Abstract

Background:

The consideration of neurons as coupled mechanical-electrophysiological systems is supported by a growing body of experimental evidence, including observations that cell membranes mechanically deform during the propagation of an action potential. However, the short-term (seconds to minutes) influence of membrane voltage on the mechanical properties of a neuron at the single-cell level remains unknown.

Materials and Methods:

Here, we use microscale dynamic mechanical analysis to demonstrate that changes in membrane potential induce changes in the mechanical properties of individual neurons. We simultaneously measured the membrane potential and mechanical properties of individual neurons through a multiphysics single-cell setup. Membrane voltage of a single neuron was measured through whole-cell patch clamp. The mechanical properties of the same neuron were measured through a nanoindenter, which applied a dynamic indentation to the neuron at different frequencies.

Results:

Neuronal storage and loss moduli were lower for positive voltages than negative voltages.

Conclusion:

The observed effects of membrane voltage on neuron mechanics could be due to piezoelectric or flexoelectric effects and altered ion distributions under the applied voltage. Such effects could change cell mechanics by changing the intermolecular interactions between ions and the various biomolecules within the membrane and cytoskeleton.

Keywords: mechanical-electrophysiological coupling, neuron, nanoindentation, patch clamp

Introduction

Changes in neuronal membrane voltage above a given depolarization threshold induce the generation and propagation of action potentials (APs). This electrical activity is directly related to the flow of ions across the membrane through the opening and closing of transmembrane ion channels. In addition to their electrophysiological function, ion channels regulate cell volume1 and provide mechanosensitive functions.2,3 For example, mechanical forces can trigger electrophysiological and biochemical responses in cells by directly affecting the activity of mechanosensitive ion channels.4

Conversely, the propagation of APs has also been shown to induce physical and structural changes at the cell scale such as membrane deformation and displacement, or nerve thickness variation.5–10 The action of ion channels also directly depends on the surrounding membrane structure.11 Together, these observations suggest a close relationship between neuronal electrophysiology and mechanics.12

Over the past decades, new techniques and methodologies have been developed to measure and quantify the submicroscopic mechanical properties of materials.13,14 One such technique is nanoindentation, which can perform quasi-static and/or dynamic loading measurements of the mechanical properties of a sample at the micro- or nanoscale.15 Using nanoindentation and other micro/nanoscale techniques, an increasing body of work has studied the relationship between a cell's mechanical properties and functionality,16 and demonstrated that the mechanical properties of cells are essential determinants of cellular behavior under normal and pathological conditions.3,17,18 However, relatively few studies account for coupling between the mechanical and electrical properties of cells.

While some recent work has proposed the development of novel experimental techniques that enable successful simultaneous measurements of the electrophysiology and mechanical properties of neurons,19,20 such measurements are still in their infancy. In particular, to the best of our knowledge, no study has measured the impact of membrane electrical potential on neuron mechanics at the single-cell level. To fill this gap in current knowledge, we measured how induced membrane potentials (mV) affect the short-term (seconds to minutes) mechanical properties of individual neurons by employing a recently developed multiphysics setup that simultaneously combines whole-cell patch clamp, nanoindentation, and imaging.20

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

F11 cells (embryonic rat dorsal root ganglion × mouse neuroblastoma [N18TG-2, passage 20–24] hybrids; ECCAC, UK)21 were seeded at 1 × 105 cells per dish on 50 mm glass bottom petri dishes (glass thickness 1.5 mm; Wilco Wells, Amsterdam, NL) in 2 mL differentiation media (DMEM, 1% fetal bovine serum, 2 μM retinoic acid, 10 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 0.5% insulin transferrin selenium, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 50 ng/mL nerve growth factor, 0.5 mM 8-bromoadenosine 3′–5′ cyclic monophosphate).

Cultures were maintained for 5–8 differentiation days in a humidified incubator (5% carbon dioxide at 37°C). Every other day, 1 mL of media (Gibco, USA) was replaced by prewarmed (37°C) differentiation media. After 5–8 days of differentiation, cells exhibited traits of mature neurons, such as spontaneous AP firing and neurite elongation.20 These differentiated cells are established models of sensory neurons,21–24 with mechanical properties comparable with other neuronal cell types.25

Dynamic mechanical analysis

The mechanical properties of a single cell were measured under compression using a nanoindenter (Chiaro, Optics 11, Amsterdam, NL). Probes (Optics11 Life) consisting of a spherical bead (radius of 8 ± 0.5 μm)26 attached to a cantilever (stiffness of 0.029–0.035 N/m) were used. Microscale dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) was performed to measure the viscoelastic behavior of F11 cells by quantifying the storage (E′) and loss (E″) moduli of the cell. E′ accounts for the energy stored elastically, which is recovered after the indentation.27–29

E″ accounts for the viscous energy, dissipated as heat, during the indentation.27–29 For each measurement, the selected cell was precompressed by 1 μm over a period of 5 s followed by a relaxation of 30 s. DMA was then performed by applying a sinusoidal compression with a displacement amplitude of 400 nm and a specific frequency between 0.5 and 10 Hz. DMA at several frequencies was performed. After measurement at a single frequency, the next measurement was not performed for ∼20 s, to allow for cell relaxation.20 E′ and E″ for each measurement frequency were calculated by the Piuma software by fitting the experimental force and indentation time signals.30

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch clamp was performed on a single cell using a Digidata 1550A digitiser acquisition system, pCLAMP 10 data acquisition software, and a Multiclamp 700B MicroElectrode amplifier (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). The intracellular solution contained 140 mM KCl, 5 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP, and 1 mM EGTA with pH adjusted to 7.3 by addition of KOH and osmolarity adjusted to 300 mOsm/L by glucose addition. The extracellular solution contained 130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 80 10 mM HEPES, and was adjusted to 7.4 pH by NaOH and 310 mOsm/L by glucose addition.

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Patch clamp recording pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (BF100-78-10; Sutter Instruments) by a micropipette puller (Model P-1000; Sutter Instruments), to a resistance of 3–5 MΩ. Pulling parameters were based on previously published work.31 After a Giga-seal was formed between the pipette and a single cell, suction was applied to rupture the membrane patch and form a whole-cell patch configuration.

Assessment of electrophysiological-mechanical coupling

Simultaneous measurements of the electrophysiology and mechanical properties of a single F11 cell were performed using the multiphysics setup designed and described by Tamayo-Elizalde et al.20 First, the cell was clamped with the patch clamp recording pipette. Next, the cell was indented with the nanoindenter tip, and DMA was performed. The resulting measurement configuration is shown in Figures 1A and 1B. A specific membrane potential was induced and maintained for the duration of the DMA test. Membrane potential was tracked throughout the experiment to ensure that the quality of the clamp was maintained. If the clamp was lost or damaged, the data were discarded.

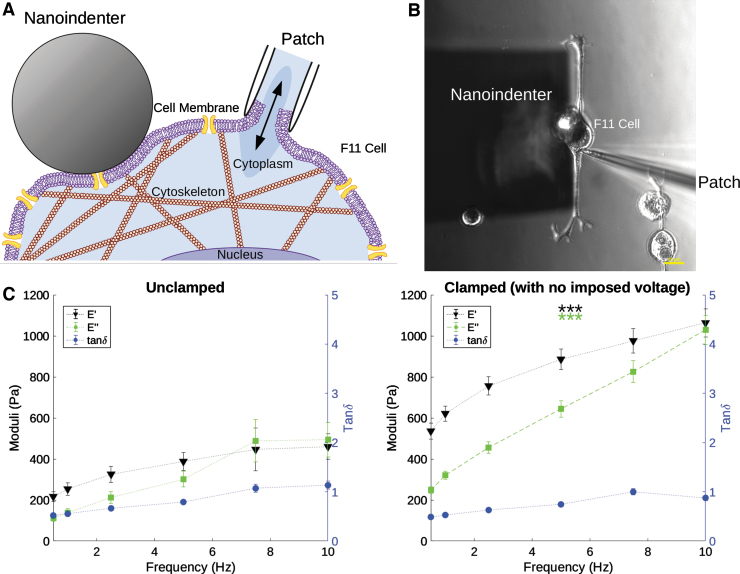

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation (A) and microscope image (B) of the simultaneous measurement of a single neuron's mechanical properties (through a nanoindenter) and electrophysiology (through whole-cell patch clamp); scale bar: 20 μm. (C) Storage and loss moduli (E′ and E″, respectively) and tanδ measurements of unclamped and clamped cells (no voltage was imposed by the clamp). E′ ± SE (Pa) is shown in black, E″ ± SE (Pa) in green, and tanδ ± SE in blue. Statistical analyses were performed between unclamped and clamped measurements at each frequency. Both E′ and E″ were significantly different between unclamped and clamped cells at each frequency, ***p < 0.001. SE, standard error.

A minimum of four cells was measured at each applied potential to account for variability in the results due to factors such as cell size, cell heterogeneity, and spatial position of the clamp and nanoindenter on the cell surface. Measurements were conducted at potentials of −100 mV (n = 4), −50 mV (n = 16), −40 mV (n = 19), 0 mV (n = 18), 10 mV (n = 15), 50 mV (n = 14), patch without imposed voltage (n = 7), and no patch (n = 12).

Only mature neurons, with neurites extending from the soma, were measured. Cells with a round soma, ∼20 μm in diameter, were selected, so that both the nanoindenter and patch clamp could be applied to the cell without directly touching each other. To minimize effects from neighboring cells, measurements were only performed on cells whose somas were not in direct contact with those of other neurons. For each nanoindenter measurement, cells were measured at 1 Hz during and after the DMA frequency sweep. If E′ and E″ differed between these two measurements, it was assumed that the cell had been damaged during the measurement, and the data for the particular cell were not included in the final analysis.

Microscopy

An inverted microscope Nikon Eclipse Ti (Nikon Instruments Inc., USA) was used to acquire images of F11 cells. Images were captured with 10 × , 20 × , or 40 × objectives.

Statistical analysis

A Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test normality of the data. Differences between measurements were evaluated by performing a one-way analysis of variance test, followed by a Wilcoxon post hoc test to obtain multiple comparison p-values. Comparison p-values are mentioned in the figure captions.

Results and Discussion

A schematic of the multiphysics experimental setup for simultaneous recording of cell mechanics and cell electrophysiology is shown in Figure 1A. First, a single F11 cell was clamped. Next, the cell body was indented by 1 μm. This indentation depth was within the cell's linear viscoelastic regime.20 After the initial indentation, oscillatory strains with a 400 nm amplitude were applied at different frequencies (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 Hz) to perform microscale DMA to measure E′ and E″ of the cell in its resting state.

Finally, cell E′ and E″ were measured at different voltages (−100, −50, −40, 0, 10, and 50 mV) imposed by the clamp. Since the thickness of the cell membrane is 3–10 nm,32 the applied 1 ± 0.4 μm indentations likely deformed intracellular components of the cell in addition to the plasma membrane. Therefore, the measured E′ and E″ represent properties arising from the combined membrane, cytoskeleton, and possibly nucleus of the neuron.

Patch clamp induces morphological and functional changes to a cell through pressure/suction on the cell membrane,33 which could potentially affect cell mechanics. To assess these effects, DMA was performed on individual neurons before (unclamped) and after clamping a particular cell. No electrical potential was applied during the clamped measurement, to measure only the effects of the clamp. As shown in Figure 1C, both E′ and E″ significantly (***p < 0.001) increased when cells were clamped. For all measured frequencies, the moduli of clamped cells were ∼2 × higher than those of the control (Table 1). Since both E′ and E″ increased in a similar manner, the ratio of the two, that is, the loss tangent tanδ = E″/E′, was not affected by clamping.

Table 1.

Storage Modulus (E′), Loss Modulus (E″), and Loss Tangent (tanδ = E″/E′) ± Standard Error at Each Dynamic Mechanical Analysis Frequency (f) for Neurons Without (Unclamped) and With Patch Clamp (No Imposed Voltage)

| f (Hz) | E′ (Pa) |

E″ (Pa) |

tanδ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unclamped | Clamped | Unclamped | Clamped | Unclamped | Clamped | |

| 0.5 | 216.95 ± 23.78 | 535.92 ± 38.26 | 111.73 ± 13.96 | 248.28 ± 16.17 | 0.52 ± 0.02 | 0.49 ± 0.03 |

| 1 | 253.72 ± 30.09 | 621.48 ± 36.97 | 138.78 ± 17.95 | 320.91 ± 18.86 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 0.53 ± 0.03 |

| 2.5 | 325.81 ± 39.07 | 756.30 ± 43.69 | 211.90 ± 27.40 | 455.57 ± 29.18 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.63 ± 0.03 |

| 5 | 388.18 ± 44.22 | 886.23 ± 50.49 | 301.72 ± 37.81 | 643.56 ± 40.47 | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 0.74 ± 0.04 |

| 7.5 | 446.50 ± 104.14 | 976.08 ± 60.27 | 488.75 ± 102.96 | 826.08 ± 54.20 | 1.07 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.07 |

| 10 | 460.25 ± 62.25 | 1063.40 ± 68.29 | 493.50 ± 83.28 | 1028.30 ± 70.43 | 1.13 ± 0.08 | 0.88 ± 0.06 |

Several possible mechanisms could explain the observed patch clamp effects on cell mechanics. First, deformation of the cell imposed by the patch (illustrated in Figure 1A), in addition to that imposed by DMA, could deform the cell more than the desired 1 ± 0.4 μm, potentially pushing measurements outside the linear viscoelastic regime of the cell. Alternatively, induced membrane curvature by the patch could alter the ion distribution on the membrane34–36 or the fluidity of the membrane,37,38 and thereby alter the mechanical properties of the membrane. In addition, since the cytoskeleton of the cell is anchored to the membrane, alterations to the membrane by the patch could potentially alter the cytoskeleton dynamics of the neuron, which could result in additional changes to cell mechanics.39

Next, we studied the influence of membrane potential on cell mechanics by imposing a voltage between −100 and 50 mV, and performing DMA at each potential. An example of this procedure is shown in Figure 2A. DMA measurements at a given potential were compared with control DMA measurements collected on the patched cell before any membrane potential was imposed. Figure 2B shows E′, E″, and tanδ at different imposed voltages as a function of frequency (Hz). The values of E′ and E″ changed in a similar manner, resulting in a constant tanδ. These results are reminiscent of those in Figure 1C.

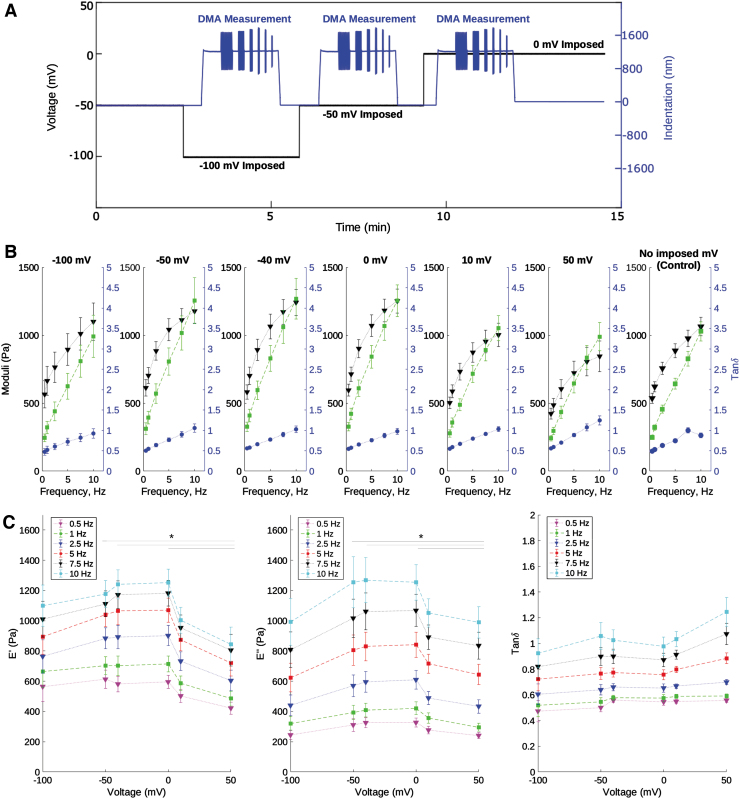

FIG. 2.

(A) Example multiphysics experiment procedure over a 3.33 min time interval. A voltage is imposed through patch clamp (black, −100, −50, and 0 mV), while DMA (blue) at different frequencies is performed through nanoindentation on the same cell (duration 2.5 min for 6 frequencies). Before time 0, control DMA measurements are performed on the patched cell without any imposed voltage. (B) Frequency-dependent variation of storage modulus, E′ ± SE (Pa) in black, loss modulus, E″ ± SE (Pa) in green, and the loss tangent, tanδ ± SE in blue of neuronal cells for multiple membrane potentials (mV). (C) E′ (Pa), E″ (Pa), and tanδ ± SE as a function of membrane potential (mV) for each DMA frequency, n = [4–19]. Statistical analysis was performed between each voltage at a given frequency, *p < 0.05. Measured tanδ were not significantly different. DMA, dynamic mechanical analysis.

Figure 2C shows E′, E″, and tanδ as a function of membrane potential (mV) for each DMA frequency. Both moduli remained constant at potentials between −100 and 0 mV. When positive voltage was imposed (at 10 and 50 mV), both E′ and E″ decreased. In particular, cell E′ and E″ were significantly lower at 50 mV (by a factor of ∼1.5; *p < 0.05) compared with the measurements at −50, −40, and 0 mV.

These observations are not due to the effects of the clamp, as shown in Figure 1C, since the control was the clamped cell before any voltage was applied. Therefore, the results of Figures 2B and C arise from the different imposed voltages. The trends we observed in E′ and E″ with frequency agree with those previously reported at both cell20 and tissue40 levels. As with Figure 1C, alterations in E′ and E″ between positive and negative voltages occurred in a similar manner, thereby resulting in a constant tanδ regardless of the membrane potential.

Several mechanisms could explain the observed alterations to energy storage and dissipation between positive and negative membrane potentials. For example, imposed voltages alter the activity of channels, which regulate cell volume and morphology,41 such as aquaporins42,43 and/or ion channels.4 Alterations to cell morphology through altered channel activity could potentially change the mechanical properties of the cell. In addition, it is already known that applied voltage alters the spatial distribution of lipids and proteins in the cell membrane, and thereby alters membrane fluidity/state and mechanics.12,44

Alterations in the spatial distribution of membrane lipids could also alter lipid polarization, and hence the structure of the cell membrane.45,46 Lipid redistribution and membrane structure alterations occur at the microscale, and can alter the whole-cell morphology.19,47 These alterations to cell morphology could potentially result in altered cell mechanics. It is also reasonable to hypothesize that the imposed voltage affected multiple cellular components, rather than the cell membrane alone. For example, it is already known that alterations to the conformation of the cytoskeleton alter cytoskeletal properties and cell mechanics.39 The neuronal cytoskeleton consists mainly of actin and spectrin.48 Actin49 and spectrin50 are piezoelectric, meaning they undergo strain when a voltage is applied and vice versa.51

Therefore, cytoskeletal strains under the voltages imposed in our experiments51 could potentially alter cytoskeletal and thereby cellular mechanics. Similarly, the cell membrane is flexoelectric,44 and many components (especially proteins) of the membrane are piezoelectric or exhibit other forms of mechanoelectric coupling.44,52,53 Furthermore, the cytoskeleton is anchored to the cell membrane, and alterations to one component can alter the other.54,55

For example, cytoskeletal anchoring to the membrane alters ion channel distribution in the membrane and lipid fluidity.54,56 The membrane–cytoskeleton system as a whole determines cell shape and mechanics.57 Together, these observations suggest that changes in cell mechanics due to different imposed voltages may arise from alterations to the conformation of molecules in the cytoskeleton and membrane through the induced potential.

In addition, the cytoskeleton (and therefore the membrane) is connected to the cell nucleus.58,59 Again, DNA and other components of the nucleus are piezoelectric.52,53,60 Changes in the conformation of the nucleus could therefore potentially alter the conformation of the cytoskeleton,58,59 and thereby the conformation of the cell membrane, further altering the mechanical properties of the cell. Additional experiments, employing tools such as atomic force microscopy (AFM) and/or ion channel or cytoskeletal inhibitors, are needed to determine which of the changes proposed in this paragraph contribute most to our results.

Piezoelectric, flexoelectric, and other mechanoelectric behaviors in biological systems arise from the fact that most biomolecules (such as actin, spectrin, DNA, proteins, and lipid heads) are small and charged.28,53,61 Interactions between biomolecule charges and the surrounding water and ions play an important role in modulating the charge, conformation, and mechanical properties of the biomolecule.28,62 For example, interaction of membranes with ions alters the fluidity and mechanical properties of the membrane.36,63,64

Hydration of actin and spectrin plays an important role in the mechanical properties and conformation of actin/spectrin cytoskeletons.65 Ions also have the ability to modulate hydrogen bonds and/or alter covalent interactions (by facilitating reactions or sterically blocking sites where covalent bonds can form) that determine how energy is stored (giving rise to E′) and dissipated (giving rise to E″) by the components of a cell.62,66,67 The voltages imposed in these experiments likely alter the distribution (steady state) of ions inside and immediately outside the cell.68

Such altered ionic distributions could in turn alter intermolecular interactions,62 and thereby the mechanical properties of the membrane, proteins, cytoskeleton, and other cellular components. In addition, it is reasonable to hypothesize that sign reversal of the membrane potential (negative to positive) would alter ionic distribution more than changing voltage within either positive or negative ranges (e.g., from −100 to −50 mV), thereby explaining our observation that the largest change in E′ and E″ of the neuron occurred between positive and negative membrane potentials.

Future investigation into neuronal multiphysics should test the validity of the hypothesis that membrane potential affects cell mechanics by altering ion distributions, and consequentially interactions between biomolecules within the neuron. To this end, several different experiments can be performed. For the first experiment, if the ion hypothesis is true, altering extracellular salt concentration should have similar effects to imposed membrane potentials on cell electrophysiology and mechanics. Measurements using our multiphysics setup, with patch clamp measuring the cell's resting potential and nanoindentation performing microscale DMA, could be performed on cells in solutions of various salts and salt concentrations. The second batch of experiments should test the effects of membrane potential on cellular components.

For such studies, AFM cellular imaging techniques69,70 could be employed to image and measure the mechanical properties of cells and their intracellular components simultaneously. The effects of voltage on cell mechanics in such AFM experiments could be studied by applying voltage in the AFM,71 or by performing AFM on cells in solutions of different salts or salt concentrations. Similarly, AFM measurements of the mechanical properties of isolated membranes, actin, spectrin, and DNA in different ionic conditions or applied voltages could be performed.

In summary, the objective of this work was to gain insight into electromechanical coupling in neurons by investigating the short-term (seconds to minutes) influence of imposed voltage on neuron mechanics. We found that membrane potential altered neuron viscoelasticity. Similar observations to ours have been reported for cells without patch clamp.20,72 However, unlike previous studies, our study also demonstrated a decrease in E′ and E″ with positive membrane voltages. The observed effects of applied voltage on neuron mechanics could be due to altered intermolecular and ionic interactions (caused by the imposed voltage) within the cell membrane, cytoskeleton, and possibly cell nucleus.

Our observations could have implications for several neuronal processes. Alterations to neuron mechanical properties affect the neuron's ability to generate and propagate APs,12 and could explain the effects of a variety of stimuli on nervous system activity.12,73–75 Therefore, future work designed to test the ion hypothesis proposed here and elucidate the mechanisms behind mechanoelectric coupling in neurons could help explain a variety of phenomena, and increase our understanding of AP propagation in neurons. Such understanding would increase our ability to exploit mechanoelectric coupling in neurons for clinical applications such as ultrasound neuromodulation12 or the treatment of paralysis.76,77

Authors' Contributions

C.K., M.T.-E., and A.J. designed the research; C.K. performed data collection and analysis; C.A., C.K., and A.J. wrote the article; H.Y. supervised the experimental work; A.J. supervised the overall research.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

Data are available upon request to the corresponding authors.

Funding Information

The authors acknowledge funding from the EPSRC Healthcare Technologies Challenge Award EP/N020987/1.

References

- 1. Lang F, Shumilina E, Ritter M, et al. Ion channels and cell volume in regulation of cell proliferation and apoptotic cell death. Contrib Nephrol 2006;152:142–160. DOI: 10.1159/000096321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anishkin A, Loukin SH, Teng J, et al. Feeling the hidden mechanical forces in lipid bilayer is an original sense. PNAS 2014;111:7898–7905. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1313364111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bianchi F, Malboubi M, George JH, et al. Ion current and action potential alterations in peripheral neurons subject to uniaxial strain. J Neurosci Res 2019;300 97:744–751. DOI: 10.1002/jnr.24408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ranade SS, Syeda R, Patapoutian A. Mechanically activated ion channels. Neuron 2015;87:1162–1179. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen LB. Changes in neuron structure during action potential propagation and synaptic transmission. Physiol Rev 1973;53:373–418. DOI: 10.1152/physrev.1973.53.2.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heimburg T, Jackson AD. On soliton propagation in biomembranes and nerves. Natl Acad Sci 2005;102:9790–9795. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0503823102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim GH, Kosterin P, Obaid AL, et al. A mechanical spike accompanies the action potential in mammalian nerve terminals. Biophys J 2007;92:3122–3129. DOI: 10.1529/biophysj.106.103754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. El Hady A, Machta BB. Mechanical surface waves accompany action potential propagation. Nat Commun 2015;6:1–7. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gonzalez-Perez A, Mosgaard L, Budvytyte R, et al. Solitary electromechanical pulses in lobster neurons. Biophys Chem 2016;216:51–59. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpc.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ling T, Boyle KC, Zuckerman V, et al. High-speed interferometric imaging reveals dynamics of neuronal deformation during the action potential. PNAS 117;117:10278–10285. DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.11879334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Phillips R, Ursell T, Wiggins P, et al. Emerging roles for lipids in shaping membrane-protein function. Nat Insight 2009;459:379–385. DOI: 10.1038/nature08147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jerusalem A, Al-Rekabi Z, Chen H, et al. Electrophysiological-mechanical coupling in the neuronal membrane and its role in ultrasound neuromodulation and general anaesthesia. Acta Biomaterialia 2019;97:116–140. DOI: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leite FL, Mattoso LHC, Oliveira ON, et al. The atomic force spectroscopy as a tool to investigate surface forces: Basic principles and applications. In: Méndez-Vilas A, Díaz J, eds. Modern Research and Educational Topics in Microscopy. Badajoz, Spain: Formatex, 2007: 747–757. DOI: 10.1.1.571.8452 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buffinton CM, Tong KJ, Blaho RA, et al. Comparison of mechanical testing methods for biomaterials: Pipette aspiration, nanoindentation, and macroscale testing. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2015;51:367–379. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Qian L, Zhao H. Nanoindentation of soft biological materials. Micromachines 2018;9:654. DOI: 10.3390/mi9120654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bartolozzi A, Viti F, De Stefano S, et al. Development of label-free biophysical markers in osteogenic maturation. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2020;103:1–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2019.103581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lulevich V, Zink T, Chen H-Y, et al. Cell mechanics using atomic force microscopy-based single-cell compression. Langmuir 2006;350 22::8151–8155. DOI: 10.1021/la060561p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guz N, Dokukin M, Kalaparthi V, et al. If cell mechanics can be described by elastic modulus: Study of different models and probes used in indentation experiments. Biophys J 2014;107:564–575. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beyder A, Sachs F. Electromechanical coupling in the membranes of shaker-transfected HEK cells. PNAS 2009;106:6626–6631. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0808045106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tamayo-Elizalde M, Chen H, Malboubi M, et al. Action potential alterations induced by single f11 neuronal cell loading. Progr Biophys Mol Biol 2020;162:141–153. DOI: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2020.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Francel PC, Harris K, Smith M, et al. Neurochemical characteristics of a novel dorsal root ganglion x neuroblastoma hybrid cell line, f-11. J Neurochem 1987;48:1624–1631. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb05711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fan S, Shen K, Scheideler M, et al. F11 neuroblastoma DRG neuron hybrid cells express inhibitory μ- and δ-opioid receptors which increase voltage-dependent K+ currents upon activation. Brain Res 1992;590:329–333. DOI: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91116-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wieringa P, Tonazzini I, Micera S, et al. Nanotopography induced contact guidance of the f11 cell line during neuronal differentiation: A neuronal model cell line for tissue scaffold development. Nanotechnology 2012;23:275102. DOI: 10.1088/0957-4484/23/27/275102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Prucha J, Krusek J, Dittert I, et al. Acute exposure to high-induction electromagnetic field affects activity of model peripheral sensory neurons. J Cell Mol Med 2017;22:1355–1362. DOI: 10.1111/jcmm.13423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lu Y-B, Franze K, Seifert G, et al. Viscoelastic properties of individual glial cells and neurons in the CNS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:17759–17764. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0606150103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van Hoorn H, Kurniawan NA, Koenderink GH, et al. Local dynamic mechanical analysis for heterogeneous soft matter using ferrule-top indentation. Soft Matter 2016;12:3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Popov VL, Heß M, Willert E. Handbook of Contact Mechanics: Exact Solutions of Axisymmetric Contact Problems, 1st Edition. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2019. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-662-58709-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Doi M. Soft Matter Physics, 1st Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199652952.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Seifert J. In vivo dynamic AFM mapping of viscoelastic properties of the primary plant cell wall. Doctoral (PhD) Thesis. University of Oxford, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bartolini L, Iannuzzi D, Mattei G. Comparison of frequency and strain-rate domain mechanical characterization. Sci Rep 2018;8:13697. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-31737-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Malboubi M, Gu Y, Jiang K. Characterization of surface properties of glass micropipettes using SEM stereoscopic technique. Microelectr Eng 2011;88:2666–2670. DOI: 10.1016/j.mee.2011.02.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hine R. The Facts on File Dictionary of Biology (Facts On File Science Library). Facts On File Inc, 2005. DOI: 10.1093/acref/9780199204625.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hamill OP, McBride DW. Induced membrane hypo/hyper-mechanosentitivity: A limitation of patch-clamp recording. Annu Rev Physiol 1997;59:621–652. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Magarkar A, Jurkiewicz P, Allolio C, et al. Increased binding of calcium ions at positively curved phospholipid membranes. J Phys Chem Lett 2017;8:518–523. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b02818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tarun OB, Okur HI, Rangamani P, et al. Transient domains of ordered water induced by divalent ions lead to lipid membrane curvature fluctuations. Commun Chem 2020;3:17. DOI: 10.1038/s42004-020-0263-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Piantanida L, Bolt HL, Rozatian N, et al. Ions modulate stress-induced nanotexture in supported fluid lipid bilayers. Biophys J 2017;113:426–439. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.05.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lipowsky R. Remodelling of membrane compartments: Some consequences of membrane fluidity. Biol Chem 2014;395:253–274. DOI: 10.1515/hsz-2013-0244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yesylevskyy SO, Rivel T, Ramseyer C. The influence of curvature on the properties of the plasma membrane insights from atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. Sci Rep 2017;7:16078. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-16450-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roca-Cusachs P, Almendros I, Sunyer R, et al. Rheology of passive and adhesion-activated neutrophils probed by atomic force microscopy. Biophys J 2006;91:430 3508–3518. DOI: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Qian L, Sun Y, Tong Q, et al. Indentation response in porcine brain under electric fields. Soft Matter 2019;15:623. DOI: 10.1039/c8sm01272e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lang F. Mechanisms and significance of cell volume regulation. J Am Coll Nutr 2007;26:613S–623S. DOI: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hub JS, Aponte-Santamaría C, Grubmüller H, et al. Voltage-regulated water flux through aquaporin channels in silico. Biophys J 2010;99:L97–L99. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takata K, Matsuzaki T, Tajika Y. Aquaporins: Water channel proteins of the cell membrane. Progr Histochem Cytochem 2004;39:1–83. DOI: 10.1016/j.proghi.2004.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Deng Q, Liu L, Sharma P. Flexoelectricity in soft materials and biological membranes. J Mech Phys Solids 2014;62:209–227. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmps.2013.09.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. van IJzendoorn SC, Agnetti J, Gassama-Diagne A. Mechanisms behind the polarized distribution of lipids in epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomem 2020;1862:183145. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2019.183145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jareb M, Banker G. The polarized sorting of membrane proteins expressed in cultured hippocampal neurons using viral vectors. Neuron 1998;20:855–867. DOI: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80468-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mosbacher J, Langer M, Hörber J, et al. Voltage-dependent membrane displacements measured by atomic force microscopy. J Gen Physiol 1998;111:65–74. DOI: 10.1085/jgp.111.1.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu K, Zhong G, Zhuang X. Actin, spectrin, and associated proteins form a periodic cytoskeletal structure in axons. Science 2013;339:452–456. DOI: 10.1126/science.1232251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fukada E, Ueda H. Piezoelectric effect in muscle. Jpn J Appl Phys 1970;9::844–845. DOI: 10.1143/JJAP.9.844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ivanov I, Paarvanova B. Dielectric relaxations on erythrocyte membrane as revealed by spectrin denaturation. Bioelectrochemistry 2016;110:59–68. DOI: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2016.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. An R, Wipf DO, Minerick AR. Spatially variant red blood cell crenation in alternating current non-uniform fields. Biomicrofluidics 2014;8::021803. DOI: 10.1063/1.4867557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fukada E. History and recent progress in piezoelectric polymers. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2000;47::1277–1290. DOI: 10.1109/58.883516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Athenstaedt H. Pyroelectric and piezoelectric properties of vertebrates. Ann NY Acad Sci 1974;238:68–94. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb26780.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Machnicka B, Czogalla A, Hryniewicz-Jankowska A, et al. Spectrins: A structural platform for stabilization and activation of membrane channels, receptors and transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomem 2014;1838:620–634. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bezanilla M, Gladfelter AS, Kovar DR, et al. Cytoskeletal dynamics: A view from the membrane. J Cell Biol 2015;209:329–337. DOI: 10.1083/jcb.201502062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Susuki K, Rasband MN. Spectrin and ankyrin-based cytoskeletons at polarized domains in myelinated axons. Exp Biol Med 2008;233:394–400. DOI: 10.3181/0709-MR-243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stokke B, Mikkelsen A, Elgsaeter A. Spectrin, human erythrocyte shapes, and mechanochemical properties. Biophys J 1986;49:319–327. DOI: 10.1016/S0006-3495(86)83644-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mao X, Gavara N, Song G. Nuclear mechanics and stem cell differentiation. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2015;11:804–812. DOI: 10.1007/s12015-015-9610-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang N, Tytell JD, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction at a distance: Mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009;10:75–82. DOI: 10.1038/nrm2594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Duchesne J, Depireux J, Bertinchamps A, et al. Thermal and electrical properties of nucleic acids and proteins. Nature 1960;188:405–406. DOI: 10.1038/188405a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Piacenti A. Atomic force microscope-based methods for the nanomechanical characterisation of hydrogels and other viscoelastic polymeric materials for biomedical applications. Doctoral (PhD) Thesis, University of Oxford, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Israelachvili JN. Intermolecular and Surface Forces, 3rd Edition. Elsevier, Academic Press, 2011, OCLC: 2492. 72556. DOI: 10.1016/C2011-0-05119-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gawrisch K, Parsegian AV, Rand PR. Membrane hydration. In: Glaser R, Gingell D, eds. Biophysics of the Cell Surface, Vol. 5: Springer Series in Biophysics. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 1990: 61–73. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-74471-6_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Trewby W, Faraudo J, Voïtchovsky K. Long-lived ionic nano-domains can modulate the stiffness of soft interfaces. Nanoscale 2019;11:4376–4384. DOI: 10.1039/C8NR06339G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Moe SJ, Cembran A. Mechanical unfolding of spectrin repeats induces water-molecule ordering. Biophys J 2020;118:1076–1089. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Li X, Kolega J. Effects of direct current electric fields on cell migration and actin filament distribution in bovine vascular endothelial cells. J Vasc Res 2002;39:391–404. DOI: 10.1159/000064517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rosenblatt J, Devereux B, Wallace D. Injectable collagen as a pH sensitive hydrogel. Biomaterials 1994;15:985–995. DOI: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90079-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. García-Grajales JA, Rucabado G, García-Dopico A, et al. Neurite, a finite difference large scale parallel program for the simulation of electrical signal propagation in neurites under mechanical loading. PLoS One 2015;10:e0116532. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cartagena A, Raman A. Local viscoelastic properties of live cells investigated using dynamic and quasi-static atomic force microscopy methods. Biophys J 2014;106:1033–1043. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.12.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Raman A, Trigueros S, Cartagena A, et al. Mapping nanomechanical properties of live cells using multi-harmonic atomic force microscopy. Nat Nanotechnol 2011;6:809–814. DOI: 10.1038/nnano.2011.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Carney RP, Astier Y, Carney TM, et al. Electrical method to quantify nanoparticle interaction with lipid bilayers. ACS Nano 2013;7:932–942. DOI: 10.1021/nn3036304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhang Y, Abiraman K, Li H, et al. Modelling of the axon membrane skeleton structure and implications for its mechanical properties. PLoS Comput Biol 2017;13:e1005407. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lundbæk JA, Birn P, Hansen AJ, et al. Regulation of sodium channel function by bilayer elasticity. J Gen Physiol 2004;123:599–621. DOI: 10.1085/jgp.200308996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lundbæk JA, Birn P, Tape SE, et al. Capsaicin regulates voltage-dependent sodium channels by altering lipid bilayer elasticity. Mol Pharmacol 2005;68:680–689. DOI: 10.1124/mol.105.013573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Goldstein DB. The effect of drugs on membrane fluidity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1984;24:43–64. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.pa.24.040184.000355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ievins A, Moritz CT. Therapeutic stimulation for restoration of function after spinal cord injury. Physiology 2017;32:391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Moritz C. A giant step for spinal cord injury research. Nat Neurosci 2018;21:1647–1648. DOI: 10.1038/s41593-018-0264-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to the corresponding authors.