Abstract

In the veterinary field, the utility of disease-identification models that use comprehensive circulating microRNA (miRNA) profiles produced through measurements based on next-generation sequencing (NGS) remains unproven. To integrate NGS technology with automated machine learning (autoML) to create a comprehensive circulating miRNA profile and to assess the clinical utility of a disease-screening model derived from this profile. The study involved dogs diagnosed with or being treated for various diseases, including tumors, across multiple veterinary clinics (n = 254), and healthy dogs without apparent diseases (n = 91). miRNA was extracted from EDTA-treated plasma, and a comprehensive analysis was conducted of one million reads per sample using NGS. Then autoML technology was applied to develop a diagnostic model based on miRNA. Among these models, the one with the highest performance was chosen for evaluation. The diagnostic model, based on the comprehensive circulating miRNA profile developed in this study, achieved an AUC score of 0.89, with a sensitivity of 85 % and a specificity of 88 % for the disease samples. The miRNA-based diagnostic model demonstrated high sensitivity for disease groups and has the potential to be an effective screening test. This study indicates that a comprehensive miRNA profile in dog plasma could serve as a highly sensitive blood biomarker.

Keywords: Automated machine learning, Canine, microRNA, Next-generation sequencing

1. Introduction

Some diseases in dogs progress slowly and exhibit minimal or elusive signs in their early stages (Flory et al., 2023). Determining the presence of such diseases requires extensive testing and specialized knowledge. However, only a limited number of facilities are capable of performing such advanced testing, which may delay diagnosis. Furthermore, even with sophisticated equipment, early detection of the disease is often not possible.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small RNAs that regulate the expression of complementary messenger RNAs (Ambros, 2004), playing crucial roles in various cellular processes, such as cell differentiation and apoptosis, by regulating gene expression (O'Brien et al., 2018). They have garnered attention in veterinary medicine, suggesting their potential as biomarkers in companion and industrial animal medicine (Chen et al., 2022; Bai et al., 2019).

Recently, the clinical utility of a lung cancer discrimination model, based on a comprehensive circulating miRNA profile constructed through the integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) and automated machine learning (autoML), has been reported in human medicine (Inagaki et al., 2023). Conversely, in the veterinary field, previous studies have not yet demonstrated the clinical utility of disease-identification models constructed using comprehensive miRNA profiles.

Therefore, we evaluated whether a diagnostic model based on canine plasma miRNA profiles, developed through the combination of NGS technology and AutoML, could serve as a testing method capable of detecting physical abnormalities at an early stage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample collection

Blood sample residues were collected for clinical testing from dogs at seven veterinary hospitals, including the University of Tokyo Animal Medical Center, Kagoshima University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Animal Medical Center, and Nippon Veterinary and Life Science University Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, from January 2022 to January 2023. The majority of these dogs were undergoing veterinary treatment. Written consent for the use of these specimens for research purposes was obtained from the owners. The study included 345 dogs of various ages and health statuses. Through physical examinations, blood tests, histological examinations, cytology, and chest X-rays, these dogs were categorized into two groups: a disease group (254 animals) and a healthy group (91 animals) displaying no apparent abnormalities.

2.2. Blood sample collection and miRNA extraction from plasma

Blood samples were immediately anticoagulated using EDTA blood-collection tubes (MiniCollect® II EDTA-2K, Sekisui Medical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) following collection with a syringe, after which plasma was separated and aliquoted into cryotubes. Then the plasma samples were stored at –80 °C until miRNA extraction. RNA samples, containing miRNA, were extracted from the plasma using an RNA extraction kit (Maxwell® RSC miRNA from Tissue or Plasma and Serum Kits, Promega Corporation, WI, USA). Total miRNA concentrations in the RNA samples were measured using an miRNA quantification kit (QubitTM microRNA Assay Kits, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA, USA). These samples were preserved at –80°C until ready for NGS library preparation.

2.3. NGS library preparation and NGS

The miRNA library was assembled using an automatic pipetting machine (Agilent Bravo NGS, Agilent Technologies Inc., CA, USA). The distribution of library sizes was assessed through automated electrophoresis (TapeStation system High Sensitivity D1000, Agilent Technologies Inc., CA, USA). The pooled samples were sequenced on an NGS system (Ion S5 system, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA, USA). The sequencing data were aligned to miRBase v21, an miRNA database curated by researchers at The University of Manchester.

2.4. miRNA data normalization and production

To adjust for variation in library size, the read counts of each sample were tallied and normalized to reads per million (RPM), followed by log2 transformation (Campbell et al., 2015). miRNAs not detected in the training dataset were removed, filtering to include only those miRNAs with at least one read in each profiled sample.

2.5. Screening of a disease-differentiation model using autoML

The AutoML platform DataRobot (DataRobot, Inc., MA, USA) was used for the construction and screening of diagnostic models. From the miRNAs with quantifiable values in all samples, 70 types with significant quantities were selected as features for model construction. Using DataRobot's autopilot function, which enables fully automatic model construction, we systematically developed a model tailored for prediction. Among the models generated, the one demonstrating superior performance through five-fold cross-validation was chosen. The area under the curve (AUC) served as the metric for evaluation. The performance of the optimal model was subsequently assessed on the validation dataset.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The AUC was calculated using the statistical software R (version 4.0.3). Subject characteristics and diagnostic performance were analyzed using Welch's t-test for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Model performance, including sensitivity and specificity, was evaluated with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) determined using the Wilson score method. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was conducted to calculate AUC values.

3. Results

3.1. Subject characteristics

Table 1 displays the detailed characteristics of the subjects in this study, which included a total of 345 dogs. The sex distribution included 51 males, 115 castrated males, 38 females, and 141 spayed females. The study included 48 mixed breeds, 46 toy poodles, 46 miniature dachshunds, 22 chihuahuas, and 44 other breeds. The cohort was divided into 254 dogs in the disease group and 91 in the healthy group. Comprehensive NGS analysis was performed on both groups to generate miRNA expression profiles, further divided into training and validation datasets. The training dataset included 180 samples from the disease group and 64 from the healthy group, with the diseases listed in Table 2. The validation dataset contained 74 samples from the disease group and 27 from the healthy group, including the diseases in Table 3. In the validation dataset, the disease group was significantly older than the healthy group (Welch's t test, p < 0.05), with no significant differences observed between sex and disease status (Fisher's exact test, p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of disease and healthy subjects in the training and validation datasets.

| Characteristics | Training set |

Validation set |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Healthy | Disease | Healthy | |

| Age, months | 7–205 | 8–205 | 6–266 | 28–180 |

| Mean(median) | 130.2(137) | 99.6(96.5) | 138.7(143.5) | 104.6(98) |

| Sex, n (%) | 180 | 64 | 74 | 27 |

| IM | 22(12.2) | 15(23.4) | 10(13.5) | 4(14.8) |

| CM | 66(36.7) | 20(31.3) | 18(24.3) | 11(40.7) |

| IF | 17(9.4) | 11(17.2) | 6(8.1) | 4(14.8) |

| SF | 75(41.7) | 18(28.1) | 40(54.1) | 8(29.6) |

IM = intact male; CM = castrated male; IF = intact female; SF = spayed female. The study involved 345 dogs, divided into training and validation datasets. The training dataset included 180 diseased and 64 healthy dogs, while the validation dataset included 74 diseased and 27 healthy dogs. A significant age difference was observed between diseased and healthy dogs in both datasets (Welch's t-test, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Disease types in the training dataset (n = 180).

| Malignant tumor | 110 | Diseases other than tumors | 70 |

| Urinary tract malignant tumor | 42 | Chronic enteropathy | 7 |

| Lymphoma | 28 | Immune-mediated hemolytic anemia | 5 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 8 | Acute Gastroenteritis | 4 |

| Leukemia | 5 | Immune-mediated arthritis | 4 |

| Nasal and paranasal tumors | 5 | Immune-mediated thrombocytopenia | 4 |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 3 | Rectal polyp | 3 |

| Melanoma | 3 | Diabetes | 3 |

| Primary lung cancer | 3 | Pancreatitis | 3 |

| Angiosarcoma | 2 | Hyperlipidemia | 2 |

| Histiocytic sarcoma | 2 | Mitral regurgitation | 2 |

| Others | 1 each | Others | 1 each |

Urinary tract malignant tumors, including bladder, urothelial, and prostate cancers; adenocarcinomas, including cancers of the small intestine, thyroid, apocrine glands, salivary gland, and lung; other malignant neoplastic diseases (nine types) including brain tumors, mast cell tumors, and liver cancer; other non-malignant neoplastic diseases (33 types) including cystitis and cholecystitis.

Table 3.

Disease type in the validation dataset (n = 74).

| Malignant tumor | 43 | Diseases other than tumors | 31 |

| Urinary tract malignant tumor | 15 | Chronic enteropathy | 5 |

| Lymphoma | 9 | Acute gastroenteritis | 3 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 5 | Epileptic seizure | 2 |

| Nasal and paranasal tumors | 3 | Immune-mediated hemolytic anemia | 2 |

| Melanoma | 2 | Others | 1 each |

| Others | 1 each |

Urinary tract malignant tumors, including bladder, urothelial, and prostate cancers; adenocarcinomas, including cancers of the small intestine, thyroid, apocrine glands, salivary gland, and lung; other malignant neoplastic diseases (nine types) including brain tumors, mast cell tumors, and liver cancer; other non-malignant neoplastic diseases (19 types) including cystitis and cholecystitis.

3.2. Diagnostic model screening using miRNA

AutoML facilitates the creation of machine learning (ML) models without the need for extensive coding or manual adjustment of hyperparameters (Papoutsoglou et al., 2021). A miRNA-based diagnostic model was developed to determine the presence or absence of disease within the training dataset, which included 180 samples from the disease group and 64 samples from the healthy group, using AutoML technology. Seventy miRNAs were utilized to construct this diagnostic model.

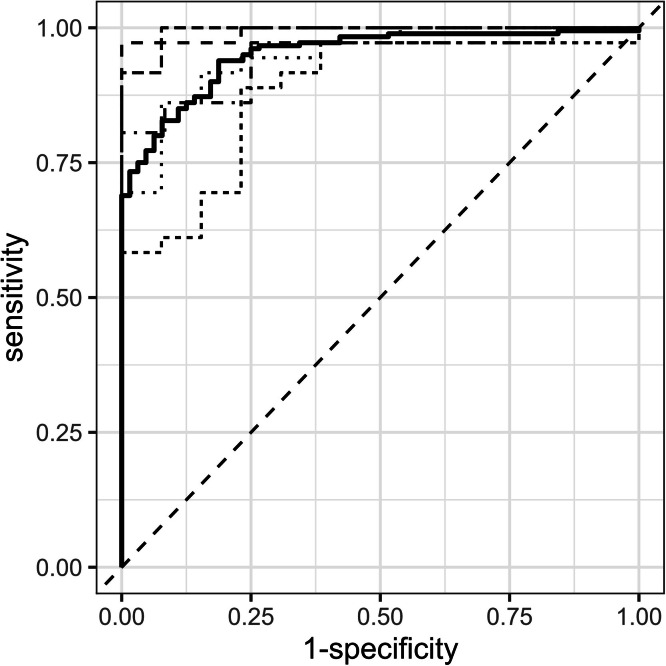

To identify the most effective miRNA-based diagnostic model for accurately differentiating between healthy and disease groups, we chose the model with the highest AUC score from 5-fold cross-validation for further analysis. This selected miRNA-based diagnostic model achieved an AUC score of 0.95, with a sensitivity of 85 % and a specificity of 88 % (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

ROC curve analysis of the optimal diagnostic model for disease detection using a comprehensive miRNA profile with 5-fold cross validation.

combined ROC: solid line; ROC folds 1-5: dashed lines.

AUC score: 0.95; sensitivity: 85%; specificity: 88%.

3.3. Performance evaluation of selected miRNA diagnostic models

The chosen miRNA-based diagnostic model was tested on a validation dataset (74 samples from disease groups and 27 samples from healthy subjects). In this validation dataset, the model achieved an AUC score of 0.89, with a sensitivity of 84 % and a specificity of 89 % (Fig. 2). Among the 35 dogs in the disease group of the validation dataset, 22 were being treated with medications such as prednisolone; however, the accuracy of the miRNA-based diagnostic model was not influenced by the presence or absence of medication (Fisher's exact test, p > 0.05). For conditions not represented in the training dataset, such as liposarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, parathyroid adenoma, dilated cardiomyopathy, granulomatous lymphangitis, and adrenal adenoma (one case each), the model identified liposarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, and adrenal adenoma as positive.

Fig. 2.

Performance evaluation of the optimal miRNA-based diagnostic model in a validation dataset.

AUC score: 0.89; sensitivity: 84% (95% CI: 0.74–0.92); specificity: 89% (95% CI: 0.78–1.00).

Of the 254 dogs in the disease group, 130 were undergoing drug treatment. The allocation of subjects to groups was conducted without regard to medication status. According to the miRNA-based diagnostic model, 120 dogs receiving medication were identified as having the disease, whereas 99 dogs not on medication were also recognized as diseased (Table 4).

Table 4.

Impact of drug therapy on the performance of the diagnostic model.

| Training dataset (n = 180) |

Validation dataset (n = 74) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Judgement | Disease | Healthy | Disease | Healthy |

| With medication(n) | 89 | 6 | 31 | 4 |

| No medication(n) | 68 | 17 | 31 | 8 |

4. Discussion

Numerous studies have demonstrated that miRNAs directly or indirectly regulate the expression of a wide array of genes in dogs, with miRNA-mediated gene regulation in various diseases proving to be complex (Colombe et al., 2022). Consequently, we focused on analyzing miRNA information without pre-selecting specific data. NGS represents a transformative technology capable of simultaneously and accurately quantifying miRNAs, thereby enabling the comprehensive analysis of miRNA expression. In addition, the integration of NGS with autoML facilitates the development of miRNA-based diagnostic models without the burden of programming and technical bias (Inagaki et al., 2023). In this study, we collected a broad range of dog cases, without regard to disease type, lesion location, or severity, and generated a comprehensive circulating miRNA profile using NGS technology and autoML, from which a screening model was constructed. This diagnostic model showed a sensitivity of 84 % and a specificity of 89 % in the validation dataset (Fig. 2). The results suggested that this diagnostic model has the potential to detect diseases beyond those it was trained to identify. As shown in Table 4, our findings indicate that the performance of the diagnostic model is not influenced by drug therapy, suggesting its use as a screening test.

Animals were categorized into disease and healthy groups based on veterinary diagnoses, highlighting the need to assess whether the diagnostic model can maintain its performance when applied to pre-diagnosis cases. Furthermore, while the system successfully identified certain diseases it had not been trained to detect, it failed to recognize others, highlighting the importance of future performance evaluations for untrained diseases. Given its current capabilities, the model struggles to identify individual diseases, suggesting that traditional imaging diagnostics remain indispensable. A future goal is to develop models capable of detecting specific diseases.

This study was not without limitations. First, an imbalance in case numbers between the healthy and disease groups was observed (Table 1). Second, the study sample included both healthy young dogs and diseased older dogs, resulting in an age bias between the groups; significant age differences can affect the results (Welch's t-test, p < 0.01) (Table 1). Third, the presence of multiple diseases in some cases might have influenced the results due to varying reactivity by disease type. Fourth, the lack of a follow-up survey means that if cases initially deemed healthy had existing abnormalities at the time of blood sampling, their inclusion in the healthy group could impact the performance of the diagnostic model. Finally, without considering the severity of each case, it is challenging to ascertain the detectable level of abnormality.

5. Conclusion

The miRNA-based diagnostic model developed using NGS and autoML technology, which accurately determines the presence or absence of disease, highlights the clinical value of comprehensive miRNA profiles and their suitability for clinical application. The diagnostic model, relying on miRNA profiles, opens the prospect of whole-body screening through minimally invasive means such as blood sampling. Unlike imaging techniques such as CT and MRI, this approach does not require general anesthesia, thereby lessening the physical strain on pets and the financial burden on owners, and it shows promise for disease monitoring. Subsequent research following this pilot study should aim to identify the location of the disease or lesion, examine the relationship between disease severity and treatment progression, and further explore this promising direction.

Ethical Statement

Blood sample residues were collected for clinical testing from dogs at seven veterinary hospitals, including the University of Tokyo Animal Medical Center, Kagoshima University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Animal Medical Center, and Nippon Veterinary and Life Science University Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, from January 2022 to January 2023. The majority of these dogs were undergoing veterinary treatment. Written consent for the use of these specimens for research purposes was obtained from the owners.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kohei Omura: Writing – original draft. Kaori Ide: Writing – review & editing. Masashi Takahashi: Writing – review & editing. Yu Furusawa: Investigation. Masanori Kobayashi: Writing – review & editing. Yuichi Miyagawa: Resources, Investigation. Aki Fujiwara-Igarashi: Resources, Investigation. Takahiro Teshima: Resources. Yoshiaki Kubo: Resources. Akiko Yasuda: Resources. Karin Yoshida: Resources. Noriyuki Hayakawa: Resources. Masato Kobayashi: Resources. Yasuyuki Momoi: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Kohei Omura reports a relationship with Arkray Marketing Inc that includes: employment. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to everyone who cooperated in this study.

References

- Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431(7006):350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai M., Sun L., Jia C., Li J., Han Y., Liu H., Chen Y., Jiang H. Integrated Analysis of miRNA and mRNA Expression Profiles Reveals Functional miRNA-Targets in Development Testes of Small Tail Han Sheep. G3 (Bethesda, Md.) 2019;9(2):523–533. doi: 10.1534/g3.118.200947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J.D., Liu G., Luo L., Xiao J., Gerrein J., Juan-Guardela B., Tedrow J., Alekseyev Y.O., Yang I.V., Correll M., Geraci M., Quackenbush J., Sciurba F., Schwartz D.A., Kaminski N., Johnson W.E., Monti S., Spira A., Beane J., Lenburg M.E. Assessment of microRNA differential expression and detection in multiplexed small RNA sequencing data. RNA (New York, N.Y.), 2015;21(2):164–171. doi: 10.1261/rna.046060.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.W., Lai Y.C., Rahman M.M., Husna A.A., Hasan M.N., Miura N. Micro RNA differential expression profile in canine mammary gland tumor by next generation sequencing. Gene. 2022;818 doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2022.146237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombe P., Béguin J., Benchekroun G., Le Roux D. Blood biomarkers for canine cancer, from human to veterinary oncology. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology. 2022;20(4):767–777. doi: 10.1111/vco.12848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory A., McLennan L., Peet B., Kroll M., Stuart D., Brown D., Stuebner K., Phillips B., Coomber B.L., Woods J.P., Miller M., Tripp C.D., Wolf-Ringwall A., Kruglyak K.M., McCleary-Wheeler A.L., Phelps-Dunn A., Wong L.K., Warren C.D., Brandstetter G., Rosentel M.C., Rafalko J.M. Cancer detection in clinical practice and using blood-based liquid biopsy: A retrospective audit of over 350 dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2023;37(1):258–267. doi: 10.1111/jvim.16616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki M., Uchiyama M., Yoshikawa-Kawabe K., Ito M., Murakami H., Gunji M., Minoshima M., Kohnoh T., Ito R., Kodama Y., Tanaka-Sakai M., Nakase A., Goto N., Tsushima Y., Mori S., Kozuka M., Otomo R., Hirai M., Fujino M., Yokoyama T. Comprehensive circulating microRNA profile as a supersensitive biomarker for early-stage lung cancer screening. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2023;149(11):8297–8305. doi: 10.1007/s00432-023-04728-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien J., Hayder H., Zayed Y., Peng C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2018;9:402. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papoutsoglou G., Karaglani M., Lagani V., Thomson N., Røe O.D., Tsamardinos I., Chatzaki E. Automated machine learning optimizes and accelerates predictive modeling from COVID-19 high throughput datasets. Scientific Reports. 2021;11(1):15107. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-94501-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]