Abstract

Purpose

Gastric cancer is an inflammation-driven disease often associated with a bad prognosis. Upstream stimulatory factors USF1 and USF2 are pleiotropic transcription factors, with tumor suppressor function. Low expression of USF1 is associated with low survival in gastric cancer patients. USF1 genetic polymorphism -202G > A has been associated with cancer susceptibility. Our aim was to investigate USF1 gene polymorphism and serum level with the risk of gastric cancer.

Methods

USF1-202 G/A polymorphism was analyzed by sanger sequencing, with the measure of USF1/USF2 serum levels by ELISA in H. pylori-positive patients with chronic gastritis, gastric precancerous lesions, gastric cancer and in healthy controls.

Results

Our results show that the presence of the USF1-202 A allele increased the risk of gastric cancer compared to G (OR = 2; 95% CI 1.07–3.9; P = 0.02). Genotypically and under the dominant mutation model, the combined USF1- GA/AA -202 genotypes corresponded to higher risk of gastric cancer (OR = 3.5; 95% CI 1.4–8.2; p-value = 0.005) than the GG genotype. Moreover, the G/A transition at USF1-202 was associated with lower USF1 serum level, and mostly observed in gastric cancer patients where the average serological level of USF1 were 2.3 and twofold lower for the AA and GA genotypes, respectively, compared to GG.

Conclusion

USF1-202 G/A polymorphism constitutes a gastric cancer genetic risk factor. Together with USF1/USF2 serum level, they can be proposed as promising biomarkers for gastric cancer detection/prevention.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00432-025-06158-1.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Genetic polymorphism, Genetic risk factor, Biomarkers, Serum

Introduction

Gastric cancer remains one of the most aggressive neoplasm worldwide with a high mortality rate. It is mainly associated with a bad prognosis because of its diagnosis often performed at advanced stages with limited therapeutic options (Bray et al. 2018). Presently, gastric cancer can only be detected by gastric endoscopy which is an invasive and costly method, but which remain the gold-standard for gastric tumours diagnosis. Therefore, the identification of specific biomarkers easily measurable in blood is crucially needed. It could allow an early detection of gastric cancer and largely improve patients survival and their quality of life. An histologic classification of gastric cancer has been determined, defining mainly the intestinal type and the diffuse type (Lauren 1965), and has been recently completed by a molecular classification that distinguishes gastric cancer according to genomic stability/instability and p53 status (Cristescu et al. 2015; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network 2014; Setia et al. 2016). Intestinal-type gastric carcinoma develops via several sequential lesions triggered mainly by Helicobacter pylori infection-driven inflammation, which leads to chronic gastritis, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and gastric adenocarcinoma (Koulis et al. 2019). In addition to H. pylori, recognized as the major risk factor, the development of gastric cancer results from the complex interplay of factors from multiple origin (Seeneevassen et al. 2021). A host genetic polymorphism mainly including genes coding for mediators of inflammation and immune response, components of DNA repair systems, have been associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer (Clyne and Rowland 2019).

The upstream stimulating factors USF1 and USF2 are pleiotropic transcriptional regulators of the expression of genes related to a wide variety of cellular functions, among which the immune response, cell proliferation, DNA repair systems (Corre and Galibert 2005). USF1 and USF2 regulate the expression of genes coding for component of the immune response such as the k2-Ig light chain, IgM J chain, Ig receptors, C4 complement and inflammatory mediators as TGF-β1, IL-3, and IL10 (Corre and Galibert 2005, 2006; Zhang et al. 2007). The USFs factors also function as tumor suppressors by activating the transcription of certain tumor suppressor genes such as TP53, BRCA2, and APC (Corre and Galibert 2006; Bouafia et al. 2014), by inhibiting the expression of the gene coding for the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT), the major component of the telomerase and the oncogenic activity of c-Myc and Ras (Chang et al. 2005; Luo and Sawadogo 1996). USFs also control the cell cycle by slowing the G2/M transition (Jung et al. 2007). Concerning USF1, it has an essential role in the maintenance of genome stability. Under genotoxic stress conditions, USF1 interacts with p53 and inhibits its proteasomal degradation (Corre and Galibert 2006; Bouafia et al. 2014). Moreover, in response to ultra-violet stress, USF1 promotes DNA photolesions repair by activating the transcription of genes coding for components of the nucleotide excision repair (NER) system (Baron et al. 2012). Recently, we demonstrated that USF1 is a new modulator of gastric carcinogenesis, playing a central role in the host DNA damage and repair response to H. pylori infection (Costa et al. 2020). Its low expression is associated with a worse prognosis in gastric cancer patients, leading to propose USF1 as a biomarker candidate to identify sub-groups of such patients (Costa et al. 2020). Importantly, its absence in Usf1−/− mice accelerates H. pylori-induced gastric lesions and exacerbates their severity, compared to infected Usf1+/+ mice (Costa et al. 2020).

According to their pleiotropic properties, the genetic polymorphisms associated to USF factors coding genes may be correlated with immune disorders and cancer diseases (Goueli and Janknecht 2003; Pawar et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2018). The USF1 gene is located on chromosome 1q22–q23, consisting of 11 exons and 10 introns. Its promoter region is TATA box-less, however, it contains an initiator element "Inr" (Corre and Galibert 2005; Verhoeven 2011). The USF2 gene is located on chromosome 19q13 and consists of 10 exons and 9 introns. The USF2 promoter is TATA and CCAAT boxes-less, but contains an initiator element ‘Inr’. Unlike USF1, the USF2 gene promoter is characterized by two E-box motifs located at positions −332 and −186, potentially allowing its regulation by itself and/or USF1 factor (Corre and Galibert 2005). A previous case–control study reported a USF1 genetic polymorphism involving −202G > A, rs2516839, (mutant A alleles vs wild G alleles) and −844C > T, rs3737787 (mutant T alleles vs wild C alleles) associated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) susceptibility (Zhou et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2015). Also in the case of the papillary thyroid cancer, an association between single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of USF1 and high-risk susceptibility involving rs2516838 (mutant G alleles vs wild C alleles), rs3737787 and rs2516839 has been reported (Yuan et al. 2016). To our knowledge, no study has been done to assess the association of USF1 gene polymorphisms and USF1/USF2 serum levels with the risk of gastric cancer. We thus developed a case/control study to evaluate the association between USF1 promoter gene polymorphism at the position USF1-202 G/A and the risk of precancerous lesions and gastric cancer development. In parallel, in order to investigate USF1 and USF2 as potent gastric cancer biomarker candidate, their serum level was also investigated in the same cohort of patients at various stages of gastric carcinogenesis process, also assessing the relationship with the USF1-202 G/A polymorphism.

Materials and methods

Clinical and pathological characteristics of the study population

Two hundred and eighteen Moroccan subjects were included in this study. The studied cohort was categorized as follows:

155 patients with various gastric lesions related to H. pylori infection: including 65 with chronic gastritis, 50 with precancerous lesions (30 with atrophic gastritis, 20 with intestinal metaplasia), and 40 with Intestinal-type gastric cancer recruited at the Gastroenterology and Oncology Departments at the IBN ROCH University Hospital Center in Casablanca, Morocco. Patients having received previous treatment for H. pylori eradication, proton pump inhibitors, anti-inflammatory medicines, chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment, and patients with cancers other than distal gastric adenocarcinoma were excluded from the study.

63 Healthy asymptomatic blood donors served as controls, recruited from the Regional Transfusion Center of Casablanca, with no history of gastrointestinal illnesses or regular use of any gastrointestinal and anti-inflammatory medicines.

Clinical information about the demographic characteristics of the participants were collected using a defined questionnaire. The characteristics of the studied population are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the studied population

| Demographic data | Controls N (%) |

Chronic gastritis N (%) |

Precancerous lesions N (%) |

Gastric cancer N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| [< 40] | 28 (44.4) | 30 (46.1) | 8 (16) | 5 (12.5) |

| [40–50] | 20 (31.8) | 12 (18.5) | 14 (28) | 9 (22.5) |

| [50–60] | 15 (23.8) | 16 (24.6) | 13 (26) | 5 (12.5) |

| [60 >] | 0 (0) | 7 (10.8) | 15 (30) | 21 (52.5) |

| Min–max [mean] | 25–57 [43.2] | 26–85 [45.1] | 23–80 [53.4] | 23–75 [55.8] |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 34 (54) | 25 (40) | 25 (50) | 23 (55) |

| Female | 29 (46) | 40 (60) | 25 (50) | 17 (45) |

| Ratio M/F | 1.17 | 0.62 | 1 | 1.35 |

| Living area | ||||

| Urban | 49 (77.8) | 48 (73.8) | 29 (58) | 15 (37.5) |

| Rural | 14 (22.2) | 17 (26.2) | 21 (42) | 25 (62.5) |

All participants were informed about the study and agreed to their participation. Informed consent has been obtained from all patients.

Genotyping of USF1 at position −202 G/A

Genotyping experiments were performed as previously reported (Bounder et al. 2020). Genomic DNA was extracted from blood collected in EDTA-tubes, using the commercially available kit (PureLink™ Genomic DNA Mini Kit) and stored at − 20 °C until use. The USF1 genetic polymorphism at position −202 of its promoter region (from − 446 to − 61, size of 386 bp) was analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) followed by DNA sequencing. The reaction was carried out in 20 μL, including: 200 ng of genomic DNA, 0.2 µM of primers (Yuan et al. 2016), 1 mM dNTPs, 3 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 unit of Taq polymerase (MyTaq™ Polymerase, Bioline). PCR thermocycling conditions were as follow: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 58 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR products were purified using exonuclease (Thermo Scientific) and alkaline phosphatase (Promega) and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min and at 80 °C for 15 min. DNA sequencing conditions were carried out using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems), with an Applied Biosystems 377 DNA sequencer using the BIOEDITE software package.

Quantification of USF1 and USF2 serum levels

Blood samples were collected in a serum tube from patients before anesthesia and gastroscopy examination. The serum was separated within 1 h of blood collection after spinning for 15 min at 1500 g. Serum samples were stored at − 80 °C in aliquots of 500 µL and thawed just before testing. The USF1 and USF2 serum levels were determined by using Human USF1 (MyBioSource: MBS9342772) and Human USF2 (MyBioSource: MBS9388787) quantitative immuno-enzymatic sandwich ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total USF1 and USF2 concentrations in samples were expressed as pg/ml.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed with R software. The descriptive data are presented in terms of frequencies. The comparisons of genotypes and allele frequencies between cases and controls were tested by the chi-square or the Fisher’s test. Odds Ratios (OR), as well as their 95% confidence intervals (CI), were computed to estimate the risk of chronic gastritis, precancerous lesions, and gastric cancer in the subjects with USF1 −202 G/A variants. The normal distribution of serum levels was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test and then a quantitative data comparison between two groups was performed by the Wilcoxon test. The quantitative data comparison between more than two groups was performed by the Kruskal Wallis test. The correlation between the USF1 and USF2 serum levels was determined by the Kendall correlation and the linear regression tests. The differences were considered significant at a p-value < 0.05.

Results

Genotyping of USF1 at position −202 G/A

The general characteristics of the patients included in the studied cohort are reported in Table 1. As reported in the Supplementary Fig. S1, the groups of patients with precancerous lesions or gastric cancer lesions are significantly older compared to the healthy controls (p-value = 0.0008 and p-value < 0.0001, respectively) and patients with chronic gastritis (p-value = 0.0089 and p-value = 0.0005, respectively). As many men as women have been included in the healthy controls and precancerous lesions groups while 1.6 more women and 1.3 more men are found among chronic gastritis and gastric cancer patients, respectively.

The distribution of USF1−202 G/A alleles and genotypes and the statistical analysis are reported in Table 2. The frequency of the USF1-202 A allele is 19% in healthy control and increased with the severity of gastric lesions, corresponding to 23%, 28%, and 32.5% in patients with chronic gastritis, precancerous lesions, and gastric cancer, respectively. A significant allelic variation was observed between the gastric cancer group and healthy controls (p-value = 0.02). The A allele was associated with an elevated risk of gastric cancer compared to the G allele (OR = 2; 95% CI 1.07–3.9; P = 0.02).

Table 2.

Allelic and genotypic distribution of the USF1 −202 G/A polymorphism in patients with gastric lesions and controls

| HC N (%) |

CG N (%) |

PL N (%) |

GC N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USF1-202 G/A alleles | ||||

| G | 102 (81) | 100 (77) | 72 (72) | 54 (67.5) |

| A | 24 (19) | 30 (23) | 28 (28) | 26 (32.5) |

| P-value* | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.02 | |

| OR; [95% CI]; P-value** | 1.2; [0.7–2.3]; 0,44 | 1.6; [0.88–1]; 0,36 | 2; [1.07–3.9]; 0.03 | |

| USF1-202 G/A genotypes | ||||

| GG | 49 (77.8) | 46 (70.8) | 31 (62) | 20 (50) |

| GA | 4 (6.3) | 8 (12.3) | 10 (20) | 14 (35) |

| AA | 10 (15.9) | 11 (16.9) | 9 (18) | 6 (15) |

| P-value* | 0.5 | 0.07 | 0.0007 | |

| OR; [95% CI]; P-value** | ||||

| Dominant (GG vs AA + GA) | 1.4; [0.65–3.2]; 0.42 | 2.1; [0.94–4.8]; 0.09 | 3.5; [1.4–8.2]; 0.005 | |

| Recessive (GG + GA vs AA) | 1.1; [0.42–2.7]; 1 | 1.1; [0.43–3.1]; 0.8 | 0.9; [0.3–2.8]; 1 | |

| Codominant (GG vs GA) | 2.1; [0.60–7.56]; 0.36 | 3.9; [1.14–13.7]; 0.04 | 8.6; [2.51–29.24]; 0.0003 | |

| Codominant (GA vs AA) | 0.55; [0.13–2.40];0.49 | 0.36; [0.08–1.56]; 0,28 | 0.17; [0.04–0.77];0.03 | |

HC healthy controls; CG chronic gastritis; PL precancerous lesions; GC gastric cancer

*P-values were calculated using the Chisq test/Fisher test

**Two by 2 command

The GA genotype was more frequent among patients with gastric cancer (35%) and precancerous lesions (20%), compared to patients with chronic gastritis (12.3%) and healthy controls (6.3%). While the GG genotype was more frequently found in healthy controls (77.8%) and patients with chronic gastritis (70.8%) compared to those with precancerous lesions (62%) and gastric cancer (50%). The statistical analysis demonstrated a significant genotypic alteration between patients suffering from gastric cancer and healthy controls (p-value = 0.0007). In the case of dominant mutation, the USF1-202 GA/AA genotypes were associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer (OR = 3.5; 95% CI 1.4–8.2; p-value = 0.005) compared to the GG genotype. In the case of the codominance, an elevated risk of gastric cancer was observed with GA genotypes compared to GG (OR = 8.6; 95% CI 2.5–29.2; p-value = 0.0003). In the case of recessive mutation, no significant risk was detected (Table 2).

In patients with precancerous lesions, the A allele tend to be found more frequently compared to the healthy controls group, but the difference was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.07). Regarding genotypic distribution, under a codominant model, the GA genotype was associated with a higher risk of precancerous lesions compared to GG (OR = 3.9; 95% CI 1.1–13.7; p = 0.04). However, no significant risk was identified under dominant or recessive models (Table 2).

The results show that the USF1-202 G/A polymorphism may be associated may be associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer and the development of precancerous lesions.

Quantification of USF1 and USF2 serum levels

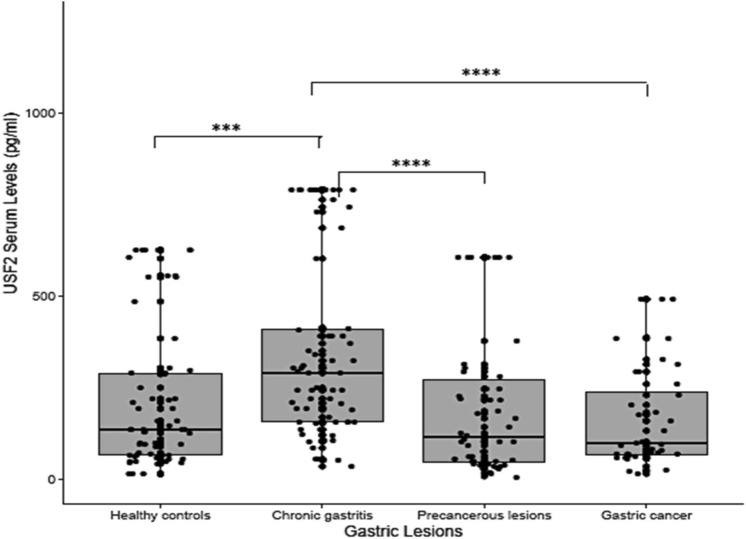

USF1 and USF2 act as homo- or heterodimers to regulate the expression of genes at E-box consensus sequences in their promoter region. As indicated above, the USF2 gene promoter is characterized by two E-box motifs located at positions −332 and −186, potentially allowing its regulation by itself and or USF1 factor (Corre and Galibert 2005). We then analysed in parallel to USF1, the distribution of USF2 levels in the serum of patients and healthy controls as shown in Figs. 1 and 2 respectively.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of serum levels of USF1 in controls and patients with gastric lesions

Fig. 2.

Distribution of serum levels of USF2 in controls and patients with gastric lesions

Concerning USF1, the mean serum levels in the healthy controls group was 239.5 pg/ml, in comparison to 448.2 pg/ml, 320 pg/ml and 212.7 pg/ml in patients with chronic gastritis, precancerous lesions, and gastric cancer, respectively (Table 3). Similar results were observed regarding USF2, with mean serum levels of 217.7 pg/ml in healthy controls, in comparison to 348.7 pg/ml, 200.8 pg/ml and 165.3 pg/ml in patients with chronic gastritis, precancerous lesions and gastric cancer, respectively (Table 4). Higher serum levels of USF1 and USF2 were recorded in patients with chronic gastritis compared to the other groups (p-value < 0.05), while the lower levels were recorded in patients with gastric cancer, with a twofold decrease compared to chronic gastritis patients (p-value = 0.0003 (USF1); p-value = 0.00003 (USF2)). More significant differences were observed on USF2 than USF1 levels, between chronic gastritis and precancerous lesions patients (p-value = 0.00005; p-value = 0.03, respectively) (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

USF1 serum levels at the different steps of the gastric carcinogenesis process

| USF1 (pg/ml) | HC | CG | PL | GC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 14 | 53 | 39 | 24 |

| 25% percentile | 87 | 200 | 94.5 | 90.25 |

| Median | 164 | 331 | 250.5 | 126 |

| 75% percentile | 333 | 588.5 | 413 | 340.8 |

| Maximun | 2212 | 5307 | 2376 | 581 |

| Mean | 239.5 | 448.2 | 320 | 212.7 |

| p-value significance intra-groups* | ||||

| p-value significance inter groups** | ||||

| Case vs healthy controls | 0.0001 | 0.11 | 0.56 | |

| Cases vs chronic gastritis | – | 0.03 | 0.0003 | |

| Cases vs precancerous lesions | – | – | 0.10 | |

HC healthy controls; CG chronic gastritis; PL precancerous lesions; GC gastric cancer

*Kruskal–Wallis test

**Wilcox test

Table 4.

USF2 serum levels at the different steps of the gastric carcinogenesis process

| USF2 (pg/ml) | HC | CG | PL | GC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 15 | 36 | 7 | 14 |

| 25% percentile | 66 | 156 | 46.5 | 68 |

| Median | 135 | 289 | 114.5 | 100.5 |

| 75% percentile | 290 | 412 | 283 | 251.8 |

| Maximun | 1836 | 1860 | 1968 | 760 |

| Mean | 217.7 | 348.7 | 200 | 165.3 |

| p-value significance intra-groups* | ||||

| p-value significance inter groups** | ||||

| Case vs healthy controls | 0.0001 | 0.3 | 0.35 | |

| Cases vs chronic gastritis | – | 0.00005 | 0.00003 | |

| Cases vs precancerous lesions | – | – | 0.9 | |

HC healthy controls; CG chronic gastritis; PL precancerous lesions; GC gastric cancer

*Kruskal–Wallis test

**Wilcox test

USF1 serum levels are measured by ELISA at the different stages of gastric cancer cascade. Data show median values in controls (164 pg/ml) and patients suffering from chronic gastritis (331 pg/ml), precancerous lesions (250 pg/ml) and gastric cancer (126 pg/ml). Higher serum levels of USF1 were recorded in patients with chronic gastritis compared to the controls (p-value = 0.0001), precancerous lesions (p-value = 0.03) and patients with gastric cancer (p-value = 0.0003).

USF2 serum levels are measured by ELISA at the different stages of gastric cancer cascade. Data show median values of USF2 in controls (135 pg/ml) and patients suffering from chronic gastritis (289 pg/ml), precancerous lesions (114.5 pg/ml) and gastric cancer (100.5 pg/ml). Higher serum levels of USF2 were recorded in patients with chronic gastritis compared to the controls (p-value = 0.0001), precancerous lesions (p-value = 0.00005) and patients with gastric cancer (p-value = 0.00003). The results revealed an increase of USF1 and USF2 serum levels in the chronic gastritis group, while a decrease was observed in gastric cancer patients.

Interestingly, a positive relationship was noted between the serum levels of USF1 and USF2 levels (p-value < 2.2e− 16; τ = 0.7) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between USF 1 and USF2 serum levels. Data show the distribution of serum levels of USF2 according to serum levels of USF1, as measured by ELISA at various stages of the gastric cancer cascade

Association between USF1 −202 G/A gene polymorphism and USF1 serum levels

The results showed a noteworthy difference in USF1 levels according to genotypes of the USF1 −202 G/A locus in the cohort (Table 5). The serum levels of USF1 were markedly lower in individuals with the GA and AA genotype compared to those with the GG genotype. The mean levels were 452 pg/ml, 228 pg/ml, and 271 pg/ml in carriers of the GG, GA, and AA genotype, respectively. Statistically, the difference in serum levels was significant between the genotypic groups (p-value = 0.0002). Indeed, the differences in USF1 serum level associated with GA and AA USF1 −202 genotype are significant as compared to GG. However, no differences were significantly observed between GA and AA. In order to investigate if the association between USF1 serum levels and USF −202 genotype can by be modulated by the gastric lesions stages, the analysis was performed for each group of patients. As reported in Fig. 4, the most important impact of these USF1 allelic variations are observed in the group of gastric cancer patients where the average serological level of USF1 were 2.3 and twofold lower for the AA and GA genotypes compared to GG.

Table 5.

Association between USF1 −202 G/A locus genotypes and USF1 serum levels

| USF1 −202 G/A genotypes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USF1 (pg/mL) | GG | GA | AA | |

| Minimum | 14 | 34 | 24 | |

| 25% percentile | 113.5 | 84.25 | 61 | |

| Median | 270 | 130 | 111 | |

| 75% percentile | 501.5 | 338.3 | 337 | |

| Maximum | 5307 | 837 | 1458 | |

| Mean | 452 | 228 | 271 | |

| p-value intra-groups (Kruskal Wallis test) | 0.0002 | |||

| p-value inter-groups (Wilcox test) | ||||

| Case vs GG | 0.01 | 0.004 | ||

| Case vs GA | 0.7 | |||

Fig. 4.

USF1 GA- and AA-genotypes are associated with lower USF1 serum levels, compared to GG genotypes, especially in gastric cancer patients

USF1 serum levels measured by ELISA according to USF1-202 GA-, AA- and GG-genotypes determined as indicated in the Material and methods section, for each group of gastric pathologies and healthy controls. Lower USF1 serum levels are observed for GA- (p = 0.04) and AA- (p = 0.03) genotypes for gastric cancer patients, compared to GG-. Among patients with GA- genotype, USF1 serum level was lower in patients with gastric cancer compared to chronic gastritis (p = 0.0059). Comparing chronic gastritis patients with healthy controls with the GG- genotype, USF1 serum levels was higher in the presence of chronic gastritis lesions case compared to healthy (p = 0.0019).

The results revealed a negative impact of the USF1 −202 G/A variant on serum levels of USF1, and the impact was more evident in the gastric cancer group.

Discussion

Despite therapeutic advances, gastric cancer is most often associated with an unfavorable prognosis, mainly due to its asymptomatic phenotype during its development. In addition to H. pylori infection, host germline genetic variations are among the risk factors for gastric cancer. Genetic variants among which SNPs related to genes coding for DNA repair, DNA methylation, and inflammatory and immune response components may constitute risk factors and accelerate the development of gastric cancer (Tian et al. 2019; Mocellin et al. 2015). Due to their regulatory function on the expression of various genes related to different biological processes including tumorigenesis, variations in genes coding for USFs transcription factor could impact the risk of gastric cancer development. In agreement with this hypothesis, our recent data argue for a tumor suppressive activity of USF1 in the case of gastric carcinogenesis (Costa et al. 2020). USF1 genetic polymorphisms have been described and associated with higher susceptibility to certain cancers, including cervical, liver, and thyroid cancer (Wang et al. 2018; Zhou et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2015; Yuan et al. 2016; Zhang 2015). In our population, we demonstrated that the frequencies of the mutated allele USF1 −202 A and the USF1 −202 GA genotype increased with the severity of gastric lesions. The USF1-202 A allele was shown to be associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer compared to the G allele) OR = 2; 95% CI –3.9; p-value = 0.02). Genotypically, under the dominant model, the USF1-202 GA/AA genotypes were associated to a significantly higher risk of gastric cancer (OR = 3.5; 95% CI 1.4–8.2; p-value = 0.005) compared to the GG genotype. Additionally, in the codominant model, a higher risk of gastric cancer was observed with the GA genotypes compared to the GG genotype (OR = 8.6; 95% CI 2.5–29.2; p-value = 0.0003). Our study indicates that USF1-202 G/A polymorphism is associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. Our results are further supported by other studies in the Chinese population, reporting the association of USF1-202 G/A polymorphism with increased sensitivity to HCC and thyroid cancer (Zhou et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2015). Ye et al. have also showed the impact of this polymorphism on the efficiency of chemotherapy and the prognosis of treatment in ovarian cancer patients (Ye et al. 2018). However, due to the geographic variation of gastric cancer incidence and the multifactorial origins of its development, further studies considering different ethnicity are recommended to further validate our findings and to clarify the functional relationship between USF1 polymorphisms and cancer risk susceptibility.

Alteration in USF1 gene expression may impact gastric cancer severity, as we recently reported (Costa et al. 2020). Indeed, the low expression of USF1 in gastric tumour compared to adjacent tissue is associated with a decrease of gastric cancer patient survival. In the present study, we also measured the levels of USF1 and USF2 in the sera of patients, at the different stages of the gastric cancer cascade. Higher serum levels of USF1 and USF2 were significantly recorded in chronic gastritis patients than in the other cases and healthy subjects. Moreover, lower levels were observed in gastric cancer patients, compared to chronic gastritis patients. The high serum levels of USF1 and USF2 in the chronic gastritis group can be associated with the pleiotropic roles of these factors in the regulation of immune and related-inflammation genes expression (Zhang et al. 2007; Frenkel et al. 1998; O’Keefe et al. 2001; Ren et al. 2016; Weigert et al. 2004; Zhu et al. 2005). In line with this, Song et al. revealed a positive correlation between USF1overexpression and activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway and the level of pro-inflammatory factors in patients with osteoarthritis (Song et al. 2018). The decrease of USF1 and USF2 serum levels with the advancement in gastric carcinogenesis, as in patients with precancerous lesions and gastric cancer, may be associated with an inhibition of USF1/USF2 gene expression, leading to impair their functions as tumor suppressors and to promote the development of precancerous lesions and gastric cancer. Accordingly, during H. pylori infection, Bussière et al. demonstrated that down-regulation of USF1 and USF2 genes expression, results from the hypermethylation of their gene promoter and it is associated with the development of intestinal metaplasia in infected mice (Bussière et al. 2010). As previously mentioned, recently Costa et al. reported a promoting effect of USF1-deficiency on gastric carcinogenesis in H. pylori Usf1−/− infected mice (Costa et al. 2020). Moreover, the low expression level of USF1 is associated with a shorter life expectancy and worse prognosis in gastric cancer patients, thus supporting the tumor-suppressive properties of USF1 (Costa et al. 2020). These results are in line with other studies that have showed the down-regulation of USF1 and USF2 in breast, prostate, lung, and oral cancer, supporting these two pleiotropic transcription factors as tumor suppressors (Chang et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2006; Ismail et al. 1999; Khattar et al. 2005).

USFs factors act as dimers as USF1/USF1, USF1/USF2, or USF2/USF2 (Corre and Galibert 2005, 2006; Verhoeven 2011; Kirschbaum et al. 1992; Sirito et al. 1994). In vivo, the USF1/USF2 heterodimer represents more than 66% of the complexes formed. Their activity is complementary and vital for cellular function, and each of them is important to the cellular function of the other (Sirito et al. 1998). In our study, we noticed a strong positive correlation between USF1 and USF2 serum levels. Genetically, mutations in the promoter of the genes can affect genes expression, either positively or negatively. The rs2516839 (USF1 −202 G/A) genetic variant corresponds to a mutation in the 5’UTR of the USF1 gene that can affect the intiation of transcription as well as the recruitment of transcriptional factors, resulting in abnormal expression of USF1. However, the effect of the USF1 −202 G/A polymorphism on USF1 serum levels has not been well established. In the present study, we showed that the serum levels of USF1 were lower in individuals carrying the GA and AA genotypes compared to those carrying the GG genotype. Our findings support an inhibitory effect of the USF1-202 A allele on the expression of USF1, as also reported in the context of atherosclerotic plaques lesions (Fan et al. 2014). These data lead us to propose that the determination of GA and AA genotypes at USF1 −202 locus associated with low USF1 and USF2 serum levels constitute powerful biomarkers for the detection/prevention of patients at risk of gastric cancer.

In summary, our study revealed that the USF1-202G/A polymorphism appeared to be linked to an increased susceptibility to gastric cancer. Serum levels of USF1 and USF2 were higher in patients with chronic gastritis and decreased with the progression of the severity of gastric lesions. The polymorphism at the USF1-202 G/A position led to a reducing effect on USF1 expression. Besides, a positive correlation between USF1 and USF2 was noted, suggesting a collaborative cellular activity between these two transcription factors. Despite the fact that further studies on larger populations and diverse ethnicities are needed to better understand the impact of USF1-202 G/A polymorphism and USF1/ USF2 serum levels on gastric cancer susceptibility, coupling these two markers constitute a promising diagnostic approach to identify at the earliest patients highly susceptible to gastric cancer development. Importantly, these analyses based on non-invasive methods pave the way to further validation and development of a simple blood-based diagnostic test for gastric cancer prevention.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study revealed that the USF1-202G/A polymorphism appeared to be linked to an increased susceptibility to gastric cancer. Serum levels of USF1 and USF2 were higher in patients with chronic gastritis and decreased with the progression of the severity of gastric lesions. The polymorphism at the USF1-202 G/A position seems to have a reducing effect on USF1 expression. Besides, a positive correlation between USF1 and USF2 was noted, suggesting a collaborative cellular activity between these two transcription factors. Despite that further studies on larger populations and diverse ethnicities are needed to better understand the impact of USF1-202 G/A polymorphism and USF1/USF2 serum levels on gastric cancer susceptibility, coupling these two markers constitute a promising diagnostic approach to identify at the earliest patients highly susceptible to gastric cancer development.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments: We acknowledge Meryem Khyati, PhD, from the Laboratory of Onco-Virology, Institut Pasteur of Morocco, and Dr Abdel-Jabbar Maid from the Regional Transfusion Center of Cas-ablanca. We also acknowledge the team of the Laboratory of Histo-Cytopathology, Institut Pasteur of Morocco. We deeply thank our patients for their participation, and we ask for their recovery and good health.

Author contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, ET, FM.; methodology, GB, JMR, HB, FM validation, GB, JMR, HB, FM.; formal analysis, GB, JMR, HB, FM investigation, GB, JMR, HB, EI, IE, VM, ET, FM, resources, GB, BW.; writing—original draft preparation, GB, FM.; writing—review and editing, GB, ET, FM; supervision, FM.; project administration, FM.; funding acquisition, ET, FM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by INSTITUT PASTEUR Paris, as a Pasteur International Concerted action, grant number ACIP2015-10 to ET and FM. It was also supported by the Institut Pasteur of Morocco.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study protocol has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards and was approved by the committee of Pasteur Institute of Morocco.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Eliette Touati, Email: eliette.touati@pasteur.fr.

Fatima Maachi, Email: fatimamaachi09@gmail.com.

References

- Baron Y, Corre S, Mouchet N, Vaulont S, Prince S, Galibert MD (2012) USF-1 is critical for maintaining genome integrity in response to UV-induced DNA photolesions. PLoS Genet 8(1):e1002470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouafia A, Corre S, Gilot D, Mouchet N, Prince S, Galibert MD (2014) p53 requires the stress sensor USF1 to direct appropriate cell fate decision. PLoS Genet 10(5):e1004309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bounder G, Jouimyi MR, Boura H, Touati E, Michel V, Badre W et al (2020) Associations of the -238(G/A) and -308(G/A) TNF-α promoter polymorphisms and TNF-α serum levels with the susceptibility to gastric precancerous lesions and gastric cancer related to Helicobacter pylori infection in a moroccan population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 21(6):1623–1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68(6):394–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussière FI, Michel V, Mémet S, Avé P, Vivas JR, Huerre M et al (2010) H. pylori-induced promoter hypermethylation downregulates USF1 and USF2 transcription factor gene expression. Cell Microbiol 12(8):1124–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2014) Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 513(7517):202–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JTC, Yang HT, Wang TCV, Cheng AJ (2005) Upstream stimulatory factor (USF) as a transcriptional suppressor of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) in oral cancer cells. Mol Carcinog 44(3):183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Szentirmay MN, Pawar SA, Sirito M, Wang J, Wang Z et al (2006) Tumor-suppression function of transcription factor USF2 in prostate carcinogenesis. Oncogene 25(4):579–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne M, Rowland M (2019) The role of host genetic polymorphisms in Helicobacter pylori mediated disease outcome. Adv Exp Med Biol 1149:151–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corre S, Galibert MD (2005) Upstream stimulating factors: highly versatile stress-responsive transcription factors. Pigment Cell Res 18(5):337–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corre S, Galibert MD (2006) USF as a key regulatory element of gene expression. Med Sci MS 22(1):62–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa L, Corre S, Michel V, Luel KL, Fernandes J, Ziveri J et al (2020) USF1 defect drives p53 degradation during Helicobacter pylori infection and accelerates gastric carcinogenesis. Gut 69(9):1582–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristescu R, Lee J, Nebozhyn M, Kim KM, Ting JC, Wong SS et al (2015) Molecular analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. Nat Med 21(5):449–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan YM, Hernesniemi J, Oksala N, Levula M, Raitoharju E, Collings A et al (2014) Upstream transcription factor 1 (USF1) allelic variants regulate lipoprotein metabolism in women and USF1 expression in atherosclerotic plaque. Sci Rep 4:4650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel S, Kay G, Nechushtan H, Razin E (1998) Nuclear translocation of upstream stimulating factor 2 (USF2) in activated mast cells: a possible role in their survival. J Immunol 161(6):2881–2887 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goueli BS, Janknecht R (2003) Regulation of telomerase reverse transcriptase gene activity by upstream stimulatory factor. Oncogene 22(39):8042–8047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail PM, Lu T, Sawadogo M (1999) Loss of USF transcriptional activity in breast cancer cell lines. Oncogene 18(40):5582–5591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HS, Kim KS, Chung YJ, Chung HK, Min YK, Lee MS et al (2007) USF inhibits cell proliferation through delay in G2/M phase in FRTL-5 cells. Endocr J 54(2):275–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khattar NH, Lele SM, Kaetzel CS (2005) Down-regulation of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor in non-small cell lung carcinoma: correlation with dysregulated expression of the transcription factors USF and AP2. J Biomed Sci 12(1):65–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum BJ, Pognonec P, Roeder RG (1992) Definition of the transcriptional activation domain of recombinant 43-kilodalton USF. Mol Cell Biol 12(11):5094–5101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulis A, Buckle A, Boussioutas A (2019) Premalignant lesions and gastric cancer: current understanding. World J Gastrointest Oncol 11(9):665–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauren P (1965) The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 64:31–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Sawadogo M (1996) Antiproliferative properties of the USF family of helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93(3):1308–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocellin S, Verdi D, Pooley KA, Nitti D (2015) Genetic variation and gastric cancer risk: a field synopsis and meta-analysis. Gut 64(8):1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe GM, Nguyen VT, Tang LP, Benveniste EN (2001) IFN-γ regulation of class II transactivator promoter IV in macrophages and microglia: involvement of the suppressors of cytokine signaling-1 protein. J Immunol 166(4):2260–2269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar SA, Szentirmay MN, Hermeking H, Sawadogo M (2004) Evidence for a cancer-specific switch at the CDK4 promoter with loss of control by both USF and c-Myc. Oncogene 23(36):6125–6135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren YQ, Li QH, Liu LB (2016) USF1 prompt melanoma through upregulating TGF-β signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 20(17):3592–3598 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeneevassen L, Bessède E, Mégraud F, Lehours P, Dubus P, Varon C (2021) Gastric cancer: advances in carcinogenesis research and new therapeutic strategies. Int J Mol Sci 22(7):3418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setia N, Agoston AT, Han HS, Mullen JT, Duda DG, Clark JW et al (2016) A protein and mRNA expression-based classification of gastric cancer. Mod Pathol off J US Can Acad Pathol Inc 29(7):772–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirito M, Lin Q, Maity T, Sawadogo M (1994) Ubiquitous expression of the 43- and 44-kDa forms of transcription factor USF in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 22(3):427–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirito M, Lin Q, Deng JM, Behringer RR, Sawadogo M (1998) Overlapping roles and asymmetrical cross-regulation of the USF proteins in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95(7):3758–3763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Zhu M, Li H, Liu B, Yan Z, Wang W et al (2018) USF1 promotes the development of knee osteoarthritis by activating the NF-κB signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med 16(4):3518–3524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Liu G, Zuo C, Liu C, He W, Chen H (2019) Genetic polymorphisms and gastric cancer risk: a comprehensive review synopsis from meta-analysis and genome-wide association studies. Cancer Biol Med 16(2):361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven A (2011) USF1 (upstream transcription factor 1). Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol 15(1):73–76 [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Yao S, Jiang H, Dong J, Cui X, Tian X et al (2018) Upstream transcription factor 1 prompts malignancies of cervical cancer primarily by transcriptionally activating p65 expression. Exp Ther Med. 10.3892/etm.2018.6758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Weigert C, Brodbeck K, Sawadogo M, Häring HU, Schleicher ED (2004) Upstream stimulatory factor (USF) proteins induce human TGF-β1 gene activation via the glucose-response element–1013/–1002 in mesangial cells up-regulation of USF activity by the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway. J Biol Chem 279(16):15908–15915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye H, Liu XJ, Hui Y, Liang YH, Li CH, Wan Q (2018) USF1 gene polymorphisms may associate with the efficacy and safety of chemotherapy based on paclitaxel and prognosis in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Neoplasma 65(1):153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q, Bu Q, Li G, Zhang J, Cui T, Zhu R et al (2016) Association between single nucleotide polymorphisms of upstream transcription factor 1 (USF1) and susceptibility to papillary thyroid cancer. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 84(4):564–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Handel MV, Schartner JM, Hagar A, Allen G, Curet M et al (2007) Regulation of IL-10 expression by upstream stimulating factor (USF-1) in glioma-associated microglia. J Neuroimmunol 184(1–2):188–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M (2015) Common polymorphisms in the USF1 Gene and Cancer Susceptibility: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Cancer Clin Res [Internet]. 31 oct 2015 [cité 1 févr 2019];2(4). Disponible sur: https://clinmedjournals.org/articles/ijccr/international-journal-of-cancer-and-clinical-research-ijccr-2-025.php?jid=ijccr

- Zhao X, Wang T, Liu B, Wu Z, Yu S, Wang T (2015) Significant association between upstream transcription factor 1 rs2516839 polymorphism and hepatocellular carcinoma risk: a case-control study. Tumour Biol J Int Soc Oncodevelopmental Biol Med 36(4):2551–2558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Zhu HQ, Ma CQ, Li HG, Liu FF, Chang H et al (2014) Two polymorphisms of USF1 gene (-202G>A and -844C>T) may be associated with hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility based on a case-control study in Chinese Han population. Med Oncol Northwood Lond Engl 31(12):301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Casado M, Vaulont S, Sharma K (2005) Role of upstream stimulatory factors in regulation of renal transforming growth factor-beta1. Diabetes 54(7):1976–1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.