Abstract

This study focuses on the contamination of groundwater by heavy metals (HMs) in the Kurdistan Province of Iran, an area heavily reliant on these water resources, especially in rural regions. This research aimed to quantify the concentrations of 20 HMs in groundwater sources and assess the associated health risks, including both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic effects, for different age groups. The study was conducted in 2024. We collected 155 groundwater samples from water resources of the villages in Kurdistan Province, west of Iran. The study encompassed comprehensive sampling of groundwater from various wells and springs throughout the province, which was subsequently subjected to thorough laboratory analysis utilizing Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectroscopy (ICP-MS) for the quantification of heavy metal (HM) concentrations. The highest concentrations of As, Co, Cu, and Mo were 7.90, 0.22, 2.48, and 1.68 μg/l, respectively. It was related to the cities of Qorveh, Sanandaj, Baneh, and Qorveh respectively. A Health Risk Assessment (HRA) was performed, indicating that, while the concentrations of most HMs were within the thresholds established by national and international standards, certain metals, such as arsenic and lithium, presented notable non-carcinogenic risks, especially to children. These metals were responsible for over 48 % of the cumulative hazard index (HI) across all ten cities evaluated. Furthermore, the HI for the adult demographic exceeded 1.0 (specifically 1.23) exclusively in Qorwe city. The study also identified a high carcinogenic risk associated with lead across the province, which has a carcinogenic risk of 7.3 × 10−03 in 10 studied cities, which is more than the guideline value of 10−04. The findings underscore the urgent need for continuous monitoring and the implementation of preventive measures to safeguard public health. The results provide crucial insights for policymakers and health authorities, facilitating informed decisions to mitigate the health risks posed by HM contamination in the region's groundwater.

Keywords: Heavy metals, Risk assessment, Water resource, Pollution

1. Introduction

Water is a fluid that is essential for the life of human beings and other living organisms. Of all the water on the Earth, freshwater accounts for only 3 % and humans have access to only 0.01 % of this amount for various purposes [1]. Countries experiencing moderate to high water stress have accommodated about one-third of the world's population. Furthermore, water scarcity, on one hand, and the increasing population growth, on the other hand, have put many regions of the world under the influence of water scarcity [2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that by 2025, half of the world's population will face water scarcity [3]. Groundwater constitutes at least half of the freshwater resources worldwide and is used for various purposes such as drinking, agriculture, and industrial uses [4]. Groundwater represents a critical source of potable water, supplying approximately one-third of the global population [5]. Suitable microbiological quality, acceptable aesthetic properties, ease of purification, and desirable physical characteristics (taste, odor, and color) have made the use of groundwater resources widespread and a priority [6]. However, various studies have shown the possibility of its pollution due to different pollutants. Among these pollutants, heavy metals (HMs) and their compounds have garnered significant attention from researchers. These pollutants originate from both natural sources (water and air, groundwater flow through various types of rocks, topography, soil type, and saltwater intrusion in coastal areas) and human activities (wastewater discharge, mining, industries, and agricultural activities), leaving undesirable effects on the quality of groundwater [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11]]. The presence of HMs in drinking water after conventional treatment processes and the possibility of creating chronic cumulative effects in small amounts classify these metals as hazardous pollutants with severe negative effects on human health [12]. The intensity of these pollutants' effects has led to their inclusion in the 2007 CERCLA Priority List of Hazardous Substances [13].

The high toxicity in small amounts, non-biodegradability in elemental forms, tendency to form more toxic organic compounds, long-term stability, and biological accumulation in various body tissues are among the most important characteristics of HMs that pose significant health risks to populations [[14], [15], [16], [17]]. The toxic effects and lethality of HMs occur through mechanisms that override the organism's control mechanisms and arise after establishing connections with specific cellular components [18]. Drinking water ingestion accounts for the majority of human exposure to HMs through three human exposure pathways, including absorption, inhalation, and ingestion [19,20]. Some HMs are essential for the body's natural functions. These metals serve as facilitators of reactions and major catalysts in the body's biochemical reactions. However, high concentrations of these metals pose health risks to human populations [4,9]. Moreover, their accumulation in water sources can lead to public dissatisfaction due to the reduction in aesthetic quality characteristics [21]. Although concentrations lower than the standard levels of these metals can slow down biological functions [22]. Growth and reproductive processes require the presence of necessary amounts of iron, cobalt, copper, zinc, chromium, vanadium, selenium, and molybdenum in the body, and excessive accumulation of these metals can lead to toxicity [23].

Accumulation of aluminum and copper in drinking water also plays a role in the development of Alzheimer's disease [23,24] and gastrointestinal disorders [25]. Another group of HMs includes arsenic, lead, mercury, cadmium, and nickel, which exhibit more severe effects at lower concentrations and are known as toxic metals [5]. Absorption of arsenic and cadmium through the digestive system leads to diseases such as allergies and cancer, and chronic exposure to arsenic in drinking water will have an impact on bladder, lung, and prostate cancer [26]. Diseases of the cardiovascular system, skeletal system, and urinary excretion system have been observed due to long-term exposure to small amounts of cadmium. Antimony also plays a role in the development of cardiovascular diseases [25]. Lead is another toxic metal that has caused damage to the fetus and embryo in pregnant mothers, as well as anemia in other individuals [23]. Mercury has posed risks in relation to autoimmune diseases affecting human health [27]. The expansion of human activities worldwide and the production of large amounts of various pollutants, including HMs, have led to contamination of water, air, and soil, creating health risks for the human population. The severity of these risks underscores the importance and necessity of prioritizing health risks arising from these metals and evaluating them in sustainable development programs for various communities [28].

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) standards, the permitted concentration levels of various metals in drinking water are as follows: Aluminum (Al) at 50 μg/L, Arsenic (As) at 10 μg/L, Cadmium (Cd) at 5 μg/L, Chromium (Cr) at 100 μg/L, Iron (Fe) at 300 μg/L, Mercury (Hg) at 2 μg/L, Manganese (Mn) at 50 μg/L, Lead (Pb) at 15 μg/L, Zinc (Zn) at 5000 μg/L, Barium (Ba) at 2000 μg/L, Beryllium (Be) at 4 μg/L, Copper (Cu) at 1300 μg/L, and Antimony (Sb) at 6 μg/L.

Health Risk Assessment (HRA) is a method used to estimate the potential health effects of several pollutants, including HMs, in an ecosystem and quantify them, especially in aquatic environments. It has been widely used in various research studies in recent decades to increase public awareness and inform relevant authorities [29,30]. HRA involves four stages: hazard identification, exposure assessment, dose-response assessment, and characterization of risk attributes [21].

Kurdistan Province is located in a mountainous region, where agricultural activities, soil geochemistry characteristics, and the presence of various point and non-point pollutant sources, where it may create a basis for groundwater pollution with different HMs. Since groundwater is the main source of water supply, especially for drinking purposes in rural areas of the province, it is essential to conduct a continuous monitoring and surveillance of these sources for HMs contamination and compliance with national and international standards. The continuous reliance on groundwater as a primary source of drinking water by rural residents in the Kurdistan province raises concerns regarding potential contamination by various HMs and the associated health risks stemming from the accumulation of these metals in human tissues. Despite the recognized significance of this issue, there is a notable deficiency in comprehensive studies assessing the concentrations of diverse HMs across groundwater sources in the rural areas of all cities within Kurdistan province. Previous investigations have often overlooked several critical heavy metals, underscoring the necessity for further research in this domain. Additionally, it is imperative to re-evaluate the concentrations of HMs reported in earlier studies over time and to assess the health risks posed by the consumption of contaminated groundwater by the rural population. Therefore, the present study aims to quantify the concentrations of both essential and toxic heavy metals in groundwater resources, specifically wells and springs, within the rural regions of Kurdistan province. Furthermore, this research will evaluate the carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risks associated with heavy metal exposure for rural consumers across various age demographics. The results of this study provide valuable information about the current status of HMs in groundwater in the province and the health risks associated with them, empowering policymakers and decision-makers in the water and health sectors to regulate effective control and preventive management policies and enhance health indicators, ensuring the maintenance of an acceptable level of health.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study area

Kurdistan, Iran (34.3277° N, 47.0778° E) has a rural population of over 946,500 and is an area of 95 Km2 located in Western Iran. The climate of the study area is mountainous and characterized by an average annual rainfall of 455 mm and a temperature range between −15 and 40 °C.

2.2. Groundwater sampling

The sampling was undertaken in 2024 using the sampling method reported previously [16]. We collected 155 groundwater samples from 15 villages (except Baneh city, where 20 samples were collected) within a radius of 15 km in all ten cities of Kurdistan province, Iran (Fig. 1). These sampling stations were selected based on a careful study of geographical distribution, proximity to possible sources of pollution and representation of diverse environmental conditions. Wells and springs were drained at least 15 min before the start of sample collection. It was ensured that there was no air in the upper part of the bottle.

Fig. 1.

Location of the study area.

2.3. Preparation of samples

In order to sampling, polyethylene bottles were washed with 1 % nitric acid (1 % HNO3), and double distilled water was used. At the time of sample collection, the containers were washed three times with well and spring water before collecting the samples. Reducing the pH below 2 was done using 20 % nitric acid to prevent the possible precipitation of cations, increasing the pH and the growth of microorganisms and minimizing surface absorption by the vessel walls. All samples were transported to the laboratory in chilled containers and kept in a refrigerator at 4 °C until analysis. Analysis was done 48 h after sampling. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectroscopy (ICP-MS) was used to quantify the concentration of 20 studied heavy metals (Al, As, Hg, Cd, Pb, Co, Cr, Ni, Zn, Fe, Mn, Ba, Br, Cu, Li, Mu, V, Sb, Sr, and Sn). The instrument used was ICP-OES with flared end EOP torch 2.5 mm and a pump rate of 30 RPM (Spectro arcos, Germany). All measurements were conducted three times for each sample to ensure repeatability.

2.4. Human health risk assessment

2.4.1. Non-carcinogenic health risk

In order to evaluate the non-carcinogenic risk associated with heavy metals through drinking underground water, Eq. (1) was used as follows [31,32]:

| (1) |

Where HQing is the hazard quotient, IRing is the ingestion rate (ml/d), EFi is the frequency of exposure (d/yr), ED is the exposure duration (yr), Ci is the heavy metals concentration (μg/L), BW is the average body weight (kg), AT is the average time for non-carcinogen exposure that = (EF × ED) (d), RfDing indicate the oral reference dose (μg/kg.d) and 10−3 represents a unit transfer factor.

The HI is a parameter that provides a comprehensive assessment of the cumulative risk of several heavy metals, taking into account the combined effects of their risk contribution. A HI value below 1 indicates that there is no non-carcinogenic risk to human health. However, if the value of HI is equal to or greater than 1, it indicates non-carcinogenic risks, which increase with the value of HI. This parameter was calculated using Eq. (2) as follows [33]:

| (2) |

where n and i refer to the number of metal elements and the ith HM, respectively.

2.4.2. Carcinogenic health risk

Excess Lifetime Cancer Risk (ELCR) was calculated by the carcinogenicity slope factor (CSF), through Eq.)3) [34,35].

| (3) |

According to WHO guidelines, in general, a ELCR less than 10−6 indicates a negligible carcinogenic risk to human health, a ELCR between 10−6 and 10−4 indicates an acceptable risk, and a ELCR above 10−4 indicates a high risk to human health [36].

The total carcinogenic risk was calculated using the sum of the carcinogenic risk of all toxic heavy metals using Eq. (4) [37].

| (4) |

Parameters and values for each age group are listed in Table 1 to assess human health risk. The values of RfD and CSF of the studied heavy metals were collected from WHO [38], US EPA [39], the study of Maleki et al. [28] and presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Parameters and assumptions of health risk assessment due to groundwater ingestion.

| Human health risk assessment parameters | Unit | Values |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Children | ||

| Concentration (C) | μg/l | Measured | Measured |

| Ingestion Rate (IR) | ml/day | 2000 | 1000 |

| Exposure Frequency (EF) | Days/year | 365 | 365 |

| Exposure Duration (ED) | Years | 30 | 6 |

| Average Time (AT) for carcinogens | Days | 25550 | 25550 |

| Average Time (AT) for non-carcinogens | Days | 10950 | 2160 |

| Average Body Weight (BW) | kg | 70 | 15 |

Table 2.

Oral reference dose (RfD) and carcinogenic slope factor (CSF) for each heavy metal (μg/kg/d).

| HM | Factors |

|

|---|---|---|

| RfD | CSF | |

| Al | 1000 | – |

| As | 0.3 | 1500 |

| Cd | 0.5 | 610 |

| Co | 0.3 | – |

| Cr | 0.9 | 500 |

| Fe | 700 | – |

| Hg | 0.3 | – |

| Mn | 24 | – |

| Pb | 3.5 | 8.5 |

| Zn | 300 | – |

| Ba | 200 | – |

| Be | 2 | – |

| Cu | 40 | – |

| Li | 2 | – |

| Mo | 5 | – |

| Ni | 20 | 1700 |

| Sb | 0.4 | – |

| Sn | 600 | – |

| Sr | 600 | – |

| V | 0.7 | – |

2.5. Statistical analysis

SPSS version 20 software was used to analyze descriptive statistics including mean and standard deviation. Excel software was used to measure health risk and prepare health risk forms based on metals and different cities. Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests were used to analyze the difference in the level of metals in different cities by Graphpad prism version 10 software.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Concentration of heavy metals in groundwaters

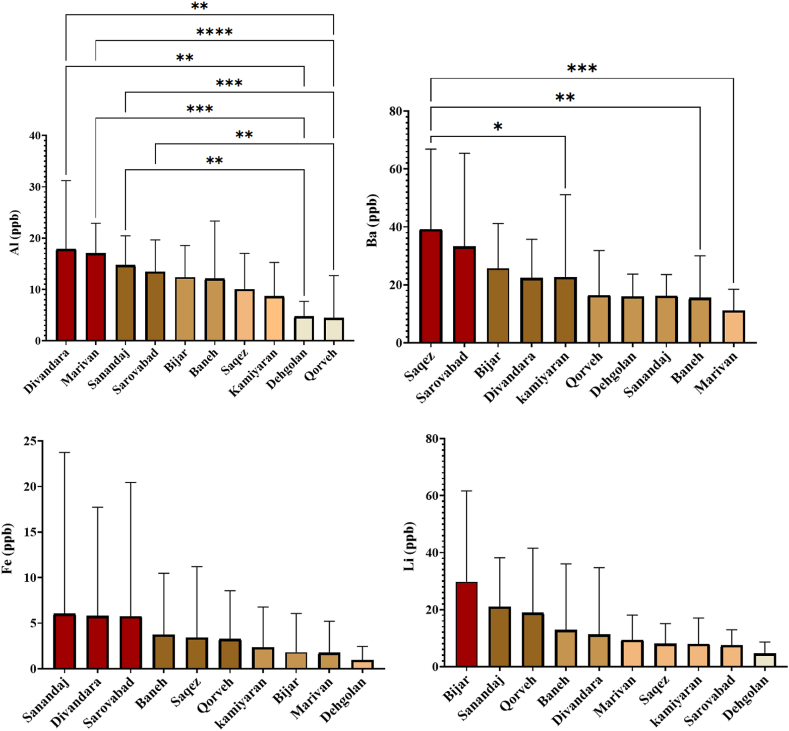

The range of pH measured in the sampling sites was between 6.8 and 8.5 with an average of 7.5, and the amount of chlorine was between 0 and 2.7 mg/l with an average of 0.3 mg/l, which is in accordance with the national standards of Iran 1053 [40], (WHO) [38], and USEPA standards [41] (Table 3)., Based on Faraji et al., the pH of groundwater samples was 6.8–8.6 with an average of 7.7 [42]. The results of measuring the concentration of heavy metals and physicochemical parameters are shown in Table 4. Comparing these results with Iran's 1053 national standards, WHO and EPA showed that only 0.65 % of the samples containing arsenic exceeded the permissible values of all three standards and the concentration of all other heavy metals was lower than the values of the three compared standards. The reason for this can be the natural geological structure in the underground aquifers and the calcareous structure of the soils in the region, agricultural activity and the existence of human activities resulting from the extraction of gold from the existing gold mine in the region [7,28]. Moreover, the lowest measured concentration in all the studied villages was attributed to Be, which was below the detection limit (<0.042 μg/l). Whereas, the highest measured concentrations were related to St in Bijar, Saqqez, Sanandaj, Marivan, Sarvabad, Divandareh, Qorveh, Dehgolan, and Kamiyaran with values of 223.36, 160.13, 159.74, 130.07, 124.36, 119.87, 118.88, 115.73, and 112.8 μg/l, respectively. Zn in Baneh city was 75.23 μg/l. Meanwhile, Fig. 2 compares the mean concentrations of Zn, V, Sr, Sn, Ni, Mn, Li, Fe, Ba, and Al in drinking water resources of different cities in Kurdistan Province. The lines above each graph in Fig. 2 show the significancy of HMs level in drinking waters of villages at different cities within the province. For example, the difference between the Al concentration was significant in water samples of rural areas of Dehgolan and Divandareh (p < 0.005) and Marivan and Qorveh (p < 0.001). Moreover, the difference between the concentration of Sn, Mn, Li, and Fe was not significant (p > 0.05) within the whole province.

Table 3.

Heavy metals concentration, statistical and physicochemical parameters measured in groundwater resources in the studied areas.

| City | Descriptive parameters | pH | Cl (mg/l) | As (μg/l) | Cd (μg/l) | Co (μg/l) | Cr (μg/l) | Hg (μg/l) | Pb (μg/l) | Be (μg/l) | Cu (μg/l) | Mo (μg/l) | Sb (μg/l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanandaj | Max | 8.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 |

| Min | 7.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| Mean | 7.63 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| S.D | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Dehgolan | Max | 7.80 | 1.70 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 |

| Min | 7.20 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| Mean | 7.57 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| S.D | 0.19 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Sarvabad | Max | 8.20 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 |

| Min | 7.20 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| Mean | 7.69 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| S.D | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Kamyaran | Max | 8.10 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 |

| Min | 7.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| Mean | 7.79 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| S.D | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Qorveh | Max | 8.00 | 2.70 | 8.10 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 2.03 | 0.46 |

| Min | 6.80 | 0.00 | 7.70 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.32 | 0.46 | |

| Mean | 7.72 | 0.66 | 7.90 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.68 | 0.46 | |

| S.D | 0.33 | 0.99 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | |

| Divandareh | Max | 7.80 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 |

| Min | 6.80 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| Mean | 7.19 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| S.D | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Saqqez | Max | 7.80 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 |

| Min | 7.20 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| Mean | 7.32 | 0.34 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| S.D | 0.18 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Marivan | Max | 7.80 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 |

| Min | 6.80 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| Mean | 7.31 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| S.D | 0.28 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Baneh | Max | 8.50 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 2.77 | 1.67 | 0.46 |

| Min | 6.80 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 2.19 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| Mean | 7.29 | 0.32 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 2.48 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| S.D | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Bijar | Max | 8.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.57 | 1.67 | 0.46 |

| Min | 7.20 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| Mean | 7.65 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 2.17 | 0.04 | 0.44 | 1.67 | 0.46 | |

| S.D | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Table 4.

Drinking groundwater standards.

| Heavy metals and Physicochemical parameters | Unit | Risk-based drinking groundwater criteria |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISIRI (Iran) IS:1053 [40] | WHO [38] | US. EPA [41] | ||

| pH | – | 6.5–9 | – | 6.5–8.5 |

| Cl | mg/l | – | – | – |

| Al | μg/l | N | 50–200 | |

| As | μg/l | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Cd | μg/l | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Co | μg/l | – | – | – |

| Cr | μg/l | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| Fe | μg/l | – | – | 300 |

| Hg | μg/l | 6 | 6 | 2 |

| Mn | μg/l | 400 | 80 | 50 |

| Pb | μg/l | 10 | 10 | 15 |

| Zn | μg/l | – | – | 5000 |

| Ba | μg/l | 700 | 1300 | 2000 |

| Be | μg/l | – | – | 4 |

| Cu | μg/l | 2000 | 2000 | 1300 |

| Li | μg/l | – | – | – |

| Mo | μg/l | 70 | – | – |

| Ni | μg/l | 70 | 70 | – |

| Sb | μg/l | 20 | 20 | 6 |

| Sn | μg/l | – | – | – |

| Sr | μg/l | – | – | – |

| V | μg/l | 100 | – | – |

Fig. 2.

Mean Concentration of heavy metals (Zn, V, Sr, Sn, Ni, Mn, Li, Fe, Ba, and Al) in rural water resources of Kurdistan Province: ∗: p < 0,05, ∗∗: p < 0.005, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

3.2. Health risk assessment

Because only values lower than the standard levels of heavy metals do not indicate a suitable level of health for the consumers of drinking water containing these substances, the non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic health risks caused by the exposure of different age groups to heavy metals were evaluated in this study.

3.2.1. Non-carcinogenic risk assessment

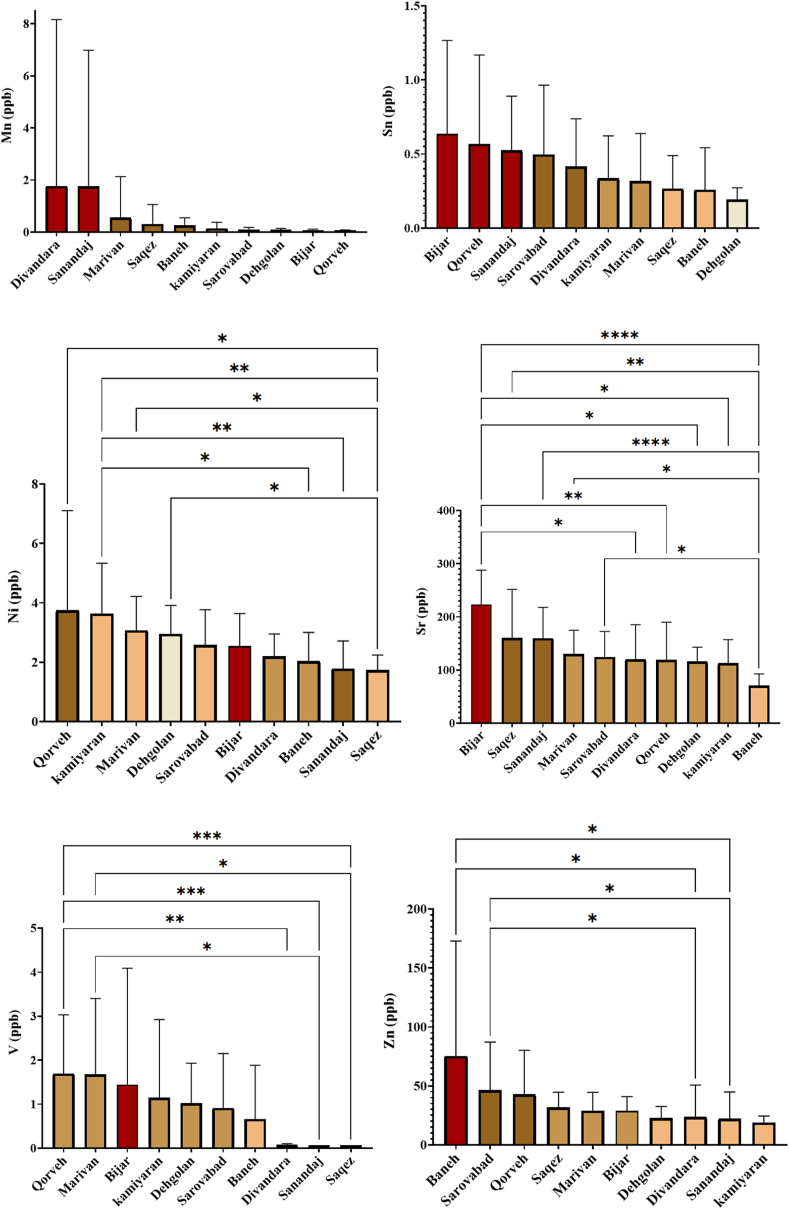

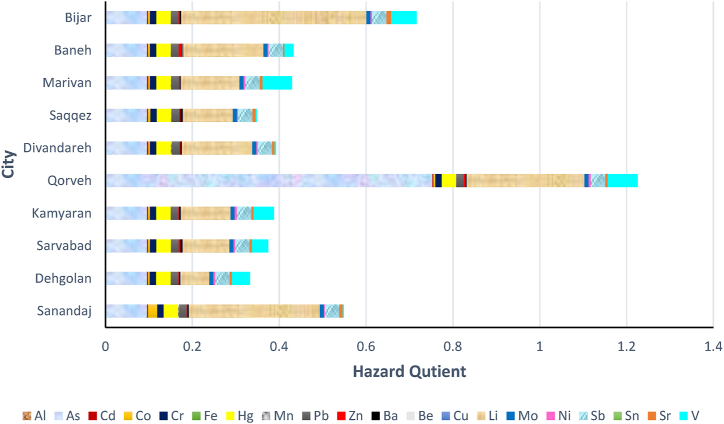

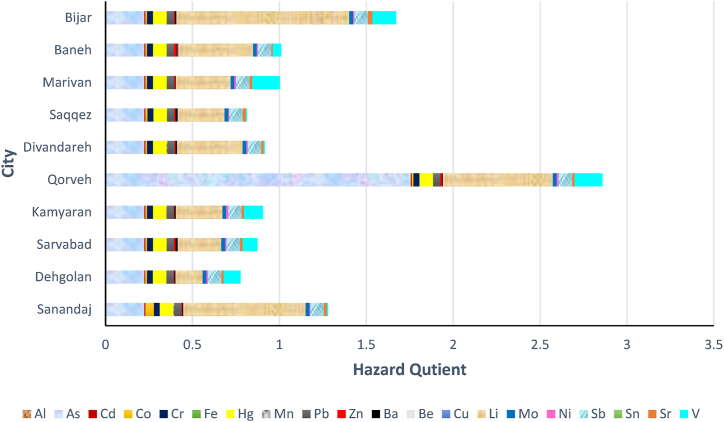

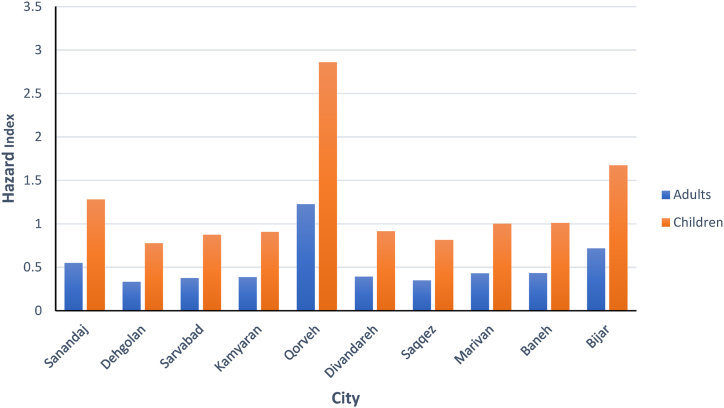

According to the non-carcinogenic health risk assessment results presented in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, the lowest share of non-carcinogenic risk in all 10 cities in both children and adults age groups is related to tin metal, and the highest share of non-carcinogenic risk is also in two Dehgolan and Qorveh cities are related to arsenic metal. However, it is related to lithium metal in other cities. Low levels of Li have beneficial effects on humans. However, its concentration of 15–20 mg/L in blood is toxic to humans and lead to nausea, visual impairment, and kidney problems, and can even cause medical emergencies such as coma and cardiac arrest. Li salts are naturally deposited mainly in rocks, minerals, or mines with different concentrations. Nevertheless, sedimentary rocks (mostly clay) contain Li minerals. It rarely exists in high concentrations in various environments including groundwater. Water sources passing through rocks rich in Li reserves, especially at lower depths, can have higher Li concentrations than the background levels. This metal is very mobile and has a great affinity with silicate compounds. Therefore, geological factors and hydrological regimes most likely lead to fluctuations in Li concentration in groundwaters. Li pollution can be caused by human activities such as exploitation and processing of ore reserves and smelting and casting, chemical production facilities, infiltration of leachate from landfills into groundwater, leakage from production and recycling facilities, and industrial effluents. However, according to the type of radial sampling, the high concentration of Li in the groundwaters of Kurdistan province is probably due to its location in the Zagros Mountain range having a sedimentary rock texture, the presence of numerous mineral water springs, and the presence of numerous mineral deposits. As it seems that Li pollution caused by human activities has mainly played a lesser role in increasing the concentration and health risk caused by this metal, and it has caused the aggravation of this effect in susceptible areas(43–46). Among the studied heavy metals, two metals, lithium and arsenic, had the greatest role in the estimation of the HI in such a way that they accounted for more than 48 % of the hazard index in all 10 cities. Manavi et al., in 2024 assessed the health risk of heavy metals Ag, Mn, Cr, V, Mo and Sr in Qatar and concluded that the average HQ of all studied metals is lower than the standard value (1) and in the range between 2.49 × 10−3 to 7.41 × 10−1 were related to Mn and V, respectively. It was also found that the HQ of the investigated heavy metals was in the order of V > Sr > Mo > Ag > Cr > Mn, which accounted for the largest share of risk in the total of V and Sr metals, which was not consistent with the present study [43]. Elumalai et al. found that the abundance of heavy metals in groundwater was in the following order: Si > Mn > Ag > Li > Fe > Pb > Al > Cu > Ni > B > Zn > Co > Cd > Cr=Th=Zr. They also stated that Li may have been obtained from sources such as mining and related activities. A health risk assessment of Li showed that this metal has potential risks for children and adults [44]. The results of the non-carcinogenic health risk assessment presented in Fig. 3 show that the HQ of all heavy metals in the 10 studied cities is less than 1, therefore, they have no adverse health effects for the adult group. In addition, the (HI for the adult group was higher than 1 (1.23) only in Qorveh city, which can have adverse effects on the health of people in this group. According to the results of the health risk assessment of the child group in Fig. 4, only arsenic in Qorveh city had a HQ higher than 1 (1.76). The HI higher than 1 was also obtained in the cities of Sanandaj, Qorveh, Marivan, Baneh and Bijar with values of 1.67, 1.01, 1.003, 2.86 and 1.28, respectively. In their study, Vetrimurugan et al. investigated 16 HMs and assessed the health risk caused by them. The order of metals concentration was Cr < Zn < Cu < Cd < Co < Fe < Al < Ni < Ti < Zr < B < Ag < Mn < Pb < Li < Si. They reported that HI for the two adult and children groups was 11.9 and 18.3, respectively, which indicates a high non-carcinogenic risk [45]. Chabokdhara et al., in 2017 assessed the health risk of heavy metals Cu, Cr, Pb, Cd, Zn, Mn, Ni in Ghaziabad, India. The results of non-carcinogenic risk assessment calculations in the present study showed that the HQ parameter in the adult group in both pre-monsoon and post-monsoon periods was less than 1 and thus does not pose a health risk to the resident population. However, the amount of HQ in the child group in pre-monsoon for Pb and Cd was 2.4 and 2.2, respectively, and in post-monsoon for Pb, it was 1.23, which was greater than 1, and the HQ of other heavy metals was less than the dangerous value [46]. In a study conducted on the health risk assessment of Fe, Ni, Cd, and Zn metals in Iraq, Madid and Saleh also found that the HQ caused by the ingestion route in two age groups of children and adults was less than 1 and therefore a serious health risk was not noticed. It is not exposed people [47]. Comparing the HI in two age groups of children and adults (Fig. 5) showed that children face more health risks than adults from consuming water containing heavy metals in all the studied cities. In their study on heavy metals Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Pb, and Zn in Egypt, Eid et al. found that HQs less than 1 were obtained by Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, and Zn metals, and three heavy metals Cd, Cr, and Pb, in addition to having HQs greater than 1, also contribute the most to health risk in both study groups. Moreover, the value of HI in two groups of children and adults was 53.6 and 14.04, respectively, which indicated the greater vulnerability of the child group compared with the adult group [35].

Fig. 3.

Hazard Quotient of heavy metals in the adult age group in the studied cities.

Fig. 4.

Hazard Quotient of heavy metals in the children age group in the studied cities.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of hazard index between child and adult age groups.

In another study conducted by Malakootian et al. (2020), HMs concentration was determined using ICP-OES and it was found that the HQ showed rational non-carcinogenic risk for Zn and Ni and unacceptable risk for As and Cd. The As ELCR level was unacceptably high. They concluded that the groundwater resources of the study area are not recommended for drinking purpose as there are high risk involved for As and Cd consumption [48].

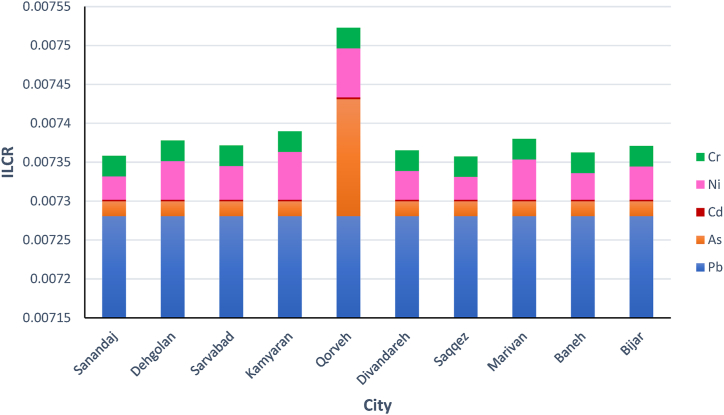

3.2.2. Carcinogenic risk assessment

According to the availability of five metals lead, arsenic, nickel, cadmium and chromium in CSF, the results of carcinogenic risk assessment of these metals are presented in Fig. 6. The lowest carcinogenic risk (2.29 × 10−06) was obtained by cadmium in the 10 studied cities. According to the results obtained, the highest risk of carcinogenesis is lead metal, which has a carcinogenic risk of 7.3 × 10−03 in 10 studied cities, which is more than the guideline value of 10−04, affecting the population of the entire province. The risk of carcinogenesis caused by arsenic metal (1.5 × 10−4) was found to be higher than the guideline value only in Qorveh city, which exposes the population living in the region to double carcinogenic risks, while it is acceptable in other cities. The risk of carcinogenesis caused by nickel and chromium is in the acceptable risk range with the values of (2.91 × 10−05-6.3 × 10−05) and (2.63 × 10−05), respectively. Placing the total carcinogenic risk due to the cumulative effects of five carcinogenic metals in the range (7.4 × 10−03-7.5 × 10−03) indicates a high carcinogenic risk in the whole province, which requires preventive measures to eliminate the risk. In the study that Liu and Ma conducted in China, the carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk of three metals Cr, Cd, Ni were investigated in eight periods and it was found that cadmium in general had HQ less than 1 and its carcinogenic risk was insignificant (<10-6). Moreover, nickel and chromium generally have HQs greater than 1 and their carcinogenic risk was in the acceptable range (10-4-10−6) [49]. The health risk assessment of heavy metals As, Cr, Ni, Pb and Cd, which was carried out by Ravindra and Moore in India, showed that only cadmium had no carcinogenic effect, and long-term consumption of water containing As, Cr, Ni and Pb could impose carcinogenic risks on the residents [50].

Fig. 6.

Cumulative carcinogenic risk induced by carcinogenic heavy metals in the studied cities.

4. Conclusion

Groundwater in Kurdistan province of Iran is contaminated by heavy metals (HMs), posing health risks due to factors like natural geological issues and human activities. Sampling showed HMs like arsenic and lithium exceeding standards, with lead posing high carcinogenic risks. Health risk assessment revealed potential risks to children and adults, emphasizing the need for monitoring and preventive measures. The study highlights the significance of safeguarding public health and informs policymakers on managing HM contamination in groundwater. The scarcity of freshwater worldwide makes groundwater vital for various purposes, but pollution from HMs threatens human health. Exposure pathways like ingestion, inhalation, and absorption lead to toxicity, affecting biological functions and posing risks like cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and gastrointestinal disorders. Health risk assessments like hazard quotient and carcinogenicity slope factor assist in evaluating risks associated with HMs, aiding in public health management and sustainable development efforts. Overall, understanding the concentration of HMs in groundwater, associated health risks, and implementing control measures is crucial for maintaining a healthy environment and ensuring the well-being of the population.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Payam Younesi Baneh: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation. Borhan Ahmadi: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Hamzeh Salehzadeh: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. Hady Mohammadi: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis. B. Shahmoradi: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Bayazid Ghaderi: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Data and code availability statement

• No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This research work was approved by Ethics Committee (IR.MUK.REC.1402.199), Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran. Meanwhile we confirm that no financial support or funding was provided for this work.

Contributor Information

Payam Younesi Baneh, Email: unc.payam@gmail.com, p.younesibaneh@gmail.com.

Borhan Ahmadi, Email: ahmadiborhan95@gmail.com.

Hamzeh Salehzadeh, Email: hamzeh.salehzadeh@gmail.com.

Hady Mohammadi, Email: mohammadihady2000@gmail.com.

B. Shahmoradi, Email: bshahmorady@gmail.com, bshahmoradi@muk.ac.ir.

Bayazid Ghaderi, Email: bayazidg@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Hussain S., Habib-Ur-Rehman M., Khanam T., Sheer A., Kebin Z., Jianjun Y. Health risk assessment of different heavy metals dissolved in drinking water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16(10):1737. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enitan I.T., Enitan A.M., Odiyo J.O., Alhassan M.M. Human health risk assessment of trace metals in surface water due to leachate from the municipal dumpsite by pollution index: a case study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria. Open Chem. 2018;16(1):214–227. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khalid S., Shahid M., Natasha, Shah A.H., Saeed F., Ali M., et al. Heavy metal contamination and exposure risk assessment via drinking groundwater in Vehari, Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2020;27:39852–39864. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-10106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yahaya T.O., Oladele E.O., Fatodu I.A., Abdulazeez A., Yeldu Y.I. The concentration and health risk assessment of heavy metals and microorganisms in the groundwater of Lagos. Southwest Nigeria. 2021;8(3):225–233. doi: 10.22102/JAEHR.2020.245629.1183. arXiv preprint arXiv:210104917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadeghi M., Noroozi M. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk assessment of heavy metals in water resources of north east of Iran in 2018. Journal of Environmental Health and Sustainable Development. 2021;6(2):1321–1329. doi: 10.18502/jehsd.v6i2.6543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edokpayi J.N., Enitan A.M., Mutileni N., Odiyo J.O. Evaluation of water quality and human risk assessment due to heavy metals in groundwater around Muledane area of Vhembe District, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Chem. Cent. J. 2018;12:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13065-017-0369-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solgi E., Jalili M. Zoning and human health risk assessment of arsenic and nitrate contamination in groundwater of agricultural areas of the twenty two village with geostatistics (Case study: chahardoli Plain of Qorveh, Kurdistan Province, Iran) Agric. Water Manag. 2021;255 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shakerkhatibi M., Mosaferi M., Pourakbar M., Ahmadnejad M., Safavi N., Banitorab F. Comprehensive investigation of groundwater quality in the north-west of Iran: physicochemical and heavy metal analysis. Groundwater for Sustainable Development. 2019;8:156–168. [Google Scholar]

- 9.eleem E.M., Mostafa A., Mokhtar M., Salman S.A. Risk assessment of heavy metals in drinking water on the human health, Assiut City, and its environs, Egypt. Arabian J. Geosci. 2021;14:1–11. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh A., Sharma A., Verma R.K., Chopade R.L., Pandit P.P., Nagar V., et al. The Toxicity of Environmental Pollutants. IntechOpen; 2022. Heavy metal contamination of water and their toxic effect on living organisms. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishna A.K., Mohan K.R. Risk assessment of heavy metals and their source distribution in waters of a contaminated industrial site. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2014;21(5):3653–3669. doi: 10.1007/s11356-013-2359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao S., Gong Y., Yang S., Chen S., Huang D., Yang K., et al. Health risk assessment of heavy metals and disinfection by-products in drinking water in megacities in China: a study based on age groups and Monte Carlo simulations. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023;262 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saleh H.N., Panahande M., Yousefi M., Asghari F.B., Oliveri Conti G., Talaee E., et al. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk assessment of heavy metals in groundwater wells in Neyshabur Plain, Iran. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019;190:251–261. doi: 10.1007/s12011-018-1516-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong W., Zhang Y., Quan X. Health risk assessment of heavy metals and pesticides: a case study in the main drinking water source in Dalian, China. Chemosphere. 2020;242 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muhammad S., Shah M.T., Khan S. Health risk assessment of heavy metals and their source apportionment in drinking water of Kohistan region, northern Pakistan. Microchem. J. 2011;98(2):334–343. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamid E., Payandeh K., Karimi Nezhad M.T., Saadati N. Potential ecological risk assessment of heavy metals (trace elements) in coastal soils of southwest Iran. Front. Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.889130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang Z., Liu C., Zhao X., Dong J., Zheng B. Risk assessment of heavy metals in the surface sediment at the drinking water source of the Xiangjiang River in South China. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020;32:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang G., Hu X., Zhu Y., Jiang H., Wang H. Historical accumulation and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in sediments of a drinking water lake. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2018;25:24882–24894. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2539-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fakhri Y., Saha N., Ghanbari S., Rasouli M., Miri A., Avazpour M., et al. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risks of metal (oid) s in tap water from Ilam city, Iran. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018;118:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ab Razak NH., Praveena S.M., Aris A.Z., Hashim Z. Drinking water studies: a review on heavy metal, application of biomarker and health risk assessment (a special focus in Malaysia) Journal of epidemiology and global health. 2015;5(4):297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu G., Rana A., Mian H.R., Saleem S., Mohseni M., Jasim S., et al. Human health risk-based life cycle assessment of drinking water treatment for heavy metal (loids) removal. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;267 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasool A., Xiao T., Farooqi A., Shafeeque M., Masood S., Ali S., et al. Arsenic and heavy metal contaminations in the tube well water of Punjab, Pakistan and risk assessment: a case study. Ecol. Eng. 2016;95:90–100. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abedi Sarvestani R., Aghasi M. Health risk assessment of heavy metals exposure (lead, cadmium, and copper) through drinking water consumption in Kerman city, Iran. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019;78(24):714. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Q., Gao J., Li G., Tao H., Shi B. Accumulation and re-release of metallic pollutants during drinking water distribution and health risk assessment. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology. 2019;5(8):1371–1379. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alidadi H., Tavakoly Sany S.B., Zarif Garaati Oftadeh B., Mohamad T., Shamszade H., Fakhari M. Health risk assessments of arsenic and toxic heavy metal exposure in drinking water in northeast Iran. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019;24:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12199-019-0812-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wongsasuluk P., Chotpantarat S., Siriwong W., Robson M. Heavy metal contamination and human health risk assessment in drinking water from shallow groundwater wells in an agricultural area in Ubon Ratchathani province, Thailand. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2014;36:169–182. doi: 10.1007/s10653-013-9537-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fallahzadeh R.A., Ghaneian M.T., Miri M., Dashti M.M. Spatial analysis and health risk assessment of heavy metals concentration in drinking water resources. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2017;24:24790–24802. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maleki A., Jari H. Evaluation of drinking water quality and non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risk assessment of heavy metals in rural areas of Kurdistan. Environmental Technology & Innovation. 2021;23 Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammadi A.A., Zarei A., Majidi S., Ghaderpoury A., Hashempour Y., Saghi M.H., et al. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risk assessment of heavy metals in drinking water of Khorramabad, Iran. MethodsX. 2019;6:1642–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2019.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emmanuel U.C., Chukwudi M.I., Monday S.S., Anthony A.I. Human health risk assessment of heavy metals in drinking water sources in three senatorial districts of Anambra State, Nigeria. Toxicol Rep. 2022;9:869–875. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2022.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vasseghian Y., Almomani F., Dragoi E.-N. Health risk assessment induced by trace toxic metals in tap drinking water: condorcet principle development. Chemosphere. 2022;286 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng C., Cai Y., Wang T., Xiao R., Chen W. Regional probabilistic risk assessment of heavy metals in different environmental media and land uses: an urbanization-affected drinking water supply area. Sci. Rep. 2016;6(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep37084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagh V.M., Panaskar D.B., Mukate S.V., Gaikwad S.K., Muley A.A., Varade A.M. Health risk assessment of heavy metal contamination in groundwater of Kadava River Basin, Nashik, India. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment. 2018;4:969–980. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Badeenezhad A., Soleimani H., Shahsavani S., Parseh I., Mohammadpour A., Azadbakht O., et al. Comprehensive health risk analysis of heavy metal pollution using water quality indices and Monte Carlo simulation in R software. Sci. Rep. 2023;13(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-43161-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eid M.H., Eissa M., Mohamed E.A., Ramadan H.S., Tamás M., Kovács A., et al. New approach into human health risk assessment associated with heavy metals in surface water and groundwater using Monte Carlo Method. Sci. Rep. 2024;14(1):1008. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-50000-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shehu A., Vasjari M., Duka S., Vallja L., Broli N., Cenolli S. Assessment of health risk induced by heavy metal contents in drinking water. J. Water, Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2022;12(11):816–827. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Z., Tao S., Sun Z., Chen Y., Xu J. Determination of heavy metals and health risk assessment in tap water from wuhan, China, a city with multiple drinking water sources. Water. 2023;15(21):3709. [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHO . Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. Fourth Edition Incorporating the First and Second Addenda. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240045064 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Provisional Peer-Reviewed Toxicity Values (PPRTVs) Assessments. https://www.epa.gov/pprtv/provisional-peer-reviewed-toxicity-values-pprtvs-assessments.

- 40.Nouri A., Sadeghnezhad R., Soori M.M., Mozaffari P., Sadeghi S., Ebrahemzadih M., et al. Physical, chemical, and microbial quality of drinking water in Sanandaj, Iran. Journal of Advances in Environmental Health Research. 2018;6(4):210–216. [Google Scholar]

- 41.USEPA . United States Environmental Protection Agency; Washington DC: 2018. 2018 Edition of the Drinking Water Standards and Health Advisories Tables.https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2018-03/documents/dwtable2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eslami F., Yaghmaeian K., Mohammadi A., Salari M., Faraji M. An integrated evaluation of groundwater quality using drinking water quality indices and hydrochemical characteristics: a case study in Jiroft, Iran. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019;78:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manawi Y., Subeh M., Al-Marri J., Al-Sulaiti H. Spatial variations and health risk assessment of heavy metal levels in groundwater of Qatar. Sci. Rep. 2024;14(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-64201-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elumalai V., Brindha K., Lakshmanan E. Human exposure risk assessment due to heavy metals in groundwater by pollution index and multivariate statistical methods: a case study from South Africa. Water. 2017;9(4):234. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vetrimurugan E., Brindha K., Elango L., Ndwandwe O.M. Human exposure risk to heavy metals through groundwater used for drinking in an intensively irrigated river delta. Appl. Water Sci. 2017;7:3267–3280. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chabukdhara M., Gupta S.K., Kotecha Y., Nema A.K. Groundwater quality in Ghaziabad district, Uttar Pradesh, India: multivariate and health risk assessment. Chemosphere. 2017;179:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madeed H.I., Saleh M.A., editors. ASSESSMENT OF LEVELS OF SOME HEAVY ELEMENTS IN GROUNDWATER OF AL-HAWIJA DISTRICT AND STUDY THEIR HEALTH RISKS. Obstetrics and Gynaecology Forum; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malakootian M., Mohammadi A., Faraji M. Investigation of physicochemical parameters in drinking water resources and health risk assessment: a case study in NW Iran. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020;79(9):195. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu Y., Ma R. Human health risk assessment of heavy metals in groundwater in the luan river catchment within the north China Plain. Geofluids. 2020;2020(1) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ravindra K., Mor S. Distribution and health risk assessment of arsenic and selected heavy metals in Groundwater of Chandigarh, India. Environmental pollution. 2019;250:820–830. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

• No data was used for the research described in the article.