Abstract

Background

The effects of high-volume exercise on coronary atherosclerosis remain controversial.

Objectives

The authors aimed to evaluate the impact of endurance exercise on coronary atherosclerosis assessed by cardiac computed tomography (CT) in athletes and nonathletes, and analyze differences based on sex.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Central for relevant studies from inception to September 2024, assessing the impact of different exercise volumes on subclinical coronary artery atherosclerosis assessed by coronary artery calcification (CAC) scoring or CT angiography (CCTA). The control group comprised nonathletes. The primary outcome was the difference in CAC scores between athletes and nonathletes and the secondary outcome was the differences in calcified plaque by CCTA. The analysis was stratified by sex and exercise volume assessed using metabolic equivalents of task (MET)-min/wk.

Results

Nine observational studies including 61,150 participants were included in the analysis. Male athletes with an exercise volume of >3,000 MET-min/wk showed higher mean CAC scores than nonathlete males (mean difference = 31.62; 95% CI: 10.66-52.58; P < 0.001), while no difference in CAC was found for male athletes with 1,500 to 3,000 MET-min/wk (P = 0.93) or female athletes with an exercise volume of 1,500 MET-min/wk or greater (P = 0.39 and P = 0.07). Our secondary endpoint showed significant sex-specific differences on the association of exercise volume and calcified plaque number and volume by CCTA.

Conclusions

Males with high-volume exercise training (>3,000 MET-min/wk) exhibited a higher burden of calcified plaque by CAC score than male nonathletes, while no such difference was observed in female athletes.

Key words: athletes, CAC, cardiovascular risks, coronary artery calcium, exercise, sex differences, subclinical atherosclerosis

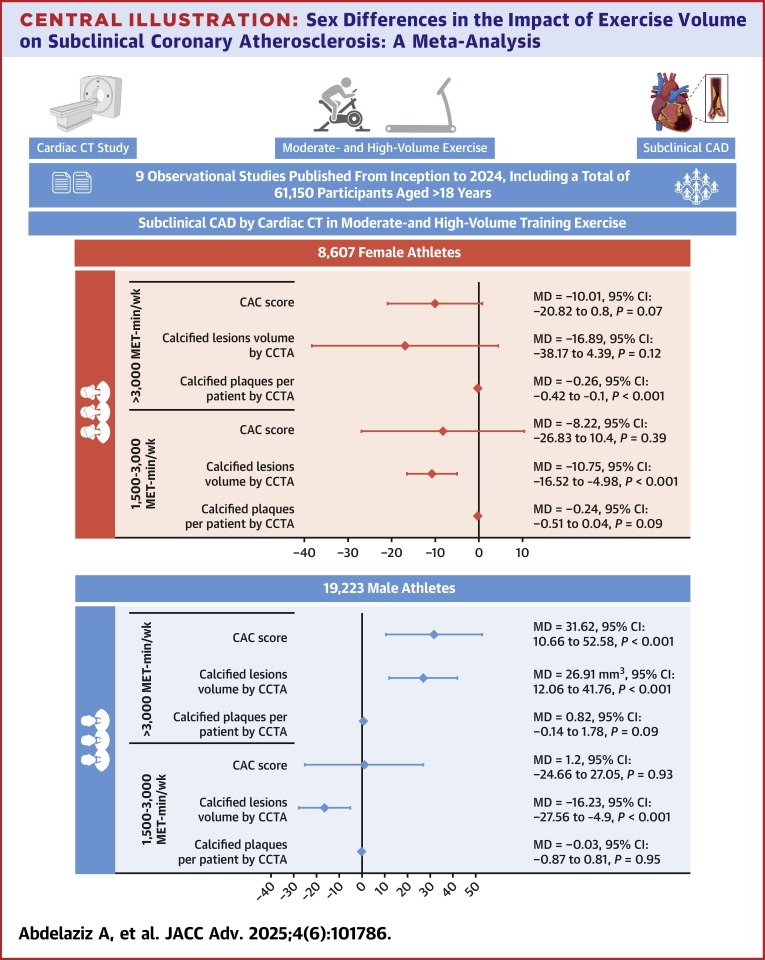

Central Illustration

Atherosclerosis and plaque formation are influenced by multiple factors, including sex, genetics, lifestyle, and exercise volume and duration. The relationship between endurance exercise and coronary atherosclerosis is a complex and highly debated topic in the scientific community.1 While regular physical activity (PA) is widely recognized for its cardiovascular (CV) benefits, including the reduction of risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, emerging evidence suggests that high-volume (>3,000 metabolic equivalents of task [MET]-min/wk) endurance training may paradoxically lead to a higher incidence of coronary atherosclerosis and plaque progression in athletes.2,3 This is particularly striking given that endurance athletes who engage in intensive PA over a long period are generally perceived to possess superior CV health compared to the general population.4 However, recent studies have highlighted that such athletes may be at an increased risk of developing CV disease (CVD) complications, which are typically associated with sedentary lifestyles and traditional CVD risk factors.5 This paradox raises important questions regarding the balance between the benefits and potential risks of extreme endurance exercise.6

Compelling evidence has underscored sex-specific differences in the incidence, underlying risk profiles, and clinical outcomes of CV disease.7 Notably, females appear to derive greater CV benefits from equivalent doses of PA compared to males,8 underscoring the importance of investigating study sex-specific responses to exercise in CV health. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) and coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring are the preferred methods for the quantification and detection of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis, with CAC scoring as the standard quantification method for CAC burden, while CCTA can also visualize both calcified and noncalcified plaques.9

In light of these uncertainties, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to synthesize current evidence on the relationship between endurance exercise and coronary atherosclerosis assessed as CAC using the Agatston score or the presence of plaques on CCTA, particularly focusing on the relationship between exercise volume, CVD risk factors, and coronary atherosclerosis, stratified by sex.

Methods

Data sources and searches

This meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline10 and registered in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) (CRD42024573617). We searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library from inception until September 2024 without any language restrictions, with the following search terms: (“Athletes” OR “Runners” OR “Marathon”) AND (“Coronary atherosclerosis” OR “Coronary plaque”). The search terms, based on the retrieved databases, are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Additional manual citation analysis was adopted to search for relevant articles from previous meta-analyses and those that were not shown in the search. Two authors independently conducted the literature search, screened the titles and abstracts, and selected the final included articles. Any disagreements during the selection process were resolved by discussion and consensus with a third author.

Study selection and outcomes

We included studies on asymptomatic individuals meeting the following inclusion criteria: 1) athletes engaged in high-volume training modalities such as running and cycling, with no prior history of coronary artery disease (CAD); 2) observational study design; 3) nonathletes who engaged in low-volume exercise and had no history of CAD; and 4) the outcome assessed in the study was subclinical coronary atherosclerosis assessed by CAC scoring or plaque evaluated by CCTA. Studies involving participants with preexisting symptomatic CVD or a history of CAD were excluded. Athletes were defined as per 2020 European Society of Cardiology guidelines as individuals who engage in regular exercise and competitive sporting events.11 We classified exercise volumes in athletes according to their METs relative to total exercise duration (min/wk) into 2 primary categories: 1) high volume of ≥3,000 MET-min/wk; and 2) moderate volume of 1,500 to 3,000 MET-min/wk.11,12 Nonathletes were defined as individuals with an exercise volume of <1,500 MET-min/wk, and no prior history of regular PA.11,12

The primary outcome was the CAC score assessed by a noncontrast dedicated CAC scan measured in Agatston units (AU), while the secondary outcomes were coronary plaque volume measured by CCTA,13 the volume of calcified plaques, and the mean number of plaques per patient assessed using CCTA. In addition, the degree of CAC (>0-10 AU, >11-100, >101-400, and >400 AU) was studied.14 The control group comprised nonathletes.

Quality assessment and data extraction

Data were extracted from the included studies using prespecified extraction forms. The data consisted of the baseline characteristics of the included patients, study characteristics, and the specified outcomes. Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies.15 The scale uses 3 main domains to assess the study quality: selection criteria, comparability testing, and outcome assessment. The risk of bias for each study was classified as good, poor, or fair. In the event of disagreement, the reviewers discussed the issues to reach consensus.

Statistical analysis

The pooled OR for dichotomous data using event and total for each outcome, and the mean difference (MD) for continuous data using the mean and SD for each outcome, with the corresponding 95% CIs, were calculated using a random effects model. The median (IQR) were converted to mean ± SD.16

Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochrane's Q test and an I2 value ≥50% with a P value of ≤0.10 was considered significant heterogeneity. Separate analyses of all studied outcomes according to sex were performed. Additionally, differences in outcomes were assessed based on 2 levels of exercise volumes: 1,500 to 3,000 MET-min/wk and ≥3,000 MET-min/wk. To evaluate publication bias, the LFK plots were visually reviewed using the DOI method.

Furthermore, sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding one study at a time (leave-one-out method) to investigate the influence of each study on the overall effect size estimate. We performed a random-effect meta-regression between mean age, baseline low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, body mass index (BMI), and CAC scores across male and female athletes and nonathletes. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA (StataCorp LLC) 18MP.17

Results

Search results and characteristics

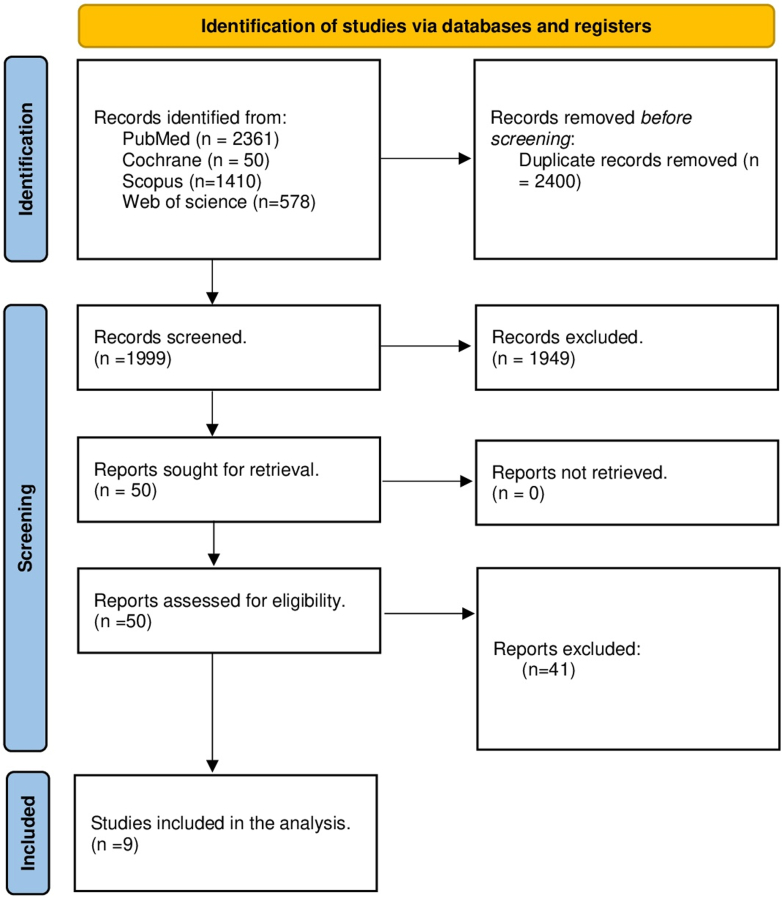

The initial literature search yielded 4,399 articles. Of these, 2,400 were duplicates and 1,999 citations were included in the title and abstract screening. The full texts of 50 articles were reviewed, and 9 studies were included in the final analysis18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram for Study Selection Process for Inclusion in the Meta-Analysis

PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis.

Due to the nature of the predefined criteria, only observational studies were included in this study. The studies were conducted in several countries: 5 in the United States, one in the Netherlands, one in Belgium, one in the United Kingdom, and one in Germany. The 9 studies included a total of 61,150 participants, with 27,830 athletes and 33,320 nonathletes. Among the athletes, 8,607 (30.92%) were female, while the nonathlete group included 9,532 (28.61%) females. None of the participants had an established history of CAD, and the median age across the studies was 55 years (range: 49-61 years). Detailed summary and baseline features of the included studies are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary Data of Included Studies

| First Author, Year | Study Arms | Site | Study Design | Medical History | Current and Former Smokers | Type of Sport | Cardiac Imaging Modality | Exposure Definition | Inclusion Criteria | Primary Endpoints | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aengevaeren, 2017 | <1,000 MET-min/wk, 88 (30.99) | Netherlands | Retrospective cohort study |

|

|

Competitive or recreational leisure sports | CCTA scan | Individuals perform 500-1,000 MET-min/wk of exercise |

|

CAC plaques prevalence | “Participants in the >2,000 MET-min/wk group had a higher prevalence of CAC and atherosclerotic plaques. The most active group, however, had a more benign composition of plaques, with fewer mixed plaques and more often only calcified plaques. These observations may explain the increased longevity typical of endurance athletes despite the presence of more coronary atherosclerotic plaque in the most active participants” |

| 1,000-2,000 MET-min/wk, 121 (42.61) |

|

|

Individuals perform 1,000-2,000 MET-min/wk of exercise | ||||||||

| <2,000 MET-min/wk, 75 (89.29) |

|

|

Individuals perform >2,000 MET-min/wk of exercise | ||||||||

| Bachman, 2020 | ≥3,000 MET-min/wk, 25 (58.14) | USA | Cross-sectional study | FH of CHD, 5 (20) | NR | Long-distance cycling races, ultramarathons, and Ironman triathlons | CCTA scan | Individuals who had a minimum of 10 y of cycling, running, swimming, or triathlon training and competed annually in ultraendurance events (races >6 h) such as long-distance cycling races, ultramarathons, and Ironman triathlons accounting ≥100 MET-h/wk |

|

|

“Our data indicate that middle-aged ultraendurance ATH do not have marked signs of widespread cardiovascular dysfunction or elevated CHD risk compared to controls meeting physical activity guidelines” |

| <1,500 MET-min/wk, 18 (41.86) | FH of CHD, 1 (6) | Jogging, walking, and recreational sports | Individuals who met current PA guidelines but were not engaged in structured endurance training accounting ≥10 MET-h/wk |

||||||||

| Bosscher, 2023 | Lifelong Ex, 191 (34.23) | Belgium | Prospective cohort study | FH of CHD, 12 (6.3) | None |

|

Dual-energy x-ray, cardiopulmonary exercise testing and CCTA scan | Athletes started regular endurance exercise training at <30 y |

|

Prevalence of coronary plaques | “Lifelong endurance sport participation is not associated with a more favorable coronary plaque composition compared to a healthy lifestyle. Lifelong endurance athletes had more coronary plaques, including more noncalcified plaques in proximal segments, than fit and healthy individuals with a similarly low cardiovascular risk profile. Longitudinal research is needed to reconcile these findings with the risk of cardiovascular events at the higher end of the endurance exercise spectrum” |

| Controls, 176 (31.54) | FH of CHD, 11 (6.3) |

|

Nonathletes engaged ≤3 h per week in physical activity without prior exposure to regular endurance exercise | ||||||||

| DeFina, 2019 | <1,500 MET-min/wk, 16,447 (75.59) | USA | Prospective cohort study | ND | Current, 2,457 (14.94) | Walking, jogging or running, treadmill, bicycling, stationary cycle, swimming, aerobic dance or floor exercise, and vigorous activity | Electron beam tomography scan using the C-150XP or C-300 system (GE Imatron) | Physical activity levels of <1,500 MET-min/wk |

|

|

“This study suggests there is evidence that high levels of physical activity (3,000 MET-min/wk) are associated with prevalent CAC but are not associated with increased all-cause or CVD mortality after a decade of follow-up, even in the presence of clinically significant CAC levels” |

| 1,500-2,999 MET-min/wk, 3,750 (17.24) | Current, 404 (10.77) | Physical activity levels of 1,500-2,999 MET-min/wk | |||||||||

| ≥3,000 MET-min/wk, 1,561 (7.17) | Current, 183 (11.72) | Physical activity levels of more than 3,000 MET-min/wk | |||||||||

| Merghani, 2017 | Athletes, 152 (62.3) | UK | Cross-sectional study | FH of CAD, 26 (17.1) | NR | Running and endurance events including marathons, half marathons, races and endurance cycling races | Transthoracic echocardiography, CCTA scan, and CMR scan | Master athletes were >40 y of age, ran ≥10 miles or cycled ≥30 miles per week and have continued to do so for ≥10 y, and competed in ≥10 endurance events, including marathons (26.2 miles, 42.2 km), half marathons (13.1 miles, 21.1 km), 10 km races, or endurance cycling races |

|

|

“Most lifelong masters endurance athletes with a low atherosclerotic risk profile have normal CAC scores. Male athletes are more likely to have a CAC score >300 Agatston units or coronary plaques compared with sedentary males with a similar risk profile. The significance of these observations is uncertain, but the predominantly calcific morphology of the plaques in athletes indicates potentially different pathophysiological mechanisms for plaque formation in athletic vs sedentary men. Coronary plaques are more abundant in athletes, whereas their stable nature could mitigate the risk of plaque rupture and acute myocardial infarction” |

| Controls, 92 (37.7) | FH of CAD, 24 (26.1) | Mainly walking, jogging, or swimming | Healthy controls engaged in exercise (mainly walking, jogging, or swimming) in accordance with the physical activity recommendations for health | ||||||||

| Mohlenkamp, 2008 | Marathon runners, 108 (9.09) | Germany | Prospective cohort study | HTN, 13 (12) |

|

Marathon | Electron-beam computed tomography (CCTA) and CMR | Marathon runners |

|

Prevalence of coronary plaques | “Conventional cardiovascular risk stratification underestimates the CAC burden in presumably healthy marathon runners. As CAC burden and frequent marathon running seem to correlate with subclinical myocardial damage, an increased awareness of a potentially higher than anticipated coronary risk is warranted” |

| Age-matched controls, 864 (72.73) |

|

|

NR | Healthy controls matched by age to marathon runners (8:1) | |||||||

| Age- and RFs-matched controls, 216 (18.18) | HTN, 61 (28.4) |

|

NR | Healthy controls matched by age and RFs to marathon runners (2:1) | |||||||

| Roberts, 2017 | Marathon runners, 26 (48.15) | USA | Retrospective cohort study |

|

Smoking Hx, 5 (20) | Marathons | Siemens Dual Source or FLASH CCTA with a minimum x-ray dose protocol | Women runners who had participated annually in the Twin Cities Marathon (Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN) for at least 10 consecutive y |

|

Prevalence of coronary plaques | “Women marathon runners had minimal coronary artery calcium counts, lower coronary artery plaque prevalence, and less calcified plaque volume compared with sedentary women. Developing coronary artery plaque in long-term women marathon runners appears related to older age and more cardiac risk factors, although the runners with coronary artery plaque had accumulated significantly more years running marathons” |

| Controls, 28 (51.85) |

|

Smoking Hx, 15 (56) | NR | Healthy matched controls for sedentary lifestyle and age | |||||||

| Schwartz, 2014 | Marathon runners, 50 (68.49) | USA | Retrospective cohort study |

|

Smoking Hx, 26 (52) | Marathons | Siemens Dual Source or FLASH CCTA in a minimum x-ray dose protocol |

Men in the study completed at least one marathon yearly for 25 consecutive years |

|

|

“Long-term male marathon runners may have paradoxically increased coronary artery plaque volume” |

| Controls, 23 (31.51) |

|

Smoking Hx, 9 (39.1) | NR | Derived from a contemporaneous CCTA database of asymptomatic healthy individuals | |||||||

| Pavlovic, 2024 | <1,500 MET-min/wk, 4,245 (18.15) | USA | Cross-sectional study | NR | Current smoker, 828 (19.5) | Walking, jogging, treadmill, bicycling, swimming, tennis, basketball, soccer, fitness class, water aerobics, boot camp, elliptical, rowing, jump rope, golf (without a cart), dance, stairs, hiking, and cross-country skiing | An electron beam tomography scan | Participants underwent 0 h of exercises weekly (mild physical activity intensity) |

|

Prevalence of coronary plaques | “Elevated CAC was associated with lower average volume and longer duration of PA in men, providing new insight into the complex relationship between leisure-time PA behaviors and risk of CAC” |

| 1,500-3,000 MET-min/wk, 9,115 (38.39) | Current smoker, 1,021 (11.2) | Participants underwent weekly 2 to <5 h of exercises (vigorous physical activity intensity) | |||||||||

| ≥3,000 MET-min/wk, 2,227 (9.52) | Current smoker, 269 (12.1) | Participants underwent weekly ≥5 h of exercises (super vigorous physical activity intensity) |

Values are n (%).

ATH = athletes; CAC score = coronary artery calcification score; CAD = coronary artery disease; CCTA = coronary computed tomography angiography; CHD = coronary heart disease; CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DM = diabetes mellitus; ECG = electrocardiogram; FH = family history; HLD = hyperlipidemia; HTN = hypertension; Hx = history; MET = metabolic equivalent of task; NR= not reported; PA = physical activity; PA = physical activity.

Table 2.

Baseline Data of Included Patients

| First Author, Year | Study Arms | Age, y | BMI, kg/m2 |

Male | Statins | Years of Exercise | Exercise Duration/wk, h | MET-Hours Per Week | Resting Heart Rate, beats/min | Systolic BP, mm Hg | Diastolic BP, mm Hg | Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | LDL Cholesterol, mg/dL | Hyperlipidemia Cholesterol, mg/dL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aengevaeren, 2017 | <1,000 MET-min/wk, 88 (30.99) | 54.4 ± 6.1 | 25.3 ± 2.9 | 88 (100) | 6 (7) | 25.67 ± 13.1 | 1.43 ± 0.75 | 10.43 ± 5.05 | NR | 128 ± 11 | 80 ± 8 | 207.27 ± 33.64 | NR | NR |

| 1,000-2,000 MET-min/wk, 121 (42.61) | 54.8 ± 6.3 | 24.8 ± 2.8 | 121 (100) | 2 (2) | 35.67 ± 8.25 | 3 ± 0.9 | 23.93 ± 6.08 | 130 ± 15 | 80 ± 9 | 205.34 ± 34.03 | ||||

| <2,000 MET-min/wk, 75 (89.29) | 55.9 ± 6.9 | 24.5 ± 2.3 | 75 (100) | 7 (9) | 40.67 ± 9.07 | 5.867 ± 2.041 | 47.467 ± 15.57 | 129 ± 12 | 80 ± 8 | 210.36 ± 37.12 | ||||

| Bachman, 2020 | ≥3,000 MET-min/wk, 25 (58.14) | 50 ± 1 | 21.6 ± 0.4 | 14 (56) | NR | 19 ± 2 | 11.5 ± 0.6 | 123 ± 7 | 46 ± 1 | 111 ± 2 | 76 ± 1 | 204.95 ± 7.734 | 119.877 ± 7.734 | 69.61 ± 3.867 |

| <1,500 MET-min/wk, 18 (41.86) | 49 ± 2 | 25.0 ± 0.9 | 9 (50) | NR | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 25 ± 3 | 53 ± 2 | 110 ± 2 | 75 ± 2 | 193.35 ± 7.734 | 100.542 ± 7.734 | 77.34 ± 3.867 | ||

| Bosscher, 2023 | Lifelong Ex, 191 (34.23) | 56 ± 7.47 | 23.23 ± 1.87 | 191 (100) | None | 36.33 ± 11.2 | 11.67 ± 2.99 | 87.83 ± 21.66 | 54 ± 7.47 | 122.33 ± 12.7 | 75 ± 7.47 | 192.67 ± 29.13 | 121.67 ± 25.4 | 64.33 ± 14.19 |

| Controls, 176 (31.54) | 55 ± 7.47 | 24.06 ± 2.24 | 176 (100) | 10.33 ± 19.4 | 1.33 ± 2.24 | 14.3445 ± 10.639 | 61.33 ± 11.96 | 123 ± 11.96 | 75.33 ± 7.47 | 194.33 ± 34.38 | 129.67 ± 31.39 | 57.67 ± 12.71 | ||

| DeFina, 2019 | <1,500 MET-min/wk, 16,447 (75.59) | 51.76 ± 8.45 | 28.25 ± 4.26 | 16,447 (100) | 2,936 (17.85) | 18.59 ± 13.82 | 1.74 ± 2.12 | 7.72 ± 7.83 | NR | 124.9 ± 14.28 | NR | 198.368 ± 37.68 | 122.72 ± 33 | 48.12 ± 12.375 |

| 1,500-2,999 MET-min/wk, 3,750 (17.24) |

51.167 ± 8.1 | 27.27 ± 3.57 | 3,750 (100) | 589 (15.71) | 23.52 ± 14.02 | 5.65 ± 2.84 | 34.67 ± 6.97 | 24.3 ± 14.13 | 195.65 ± 35.45 | 120.34 ± 31.23 | 51.867 ± 13.36 | |||

| ≥3,000 MET-min/wk, 1,561 (7.17) | 52.46 ± 8.56 | 27.1 ± 3.63 | 1,561 (100) | 245 (15.7) | 26.8 ± 14.55 | 12.13 ± 7.32 | 77.1 ± 39.43 | 124.64 ± 13.91 | 195.31 ± 35.79 | 119.59 ± 31.87 | 53.2 ± 13.7 | |||

| Merghani, 2017 | Athletes, 152 (62.3) | 54.4 ± 8.5 | NR | 106 (69.74) | NR | 31 ± 12.6 | 7.56 ± 3.54 | NR | NR | 125.65 ± 10.26 | 78.34 ± 7.63 | 175.56 ± 16.24 | 110.98 ± 14.31 | NR |

| Controls, 92 (37.7) | 53.43 ± 7.92 | 54 (35.53) | NR | 1.9 ± 0.34 | 123.58 ± 8.64 | 78.18 ± 6.9 | 171.69 ± 13.9 | 112.143 ± 11.52 | ||||||

| Mohlenkamp, 2008 | Marathon runners, 108 (9.09) | 57.2 ± 5.7 | 24.0 ± 2.3 | 108 (100) | NR | NR | NR | 78.1 ± 38.08 | 65 ± 10 | 121 ± 14 | NR | 227 ± 42 | 121 ± 29 | 73.8 ± 17.3 |

| Age and RFs matched controls, 216 (18.18) | 57.1 ± 5.6 | 24.9 ± 2.1 | 216 (100) | 29.13 ± 36.67 | 74 ± 11 | 127 ± 14 | 215 ± 32 | 131 ± 31 | 60.6 ± 14.7 | |||||

| Roberts, 2017 | Marathon runners, 26 (48.15) | 56 ± 10 | 22 ± 3 | 0 | NR | At least 10 | NR | NR | 57.1 ± 7.6 | 120 ± 13 | 78 ± 10 | 189.4 ± 31.9 | 103 ± 23 | 73 ± 15 |

| Controls, 28 (51.85) | 61 ± 10 | 32 ± 8 | 0 | NR | 72.2 ± 12.1 | 130 ± 21 | 75 ± 11 | 198.9 ± 32.3 | 119 ± 36 | 54 ± 16 | ||||

| Schwartz, 2014 | Marathon runners, 50 (68.49) | 59.44 ± 6.66 | 24.16 ± 2.88 | 50 (100) | NR | At least 25 | NR | NR | 52.36 ± 9.31 | 127.02 ± 13.74 | 79.04 ± 9.4 | 186.44 ± 28.83 | 111.90 ± 26.09 | 58.02 ± 11.58 |

| Controls, 23 (31.51) | 55.43 ± 10.39 | 30.29 ± 5.16 | 23 (100) | 70.83 ± 10.57 | 134.00 ± 18.35 | 79.3 ± 10.39 | 183.56 ± 48.59 | 108.13 ± 45.23 | 46.67 ± 8.86 | |||||

| Pavlovic, 2024 | <1,500 MET-min/wk, 4,245 (18.15) | 53 ± 8.7 | 28.8 ± 4.6 | 2,491 (58.68) | 786 (18.5) | NR | Zero | <25, 4,245 (100) | NR | 126.1 ± 14.6 | NR | 200.4 ± 38 | 124.4 ± 33.2 | 47.1 ± 12.6 |

| 1,500-3,000 MET-min/wk, 9,115 (38.39) | 50.4 ± 7.9 | 27.5 ± 3.7 | 6,129 (67.24) | 1,470 (16.1) | 3.09 ± 0.83 |

|

123.1 ± 13.4 | 196.1 ± 36.2 | 121 ± 32.2 | 51.1 ± 13.1 | ||||

| ≥3,000 MET-min/wk, 2,227 (9.52) | 48.3 ± 6.6 | 26 ± 2.9 | 1,991 (89.4) | 252 (11.3) | 8.075 ± 4.38 |

|

122.2 ± 12.9 | 198 ± 35.7 | 121.9 ± 31.6 | 54.2 ± 13.4 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD.

BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Quality assessment and risk of bias

The quality assessment of the 9 included studies (Supplement Table 2) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale demonstrated robust community representation and appropriate ascertainment of exposure, with all studies achieving an overall rating of good quality.

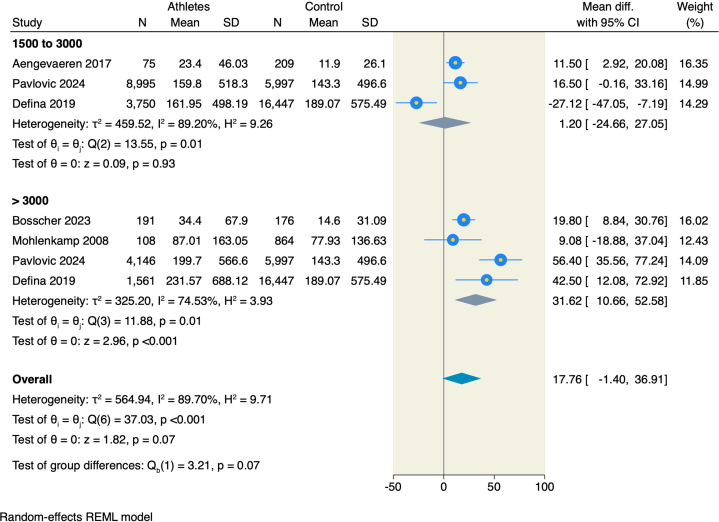

Subclinical atherosclerosis using CAC

Five studies18,20,21,23,24 assessed CAC scores in male athletes compared to nonathletes, and the pooled estimate CAC of athletes with 1,500 to 3,000 MET-min/wk was comparable to that of nonathletes (MD = 1.2; 95% CI: −24.66 to 27.05; P = 0.93; I2: 89.2%). However, male athletes with an exercise volume of >3,000 MET-min/wk showed notably higher mean CAC scores than male nonathletes (MD = 31.62; 95% CI: 10.66-52.58; P < 0.001; I2: 74.53%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest Plot of CAC Score in Males With a Subgroup Analysis on Exercise Volume

CAC = coronary artery calcification.

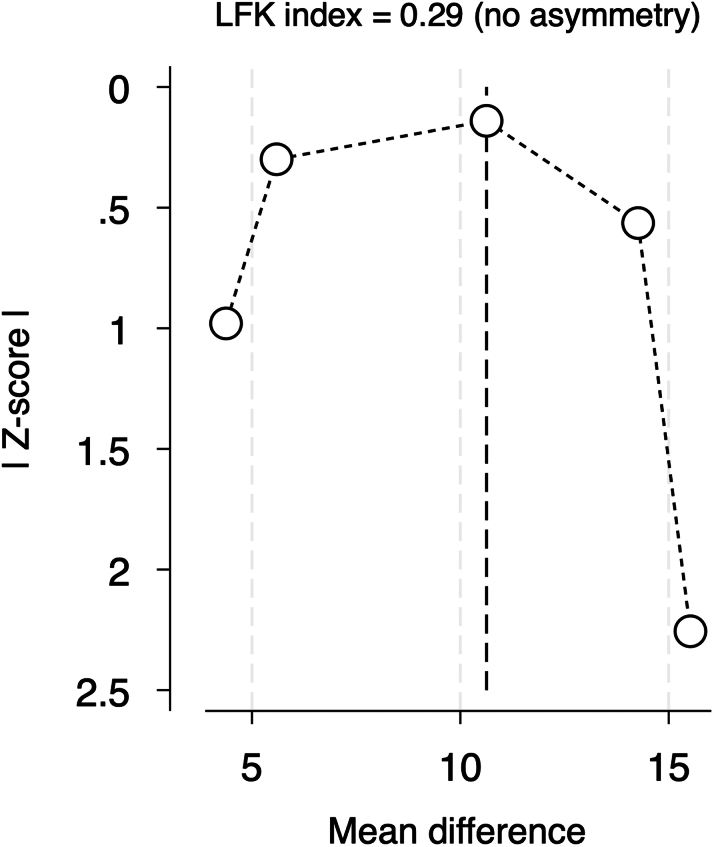

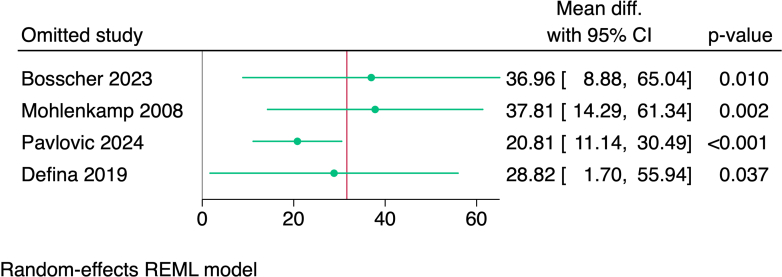

Publication bias was assessed using a DOI plot in which there was no asymmetry, with an LFK index of 0.29, indicating no significant publication bias (Figure 3). Moreover, we performed a sensitivity analysis (leave-one-out analysis) in athletes with an exercise volume of >3,000 MET-min/wk, and no study had a disproportional effect on the overall effect estimate (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Publication Bias Assessment of CAC Score in Male Athletes and Nonathletes Using DOI Plot Method

LFK index = 0.29, indicating no asymmetry is found and no publication bias is detected. Abbreviation as in Figure 2.

Figure 4.

Leave-One-Out Sensitivity Analysis in Male Athletes With an Exercise Volume of >3,000 MET-min/wk

MET = metabolic equivalent of task.

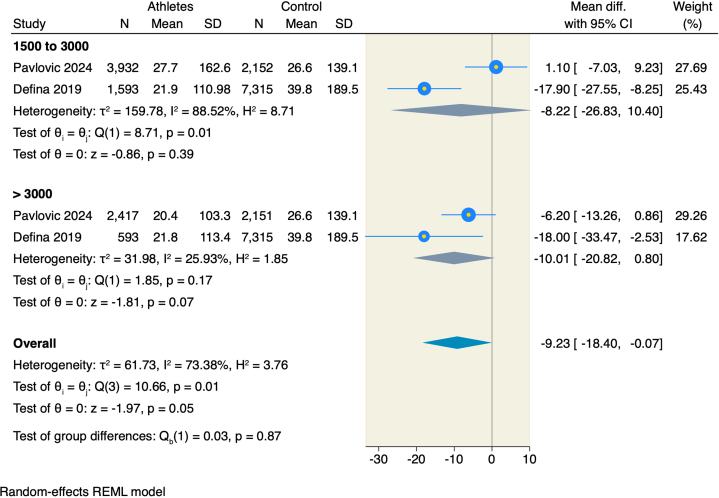

Only 2 studies assessed the differences in CAC scores between female athletes and nonathletes. In contrast with male athletes, female athletes achieving an exercise volume of 1,500 to 3,000 and >3,000 MET-min/wk showed no statistically significant difference compared to the female nonathlete group (MD = −8.22; 95% CI: −26.83 to 10.4; P = 0.39; and −10.01; 95% CI: −20.82 to 0.8; P = 0.07) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest Plot of CAC Score in Females With a Subgroup Analysis on Exercise Volume

Abbreviation as in Figure 2.

Meta-regression analysis showed no significant effect modification of mean age, baseline LDL-C levels, or BMI on the differences in CAC scores between male and female athletes and nonathletes (Supplement Table 3).

CAC stages

The prevalence of CAC scores between 0 and 10 AU was evaluated in 4 studies of participants with exercise volumes of >3,000 MET-min/wk.19,20,22,23 The analysis showed no significant differences in CAC prevalence between male (OR: 1.08; 95% CI: 0.81-1.43; P = 0.6; I2 = 0%) and female athletes (OR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.31-1.88; P = 0.55; I2 = 0%) compared with nonathletes (Supplement Figure 1). Similarly, when examining CAC scores between 10 and 100 AU, athletes (both male and female) with an exercise volume of >3,000 MET-min/wk had comparable prevalence to nonathletes, with ORs of 1.3 (95% CI: 0.74-2.3; P = 0.36; I2 = 73%) for males and 0.52 (95% CI: 0.16-1.71; P = 0.28; I2 = 0%) for females (Supplement Figure 2).

In 5 studies,18,20,22, 23, 24 male athletes with an exercise volume of >3,000 MET-min/wk had a higher prevalence of CAC scores between 100 and 400 AU than male nonathletes (OR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.22-1.62; P < 0.001; I2 = 0%), without significant difference between male athletes with an exercise volume of 1,500 to 3,000 MET-min/wk and male nonathletes (OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 0.91-1.6; P = 0.2; I2 = 19.01%) (Supplement Figure 3).

Only 2 studies22,24 evaluated the prevalence of CAC scores >100 to 400 AU among female athletes and found no significant differences between those with exercise volumes of 1,500 to 3,000 MET-min/wk or >3,000 MET-min/wk and female nonathletes. The respective ORs were 0.98 (95% CI: 0.79-1.23; P = 0.89; I2 = 0%) and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.67-1.12; P = 0.27; I2 = 0%) (Supplement Figure 4).

Finally, for CAC scores >400 AU, 3 studies20,22,23 reported no significant differences between athletes with exercise volumes of >3,000 MET-min/wk and nonathletes, either for males (OR: 1.57; 95% CI: 0.94-2.61; P = 0.08; I2 = 0%) or females (OR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.05-13.65; P = 0.89; I2 = 0%) (Supplement Figure 5).

Subclinical atherosclerosis using CCTA

Two studies reported the mean number of calcified lesions burden per patient by CCTA, of which the pooled estimate showed that male and female athletes with an exercise volume of 1,500 to 3,000 MET-min/wk had comparable number of calcified plaques compared to the nonathletes groups with the following values (MD = −0.03; 95% CI: −0.87 to 0.81; P = 0.95; I2 = 94.87%, and −0.24; 95% CI: −0.51 to 0.04; P = 0.09; I2 = 85.63%). However, female athletes with an exercise volume of >3,000 MET-min/wk showed lower number of calcified plaques per patient compared to the female nonathletes (MD = −0.26; 95% CI: −0.42 to −0.1; P < 0.001; I2 = 0%), without significant difference in males with an exercise volume of >3,000 MET-min/wk compared to nonathletes males (MD = 0.82; 95% CI: −0.14 to 1.78; P = 0.09; I2 = 92.45%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Secondary Outcomes by Sex

| Outcomes | Sex | Pooled Effect Sizes |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,500-3,000 MET-min/wk |

>3,000 MET-min/wk |

||||||

| No. of Studies | Mean Difference (95% CI) | Heterogeneity (I2, P Value) | No. of Studies | Mean Difference (95% CI) | Heterogeneity (I2, P Value) | ||

| No. of calcified plaques per patients | Males | 2 | −0.03 (−0.87 to 0.81, P = 0.95) | (94.87%, P < 0.001) | 2 | 0.82 (−0.14 to 1.78, P = 0.09) | (92.45%, P < 0.001) |

| Females | 2 | −0.24 (−0.51 to 0.04, P = 0.09) | (85.63%, P < 0.001) | 2 | −0.26 (−0.42 to −0.1, P < 0.001) | (0%, P = 0.28) | |

| Calcified lesions volume | Males | 1 | −16.23 (−27.56 to −4.9, P < 0.001) | – | 2 | 26.91 (12.06-41.76, P < 0.001) | (0%, P = 0.32) |

| Females | 1 | −10.75 (−16.52 to −4.98, P < 0.001) | – | 2 | −16.89 (−38.17 to 4.39, P = 0.12) | (29.18%, P = 0.16) | |

| Calcified plaques | Males | 1 | OR 1.52 (0.96-2.42, P = 0.07) | – | 2 | OR 2.31 (0.67-7.98, P = 0.19) | (87.42%, P < 0.001) |

| Females | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Moreover, the volume of calcified plaques was lower in male and female athletes with an exercise volume of 1,500 to 3,000 MET-min/wk compared to the nonathletes' groups with the following values, respectively (MD = −16.23 mm3; 95% CI: −27.56 to −4.9; P < 0.001, and −10.75 mm3; 95% CI: −16.52 to −4.98; P < 0.001). On the other hand, the volume of calcified plaques was higher in males with an exercise volume of >3,000 MET-min/wk compared to male nonathletes (MD = 26.91 mm3; 95% CI: 12.06-41.76; P < 0.001; I2 = 0%), without a significant difference in the female groups (MD = −16.89 mm3; 95% CI: −38.17-4.39; P = 0.12; I2 = 29.18%) (Table 3).

Additionally, the prevalence of calcified plaques was reported only in male athletes. There were no significant differences observed between male athletes with an exercise volume of 1,500 to 3,000 MET-min/wk and >3,000 MET-min/wk compared to male nonathletes regarding the incidence of calcified plaques, with the following values, respectively (OR: 1.52; 95% CI: 0.96-2.42; P = 0.07, 2.31; 95% CI: 0.67-7.98; P = 0.19) (Table 3).

Discussion

Our meta-analysis of 9 studies, encompassing 61,150 participants, addressed the effect of exercise on the prevalence of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis across different exercise volume levels (Central Illustration). The present analysis included healthy participants without any prior CVD and found the following: 1) male athletes engaging in exercise volume exceeding 3,000 MET-min/wk had significantly higher mean CAC scores and total calcified plaque volumes, as determined by CAC dedicated scans and CCTA, respectively, compared to nonathletes, while male athletes exercising between 1,500 and 3,000 MET-min/wk had significantly lower total calcified plaque volumes than nonathletes; 2) female athletes exercising above 3,000 MET-min/wk had a significantly lower number of calcified plaques per patient than nonathletes, and female athletes with exercise volumes between 1,500 and 3,000 MET-min/wk had significantly lower total calcified plaque volumes than nonathletes, as assessed by CCTA.

Central Illustration.

Sex Differences in the Impact of Exercise Volume on Subclinical Coronary Atherosclerosis: A Meta-Analysis

CAD = coronary artery disease; CCTA = coronary computed tomography angiography; CT = computed tomography; other abbreviations as in Figures 2 and 4.

Various factors influence the development of coronary atherosclerosis in athletes; however, the precise mechanisms remain unclear. One theory suggests that elevated shear stress during intense exercise causes endothelial damage, leading to atherosclerotic plaque formation through repeated injury and calcification.27,28 Statin use in athletes may also contribute to plaque calcification and plaque stabilization over time. Other potential contributors include dietary intake, psychological stress, chronic inflammation, and genetics.29 Some studies have proposed that intense exercise may accelerate the progression of pre-existing CAD, and mechanical pressure on calcified plaques could lead to plaque rupture and thrombus formation.30,31 Elevated parathyroid hormone levels and inflammation during intense exercise may further promote atherosclerosis.32 Vascular oxidative stress, caused by intense exercise, could contribute to coronary artery calcification. Hormonal factors like testosterone may also play a role in calcification, but more research is needed.33,34

The influence of factors such as sex, exercise volume, ethnicity, and sport type on CAD development in athletes remains insufficiently understood. Females in particular are underrepresented in studies examining the effects of high-volume exercise on CVD outcomes. The scarcity of data in female cohorts suggests a lower prevalence of CAD among women. In a study by Merghani et al22 involving 244 individuals (athletes and controls) with a low 10-year Framingham Risk Score (FRS) for CAD and using CCTA, male athletes exhibited a higher likelihood of moderate to severe CAC ≥300 and atherosclerotic plaques with luminal abnormalities than controls. However, among female participants, no significant differences were observed between the athletes and controls in the number of plaques (15% vs 21%; P = 0.57), CAC ≥100 (7% vs 11%; P = 0.62), or plaque incidence. Roberts et al26 analyzed subclinical CAD using CCTA in 26 lifelong female marathon runners (each having completed at least one marathon annually for 10-25 years). They found these athletes had reduced coronary calcium burden, a lower prevalence of plaques, and smaller plaque volumes than controls. Our pooled analysis contrasts with previous studies which reported that high-volume female athletes had more calcified plaques per patient than nonathletes. In contrast, female athletes with moderate exercise volumes had significantly lower total calcified plaque volumes than nonathletes.22,24 However, the findings of other studies may be confounded by differences in baseline CVD risk profiles, as the control group had higher BMI and a greater prevalence of traditional CVD risk factors.

In most previous studies, elite male athletes showed higher CAC scores and greater coronary atherosclerosis prevalence than risk-matched controls. The Measuring Athlete’s Risk of Cardiovascular Events (MARC) study found occult CAD in 16% of 318 middle-aged athletes with low CV risk, defined as CAC >100 or significant coronary stenosis on CCTA.35 Mohlenkamp et al23 investigated subclinical atherosclerosis in 108 experienced recreational marathon runners aged 50 or older, with no history of cardiac disease, comparing them to age- and FRS-matched controls. Despite lower FRS values, 36% of runners had CAC scores >100, similar to controls. These findings are in contrast to our pooled analysis. Specifically, the referenced study found no significant differences between runners and controls regarding the prevalence of CAC scores >100. Our pooled analysis demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of CAC scores >100 in male athletes compared to nonathletes. Potential explanations are the variability in the volume and intensity of regular PA and marathon running. Factors such as years of active running, number of marathons completed, or weekly training mileage may account for this heterogeneity, potentially affecting the paradoxical effect of excessive exercise volume on CAC scores.

The prognostic implications of high CAC scores and subclinical CAD in athletes remain unclear. Concerns have arisen that lifelong high-volume exercise may increase CV risk, as seen in a French study reporting CAD in 95% of nearly 900 sudden sports-related deaths. Athletes with high-risk pre-existing CAD may be particularly vulnerable to myocardial infarction during high-volume exertion. While calcified plaques, common in athletes with elevated CAC, are linked to reduced rupture risk, high CAC scores (>400) significantly increase the likelihood of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) compared to a CAC score of 0 (34% vs 2.1%). The Mohlenkamp trial showed a lower prevalence of zero CAC (28.7% vs 47.5%) and higher event frequency at CAC >100 compared to the MARC study.23

Despite elevated CAC in athletes, lower exercise levels are associated with greater atherosclerosis progression, as evidenced by the findings of Delaney et al36 in the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) trial. Similarly, studies by Ji et al, Gao et al, and Radford et al suggest that PA mitigates CVD risks, even with high CAC scores.8,37,38 German et al reinforced these results, showing that increased PA reduces all-cause mortality, irrespective of CAC levels. Moreover, higher cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) was linked to reduced CAD risk, with each 1 MET increase in CRF lowering CVD event rates by 14%.39 These findings underscore the protective effects of PA and CRF against CVD events, even in individuals with elevated CAC levels.40

The benign nature of coronary atherosclerosis in athletes has been questioned by the Master Heart study20 comparing 191 lifelong elite endurance athletes with 176 healthy nonathletes with low CVD risk profiles. Excluding individuals with a history of smoking, dyslipidemia, hypertension, or diabetes, the study revealed that athletes had a more significant coronary plaque burden. Athletes exhibited higher frequencies of noncalcified and mixed plaques, proximal plaques, and considerable stenosis (OR: 1.96; 95% CI: 1.24-3.11), all associated with increased CVD risk. Although CAC is linked to adverse CVD events in the general population, its implications for elite athletes remain uncertain, and elevated CAC should not discourage PA. However, it is worth noting that they used a self-report questionnaire rather than continuous tracking of training logs over time to define the different levels of exercise and atherosclerotic CVD risk factors, which may lead to underestimation of these factors at the study's baseline. Limiting their population to male participants, owing to the lower risk of CAD in females may also have a minor contribution. This study underscores the importance of integrating CT findings with CVD risk factors, symptoms, and electrocardiogram findings. This nuanced issue requires further investigation to clarify its implications for athletes' CV health.

A recent study by Pavlovic et al24 extended beyond conventional variables and explored the relationship between PA intensity and duration and CAC. A negative association was observed between PA intensity and CAC >100 AU, whereas the total weekly PA duration was positively correlated with CAC levels. Their study demonstrated a 2.4% increase in mean CAC per hour of PA and a 19.9% increase in mean CAC in men engaging in ≥5 hours of weekly PA vs <5 hours. They hypothesized that regular moderate-to-vigorous exercise may reduce atherogenic small, dense LDL particles, replacing them with larger, less harmful LDL. Additional benefits include reductions in blood pressure, LDL-C, triglycerides, fasting glucose, and hemoglobin A1C, alongside increases in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. However, high PA volumes may provoke an inflammatory response, potentially contributing to plaque formation, particularly in elite athletes.

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to examine the relationship between subclinical coronary atherosclerosis and exercise volume, stratifying participants by sex and excluding those with prior CAD or CVD risk factors. Furthermore, we categorized participants based on CAC stages to approximate the extent to which CAC influences CAD risk, given that a CAC score ≥400 AU is associated with an estimated 34% risk of MACE, compared to a significantly lower risk of approximately 2.1% for a CAC score of 0.41,42 Additionally, we attempted to analyze CCTA data stratified by plaques per patient and calcified lesion volume, but this was feasible in only 2 studies owing to a lack of data.

Study limitations

Several limitations may hinder the generalizability of our findings. While we attempted to stratify confounding variables, the pooled studies still offer opportunities for further validation. One such variable is race/ethnicity, as it is well established that race/ethnicity may influence CAC levels, with most studies predominantly focusing on White populations. Another major issue in the existing literature is that CAC images only calcified plaques while not visualizing noncalcified plaque. While CCTA could visualize noncalcified plaques, there was very limited data on noncalcified plaques among the included studies, precluding a separate analysis. Moreover, CCTA could also miss small amounts of CAC due to the administration of intravenous contrast, which may be important when quantifying individuals with low CAC levels. Additionally, as the studies included in our analysis were observational, they were subject to inherent biases due to the study design, and causality could not be established. Finally, there are limited data for female athletes and potential biases introduced mainly by predominantly male cohorts. These limitations underscore the need for future high-quality longitudinal studies that account for these confounding factors and establish standardized cutoff points.

Implication on clinical practice

This meta-analysis showed a higher prevalence of CAC and plaque volume can be present in high-exercise volume male athletes, despite the lower estimated CV risk. Therefore, the possibility of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis and need for preventive therapies should not be excluded. Standard estimation of CVD risk may result in an underestimation of the actual presence of atherosclerosis in athletes. In addition, athletic conditioning, with improvements in microvascular function and vessel size among athletes, may play a role in the disassociation between subclinical coronary atherosclerosis and mortality in athletes. However, long-term assessment is mandatory to assess the relationship between subclinical atherosclerosis, exercise volume, and clinical events in athletes.

Conclusions

Male athletes engaging in high-volume exercise had significantly higher CAC scores and total calcified plaque volume. In contrast, those with moderate-volume exercise exhibited lower plaque volumes than nonathletes. Female athletes with high-volume exercise showed lower number of calcified plaques, whereas those with moderate-volume exercise demonstrated less plaque volumes. These results highlight the relationship between exercise volumes and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis, in addition to these noted sex differences. Our findings have potential implications for individualized exercise recommendations.

However, our findings are tempered by limitations, including the observational nature of the included studies, limited data on plaque composition, and a lack of racial diversity, which restrict the generalizability and causal interpretation of the results. Future high-quality longitudinal studies are imperative to address these gaps, refine our understanding of the impact of exercise on atherosclerosis, clarify the prognostic value of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis in athletes and establish standardized thresholds for optimal exercise volume.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: This meta-analysis showed that a higher prevalence of CAC and plaque can be present in high-volume male athletes, despite the lower estimated CV risk. Therefore, the possibility of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis and need for preventive lifestyle changes and therapies should not be excluded. Standard estimation of CVD risk may result in an underestimation of the actual presence of atherosclerosis in athletes. In addition, athletic conditioning, with improvements in microvascular function and vessel size among athletes, may play a role in the disassociation between CAC and mortality in athletes.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Long-term assessment is mandatory to assess the relationship between subclinical atherosclerosis, exercise volume, and clinical events in athletes.

Funding support and author disclosures

Drs Lorenzatti, Filtz, and Slipczuk are supported by institutional grants from Amgen and Philips. Dr Gulati has served on the advisory boards of Esperion, Novartis, and Medtronic. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Mahmoud Gomaa, Dr Ibrahim Kamal, Dr Ahmed Yasser Shaban, Dr Karim Atta, and Dr Atef Hassan for their assistance with primary data collection and the editing services.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental tables and figures, please see the online version of this paper.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Sharalaya Z., Phelan D. Cardiac risk of extreme exercise. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2019;27:e1–e7. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggish A.L., Levine B.D. Coronary artery calcification among endurance athletes. Circulation. 2017;136:149–151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma S., Merghani A., Mont L. Exercise and the heart: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1445–1453. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Keefe J.H., Patil H.R., Lavie C.J., Magalski A., Vogel R.A., McCullough P.A. Potential adverse cardiovascular effects from excessive endurance exercise. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapero K., Deluca J., Contursi M., et al. Cardiovascular risk and disease among masters endurance athletes: insights from the Boston MASTER (Masters Athletes Survey to Evaluate Risk) initiative. Sports Med Open. 2016;2:29. doi: 10.1186/s40798-016-0053-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah A.B., Torguson R., Alexander K., et al. Cardiovascular risk among ultra-endurance runners. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2021;61:1700–1705. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.21.11903-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato Y., Kawakami R., Sakamoto A., et al. Sex differences in coronary atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2022;24(1):23–32. doi: 10.1007/s11883-022-00980-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ji H., Gulati M., Huang T.Y., et al. Sex differences in association of physical activity with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83(8):783–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achenbach S., Raggi P. Imaging of coronary atherosclerosis by computed tomography. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1442–1448. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins J.P.T., Thomas J., Chandler J., et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5. Cochrane; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelliccia A., Sharma S., Gati S., et al. 2020 ESC guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:17–96. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ainsworth B.E., Haskell W.L., Herrmann S.D., et al. 2011 compendium of physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agatston A.S., Janowitz W.R., Hildner F.J., Zusmer N.R., Viamonte M., Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leipsic J., Abbara S., Achenbach S., et al. SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary CT angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2014;8:342–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells G., Shea B., O'Connell D., et al. 2000. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Non-Randomized Studies in Meta-Analysis.http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbas A., Hefnawy M.T., Negida A. Meta-analysis accelerator: a comprehensive tool for statistical data conversion in systematic reviews with meta-analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2024;24:243. doi: 10.1186/s12874-024-02356-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.StataCorp . StataCorp LLC; 2023. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aengevaeren V.L., Mosterd A., Braber T.L., et al. Relationship between lifelong exercise volume and coronary atherosclerosis in athletes. Circulation. 2017;136:138–148. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachman N.P., Terwoord J.D., Richards J.C., et al. Comprehensive assessment of cardiovascular structure and function and disease risk in middle-aged ultra-endurance athletes. Atherosclerosis. 2021;320:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Bosscher R., Dausin C., Claus P., et al. Lifelong endurance exercise and its relation with coronary atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:2388–2399. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeFina L.F., Radford N.B., Barlow C.E., et al. Association of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality with high levels of physical activity and concurrent coronary artery calcification. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:174. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merghani A., Maestrini V., Rosmini S., et al. Prevalence of subclinical coronary artery disease in masters endurance athletes with a low atherosclerotic risk profile. Circulation. 2017;136:126–137. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohlenkamp S., Lehmann N., Breuckmann F., et al. Running: the risk of coronary events: prevalence and prognostic relevance of coronary atherosclerosis in marathon runners. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1903–1910. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavlovic A., DeFina L.F., Leonard D., et al. Coronary artery calcification and high-volume physical activity: role of lower intensity vs. longer duration of exercise. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2024;31:1526–1534. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwae150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz R.S., Kraus S.M., Schwartz J.G., et al. Increased coronary artery plaque volume among male marathon runners. Mo Med. 2014;111:89–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts W.O., Schwartz R.S., Kraus S.M., et al. Long-term marathon running is associated with low coronary plaque formation in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49:641–645. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavie C.J., Hecht H.F., Wisloff U. Extreme physical activity may increase coronary calcification, but fitness still prevails. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3:103–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y.-X., Liu H.-B., Li P.-S., et al. ROS and NO dynamics in endothelial cells exposed to exercise-induced wall shear stress. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2019;12:107–120. doi: 10.1007/s12195-018-00557-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puri R., Nicholls S.J., Shao M., et al. Impact of statins on serial coronary calcification during atheroma progression and regression. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heusch G., Schulz R., Baumgart D., Haude M., Erbel R. Coronary microembolization. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2001;44:217–230. doi: 10.1053/pcad.2001.26968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin J., DeLuca J.R., Lu M.T., et al. Extreme endurance exercise and progressive coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:293–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franck G., Even G., Gautier A., et al. Hemodynamic stress- induced breaches of the arterial intima trigger inflammation and drive atherogenesis. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:928–937. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mody N. Oxidative stress modulates osteoblastic differentiation of vascular and bone cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:509–519. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00610-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kojda G., Hambrecht R. Molecular mechanisms of vascular adaptations to exercise. Physical activity as an effective antioxidant therapy? Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braber T.L., Mosterd A., Prakken N.H., et al. Occult coronary artery disease in middle-aged sportsmen with a low cardiovascular risk score: the Measuring Athlete's Risk of Cardiovascular Events (MARC) study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:1677–1684. doi: 10.1177/2047487316651825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delaney J.A.C., Jensky N.E., Criqui M.H., Whitt-Glover M.C., Lima J.A.C., Allison M.A. The association between physical activity and both incident coronary artery calcification and ankle brachial index progression: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2013;230:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radford N.B., DeFina L.F., Leonard D., et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness, coronary artery calcium, and cardiovascular disease events in a cohort of generally healthy middle-age men. Circulation. 2018;137:1888–1895. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao J.-W., Hao Q.-Y., Lu L.-Y., et al. Associations of long-term physical activity trajectories with coronary artery calcium progression and cardiovascular disease events: results from the CARDIA study. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56:854–861. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-105092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.German C.A., Fanning J., Singleton M.J., et al. Physical activity, coronary artery calcium, and cardiovascular outcomes in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2022;54:800–806. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lavie C.J., Wisløff U., Blumenthal R.S. Extreme physical activity and coronary artery calcification-running heavily and safely with “hearts of stone”. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(2):182–183. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng A.W., Mirbolouk M., Orimoloye O.A., et al. Long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality in asymptomatic patients with CAC ≥1,000. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Celeski M., Di Gioia G., Nusca A., et al. The spectrum of coronary artery disease in elite endurance athletes—a long-standing debate: State-of-the-Art Review. J Clin Med. 2024;13:5144. doi: 10.3390/jcm13175144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.