Abstract

Introduction and importance

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) affects the musculoskeletal system as well as the cervical spine. It is associated with severe, progressive cervical kyphosis. Surgical intervention is the treatment of choice to avoid neurological impairment and malalignment.

Case presentation

We herein report an 11-year-old NF-1 patient with severe cervical kyphosis and intact neurological status. We applied five days of cervical traction followed by surgery utilizing the combined cervical approach (posterior release, anterior corpectomy and reconstruction, and posterior cervicothoracic instrumentation). In one-year follow-up, atlantoaxial dislocation (AAD) and basilar invagination (BI) were detected in neuroimagings. The complication was corrected by adding C1 to the previous construct via unilateral C1 lateral mass screw, contralateral C1 sublaminar hook, unilateral C3 and contralateral C4 sublaminar hook insertion, fixed with contoured rods medial to previous rods. This led to the correction of the AAD and the BI and the patients remained neurologically intact.

Clinical discussion

Severe cervical kyphosis in the setting of NF-1 is progressive and carries a considerable risk of neurologic compromise. Surgical intervention is thus necessary.

Conclusion

The combined approach with complete spinal column reconstruction is the surgical approach of choice. However, complete curve correction to near-normal lordosis carries the risk of proximal junctional failure (PJF).

Keywords: Neurofibromatosis-1, Cervical kyphosis, Proximal junctional failure, Atlantoaxial dislocation, Basilar invagination

Highlights

-

•

NF-1 is associated with spine deformities such as cervical kyphosis.

-

•

Cervical kyphosis in NF-1 patients requires surgical resection and correction.

-

•

Cervical kyphosis in NF-1 is progressive and associated with neurological impairment.

-

•

Combined approach is recommended for correction of cervical kyphosis in NF-1.

-

•

Complete curve correction to near-normal lordosis carries the risk of proximal junctional failure (PJF).

1. Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1), also referred to Von Recklinghausen disease, is a rare genetical disorder affecting multiple organs including the musculoskeletal system, with an incidence of 1/4000–1/3000 [1]. Spine deformities are among the common musculoskeletal manifestations of NF-1 with a rate of 10 %–77 % [2,3]. The spine deformities in these patients include scoliosis, kyphosis, kyphoscoliosis, lordoscoliosis, and spondylolisthesis [2]. Kyphoscoliosis is the most common spine deformity in patients with NF-1 while cervical kyphosis with dystrophic changes has been rarely reported in the literature [4]. Cervical kyphosis encompasses a wide variety of etiologies including dysplastic, spondylotic, traumatic etiologies as well as paraspinal, or intra-dural masses [5,6]. NF-1 is associated with spinal malalignments and dysplastic vertebrae [7,8]; thoracic scoliosis and cervical kyphosis are common musculoskeletal manifestations in patients with NF-1. Cervical kyphosis is severe and progressive manifestation of NF-1, requiring urgent management, especially in cases with neurological impairment [[9], [10], [11], [12]].

NF-1–related dystrophic cervical kyphosis, is considered a progressive condition and if left untreated, will lead to neural compression and myelopathy resulting in quadriparesis and sensory and sphincter malfunction [13]. Thus, surgical correction is considered the mainstay of treatment of dystrophic cervical kyphosis in patients with NF-1 [14]. Although several recent clinical series have shed light on the surgical approach in these patients [3,11,[14], [15], [16]]; but the consensus on the best surgical management is yet to be reached. According to the current literature, combined circumferential fusion is the most acceptable surgical strategy [9,17]. In addition, complications of the surgical procedures such as neurological impairment, instrument failure, further spine deformities and general adverse events (infection, deep vein thrombosis, hemorrhage and etc.) should be considered [18]. Proximal junctional failure (PJF) presenting as basilar invagination and atlantoaxial dislocation has been rarely reported after surgical correction of kyphosis [19]. We herein, report of a rare complication (basilar invagination with atlantoaxial dislocation) after correction of dystrophic cervical kyphosis in a patient with NF-1 and describe the management, surgical procedure and the pathophysiology.

2. Case report

An 11-year-old boy with NF-1 was referred to our neurospine clinic with a dorsal cervical “hump” since birth. The patient was diagnosed with NF-1 based on the multiple (>6) cafe-au-lait spots and freckles under the arms or in the groin area. The diagnosis was also confirmed by genetic testing indicating a mutation in NF-1 gene. No masses or other complications of NF-1 were present, and the neurological status was intact except for bilateral decreased muscle powers of proximal of the upper extremities (M/P = 4/5). In physical examination, the patient revealed decreased range of motion in flexion and extension as well as lateral rotation. A plain cervical radiography (Fig. 1), whole neuroaxis magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and a cervical computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 2) was requested. No abnormalities or masses were found in the neural axis considering the MRI images (Fig. 2). The cervical CT scan revealed C3 anterior wedge vertebra, C2–C4 kyphosis (85°), C2–C7 angle of 24°, incomplete C2 dense-body synostosis, left C2 intervertebral foramen expansion without any neurofibroma (Fig. 2D), and C4–C7 small vertebral bodies with irregular end-plates and posterior vertebral body scalloping. A flexion-extension lateral cervical radiography was requested, revealing a C2–C4 angle of 86° on flexion and 34° on extension (Fig. 1 B, C). Vertebral artery CT-angiogram revealed no challenging variations (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Preoperational lateral cervical radiography. A: lateral cervicothoracic standing radiography demonstrating severe dysplastic cervical kyphosis; B: lateral cervical radiography in extension demonstrating a kyphotic angle of 34°; C: lateral cervical radiography in flexion demonstrating a kyphotic angle of 86.5°.

Fig. 2.

A: Sagittal cervical T2-STIR magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrating severe cervical kyphosis and dysplastic changes; B: sagittal cervical T2-weighted MRI; C: sagittal 3D cervical computed tomography (CT) scan; D: sagittal cervical CT scan, showing non-ankylosed facet joints and the C2 intervertebral foramen; E: C2–C4 and C2–C7 angles in the sagittal cervical CT scan.

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional view of the vertebral arteries on the computed tomography angiogram demonstrating no challenging abnormalities.

The patient and his legal guardians consented to the planned procedure that included cervical traction followed by a combined surgery including the posterior and anterior release and instrumentation. The patient was admitted to our ward, and cervical traction was applied using a Gardner head clamp, starting with 5 kg of traction along with muscle relaxant for five consecutive days. Surgery was then conducted under intraoperative neuromonitoring using the motor evoked potential (MEP) and somatosensory evoked potential (SEP) starting before positioning and continuing the end of the procedure. The combined surgery was planned in 3 stages: 1. posterior release and facetectomy; 2. anterior instrumentation and fusion; 3. posterior instrumentation and fusion. Surgery was commenced with posterior C2–C6 facet release and joint cartilage shaving. Then, the anterior approach was done for complete C3–C5 corpectomy and reconstruction with iliac autografting and plate fixation, followed by posterior C2–T4 fusion. The surgery was uneventful and no changes in the MEP and SEP were recorded. A cervical Philadelphia collar was applied after surgery.

Postoperative evaluations were acceptable. On radiographic examination, the C2-C7 angle was corrected to −14° (Fig. 4). He was allowed to sit in bed two days after surgery and walked with a cervicothoracolumbar orthosis a couple of days later. During the 1-year follow-up, the patient complained of a limited craniocervical range of motion. The primary and preoperative occipito-C2 angle was 22° because of the fact that we have not extended the instrumentation to the occiput-C1 segment (Fig. 5). On further examinations, atlantoaxial dislocation (AAD), basilar invagination (BI), and upper cervical spinal cord compression were detected and marked as proximal junctional failure (PJF) (Fig. 6A). We performed the second surgery and expanded the construct to the C1 vertebra via lateral mass screw fixation (Fig. 6B). The surgery was uneventful and the postoperative evaluations demonstrated complete correction of the AAD and the BI as well as core decompression. Atlantodental interval (ADI) and ventral C1 arc in Clark zones were corrected after the second surgery (Fig. 7 A, B). In 1-year follow-up, the patients are neurologically intact and the radiologic indices are acceptable and within the normal range (Fig. 8). The work has been reported in line with the Updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines [20]. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents/legal guardian for publication and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Fig. 4.

A: Postoperative anterior-posterior cervicothoracic radiography; B: postoperative lateral cervicothoracic radiography, demonstrating the C2–C7 angle of 14°.

Fig. 5.

Sagittal cervical computed tomography scan showing the O-C2 angle of 22°.

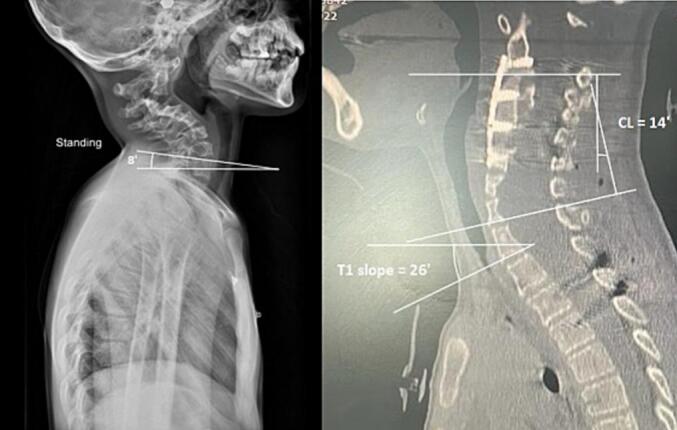

Fig. 6.

A: Preoperative standing lateral cervical radiography and T1-slope measuring 8°; B: Postoperative midsagittal cervicothoracic spinal computed tomography scan. Cervical lordosis (CL) corrected to −14° and T1-slope to 26°.

Fig. 7.

Pre- (A) and post-operative (B) computed tomography scans related to the second surgery: the atlantodental interval (ADI) and ventral C1 arc in Clark zones [32] are compared.

Fig. 8.

The final sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patient 1-year after final surgery demonstrating appropriate alignment of the cervical spine and intact spinal cord.

3. Discussion

Normal spinal curvature (cervical lordosis, thoracic kyphosis, and lumbar lordosis) is necessary for normal gait and axis of vision [21,22]. Cervical lordosis has a normal range of −40 ± 9° [[21], [22], [23]]. The most common etiologies for abnormal spinal curvature are spondylosis (in older patients), trauma, and dysplasia (as in NF-1 in younger patients) [7,24]. NF has two types, differing in mutations and symptoms [4]. The genetic basis of NF-1 has been described in the literature [8]. Besides cutaneous manifestations, osseous anomalies are common, including spinal abnormalities [4,7,8]. Dystrophic spinal curvatures are associated with soft tissue masses, severe angulation, and a higher risk of progression [8,15,25]. Therefore, severe cervical kyphosis (segmental Cobb angle ≥ 50°) in NF-1 requires special prophylactic or therapeutic management [[9], [10], [11],15,17,26]. Halo-gravity traction or orthoses have been used as less invasive treatments with minimal response. Thus, it almost always demands surgical correction when it reaches 50° [16,27].

Surgical strategies are classified as anterior-only (AO), posterior-only (PO), and combined surgery (the choice of management) [15,16,22,28]. Pseudoarthrosis, non-union, adjacent segment disease (ASD), and instrument failure are among the most common complications. The lower bone profile and higher chance of non-union in NF-1 lead to the preference for autograft bone materials [4,9,15,17]. During the combined approach, different orders of surgery have been described in the literature [[9], [10], [11],20]. In previous studies, the degree of kyphosis correction ranged from +50° to −19° without any definite goal [[9], [10], [11],15,17,26]. The expansion of the construct depends on various parameters, and junctional segments (occipitocervical and cervicothoracic) should be reserved for when absolutely necessary [17,29]. We have chosen the posterior approach as the first procedure due to critical spinal canal narrowing, the intact neurologic status, and the high risk of neurologic damage during anterior multilevel corpectomy and reconstruction. Because of dysplastic small vertebrae, posterior instrumentation of the cervical spine was challenging, and expansion of the construct into the upper thoracic segment was necessary. We also decided not to involve the occiput-C1 segments in this stage due to the normal preoperational O-C2 angle (Fig. 5) and axis of vision. Cervical lordosis (CL) was corrected to −14°. The T1-slope (normal range 21–37°) was 26° in postoperative investigations compared with 8° on preoperative imaging (Fig. 6).

In follow-up evaluations, proximal junctional kyphosis (PJK) gradually occurred, leading to PJF in 1-year follow-up. Although PJK is very rare in such cases and occurs more in AO approaches [30,31], our patient was affected. Basilar invagination was also occurred secondary to iatrogenic changes in C1-C2 facet joint [32]. We managed this complication by adding C1 to the previous construct via one side C1 lateral mass, contralateral C1 sublaminar hook, one side C3 and contralateral C4 sublaminar hook insertion, fixed with contoured rods medial to previous rods (Fig. 7). This led to the correction of the AAD and the BI and the patients remained neurologically intact. The depth of this rare case report is rather superficial, and it may not significantly contribute to the existing literature. Thus, there is a need for further research and recommendation for similar cases.

4. Conclusion

Surgical management of the cervical kyphosis in patients with NF-1 remains controversial and the surgical planning should be exclusively designed to address the spine alignment and to minimize the risk of neurological impairment. Most patients require a combined and multi-stage surgery to achieve a favourable outcome. Combined approach is the best surgical plan for correction of the deformity and restoring the spine alignment and maintains the neurological status; however, it carries the risk of PJK and PJF.

Consent

The patient and their legal guardians provided their written consent for publication of the manuscript and the case for research purposes.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were under the institutional and/or national research committee's ethical standards and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Shiraz University neurosurgery department board members supervised and approved this report on behalf of the Ethical Committee of Shiraz University of medical sciences (SUMS).

Funding information

The manuscript is the authors' own work and no funding was received.

Guarantor

Dr. Seyed Reza Mousavi.

Research registration number

1.Name of the registry:

2.Unique identifying number or registration ID:

3.Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked):

Declaration of competing interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to declare regarding the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the editorial assistance of Diba Negar Research Institute for improving the style and English of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Majid Reza Farrokhi, Email: farokhim@sums.ac.ir.

Hamid Jangiaghdam, Email: jangia@sums.ac.ir.

Fariborz Ghaffarpasand, Email: fariborz.ghaffarpasand@gmail.com.

Data availability

Data and original images in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Authors can confirm that all relevant data are included in the article and/or its supplementary information files.

References

- 1.Pinna V., Daniele P., Calcagni G., Mariniello L., Criscione R., Giardina C., et al. Prevalence, type, and molecular spectrum of NF1 mutations in patients with neuro- fibromatosis type 1 and congenital heart disease. Genes (Basel) 2019;10(9) doi: 10.3390/genes10090675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtis-Lopez C.M., Soh C., Ealing J., Gareth Evans D., Burkitt Wright E.M.M., Vassallo G., et al. Clinical and neuroradiological characterisation of spinal lesions in adults with neurofibromatosis type 1. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020;77:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsirikos A.I., Saifuddin A., Noordeen M.H. Spinal deformity in neurofibromatosis type-1: diagnosis and treatment. Eur. Spine J. 2005;14(5):427–439. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0829-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pillai S.S., Ramsheela P. Spinal deformities in neurofibromatosis 1. J. Orthop. Assoc. South Indian States. 2020;17(2):49. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S.H., Son E.S., Seo E.M., Suk K.S., Kim K.T. Factors determining cervical spine sagittal balance in asymptomatic adults: correlation with spinopelvic balance and thoracic inlet alignment. Spine J. 2015;15(4):705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogura Y., Dimar J.R., Djurasovic M., Carreon L.Y. Etiology and treatment of cervical kyphosis: state of the art review-a narrative review. J. Spine Surg. 2021;7(3):422–433. doi: 10.21037/jss-21-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prudhomme L., Delleci C., Trimouille A., Chateil J., Prodhomme O., Goizet C., et al. Severe thoracic and spinal bone abnormalities in neurofibromatosis type 1. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2020;63(4) doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.103815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ly K.I., Blakeley J.O. The diagnosis and management of neurofibromatosis type 1. Med. Clin. 2019;103(6):1035–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawabata S., Watanabe K., Hosogane N., Ishii K., Nakamura M., Toyama Y., et al. Surgical correction of severe cervical kyphosis in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1: report of 3 cases. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2013;18(3):274–279. doi: 10.3171/2012.11.SPINE12417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vigneswaran K., Sribnick E.A., Reisner A., Chern J. Correction of progressive severe cervical kyphosis in a 21-month-old patient with NF1: surgical technique and review of literature. Oper. Neurosurg. 2018;15(1):46–53. doi: 10.1093/ons/opx219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malamashin D.B., Shchelkunov M.M., Krasnikov M.A., Mushkin A.Y. Surgical correction of subaxial kyphosis in a child with type i neurofibromatosis: rare clinical case and literature review. Хирургия позвоночника. 2018;15(2 (eng)):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global, regional, and national burden of spinal cord injury, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(11):1026–1047. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00287-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taleb F.S., Guha A., Arnold P.M., Fehlings M.G., Massicotte E.M. Surgical management of cervical spine manifestations of neurofibromatosis type 1: long-term clinical and radiological follow-up in 22 cases. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2011;14(3):356–366. doi: 10.3171/2010.9.SPINE09242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J., Liu C., Wang C., Li J., Lv G., A J., et al. Early and midterm outcomes of surgical correction for severe dystrophic cervical kyphosis in patients with neuro- fibromatosis type 1: a retrospective multicenter study. World Neurosurg. 2019;127 doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.04.096. e1190-e200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crawford A.H., Gr H.C., Schumaier A.P., Mangano F.T. Management of cervical instability as a complication of neurofibromatosis type 1 in children: a historical perspective with a 40-year experience. Spine Deform. 2018;6(6):719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin T., Shao W., Zhang K., Gao R., Zhou X. Comparison of outcomes in 3 surgical approaches for dystrophic cervical kyphosis in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. World Neurosurg. 2018;111:e62–e71. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.11.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma J., Wu Z., Yang X., Xiao J. Surgical treatment of severe cervical dystrophic kyphosis due to neurofibromatosis type 1: a review of 8 cases. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2011;14(1):93–98. doi: 10.3171/2010.9.SPINE091015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crawford A.H., Lykissas M.G., Schorry E.K., Gaines S., Jain V., Greggi T., et al. Neurofibromatosis: etiology, commonly encountered spinal deformities, common complications and pitfalls of surgical treatment. Spine Deform. 2012;1(1):85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding C., Guo Y., Wu T., Wang B., Huang K., He J., et al. Atlantoaxial dislocation associated with type 1 neurofibromatosis: case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2020;143:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.07.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2023;109(5):1136. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ling F.P., Chevillotte T., Leglise A., Thompson W., Bouthors C., Le Huec J.C. Which parameters are relevant in sagittal balance analysis of the cervical spine? A literature review. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 1):8–15. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5462-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu J., Guo R., Yang C., Yan H., Wang Z., Chen Z., et al. The difference of sagittal correction of adult subaxial cervical spine surgery according to age: a retrospective study. Orthop. Surg. 2022;14(8):1790–1798. doi: 10.1111/os.13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalil N., Bizdikian A.J., Bakouny Z., Salameh M., Bou Zeid N., Yared F., et al. Cervical and postural strategies for maintaining horizontal gaze in asymptomatic adults. Eur. Spine J. 2018;27(11):2700–2709. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan L.A., Riew K.D., Traynelis V.C. Cervical spine deformity—part 1: biomechanics, radiographic parameters, and classification. Neurosurgery. 2017;81(2):197–203. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park B.-J., Hyun S.-J., Wui S.-H., Jung J.-M., Kim K.-J., Jahng T.-A. Surgical outcomes and complications following all posterior approach for spinal deformity associated with neurofibromatosis type-1. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2020;63(6):738–746. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2019.0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin H.-Y., Lin C.-C., Tsai S.-J. Neurofibromatosis type 1, severe cervical spinal kyphotic deformity, and vertebral arteriovenous fistula presenting with tetraplegia: case report and literature review. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases. 2022;8(1):1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41394-022-00544-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang H., Deng A., Guo C., Zhou Z., Xiao L. Halo traction combined with posterior-only approach correction for cervical kyphosis with neurofibromatosis-1: minimum 2 years follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021;22(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04864-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mousavi S.R., Farrokhi M.R., Eghbal K., Motlagh M.A.S., Jangiaghdam H., Ghaffarpasand F. Posterior-only approach for treatment of irreducible traumatic Atlanto-axial dislocation, secondary to type-II odontoid fracture; report of a missed case, its manage- ment and review of literature. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023;114 doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.109104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mousavi R., Farrokhi M.R., Eghbal K., Safaee J., Dehghanian A.R. Reconstruction of C1 lateral mass with an expandable cage in addition to vertebral artery preservation: presenting two cases. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2021;1-6 doi: 10.1080/02688697.2021.1978393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murlidharan S., Singh P.K., Chandra P.S., Agarwal D., Kale S.S. Surgical challenges and functional outcomes in dystrophic cervical kyphosis in neurofibromatosis-1: an institutional experience. Spine Deform. 2022;10(3):697–707. doi: 10.1007/s43390-021-00465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mousavi S.R., Liaghat A., Shahpari Motlagh M.A., Pishjoo M., Tarokh A., farrokhi M. Launching the DCER (distraction, compression, extension, and reduction) technique in basilar invagination and atlantoaxial dislocation: a preliminary report of two cases in Iran. Iran. J. Neurosurg. 2023;9(0):2. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riew K.D., Hilibrand A.S., Palumbo M.A., Sethi N., Bohlman H.H. Diagnosing basilar invagination in the rheumatoid patient: the reliability of radiographic criteria. JBJS. 2001;83(2):194. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200102000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and original images in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Authors can confirm that all relevant data are included in the article and/or its supplementary information files.