Tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) are associated with improved response in solid tumors treated with immune checkpoint blockade, but understanding of the prognostic and predictive value of TLS and the circumstances of their resolution is incomplete. Here we show that in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant immunotherapy, high intratumoral TLS density at the time of surgery is associated with pathologic response and improved relapse-free survival. In areas of tumor regression, we identify a noncanonical involuted morphology of TLS marked by dispersion of the B cell follicle, persistence of a T cell zone enriched for T cell-mature dendritic cell interactions and increased expression of T cell memory markers. Collectively, these data suggest that TLS can serve as both a prognostic and predictive marker of response to immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma and that late-stage TLS may support T cell memory formation after elimination of a viable tumor.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) are germinal center-like collections of T and B cells that arise in chronically inflamed non-lymphoid tissue. TLS may support antitumor adaptive and humoral immune responses in solid tumors treated with immune checkpoint blockade (ICB)1–8, but the prognostic and predictive value of TLS remain incompletely understood, particularly in cancers with limited response to immunotherapy. Furthermore, understanding of the life cycle of TLS remains incomplete. While TLS are thought to mature from loosely organized lymphoid aggregates to CD21+ primary follicle-like structures and reach full maturity as CD21+ CD23+ secondary follicle-like structures9–11, the circumstances of TLS resolution are not known.

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy involves the administration of ICB before surgery1,12–15. In addition to offering the potential to improve clinical outcomes for patients with potentially curable cancers, such an approach yields surgical specimens that provide a view of the effects of ICB on the human solid tumor microenvironment. In a phase I clinical trial (NCTO3299946) of neoadjuvant nivolumab and cabozantinib for locally advanced or borderline resectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common form of liver cancer2, we previously identified an association between TLS at the time of surgery and pathologic response to treatment. Here, we used a multiomic approach to evaluate the clinical and immunologic characteristics of TLS in an expanded cohort of HCC patients treated with neoadjuvant ICB and report the identification of a novel morphology of TLS consistent with a late-stage structure that may contribute to T cell memory formation after resolution of the antitumor immune response.

Results

Neoadjuvant ICB is associated with increased numbers of intratumoral TLS

To understand the clinical significance of TLS in patients with HCC treated with neoadjuvant ICB, we identified a treatment cohort (n = 19) who received surgical resection of locally advanced HCC after ICB-based therapy between October 2019 and January 2022 (Table 1). As TLS are known to occur in treatment-naive HCC9, we further identified a control cohort (n = 52) who received surgical resection for HCC without prior systemic therapy, whose tumors would serve as a surrogate for the pretreatment HCC tumor microenvironment. This cohort was similar to the neoadjuvant treatment cohort in age, sex, histologic grade and etiology.

Table 1 |.

Patient characteristics by treatment status

| Neoadjuvant (N=19) | Untreated (N=52) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery in years | ||

| Mean (s.d.) | 64 (±10) | 67 (±8.8) |

| Median (range) | 65 (41–79) | 67 (48–84) |

| Sex, no. (%) | ||

| Male | 11 (58) | 41 (79) |

| Female | 8 (42) | 11 (21) |

| Histologic grade, no. (%) | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 3 (16) | 8 (15) |

| Moderately differentiated | 13 (68) | 30 (58) |

| Well differentiated | 3 (16) | 14 (27) |

| Etiology, no. (%) | ||

| HBV | 3 (16) | 9 (17) |

| HCV | 7 (37) | 20 (38) |

| Dual HBV and HCV infection | 1 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatohepatitis | 2 (11) | 7 (13) |

| Alcohol use | 1 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Unknown | 5 (26) | 14 (27) |

| Neoadjuvant treatment, no. (%) | ||

| anti-PD1+Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI) | 14 (74) | |

| anti-PD1 | 3 (16) | |

| anti-PD1+anti-CTLA4 | 1 (5) | |

| anti-PD1+anti-CTLA4+TKI | 1 (5) | |

| Neoadjuvant treatment duration (days) | ||

| Mean (s.d.) | 91 (±33) | |

| Median (range) | 90 (44–200) | |

| Pathologic response, no. (%) | ||

| Major or complete pathologic response | 8 (42) | |

| Partial pathologic response | 8 (42) | |

| Non-response | 3 (16) | |

| Relapse, no. (%) | ||

| No | 10 (53) | |

| Yes | 9 (47) | |

| Death, no. (%) | ||

| No | 15 (79) | |

| Yes | 4 (21) | |

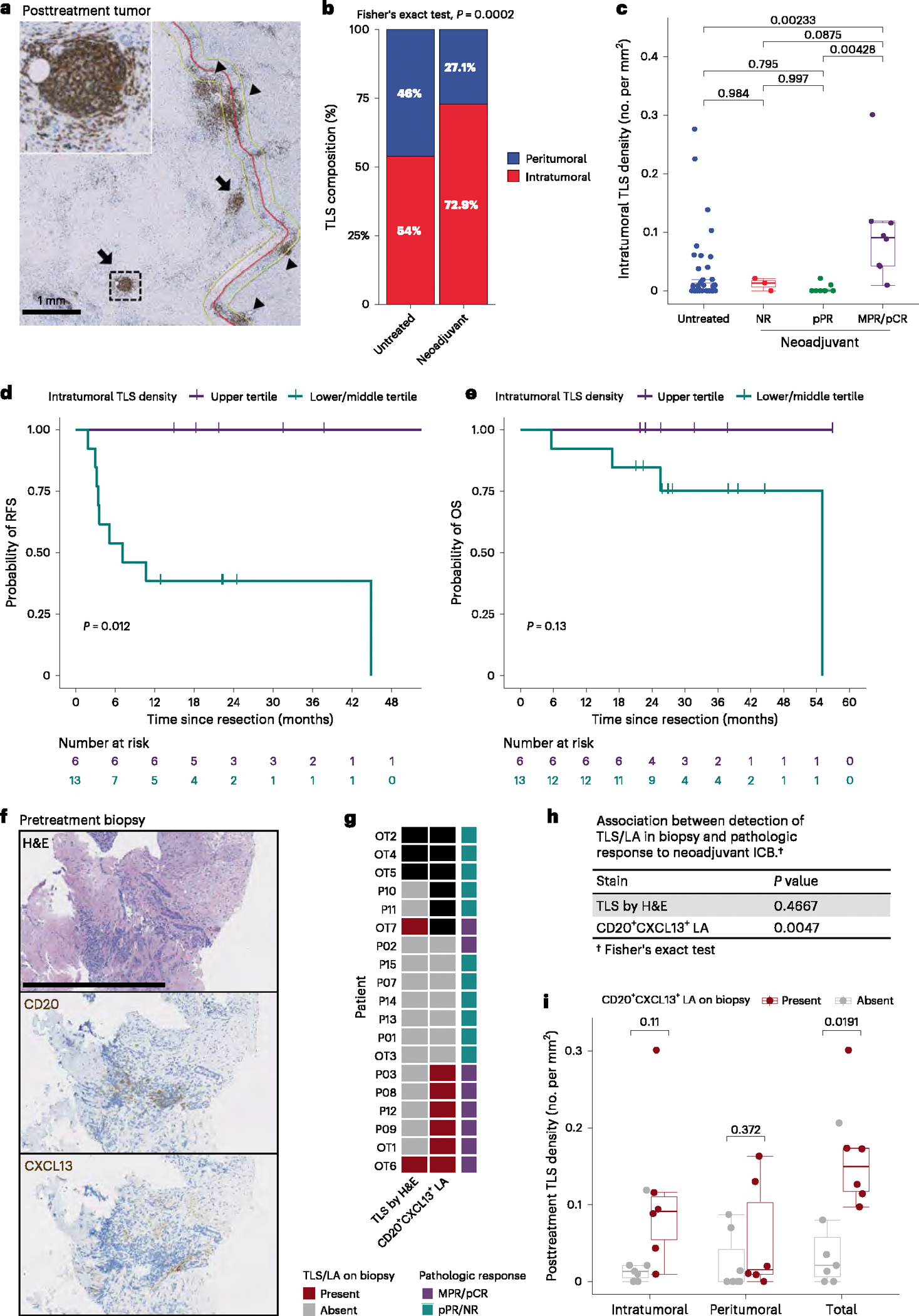

TLS density was quantified by CD20 staining of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tumor, with TLS defined as CD20+ lymphoid aggregates with diameter greater than 150 μm. TLS were categorized as peritumoral if they were found within 200 μm of the interface between normal adjacent parenchyma and tumor or intratumoral if they were found within residual viable tumor or tumor regression bed. TLS were observed in 12 of 19 (63.2%) treated tumors and 27 of 52 (51.9%) untreated HCC tumors, and neoadjuvant ICB was significantly associated with a higher proportion of intratumoral versus peritumoral TLS, with intratumoral TLS comprising 72.9% of TLS in neoadjuvant ICB-treated tumors compared with 54% in untreated controls (Fig. 1a,b and Extended Data Fig. 1a). Neoadjuvant ICB-treated tumors also displayed a trend toward higher median total and intratumoral TLS density compared with untreated controls, while no difference was observed in peritumoral TLS density between the two groups (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Single-marker immunohistochemistry was also used to quantify density of CD3+ and CD8+ T cells, CD20+ B cells and CD56+ natural killer cells, as well as tumor area positive for the B cell chemoattractant CXC chemokine ligand 13 (CXCL13), which is expressed by follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) within the germinal centers of TLS and tumor-specific CD8+ T cells16–19. No significant difference was observed in single marker expression between the untreated and neoadjuvant treated cohorts (Extended Data Fig.1c,d).

Fig. 1 |. TLS correlate with clinical benefit in HCC treated with neoadjuvant immunotherapy.

a, Representative images of FFPE HCC tumors stained with anti-CD20 antibody. Annotations indicate boundary between tumor/tumor regression bed and adjacent normal parenchyma (red), extension of boundary by 200 μm (yellow), intratumoral TLS (arrow) and peritumoral TLS (arrow head). The inset shows representative TLS at high magnification. Scale bar, 1 mm. b, A bar plot showing the overall composition of TLS by location in untreated controls and neoadjuvant ICB-treated tumors. c, Box-and-whisker plots showing intratumoral TLS density in untreated (n = 52) and neoadjuvant treated tumors, divided according to pathologic response (n = 19). d,e, Kaplan-Meier curves showing RFS (d) and OS (e) for patients in the neoadjuvant ICB-treated cohort in the highest tertile of intratumoral TLS density (purple) compared with the middle and lowest tertiles (green).f, Representative images of a FFPE fine needle biopsy from an HCC tumor before neoadjuvant immunotherapy. The images show staining with H&E, anti-CD20 and anti-CXCL13 antibodies. g, A heat map showing detection of TLS by H&E in pretreatment biopsies compared with detection of CD20+CXCL13+ lymphoid aggregates (LAs). The black squares indicate cases where samples were not available either due to lack of biopsy or insufficient tissue. The annotation bar indicates subsequent pathologic response to neoadjuvant ICB for each patient. h, The association between detection of TLS by H&E or CD20+CXCL13+ LA in pretreatment biopsy and subsequent pathologic response after neoadjuvant ICB. i, Box-and-whisker plots showing intratumoral, peritumoral and total TLS density after neoadjuvant ICB in patients with evaluable biopsy, divided according to the presence or absence of CD20+CXCL13+ LAs on pretreatment biopsy. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s honest significant difference test (c), Fisher’s exact test (b and h), log-rank test (d and e) and two-tailed t-test (i). For each box-and-whisker plot, the horizontal bar indicates the median, the upper and lower limits of the boxes the interquartile range and the ends of the whiskers 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Fig. 7 |. Comparison of mature TLS in areas of viable tumor and involuted TLS in the tumor regression bed.

Mature TLS in viable tumor display a highly organized germinal center (GC) with close interactions between GC B cells and CD21+ FDCs, a T cell zone characterized by CD4+ Tph cells in close proximity to MDCs and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells trafficking to the tumor via HEVs. In areas of tumor regression, an involuted TLS morphology is found that displays dissolution of the GC and persistence of Tph–DC interactions in the T cell zone, increased T cell memory marker expression and clonal expansion of cytotoxic and tissue resident memory CD8+ T cells. Created with Biorender.com.

Since previous infection with viral hepatitis is associated with chronic inflammation in the liver, we next investigated whether TLS were specifically associated with HCC due to viral hepatitis. In the treated cohort, 8/11 (72.7%) tumors of viral etiology had TLS, and in untreated tumors 20/30 (66.7%) tumors of viral etiology had TLS (Extended Data Fig. 1e). In the untreated cohort, tumors associated with viral hepatitis had significantly higher peritumoral TLS density than tumors of nonviral etiology and there was trend toward greater total TLS density in viral HCC (Extended Data Fig. 1f). Taken together, these data suggest that TLS in untreated HCC tumors are associated with prior viral hepatitis and are predominantly found outside the tumor, whereas neoadjuvant ICB favors a shift toward the formation of intratumoral TLS.

Intratumoral TLS associate with response and RFS

We next set out to determine whether there was an association between TLS density after neoadjuvant ICB and pathologic response to treatment20. Pathologic response designations were assigned according to percent residual viable tumor (RVT) in surgically resected tumors, with major pathologic response or complete response (MPR/pCR) defined as 0–10% RVT, partial pathologic response (pPR) as 10–90% and non-response (NR) as >90%. Eight (42.1%) patients had MPR/pCR, of which two had pCR and six had MPR; eight (42.1%) had a pPR, and three (15.8%) had NR. Intratumoral and total TLS density were significantly higher in tumors with MPR/pCR than in untreated tumors and tumors with pPR (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig.1g), and no difference in peritumoral TLS density was detected between tumors with MPR/pCR, pPR or NR, and untreated tumors (Extended Data Fig. 1h). Immune-related pathologic response criteria scoring for histopathologic features associated with immune mediated regression also identified a significant association between intratumoral TLS and MPR/pCR (Supplementary Table 1).

Having identified an association between pathologic response and high intratumoral TLS density, we next evaluated the prognostic value of high TLS density at the time of surgery. Survival analysis was restricted to the neoadjuvant ICB cohort since limited follow-up data were available for the control cohort. Patients with tumors in the upper tertile of intratumoral TLS density after neoadjuvant ICB had significantly longer relapse-free survival (RFS) after surgery compared with patients in the middle and lower tertiles (Fig.1d). At a median follow-up of 26.1 months for patients in the upper tertile of intratumoral TLS density and 26.9 months for patients in the middle and lower tertiles, median RFS was not reached in the upper tertile and 7.1 months in the middle and lower group. RFS at 30 months was 100% and 38.5% (95% confidence interval 19.3–76.5%), respectively. Overall survival (OS) was not significantly different between the two groups (Fig. 1e), but at 30 months there were no deaths in the group in the upper tertile of intratumoral TLS density. For patients in the upper tertile of total TLS density, a trend toward improved RFS was also observed when compared with the middle and lower tertiles, but OS was not significantly different (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b). No deaths were observed in the upper tertile of total TLS density and four deaths were observed in the middle and lower tertiles.

In contrast, no difference was observed in RFS or OS in patients in the upper tertile of peritumoral TLS density compared with the middle and lower tertiles (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d), suggesting that intratumoral TLS density is a stronger predictor of postsurgical prognosis after neoadjuvant ICB than peritumoral TLS density. Notably, patients with MPR/pCR had significantly longer RFS and a trend toward increased OS after surgery (Extended Data Fig. 2e,f). With the exception of OS, which was significantly lower in patients with a prior history of hepatitis B(HBV), no differences in RFS or OS were observed according to previous viral HBV or hepatitis C (HCV) infection (Extended Data Fig. 2g–j). Finally, using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) to quantify the strength of each parameter in predicting RFS or death after neoadjuvant ICB and surgical resection21, we found that the strongest predictors of RFS were intratumoral TLS density and pathologic response (Supplementary Table 2).

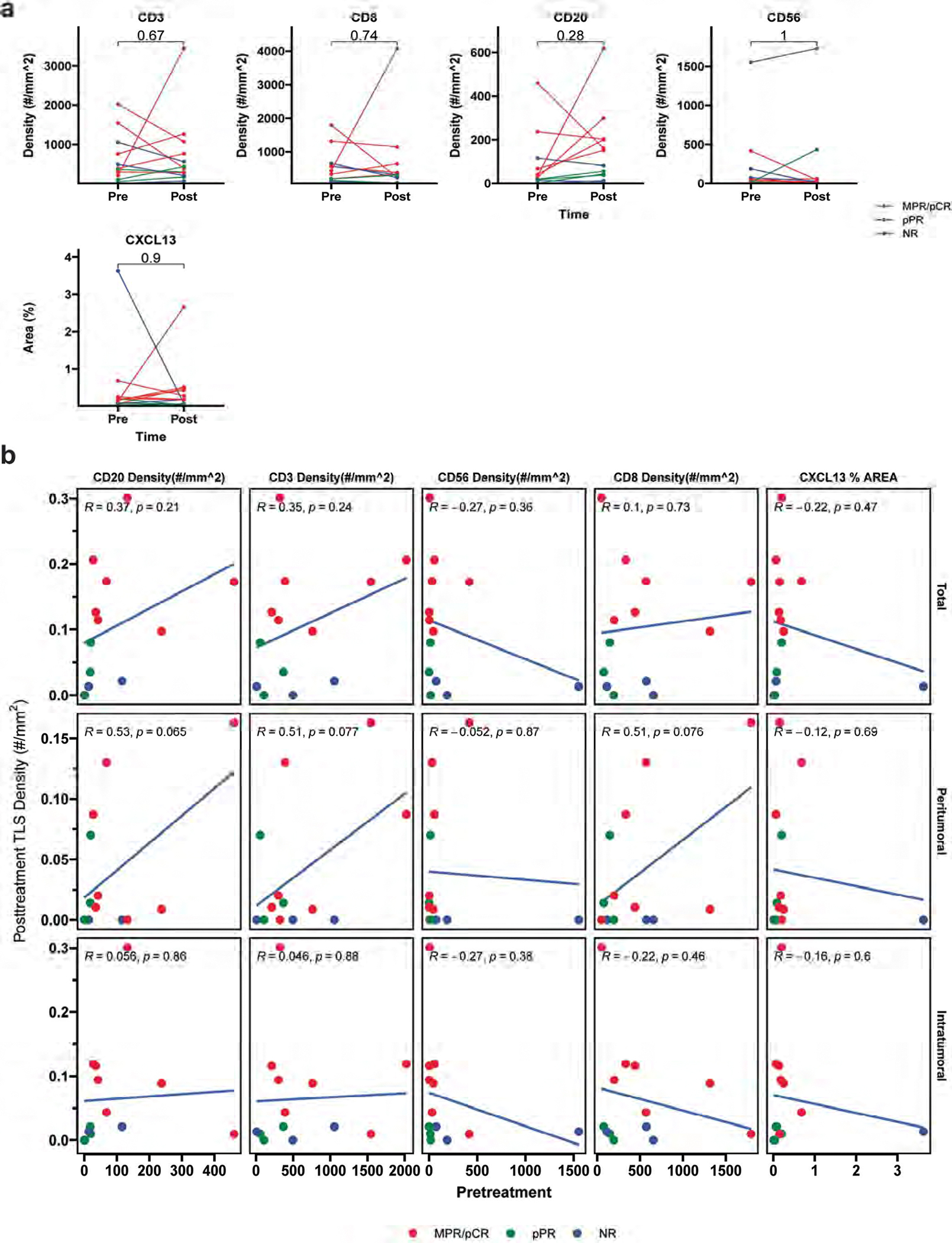

Pretreatment CD2O+ CXCL13+ aggregates are associated with response

We next examined the pretreatment biopsies of patients in the treatment cohort to determine whether TLS were present before neoadjuvant ICB and correlated with subsequent response to therapy. Sixteen of 19 (84.2%) patients had pretreatment fine needle biopsies available for review that had been stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and 13 biopsies had sufficient tissue for additional immunohistochemistry, which we used to detect CD3, CD8, CD20 and CXCL13. By H&E, TLS were only found in 2/16 (12.5%) biopsies. However, lymphocyte aggregates (LAs) positive for CD20 and CXCL13 (CD20+CXCL13+ LA) could be detected in 6/13 (46.2%) biopsies. CD20+CXCL13+ LA were significantly correlated with subsequent MPR/pCR, and tumors with CD20+CXCL13+ LA in the pretreatment biopsy had significantly higher total TLS density at the time of surgery (Fig. 1f–i). Detection of these aggregates in pretreatment biopsies was also associated with a trend toward longer RFS and OS (Extended Data Fig. 2k,I). In contrast, no significant difference was observed between pretreatment and posttreatment density of CD3, CD8, CD20 and CD56 cells or CXCL13 percentage area and/or pretreatment cell density and posttreatment total, peritumoral or intratumoral TLS density (Extended Data Fig. 3b). These data suggest that when TLS are not readily detected in pretreatment biopsies, combined staining for CD20 and CXCL13 rather than H&E or single-stain immunohistochemistry may be the best predictor of response to treatment and TLS density at the time of surgery.

TLS are associated with increased T and B cell activation

We next performed bulk RNA sequencing of FFPE surgical resection specimens to identify differences in gene expression between tumors with high and low TLS density. Tissue sections were collected from 14/19 tumors in the neoadjuvant treatment group, of which two samples were ultimately excluded due to poor sequencing quality. The resultant 12 samples were designated as TLS high (n = 5) or TLS low (n = 7) according to total TLS density relative to the mean total TLS density. On principal component analysis, the five TLS high tumors and one TLS low tumor clustered separately from the remaining six TLS low tumors (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Differential expression analysis using the R package DESeq2 identified 814 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), defined as having two times greater expression in the TLS high group compared with the TLS low group and a false discovery rate less than 0.05 (Extended Data Fig. 4b,c and Supplementary Table 1).

TLS high tumors demonstrated significant overexpression of multiple genes involved in T and B cell activation, cytokine production and antigen presentation, including CTLA4, IL7R, IL6, the B cell activating factor BAFF(TNFSF13B) and its receptors BAFF-R (TNFRSF13C) and TACI (TNFRSF13B), and the T cell-derived cytokine IL17C. TLS high tumors displayed significantly greater expression of CCL19, a chemokine involved in T cell and B cell migration to secondary lymphoid organs, and CXCR5, the receptor for the B cell chemoattractant CXCL13. TLS high tumors also demonstrated increased expression of multiple B cell related genes, including CD79A and CD79B, MS4A1 and FCRLA, which is highly expressed in germinal center B cells22. Immunoregulatory genes were also overexpressed in TLS high tumors, including IL10, IL17REL and the integrin αvβ8-mediated ITGB8, which mediates TGF-beta-1 activation on the surface of regulatory T cells (Tregs)23,24, and there was expression increased expression of GPR183, the gene encoding the germinal center regulatory protein EBI2; DOCK10, which regulates CD23 expression and sustains B cell lymphopoiesis in secondary lymphoid tissue25; and WDFY4, a mediator of dendritic cell cross presentation26.

Gene set enrichment analysis also identified enrichment in TLS high tumors of innate and adaptive immune-related gene sets, including the Hallmark pathways for allograft rejection, inflammatory response and complement activation; Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways for B and T cell receptor signaling, Fcγ and Fcε receptor mediated phagocytosis and natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity; and the Gene Ontology biological pathways for T and B cell activation (Extended Data Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table 2). In addition, there was a trend toward enrichment of the Gene Ontology biological pathways gene set for plasma cell differentiation in TLS high tumors. TLS high tumors also demonstrated increased expression of the 12-chemokine TLS gene signature, which has been associated with TLS in multiple solid tumors (Extended Data Fig. 4e)27. Taken together, these bulk gene expression data suggest multiple potential mechanisms of antitumor immunity, including increased T and B cell activation, local differentiation of plasma cells and antibody-mediated cell death via complement and antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity by natural killer (NK) cells.

Involuted TLS are present in areas of tumor regression

In neoadjuvant ICB-treated tumors, we further observed distinct TLS morphologies between areas of tumor regression and residual viable tumor. Whereas in residual viable tumor, the predominant TLS morphology was the canonical ‘mature’ stage of TLS, which is characterized by the presence of a CD20+ B cell germinal center with a dense CD21+ FDC network and distinct T and B cell zones9–11,28,29, in areas of tumor regression we detected a noncanonical TLS morphology characterized by dispersion of CD20+ B cells in a halo-like ring surrounding a central core of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2a). Immunostaining showed that TLS of the latter morphology, which we termed ‘involuted’, had low or absent expression of CD21 and the cell proliferation marker Ki67. Involuted TLS were observed within the regression bed of tumors in 7/19 patients, of which 5 had MPR and 2 had pCR. In the two tumors with pCR, we further detected dense clusters of multiple involuted TLS (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Serial sectioning further confirmed that this morphology was not an artifact of sectioning (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Given the dispersed appearance of B cells in these lymphoid aggregates, which resembled end-stage germinal centers previously described in murine lymph nodes30 and the fact that this morphology had been identified within areas of tumor regression, we hypothesized that this morphology may represent a terminal stage of the TLS life cycle.

Fig. 2 |. Involuted TLS are present in areas of tumor regression.

a, A representative FFPE neoadjuvant ICB-treated tumor stained with H&E showing divergent TLS morphologies (‘mature’ and ‘involuted’) in viable residual viable tumor and regression bed. The dotted line shows the boundary between residual viable tumor and regression bed. The blue arrows indicate mature TLS and red arrows indicate involuted TLS. Higher-magnification images of representative mature and involuted TLS are shown on the right with serial sections stained with dual immunohistochemistry for CD20 (magenta) and Ki67 (brown), CD3 (magenta) and CD21 (brown), and CD4 (magenta) and CD8 (brown). Scale bars, 2.5 mm for the low-magnification image and 250 μm for the high-magnification image. b, Imaging mass cytometry (IMC) workflow. c,d, Representative images of mature (c) and involuted (d) TLS obtained by IMC. The insets show higher-magnification images of CD8+ T cells trafficking through HEVs (c, far left), an extensive CD21+CD23+FDC network in the mature morphology (c, middle left) compared with scant CD21+ and CD23+ in the involuted morphology (d, middle left), close interactions between T cells and DCLAMP+ mature dendritic cells (MDCs) in the T cell zone adjacent to the germinal center (c, middle right), and high podoplanin expression in the germinal center of the mature TLS (c, far right). Scale bars, 100 μm. SMA, smooth muscle actin; CK, cytokeratin. e, A heat map showing the average IMC marker expression in annotated cell clusters identified from 90,344 single cells from 38 TLS (n = 20 mature and n = 18 involuted).f, The composition of mature and involuted TLS regions by cell type as a percentage of total cells per TLS.

To further evaluate differences between mature and involuted TLS, we developed a 38-marker imaging mass cytometry (IMC) panel to identify different T and B cell subsets, FDCs, dendritic cells, high endothelial venules (HEVs), macrophages, fibroblasts and tumor, as well as markers of T cell activation, exhaustion, costimulation and antigen presentation and cell proliferation (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Whole-slide staining was performed on FFPE tissue sections from the tumors of nine patients in the neoadjuvant ICB cohort, and 31 regions of interest were captured with 38 distinct TLS (n = 20 mature and 18 involuted) (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 5). Mature TLS displayed distinct B and T cell zones as well as HEV with a cuboidal morphology characteristically seen in the setting of increased inflammation31. CD8+ T cells were detected in transit through HEV (Fig. 2c, far left inset), and the B cell germinal centers of mature TLS displayed extensive networks of CD21+ and CD23+ FDC (Fig. 2c, middle left inset). Within the T cell zone mature dendritic cells (MDC), which we identified by high expression of CD11c and dendritic cell lysosomal associated membrane glycoprotein (DC-LAMP), were observed in close contact with CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2c, middle right inset), and dense stroma highly expressing the mucin-type transmembrane protein podoplanin (PDPN), which is upregulated in fibroblastic reticular cells in inflamed secondary lymphoid organs32, were also observed (Fig. 2c, far right inset33. In contrast, involuted TLS showed comparatively weak CD21 and CD23 expression, diminished PDPN expression and no detectable HEV with a cuboidal morphology. Within the central portion of involuted TLS, however, there was apparent persistence of the T cell zone (Fig. 2d).

Involuted TLS display persistence of the T cell zone

Using cell segmentation of IMC images, we next identified 61,371 single cells that were assigned to 16 distinct cell clusters (Fig. 2e,f and Extended Data Fig. 5c,d) and compared cell cluster density between mature and involuted TLS (Fig. 3 a and Extended Data Fig. 5e). Mature TLS had a significantly higher density of BCL6high B cells (B_BCL6high), which were consistent with a germinal center B cell population. This cluster demonstrated high expression of CD21, CD23, HLA-DR, a marker of antigen presentation, and the B cell activation marker CD86. A second B cell cluster (B_BCL6low), which was notable for lower expression of BCL6, HLA-DR and CD86, was identified on the periphery of the germinal center B cell population. This cluster was also found in higher density in mature TLS. No difference was observed in plasma cell density between the two morphologies, but surprisingly, a third B cell cluster (B_AID+), which had high expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), the enzyme that plays a key role in somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination in germinal center B cells, was found in higher density in involuted TLS. AID expression would be expected to be highest in mature TLS, but we note that in its cytoplasmic form, AID has a half-life of 18–20h (ref. 34), and thus the B_AID+ cluster may correspond to a memory B cells population that had recently undergone immunoglobulin class switching.

Fig. 3 |. Involuted TLS display persistence of the T cell zone.

a, Box-and-whisker plots showing cell cluster density in mature versus involuted TLS. For each box-and-whisker plot, the horizontal bar indicates the median, the upper and lower limits of the boxes the interquartile range, and the ends of the whiskers 1.5 times the interquartile range. b, Nearest neighbor analysis with rows indicating individual clusters in mature and involuted TLS and columns corresponding to first and second most common neighbors. c, Network analysis for cell clusters in mature and involuted TLS. The node size corresponds to the proportion of total cells for each TLS type occupied by each cluster. The edge length represents the shortest distance between cell clusters and the thickness corresponds to the number of measurements for each TLS type. d, Violin plots showing expression of CD45RO, CD25, CD69, CD137, LAG3, PD1 and TOX in the Tc and Tph clusters and CD11c, CCR7, DCLAMP, HLA-DR and CD86 in the MDC cluster, according to TLS morphology. Statistical significance was determined by pairwise two sample Wilcoxontest (a and d).

In the T cell compartment, we identified a single cytotoxic CD8+ T cell population (Tc) and two CD4+ T helper populations, a CD4+CXCR5−CXCR3+ T peripheral helper (Tph) cluster, which was found around the periphery of the B cell germinal center in mature TLS and centrally in involuted TLS, and a CD4+CXCR3− T helper (Th_CXCR3low) cluster. In location and marker expression, the Tph cluster was consistent with CD4+ Tph previously reported in human autoimmune disease, where Tph play a T follicular helper (Tfh)-like role in promoting pathogenic B cell responses in non-lymphoid tissue35–37. Density of the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell clusters was not significantly different between the two TLS morphologies. We further identified a CD4+CD57+ cluster (Th_CD57+) within the germinal center of mature TLS, a CD4+ subset type that has been reported to provide help to B cells and induce class switch recombination38; a cluster of CD4+ FOXP3+ Tregs (Th_FOXP3+); a cluster of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells defined by high expression of granzyme B (GZMB+ T cell); proliferating T and B cells defined by high expression of Ki67 (proliferating Tand B); a macrophage cluster with high expression ofCD68; a cluster of MDCs defined by the presence of high expression of DCLAMP and CCR7 (ref. 39); a HEV cluster defined by expression of the protein peripheral node addressin; and a tumor cluster with high expression of cytokeratin and PDL1. Mature TLS had a significantly higher density of proliferating T and B cells, HEV and tumor than involuted TLS. The density of MDCs was increased in involuted TLS.

As we had observed differences in clinical outcome according to TLS location, we also compared the cell density of different cell clusters in intratumoral and peritumoral TLS (Extended Data Fig. 5f). CXCR3low CD4+ T helper cells, CD57+ CD4+ T helper cells and HEVs were found in higher density in peritumoral mature TLS and macrophages were found in higher density in intratumoral TLS. In the remaining 12 clusters, no significance difference in cell density was detected, suggesting abroad similarity in morphology and cell composition between intratumoral and peritumoral mature TLS.

Neighborhood analysis further suggested that the primary differences in spatial relationships between mature and involuted TLS were in the spatial relationships of B cell populations (Fig. 3b). Whereas in mature TLS, BCL6high germinal center B cells were the first and second nearest neighbors for themselves, in involuted TLS the most frequent first neighbor of this cluster was the BCL6low cluster, consistent with dispersion of the B cell population in the latter morphology. In contrast, Tph were the most common non-self neighbors for GZMB+ T cells, MDCs, proliferating T cells and FOXP3+ Tregs in both mature and involuted TLS, suggesting that the spatial relationships between these clusters was preserved across the two morphologies. Network analysis also showed that the greatest differences in cell-to-cell distance and abundance between the two TLS morphologies was between two B cell clusters, B_BCL6high and B_BCL6low, while the spatial relationships between MDCs, Tph, FOXP3+ T cells, proliferating T and B cells, and GZMB+ T cells were similar (Fig. 3c).

Finally, we observed differences in protein expression between the Tc, Tph, MDC and tumor clusters between mature and involuted TLS that were suggestive of functional differences in between the two morphologies (Fig. 3d). The Tc and Tph clusters displayed increased expression of markers of antigen experience, including CD45RO, CD25, PD1 and TOX expression and the MDC cluster displayed significantly higher expression of CCR7, HLA-DR and CD86 in involuted TLS compared with mature TLS, consistent with ongoing antigen presentation by MDC in involuted TLS. Tumor expression of HLA-DR, which has been shown to correlate with T cell infiltration40, was significantly higher in mature compared with involuted TLS (Extended Data Fig. 5g). Taken together, these data suggest that involuted TLS may serve as sites of persistent antigen presentation and formation of memory T cell populations after elimination of viable tumor.

Immune repertoire overlap at TLS is greater for T cells than B cells

We next sought to characterize the T and B cell repertoires of TLS of these two morphologies. We microdissected 38 individual TLS (32 mature and 6 involuted) from seven treated tumors and performed bulk sequencing of the T cell receptor beta chain (TCR-β) and immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 6a and Supplementary Table 6). After filtering to remove repertoires with low counts, 35 TCR-β repertoires and 32 IGH repertoires were analyzed. Across all samples, a high degree of variability in repertoire size was found, with a mean total TCR-β clonotypes of 7,171 ± 8,472 (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Overall, singleton clonotypes comprised 68.7 ± 13.4% of the TCR-β repertoire in all TLS sampled. In mature TLS, singleton clonotypes comprised 72.02 ± 9.83% of the T cell repertoire, while in involuted TLS the singleton compartment constituted 48.98 ± 16.1%. TCR-β clonotypes present in all TLS from the same tumor were highly expanded, whereas singletons predominated among clonotypes found in only one TLS (Fig. 4b,c).

Fig. 4 |. Immune repertoire overlap at TLS is greater for T cells than B cells.

a, The workflow for T and B cell repertoire profiling of microdissected TLS (n = 30 mature and 5 involuted) from seven patients. b,d, Upset plots showing the overlap in unique TCR-β (b) and IGH (d) clonotypes across microdissected TLS from the same patient (P02). The bar plots in gray and annotation row indicate distinct groups of clonotypes shared between different TLS. The top stacked bar plots indicate the composition of groups according to clonal expansion. The bottom right stacked bar plots indicate the total unique TCR-β or IGH clonotypes identified at each TLS according to degree of clonal expansion. c,e, Alluvial plots tracking the top ten TCR-β (c) or IGH (e) clonotypes from TLS 1 of patient P02 across all TLS microdissected from the patient’s tumor. f, A box-and-whisker plot comparing the percentage of the TCR-β or IGH repertoire of each TLS that is shared with other TLS from the same tumor. g, A box-and-whisker plot comparing TCR-β clonality (as determined by normalized Shannon entropy) in microdissected mature and involuted TLS. Each point represents the TCR-β of an individual TLS. h, A violin plot comparing the number of IGH V gene substitutions in mature and involuted TLS. The individual data points (not shown) represent individual IGH sequences. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t-tests (f–h).

Across all microdissected TLS, the mean total number of IGH clonotypes was 922 ± 1,188 (Extended Data Fig. 6c), and singleton clonotypes comprised 95.3 ± 3.9% of the IGH repertoire of all TLS sampled. In mature TLS, singleton clonotypes comprised 95.7 ± 4.0% of the IGH repertoire, while in involuted TLS, the singleton compartment constituted 93.4 ± 3.1%. IGH repertoire sharing was considerably lower across TLS (Fig. 4d,e). Among TLS microdissected from the same tumor, a mean of 32.3 ± 12.3% unique TCR-β clonotypes and 6.7 ± 5.6% unique IGH clonotypes detected at each TLS were also present in other TLS from the same tumor, suggestive of a high degree of sharing of expanded T cell clonotypes and highly distinct B cell germinal center reactions at individual TLS. No significant difference in TCR-β or IGH repertoire sharing was detected according to morphology or location (Extended Data Fig. 6d).

In three patients(P12,OT1 and OT6) in which mature and involuted TLS were present in the same tissue block, TCR-β clonality was significantly increased in mature TLS compared with involuted TLS(Fig.4g), although this difference was primarily driven by a single patient OT6 (Extended Data Fig. 6e). No difference was observed in IGH clonality (Extended Data Fig. 6f), but the IGH repertoire of involuted TLS did demonstrate a significantly higher number of V gene substitutions, a surrogate for somatic hypermutation (Fig. 4h and Extended Data Fig. 6 g). Taken together, these data suggest that B cell populations in involuted TLS have undergone greater antigen-driven positive selection, consistent with the hypothesis that these are late-stage structures.

T and B cell repertoire sharing across TLS, blood and lymph nodes

To understand the extent of immune repertoire trafficking between TLS and nontumor compartments, we performed TCR-β sequencing of pre- and posttreatment peripheral blood obtained from five of the seven patients from whose tumors TLS were microdissected and TCR-β/IGH sequencing on tumor draining lymph nodes resected at the time of surgery from two of the seven patients (removal of tumor draining lymph nodes is not standard of care in surgical resection of HCC and thus additional samples were not available). A mean of 44.9 ± 8.4% unique TCR-β clonotypes identified at TLS were also present in posttreatment peripheral blood and a similar degree of T cell repertoire overlap was observed between TLS and pretreatment peripheral blood (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). Thirteen unique TCR-β clonotypes were significantly expanded in posttreatment peripheral blood compared with the pretreatment time point, of which nine were detected in microdissected TLS(Supplementary Table 7). In the two patients with tumor draining lymph nodes available for comparison, TCR-β and IGH sequencing were also performed (Extended Data Fig. 7c–f). A mean of 59.9 ± 6.0% unique TCR-β clonotypes in TLS were also detected in the patient’s tumor draining lymph nodes, with a lower proportion of the T cell repertoire being shared in mature TLS. A mean of 17.3 ± 15.2% unique IGH were shared, with a greater degree of B cell repertoire sharing in involuted TLS. Overall, these data suggest greater trafficking of T cells among TLS, peripheral blood and tumor draining lymph nodes as compared with B cells.

Top expanded T cell clonotypes in TLS are GZMK+ and GZMB+ CD8+ T cells

To recover the transcriptional phenotype of T and B cell populations identified in TLS, we performed single-cell RNA, T cell receptor (TCR) and B cell receptor (BCR) sequencing of posttreatment peripheral blood for all seven patients from whose tumors TLS were microdissected and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from one of the seven patients(OT6).After preprocessing and filtering to remove low-quality sequencing data,28,694 single cells were identified in the peripheral blood and 620 in the TILs. Cells were annotated using a reference dataset and TCR-ß and IGH sequences were compared against TCR-β and IGH identified in microdissected TLS. Matching of TCR-β between microdissection and single-cell datasets was successful, but no common IGH were found to be present in both datasets and thus all single cells identified as B cells were excluded from further analysis.

The resultant 23,172 single T cells from peripheral blood (Fig.5a–c and Extended Data Fig.8a,b) and 562 from TILs (Extended Data Fig. 9a–c) Were clustered into 16 distinct T cell subsets according to genes expression. In total, 19,546 of 23,172 (84.3%) single cells in the peripheral blood dataset and 346 of 562 (61.6%) cells in the TIL had a partial or completely sequenced TCR-αβ chain identified by single-cell TCR sequencing, of which 15,016 and 256, respectively, were unique clonotypes (Supplementary Table 8).

Fig. 5 |. GZMK+ and GZMB+CD8+ T cells are highly represented in TLS.

a, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) of 23,172 T cells identified by single-cell RNA/TCR/BCR sequencing of CD3+CD19+ FACS-sorted peripheral blood from patients with HCC treated with neoadjuvant ICB (n = 7). b, A bar plot showing the number of single cells per cluster. c, Violin plots showing expression of a subset of specific marker genes across clusters. d,e, UMAPs showing clonality of single cells with an associated T cell receptor sequence (d) and single cells with a TCR-β identified in microdissected TLS (e). f, A bar plot showing the proportion of each single-cell cluster identified in TLS. g, The inferred transcriptional phenotype of TCR-β clonotypes in microdissected TLS with a matching TCR-β in single-cell sequencing of posttreatment peripheral blood (n = 7) or TILs (n = 1). h, The inferred transcriptional phenotype of TCR-β clonotypes in mature and resolving TLS of patient OT6.

The CD8 TEM_GZMK cluster was notable for the high expression of genes associated with cytotoxicity, including granzyme K (GZMK) and the chemokine ligand CCL5 (CCL5), and low expression of granulysin (GNLY) (Extended Data Fig. 8c). The CD8 TEM_GZMB cluster demonstrated hallmarks of cytotoxicity, including elevated expression of granzyme B (GZMB) and granzyme H (GZMH), as well as elevated expression of perforin (PRF1) and GNLY, and low expression of GZMK (Extended Data Fig. 8d).These two transcriptional phenotypes were consistent with progenitor exhausted and terminally differentiated CD8 T cell states, respectively, which have been identified in the peripheral blood and tumors of patients treated with ICB 41. Notably, in the TILs, GZMK and GZMB expressing CD8 clusters also showed increased expression of multiple T cell exhaustion markers, including PDCD1, CTLA4, LAG3, TIGIT and TOX. NKG7 and CCL5, which are associated with cytotoxic CD8 T cells, were also increased in both clusters, with higher expression in the GZMB high cluster (Extended Data Fig. 9e–g). Both clusters in the TIL had elevated expression of CXCL13(refs. 17,18). Notably, no CD4+ T cell cluster was detected with a transcriptional phenotype consistent with a CD4+ Tfh population, which we defined as CXCR5highCXCR3highICOShigh. However, we did detect a CD4+ T cell cluster consistent with the Tph cluster identified by IMC. In the peripheral blood, cells were assigned to this cluster if they were CXCR5lowCXCR3high and had elevated expression of CTLA4, TIGIT and TOX (Extended Data Fig. 8e). Cells belonging to this cluster in the single-cell TIL demonstrated increased expression of CXCL13, ICOS, PD1, MAF and TOX and high expression of multiple exhaustion markers including CTLA4, LAG3, TIGIT, HAVCR2 and TNFRSF18 (GITR) (Extended Data Fig. 9h).

A total of 6,349/19,546 (32.5%) of single cells with a TCR-β in the peripheral T cell dataset and 273/346 (77.7%) single cells with a TCR-β in the TILs were identified in at least one TLS (Supplementary Table 8). TCR-β identified in TLS were detected in all clusters identified in the peripheral blood and TILs. The peripheral blood T cell clusters most strongly associated with TLS were CD4 TEM_GZMB, CD8 TEM_GZMK and CD8TEM_GZMB (Fig.5e,f and Supplementary Table 10), suggesting that TLS support the traffic of effector memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations from the peripheral blood to tumor. No TIL cluster was significantly correlated with TLS but the Treg cluster was negatively correlated with TLS (Extended Data Fig. 10b and Supplementary Table 10). While the proportion of TCR-β in TLS that were identified by single-cell sequencing was low overall (2,908/135,909 unique clonotypes or 2.1%), among highly expanded clonotypes matching was more successful, with 369/1359 (27.2%) of the top 1% of TCR-β found identified in TLS being identified in the single-cell data and 63/137 (46%) of the top 0.1% (Supplementary Table 11). Thus, this approach, while providing a limited view of singleton TCR-β in TLS, was capable of recovering the transcriptional phenotype of expanded T cell populations present in TLS.

Across all seven patients, the majority of T cells identified by matching of the TCR-β were GZMK and GZMB expressing CD8 T effector memory cells, but we also observed CD4 TEM_GZMK, CD4 CTL and CD4 Tph clusters among the putative phenotypes of T cells trafficking through TLS (Fig. 5g). Notably, in the involuted TLS from the tumor of patient OT6, where we had previously noted a significant increase in clonality relative to mature TLS, clonal expansion was greatest in the CD8 TEM_GZMK, CD8 TEM_GZMB and CD8 TRM clusters (Fig. 5h and Extended Data Fig. 10c). Overall, these data suggest that highly expanded T cell populations in TLS have aCD8+ T cell effector memory phenotype and may undergo clonal expansion and repertoire contraction in concert with expansion of resident memory populations in areas of tumor regression.

Involuted TLS are present in regression beds of other tumor types

Finally, we examined the resected tumors of three patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) and two patients with Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) to determine if the involuted TLS morphology identified in neoadjuvant ICB-treated HCC tumors was also present in other immunotherapy-treated solid tumors. Two patients with NSCLC had received combination anti-PD-1/anti-CTLA-4 (ref. 42) and one received anti-PD-1 plus chemotherapy, and both patients with MCC received neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 (ref. 43). All five tumors had pCR at the time of surgery, and TLS were present in all tumors. In two of three NSCLC tumors, involuted TLS were detected within areas of tumor regression and mature TLS were found primarily at the margin between regression bed and adjacent normal parenchyma (Fig. 6a,b). Compared with mature TLS, involuted TLS in the two NSCLC tumors had significantly lower density of CD20−, CD3−, CD4− and CD21-positive cells compared with mature TLS. No significant difference was detected in density ofCD8+ T cells or DCLAMP+ MDCs between the two morphologies. Involuted TLS were also detected within the regression bed of one of the two MCC tumors (Fig. 6c). Taken together, these data suggest that the TLS morphology here identified may represent a common late-stage morphology occurring in the tumor regression bed of ICB-treated solid tumors.

Fig. 6 |. Involuted TLS are found in regression beds of other tumors types treated with neoadjuvant ICB.

a, A representative image of a FFPE tumor from a patient with lung adenocarcinoma who had pCR after neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 plus anti-CTLA4 stained with anti-CD20 antibody (left) and high magnification images (right) of staining for CD20, CD3 (magenta) and CD21 (brown), CD4 (magenta) and CD8 (brown), DCLAMP and HLA-DR. The dotted line indicates the boundary between tumor regression bed and adjacent normal tissue or lymph node. Mature TLS (blue arrows) are found predominantly within the adjacent normal tissue at the interface with the tumor regression bed, and involuted TLS (red arrows) are found within regression bed. Scale bars, 2.5 mm for the low-magnification image and 500 μm for high-magnification images. b, Box-and-whisker plots showing cell density for CD20−, CD21−, CD3−, CD4−, CD8−, DCLAMP- and HLA-DR-positive cells in mature (n = 30) and involuted (n = 22) TLS in two lung adenocarcinoma tumors where involuted TLS were identified. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t-tests. c, A multiplex immunofluorescence image showing CD3 (red) and CD79a (green) staining in involuted TLS identified in the tumor regression bed of a MCC tumor with pCR after neoadjuvant anti-PD-1. Scale bar, 600 μm.

Discussion

TLS are associated with favorable outcomes in treatment-naive and immunotherapy-treated solid tumors 3–6, but understanding of their clinical significance and contribution to antitumor immunity remains incomplete. Consistent with previous studies of TLS in early stage treatment-naive HCC9 and other solid tumor types treated with ICB, here we report an association between intratumoral TLS and improved prognosis in HCC treated with neoadjuvant ICB. We further identify CD20+CXCL13+ LAs as a potential predictor of response to immunotherapy. TLS in treatment-naive tumors have previously been associated with improved responses to ICB6,7, but routine detection of TLS in fine needle aspirates remains challenging, as was seen in our cohort. Thus CD20+ CXCL13+ LAs may serve as a surrogate for TLS detection in circumstances where the quality or quantity of pretreatment biopsy is limited.

In addition, we identify in neoadjuvant ICB-treated HCC tumors an involuted TLS morphology with features consistent with a terminal stage of the TLS life cycle. The presence of a dispersed B cell population in association with an intact T cell zone enriched for DCLAMP+CCR7+HLA-DR+ MDCs and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells suggests that TLS dissolution may be dyssynchronous, with disorganization of the B cell zone preceding disruption of the T cell zone. Immune repertoire sequencing data from patient OT6 further suggests that these morphologic changes are associated with expansion of cytotoxic and tissue resident memory-like CD8+ T cell clonotypes, suggesting that late-stage TLS may support the contraction and memory phase of the intratumoral adaptive immune response (Fig. 7). Importantly, we also find that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at involuted TLS highly express the transcription factor TOX, a critical regulator of both tumor-specific T cell exhaustion programs and T cell persistence44.

We note several limitations in the present study. While these data suggest that TLS may be a prognostic and predictive biomarker for patients with HCC receiving ICB, they require validation in larger cohorts. Given the heterogeneity in treatment of the neoadjuvant cohort, we are unable to identify the differential contributions of anti-PD1, anti-CTLA4 and antiangiogenic therapies to TLS formation and resolution. In addition, our conclusion that involuted TLS represent a late-stage form is inferred rather than directly observed, and thus we cannot fully exclude the possibility that these structures could represent immature rather than end-stage TLS. Additional studies are required to define the life cycle of TLS and the immunological consequences of TLS resolution in the context of tumor regression. Cell segmentation of densely clustered cell populations remains a technical challenge for IMC analyses, and thus future advances in cell segmentation may lead to refinement in the quantitation of individual cell types in mature and involuted TLS examined in this study. Finally, the transcriptional phenotype of T cells infiltrating TLS was derived by comparison of TCR-β sequences identified by microdissection against matched single-cell sequencing data. Nevertheless, we demonstrate that TLS morphology varies with the presence or absence of viable tumor, supporting the hypothesis that the tumor is the inflammatory stimulus driving TLS formation, and we identify a noncanonical TLS morphology that may be a common pathologic endpoint in the TLS life cycle, which may support the formation of intratumoral T cell memory after elimination of tumor.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-024-01992-w.

Methods

Study design

The aim of this study was to characterize TLS in patients with HCC treated with neoadjuvant ICB-based therapy before surgical resection of the primary tumors. To understand the clinical significance of TLS, we analyzed TLS density in treated patients and untreated controls and correlated TLS density with pathologic response and postsurgical clinical outcomes. We evaluated specimens collected by pretreatment biopsy to determine whether detection of TLS, or a surrogate, before neoadjuvant ICB was associated with response to treatment. We performed bulk RNA sequencing of tumors with high and low TLS density after neoadjuvant treatment to understand the gene expression programs associated with high TLS density. We then characterized the morphological and functional properties of two morphologies of TLS observed in viable tumor and tumor regression bed using IMC, bulk immune TCR-β and IGH sequencing of microdissected TLS, and matched single-cell RNA, TCR and BCR sequencing of peripheral blood and TILs. Finally, observations about TLS in HCC tumors were corroborated in tumors of patients with lung adenocarcinoma and MCC treated with neoadjuvant ICB.

Patient identification and data collection

Patients with HCC in the neoadjuvant treatment cohort were identified for inclusion in this study if they received surgical resection for locally advanced, nonmetastatic HCC after ICB-based therapy between 1 October 2019 and 31 January 2022 at the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center. Patients were included in the untreated control cohort if they underwent surgical resection for HCC without prior systemic treatment between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2023. Retrospective chart review was performed to collect clinical data from the electronic medical record regarding age at surgery, sex, date of resection, HCC etiology and histologic grade of tumor. Additional data regarding neoadjuvant treatment, RFS and OS were collected for the neoadjuvant cohort and absence of prior systemic treatment was confirmed for the control cohort. For both cohorts, histologic grade was based on pathologic assessment at the time of resection if there was discordance with grade reported for pretreatment biopsy. Patients in both cohorts were excluded from analysis if there was evidence of active HBV (defined by a positive HBsAg or detectable HBV DNA) before surgery. Patients were excluded from the control group if the etiology of their HCC was not represented in the treatment group (for example, hepatic adenoma and hereditary hemochromatosis). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board (IRB00149350, IRB00138853, NA_00085595). Informed consent or waiver of consent was obtained from all patients. Patients with HCC in the neoadjuvant cohort identified with the letter P were accrued as participants in the phase I clinical trial NCT03299946 (ref. 2).

Histopathological assessment of TLS density and pathological response

Tumors in the treatment cohort were evaluated for pathologic response to neoadjuvant ICB as described in Results. The evaluation of pathologic response was performed by a hepatopathologist (R.A.A.). To determine TLS density, FFPE tumors were sectioned, mounted on glass slides and stained with anti-CD20 antibody as described below. Whole-slide images were obtained at 0.49 μm per pixel using the Hamamatsu NanoZoomer. The presence of CD20 positivity was determined by digital image analysis software (HALO v3.0.311, Indica Labs), with TLS defined as CD20-positive cell aggregates greater than 150 μm in diameter located among tumor cells or at the invasive margin in areas of viable and nonviable tumor. TLS density was determined by calculating the number of TLS per mm2 of viable and nonviable tumors. TLS were classified as peritumoral if they were found within 200 μm of the interface between normal adjacent parenchyma and tumor and intratumoral if they were found within the tumor or tumor regression bed.

Survival analyses

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate RFS and OS. RFS was defined as the time from surgical resection to radiographic relapse. OS was defined as the time from surgical resection to death from any cause. If a patient was not known to have had either event, RFS and OS were censored at the last date of known healthcare contact. RFS and OS analyses were limited to patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy and were not performed in the untreated controls due to limited follow-up in this cohort. Survival analyses using the Kaplan–Meier method were performed using the R package survminer. For BIC analysis, a linear regression model was used to evaluate the effect of each marker, dichotomized by the mean, as a predictor of each distance measure. For each binary outcome, logistic regression was employed, with each marker treated as continuous. A meaningful difference in BIC between the two models is 2 at a minimum, and a difference between 5 and 10 and above 10 is considered to be strong and very strong, respectively45. BIC analysis was performed using the R package stats.

Immunohistochemistry

Automated single and dual staining was performed on the Leica Bond RX (Leica Biosystems). Single staining for CD20 was employed for determination of TLS density. Dual staining for CD3 and CD21, CD8 and CD4, Ki67 and CD20 was performed before laser capture microdissection of TLS. Slides were baked and dewaxed online followed by antigen retrieval for 20 min at 100 °C. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked using peroxidase block (Refine Kit) followed by protein block (X090930–2, Agilent Technologies). Primary antibodies were applied at room temperature. Detection was performed using the Bond Polymer Refine Kit (DS9800, Leica Biosystems). For dual staining, a second round of antigen retrieval was performed for 20 min at 95 °C, followed by application of a second primary antibody. Detection of the second primary antibody was performed using the Bond Polymer Red Refine Kit(DS9390, Leica Biosystems). Slides were counterstained, baked and coverslipped using Ecomount (5082832, Biocare Medical). Antigen retrieval buffers and concentrations of all antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table 12. Antibodies were diluted to appropriate working concentration using Antibody Diluent (S302283–2, Agilent Technologies).

Bulk RNA sequencing of FFPE tumor

RNA was extracted from FFPE tumors from the treatment cohort and sequenced using the commercial platform ImmunoID NeXT with 200 million paired-end reads (150 base pairs). Reads were aligned in accordance with the Personalis Cancer RNA pipeline and transcript per million values were extracted46. Bulk RNA sequencing was performed on 14 tumors in two batches. No batch correction was applied due to lack of clear batch-to-batch differences by principal component analysis. Two samples were excluded due to poor sequencing depth, defined as the median of the log2-transformed count data being equal to 0. The remaining 12 samples were filtered to include only genes for which the sum of raw counts across all samples was greater than 1. Variance stabilizing transformation was performed on the resultant data and DEGs were identified using DESeq2 (ref. 47). Genes with an adjusted P value of <0.05, and a minimum log2 fold change of 1 were considered differentially expressed. Pathway analysis was performed using the R package fsgsea to identify biologically enriched pathways from the MSigDB hallmark gene sets48,49. For pathway analyses, adjusted P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

IMC staining and acquisition

IMC staining was done as previously described2,50. FFPE resected liver tissue sections were baked, deparaffinized in xylene and then rehydrated in an alcohol gradient. Slides were incubated in Antigen Retrieval Agent pH 9 (Agilent, PN S2367) at 96 °C for 1 h then blocked with 3% BSA in PBS for 45 min at room temperature followed by overnight staining at 4 °C with the antibody cocktail. Antibodies, metal isotopes and their titrations are listed in Supplementary Table 4. Images were acquired using a Hyperion Imaging System (Standard BioTools) at the Johns Hopkins Mass Cytometry Facility. Upon image acquisition, representative images were visualized and generated through the MCD Viewer (Standard BioTools).

IMC data analysis

Images were segmented into a single-cell dataset using the publicly available software pipeline based on CellProfiler, ilastik and HistoCAT51–54. Since multiple images contained more than one TLS, images were subset for distinct TLS regions by manual gating using FlowJo v10.9.0 software (BDLife Sciences), which identified the xy coordinates of cells belonging to distinct lymphoid aggregates. This resulted in 38 unique TLS matching either the mature (n = 20) or involuted morphology (n = 18). The resulting 61,371 single cells were clustered using FlowSOM55 into metaclusters, which were manually annotated into final cell types. The density of each cell type was determined by calculating the number of cells per unit area as determined by ImageJ v 1.53 (ref.56). For network visualization, the mean distance between each cell type was computed and visualized using the R package qgraph57. Neighborhood analysis was performed by using data generated by HistoCAT summarizing the top neighboring cell types for every cell type.

Laser capture microdissection and TCR-β/IGH sequencing of TLS

Serial tissue sections 10–14 μm in thickness were obtained from FFPE tumor tissue blocks and mounted on UV-activated polyethylene naphthalate (PEN) membrane glass slides (Applied Biosystems, LCM0522) with additional 4 μm tissue sections cut every 150 μm for staining with H&E and dual IHC for CD3/CD21, CD8/CD4 and Ki67/CD20, as described above. Stained sections were scanned at 20× objective equivalent (0.49 μm per pixel) on a digital slidescanner (Hamamatsu Nanozoomer) in advance of microdissection and annotated using NDP.view2 viewing software to identify areas for microdissection. On the day of microdissection, unstained tissue sections mounted on PEN membrane slides were deparaffinized using xylene and graded alcohol washes and stained with H&E. Laser capture microdissection of individual TLS was performed on the LMD 7000 system (Leica) and genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen). DNA concentrations were quantified with a Qubit 4 Fluorometer using the Qubit dsDNA high sensitivity assay (Invitrogen). Sequencing of the TCR-β and IGH CDR3 regions was performed using the immunoSEQ platform (Adaptive Biotechnologies)58,59. TCR-β and IGH repertoire data were downloaded from the Adaptive ImmunoSEQ analyzer web interface after filtering to remove nonproductive reads. After exclusion of repertoires with fewer than 500 TCR-β clones and 50 IGH clones, subsequent analysis was performed using the R package immunarch60. Clonality was calculated as 1Shannon’s equitability with clonality values ranging from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating equal representation of all clones within a repertoire and 1 being a repertoire consisting of only one clone61. To compare clonality across multiple TLS from the same tumor, we used the median clonality of 1,000 iterations of downsampling to the number of productive CDR3 sequences in the smallest TCR-β or IGH repertoire for that patient62.

Peripheral blood and fresh tumor collection and processing

Processing of peripheral blood and cryopreservation was completed as previously described2. Fresh tumor tissue was diced with a sterile scalpel and dissociated in 0.1% collagenase in RPMI 1640 for 60 min at 37 °C using the gentle MACS OctoDissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in ACK Lysing buffer (Quality Biological, 118–156-721) and incubated at room temperature for 5 min before centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 10 min. Cells were resuspended in PBS, counted using a manual hematocytometer and cryopreserved in 10% dimethylsulfoxide/AIM-V freezing media.

Single-cell RNA/TCR/BCR sequencing

For all seven patients whose tumors TLS were microdissected, single-cell sequencing was obtained for peripheral blood T and B cells isolated by fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS). For six patients, the peripheral blood sample was obtained after completion of neoadjuvant ICB and before surgical resection, and for one of the patients, the peripheral blood sample was drawn 4 weeks after resection. In the latter patient, single-cell sequencing was also performed on isolated tumor infiltrating T and B cells. For single-cell sequencing, all samples were thawed and washed with prewarmed RPMI with 10% FBS, and cells were resuspended with 0.04% BSA in PBS and stained with a viability marker (Zombie NIR, BioLegend) and Fc block (BioLegend, 422302) for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. Cells were then stained with antibodies against CD3 (FITC, clone HIT3a), for 20 min on ice and CD19 (PE/dazzle, clone SJ25C1) (Supplementary Table 13). After staining, viable CD3+ and CD19+ cells were sorted into 0.04% BSA in PBS using a BD FACS Aria II Cell Sorter at a 4:1 ratio. Sorted cells were counted and resuspended at a concentration of 1,000 cells per μl, and single-cell library preparations for gene expression and V(D) J were performed using the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 5′ GEM Kit v2 (10x Genomics) and Chromium Single Cell V(D)J Amplification Kit (human TCR) (10x Genomics). Cells were partitioned into nanoliter-scale gel beads in-emulsion and barcoded. Complementary DNA synthesis and amplification were performed before the samples were split for the gene expression and for V(D)J libraries. Single-cell libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq instrument using 2×150 bp paired-end sequencing. The 5′ VDJ libraries were sequenced to a depth of 5,000 reads per cell and the 5′ DGE libraries were sequenced to a depth of 50,000 reads per cell.

Single-cell data processing, clustering and integration

Cell Ranger v6.1.2 was used to demultiplex FASTQ reads, perform sequence alignment to the GRCh38 transcriptome and extract unique molecular identifier barcodes. Single-cell gene expression matrices were analyzed using the R package Seurat v4.1.1 as a single Seurat object. Cells were filtered to include only cells with less than 25% mitochondrial RNA content and between 200 and 4,000 genes detected. For single-cell VDJ sequencing, only cells with full-length sequences were retained. The Seurat function SCTransform was used to normalize raw count data to a Gamma-Poisson generalized linear model, perform variance stabilization, identify highly variable features and scale features63,64. Cells were projected into their first 50 principal components using the RunPCA function and further reduced into a two-dimensional visualization space using RunUMAP. Initial cell cluster identification was performed using the function FindClusters at a resolution of 0.7. Initial cell type assignment was performed by reference mapping to an annotated human peripheral blood mononuclear cell dataset in the R package Azimuth65. Final cluster identities were manually assigned by identification of DEGs using the MAST hurdle model as implemented in the FindAllMarkers function with a log fold change threshold of 0.25 and minimum fractional expression threshold of 0.25 (ref. 66). Seven distinct clusters of CD4 T cells were identified: a naive CD4 T cell cluster (CD4 naive), expressing high levels of CCR7 and LEF1; a CD4 naive-like cluster (CD4 naive-like), characterized by expression of CCR7 and TCF7; a CD4 T central memory cluster (CD4 TCM), with high expression of LTB and S100A4; a CD4 Tph, characterized by low expression of CXCR5, high expression of CXCR3 and high expression of ICOS; two CD4 T effector memory clusters notable for high expression of granzyme K (CD4 TEM_GZMK) and granzyme B (CD4 TEM_GZMB); and a CD4 Treg cluster with high expression of FOXP3 and RTKN2. Five CD8 T cell clusters were annotated: a naive cluster (CD8 naive), highly expressing CD8B, CCR7 and LEF1; a CD8T central memory cluster (CD8 TCM), with elevated expression of CD8B and LINC02446; two CD8T effector memory clusters, distinguished by high expression of granzyme K (CD8 TEM_GZMK) and high expression of granzyme B (CD8 TEM_GZMB); and a CD8 tissue resident memory-like cluster (CD8 TRM), with increased expression of NR4A2, DUSP2 and ZNF683. In addition, we identified an NK-T cell cluster (NK-T) highly expressing PRF1 and GZMB; a double-negative T cell cluster (dnT), with high expression of SYNE and MALAT1; a gamma delta T cell cluster (gdT), with high expression of TRDV2 and TRGV9; and a mucosal invariant T cell cluster (MAIT), highly expressing KLRB1 andSLC4A10. Integration of single-cell TCR sequencing and BCR sequencing data into the single-cell RNA sequencing data was performed using the R package scRepertoire67. To understand the transcriptional phenotype of T and B cells present in TLS, T and B cells identified by single-cell sequencing were matched against TCR-β and IGH clonotypes identified in microdissected TLS using the complementarity-determining region 3 amino acid sequence to identify clonotypes present in both datasets. As no matches were identified between IGH sequences identified by bulk sequencing of microdissected TLS and in the single-cell dataset, B cells were excluded from further analysis. In cases where the same clonotype was identified in multiple clusters in the single cell dataset, a putative transcriptional phenotype was assigned according to the most common single cell cluster in which the clonotype was found. The correlation between the transcriptional phenotype of clonotypes identified in peripheral blood and TIL was also evaluated in single-cell sequencing data obtained from patient OT6. Sixteen unique TCR-β sequences were present in both compartments (Supplementary Table 14), of which seven clonotypes had the same cluster identity for all cells with that clonotype and five clonotypes had the same cluster identity for at least half of single cells. In only 4/16 clonotypes were the cluster identities of cells with the same TCR-β entirely discordant (Extended Data Fig. 10d). These findings were consistent with previous work demonstrating that in circulating TILs, gene signatures of effector functions reflect those observed in the tumor68.

Multiplex immunofluorescence

Tissue sectioning, staining and imaging of FFPE MCC tumors were performed as previously described43. Stained slides were scanned with the PhenoImager HT (Akoya Biosciences) and processed using digital image analysis software, inForm v2.4.8 (Akoya Biosciences).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. TLS density in HCC tumors treated with neoadjuvant ICB compared to untreated controls.

a, TLS composition according to location in untreated (n = 52) and neoadjuvant ICB (n = 19) treated HCC tumors. Tumors found to have no TLS are not shown. b, Box-and-whisker plots showing total, peritumoral, and intratumoral TLS density in patients with locally advanced HCC treated with neoadjuvant ICB and untreated controls. c, Representative images of a single TLS in formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded (FFPE) HCC tumor stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and anti-CD3, CD8, CD20, CD56, and CXCL13. Scale bar, 250 μm. d, Comparison of cell density of CD+, CD+, CD20+, CD56+ positive cells and percent area of CXCL13+ tissue in untreated and neoadjuvant ICB-treated HCC tumors. e, Proportion of untreated and neoadjuvant ICB-treated HCC tumors found to have TLS according to non-viral or viral HCC etiology. f, Total, peritumoral, and intratumoral TLS density in untreated and neoadjuvant ICB-treated HCC tumors according to non-viral or viral HCC etiology. g-h, Box-and-whisker plots showing total (g) and peritumoral TLS density (h) according to pathologic response. NR, non-response. pPR, partial pathologic response. MPR/pCR, major pathologic response or complete response. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t-test (b, d, and f), Fisher’s exact test (e), and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test (g and h). For each box-and-whisker plot, the horizontal bar indicates the median, the upper and lower limits of the boxes the interquartile range, and the ends of the whiskers 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Relapse free survival and overall survival in HCC treated with neoadjuvant ICB, according to clinical covariates.

a-l, Kaplan-Meier curves showing relapse free survival and overall survival after surgical resection for HCC patients treated with neoadjuvant ICB, according to total TLS density (a and b), peritumoral TLS density (c and d), pathologic response (e and f), prior hepatitis C(HCV) infection (g and h), prior hepatitis B (HBV) infection (i and j), and presence or absence of CD20+CXCL13+ lymphoid aggregates in pre-treatment biopsy (k and I). Statistical significance was determined by log-rank test.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Pretreatment single marker immunohistochemistry compared to posttreatment cell density and TLS density.

a, Line plots showing density of CD3, CD8, CD20, CD56 positive cells, and percent area of tissue positive for CXCL13 in pretreatment biopsy and post-neoadjuvant ICB HCC tumors. b, Dotplots showing correlation between post-treatment TLS density and pretreatment density of CD3, CD8, CD20, CD56 positive cells, and percent area of tissue positive for CXCL13 tissue. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t-test (a) and Pearson’s correlation (b).

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. High TLS density is associated with increased T and B cell activation.

a, Principal component analysis of bulk RNA sequencing data from HCC tumors resected after neoadjuvant ICB (n = 12) assigned to high (n = 5) and low (n = 7) TLS density groups. b, Heatmap showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with a log2 fold change (log2FC) > 1 and adjusted P value < 0.05 between tumors with TLS high and low groups. Annotation rows indicate TLS density group, HCC etiology, neoadjuvant treatment, pathologic response, relapse status, and TLS density. Annotation columns at right identify DEGs belonging to Gene Oncology Biological Pathways gene sets for T cell activation, B cell activation, Cytokine production, and Dendritic Cell Antigen Processing and Presentation. c, Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes between tumors with high and low TLS density. Vertical dotted lines represent log2FC greater than or less than 1. Horizontal dotted line indicates adjusted P value of 0.05. 4 outlier genes with the lowest log2FC are excluded from the plot for the purposes of visualization. d, Gene set enrichment analysis showing differentially enriched gene sets from the HALLMARK database between tumors with high and low TLS density. e, Heatmap showing expression of the 12-chemokine TLS gene signature in TLS high and low tumors.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Identification of divergent TLS morphologies in viable tumor and tumor regression bed by immunohistochemistry and imaging mass cytometry.

a, Serial FFPE tissue sections from the tumor of patient OT7 showing multiple involuted TLS. Images show staining with hematoxylin and eosin (left) and immunohistochemistry staining for CD20 and Ki67 (top right), CD3 and CD21 (middle right), and CD4 and CD8 (bottom right). Scale bar, 500 μm. b, Serial FFPE sections of a single involuted TLS from the tumor of patient OT7 stained with anti-CD20 antibody (brown). Numbers indicate the order in which the sections were cut from the tissue block. Scale bar, 250 μm. c-d, Dot plots showing representative mature (c) and involuted (d) TLS, colored according to cluster assignment of individual cells after cell segmentation. e, Box-and-whisker plots showing cell cluster density in mature versus involuted TLS for CXCR3low CD4T cells, CD57+ CD4 T cells, Macrophages, and Stroma. f, Box-and-whisker plots showing comparison of cell cluster density in mature TLS by location (intratumoral versus peritumoral). g, HLA-DR expression in the tumor cluster, by TLS morphology. Statistical significance was determined by pairwise two sample Wilcoxon test (f-g). For each box-and-whisker plot, the horizontal bar indicates the median, the upper and lower limits of the boxes the interquartile range, and the ends of the whiskers 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. T and B cell clonal dynamics of TLS.

a, Representative images showing method of identification and microdissection of individual TLS. Image on left shows HCC tumor stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) at low magnification. Insets show higher magnification of staining with H&E, anti-CD20 (magenta) and anti-Ki67 (brown), anti-CD3 (magenta) and anti-CD21 (brown), anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 (bottom right), and corresponding pre- and post-microdissection images. Scale bar, 1mm. b-c, Total number of T cell receptor beta chain (TCRβ) (b) and immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) (c) clones identified in microdissected TLS. d, Box-and-whisker plot comparing the percentage of the TCRβ or IGH repertoire of each TLS that is shared with other TLS from the same tumor, by location. e-f, Dotplots showing TCRβ (e) and IGH (f) repertoire clonality (as determined by Normalized Shannon Entropy) for matched mature and involuted TLS. g, Violin plots comparing number of IGH V gene substitutions in mature and involuted TLS, by patient. Individual data points (not shown) represent individual IGH sequences. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s honest significant difference(HSD) test (d) and two-tailed t test (e-g). For each box-and-whisker plot, the horizontal bar indicates the median, the upper and lower limits of the boxes the interquartile range, and the ends of the whiskers 1.5 times the interquartile range. For each violin plot, the horizontal bar indicates the median and the upper and lower limits of the boxes the interquartile range.

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. T and B cell clonal dynamics of TLS, peripheral blood, and tumor draining lymph nodes.

a-b, Proportion of unique T cell receptor beta chain (TCRβ) clonotypes at each TLS that were also detected in matched post-treatment (a) and pre-treatment (b) peripheral blood from patients P02, P03, P07, P08, and P12. c-d, Proportion of unique TCRβ (c) and Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain (IGH) (d) clonotypes at each TLS that were identified in the TDLN of patients OT1 and OT6. e-f, Representative upset plots showing overlap in unique TCRβ (e) and IGH (f) between tumor draining lymph node (TDLN) and microdissected TLS for patient OT1. Bottom barplots and annotation row indicate number of overlapping clonotypes between different TLS repertoires. Top stacked barplots indicate clonal composition. Bottom right stacked barplots indicate total number of unique TCRβ or IGH clonotypes identified and overall clonal composition.

Extended Data Fig. 8 |. Single cell gene expression and T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire characteristics of post-treatment peripheral blood.

a, UMAPs showing gene expression of CD3E, CD4, CD8A, CCR7, SELL, GZMK, PDCD1, CXCL13, TOX, and ZNF683 across all single cells sequenced from post-treatment peripheral blood of 7 HCC patients treated with neoadjuvant ICB. b, Heatmap showing gene expression of the top 3 differentially expressed genes per cluster. Rows represent single genes and columns represent individual cells. Annotation bar indicates cluster identity, whether each cell had a sequenced TCR, the clonality of the TCR, and whether the TCR was identified in microdissected TLS from the same patient. Clusters were downsampled to 75 cells per cluster for visualization. c-e, Volcano plots showing differentially expressed genes in the CD8 TEM_GZMK (c), CD8 TEM_GZMB (d), and CD4 Tph (e) clusters compared to all other cells. Vertical dotted lines indicate a fold change of greater or less than 1.4 and horizontal line indicates a P value of 0.05. Labeled genes in c and d indicate genes with the highest differential expression. Labeled genes in e indicate genes known to be highly expressed in CD4 Tph.

Extended Data Fig. 9 |. Single cell gene expression and T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire characteristics of post-treatment tumor infiltrating lymphocytes from patient OT6.