Abstract

Background

The continuous emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants and subvariants poses significant public health challenges. The latest designated subvariant JN.1, with all its descendants, shows more than 30 mutations in the spike gene. JN.1 has raised concerns due to its genomic diversity and its potential to enhance transmissibility and immune evasion. This study aims to analyse the molecular characteristics of JN.1-related lineages (JN.1*) identified in Italy from October 2023 to April 2024 and to evaluate the neutralization activity against JN.1 of a subsample of sera from individuals vaccinated with XBB.1.5 mRNA.

Methods

The genomic diversity of the spike gene of 794 JN.1* strain was evaluated and phylogenetic analysis was conducted to compare the distance to XBB.1.5. Moreover, serum neutralization assays were performed on a subsample of 19 healthcare workers (HCWs) vaccinated with the monovalent XBB.1.5 mRNA booster to assess neutralizing capacity against JN.1.

Results

Sequence analysis displayed high spike variability between JN.1* and phylogenetic investigation confirmed a substantial differentiation between JN.1* and XBB.1.5 spike regions with 29 shared mutations, of which 17 were located within the RBD region. Pre-booster neutralization activity against JN.1 was observed in 42% of HCWs sera, increasing significantly post-booster, with all HCWs showing neutralization capacity three months after vaccination. A significant correlation was found between anti-trimeric Spike IgG levels and neutralizing titers against JN.1.

Conclusions

The study highlights the variability of JN.1* in Italy. Results on a subsample of sera from HCWs vaccinated with XBB.1.5 mRNA booster vaccine suggested enhanced neutralization activity against JN.1.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12879-025-10685-0.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, JN.1, Genomic surveillance, Phylogenetic analysis, Neutralizing antibodies

Background

The rapid evolution of SARS-CoV-2 has led to the emergence of numerous variants, subvariants and circulating recombinant forms with distinct genetic and phenotypic characteristics [1, 2]. The continuous emergence and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants present significant challenges for public health, requiring a continuous monitoring of changes in the viral strain. SARS-CoV-2 variants, including those with increased transmissibility and potential immune escape, pose significant challenges to public health efforts and vaccine efficacy [3, 4]. One of the latest Omicron subvariant identified in 2023 was JN.1, which has emerged as a variant of interest due to its phylogenetic distance from previously dominant strains, such as the XBB.1.5 recombinant [5–7]. In fact, JN.1, firstly identified in August 2023, contains more than 30 mutations in the spike (S) protein coding gene [5]. For this reason, increased transmissibility and immune escape was hypothesized [5].

Hereby, the Italian JN.1* sequences identified from October 2023 to April 2024 were analysed, to evaluate the variability of this strain. Moreover, a subsample of sera collected from healthcare workers (HCW) boosted with the monovalent Omicron XBB.1.5-containing COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, was used to evaluate the serum neutralization capacity against JN.1.

Methods

Molecular analysis

Sequence collection

In Italy, the National Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ISS), in collaboration with the Ministry of Health (MoH) coordinates the genomic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. The network of collaborating laboratories includes more than 70 laboratories distributed throughout the country. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) data are routinely shared nationally and internationally through the “Italian COVID-19 Genomic” (I-Co-Gen platform, hosted at ISS) and “Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data” (GISAID)databases (https://gisaid.org/), respectively. The sequences uploaded to the national collaborative repository I-Co-Gen are automatically analysed and verified for completeness and timeliness after a quality review, ensuring a continuous flow of information for the early identification of new variants and/or mutations and for estimating their prevalence.

To the purpose of this study, 1,832 sequences belonging to JN.1-related lineages (JN.1*), obtained from October 2023 to April 2024, were downloaded from GISAID (last access 16/05/2024). The ID numbers of each sequence is listed in supplementary Table 4.

In addition, the JN.1 spike mutations were compared with those found among 1,835 Italian sequences belonging to XBB.1.5 and deposited in GISAID. Lineages were assigned using nextclade lineage V.3.2.1, as in the I-Co-Gen platform (last access16/05/2024).

Sequences cleaning

All JN.1* and XBB.1.5 genomes were aligned separately to the reference 'Wuhan-Hu-1’ (NC_045512.2) using MAFFT V.7.520 [8]. A python homemade program was developed to cut the spike gene without considering sporadic insertion and exclude the sequences with a spike coverage < 90%. After cleaning, 794 and 1,568 genomes were obtained for JN.1* and XBB.1.5, respectively. The two groups of spike sequences were aligned separately and together using MACSE V.2.07[9]. The results were manually curated using BioEdit V.7.7.1 (https://thalljiscience.github.io/) to exclude alignment artefacts. To realise the phylogenetic tree sequences were clustered with 100% identity using CD-HIT v. 4.8.1 [10].

Phylogenetic tree

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was obtained by running IQTREE V. 1.6.9 [11] on the overall multi-sequence alignment of Spike region of JN.1* and XBB.1.5, including the reference 'Wuhan-Hu-1’ (NC_045512.2), with 1000 bootstrap replications. The tree was rooted versus the 'Wuhan-Hu-1’ reference and the best substitution models was defined by ModelFinder (TIM + F + R4) included in IQTREE. The tree visualization was curated and visualised with FigTree V.1.4.4.

Sequence variability

The spike nucleotide and amino acid substitutions were identified using a homemade program. Signature mutations, present in the JN.1* and XBB.1.5 lineages, were identified using the Outbreak.info project (https://outbreak.info/) with a minimum threshold fixed at 75%. The Heatmap was constructed with the python mathplotlib library considering only the identified minor variants and excluding the JN.1* spike mutations identified as singleton. The python code was assisted by the Gemini 1.5 Flash by Google AI and OpenAI (2024), ChatGPT (Version GPT-4). The evolutionary divergence analysis within and between two sequences groups (XBB.1.5 and JN.1*) was conducted using the Maximum Composite Likelihood model included in MEGA11 [12] using default options.

Serological analysis

Study design and population

To the purpose of this study, samples from a subgroup of healthcare workers (HCW) enrolled in a larger multicentre longitudinal cohort study designed to monitor immune responses in individuals vaccinated with the monovalent Omicron XBB.1.5-containing COVID-19 mRNA vaccine were used. Specifically, serum samples were collected from 19 HCW enrolled at the Policlinico Riuniti University Hospital (Foggia, Italy) at the time of their vaccination with the Comirnaty Omicron XBB.1.5 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) (T0) and 3 months after vaccine administration (T1). At the time of enrollment, demographic data were collected from each participant, along with information regarding previous SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 vaccinations.

Serum preparation and storage

Blood samples (5 ml) were collected in Serum Separator Tubes (BD Diagnostic Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and centrifuged at room temperature at 1600 rpm for 10 min. Two serum aliquots were transferred to 2 ml polypropylene, screw cap cryo tubes (Nunc™, Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA), immediately frozen at −20 °C and thereafter stored at −80°C. Frozen sera were shipped to the Department of Infectious Diseases at Istituto Superiore di Sanità (DMI, ISS), in dry ice following biosafety shipment condition. Upon arrival serum samples were immediately stored at −80°C.

SARS-CoV-2 IgG immunoassays

Sera were evaluated using the DiaSorin Liaison SARS-CoV-2 trimeric Spike IgG assay on the LIAISON® XL chemiluminescence analyzer (DiaSorin, Saluggia, VC, Italy). The assay range is up to 2080 Binding Antibody Units (BAU/mL). According to manufacturer’s instructions, values ≥ 33.8 BAU/mL were interpreted as positive. If the results were above the assay range, samples were automatically diluted 1/20 and testing was repeated. Anti-Nucleocapsid IgG were measured by Anti-SARS-CoV-2 NCP ELISA assay (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany), which uses a modified nucleocapsid protein that only contains diagnostically relevant epitopes.

SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody assay

SARS-CoV-2 strain JN.1 (BA.2.86.1.1) lineage (EPI_ISL_18624895) was incubated with two-fold serial dilutions of serum samples starting at 1:8 dilution in D-MEM culture medium (Sigma Aldrich, Merck Life Science, Milan, Italy) supplemented with 1X penicillin/streptomycin (Corning, Glendale, AZ, USA) and 2% foetal bovine serum (Corning) in 96-well plates. Virus (100 TCID50) and serum mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After this incubation 10,000 cells (Vero/TMPRSS2-ACE2) per well were added and incubated at 37 °C for 5 days. The neutralization titer was calculated and expressed as microneutralization titer 50 (MNT50), i.e., the serum dilution capable of reducing the cytopathic effect to 50%.

Results

In order to assess the variability of JN.1 and its sub-lineages (JN.1*) identified in Italy, 794 sequences were used for analysis, based on the complete coverage of the spike gene.

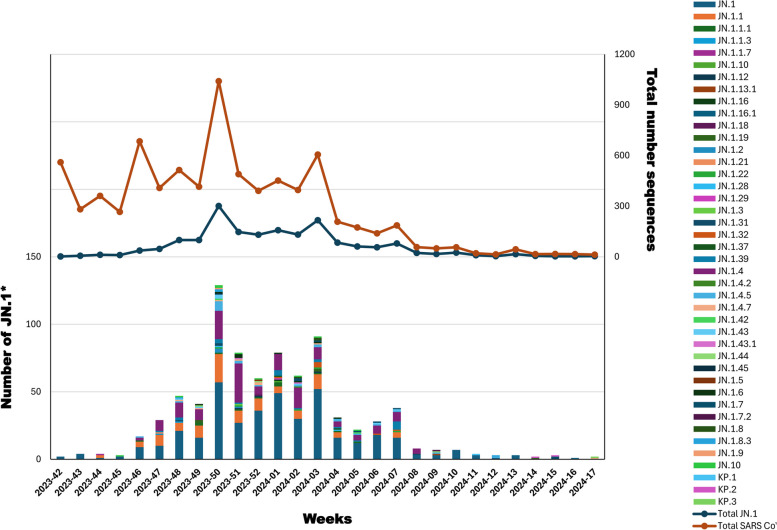

The lineage composition of the cleaned dataset and the trend of the total Italian SARS-CoV-2 vs JN.1* sequences, as present in GISAID, are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The lineage composition of the cleaned dataset and the trend of the total Italian SARS-CoV-2 vs JN.1* sequences, as present in GISAID. The lower part of the graph shows the JN.1* lineage assigned to the dataset of Italian sequences with spike coverage > 90%. The upper part of the graph includes the total number of JN.1* (blue) and SARS-CoV-2 (orange) sequences uploaded from Italy between October 2023 to April 2024

A total of 176 lineages were identified; among them, the parental lineage (JN.1) was detected until week 13–2024 with a median percentage of 52.3% (range 25%−100%). The number of JN.1* sequences, as well as lineage diversity, increased rapidly from week 45–2023 on. During the observation period, JN.1* did not represent the entirety of sequenced genomes. The fluctuations in the number of sequences loaded and analysed were similar to those downloaded from the GISAID dataset. Similarly, the cumulative number of SNPs identified within the spike gene varied over time, with the largest number of mutations identified in the receptor-binding domain (RBD—20,089 mutations vs 16,866 and 12,119 of N-terminal and C-terminal regions respectively. Figure 2A). Missense substitutions were the most common mutation type encountered (81.3%), followed by synonymous mutations (9.6%), insertions and deletions (1.2% and 7.9%, respectively). The complete list of mutations, excluded those considered singleton, is available in Table S1.

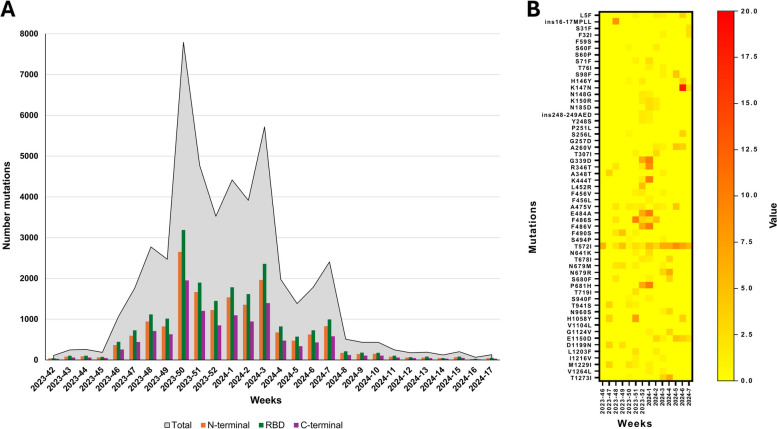

Fig. 2.

Spike gene mutations distribution over time. The mutations are represented by sampling week. A The grey area shows the total number of mutations found in the sequences in each week. The three bars indicate the mutation found in the N-Terminal (blue bar), RBD (green bar) and C-Terminal (orange bar) regions, respectively. B Heatmap of non-synonymous substitutions of unique sites among Italian JN.1*

The spike amino acid substitutions identified in the Italian dataset were compared to those reported in Outbreak.info to verify the presence of unique sites. A closer analysis of the non-synonymous substitutions revealed that none of the 48 unique mutations was predominant, with a weekly frequency not exceeding 17.9% (K147N, Fig. 2B). Furthermore, only one spike mutation (T572I), located within the C-terminal domain, was persistent throughout the entire period of analysis, although with a low percentage (range: 0%−9.1%).

The similarity between JN.1* and XBB.1.5 spike sequences was analyzed. The identified XBB.1.5 mutations are reported in supplementary Table 2.

The global predominant mutations of JN.1* and XBB.1.5 were compared and 29 mutations were found to be shared; of these, most were identified within the RBD domain (17/29), similarly to what was observed between the JN.1* and XBB.1.5 Italian sequences (supplementary Table 3).

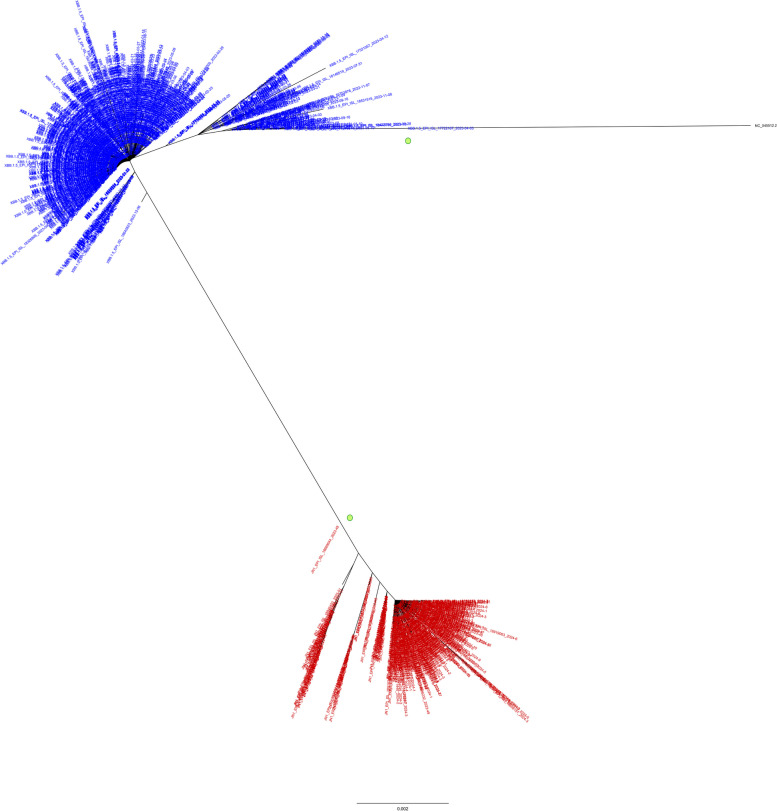

The average pairwise distance between the sequences within the Italian JN.1* group and the Italian XBB.1.5 group was estimated to be 8.8 × 10–4 and 6.2 × 10–4, respectively while the distance between the two groups was equal to 1.1 × 10–2. These values were congruent with the hierarchy shown in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

JN.1* and XBB.1.5 phylogenetic tree. Phylogenetic analysis of the spike gene of the Italian JN.1* (red) vs XBB.1.5 (blue) using a maximum likelihood approach with 1,000 replications. Only the principal nodes with bootstrap > 90% are indicated with green points

In order to investigate the ability of individuals vaccinated with XBB.1.5 to neutralize the newly spreading JN.1 variant, serum samples were collected from 19 healthcare workers (HCW) at the time of the monovalent XBB.1.5 mRNA vaccine booster and three months later.

Detailed demographic data of study participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and immunization status (vaccine and/or natural infection) of HCWs, Italy, 2023 (n = 19)

| Characteristics | Total (range) |

|---|---|

| Number of participants | 19 |

| Median age (years) | 47 (30–64) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 11 |

| Male | 8 |

| Number of vaccine doses | |

| 4 | 7 |

| 5 | 12 |

| Vaccine Type (4 dose) | |

| Comirnaty XBB.1.5 | 7 |

| Comirnaty BA.4/5 | 12 |

| Number of SARS-CoV-2 infections | |

| 0 | 6 |

| 1 | 12 |

| 2 | 1 |

All participants had previously received the two-dose primary COVID-19 vaccine cycle and the first mRNA booster, 12 (63%) had received 5 vaccine doses, including a second booster dose with the bivalent Comirnaty Original/Omicron BA.4/5 mRNA vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech), and 7 (37%) had received 4 vaccine doses, since they skipped the bivalent mRNA booster. Additionally, 63% had at least one documented SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 1). To avoid the influence of immunity induced by recent exposure to SARS-CoV-2, only individuals who tested negative for anti-Nucleocapsid (N) IgG antibodies at the time of vaccination (T0) were included in the study.

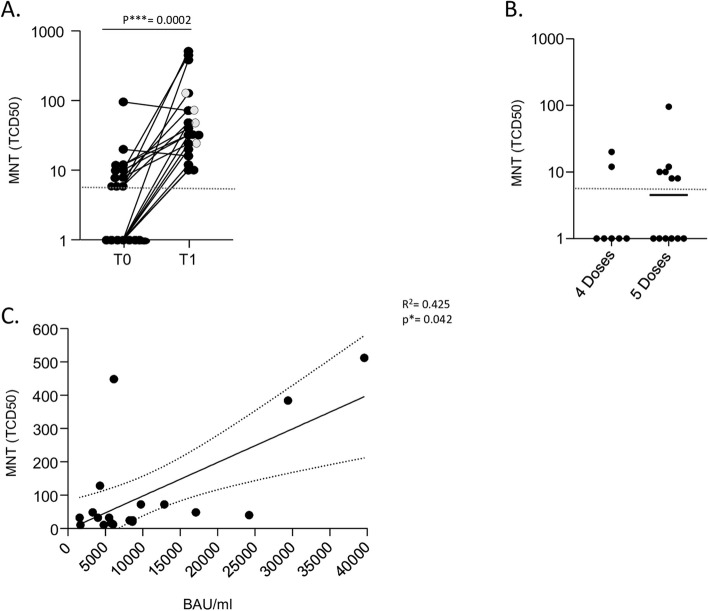

As shown in Fig. 4A, 42% of HCW’s sera (n = 8) exhibited neutralizing activity against the JN.1 variant prior to receiving the booster (T0); the median MNT50 value was 6 [IQR: 1–10]. Three months post-vaccination, the neutralizing ability increased significantly, with all 19 sera examined able to neutralize the JN.1 strain (median MNT50, 32 [IQR: 20–72]).

Analyzing MNT data based on previous vaccination history, we found that 50% of HCW, who had received five doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, including the bivalent Comirnaty Original/Omicron BA.4/5 mRNA vaccine as the second booster and the Comirnaty Omicron XBB.1.5 mRNA vaccine as the third booster, were able to neutralize JN.1 at T0. In contrast, only 28.6% (2 out of 7) of HCW who received XBB.1.5 vaccine as a fourth vaccine dose were able to neutralize JN.1 at T0 (Fig. 4B). To determine whether any HCWs had become infected with SARS-CoV-2 between the two time points, we tested T1 sera for anti-N IgG. Positive anti-N IgG titres were found in four individuals (Fig. 4A, grey dots). As shown in Fig. 4A, this did not translate in significant variations in the neutralizing ability of JN.1.

Fig. 4.

Serum neutralization results. A MN titers of sera of 19 HCWs at T0 and T1. Sera are used to neutralize JN.1 of BA.2.86 strains. Individual MNT50 are reported together with median values. Non-neutralizing sera (MNT < 8) are placed below the dotted line; statistical differences between two groups are calculated by the Kruskall-Wallis test (p < 0.05 are significant). Grey dots represent MNT50 values of sera from anti-N seroconverted subjects. B MN titers of sera of 19 HCWs (same sera in panel A) plotted according to the number of vaccine doses received. Non-neutralizing sera (MNT < 8) are placed below the dotted line. The median of values is represented by a continuous line. C Linear regression correlating the levels of anti-trimeric spike IgG titers with serum neutralization activity against JN.1 (r and P value are shown)

We investigated the correlation between Spike-specific IgG in serum and MNT against JN.1 using a standardized CLIA assay measuring IgG towards the original Spike protein (Wuhan) in its native trimeric form. A statistically significant correlation was found between trimeric anti-S IgG levels and MNT at T0 (data not shown) and at T1 (Fig. 4C). This suggests that higher anti-S IgG titres correspond to broader immunity and confer greater neutralizing ability.

Discussion

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of the spike gene of the JN.1 lineage and its sub-lineages, identified in Italy from October 2023 to April 2024, the period in which JN.1 spread across the country. The parental JN.1 lineage persisted throughout the observation period with an increase in JN.1* sequences from week 45–2023.

In addition, the presence of other co-circulating variants underlined the virus variability. This is consistent with global trends in the evolution of SARS-CoV-2, which has improved fitness and selective adaptation [13].

To assess the molecular variability of JN.1*, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the spike gene were investigated. The analysis showed a temporal variation in the mutation counts, with missense mutations predominating (81.3%), followed by synonymous (9.6%) and indels (1.2% and 7.9%, insertion and deletion, respectively) mutations. Farkas et al. [14] have argued that the predominant number of missense mutations compared to synonymous and indels mutations may reflect a higher viral fitness.

Signature mutations with a frequency > 20% were identified in the spike gene. Among the minority mutations in our dataset, only the amino acid substitution T572I showed a certain persistence, despite its low frequency (weekly range: 0%−9.1%). This suggests a potentially important function, as already described by Li et al. [15]. The T572I substitution increased the binding affinity to ACE2 receptors of various strains, potentially increasing host-susceptibility to infection [15].

Among the 69 signature spike mutations in JN.1, 29 were also identified in XBB.1.5.

The highest number of mutations was observed in the RBD region of the overall JN.1* Italian sequences (20,089 mutations vs 16,866 and 12,119 in N- and C-terminal regions, respectively), corroborating the key role of this region in the interaction with the host ACE2 receptor and in virus evolution. Therefore, to assess the evolutionary relationship between the JN.1* and XBB.1.5 lineages, a maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis was performed by comparing the sequences of the Italian spike gene. The resulting phylogenetic tree, built on the spike gene, suggests a clear separation between the two lineages, (https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/21112023_ba.2.86_ire.pdf?sfvrsn=8876def1_3), as also supported, in this study by a significant bootstrap (bootstrap > 90%). This result is consistent with the pairwise distances observed within the JN.1 and XBB.1.5 groups (8.8 × 10–4 and 6.2 × 10–4, respectively), which are less than the intergroup distance (1.1 × 10–2). This shows substantial genetic differentiation between the two lineages and suggests distinct evolutionary trajectories, in agreement with the phylogenetic results.

However, the RBD of JN.1* and that of XBB.1.5 showed a high number of shared mutations (17/29), although this region is substantially shorter than the other two (N- and C-terminal), highlighting the crucial role of this domain for ACE2 binding [6].

Evaluation of the neutralizing activity of the sera, prior to the booster dose with the monovalent XBB.1.5 mRNA vaccine, found that 42% of the HCWs had neutralizing activity against JN.1. This pre-booster neutralizing capacity likely reflects residual immunity from previous vaccinations and /or natural infections. In line with this hypothesis, the data suggest that the HCWs who had received a fourth vaccine dose 12 months prior to enrolment exhibited a higher neutralization activity against JN.1 at baseline T0 than those who had received only three vaccine doses. The significant increase in neutralizing activity three months post-booster underlines the efficacy of the XBB.1.5 mRNA vaccine in enhancing the immune response against JN.1. This finding is in line with previous studies indicating that booster doses can increase neutralizing antibody titres, even against phylogenetically distant variants, providing a broader antibody repertoire response [16–18].

The detection of positive anti-N IgG titres in four individuals at T1 suggests that breakthrough infections occurred between the two time points. However, there was no significant increase in neutralizing immunity compared to those who were anti-N IgG negative. The possibility of not seeing an increase in neutralising effect could be related to a threshold effect. It may be speculated that there is a limit or plateau in the immune response, where further breakthrough infections do not significantly enhance neutralizing antibodies. Several factors could contribute to this effect, such as immune system saturation, vaccine-induced immunity, variant specificity, and individual variability [19, 20].

A significant correlation was found between anti-trimeric S IgG levels and neutralizing titers against JN.1, both at T0 and T1. This indicates that higher levels of spike-specific IgG, directed towards the spike protein in its native trimeric form, are predictive of stronger neutralizing responses against SARS-CoV-2 variants. The correlation of spike-specific IgG levels with neutralizing titers might suggest their use as potential markers of immune response. These results are consistent with other studies that have shown higher anti-S IgG titres correlate with higher neutralizing capacity and broader immunity [21, 22].

However, the sample size of the sera was relatively small and the study population was limited to healthcare workers, considered to be at high risk of exposure. Moreover, the observed immune responses could be influenced by various factors, such as the timing and nature of prior infections and vaccinations. The lack of detailed information regarding the exact antigenic history represents a limitation to the evaluation of the results. Furthermore, the results focused only on neutralizing antibody responses, which are one of the components of the entire immune response. T-cell responses and other aspects of the immune system also play a key role in protection against SARS-CoV-2 virus and its variants [23].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides a detailed molecular analysis of the gene encoding the spike protein and, in particular, of the RBD region of JN.1 lineage and its sublineages (JN.1*) circulating in Italy from October 2023 to April 2024.

Moreover, the spike gene of XBB.1.5 is very different from that of JN.1, as demonstrated by the phylogenetic tree and pairwise diversity and confirmed also by the presence of 17 out of 29 mutations shared by the two strains in the RBD region.

The RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein mediates viral attachment to the ACE2 receptor and is a major determinant of host range and a dominant target of neutralizing antibodies. Therefore, the neutralising ability of sera after booster vaccination with the monovalent XBB1.5 mRNA vaccine was investigated. Overall, the results obtained show that the XBB.1.5 mRNA booster vaccine significantly improves the neutralizing activity against the JN.1 variant, suggesting that, despite the differences between the two viral strains, a conserved antigenic epitope may be present on the RBD and that it remains unchanged.

The correlation between anti-Spike IgG levels and neutralizing capacity underlines the potential of these antibodies as markers of the immunity response after vaccination and/or previous viral infection.

These findings highlight the importance of monitoring viral mutations of SARS-CoV-2 variants and performing in vitro experiments to assess the neutralization capacity of immunized sera, as well as to conduct further research to explore the role of other immune components against SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1. Supplementary Table 1: JN.1* mutations identified among the genomes object of this study.

Supplementary Material 2. Supplementary Table 2: XBB.1.5 mutations identified among the genomes object of this study.

Supplementary Material 3. Supplementary Table 3: Comparison of XBB.1.5 and JN.1* signature positions.

Supplementary Material 4. Supplementary Table 4: ID of sequences analysed downloaded from GISAID repository and analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all the authors and all the originating laboratories responsible for obtaining the specimens, as well as all the submitting laboratories where genetic sequence data were generated and shared via the GISAID Initiative, on which this research is based.

The authors thank: Stefano Morabito, Arnold Knijn, Gabriele Vaccari, Ilaria Di Bartolo, Luca De Sabato, Department of Food Safety, Nutrition, and Veterinary Public Health, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy.

Italian Genomic Laboratory Network

Liborio Stuppia, Federico Anaclerio (Center for Advanced Studies and Technology (CAST), G. d’Annunzio University of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy); Giovanni Savini, Cesare Cammà, Luigi Possenti (Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Abruzzo e del Molise “Giuseppe Caporale”, Teramo, Italy); Domenico Dell’Edera (Medical Genetics Unit, “Madonna delle Grazie” Hospital, Matera, Italy); Antonio Picerno, Teresa Lopizzo (Clinical Pathology and Microbiology Unit, AOR San Carlo, Potenza, Italy); Maria Teresa Fiorillo, Rosaria Oteri (Unit of Microbiology and Virology, North Health Center ASP 5, Reggio Calabria, Italy); Giuseppe Viglietto (CIS (Interdepartmental Center for Services and Research), Genomics and Molecular Pathology, “Magna Graecia” University, Catanzaro, Italy); Pasquale Minchella (Department of Microbiology and Virology, Pugliese Ciaccio Hospital, Catanzaro, Italy); Francesca Greco, (Microbiology and Virology Unit, “Annunziata” Hospital of Cosenza, Cosenza, Italy); Antonio Limone, Giovanna Fusco (Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale del Mezzogiorno, Portici, Naples, Italy); Claudia Tiberio, Luigi Atripaldi, Mariagrazia Coppola (UOC Microbiologia e Virologia, P.O. Cotugno A.O. dei Colli, Naples, Italy); Davide Cacchiarelli, Antonio Grimaldi (Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine (TIGEM), Pozzuoli, Napoli, Italy); Stefano Pongolini, Erika Scaltriti (Risk Analysis and Genomic Epidemiology Unit, Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Lombardia e dell’Emilia-Romagna (IZSLER) “Bruno Ubertini”, Parma, Italy); Vittorio Sambri, Giorgio Dirani, Silvia Zannoli (Unit of Microbiology, The Greater Romagna Area Hub Laboratory, Cesena, Italy); Tiziana Lazzarotto, Giada Rossini (Microbiology Unit, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna, Italy); Federica Baldan, Sabrina Lombino (Department of Laboratory Medicine, Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Friuli Centrale Udine, Italy); Pierlanfranco D’Agaro, Ludovica Segat (Hygiene and Preventive Medicine Clinical Operative Unit, Trieste University Hospital—ASUGI, Trieste, Italy); Fabio Barbone, Raffaella Koncan (Department of Medicine, Surgery and Health Sciences, University of Trieste, Italy); Antonio Battisti, Patricia Alba (Department of General Diagnostics, Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale del Lazio e della Toscana (IZSLT), Rome, Italy); Maria Teresa Scicluna (Department of Virology, Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale del Lazio e della Toscana M. Aleandri); Silvia Angeletti, Elisabetta Riva (Unità di ricerca Laboratorio, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio- Medico, Roma, Italy); Fulvia Pimpinelli (UOSD Microbiology and Virology, IRCCS San Gallicano Dermatological Institute, IFO, Rome, Italy); Maurizio Fanciulli (SAFU Laboratory, IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, IFO, Rome, Italy); Alice Massacci (Biostatistics, Bioinformatics and Clinical Trial Center, IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, IFO, Rome, Italy); Maurizio Sanguinetti (Dipartimento di Scienze di Laboratorio e Infettivologiche, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy); Fabrizio Maggi, Martina Rueca, Cesare Ernesto Maria Gruber (Laboratory of Virology, National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Lazzaro Spallanzani” (IRCCS), Rome, Italy); Ombretta Turriziani (Department of Molecular Medicine, Sapienza University of Rome, Sapienza University Hospital “Policlinico Umberto I”, Rome, Italy); Carlo Federico Perno (Microbiology and Diagnostic Immunology, Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Rome, Italy); Francesca Ceccherini-Silberstein, Maria Concetta Bellocchi (Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy); Bianca Bruzzone, Giancarlo Icardi, Andrea Orsi (Hygiene Unit, San Martino Policlinico Hospital-IRCCS for Oncology and Neurosciences Genoa, Italy); Rea Valaperta (ASST Bergamo Est, Italy); Maria Oggionni (ASST Bergamo Ovest, Bergamo, Italy); Sophie Testa, Fabio Sagradi (ASST Cremona, Cremona, Italy); Arnaldo Caruso (Department of Molecular and Translational Medicine University of Brescia Medical School, Brescia, Italy); Serena Messali (Laboratory of Microbiology and Virology, ASST degli Spedali Civili Brescia, Brescia, Italy); Diana Fanti, Alice Nava (S.C. Clinical Microbiology, ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda Milan, Italy); Sergio Malandrin, Annalisa Cavallero (Microbiology and Virology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS San Gerardo dei Tintori, Monza, Italy); Claudio Francesco Farina, Marco Arosio (Microbiology and Virology Laboratory, ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Italy); Ferruccio Ceriotti, Sara Colonia Uceda Renteria, Stefania Paganini (UOS Laboratorio di Virologia, UOC Laboratorio Analisi Fondazione IRCCS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico); Anna Maria Di Blasio, Erminio Torresani (IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan, Italy); Maria Beatrice Boniotti, Cristina Bertasio (Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Lombardia ed Emilia Romagna, Brescia, Italy); Nicola Clementi (Laboratory of Microbiology and Virology, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, Italy, Laboratory of Microbiology and Virology, IRCCS Ospedale San Raffaele, Milan, Italy); Michela Sampaolo (Laboratory of Microbiology and Virology, IRCCS San Raffaele Hospital, Milan, Italy); Federica Novazzi, Nicasio Mancini (Laboratory of Microbiology, ASST Sette Laghi, Varese, Italy); Maria Rita Gismondo, Valeria Micheli (Laboratory of Clinical Microbiology, Virology and Bioemergencies, ASST Fatebenefratelli Sacco, Luigi Sacco Hospital, Milan, Italy); Fausto Baldanti (Microbiology and Virology Department, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy, Dpt. of Clinical, Surgical, Diagnostics and Pediatric Sciences, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy); Federica AM Giardina (Dpt. of Clinical, Surgical, Diagnostics and Pediatric Sciences, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy); Antonio Piralla, Federica Zavaglio, Francesca Rovida (Microbiology and Virology Department, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy); Elena Pariani, Cristina Galli, Laura Pellegrinelli (Department of Biomedical Sciences for Health, University of Milan, Milan, Italy); Stefano Menzo (Department of Biomedical Sciences and Public Health, Virology Unit, Polytechnic University of Marche, Ancona, Italy); Massimiliano Scutellà, Valentina Felice (UOSVD Microbiologia e Diagnostica Molecolare Avanzata ASREM P.O. Cardarelli Campobasso (CB), Italy); Elisabetta Pagani, Irene Bianconi, Angela Maria Di Pierro (Laboratory of Microbiology and Virology, Provincial Hospital of Bolzano, SABES-ASDAA; Lehrkrankenhaus der Paracelsus Medizinischen Privatuniversität – Bolzano, Italy); Lucia Collini, Giovanni Lorenzin (Laboratory of Microbiology and Virology, Country Health Service APSS, S. Chiara Hospital, Trento, Italy); Valeria Ghisetti (Laboratory of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, Amedeo di Savoia Hospital, Turin, Italy); Sara Gilardi, Alice Bartolini, Daniela Cantarella (Candiolo Cancer Institute FPO-IRCCS, Candiolo, Turin, Italy); Simone Peletto, Giuseppe Ru, Pier Luigi Acutis, Elena Bozzetta (Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale del Piemonte, Liguria e Valle d’Aosta, Turin, Italy); Maria Chironna, Daniela Loconsole (Hygiene Unit, Interdisciplinary Department of Medicine—DIM, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Bari, Italy); Antonio Parisi (Genetic and Molecular Epidemiology Laboratory, Experimental Zooprophylactic Institute of Apulia and Basilicata, Foggia, Italy); Fabio Arena, Rossella De Nittis, Giuseppina Iannelli (Microbiology and Virology, “Policlinico Riuniti”, University Hospital, Foggia, Italy); Florigio Romano Lista (Scientific Department, Army Medical Center, Rome, Italy); Ferdinando Coghe (Laboratorio Generale (HUB) Analisi Chimico Cliniche e Microbiologia, PO “Duilio Casula”, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria di Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy); Sergio Uzzau, Salvatore Rubino, Flavia Angioj, Gabriele Ibba, Caterina Serra (Department of Biomedical Sciences, S.C. Microbiology and Virology, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria di Sassari, Sassari, Italy); Giovanna Piras, Giuseppe Mameli, Rosanna Asproni (Laboratorio Specialistico, UOC Ematologia e CTMO, P.O. “San Francesco,” ASL Nuoro, Nuoro, Italy); Francesca Di Gaudio (Department of Health Promotion, Mother and Child Care, Internal Medicine and medical Specialties “G. D’Alessandro”, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy); Stefano Vullo, Stefano Reale (Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Sicilia, Palermo, Italy); Teresa Pollicino (Division of Advanced Diagnostic Laboratories, University Hospital “G. Martino” Messina, Italy); Francesco Vitale, Fabio Tramuto (Clinical Epidemiology Unit and Regional Reference Laboratory, University Hospital “P. Giaccone”, Palermo, Italy, Department of Health Promotion, Mother and Child Care, Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties “G. D’Alessandro”, University of Palermo, Italy); Stefania Stefani (Clinical Virology Laboratory, “G. Rodolico—S. Marco” Hospital, Catania, Italy, Department of Biomedical and Biotechnological Sciences, University of Catania, Catania, Italy); Guido Scalia (A.O.U. Policlinico “G. Rodolico- S. Marco”, U.O.C. Laboratory Analysis, Virology Section, and Department of Biomedical and Biotechnological Sciences, University of Catania, Catania, Italy); Concetta Ilenia Palermo (A.O.U. Policlinico “G. Rodolico- S. Marco”, U.O.C. Laboratory Analysis, Virology Section, Catania, Italy); Giuseppe Mancuso (UOC Microbiology, University Hospital “G. Martino”, Messina, Italy); Vincenzo Bramanti, Carmelo Fidone, Giuseppe Barrano (U.O.C. Laboratory Analysis, ASP Ragusa, Ragusa, Italy); Mauro Pistello (Department of Translational Research, University of Pisa; Virology Unit, Pisa University Hospital, Pisa, Italy); Gian Maria Rossolini (Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Florence, Italy, Microbiology and Virology Unit, Florence Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy); Francesca Malentacchi (Microbiology and Virology Unit, Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy); Maria Grazia Cusi (Virology Unit, Department of Medical Biotechnologies, University of Siena, Siena, Italy); Antonella Mencacci, Barbara Camilloni (Microbiology and Clinical Microbiology, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Perugia, Santa Maria della Misericordia Hospital, Perugia, Italy); Calogero Terregino, Alice Fusaro, Isabella Monne, Edoardo Giussani (Division of Comparative Biomedical Sciences, Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Venezie, Legnaro, Padova, Italy); Davide Gibellini, Emil Tonon, Riccardo Cecchetto (Department of Diagnostic and Public Health, Verona University, Verona, Italy); Laura Squarzon, Mosè Favarato (Molecular Diagnostics and Genetics, AULSS 3 Serenissima, Venice, Italy); Valeria Biscaro, Elisa Vian, Silvia Ragolia (UOC Microbiology Treviso Hospital, Department of specialist and laboratory medicine, AULSS 2 Marca Trevigiana, Italy); Michela Pascarella, Fabio Buffoli, Isabella Cerbaro (U.O.C. Microbiology, U. O. S. Molecular Biology applied to Microbiology and Virology, San Bortolo Hospital, AULSS n.8 Berica, Vicenza, Italy).

Authors’contributions

EG performed the genomic analysis and wrote the first version of the manuscript together with IS. IS performed and supervised the neutralization assay, with the collaboration of GF and PL, GF contributed to supervise the neutralization assay. LA, ADM, ALP, support the genomic analysis and evaluation. SF performed the virus cultivation. ATP supported the discussion on the manuscript. PS conceived the study and coordinated the overall activities, revised the manuscript. The Italian Genomic Laboratory Network produced the SARS-CoV-2 genomes used in the study. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by ISS, as per art. 34bis, Law. 106—23 July 2021, and by the European Union, within the “Enhancing Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), national infrastructures and capacities for COVID-19 and surveillance of other respiratory viruses in Italy” (SeCOV +) project (Project n. 101102366).

Data availability

The dataset of sequences analysed during the current study are available in the GISAID repository (https://gisaid.org). The ID numbers of each sequences is listed in supplementary Table 4.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all the enrolled participants to collect sera for neutralization assay. The study was approved by the Italian National Ethics Committee for clinical trials of public research bodies and other national public institutions (CEN) at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS), (AOO-ISS 10/10/2023 0045874). Molecular investigation was conducted as part of the Italian SARS-CoV-2 virus variants monitoring.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Emanuela Giombini and Ilaria Schiavoni contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Paola Stefanelli, Email: paola.stefanelli@iss.it.

the Italian Genomic Laboratory Network:

Liborio Stuppia, Federico Anaclerio, Giovanni Savini, Cesare Cammà, Luigi Possenti, Domenico Dell’Edera, Antonio Picerno, Teresa Lopizzo, Maria Teresa Fiorillo, Rosaria Oteri, Giuseppe Viglietto, Pasquale Minchella, Francesca Greco, Antonio Limone, Giovanna Fusco, Claudia Tiberio, Luigi Atripaldi, Mariagrazia Coppola, Davide Cacchiarelli, Antonio Grimaldi, Stefano Pongolini, Erika Scaltriti, Vittorio Sambri, Giorgio Dirani, Silvia Zannoli, Tiziana Lazzarotto, Giada Rossini, Federica Baldan, Sabrina Lombino, Pierlanfranco D’Agaro, Ludovica Segat, Fabio Barbone, Raffaella Koncan, Antonio Battisti, Patricia Alba, Maria Teresa Scicluna, Silvia Angeletti, Elisabetta Riva, Fulvia Pimpinelli, Maurizio Fanciulli, Alice Massacci, Maurizio Sanguinetti, Fabrizio Maggi, Martina Rueca, Cesare Ernesto Maria Gruber, Ombretta Turriziani, Carlo Federico Perno, Francesca Ceccherini-Silberstein, Maria Concetta Bellocchi, Bianca Bruzzone, Giancarlo Icardi, Andrea Orsi, Rea Valaperta, Maria Oggionni, Sophie Testa, Fabio Sagradi, Arnaldo Caruso, Serena Messali, Diana Fanti, Alice Nava, Sergio Malandrin, Annalisa Cavallero, Claudio Francesco Farina, Marco Arosio, Ferruccio Ceriotti, Sara Colonia Uceda Renteria, Stefania Paganini, Anna Maria Di Blasio, Erminio Torresani, Maria Beatrice Boniotti, Cristina Bertasio, Nicola Clementi, Michela Sampaolo, Federica Novazzi, Nicasio Mancini, Maria Rita Gismondo, Valeria Micheli, Fausto Baldanti, Federica AM Giardina, Antonio Piralla, Federica Zavaglio, Francesca Rovida, Elena Pariani, Cristina Galli, Laura Pellegrinelli, Stefano Menzo, Massimiliano Scutellà, Valentina Felice, Elisabetta Pagani, Irene Bianconi, Angela Maria Di Pierro, Lucia Collini, Giovanni Lorenzin, Valeria Ghisetti, Sara Gilardi, Alice Bartolini, Daniela Cantarella, Simone Peletto, Giuseppe Ru, Pier Luigi Acutis, Elena Bozzetta, Maria Chironna, Daniela Loconsole, Antonio Parisi, Fabio Arena, Rossella De Nittis, Giuseppina Iannelli, Florigio Romano Lista, Ferdinando Coghe, Sergio Uzzau, Salvatore Rubino, Flavia Angioj, Gabriele Ibba, Caterina Serra, Giovanna Piras, Giuseppe Mameli, Rosanna Asproni, Francesca Di Gaudio, Stefano Vullo, Stefano Reale, Teresa Pollicino, Francesco Vitale, Fabio Tramuto, Stefania Stefani, Guido Scalia, Concetta Ilenia Palermo, Giuseppe Mancuso, Vincenzo Bramanti, Carmelo Fidone, Giuseppe Barrano, Mauro Pistello, Gian Maria Rossolini, Francesca Malentacchi, Maria Grazia Cusi, Antonella Mencacci, Barbara Camilloni, Calogero Terregino, Alice Fusaro, Isabella Monne, Edoardo Giussani, Davide Gibellini, Emil Tonon, Riccardo Cecchetto, Laura Squarzon, Mosè Favarato, Valeria Biscaro, Elisa Vian, Silvia Ragolia, Michela Pascarella, Fabio Buffoli, and Isabella Cerbaro

References

- 1.Cai Y, Zhang J, Xiao T, Lavine CL, Rawson S, Peng H, et al. Structural basis for enhanced infectivity and immune evasion of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science. 2021;373:642–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rochman ND, Wolf YI, Faure G, Mutz P, Zhang F, Koonin EV. Ongoing global and regional adaptive evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118: e2104241118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Washington NL, Gangavarapu K, Zeller M, Bolze A, Cirulli ET, Schiabor Barrett KM, et al. Emergence and rapid transmission of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 in the United States. Cell. 2021;184:2587–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulrichs T, Rolland M, Wu J, Nunes MC, El Guerche-Séblain C, Chit A. Changing epidemiology of COVID-19: potential future impact on vaccines and vaccination strategies. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2024;23:510–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaku Y, Okumura K, Padilla-Blanco M, Kosugi Y, Uriu K, Hinay AA, et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 JN.1 variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24:e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao Z, Zhang L, Duan Y, Tang X, Lu J. Molecular insights into the adaptive evolution of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. J Infect. 2024;88: 106121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeworowski LM, Mühlemann B, Walper F, Schmidt ML, Jansen J, Krumbholz A, et al. Humoral immune escape by current SARS-CoV-2 variants BA.2.86 and J.N1, December 2023. Euro surveill. 2024;29:2300740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katoh K, Standley DM. A simple method to control over-alignment in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1933–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ranwez V, Harispe S, Delsuc F, Douzery EJP. MACSE: Multiple Alignment of Coding SEquences Accounting for Frameshifts and Stop Codons. PLoS ONE. 2011;6: e22594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:268–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38:3022–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirabara SM, Serdan TDA, Gorjao R, Masi LN, Pithon-Curi TC, Covas DT et al. SARS-COV-2 variants: differences and potential of immune evasion. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;11. 10.3389/fcimb.2021.781429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Farkas C, Fuentes-Villalobos F, Garrido JL, Haigh J, Barría MI. Insights on early mutational events in SARS-CoV-2 virus reveal founder effects across geographical regions. PeerJ. 2020;8: e9255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li M, Du J, Liu W, Li Z, Lv F, Hu C, et al. Comparative susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV across mammals. ISME J. 2023;17:549–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruhl L, Kühne JF, Beushausen K, Keil J, Christoph S, Sauer J et al. Third SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and breakthrough infections enhance humoral and cellular immunity against variants of concern. Front Immunol. 2023;14. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1120010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Pérez-Alós L, Hansen CB, Almagro Armenteros JJ, Madsen JR, Heftdal LD, Hasselbalch RB, et al. Previous immunity shapes immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 booster vaccination and Omicron breakthrough infection risk. Nat Commun. 2023;14:5624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samanta S, Banerjee J, Das A, Das S, Ahmed R, Das S, et al. Enhancing immunological memory: unveiling booster doses to bolster vaccine efficacy against evolving SARS-CoV-2 mutant variants. Curr Microbiol. 2024;81:91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fedele G, Trentini F, Schiavoni I, Abrignani S, Antonelli G, Baldo V, et al. Evaluation of humoral and cellular response to four vaccines against COVID-19 in different age groups: A longitudinal study. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1021396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fedele G, Schiavoni I, Trentini F, Leone P, Olivetta E, Fallucca A, et al. A 12-month follow-up of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 primary vaccination: evidence from a real-world study. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1272119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widge AT, Rouphael NG, Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Roberts PC, Makhene M, et al. Durability of responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:80–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner JS, O’Halloran JA, Kalaidina E, Kim W, Schmitz AJ, Zhou JQ, et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines induce persistent human germinal centre responses. Nature. 2021;596:109–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo L, Zhang Q, Gu X, Ren L, Huang T, Li Y, et al. Durability and cross-reactive immune memory to SARS-CoV-2 in individuals 2 years after recovery from COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Microbe. 2024;5:e24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1. Supplementary Table 1: JN.1* mutations identified among the genomes object of this study.

Supplementary Material 2. Supplementary Table 2: XBB.1.5 mutations identified among the genomes object of this study.

Supplementary Material 3. Supplementary Table 3: Comparison of XBB.1.5 and JN.1* signature positions.

Supplementary Material 4. Supplementary Table 4: ID of sequences analysed downloaded from GISAID repository and analysed in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset of sequences analysed during the current study are available in the GISAID repository (https://gisaid.org). The ID numbers of each sequences is listed in supplementary Table 4.