47 Similarly, in cancer, SHG microscopy has been used in identifying changes in tumor microenvironment, particularly the desmoplastic reaction characterized by higher collagen deposition and crosslinking, which influences tumor progression and metastasis.48

In our study, collagen structure in diabetic bone was further analyzed using multimodal microscopy utilizing backward SGH (BSHG) signals allowed for the visualization of COL1 within the cortical bone matrix (Figure 2D). An increase in collagen crosslinking density was quantized by the connected density (Conn.Dn) of COL1 and noted under diabetic conditions (Figure 2E). However, the collagen volume to tissue volume ratio (Col.V/TV) remained unchanged (Figure 2F), indicating no significant alteration in collagen quantity. The degree of anisotropy measurements pointed to a marked disorganization in collagen arrangement, particularly within the outer lamellar layers of diabetic cortical bone (Figure 2G).

Considering that mineralization process in the precursor of osteogenesis cells, we explored the MC3T3-cell-mediated mineral deposition under different glucose concentrations in vitro. Generally, the glucose concentration of cell culture medium, except tumor cells, is 1 g/L. Culture medium with high glucose (HG) usually means the glucose concentration is 4.5 g/L. For contrast, we added ultra-HG concentration of 10 g/L group. MC3T3 pre-osteoblasts were osteogenically induced for 21 days using varying glucose concentrations as controls (Figure S7). Observations included a higher extracellular release of dark calcium-containing vesicles, cell collapse, and apoptosis (Figures S7A and S7B) in cell slices, with the most vesicle release observed in the media with a 4.5 g/L concentration of glucose and the most apoptosis phenomenon in the media with a 10 g/L concentration of glucose. Accumulation of AGEs was primarily noted in culture media than cell lysate (Figures S7C and S7D). Osteogenically induced MC3T3 cells cultured in the medium with a glucose concentration of 4.5 g/L also resulted in the highest alkaline phosphatase (ALP) production and mineral secretion, as demonstrated by ALP and alizarin red S (ARS) staining and corresponding quantitative analyses (Figures S7E–S7H). Therefore, a culture medium with a glucose concentration of 4.5 g/L was selected as the in vitro HG model for the following study.

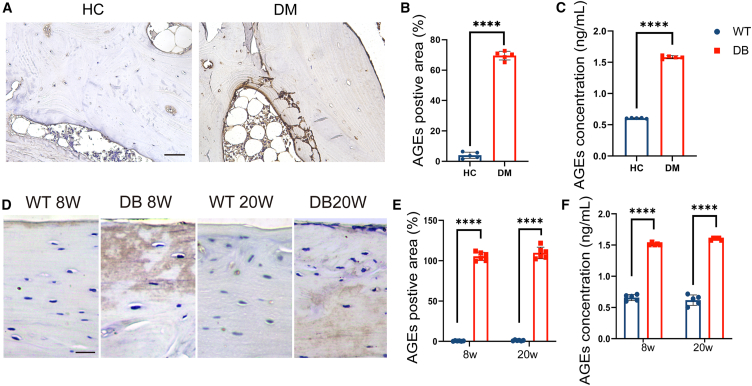

Diabetic bones show higher AGE accumulation

AGEs are one of the key factors contributing to the increase in collagen crosslinking density. To discern the presence of AGEs within cortical bone, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for AGEs was employed. The diabetic bone from T2D patient and diabetic mice groups displayed more stained area of AGEs compared to non-diabetic controls (Figures 3A, 3D, and S8A). Quantitative analysis demonstrated that both at 8 weeks and 20 weeks, the diabetic cortical bone contained significantly higher positive area of AGEs when compared to the control group (Figures 3B, 3E, and S8B). The concentration of AGEs in bone samples was quantitatively assessed using an ELISA assay, which showed that diabetic groups had approximately a 3-fold increase in AGE concentration compared to normal groups (Figures 3C, 3F, and S8C).

Figure 3.

AGE accumulation analysis in the cortical bones of diabetic human and mice

(A) Representative IHC-staining images of AGEs in human cortical bone fragments from HC and DM fracture patients; Areas stained brown represent locations of positive staining; bar, 100 μm. HC, healthy control; DM, diabetes mellitus; AGEs, advanced glycation end products.

(B) Positive area of the AGEs stained in the IHC images as quantitative measurements; n = 5 for each group.

(C) AGE ELISA analysis of proteins from in human cortical bone fragments of HC and DM fracture patients. n = 5 for each group.

(D) Representative IHC-staining images of AGEs in right femur slices from WT and DB groups. Areas stained brown represent locations of positive staining; bar, 50 μm; WT, wild-type mice; DB, db/db mice; W, weeks.

(E) Positive area of the AGEs stained in the IHC images in (D) as quantitative measurements; n = 5 for each group.

(F) AGE ELISA analysis of proteins from WT and DB groups; n = 5 for each group. Data were represented as mean ± SD (error bars) from biological replicates; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, by non-paired Student’s t test for B and C and by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test for E and F. See also Figure S8.

In the in vitro cell experiments, ELISA results indicate the highest level of AGEs is in the lysate of osteogenically induced MC3T3 cells cultured in the medium with a glucose concentration of 4.5 g/L. In contrast, the highest level of AGEs was detected in the culture medium with a glucose concentration of 10 g/L (Figures S7C and S7D). This phenomenon may be due to the rupture of the cells in the ultra-HG environment, leading to the release of intracellular AGEs into the culture medium.

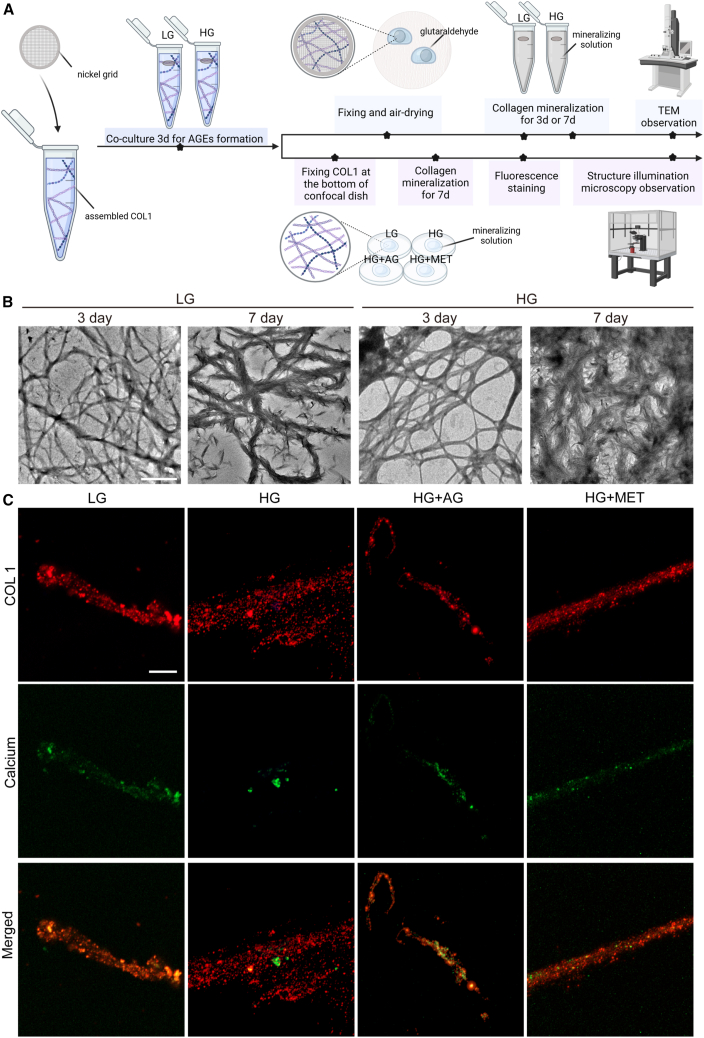

AGE crosslink inhibits intrafibrillar mineralization of collagen

To explore whether mineral precursors penetrate well into collagen fibrils with higher Conn.Dn in HG,49 intrafibrillar and extrafibrillar mineralization of collagen have been characterized following the method in Figure 4A. Collagen mineralization typically progresses through three stages50,51: an initial stage where amorphous calcium phosphate enters the collagen for mineralization preparation; a second stage where signs of collagen mineralization appear in some regions (Figure 4B) for low glucose (LG; 1 g/L) and HG (4.5 g/L), respectively; and a third stage where extensive mineralization on the collagen is apparent, with complete mineralization achieved (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

AGE accumulations in HG lead to lower collagen intrafibrillar mineralization, and inhibition of AGE accumulations by guanidines increases collagen intrafibrillar mineralization

(A) Schematic diagram of in vitro collagen mineralization; COL1, collagen I; LG, low glucose concentration; HG, high glucose concentration; AG, aminoguanidine; MET, metformin; d, day(s); TEM, transmission electron microscope.

(B) Representative TEM images of collagen after mineralization for 3 and 7 days under LG or HG; bar, 1 μm.

(C) Representative SIM images of collagen after mineralization for 7 days; bar, 100 nm; SIM, structure illumination microscopy.

The triple-helix structure of collagen results in characteristic dark and light bands on transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images, with approximately 67 nm gaps.52 Amorphous calcium phosphate can enter these bands and transform into regular plate-like hydroxyapatite, which fills the gap zone and causes the banding pattern to disappear.53 In the extrafibrillar zones, minerals accumulate around crystalline nuclei.52 In LG conditions, mineralized collagen appears to have a higher contrast to background, while the HG one showed a lower contrast to background (Figure 4B). The TEM micrographs indicate that collagen fibrils with low crosslinking density in LG may be penetrated with more minerals, indicating more intrafibrillar mineralization, although definitive conclusions are challenging as the gap zones are obscured by extrafibrillar minerals.

Structure illumination microscopy further examined the mineralization process in collagen fibrils, where the LG group showed a fusion of red and green fluorescence, indicative of normal mineralization. Conversely, the HG group displayed distinct red and green fluorescence without fusion, suggesting impeded mineral penetration in high-glucose conditions (Figure 4C).

To assess the impact of AGEs on mineralization, AGE formation inhibitors, guanidines, AG,54 and MET,55 were introduced. The re-emergence of yellow fluorescence in the presence of these inhibitors suggested that preventing AGE formation could facilitate intrafibrillar mineralization (Figure 4C). The inhibitory effect of AG on AGEs was more pronounced than that of MET, as evidenced by the yellow fluorescence intensity on the images, highlighting its therapeutic potential in improving bone mineralization by targeting AGEs.

Overall, our observation indicates that under diabetic conditions, the accumulation of AGEs correlates with a higher crosslinking density of collagen fibrils, which impedes the intrafibrillar mineralization process, thereby affecting the structural integrity and mechanical strength of the bone. The effect of guanidines will be discussed in detail in Figure 6B.

Figure 6.

Guanidines reduce AGE accumulation and improve bone mineralization and collagen arrangement in diabetic bone

(A) Representative SEM images with lower resolution of cross-section of cortical bone samples from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups. Yellow hollow circles mark cortical bone pores; bar, 1 μm; WT, wild-type mice; DB, db/db mice; CON, control; AG, aminoguanidine; MET, metformin.

(B) Representative SEM images with higher resolution of cross-section of cortical bone samples from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; yellow arrows represent the broken ends of collagen fibrils; bar, 100 nm.

(C) Representative SEM images of longitudinal section of cortical bone samples from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; both white and yellow lines mark the orientation of adjacent mineralized collagen in circumferential lamellae of cortical bone; bar, 10 μm.

(D) Representative BSHG images of femur slices from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; The dashed lines mark the edges of the cortical bone; bar, 100 μm. n = 5 for each group; BL, bone lacunae.

(E) Representative IHC-staining images of AGEs; Areas stained brown represent locations of positive staining; bar, 50 μm.

(F–H) Quantitative analysis of the BSHG images in (D); n = 5 for each group; Conn.Dn, connected density; Col.V, collagen volume; TV, tissue volume.

(I) Positive area of the AGEs stained in the IHC images in (E) as quantitative measurements; n = 5 for each group. Data were represented as mean ± SD (error bars) from biological replicates; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, by one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-test. Multiple comparisons included “WT CON vs. DB CON,” “DB CON vs. DB AG,” “DB CON vs. DB MET,” and “DB AG vs. DB MET.” Those not marked showed statistically no significant differences. See also Figures S11–S13.

Guanidine restores bone mass and biomechanical integrity in diabetic mice

We conducted an in vivo study to explore whether oral medication of guanidines improves diabetic bone quality in DB mice. Blood glucose and body weights of the mice were monitored (Figures S9A and S9B), including WT mice as a control (WT CON), DB mice as a diabetic control (DB CON), DB mice treated with AG (DB AG), and DB mice treated with MET (DB MET) from 8 to 20 weeks, with representative μCT pictures shown in Figure 5A.

Figure 5.

Guanidines improve bone microstructure and mechanical properties in DB mice

(A) Representative μCT reconstruction images of the right femurs from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups with pseudo color (present BMD from 0 to 1); bar, 1 mm; WT, wild-type mice; DB, db/db mice; CON, control; AG, aminoguanidine; MET, metformin.

(B) BV/TV of the whole right femur shafts from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; n = 5 for each group; BV, bone volume; TV, tissue volume.

(C) BMD of the cortical femur shafts from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; n = 5 for each group; BMD, bone mineral density.

(D) Po (tot) of the cortical femur shafts from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; n = 5 for each group; Po (tot), total porosity (percent).

(E–H) Quantitative analysis of right femurs from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups in three-point bending test; n = 3 for each group. Data were represented as mean ± SD (error bars) from biological replicates; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, by one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-test. Multiple comparisons included “WT CON vs. DB CON,” “DB CON vs. DB AG,” “DB CON vs. DB MET,” and “DB AG vs. DB MET.” Those not marked showed statistically no significant differences. See also Figures S9 and S10.

The DB CON group exhibited similar microstructures as those shown in Figure 1, including higher BV/TV, BMD, and total porosity (Po (tot)), serving as indicators of diabetic bone. DB AG showed substantial improvements, such as lower BV/TV, Po (tot), and BMD compared to DB CON (Figures 5B–5D). The DB MET also changed bone microstructure in DB mice (Figures 5B–5D), displaying lower BV/TV (Figure 5B) and higher BMD (Figure 5C) than DB AG group, which may be due to the complex effects of MET, including reducing blood glucose (Figure S9A) on the whole organism. DB AG has a significantly lower Po (tot) compared to DB MET (Figure 5D).

The analysis of load-deflection curve of three-point bending test in Figures S10A–S10D revealed no significant differences between the groups in post-yield deflection (Figure 5E) and work to fracture (Figure 5F). These results were consistent with the previous finding of these 2 parameters having no significant difference between WT and DB mice at 20 weeks (Figures 1F and 1G). Notably, oral medication with AG enhanced the fracture load (Figure S10F) and elastic modulus (Figure 5H) but did not show obvious enhancement in yield load (Figure S10E) and ultimate load (Figure 5G) in diabetic bone, underscoring the therapeutic promise of AG in vivo. Conversely, the parameters of DB MET group showed no significant difference from DB CON (Figures 5G and 5H), the deep reasons for which are unknown and warrant further exploration.

Guanidines decrease AGE accumulation and protect collagen structure in diabetic bone

To characterize the effect of guanidine on microstructural changes and AGE accumulation, we analyzed bone samples from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups. In a set of SEM images, we mainly observed the microstructural differences in the cross-sections of the cortical femurs of DB AG and DB MET compared to the DB CON. The SEM images of WT CON and DB CON (Figures 6A and 6B), respectively, had a similar overview and zoomed-in field with those of WT and DB mice at 20 weeks of age in Figures 2A and 2B. Briefly, SEM images of DB CON demonstrated a cross-section with more pores (Figure 6A) and covered by more organic matter (Figure 6B) than WT CON. After treatment with MET, there appears to be a reduction in the number of pores, while in the AG-treated DB mice, the porous structures seem to be more extensively repaired, as highlighted by the dashed yellow circles (Figure 6A). In the high-resolution images (Figure 6B), the WT group’s mineralized collagen fibrils show noticeable deformation and tearing (pointed out by yellow arrows). In contrast, the surface of the DB CON group is smoother, which may indicate a covering of organic matters. The fibrils in both the AG and MET treatment groups also display varying degrees of higher fibril deformation and tearing. The longitudinal section images (Figure 6C) underscored an improved mismatch in the direction of adjacent collagen fibril alignment in the DB AG and DB MET groups compared to the DB CON groups. In parallel, TEM observation on bone ultra-thin slice demonstrated similar results (Figure S11).

BSHG analysis provides insights into the non-linear optical properties of collagen, further demonstrating the impact of guanidines on collagen structure in diabetes. Both DB AG and DB MET group presented lower signal on typical BSHG images (Figure 6D), indicating the partial recovery of normal collagen structure and lower crosslinking density (Figure 6F). The Col.V/TV analysis showed no difference among groups (Figure 6G), indicating that the change of BSHG signal is not for collagen volume. The Conn.Dn analysis shows that AG/MET treatment obviously inhibits the AGE formation and improves collagen arrangement of bone in diabetic mice (Figure 6H).

AGE staining was also used to demonstrate the accumulation of AGEs within the bone matrix (Figure 6E). The DB control group exhibited a marked increase in AGE content compared to the WT group, aligning with the known relationship between diabetes and AGE accumulation. Treatment with AG and MET in DB mice reduced AGEs levels, with AG providing a more substantial decrease (Figure 6E), and the quantitative analysis showed the same results (Figure 6I).

We investigated the effects of guanidines on the osteogenic induction process of MC3T3-E1 cells. The beneficial effect of AG on regulating bone biomineralization did not stem from promoting mineral production from the ALP and ARS staining as well as qualitative analysis (Figures S12A–S12F). The groups treated with AG and the untreated group showed similar outcomes, while MET showed a slight enhancement in mineral production. Particularly, representative micrographs of the AG group displayed fewer instances of cellular breakdown (Figure S12A). In the cell culture media, both AG and MET significantly reduced the production of AGEs (Figure S12B).

To further investigate the protective effect of guanidine on AGE-binding sites, we contrasted high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry analysis of treated groups to untreated groups. After treatment with guanidine, the glucose-binding sites (G, marked in blue) between lysine and arginine (K-R) on both the α1 and α2 chains of COL1 were reduced, suggesting that guanidine was effective in reducing AGEs formation within collagen (Figure S13).

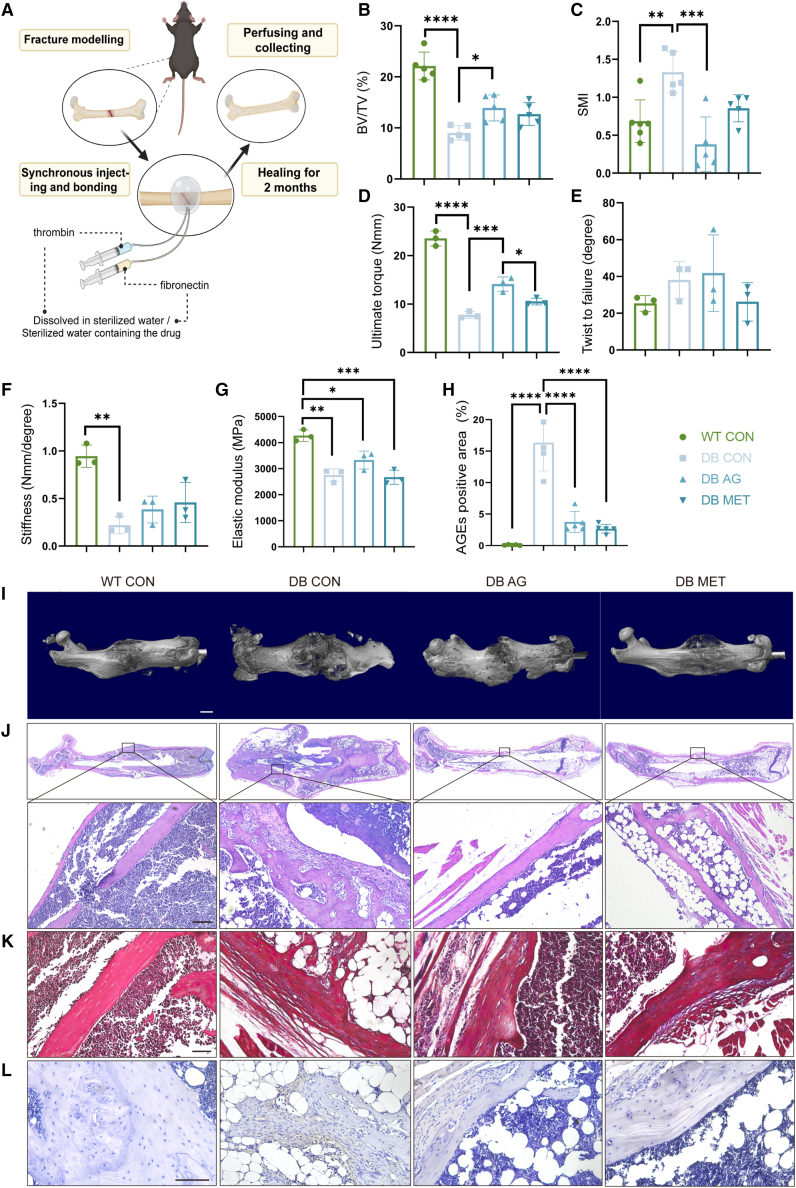

Guanidines promote bone fracture healing in diabetic mice

Fracture healing is impaired in patients with diabetes. To investigate the effectiveness of guanidines in enhancing fracture healing in diabetes, we established a fracture model in the femurs of 8-week-old mice, including WT, DB, and STZ mice. Fractures were locally treated with a fibrin adhesive containing either AG or MET or left untreated (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Guanidines promote bone fracture healing in diabetic mice

(A) Schematic diagram of fracture modeling and drug treatment patterns in mice models.

(B and C) Quantitative analysis of the callus of fractured right femurs from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; n = 5 for each group; WT, wild-type mice; DB, db/db mice; CON, control; AG, aminoguanidine; MET, metformin.

(D–F) Quantitative analysis of torsion test of healed fracture right femurs from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; n = 3 for each group.

(G) Elastic modulus analysis of three-point bending test of healed fracture right femurs from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; n = 3 for each group.

(H) Positive area of the AGEs stained in the IHC images in (D) as quantitative measurements; n = 5 for each group; AGEs, advanced glycation end products.

(I) Representative μCT reconstruction images of healed fracture right femurs from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; bar, 10 mm.

(J) H&E staining images of healed fracture femur slices from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; n = 5 for each group; bar, 10 mm (above) and 1 mm (down).

(K) Masson staining images of healed fracture femur slices from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; n = 5 for each group; bar, 1 mm.

(L) Representative IHC-staining images of AGEs of healed fracture femur slices from WT CON, DB CON, DB AG, and DB MET groups; areas stained brown represent locations of positive staining; bar, 1 mm. Data were represented as mean ± SD (error bars) from biological replicates; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.000, by one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-test. Multiple comparisons included “WT CON vs. DB CON,” “DB CON vs. DB AG,” “DB CON vs. DB MET,” and “DB AG vs. DB MET.” Those not marked showed statistically no significant differences. See also Figures S14–S16.

After 2 months, μCT analysis showed enhanced bone bridging and integration at the fracture sites in the guanidine-treated groups, with images displaying more continuous cortical bone (Figure 7I). Quantitative data revealed higher BV/TV ratios in guanidine-treated groups in callus tissues (Figure 7B) and structure model index values decreased, indicating a transition toward a healthier, plate-like woven bone structure (Figure 7C).

The biomechanical properties were assessed using torsion and three-point bending tests. In the torsion test, significant differences were observed across the groups. The WT control group exhibited the highest ultimate torque, while the DB and STZ control groups showed a marked reduction, indicating diabetes-induced compromise in bone strength during the fracture healing process (Figures 7D and S15H). AG treatment led to significantly higher ultimate torque in DB mice, suggesting an improvement in bone integrity, while MET treatment resulted in a less pronounced improvement (Figure 7D). Twist to failure measurements showed no significant change in the torsional angle before failure across the groups (Figure 7E). Stiffness measurements confirmed that WT control mice bones had superior stiffness, whereas diabetic groups showed notably reduced stiffness (Figure 7F). Both AG and MET treatments in DB and STZ groups led to slight enhancements in stiffness, though not to the level of WT controls (Figures 7F and S15J).

Additionally, three-point bending tests revealed significant increases by AG and MET treatment in yield load (Figure S15D), elastic modulus (Figure S15G), and work to fracture (Figure S15I) in the STZ groups, further suggesting enhanced resistance to bending forces and greater bone toughness.

Histological examinations using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome staining showed more mature and compact callus structures and higher collagen formation in guanidine-treated fractures, indicative of advanced healing stages (Figures 7J, 7K, S16A, and S16B). IHC staining for AGEs demonstrated reduced AGE accumulation in the callus of guanidine-treated groups compared to diabetic controls (Figures 7H, 7L, S16C, and S16D).

Overall, the data suggest that AG has a more significant impact on the biomechanical properties and healing quality of fractured bones in diabetic conditions compared to MET. These results were consistent in STZ-induced diabetic mice, supporting the broader applicability of the findings (Figures S15 and S16).

Discussion

The DBP, which refers to higher risks of bone fractures and osteoporosis along with normal or higher BMD,4 causing underrated fracture risk assessment tool in T2D, has been a clinical concern for years.56,57 Not only is BMD important, but also bone quality is an important factor in determining bone strength. Several studies have highlighted the intricate relationship between diabetes and bone. For instance, Compston et al. emphasized the impact of T2D on bone health, suggesting potential underlying mechanisms that reduced lumbar spine trabecular bone score, reduced BMSi in cortical bone, or accumulation of AGEs in bone, which could explain the higher fracture risk from a different perspective rather than BMD.6 Sieverts et al. suggested that factors beyond BMD, such as collagen damage, should be considered when studying fracture in bone.58 However, these studies do not provide a clear explanation for the contradiction between higher bone mass and lower bone strength.

Collagen crosslinking is a determinant for bone quality. Crosslinks can form enzymatically through the action of lysyl oxidase or non-enzymatically, resulting in AGEs. Schwartz et al. explored the role of pentosidine, a typical AGE crosslink, in elevating fracture risk among older adults with T2D.59 AGE crosslinking is widely believed to adversely affect the primary mineralization process. Regarding secondary mineralization, Paschalis firstly reported that the crosslink ratio of collagen was positively correlated with the thickness of mineral deposits in trabecular bone.60 Saito et al. further found that non-enzymatic crosslinking in both low and high-mineralized bone results in impaired quality of cancellous bone in the hip in cases of patients with osteoporosis-related fractures.61 However, no studies have yet addressed whether AGE crosslinks alter the behavior of collagen mineralization during secondary mineralization.

In conclusion to our study, we found that abnormal crosslinking of COL1 hinders collagen’s intrafibrillar mineralization in bone, adversely affecting bone quality. To be specific, AGE accumulation leads to the increase of non-enzymatic crosslink of collagen,62 which inhibits the penetration of mineral precursors, like amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP), into collagen fibers and decreases the intrafibrillar mineralization. While the mechanical strength of collagen fibrils is not effectively enhanced due to the decreased intrafibrillar mineralization.63 Meanwhile, increased non-enzymatic crosslink also contributes to disordered collagen arrangement, which induces disordered mineral deposition and decreases bone quality. Thus, the diabetic biomineralization paradox is reasonable; the mineral production is promoted by HG, which explains the increase of BMD (Scheme 1).

Bone microstructure and biomechanics

μCT analysis in our study demonstrated a higher BMD in diabetic models, a paradoxical finding often observed in diabetic patients and referred to as the “DBP.”7,24 This observation supports the conclusions of Leslie and Rubin,64 who argued that BMD fails to account for bone quality factors such as collagen crosslink and mineralization patterns, which are critical determinants of bone strength, especially in diabetic conditions.

Additionally, our findings of altered cortical and trabecular microarchitecture in diabetic bones, including higher porosity and compromised trabecular connectivity, provide insight into the structural basis for the observed mechanical weaknesses. These microstructural changes are consistent with the work of Saito and Marumo, who noted that diabetes affects bone at both the macrostructural and microstructural levels, leading to a higher risk of fracture that cannot be explained by changes in BMD alone.65

Our study revealed a significant reduction in fracture resistance in diabetic bone models compared to non-diabetic controls. This finding aligns with that of Farr and Khosla, who attribute the decreased mechanical properties to alterations in microarchitecture and material properties, especially higher cortical porosity in the cortical compartments of the distal radius and tibia in patients with T2D.66 Additionally, we found that the accumulation of AGEs significantly increases post-yield strain, consistent with previous studies. Fessel et al. highlighted that AGEs, by modifying collagen fibril interactions and reducing molecular sliding, can paradoxically increase post-yield strain.67 Conversely, Willett et al. demonstrated that AGE accumulation can lead to a decreased post-yield strain in ribated bovine metatarsi samples.68 This reduction in mineralization, coupled with an increase in hydration, could ostensibly increase the ductility of the bone matrix, enhancing its ability to deform post-yield. This complex interplay between decreased mineralization and increased hydration induced by AGEs suggests a nuanced mechanism through which diabetes could exacerbate cortical bone fragility, potentially leading to an elevated risk of fractures.

Collagen and mineral alterations in diabetic cortical bone

Combined with previous SEM experiments for basic bone research, our investigation using SEM images has identified two critical aspects of diabetic bone alterations: disordered mineral deposition and disrupted collagen fibril organization. In the context of diabetes-induced changes in bone microarchitecture, our observation about disordered accumulation of collagen and minerals along the longitudinal sections of diabetic cortical bone highlights the significant impact of diabetes on bone integrity. At the nanoscale dimension, mineral crystals are typically parallel to the collagen long axis.69 However, a decreased prevalence of collagen termini over layered structures in cross-sections indicated an alteration in collagen fibrils in diabetic bone. Based on previous studies,46,70 we interpret the disappearance of collagen termini as indicative of a smoother surface. From a biomechanical perspective,60,69,71 the disappearance of collagen termini suggests decreased resistance of collagen to disruption. Normally, the organized arrangement of collagen fibrils and mineral deposition are crucial for maintaining bone strength and resilience. However, in diabetes, AGE accumulation disrupts these processes, leading to an altered microstructure and compromised bone integrity.

AGE formation and non-enzymatic crosslinking

AGE formation and subsequent non-enzymatic crosslinking within the collagen matrix were key biochemical alterations observed in diabetic bone.72 AGEs, formed through non-enzymatic reactions between sugars and proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids, lead to the development of covalent bonds between collagen fibrils. In our study, we utilized SHG microscopy to reveal higher collagen crosslinking density due to the accumulation of AGEs,73 consistent with the observed stiffness of the bone matrix observed in diabetes. The SHG findings provide a quantitative measure of the higher collagen crosslinking in diabetic bone, aligning with research by Avery and Bailey, which demonstrates the utility of SHG in detecting microstructural changes in collagen indicative of early bone disease before observable changes in BMD occur.74

Furthermore, AGE accumulation detrimentally affects bone quality by reducing collagen’s normal flexibility and tensile strength.65 This is corroborated by findings of Tang et al., who demonstrated that the presence of AGEs significantly reduces the post-yield strain of bone, indicating a lower capacity to absorb energy before failure.75 These alterations in the mechanical behavior of collagen underscore the critical influence of AGEs on the overall fragility of diabetic bone.

Through cellular experiments, we demonstrated that HG does not impair mineral production and differentiation of osteoblast. In our study, osteogenesis-related protein ALP, mineralized nodule formation, and AGE production of extracellular matrix were synchronously higher under HG. The ALP activity in the extracellular matrix of osteoblasts cultured under the glucose concentration of 4.5 g/L (25 mM) in the culture medium was consistent with the results at the glucose concentration of 10–25 mM.76,77,78,79 Additionally, the results for the 10 g/L (550 mM) glucose concentration group align with the study of Zhen et al., who observed that higher glucose concentration (more than 40 mM glucose) reduced mineralization.80 Moreover, beyond affecting collagen’s structural and mechanical properties, AGE crosslinking interferes with the bone remodeling process. The normal binding of integrins and other matrix proteins to collagen is hindered by AGEs, affecting osteoblast and osteoclast activity.81,82 However, radiographic evidence in these areas is insufficient. In our study, the ARS staining of the MC3T3 cells and the mitochondrial morphology in the TEM image of the cell sections showed that the differentiation of osteoblasts was not distinctly affected in the high-glucose environment. Although we sought to demonstrate how AGE crosslink altered collagen mineralization in osteoblast extracellular matrix by TEM imaging of cell sections, the imaging evidence at cellular level was not robust enough to match molecular observation. Future work focusing on the cellular level is necessary.

The impact of AGEs on collagen highlights a potential therapeutic target for improving bone quality in diabetic patients. Interventions aimed at reducing AGE formation or breaking existing AGE crosslinks could help restore intrafibrillar mineralization and, by extension, improve bone quality and reduce fracture risk. This approach is supported by findings from Odetti et al., who observed that interventions targeting AGEs could partially reverse the adverse effects on bone’s mechanical properties.83

Collagen biomineralization

As Willett et al. acknowledge, AGE crosslinking may not fully account for cortical bone fragility. We identified collagen biomineralization as another key process68 involved in the formation of bone mechanical properties, which is strongly affected by the high-glucose environment. Collagen biomineralization is a complex process,84 where macromolecules (nucleic acids,85 proteins,86 polysaccharide,87 and polymers88), small molecules (citrate89), and charge distribution87 of collagen fibrils influence the effective mineralization (i.e., intrafibrillar mineralization) of collagen. Bone strength is predominantly supported by mineralized collagen with an ordered organization.53 Normal mineralization involves the entry of ACP into the collagen structure, leading to crystalline mineral formation.90 Previously, it was thought that mechanical properties were related to the amount and quality of mineralization, with “quality” being understood as the ratio of organic to inorganic materials.91 However, how HG affects interfibrillar and extrafibrillar mineralization of collagen, leading to macroscopic mechanical alterations, remains unknown.92 In our study, we explored the status of intra- and extrafibrillar mineralization in cortical bone and found that in vitro, AGE accumulation in a high-glucose environment alters this sequence, causing lower intrafibrillar mineral deposition and subsequently diminished mechanical properties of diabetic bone.

Therapeutic and potential side effects of guanidines

The pathological impact of diabetes on bone includes altered bone remodeling, reduced bone formation,93 and higher fracture risk, largely mediated by impaired bone microstructure. By inhibiting AGE formation, the structural integrity of collagen within the bone matrix is preserved, and the functional capacity of osteoblasts is improved.28,33,94,95 Delving into the molecular intricacies, our study observed that guanidines enhance the interfibrillar mineralization of collagen (Figure 4). These drugs also safeguarded the bone’s resistance to bending in high-glucose conditions (Figures 5E–5G). Furthermore, our study found that MET provides additional benefits over AG in enhancing the extracellular matrix’s ALP expression and the formation of calcium nodules in osteoblasts, as shown in Figure S11. This phenomenon may be attributed to protective effects of MET against diabetes-induced oxidative damage.95 Overall, the data suggest that AG has a more significant impact on the biomechanical properties of diabetic bone than MET, providing a potential therapeutic benefit in bone fragility associated with diabetes. MET also appears to have a positive effect, but the magnitude of improvement is less compared to AG.

The application of guanidines like AG and MET in treating DBD may raise questions about their safety profile. AG, while effective in reducing AGE formation,96 can potentially affect nitric oxide levels97 and has been linked with renal concerns over long-term use.98,99 Conversely, some other studies have reported AG can prevent oxidative stress to protect from renal ischemia and reperfusion injury.100 MET is generally well tolerated but can cause gastrointestinal issues95 and, rarely, lactic acidosis,101 particularly in those with kidney problems.102 It is necessary to closely monitor and evaluate the risk-benefit ratios in clinical applications.

All in all, our study reveals the paradoxical nature of diabetic bone, characterized by higher BMD yet compromised bone quality. This finding challenges the conventional reliance on BMD as a single indicator of bone health in diabetic patients, emphasizing the need for more comprehensive diagnostic approaches.

Limitations of the study

While this study offers critical insights into the role of AGEs in collagen mineralization and demonstrates the potential therapeutic effects of guanidine, there are some limitations that need to be considered.

One limitation is the complexity of biomineralization; our study focuses solely on glucose concentration and utilizes a diabetic mouse model, which may not fully capture the complexity and heterogeneity of diabetes as it manifests in different types or stages of the disease. Moreover, the mouse models primarily reflect T2D pathophysiology. Type 1 diabetes often occurs in adolescents and involves factors such as absolute insulin deficiency,103 insulin-like growth factor-1 deficiency, hyperglycemia, bone calcium loss caused by osmotic diuresis, and autoimmune and inflammatory damage that can easily lead to lower osteogenic function and bone strength and may affect the acquisition of peak bone mass.104 So, whether our findings can be extrapolated to type 1 diabetes, a disease with complex pathology, remains to be determined.

Another limitation is the extrapolation of these findings to human patients. Mouse models serve as an invaluable tool for understanding disease mechanisms and testing interventions; however, differences in bone structure, metabolism, and healing processes between mice and humans mean that direct translation of the results can be challenging. Furthermore, the 2-month post-fracture healing period examined in this study represents an early stage in the bone healing process. Additional studies assessing long-term outcomes are needed to fully understand the clinical implications of our findings.

In light of these limitations, future research should focus on validating these results across various types of diabetes and through longitudinal studies to assess the durability of the therapeutic effects observed. Additionally, further studies involving larger animal models that more closely mimic human bone, or clinical trials in diabetic patients, will be essential to establish the translational potential of these findings. Investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed improvements in bone quality and fracture resistance also provides deeper insights into therapeutic targets for enhancing bone health in diabetic individuals.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-Rabbit AGEs | Abcam | RRID: AB_447638 |

| Recombinant Anti-Collagen I antibody (Mouse mAb) | Servicebio | RRID: AB_3291602 |

| Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (HRP Conjugated) | Abcam | RRID: AB_955447 |

| Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 594) | Abcam | RRID: AB_2734147 |

| Goat Anti-Rat IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) | Abcam | RRID: AB_2338052 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Murine bone samples | Mice in this study | N/A |

| Human bone samples | Patient donators in this study | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| 4% paraformaldehyde buffer | Servicebio | G1101 |

| EDTA decalcifying Fluid (pH = 8.0) | Servicebio | G1105 |

| Environmental protection types dewaxing transparent liquid | Servicebio | G1128 |

| resinene | Servicebio | WG10004160 |

| Alizarin Red S solution | Solarbio | G1450 |

| Phosphate buffer solution | OriCell | ALIR-10001 |

| Fetal bovine serum | Gibco | 10099141C |

| Penicillin-streptomycin | Gibco | 5070063 |

| Streptozotocin | Aladdin | S110910 |

| Sodium chloride | Aladdin | S433749 |

| TRIS hydrochloride | Aladdin | T431530 |

| Polyaspartic acid | Merck | MFCD00166658 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Human Fibrin Sealant Kit | RAAS | S20030070 |

| Mouse osteogenic differentiation medium | Cyagen | MUXMX-90021 |

| H&E staining kit | Servicebio | G1005 |

| Masson kit | Servicebio | G1006 |

| DAB chromogenic kit | Servicebio | G1212 |

| BCIP/NBT Alkaline Phosphatase Color Development Kit | Beyotime | C3206 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Microsoft Office | Microsoft | https://www.microsoft.com/zh-cn/microsoft-365/microsoft-office |

| SPSS statistics 26.0 | IBM | https://www.ibm.com/cn-zh/products/spss-statistics |

| GraphPad Prism 9.0 | GraphPad | http://www.graphpad-prism.cn/ |

| Adobe Photoshop 2021 | Adobe | https://www.adobe.com/cn/products/photoshop.html |

| Adobe Illustrator 2023 | Adobe | https://www.adobe.com/cn/products/illustrator.html |

| FIJI | ImageJ | https://imagej.net/software/fiji/ |

| 3D-suite-software (including Skyscan, NRcon, Dataviewer, CTan, CTvox) | Bruker | https://www.bruker.com/en/products-and-solutions/preclinical-imaging/micro-ct/3d-suite-software.html |

| Origin 2021 | Origin lab | https://www.originlab.com/demodownload.aspx |

| Imaris 10.1. | Imaris | https://imaris.oxinst.cn/newrelease |

Resource availability

Lead contact

For detailed information and requests pertaining to resources and reagents, please reach out to the lead contact, Jiacan Su (drsujiacan@163.com), who will address and fulfill such requests.

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and subject details

Ethics statement

Ethical clearance for studies involving human or animal subjects was granted by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai University (Approval Numbers: ECSHU 2021–146 and ECSHU 2023–078). The design, execution, reporting, and dissemination of this research did not involve patient or public participation. Consent forms, approved by the local ethics board, were signed by all participating patient volunteers.

Origin of human cortical bone specimens

Human cortical bone specimens were obtained from the femoral neck during hip replacement surgeries. The samples were sourced solely from the cortical region of the femoral neck, without specific size restrictions.

The inclusion criteria for participants were: (a) adult females undergoing hip replacement surgery due to degenerative joint disease or trauma; (b) age between 65 and 75 years; (c) for the diabetic subgroup, individuals diagnosed with diabetes through an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and with a documented history of the disease for more than five years105—this duration is significant as previous research indicates that advanced glycation end products (AGEs) can accumulate significantly under managed conditions after five years of disease progression; (d) for the non-diabetic control group, individuals without diabetes or any other systemic disease that could influence bone metabolism, such as severe systemic infections, during the perioperative period. All participants provided written informed consent prior to the surgery.

Mouse models

T2D Mice: The DB mice, characterized by a mutation in the leptin receptor, display hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and obesity, making them a relevant model for studying diabetes-induced bone complications.59,60 The DB mice and C57BL/6J mice were bought from the Cavens Biogle Model Animal Research Co. Ltd (China). All animals were bred and raised under pathogen-free conditions. In the SPF facility at Shanghai University, the mice were housed with a density of five per cage. The controlled environmental settings included a temperature range of 20°C–24°C, humidity levels between 40 and 50%, and a 12-h light-dark cycle. The mice, at the ages of 8 and 20 weeks, were utilized in subsequent experiments following their sacrifice.

STZ-Induced Diabetic Models: During the age period of 4–8 weeks, male C57BL/6 mice were subjected to a diet high in sugar and fat to promote insulin resistance. Following this period, a single dose of STZ (cat. 572201, Sigma-Aldrich, America) at 40 mg/kg was injected intraperitoneally after 4 to 8 weeks on the specified diet. The STZ was dissolved in a citrate buffer solution with a pH maintained between 4.2 and 4.5. Mice in the control group received a corresponding volume of the citrate buffer. Regular monitoring of blood glucose levels was conducted, and those mice exhibiting persistent hyperglycemia (with blood glucose levels exceeding 12.5 mg/dL) were classified as diabetic and included in the study.

Cell culture

MC3T3-E1 Subclone 14 cells (MC3T3) (RRID:CVCL_5437, cat. M7-0201, OriCell, China) were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium, Alpha Modification (α-MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PS). All cells were maintained in a 37°C humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed once or twice weekly according to the growth rate. Cells were split with trypsin when the cells occupied over 80% of the culture flask.

Method details

Fracture induction and localized drug delivery in diabetic and non-diabetic mice

8-week-old male DB mice and STZ-induced diabetic mice, serving as 2 models for T2D alongside C57BL/6 mice, as non-diabetic controls, were subjected to a surgical procedure to induce fractures in their right femurs. This procedure was performed under anesthesia, administered with 1%, 50 mg/kg of pentobarbital sodium intraperitoneally. The right femur of each mouse was carefully exposed and then cut using a fretsaw, with the procedure being facilitated by the stabilization of the bone with an intramedullary nail, a technique adapted from previous studies.106 Following the surgery, mice were allowed to recover on a heated pad to maintain their body temperature, and appropriate pain management was provided to ensure their comfort and to minimize postoperative distress.

In an innovative approach to evaluate the therapeutic effects of guanidine-based drugs, specifically metformin and aminoguanidine, on the healing process of bone fractures in diabetic conditions, a Human Fibrin Sealant Kit was utilized. This involved the encapsulation of each drug in a fibrin gel, prepared by dissolving the prescribed drug doses in a fibrinogen solution, then activating the mixture with a thrombin component, as provided in the kit. The resulting medicated fibrin gel was then carefully injected at the fracture site of each mouse using a fine needle, ensuring the entire fractured area being adequately covered. This localized drug delivery system aimed to provide a sustained release of the therapeutic agents, potentially enhancing the bone healing process in a controlled and targeted manner.

The progression of fracture healing was meticulously monitored and assessed two months post-surgery through advanced imaging techniques such μCT and detailed histological examinations. These methods allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of the bone repair process, encompassing both qualitative and quantitative analyses to determine the efficacy of the guanidine-based drug treatments in facilitating bone healing in diabetic and non-diabetic mouse models.

Oral gavage administration in mice

The administration of drugs commenced when the mice were 8 weeks old and continued until they reached 20 weeks of age, aiming to evaluate the long-term impact of these medications on the progression of diabetes. The mice were randomly assigned to one of three groups: the metformin treatment group, the aminoguanidine treatment group, and the control group (which received an equivalent volume of saline). Throughout the experiment, all mice had ad libitum access to food and water. The dosages for MET and AG were 45 and 80 mg/kg/d respectively, determined based on a review of the literature and preliminary experimental outcomes to ensure both efficacy and safety.95,107 The administration was conducted via oral gavage once daily, continuously, until the conclusion of the experiment.

The oral gavage procedure was carried out by trained technicians under aseptic conditions using a gavage needle with a diameter of 45 mm to ensure direct delivery of the medication to the stomach, minimize stress responses, and enhance the precision of drug administration. Throughout the duration of the experiment, closely monitoring of the mice’s weight, food intake, and diabetes-related physiological parameters were maintained to evaluate the therapeutic and safety profiles of the guanidine-based medications.

μCT analysis

Upon surgical extraction, the right femurs of the mice were immediately submerged in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to preserve tissue integrity, followed by detailed μCT scanning using a micro-focus X-ray source coupled with a high-resolution detector (SkyScan 1076, Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). To ensure comprehensive analysis, each femur was scanned in its entirety, capturing high-resolution images at 12 μm resolution. The scanning process involved rotating the samples 180° to obtain multiple projections, facilitating a thorough examination of the bone’s internal structure. Subsequently, the acquired 2D X-ray images were reconstructed into high-resolution 3D images of the bone by NRcon software (Bruker MicroCT, Kontich, Belgium) and Dataviewer software (Bruker MicroCT, Kontich, Belgium), employing a voxel-based approach to represent the internal structure by stacking 2D slices.

For the detailed assessment of bone architecture, including both cortical and trabecular bone regions of cross-section view, multi-level Otsu thresholding was applied to segment bone voxels based on gray intensity levels, with thresholds set at 60 to 255 for trabecular bone and 120 to 255 for cortical bone.

The region of interest (ROI) for whole bone analysis was entire length of the femur, excluding joint region. Analyses of it included bone mineral density (BMD), bone volume over tissue volume (BV/TV).

The ROI for cortical bone analysis was a 5 mm segment centered at the midpoint located equidistantly between the proximal and distal ends of the femur. Analyses of cortical bone included tissue mineral density (TMD), total porosity (percent) (Po (tot)) and cortical thickness (Ct.Th).

Analyses of trabecular bone were conducted on the distal femoral metaphysis, starting 0.5 mm proximal to the growth plate and extending 4 mm proximally. The ROI was selected to include only trabecular bone, excluding the cortical shell. Analyses of trabecular architecture, including BMD, trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) and trabecular number (Tb.N).

The ROI for callus analysis was entire length of the callus. Analyses of it included bone BV/TV and structure model index (SMI).

All data analysis was conducted using the dedicated CTAn software (Bruker MicroCT, Kontich, Belgium) on cross-section, allowing for precise quantification and analysis of the reconstructed 3D bone images. And all images were rebuilt by CTvox software (Bruker MicroCT, Kontich, Belgium).

Mechanical testing

Three-point bending test

Referring to the previous study,108 the femurs of mice were dissected and obtained in Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS) in the −20°C refrigerator. In the three-point bending test, the left femurs were placed on two supporting pins a set distance (S) of 7.4 mm apart. A load was applied at the center of the sample in a speed of 0.02 mm/s and was sense by the electrodynamic test systems (MTS, Acumen 3, Germany). The test was terminated when the specimen was broken.

Data analysis

The test involves calculations for various parameters including yield load, ultimate load, fracture load, elastic modulus (E), post-yield deflection and work to fracture. These calculations take into account parameters like Yield load (F) on femurs, deflection of the yield point (f), inner width (d), outer width (D), inner narrow diameter (L), outer narrow diameter (L) of the femurs, support span (S) (Figure S3A).

Firstly, moment of inertia (I) was calculated by the formula109:

Then, elastic modulus (E) was calculated by the formula110:

Additionally, the yield load, ultimate load and fracture load were read from load-deflection curve. The post-yield deflection was calculated as the fracture strain minus yield strain to measure the extent of deformation the bone could endure following the yield point without fracturing. The work to fracture was computed, using Origin 2021, as the area under the load-deflection curve, which was then divided by the cross-sectional area at the fracture to obtain the material’s energy absorption density.

Torsion testing of post-fracture healing

To assess the biomechanical integrity of mouse femurs following fracture repair, torsion testing was conducted 21 days post-fracture. This timeline was chosen to evaluate the mechanical properties of healed bones. Femurs were collected immediately after μCT analysis and prepared for torsion testing.

Each femur was securely fixed into 5/16-inch diameter round brass tubes using a low-viscosity veterinary bone cement (BioMedtrix, Whippany, NJ, USA). To standardize the potting process and ensure consistent exposure and alignment of the femur’s middle third. Following potting, the assembly containing the femur was submerged in DPBS with calcium and magnesium for 45 min. This step allowed the bone cement to harden fully and prevented evaporative loss from the sample.

Biomechanical torsion testing was performed using a Mark-10 Advanced Torsion Testing System (Model TSTMH-DC) equipped with a 0.003 Nmm torsion sensor (CTT1202, MTS, CN). The torsion testing was conducted at a constant rate of 1° per second. The parameters measured during the test included maximum torsion to failure and the degree of twist at the point of failure. These measurements were derived from the resultant torque-twist curves generated during the testing refer to previous studies.111,112

Cell treatment and analysis

Cell culture and osteogenic inducution

MC3T3-E1 subclone 14 (MC3T3) cell, obtained from OriCell, was cultured in osteogenic differentiation medium. The cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Passage 5 to 8 cells were used for all experiments.

Cell treatment with AG and MET

To assess the impact of these drugs on osteogenic differentiation and mineralization MC3T3 cells were treated with AG and MET during the osteogenic induction process. Both AG and MET were added to osteogenic differentiation medium at a concentration of 100 μmol/L based on previous studies28,31,107 that identified this concentration as effective in promoting osteoblast activity without compromising cell viability. Throughout the experimental period, the culture medium, along with the drugs, was refreshed every 3 days to maintain optimal conditions for cell growth and differentiation.

ALP (alkaline phosphatase) and alizarin red S (ARS) staining

Evaluation of osteoblastic differentiation and functionality was conducted through the quantification of ALP activity and ARS-stained calcium deposits. MC3T3 cells, at a seeding density of 1 × 105 cells per well, were cultured in 12-well plates until they attained 95% confluence. Post a three-week culture period, the cells were cleansed with 1xPBS and subsequently fixed using 4% PFA. Staining for ALP and ARS was performed using the BCIP/NBT Alkaline Phosphatase Color Development Kit and ARS solution, respectively, following the guidelines provided by the manufacturers. Imaging was done with a Cytation 5 imaging reader (BioTek, AMERICA), and image analysis was carried out using FIJI software.

Cell culture medium and lysate collection for AGEs detection

At the end of the 3-week osteogenic induction period, the culture medium from each well was carefully aspirated, ensuring minimal disturbance to the cell layer. This medium was then transferred to centrifuge tubes and stored at −80°C for later analysis. Concurrently, cells were washed with 1 x PBS and lysed using radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer. To ensure complete cell lysis and the release of intracellular contents, the plates were gently agitated on a rocker for 15 min at 4°C. The lysates were then collected and centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 10 min to pellet cellular debris. The supernatant, containing the soluble cell lysate, was transferred to a new tube and stored alongside the culture medium at −80°C until ELISA analysis.

The concentration of AGEs in both the collected culture medium and cell lysates was determined using an AGE-specific ELISA kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol. This kit is designed to selectively bind to AGE modifications, providing a sensitive and quantitative measure of AGE levels. Standards and samples were added to the ELISA plate wells coated with an antibody specific to AGEs. After incubation and subsequent washing steps to remove unbound substances, a secondary antibody conjugated to a detection enzyme was added. Following a final incubation and wash, the substrate solution was added to each well, producing a color change that correlates with the concentration of AGEs present in the samples. The optical density (OD) of each well was measured using a microplate reader set to the appropriate wavelength, as specified by the ELISA kit instructions. AGE concentrations in the samples were calculated by comparing their OD values to a standard curve generated from known AGE concentrations.

Preparation of cell samples for transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

At the end of the 3-week osteogenic induction period, cells were harvested using a single-stroke action with a cell scraper to minimize damage. They were centrifuged at 1,500 to 3,000 x g for 5-10 min to form a pellet. For abundant samples, the pellet was gently divided into smaller clumps with a fine needle, and the supernatant was discarded. Cells were then fixed by slowly adding precooled (4°C) fixative solution along the tube side and stored at 4°C. For TEM preparation, cells underwent postfixation with 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydration in graded ethanol series, and embedding in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (about 70 nm) were cut, placed on copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined under a TEM to assess cellular ultrastructure. This method ensures the preservation of cellular structures for detailed analysis.

In vitro collagen molecule experiments

COL1 sample preparation

Collagen was extracted from the tails of male 8-week-old DB mice, STZ-induced diabetic mice, and C57BL/6 mice. For each mouse model, tails from five individuals were processed to ensure statistical relevance. Mouse tails were washed and immersed in 75% ethanol for 24 h. Then, tail collagen was extracted and placed in Tris-HCl (4.5 mM NaCl/6 g Tris, pH 7.5) at 4°C for 24 h. The tail collagen was weighed, and then dissolved in 0.1% acetic acid solution (1 g - 100 mL) at 4°C for at least one week with intermittent shaking. The collagen solution was filtered through a 300-mesh filter, resulting in crude extract. To each 600 mL of crude extract, 100 mL of 0.14 M NaOH was added, followed by centrifugation at 8000 revolutions per minute (RPM) for 5 min and removal of the supernatant. The precipitate was dissolved in 0.1 M acetic acid solution.

Collagen assembly and AGEs crosslink formation

First, the assembly solution was configured such that 0.1877 g of glycine and 0.7455g of KCl were dissolved in 50mL of aqueous solution and adjusted to pH = 9.0 with 0.2 M NaOH. For the formation of AGEs crosslinks, 16 μL of 3 mg/mL COL1 solution as added to 0.5 mL sterilized collagen assembly solution (pH 9.0), and co-cultured with glucose concentrations of 1.0 or 4.5 g/L reflecting normoglycemic and hyperglycemic conditions, respectively. In total, five samples for each glucose condition were prepared to ensure robust statistical analysis. Incubation occurred at 37°C for 3 days for AGEs crosslinks formation.113 Following incubation, the samples were then analyzed by AGEs-Elisa Kit (Cloud-clone Corp., Wuhan, CN) or liquid chromatography or loaded on a Ni mesh for TEM testing.

Collagen mineralization and TEM imaging

The in vitro collagen mineralization method was referred to pervious study.114 In brief, following fixed by 0.05% glutaraldehyde and rinsed by deionized water, the COL1-loaded Ni mesh was placed in a 37°C mineralization solution containing CaCl2, Na2HPO4, NaCl, polyaspartic acid (p-Asp), and NaN3, facilitating mineralization over periods of 3 or 7 days. The mineralized samples were then imaged by TEM for detailed structural analysis.

Collagen digestion and high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry testing

Enzymatic digestion of COL1 samples was performed using GluC. Precisely, 20μg of COL1 was prepared in a solution of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) and incubated it at 65°C for 2 h before the addition of 1 μL GluC (maintaining an enzyme/substrate ratio of 1:20 w/w). Following a 16-h incubation at 37°C, the digested samples were conducted via a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) setup. Three replicates were done for each group. This LC-MS configuration included Thermo Fisher Scientific’s EASY-nLC 1000 ultra-high-pressure system connected to their Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer through a nano-electrospray ion source. Peptides were eluted using a 60-min gradient of buffer A (0.1% v/v formic acid) and buffer B (0.1% v/v formic acid, 80% v/v acetonitrile), employing Thermo Scientific’s Acclaim PepMapTM RSLC nano HPLC-columns (75 μm × 15 cm) at a 300 nL/min flow rate. MS data collection was executed with a Top10 data-dependent MS/MS scanning approach, setting the full scan MS spectra target at 3 × 106 ions and an AGC in the 400–1650 m/z range. Post-acquisition, data processing and analysis were carried out using Thermo Scientific’s xcalibur data visualization platform and Proteome Discover 2.5 in the USA. The identification of AGE binding sites on collagen peptides utilizes a geometric approach based on atomistic modeling. This method determines the proximity of lysine (LYS) and arginine (ARG) residues essential for the formation of glucosepane, the principal AGE crosslink. By analyzing the molecular dynamics trajectory of the collagen microfibril, LYS/ARG pairs within a 5 Å cutoff are identified as potential sites for AGE crosslink formation.26