Abstract

Natural jellyfish collagen (JC) has garnered significant attention in the field of hemostasis due to its oceanic origin, nontoxicity, biodegradability, and absence of complications related to diseases and religious beliefs. However, the hemostatic performance of pure JC is limited by its poor stability, adhesion to wet tissue, and mechanical properties. We developed a novel (HJP) sponge comprising JC, protocatechuic acid (PA), and hydroxybutyl chitosan (HS) to enhance the application of JC in emergency hemostasis. This sponge exhibits antibacterial properties, good biocompatibility, wet tissue adhesion, and hemostatic capabilities. The HJP sponge demonstrates excellent thermal stability and mechanical strength (tensile strength: ∼106.6 kPa, compressive strength at 70% compressive strain: ∼1013.5 kPa) and strong wet tissue adhesion (∼117.1 kPa). Upon application to a wound, the HJP sponge rapidly forms a wound seal, achieving effective hemostasis through the synergistic action of PA and JC. The blood loss was also reduced to 0.105 g when compared to a commercial gelatin sponge. This JC-based sponge, with its multifaceted characteristics, holds significant promise for rapid hemostasis in clinical applications.

1. Introduction

Rapid wound hemostasis materials have become a prominent subject of global research, attracting significant attention from both scientists and clinicians.1−3 Studies consistently indicate that excessive blood loss is a primary factor contributing to fatalities in emergencies such as war, traffic accidents, and clinical procedures.4 While commonly used hemostatic materials, including sodium alginate, chitosan, Celox, gauze, Hemcon, and gelatin sponge, have proven effective in clinical settings, they often present limitations when addressing severe bleeding. For example, chitosan powder can disperse easily, rendering it a less effective local hemostatic agent, while gauze exhibits limited hemostatic capabilities, particularly in cases of uncontrollable bleeding from internal organs.4,5 Pure collagen sponge has gained popularity due to their role in the coagulation cascade.4,6 However, none of the available collagen sponges are suitable for hemostasis and sealing in cases of aortic and cardiac trauma due to their slow hemostatic performance and inadequate adhesion to wet tissue surfaces. Additionally, the poor mechanical strength and antibacterial properties of the pure collagen sponge present further challenges. Consequently, there is an urgent need to explore efficient and sustainable methods for modifying collagen sponges to enhance their functional properties and broaden their application scope.

To address the first challenge, the destruction of the interfacial hydration layer through techniques such as water absorption and water-involved reactions is essential for achieving strong wet adhesion. Inspired by the wet adhesive capabilities of small organisms like mussels, barnacles, and other marine life, several adhesive materials have been designed and developed.7−10 Notably, materials containing catechol groups, which are prevalent in mussel adhesive proteins, effectively disrupt the interfacial hydration layer and promote multiple interactions on wet tissue surfaces,8 significantly contributing to the advancement of robust wet tissue adhesives.

In addressing the second challenge, the incorporation of additional polymers such as chitosan,11 sodium alginate,12 hyaluronic acid,13 and bletilla striata polysaccharide14 has been shown to improve the mechanical properties and antibacterial activity of adhesive materials. This enhancement imparts new functional properties and broadens their potential applications in the medical field. Notably, chitosan-modified collagen stands out, as it not only enhances mechanical properties but also improves antibacterial efficacy.

Historically, collagen has primarily been extracted from terrestrial sources such as cattle and pigs.15 However, cultural and religious factors, along with concerns regarding communicable diseases, limit the use of collagen derived from these terrestrial origins, which often results in the waste of byproducts from fish and invertebrate organisms.15 Currently, these marine resources remain underutilized. Numerous studies indicate that jellyfish collagen (JC) may offer a superior alternative to collagen sourced from fish and terrestrial animals (such as cows and pigs), primarily due to its collagen content exceeding 60% and its homology to mammalian collagen types I, II, and V, which can be classified as “collagen type 0.”16,17 An overview of JC advantages compared with alternative sources of collagen is provided in Supporting Table S1. Therefore, this research aims to extract collagen from jellyfish as a cost-effective alternative to traditional collagen sources derived from mammals. Given the stability of the triple helix structure of JC, one of the most promising strategies involves utilizing hydroxybutyl chitosan (HS) modified JC. HS is a novel type of functionalized chitosan that exhibits reversible temperature-responsive sol–gel transitions, synthesized through a reaction with 1,2-epoxybutane.

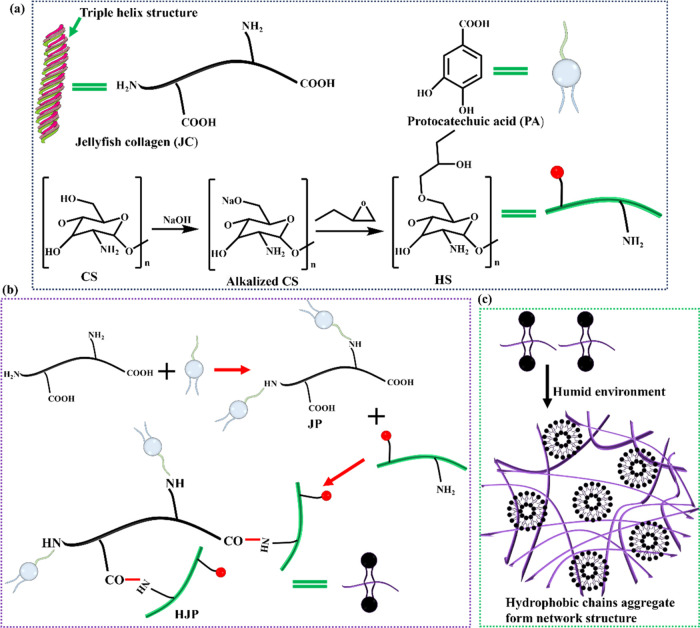

To enhance the hemostatic processing capability of collagen sponges, we aimed to develop sponges exhibiting antibacterial activity, improved wet tissue adhesion, and biocompatibility, utilizing HS, JC, and PA (Figure 1). The incorporation of PA significantly improved the wet tissue adhesion properties of the HJP sponge. Notably, the grafting of HS with JC markedly enhanced the mechanical properties and stability of the HJP sponge. Additionally, the combination of JC with HS demonstrated effective antibacterial properties and adhesion capacities, facilitating the repulsion of interfacial water through the aggregation of short alkyl chains. Upon exposure to body temperature, the HJP sponge gradually hydrates, forming a protective gel layer over the wound due to its wound-sealing capability and inherent antibacterial activity (Figure 1c). Given the limited mechanical and antibacterial properties of collagen materials, the potential to create JC sponge with excellent mechanical strength, strong adhesive characteristics, and antibacterial properties has garnered significant research interest. Overall, jellyfish-derived collagen may be a valid alternative not only to mammalian-derived collagen but also to other marine-derived collagens, as it contains over 60% collagen and exhibits homology to mammalian collagen types I, II, and V, which can be classified as “collagen type 0.”

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the preparation process of JC grafted PA and HS sponge. (a) Jellyfish collagen (JC), protocatechuic acid (PA), and preparation of hydroxybutyl chitosan (HS), respectively. (b) Schematic reaction routes of the HJP sponge. (c) The amphoteric in aqueous solution form a tridimensional network.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Chitosan (CS, the deacetylation >95% and the viscosity is 100–200 mPa s), sodium chloride (NaCl), protocatechuic acid (PA), 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl) carbodiimide (EDC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), and 1,2-epoxybutane were obtained from Shanghai Aladdin Industrial Co., Ltd. Dibasic sodium phosphate (Na2HPO4) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were provided by Sigma-Aldrich Co. Ltd. Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8), high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), and fetal bovine serum was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The fresh jellyfish was purchased at a Zhanjiang port wharf seafood market (China).

2.2. Extract Collagen from Jellyfish

Collagen was extracted from jellyfish using an acid combined enzyme method, with slight modifications based on the approach outlined by Mano et al.18 Jellyfish specimens of intact and uniform size were selected, and sediment and impurities were removed using deionized water before being cut into small pieces measuring 5 × 5 mm2. The jellyfish pieces were then immersed in acetone at a ratio of 1:5 (w/v) for 2 to 3 days to eliminate fat and soft tissue, after which the acetone was replaced with deionized water. Subsequently, the jellyfish was soaked in an appropriate volume of 0.1 M Na2HPO4 solution for 12 h, with intermittent stirring every 4 h, after which the water was decanted to separate noncollagenous proteins. The jellyfish samples were weighed and further soaked in a 0.05 M citric acid solution containing 1.5% pepsin (1:2, w/v) for 72 h with continuous magnetic stirring. The resulting mixture was centrifuged at 13,000g for 30 min, and the supernatant was retained. To salt out the collagen from the supernatant, NaCl (2 M) was added and stirred magnetically for 8 h, followed by another centrifugation at 13,000g for 30 min to collect the precipitate. The precipitate was then redissolved in a 0.05 M citric acid solution, and the supernatant was dialyzed, concentrated, and freeze-dried to obtain jellyfish collagen (JC). The JC was stored in a refrigerator at −20 °C for later use. All procedures were conducted at low temperatures (4 °C) or in an ice bath. Figure S1 provides a schematic diagram illustrating the process flow for the JC extraction.

2.3. Synthesis of Hydroxybutyl Chitosan (HS)

The thermosensitive polymer, HS, was synthesized using 1,2-epoxybutane and chitosan (CS).19 Initially, a specified amount of CS powder was dispersed in a 50% (w/w) NaOH solution and stirred for 24 h to achieve a stable CS/NaOH dispersion at a concentration of 0.2 g/mL. The alkalized CS was then completely dissolved in 200 mL of an isopropanol/water mixture (8:2), and 80 mL of 1,2-butene oxide was slowly added at a temperature of 50 °C over a period of 24 h. The reaction was terminated by adjusting the pH to 7. The final product was purified by dialysis against deionized water for 3 days, followed by freeze-drying to obtain HS sponge.

2.4. Synthesis of JC Grafted with Hydroxybutyl Chitosan and Protocatechuic Acid (HJP) Sponge

The HJP sponges are synthesized through the reaction of the amino group from JC with the carboxyl group of PA to form JP. Subsequently, HJP was linked via a condensation reaction between the amino group of carboxyl HS and JP. The specific protocol was as follows: First, 1.54 g (10 mmol) of PA was dissolved in 10 mL of a hydrochloric acid solution (pH = 5.5) and stirred for 30 min to ensure complete dissolution. Subsequently, EDC (3.10 g, 20 mmol) and NHS (1.15 g, 10 mmol) were added to the above solution, followed by continuous stirring for 1 h to activate the carboxyl groups of PA, resulting in what is referred to mixture A. Second, 3.0 g of JC was dissolved in 10 mL of hydrochloric acid solution (pH = 5.5) and stirred for 12 h to achieve complete dissolution, designated as mixture B. Third, solutions A and B were combined in a flask and stirred for 24 h. Upon completion of the reaction, the JP sponge was obtained through dialysis and freeze-drying. The preparation method for the HJP sponge was similar to that of the JP sponge. All reactions were conducted at 4 °C using EDC·HCl/NHS. The HJP sponges were subsequently recovered via dialysis and freeze-drying and were stored in a refrigerator prior to use.

2.5. Characterization of the Sponge

The sponge was analyzed using 1H NMR spectroscopy with deuterated water as the solvent (Bruker Avance III, 400 MHz). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed to characterize the sponge, utilizing a scan range of 4000–500 cm–1 (TENSOR27). Microstructural observations of the HJP sponge were conducted by using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss Sigma 300). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was utilized to evaluate the thermal decomposition behavior of the HS, JC, JP, and HJP sponges. Thermal properties were assessed by using a thermogravimetric analyzer (Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC3+) under a nitrogen atmosphere, with a heating rate of 10 °C/min from 30 to 600 °C.

2.6. Mechanical Properties of the Sponge

The mechanical properties of the sponge were characterized through compression and tensile tests conducted using an electronic universal tensile testing machine equipped with a 100 N load cell at 25 °C. For the compression tests, the sponge was formed into cylinders with a diameter of 20 mm and a height of 10 mm, subjected to a strain rate of 2 mm/min until reaching 80% strain. The dumbbell-shaped sponges, measuring 2 mm in width, 10 mm in height, and 1.5 mm in thickness, were tested to failure at a rate of 50 mm/min. Each compression and tensile test was performed in triplicate.

2.7. Wet Tissue Adhesion Ability of the Sponge

The wet tissue adhesion ability of the sponge was evaluated by using an electronic universal tensile testing machine to assess the adhesive strength of the sponge on wet tissue surfaces. Fresh pig skin, purchased from a local market, was cut into cube blocks measuring approximately 2 × 1 × 0.5 cm3. Prior to the experiment, the surface of the pig skin was cleaned with alcohol and gauze to remove the impurities. The sponge was applied to the pig skin with a contact area of 1 × 1 cm2 and was pressed using a 100 g weight at 37 °C for 30 min. Each sample was then stretched at a rate of 50 mm/min until separation occurred between the sponge and pig skin.

2.8. Antibacterial Assay of the Sponge

The sponge (0.5 g) was added to a suspension of the bacteria Escherichia coli or Staphylococcus aureus (10 μL, 1 × 106/mL) along with LB (990 μL) in a 24-well plate and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, 100 μL of the diluted bacterial solution was spread onto plate count agar. Following an additional 12 h incubation at 37 °C, the number of bacterial colonies was counted, and the antibacterial rate was calculated.

2.9. Biocompatibility of the Sponge

The biocompatibility of the sponge was assessed by using CCK-8 testing, live/dead assays, and cell migration assays. The CCK-8 assay involved human umbilical vein vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs). The sponge was dissolved in DMEM (4.5 g/L) supplemented with 10% FBS to achieve a final concentration of 20 mg/mL at 4 °C for 24 h. A suspension of HUVECs containing 2000 cells per 100 μL was added to a 96-well plate and incubated for 4 h in DMEM (4.5 g/L) with 10% FBS at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere to allow adherence to the plate surface. Following this incubation, the sponge-containing medium was used to replace the original medium, and the cells were cultured for an additional 24, 48, and 72 h. HUVECs cultured in a complete medium without treatment served as the control. After the designated culture times, a CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated for an additional hour. The optical density (OD) of the samples was measured by using a microplate reader at 450 nm. Cell viability was calculated according to eq 1

| 1 |

In eq 1, ODs and ODn are the OD of the sponge and control, respectively (n = 5).

In addition, the live/dead cell staining kit to observe cell viability was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.10. In Vivo Hemostasis Properties of the Sponge

A rat model of hepatic hemorrhage was employed for the experiment. Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats were anesthetized by using isoflurane and positioned at a 30° angle on a soft surgical plate. A precise wound measuring 10 mm in length and 5 mm in depth was created on the liver of each rat. Subsequently, sponges measuring 25 mm in length and 20 mm in width were applied to the wound, and hemostasis was monitored. After the dressing was removed and no bleeding was observed, the filter paper, which had absorbed the blood, was weighed to determine its final weight. The blank control group did not receive any material applied to the wound, while the positive control group was treated with a medical hemostatic sponge as a dressing. The amount of bleeding was calculated based on the difference in the weight of the filter paper before and after blood loss. The hemostasis time and blood loss were recorded.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structure and Physical Properties of JC and HJP

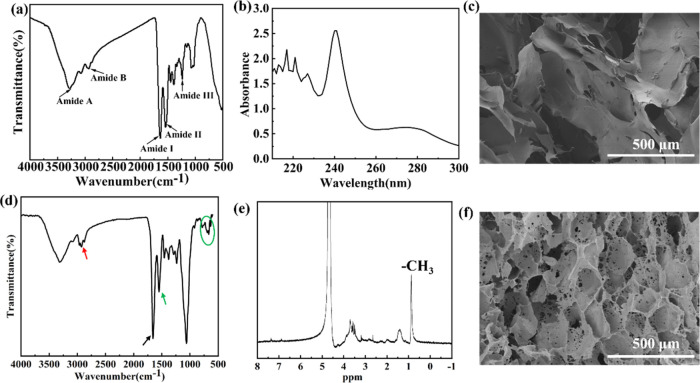

Changes in the secondary structure and functional groups of collagens were characterized by FTIR spectroscopy.20 As shown in Figure 2a, the observed amide A, amide B, amide I, amide II, and amide III of the JC were detected at wavenumbers of 3277, 2935, 1635, 1539, and 1236 cm–1, respectively. Our FTIR results are consistent with those reported by Liu et al. and Nalinanon et al.,20,21 who demonstrated that the triple helix structure of collagen remains intact. Studies have shown that the stability of the triple helix structure is attributed to the abundance of glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline in collagen. This structure exhibits a maximum absorption peak at approximately 230 nm in the ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectrum.20Figure 2b indicates that the JC exhibited maximum absorbance peaks at 240 nm. Liu et al. reported maximum absorption peaks for grass carp collagen, grass carp scales collagen, and crucian carp collagen at 235, 235, and 234 nm,20 respectively. This variation is likely due to differences in amino acid content and composition among collagens derived from different sources. SEM analysis revealed that the JC possesses flake-like structures (Figure 2c). Figure 2d presents the FTIR spectra of HJP, which displayed typical characteristic peaks of 1,2-epoxybutane, with peaks at 2964 and 1457 cm–1 attributed to the C–H stretching and bending of the CH3 group, respectively. Additionally, a characteristic band corresponding to C=C in the benzene ring was observed at 1551 cm–1, along with peaks assigned to C–H in plane bending in the benzene ring at 922 and 693 cm–1 (light green oval). Figure 2e illustrates the 1H NMR patterns of the HJP, where the hydrogen atoms of the benzene ring of the PA peaks are observed at 7.62–6.90 ppm. The peaks observed at 0.6 and 1.2 ppm were attributed to the −CH3 and −CH2– groups of the hydroxybutyl moiety, respectively. Overall, the thermosensitive chitosan and catechol moieties were successfully conjugated to the carboxyl and amino groups of JC. In comparison to pure JC, the microstructure of the HJP exhibits significant changes. SEM analyses revealed that the HJP sponge displayed a highly interconnected 3D porous structure resembling a disc-like form (Figure 2f).

Figure 2.

(a) FTIR, (b) UV, and (c) SEM images of JC. (d) FTIR, (e) 1H NMR, and (f) SEM images of HJP.

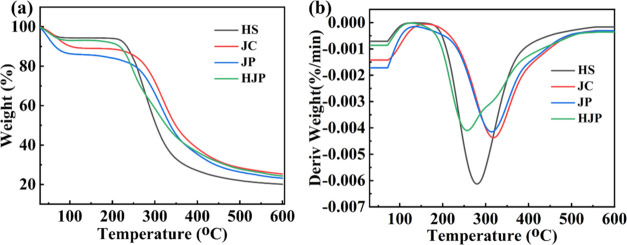

3.2. TG Analysis of HJP Sponge

The rapid decomposition of collagen due to heat is a significant factor that limits its broad application. Grafting treatments have emerged as one of the most efficient and economical methods for modifying collagen. For instance, Plepis et al. reported the incorporation of mangosteen peel extract into chitosan and collagen to enhance the thermal stability of collagen.22 Similarly, Selvaraj et al. developed hybrid collagen scaffolds by cross-linking collagen with inulin, while also incorporating ZrO2 nanoparticles. This approach improved the thermal stability of the collagen scaffolds, specifically enhancing it to 96 °C.23Figure 3a,b illustrates the heat stability of the HJP sponge. As depicted in Figure 3a, the weight loss of the four sponges exhibited similar patterns and occurred in two stages. Notably, the sponge experienced rapid weight loss between 250 and 400 °C due to the decomposition of certain oxygen-containing groups. Table S2 summarizes the data from Figure 3a, including the temperatures at 5 and 10% weight loss (T5% and T10%), the maximum degradation temperature (Tmax), and the char residue (Y) at 600 °C. The T5% and T10% values for pure JC are recorded at 66.5 and 103.1 °C, with the temperature corresponding to the fastest weight loss rate at 317 °C. In comparison, the T5% and T10% values for JP were lower, at 47.5 and 65.6 °C, respectively. This phenomenon may be attributed to the PA grafted onto JC, which affects the stability of the JC triple helix. In contrast, the T5% and T10% values for HJP were improved to 63.3 and 217.1 °C, primarily due to HS grafted with JP. Additionally, the char residue at 600 °C increased to 24.3%, which is 20.1 and 23.1% higher than that of HS and JP, respectively. Notably, HJP exhibited a significantly lower Tmax (254 °C) compared to JC (317 °C), likely due to the labile oxygen-containing functional groups in PA and HS being grafted onto JC, resulting in the generation of CO, CO2, and steam.24

Figure 3.

Thermogravimetric (TG) analysis. (a)TG and (b) DTG of four sponges.

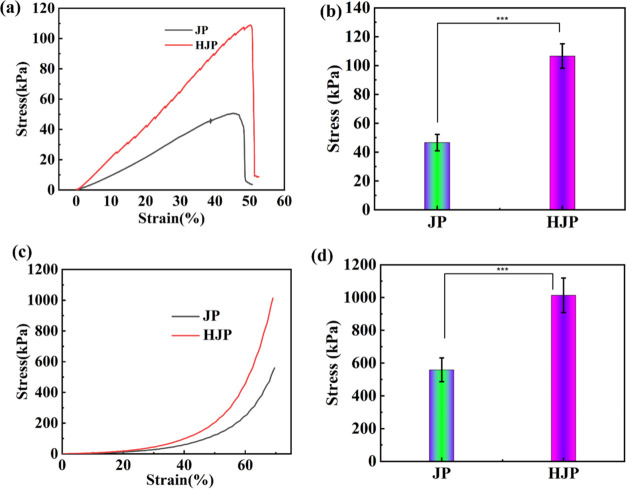

3.3. Mechanical Analysis of HJP Sponge

HJP sponge, as a novel hemostatic dressing, exhibits robust mechanical hemostatic properties that support their beneficial application. When subjected to movement or friction, the HJP sponge deforms without breaking. Consequently, the tensile strength and compressive strength of sponge was evaluated through tensile and compressive testing. The results for the tensile strength and compressive strength of JP and HJP sponges are presented in Figure 4. Specifically, the tensile stress–strain curve and compressive strength of HJP sponge are illustrated in Figure 4a,b, respectively. The tensile strain curves indicate that the strains of JP and HJP extended to 50.7 and 52.6%, respectively, while the tensile strengths were measured at 46 ± 5.7 and 106.6 ± 8.5 kPa, respectively (see Figure 4a,b). Compared to pure JP sponge, the tensile properties of HJP sponge were significantly enhanced. Similarly, the compressive strength of the HJP sponge reached 1013.5 ± 105.3 kPa at 70% compressive strain. This enhancement in mechanical properties can be attributed to multiple strengthening and toughening mechanisms. Specifically, (1) the introduction of a rigid chitosan host network significantly improves the mechanical properties of the HJP sponge;8,25 (2) the HJP network contains a substantial number of carboxyl and amino groups, which promote the formation of numerous covalent and noncovalent bonds, such as inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonds. The amino groups on HS and carboxyl groups on PA form covalent bonds, resulting in a significant enhancement of the mechanical strength of the HJP sponge.26

Figure 4.

(a) Tensile and (c) compressive stress–strain curves of compression performance of HJP sponge. (b) Tensile strength and (d) compressive strength of HJP sponge.

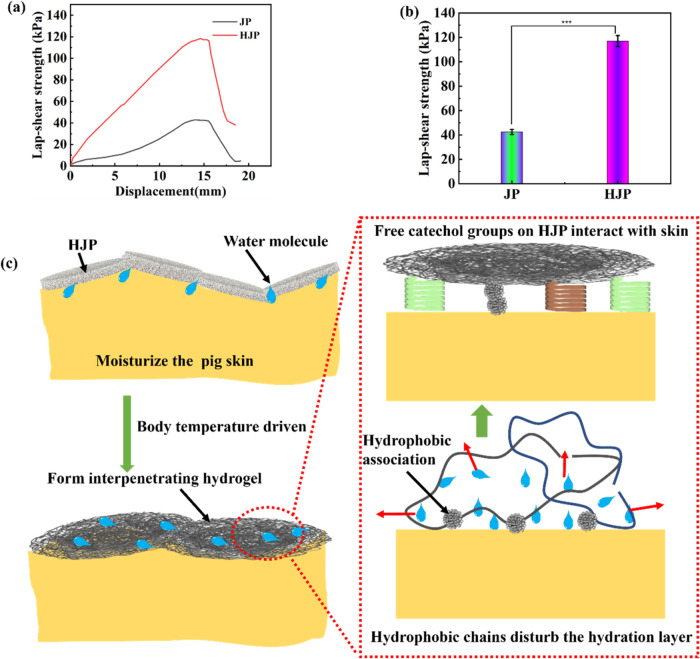

3.4. Bioadhesive Properties of HJP Sponge

As a powerful skin wound dressing, in addition to exhibiting strong mechanical performance, it should also possess moist tissue adhesion properties to effectively seal the wound and reduce blood loss.27 The adhesive strength of the HJP sponge was evaluated using a lap-shear adhesion test, with the results summarized in Figure 5. Notably, the adhesive strength of the HJP sponge reached 117.1 ± 4.5 kPa, while the JP sponge exhibited a strength of 42.5 ± 2.1 kPa on pig skin surfaces (Figure 5a,b). These data demonstrate that the sponge adheres well to the wound site. Previous studies have shown that electrically charged water-soluble sponge dressings possess adhesive properties to tissue.28 HJP sponge displayed remarkable wet adhesion to tissue compared to JP, with an increase in strength attributed to the grafting of HS in the sponge. The hydrophobic alkyl chain in HJP disrupts the hydration layer on the surface of pig skin, allowing the free catechol groups in HJP to interact with the tissue surface through cation−π, π–π, and hydrogen bond interactions.8,10,28,29 Furthermore, the quinone moiety, which is the oxidized form of the catechol group, can form covalent bonds with the -NH2, −OH, –SH, and −COOH groups, thereby enhancing adhesion to the skin surface.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of (a) the lap shear test and (b) the adhesive strength of HJP sponge. (c) Schematic diagram of the adhesion between the hydrogel and tissue.

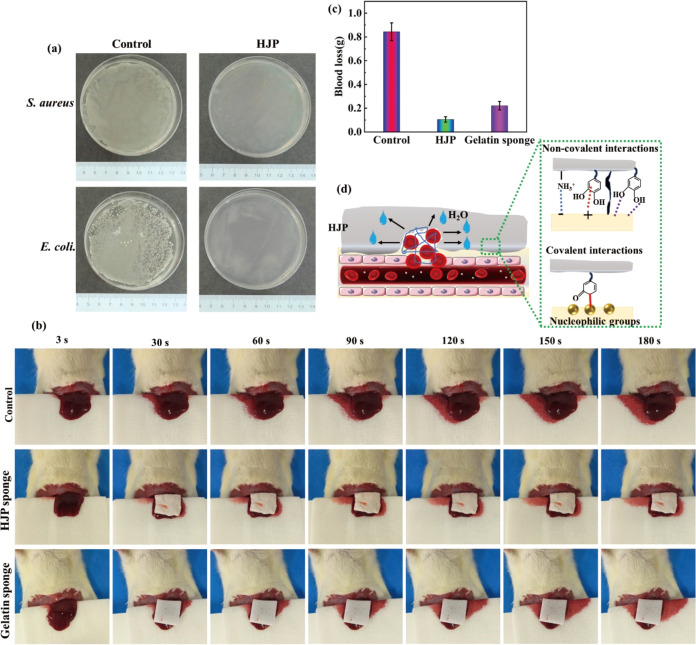

3.5. Antibacterial Properties of HJP Sponge

Once a wound is formed, particularly wounds exposed to the air, the adhesion of bacteria and subsequent wound infection become significant concerns.30 Therefore, the antibacterial performance of the sponge is a critical criterion for evaluating the quality of hemostatic materials. Previous studies have demonstrated that HS alone exhibits very low antibacterial capability, with inhibition rates against S. aureus and E. coli reported to be less than 20 and 75%,31 respectively. PA, a plant-derived phenolic acid, has been documented to possess excellent antibacterial activity against both S. aureus and E. coli.32,33 Consequently, the antioxidant and antibacterial activities of JC can be enhanced through grafting with PA. As illustrated in Figure 6a, the number of colonies present in the presence of HJP sponge was significantly reduced compared to that in the control plates, indicating that the grafting of PA improved the antibacterial properties of the sponge. The antibacterial properties of the HJP sponge are better than that of collagen/DXG-AgNP1.34 The antibacterial ability is comparable to those of CHL and CHLY.35

Figure 6.

In vivo antibacterial and hemostatic performance of the HJP sponge. (a) Representative photographs of E. coli and S. aureus and against that of HJP sponge at 1 day. (b) In vivo hemostatic evaluation of various sponges. (c) Blood loss amounts. (d) Schematic diagram of hemostasis mechanism of HJP sponge.

3.6. Hemostatic Performance of HJP Sponge

To verify the hemostatic effects of the HJP sponge in vivo, a liver bleeding model was successfully established using SD rats. A gelatin sponge was employed as the positive control, whereas no treatment served as the negative control. Figure 6b illustrates the hemostatic outcomes after various hemostatic sponges that contacted the wound without the application of pressure. Compared to the control group (0.844 ± 0.075 g), the gelatin sponge reduced blood loss to 0.221 ± 0.035 g, whereas blood loss with the HJP sponge was reduced to 0.105 ± 0.027 g (Figure 6b). The blood loss associated with HJP sponge was found to be superior to that of the gelatin sponge, thereby demonstrating the potential of the HJP sponge as a hemostatic material. After achieving hemostasis, gently pressing the gelatin sponge with the hand resulted in a significant amount of blood flowing out of the gelatin sponge. In contrast, no blood loss was observed from the HJP sponge (Figure S2). The excellent hemostatic performance of HJP sponges can be attributed to their unique adhesive-based sealing properties, which aggregate blood cells and platelets (Figure 6d). Upon completion of hemostasis, the sponge is squeezed, and the absence of blood exudation indicates that the HJP sponge effectively absorbs water from the blood to rapidly form a sponge-gel complex. This process enhances the interaction between the sponge and wound, thereby improving its hemostatic capability (Figure S2). This phenomenon provides indirect evidence for the hemostatic mechanism of the HJP sponge. Research indicates that jellyfish collagen can activate the hemostatic mechanism through three mechanisms: platelet aggregation, fibrinogen digestion, and fibrin clot digestion.36 When the HJP sponge is applied to the wound, it rapidly adsorbs a large volume of blood and aggregates blood cells and platelets. Simultaneously, it forms an effective physical barrier to stop bleeding through noncovalent bonds (including electrostatic, cation-π, hydrophobic associations, and hydrogen bond interactions) as well as covalent bonds (such as Schiff bases).

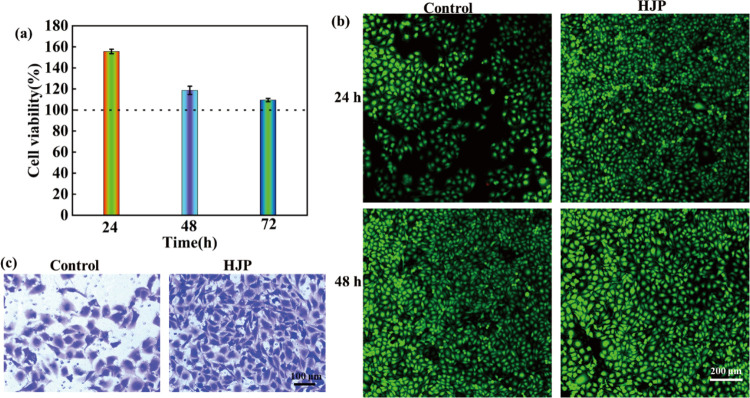

3.7. Biocompatibility of HJP Sponge

The biocompatibility of the HJP sponge was assessed using three methods: CCK-8, live and dead cell staining, and cell migration analysis. Overall, the cell viability of the HJP sponge was approximately 155% after 24 h of culture, confirming that the prepared hemostatic HJP sponge exhibits good biocompatibility. When the coculture time was extended to 24 and 72 h, the relative cell viability of the HJP sponge decreased from 155 to 109% (Figure 7a). Figure 7b illustrates the fluorescence of HUVEC cells following 24 and 48 h of coculture with the HJP sponge. The morphology and density of live cells in the HJP sponge were comparable to those of the control groups, suggesting that HJP sponge exhibits no cytotoxicity. Cell migration is a critical parameter for evaluating the cytocompatibility of hemostatic materials. As shown in Figure 7c, the number of migrating cells in the HJP sponge was greater than that in the control group, indicating that the HJP sponge demonstrated excellent cell compatibility.

Figure 7.

Biocompatibility of HJP sponge. (a) Cell viability of HJP sponge after 24, 48, and 72 h. The HJP sponge was dissolved in DMEM to a final concentration of 100 mg/mL. (b) Fluorescence images of HUVECs cocultured for 24 and 48 h with HJP sponge, respectively. (c) The migration of HUVECs after being cocultured with the HJP sponge for 12 h.

In summary, our results suggest that mineralization of the HJP sponge not only significantly altered its mechanical strength, adhesive characteristics, antibacterial properties, and hemostatic performance but also promoted HUVEC proliferation and migration. To enhance its clinical application, further research is necessary in areas such as material optimization, clinical trials, and long-term effect evaluation. With advancements in science and technology, the application of the HJP sponge is anticipated to play a more significant role in the future of the medical field.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a HJP sponge was successfully synthesized through a grafting reaction involving hydroxybutyl chitosan (HS), protocatechuic acid (PA), and jellyfish collagen (JC). HJP sponges possess excellent mechanical, wet tissue adhesion, antibacterial activity, and hemostatic capabilities. The enhancement of both noncovalent and covalent interactions significantly improved the mechanical properties of the HJP sponge. The HJP sponge exhibited excellent wet tissue adhesion, achieving a strength of 117 kPa. The excellent wet tissue adhesion properties are attributed to the synergistic effects of alkyl chain drainage and catechol, which together form an effective physical barrier to control bleeding. In vivo experiments indicated that the HJP sponge exhibited superior hemostatic performance compared to the gelatin sponge. Additionally, the HJP sponge displayed significant antibacterial activity and excellent cytocompatibility. Therefore, HJP sponges represent a promising hemostatic biomaterial for clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (A2024320).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c06103.

The advantages of jellyfish collagen over other collagen are obvious (Table S1). Flowchart of jellyfish collagen extraction (Figure S1). Once hemostasis is accomplished, squeeze the sponge covering the wound and a considerable amount of blood will flow out of the gelatin sponge (Figure S2). Representative parameters from TGA results (Table S1) (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ Z.W. and Y.S. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Nepal A.; Tran H. D. N.; Nguyen N.-T.; Ta H. T. Advances in haemostatic sponges: Characteristics and the underlying mechanisms for rapid haemostasis. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 27, 231–256. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X.; Zhao X.; Yuan L.; Ming H.; Li Z.; Li J.; Luo F.; Tan H. Bioinspired Injectable Polyurethane Underwater Adhesive with Fast Bonding and Hemostatic Properties. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11 (16), 2308538 10.1002/advs.202308538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan W.; Feng Y.; Tan J.; Zeng H.; Jalaludeen R. K.; Zeng X.; Zheng B.; Song J.; Zhang X.; Chen S.; Pan J. Carbonized Cellulose Aerogel Derived from Waste Pomelo Peel for Rapid Hemostasis of Trauma-Induced Bleeding. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11 (19), 2307409 10.1002/advs.202307409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding C.; Cheng K.; Wang Y.; Yi Y.; Chen X.; Li J.; Liang K.; Zhang M. Dual green hemostatic sponges constructed by collagen fibers disintegrated from Halocynthia roretzi by a shortcut method. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 24, 100946 10.1016/j.mtbio.2024.100946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y.; Yang R.; Wang H.; Li Y.; Fu C. Application of chitosan-based materials in surgical or postoperative hemostasis. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 994265 10.3389/fmats.2022.994265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y.; Tao F.; Wang J.; Chai Y.; Ren C.; Wang Y.; Wu T.; Chen Z. Development and evaluation of tilapia skin-derived gelatin, collagen, and acellular dermal matrix for potential use as hemostatic sponges. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127014 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An H.; Zhang M.; Huang Z.; Xu Y.; Ji S.; Gu Z.; Zhang P.; Wen Y. Hydrophobic Cross-Linked Chains Regulate High Wet Tissue Adhesion Hydrogel with Toughness, Anti-hydration for Dynamic Tissue Repair. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36 (8), 2310164 10.1002/adma.202310164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X.; Fang Y.; Zhou W.; Yan L.; Xu Y.; Zhu H.; Liu H. Mussel foot protein inspired tough tissue-selective underwater adhesive hydrogel. Mater. Horiz. 2021, 8 (3), 997–1007. 10.1039/D0MH01231A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Bai R.; Chen B.; Suo Z. Hydrogel Adhesion: A Supramolecular Synergy of Chemistry, Topology, and Mechanics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30 (2), 1901693 10.1002/adfm.201901693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Xu R.; Fang Y.; Weng Y.; Chen Q.; Wang Z.; Liu H.; Fan X. Biodegradable underwater tissue adhesive enabled by dynamic poly(thioctic acid) network. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151352 10.1016/j.cej.2024.151352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andonegi M.; Heras K. L.; Santos-Vizcaíno E.; Igartua M.; Hernandez R. M.; de la Caba K.; Guerrero P. Structure-properties relationship of chitosan/collagen films with potential for biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 237, 116159 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing X.; Li X.; Jiang Y.; Lou J.; Liu Z.; Ding Q.; Han W. Degradable collagen/sodium alginate/polyvinyl butyral high barrier coating with water/oil-resistant in a facile and effective approach. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 278, 118962 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q.; Torres J. E.; Hakim M.; Babiak P. M.; Pal P.; Battistoni C. M.; Nguyen M.; Panitch A.; Solorio L.; Liu J. C. Collagen- and hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels and their biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng., R 2021, 146, 100641 10.1016/j.mser.2021.100641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z.; Dan N.; Chen Y. Utilizing epoxy Bletilla striata polysaccharide collagen sponge for hemostatic care and wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 128389 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadar E.; Pesterau A. M.; Prasacu I.; Ionescu A. M.; Pascale C.; Dragan A. M. L.; Sirbu R.; Tomescu C. L. Marine Antioxidants from Marine Collagen and Collagen Peptides with Nutraceuticals Applications: A Review. Antioxidants 2024, 13 (8), 919 10.3390/antiox13080919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruqui N.; Williams D. S.; Briones A.; Kepiro I. E.; Ravi J.; Kwan T. O. C.; Mearns-Spragg A.; Ryadnov M. G. Extracellular matrix type 0: From ancient collagen lineage to a versatile product pipeline – JellaGel. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 22, 100786 10.1016/j.mtbio.2023.100786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaig I.; Radenković M.; Najman S.; Pröhl A.; Jung O.; Barbeck M. In Vivo Analysis of the Biocompatibility and Immune Response of Jellyfish Collagen Scaffolds and its Suitability for Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21 (12), 4518 10.3390/ijms21124518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho R. C. G.; Marques A. L. P.; Oliveira S. M.; Diogo G. S.; Pirraco R. P.; Moreira-Silva J.; Xavier J. C.; Reis R. L.; Silva T. H.; Mano J. F. Extraction and characterization of collagen from Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic squid and its potential application in hybrid scaffolds for tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 78, 787–795. 10.1016/j.msec.2017.04.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X.; Su Z.; Zhang W.; Huang H.; He C.; Wu Z.; Zhang P. An advanced chitosan based sponges dressing system with antioxidative, immunoregulation, angiogenesis and neurogenesis for promoting diabetic wound healing. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 29, 101361 10.1016/j.mtbio.2024.101361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L.; Lan W.; Wang Y.; Ahmed S.; Liu Y. Extraction and Characterization of Self-Assembled Collagen Isolated from Grass Carp and Crucian. Carp. Foods 2019, 8 (9), 396 10.3390/foods8090396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M.; Benjakul S.; Nalinanon S. Compositional and physicochemical characteristics of acid solubilized collagen extracted from the skin of unicorn leatherjacket (Aluterus monoceros). Food Hydrocolloids 2010, 24 (6), 588–594. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milan E. P.; Martins V. C. A.; Horn M. M.; Plepis A. M. G. Influence of blend ratio and mangosteen extract in chitosan/collagen gels and scaffolds: Rheological and release studies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 292, 119647 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalirajan C.; Behera H.; Selvaraj V.; Palanisamy T. In vitro probing of oxidized inulin cross-linked collagen-ZrO2 hybrid scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 289, 119458 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P.; Tuteja S. K.; Bhalla V.; Shekhawat G.; Dravid V. P.; Suri C. R. Bio-functionalized graphene-graphene oxide nanocomposite based electrochemical immunosensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 39 (1), 99–105. 10.1016/j.bios.2012.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X.; Huang J.; Zhang W.; Su Z.; Li J.; Wu Z.; Zhang P. A Multifunctional, Tough, Stretchable, and Transparent Curcumin Hydrogel with Potent Antimicrobial, Antioxidative, Anti-inflammatory, and Angiogenesis Capabilities for Diabetic Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16 (8), 9749–9767. 10.1021/acsami.3c16837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S.; Hu C. Y.; Xu X. Ammonia-responsive chitosan/polymethacrylamide double network hydrogels with high-stretchability, fatigue resistance and anti-freezing for real-time chicken breast spoilage monitoring. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131617 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Liu X.; Liu C.; Wang N.; Chen H.; Yao W.; Sun G.; Song Q.; Qiao W. A highly efficient, in situ wet-adhesive dextran derivative sponge for rapid hemostasis. Biomaterials 2019, 205, 23–37. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z.; Xiao J.; Huang S.; Wu H.; Guan S.; Wu T.; Yu S.; Huang S.; Gao B. A wet-adhesive carboxymethylated yeast β-glucan sponge with radical scavenging, bacteriostasis and anti-inflammatory functions for rapid hemostasis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 230, 123158 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X.; Zhou W.; Chen Y.; Yan L.; Fang Y.; Liu H. An Antifreezing/Antiheating Hydrogel Containing Catechol Derivative Urushiol for Strong Wet Adhesion to Various Substrates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12 (28), 32031–32040. 10.1021/acsami.0c09917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Ji N.; Li F.; Qin Y.; Wang Y.; Xiong L.; Sun Q. Dual Cross-Linked Starch–Borax Double Network Hydrogels with Tough and Self-Healing Properties. Foods 2022, 11 (9), 1315 10.3390/foods11091315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y.; Mu Y.; Hu Y.; Liu J.; Su C.; Sun X.; Chen X.; Jia N.; Feng C. Zinc-mineralized diatom biosilica/hydroxybutyl chitosan composite hydrogel for diabetic chronic wound healing. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 656, 1–14. 10.1016/j.jcis.2023.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C.; Tian L.; Lu J.; Gong G. A Novel Bioactive Antimicrobial Film Based on Polyvinyl Alcohol-Protocatechuic Acid: Mechanism and Characterization of Biofilm Inhibition and its Application in Pork Preservation. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17, 3319–3332. 10.1007/s11947-023-03309-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C.; Xu R.; Han X.; Tong L.; Xiong L.; Liang J.; Sun Y.; Zhang X.; Fan Y. Protocatechuic acid-mediated injectable antioxidant hydrogels facilitate wound healing. Composites, Part B 2023, 250, 110451 10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.110451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L.; Xu Y.; Li X.; Yuan L.; Tan H.; Li D.; Mu C. Fabrication of Antibacterial Collagen-Based Composite Wound Dressing. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6 (7), 9153–9166. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X.; Yang X.; Li P.; Xu Z.; Zhao L.; Mu C.; Li D.; Ge L. Antibacterial Conductive Collagen-Based Hydrogels for Accelerated Full-Thickness Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15 (19), 22817–22829. 10.1021/acsami.2c22932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadar E.; Pesterau A.-M.; Sirbu R.; Negreanu-Pirjol B. S.; Tomescu C. L. Jellyfishes—Significant Marine Resources with Potential in the Wound-Healing Process: A Review. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21 (4), 201 10.3390/md21040201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.