Abstract

Objective

To assess long-term tofacitinib efficacy and safety in patients with PsA with or without prior biologic DMARD (bDMARD) exposure.

Methods

Data were pooled post hoc from three phase 3 and one long-term extension (LTE) PsA studies and stratified by TNF inhibitor-inadequate responder (TNFi-IR) or bDMARD-naïve patient status at the phase 3 study baseline. Data were reported as all tofacitinib (patients receiving one or more tofacitinib doses) or average tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily (patients receiving an average total daily dose <15 and ≥15 mg, respectively). Drug survival to month 51, efficacy to month 42 and safety were assessed descriptively.

Results

A total of 408 TNFi-IR patients (including 29 TNFi-experienced with unknown IR status) and 562 bDMARD-naïve patients were included. At baseline, TNFi-IR patients were more likely to be ≥65 years old, have cardiovascular/venous thromboembolism risk and have longer disease duration vs bDMARD-naïve patients. Drug survival was numerically shorter in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients. Tofacitinib efficacy was generally sustained to month 42, regardless of prior bDMARD treatment. Minimal disease activity/ PsA Disease Activity Score ≤3.2/>75% Psoriasis Area and Severity Index improvement response rates were numerically lower in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients to month 42, but rates of achieving an HAQ Disability Index ≤0.5 and enthesitis/dactylitis resolution were similar. In TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients, treatment-emergent adverse event incidence rates were higher and serious adverse event, serious infection and herpes zoster incidence rates were numerically higher (CI overlapped).

Conclusion

These findings support long-term tofacitinib efficacy and safety in TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naïve patients. However, the benefit–risk profile appeared more favourable in bDMARD-naïve patients, likely due to differences in baseline characteristics and risk factors between subgroups.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01877668, NCT01882439, NCT03486457, NCT01976364

Keywords: biologic therapies, interventional studies, JAK inhibitors, psoriatic arthritis, tofacitinib

Key messages.

Efficacy was generally maintained long-term, with certain outcomes showing numerical differences between groups.

Treatment-emergent adverse events were more common in TNFi-IR patients, but safety data were limited by subgroup numbers.

Tofacitinib benefit–risk profile appeared more favourable in bDMARD-naïve vs TNFi-IR patients, aligning with existing literature.

Introduction

PsA is a complex inflammatory disease that affects up to 30% of patients with psoriasis and has heterogeneous manifestations, including peripheral and axial arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis and nail and skin psoriasis [1]. According to current treatment recommendations, conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) are typically recommended as a first-line treatment for active PsA, followed by biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs), which are usually TNF inhibitors (TNFis), although the recommended bDMARD can vary depending on the manifestations present [2–4]. For patients with PsA who have an inadequate response to a TNFi, switching to a different TNFi, bDMARD or Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor is recommended [2–4]. However, it has been reported in clinical trials and real-world studies that patients exposed to a TNFi may have an attenuated response [5–9], worse persistence [10] or worse safety outcomes [11] with subsequent treatments.

Tofacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor for the treatment of PsA. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily (BID) were demonstrated in two global phase 3 studies [12, 13], one phase 3 study in China [14] and a long-term extension (LTE) study [15] in patients with PsA who had an inadequate response to csDMARDs or TNFi. The long-term safety of tofacitinib was further assessed using data pooled from the global phase 3 studies and LTE study [16].

The two global phase 3 studies included different patient populations; one included patients with PsA who were csDMARD inadequate responders (csDMARD-IRs) and TNFi-naïve [previous use of non-TNFi bDMARDs allowed; OPAL Broaden (NCT01877668)] [12], while the second included patients who were TNFi-IR [OPAL Beyond (NCT01882439)] [13]. However, comparable tofacitinib efficacy results were observed across both studies at month 3 [17]. In this post hoc analysis of longitudinal data from phase 3 and LTE studies, we assessed the persistence (up to month 51), efficacy (up to month 42) and safety (throughout the studies) of tofacitinib in patients with PsA with and without prior bDMARD exposure [i.e. patients who were TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naïve (to exclude patients who received non-TNFi bDMARDs), respectively] to further understand the long-term benefit–risk profile of tofacitinib across these populations.

Methods

Patients and study design

This post hoc analysis included data from patients with PsA in three phase 3 studies [two global studies (OPAL Broaden and OPAL Beyond) and one study conducted in China (NCT03486457)] and one LTE study [OPAL Balance (NCT01976364); including a methotrexate withdrawal substudy (Fig. 1)]. Full details of each study, including inclusion/exclusion criteria, have been reported previously [12–15] and are briefly summarized in the supplementary material, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online.

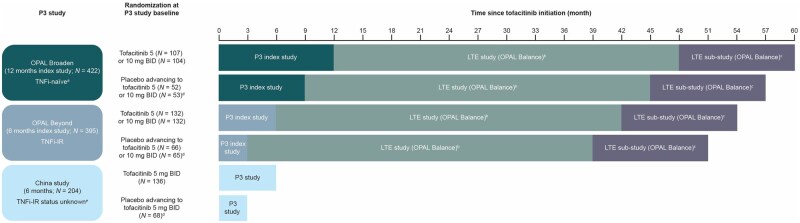

Figure 1.

Time since tofacitinib initiation in the different study populations that completed the qualifying studies and the China study. Patients included in this study were randomized to receive tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID or placebo advancing to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID at month 3 in the phase 3 index and China studies (tofacitinib 5 mg BID; placebo advancing to tofacitinib 5 mg BID only). Upon entry to OPAL Balance, all patients received open-label tofacitinib 5 mg BID. The tofacitinib dose could be increased to 10 mg BID for efficacy reasons after month 1 and reduced to 5 mg BID for safety reasons thereafter. Patients who had completed ≥24 months of the LTE study and had received stable-dose MTX for ≥4 weeks were eligible to enter a 12-month, randomized, double-blind, MTX withdrawal substudy in which patients received open-label tofacitinib plus either masked placebo or masked MTX. aOnly bDMARD-naïve patients from OPAL Broaden were included in this current study. bPatients could enter OPAL Balance ≤3 months after completing one of the qualifying index studies or discontinuing due to reasons other than a treatment-related AE. In total, 686 patients were enrolled in OPAL Balance. cPatients could enter the substudy if they had received tofacitinib for ≥24 months (stable at 5 mg BID for ≥3 months) and stable-dose oral MTX (7.5–20 mg/week) for ≥4 weeks. dAt month 3. ePatients were exposed to TNFi with unknown IR status and therefore were included in the TNFi-IR subgroup. P: phase

All studies were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation and were approved by the relevant institutional review board and/or independent ethics committee at each investigational site. A list of the 439 study sites is available on clinicaltrials.gov. Patients provided written informed consent.

Outcomes

All-cause drug survival, drug survival due to lack of efficacy and drug survival due to adverse events (AEs) were assessed up to month 51 of tofacitinib treatment. Drug survival (persistence) was defined as time from the first tofacitinib administration to the date of permanent treatment discontinuation, death or the end of the LTE study plus 1 day (whichever came first).

Efficacy was assessed up to month 42 of tofacitinib treatment and included the proportion of patients achieving minimal disease activity (MDA), PsA Disease Activity Score (PASDAS) ≤3.2 and improvement in the HAQ Disability Index (HAQ-DI) ≤0.5 (assessed in patients with a baseline HAQ-DI >0.5); the proportion of patients achieving ≥75% improvement in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI75) response (defined as ≥75% reduction from baseline in the PASI in patients with a baseline body surface area ≥3% and PASI >0); and the proportion of patients with resolved enthesitis [defined as patients with a baseline Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI) >0 who achieved LEI = 0] or resolved dactylitis [defined as patients with a baseline Dactylitis Severity Score (DSS) >0 who achieved DSS = 0]. The PASDAS was assessed at months 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 in the phase 3 index studies and every 6 months in the LTE study. In this analysis, due to the design of the phase 3 studies and the way the data were combined, assessment of the PASDAS in the LTE did not include all phase 3 treatment groups at every time point. PASDAS ≤3.2 rates at month 12 and every 6 months thereafter in this analysis predominantly included those patients randomized to tofacitinib in the phase 3 index studies (Fig. 1). Conversely, PASDAS ≤3.2 rates at month 15 and every 6 months thereafter in this analysis predominantly included those randomized to placebo who advanced to tofacitinib in the phase 3 studies (Fig. 1).

Safety outcomes included treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), all-cause deaths and AEs of special interest [serious infections, herpes zoster (serious and non-serious), adjudicated opportunistic infections, adjudicated malignancies excluding non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), adjudicated NMSC, adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), venous thromboembolism (VTE) events and hepatic events (based on Standardized Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Query)]. In addition, the timing of MACE and malignancies excluding NMSC were reported.

Post hoc analysis

Drug survival and the long-term efficacy of tofacitinib were analysed using data pooled from OPAL Broaden and OPAL Beyond (referred to as phase 3 index studies hereafter) and the LTE study (drug survival analyses included LTE substudy data). This included data from all patients randomized to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID and the tofacitinib exposure period of patients randomized to placebo advancing to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID in the phase 3 index studies, irrespective of their enrolment in the LTE study (Fig. 1). Patients receiving tofacitinib in both the qualifying and LTE studies were considered to have continuous treatment and baseline for these patients was defined as entry to the qualifying study. Patients with a gap of >14 days between the last qualifying study observation and first dose of tofacitinib in the LTE study were excluded. For patients receiving placebo in the qualifying study, baseline was defined as the first day of tofacitinib treatment. The entire tofacitinib treatment period was considered for each patient and repeated observations were assigned to a visit window (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online).

The long-term safety of tofacitinib was analysed using data pooled from the phase 3 index studies, the phase 3 study in China and the LTE study, which included all patients who received one or more doses of tofacitinib in the studies.

All analyses were conducted in the following cohorts: all tofacitinib, which included all patients who received one or more doses of tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID, and either average tofacitinib 5 mg BID or average tofacitinib 10 mg BID, which included patients with an average total daily dose from day 1 on tofacitinib of <15 mg or ≥15 mg, respectively.

Patients were stratified by their TNFi-IR or bDMARD-naïve status at the phase 3 study baseline. Patients who were exposed to TNFi with unknown IR status (i.e. patients could have discontinued due to safety, partial response or other reasons, including change of injection frequency or insurance plan, or were IR without prior documentation) were included in the TNFi-IR subgroup.

Statistical analysis

Demographics and disease characteristics at the phase 3 study baseline were reported descriptively by treatment cohort and prior bDMARD exposure.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of persistence (difference between the permanent discontinuation, death or end-of-study date and first tofacitinib dose date plus 1 day) were used to approximate drug survival (months), and analyses were performed within each treatment cohort using prior bDMARD exposure as strata. Patients who completed the LTE study were censored at the end-of-study date. Percentages and 95% CIs for TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naïve patients were presented for 1-, 2- and 3-year survival.

Efficacy analyses were based on as-observed data and non-responder imputation (NRI), where patients with missing values were considered as non-responders. Differences in response between TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naive patients were assessed by generalized linear models with repeated measures using logistic regression models for binary endpoints. Models were fitted using PROC GLIMMIX (with restricted pseudo-likelihood) in SAS version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). Independent variables for the model included treatment cohort, prior bDMARD exposure, sex, region and all-way interactions among prior bDMARD exposure, treatment cohort and visit. If the model failed to converge, simple statistics were presented instead.

Incidence rates for each safety outcome were defined as the number of patients with events per 100 patient-years. Events were counted up to 28 days beyond the last tofacitinib dose or to the data cut-off date. Gaps in tofacitinib dosing between treatment switches or between the phase 3 index and the LTE studies were included up to 28 days or to the data cut-off date. The 95% CIs for the incidence rates were based on the exact Poisson method and were adjusted for exposure time.

All analyses in this study were summarized descriptively with no formal hypothesis testing. Comparisons of tofacitinib survival and safety outcomes between TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naïve patients were described as higher or lower if 95% CIs did not overlap and numerically higher or lower if 95% CIs overlapped.

Results

Patients

Overall, 408 TNFi-IR patients (including 29 TNFi-exposed patients whose IR status was unknown due to lack of documentation) and 562 bDMARD-naïve patients from the global phase 3 index studies, the phase 3 study in China and the LTE study received one or more doses of tofacitinib and were included in the all-tofacitinib cohort. Of these, 220 TNFi-IR patients (including 28 TNFi-exposed patients with unknown IR status) and 428 bDMARD-naïve patients were included in the average tofacitinib 5 mg BID cohort and 188 TNF-IR patients (including 1 TNFi-exposed patient with unknown IR status) and 134 bDMARD-naïve patients were included in the average tofacitinib 10 mg BID cohort. Among patients included in the average tofacitinib 5 mg BID cohort, 28 (12.7%) TNFi-IR and 32 (7.5%) bDMARD-naïve patients increased their tofacitinib dose from 5 to 10 mg BID in the LTE study (mean duration of tofacitinib 10 mg BID treatment: TNFi-IR patients, 113.8 days; bDMARD-naïve patients, 208.8 days).

Patient demographics and disease characteristics at baseline of the three phase 3 studies are shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online. In all three cohorts, compared with the bDMARD-naïve patients, TNFi-IR patients were more likely to be ≥65 years of age or White, to have originated from the USA and Canada or Australia and Western Europe and to have a longer disease duration. The bDMARD-naïve patients were most commonly enrolled from Russia and Eastern Europe (Table 1). TNFi-IR patients were also more likely to have cardiovascular or VTE risk factors and to receive concomitant medications at baseline, including oral corticosteroids, statins and NSAIDs, compared with bDMARD-naïve patients (Table 1). Furthermore, at the phase 3 study baseline, the proportions of patients with enthesitis and the mean HAQ-DI score and C-reactive protein levels were higher in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients in all three cohorts (Table 1). Of note, herpes zoster vaccination status at baseline was not collected during the studies.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics at phase 3 baseline

| Characteristics | All tofacitinib |

Average tofacitinib 5 mg BID |

Average tofacitinib 10 mg BID |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNFi-IR (n = 408) | bDMARD-naïve (n = 562) | TNFi-IR (n = 220) | bDMARD-naïve (n = 428) | TNFi-IR (n = 188) | bDMARD-naïve (n = 134) | |

| Age, years, mean (s.d.) | 49.2 (12.2) | 47.0 (11.8) | 48.9 (12.1) | 47.4 (11.7) | 49.6 (12.3) | 45.7 (11.8) |

| Age ≥65 years, n (%) | 39 (9.6) | 43 (7.7) | 19 (8.6) | 33 (7.7) | 20 (10.6) | 10 (7.5) |

| Race, n (%)a | ||||||

| White | 349 (85.5) | 379 (67.4) | 179 (81.4) | 247 (57.7) | 170 (90.4) | 132 (98.5) |

| Black | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian | 41 (10.0) | 180 (32.0) | 31 (14.1) | 178 (41.6) | 10 (5.3) | 2 (1.5) |

| Other | 15 (3.7) | 3 (0.5) | 10 (4.5) | 3 (0.7) | 5 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Geographic location, n (%) | ||||||

| USA and Canada | 112 (27.5) | 45 (8.0) | 51 (23.2) | 23 (5.4) | 61 (32.4) | 22 (16.4) |

| Australia and Western Europe | 116 (28.4) | 56 (10.0) | 62 (28.2) | 34 (7.9) | 54 (28.7) | 22 (16.4) |

| Russia and Eastern Europe | 90 (22.1) | 270 (48.0) | 43 (19.5) | 184 (43.0) | 47 (25.0) | 86 (64.2) |

| Asia | 37 (9.1) | 176 (31.3) | 30 (13.6) | 176 (41.1) | 7 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Latin America | 53 (13.0) | 15 (2.7) | 34 (15.5) | 11 (2.6) | 19 (10.1) | 4 (3.0) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||

| Never smoked | 246 (60.3) | 365 (64.9) | 136 (61.8) | 281 (65.7) | 110 (58.5) | 84 (62.7) |

| Smoker | 66 (16.2) | 116 (20.6) | 42 (19.1) | 93 (21.7) | 24 (12.8) | 23 (17.2) |

| Ex-smoker | 96 (23.5) | 81 (14.4) | 42 (19.1) | 54 (12.6) | 54 (28.7) | 27 (20.1) |

| Presence of cardiovascular risk factors, n (%)b | 164 (40.2) | 162 (28.8) | 92 (41.8) | 128 (29.9) | 72 (38.3) | 34 (25.4) |

| Presence of VTE risk, n (%)c | 292 (71.6) | 290 (51.6) | 148 (67.3) | 208 (48.6) | 144 (76.6) | 82 (61.2) |

| Baseline (day 1) oral corticosteroid use, n (%) | 93 (22.8) | 78 (13.9) | 51 (23.2) | 58 (13.6) | 42 (22.3) | 20 (14.9) |

| Baseline (day 1) statin use, n (%) | 65 (15.9) | 36 (6.4) | 33 (15.0) | 26 (6.1) | 32 (17.0) | 10 (7.5) |

| Baseline (day 1) COX-2 use, n (%) | 33 (8.1) | 30 (5.3) | 14 (6.4) | 26 (6.1) | 19 (10.1) | 4 (3.0) |

| Baseline (day 1) NSAID use, n (%) | 213 (52.2) | 236 (42.0) | 112 (50.9) | 165 (38.6) | 101 (53.7) | 71 (53.0) |

| Baseline (day 1) MTX use, n (%) | 283 (69.4) | 341 (60.7) | 146 (66.4) | 228 (53.3) | 137 (72.9) | 113 (84.3) |

| MTX dose, mg/week, mean (s.d.) | 14.4 (4.4) | 15.6 (4.1) | 14.3 (4.3) | 15.6 (4.0) | 14.5 (4.5) | 15.6 (4.2) |

| Prior TNFi count, mean (s.d.) | 1.6 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1.5 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1.6 (0.9) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| PsA duration since diagnosis, years, mean (s.d.) | 8.9 (7.4) | 5.6 (6.4) | 8.8 (7.5) | 5.8 (6.8) | 9.1 (7.3) | 5.2 (4.9) |

| PsA duration ≥2 years, n (%) | 360 (88.2) | 353 (62.8) | 191 (86.8) | 261 (61.0) | 169 (89.9) | 92 (68.7) |

| PASDAS, mean (s.d.)d | 6.2 (1.2) | 6.0 (1.2) | 6.0 (1.2) | 6.0 (1.2) | 6.4 (1.3) | 6.0 (1.1) |

| PASDAS ≤3.2, n (%) | 2 (<1.0) | 8 (2.0) | 1 (<1.0) | 6 (2.3) | 1 (<1.0) | 2 (1.5) |

| PASDAS >3.2 to <5.4, n (%) | 94 (24.7) | 104 (26.5) | 57 (29.7) | 67 (26.0) | 37 (19.7) | 37 (27.6) |

| PASDAS ≥5.4, n (%) | 270 (71.1) | 274 (69.9) | 124 (64.6) | 180 (69.8) | 146 (77.7) | 94 (70.1) |

| HAQ-DI, mean (s.d.) | 1.2 (0.7) | 0.9 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.7) | 0.9 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.6) |

| HAQ-DI >0.5, n (%) | 329 (80.6) | 379 (67.4) | 169 (76.8) | 278 (65.0) | 160 (85.1) | 101 (75.4) |

| Presence of enthesitis (LEI >0), n (%) | 285 (69.9) | 336 (59.8) | 140 (63.6) | 250 (58.4) | 145 (77.1) | 86 (64.2) |

| LEI, mean (s.d.) | 3.0 (1.7) | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.3) | 3.5 (1.7) | 3.0 (1.5) |

| Presence of dactylitis (DSS >0), n (%) | 209 (51.2) | 323 (57.5) | 114 (51.8) | 251 (58.6) | 95 (50.5) | 72 (53.7) |

| DSS, mean (s.d.) | 8.1 (8.6) | 8.6 (8.0) | 7.2 (8.1) | 8.5 (8.1) | 9.3 (9.0) | 9.1 (7.3) |

| Presence of spondylitis, n (%)d,e | 71 (18.7) | 72 (18.4) | 33 (17.2) | 40 (15.5) | 38 (20.2) | 32 (23.9) |

| BASDAI, mean (s.d.)d | 6.7 (1.6) | 5.7 (2.3) | 6.3 (1.6) | 5.8 (2.5) | 7.0 (1.5) | 5.6 (2.2) |

| Body surface area ≥3%, n (%) | 253 (62.0) | 370 (65.8) | 141 (64.1) | 273 (63.8) | 112 (59.6) | 97 (72.4) |

| PASI (in patients with body surface area ≥3% and PASI >0), mean (s.d.) | 10.9 (9.5) | 9.9 (9.1) | 10.3 (9.6) | 9.7 (9.3) | 11.7 (9.3) | 10.3 (8.3) |

| CRP, mean (s.d.) | 13.4 (23.5) | 11.1 (17.8) | 12.7 (22.2) | 11.5 (18.0) | 14.3 (24.9) | 9.6 (17.4) |

COX-2: cyclooxygenase-2.

Race reported by the patient.

Any patient ≥50 years of age who met the following conditions: current smoker, high-density lipoprotein <40 mg/dl or presence of hypertension, diabetes, myocardial infarction or coronary heart disease.

Any patient who met the following criteria: age ≥60 years, BMI ≥30 kg/m2, smoking, day 1 antidepressant/aspirin/oral contraceptives or HRT use or previous heart failure/VTE (deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism).

Not available for the phase 3 study conducted in China.

Clinical diagnosis.

Drug survival in the phase 3 index studies and the LTE study

All-cause drug survival was shorter in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients in the all-tofacitinib cohort at 1 and 3 years and numerically shorter for the remaining data (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S1A, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online).

Figure 2.

Drug survival in phase 3 and LTE studies: all tofacitinib/average tofacitinib 5 mg BID. Month 0 (baseline) was the last non-missing assessment on or before day 1 of the first tofacitinib dose date for patients randomized to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID or placebo to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID in the phase 3 index studies. One TNFi-exposed patient with unknown IR status was included in the TNFi-IR group of the all-tofacitinib cohort. The most common reasons for discontinuation for TNFi-IR/bDMARD-naïve patients were AE(s) (all tofacitinib: 12.6%/12.6%; average tofacitinib 5 mg BID: 10.9%/13.7%), no longer willing to participate in the study (all tofacitinib: 10.5%/11.3%; average tofacitinib 5 mg BID: 8.9%/10.3%) and insufficient clinical response (all tofacitinib: 8.9%/2.6%; average tofacitinib 5 mg BID: 6.3%/1.5%). Tofa: tofacitinib

Although the differences were small, drug survival for patients who discontinued due to lack of efficacy was shorter in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients for all cohorts except for the 2- and 3-year tofacitinib survival rates for the average tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg BID cohorts, which were numerically shorter (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S1B, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online).

Drug survival for patients who discontinued due to AEs was similar between TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naïve patients except for the average tofacitinib 10 mg BID cohort, where the 2- and 3-year tofacitinib survival was numerically shorter in the TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. S1C, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online).

Efficacy in phase 3 index studies and LTE study

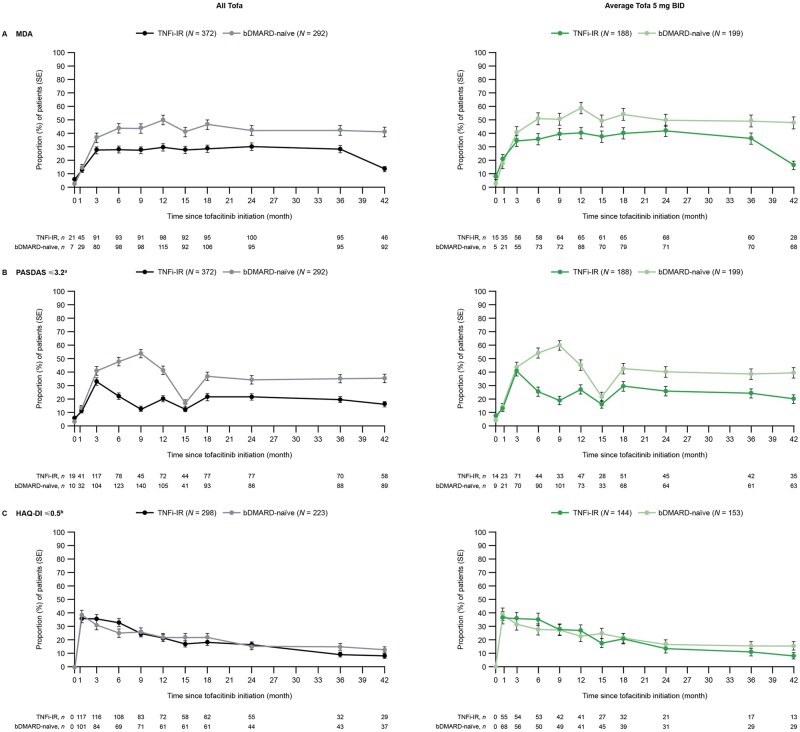

In the all-tofacitinib and average tofacitinib 5 mg BID cohorts, long-term efficacy was sustained regardless of prior bDMARD exposure for most outcomes up to month 42 based on the NRI analysis. However, the HAQ-DI ≤0.5 rate decreased over time at a similar rate in TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naïve patients (NRI analysis only; Figs 3 and 4). Similar observations were made for the average tofacitinib 10 mg BID cohort, although the rates for most efficacy outcomes were numerically lower than the all-tofacitinib and average tofacitinib 5 mg BID cohorts (Supplementary Figs S2 and S4, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online). The as-observed data are shown in Supplementary Figs S3 and S5, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online.

Figure 3.

Clinical efficacy in phase 3 and LTE studies: all tofacitinib/average tofacitinib 5 mg BID (NRI). Month 0 (baseline) was the last non-missing assessment on or before day 1 of the first tofacitinib dose date for patients randomized to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID or placebo to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID in the phase 3 index studies. One TNFi-exposed patient with unknown IR status was included in the TNFi-IR group of the all-tofacitinib cohort. aAssessed every 6 months in the LTE study. bAssessed in patients with baseline HAQ-DI >0.5. N: number of patients at baseline; n: number of patients who achieved the corresponding state; Tofa: tofacitinib

Figure 4.

PsA manifestations in phase 3 and LTE studies: all tofacitinib/average tofacitinib 5 mg BID (NRI). Month 0 (baseline) was the last non-missing assessment on or before day 1 of the first tofacitinib dose date for patients randomized to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID or placebo to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID in the phase 3 index studies. One TNFi-exposed patient with unknown IR status was included in the TNFi-IR group of the all-tofacitinib cohort. N: number of patients at baseline; n: number of patients with response; Tofa: tofacitinib

Up to month 42, the proportions of patients in all cohorts who achieved MDA, PASDAS ≤3.2 and PASI75 response were predominantly numerically lower in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients across most time points (NRI: Figs 3A, B, and 4A, Supplementary Figs S2A, B, and S4A, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online; as-observed: Supplementary Figs S3A, B, and S5A, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online). Reduced PASDAS ≤3.2 rates were observed at month 15 across patient and treatment groups (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. S2B, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online). A higher number of patients previously randomized to placebo who advanced to tofacitinib were evaluated at month 15. Overall, the proportion of patients who achieved HAQ-DI ≤0.5 and those with resolved enthesitis and dactylitis resolution were similar in TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naïve patients in both cohorts (NRI: Figs 3C, 4B, and 4C, Supplementary Figs S2C, S4B, C, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online; as-observed: Supplementary Figs S3C, S5B, C, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online).

Safety in phase 3 and LTE studies

Across cohorts, the incidence rates for TEAEs were higher in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients (Table 2). Furthermore, incidence rates for SAEs, serious infections and herpes zoster in all cohorts were numerically higher in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients (Table 2). Adjudicated opportunistic infections, adjudicated malignancies excluding NMSC, adjudicated NMSC, adjudicated MACE and hepatic events were observed in both TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naïve patients, and VTE events were observed in bDMARD-naïve patients. The number of events for each outcome was generally low (all ≤13; Table 2). Two deaths were reported in the all-tofacitinib cohort and two in the average tofacitinib 5 mg BID cohort. The timing of MACE and malignancies excluding NMSC during tofacitinib treatment are shown in Supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online.

Table 2.

Safety in phase 3 and LTE studies

|

n (%) Incidence rate (95% CI) |

All tofacitinib |

Average tofacitinib 5 mg BID |

Average tofacitinib 10 mg BID |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNFi-IRa (N = 408), 899 PY | bDMARD-naïveb (N = 562), 1255 PY | TNFi-IRc (N = 220), 490 PY | bDMARD-naïved (N = 428), 877 PY | TNFi-IRe (N = 188), 409 PY | bDMARD-naïvef (N = 134), 378 PY | |

| TEAE, n (%) | 373 (91.4) | 457 (81.3) | 199 (90.5) | 342 (79.9) | 174 (92.6) | 115 (85.8) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 181.81 (163.82, 201.23) | 117.83 (107.27, 129.14) | 164.85 (142.74, 189.42) | 121.06 (108.57, 134.60) | 206.05 (176.57, 239.04) | 109.16 (90.12, 131.03) |

| SAE, n (%) | 67 (16.4) | 71 (12.6) | 34 (15.5) | 51 (11.9) | 33 (17.6) | 20 (14.9) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 8.23 (6.38, 10.45) | 6.03 (4.71, 7.60) | 7.57 (5.24, 10.57) | 6.16 (4.58, 8.09) | 9.05 (6.23, 12.71) | 5.72 (3.49, 8.83) |

| All-cause death, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 0.11 (0.00, 0.62) | 0.08 (0.00, 0.44) | 0.20 (0.01, 1.14) | 0.11 (0.00, 0.64) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.90) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.98) |

| Serious infections, n (%) | 13 (3.2) | 11 (2.0) | 7 (3.2) | 9 (2.1) | 6 (3.2) | 2 (1.5) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 1.45 (0.77, 2.48) | 0.88 (0.44, 1.57) | 1.43 (0.58, 2.95) | 1.03 (0.47, 1.95) | 1.48 (0.54, 3.21) | 0.53 (0.06, 1.91) |

| Herpes zoster (serious and non-serious), n (%) | 19 (4.7) | 19 (3.4) | 10 (4.5) | 13 (3.0) | 9 (4.8) | 6 (4.5) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 2.18 (1.31, 3.40) | 1.55 (0.93, 2.42) | 2.10 (1.01, 3.86) | 1.52 (0.81, 2.60) | 2.27 (1.04, 4.30) | 1.61 (0.59, 3.51) |

| Adjudicated opportunistic infections, n (%) | 4 (1.0) | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (1.6) | 2 (1.5) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 0.45 (0.12, 1.15) | 0.24 (0.05, 0.70) | 0.21 (0.01, 1.14) | 0.11 (0.00, 0.64) | 0.74 (0.15, 2.16) | 0.53 (0.06, 1.92) |

| Adjudicated malignancies excluding NMSC, n (%) | 3 (0.7) | 12 (2.1) | 2 (0.9) | 11 (2.6) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.7) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 0.33 (0.07, 0.98) | 0.96 (0.49, 1.67) | 0.41 (0.05, 1.47) | 1.26 (0.63, 2.25) | 0.24 (0.01, 1.36) | 0.26 (0.01, 1.48) |

| Adjudicated NMSC, n (%) | 7 (1.7) | 9 (1.6) | 5 (2.3) | 6 (1.4) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (2.2) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 0.79 (0.32, 1.63) | 0.72 (0.33, 1.37) | 1.04 (0.34, 2.43) | 0.69 (0.25, 1.50) | 0.49 (0.06, 1.78) | 0.80 (0.17, 2.35) |

| Adjudicated MACE, n (%) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.9) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 0.22 (0.03, 0.80) | 0.32 (0.09, 0.82) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.75) | 0.46 (0.12, 1.17) | 0.49 (0.06, 1.77) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.98) |

| VTE, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.41) | 0.16 (0.02, 0.58) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.75) | 0.11 (0.00, 0.64) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.90) | 0.26 (0.01, 1.48) |

| Hepatic events (SMQ), n (%) | 9 (2.2) | 13 (2.3) | 2 (0.9) | 11 (2.6) | 7 (3.7) | 2 (1.5) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 1.01 (0.46, 1.92) | 1.06 (0.56, 1.81) | 0.41 (0.05, 1.48) | 1.28 (0.64, 2.29) | 1.74 (0.70, 3.59) | 0.54 (0.07, 1.95) |

NMSC: non-melanoma skin cancer; PY: patient-years; SMQ: Standardized Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Query.

Median tofacitinib exposure 988 days (range 1–1544).

Median tofacitinib exposure 744 days (range 1–1715).

Median tofacitinib exposure 1072 days (range 1–1544).

Median tofacitinib exposure 454 days (range 1–1715).

Median tofacitinib exposure 916 days (range 12–1526).

Median tofacitinib exposure 1058 days (range 26–1705).

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of data from phase 3 and LTE studies, the long-term efficacy and safety of tofacitinib were investigated in TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naïve patients with PsA. Here, bDMARD-naïve patients were evaluated as opposed to the TNFi-naïve population analysed in OPAL Broaden, which included some patients (11/422 patients at baseline) who had received non-TNFi bDMARDs. Efficacy was generally maintained long-term and response rates were numerically lower in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients except for HAQ-DI ≤0.5 rates and enthesitis and dactylitis resolution. Incidence rates for TEAEs in all phase 3 and LTE studies were higher in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients.

Up to month 51, all-cause drug survival and drug survival due to lack of efficacy were shorter or numerically shorter in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients across all treatment cohorts. These results were expected, given the known persistence disadvantage in treatment-refractory patients with PsA [6, 10, 11, 18]. Drug survival due to AEs was similar in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients except for the average tofacitinib 10 mg BID cohort, which was reassuring and might indicate that the AEs experienced in both patient subgroups did not often lead to discontinuation. However, there may be an underlying survival bias in this analysis due to the eligibility criteria for the LTE study, as patients could not enrol if they had discontinued the phase 3 index studies due to a TEAE. In addition, patients might be more likely to enrol in the LTE study if they had favourable responses to therapy in the phase 3 index studies. Overall, 363 (86.0%) and 323 (82.0%) patients who received treatment in OPAL Broaden and OPAL Beyond, respectively, were enrolled in the LTE study [19]. Furthermore, it should be acknowledged that ≈50% of TNFi-IR patients originated from the USA, Canada, Western Europe or Australia, while ≈80% of csDMARD-naïve patients originated from Russia, Eastern Europe or Asia. Clinical practices and availability of alternative PsA treatments may vary across geographic regions and therefore these differences might have subsequently influenced tofacitinib survival in the current analysis [20].

The findings reported herein were generally aligned with those from real-world studies of TNFis. In the US-based CorEvitas Registry, time to discontinuation with index TNFi was shorter in TNFi-experienced vs TNFi-naïve patients with PsA; the most common reasons for discontinuation or switching of the index TNFi to a new bDMARD in both TNFi-experienced and TNFi-naïve patients were lack of efficacy (73.2% and 90.2%, respectively) and side effects (26.8% and 12.2%, respectively) [11]. Similarly, in the Danish DANBIO study, drug survival with subsequent treatment decreased among patients who switched to a different TNFi or bDMARD [6]. Furthermore, an analysis of patients with PsA enrolled in the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register demonstrated that persistence with a second course of TNFi was lower than with a first course of TNFi, regardless of the reason for discontinuation [10].

When comparing endpoints between the OPAL Broaden (csDMARD-IR/TNFi-naïve patients) and OPAL Beyond (TNFi-IR patients) phase 3 trials in a prior pooled analysis, significant differences in responses with tofacitinib 5 mg BID vs placebo at month 3 were observed for PASI75 response rates only in csDMARD-IR/TNFi-naïve patients in OPAL Broaden and for enthesitis and dactylitis resolution rates only in TNFi-IR patients in OPAL Beyond [12, 13, 17]. In the current analysis, up to month 42 of tofacitinib treatment, PASI75 response rates were numerically lower in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients in all treatment cohorts, while the proportion of patients with resolved enthesitis and dactylitis were comparable. Several confounders might contribute to the differences in the impact of prior bDMARD exposure in tofacitinib response previously observed in the individual phase 3 index studies at month 3 vs the current analysis presented here, such as differences in patient populations (e.g. patients were analysed by average tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg BID in this analysis).

Attenuated responses to other advanced PsA treatments in patients previously exposed to TNFi have been reported. The efficacy of the IL-12/23 p40 inhibitor ustekinumab and IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab, including improvement in musculoskeletal and skin manifestations, was generally greater in TNFi-naïve vs TNFi-experienced patients [5, 8], which complements the results of the current analysis. In patients receiving the IL-23 p19 subunit inhibitor guselkumab, rates of achieving ≥20%/50% improvements in individual components of the American College of Rheumatology criteria and MDA components were similar in TNFi-naïve vs TNFi-experienced patients, with differences in several patient-reported outcomes [7]. Moreover, results of the DANBIO registry demonstrated that switching from a TNFi to another bDMARD was associated with lower effectiveness response rates [6]. Taken together, these findings suggest that patients with refractory disease may represent a patient population that is more difficult to treat.

In this post hoc analysis, incidence rates for TEAEs were higher, while SAEs, serious infections and herpes zoster were generally numerically higher in TNFi-IR patients compared with bDMARD-naïve patients in all cohorts. Data for herpes zoster vaccination were not available. TNFi-IR patients were more likely to be older, to have longer disease duration and cardiovascular or VTE risk and to receive oral corticosteroids, statins and NSAIDs than bDMARD-naïve patients at the phase 3 study baseline. Therefore, it is expected that this higher-risk patient population would be more likely to experience AEs. Similar findings have also been reported in patients with refractory RA receiving tofacitinib or baricitinib, where safety events were more likely to be observed in treatment-refractory patients [21, 22].

Studies assessing the impact of prior treatment on the safety profile of other advanced PsA treatments are limited. In a post hoc analysis of pooled data from phase 2 and 3 studies of patients with PsA receiving guselkumab, incidence rates of AEs up to 2 years in TNFi-experienced and TNFi-naïve patients were 174.0 (95% CI 160.9, 187.9) and 139.7 (95% CI 134.2, 145.3) events/100 patient-years, respectively; SAE, serious infection, gastrointestinal SAE, MACE and malignancy rates with guselkumab were similar regardless of prior TNFi exposure [23].

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the current findings. This was a post hoc analysis, and the number of some events in each patient subgroup was small. There were fewer patients in the average tofacitinib 10 mg BID groups vs 5 mg BID groups. Studies included in the analysis were not designed to assess long-latency safety events, which may have impacted the assessment of some AEs of special interest. The drug survival and efficacy analyses should be interpreted with caution due to the open-label design of the LTE study and the inherent survival bias present in the study, as discussed previously. Approximately 15% of the patients included in the index studies did not enter the LTE study, and data from these patients were imputed as non-responders. This may have affected the analysis, especially the results reported in the NRI analysis. Baseline (day 1) varied between patients depending on their enrolment in the phase 3 or LTE studies, and differences in the baseline demographics and characteristics discussed above between the TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naïve patients may have impacted the results. Furthermore, patients enrolled in these studies may not represent real-world patient populations and therefore these may be limited in terms of their generalizability.

Overall, in this post hoc analysis, the long-term efficacy and safety of tofacitinib were demonstrated in patients with PsA, regardless of TNFi-IR or bDMARD-naïve status. Drug survival was generally shorter in TNFi-IR vs bDMARD-naïve patients. Responses with tofacitinib were maintained over time, irrespective of prior bDMARD exposure, except for HAQ-DI ≤0.5 rates. These findings support the use of tofacitinib in TNFi-IR and bDMARD-naïve patients with PsA, although the benefit–risk profile appeared more favourable in bDMARD-naïve vs TNFi-IR patients, consistent with studies of other advanced PsA treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Justine Juana, CMC Connect, a division of IPG Health Medical Communications, and was funded by Pfizer (New York, NY, USA) in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines [Ann Intern Med 2022;175(9):1298–1304]. H.M.-O. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leeds Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, NIHR or UK Department of Health.

Contributor Information

Dafna D Gladman, Schroeder Arthritis Institute, Krembil Research Institute, Department of Medicine, Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Maxime Dougados, Department of Rheumatology, Hôpital Cochin, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, INSERM (U1153): Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, PRES Sorbonne Paris-Cité, Université de Paris Cité, Paris, France.

Helena Marzo-Ortega, NIHR Leeds Biomedical Research Centre, Leeds Teaching Hospital Trusts, Leeds Institute for Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

Mary Jane Cadatal, Pfizer Inc, Makati, Philippines.

Ekta Agarwal, Pfizer Inc, New York, NY, USA.

Cassandra D Kinch, Pfizer Canada ULC, Kirkland, QC, Canada.

Peter Nash, School of Medicine, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD, Australia.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online.

Data availability

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Authors’ contributions

C.K. was responsible for study conception and design. M.J.C. and P.N. were responsible for data acquisition. M.J.C., E.A. and C.K. were responsible for data analysis. All authors were responsible for data interpretation, review and editing of the manuscript and approval of the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer.

Disclosure statement: D.D.G. has acted as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB and has received grants and/or research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. M.D. has acted as a consultant for AbbVie, BMS, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and UCB and has received grants and/or research support from AbbVie, BMS, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. H.M.-O. has acted as a consultant for AbbVie, Biogen, Celgene, Lilly, Janssen, MoonLake, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda and UCB and has received grants and/or research support from Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. M.J.C. and E.A. are employees and stockholders of Pfizer. C.K. was an employee of Pfizer at the time of this study/analysis. P.N. has been a member of the speakers bureau for AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Lilly, Galapagos, GSK, Janssen, Novartis and Pfizer and has received grants and/or research support from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Lilly, Galapagos, GSK, Janssen, Novartis and Pfizer.

References

- 1. FitzGerald O, Ogdie A, Chandran V et al. Psoriatic arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021;7:59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:700–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh JA, Guyatt G, Ogdie A et al. Special article: 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:5–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coates LC, Soriano ER, Corp N et al. Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (GRAPPA): updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2021. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2022;18:465–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kavanaugh A, McInnes IB, Mease PJ et al. Efficacy of subcutaneous secukinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis stratified by prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use: results from the randomized placebo-controlled FUTURE 2 study. J Rheumatol 2016;43:1713–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glintborg B, Ostergaard M, Krogh NS et al. Clinical response, drug survival, and predictors thereof among 548 patients with psoriatic arthritis who switched tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor therapy: results from the Danish Nationwide DANBIO Registry. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:1213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ritchlin CT, Deodhar A, Boehncke W-H et al. Multidomain efficacy and safety of guselkumab through 1 year in patients with active psoriatic arthritis with and without prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitor experience: analysis of the phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled DISCOVER-1 study. ACR Open Rheumatol 2023;5:149–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Kavanaugh A et al. Efficacy and safety of the anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non-biological and biological anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6-month and 1-year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:990–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reddy SM, Crean S, Martin AL, Burns MD, Palmer JB. Real-world effectiveness of anti-TNF switching in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:2955–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saad AA, Ashcroft DM, Watson KD et al. Persistence with anti-tumour necrosis factor therapies in patients with psoriatic arthritis: observational study from the British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mease PJ, Karki C, Liu M et al. Discontinuation and switching patterns of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) in TNFi-naive and TNFi-experienced patients with psoriatic arthritis: an observational study from the US-based Corrona registry. RMD Open 2019;5:e000880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1537–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1525–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leng X, Lin W, Liu S et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in Chinese patients with active psoriatic arthritis: a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. RMD Open 2023;9:e002559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nash P, Coates LC, Fleishaker D et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib up to 48 months in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: final analysis of the OPAL Balance long-term extension study. Lancet Rheumatol 2021;3:e270–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burmester GR, Nash P, Sands BE et al. Adverse events of special interest in clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis and psoriasis with 37 066 patient-years of tofacitinib exposure. RMD Open 2021;7:e001595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nash P, Coates LC, Fleischmann R et al. Efficacy of tofacitinib for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. Rheumatol Ther 2018;5:567–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harrold LR, Stolshek BS, Rebello S et al. Impact of prior biologic use on persistence of treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis enrolled in the US Corrona registry. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nash P, Coates LC, Kivitz AJ et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: interim analysis of OPAL Balance, an open-label, long-term extension study. Rheumatol Ther 2020;7:553–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Michelsen B, Østergaard M, Nissen MJ et al. Differences and similarities between the EULAR/ASAS-EULAR and national recommendations for treatment of patients with psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis across Europe. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2023;33:100706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Genovese MC, Kremer JM, Kartman CE et al. Response to baricitinib based on prior biologic use in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:900–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tesser J, Gül A, Olech E et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response or intolerance to prior therapies. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69(Suppl 10):abstract 2493. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rahman P, Boehncke WH, Mease PJ et al. Safety of guselkumab with and without prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment: pooled results across 4 studies in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2023;50:769–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.