Abstract

The western corn rootworm (WCR), Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte, has evolved resistance to nearly every management tactic utilized in the field. This study investigated the resistance mechanisms in a WCR strain resistant to the Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) protein eCry3.1Ab using dsRNA to knockdown WCR midgut genes previously documented to be associated with the resistance. ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCC4), aminopeptidase-N, cadherin, and cathepsin-B were previously found to be differentially expressed in eCry3.1Ab-resistant WCR larvae when compared to susceptible larvae after feeding on maize expressing eCry3.1Ab and its near-isoline. Here we compared the susceptibility of resistant and susceptible WCR larvae to eCry3.1Ab protein in presence or absence of dsRNA targeting the above genes using 10-day diet overlay toxicity assays. Combining ABCC4 dsRNA with eCry3.1Ab protein increased susceptibility to Bt protein in WCR-resistant larvae, but the other three genes had no such effect. Among 65 ABC transport genes identified, several were expressed differently in resistant or susceptible WCR larvae, fed on eCry3.1Ab-expressing maize versus its isoline, that may be involved in Bt resistance. Our findings provide strong evidence that ABCC4 is indirectly involved in WCR resistance to eCry3.1Ab protein by enhancing the effects of Bt-induced toxicity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-83135-7.

Keywords: Diabrotica virgifera virgifera, Bacillus thuringiensis, Corn rootworm, Resistance mechanisms, RNAi, Insect resistance management

Subject terms: Entomology, Assay systems

Introduction

The western corn rootworm (WCR), Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte, is the most important maize pest in the U.S. Corn Belt and other parts of North America and Europe, causing annual yield losses and control expenses of over $2 billion1. Crop rotation using unsuitable host plants is the primary management technique for WCR2. Since 2003, maize hybrids expressing at least one of the four currently available Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxins that target WCR3–7 are the most widely adopted management technique in continuous maize2. However, WCR has shown a remarkable ability and elasticity to evolve resistance to management including granular soil insecticides targeting larvae, adulticides8–10, crop rotation11, and Bt-expressing maize12–16 with cross resistance reported among the Cry3 Bt toxins16–19. Most recently, a new mode of action, RNA interference (RNAi), targeting WCR20 has cleared U.S. regulatory hurdles towards full commercialization21,22. The approved product, SmartStaxPro® is a pyramid of three traits with different modes of action for corn rootworm control including dsRNA targeting snf7 expression, stacked with Bt proteins Cry3Bb1 and Gpp34/Tpp35Ab1 (formerly Cry34/35Ab1)23–25. However, resistance against RNAi can be selected for. WCR beetles surviving snf7 RNAi expression in the field developed a resistance ratio of greater than 130 after further laboratory selection26. The Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) also developed resistance to an RNAi management product27, leading to concern that many pest insects may be able to evolve resistance against this new control technology.

Several genetic studies in different WCR strains resistant to Bt have found potential candidate genes involved in Bt resistance mechanisms including, but not limited to, ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter, aminopeptidase-N (APN), cadherin (CAD), and cathepsin-B (CATB)24,28–35. However, these studies demonstrated no clear evidence that these genes are genuinely involved in WCR Bt resistance. Based on results from a WCR transcriptome, potential genes such as an ABCB transporter, APN, CAD, and glycosyltransferase were found to be involved in Cry3Bb1 resistance30,32,35. The role of ABCB1 in WCR was subsequently validated as a functional receptor of Cry3Aa protein, by expressing the gene in Sf9 and HEK293 cell lines36. The increased expression of several genes, including APN and ABC transporters, was reported in a WCR Cry3Bb1-resistant strain compared to a susceptible strain, after neonates fed on Bt or non-Bt maize31. Recent comparisons of the transcriptomes of WCR strains resistant (RES) and susceptible (SUS) to eCry3.1Ab after feeding on eCry3.1Ab-expressing maize and near-isoline maize for 12–24 h showed differential gene expression in an ABC (ABCC4) transporter, APN, CAD, and CATB33. These candidate genes could potentially be involved in resistance to eCry3.1Ab protein in WCR33. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to (1) compare the relative expression of these four genes in RES and SUS larvae after feeding on dsRNA-treated diet, (2) evaluate susceptibility of RES and SUS strains to eCry3.1Ab protein alone or mixed together with dsRNA of each of the four genes, and (3) compare the relative expression of all known ABC transporters in RES and SUS larvae after feeding on Bt and isoline maize.

Results

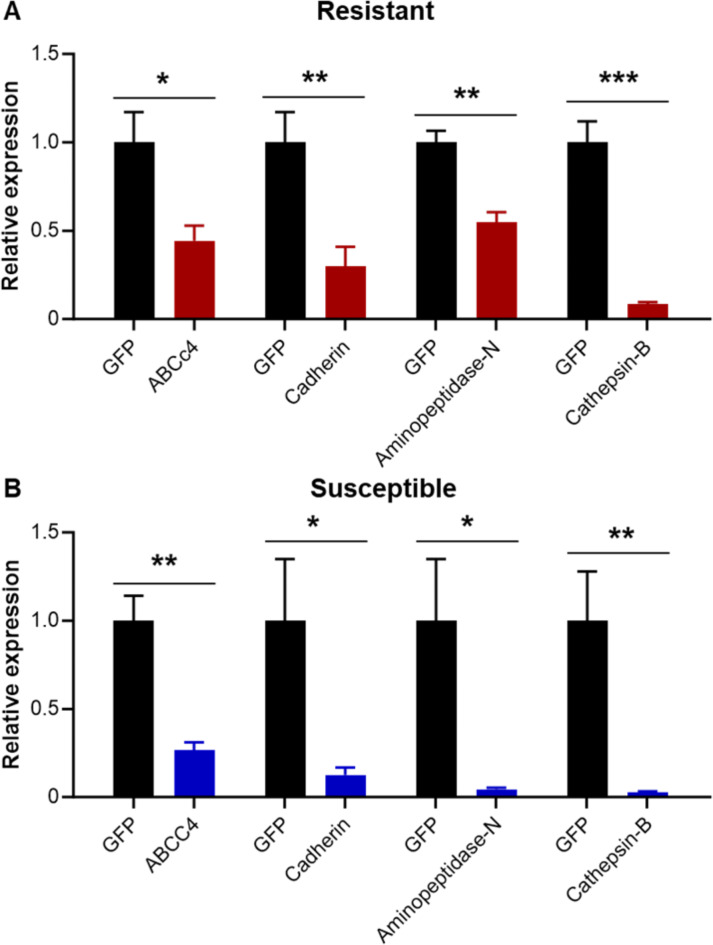

Relative gene expression after knockdown of ABCC4, APN, CAD, and CATB using dsRNAs in WCR neonates

From a previous study of transcripts differentially expressed in WCR larval midguts fed on eCry3.1Ab maize seedlings33, we selected several upregulated transcripts that corresponded to midgut Bt-interacting proteins known from other insect species. Among these were the WCR orthologs of CAD, CATB, APN, and ABCC4 transporter (ABCc (5345), using the newer terminology28). Transcript knockdowns targeting these candidates with dsRNAs were followed by toxicity tests using eCry3.1Ab protein on artificial diet in 96-well plates. Significant levels of knockdown were observed in RES and SUS larvae after feeding for three consecutive days on 1 µg/cm2 of ABCC4, APN, CAD, or CATB dsRNA on artificial diet when compared to those larvae that fed on green fluorescent protein dsRNA (GFP, 1 µg of dsRNA/cm2) (Fig. 1). Levels of knockdown ranged from 1.7-fold (APN) to 11.7-fold (CATB) in RES strain and from 4.5-fold (ABCC4 transporter) to 23-fold (APN) in SUS strain, relative to GFP (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Relative gene expression after knockdown of ABCC4 transporter, aminopeptidase-N, cadherin, and cathepsin-B using dsRNAs in eCry3.1Ab Diabrotica virgifera virgifera resistant and susceptible neonates that fed for three consecutive days on 1 µg of dsRNA/cm2, overlaid on artificial diet. Means (± SEM) generated from six replicates (8–10 larvae per replicate). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

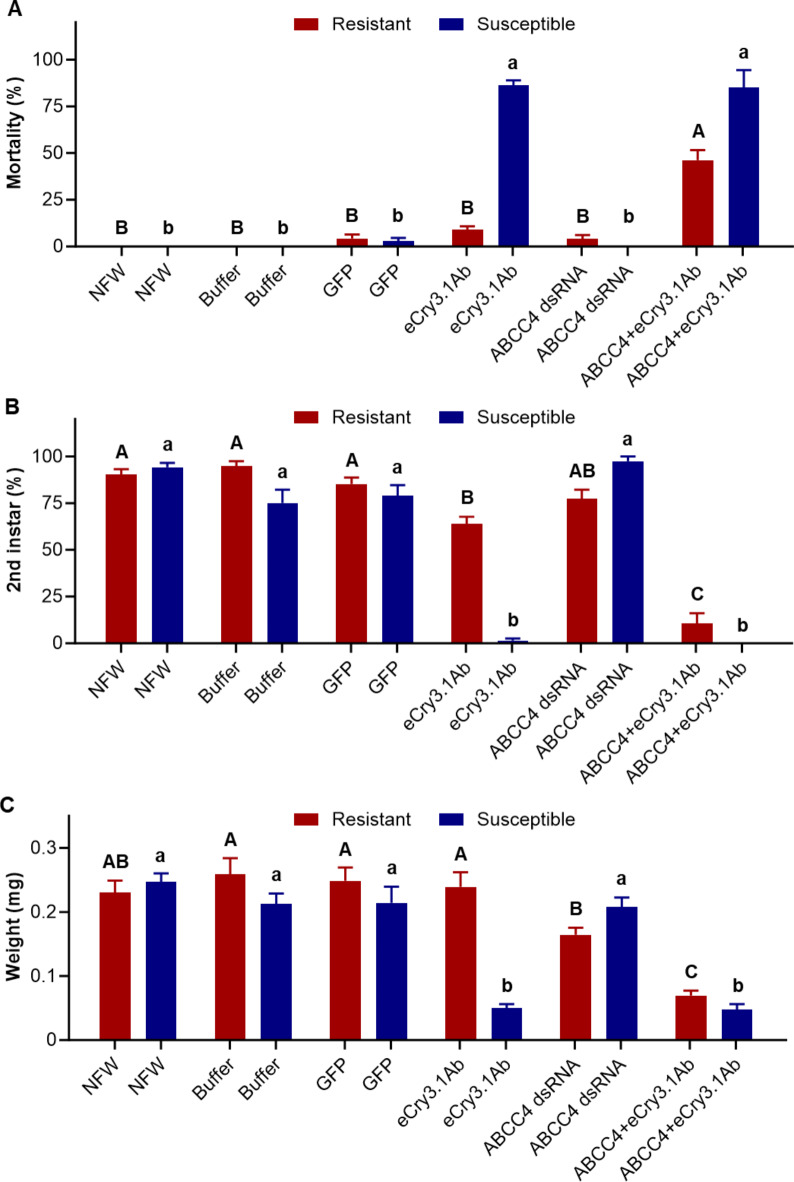

Susceptibility of WCR neonates to eCry3.1Ab protein alone or mixed with dsRNA

Of these four gene candidates (CAD, CATB, APN, and ABCC4 transporter) the only dsRNA knockdown which influenced the WCR larval response to eCry3.1Ab protein in the RES strain was ABCC4 (Fig. 2, Suppl. Fig. 1). After a 10-d assay period, larval mortality to ‘ABCC4 dsRNA + eCry3.1Ab’ was significantly higher (F5,40 = 15.08, P < 0.0001) when compared to any other treatment within the RES strain (Fig. 2). For the SUS strain, mortality was significantly higher (F5,35 = 26.46, P < 0.0001) in all treatments with eCry3.1Ab protein when compared to those without eCry3.1Ab (Fig. 2). A significantly lower (F5,35 = 10.07, P < 0.0001) percentage of SUS 2nd instar larvae were found in all treatments with eCry3.1Ab protein when compared to those treatments without eCry3.1Ab (Fig. 2). Percent of 2nd instars (F5,40 = 13.74, P < 0.0001) and larval dry weight (F5,40 = 24.83, P < 0.0001) were significantly lower for the treatment ‘ABCC4 dsRNA + eCry3.1Ab’ when compared to all other treatments within the RES strain (Fig. 2). In the SUS strain, larval dry weights were significantly lower (F5,30 = 41.42, P < 0.0001) in those larvae that survived ‘ABCC4 dsRNA + eCry3.1Ab’ protein and eCry3.1Ab alone when compared to larvae that survived ABCC4 dsRNA alone and controls (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Percent mortality (A), percent of 2nd instar (B), and larval dry weight (C) in Diabrotica virgifera virgifera resistant and susceptible strains after exposure to eCry3.1Ab protein (24.3 µg/cm2) alone, to ABCC4 dsRNA alone (1.0 µg/cm2), or mixed with 1.0 µg/cm2 of ABCC4 dsRNA, as well as to nuclease free water (NFW), 10 mM carbonate/bicarbonate buffer, and green fluorescent protein (GFP) dsRNA (1.0 µg/cm2) as controls, in 10-day diet overlay toxicity assays. Data represent means (± SEM) of ten replicates (8 larvae per replicate). Bars followed by different upper-case letters (resistant strain) or lower-case letters (susceptible strain), within each strain were significantly different (P < 0.05).

Quite unexpectedly knockdown of the ABCC4 transcript partially restored WCR larval susceptibility to eCry3.1Ab toxicity in RES larvae (i.e., larvae selected for many generations on eCry3.1Ab-expressing maize). This result was robust in several different trials. Based on these intriguing results we refocused our efforts on more detailed studies of known ABC transporters37 in the WCR larval response to eCry3.1Ab intoxication.

Transcriptomic analyses

We conducted transcriptome analyses of RES and SUS larvae fed on eCry3.1Ab-experssing maize and its isoline to further identify ABC transporters potentially involved in WCR larval response to eCry3.1Ab intoxication. We generated a new, high-coverage library, annotated the examined genes (ABCC4, APN, CAD, and CATB), as well as all known WCR ABC transporters37, and compared their relative expressions. Our analysis revealed higher transcript read counts for all four genes in RES larvae fed on eCry3.1Ab-expressing maize compared to those fed on isoline maize, although these differences were not significant (Suppl. Fig. 2). Similarly, in SUS larvae, higher expression levels of ABCC4, APN, and CATB were observed when fed on eCry3.1Ab-experssing maize compared to the isoline maize, with a significant difference observed only for APN (Suppl. Fig. 2).

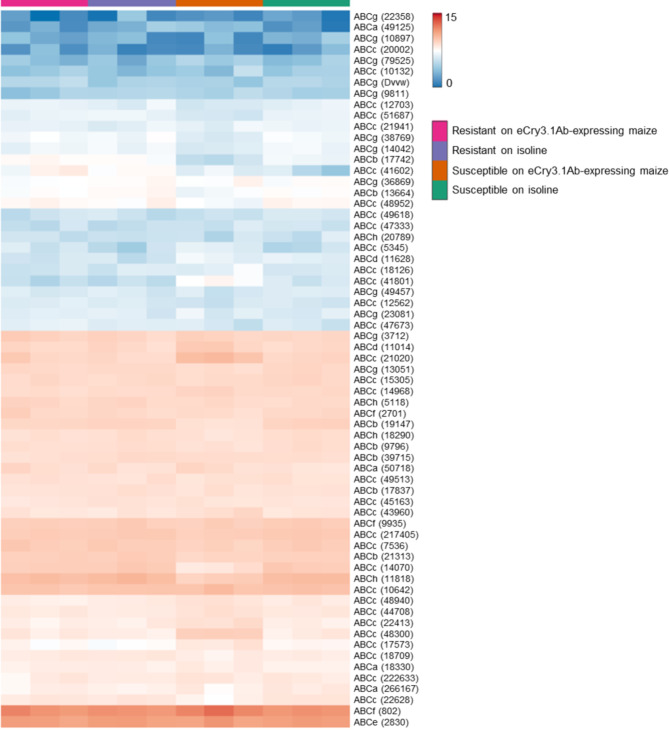

The identified ABC transporters were labeled according to the recent published nomenclature28 (Table 1). A total of 65 ABC transporter genes were found to be expressed in at least one of the treatment samples (Fig. 3). ABC transporter subfamilies, A, B, C, D F, G and H were among those in upregulated and downregulated responses. A clear pattern of coordinate expression of ABC transporters was observed upon larval feeding on eCry3.1Ab-expressing maize seedlings (Fig. 3, summarized in Table 1).

Table 1.

List of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters differentially expressed in resistant (RES) and susceptible (SUS) larvae fed on eCry3.1Ab-expressing maize (Bt maize) versus its isoline (isoline maize).

| Comparison | ABC transporters differently expressed* | ABC genes upregulated | ABC genes downregulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUS on isoline maize vs. SUS on Bt maize | 4 up/ 19 down in SUS on isoline maize | ABCc (41801), ABCc (21020), ABCc (48300), ABCf (802) | ABCb (21313), ABCb (17742), ABCb (19147), ABCb (9796), ABCc (48952), ABCc (51687), ABCc (14070), ABCc (22628), ABCc (7536), ABCc (217405), ABCc (15305), ABCe (2830), ABCf (2701), ABCf (9935), ABCg (14042), ABCg (13051), ABCg (38769), ABCh (18290), ABCh (11818) |

| RES on isoline maize vs. RES on Bt maize | 0 | – | – |

| SUS on isoline maize vs. RES on isoline maize | 3 up/ 4 down in RES on isoline maize | ABCb (17742), ABCc (18709), ABCc (41602) | ABCa (266167), ABCc (41801), ABCc (17573), ABCd (11628) |

| SUS on Bt maize vs. RES on Bt maize | 18 up/ 3 down in RES on Bt maize | ABCb (21313), ABCb (17742), ABCb (19147), ABCb (9796), ABCc (48952), ABCc (51687), ABCc (14070), ABCc (22628), ABCc (7536), ABCc (41602), ABCc (12703), ABCf (2701), ABCg (3712), ABCg (14042), ABCg (13051), ABCg (38769), ABCh (5118), ABCh (11818) | ABCc (41801), ABCc (21020), ABCc (48300) |

The ABC transporter gene names listed are derived from the recent published nomenclature28. The letter following ‘ABC’ in gene names represents the ABC transporter family, and the numbers reflect gene transcript contig IDs reported previously28. *Statistically significant differences are based on normalized read counts between comparisons when the log2 (fold change) was greater than 1 and the adjusted P-value was less than 0.05.

Fig. 3.

Relative ATP-binding cassette (ABC) gene expression in eCry3.1Ab resistant or susceptible Diabrotica virgifera virgifera neonate larvae after feeding on eCry3.1Ab expressing or isoline maize seedlings, as determined by RNASeq analyses. The letter following ‘ABC’ in gene names represents the ABC transporter family, and the numbers reflect gene transcript contig IDs reported previously28. For heatmap visualization, read count data were rounded to integers before applying a normalizing transformation to each transcript count (log2 (x + 0.5))86.

When eCry3.1Ab SUS larvae were allowed to feed on eCry3.1Ab-expressing maize seedlings, 4 ABC transporters were upregulated and 19 were downregulated. Among those downregulated was ABCb (17742), which is the WCR ABCB1 transporter Cry3 receptor36, ABCg (38769) reported upregulated by Cry3Ab29, ABCe (2830) reported upregulated by Gpp34/Tpp35Ab129, and finally ABCc (15305) which was also reported upregulated in WCR larvae by both Cry3Bb1 and Gpp34/Tpp35Ab1 intoxication29.

In WCR larvae feeding on eCry3.1Ab-expressing maize seedlings RES and SUS expressed opposite expression profiles of several, but not all, ABC transporters. SUS larvae showed downregulation of ABCb (21313), ABCb (17742), ABCb (19147), ABCb (9796), ABCc (48952), ABCc (51687), ABCc (14070), ABCc (22628), ABCc (7536), ABCc (217405), ABCe (2830), ABCf (2701), ABCf (9935), ABCg (14042), ABCg (13051), ABCg (38769), and ABCh (11818), with upregulation of ABCc (41801), ABCc (21020), ABCc (48300), and ABCf (802) (Table 1).

In contrast, when eCry3.1Ab RES larvae were allowed to feed on Bt-expressing maize seedlings, no ABC transporters were found to be upregulated or downregulated compared to those that fed on isoline maize (Table 1). Comparisons between SUS and RES larvae fed on isoline maize seedlings resulted in the upregulation of 3 ABC transporters and the downregulation of 4 in RES larvae. Among a total of 21 ABC transporters found to be differentially expressed between SUS and RES larvae fed on eCry3.1Ab-expressing maize seedlings, 18 were upregulated in RES larvae compared to SUS larvae (Table 1). The putative Cry3 receptor, ABCb (17742), which was the ABCB136 was among those upregulated by eCry3.1Ab feeding in RES larvae.

Discussion

Field-evolved and laboratory-selected resistance of WCR populations to delta pore-forming toxins, such as the Cry3 proteins derived from Bt (Cry3Bb1, mCry3A, and eCry3.1Ab) drive efforts to better elucidate the underlying genetics and biochemical mechanisms that enable resistance13–17,38. The toxicity of Bt proteins to WCR is presumed to follow the widely accepted model of sequential binding and pore formation observed in insects38. In this model, Cry3 proteins undergo proteolytic activation and proteins of the WCR midgut protruding from the outer leaflet of the brush border membrane are ligands which allow binding of Cry3 toxins. The protein binding leads next to assembly of toxin monomers into oligomers, which span the plasma membrane, causing extensive leakage of cations into the cell, ultimately disrupting and lysing the midgut cells39. The resulting damage, if not repaired, breaches the midgut leading to fatal septicemia40–42. However, other models of Bt intoxication have been suggested, such as activation of intracellular pathways that cause cell death40,42 as well as the sequential binding of Bt protein to different receptors38. The ligand-binding step in other insect species has been documented to involve midgut proteins such as APN, alkaline phosphatases, CAD, and ABC transporters, in which reduced expression or structural variants of these proteins confers resistance38,41.

We recently identified a slate of WCR candidate genes that were differentially expressed following neonate feeding on eCry3.1Ab-expressing maize seedlings33. The responses differed between the eCry3.1Ab-RES and SUS strains of WCR, which could be linked to evolving eCry3.1Ab resistance in the laboratory-selected colony43. Among the differentially expressed genes were some commonly associated with Bt resistance in Lepidoptera such as CAD44, and ABC transporters38,45. The ABC transporter gene superfamily is comprised of integral membrane proteins that are divided into eight subfamilies (A-H) found in all eukaryotes40,46–48. ABC transporters pump small intracellular metabolites, including pharmaceuticals, insecticides, and other xenobiotics, out of tissues such as the midgut and Malpighian tubules48–51. The proposed mechanism for ABC transporter involvement in Bt toxicity is binding to and/or facilitating binding of the Cry protein to target sites on the midgut epithelial cell membrane52. In the present study, we have conducted knockdown of four candidates. We designed dsRNA targeting the ABCC4, APN, CAD, and CATB-like protease and used these in artificial diet overlay toxicity experiments with eCry3.1Ab protein. All four dsRNAs caused a significant reduction in larval transcript levels in RES and SUS WCR strains compared to control larvae fed GFP dsRNA. The knockdown of ABCC4 using dsRNA mixed with eCry3.1Ab protein in WCR neonates demonstrated in this report caused synergism and increased susceptibility of RES larvae to the Bt protein.

Elucidating the mechanisms of resistance evolution to Bt in WCR has been a major goal explored by several recent studies28,30,31,33,36,53,54. This is not surprising given the seemingly continuous reports of resistance evolution in WCR field populations13–15,55. Understanding the genetics of resistance in insect pests can help improve and implement new strategies of pest management. These should follow the principles of insect resistance management to mitigate and delay the onset of resistance and extend product longevity in the field56. This study is the first to report a synergism between ABCC4 dsRNA and eCry3.1Ab protein when applied together in diet toxicity assays, in RES larvae. Additional evidence of increased susceptibility can be seen on clear growth inhibition of surviving RES larvae exposed to ABCC4 dsRNA + eCry3.1Ab, when compared to surviving RES larvae exposed to eCry3.1Ab alone, to ABCC4 dsRNA alone, and to controls. However, no mutation or single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the ABCC4 sequence was evident between the WCR RES and SUS strains. Among distinct genes involved in Bt resistance in other insect pests, the ABC transporter subfamily C could potentially be involved in WCR resistance to eCry3.1Ab protein based on its upregulation in RES and SUS strains as previously reported33. The lower level of gene knockdown observed in the RES strain for ABCC4, APN, and CAD when compared to SUS strain in diet assays may suggest another evidence of upregulation of these genes, but further research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Prior to this study, we exposed WCR larvae to ABCC4 dsRNA for 72 h before transferring them to eCry3.1Ab-treated diet, but no increased larval mortality was observed in the RES strain, given that 72 h-old 1st instar larvae were later found to be less susceptible to eCry3.1Ab protein. For Fig. 1, ABCC4 dsRNA was mixed together with eCry3.1Ab protein so that the knockdown occurred as soon as larvae fed on dsRNA, leading to increased larval mortality to the Bt protein. The results found in this study with SUS strain are contrary of those reported in lepidopteran insects and in the mealworm, Tenebrio molitor L., where the silencing of genes involved in Bt resistance in susceptible insects, including ABC transporter, APN, and CAD led to reduced susceptibility of larvae to Bt proteins57–60. In our study, ABCC4 dsRNA + eCry3.1Ab protein or eCry3.1Ab protein alone caused 85% mortality in SUS strain. Bt resistance in WCR may be complex in such a way that it possibly involves different pathways and/or unknown sequential biding that do not involve the Bt protein itself, and likely involves genes other than ABC transporter24,38.

RNAi knockdown in WCR larvae begins after a few hours of feeding on dsRNA61. One of the reasons that we observed 46% mortality in the RES larvae after feeding on eCry3.1Ab protein + ABCC4 dsRNA, compared to only 9% mortality in those fed on eCry3.1Ab protein alone, may be that, after one or two days, there could still be enough ABCC4 protein and/or transcripts to act on the resistance mechanism, which would have possibly prevented higher larval mortality to eCry3.1Ab protein. It is also possible (and most likely) that the resistance mechanism in WCR is more complex and involves more than one gene as suggested in recent studies24,31,33,34,62. In two recent studies published simultaneously, two ABC transporters were reported to cause much higher levels of resistance in the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.), and the cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera Hübner, respectively45,63, suggesting that multiple ABC transporter genes can be associated with Bt resistance. The leaf beetle, Chrysomela tremula Fabricius is another coleopteran pest in the Chrysomelidae family reported to be resistant to Cry3Aa protein, caused by a mutation in P-glycoprotein that is homologous to ABC transporter subfamily B64.

The higher mortality and clear growth inhibition (lower percent of 2nd instars and lower dry weight) observed in RES WCR larvae after exposure to ABCC4 dsRNA + eCry3.1Ab protein compared to insects exposed to eCry3.1Ab protein alone documents synergism and suggests that ABCC4 could play a significant role in physiological processes in WCR larvae. However, it is possible that the ABCC4 dsRNA could have caused non-specific or unexpected off-target effects on other ABC transporters, given the recent documentation of 65 ABC transporters in WCR28. Therefore, phenotypic changes (lower dry weight when compared to at least one of the controls) observed after exposure of larvae to ABCC4 dsRNA alone are not unexpected. Fitness costs after exposure of larvae to ABC transporter dsRNA have been observed not only in WCR28, but also in other insects65,66. It is worth noting that in our study, larvae exposed to APN dsRNA alone exhibited significantly lower dry weight when compared to buffer and GFP exposed larvae, and lower percent 2nd instar when compared to buffer, which suggests that this gene might be also involved in physiological mechanisms in the cells, thus contributing to larval growth and development by unknown routes.

Partial reversal of resistance to insect pests that have evolved resistance by addition of secondary toxins or other agents to crops could become a promising strategy to frustrate resistant larval feeding. A recent example of this approach demonstrated reversion of larval fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) Cry1F, Cry1A.105, and Cry2Ab2 maize resistance by the addition of a soybean trypsin inhibitor67. In all previous examples of Bt resistance in insects or cell lines, sequence structural variants in the resistant populations caused target insensitivity through the presence of SNP, mis-splicing, silencing, or down-regulation of midgut expressed ligands responsible for initial binding of the Bt toxin. For example, in the diamondback moth down-regulation rather than mutation in the ABC transporter sequence was linked to Cry1Ac protein resistance58. WCR was reported to possess 65 separate ABC transporters in several subfamilies (A-H)28. The ABCB1 transporter was subsequently demonstrated as a functional receptor for Cry3Aa protein36, and other ABC transporters were linked to WCR resistance30.

The increased susceptibility of the diamondback moth to Cry1Ac protein was observed after exposing resistant larvae to dsRNA targeting a protein kinase gene (MAP4K4) that is involved in signaling pathway along with ABCC and alkaline phosphatase68–70. Synergism between CAD and ABC transporter genes were reported in the bombyx mori, Heliothis virescens (Fabricius) and the cotton bollworm resistant to Bt, where the knockdown of both genes by dsRNA in the resistant strains conferred much higher levels of resistance to Bt protein when compared to single gene knockdown38,71–73. An intriguing hypothesis has recently been proposed71,74 where, in addition to the identified canonical Cry toxin binding proteins expressed in the midgut (e.g., ABCC transporters, CAD), interactions between multiple low affinity ABC transporter subfamily paralogs may mediate toxicity71,74. They posit a midgut ‘aggregate’ Cry toxin binding affinity composed of a dynamically shifting mix of receptors with varying affinity. Thus, under a cellular regulatory cascade, in response to midgut disrupting entomotoxins, the coordinate expression (upregulation and downregulation) of multiple ABC transporter genes, along with CAD, and perhaps other weakly binding receptors may occur in WCR. This regulatory cascade along with a reshuffling of expressed ABCC transporters of varying affinity for eCry3.1Ab may be one proposed mechanism that would accommodate our ABCC4 knockdown results. In support of this we noted that putative WCR Bt receptors ABCb (17742) (ABCB136) and ABCc (15305)29 were downregulated in SUS WCR larvae fed eCry3.1Ab, suggesting a cellular intoxication response to dietary Cry toxin exposure.

In conclusion, this is the first study to report the synergism between ABCC4 dsRNA and eCry3.1Ab protein in a RES WCR strain in diet toxicity assays, documenting an important role of ABCC4 in WCR resistance to eCry3.1Ab. The synergism between Bt protein and dsRNA against ABCC4 observed in this study could lead research in a different direction of elucidating the resistance mechanisms in WCR RES larvae. Further study of synergism between ABC transporter and other genes should be explored. SUS WCR larvae were still affected by eCry3.1Ab protein after the knockdown of ABCC4 suggesting that it is not a receptor for eCry3.1Ab and that other genes are likely involved in Bt toxicity in WCR larval midgut. A more comprehensive study of ABC transporter expression across other WCR Bt resistant colonies and toxins and relevant contexts would test the hypothesis that ABCC4 expression in RES strain is specific or is a more generalized response to intoxication or other environmental insults. Regardless, our results strongly suggest that ABCC transporters are good candidates for further thorough study to elucidate and understand, and perhaps to delay or circumvent, Bt resistance mechanisms in WCR.

Materials and methods

Insects

The WCR larvae resistant and susceptible to eCry3.1Ab used in this study are non-diapause strains and are maintained at Plant Genetics Research Unit, USDA-ARS in Columbia, MO43. The eCry3.1Ab RES strain used in this work was selected on non-commercial maize hybrid (event 5307) expressing eCry3.1Ab for more than 60 generations. The RES strain is over 24.3-fold resistant to eCry3.1Ab protein when compared to the SUS strain, where the highest concentration (24.3 µg/cm2) killed approximately 15% of RES larvae and over 95% of SUS larvae43,75. Maize expressing eCry3.1Ab without expressing mCry3A is not commercially available, but the maize we used in rearing did not have mCry3A. Eggs collected from these strains were maintained in complete dark at 25 °C and 50–70% relative humidity in an incubator until hatch. The egg surface sterilization protocol used was previously published76,77.

Gene target selection and dsRNA synthesis

The coding regions of WCR ABCC4, APN, CAD, and CATB sequences (accession # PXJM02213192.1, XM028291552.1, EF531715.1, and AJ583509.1, respectively) were used to design T7-promoter flanked DNA amplimers using PrimerQuest Tool (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA) for synthesis of dsRNA via in vitro transcription. DNA amplimers encoding the gene target and GFP (accession # KX234096.1) control were transcribed in vitro with the MEGAscript® RNAi kit (Invitrogen™, Waltham, MA) according to manufacturer’s instructions to produce dsRNA. Size and intactness of dsRNA were verified by submitting aliquots of dsRNA that were evaluated by Fragment Analyzer Automated CE System (Advanced Analytical Technologies, Ames, IA). PCR primers were designed to amplify regions of the gene candidates from cDNA (https://www.idtdna.com/primerquest/home/index). Double stranded RNAs used in knockdown experiments were purchased from RNA Greentech LLC (Frisco, TX, USA; TX, https://rnagreentech.com); GFP was purchased from Genolution Inc. (Seoul, Korea, http://genolution.co.kr ). Double stranded RNA sizes and primers used in all experiments are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Gene expression after larval feeding on dsRNA-treated diet

To knock down genes, approximately 100 WCR neonates (< 24 h old) were transferred to 5-cm diameter petri dishes (7232, Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY) filled with 2 mL of artificial diet78 per treatment, each treated with dsRNA (1 µg/cm2 overlaid on artificial diet) and were allowed to feed for three consecutive days as described previously79. We exposed WCR larvae to dsRNA for three days because knockdown happens within a few hours after exposure61. Three 2 mL Lysing Matrix D tubes with ceramic spheres (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), each containing a subsample of 10–12 larvae, were collected per treatment and were flash-frozen at – 80 °C for later RNA extraction to perform real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR). The experiment was performed in duplicate each using different WCR cohorts, for a total of six tubes per treatment. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit® (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD), with the following modifications: larvae were homogenized on a Mini-BeadBeater™ (BioSpec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK) and the lysate was centrifuged in a QIAshredder Mini Spin Column (QIAGEN) before beginning step one. Quality and concentration of extracted RNA samples were analyzed using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The cDNA was synthesized with 50 ng of RNA which was used as the template for reverse transcription with the Omniscript RT Kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer protocol, with an additional incubation of 95 °C for 10 min as the last step. Each PCR reaction was assembled with the QuantiFast SYBR® Green PCR Kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacture protocol with the following cycling conditions: 95 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s; then one cycle of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s 20 min temp increase to 95 °C, and 95 °C for 15 s in a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems™, Waltham, MA) using β-actin primers80 as the internal control. All qPCR reactions were performed with three biological and three technical replicates and normalized expression ratio was calculated accordingly81.

Susceptibility of RES and SUS larvae to eCry3.1Ab protein alone or mixed with dsRNA

RES WCR larvae, which were resistant to eCry3.1Ab, and its paired SUS strain43, were exposed to 24.3 µg/cm2 of eCry3.1Ab protein alone or in the presence or absence of 1 µg/cm2 of dsRNAs or to dsRNAs alone, overlaid on artificial diet. This Bt concentration is known to cause up to 100% mortality in susceptible insects75. From initial experiments to determine the susceptibility of SUS and RES larvae to eCry3.1Ab, eCry3.1Ab protein at 30 µg/cm2 caused approximately 90% and 10% of SUS and RES larvae, respectively (Suppl. Fig. 3), consistent with the previous report75. Moreover, susceptibility of older 1st instar SUS larvae (i.e., < 24 h old, 1-day, 2-days, 3-days, or 4-days old) to eCry3.1Ab protein at 24.3 µg/cm2 was also evaluated. While very few neonate larvae (< 6%) survived after exposure to eCry3.1Ab protein at 24.3 µg/cm2, 43% of the 1-day old larvae and more than 75% of the 2-days old larvae did (Suppl. Fig. 4). Therefore, neonate larvae were selected for this study. The dsRNA concentration (1 µg/cm2) used in this study was based on previous research reporting that this concentration of other dsRNAs targeting essential genes killed approximately 100% of WCR larvae79.

The 96-well plates (3596, Costar, Corning Inc., Corning, NY) used for the assays contained 200 µl of artificial diet per well78, were overlaid with 20 µl per well of solution82,83 and let dry in a safety cabinet. One neonate larva (< 24 h old) was transferred to each well, plates were sealed (TSS-RTQ-100, Excel Scientific, Inc., Victorville, CA) and one hole was punched in each well using #0 insect pin. Six treatments for each strain were used as follow: the diet was overlaid with nuclease free water (NFW), 10 mM sodium carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (pH 10.0), GFP dsRNA (1 µg/cm2), ABCC4 dsRNA (1 µg/cm2) alone, ABCC4 dsRNA (1 µg/cm2) plus eCry3.1Ab protein (24.3 µg/cm2), and eCry3.1Ab protein (24.3 µg/cm2) alone. NFW, buffer, and GFP were used as controls. The assays were performed in 10 replicates with 8 insects per replicate (80 insects per treatment). After 10 days, surviving larvae from each treatment were collected in 0.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes (EZ micro test tubes, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) containing 70% ethanol and placed in an oven (602752, Blue M Therm Dry Bacteriological Incubator, Hogentogler & Co. Inc., Columbia, MD) at 60 °C for at least 48 h. Dry weight was recorded using a Sartorius Cubis ultra micro scale (MSU 6.6 S-000-DM, Sartorius Corporate, Göttingen, Germany). Only replicates having control mortality less than 20% were considered in the analyses.

Transcriptome generation

Twelve tubes of purified RNA from each feeding treatment (SUS and RES neonates fed on isoline or eCry3.1Ab-expressing maize seedlings for 24 h as described previously33) were condensed (randomly, using equal amounts of RNA from each of four samples) into three RNA samples per treatment for transcriptome generation and analysis. The three RNA samples for each treatment were then shipped to Novogene (Sacramento, CA, USA) for library preparation, sequencing, transcriptome assembly and gene expression analyses. Briefly, mRNA-enriched cDNA libraries were prepared using a TrueSeq RNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina) and a minimum of 80 million reads were generated for each sample using Illumina’s Novaseq platform (PE150). After sequencing, adapter sequences were removed and reads were dropped if uncertain nucleotides comprised > 10% of read or 50% of the read consisted of nucleotides of base quality < 5%. A de novo transcriptome assembly was constructed using Trinity software v2.6.684. Clean reads were mapped onto the transcriptome using RSEM software v1.2.2885 for gene expression analyses. Read counts were normalized amongst biological replicates using DESeq2 software v1.26.086 to identify differentially expressed genes between samples. ABC transporters were identified in the assembled transcriptome through local tBLASTn analyses using the amino acid sequences of previously published DvirABC transporters as queries28. ABC transporter genes were deemed to be differentially expressed between samples if the log2 (fold change) was greater than 1 and the adjusted P-value was less than 0.05. All raw transcriptomic sequencing data has been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive database on NCBI with Biosample accession numbers SAMN42392201-SAMN42392212 under the BioProject PRJNA1134000.

Statistical analysis

The relative gene expression assays were performed in completely randomized design. The relative gene expression means from larvae exposed to dsRNAs in artificial diet were compared in Student’s test using PROC TTEST in SAS 9.4, with significance at P < 0.05. The diet toxicity assays comparing the susceptibility of dsRNA alone, eCry3.1Ab alone, or the combination of both, were performed in randomized complete block design for RES and SUS strains. The data for each strain were analyzed separately, with treatments as fixed effects and replicates (plates) as random effects. Percent mortality and percent 2nd instar were calculated by dividing the number of surviving or 2nd instar larvae, respectively, by the total number of larvae in each treatment. Data were analyzed using a binomial distribution with a logit link transformation and the means were compared in Fisher’s LSD with Tukey adjustments using PROC GLIMMIX in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) with significance at P < 0.05. The dry weight data were calculated by dividing the pool weight of each treatment by the number of surviving larvae in each replicate. Data were log transformed (log x + 1) to meet the assumptions and means (± SEM) were compared in Fisher’s LSD with Tukey adjustments using PROC GLIMMIX in SAS 9.4, with significance at P < 0.05.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Karen Bromert of the University of Missouri DNA Core for dsRNA analyses, Keiran Hyte for assistance in making artificial diet, Julie Barry for technical assistance and insect rearing, as well as Dr. David Crowder for suggestions, which improved an early draft of the manuscript. Authors also would like to thank Syngenta Biotechnology for providing funds through Cooperative Research and Development Award No. 58-3K95-4-1697 to USDA-ARS, Bt protein and maize seeds to perform the study, and to anonymous reviewers for improving the manuscript. This article reports the results of research only. Mention of a proprietary product does not constitute an endorsement or recommendation for its use by the USDA or the University of Missouri. USDA and the University of Missouri are equal opportunity employers.

Author contributions

Conceptualization- AEP, KSS, BEH; Data curation- AEP, KJP, JAC, MPH; Formal analysis- AEP, KJP, MRE, MPH; Funding acquisition- BEH, KSS, TAC; Investigation- AEP, ZZ, MLG, KJP, MPH; Methodology- AEP, KJP, MLG, MPH; Project administration- AEP, BEH, KSS; Resources- BEH, KSS, TAC; Supervision- AEP, KSS, BEH, TAC; Validation- AEP, MPH; Visualization- AEP, KJP, MLG, MPH; Roles/Writing - original draft- AEP, KSS, MPH; Writing - review and editing- AEP, BEH, KJP, JAC, TAC, MLG, KSS, MPH.

Data availability

All raw transcriptomic sequencing data has been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive database on NCBI with Biosample accession numbers SAMN42392201-SAMN42392212 under the BioProject PRJNA1134000. All other pertinent data are found in the figures and tables. Request for data and additional information should be submitted to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

Adriano Pereira is an employee of RNAiSSANCE AG, St. Louis, MO, USA. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental research and collection of plant and insect materials of this study comply with the relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wechsler, S. & Smith, D. Has resistance taken root in US corn fields? Demand for insect control. Am. J. Agr Econ.100, 1136–1150 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray, M. E., Sappington, T. W., Miller, N. J., Moeser, J. & Bohn, M. O. Adaptation and invasiveness of western corn rootworm: intensifying research on a worsening pest. Ann. Rev. Entomol.54, 303–321 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis, R. T. et al. Novel Bacillus thuringiensis binary insecticidal crystal proteins active on western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.68, 1137–1145 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moellenbeck, D. J. et al. Insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis protect corn from corn rootworms. Nat. Biotechnol.19, 668–672 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaughn, T. et al. A method of controlling corn rootworm feeding using a Bacillus thuringiensis protein expressed in transgenic maize. Crop Sci.45, 931–938 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walters, F. S., deFontes, C. M., Hart, H., Warren, G. W. & Chen, J. S. Lepidopteran-active variable-region sequence imparts coleopteran activity in eCry3. 1Ab, an engineered Bacillus thuringiensis hybrid insecticidal protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.76, 3082–3088 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walters, F. S., Stacy, C. M., Lee, M. K., Palekar, N. & Chen, J. S. An engineered chymotrypsin/cathepsin G site in domain I renders Bacillus thuringiensis Cry3A active against western corn rootworm larvae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.74, 367–374 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meinke, L. J., Siegfried, B. D., Wright, R. J. & Chandler, L. D. Adult susceptibility of Nebraska western corn rootworm (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) populations to selected insecticides. J. Econ. Entomol.91, 594–600 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira, A. E. et al. Evidence of field-evolved resistance to Bifenthrin in western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte) populations in Western Nebraska and Kansas. PLos one10, e0142299 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, H. et al. Role of a gamma-aminobutryic acid (GABA) receptor mutation in the evolution and spread of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera resistance to cyclodiene insecticides. Insect Mol. Biol.22, 473–484 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine, E., Spencer, J. L., Isard, S. A., Onstad, D. W. & Gray, M. E. Adaptation of the western corn rootworm to crop rotation: evolution of a new strain in response to a management practice. Am. Entomol.48, 94–117 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gassmann, A. J., Petzold-Maxwell, J. L., Keweshan, R. S. & Dunbar, M. W. Field-evolved resistance to Bt maize by western corn rootworm. PLoS one6, e22629 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gassmann, A. J., Shrestha, R. B., Kropf, A. L., St. Clair, C. R. & Brenizer, B. D. Field-evolved resistance by western corn rootworm to Cry34/35Ab1 and other Bacillus thuringiensis traits in transgenic maize. Pest Manag. Sci.76, 268–276 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gassmann, A. J. et al. Evidence of resistance to Cry34/35Ab1 corn by western corn rootworm (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae): root injury in the field and larval survival in plant-based bioassays. J. Econ. Entomol.109, 1872–1880 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludwick, D. C. et al. Minnesota field population of western corn rootworm (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) shows incomplete resistance to Cry34Ab1/Cry35Ab1 and Cry3Bb1. J. Appl. Entomol.141, 28–40 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zukoff, S. N. et al. Multiple assays indicate varying levels of cross resistance in Cry3Bb1-selected field populations of the western corn rootworm to mCry3A, eCry3.1Ab, and Cry34/35Ab1. J. Econ. Entomol.109, 1387–1398 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gassmann, A. J. et al. Field-evolved resistance by western corn rootworm to multiple Bacillus thuringiensis toxins in transgenic maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.111, 5141–5146 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Jakka, S. R., Shrestha, R. B. & Gassmann, A. J. Broad-spectrum resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins by western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera). Sci. Rep.6, 27860 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wangila, D. S., Gassmann, A. J., Petzold-Maxwell, J. L., French, B. W. & Meinke, L. J. Susceptibility of Nebraska western corn rootworm (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) populations to Bt corn events. J. Econ. Entomol.108, 742–751 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darlington, M. et al. RNAi for western corn rootworm management: Lessons learned, challenges, and future directions. Insects13, 57 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.EPA. Pesticide registration: EPA registers innovative tool to control corn rootworm. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2017, accessed 5 Aug 2024). https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/epa-registers-innovative-tool-control-corn-rootworm).

- 22.ProgressiveFarmer. China trait approvals: China approves import of GM traits including new rootworm mode of action (2021, accessed 5 Aug 2024). https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/crops/article/2021/01/12/china-approves-import-gm-traits-new.

- 23.Bachman, P. M. et al. Ecological risk assessment for DvSnf7 RNA: a plant-incorporated protectant with targeted activity against western corn rootworm. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol.81, 77–88 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Head, G. P. et al. Evaluation of SmartStax and SmartStax PRO maize against western corn rootworm and northern corn rootworm: efficacy and resistance management. Pest Manage. Sci.73, 1883–1899 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moar, W. et al. Cry3Bb1-resistant western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera (LeConte) does not exhibit cross-resistance to DvSnf7 dsRNA. PLoS one12, e0169175 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khajuria, C. et al. Development and characterization of the first dsRNA-resistant insect population from western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte. PLoS one13, e0197059 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mishra, S. et al. Selection for high levels of resistance to double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) in Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say) using non-transgenic foliar delivery. Sci. Rep.11, 6523 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adedipe, F., Grubbs, N., Coates, B., Wiegmman, B. & Lorenzen, M. Structural and functional insights into the Diabrotica virgifera virgifera ATP-binding cassette transporter gene family. BMC Genom.20, 1–15 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coates, B. S. et al. Up-regulation of apoptotic-and cell survival-related gene pathways following exposures of western corn rootworm to Bacillus thuringiensis crystalline pesticidal proteins in transgenic maize roots. BMC Genom.22, 1–27 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flagel, L. E. et al. Genetic markers for western corn rootworm resistance to Bt toxin. G35, 399–405 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Rault, L. C. et al. Investigation of Cry3Bb1 resistance and intoxication in western corn rootworm by RNA sequencing. J. Appl. Entomol.142, 921–936 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willse, A., Flagel, L. & Head, G. Estimation of Cry3Bb1 resistance allele frequency in field populations of western corn rootworm using a genetic marker. G311, jkaa013 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Zhao, Z. et al. Differential gene expression in response to eCry3.1Ab ingestion in an unselected and eCry3.1Ab-selected western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte) population. Sci. Rep.9, 1–11 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao, Z., Elsik, C., Hibbard, B. & Shelby, K. Detection of alternative splicing in western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte) in association with eCry3.1Ab resistance using RNA-seq and PacBio Iso‐Seq. Insect Mol. Biol.30, 436–445 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flagel, L. E. et al. Western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera) transcriptome assembly and genomic analysis of population structure. BMC Genom.15, 1–13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niu, X. et al. Functional validation of DvABCB1 as a receptor of Cry3 toxins in western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera. Sci. Rep.10, 1–13 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coates, B. S. et al. A draft Diabrotica virgifera virgifera genome: insights into control and host plant adaption by a major maize pest insect. BMC Genom.24, 19 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heckel, D. G. How do toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis kill insects? An evolutionary perspective. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol.104, e21673 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castagnola, A. & Jurat-Fuentes, J. L. Intestinal regeneration as an insect resistance mechanism to entomopathogenic bacteria. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci.15, 104–110 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bravo, A., Pacheco, S., Gómez, I. & Soberón, M. Mode of action of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry pesticidal proteins. Adv. Insect Physiol.65, 55–92 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caccia, S. et al. Midgut microbiota and host immunocompetence underlie Bacillus thuringiensis killing mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.113, 9486–9491 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jurat-Fuentes, J. L., Heckel, D. G. & Ferré, J. Mechanisms of resistance to insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis. Ann. Rev. Entomol.66, 121–140 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frank, D. L., Zukoff, A., Barry, J., Higdon, M. L. & Hibbard, B. E. Development of resistance to eCry3.1Ab-expressing transgenic maize in a laboratory-selected population of western corn rootworm (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Entomol.106, 2506–2513 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao, Y. et al. Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis mediated by an ABC transporter mutation increases susceptibility to toxins from other bacteria in an invasive insect. PLoS Pathog.12, e1005450 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang, J. et al. Functional redundancy of two ABC transporter proteins in mediating toxicity of Bacillus thuringiensis to cotton bollworm. PLoS Pathog.16, e1008427 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Denecke, S. et al. Comparative and functional genomics of the ABC transporter superfamily across arthropods. BMC Genom.22, 1–13 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gahan, L. J., Pauchet, Y., Vogel, H. & Heckel, D. G. An ABC transporter mutation is correlated with insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin. PLoS Genet.6, e1001248 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merzendorfer, H. ABC transporters and their role in protecting insects from pesticides and their metabolites. Adv. Insect Physiol.46, 1–72 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Denecke, S., Fusetto, R. & Batterham, P. Describing the role of Drosophila melanogaster ABC transporters in insecticide biology using CRISPR-Cas9 knockouts. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol.91, 1–9 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amezian, D., Nauen, R. & Van Leeuwen, T. The role of ABC transporters in arthropod pesticide toxicity and resistance. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci.2024, 101200 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Ding, Y. et al. Multiple genes recruited from hormone pathways partition maize diterpenoid defences. Nat. Plants5, 1043–1056 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fabrick, J. & Wu, Y. Mechanisms and molecular genetics of insect resistance to insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis. Adv. Insect Physiol.65, 123–183 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huynh, M. P., Hibbard, B. E., Ho, K. V. & Shelby, K. S. Toxicometabolomic profiling of resistant and susceptible western corn rootworm larvae feeding on Bt maize seedlings. Sci. Rep.12, 1–13 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paddock, K. J., Dellamano, K., Hibbard, B. E. & Shelby, K. S. eCry3. 1Ab-resistant western corn rootworm larval midgut epithelia respond minimally to Bt intoxication. J. Econ. Entomol.116, 263–267 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Calles-Torrez, V. et al. Field-evolved resistance of northern and western corn rootworm (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) populations to corn hybrids expressing single and pyramided Cry3Bb1 and Cry34/35Ab1 Bt proteins in North Dakota. J. Econ. Entomol.112, 1875–1886 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tabashnik, B., Gould, F. & Carrière, Y. Delaying evolution of insect resistance to transgenic crops by decreasing dominance and heritability. J. Evol. Biol.17, 904–912 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fabrick, J. et al. A novel Tenebrio molitor cadherin is a functional receptor for Bacillus thuringiensis Cry3Aa toxin. J. Biol. Chem.284, 18401–18410 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo, Z. et al. Down-regulation of a novel ABC transporter gene (Pxwhite) is associated with Cry1Ac resistance in the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol.59, 30–40 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li, S. et al. A long non-coding RNA regulates cadherin transcription and susceptibility to Bt toxin Cry1Ac in pink bollworm, Pectinophora gossypiella. Pestic Biochem. Physiol.158, 54–60 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rajagopal, R., Sivakumar, S., Agrawal, N., Malhotra, P. & Bhatnagar, R. K. Silencing of midgut aminopeptidase N of Spodoptera litura by double-stranded RNA establishes its role as Bacillus thuringiensis toxin receptor. J. Biol. Chem.277, 46849–46851 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bolognesi, R. et al. Characterizing the mechanism of action of double-stranded RNA activity against western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte). PLoS one7, e47534 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao, J. Z. et al. mCry3A-selected western corn rootworm (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) colony exhibits high resistance and has reduced binding of mCry3A to midgut tissue. J. Econ. Entomol.109, 1369–1377 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu, Z. et al. Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin requires mutations in two Plutella xylostella ATP-binding cassette transporter paralogs. PLoS Pathog.16, e1008697 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pauchet, Y., Bretschneider, A., Augustin, S. & Heckel, D. G. A P-glycoprotein is linked to resistance to the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry3Aa toxin in a leaf beetle. Toxins8, 362 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Broehan, G., Kroeger, T., Lorenzen, M. & Merzendorfer, H. Functional analysis of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter gene family of Tribolium castaneum. BMC Genom.14, 1–19 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park, Y. et al. ABCC transporters mediate insect resistance to multiple Bt toxins revealed by bulk segregant analysis. BMC Biol.12, 1–15 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fonseca, S. S. et al. A soybean trypsin inhibitor reduces the resistance to transgenic maize in a population of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Econ. Entomol.116, 2146–2153 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guo, Z. et al. A single transcription factor facilitates an insect host combating Bacillus thuringiensis infection while maintaining fitness. Nat. Commun.13, 6024 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guo, Z. et al. The regulation landscape of MAPK signaling cascade for thwarting Bacillus thuringiensis infection in an insect host. PLoS Pathog.17, e1009917 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guo, Z. et al. MAPK-dependent hormonal signaling plasticity contributes to overcoming Bacillus thuringiensis toxin action in an insect host. Nat. Commun.11, 3003 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adegawa, S. et al. Cry toxins use multiple ATP-binding cassette transporter subfamily C members as low-efficiency receptors in Bombyx mori. Biomolecules14, 271 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liao, C. et al. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac protoxin and activated toxin exert differential toxicity due to a synergistic interplay of cadherin with ABCC transporters in the cotton bollworm. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.88, e02505–02521 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang, D. et al. Synergistic resistance of Helicoverpa armigera to Bt toxins linked to cadherin and ABC transporters mutations. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol.137, 103635 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sato, R. Utilization of diverse molecules as receptors by Cry toxin and the promiscuous nature of receptor-binding sites which accounts for the diversity. Biomolecules14, 425 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ludwick, D. C. et al. A new artificial diet for western corn rootworm larvae is compatible with and detects resistance to all current Bt toxins. Sci. Rep.8, 5379 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Meihls, L. N. et al. Comparison of six artificial diets for western corn rootworm bioassays and rearing. J. Econ. Entomol.111(6), 2727–2733 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huynh, M. P. et al. Characterization of thermal and time exposure to improve artificial diet for western corn rootworm larvae. Insects12, 783 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huynh, M. P. et al. Diet improvement for western corn rootworm (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) larvae. PLoS one12, e0187997 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pereira, A. E., Carneiro, N. P. & Siegfried, B. D. Comparative susceptibility of southern and western corn rootworm adults and larvae to vATPase-A and Snf7 dsRNAs. J. RNAi Gene Silencing12, 528–535 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rodrigues, T. et al. Validation of reference housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera). PLoS one9, e109825 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pereira, A. E. et al. Baseline susceptibility of a laboratory strain of northern corn rootworm, Diabrotica barberi (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) to Bacillus thuringiensis traits in seedling, single plant, and diet-toxicity assays. J. Econ. Entomol.113, 1955–1962 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pereira, A. E. et al. Assessing the single and combined toxicity of the bioinsecticide Spear® and Cry3Bb1 protein against susceptible and resistant western corn rootworm larvae (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Entomol.114, 2220–2228 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol.29, 644–652 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform.12, 1–16 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol.15, 1–21 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw transcriptomic sequencing data has been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive database on NCBI with Biosample accession numbers SAMN42392201-SAMN42392212 under the BioProject PRJNA1134000. All other pertinent data are found in the figures and tables. Request for data and additional information should be submitted to the corresponding author.