Abstract

Streams provide an array of habitat niches that may act as environmental filters for fish communities. The tropical island of Sulawesi in Indonesia is located in the Wallacea, a region isolated by marine barriers from the Asian and Australian faunas. Primary freshwater fishes are naturally absent in the Wallacea, including Sulawesi's numerous coastal streams. Diadromous species are in contrast species‐rich in the area. The knowledge available on stream fishes in the Wallacea is largely restricted to taxonomic work and studies targeting single species groups, whereas baseline data on fish ecology remain extremely scarce. Such data and a deeper understanding of stream fish ecology are, however, urgently required for purposes such as informed management. We assumed that the stream fish assemblages are dominated by recruitment from the sea and are structured by macro‐ and microhabitat diversity. To test this hypothesis, we quantified the occurrence of individual fishes by point abundance electrofishing at 33 streams across Sulawesi. The 4632 fishes obtained represent 58 species out of 24 families. The native fishes recorded are mainly amphidromous (34 species), euryhaline (five species), and catadromous (five species). Gobiiformes make up the vast majority of records, dominated by Oxudercidae (22 species) and Eleotridae (five species). Only two of the species recorded are endemic to Sulawesi, including a single species strictly confined to freshwaters. Ten species, making up 6% of the fishes caught, are not native to Sulawesi. The outlying mean index (OMI) and BIOENV analyses suggest that effects on the scale of macro‐ and microhabitat shape fish assemblage composition, ranging from pH, conductivity, and temperature to current velocity, substrate, canopy cover, and elevation. Habitat niche use of species along the first two OMI axes is complementary and fine‐scaled, covering a wide range of the available habitat space. Juvenile and adult conspecifics share similar habitat niches in most of the cases. Niche breadths overlap, but niche specialization is significant in most of the species. Non‐native fishes link into the assemblages at the margins of habitat space, with substantial niche overlaps to native species. The present findings show that the native fish communities in coastal streams of Sulawesi are largely composed of species depending on access to the sea, highlighting the importance of connectivity down to the estuaries and sea. The ichthyofauna shows a rich diversity in habitat use, and the availability of alternative habitats along the altitudinal gradient provides plausible filters for species establishment. Non‐native fishes are locally abundant, pose substantial potential for changing communities, but are still stocked intentionally. We stress the need for incorporating the need for connectivity and maintained habitat quality into management decisions, and a critical evaluation of stocking activities.

Keywords: community assembly, ecology, freshwater fishes, habitat use, point abundance electrofishing

1. INTRODUCTION

Stream ecosystems are characterized by habitat diversity and dynamics (Astorga et al., 2014; Lotze et al., 2006; Orth et al., 2006; Villéger et al., 2010; Zeni & Casatti, 2014), and their fish communities are affected by processes acting on very different scales. On continental to landscape level, biogeography defines the regional species pool that fuels community assembly (Jackson et al., 2001; Montaña et al., 2014), while gradients in habitat related to altitude and flow conditions, adaptations associated with resistance and feeding, affect the longitudinal structure of communities on basin level (Pease et al., 2012; Walsh et al., 2022). On the local scale, the complex mosaic of habitats supports various adaptations (Arrington et al., 2005). A habitat's ecological characteristics constitute a first environmental filter for settling species, potentially complemented by competitive interactions and predation (Borcard et al., 1992; Montaña et al., 2014; Peres‐Neto, 2004; Ricklefs, 2004; Sternberg & Kennard, 2014; Yeager et al., 2011).

Sulawesi is the largest island of the Wallacea, the transition zone between the continental Asian and Australian faunal regions (Doorenweerd et al., 2020; Myers et al., 2000; von Rintelen et al., 2012, 2014). Isolation and the complex geological history explain the natural absence of primary freshwater fishes (sensu Darlington Jr., 1957 – fishes with little salt tolerance, an ecological concept; Lévêque et al., 2007; Myers, 1949; see Berra, 2007 for discussion) from the tropical island (Kottelat et al., 1993). Sulawesi's freshwater biota are best known for the adaptive radiations endemic to the island's large and ancient lakes (Herder et al., 2006; Herder, Schliewen, et al., 2012; von Rintelen et al., 2007, 2014; von Rintelen & Glaubrecht, 2005), including flocks of freshwater fishes. The frequently steep mountain ridges of Sulawesi are, however, drained by numerous mostly short rivers and coastal streams (Figure 1), and the current knowledge about species diversity and ecology of stream fishes in the Wallacea remains surprisingly limited. The native fauna reported is composed of a systematically wide array of mainly amphidromous and euryhaline fishes, with species distributions ranging from local endemism to pacific areas (Hubert, Kadarusman, et al., 2015; Kottelat et al., 1993). It is far from being completely explored, however, and new species or records are reported regularly from various families, ranging from, for example, Gobiidae (Keith et al., 2021) and Oxudercidae (Nurjirana et al., 2022) to Adrianichthyidae (Gani et al., 2022) and Zenarchopteridae (Kraemer et al., 2019). Only a limited number of focal studies contributed data on the autecology of selected species (e.g., Muthiadin et al., 2020 on Sicyopterus, Lamba et al., 2023, on Oryzias), but molecular studies increasingly allow indirect inferences via analyses of population structure (Jamonneau et al., 2024).

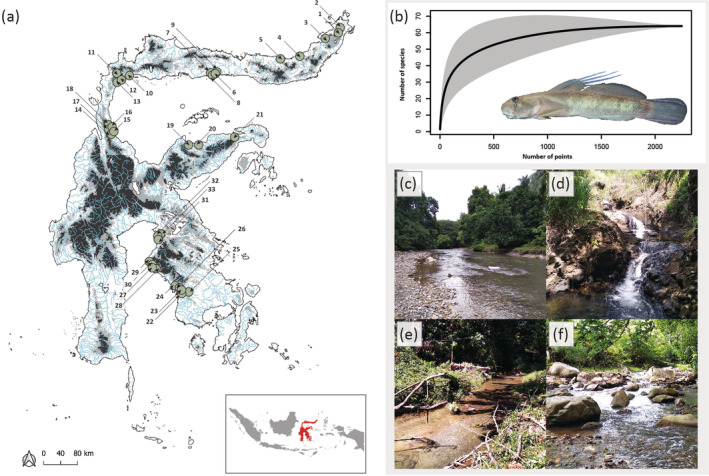

FIGURE 1.

Sulawesi (a) is located in the Wallacea (insert map, Sulawesi highlighted in red). The tropical island is characterized by steep mountain formations with numerous coastal drainages (blue). Species accumulation curve (b) based on point abundance sampling at 33 sites located in different drainages (numbered green circles in map (a)) shows clear saturation of species diversity along the 2246 points bearing fishes; insert picture shows a male Sicyopterus longifilis (photograph by T.K.), the most abundant species recorded. Habitat diversity covered ranges from broad and mostly open streams (c) (site 13) to narrow, swiftly flowing streams with small cascades (d) (site 4) and forest creeks dominated by gravel and sand (e) (site 24) to rocky pool‐and‐riffle formations (f) (site 14) (photographs by L.L.W.).

Hubert, Kadarusman, et al. (2015) compiled records of freshwater fish species for contributing to the Indonesian DNA barcode library and listed a total of 146 fish species from 31 families for Sulawesi. Miesen et al. (2016) compiled a taxonomic checklist of Sulawesi's inland fishes, summing up a total of 226 species, including 65 endemics, in majority species restricted to the isolated lakes. The discrepancy in total fish species recognized is due to the wider approach taken by Miesen et al. (2016), who included species recorded from the area that are known to enter streams or rivers, but were not actually confirmed for freshwaters in Sulawesi. The limited exploration of Sulawesi's riverine ichthyofauna is unfortunately accompanied by substantially increasing threats from habitat loss, pollution, and the invasion of non‐native fishes (see e.g., Herder, Schliewen, et al., 2012; Herder et al., 2022 for expansion and impact of exotic fish species in Sulawesi lakes). Tweedley et al. (2013) studied the composition and habitat of the freshwater ichthyofauna of two islands off southeast Sulawesi, Buton and Kabaena. Applying electrofishing at 63 sites, they found a total of 64 species, dominated by Oxudercidae, Gobiidae, Eleotridae, Zenarchopetridae, and Anguillidae. Geography, altitude, and substrate were revealed as the major factors shaping species distribution.

We hypothesized that the composition and structure of stream fish communities on the main island of Sulawesi match expectations from Buton and Kabaena: freshwater assemblages depend on connectivity with the sea, changing with altitude and macrohabitats. Understanding the basic ecology of Sulawesi stream fish communities appears highly relevant from different perspectives, including fundamental research, but also for enabling informed management in an area where hydropower infrastructure is becoming more and more relevant (e.g., Baumgartner & Wibowo, 2018). We further assumed that non‐native fishes spread across Sulawesi streams, potentially coming with threats for the native fauna as shown by the island's large lakes (Herder et al., 2022; Herder, Schliewen, et al., 2012). To test these hypotheses, we applied a sampling scheme based on point abundance electrofishing (Nelva et al., 1979), permitting the study of associations among fishes and habitats on the levels of micro‐ and macrohabitats. We investigated coastal stream fish communities at different areas and drainages across Sulawesi (Figure 1). Based on the data acquired, we analyzed the composition and patterns of habitat niche use in fish communities from the main island of Sulawesi.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Spatial sampling scheme

Sulawesi Island is a complex composite of volcanic and old continental fragments (de Bruyn et al., 2013; Hall, 2011; Lohman et al., 2011; Nugraha & Hall, 2018). We designed our sampling scheme to cover the habitat diversity of coastal streams across the island. Focus was concentrated on actual stream habitats that could be characterized as running waters of first to third order (Whitten et al., 2002) and excluded for logistic reasons the main beds of the comparatively few large rivers, as well as brackish environments. Sampling sites were selected along a transect course over 10 weeks in the dry season from May to July 2019, in the provinces of North Sulawesi, Gorontalo, Central, South, and South‐East Sulawesi (Figure 1; see Table S1 for details). For logistic reasons, the present study does not include all areas of Sulawesi, and does not include wet season data, which would require substantial additional efforts (road access in remote areas, sampling efforts at higher water levels, etc.). A single sampling site was selected for each drainage system, with each site being sampled only once. We aimed to cover different altitudes and macrohabitats. Candidate streams were selected based on topographic maps and inspection of satellite images (Google Earth, Google Maps, Apple Maps). Physical access by road was a core criterion to enable efficient data collection. On arrival, a visual assessment of the stream was conducted to evaluate potential safety concerns, accessible entry points, and suitability for wading. We accepted moderate disturbance at single sites, such as sites used by local people for bathing, but excluded waters heavily affected by human activities, such as severe modifications of the banks or obvious, massive pollution. We likewise excluded sites that did not yield native fish species after an initial inspection of ca. 5 min. Sites in drainages that were blocked downstream by dams, preventing fish migration, were excluded from the present analyses. Following Tweedley et al. (2013), freshwater was considered with an upper limit in conductivity of 600 μS cm−1.

2.2. Ethics statement

All experiments, including fish handling and processing, were conducted in accordance with the research ethics guidelines for the care and use of animals of the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) (No. 19/ 2019 – Tentang Klirens Etik Penelitian). Selected specimens were collected using an electrofishing unit optimized for small fishes in DC mode (best practices for sampling success and fish welfare; Pottier et al., 2020), representative individuals were properly anesthetized and killed in a saturated solution of chlorobutanol. Specimens used in this study are not listed as threatened or endangered by the IUCN Red List or Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

2.3. Point abundance electrofishing and habitat characterization

Electrofishing is considered the most common method for sampling fishes in rivers (Le Pichon et al., 2017). We used point abundance electrofishing (Copp & Penaz, 1988) to record fishes in their individual habitat within the stream environment. Fieldwork was conducted during daylight between 09.00 and 17.00 h (local time). The data and specimen collection strategy largely followed Herder and Freyhof (2006). A portable electrofishing unit (Bretschneider EFGI 650) optimized for small fishes by using an anode ring of 15 cm diameter (Copp, 1989) was activated in DC mode (best practices for sampling success and fish welfare; Pottier et al., 2020) at points selected in a random‐stratified manner (Copp & Penaz, 1988). To randomly represent all habitat types, the first operator handling the electrofishing unit followed a transverse transect wading upstream from bank to bank and sampled every ca. 3 m by swiftly immersing the activated anode into the water. The anode was led to the substrate at the spot where it entered the water and remained activated for a total of 10 s. Sampling points were approached carefully to avoid disturbance. Fishes immobilized by the electric field were immediately captured by a second operator with a hand net. The first operator accounted for variance in the electric field due to local water and stream bed properties by adjusting battery power to on average 350 W. Fishes obtained were identified in the field to the lowest feasible taxonomic level (see Miesen et al. [2016] for a checklist of inland fish species of Sulawesi), sex and maturity stage were documented where possible (specified in the following paragraph), and total length was measured to the nearest 1 mm. Representative individuals were anesthetized and killed in a saturated aqueous solution of chlorobutanol (1,1,1‐trichloro‐2‐methyl‐2‐propanol) following Geiger et al. (2016). Tissue samples (fin clips) were taken before fixation in formalin and stored in absolute ethanol. Specimens were then fixed in 4% formaldehyde and transferred to 70% ethanol for storage, or directly in 99.9% ethanol, for validation of determination and further analyses. Voucher specimens were stored in the fish collections of LIB (formerly ZFMK, Bonn) and MZB (BRIN, Bogor). Species recorded are listed in Table S2.

Species determination was based on the relevant literature (see, e.g., Kottelat et al. [1993] for an overview on freshwater fishes occurring in Sulawesi, and their characters, Keith et al. [2015] for an overview on amphidromous sycidiine gobies; the available original taxonomic publications were assessed where relevant, e.g. Huylebrouck et al., 2014; Keith et al., 2012; Keith, Lord, Darhuddin, et al., 2017; Keith, Lord, & Larson, 2017). Sex was noted for each mature individual where clearly possible, based on external sexual dimorphic characteristics such as colouration, fin traits, or shapes of body or head (Table S2). In cases where adults and juveniles could clearly be distinguished (juveniles were distinguished in those cases by lower body size and lack of external morphological characters distinguishing sexes) this was noted in the field. In sicydiinae gobies, a group where field determination largely depends on male characters, and diagnostic species characters that may include traits requiring microscopic inspection (Keith et al., 2015), males were assigned to species based on external characters where clearly visible, whereas females were identified to genus level at any location where more than one species (as determined based on male specimens) occurred. In the few cases the netting operator could clearly see and identify but not catch fishes immobilized by the anode field, these individuals were recorded with estimated sizes. In cases where species identification of a non‐obtained but clearly immobilized fish was uncertain, the sampling point was excluded from further analyses. Classification of species on use of freshwater (Table 1) is based on the literature available, for example Kottelat et al. (1993), Milton (2009), Keith et al. (2012, 2015), and Miesen et al. (2016).

TABLE 1.

Species of fishes recorded in streams of Sulawesi during fieldwork in 2019, with remarks on their general classification on use of freshwater; see Milton (2009) for classification of diadromous behavior to anadromy, catadromy and amphidromy.

| Species | Remark |

|---|---|

| Ambassidae | |

| Ambassis interrupta Bleeker, 1853 a | Catadromous |

| Anguillidae | |

| Anguilla celebesensis Kaup, 1857 | Catadromous |

| Anguilla marmorata Quoy & Gaimard, 1824 | Catadromous |

| Aplocheilidae | |

| Aplocheilus armatus (Van Hasselt, 1823) a | Freshwater, non‐native |

| Butidae | |

| Butis amboinensis (Bleeker, 1854) a | Amphidromous |

| Ophiocara porocephala (Valenciennes, 1837) a | Amphidromous |

| Oxyeleotris marmorata (Bleeker, 1852) a | Freshwater, non‐native |

| Channidae | |

| Channa striata (Bloch, 1793) a | Freshwater, non‐native |

| Cichlidae | |

| Flowerhorn a | Freshwater, non‐native |

| Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) a | Freshwater, non‐native |

| Clariidae | |

| Clarias batrachus (Linnaeus, 1758) a | Freshwater, non‐native |

| Cyprinidae | |

| Barbodes binotatus (Valenciennes, 1842) | Freshwater, non‐native |

| Osteochilus vittatus (Valenciennes, in Cuvier & Valenciennes, 1842) a | Freshwater, non‐native |

| Eleotridae | |

| Belobranchus belobranchus (Valenciennes, in Cuvier & Valenciennes, 1837) | Amphidromous |

| Belobranchus segura Keith, Hadiaty & Lord, 2012 | Amphidromous |

| Eleotris fusca (Schneider, 1801) | Amphidromous |

| Eleotris melanosoma Bleeker, 1853 | Amphidromous |

| Giuris cf. margaritaceus (Valenciennes, in Cuvier & Valenciennes, 1837) | Amphidromous |

| Gobiidae | |

| Glossogobius celebius (Valenciennes, in Cuvier & Valenciennes, 1837) | Amphidromous |

| Kuhliidae | |

| Kuhlia marginata (Cuvier, in Cuvier and Valenciennes, 1829) | Catadromous |

| Lutjanidae | |

| Lutjanus sp. a | |

| Megalopidae | |

| Megalops cyprinoides (Broussonet, 1782) a | Facultatively amphidromous |

| Muraenidae | |

| Gymnothorax polyuranodon (Bleeker, 1853) a | Facultatively catadromous |

| Ophichthidae | |

| Lamnostoma orientalis (McClelland, 1844) | Euryhaline |

| Lamnostoma mindora (Jordan & Richardson, 1908) | Euryhaline |

| Oxudercidae | |

| Awaous grammepomus (Bleeker, 1849) | Amphidromous |

| Awaous melanocephalus (Bleeker, 1849) | Amphidromous |

| Awaous ocellaris (Broussonet, 1782) | Amphidromous |

| Lentipes sp. a | |

| Lentipes mekonggaensis Keith, Hadiaty, Hubert, Busson & Lord, 2014 | Amphidromous, endemic |

| Mugilogobius rambaiae (Smith, 1945) a | Amphidromous |

| Pandaka trimaculata Akihito & Meguro, 1975 | Amphidromous |

| Periophthalmus argentilineatus Valenciennes, 1837 a | Amphidromous |

| Redigobius penango (Popta, 1922) a | Amphidromous |

| Schismatogobius bruynisi de Beaufort, 1912 | Amphidromous |

| Schismatogobius marmoratus (Peters, 1868) | Amphidromous |

| Schismatogobius risdawatiae Keith, Darhuddin, Sukmono & Hubert, 2017 | Amphidromous |

| Schismatogobius sapoliensis Keith, Darhuddin, Limmon & Hubert, 2018 a | Amphidromous |

| Schismatogobius saurii Keith, Lord, Hadiaty & Hubert, 2017 | Amphidromous |

| Sicyopterus cynocephalus (Valenciennes, in Cuvier & Valenciennes, 1837) | Amphidromous |

| Sicyopterus lagocephalus (Pallas, 1770) | Amphidromous |

| Sicyopterus longifilis de Beaufort, 1912 | Amphidromous |

| Sicyopus zosterophorus (Bleeker, 1856) | Amphidromous |

| Stenogobius ophthalmoporus (Bleeker, 1853) a | Amphidromous |

| Stenogobius blokzeyli (Bleeker, 1860) a | Amphidromous |

| Stiphodon pelewensis Herre, 1936 a | Amphidromous |

| Stiphodon semoni Weber, 1895 a | Amphidromous |

| Poeciliidae | |

| Poecilia reticulata Peters, 1859 | Freshwater, non‐native |

| Rhyacichthyidae | |

| Rhyacichthys aspro (Valenciennes, in Cuvier and Valenciennes, 1837) | Amphidromous |

| Scatophagidae | |

| Scatophagus argus (Linnaeus, 1766) a | Euryhaline |

| Synbranchidae | |

| Monopterus albus (Zuiew, 1793) a | Freshwater, non‐native |

| Syngnathidae | |

| Microphis retzii (Bleeker, 1856) a | Amphidromous |

| Microphis sp. a | |

| Microphis leiaspis (Bleeker, 1854) | Amphidromous |

| Microphis manadensis (Bleeker, 1856) a | Amphidromous |

| Terapontidae | |

| Terapon jarbua (Forskål, 1775) a | Euryhaline |

| Scorpaenidae | |

| Tetraroge barbata (Cuvier, in Cuvier & Valenciennes, 1829) | Euryhaline |

| Zenarchopteridae | |

| Nomorhamphus sagittarius Huylebrouck, Hadiaty & Herder, 2014 | Freshwater, endemic |

Species (entities) not fulfilling the minimum criterion of individual records, not included in further analyses.

The latitude, longitude, and altitude of each site were recorded by GPS. Temperature, conductivity, pH, and oxygen were measured at the first and the last sampling point of each site using a water quality data logger (PCE‐PHD 1 pH/Conductivity/Salt/Oxygen Water Quality Data Logger; www.pce-instruments.com). For each individual sampling point, the following series of microhabitat parameters were assessed. Water depth was measured with a scaled stick (handle of a net) to the nearest centimeter. Current velocity was determined by measuring the surface speed of a small (15 cm) stick between two points, 1 m upstream of the sampling point to 1 m downstream, calibrated at the first location using a Flowatch Flowmeter and categorized from 0 (0 m/s) to 5 (≥5 m/s). Distance to shoreline, that is the closest straight line of sampling point to the closest bank, was estimated to the nearest 1 m. Substrate was recorded as relative surface coverage at the sampling point, in a circle of 1 m in diameter, ranging from rock (≥10 cm) to gravel (<10 to ≥0.5 cm) to sand (<0.5 cm). Canopy cover was estimated as the percentage of shade covering the same area around the submerged anode. Submerged vegetation and submerged wood were recorded as the percentage of the cover per square meter.

2.4. Data analysis

Species accumulation curves were calculated to estimate sampling efficiency (Kindt, 2020). We followed Hutchinson (1957) in considering the ecological niche an n‐dimensional hyperspace of environmental parameters and investigated axes in ecological parameter space of the stream habitat in relation to species occurrences. Subsequent analyses were based on non‐null point abundance data and are restricted as a minimum criterion to entities (species, sex or maturity stages; see Table S2) represented by the occurrence of at least 10 individuals. For the focus on fish species entities in this study, we analyzed male and female data jointly. The square root of the percentage of each species per site was used to prevent any group from being overly dominant. One‐way analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) with a Bray–Curtis resemblance matrix based on the percentage contribution data was used to assess similarities of fauna composition. The Bray–Curtis resemblance matrix was also used for hierarchical agglomerative clustering utilizing the group average linkage approach (referred to as CLUSTER), in conjunction with the utilization of the Similarity Profiles Analysis (SIMPROF; Clarke et al., 2008). This specific test allowed us to identify groups of samples where the fish entity compositions were not significantly different from each other but were distinct from other groups. Similarity percentage analysis (SIMPER; Clarke, 1993) was used to determine the entities that characterized the assemblages within each of the site groups pinpointed as distinct by SIMPROF. We aimed to identify the species that significantly contributed to the differences in composition between each pair of distinct groups. We used the Biota and Environment matching analysis (BIOENV; Clarke & Ainsworth, 1993) to identify the combination of environmental variables that best accounted for the differences in the ichthyofaunal entity compositions among the clusters identified by SIMPROF. In this step of analysis, we employed the R‐packages “vegan” (Oksanen et al., 2022) and “clustsig” (Whitaker & Christman, 2015).

The non‐null point abundance data were then used for investigating multidimensional niche breadths with outlying mean index (OMI) analyses (Dolédec et al., 2000). OMI is an ordination technique that takes into account the ecological niche of each species within a community (Dolédec et al., 2000; Karasiewicz et al., 2017). It allows complex sets of stream habitat variables to be analyzed as descriptors of species‐specific niche hyperspaces (see, e.g., Heino, 2005; Prat & García‐Roger, 2018). Using the combination of R‐packages “vegan” (Oksanen et al., 2022), “ade4” (Dray & Dufour, 2007), and “sub‐niche” (Karasiewicz et al., 2017), habitat variables were first summarized by principal component analysis (PCA) and OMI analyses were run on the levels of the local communities. The OMI analyses provide three niche parameters: marginality, tolerance, and inertia. Marginality is a measure of the distance between the mean habitat conditions used by a species and the mean habitat conditions of the sampling area that integrates niche specialization according to habitat use (Dolédec et al., 2000). Tolerance describes the variance of the niche across the habitat resources assessed, with high values characterizing high amplitude of environmental conditions in generalists versus low values in specialists (Heino, 2005). Total inertia in turn characterizes the global niche overlap of species.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Records of fishes in Sulawesi streams

A total of 4632 individual fishes from 58 species belong to 24 families were caught at 2246 out of 5894 electrofishing points bearing fishes. Sites ranged in elevation from 5.5 to 321.5 masl, covering distances from approximately 0.07 to 20 km from the coast. The recorded fish species include 11 primary or secondary freshwater species, 34 amphidromous species, five euryhaline species, and five catadromous species. The mean number of native species recorded per site was 8.4 (min 2, max 19; mean non‐native species 0.9, min 0, max 9) (Figure S1 and Table S1). Species accumulation (Figure 1b) suggests that the sampling represents stream fish diversity well, although additional species are to be expected at low rates when extending the sampling.

Most of the species recorded are native to Sulawesi (46 species, 4248 individuals), two (one lifebearing Nomorhamphus sagittarius halfbeak and the hillstream goby Lentipes mekonggaensis from the south‐eastern province, sites 23, 25 and 28, 30) are endemic to the island. As expected (Kottelat et al., 1993; Miesen et al., 2016), the vast majority of the native fishes recorded are amphidromous (larvae drift to the sea, followed by upstream migration of juveniles), catadromous (migration to the sea for reproduction), or euryhaline (broad salt tolerance); Nomorhamphus halfbeaks are the only native secondary division freshwater fishes recorded (species confined to freshwater, but from lineage with some salt tolerance; Darlington Jr., 1957). Non‐native (also termed introduced, exotic or alien; species with origin outside Sulawesi, introduced by humans) species are present in 21 of the sites, at substantial rates (10 species, 263 individuals; Table S2). Thirty‐four out of the total 64 species recorded fulfilled the minimum criterion of at least 10 occurrences and were analyzed in detail.

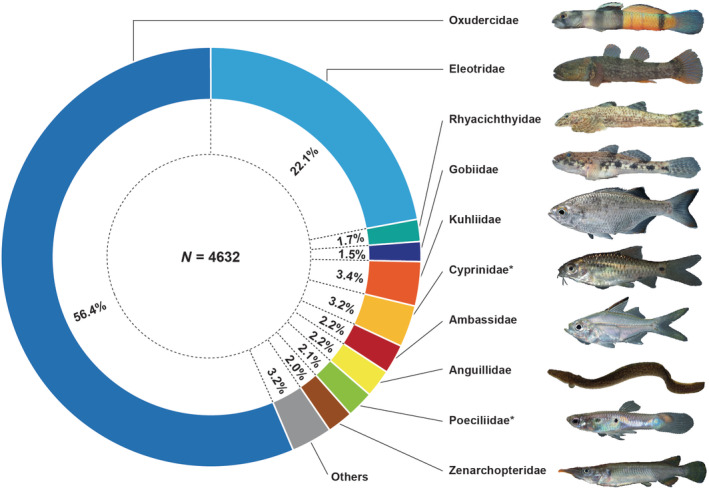

The Gobiiformes include the two most species‐rich families recorded, the Oxudercidae (Gobionellus‐like and mudskipper gobies, 11 genera, 22 species) and the Eleotridae (spinycheek sleepers, five species in three genera), as well as the Gobiidae (gobies, Glossogobius celebius) and the Rhyacichthyidae (loach gobies, Rhyacichthys aspro) (see Figure 2). Gobiiformes are likewise outstanding in terms of individual abundances, with adults of the climbing goby Sicyopterus longifilis (Oxudercidae) making up 19% of the total catch, followed by the throat‐spine gudgeon Belobranchus belobranchus (Eleotridae) with 7% (see Table S2 for details).

FIGURE 2.

Composition of the stream fish fauna recorded, in relative abundances, with the most frequent species per family in parentheses. Most abundant were the gobiiform families Oxudercidae (Sicyopus zosterophorus), Eleotridae (Belobranchus segura), Rhyacichthyidae (Rhyacichthys aspro), and Gobiidae (Glossogobius celebius), in total 81.8% of the individual catches. Moderately abundant were Kuhliidae (Kuhlia marginata), Cyprinidae (Barbodes binotatus), Ambassidae (Ambassis interrupta), Anguillidae (Anguilla celebesensis), Poeciliidae (Poecilia reticulata), and Zenarchopteridae (Nomorhamphus sagittarius). Non‐native families are marked with an asterisk (photographs by T.K.).

In a few cases, identification was not possible to species level. Lentipes sp. was recorded from one single individual female in a single stream (site 8, see Table S3), two individuals of Lutjanus from sites 10 and 16 were recorded but not preserved, Nomorhamphus from site 31 are small in size, and could not clearly be determined to species level in this study. The presence of more than one species of Anguilla, Eleotris, Awaous, and Schismatogobius at some sites (Anguilla six sites, Eleotris 12 sites, Awaous two sites, Schismatogobius 10 sites) posed determination challenges during point abundance campaigns, and individuals were recorded to genus level only in those cases. Female Sicyopterus and Stiphodon could not be determined unequivocally in the field, and were generally recorded at genus level.

3.2. Composition of fish communities

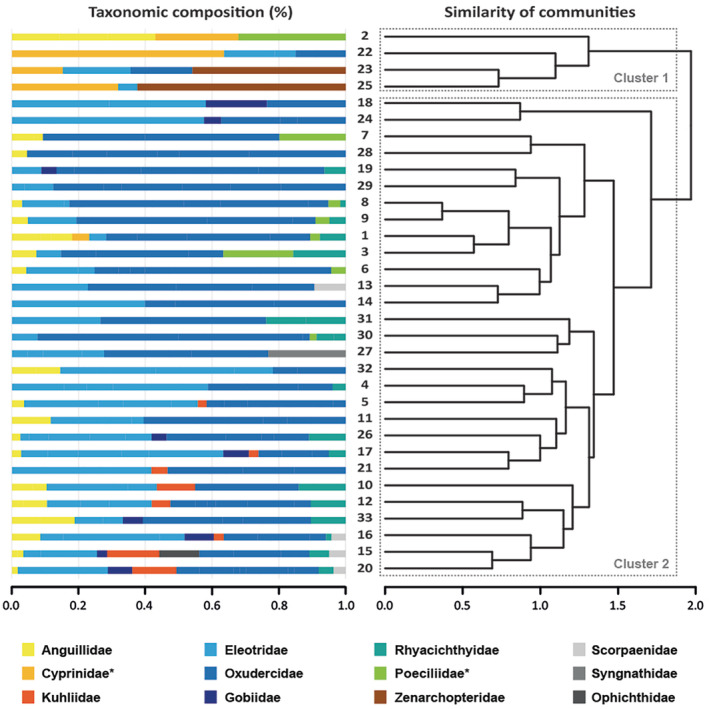

Sulawesi stream fish communities differ significantly in species composition (ANOSIM: R = 0.327, p < 0.05). Cluster analysis with similarity profiles (SIMPROF) revealed two distinct clusters of communities (Figure 3). Cluster 1 comprised four, cluster 2 the remaining 29 communities (Figure 3). Cluster 1 is characterized by high abundances of introduced Cyprinidae, accompanied by Zenarchopteridae at two locations (sites 23 and 25), at one location (site 2) by the family Poeciliidae (represented by the exotic guppy Poecilia reticulata), and lower numbers of native Oxudercidae, Eleotridae and Anguillidae (Figure 3). Communities in cluster 2 are dominated by gobies, mainly climbing gobies (Oxudercidae), the loach gobies (Rhyacichthyidae) as well as the family Eleotridae (represented by two species of throat‐spine gudgeons B. belobranchus and Belobranchus segura; for taxonomic composition at species level see Figure S4). At the species level, SIMPER analysis shows that the exotic spotted barb Barbodes binotatus (Cyprinidae) contributes most to the clustering of communities, followed by the endemic N. sagittarius (Zenarchopteridae), and the amphidromous threadfin goby S. longifilis (Oxudercidae) (Table S4). BIOENV analyses revealed that a combination of the variables pH, depth, current velocity, stony substrate, wood, and vegetation provides the best explanation for the SIMPROF clustering (total correlation of 0.567; see Table S5). Wood is the variable with the highest individual correlation with the fish population differentiation: Communities in Cluster 1 are characterized by a significant proportion of submerged wood, whereas wood is less dominant in the remaining 29 communities (Cluster 2).

FIGURE 3.

Cluster analysis with similarity profiles of fish community data per stream revealed two major clades. Left, Taxonomic composition (family level; for taxonomic composition at species level see Supp. Figure S4) based on abundance data; sampling site numbers given in the centre, as encoded in Figure 1. Right, results of a CLUSTER/SIMPROF analysis indicating differences in community composition among sites at a significance level of p = 0.05 with two significant clusters.

3.3. Species‐habitat association: ecological niche segregation along macro‐ and microhabitats

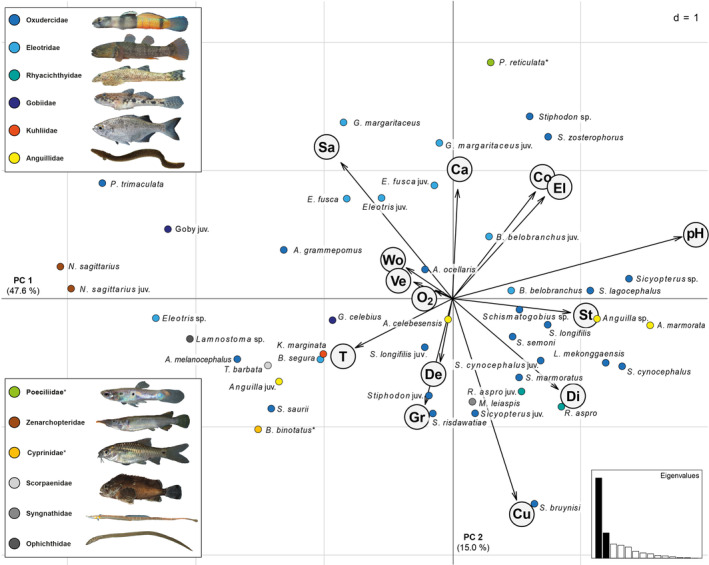

OMI analyses were used to assess fish records across habitat variables in detail. OMI analyses revealed two major PC axes that cover a total of 66% of the variance (Figure 4). PC1 (loading 47.6%) is dominated by increasing pH, stony substrate, distance to shoreline and elevation, and decreasing effects of sandy substrate and temperature (Table S7). PC2 (loading 15%) covers predominantly increasing effects of sand, canopy cover, conductivity, and elevation, with decreasing current velocity and gravel substrate (Table S7). Sandy substrates were negatively associated with distance to shore (PC1) or current velocity (PC2); gravel was frequent at lower altitudes, whereas rocky substrate shapes more elevated habitats. Taken together, the effects of elevation and contrasting substrates significantly shape both axes, whereas pH is the overall strongest parameter. Upstream sites tended to be characterized by higher pH and conductivity, and canopy cover was generally denser at higher altitudes. Waters at lower altitudes contained in proportion more gravel than stone or sand.

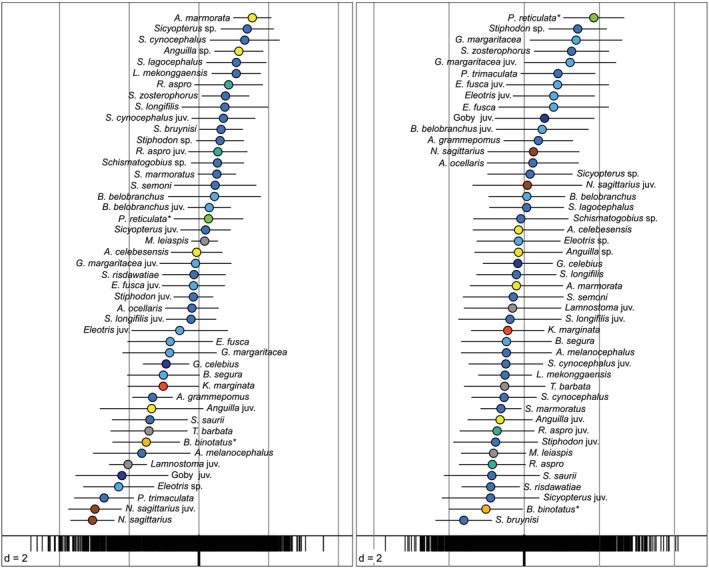

FIGURE 4.

Multivariate OMI analysis of fishes of Sulawesi coastal streams, with respect to environmental parameters. Canonical weights of habitat variables (clockwise: Ca, canopy cover; Co, conductivity; El, elevation; pH; St, stone; Di, distance to shore; Cu, current velocity; De, depth; Gr, gravel; T, temperature; O2, oxygen; Ve, vegetation; Wo, wood; Sa, sand), along the first two principal component axes (PCs; 46 fish entities analysed in total). Fish species subdivided to maturity stages where appropriate. Species illustrated per family as in Figure 2, complemented by the less abundant Scorpaenidae (Tetraroge barbata: light grey), Syngnathidae (Microphis leiaspis: dark grey), Ophichthidae (Lamnostoma sp.: black). Non‐native families marked with an asterisk. Vectors visualise relative importance and direction of habitat variables in the ordination space. Axis loadings are shown in the inlay box; loadings of the first two PCs sum up to 66% of the total variance. Effects of macrohabitat, mainly vectors associated with altitude, and combined effects of microhabitat variation, are associated with fish communities covering a wide array of the habitat space available (Photos by T.K).

Fishes are widely spread throughout the available habitat niche space (Figure 4). Most gobies of the family Oxudercidae occur in association with high current velocity and tend to use gravel and stony substrates, together with eels (Anguillidae) and the loach goby (Rhyacichthyidae). Both Awaous species differ from the remaining Oxudercidae analyzed here by inhabiting sandy habitats. They share proximity to sand with the majority of the sleeper gobies (Eleotridae: Giuris, Eleotris), with tendencies towards increasing shelter and structure by dense canopy and presence of submerged wood and vegetation. The eleotrid genus Belobranchus differs from the other eleotrids and shows pronounced interspecific segregation: B. belobranchus aggregate with Oxudercidae and Anguillidae at elevated stony substrates, whereas the closely related B. segura inhabit warmer habitats closer to the sea inhabited by estuarine fishes such as the flagtail Kuhlia marginata (Kuhliidae), the Celebes goby G. celebius (Gobiidae), the beared roguefish Tetraroge barbata (Scorpaenidae), or snake eels Lamnostoma sp. (Ophichthidae). The endemic Nomorhamphus freshwater halfbeak (Zenarchopteridae) and the dwarf goby Pandaka trimaculata (Oxudercidae) differ in their habitat properties by using structured banks. The two most abundant exotic fishes, P. reticulata and B. binotatus, are likewise on the outside of the range of the stream fish community, inhabiting mostly warmer lowlands (B. binotatus) or shallows of structured highland habitats (P. reticulata). In most cases where juveniles were recorded, their habitat follows the same major determinants as in adult conspecifics (N. sagittarius, R. aspro, Sicyopterus cynocephalus, S. longifilis, Stiphodon semoni, Eleotris fusca, B. belobranchus), whereas juvenile Anguilla segregate in habitat use from adult congenerics.

Niche specialization (marginality) is significant in 44 of the 46 fish entities analyzed under the null hypothesis that each is indifferent to its environment (Dolédec et al., 2000) (Table S6). Most specialized are the barhead pipefish Microphis leiaspis (OMI = 62.9), followed by the goby Awaous ocellaris and juvenile Lamnostoma (OMI = 61.4, 60.03); B. belobranchus (OMI = 4.9), S. longifilis (OMI = 8), and Schismatogobius sp. (OMI = 8.4) show the least specialized habitat use.

Overall niche breadth (OMI tolerance of habitat conditions, i.e. niche variance across habitats, horizontal lines in Figure 5) at PC1 was highest in juvenile Anguilla followed by Awaous melanocephalus, juvenile Eleotris, Giuris margaritaceus, juvenile gobies, and adult B. belobranchus, whereas M. leiaspis, juvenile Lamnostoma, and adult Anguilla have the lowest tolerance. At PC2, tolerance is highest in E. fusca, the juveniles of N. sagittarius, S. longifilis, and E. fusca, contrasted by narrow niches in three species of Schismatogobius (Schismatogobius marmoratus, Schismatogobius bruynisi, Schismatogobius risdawatiae), L. mekonggaensis, and Stiphodon sp. (Table S6).

FIGURE 5.

Niche position of Sulawesi streams fishes along the first two PCA axes based on outlying mean index (OMI) analyses. The position of each species and maturity stage (dots; colors encode families, as specified in Figure 3) is the weighted mean of species distribution in each point (the bottom vertical bar in the panel). Non‐native fishes are marked with an asterisk. The position of the black vertical bars at the bottom of the panel corresponds to the respective loading of each sampling point in the habitat parameter space, with increasing pH and conductivity (from the left to right) for PC1 (a), and with increasing current velocity along with a decreasing presence of sandy substrates (from the right to the left) for PC2 (b).

Niches of fishes vary gradually along the first two OMI axes, and niche breadths widely overlap (Figure 5). Species, sexes, and size classes segregate along PC1 from fishes typically inhabiting lower reaches (e.g., T. barbata, non‐native B. binotatus, Lamnostoma, P. trimaculata, Eleotris) to those expected in more elevated and colder, swifty streams (e.g., Anguilla marmorata, S. cynocephalus, R. aspro, and L. mekonggaensis). The outlier position of the N. sagittarius in PC1 (Figure 4) translates into a likewise extreme placement of niche position (Figure 5), a pattern attributed to the unique habitat niche of the species, inhabiting the shady shallows under vegetation or wood. Niches in PC2 likewise vary gradually, though with a higher overlap in niche breadths, describing a gradient in habitat niches from fishes inhabiting streams with sandy substrates and low water flow (e.g., G. margaritaceus, Sicyopus zosterophorus, N. sagittarius, E. fusca, P. trimaculata, and non‐native P. reticulata) to those associated with swiftly moving water (e.g., S. bruynisi, R. aspro, and L. mekonggaensis). This gradient is also affected by distance from the shore and the presence of gravel substrates, indicative of species such as B. binotatus, S. risdawatiae, S. saurii, M. retzii, and T. barbata.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Composition of Sulawesi stream fish communities

The composition of Sulawesi coastal stream fish communities is similar to that reported from the island drainages of Buton and Kabaena off southeast Sulawesi (Tweedley et al., 2013): The communities are largely shaped by amphidromous species with large distribution areas and contain only few endemic species. Amphidromous gobioids (including Oxudercidae, Eleotridae, Butidae, Gobiidae, and Rhyacichthyidae) are dominant throughout most habitats, in terms of both species diversity and abundances. Also, the majority of other lineages detected, such as Kuhliidae, Lutjanidae, Syngnathidae, or Teraponidae, are composed of species that are capable of crossing marine waters (Berra, 2007). Only a small fraction of the native species detected here, namely the Nomorhamphus, are in all developmental stages strictly confined to freshwaters (Brembach, 1991).

Dominance of amphidromous fishes in Sulawesi's coastal streams is similar to fish communities of streams in smaller, isolated tropical islands such as Fiji (Jenkins et al., 2010), Puerto Rico (Engman et al., 2017), Hawaii (McDowall, 2003), or Micronesia (Donaldson & Myers, 2002). Explanations include spatial isolation from continental faunas, temporal impermanence of small insular drainages, and the ability of amphidromous fishes to successfully colonize remote habitats (Jamonneau et al., 2024; Jenkins et al., 2010; Keith et al., 2015). Oceanic dispersal enables colonization of streams isolated by marine barriers but requires high fecundity and potentially long larval phases, as shown for sicydiinae Oxidercidae (Jamonneau et al., 2024). In turn, high dispersal rates can maintain patchy distributions and enable persistence in habitats at the margin of species adaptation (Hubert, Calcagno, et al., 2015). The composition of stream fish communities based primarily on oceanic dispersal, as observed here for Sulawesi coastal streams, differs accordingly sharply from continental waters, where species composition is typically dominated by lineages completing their life cycle in freshwaters (Berra, 2007).

The segregation of the individual stream fish species along the habitat axes recorded here largely matches the available literature (e.g., Keith et al., 2015; Tweedley et al., 2013). The sicydiinae S. cynocephalus, S. longifilis, S. lagocephalus, L. mekonggaensis, and S. semoni form together with R. aspro, S. bruynisi, S. marmoratus, S. risdawatiae, and A. marmorata rheophilic assemblages at predominantly hard substrate habitats. Notably, M. leiaspis is also associated with high current velocity habitats (Figure 3); inspection of microhabitat data alone (Figure S1), however, suggests that gravel substrate is apparently most relevant for this species. Combined with its very narrow habitat niche (Figure 3), we assume that the flow shadows of gravel provide a microhabitat suited for this pipefish.

Awaous are known for using predominantly a contrasting habitat, sandy habitats at calmer sites (e.g., Serov et al., 2006). The aggregation of the eleotrids E. fusca and G. margaritaceus at sandy habitats coincides with structure in terms of canopy cover, submerged wood, and vegetation, vectors of partially (submerged wood and vegetation) lower overall importance that are nevertheless apparently important for those gudgeons. The present results confirm the relevance of sandy substrate for Eleotris (Tweedley et al., 2013). As noted in the original description (Keith et al., 2012), the amphidromous eleotrid B. segura was here confirmed for lower, warmer sections of coastal streams, differing substantially from the only known congeneric species, B. belobranchus. The latter is present at more elevated and rocky sites, shared with species of the rheophilic species assemblage.

The co‐occurrence of Lamnostoma sp., K. marginata, T. barbata, and G. celebius reflects an assemblage typical for lower reaches of streams and rivers in the larger region (Kottelat et al., 1993; Tweedley et al., 2013). The wide scattering of Schismatogobius species habitats is considerable, ranging from the rheophilic (S. bruynisi, S. marmoratus, S. risdawatiae) close to the lower reaches assemblage (S. saurii). As in Microphis, the focal analysis of microhabitat data confirms hints from the literature (Jenkins & Boseto, 2005; Keith, Lord, Darhuddin, et al., 2017; Keith, Lord, & Larson, 2017) that gravel is the more relevant parameter also for Schismatogobius. The habitat niche of N. sagittarius differs substantially from Microphis but is likewise rather narrow. Its composition meets the habitat characterisation given in the species description (Huylebrouck et al., 2014) as well as the habitats used by Nomorhamphus in Buton and Kabaena (Tweedley et al., 2013): bank sites structured and sheltered by dense riparian vegetation and submerged wood.

The present data reflect the current focus on coastal streams, do not consider species restricted to the island's large lakes (Herder et al., 2006; Vaillant et al., 2011; see Tweedley et al. [2013] for discussion of endemism in Sulawesi lakes vs. streams), and do not cover most of the local endemic species with rather narrow distribution areas such as ricefishes, sailfin silversides, gobioids, or most of the halfbeak diversity (e.g., Herder, Hadiaty, & Nolte, 2012; Hilgers & Schwarzer, 2019; Keith et al., 2021; Kraemer et al., 2019). Designed for assessing habitat use on the level of individual plots, across the diversity of microhabitats within streams, point abundance electrofishing has the major advantage of providing detailed data on habitat–fish association, but is in turn generally less efficient in detecting the full set of species present at a site compared to classical electrofishing targeting the full stretch of a stream, as exemplified, for example, by Tweedley et al. (2013) or Jenkins et al. (2010). The species record presented here is thus not claiming completeness. In contrast, additional diversity is to be expected when performing more intensive (e.g., Gani et al., 2021) or even repeated (Pottier et al., 2022) sampling within drainages. Saturating species accumulation does, however, suggest that the sampling efforts undertaken here cover major elements of the species community at the sites visited (Willott, 2001).

In contrast to Tweedley et al. (2013), the present sampling does not aim at covering communities along the altitudinal gradient of selected drainages, but focuses on spatially separated freshwater communities along Sulawesi's coasts. We thus expected less dominance of altitudinal gradient effects in our data compared to Tweedley et al. (2013) or other studies targeting within‐drainage variation (e.g., Suvarnaraksha et al., 2012; Walsh et al., 2022). The nevertheless significant role of environmental axes clearly related to altitude does, however, demonstrate that this major environmental gradient clearly shapes large‐scale patterns also in Sulawesi coastal stream fish communities.

4.2. Non‐native fishes

The first records of introductions of non‐native fishes in Sulawesi date back to the early 20th century (Weber, 1913), but work on the ancient lakes demonstrated that additional releases continuously added further species, with severe consequences (Herder et al., 2022; Herder, Schliewen, et al., 2012). In the coastal streams, non‐native fishes were recorded at 11 of the sites sampled. A total of 10 non‐native taxa contributed a total of 6% to the total catches (Figure 2). These range from predators (walking catfish Clarias, striped snakehead Channa striata) to benthivores (B. binotatus, Osteochilus vittatus). Channa, Clarias, Barbodes, Osteochilus, Monopterus, and Oreochromis are food fishes of predominantly local importance, guppies P. reticulata and mosquitofish Gambusia affinis are used for mosquito control; guppies are also popular as aquarium pets (Berra, 2007). The blue panchax Aplocheilus armatus was seen predominantly in microhabitats affected by some degree of human activity such as nearby agriculture areas, supporting the view that it is exotic in Sulawesi (see Herder et al. [2022] for discussion). The marble goby Oxyeleotris marmorata is a valuable food fish originating from rivers in mainland South‐East Asia and Sunderland (Berra, 2007), and is apparently also non‐native in Sulawesi. Introduction of this large predator with broad salt tolerance to Tondano Lake in North Sulawesi has prompted concerns regarding its impact on the area's native freshwater fish diversity (Lestari et al., 2019; Mamangkey et al., 2022).

Also with respect to exotic fishes, Tweedley et al.'s (2013) study remains the only previous comprehensive work reporting original data from multiple riverine sites and drainages in Sulawesi. Among the exotics recorded here from mainland Sulawesi, their data from Buton and Kabaena collected in 2001 and 2002 likewise report A. armatus, C. striata, O. niloticus, and Clarias batrachus, whereas five of the species recorded here (B. binotatus, O. vittatus, P. reticulata, Monopterus albus, and “Flowerhorn” cichlid) were not found in the two smaller islands then. In turn, the present study did not reveal records of Rasbora, Oreochromis mossambicus, Anabas testudineus, or Clarias leiacanthus (as C. teijsmanni; see Kottelat, 2013) made by Tweedley et al. (2013). In all but two species, records of the present study were occasional, with very low abundances (Table S2). Exceptions are B. binotatus (total record 147 individuals from five sites) and P. reticulata (total record 96 individuals from eight sites). The likely underestimated distribution of species with low abundances in the present study highlights the need for systematic surveys as a basis for informed management. Consequences of non‐native fish invasions and the resulting biotic homogenization are among the most severe threats for freshwater biodiversity and ecosystems on a global scale (Danet et al., 2024; Reid et al., 2019). Ornamental cichlid species multiplied enormously in Sulawesi's ancient lakes, where they threaten the endemic biotas (Herder et al., 2022; Herder, Schliewen, et al., 2012); in Fiji streams, the presence of just one exotic cichlid species (Oreochromis, also reported here) was associated with the disappearance of on average 11 species per drainage (Jenkins et al., 2010).

The two most abundant exotic fish species recorded and analyzed here, B. binotatus and P. reticulata, link into the native communities at their margins of habitat space (Figures 4 and 5, PC2). Moderate niche breadth appears at first glance surprising, but is plausible given the so far patchy distribution of these introduced species. Overlap in niche breadth with native fishes is, however, substantial (Figure 5). Taken together, the present results confirm that the stocking of non‐native fishes was and is performed in Sulawesi stream habitats, with risks and consequences that remain to be explored. They show that non‐native fishes have become locally dominant at some sites (Figure 3) and reveal with O. marmorata a non‐native species not previously reported from Sulawesi streams. Success of non‐native species in Sulawesi streams might benefit from low competition in niches at the margin of communities, where they nevertheless have the potential to affect several native species by overlapping dimensions of habitat niche use.

4.3. Environmental variation shaping community structure

Stream fish communities are shaped by multiple factors, including habitat and biotic interaction (Tesfay, 2016), depending on the region and ecosystem context (Lowe‐McConnell, 1987). Community composition expectedly varies among and within streams, with elevation and associated variables being the main drivers (Gerhard et al., 2004; Ibañez et al., 2009). The two Sulawesi site clusters (Figure 3) distinguish communities dominated by the exotic B. binotatus or the endemic N. sagittarius from those characterized by the most abundant species recorded here, the native amphidromous S. longifilis (Table S4). Associated with this clustering are combined effects of the variables pH, depth, and current velocity as well as the presence of stony substrates, wood, and vegetation (Table S5). In sum, similarity on the community level suggests that effects on the scale of macrohabitat (water chemistry and flow regime) as well as variables of local microhabitats shape stream fish assemblage composition.

The joint analysis of habitat–species interactions generally confirms these findings and shows that the species spread widely over the multivariate space available (Figure 4). pH is among the dominant variables structuring the global community of Sulawesi stream fishes, associated with elevation, conductivity, and decreasing temperature. This clearly reflects the relevance of the altitudinal gradient. Species distribution is substantially affected by current velocity, distance to shoreline, substrates, and canopy cover, parameters that directly or indirectly combine aspects of macro‐ and microhabitat. Niche occupation changes gradually along the two major axes of habitat variation (Figures 4 and 5); the dense arrangement of species niches along these axes suggests tight patterns of niche use, with substantial overlaps in niche breadths (Figure 5).

The present data suggest that juvenile and adult fishes share similar habitat niches in most cases where both are investigated (E. fusca, G. margaritaceus, N. sagittarius, R. aspro, S. cynocephalus, S. longifilis), whereas juveniles differ from the adult eel species included, as expected in catadromous Anguilla, in occupying mainly less elevated and warmer habitats. Ontogenetic habitat segregation in fishes is known from very different ecosystems (Pratchett et al., 2008; Schlosser, 1991), including tropical stream fishes (Herder & Freyhof, 2006), but appears not to be a prominent mechanism in shaping Sulawesi coastal stream fish niches.

The finding that Sulawesi stream communities are substantially affected by altitude matches a general trend in lotic freshwaters, from temperate (e.g., Askeyev et al., 2017; Kirk et al., 2021) to tropical (e.g., Soo et al., 2021; Suvarnaraksha et al., 2012; Walsh et al., 2022) regions. It meets the results of Tweedley et al. (2013) on the Buton and Kabaena ichthyofauna, confirming the relevance of altitude for Sulawesi stream fish communities. Beyond previous findings, the present study adds the perspective of microhabitats, and identifies a fine‐scaled pattern of microhabitat segregation along both of the most relevant habitat axes.

We assume underestimation of niche coverage of those fishes that are expectedly or evidently present in Sulawesi streams, but not covered by the analyses here, due to the present focus and setup. While this underestimation could to some degree be approached by increasing sampling efforts in future studies, it appears unlikely that inclusion of further species will change the general picture of fine‐scaled distribution of habitat niches within the stream fish communities; in contrast, we predict that incorporation of additional species would further increase diversity in habitat use and thus add to community complexity.

The present data are based on dry season sampling, excluding possible seasonal effects, and covering wide, but not all areas of 1200‐km long Sulawesi. Restrictions are mostly attributed to logistics such as time in the field available, but also to challenges when assessing fish communities under high water level conditions, from site access to wading to the limits of backpack electrofishing. Jenkins and Jupiter (2011) managed to analyze seasonal effects in Fiji stream fish communities and found that season was not a significant driver of community structure at basin level, but seasonal exclusivity was evident in a number of species. Seasonal migrants from the sea and the estuaries, and differences in representation of species due to their swimming ability were considered plausible explanations. Milton (2009) likewise concluded that tropical diadromous fishes tend to migrate during monsoonal floods, which might suggest that wet season data would deviate from dry season results by increased presence of species migrating upstream from the estuaries into the coastal streams. In addition, migratory and non‐migratory fishes might perform seasonal shifts in habitat use on the scales of micro and macrohabitat (Maki‐Petäys et al., 1997; Smokorowski & Pratt, 2007), potentially adding further complexity to the picture of habitat niche use. We accordingly stress that including seasonal data will be an important next step for deeper understanding of stream fish ecology in the Wallacea. The same applies to possible long‐term effects from abiotic (e.g., El Niño, habitat degradation) and/or biotic (e.g., fluctuating population sizes, expansion of non‐native species) drivers of variation that might affect local communities. As dynamics from both of these possible effects, seasonality and long‐term variation, most likely add further complexity to the interaction within stream fish communities, we conclude that the present results most likely underestimate niche complexity by the exclusion of temporal niche dynamics on the scale of both stream fish species and their communities.

Taken together, the present results suggest that habitat shapes assembly processes in coastal streams, based on recruitment from metacommunities dispersing across marine waters. Community assembly is the process of aggregating species during the development of ecological communities (Fukami, 2015; HilleRisLambers et al., 2012; Mittelbach & Schemske, 2015). A habitat's ecological characteristics constitute a first environmental filter for potentially settling species and competitive interactions, and predation may further enhance the impact of environmental filtering and affect the composition of freshwater fish communities (Borcard et al., 1992; Montaña et al., 2014; Peres‐Neto, 2004; Ricklefs, 2004; Sternberg & Kennard, 2014; Yeager et al., 2011). Sulawesi stream fish communities are composed of species from the metacommunity of fishes able to reach and enter freshwater streams by different pathways: upstream migration of juveniles (amphidromous and anadromous fishes) and adult fishes entering streams from the sea (euryhaline and some catadromous species). For the comparatively few native freshwater species with low salt tolerance (secondary freshwater fishes, only Nomorhamphus in the present data), headwater captures or floodings (Berra, 2007) appear as more plausible mechanism of dispersal.

Environmental filtering may act on different scales in this system. On the larger scale, habitat variation along the altitudinal gradient and related effects such as water chemistry clearly shape community structure. The present study contributes a microhabitat view. Incorporating the complex mosaic of habitats that frequently supports various adaptations is considered a main challenge when analyzing riverine freshwater communities (Arrington et al., 2005). Stream fishes here show fine‐scaled patterns of segregation also on the small scale, with strong effects of substrates and current velocity, complemented by variables less relevant for the global segregation within the community, but strong effects on individual species or species groups (e.g., structure by wood and vegetation for Nomorhamphus, relevance of gravel substrate for Schismatogobius). Some habitat parameters span scales from macro‐ to microhabitat, like current velocity varying among macro‐, but also among microhabitats. The point abundance approach provides a strong tool for identifying the relevance of parameter variation irrespective of these scales, as it relates individual occurrence to the actual spot of occurrence at the time of sampling.

The current focus on habitats not obviously affected by major anthropogenic effects such as larger dams, substantially altered habitats, or obvious absence of native fishes enables a less biased understanding of patterns shaping natural communities, but ignores the actual environmental reality of large parts of the coastal freshwaters in the region (Baumgartner & Wibowo, 2018). The dominance of fishes depending on corridors to the sea clearly shows that Sulawesi's stream ecosystems require connectivity. As in other tropical island systems (e.g., Atminarso et al., 2024; Cooney & Kwak, 2013), dams and other obstacles built for different purposes in Sulawesi come with the obvious effect of severely changing stream ecosystems by reducing or even preventing connectivity. Assessing the impacts from blocked connectivity and from other kinds of habitat change, understanding the consequences for freshwater communities, and strategies for preserving the biota of coastal streams are urgently needed.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The coastal stream fish communities of Sulawesi are dominated by species colonizing freshwaters from the sea. The Gobiiformes, mainly widespread Oxudercidae and Eleotridae, are most relevant in terms of abundances and species diversity. The vast majority of the species is accordingly amphidromous, followed by euryhaline fishes. The halfbeaks, representing endemic species here, are locally abundant and show unique patterns of habitat use. As in Buton and Kabaena (Tweedley et al., 2013), the altitudinal gradient substantially affects species composition. The point abundance approach extends this view on the scale of microhabitats, demonstrating that patterns of habitat niche use are fine‐scaled and complementary, covering a wide array of the habitat space available. Environmental filtering provides a framework that can explain the habitat niche segregation observed, from strong altitudinal effects to pronounced patterns of niche segregation on the small scale. Some non‐native fishes are locally abundant and pose substantial potential for changing communities. In sum, connectivity with the estuaries and habitat diversity on altitudinal to local scales appears essential for maintaining the natural diversity of coastal stream fishes in Sulawesi.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

F.H. and F.W.M. planned the study. F.H. designed data acquisition. L.W., T.K., and F.W.M. collected field data. L.W. and F.H. analyzed the data. L.W. and F.H. wrote the manuscript with contributions from T.K., J.M., F.W.M., D.W., and F.B. F.H. supervised the study. D.W., F.B., and L.W. organized the permitting processes in Indonesia, enabling fieldwork. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Supporting information

FIGURE S1. Bar chart showing the elevation of each site.

FIGURE S2. Correlation graph showing the correlation between elevation and macrohabitat parameters.

FIGURE S3. Multivariate OMI analysis of fishes of Sulawesi coastal streams, with respect to microhabitat parameters.

FIGURE S4. Species composition based on abundance data.

DATA S1. Tables.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Research Center for Biology, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) (presently Research Center for Biology, National Research and Innovation Agency or Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional [BRIN] and the Kementerian Negara Riset dan Teknologi [RISTEK] [presently also BRIN]) for permission to conduct research in Indonesia. Thanks to Serkan Wesel for help in preparing field logistics. Fieldwork was funded by a research grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to F.H. (DFG HE 5707/7‐1). T.K. is grateful to the German Academic Scholarship Foundation for providing a travel grant. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Wantania, L. L. , Koppetsch, T. , Möhring, J. , Miesen, F. W. , Wowor, D. , Boneka, F. , & Herder, F. (2025). Sulawesi stream fish communities depend on connectivity and habitat diversity. Journal of Fish Biology, 106(2), 358–375. 10.1111/jfb.15944

REFERENCES

- Arrington, D. A. , Winemiller, K. O. , & Layman, C. A. (2005). Community assembly at the patch scale in a species rich tropical river. Oecologia, 144, 157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askeyev, A. , Askeyev, O. , Yanybaev, N. , Askeyev, I. , Monakhov, S. , Marić, S. , & Hulsman, K. (2017). River fish assemblages along an elevation gradient in the eastern extremity of Europe. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 100, 585–596. [Google Scholar]

- Astorga, A. , Death, R. , Death, F. , Paavola, R. , Chakraborty, M. , & Muotka, T. (2014). Habitat heterogeneity drives the geographical distribution of beta diversity: The case of New Zealand stream invertebrates. Ecology and Evolution, 4, 2693–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atminarso, D. , Baumgartner, L. J. , Watts, R. J. , Rourke, M. L. , Bond, J. , & Wibowo, A. (2024). Evidence of fish community fragmentation in a tropical river upstream and downstream of a dam, despite the presence of a fishway. Pacific Conservation Biology, 30(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, L. J. , & Wibowo, A. (2018). Addressing fish‐passage issues at hydropower and irrigation infrastructure projects in Indonesia. Marine and Freshwater Research, 69(12), 1805–1813. [Google Scholar]

- Berra, T. M. (2007). Freshwater fish distribution (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borcard, D. , Legendre, P. , & Drapeau, P. (1992). Partialling out the spatial component of ecological variation. Ecology, 73, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Brembach, M. (1991). Lebendgebärende Halbschnäbler. Untersuchungen zur Verbreitung, Morphologie, Systematik und Fortpflanzungsbiologie der lebendgebärenden Halbschnäbler der Gattungen Dermogenys und Nomorhamphus (Hemirhamphidae: Pisces). Solingen, Natur und Wissenschaft.

- Clarke, K. (1993). Nonparametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Austral Ecology, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K. , & Ainsworth, M. (1993). A method of linking multivariate community structure to environmental variables. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 92, 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K. R. , Somerfield, P. J. , & Gorley, R. N. (2008). Testing of null hypotheses in exploratory community analyses: Similarity profiles and biota‐environment linkage. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 366(1–2), 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney, P. , & Kwak, T. (2013). Spatial extent and dynamics of dam impacts on Tropical Island freshwater fish assemblages. Bioscience, 63, 176–190. [Google Scholar]

- Copp, G. H. (1989). Electrofishing for fish larvae and 0+ juveniles: Equipment modifications for increased efficiency with short fishes. Aquaculture and Fisheries Management, 20, 453–462. [Google Scholar]

- Copp, G. H. , & Penaz, M. (1988). Ecology of fish spawning and nursery zones in the floodplain, using a new sampling approach. Hydrobiologia, 169, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Danet, A. , Giam, X. , Olden, J. D. , & Comte, L. (2024). Past and recent anthropogenic pressures drive rapid changes in riverine fish communities. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 8, 442–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlington, P. J., Jr. (1957). Zoogeography. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruyn, M. , Rüber, L. , Nylinder, S. , Stelbrink, B. , Lovejoy, N. , Lavoué, S. , Tan, H. , Nugroho, E. , Wowor, D. , Ng, P. , Siti‐Azizah, M. , Rintelen, T. , Hall, R. , & Carvalho, G. (2013). Paleo‐drainage basin connectivity predicts evolutionary relationships across three southeast Asian biodiversity hotspots. Systematic Biology, 62, 398–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolédec, S. , Chessel, D. , & Gimaret‐Carpentier, C. (2000). Niche separation in community analysis: A new method. Ecology, 81(10), 2914–2927. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T. , & Myers, R. (2002). Insular freshwater fish faunas of Micronesia: Patterns of species richness and similarity. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 65, 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Doorenweerd, C. , Ekayanti, A. , & Rubinoff, D. (2020). The Dacini fruit fly fauna of Sulawesi fits Lydekker's line but also supports Wallacea as a biogeographic region (Diptera, Tephritidae). ZooKeys, 973, 103–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dray, S. , & Dufour, A. (2007). The ade4 package: Implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. Journal of Statistical Software, 22(4), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Engman, A. , Kwak, T. , & Fischer, J. (2017). Recruitment phenology and pelagic larval duration in Caribbean amphidromous fishes. Freshwater Science, 36, 851–865. [Google Scholar]

- Fukami, T. (2015). Historical contingency in community assembly: Integrating niches, species pools, and priority effects. Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics, 46, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gani, A. , Adam, M. I. , Bakri, A. , Adriany, D. T. , Herjayanto, M. , Nurjirana., Mangitung, S. F. , & Andriyono, S. (2021). Diversity studies of freshwater goby species from three rivers ecosystem in Luwuk Banggai, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. IOP conference series: Earth and Environmental Science, 718, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gani, A. , Suhendra, N. , Herder, F. , Schwarzer, J. , Möhring, J. , Montenegro, J. , Herjayanto, M. , & Mokodongan, D. (2022). A new endemic species of pelvic‐brooding ricefish (Beloniformes: Adrianichthyidae: Oryzias) from Lake Kalimpa'a, Sulawesi, Indonesia. Bonn Zoological Bulletin, 71, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, M. F. , Schreiner, C. , Delmastro, G. B. , & Herder, F. (2016). Combining geometric morphometrics with molecular genetics to investigate a putative hybrid complex: A case study with barbels Barbus spp. (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Journal of Fish Biology, 88(3), 1038–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard, P. , Moraes, R. , & Molander, S. (2004). Stream fish communities and their associations to habitat variables in a rain forest reserve in southeastern Brazil. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 71, 321–340. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R. (2011). Australia–SE Asia collision: Plate tectonics and crustal flow. The SE Asian gateway: History and tectonics. Geological Society of London Special Publications, 355, 75–109. [Google Scholar]

- Heino, J. (2005). Positive relationship between regional distribution and local abundance in stream insects: A consequence of niche breadth or niche position? Ecography, 28, 345–354. [Google Scholar]

- Herder, F. , & Freyhof, J. (2006). Resource partitioning in a tropical stream fish assemblage. Journal of Fish Biology, 69(2), 571–589. [Google Scholar]

- Herder, F. , Hadiaty, R. , & Nolte, A. (2012). Pelvic‐fin brooding in a new species of riverine ricefish (Atherinomorpha: Beloniformes: Adrianichthyidae) from Tana Toraja, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 60, 467–476. [Google Scholar]

- Herder, F. , Möhring, J. , Flury, J. , Utama, I. , Wantania, L. , Wowor, D. , Boneka, F. , Stelbrink, B. , Hilgers, L. , Schwarzer, J. , & Pfaender, J. (2022). More non‐native fish species than natives, and an invasion of Malawi cichlids, in ancient Lake Poso, Sulawesi, Indonesia. Aquatic Invasions, 17, 72–91. [Google Scholar]

- Herder, F. , Nolte, A. , Pfaender, J. , Schwarzer, J. , Hadiaty, R. K. , & Schliewen, U. K. (2006). Adaptive radiation and hybridization in Wallace's Dreamponds: Evidence from sailfin silversides in the Malili Lakes of Sulawesi. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 275, 2178–2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herder, F. , Schliewen, U. , Geiger, M. , Hadiaty, R. , Gray, S. , McKinnon, J. , Walter, R. , & Pfaender, J. (2012). Alien invasion in Wallace's Dreamponds: Records of the hybridogenic “flowerhorn” cichlid in Lake Matano, with an annotated checklist of fish species introduced to the Malili Lakes system in Sulawesi. Aquatic Invasions, 7(4), 521–535. [Google Scholar]

- Hilgers, L. , & Schwarzer, J. (2019). The untapped potential of medaka and its wild relatives. eLife Sciences, 8, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HilleRisLambers, J. , Adler, P. B. , Harpole, W. S. , Levine, J. M. , & Mayfield, M. M. (2012). Rethinking community assembly through the lens of coexistence theory. Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics, 43, 227–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hubert, N. , Calcagno, V. , Etienne, R. S. , & Mouquet, N. (2015). Metacommunity speciation models and their implications for diversification theory. Ecology Letters, 18, 864–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert, N. , Kadarusman, Wibowo, A. , Busson, F. , Caruso, D. , Sulandari, S. , Nafiqoh, N. , Pouyaud, L. , Rüber, L. , Avarre, J.‐C. , Herder, F. , Hanner, R. , Keith, P. , & Hadiaty, R. (2015). DNA barcoding Indonesian freshwater fishes: Challenges and prospects. DNA Barcodes, 3, 144–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, G. E. (1957). Concluding remarks. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, 22, 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Huylebrouck, J. , Hadiaty, R. , & Herder, F. (2014). Two new species of viviparous halfbeaks (Atherinomorpha: Beloniformes: Zenarchopteridae) endemic to Sulawesi Tenggara, Indonesia Taxonomy & Systematics Introduction. The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 62, 200–209. [Google Scholar]

- Ibañez, C. , Belliard, J. , Hughes, R. M. , Irz, P. , Kamdem‐Toham, A. , Lamouroux, N. , Tedesco, P. A. , & Oberdorff, T. (2009). Convergence of temperate and tropical stream fish assemblages. Ecography, 32(4), 658–670. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D. A. , Peres‐Neto, P. R. , & Olden, J. D. (2001). What controls who is where in freshwater fish communities – The roles of biotic, abiotic, and spatial factors. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 58(1), 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Jamonneau, T. , Dahruddin, H. , Limmon, G. , Sukmono, T. , Busson, F. , Nurjirana, G. A. , Patikawa, J. , Wuniarto, E. , Sauri, S. , Nurhaman, U. , Wowor, D. , Steinke, D. , Keith, P. , & Hubert, N. (2024). Jump dispersal drives the relationship between micro‐ and macroevolutionary dynamics in the Sicydiinae (Gobiiformes: Oxudercidae) of Sundaland and Wallacea. Journal of Evolutionary Biology voae017. 10.1093/jeb/voae017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, A. , & Boseto, D. (2005). Schismatogobius vitiensis, a new freshwater goby (Teleostei: Gobiidae) from the Fiji Islands. Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters, 16, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, A. P. , & Jupiter, S. D. (2011). Spatial and seasonal patterns in freshwater ichthyofaunal communities of a tropical high Island in Fiji. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 91(3), 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, A. P. , Jupiter, S. D. , Qauqau, I. , & Atherton, J. (2010). The importance of ecosystem‐based management for conserving aquatic migratory pathways on tropical high islands: A case study from Fiji. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 20(2), 224–238. [Google Scholar]

- Karasiewicz, S. , Doledec, S. , & Lefebvre, S. (2017). Within outlying mean indexes: Refining the OMI analysis for the realized niche decomposition. PeerJ, 5, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith, P. , Delrieu‐Trottin, E. , Utama, I. V. , Sauri, S. , Busson, F. , Nurjirana, Wowor, D. , Dahruddin, H. , & Hubert, N. (2021). A new species of Schismatogobius (Teleostei: Gobiidae) from Sulawesi (Indonesia). Cybium: International . Journal of Ichthyology, 45(1), 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, P. , Hadiaty, R. K. , & Lord, C. (2012). A new species of Belobranchus (Teleostei: Gobioidei: Eleotridae) from Indonesia. Cybium: International . Journal of Ichthyology, 36(3), 479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, P. , Lord, C. , Darhuddin, H. , Limmon, G. , Sukmono, T. , Hadiaty, R. , & Hubert, N. (2017). Schismatogobius (Gobiidae) from Indonesia, with description of four new species. Cybium: International . Journal of Ichthyology, 41, 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, P. , Lord, C. , & Larson, H. (2017). Review of Schismatogobius (Gobiidae) from Papua New Guinea to Samoa, with description of seven new species. Cybium: International Journal of Ichthyology, 41, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, P. , Lord, C. , & Maeda, K. (2015). Indo‐Pacific Sicydiine gobies: Biodiversity, life traits and conservation. Société Française d'Ichtyologie. [Google Scholar]

- Kindt, R. (2020). Species accumulation curves with vegan, BiodiversityR and ggplot2. RPubs by RStudio. Available from: https://rpubs.com/Roeland-KINDT/694021 [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, M. A. , Rahel, F. J. , & Laughlin, D. C. (2021). Environmental filters of freshwater fish community assembly along elevation and latitudinal gradients. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 31(3), 470–485. [Google Scholar]

- Kottelat, M. (2013). The fishes of the inland waters of Southeast Asia: A catalogue and core bibliography of the fishes known to occur in freshwaters, mangroves and estuaries. The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 27, 1–663. [Google Scholar]

- Kottelat, M. , Whitten, T. , Katikasari, S. N. , & Wirjoatmodjo, S. (1993). Freshwater fishes of Western Indonesia and Sulawesi. Periplus Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, J. , Hadiaty, R. K. , & Herder, F. (2019). Nomorhamphus versicolor, a new species of blunt‐nosed halfbeak from a tributary of the Palu River, Sulawesi Tengah (Teleostei: Zenarchopteridae). Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lamba, T. , Ambeng, A. , & Andriani, I. (2023). Habitat and food habits of the endemic fish Oryzias eversi in Tana Toraja, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity, 24(9), 5137–5145. [Google Scholar]

- Le Pichon, C. , Tales, É. , Belliard, J. , & Torgersen, C. E. (2017). Spatially intensive sampling by electrofishing for assessing longitudinal discontinuities in fish distribution in a headwater stream. Fisheries Research, 185, 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, W. , Rukayah, S. , & Jamilatun, T. (2019). Introduced fish Oxyeleotris marmorata, Bleeker (1852): Population, exploitation rate and It's control in Sempor reservoir. Majalah Ilmiah Biologi Biosfera: A Scientific Journal, 36, 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Lévêque, C. , Oberdorff, T. , Paugy, D. , Stiassny, M. L. J. , & Tedesco, P. A. (2007). Global diversity of fish (Pisces) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia, 595(1), 545–567. [Google Scholar]

- Lohman, D. , de Bruyn, M. , Page, T. , von Rintelen, K. , Hall, R. , Ng, P. , Shih, H.‐T. , Carvalho, G. , & Rintelen, T. (2011). Biogeography of the indo‐Australian archipelago. Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics, 42, 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Lotze, H. , Lenihan, H. , Bourque, B. , Bradbury, R. , Cooke, R. , Kay, M. , Kidwell, S. , Kirby, M. , Peterson, C. , & Jackson, J. (2006). Depletion, degradation, and recovery potential of estuaries and coastal seas. Science, 312, 1806–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe‐McConnell, R. H. (1987). Ecological studies in tropical fish communities. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]