Abstract

Background

The birth plan promotes women's autonomy allowing them to express their care preferences and to participate actively in decision-making. During the Covid-19 pandemic, concerns about infection placed limitations on women's decision-making and infringed upon some of their rights. The role of the birth plan, after the pandemic, needs to be reassessed to protect women's rights and ensure high-quality maternity care.

Research aim

To explore Spanish midwives’ perspective on the principle of respect for autonomy and how this is reflected in the birth plan, and to identify aspects that can be improved in the new post-pandemic scenario.

Methods

A descriptive phenomenological study of the experiences of Spanish midwives before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic that addresses the use of the birth plan and the impact that the pandemic has had on women's rights. Individual online interviews and face-to-face focus groups were used.

Results

Prior to the pandemic, midwives felt that birth plans had problems related to the unrealistic expectations of some women as well as to a lack of awareness of their usefulness. During the pandemic, women mobilized to challenge restrictive regulations, but faced problems with information dissemination and professional coordination, leading to continued infringement of women's rights post-pandemic.

Conclusion

To enhance the effectiveness of the birth plan in supporting women's autonomy, a deliberative approach is needed, along with improvements in midwives' ethical and communication skills. The COVID-19 pandemic has created a new scenario in which the discussion about the possibility of increasing the number of birthing centres or offering home birth care funded by the public system, should be debated.

Keywords: Midwife, Labour, Childbirth environment, Relational autonomy, Qualitative research

1. Background

The Birth Plan, which was introduced into the United Sates in 1980 and Spain in 2008 [1] emerged as a response to increasing medical interventions and to pregnant women's sense of loss of agency in institutionalised childbirth, seeking to improve woman-caregiver relationships and to enhance women's birth experiences [2]. Although one cannot predict how a childbirth will progress, the birth plan is a tool that respects the principle of autonomy and therefore the right of women to make informed decisions [3]. Recognizing a woman's right to follow a birth plan implies recognizing that her autonomy in decision-making must be respected. The principle of autonomy is recognized as one of the basic bioethical principles outlined in the Belmont Report [4]. In Spain, it is enshrined as a protected right under the current legal framework by Act 41/2002 on patient autonomy [5], which stipulates, among other things, the right to receive information about interventions and treatments. In childbirth care, decision-making and its outcome, informed choice, are considered important indicators of the strength of the care relationship between a woman and her midwife or obstetrician [6]. To put the principle of autonomy into practice, decision-making can follow an informative model, in which the professional simply provides information and the woman decides, or a relational and deliberative model of decision-making [7].

Despite the recognition of the Birth Plan as a tool that reinforces women's right to make informed decisions, there has traditionally been some disagreement regarding its necessity and usefulness [[8], [9], [10]], and even some scepticism whenever it includes requests that are somewhat unrealistic [[11], [12], [13]] The Covid-19 pandemic put health services around the world, including maternity care, under great strain. During and after the pandemic, birthing facilities had to adapt to circumstances that were unexpected by both professionals and the women and their families. Preventive measures were introduced in obstetric and gynaecological services to prevent transmission and this limited informed decision-making in birth care. Some of these measures violated women's sexual and reproductive rights, including informed decision-making [[14], [15], [16]]. Studies on parental experiences highlight the fact that maternal care during the pandemic did not conform to the quality standards of the WHO [17].

Moreover, parental experiences during the pandemic revealed discrepancies between the care received and the expectations outlined by global health organizations [14,17]. Such findings emphasize the critical need for reevaluating and strengthening the role of the birth plan in safeguarding women's rights and ensuring high-quality maternity care, particularly in times of crisis.

Different studies position the midwife as the key professional in childbirth care within a woman-centred model, where the relationship of trust and shared decision-making are the central pillars of care. Therefore, and considering these challenges, this study aims to explore midwives' perspectives on the intersection between women's autonomy, the effectiveness of the birth plan in respecting maternal rights, before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. By examining midwives' perceptions, this research seeks to identify potential avenues for enhancing the utility and effectiveness of birth plans, thereby promoting greater autonomy, informed decision-making, and improved birth experiences for women following an unprecedented health crisis.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study design

The research team employed a descriptive phenomenological design to elicit insights through a combination of focus groups and individual interviews.

2.2. Participant selection

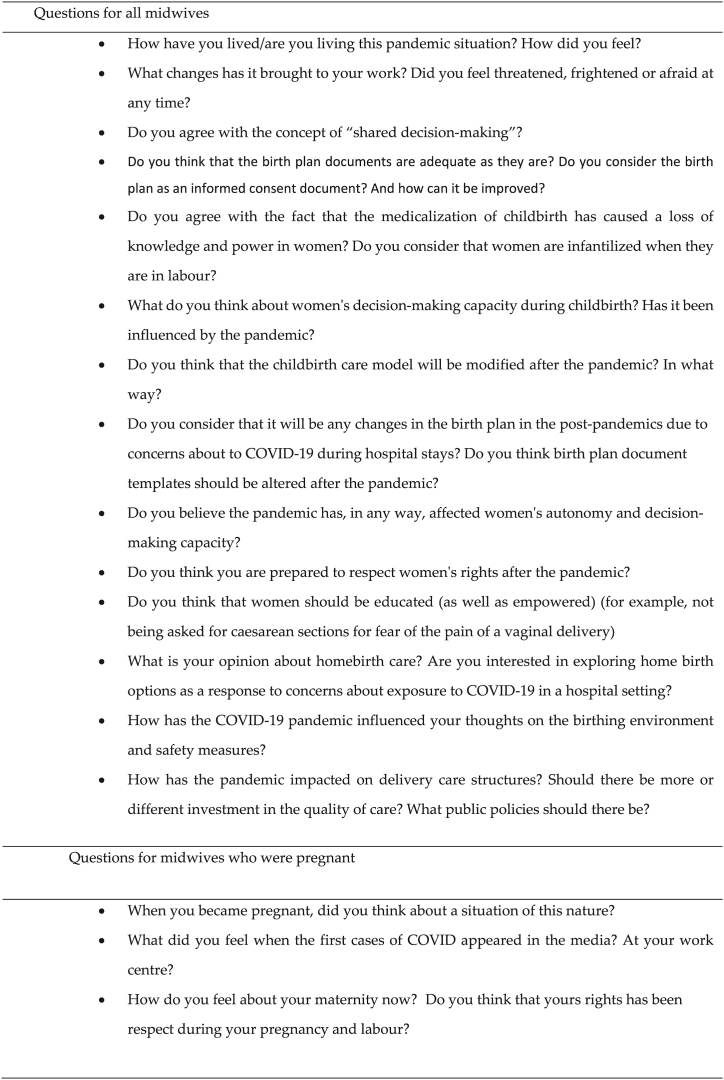

This study, situated in Spain, involved actively practicing midwives from diverse settings, including hospitals, primary care, and those involved in private practice for home births. Three focus groups with midwives in active service were conducted prior to the pandemic and were used for a secondary analysis. The primary objective of these data was to investigate how midwives perceive women's capacity for autonomy and their view of obstetric violence [18]. These focus groups also scrutinized the usefulness of birth plans concerning women's rights offering a foundation for comparison with midwives' perspectives gathered through individual interviews in both pandemic and post-pandemic contexts. The Official Barcelona College of Nursing/midwifery Professionals (Colegio de Enfermería) collaborated in the selection of participants for the focus group discussions in order to identify midwives who had been practising for more than one year and who also met the following criteria: a) Midwives who work in level II Hospitals (low and medium degree of complexity), b) Midwives who work in Level III Hospitals (hospitals with a high level of complexity) and c) Midwives working in Primary Care. Two researchers (the second and third authors) contacted the midwives via email. A total of 24 midwives, 23 females and 1 male, participated in the focus groups. (Their names have been changed to protect anonymity and maintain confidentiality). Their profiles are shown in Table 1. Additionally, Individual interviews were held with midwives during, and after, the COVID-19 pandemic. Theoretical selection criteria were established. The criteria for inclusion were that each midwife had to have been on the front line of care during the first months of the pandemic, furthermore and in order to cover as many profiles as possible, researchers search variability regarding the workplace (hospital, primary care or home care), the age of the respondent (29–60 years old), and the inclusion of midwives who had been pregnant herself during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The participants were identified using two mechanisms: First: contact via telephone and personal contacts by the researchers using "snowball sampling". The second strategy was conducted via an appeal made through the website of the Research Group. A total of 10 midwives were individualy interviewed by one research (second author) (Table 2). (The names of the interviewed women have been changed in the Table, using pseudonyms, to ensure anonymity and maintain confidentiality). All the invited individuals accepted to participate. The interview script was based on the objectives of the study and on the primary analysis of the focus groups and it incorporated aspects such as women's rights, the impact of the pandemic and the use of the birth plan. The individual interviews were conducted online because of lockdown and recorded for subsequent transcription. The interview script served as a stimulus to guide the conversation, but efforts were made to allow the conversation to flow naturally so that the midwives could feel comfortable in their online conversation (Fig. 1), each interview lasted between 40 and 60 min. The interviews took place between 2020 and 2022 and were conducted on-line using the BB Collaborate virtual platform of the University of Barcelona.

Table 1.

Profiles of the midwives who participated in the focus groups.

| Focus group A | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | Years working | Hospital/Primary Care |

| Sara | 8 | Both |

| Fiona | 40 | Both |

| Margaret | 18 | Hospital (level III) |

| Mary | 11 | Hospital (level II) |

| Celine | 25 | Hospital (level III) |

| Franchesca | 4 | Primary Care |

| Naomi | 20 | Hospital (level II) |

| Focus Group B | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | Years working | Hospital/Primary Care |

| Carol | 5 | Primary care |

| Maggie | 31 | Hospital (level III) |

| Amy | 9 | Both |

| Elisabeth | 17 | Hospital (level II) |

| Vanessa | 18 | Hospital (level II) |

| Holly | 3 | Both |

| Araminta | 12 | Primary Care |

| Alisa | 7 | Both |

| Eleonor | 4 | Both |

| Bianca | 15 | Both |

| Focus Group C | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | Years working | Hospital/Primary Care |

| Barbara | 37 | Hospital (level III) |

| Angela | 4 | Hospital (level II) |

| Hugh | 7 | Hospital (level III) |

| Cameron | 7 | Primary Care |

| Malory | 14 | Both |

| Rita | 13 | Both |

| Rachel | 4 | Hospital (level II) |

The names in this table are pseudonyms. The real names of participants have been changed to protect anonymity and maintain confidentiality.

Table 2.

Profile of participating midwives.

| Name | Age | Area of Work | Pregnant herself |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bárbara | 30 | Primary Care | Yes |

| Aurora | 32 | Hospiral Delivery Room | Yes |

| Nancy | 50 | Hospital Delivery Room Coordinator | No |

| Alice | 37 | Hospital | No |

| Antonia | 42 | Hospital Delivery Room and Home-birth care | No |

| Elisa | 45 | Hospital Delivery Room | No |

| Jennifer | 44 | Hospital Delivery Room | No |

| Jane | 45 | Hospital Delivery Room Coordinator | No |

| Maria | 29 | Home-birth care | No |

| Sara | 35 | Primary Care | No |

The names in this table are pseudonyms. The real names of participants have been changed to protect anonymity and maintain confidentiality.

Fig. 1.

Interview script.

2.3. Ethical aspects

The research was approved by the University of Barcelona Bioethics Committee (IRB00003099). The objective and ethical considerations of the study were explained to all the participants personally, in the website or by e-mail. In the case of focus groups, the informed consent forms were signed the same day of the focus groups’ discussion. Those participants who were individually interviewed were also sent the information and an informed consent form by email, which they signed and returned to the Main Researcher.

2.4. Criteria for methodological Rigor

Throughout the study, research team adhered to the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines, using them as a reference for the list of questions and in the final report [19]. In addition, research team applied quality criteria based on Calderón's framework [20]. Epistemological adequacy was considered, ensuring coherence in the research question formulation and process. Relevance was emphasized, recognizing the importance of understanding midwives' experiences regarding ethical aspects of childbirth. Validity was understood in terms of relevance and interpretivism, rather than statistical probability, focusing on participant selection and rigorous analysis to uncover meaningful and contextually transferable explanations. The transcriptions were sent to the participants for validation. Maximum variability was sought in both groups and individual interviews. Finally, the reflexivity criterion was met, acknowledging the researchers' roles as women and midwives with PhDs (second, third and fourth author), or a philosopher with a PhD (first author), as well as academics and researchers, some of whom were directly involved in the childbirth setting. The research team was led by the second author, who is a university professor, midwife, sociologist, and holds a PhD in bioethics. She has extensive experience in qualitative methodology and research in feminist and gender studies, particularly related to women's health issues. Contact with the midwives (in the focus groups) was facilitated by the third author, an experienced midwife with broad knowledge in anthropology and midwifery. Discussion groups were conducted by the first, the second and the third author. The individual interviews were conducted by the second author of the study, using the BB Collaborate virtual platform of the University of Barcelona. These considerations aimed to enhance the understanding of the research's logical perspective and generate in-depth, generalizable explanations that account for the specific contextual circumstances of the study.

2.5. Interview transcripts

The qualitative data set consisted of three focus group interview and individual interviews transcripts with a total of 34 midwives’ participants. The secondary analysis of the transcriptions corresponding to the focus group was compared with the individual interviews conducted during the pandemic and post-pandemic period to analyse any possible changes in perceptions of the use and usefulness of birth plans, and also to identify any needs and proposals for improvement.

2.6. Data analysis

Two researchers (first and second authors) conducted a thematic analysis of transcriptions using Colaizzi's approach [21]. Significant statements were identified, and keywords were established. Themes and subthemes were formulated based on meanings derived from the data. Any discrepancies that arose were resolved by the other two authors of the study. All data and analysis materials were stored securely.

3. Findings

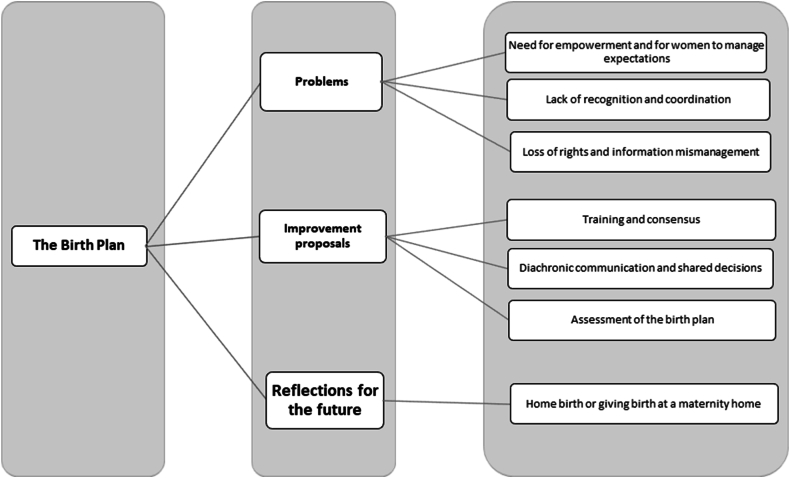

The midwives who participated in the focus groups conducted before the pandemic considered the Birth Plan as a valuable tool, although they identified various issues. The emergence of the pandemic altered the landscape, increasing the infringement of women's right to participate in decision-making. Through analysis and comparison between focus groups and individual interviews, three main aspects were identified: 1) problems, 2) improvement proposals, and 3) reflections for the future. The problems section has been divided into three categories, while the improvement section contains three categories too. The future improvement section is a comprehensive category intended to provide elements for reflection on the childbirth care model in the post-pandemic (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Themes related to rethinking the birth plan.

3.1. Problems arising from the application of birth plans

-

a.

Need for empowerment and for women to manage expectations.

Before the pandemic, midwives highlighted the fact that while historically women had relied on them and their expertise as professionals, in recent decades they have sought greater autonomy in their role in society, exercising their ability to educate and inform themselves and demanding to make decisions about their childbirth.

“I think it is a time of change because women now have a higher level of education, they know more, they have better training. (…) Women’s society is changing and they want to empower themselves, they want to do things, and this is what they are requesting from us.” (Alisa, Focus group B)

In this regard, the midwives stated that women who used the birth plan before the pandemic usually had more idealized expectations of childbirth than those who did not. However, quite often these expectations were not met because of the unpredictable nature of childbirth or a lack of adjustment on the part of the professional. Consequently, the women were left feeling frustrated:

“Now some of them come to us with a birth plan that they almost put in our mouths, and they tell us that they want this, and they want that, and I think that that is fantastic. But then again, they also come to us with a list of things they want and which they want to adapt to, and that frustration is very significant because they expect something that we might not be able to give them.” (Fiona, Focus group A)

After pandemic, the midwives said that there was greater empowerment of women during the pandemic, and in some places, they were able to reverse the restrictive regulations at some centres that violated women's rights under the birth plan, such as the presence of a partner in the delivery room, by organising themselves and protesting:

“(…) partners are allowed in and this is partly due to the pressure of the women, you know? The voice of women who do not want to lose their empowerment is very important, and when, at one point, after news got around and it was said that partners would not be allowed into the delivery room … a group of pregnant women sprang into action and said that they would not allow this and that they would take all appropriate measures. Thanks to the strength of the women, this accompaniment was not lost.” (Antonia. Individual interview).

-

b.

Lack of recognition and coordination

Before the pandemic, midwives said that there were coordination problems and tensions between primary care and hospital care, and that there were discrepancies regarding compliance with the birth plan. Hospital midwives think that primary care idealises childbirth, while primary care sees hospital childbirth as an experience of unavoidable suffering:

“I have had conversations with professionals in the delivery room, I’m in primary care, and they say to you reluctantly: “let us see what you are doing in primary care”, especially since the birth plan is being used a lot and they say “you have a problem, you are idealising childbirth and people come here thinking that childbirth is a very beautiful thing”, and that the reality is that they will suffer..” (Carol. Focus Group B)

The midwives felt that some gynaecologists downplayed the importance of the birth plan:

” I think that some gynaecologists laugh at the birth plan and as a collective of midwives it is hurtful to see a colleague being laughed at”. (Rachel, Focus Group C)

The pandemic intensified the conflict between gynaecologists and midwives. The midwives mentioned their perception that gynaecologists were careless in their work and referred to disagreements regarding COVID-19 safety measures:

“I think that we have taken a backward step at our centre because a division has been created between professionals. I think there’s been a loss of trust: the midwives are here and the gynaecologist are there, what I mean by that is that unfortunately, this has not helped us find a way of working together. (…) Perhaps the gynaecologists thought that some changes needed to be made which the midwives did not approve, such as husbands not entering the delivery room, and this created a rift between the two groups”. (Jennifer, individual interview).

-

c.

Loss of rights and information mismanagement

In the interviews conducted during the pandemic and the post-pandemic period, there was disagreement about respect for women's rights during the health emergency. While some midwives reported a lack of attention to maternity services from health organizations, others experienced it as a bubble of isolation and tranquillity at a time of maximum upheaval in the hospital.

“I think that we did the best that we could, but I have the feeling that women have been cast aside as if they were not important and were sent to another hospital. (…). Above all, I have met women suffering from postpartum sadness, postpartum depression because of this situation; and that group is very vulnerable, and that must be changed.” (Aurora, individual interview)

“They felt panic, but once they went into labour and were immersed in this situation, they saw that we were working in a natural way and things distanced themselves somewhat from the bubble we were all living in.” (Jennifer, individual interview).

In any case, it is unanimously agreed that the pandemic led to a generalised loss of rights. Midwives attribute this loss of women's rights to restricted access to information and to limitations on informed decision-making:

" … we are returning to a situation where they are not allowed to decide … We have significantly increased the number of inductions. Now, from 41 weeks onwards, it is being proposed to the woman that the best option is to be induced … It all depends on how the message is given to them, how the professional presents it, if a message is given like 'yes, indeed, your child is already in danger, you are 41 weeks pregnant, that is the best option' … Can we say that the woman decides? Or are we coercing her due to the way we inform her about the reason for the induction?" (Elisa, individual interview)

In some cases, other more specific aspects related to logistics and the type of care were added into the mix. In some geographical areas, privately funded centres were closed and women, despite having paid for the care, eventually had to go to a publicly funded centre to give birth. The women who were affected by this saw it as a loss of their rights. This situation was created during the pandemic and the midwives say it has continued into the post-pandemic period:

“(…) if they do feel that they have lost rights, it is because in some cases they may have lost the option of being in a single room (…) And I think they also feel the loss of rights because they would have been admitted for four days in the privately financed health centre but when it closes, here at the public health centre they are discharged early or within 48 hours” (Antonia, individual interview)

According to the midwives, this meant a return to a paternalistic model of care. They believe that rights that had already been well consolidated before the pandemic have been lost, especially those relating to the respect for women's autonomy. There has been a regression towards a biomedical model which undermines the centrality of women.

“I believe that in the face of unknown situations, we are now taking a backward step, and we have seen a return to the biomedical model. Yes, more paternalist. (…) In this and speaking of pregnant women, there was a fairly humanised model of midwifery care in our delivery room before the pandemic, and the voice of the pregnant women really carried a lot of weight. We now find ourselves at a weak moment, because once again there is a confrontation between the vision of the obstetrician and that of the midwife (…).” (Nancy, individual interview).

The midwives cite some possible aspects that ought to have been respected during the pandemic to prevent this loss of rights. They highlight the need to provide quality information as well as the need to update ethical and communication aspects to ensure that the information is not biased, especially at a time when safety and fear were so prevalent.

Respect for women's autonomy is one of the constant demands that we hear from midwives, both in the pre-pandemic focus groups and in individual interviews during and in the post-pandemic period.:

“You are informing the woman, but perhaps that information coerces her somehow, don’t you think? This happens in the delivery room: there are several labour rooms in the area of delivery room, and they hurry because they need space. And then the information that we give them and the consent we get is not real. Because when you are saying something to that woman, you are putting her under pressure.” (Malory. Focus Group C),

I think there has been a loss of rights, a loss of respect towards women; yes, but well, it's not a situation that only comes from the Covid pandemic, because lately, we have seen a significant decrease in respect for rights when it comes to women in labour. (Elisa, Individual interview)

3.2. Proposals for improving the birth plan model

Several proposals for improving the birth plan had already been made in the pre-pandemic focus group discussions and these were expanded upon and referred to during the interviews conducted during and after the pandemic. These proposals have been grouped into four categories with a final section that contains reflections for the future.

-

a.

Training and consensus

The first proposal is to increase the number of training sessions for professionals. Midwives favour training that prioritizes the emotional, ethical, and communicative dimension of childbirth rather than focusing solely on its biological factors. The aim of this training should be to raise awareness among professionals of the importance of valuing the birth plan as a dialogic process:

“(…) I think that we are severely lacking in education within this field, that we haven’t been taught how to treat patients, don’t you agree? And, well, I don’t know, but the training we received was all biological rather than emotional” (Alisa, Focus Group B)

A second proposal is to reach a consensus and review the documents of the birth plan with the healthcare team to offer realistic proposals adapted to the real conditions of each centre, and thus prevent women from requesting options that cannot be offered:

“(…) besides this birth plan is mandatory and it must be agreed with the team because otherwise they might ask for things that cannot be offered to them afterwards”. (Malory, Focus group C)

However, training and consensus on the birth plan among professionals will not be enough if the women are not involved, empowered, and given responsibility for preparing and delivering the document:

“They should not have to ask you for it, they must give it. Women should be responsible for their own health” (Naomí. Focus Group A)

-

b.

Diachronic communication and shared decisions

Elaborating further on the vision of the birth plan as a dialogic process, the midwives suggested that the birth plan should be seen as more than just a simple checklist:

“it’s not just about asking for it and then filing it out because that is a bit like a checklist” () (Vanessa, Focus Group B)

The midwives stress the importance of having clear and comprehensive communication throughout the birth-planning process. The woman should be able to express her preferences and to assume the leading role together with her partner. There is an emphasis on the need for midwives to possess communication skills and for the women to participate actively at all stages of the process:

“The information must be truthful and complete with real possibilities; what we want is for her to experience a moment that is very important in her life, one that she and her partner need to experience to the greatest possible extent.” (Malory, Focus Group C)

On the other hand, the preparation of the birth plan must be a diachronic process rather than a synchronic act:

“(…) If you describe this as a journey, the person has a better experience of it and sees it as more than just a matter of choosing” (Araminta, Focus Group B)

-

c.

Assessment of the birth plan

The midwives highlighted the importance of analysing the birthing process once it has ended as this allows the woman to evaluate the monitoring that she has received and the connection between her expectations and the end result. The possibility of auditing the number of delivery plans received and the degree of compliance with them was also raised:

“(…) this would not happen if there was an audit. It is the same as when you go to buy clothes, for example in Zara and you press the “face” button, the happy “face”, the unhappy “face”, so why shouldn’t there be an application that says “Excuse me, would you like to rate me?” (Alisa, Focus Group B)

3.3. Reflections on the future

-

a.

Home birth or giving birth at a maternity home.

During the pandemic, changes at the birthing centres led to concerns about how the process would unfold. In Spain, some hospitals closed their birthing rooms and births were concentrated in only a few centres. The midwives said that that most of the women adapted to these changes and accepted them.

“And on the other hand, there were the women who perhaps expected some sort of specific care for their birth at a privately funded centre and since it closed because of the pandemic, they came to the public financed centre run by the national health system, and many of them said initially " I have to come here, but it was not what I had planned, and I don’t know what is going to happen … ". But when you explained it to them and they saw that everything followed its course, the birth was treated in a normal way and that therefore things went smoothly …, everybody accepted it in a very natural way (…)”. (Antonia, individual interview)

However, all the women did not accept things in this way; there was an increased demand for home deliveries during and immediately after the pandemic. Women felt safer at home than in hospitals, which were a potential source of COVID-19 infection. This led some midwives to call for the woman's right to choose the place of birth and for providing public funding whichever was the woman's choice, as long as the obstetric conditions allowed it, as home birth care is not publicly funded in Spain at present. As a result, they believe that changes relating to the choice of birth environment should be introduced in order to move in that direction. The words of one labour ward supervisor are one example of this way of thinking:

“I have a number of midwives in my team who have done the home birth course. (…). These midwives say that they have had more demand from women who wanted to give birth at home (…). There has been an increase in demand and, although they had been monitoring and planning to give birth in hospital up to then, they are now considering giving birth at home (…).” (Maria, individual interview)

Furthermore, the midwives propose introducing the birthing centres model in order to ensure a more respectful and more woman-centred care. The midwives said that this model, which is still in its infancy in Spain, suffered a setback during the pandemic:

“(…) It might be a good time to promote this model, which we seemed to be heading in this direction, towards birthing centres located outside hospital settings with an easy connection. This is the model that I think we should work on. Low and medium risk pregnancies handled by midwives so they can give birth in a safe place but outside the hospital environment. And just going to hospital for high-risk pregnancies and childbirths”. (Nancy, individual interview)

The midwives believe that the pandemic has left us with some things to reflect on for the future, and they expressed their concern at the consolidation of some losses and an awareness of issues that must still be addressed:

“We will never go back to being as permissive or as interventionist as we were at the time of pandemic. We will have to search for the middle ground, but we will also have to include the voices of women and consider what women feel and express in these decisions.” (Sara, individual interview)

4. Discussion

During the pandemic, some women adopted resilient strategies and, exercising their autonomy, made very important decisions about how or where they wanted to have their births attended to; these included requiring the presence of companions or opting for home births for fear of infection, and especially to get the type of assistance they wanted. The midwives highlight the fact that some gynaecologists minimised the importance of the birth plan, which led to conflicts of loyalty and understanding between obstetricians and midwives [22].

The midwives believe it is essential to provide information and obtain explicit consent during childbirth care, while respecting the women's decision-making capacity [23]. However, they consider that it is important not to generate unrealistic expectations and to avoid manipulating the women's decisions for the benefit of the professionals. In addition, it is essential to reach a consensus with the entire team on the content of the birth plan, both in the hospital and in primary care, in order to make sure that the requests are feasible [24,25].

To empowerment of women, midwives play an essential role in providing emotional accompaniment to women during childbirth and in providing them with appropriate [26] and realistic information about the process [22,27]. To achieve this, the interviewed midwives propose three key strategies: 1) "training and consensus” 2) "diachronic communication and woman-centred care" and 3) an "assessment of the birth plan". They recognize the importance of having communication skills to provide clear and non-directive information during childbirth and they emphasize the need to improve the training of professionals in this aspect [28,29].

The birth plan constitutes a tool for empowerment and education for women allowing them to express their preferences and to participate in decisions related to their healthcare [30]. Halfdansdottir et al. [31], define autonomy in relation to the place of birth, recognizing that any woman who receives comprehensive information on the risks and benefits of her options—and is free from internal or external coercive factors—gains significant decision-making power along with substantial responsibility. In Spain, home birth is not covered by the public health system. Women who choose to give birth at home must arrange a private service, usually through midwives practicing independently of the healthcare system [32]. As a result, women face external, economic pressures that restrict their ability to exercise autonomy in choosing where their birth will be attended.

Currently, there are some discrepancies about the usefulness of the birth plan as it can occasionally generate unrealistic and idealized expectations, and with it a certain amount of frustration [33]. However, some studies [34,35] show that woman-centred care, which takes into account the cultural and emotional aspects of care, and in which midwives have sufficient time to provide relationship-based care, improves the quality-of-care experiences and contributes to a sense of personal security. It is within this relational care that respect for autonomy takes on meaning.

The midwives in this study argue that the development of the birth plan should be a communicative process between the professionals and the women, in which a bond of trust and respect for the woman's autonomy is established. In the post-pandemic scenario, they say that a process of compliance and follow-up of the birth plan should be considered as a diachronic journey that spans the period from prepartum to postpartum in which decisions are personalised, and women's participation encouraged [22]. As other studies have reported [11,22,30,36], the midwives interviewed believe that it is essential to understand that the birth plan goes beyond being a pre-delivery administrative checklist. It is a participatory process based on a relational model of care and decision making. The aim is to establish effective communication, build mutual trust and ensure that decisions are informed and respected throughout the delivery process. Several authors [27,33] have stressed the importance of equipping professionals with training in communication skills. Greater inclusion of bioethics knowledge in the training of both midwives and other professionals involved in childbirth care would be desirable.

Audits are recommended to evaluate the birth plan process, including the correlation between initial expectations and birth outcomes, as well as the collection of information upon arrival at the hospitals [28,32]. In this regard, it would be of interest to conduct a future evaluation of women's satisfaction with the information received during the preparation of the birth plan, its correlation with obstetric outcomes and especially a qualitative assessment of the care relationship models received.

The results of this study should be interpreted considering the following limitations: First, the difficulties in contacting and conducting interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic and immediately afterward; some midwives became ill and required hospitalization, which created a high emotional burden during the interview. Second, the online interviews conducted during the pandemic and post-pandemic period do not allow for the same richness in capturing "non-verbal" communication that the previously conducted group interviews allowed. Finally, due to the nature of the design and the lack of a representative sample, the study's findings cannot be extrapolated to other contexts.

5. Conclusions

The birth plan supports women's rights and respect for their autonomy. Midwives play an essential role in understanding and respecting the experiences of each woman, but in the use of birth plan, it is important to improve communication, both between the various professionals in the teams and between professionals and women. To optimise the utility of the birth plan, it is necessary to use a deliberative and participatory approach, and it is also needed to strengthen ethics and communication skills and improve the level of trust.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a new scenario, and this has forced us to reflect on the conditions under which birthing should be attended. Women have made decisions regarding the place of childbirth. The environment where births take place and the possibility of increasing the number of birthing centres or the option of home births being financed by the public system should be part of the current debate in Spain.

Funding and Acknowledgements

The publication of these results is thanks to Grant PID2022-140179OB-100 funded by Spanish MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and, “ERDF A way of making Europe”, by the “European Union”. All of authors thank the midwives for their participation and time dedicated to the research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Júlia Martín Badia: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Josefina Goberna-Tricas: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Noemí Obregón-Gutiérrez: Visualization, Resources, Investigation, Data curation. Ainoa Biurrun-Garrido: Writing – original draft, Validation, Investigation.

Declaration of competing interest

X The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.-Sanidad . Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; Madrid: 2008. Estrategia de atención al parto normal del Sistema Nacional de Salud. [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeBaets A.M. From birth plan to birth partnership: enhancing communication in childbirth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017. Jan;216(1):31.e1–31.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sánchez-García M.J., Martínez-Rojo F., Galdo-Castiñeiras J.A., Echevarría-Pérez P., Morales-Moreno I. Social perceptions and bioethical implications of birth plans: a qualitative study. Clin. Ethics. 2021;16(3):196–204. doi: 10.1177/1477750920971798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research . 1978. Belmont Report. Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. United States. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ley 41/2002, de 14 de noviembre, básica reguladora de la autonomía del paciente y de derechos y obligaciones en materia de información y documentación clínica. BOE 274 de 15/11/2002. Modified 01/03/2023.

- 6.Niles P.M., Baumont M., Malhotra N., et al. Examining respect, autonomy, and mistreatment in childbirth in the US: do provider type and place of birth matter? Reprod. Health. 2023;20:67. doi: 10.1186/s12978-023-01584-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emanuel E.J., Emanuel L.L. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992 Apr 22-29;267(16):2221–2226. PMID: 1556799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmadpour P., Moosavi S., Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S., Jahanfar S., Mirghafourvand M. Effect of implementing a birth plan on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1) doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-05199-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mirghafourvand M., Mohammad Alizadeh Charandabi S., Ghanbari-Homayi S., Jahangiry L., Nahaee J., Hadian T. Effect of birth plans on childbirth experience: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Pract. Aug. 2019;25(4) doi: 10.1111/ijn.12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biescas H., Benet M., Pueyo M.J., Rubio A., Pla M., Pérez-Botella M., Escuriet R. A critical review of the birth plan use in Catalonia. Sex Reprod Healthc. Oct. 2017;13:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welsh J.V., Symon A.G. Unique and proforma birth plans: a qualitative exploration of midwives' experiences. Midwifery. 2014;30(7):885–891. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitford H.M., Entwistle V.A., van Teijlingen E., Aitchison P.E., Comm Ed C., Davidson T., Humphrey T., Tucker J.S. Use of a birth plan within woman-held maternity records: a qualitative study with women and staff in northeast scotland. Birth. 2014;41(3):283–289. doi: 10.1111/birt.12109. Sep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decoster B. Pushing for empowerment: the ethical complications of birth plans ‘pushing for empowerment: the ethical complications of birth plans’. Janus Head. 2019;17(1):72–92. http://janushead.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/JH-DECOSTER-FINAL-1.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goberna-Tricas J., Biurrun-Garrido A., Perelló-Iñiguez C., Rodríguez-Garrido P. The covid-19 pandemic in Spain: experiences of midwives on the healthcare frontline. Intl J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6516. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126516. Jun 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biurrun-Garrido A., Brigidi S., Mena-Tudela D. Perception of Health sciences and feminist medicine students about obstetric violence. Enfermeria Clinica. 2023;33(3):234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2023.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chmielewska B., Barratt I., Townsend R., Kalafat E., van der Meulen J., Gurol-Urganci I., O'Brien P., Morris E., Draycott T., Thangaratinam S., Le Doare K., Ladhani S., von Dadelszen P., Magee L., Khalil A. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(6):e759–e772. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lalor J.G., Sheaf G., Mulligan A., Ohaja M., Clive A., Murphy-Tighe S., Ng E.D., Shorey S. Parental experiences with changes in maternity care during the Covid-19 pandemic: a mixed-studies systematic review. Women Birth. 2023;36(2):e203–e212. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2022.08.004. Ma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martín-Badia J., Obregón-Gutiérrez N., Goberna-Tricas J. Obstetric violence as an infringement on basic bioethical principles. Reflections inspired by focus groups with midwives. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(23) doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312553. Nov 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calderón C. Criterios de calidad en la investigación cualitativa en salud (ICS): Apuntes para un debate necesario. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica. 2002;76:473–482. https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1135-57272002000500009 Retrived from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrow R., Rodriguez A., King & Nigel. Colaizzi's descriptive phenomenological method. Psychol. 2015;28(8):643–644. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/26984/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westergren A., Edin K., Walsh D., Christianson M. Autonomous and dependent–The dichotomy of birth: a feminist analysis of birth plans in Sweden. Midwifery. 2019;68:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2018.10.008. Jan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall H., Fooladi E., Kloester J., Ulnang A., Sinni S., White C., McLaren M., Yeganeh L. Factors that promote a positive childbearing experience: a qualitative study. J. Midwifery Wom. Health. 2023;68(1):44–51. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13402. Jan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higuero-Macías J.C., Crespillo-García E., Manuel Mérida-Téllez J., Martín-Martínez S.R., Pérez-Trueba E., Mañón J.C., Leo D. Influence of brith plans on the expectations and satisfaction of mothers. Matronas Prof. 2013;14(3–4):84–91. https://www.federacion-matronas.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/original-planes-de-parto.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Molina Fernández M.I. University of Barcelona; 2014. Expectativas y satisfacción de las mujeres ante el parto. Diseño y eficacia de una intervención educativa como elemento de mejora. Thesis. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coates D., Donnolley N., Foureur M., Thirukumar P., Henry A. Factors associated with women's birth beliefs and experiences of decision-making in the context of planned birth: a survey study. Midwifery. May. 2021;96 doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.102944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Divall B., Spiby H., Nolan M., Slade P. Plans, preferences or going with the flow: an online exploration of women's views and experiences of birth plans. Midwifery. 2017;54:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.07.020. Nov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gijón García N. Plan de parto: nomenclatura, toma de decisiones e implicación de los profesionales sanitarios. MUSAS: Revista de Investigación en Mujer, Salud y Sociedad. 2016;1(2):35–51. doi: 10.1344/musas2016.vol1.num2.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Molina Fernández I., Muñoz Sellés E. El plan de parto a debate: ¿qué sabemos de él? Matronas Profesión. 2010;11(2):53–57. https://www.federacion-matronas.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/vol11n2pag53-7.pdf Retrived from: [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boadas-Xirgu N., Badosa-Yuste E., Conejero-Carceles L., Martí-Mesa D., Martí-Lluch R. El plan de Nacimiento , según las madres, mejora el conocimiento del proceso de parto y la comunicación con las profesionales. Matronas Prof. 2017;18(4):125–132. https://www.federacion-matronas.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/original-plan-nacimiento-1.pdf Retrived from: [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halfdansdottir B., Wilson M.E., Hildingsson I., Olafsdottir O.A., Smarason A.K., Sveinsdottir H. Autonomy in place of birth: a concept analysis. Med Health Care Philos. 2015 Nov;18(4):591–600. doi: 10.1007/s11019-015-9624-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alcaraz-Vidal L., Escuriet R., Sàrries Zgonc I., Robleda G. Planned homebirth in Catalonia (Spain): a descriptive study. Midwifery. 2021;98 doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.102977. July. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Megregian M., Emeis C., Nieuwenhuijze M. The impact of shared decision-making in perinatal care: a scoping review. J. Midwifery Wom. Health. 2020;65(6):777–788. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alliman J., Phillippi J.C. Maternal outcomes in birth centers: an integrative review of the literature. J. Midwifery Wom. Health. 2016;61(1):21–51. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niles P.M., Baumont M., Malhotra N., et al. Examining respect, autonomy, and mistreatment in childbirth in the US: do provider type and place of birth matter? Reprod. Health. 2023;20:67. doi: 10.1186/s12978-023-01584-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitford H.M., Hillan E.M. Women's perceptions of birth plans. Midwifery. 1998;14(4):248–253. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(98)90097-3. PMID: 10076320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]