Abstract

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death in Turner syndrome (TS) for which arterial hypertension has a direct influence and is a key modifiable risk factor.

Objective

To investigate the prevalence and patterns of hypertension diagnosis and management in adult patients with TS who are registered in a large international multicentre database (TS-HTN study).

Methods

Retrospective multicentre observational study of patients aged ≥18 years included in the I-TS (International-TS) registry (2020–2022), using registry and participating centre-collected data.

Results

Twelve international centres participated, including 182 patients with a median age of 28 years (IQR 23–37.2). Arterial hypertension was recorded in 13.2% (n = 24). The median age at hypertension diagnosis was 27 years (range 10–56), with 92% aged less than 50 years at diagnosis. The majority (75%) were classified as primary hypertension (n = 18). In binomial regression analysis, higher body mass index was the only parameter significantly associated with the occurrence of hypertension (B = 1.487, P = 0.004). Among patients with aortic disease (n = 9), 50% had systolic BP ≥ 130 mmHg and 66.6% had diastolic BP ≥ 80 mmHg during the last clinic review. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors were the most common (n = 16) medication prescribed, followed by angiotensin receptor blockers (n = 6), beta-blockers (n = 6) and calcium channel blockers (n = 6).

Conclusions

Arterial hypertension is common in TS and occurs at a young age. Overweight/obesity was a notable risk factor for hypertension. The frequency of suboptimal BP control among high-risk patients highlights the importance of increased awareness and TS-specific consensus guidance on management.

Keywords: Turner syndrome, International Turner Syndrome Registry, hypertension

Introduction

Turner syndrome (TS) is a chromosomal disorder that is characterised by one intact X chromosome and the complete or partial absence of a second sex chromosome in phenotypic female individuals. This syndrome is characterised by short stature and premature ovarian failure (1). In comparison to the background female population, TS is associated with increased all-cause mortality that is predominantly driven by cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (2, 3). Women with TS have an increased risk of congenital heart disease, including bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) and coarctation of the aorta (4, 5). Furthermore, the risk of aortic dissection is elevated up to 100-fold in TS in contrast to the background female population, and this is the most common aetiology for excess cardiovascular mortality, with peak incidence reported in the third to fifth decades of life (4, 6). The largest risk factor for aortic dissection is hypertension. The risk of stroke is increased in TS and the incidence starts to elevate from the second decade of life (2, 4, 6, 7, 8). Moreover, a high prevalence of ischaemic heart disease is also noted with an influence on the excess mortality from the fifth decade onwards (2, 3, 8).

Women with TS have an increased risk of developing arterial hypertension (2, 4, 9), which has a direct influence on the excess mortality associated with this condition (2). Arterial hypertension is a key modifiable risk factor for aortopathy (6), ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease among these women (2, 9, 10). A more focused approach in risk factor control, including detection and management of arterial hypertension, is of vital importance in helping to reduce the increased morbidity and earlier onset of CVD in TS (6).

The prevalence of hypertension in adult women with TS is unclear, with reports varying from 13 to 58% (9). Up to now, arterial hypertension in adult women with TS was generally diagnosed and managed based on concepts and evidence derived from the general female population (9). However, the updated (2023) International Clinical Practice Guidelines for the care of girls and women with TS has recommendations for blood pressure cut-offs for diagnosis and management (11), while acknowledging that there is a lack of TS-specific data to guide.

The International Differences/Disorders of Sex Development (I-DSD) registry was launched in 2008, aiming to create a virtual research platform for this group of disorders (12). A specific module for TS (I-TS) was added to I-DSD in 2022 to facilitate focused research in this area. I-TS provides standardised patient data to facilitate research to expand the knowledge and understanding about this rare yet important disease entity, with a goal of improving and optimising care of women with TS. In view of its importance as a CVD risk factor in this group of girls and women with elevated vascular morbidity, we aimed to investigate the prevalence, patterns and characteristics of hypertension diagnosis and management in adult patients with TS who are registered in this powerful, large international multicentre database (TS-HTN study). TS-HTN was the first study to utilise I-TS registry data.

Methods

Study design and population

A retrospective multicentre observational study was conducted, and all centres registered in the I-DSD registry with patients aged ≥18 years with TS were invited to participate.

Data collection

Pseudo-anonymised data relevant to the study were directly extracted from the registry or clinicians of relevant centres were requested to complete a formatted spreadsheet. Baseline data included age, body mass index (BMI), age at TS diagnosis, karyotype, age at puberty, type of puberty, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) types, routes and daily doses. Specific details related to hypertension diagnosis included the occurrence of hypertension (diagnosis made by the clinicians of each I-DSD centre based on their individual clinical practice and guidelines for adults and paediatric patients, as there was no clear accepted guidance for hypertension diagnosis in TS at the time), age at diagnosis, systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) recorded at the diagnosis, family history of hypertension, type of hypertension and specific aetiology if categorised as secondary hypertension. Further details included the occurrence of aortic pathology, congenital heart disease, cardiac surgery and renal anomalies with specific details. In addition, data on the presence of pre-diabetes, diabetes and dyslipidaemia as diagnosed and recorded by clinicians in I-DSD centres based on locally adopted standard international diagnostic criteria for children and adults were included. The details of the occurrence of pregnancy, with specific details of hypertension during pregnancy (age of onset, antihypertensive use and maternal and foetal outcomes), were also included. Relating to the management of hypertension, SBP and DBP recorded at the most recent clinic review, details of antihypertensive medications and hypertension-related complications were also collected. Data collection was conducted from January 2022 to January 2023.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as percentage and frequency, and continuous variables were reported as the median and range or interquartile range (IQR 25th–75th percentile). The significance of differences between proportions (%) and medians was tested using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. A binomial logistic regression was performed to ascertain the effects of potential clinical variables on the likelihood of hypertension occurrence. P < 0.05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant difference, and 0.05 ≤ P < 0.10 was interpreted as a possible difference. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp., USA), statistical software package.

Ethics

SDMregistries is an international database of pseudonymised information on patients with a range of conditions affecting sex development and maturation and is approved by the National Research Ethics Service in the United Kingdom as a research database of information that is collected as part of routine clinical care (24/WS/0059). The data within this registry are deposited by clinicians following informed consent from patients or guardians.

Results

Base line characteristics

A total of 182 patients were included from 12 I-DSD centres in 11 countries (median number of cases per centre 6.5 (range 1–73)). Median age was 28 years (IQR 23–37.2), and the median age at TS diagnosis was 11 years (IQR 5.7–14). Monosomy X (45,X) was the most common karyotype (n = 76, 41.8%) reported (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of karyotypes.

| Karyotype | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 45,X | 76 (41.8%) |

| 45,X/46,XX | 45 (24.7%) |

| 45,X/46,XY | 16 (8.8%) |

| 46,X i(Xq) | 12 (6.6%) |

| 46,Xr (X)/46,XX | 6 (3.3%) |

| 46,XX del (p22.3) | 5 (2.7%) |

| Other | 22 (12%) |

Female sex hormone replacement

Seventy-four (40.7%) women needed pubertal induction, while 22 (12.1%) had spontaneous onset of puberty, and data were missing for 86 individuals (47.3%). The median age of oestrogen commencement in those requiring treatment was 14 years (range 8–47). Age-appropriate HRT was recorded in 109 individuals (59.9%), while eight (4.4%) were on combined oral contraceptive pills (missing data for 65 women). Of those receiving HRT, 52 (50.5%) were receiving transdermal preparations and 46 (44.7%) were on oral preparations (combined therapy in 8 women). The median oestrogen dose was 1.22 mg/day (range 0.02–3.2).

Comorbidities associated with TS

In the total cohort, 25.7% had aortic pathology (n = 33) (Table 2), including BAV (n = 15), coarctation of the aorta (CoA) (n = 9) and aortic dilatation (n = 9). Data on aortic pathology were missing for 52 individuals (29.7%). Twelve percent had undergone previous cardiac surgery or repair. Renal structural anomalies related to TS were reported in 16.5%, with horseshoe kidney being the most common (59%) abnormality.

Table 2.

Description of comorbidities associated with TS.

| TS related morbidity (n = data recorded) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Diseases of the aorta (n = 128) Coarctation of the aorta (BAV = 8, aortic dilatation = 2) Aortic dilatation only BAV (aortic dilatation = 5) |

33 (25.7%) 9 9 15 |

| Cardiac surgery (n = 126) Repair of coarctation of the aorta PDA closure Aortic valvotomy for aortic stenosis |

12 (9.5%) 9 2 1 |

| Renal abnormalities (n = 133) Horseshoe kidney Duplication of renal collecting duct system Hydronephrosis Cysts Bilateral small kidneys |

22 (16.5%) 13 6 1 1 1 |

| High body mass index (n = 91) Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) Obesity (>30 kg/m2) |

50 (55%) 31 19 |

| Diabetes/pre-diabetes (n = 83) | 7 (8.4%) |

| Dyslipidaemia (n = 78) | 22 (28.2%) |

TS: Turner syndrome; BAV: bicuspid aortic valve; PDA: patent ductus arteriosus.

Over half (55%) of the cohort were overweight (n = 31) or obese (n = 19) (Table 2). Abnormal blood glucose control (diabetes/pre-diabetes) was reported in 8.4%, while dyslipidaemia was recorded in 28.2%.

Characteristics of hypertension diagnosis and management

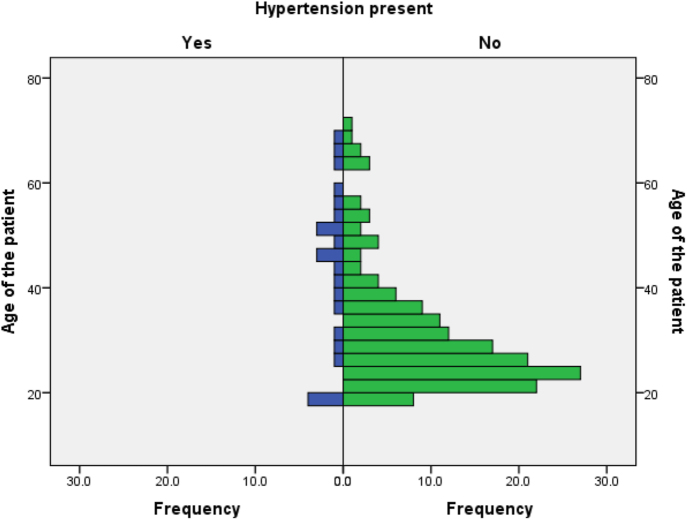

Arterial hypertension was reported in 13.2% (n = 24) of the total cohort. The median age at inclusion in the study was 45 years (range 18–67) (Fig. 1), and the median age at TS diagnosis was 10 years (range at birth: 34) in this group. The median age at hypertension diagnosis was 27 years (range 10–56), with 92% aged less than 50 years at diagnosis (69% were <40 years). At the time of hypertension diagnosis, median SBP was 150 mmHg (range 125–270) (noting lower values in paediatric patients) and median DBP was 90 mmHg (range 60–136). A positive family history of hypertension was recorded in four patients.

Figure 1.

Age distribution (at the inclusion in the study) of the cohort in relation to the hypertension diagnosis (n = 182).

Within the group with hypertension, the majority (75%) of hypertension cases were classified as primary hypertension (n = 18). Coarctation of the aorta (n = 3) and obesity (n = 2) were recorded as possible aetiologies for secondary hypertension by the clinicians of individual centres. Aetiology for secondary hypertension was not recorded for one individual. None of those with hypertension had structural renal abnormalities reported. There are no data available on a comprehensive screen for secondary causes among patients who were classified as primary hypertension.

No hypertension during pregnancy was reported in this cohort. Four patients with mosaic karyotype had four spontaneous pregnancies.

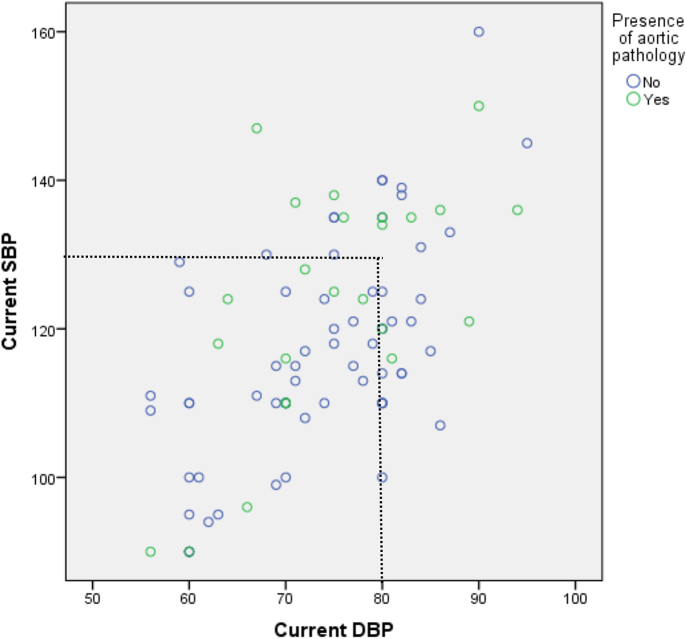

In the group with a diagnosis of hypertension, BP control was recorded at the most recent clinic visit: median SBP 118 mmHg (range 90–160) and median DBP 75 mmHg (range 56–95). Of patients with aortic disease (n = 9), 50% had SBP ≥130 mmHg and 66.6% had DBP ≥80 mmHg (Fig. 2). In patients without known aortic disease, 20% had SBP ≥130 mmHg (n = 3) and DBP ≥80 mmHg (n = 3).

Figure 2.

Blood pressure control recorded at the most recent clinic visit among patients with and without aortic pathology. Blood pressure data were available for 92 individuals (50.5%) of the total cohort and 22 individuals (91.7%) with hypertension diagnosis. DBP:diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Eleven patients received single antihypertensive medications, while the remainder required combination therapy: two agents (n = 8), three agents (n = 2) and four agents (n = 1). No data were available on antihypertensive medications in two patients. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) were the most common (n = 16) medication prescribed, followed by angiotensin receptor blockers (n = 6), beta-blockers (n = 6) and calcium channel blockers (n = 6). Alpha-blockers (n = 1) and thiazide/loop diuretics (n = 4) were other medications used for BP control.

Association of hypertension and TS-related morbidity

The group of women with hypertension was significantly older than those without hypertension (hypertension vs non-hypertensive: 45 years (IQR 30–52) compared with 27 years (IQR 23–34, P = 0.01) and had higher BMI (hypertension vs non-hypertensive: 28.4 kg/m2 (IQR 25.1–36.2) compared with 24.7 kg/m2 (IQR 21–28), P = 0.02). 45,X karyotype was more common in the hypertensive group (P = 0.04). Aortic pathology (composite of BAV and CoA) was not significantly associated with hypertension (P = 0.37).

There was no association of hypertension occurrence with age at TS diagnosis (P = 0.83), puberty type (spontaneous vs induced, P = 0.12), HRT route (P = 0.79), age of oestrogen commencement (hypertension vs non-hypertensive: 15 years (IQR 14–17) compared with 14 years (IQR 12–16), (P = 0.53), daily oestrogen dose (hypertension vs non-hypertensive: 1.1 mg (IQR 1–1.5) compared with 1.38 mg (IQR 0.29–2), (P = 0.72) or daily progesterone dose (hypertension vs non-hypertensive: 10 mg (IQR 5–10) compared with 24.7 mg (IQR 21–28), P = 0.40). In addition, the occurrence of hypertension was not associated with renal anomalies (P = 0.55), previous cardiac surgery (P = 0.40) or the presence of other metabolic risk factors such as diabetes (P = 0.06) and dyslipidaemia (P = 0.14).

Regression analysis

Binomial regression analysis was performed to predict a diagnosis of hypertension with age, 45,X karyotype, BMI and the presence of aortic abnormalities as dependent variables (Table 3). Higher BMI was the only parameter significantly associated with the occurrence of hypertension (B = 1.487, P = <0.01). Although the presence of 45,X karyotype was more common (P = 0.04 above), this did not reach statistical significance (B = 17.010, P = 0.07) on regression analysis.

Table 3.

Binomial logistic regression analysis for hypertension occurrence.

| X2 = 20.956, P = <0.001 independent | Dependent: hypertension present | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Odds ratio | 95% CI lower bound | 95% CI upper bound | P value | |

| Age | 0.04 | 1.041 | 0.989 | 1.097 | 0.127 |

| Karyotype 45,X | 1.356 | 3.880 | 0.885 | 17.010 | 0.072 |

| BMI | 0.238 | 1.268 | 1.081 | 1.487 | 0.004 |

| Aortic pathology | 0.478 | 1.613 | 0.325 | 8.001 | 0.558 |

BMI:body mass index; CI:confidence intervals.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest multicentre observational study to describe the characteristics of hypertension in adult women with TS (TS-HTN) and the first study to utilise data included in the I-TS module of the I-DSD registry. We observed a higher prevalence of hypertension (13%) in this cohort, with younger age at onset (69% were diagnosed before 40 years of age), when compared to the background female population (∼8%) (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england#resources; 13) and an association with increased BMI. The data also highlight the variable blood pressure control achieved in those with hypertension, particularly those with co-existing aortic pathology.

In this relatively young cohort, arterial hypertension was reported to be primary in the majority (75%) of the patients (although details of screening for secondary causes were limited), whereas hypertension is more likely secondary to a distinct pathology in younger patients with hypertension in the background population (14). The young age of diagnosis of hypertension is notable but unexplained although other comorbidities such as abnormal liver biochemistry are also noted to have their onset at a relatively young age. However, the observed prevalence of hypertension was notably lower in our cohort when compared to most of the published observational studies in TS, with a reported prevalence range from 13 to 58% (5, 10, 15, 16) (notwithstanding considerable heterogeneity in study designs, sample sizes, BP recording methods (single office BP vs ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM)) and BP cut-offs used for the diagnosis of hypertension). The lack of universal availability of AMBP monitoring may have led to undiagnosed hypertension in our cohort (4, 9, 17, 18), whereas office BP monitoring may over-diagnose hypertension in normal healthy women (13). Overweight/obesity (P = <0.01) was the only parameter that could predict hypertension occurrence among patients with TS in this study; although there was a trend towards a potential association of 45,X karyotype, which is associated with the most severe phenotype of TS, and hypertension occurrence, this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07) in regression analysis. There was no association between hypertension occurrence with age of oestrogen commencement, type or route of HRT. Notably, the reported median oestradiol dose was low in this study population (1.22 mg/day (range 0.02–3.2)). Importantly, there was a high prevalence of suboptimal BP control among high-risk patients, where 50% of patients with aortic disease had SBP ≥130 mmHg, which is the current consensus target. This is a significant finding in view of the known association of hypertension in at-risk groups with progression of aortic disease.

The precise mechanisms driving the high prevalence of hypertension among children and adult women with TS (4, 9, 10) may include the high prevalence of overweight/obesity. Recent evidence suggests that primary hypertension in TS is more likely driven by its increased association with metabolic syndrome as women with TS are observed to have increased BMI, free fat mass, visceral fat storage and reduced physical activity, which are recognised risk factors for metabolic syndrome (19, 20, 21). These factors potentially increase the risk of high blood pressure due to activation of systemic and renal sympathetic nervous system (SNS), activation of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), activation of renal sodium absorption and volume expansion, hyperleptinemia, impaired chemo-baro-receptor reflexes and increased perivascular fat (22). Furthermore, women with TS have significantly higher resting heart rates (23, 24), corresponding higher norepinephrine levels (25), impaired ability to modulate the sympatho-vagal tone in response to orthostatic stimulation (24, 25, 26) and the absence of nocturnal BP “dipping” 17), highlighting the possible direct effects of SNS activation (4, 6, 27), which is postulated to be related to abnormal embryonic development of the autonomic nervous system (4, 23, 25, 26). Moreover, early loss of the beneficial effects of oestrogen on SNS, RAAS, body mass, oxidative stress, endothelial function and salt sensitivity (28, 29) could also contribute to primary hypertension in women with TS, based on evidence from studies among women after menopause. However, the reported effects of HRT on BP control in post-menopausal women (30) or women with TS (23, 31) and primary ovarian insufficiency (32) are heterogenous due to differences in study designs, sample sizes and lack of standardisation of formulations, doses, types and routes of HRT. Moreover, more recent studies indicate that physiological oestrogen replacement (transdermal) is associated with lowering 24-h ABPM, whereas oral oestrogen may be associated with the increased risk of high BP among these women (30, 32). Structural heart disease is more common with 45,X karyotype and hence could predispose them to develop secondary hypertension or being treated for hypertension at a lower BP threshold (BAV and CoA) (1, 6, 19). CoA is reported in 7–14% of patients with TS (1), and half of the patients with secondary hypertension in our cohort had CoA. It is well known that patients with CoA are at risk of arterial hypertension in adult life despite surgical relief of obstruction at an very early age (usually in the neonatal period) (4, 15). However, we did not observe a significant association between hypertension diagnosis and the presence of aortic pathology in this cohort. While the increased prevalence of structural renal abnormalities theoretically could predispose women with TS to develop secondary hypertension, no studies (including this one) have shown any significant association. However, data on renal biochemistry were not available in our study.

Large epidemiological studies have shown a strong, independent and linear association between BP and CVD risk (33). The risk of CVD mortality appears to increase from BP levels as low as SBP of 115 mmHg and DBP of 75 mmHg in the general population (33). However, longitudinal data on BP cut-offs that increase the risk of CVD do not exist in women with TS. Nevertheless, a 23-year prospective cohort (n = 198) of patients with TS reported that aortic dissection was more commonly found in those requiring treatment for hypertension (HR 7.20, 95% CI 1.93–26.79) (34). Despite the current BP treatment targets in TS being extrapolations of evidence coming from large epidemiological studies performed among the background general population (age groups of 40–89 years, in whom highest prevalence of hypertension is noted) (33), the applicability of such extrapolations in patients with TS is questionable (4, 35). Discussions of possible diagnostic cut-offs vary (130–140/80 mmHg), as well as management goals (<120–135/80–85 mmHg) (9, 36, 37, 38), and are often based on single-centre studies or reviews of small observational studies. While acknowledging the sparsity of evidence, new (2023) International Clinical Practice Guidelines for TS recommends mean SBP >130 mmHg and mean DBP >80 mmHg over at least two measurements to make the diagnosis of hypertension in women with TS (11). Regarding BP management targets, in the presence of aortic pathology, the updated recommendations are to follow the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guideline for aortic disease (2022) and to follow general adult hypertension guidelines when no aortic pathology is present (11).

Regarding pharmacological treatment, there are limited data regarding optimal antihypertensive agents in TS; use of BBs and ARBs mainly relies on supportive evidence of benefit in women with aortic pathology, given convincing evidence coming from other conditions associated with aortic anomalies, including Marfan’s syndrome (MS) (9, 38). Studies on MS show that therapy with BB reduces the rate of aortic growth by decreasing proximal aortic shear stress and heart rate (39, 40), while therapy with ARBs reduces aneurysm expansion (animal models) and slows progression of aortic root dilatation (paediatric patients with MS, n = 18) (39). ACEis and CCBs have also shown the ability to reduce ejection impulse (40), and ACEis inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis in in vitro studies (40). BBs and ACEis/ARBs are logical in women with TS, given the evidence of increased risk of elevated basal heart rate due to sympathetic overactivity (4) and activation of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone. Use of antihypertensive agents in our cohort represents incorporation of general clinical practice guidelines of hypertension management in adults (the majority of women were treated as first line with ACEis (67%), while ARBs, BB and CCBs were reported in 25%). However, the new International TS guidelines recommend beta-blockers and ARBs in the presence of aortic dilatation, while recommending following standard adult hypertension guidelines in the absence of aortic disease (ARB or ACEi ± thiazide or CCB) (11). Non-pharmacological interventions, including lifestyle modification focusing on weight loss, should also be of important consideration in managing hypertension in this group of patients, as weight loss is associated with lowering of systolic and diastolic BP in large population studies, hence incorporated in general adult hypertension guidelines (41). This is highlighted, given that high BMI was the strongest risk factor for hypertension occurrence in this patient group.

This was the first study to utilise patient data from the I-DSD/I-TS registry; hence, sample size was limited due to the relatively small number of centres involved with this study, variability of patient recruitment processes of participating centres and limited awareness of recruitment of individuals with TS. This could affect the generalisability of the outcomes in the wider population. However, inclusion of patients from multiple international centres in this study has helped to describe the diverse practice relating to the occurrence and management of hypertension in TS. There are potential confounders including differing local criteria for diagnosis of hypertension, variable access to healthcare and lack of standardised screening for secondary causes of hypertension. We hope that with the dedicated I-TS subsection of I-DSD and increased awareness of the Registry, the number of recruits will allow studies including larger international populations in the future. Inter/intra-individual and centre-related variation in BP recording and interpretation and unavailability of ABPM data are important limitations of our study. Future prospective studies utilising the proposed BP criteria by the updated international guideline on TS for the diagnosis of hypertension will provide more clear understanding of the burden of this condition. The data on assessment of secondary causes were limited among patients who were classified as primary hypertension, and in the future, in alignment with the updated TS guidelines, investigations for secondary causes may be helpful. Incomplete availability of details of aortic assessment (29.7%) and small sample size have restricted the analysis of the relationship of aortopathy and hypertension. Data on renal function or basis of diagnosis of pre-diabetes, diabetes and dyslipidaemia similarly rely on individual centre criteria, and there were missing data for pubertal induction and hormone replacement. The relatively young age group, led to insufficient meaningful data regarding hypertension related mortality, chronic complications or pregnancy. In the future, well-designed large prospective observational studies are needed to identify appropriate BP cut-offs related to specific outcomes in TS, i.e., aortic dissection, ischaemic heart disease, stroke and all-cause mortality.

Conclusions

Women with TS have a high prevalence of arterial hypertension compared to the background female population, and notably, hypertension occurs at a young age. Overweight/obesity was a significant risk factor for hypertension, and therefore, strong consideration of non-pharmacological management, including lifestyle measures, is important in this group. Suboptimal clinic-recorded BP control, including those with aortic disease, highlights the importance of increased awareness and TS-specific consensus guidance on management.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this work.

Funding

This work did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request.

Acknowledgements

Publication supported by Oxford Endocrine Masterclass. We wish to thank all the patients whose data were included in this study.

References

- 1.Gravholt CH, Andersen NH, Conway GS, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: proceedings from the 2016 Cincinnati International Turner syndrome meeting. Eur J Endocrinol 2017. 177 G1–G70. ( 10.1530/EJE-17-0430) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoemaker MJ, Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, et al. Mortality in omen with Turner syndrome in Great Britain: national cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008. 93 4735–4742. ( 10.1210/jc.2008-1049) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stochholm K, Juul S, Juel K, et al. Prevalence, incidence, diagnostic delay, and mortality in Turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006. 91 3897–3902. ( 10.1210/jc.2006-0558) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones L, Blair J, Hawcutt DB, et al. Hypertension in Turner syndrome: a review of proposed mechanisms, management and new directions. J Hypertens 2023. 41 203–211. ( 10.1097/HJH.0000000000003321) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Bryman I & Wilhelmsen L. Cardiac malformations and hypertension, but not metabolic risk factors, are common in Turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001. 86 4166–4170. ( 10.1210/jcem.86.9.7818) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mortensen KH, Andersen NH & Gravholt CH. Cardiovascular phenotype in turner syndrome--integrating cardiology, genetics, and endocrinology. Endocr Rev 2012. 33 677–714. ( 10.1210/er.2011-1059) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gravholt CH, Juul S, Naeraa RW, et al. Morbidity in Turner syndrome. J Clin Epidemiol 1998. 51 147–158. ( 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00237-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chenbhanich J, Ungprasert P & Kroner PT. Inpatient epidemiology, healthcare utilization, and association with comorbidities of Turner syndrome: a national inpatient sample study. Am J Med Genet A 2023. 191 1870–1877. ( 10.1002/ajmg.a.63217) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Groote K, Demulier L, De Backer J, et al. Arterial hypertension in Turner syndrome: a review of the literature and a practical approach for diagnosis and treatment. J Hypertens 2015. 33 1342–1351. ( 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000599) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elsheikh M, Casadei B, Conway GS, et al. Hypertension is a major risk factor for aortic root dilatation in women with Turner's syndrome. Clin Endocrinol 2001. 54 69–73. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01154.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gravholt CH, Andersen NH, Christin-Maitre S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol 2024. 190 G53–G151. ( 10.1093/ejendo/lvae050) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucas-Herald AK, Ali SR, McMillan C, et al. I-DSD: the first 10 years. Horm Res Paediatr 2023. 96 238–246. ( 10.1159/000524516) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad A & Oparil S. Hypertension in women. Hypertension 2017. 70 19–26. ( 10.1161/hypertensionaha.117.08317) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wenger NK, Arnold A, Bairey Merz CN, et al. Hypertension across a Woman's life cycle. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018. 71 1797–1813. ( 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.033) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Los E, Quezada E, Chen Z, et al. Pilot study of blood pressure in girls with Turner syndrome. Hypertension 2016. 68 133–136. ( 10.1161/hypertensionaha.115.07065) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hjerrild BE, Mortensen KH, Sørensen KE, et al. Thoracic aortopathy in Turner syndrome and the influence of bicuspid aortic valves and blood pressure: a CMR study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2010. 12 12. ( 10.1186/1532-429X-12-12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nathwani NC, Unwin R, Brook CG, et al. Blood pressure and Turner syndrome. Clin Endocrinol 2000. 52 363–370. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.00960.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee YJ, Kim SM, Lee YA, et al. Relationship between systolic hypertension assessed by 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and aortic diameters in young women with Turner syndrome. Clin Endocrinol 2019. 91 156–162. ( 10.1111/cen.13995) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gravholt CH, Viuff M, Just J, et al. The hanging ace of Turner syndrome. Endocr Rev 2023. 44 33–69. ( 10.1210/endrev/bnac016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis SM & Geffner ME. Cardiometabolic health in Turner syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2019. 181 60–66. ( 10.1002/ajmg.c.31678) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gravholt CH, Hjerrild BE, Mosekilde L, et al. Body composition is distinctly altered in Turner syndrome: relations to glucose metabolism, circulating adipokines, and endothelial adhesion molecules. Eur J Endocrinol 2006. 155 583–592. ( 10.1530/eje.1.02267) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parvanova A, Reseghetti E, Abbate M, et al. Mechanisms and treatment of obesity-related hypertension—part 1: Mechanisms. Clin Kidney J 2024. 17 sfad282. ( 10.1093/ckj/sfad282) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gravholt CH, Naeraa RW, Nyholm B, et al. Glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, and cardiovascular risk factors in adult Turner's syndrome. The impact of sex hormone replacement. Diabetes Care 1998. 21 1062–1070. ( 10.2337/diacare.21.7.1062) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuckerman-Levin N, Zinder O, Greenberg A, et al. Physiological and catecholamine response to sympathetic stimulation in Turner syndrome. Clin Endocrinol 2006. 64 410–415. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02483.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gravholt CH, Hansen KW, Erlandsen M, et al. Nocturnal hypertension and impaired sympathovagal tone in Turner syndrome. J Hypertens 2006. 24 353–360. ( 10.1097/01.hjh.0000200509.17947.0f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brun S, Berglund A, Mortensen KH, et al. Blood pressure, sympathovagal tone, exercise capacity and metabolic status are linked in Turner syndrome. Clin Endocrinol 2019. 91 148–155. ( 10.1111/cen.13983) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esler M. The 2009 Carl Ludwig lecture: pathophysiology of the human sympathetic nervous system in cardiovascular diseases: the transition from mechanisms to medical management. J Appl Physiol 2010. 108 227–237. ( 10.1152/japplphysiol.00832.2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabbatini AR & Kararigas G. Estrogen-related mechanisms in sex differences of hypertension and target organ damage. Biol Sex Differ 2020. 11 31. ( 10.1186/s13293-020-00306-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coylewright M, Reckelhoff JF & Ouyang P. Menopause and hypertension: an age-old debate. Hypertension 2008. 51 952–959. ( 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.105742) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalenga CZ, Metcalfe A, Robert M, et al. Association between the route of administration and formulation of estrogen therapy and hypertension risk in postmenopausal women: a prospective population-based study. Hypertension 2023. 80 1463–1473. ( 10.1161/hypertensionaha.122.19938) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peppa M, Pavlidis G, Mavroeidi I, et al. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on endothelial function, arterial stiffness and myocardial deformation in women with Turner syndrome. J Hypertens 2021. 39 2051–2057. ( 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002903) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langrish JP, Mills NL, Bath LE, et al. Cardiovascular effects of physiological and standard sex steroid replacement regimens in premature ovarian failure. Hypertension 2009. 53 805–811. ( 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.126516) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mills KT, Stefanescu A & He J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol 2020. 16 223–237. ( 10.1038/s41581-019-0244-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thunström S, Krantz E, Thunström E, et al. Incidence of aortic dissection in Turner syndrome. Circulation 2019. 139 2802–2804. ( 10.1161/circulationaha.119.040552) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stefil M, Kotalczyk A, Blair JC, et al. Cardiovascular considerations in management of patients with Turner syndrome. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2023. 33 150–158. ( 10.1016/j.tcm.2021.12.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conway GS, Band M, Doyle J, et al. How do you monitor the patient with Turner’s syndrome in adulthood? Clin Endocrinol 2010. 73 696–699. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03861.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turtle EJ, Sule AA, Bath LE, et al. Assessing and addressing cardiovascular risk in adults with Turner syndrome. Clin Endocrinol 2013. 78 639–645. ( 10.1111/cen.12104) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin AE, Prakash SK, Andersen NH, et al. Recognition and management of adults with Turner syndrome: From the transition of adolescence through the senior years. Am J Med Genet A 2019. 179 1987–2033. ( 10.1002/ajmg.a.61310) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/sir/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. Circulation 2010. 2010 121. ( 10.1161/cir.0b013e3181d4739e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lacro RV, Dietz HC, Wruck LM, et al. Rationale and design of a randomized clinical trial of β-blocker therapy (atenolol) versus angiotensin II receptor blocker therapy (losartan) in individuals with Marfan syndrome. Am Heart J 2007. 154 624–631. ( 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.06.024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McEvoy JW, McCarthy CP, Bruno RM, et al. ESC guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension: Developed by the task force on the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and endorsed by the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE) and the European Stroke Organisation (ESO). Eur Heart J 2024. 2024 ehae178. ( 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae178) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a