Abstract

Blockade of immune checkpoints, such as programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), has shown promise in cancer treatment; however, clinical response remains limited in many cancer types. Our previous research demonstrated that p300/CBP mediates the acetylation of the PD-L1 promoter, regulating PD-L1 expression. In this study, we further investigated the role of the p300/CBP bromodomain in regulating PD-L1 expression using CCS1477, a selective bromodomain inhibitor developed by our team. We found that the p300/CBP bromodomain is essential for H3K27 acetylation at PD-L1 enhancers. Inhibiting this modification significantly reduced enhancer activity and PD-L1 transcription, including exosomal PD-L1, which has been implicated as key contributors to resistance against PD-L1 blockade therapy in various cancers. Furthermore, CCS1477 treatment resulted in a marked reduction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in the tumor microenvironment (TME) by inhibiting key cytokines such as IL6, CSF1, and CSF2, which are crucial for MDSC differentiation and recruitment. By reducing PD-L1 expression and modulating the immunosuppressive TME, CCS1477 creates a more favorable environment for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, significantly enhancing the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy. Notably, these effects were observed in both prostate cancer and melanoma models, underscoring the broad therapeutic potential of p300/CBP bromodomain inhibition in improving ICB outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most prevalent non-cutaneous malignancy among males in the United States and ranks as the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality [1]. Initial treatment for localized PCa involves androgen deprivation therapy, but many patients eventually develop castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [2]. While second-generation androgen receptor (AR) antagonists like enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide provide a modest survival benefit, studies have shown that most patients receiving these agents ultimately progress to drug resistance and succumb to the disease [3]. Currently, there are no effective treatments available for AR antagonist-resistant CRPC, highlighting the urgent need for novel therapeutic agents or combination therapies.

Blockade of immune checkpoints, such as programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) or cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4), using therapeutic antibodies has shown promise in cancer therapy [4, 5]. However, the clinical response to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy remains limited in various cancer types, including metastatic PCa [6–8]. Research has shown that tumor cells release exosomes carrying PD-L1, which suppresses T-cell function and reduces the effectiveness of ICB therapies [9, 10]. In PCa specifically, PD-L1 is predominantly secreted via exosomes rather than presented on the cell surface, leading to immune evasion and resistance to PD-L1 blockade [11]. Strategies that target or eliminate exosomal PD-L1 have shown promise in overcoming this resistance and enhancing the therapeutic response to ICB. Additionally, the tumor microenvironment (TME) in PCa is enriched with myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), a subset of myeloid cells, which play a crucial role in shielding cancer cells from immune system attacks and contribute to resistance against ICB therapy [8, 12, 13]. The abundance of circulating MDSCs has been significantly correlated with PCa metastasis and overall survival [14]. And, targeting the myeloid compartment within the TME has emerged as a potential strategy to overcome resistance to ICB therapy in PCa [8].

p300/CBP, a coactivator of the androgen receptor involved in regulating its transcriptional program, has been implicated in recurrent PCa and therapy resistance [15]. It is reported that highly expressed p300 and its highly homologous histone acetyltransferase (HAT) CBP were implicated in progression of PCa, and that deletion of p300 in mice limited PCa progression and extended mice survival [16]. The oncogenic roles of p300 in the progression of PCa were usually related to the regulation of AR. p300 could directly acetylate AR or bind with AR to enhance AR transcriptional activity, consequently inducing the expression of oncogenes and promoting tumor growth [17, 18]. In addition to enhancing AR transcriptional activity, p300 could also regulate AR protein level by preventing its degradation [16]. However, the impact of p300/CBP on modifying the PCa TME and its role in ICB response has not been fully elucidated.

CCS1477, a novel and potent p300/CBP bromodomain (BD) inhibitor developed by our team, has demonstrated promising clinical responses in the treatment of metastatic PCa and hematologic malignancies [19, 20]. In biochemical assays, CCS1477 has demonstrated strong binding affinity to p300 and CBP. It exhibits a remarkable selectivity of 170-fold and 130-fold for p300 and CBP, respectively, compared to BRD4. Additionally, CCS1477 has been found to bind to cellular histones in an in-cell BRET assay, with an IC50 of 19 nmol/L for p300 and 1,060 nmol/L for BRD4. In a bromodomain screening assay involving 32 bromodomains, CCS1477 only showed minimal binding to BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, BRD9, and WDR9. Furthermore, CCS1477 displayed no inhibitory activity against 97 kinases and showed no adverse effects in a safety screen involving 44 receptors, enzymes, and ion channels at a high concentration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

CCS1477 was synthesized as described in International Patent Application Publication No. WO2018073586 [19]. For in vitro experiments, a 10 mmol/L stock solution of CCS1477 was prepared in DMSO (D2650, Sigma) and diluted in medium to achieve a final concentration with <0.1% DMSO. For in vivo studies, CCS1477 was formulated in a solution containing 5% DMSO and 0.5% methylcellulose (w/v) (HY-125861, MedChemExpress) and administered via oral gavage. Human and murine IFN-γ were obtained from PeproTech (NJ, USA). Anti-mouse PD-L1 (BE0101) and anti-mouse CTLA-4 (BE0164) antibodies used in vivo were from Bio X Cell (NH, USA).

Plasmids

The lentiCas9-Blast plasmid (Addgene #52962), gifted by Feng Zhang, was packaged into lentiviruses by co-transfecting with psPAX2 (Addgene #12260) and pCMV-VSV-G (Addgene #8454) into HEK293T cells. CBP and p300 sgRNAs were designed and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IA, USA).

Antibodies

For immunoblotting: Anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (E1L3N, 13684), anti-β-Actin mAb (4970), anti-Stat3 mAb (12640), anti-Phospho-Stat3 mAb (9145), anti-Phospho-Jak2 antibody (3771), anti-CBP mAb (7389), and the Acetyl-Histone H3 Antibody Sampler Kit (9927) were from Cell Signaling Technology (MA, USA). Anti-Jak2 mAb (sc-390539) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (TX, USA), anti-Vinculin antibody (V4505) was from Sigma (MA, USA), and anti-PD-L1 (mouse-specific) mAb (ab213480) was from Abcam (MA, USA). For flow cytometry: PE anti-human CD274 (B7-H1, PD-L1) antibody (329706), PE anti-mouse CD274 (B7-H1, PD-L1) antibody (124308), APC anti-mouse CD45 antibody (103112), FITC anti-mouse Gr-1 antibody, and PE/Cyanine5 anti-mouse CD4 antibody (100410) were obtained from BioLegend (CA, USA). Additionally, PE anti-mouse CD11b (12-0112-83), PE anti-mouse CD45 antibody (12-0451-82), and APC anti-mouse CD8 antibody (17-0081-82) were sourced from Thermo Fisher (MA, USA). For chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays: Anti-H3K27ac mAb (39685) and anti-p300 mAb (61401) were purchased from Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA).

Cell culture

DU145 (from ATCC) and PC-3 (a gift from Dr. Ka Wing Fong, University of Kentucky) cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich), while A375 (from ATCC), B16-F10 (from ATCC), SK-MEL-28 (a gift from Dr. Jinming Yang, University of Kentucky) and HEK293T cell (a gift from Dr. Andrea Kasinski, Purdue University) lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Sigma-Aldrich). All medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals, GA, USA), 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin. TRAMP-C2 (from ATCC) cells were cultured in DMEM containing 4 mM L-glutamine, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and 4.5 g/L glucose, supplemented with 0.005 mg/ml human insulin, 10 nM dehydroisoandrosterone, 5% FBS, and 5% Nu-Serum IV. All cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.

Mouse models and treatment

All animal experiments were conducted following the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky (KY, USA). The sample size for each group was calculated to achieve >85% power to detect a difference at a 5% significance level. Investigators were not blinded to group assignments. For tumor implantation, 2 × 106 TRAMP-C2 cells or 2 × 105 B16-F10 cells were subcutaneously injected into the flank of 6-week-old C57BL/6 J mice. Tumor growth was monitored every 3 days by measuring the tumor’s length and width. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: Tumor Volume = (Length × Width2) / 2. When tumor volume reached 100 mm3, mice were randomly assigned to groups and treated according to the strategy shown in Figs. 2A, 3A, 4E. Following treatment, mice were euthanized, and tumors were harvested for further analysis.

Fig. 2. CCS1477 decreases PCa PD-L1 expression in vivo.

A A schema showing the experiment design of in vivo TRAMP-C2 xenograft and treatment strategy. B–F TRAMP-C2 cells were injected into the flanks of C57BL/6 male mice. When the tumors reached 100 mm3, mice were treated with vehicle or different concentrations of CCS1477 (5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, or 20 mg/kg by oral gavage daily, 6 days on, and 1 day off for 28 days). Tumor volumes (B) were shown as mean ± SEM, tumor weight (C) and mice body (D) were determined and quantified after treatment. PD-L1 expression was determined by IB (E) or FACs (F). * represents p < 0.05, ** represents p < 0.01, *** represents p < 0.001.

Fig. 3. CCS1477 enhances PD-L1 blockade therapy in PCa.

A A schema showing the experiment design of in vivo TRAMP-C2 xenograft and treatment strategy. B–F TRAMP-C2 cells were injected into the flanks of C57BL/6 male mice. When the tumors reached 100 mm3, mice were treated with either vehicle or different concentrations of CCS1477 (2.5 mg/kg or 5 mg/kg, administered via oral gavage in a 3-days-on, 2-days-off regimen), 200 μg of anti-PD-L1 per mouse (every 5 days), or a sequential combination therapy (three days of CCS1477 treatment followed by a single dose of anti-PD-L1) for 45 days. Tumor volumes (B) were shown as mean ± SEM, tumor weight (C) were determined and quantified after treatment. CD4 + T cell population (D) or CD8 + T cell population (E) in tumor were determined by flow cytometry assay and quantified. Immunofluorescence (IF) staining of Ki-67 was performed to assess tumor cell proliferation, and quantification was conducted using ImageJ. Scale bar = 50 μm (F). * represents p < 0.05, ** represents p < 0.01, *** represents p < 0.001.

Fig. 4. CCS1477 enhances the efficacy of ICB therapy in melanoma.

A, B A375 melanoma cells were treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/mL), CCS1477 (1 μM), or their combination for 24 h. PD-L1 levels were assessed by IB (A) and FACS (B). C A375 cells were treated with 1 μM CCS1477 for 24 h, and exosomal PD-L1 levels were analyzed by IB. D ChIP-qPCR analysis of H3K27ac, p300, and histone H3 binding at the CD274 enhancer in A375 cells treated with DMSO or 1 μM CCS1477 for 24 h. E Schematic representation of the in vivo B16-F10 xenograft model and treatment strategy. F–K B16-F10 melanoma cells were injected into the flanks of C57BL/6 mice. Once tumors reached approximately 100 mm3, mice were treated with CCS1477 (5 mg/kg), anti-PD-L1 (200 μg per mouse), anti-CTLA4 (200 μg per mouse), or combination therapy with CCS1477 (three days of CCS1477 treatment followed by a single dose of anti-PD-L1 or anti-CTLA4) for 14 days. F PD-L1 expression was analyzed by flow cytometry. G Tumor volumes are presented as mean ± SEM. H Tumor weights were measured and quantified post-treatment. Intratumoral CD4⁺ (I) and CD8⁺ (J) T cell populations were analyzed by flow cytometry and quantified. K Immunofluorescence staining of Ki-67 was performed to assess tumor cell proliferation, and quantification was conducted using ImageJ. Scale bar = 50 μm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Flow cytometry

Cultured cells were detached using trypsin and washed twice with PBS. Tumor tissue samples were homogenized in PBS and washed twice with PBS. Cells were stained with Zombie Violet™ dye and the indicated antibodies for 30 min in PBS. After staining, cells were washed and fixed with 2.5% formaldehyde in PBS. Analysis of gene expression or cell populations was conducted using a BD LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences) or CytoFLEX (Beckman Coulter) flow cytometer, with data processed via FlowJo software.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP assays were conducted using the Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (#9005, Cell Signaling Technology) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were treated with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature to crosslink proteins to DNA. Cells were collected, nuclei were prepared, and chromatin was digested with Micrococcal Nuclease. The digested chromatin was then sonicated and incubated with specific antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by a 2-h incubation with ChIP-grade protein G magnetic beads at 4 °C. Chromatin was eluted, and cross-links were reversed. DNA was purified using spin columns and analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) with primers listed in Supplementary Table 1. Protein enrichment at genomic regions was calculated as a percentage of input DNA.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, 74104), following the manufacturer’s protocol, and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the Reverse Transcription Supermix (1708840, Bio-Rad). qPCR was conducted on a QuantStudio Digital PCR System (ThermoFisher) using SYBR Green mix (4913914001, Roche) with primers listed in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA sequencing and analysis

Total RNA was extracted from DU145 cells treated with DMSO or 1 μM CCS1477 for 24 hours using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, 74104). RNA sequencing was performed as paired-end reads of 150 bp with 30 million reads per sample on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (Novogene). Raw sequencing data were aligned to the human reference genome GRCh38 using HISAT2 (v2.1.0) [21]. Read counts were obtained using featureCounts from the subread package (v1.5.1) [22]. Differential gene expression analysis was conducted using the limma R package (v3.42.2) [23], with p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed using the Broad Institute’s publicly available software [24]. Ranked gene expression results were analyzed to identify enrichment of differential expression patterns using the Hallmarks database from MSigDB v7.4. The datasets of RNA-seq are available at NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), referring to GSE291279.

Exosome isolation

Exosome isolation was conducted as described previously [7]. Two days before exosome collection, culture medium was replaced with conditioned medium containing exosome-depleted FBS. After 48 h, the conditioned medium was collected and centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min, 2000 × g for 20 min, and 10,000 × g for 40 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris and larger particles. Exosomes were then pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 90 min at 4 °C. The exosome pellets were lysed in lysis buffer and analyzed by western blot.

AquaBluer assay for cell viability measurement

The AquaBluer assay was conducted as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were seeded at a density of 5000–10,000 cells per well in 96-well plates and incubated overnight. Following treatment, cells were incubated for an additional 72 h. AquaBluer™ reagent was diluted 1:100 in culture medium, the existing medium was removed, and 100 μL of the diluted AquaBluer™ solution was added to each well. Plates were incubated for 4 h, and fluorescence intensity was measured on a plate reader with 540 nm excitation and 590 nm emission.

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence Staining was performed as previously described [25]. Briefly, four-micron thick sections of optimal cutting temperature (O.C.T.)-embedded tumor tissue were prepared for immunofluorescence staining. The sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at 30 °C, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes, and blocked with 10% FBS/PBS (v/v) for 30 minutes. Next, the sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with an anti-Ki-67 antibody (#9129, Cell Signaling Technology), followed by incubation with a secondary antibody (#A-11034, ThermoFisher) for 1 h at room temperature. All antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 1% BSA and 1% normal goat serum. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst. Images were acquired using a Nikon confocal microscope.

ELISA assay

ELISA assays were performed using the IL-6 ELISA Kit (#KIT10395A), CSF1 ELISA Kit (#KIT11792), and CSF2 ELISA Kit (#KIT10015) from Sino Biological, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 100 μL of cultured cell medium was added to each well, the plate was covered, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, wells were incubated with the secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The liquid was then removed, and wells were washed three times. Substrate solution was added, and the plate was incubated for 20 min at room temperature, protected from light. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μL of stop solution to each well, followed by gentle mixing. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm within 10 min of adding the stop solution.

Statistical analysis

For comparisons between two independent groups, an unpaired t-test was conducted, with p-values and the standard error of the mean (SEM) reported. For comparisons among more than two groups, one-way ANOVA was performed, and p values along with SEM were provided. In all figures, statistical significance is indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

RESULTS

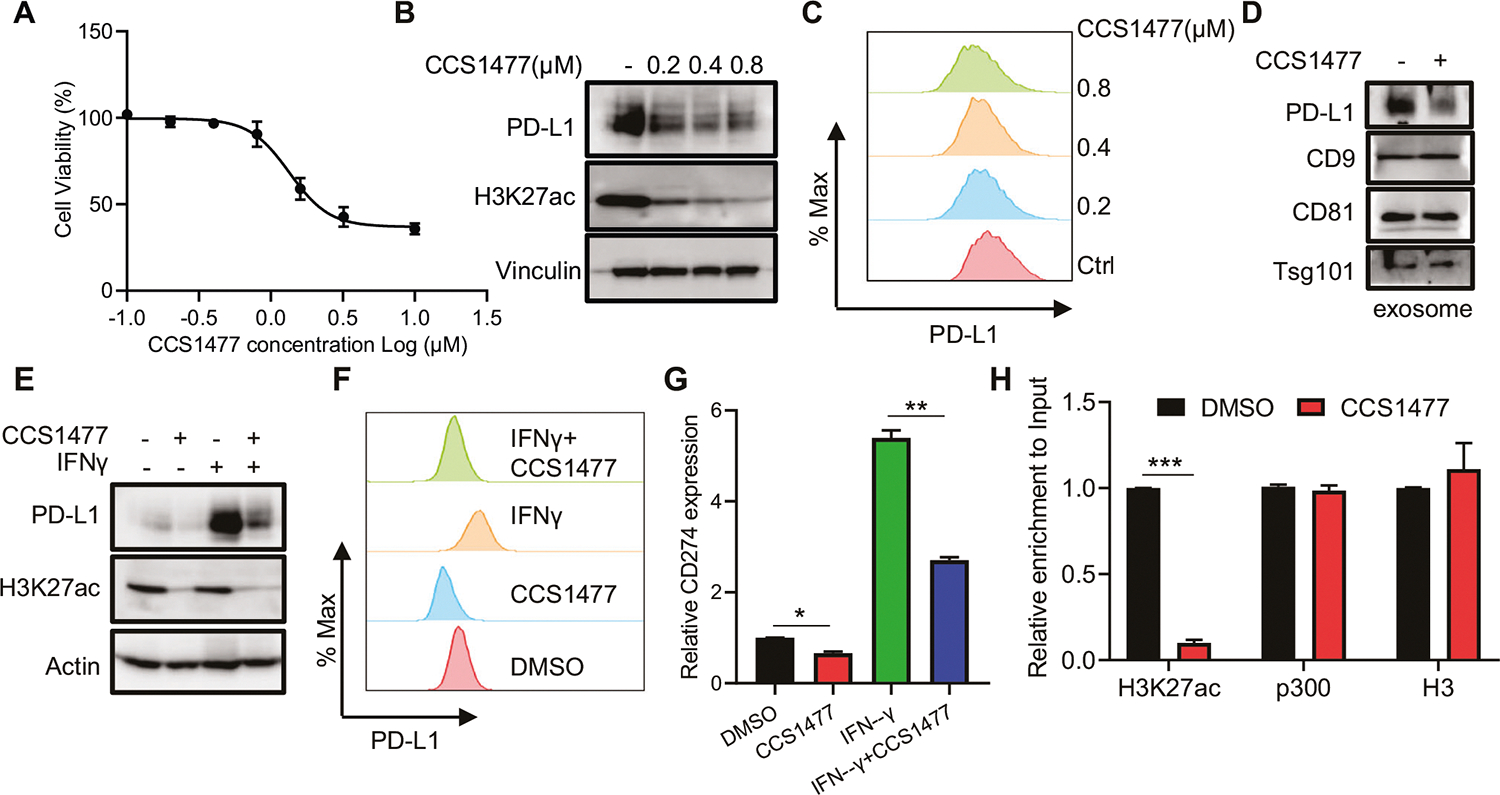

Targeting p300/CBP bromodomain decreases PD-L1 expression in prostate cancer in vitro and in vivo

Our prior research has demonstrated that p300/CBP acetyltransferase activity is important for the transcriptional expression of CD274 (encoding PD-L1) [7]. To explore the specific role of the p300/CBP bromodomain in PD-L1 expression, we employed CCS1477, a selective p300/CBP bromodomain inhibitor [19]. We treated prostate cancer (PCa) cells with CCS1477 at concentrations that do not significantly impair cell viability (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Figs. 1A and 1B). As indicated, CCS1477 markedly decreased PD-L1 expression levels in both human and mouse PCa cells (Fig. 1B, C; Supplementary Figs. 1C and 1D). Particularly, CCS1477 significantly reduced exosomal PD-L1 (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. 1E), which cannot be targeted by anti-PD-L1 antibody in the tumor environment and induced resistance to anti-PD-L1 blockade therapy [9, 10]. In addition to reducing basal PD-L1 expression, CCS1477 also suppressed IFN-γ-induced PD-L1 expression (Fig. 1E, F; Supplementary Figs. 1F and 1G). Consistent with our previous findings that p300 regulates PD-L1 transcription, CCS1477 treatment significantly decreased CD274/PD-L1 mRNA levels in PCa cells (Fig. 1G, Supplementary Fig. 1H), specifically reducing H3K27ac levels at the CD274 enhancer without affecting p300 occupancy (Fig. 1H).

Fig. 1. Targeting p300/CBP bromodomain decreases PCa PD-L1 expression in vitro.

A-C DU145 cells were treated with CCS1477 as indicated concentrations for 72 h and then subjected to AquaBluer assay to determine cell viability (A), or immunoblot (IB) (B) and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) (C) to determine PD-L1 level. D DU145 cells were treated with 1 μM CCS1477 for 24 h and then harvest medium for exosomal markers and PD-L1 determination with IB. E, F DU145 cells were treated with 10 ng/mL IFN-γ, 1 μM CCS1477 or combination for 24 h and then subjected to IB (E) or FACS (F) to determine PD-L1 level. G DU145 cells were treated with 10 ng/mL IFN-γ, 1 μM CCS1477 or combination for 24 h and then subjected to real-time q-PCR to determine the CD274 (PD-L1) expression. H ChIP-qPCR analysis of H3K27ac, p300 and H3 binding at CD274 enhancer in DU145 cells treated with DMSO or 1 μM CCS1477 for 24 h. * represents p < 0.05, ** represents p < 0.01, *** represents p < 0.001.

To confirm these in vitro findings, we investigated whether CCS1477 regulates PD-L1 expression in vivo. Mouse TRAMP-C2 cells were subcutaneously injected into mice, followed by CCS1477 treatment (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2B, CCS1477 limited tumor growth and reduced tumor burden (Fig. 2C) without significant adverse effects (Fig. 2D). Moreover, CCS1477 treatment significantly reduced PD-L1 expression, including both total PD-L1 levels (Fig. 2E) and cell surface PD-L1 (Fig. 2F). Notably, even a low dose of CCS1477 (5 mg/kg) led to a substantial suppression of PD-L1 expression, indicating a potent inhibitory effect at this concentration. This finding underscores the potential for effective PD-L1 modulation with lower CCS1477 exposure in vivo.

CCS1477 enhances the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) in prostate cancer

To determine whether p300/CBP inhibition by CCS1477 could enhance the efficacy of ICB therapy, TRAMP-C2 cells were injected subcutaneously into mice, followed by treatment with CCS1477, anti-PD-L1, or their combination (Fig. 3A). A low dose of CCS1477 (2.5 and 5 mg/kg) alone exhibited minimal anti-tumor activity. However, when combined with anti-PD-L1 therapy, CCS1477 significantly suppressed tumor cell proliferation and growth (Fig. 3B, F) and further reduced tumor burden (Fig. 3C), without causing notable adverse effects (Supplementary Fig. 2A). This combination therapy also led to a significant increase in tumor-infiltrating T-lymphocytes (Fig. 3D, E), highlighting an enhanced immune response.

CCS1477 enhances ICB therapy efficacy in melanoma

To extend the findings beyond prostate cancer, we tested the effects of CCS1477 in a melanoma model. CCS1477 was also effective in reducing PD-L1 expression in melanoma cells, including cellular (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. 3B), cell surface (Fig. 4B; Supplementary Fig. 3C), and particularly exosomal levels (Fig. 4C; Supplementary Fig. 3D). Furthermore, CCS1477 significantly reduced the enrichment of H3K27ac at the CD274 enhancer in melanoma cells (Fig. 4D). To evaluate the impact of CCS1477 on ICB therapy, B16-F10 melanoma mouse cell line were injected into mice, followed by treatment with CCS1477, anti-PD-L1, or their combination (Fig. 4E). Consistent with the prostate cancer model, CCS1477 reduced the expression of PD-L1 (Fig. 4F) and enhanced the anti-tumor efficacy of anti-PD-L1 therapy in melanoma (Fig. 4G). Moreover, we explored the combination of CCS1477 with another ICB therapy, anti-CTLA4, and found that CCS1477 significantly boosted the effectiveness of anti-CTLA4 as well (Fig. 4G). In both scenarios, the combination therapy resulted in a substantial reduction in tumor cell proliferation and tumor burden (Fig. 4H, K) and an increase in tumor-infiltrating T-lymphocytes (Fig. 4I, J), indicating a robust immune response.

CCS1477 reduces MDSCs in the tumor microenvironment (TME) via IL6/JAK pathway suppression

The presence of circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) is closely associated with cancer metastasis and reduced overall survival [26]. Targeting the myeloid cell compartment within the TME has emerged as a promising approach to overcome resistance to ICB therapy [8]. In mice bearing PCa or melanoma tumors, CCS1477 treatment led to a significant reduction in MDSC populations (CD11b⁺ and Gr1⁺) in both peripheral blood (PB) and the TME (Fig. 5), suggesting that CCS1477 may impact MDSC differentiation or recruitment, thereby enhancing ICB efficacy. RNA sequencing analysis revealed that p300/CBP inhibition by CCS1477 led to significant downregulation of the IL6/JAK pathway (Fig. 6A, B). This pathway, driven by factors like IL6, CSF1, and CSF2 released by cancer cells, is known to play a crucial role in MDSC differentiation and development [27–30]. CCS1477 treatment resulted in a substantial reduction of IL6, CSF1, and CSF2 levels in both prostate cancer (Fig. 6C) and melanoma models (Fig. 6F). To further validate the role of p300/CBP in regulating these cytokines, we performed double knockout (DKO) of p300 and CBP in PCa cells, which similarly led to a marked reduction in IL6, CSF1, and CSF2 expression (Fig. 6D, E). Consistent with these findings, CCS1477 treatment significantly reduced the secretion of IL6, CSF1, and CSF2 (Fig. 6G, H; Supplementary Figs. 4B, 4C) and suppressed downstream signaling, as indicated by decreased phosphorylation of Jak2 and Stat3 (Fig. 6I, J; Supplementary Fig. 4D and 4E). These findings underscore the potential of CCS1477 to modulate the TME by targeting IL6/JAK-regulated MDSC populations, ultimately enhancing immune-mediated anti-tumor responses.

Fig. 5. CCS1477 treatment reduces MDSCs population in tumor bearing mice.

A–D C57BL/6 mice bearing TRAMP-C2 xenografts were treated with vehicle or varying doses of CCS1477 via oral gavage for 45 days. The population of MDSCs (Gr1⁺CD11b⁺) was analyzed in peripheral blood (PB) (A, B) and the TME (C, D) using flow cytometry and quantified. E–H C57BL/6 mice bearing B16-F10 xenografts were treated with vehicle or CCS1477 (5 mg/kg) via oral gavage for 14 days. MDSC (Gr1⁺CD11b⁺) populations in PB (E, G) and TME (F, H) were assessed by flow cytometry and quantified. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Fig. 6. CCS1477 down-regulated IL6/JAK pathway.

A, B DU145 cells were treated with 1 μM CCS1477 for 24 h, and total RNA was extracted for RNA sequencing. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) indicated enrichment of the IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway in the CCS1477 treatment group (A). A heatmap was generated to display significantly altered genes within this pathway following CCS1477 treatment (B). C DU145 cells were treated with 1 μM CCS1477 for 24 h, and total RNA was harvested for qPCR analysis of the indicated genes. D, E DU145 cells with p300 and CBP depletion via CRISPR were analyzed. Two independent clones were selected and subjected to IB (D) or qPCR (E) to assess the expression of the indicated genes. F A375 cells were treated with 1 μM CCS1477 for 24 h, followed by qPCR analysis of the indicated genes. G, H DU145 (G) and A375 (H) cells were treated with 1 μM CCS1477 for 72 h, and the culture medium was analyzed using an ELISA assay to measure IL6, CSF1, and CSF2 secretion. IB analysis was performed on whole-cell lysates to confirm equal cell loading. I, J IB analysis of whole-cell lysates from DU145 (I) and A375 (J) cells treated with 0.5, 1, or 2 μM CCS1477 for 72 h. K Proposed working model. Tumor cells escape immune surveillance and resist ICB therapy by secreting exosomal PD-L1 and recruiting MDSCs into the TME. CCS1477 treatment reshapes the TME, creating a more supportive environment for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. By reducing PD-L1 expression and depleting MDSCs, CCS1477 enhances the efficacy of ICB therapy. Figure was created with BioRender. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Our previous research demonstrated that p300/CBP could be recruited to the PD-L1 promoter, leading to acetylation of Histone H3 at the CD274 promoter and inducing CD274 transcription [7]. In this study, we further explored the role of the p300/CBP bromodomain in regulating PD-L1 expression using CCS1477, a selective bromodomain inhibitor [19]. We showed that the p300/CBP bromodomain is critical for the acetylation of H3K27 at PD-L1 enhancers. Suppressing this modification significantly reduced enhancer activity and PD-L1 transcription, with a notable reduction in exosomal PD-L1, which is known to contribute to resistance to anti-PD-L1 therapies [9, 10]. These effects were observed not only in PCa models but also in melanoma models [10, 31], highlighting the broad therapeutic potential of p300/CBP bromodomain inhibition in enhancing immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy.

The selectivity of p300/CBP bromodomain inhibition offers distinct advantages compared to broader histone acetyltransferase (HAT) inhibition [19, 32]. Previous studies have reported that p300/CBP bromodomain inhibition selectively reduces acetylation of H3K27 at enhancers of genes directly involved in cancer growth, while HAT inhibition impacts broader epigenetic markers such as H3K18 and H3K27 [33]. These wider disruptions can potentially affect normal cellular functions. In contrast, CCS1477, as a bromodomain inhibitor, shows more precise targeting and better clinical potential, reducing the likelihood of off-target effects. Our findings align with these reports, as CCS1477 was well-tolerated in vivo, whether used as a monotherapy or in combination with ICB therapy, with no significant adverse effects observed during treatment. These results support the potential for CCS1477 to be developed as a safe and effective therapeutic agent for cancer treatment.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous population of immune-suppressive myeloid cells that accumulate in the tumor microenvironment (TME), where they inhibit T cell and natural killer (NK) cell function, promoting tumor growth [26]. MDSCs are known to contribute significantly to resistance to cancer treatments, especially immunotherapies like ICB. These cells suppress immune responses through multiple mechanisms, including direct inhibition of T and NK cells and stimulation of other immunosuppressive cell types, such as regulatory T (Treg) and B (Breg) cells [29]. Additionally, MDSCs enhance cancer progression by promoting immune evasion, facilitating metastasis, and supporting cancer cell survival [34]. High levels of MDSCs are associated with poor prognosis and resistance to immunotherapies across multiple cancer types [34, 35].

CCS1477 may help overcome resistance to ICB therapy by preventing immune evasion through multiple mechanisms. Our data suggest that inhibiting p300/CBP with CCS1477 leads to a significant reduction in MDSC abundance within the peripheral blood and the TME. This reduction likely preserves T cell function and enhances the response to ICB therapy. The inhibition of key cytokines such as IL6, CSF1, and CSF2, which play critical roles in MDSC differentiation and recruitment [13, 27, 29, 30, 36], further underscores the therapeutic potential of CCS1477. While IL6, CSF1, and CSF2 are important factors, it is likely that other cytokines and immune-modulating molecules regulated by p300/CBP also play roles in shaping the TME. Further investigations are needed to fully elucidate the breadth of p300/CBP’s regulatory functions within the TME.

Another important observation from our study is that CCS1477’s ability to enhance ICB therapy was not limited to prostate cancer but also extended to melanoma. This broader applicability highlights the potential of CCS1477 to be used in combination with ICB therapies across different tumor types. By targeting the p300/CBP bromodomain, CCS1477 not only reduces PD-L1 expression but also modulates the immunosuppressive TME, creating a more favorable environment for the activation and function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). This dual effect—directly reducing immune evasion and enhancing T cell infiltration—presents a powerful mechanism to boost the efficacy of ICB therapies, which currently face resistance in many cancers.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that targeting the p300/CBP bromodomain with CCS1477 represents a safe and promising strategy for enhancing ICB therapy in cancer. By reducing PD-L1 expression, particularly its exosomal variants, modulating the immune-suppressive TME, and diminishing the presence of MDSCs, CCS1477 could help overcome resistance to current immunotherapies. This approach holds promise for providing new treatment options for patients with advanced prostate cancer and potentially other solid tumors. Further clinical investigations are warranted to explore the full potential of CCS1477 in combination with ICB therapies across different cancer types, as well as its broader impact on the TME and immune responses.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-025-03417-w.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 CA256893 (XL), R01 CA264652 (XL), R01 CA157429 (XL), R01 CA272483 (XL). This research was supported by pilot funding (JL) provided by the Support from the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center’s Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA177558). The work was also supported by Biospecimen Procurement and Translational Pathology, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Flow Cytometry and Immune Monitoring Shared Resources of the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center (P30CA177558).

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

NB, NP, and KF are employees and shareholders of CellCentric Ltd. Additionally, Neil Pegg serves as a board director and is listed as the inventor on patents related to CCS1477.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

All procedures involving animals were carried out in compliance with institutional guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Kentucky (Protocol No.: 2020-3685). No human subjects were involved in this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data supporting the findings of this study are either included in the manuscript or available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swami U, McFarland TR, Nussenzveig R, Agarwal N. Advanced prostate cancer: treatment advances and future directions. Trends Cancer. 2020;6:702–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y, Zhou Q, Hankey W, Fang X, Yuan F. Second generation androgen receptor antagonists and challenges in prostate cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L, Han X. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy of human cancer: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3384–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma P, Pachynski RK, Narayan V, Flechon A, Gravis G, Galsky MD, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: preliminary analysis of patients in the CheckMate 650 trial. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:489–99.e483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, He D, Cheng L, Huang C, Zhang Y, Rao X, et al. p300/CBP inhibition enhances the efficacy of programmed death-ligand 1 blockade treatment in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2020;39:3939–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu X, Horner JW, Paul E, Shang X, Troncoso P, Deng P, et al. Effective combinatorial immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2017;543:728–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, Zhang HL, Sun X, et al. Exosomal PD-L1 and N-cadherin predict pulmonary metastasis progression for osteosarcoma patients. J Nanobiotechnol. 2020;18:151. 10.1186/s12951-020-00710-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen G, Huang AC, Zhang W, Zhang G, Wu M, Xu W, et al. Exosomal PD-L1 contributes to immunosuppression and is associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature. 2018;560:382–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poggio M, Hu T, Pai CC, Chu B, Belair CD, Chang A, et al. Suppression of exosomal PD-L1 induces systemic anti-tumor immunity and memory. Cell. 2019;177:414–27.e413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang G, Lu X, Dey P, Deng P, Wu CC, Jiang S, et al. Targeting YAP-dependent MDSC infiltration impairs tumor progression. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:80–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao D, Cai L, Lu X, Liang X, Li J, Chen P, et al. Chromatin regulator CHD1 remodels the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in PTEN-deficient. Prostate Cancer Cancer Discov. 2020;10:1374–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hossain DM, Pal SK, Moreira D, Duttagupta P, Zhang Q, Won H, et al. TLR9-Targeted STAT3 silencing abrogates immunosuppressive activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells from prostate cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3771–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin L, Garcia J, Chan E, de la Cruz C, Segal E, Merchant M, et al. Therapeutic targeting of the CBP/p300 bromodomain blocks the growth of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:5564–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong J, Ding L, Bohrer LR, Pan Y, Liu P, Zhang J, et al. p300 acetyltransferase regulates androgen receptor degradation and PTEN-deficient prostate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1870–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lasko LM, Jakob CG, Edalji RP, Qiu W, Montgomery D, Digiammarino EL, et al. Discovery of a selective catalytic p300/CBP inhibitor that targets lineage-specific tumours. Nature. 2017;550:128–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu M, Wang C, Reutens AT, Wang J, Angeletti RH, Siconolfi-Baez L, et al. p300 and p300/cAMP-response element-binding protein-associated factor acetylate the androgen receptor at sites governing hormone-dependent transactivation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20853–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welti J, Sharp A, Brooks N, Yuan W, McNair C, Chand SN, et al. Targeting the p300/CBP axis in lethal. Prostate Cancer Cancer Discov. 2021;11:1118–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicosia L, Spencer GJ, Brooks N, Amaral FMR, Basma NJ, Chadwick JA, et al. Therapeutic targeting of EP300/CBP by bromodomain inhibition in hematologic malignancies. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:2136–53.e2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Zhao Y, He D, Jones KM, Tang S, Allison DB, et al. A kinome-wide CRISPR screen identifies CK1alpha as a target to overcome enzalutamide resistance of prostate cancer. Cell Rep Med. 2023;4:101015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lasser SA, Ozbay Kurt FG, Arkhypov I, Utikal J, Umansky V. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2024;21:147–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber R, Groth C, Lasser S, Arkhypov I, Petrova V, Altevogt P, et al. IL-6 as a major regulator of MDSC activity and possible target for cancer immunotherapy. Cell Immunol. 2021;359:104254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neo SY, Tong L, Chong J, Liu Y, Jing X, Oliveira MMS, et al. Tumor-associated NK cells drive MDSC-mediated tumor immune tolerance through the IL-6/STAT3 axis. Sci Transl Med. 2024;16:eadi2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veglia F, Sanseviero E, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:485–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar A, Taghi Khani A, Sanchez Ortiz A, Swaminathan S. GM-CSF: A Double-Edged Sword in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:901277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cordonnier M, Nardin C, Chanteloup G, Derangere V, Algros MP, Arnould L, et al. Tracking the evolution of circulating exosomal-PD-L1 to monitor melanoma patients. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;9:1710899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebrahimi A, Sevinc K, Gurhan Sevinc G, Cribbs AP, Philpott M, Uyulur F, et al. Bromodomain inhibition of the coactivators CBP/EP300 facilitate cellular reprogramming. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15:519–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raisner R, Kharbanda S, Jin L, Jeng E, Chan E, Merchant M, et al. Enhancer activity requires CBP/P300 bromodomain-dependent histone H3K27 acetylation. Cell Rep. 2018;24:1722–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu J, Luo Y, Rao D, Wang T, Lei Z, Chen X, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer: therapeutic targets to overcome tumor immune evasion. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2024;13:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li K, Shi H, Zhang B, Ou X, Ma Q, Chen Y, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as immunosuppressive regulators and therapeutic targets in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lechner MG, Liebertz DJ, Epstein AL. Characterization of cytokine-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells from normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:2273–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are either included in the manuscript or available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.