Abstract

New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases (NDM), encoded by the blaNDM gene, mediate carbapenem resistance, posing serious threats to public health due to their global presence across diverse hosts and environments. The blaNDM is prominently carried by the IncX3 plasmid, which encodes a Type IV secretion system (T4SS) responsible for plasmid conjugation. This T4SS has been shown to be phenotypically silenced by a plasmid-borne H-NS family protein; however, the underlying mechanisms of both silencing and silencing relief remain unclear. Herein, we identified HppX3, an H-NS family protein encoded by the IncX3 plasmid, as a transcription repressor. HppX3 binds to the T4SS promoter (PactX), downregulates T4SS expression, thereby inhibits plasmid conjugation. RNA-seq analysis revealed that T4SS genes are co-regulated by HppX3 and VirBR, a transcription activator encoded by the same plasmid. Mechanistically, VirBR acts as a counter-silencer by displacing HppX3 from PactX, restoring T4SS expression and promoting plasmid conjugation. A similar counter-silencing mechanism was identified in the T4SSs of IncX1 and IncX2 plasmids. These findings provide new insights into the regulatory mechanisms controlling T4SS expression on multiple IncX plasmids, including the IncX3, explaining the persistence and widespread of blaNDM-IncX3 plasmid, and highlight potential strategies to combat the spread of NDM-positive Enterobacterales by targeting plasmid-encoded regulators.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

The emergence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) has become a significant health burden due to infections that are difficult to treat [1]. CRE, particularly those producing New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM)-type carbapenemase, are widely disseminated across humans, animals, and the environment [2, 3]. NDM, encoded by the blaNDM gene, hydrolyzes almost all β-lactams, including carbapenems [4, 5]. Among the 70 identified blaNDM variants (blaNDM-1–blaNDM-70), blaNDM-5 and blaNDM-1 are the most prevalent, accounting for 74.1% and 16.6% in 1774 NDM-positive Escherichia coli strains, respectively [6]. The blaNDM is predominantly carried by the IncX3 plasmid, which has been reported in over 40 countries due to its efficient conjugation and minimal fitness cost to the bacterial host [7–11].

Conjugation plays a critical role in plasmid dissemination [12, 13]. Most IncX3 plasmids possess conjugation machinery that enables their transfer between bacteria via the Type IV secretion system (T4SS), which generally consists of 12 core subunits spanning the bacterial cell envelope [14–17]. Although essential for conjugation, this energy-intensive process imposes a fitness cost on the host bacteria, requiring tight regulation of T4SS expression [18, 19]. Such regulation has been extensively studied in the tra-T4SS system of the F plasmid, where expression is activated by the plasmid-borne transcription regulator TraJ and repressed by both the plasmid-encoded fertility inhibition system FinOP and the chromosomal histone-like nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS) [20, 21].

H-NS, a well-studied nucleoid-associated protein in Enterobacterales, binds AT-rich DNA regions to form filaments and/or bridges, blocking RNA polymerase (RNAP) access, thereby silencing gene expression and reducing associated fitness costs [22–28]. H-NS is particularly effective at binding mobile genetic elements (MGEs), which are typically AT-rich, helping the integration of some beneficial genes from MGEs into host regulatory circuits [29]. Some MGEs encode H-NS homologs to repress their own genes, minimizing fitness cost, such as Sfh from IncH1 in Shigella flexneri and Acr2 from IncA/C in E. coli [30–32]. In IncX3, the T4SS is phenotypically repressed by a plasmid-borne H-NS-like protein, although the precise mechanism of this repression remains unclear [33, 34].

To counteract H-NS-mediated gene silencing, bacteria recruit transcription activators or counter-silencers that displace H-NS family proteins from promoter regions, restoring gene expression [35, 36]. For instance, ArcA in E. coli, a component of the Arc two-component system, binds the promoters of several virulence genes, countering H-NS repression [37, 38]. Some horizontally acquired elements also encode counter-silencers, such as CsgD from the csg locus in Salmonella and MxiE protein from virulence plasmid in S. flexneri [39, 40]. Similarly, in IncX3, VirBR, a recently identified transcription regulator, activates T4SS expression, thereby enhancing plasmid conjugation [41]. Given that IncX3 conjugation is downregulated by an H-NS-like protein, the role of VirBR as a potential counter-silencer warrants further investigation.

Here, we identified the H-NS-like protein encoded by the IncX3 plasmid, designated HppX3, as a functional member of the H-NS family that binds to both the E. coli chromosome and IncX3 plasmid. Specifically, HppX3 binds to the actX promoter (PactX), controlling T4SS gene expression, inhibiting plasmid conjugation, and reducing associated fitness cost. We further demonstrated that T4SS is co-regulated by HppX3 and VirBR, with VirBR displacing HppX3 from PactX both in vivo and in vitro, restoring T4SS expression and enhancing plasmid conjugation. Similar regulatory mechanisms were identified in the T4SSs of IncX1 and IncX2 plasmids. Collectively, these findings offer new insights into the regulation of T4SS on the IncX3 plasmid and may explain the global spreading of blaNDM-IncX3 plasmid.

Materials and methods

Alignment of H-NS homologs

The amino acid sequences of H-NS (NP_415753.1), StpA (NP_417155.1), and Sfx (WP_001282381.1) were selected to align with HppX3 using MAFFT version 7 [42]. The results were visualized with ESPript 3.0 [43], and sequence identity was derived using NCBI Blastp (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Bacterial strains and gene deletion

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Escherichia coli strains were cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth with shaking at 200 revolutions per minute (RPM) or on LB agar plates at 37°C or 30°C, depending on the experiment. Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations when necessary: 0.5 mg/l meropenem, 50 mg/l chloromycetin, 50 mg/l apramycin, 50 mg/l kanamycin, 50 mg/l ampicillin, and 50 mg/l sodium azide. Gene deletions (hppX3, h-ns, virBR, and T4SS cluster in p3R-4; hppX3pQD419 in pQD419; sfx in R6K) were constructed using λ-RED as previous described [44]. Primers used for plasmid construction and gene deletions are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing and chromatin immunoprecipitation quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed following previously reported methods, with modifications [35]. Briefly, bacteria were inoculated in 40 ml LB broth with antibiotics, grown for 6 h, and crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde at 37°C for 30 min. Arabinose (20%) was added at a 1:100 volume ratio 2 h before crosslinking when required. Crosslinking was quenched with 1.6 ml of 2.5 M glycine. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffer solution (PBS) three times, and cell pellets were stored at –80°C.

Cells were lysed in B-PER bacterial protein extraction reagent (Thermo Scientific, USA) containing 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 50 μg/ml lysozyme and 1 × protease inhibitors (Beyotime, China) at room temperature for 30 min on a HulaMixer. The cell lysates were sonicated with a Covaris M220 sonicator (75 peak power, 5% duty factor, 200 cycles/burst, 8 min duration). After centrifugation at 15 000 RPM for 15 min at 4°C, 20 μl of the supernatant was taken as Input DNA. Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-FLAG affinity gel (Beyotime, China). Samples were washed with Tris-buffered saline and eluted with 150 μg/ml 3 × FLAG solution at 4°C for 1 h on a HulaMixer. DNA (including Input DNA) was dissociated from the protein using 1.8 mg/ml proteinase K for 2 h at 42°C and incubated for 16 h at 65°C. ChIP and Input DNA was purified using the MinElute polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Purification Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) was performed by Sinobiocore (China). Sequence enrichment in the ChIP group compared to the input group was calculated using bamCompare (Galaxy Version 3.5.4) and visualized using IGV v2.17.4 [45]. For chromatin immunoprecipitation quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR), the actX promoter was chosen as the target and the ompA gene was the negative control [46]. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table S2. DNA enrichment was quantified using the “Relative fold enrichment = 2CTInput-CTChIPed” [35]. Data were collected from three biological replicates with three technical replicates.

Protein expression and purification

The coding sequences of HppX3 and VirBR were cloned into pET28a vector and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. Protein expression was induced by adding of 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside for 12 h at 30°C. Induced cells were harvested, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, pH 8.0), and lysed by sonication. Filtered lysates were incubated with Ni Sepharose (Cytiva, USA) for 2 h at 4°C. After washing the resin, the recombinant proteins were eluted with elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 500 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Eluted fractions were dialyzed in PBS and concentrated using 5 kDa (His6-VirBR) or 10 kDa (His6-HppX3) cutoff centrifugal filters (Sartorius, Germany). Protein concentrations were measured using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). Purified proteins were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) was performed using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA), according to previous studies [35, 47]. Biotin-labeled probes were synthetized by Tsingke Biotech (China) based on actX promoter sequence. Binding reactions were conducted in 20 μl systems containing 1 nM DNA probe, 1 × Binding buffer, 5% glycerol, 0.05% NP-40, 5 mM MgCl2, and protein. Mixtures were incubated in room temperature for 20 min. In competitive binding assays, a secondary protein was added and incubated in room temperature for another 20 min. Samples were resolved on 4% polyacrylamide gels in 0.5 × Tris–borate–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid buffer. Probes were transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane and ultraviolet-crosslinked at 120 mJ/cm2 for 2 min. Biotin-labeled DNA was detected according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Promoter activity assay

The actX promoter in p3R-4, p19SC11DZ17RtetX4, and R6K was fused with the eGFP reporter gene in the pUC19 vector. Escherichia coli DH5α strains carrying this reporter plasmid were cultured for 6 h, centrifuged, and resuspended in PBS to OD600= 0.5. Fluorescence (excitation 488 nm, emission 525 nm) and OD600 were measured with a microplate reader (Tecan, Switzerland). Promoter activity was calculated as “Fluorescence intensity = fluorescence value/OD600” [41, 48]. Data were obtained from at least three replicates.

qPCR and RNA-seq analyses

Bacterial cultures (4 ml LB broth, 6 h) were used for total RNA extraction with an RNA isolation kit (Aidlab, China). Reverse transcription was performed using HiScript III All-in-one RT SuperMix (Vazyme, China). qPCR was performed using 60 ng of complementary DNA, Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, China), and monitored with a QuantStudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The gapA gene (Gene ID: 947 679) served as an internal control. Data were obtained from four biological replicates with three technical replicates. RNA-seq was conducted by Origingene (China). Differentially expressed genes were visualized with the R package ggplot2 v3.5.1 [49].

Plasmid conjugation assay

Plasmid conjugation was performed by solid mating, with E. coli J53 as the recipient strain [50]. Cultures were adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard, donor and recipient cells were mixed at a 1:3 volume ratio. A 50 μl sample of the mixture was spotted on microporous membrane on LB agar and incubated at 37°C for 1–3 h. As an exception, for the conjugation of IncX2 plasmid R6K, the mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Cells were plated on LB agar containing 100 mg/l sodium azide (for recipients) and 100 mg/l sodium azide with 0.5 mg/l meropenem (for transconjugants harboring IncX3 plasmid) or 100 mg/l sodium azide with 100 mg/l ampicillin (for transconjugants harboring R6K plasmid). Conjugation frequency was calculated as the ratio of transconjugant colony-forming units (CFU) to recipient CFU. Data were obtained from three biological replicates.

Bacterial growth curve and competition experiments in vitro

Overnight cultures were adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard and diluted at a 1:100 ratio in a 96-well flat-bottom plate (Corning, USA). Plates were incubated at 37°C in a microplate reader (Tecan, Switzerland) with OD600 measured every 2 h. Data was obtained from three biological replicates with three technical replicates.

In vitro competition assays followed previous methods [51]. Two pairs of strains were conducted to competition assay: (i) BW25113/p3R-4ΔhppX3::cat versus BW25113/p3R-4, (ii) BW25113/p3R-4ΔhppX3 versus BW25113/p3R-4ΔT4SS::catΔhppX3. Overnight cultures of competitor strains were adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard and mixed at a 1:1 volume ratio. Co-cultures were diluted with 1:1000 into fresh LB broth every 24 h. Mixtures at 1, 3, 5 days were plated on LB agars containing 0.5 mg/l meropenem or 0.5 mg/l meropenem with 50 mg/l chloromycetin to count CFU for total cells and BW25113/p3R-4ΔhppX3::cat (or BW25113/p3R-4ΔT4SS::catΔhppX3) cells, respectively. The CFU ratio was used to assess bacterial competition capacity. Data were obtained from three biological replicates.

Bioinformation analyses, statistics, and figures

Sequence alignment of IncX3 plasmids was visualized by Easyfig v2.2.5 [52]. The origin-of-transfer (oriT) sites were labeled according to [53]. Statistical analyses were performed by GraphPad Prism software v9.3.1, with details provided in the figure legends. Figures were generated by GraphPad Prism software v9.3.1, R v4.4.0, IGV v2.17.4, and Proksee (https://proksee.ca/).

Results

HppX3 is a functional H-NS family protein encoded by the IncX3 plasmid

Escherichia coli encodes two intact chromosome-borne H-NS family proteins, H-NS and its homolog StpA, which shares 58% amino acid (aa) sequence identity and can generally substitute for each other [54, 55]. These proteins contain two key domains: the N-terminal dimerization and oligomerization domain, and the C-terminal DNA-binding domain, enabling them to bind DNA and silence gene expression [24]. Previous studies have shown that the IncX3-encoded H-NS-like protein, designated HppX3 (H-NS plasmid proteins from incompatibility group X3) [56], represses plasmid conjugation [33, 34], though the mechanism remains unknown. Given that HppX3 shares 47% and 53% aa sequence identity with H-NS and StpA, respectively, we hypothesized that HppX3 functions similarly in DNA-binding and gene silencing (Supplementary Fig. S1).

To investigate the DNA-binding profile of HppX3, we performed ChIP-seq analysis. The blaNDM-5-IncX3 plasmid p3R-4 from a chicken E. coli strain was introduced into E. coli K-12 BW25113 (BW25113/p3R-4). The native hppX3 gene was knocked out (BW25113/p3R-4ΔhppX3) and complemented with a hppX3-FLAG allele (BW25113/p3R-4ΔhppX3 + hppX3-FLAG), confirming that the FLAG-tag did not interfere with HppX3 function (Supplementary Fig. S2). ChIP-seq analysis of BW25113/p3R-4ΔhppX3 + hppX3-FLAG revealed 321 binding peaks on the chromosome and 3 peaks on p3R-4 (Fig. 1A and B, Dataset S1). Of these, ∼62% (198/321) of HppX3 chromosomal binding peaks overlapped with H-NS binding sites (GEO Accession Nos. GSM5511060, GSM5511061), and 64% (206/321) overlapped with StpA binding sites (GEO Accession Nos. GSM5511074, GSM5511075), suggesting that HppX3 may share functions with H-NS and StpA. On the IncX3 plasmid, HppX3 binding was concentrated in AT-rich regions, particularly near the plasmid replication gene repB and T4SS gene cluster (Fig. 1B). Notably, HppX3 bound to the elements that contribute to plasmid conjugation transfer, such as relaxosome gene taxA/C, promoter of virB/D4 T4SS (including type IV coupling protein gene virD4), and two origin-of-transfer (oriT), suggesting its role in regulating conjugation. To further explore the regulatory role of HppX3, we randomly selected ten chromosome-borne and five plasmid-borne genes near the binding peaks for qPCR analysis. The expression of all chromosomal target genes remained unchanged, regardless of HppX3 presence (Fig. 1C). However, all selected plasmid-borne targets were transcriptionally repressed by HppX3 (Fig. 1C), including three T4SS-associated genes virBR, actX, and virD4, indicating that HppX3 is a functional H-NS family protein capable of binding bacterial DNA and may regulate genes involved in IncX3 T4SS.

Figure 1.

HppX3 binds to bacterial DNA and regulates plasmid genes. (A) Comparison of binding peaks of HppX3, H-NS and StpA across BW25113 chromosome. Three biological replicates of HppX3 are presented. (B) Binding peaks of three biological replicates of HppX3 across p3R-4 plasmid. The guanine-cytosine (GC) content and annotation of the plasmid sequence are presented below. ChIP-seq profiles, GC content, and sequence annotation were visualized with IGV v2.17.4, Proksee (https://proksee.ca/, window size = 10 000 bp for BW25113 chromosome, window size = 500 bp for p3R-4), and Easyfig v2.2.5, respectively. (C) Relative messenger RNA (mRNA) abundance of the randomly selected genes nearby the HppX3 binding peaks on BW25113 chromosome and p3R-4 plasmid, in BW25113/p3R-4 and its derivates. * for P< .05, ** for P< .01, *** for P< .001, compared with “BW25113/p3R-4”, based on one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test.

HppX3 is a transcription repressor of T4SS

To determine whether IncX3 T4SS genes are regulated by HppX3, we performed RNA-seq on a chicken-origin E. coli isolate 3R, which contains one chromosome and four plasmids, including p3R-4 (Supplementary Table S3). By comparing transcript levels between the wild-type strain (3R) and an hppX3 deletion mutant (3RΔhppX3), we identified 58 genes regulated by HppX3 (|log2FoldChange|>2, P< .05), with 52 of these genes being repressed (Fig. 2A, Dataset S2). Notably, genes involved in conjugative transfer, including virBR, taxA/C, actX, and T4SS core subunit genes virB1-11/D4, were strongly repressed by HppX3. Consequently, deletion of hppX3 increased the conjugation frequency of the IncX3 plasmid by nearly 2.5 logs (P < .0001) in BW25113 and 4 logs (P < .05) in 3R, while complementation with HppX3 restored the frequency to wild-type levels (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S3). Notably, 63% (33/52) of the genes repressed by HppX3 were located on the IncX3 plasmid, with 37% (19/52) in the chromosome, and none on the other plasmids (Dataset S2). Further, genes on IncX3 exhibited higher fold changes in expression compared to chromosomal genes (Supplementary Fig. S4), indicating that HppX3 exerts a stronger regulatory effect on plasmid-borne genes. These data, along with the qPCR results showing preferential repression of IncX3 genes (Fig. 1C), confirm that HppX3 primarily silences genes on the IncX3 plasmid.

Figure 2.

HppX3 repress the expression of T4SS, thereby repressing the plasmid conjugation and plasmid’s fitness cost. (A) Volcano plot of transcripts for all genes in 3RΔhppX3 versus 3R. The differentially expressed genes are represented by different dots. (B) Conjugation frequencies of IncX3 plasmid p3R-4 in strains with hppX3 knocked out or complemented by pACYC184 plasmid. **** for P< .0001, ns for not significant, compared with “BW25113/p3R-4”, based on one way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. (C) EMSA reactions containing 1 nM biotin-labeled PactX DNA and His6-HppX3 protein (0.4, 0.8, 1.6, 3.2 μg). Lane denotes “−” contained no protein. (D) Fluorescence intensity of eGFP under the control of PactX. The PactX-eGFP is carried by pUC19 vector transformed into E. coli DH5α along with pACYC184 carrying hppX3 and hppX3ΔNTD (the empty vector was used as a negative control). * for P< .05, ns for not significant, compared with “Vector”, based on one way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. (E) Relative mRNA abundance of actX, virB6, and virD4 in BW25113/p3R-4 (wild type-wild type, WT–WT), BW25113/p3R-4ΔhppX3 (WT-ΔhppX3), BW25113Δh-ns/p3R-4 (Δh-ns-WT), and BW25113Δh-ns/p3R-4ΔhppX3 (Δh-ns-ΔhppX3). **** for P< .0001, ns for not significant, compared with “WT–WT”, based on one way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. (F) Growth curve of BW25113/p3R-4 and BW25113/p3R-4ΔhppX3. **** for P< .0001 compared with “BW25113/p3R-4″, based on Student’s t-test for the OD600 values at 24 h. (G) In vitro competition between BW25113/p3R-4ΔhppX3 (ΔhppX3) and BW25113/p3R-4 (WT) in LB broth. * for P< .05, ns for not significant, compared with “1 day”, based on one way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test.

Since T4SS is responsible for plasmid DNA transfer, and the IncX3 T4SS genes (including upstream gene actX) are controlled by the promoter of actX (PactX), we further explored how HppX3 regulates PactX [16, 41]. EMSA using a His6-tagged HppX3 protein confirmed that the biotin-labeled PactX DNA probe shifted to a higher molecular weight when incubated with purified His6-HppX3, in which the N-terminal His6-tag did not impair the function of HppX3 (Supplementary Fig. S2), indicating direct binding between HppX3 and PactX (Fig. 2C). To verify the regulatory role of HppX3, we fused PactX to an eGFP reporter gene and observed reduced promoter activity in the presence of HppX3 (Fig. 2D). However, HppX3 lacking the N-terminal dimerization domain (HppX3ΔNTD) failed to repress PactX activity, suggesting that oligomerization is critical for HppX3 function, consistent with other H-NS family regulators [57, 58]. Knocking out hppX3 led to de-repression of PactX, increasing T4SS gene expression and plasmid conjugation frequency (Fig. 2E and B). These results indicate that HppX3 binds directly to PactX, repressing T4SS gene transcription, reducing mRNA levels, and inhibiting IncX3 plasmid conjugation.

Conjugative plasmid T4SS systems are usually repressed when not needed, reducing fitness costs and promoting plasmid spreading [19, 59]. As expected, uncontrolled T4SS expression in the hppX3 mutant imposed a fitness burden on the host, evidenced by slower growth (Fig. 2F) and reduced competitive ability compared to strains carrying the wild-type plasmid (Fig. 2G and Supplementary Fig. S5). Notably, T4SS repression was specific to HppX3 and not mediated by H-NS (Fig. 2E), suggesting that HppX3 acts as a specialized transcription repressor for IncX3 T4SS, alleviating plasmid-associated fitness costs.

HppX3 and VirBR co-regulate the expression of T4SS

Given the high mobility of the IncX3 plasmid, which suggests that the conjugative machinery is not continuously suppressed to minimize fitness costs, we hypothesized that a counter-silencer neutralizes the repressive effects of HppX3. The plasmid-encoded transcription regulator VirBR emerged as a likely candidate to antagonize HppX3 and restore conjugative transfer [41]. In a previous study, we demonstrated that VirBR directly binds to PactX, increasing T4SS gene expression and enhancing conjugation transfer. Additionally, both hppX3 and virBR are located on the highly conserved IncX3 plasmid backbone, suggesting they coevolved with the T4SS (Supplementary Fig. S6). Transcriptomic analysis of the 3R strain overexpressing virBR (Fig. 3A and B; GSA Accession Nos. CRR1073487-CRR1073489) further confirmed that VirBR activates T4SS genes. Since these same genes are repressed by HppX3, we concluded that T4SS genes are co-regulated by both HppX3 and VirBR (Fig. 3C, Dataset S2). We hypothesize that VirBR displaces HppX3 from PactX, lifting the repression and allowing T4SS gene expression.

Figure 3.

HppX3 and VirBR co-regulate the T4SS. (A) Volcano plot of transcripts for all genes in 3RΔvirBR/pUC19-virBR versus 3R. The differentially expressed genes are represented by different dots. (B) Fold changes of conjugation-associated genes in 3RΔhppX3 and 3RΔvirBR/pUC19-virBR, compared with 3R. (C) Genes regulated by HppX3 and VirBR according to the RNA-seq data.

VirBR displaces HppX3 at PactX in vivo and in vitro

To determine whether VirBR affects the DNA-binding capacity of HppX3 at PactX in vivo, we performed ChIP-qPCR. The native hppX3 in BW25113/p3R-4 was replaced with an hppX3-FLAG allele, and virBR (or the RFP gene as a negative control) was cloned into an arabinose-inducible expression vector pBAD. Overexpression of VirBR resulted in reduced enrichment of PactX DNA, suggesting that HppX3 binds less effectively to PactX in the presence of VirBR (Fig. 4A). Consistently, promoter activity assays showed that VirBR counteracts HppX3’s repression of PactX (Fig. 4B). However, when the VirBR binding site within PactX was replaced, VirBR could no longer activate the promoter previously silenced by HppX3, confirming that VirBR’s binding to this specific DNA region is essential for counter-silencing (Fig. 4B, lower panel). Further, substituting key amino acids in VirBR (R20, R42, and R67) with alanine (VirBRM), which disrupts its DNA-binding ability, also prevented the de-repression of the promoter, further emphasizing the necessity of VirBR’s binding function (Fig. 4C) [41]. These results demonstrate that VirBR displace HppX3 from PactX in vivo.

Figure 4.

VirBR antagonizes HppX3 at PactX. (A) In vivo binding of HppX3 to the actX promoter and ompA coding region determined by ChIP-qPCR. The ChIP was conducted in a BW25113/p3R-4 strain that expressing HppX3-FLAG, harboring pBAD-virBR or pBAD-RFP (negative control). The ChIP DNA was enriched using anti-FLAG beads and quantified by qPCR. * for P< .05, ns for not significant, based on Student’s t-test. (B) Fluorescence intensity of eGFP under the control of PactX or its derivate in the presence of HppX3 with or without VirBR. The actX promoter (300-bp-fragment upstream of actX start codon) was fused with eGFP reporter gene on the pUC19 vector and hppX3 (or with virBR) was cloned into pACYC184 vector. Left panel: Schematic representation of reporter conducts tagged with eGFP, the putative VirBR binding site is marked by solid or hollow blocks. Right panel: Fluorescence intensity ratio normalized to “HppX3” group. * for P< .05, ns for not significant, based on Student’s t-test. (C) Fluorescence intensity of eGFP under the control of PactX in the presence of HppX3 with or without VirBR or VirBRM (R20A, R42A, and R67A). **** for P< .0001, ns for not significant, compared with “HppX3”, based on one way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. (D) EMSA reactions containing 1 nM biotin-labeled PactX DNA, His6-HppX3 protein (0.8 μg) and His6-VirBR protein (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 μg). Lane denotes “−” contained no protein. (E) Relative mRNA abundance of actX, virB6, and virD4 in BW25113/p3R-4ΔhppX3 (ΔhppX3) and its derivates. Different letters indicate significant differences between strains, based on one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (F) Conjugation frequency of p3R-4ΔhppX3 plasmid in BW25113 and strains complemented with hppX3, virBR, or virBRM. *** for P< .001, ns for not significant, based on one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

To confirm this competition between VirBR and HppX3 at PactX in vitro, we conducted EMSA using a PactX DNA probe. Increasing concentrations of VirBR progressively shifted the migration pattern of the protein-DNA complex to resemble that of the VirBR-DNA complex alone (Fig. 4D), indicating that VirBR displaces HppX3 from PactX DNA. As expected, de-repression of PactX by VirBR, but not VirBRM, led to the increased T4SS gene expression and higher conjugation frequency (Fig. 4E and F). Together, these in vivo and in vitro results provide evidence that VirBR directly competes with HppX3 for binding at the T4SS promoter, displacing HppX3 and alleviating the repression of T4SS gene expression, thus promoting conjugation transfer. Beyond T4SS regulation, VirBR also counter-silenced HppX3 in the regulation of additional potentially functional genes, including parB (putative partitioning protein), ABP (putative ATP-binding protein), and topB (putative type III topoisomerase) (Supplementary Fig. S7). These results suggest that the interplay between VirBR and HppX3 plays a broader role in plasmid-associated gene regulation.

The counter-silencing of VirBR-like proteins against H-NS homologs is conserved across multiple IncX plasmids

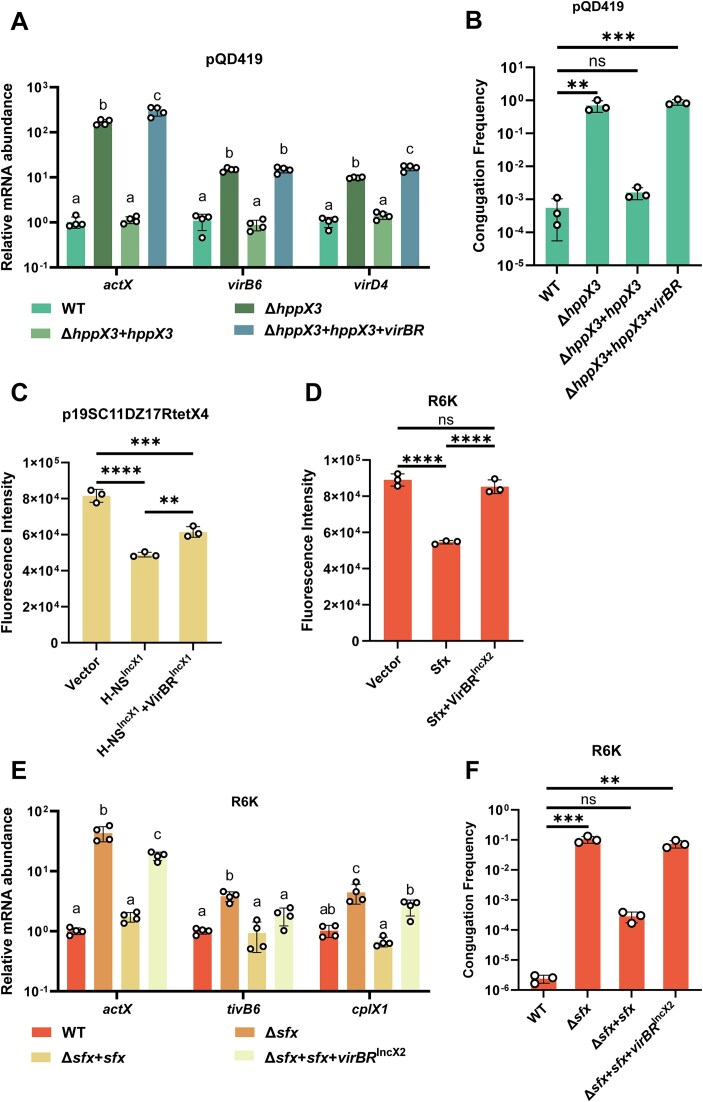

To determine whether VirBR-mediated counter-silencing of HppX3 is specific to the p3R-4 plasmid, we introduced the blaNDM-1-IncX3 plasmid pQD419 into E. coli BW25113 and knocked out hppX3pQD419. Consistent with our observations in p3R-4, deletion of hppX3pQD419 led to increased T4SS gene expression and enhanced conjugation frequency, while complementation of hppX3pQD419 restored repression (Fig. 5A and B). Furthermore, introduction of VirBRpQD419 alleviated T4SS repression and further promoted the conjugation of pQD419, confirming that VirBR-mediated counter-silencing of HppX3 is conserved in IncX3 plasmids.

Figure 5.

The regulatory interplay between plasmid-borne H-NS family protein and VirBR-like protein is conserved in IncX1, IncX2, and IncX3 plasmids. (A) Relative mRNA abundance of actX, virB6, and virD4 in BW25113/pQD419 (WT) and its derivates. Different letters indicate significant differences between strains, based on one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (B) Conjugation frequencies of IncX3 plasmid pQD419 in BW25113 (WT) and its derivates. ** for P< .01, *** for P< .001, ns for not significant, compared with “WT”, based on one way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. (C) Fluorescence intensity of eGFP under the control of IncX1 T4SS promoter in the presence of H-NSIncX1 or H-NSIncX1 and VirBRIncX1. ** for P< .01, *** for P< .001, **** for P< .0001, based on one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (D) Fluorescence intensity of eGFP under the control of IncX2 T4SS promoter in the presence of Sfx or Sfx and VirBRIncX2. **** for P< .0001, ns for not significant, based on one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (E) Relative mRNA abundance of actX, tivB6, and cplX1 in BW25113/R6K (WT) and its derivates. Different letters indicate significant differences between strains, based on one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (F) Conjugation frequencies of IncX2 plasmid R6K in BW25113 (WT) and its derivates. ** for P< .01, *** for P< .001, ns for not significant, compared with “WT”, based on one way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test.

Multiple IncX plasmids, including IncX1, IncX2, and IncX3, share homologous T4SS genes and associated regulatory elements [41, 60]. Based on this, we hypothesized that these T4SSs may exhibit similar regulatory mechanisms, where plasmid-encoded H-NS homologs repress T4SS gene expression, and VirBR homologs relieve this repression. To test this, we examined the IncX1 plasmid p19SC11DZ17RtetX4 and IncX2 plasmid R6K (GenBank accession No. LT827129.1). We found that the T4SS promoters of both IncX1 and IncX2 plasmids were repressed by their respective H-NS homologs and were either partially or fully counter-silenced by their VirBR homologs (Fig. 5C and D). To further validate this regulatory mechanism, we knocked out the sfx gene (encoding the H-NS homolog) in R6K. As expected, deletion of sfx increased the T4SS gene expression and conjugation frequency, while complementation restored repression (Fig. 5E,F). As observed in IncX3 plasmids, the introduction of VirBR homolog counter-silenced Sfx, upregulating T4SS gene expression and promoting plasmid conjugation. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the interplay between VirBR-like proteins and H-NS homologs is a conserved regulatory strategy across IncX1, IncX2, and IncX3 plasmids, providing a broad mechanism for controlling T4SS expression and plasmid conjugation in the IncX family.

Discussion

The IncX3 plasmid is the most common vector for antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) spreading across the Enterobacterales [9]. Despite the prohibition of carbapenem use in animals, blaNDM-IncX3 plasmid-carrying strains have been commonly detected in livestock, farming environments, and manure waste [61]. The ability of IncX3 plasmid to horizontal transfer via conjugation, coupled with its high stability and minimal fitness cost to the bacterial host, has contributed to its global presence [11, 62]. Theoretically, the expression of conjugation-associated T4SS is a major cost of plasmids to their hosts, requiring tight regulation that represses these genes [19, 63]. However, this regulation in IncX3 remains largely unclear. Here we identified HppX3, an H-NS family protein encoded by IncX3 plasmid, as a local transcription repressor of T4SS genes. HppX3 binds to PactX promoter, represses T4SS expression, and downregulates plasmid conjugation. These findings provide deeper insights into the previously reported H-NS-like protein encoded by IncX3 plasmids [33, 34]. The unregulated expression of T4SS in strains lacking HppX3 leads to reduced growth rate and competitiveness, highlighting the essential role of HppX3 in limiting fitness costs of the IncX3 plasmid and promoting its dissemination. Similar to other H-NS family repressors [57, 58], the inability of the HppX3ΔNTD mutant to repress PactX suggests that oligomerization, mediated by the N-terminal domain, is crucial for its gene-silencing function. Additionally, like other H-NS homologs encoded by IncX plasmids, HppX3 contains an RGR AT-hook motif, which may help target specific genes, providing a selective advantage that enhances the regulation of T4SS independent of chromosomal H-NS [58].

MGEs, such as those carrying ARGs and virulence genes, often introduce new traits to their host and must be integrate into host regulatory circuits [64, 65]. During this adaptation, MGEs typically exhibit higher AT-content, which attracts gene silencers like H-NS in proteobacteria to repress their expression and reduce fitness costs [23, 29]. To further minimize their burden, many MGEs encode H-NS analogs that regulate their own genes. Several IncX plasmids have been shown to carry H-NS analogs, such as the H-NS protein in tet(X4)-bearing IncX1 plasmids [66], Sfx in IncX2 [58], and HppX3 in IncX3 [33, 34]. These analogs reduce plasmid-associated fitness costs by inhibiting the expression of ARGs or conjugation genes, representing a common strategy for MGEs to adapt to their hosts. Interestingly, recent studies suggest noncanonical functions for H-NS analogs, such as the activation of plasmid partition systems in Pseudoalteromonas rubra plasmid pMBL6842, indicating these proteins may play diverse roles in plasmid stability and adaptation [67].

Similar to other plasmids, the IncX3 T4SS mediates plasmid conjugation and promotes the spread of ARGs. The expression of T4SS genes is usually tightly regulated, as exemplified by the well-studied tra-T4SS encoded in the F plasmid [20]. Our study, together with previous research, demonstrates that the virB/D4 T4SS of the IncX3 plasmid is repressed by the gene silencer HppX3 (Fig. 2) [33, 34]. To overcome this repression and activate T4SS expression when needed, bacteria employ counter-silencers such as TraJ in the F plasmid, which cooperates with ArcA [68]. For the virB/D4 T4SS of IncX3, we show that VirBR, a recently identified transcription regulator, shares regulatory targets with HppX3 and counteracts its silencing, thereby promoting T4SS expression [41]. Notably, this counter-silencing mechanism is not restricted to IncX3 plasmids but is also conserved across multiple IncX subtypes. By extending our investigation to IncX1 and IncX2 plasmids, we identified similar regulatory interactions (Fig. 5C-F). This regulatory conservation underscores the biological importance of precise T4SS control, allowing these plasmids to balance efficient conjugation with minimal fitness cost to their bacterial hosts. This finely tuned mechanism may contribute to the wide dissemination of IncX plasmids and their associated ARGs, thereby playing an essential role in the global spread of multidrug resistance.

The primary mechanism employed by counter-silencers is known as disruptive counter-silencing, where the transcription regulators remodel the H-NS-DNA complex to make gene promoters accessible to RNAP [65, 69]. For example, in Shigella, the central virulence regulator VirB binds to the promoters of silenced genes, remodeling DNA supercoils and alleviating gene silencing mediated by H-NS [70]. Some transcription regulators also employ supportive mechanisms, where the counter-silencer not only remodels nucleoprotein complexes but also assists RNAP interaction, as seen with LuxR in Vibrio harveyi [35]. In this study, we demonstrate that VirBR interferes with HppX3’s DNA-binding both in vitro and in vivo, relieving the repression of HppX3-silenced genes (Fig. 4). However, when the binding of VirBR to PactX was blocked, either by mutating its binding site or substituting key amino acids (Fig. 4B and C), it could no longer antagonize HppX3, indicating direct competition between these regulators. Although this competitive mechanism is investigated in this study, we observed that the virBR deletion partially downregulated T4SS gene expression (by 35%–84%) even in the absence of HppX3 (Supplementary Fig. S8A). This suggests that VirBR may also play a supportive role in T4SS regulation, which warrants further investigation.

Both VirBR and HppX3, belonging to IncX3 plasmid backbone, has remained highly conserved over the past decades, suggesting their evolutionary advantage in regulating T4SS expression [71]. HppX3 switches T4SS “OFF” to minimize fitness cost for host strains, while VirBR turns it “ON” under specific conditions. However, T4SS gene expression in BW25113/p3R-4ΔvirBR is nearly identical to the wild type (Supplementary Fig. S8A), similar to what was observed with PixR in the IncX4 plasmid [60]. This suggests that virBR may be nontranscribable or inactive under laboratory conditions to prevent unnecessary conjugation machinery expression. Our observation that overexpression of virBR increases actX mRNA levels supports the idea that virBR regulation likely occurs at the pre-transcriptional level (Supplementary Fig. S8B). These results highlight gaps in our understanding of IncX3 T4SS regulation, particularly concerning the signals required to activate T4SS expression.

Generally, T4SS remains “OFF” by default, and specific signals are needed to induce its activation, such as signaling molecules and environmental conditions [19]. Studies suggest that activation of the Agrobacterium T4SS, a prototype of the IncX3 T4SS, depends on the host cells-produced opines and quorum signaling molecules [19, 72]. Similarly, activation of tra-T4SS in the F plasmid begins with the relief of FinOP-mediated repression [59]. We previously demonstrated that both antibiotic amoxicillin and heavy metals feed additives can act as exogenous stimuli and promote the spreading and colonizing of IncX3-carrying bacteria [41]. Further study is needed to determine whether these signals also affect the “ON/OFF” state of IncX3 T4SS.

This study has certain limitations. First, the upstream regulatory signals controlling hppX3 expression remains to be elucidated, and further study is needed to determine the factors influencing its transcriptional regulation. Second, this study primarily examines the competition between VirBR and HppX3 in a controlled laboratory setting; however, their regulatory interplay may vary under more complex environmental conditions. Future studies should explore how varied physiological and ecological contexts influence this regulatory mechanism, especially in clinically-relevant settings.

In summary, we identified HppX3, an H-NS family protein encoded by the blaNDM-5-IncX3 plasmid, as a local gene silencer that represses T4SS expression and minimizes plasmid-associated fitness costs. VirBR serves as a counter-silencer, displacing HppX3 at PactX and promoting T4SS expression and plasmid conjugation. These findings highlight the essential role of plasmid-encoded regulators in adapting and spreading of the blaNDM-IncX3 plasmid. Given the importance of IncX3 plasmid in the spreading of carbapenemase-encoding genes, unraveling these regulatory mechanisms offers valuable strategies for curbing the global NDM spreading.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: S.Z., Z.D., Y.W., and J.S. designed this study. Y.G., N.X., and T.M. performed gene deletion, EMSA, and promoter activity assays. N.X. and Z.W. contributed to the expression and purification of HppX3 and VirBR protein. Y.G. and C.T. performed qPCR and plasmid conjugation assays. Y.G., N.X., and Z.D. analyzed the ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data. R.Z. provided the strains. Y.G. and Y.W. wrote the manuscript. S.Z., Z.D., Y.W., and J.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yuan Gao, National Key Laboratory of Veterinary Public Health and Safety, College of Veterinary Medicine, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China; Technology Innovation Center for Food Safety Surveillance and Detection (Hainan), Sanya Institute of China Agricultural University, Sanya 572025, China.

Ning Xie, National Key Laboratory of Veterinary Public Health and Safety, College of Veterinary Medicine, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China; Technology Innovation Center for Food Safety Surveillance and Detection (Hainan), Sanya Institute of China Agricultural University, Sanya 572025, China.

Tengfei Ma, National Key Laboratory of Veterinary Public Health and Safety, College of Veterinary Medicine, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China; Institute of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine, Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Jinan 250100, China.

Chun E Tan, National Key Laboratory of Veterinary Public Health and Safety, College of Veterinary Medicine, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China; Technology Innovation Center for Food Safety Surveillance and Detection (Hainan), Sanya Institute of China Agricultural University, Sanya 572025, China.

Zhuo Wang, National Key Laboratory of Veterinary Public Health and Safety, College of Veterinary Medicine, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China; Technology Innovation Center for Food Safety Surveillance and Detection (Hainan), Sanya Institute of China Agricultural University, Sanya 572025, China.

Rong Zhang, Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, China.

Shizhen Ma, National Key Laboratory of Veterinary Public Health and Safety, College of Veterinary Medicine, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China; Technology Innovation Center for Food Safety Surveillance and Detection (Hainan), Sanya Institute of China Agricultural University, Sanya 572025, China.

Zhaoju Deng, Technology Innovation Center for Food Safety Surveillance and Detection (Hainan), Sanya Institute of China Agricultural University, Sanya 572025, China; Large Animal Clinical Veterinary Research Center, College of Clinical Medicine, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China.

Yang Wang, National Key Laboratory of Veterinary Public Health and Safety, College of Veterinary Medicine, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China; Technology Innovation Center for Food Safety Surveillance and Detection (Hainan), Sanya Institute of China Agricultural University, Sanya 572025, China.

Jianzhong Shen, National Key Laboratory of Veterinary Public Health and Safety, College of Veterinary Medicine, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China; Technology Innovation Center for Food Safety Surveillance and Detection (Hainan), Sanya Institute of China Agricultural University, Sanya 572025, China.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at NAR online.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1800400 to W.Y.) and National Nature Science Foundation of China (32141002 to S.J.Z., 32202863 to M.S.Z.).

Data availability

The RNA-seq and ChIP-seq raw data have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. (GSA: CRA019670 and CRA019673 for RNA-seq and ChIP-seq)

The ChIP-seq data can be visualized on UCSC genome browser at https://genome-asia.ucsc.edu/s/Yuan%20Gao/3Rplasmid4 and https://genome-asia.ucsc.edu/s/Yuan%20Gao/BW25113.

The annotated sequence of p3R-4, pQD419, and p19SC11DZ17RtetX4 have been deposited in the Figshare database at https://figshare.com/s/811c43dd17f128e11a75.

References

- 1. Bonomo RA, Burd EM, Conly J et al. Carbapenemase-producing organisms: a global scourge. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2018; 66:1135–48. 10.1093/cid/cix893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rahman MK, Rodriguez-Mori H, Loneragan G et al. One health distribution of beta-lactamases in enterobacterales in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2024; 65:107422. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2024.107422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fu B, Xu J, Yin D et al. Transmission of blaNDM in Enterobacteriaceae among animals, food and human. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024; 13:2337678. 10.1080/22221751.2024.2337678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG et al. Characterization of a new metallo-beta-lactamase gene, blaNDM-1, and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009; 53:5046–54. 10.1128/AAC.00774-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ma J, Song X, Li M et al. Global spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: epidemiological features, resistance mechanisms, detection and therapy. Microbiol Res. 2023; 266:127249. 10.1016/j.micres.2022.127249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xia C, Yan R, Liu C et al. Epidemiological and genomic characteristics of global blaNDM-carrying Escherichia coli. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2024; 23:58. 10.1186/s12941-024-00719-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dong H, Li Y, Cheng J et al. Genomic epidemiology insights on NDM-producing pathogens revealed the pivotal role of plasmids on blaNDM transmission. Microbiol Spectr. 2022; 10:e0215621. 10.1128/spectrum.02156-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Qin J, Wang Z, Xu H et al. IncX3 plasmid-mediated spread of blaNDM gene in Enterobacteriaceae among children in China. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2024; 37:199–207. 10.1016/j.jgar.2024.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guo X, Chen R, Wang Q et al. Global prevalence, characteristics, and future prospects of IncX3 plasmids: a review. Front Microbiol. 2022; 13:979558. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.979558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li Y, Yang Y, Wang Y et al. Molecular characterization of blaNDM-harboring plasmids reveal its rapid adaptation and evolution in the Enterobacteriaceae. One Health Advances. 2023; 1:30. 10.1186/s44280-023-00033-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ma T, Fu J, Xie N et al. Fitness cost of blaNDM-5-carrying p3R-IncX3 plasmids in wild-type NDM-free Enterobacteriaceae. Microorganisms. 2020; 8:377. 10.3390/microorganisms8030377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lopatkin AJ, Meredith HR, Srimani JK et al. Persistence and reversal of plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance. Nat Commun. 2017; 8:1689. 10.1038/s41467-017-01532-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alonso-Del VA, Toribio-Celestino L, Quirant A et al. Antimicrobial resistance level and conjugation permissiveness shape plasmid distribution in clinical enterobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2023; 120:e1980832176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson TJ, Bielak EM, Fortini D et al. Expansion of the IncX plasmid family for improved identification and typing of novel plasmids in drug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Plasmid. 2012; 68:43–50. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cabezón E, Ripoll-Rozada J, Peña A et al. Towards an integrated model of bacterial conjugation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2015; 39:81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Costa T, Harb L, Khara P et al. Type IV secretion systems: advances in structure, function, and activation. Mol Microbiol. 2021; 115:436–52. 10.1111/mmi.14670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Christie PJ, Atmakuri K, Krishnamoorthy V et al. Biogenesis, architecture, and function of bacterial type IV secretion systems. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005; 59:451–85. 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peña A, Arechaga I Molecular motors in bacterial secretion. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013; 23:357–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koraimann G, Wagner MA Social behavior and decision making in bacterial conjugation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014; 4:54. 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Virolle C, Goldlust K, Djermoun S et al. Plasmid transfer by conjugation in gram-negative bacteria: from the cellular to the community level. Genes (Basel). 2020; 11:1239. 10.3390/genes11111239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Willetts N The transcriptional control of fertility in F-like plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1977; 112:141–8. 10.1016/S0022-2836(77)80161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dorman CJ H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat Rev Micro. 2004; 2:391–400. 10.1038/nrmicro883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Navarre WW, Porwollik S, Wang Y et al. Fang FC. Selective silencing of foreign DNA with low GC content by the H-NS protein in Salmonella. Science. 2006; 313:236–8. 10.1126/science.1128794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grainger DC Structure and function of bacterial H-NS protein. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016; 44:1561–9. 10.1042/BST20160190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shin M, Song M, Rhee JH et al. DNA looping-mediated repression by histone-like protein H-NS: specific requirement of Esigma70 as a cofactor for looping. Genes Dev. 2005; 19:2388–98. 10.1101/gad.1316305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shin M, Lagda AC, Lee JW et al. Gene silencing by H-NS from distal DNA site. Mol Microbiol. 2012; 86:707–19. 10.1111/mmi.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haycocks JR, Sharma P, Stringer AM et al. The molecular basis for control of ETEC enterotoxin expression in response to environment and host. PLoS Pathog. 2015; 11:e1004605. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dole S, Nagarajavel V, Schnetz K The histone-like nucleoid structuring protein H-NS represses the Escherichia coli bgl operon downstream of the promoter. Mol Microbiol. 2004; 52:589–600. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dorman CJ H-NS, the genome sentinel. Nat Rev Micro. 2007; 5:157–61. 10.1038/nrmicro1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Doyle M, Fookes M, Ivens A et al. An H-NS-like stealth protein aids horizontal DNA transmission in bacteria. Science. 2007; 315:251–2. 10.1126/science.1137550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dillon SC, Cameron AD, Hokamp K et al. Genome-wide analysis of the H-NS and sfh regulatory networks in Salmonella Typhimurium identifies a plasmid-encoded transcription silencing mechanism. Mol Microbiol. 2010; 76:1250–65. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lang KS, Johnson TJ Characterization of Acr2, an H-NS-like protein encoded on A/C2-type plasmids. Plasmid. 2016; 87-88:17–27. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu B, Shui L, Zhou K et al. Impact of plasmid-encoded H-NS-like protein on blaNDM-1-bearing IncX3 plasmid in Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 2020; 221:S229–36. 10.1093/infdis/jiz567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baomo L, Lili S, Moran RA et al. Temperature-regulated IncX3 plasmid characteristics and the role of plasmid-encoded H-NS in thermoregulation. Front Microbiol. 2021; 12:765492. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.765492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chaparian RR, Tran M, Miller CL et al. Global H-NS counter-silencing by LuxR activates quorum sensing gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 48:171–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hustmyer CM, Wolfe MB, Welch RA et al. RfaH counter-silences inhibition of transcript elongation by H-NS-StpA nucleoprotein filaments in pathogenic Escherichia coli. mBio. 2022; 13:e0266222. 10.1128/mbio.02662-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jiang F, Yang Y, Mao Z et al. ArcA positively regulates the expression of virulence genes and contributes to virulence of porcine Shiga toxin-producing enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr. 2023; 11:e0152523. 10.1128/spectrum.01525-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lynch AS, Lin EC Transcriptional control mediated by the ArcA two-component response regulator protein of Escherichia coli: characterization of DNA binding at target promoters. J Bacteriol. 1996; 178:6238–49. 10.1128/jb.178.21.6238-6249.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Newman SL, Will WR, Libby SJ et al. The curli regulator CsgD mediates stationary phase counter-silencing of csgBA in Salmonella Typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2018; 108:101–14. 10.1111/mmi.13919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hall CP, Jadeja NB, Sebeck N et al. Characterization of MxiE- and H-NS-dependent expression of ipaH7.8, ospC1, yccE, and yfdF in Shigella flexneri. mSphere. 2022; 7:e0048522. 10.1128/msphere.00485-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ma T, Xie N, Gao Y et al. VirBR, a transcription regulator, promotes IncX3 plasmid transmission, and persistence of blaNDM-5 in zoonotic bacteria. Nat Commun. 2024; 15:5498. 10.1038/s41467-024-49800-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform. 2019; 20:1160–6. 10.1093/bib/bbx108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Robert X, Gouet P Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:W320–4. 10.1093/nar/gku316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000; 97:6640–5. 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011; 29:24–6. 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Choi J, Schmukler M, Groisman EA Degradation of gene silencer is essential for expression of foreign genes and bacterial colonization of the mammalian gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022; 119:e2084728177. 10.1073/pnas.2210239119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ma R, Liu Y, Gan J et al. Xenogeneic nucleoid-associated EnrR thwarts H-NS silencing of bacterial virulence with unique DNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022; 50:3777–98. 10.1093/nar/gkac180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Walker KA, Miner TA, Palacios M et al. A Klebsiella pneumoniae regulatory mutant has reduced capsule expression but retains hypermucoviscosity. mBio. 2019; 10:e00089-19. 10.1128/mBio.00089-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wickham H ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 2016; New York: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang Y, Zhang R, Li J et al. Comprehensive resistome analysis reveals the prevalence of NDM and MCR-1 in Chinese poultry production. Nat Microbiol. 2017; 2:16260. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yang J, Wang HH, Lu Y et al. A ProQ/FinO family protein involved in plasmid copy number control favours fitness of bacteria carrying mcr-1-bearing IncI2 plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:3981–96. 10.1093/nar/gkab149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011; 27:1009–10. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Avila P, Núñez B, de l et al. Plasmid R6K contains two functional oriTs which can assemble simultaneously in relaxosomes in vivo. J Mol Biol. 1996; 261:135–43. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sonden B, Uhlin BE Coordinated and differential expression of histone-like proteins in Escherichia coli: regulation and function of the H-NS analog StpA. EMBO J. 1996; 15:4970–80. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Uyar E, Kurokawa K, Yoshimura M et al. Differential binding profiles of StpA in wild-type and h-ns mutant cells: a comparative analysis of cooperative partners by chromatin immunoprecipitation-microarray analysis. J Bacteriol. 2009; 191:2388–91. 10.1128/JB.01594-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fitzgerald S, Kary SC, Alshabib EY et al. Redefining the H-NS protein family: a diversity of specialized core and accessory forms exhibit hierarchical transcriptional network integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 48:10184–98. 10.1093/nar/gkaa709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ueguchi C, Seto C, Suzuki T et al. Clarification of the dimerization domain and its functional significance for the Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS. J Mol Biol. 1997; 274:145–51. 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang A, Cordova M, Navarre WW Evolutionary and functional divergence of Sfx, a plasmid-encoded H-NS homolog, underlies the regulation of IncX plasmid conjugation. mBio. 2024; 16:e0208924. 10.1128/mbio.02089-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Frost LS, Koraimann G Regulation of bacterial conjugation: balancing opportunity with adversity. Future Microbiol. 2010; 5:1057–71. 10.2217/fmb.10.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yi L, Durand R, Grenier F et al. PixR, a novel activator of conjugative transfer of IncX4 resistance plasmids, mitigates the fitness cost of mcr-1 carriage in Escherichia coli. mBio. 2022; 13:e0320921. 10.1128/mbio.03209-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Guo CH, Chu MJ, Liu T et al. High prevalence and transmission of blaNDM-positive Escherichia coli between farmed ducks and slaughtered meats: an increasing threat to food safety. Int J Food Microbiol. 2024; 424:110850. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2024.110850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tian D, Wang B, Zhang H et al. Dissemination of the blaNDM-5 gene via IncX3-type plasmid among Enterobacteriaceae in children. mSphere. 2020; 5:e00699-19. 10.1128/mSphere.00699-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dahlberg C, Chao L Amelioration of the cost of conjugative plasmid carriage in Eschericha coli K12. Genetics. 2003; 165:1641–9. 10.1093/genetics/165.4.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ochman H, Lawrence JG, Groisman EA Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature. 2000; 405:299–304. 10.1038/35012500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Will WR, Navarre WW, Fang FC Integrated circuits: how transcriptional silencing and counter-silencing facilitate bacterial evolution. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015; 23:8–13. 10.1016/j.mib.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cai W, Tang F, Jiang L et al. Histone-like nucleoid structuring protein modulates the fitness of tet(X4)-bearing IncX1 plasmids in gram-negative bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2021; 12:763288. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.763288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Li B, Ni S, Liu Y et al. The histone-like nucleoid-structuring protein encoded by the plasmid pMBL6842 regulates both plasmid stability and host physiology of Pseudoalteromonas rubra SCSIO 6842. Microbiol Res. 2024; 286:127817. 10.1016/j.micres.2024.127817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lu J, Peng Y, Wan S et al. Cooperative function of TraJ and ArcA in regulating the F plasmid tra operon. J Bacteriol. 2019; 201:e00448-18. 10.1128/JB.00448-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Caramel A, Schnetz K Lac and lambda repressors relieve silencing of the Escherichia coli bgl promoter. Activation by alteration of a repressing nucleoprotein complex. J Mol Biol. 1998; 284:875–83. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Picker MA, Karney M, Gerson TM et al. Localized modulation of DNA supercoiling, triggered by the Shigella anti-silencer VirB, is sufficient to relieve H-NS-mediated silencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023; 51:3679–95. 10.1093/nar/gkad088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Liu B, Guo Y, Liu N et al. In silico evolution and comparative genomic analysis of IncX3 plasmids isolated from China over ten years. Front Microbiol. 2021; 12:725391. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.725391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. White CE, Winans SC Cell-cell communication in the plant pathogen agrobacterium tumefaciens. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007; 362:1135–48. 10.1098/rstb.2007.2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq and ChIP-seq raw data have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. (GSA: CRA019670 and CRA019673 for RNA-seq and ChIP-seq)

The ChIP-seq data can be visualized on UCSC genome browser at https://genome-asia.ucsc.edu/s/Yuan%20Gao/3Rplasmid4 and https://genome-asia.ucsc.edu/s/Yuan%20Gao/BW25113.

The annotated sequence of p3R-4, pQD419, and p19SC11DZ17RtetX4 have been deposited in the Figshare database at https://figshare.com/s/811c43dd17f128e11a75.