Abstract

Oxidation of alkenes with O3 and photoexcited nitroarenes represents one of the most attractive organic chemical transformations for the synthesis of oxygen-enriched molecules. However, known achievements are mainly limited to carbon chain-shortened oxidation and carbon chain-retained oxidation of alkenes. Given that constructing higher molecular complexity is the core goal of modern synthesis, the development of chain-elongated oxidation of alkenes would be in high demand but still remains an elusive challenge so far. Herein, we report a photoexcited nitroarene-enabled highly regioselective chain-elongated oxidation of alkenes via tandem oxidative cleavage and dipolar cycloaddition, providing a broad range of synthetically-useful isoxazolidines in up to 92% yield from readily available enol ethers or styrene and derivatives under simple and mild conditions.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Photocatalysis

Chain-elongating oxidations enable molecular complexity to be carefully and logically assembled. Herein, the authors report a photoexcited nitroarene-enabled regioselective chain-elongated oxidation of alkenes via tandem oxidative cleavage and dipolar cycloaddition, providing a broad range of synthetically-useful isoxazolidines from readily available enol ethers or styrene and derivatives.

Introduction

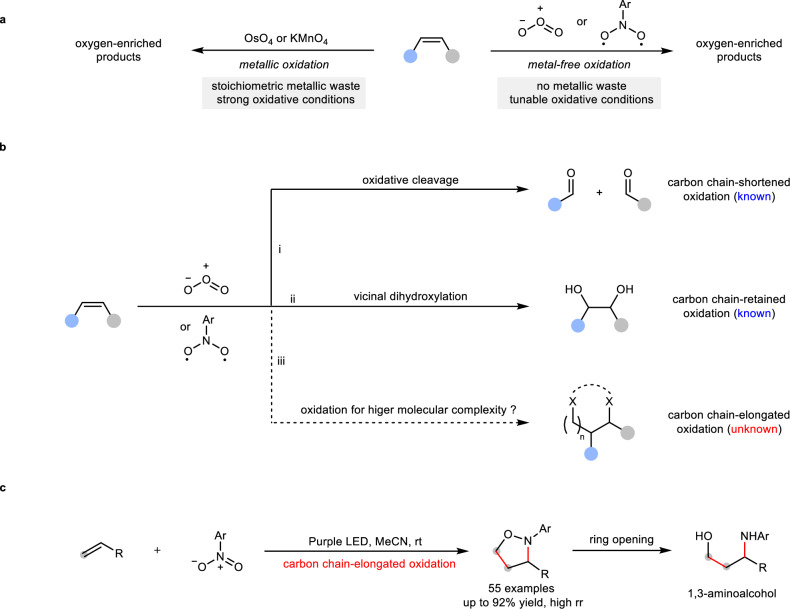

Oxidation of alkenes is one of the most fundamental chemical transformations, not only because alkenes are feedstock chemicals that are readily available from petroleum and biomass, but also because such oxidations provide convenient and economical routes to oxygen-enriched molecules such as epoxides, 1,2-diols and carbonyls, which are prevalent in numerous natural products, pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals1–7. Widely-used oxidants for alkene oxidation are metal oxides such as OsO4 and KMnO4, yielding desired oxygen-enriched products but with stoichiometric metallic waste (Fig. 1a, left)8–18. To eliminate metallic waste towards achieving greener oxidation methods, non-metal oxidants such as ozone (O3)19–28 and its surrogates, photoexcited nitroarenes29–57, have received constantly growing interest during the past decades (Fig. 1a, right). For example, the ozonolysis reaction of alkenes is a well-known process, effectively converting alkenes into various carbon chain-shortened carbonyl products (Fig. 1b, path i)19. Recently, Leonori and Parasram independently found that photoexcited nitroarenes was superior surrogates of ozone, enabling oxidative cleavage of alkenes in a safer and more cost-economical fashion37,38. Moreover, it was revealed that photoexcited nitroarenes with proper electron-withdrawing substituents on the aryl rings have a more tunable oxidative ability than ozone. Followed oxidative cleavage reactions that lead to carbon chain-shortened oxidations of alkenes, a dihydroxylation reaction of alkenes was recently developed by Thomas et al. (Fig. 1b, path ii)40, who used ozone as an oxidant and iPrMgBr as a trapping nucleophile to intercept oxidative intermediate, thus obtaining vicinal diols that have increasing molecular complexity than carbonyl products from traditional ozonolysis, because carbon chains of alkenes are not broken, instead, well retained. In the same year, Leonori et al. also realized a photoexcited nitroarene-enabled dihydroxylation of alkenes via one-pot N–O bond hydrogenation under milder and more practical conditions41. Beyond dihydroxylation, most recently, Parasram et al. reported a new type of carbon chain-retained oxidation, in which alkenes are oxidized into the corresponding carbonyls (monohydroxylation)56. Compared with the great advances in carbon chain-shortened oxidations (ozonolysis) and carbon chain-retained oxidations (dihydroxylation or monohydroxylation), the development of carbon chain-elongated oxidation of alkenes to construct higher molecular complexity still remains an elusive challenge (Fig. 1b, path iii). During our submission, Li and co-workers reported a carbon chain-elongated oxidation of terminal alkenes, providing a series of isoxazolidines in up to 70% yield57. Here, we show a safe and green photoexcited nitroarene-enabled carbon chain-elongated oxidation of alkenes via tandem oxidative cleavage and dipolar cycloaddition (Fig. 1c), providing a wide range of synthetically-useful isoxazolidines in up to 92% yield with high regioselectivity58,59, which are versatile synthetic precursors to important organic molecules such as 1,3-aminoalcohols.

Fig. 1. Oxidation of alkenes with ozone or photoexcited nitroarenes.

a Two main types of oxidation of alkenes. b Three possible pathways for oxidation of alkenes by O3 and photoexcited nitroarenes: carbon chain-shortened oxidation via oxidative cleavage of alkenes (path i, known); carbon chain-retained oxidation via vicinal dihydroxylation (path ii, known); carbon chain-elongated oxidation (path iii, unknown). c This work: photoexcited nitroarene-enabled carbon chain-elongated oxidation via tandem oxidative cleavage and dipolar cycloaddition.

Results

Reaction development

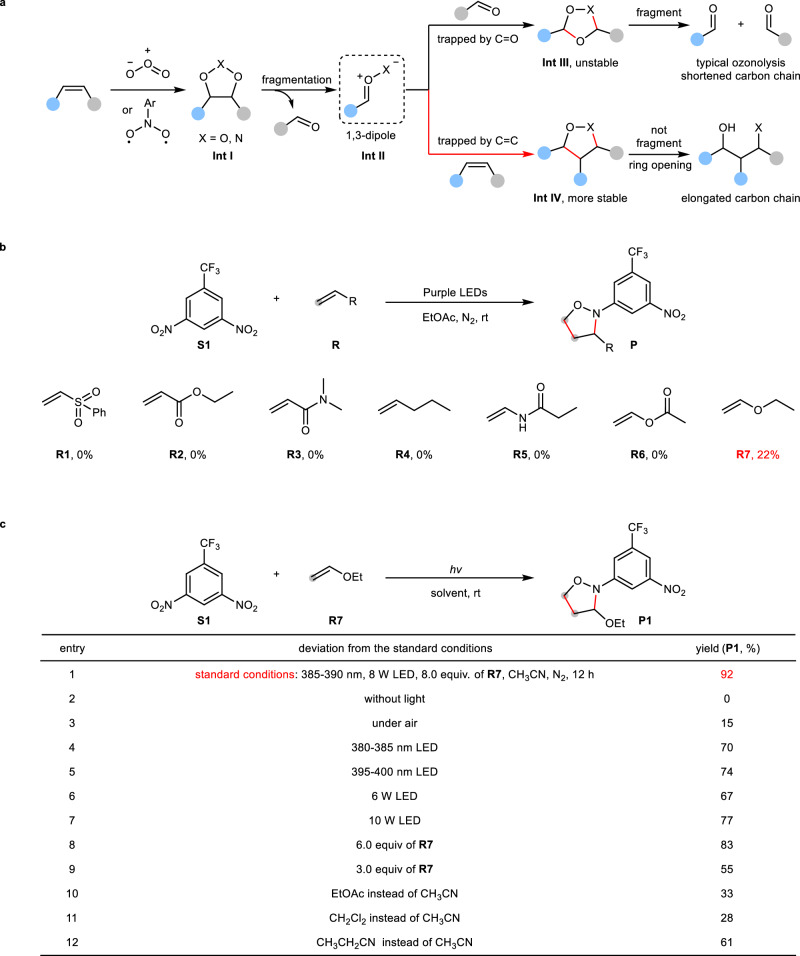

In ozone or nitroarene-mediated oxidation of alkenes (Fig. 2a)26–28, initially formed heterocycles (Int I) such as primary ozonide (X = O) or 1,3,2-dioxazolidines (X = N) easily fragment into 1,3-dipoles (Int II), including carbonyl oxides (X = O) or carbonyl imines (X = N). These intermediates can be quickly trapped by polar C = O double bonds to generate more unstable heterocycles (Int III) such as secondary ozonide (X = O) or 1,4,2-dioxazolidine (X = N). Subsequent fragmentation gives carbon chain-shortened carbonyls as products. To shift this pathway towards achieving higher molecular complexity, we envisioned to use non-polar C = C bond instead of polar C = O double bond to trap 1,3-dipole (Int II), thus forming a more stable heterocycle (Int IV) that would not undergo fragmentation, instead, act as a carbon chain-elongated oxidative product. However, two critical challenges have to be overcome: 1,3-dipoles need to be stable enough to be trapped, and non-polar C = C must override polar C = O double bond in the capture of 1,3-dipoles. With these considerations in mind, we selected highly-tunable nitroarenes as oxidants to investigate representative alkenes (Fig. 2b), because nitroarenes with strong electron-withdrawing groups have been proved to be able to provide more stable 1,3-dipoles during the oxidation of alkenes37,38. With 3,5-dinitrotrifluorotoluene as a model oxidant, various terminal alkenes with different electronic property were examined, and the results showed that most alkenes bearing either electron-withdrawing substituents (R1–R3) or electron-donating substituents such as alkyl group (R4), amido group (R5) and acetoxyl group (R6) did not give the desired products. Only the electron-donating ethoxyl group (R7) proved effective, affording the isoxazolidine product in 22% yield. Further systematic survey on light source, light intensity, loadings of alkenes and solvents disclosed the optimal conditions: 385–390 nm and 8 W LED light, 8.0 equivalents of ethoxyethene (R7) in CH3CN under N2 atmosphere at room temperature, under which the desired product (P1) was obtained in 92% yield (Fig. 2c, entry 1). Control experiments showed that the absence of light completely shut down the reaction (entry 2), and the presence of O2 also greatly diminished the yield (entry 3). In addition, the wavelength and the intensity of light had a strong influence on the yield, and slight variations resulted in lower yields (entries 4–7). Another two critical factors directly impacting the reactivity are solvents and loadings of alkenes (entries 8–12). The use of 8 equivalents of alkenes and CH3CN was the best option.

Fig. 2. Reaction development.

a Reaction proposal: the interception of 1,3-dipole with polar C = O will lead to typical ozonolysis, while the interception of 1,3-dipole with nonpolar C = C will give carbon chain-elongated oxidation reaction of alkenes. b Alkene identification. Reaction conditions: S1 (0.2 mmol), R (0.6 mmol), EtOAc (2.0 mL), 8 W 385–390 nm LED, N2, room temperature, 12 h; yield was determined by 1H NMR using Cl2CHCHCl2 as the internal standard. c Conditions optimization. Optimal conditions: S1 (0.2 mmol), R7 (1.6 mmol), CH3CN (2.0 mL), 8 W 385–390 nm LED, N2, room temperature, 12 h; yield was determined by 1H NMR using Cl2CHCHCl2 as the internal standard.

Scope of nitroarenes and alkenes

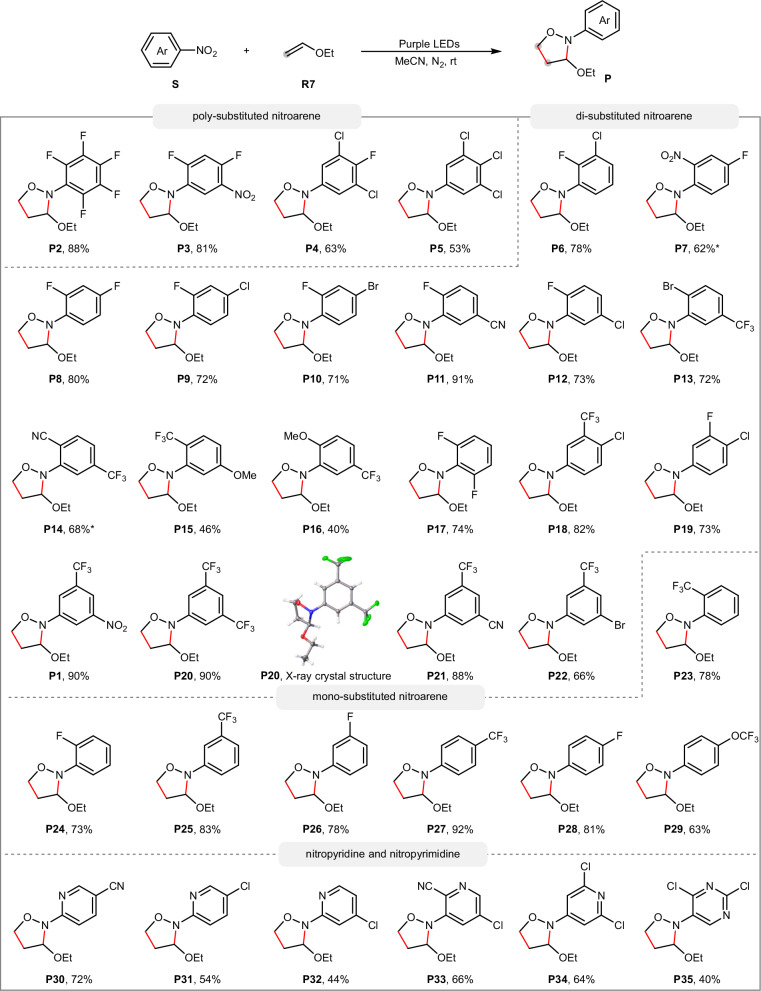

With the optimal reaction conditions established, we turned to investigate the scope of nitroarenes (Fig. 3). As demonstrated by previous oxidations37,38,41, the presence of electron-withdrawing groups on the aryl ring was essential to the reactivity. Three or more electron-withdrawing groups such as F, Cl, and NO2 on the aryl ring were well compatible, providing the corresponding products in 53–88% yield (P2–P5). Various combinations of two electron-withdrawing groups such as F, Cl, Br, CN, CF3 and NO2 at different positions of the aryl ring were also suitable. For example, 2,3-disubstituted (P6), 2,4-disubstituted (P7 to P10), 2,5-disubstituted (P11–P16), 2,6-disubstituted (P17), 3,4-disubstituted (P18, P19) and 3,5-disubstituted (P20, P21, P22) nitroarenes all underwent the reaction very well, providing the corresponding products in up to 91% yield. The structure of P20 was further confirmed by the single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Notably, when the CF3 group was presented, even an electron-donating methoxyl group was also tolerated (P15, P16). Encouraged by this result, we then examined nitroarenes bearing only one electron-withdrawing group at the aryl ring such as F, CF3 and OCF3 at ortho (P23, P24), meta (P25, P26) or para (P27, P28, P29) positions and found that they all worked well in the reaction, delivering 63–92% yield. It is worth noting that nitroheteroarenes such as nitropyridines and nitropyrimidines were also effective oxidants, providing the corresponding products in 40–72% yield (P30–P35).

Fig. 3. Scope of nitroarenes.

Reaction conditions: S (0.2 mmol), R7 (1.6 mmol), MeCN (2.0 mL), 8 W 385–390 nm LED, N2, room temperature, 12 h; yield of isolated products. *16 h.

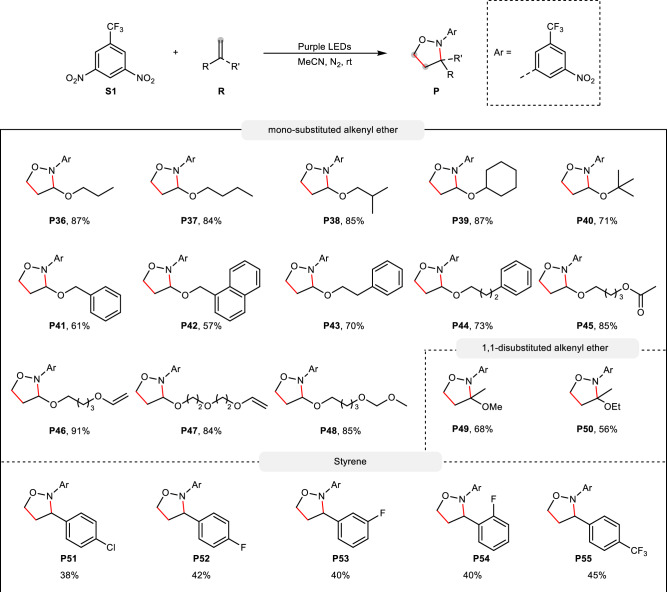

Next, the scope of alkoxy alkenes was investigated (Fig. 4). Alkyl groups varing from linear alkyl groups (P36, P37), branched alkyl groups (P38, P39), highly sterically-hindered alkyl groups (P40) to alkyl groups attched by functional groups such as aryl group (P41–P43), O-containing functional groups (P44–P48) were well compatible, delivering the corresponding products in 53 − 91% yield. When alkenes contain double enol ethers, only one enol ether was oxidized into isoxazolidine without observing full oxidation of the two enol ethers (P46, P47).

Fig. 4. Scope of alkenes.

Reaction conditions: S1 (0.2 mmol), R (1.6 mmol), MeCN (2.0 mL), 8 W 385–390 nm LED, N2, room temperature, 12 h; yield of isolated products.

Besides mono-substituted alkenes, 1,1-disubstituted alkenes were also effective, giving the corresponding products in 56 − 68% yield (P49, P50), while sterically-hindered internal alkenes were, in general, ineffective in the reaction. Notably, styrene and derivatives also proved effective in the current oxidation reaction, providing a mixture of regioisomers in up to 66% yield (P51 to P55).

Reaction utility and mechanistic discussion

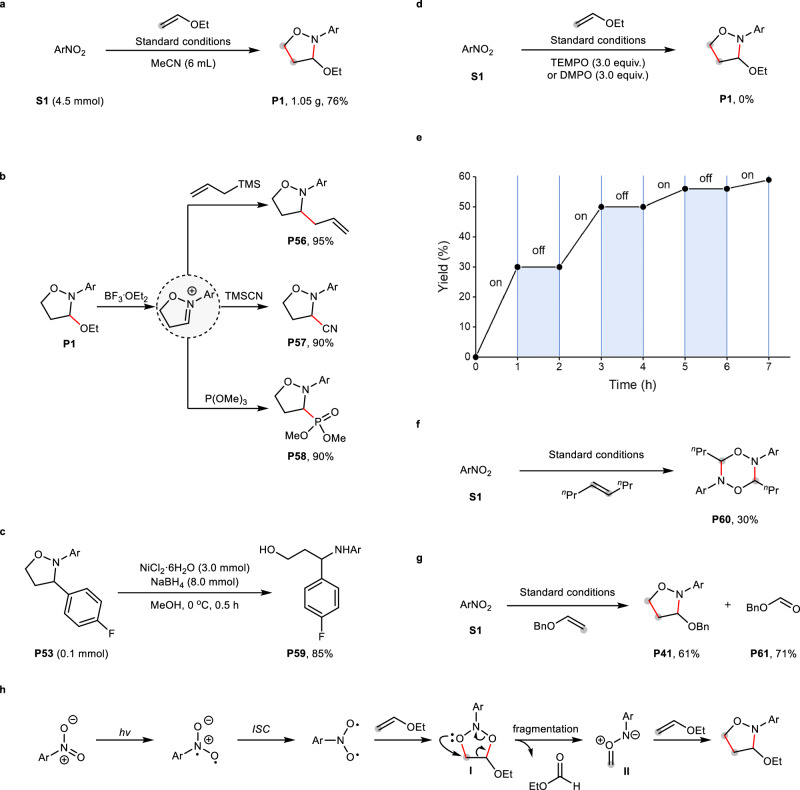

To demonstrate the utility of the current method, the model reaction was run at gram scale, smoothly affording product P1 in 76% yield (Fig. 5a). Ethoxyl group-containing isoxazolidines proved to be versatile precursors (Fig. 5b). The treatment of P1 with BF3·Et2O produced a reactive iminium intermediate, which can be in situ trapped by various nucleophiles such as allyltrimethylsilane (P57), trimethylsilyl cyanide (P58) and trimethyl phosphite (P59), providing the corresponding products in 90–95% yield.

Fig. 5. Synthetic utility and mechanistic experiments.

a Gram-scale reaction. b Versatile transformations of ethoxyl group of isoxazolidine. c Ring opening of isoxazolidine for 1,3-aminoalcohol. d Radical trapping experiment. e Light on-off experiments. f Intermediate trapping experiment. g Isolated byproduct. h Proposed mechanism. Ar = 3-NO2-5-CF3-C6H3.

When treated with nickel chloride hexahydrate and sodium borohydride, isoxazolidine P54 was easily transformed into 1,3-aminoalcohol in 85% yield via the cleavage of O–N bond (P60, Fig. 5c). To gain more insight into the mechanism, relevant mechanistic studies were conducted. The addition of radical scavengers such as (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl (TEMPO) and 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) completely inhibited the oxidation (Fig. 5d), indicating that a radical process may be involved. Light “on–off” experiments confirmed the necessity of continuous irradiation for the oxidation (Fig. 5e). When a sterically-hindered internal alkene was used as a substrate, unexpected product P60 instead of isoxazolidine was observed (Fig. 5f). We reasoned that P60 came from the combination of two carbonyl imine intermediates that cannot be intercepted by bulky internal alkene. The observed aldehyde P61 formation under standard conditions suggests a reaction pathway involving ozone-like intermediate-mediated alkene cleavage (Fig. 5g). On the basis of these results and previous studies37,38, a plausible mechanism was then proposed as follows (Fig. 5h): photoexcitation of nitroarene and subsequent intersystem crossing (ISC) forms a biradical intermediate, which then undergoes radical addition with an alkene to provide a short-lived heterocycle I. The fragmentation of I affords a crucial carbonyl imine intermediate II along with an aldehyde as a byproduct. Finally, intermediate II is trapped by the alkene to produce the desired isoxazolidine product.

In summary, we have developed a photoexcited nitroarene-enabled carbon chain-elongated oxidation of alkenes via tandem oxidative cleavage and dipolar cycloaddition, wherein the alkene first undergoes oxidative cleavage to form a key carbonyl imine dipole that is captured by the alkene itself to give the final carbon chain-elongated oxidative product. The use of proper alkenes such as enol ether or styrene and derivatives proves critical to the reactivity, and a wide range of isoxazolidines can be obtained in up to 92% yield with high regioselectivity. The reaction demonstrates that the development of versatile transformations beyond ozonolysis and dihydroxylation for ozone or photoexcited nitroarene-enabled oxidation of alkenes is feasible.

Methods

General procedure for synthesis of 1,2-isoxazolidines

To a 30 mL oven-dried photoreaction tube were added nitroarenes (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), dry degassed MeCN (2.0 mL), and alkenes (1.6 mmol, 8.0 equiv.) in an N2-filled glove-box. The tube was sealed, removed out of the glove box, and irradiated by purple light (385 nm, 8 W) in paralleled reactor for 12 h or until the reaction was completed. Crude product was obtained after evaporation of solvents, and further purified by flash column chromatography on neutral silica gel (eluting with Et3N/ethyl acetate/n-hexane = 1:1:200 to 1:1:40).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA1504300), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22188101 and 22325103), the Haihe Laboratory of Sustainable Chemical Transformations and “Or Science Center for New Organic Matter”, Nankai University (63181206), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (63241529) and Tianjin Natural Science Foundation (23JCYBJC01570) for financial support.

Author contributions

X.G. developed the reaction and wrote the Supplementary Information. X.C. and M.L. performed part of the synthetic experiments and collected part of the data. Q.-L.Z. gave valuable advice. W.X. and M.Y. conceived the reaction and wrote the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Chi Wai Cheung, and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

For the experimental procedures and data of NMR, see Supplementary Methods in the Supplementary Information file. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 2379082. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Data supporting the findings of this study are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Weiwei Xu, Email: wwxu_chem@163.com.

Mengchun Ye, Email: mcye@nankai.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-59274-4.

References

- 1.Hussain, W. A. & Parasram, M. Recent advances in photoinduced oxidative cleavage of alkenes. Synthesis56, 1775–1786 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urgoitia, G., SanMartin, R., Herrero, M. T. & Domínguez, E. Aerobic cleavage of alkenes and alkynes into carbonyl and carboxyl compounds. ACS Catal.7, 3050–3060 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerenkan, A. E., Bélanda, F. & Do, T.-O. Chemically catalyzed oxidative cleavage of unsaturated fatty acids and their derivatives into valuable products for industrial applications: a review and perspective. Catal. Sci. Technol.6, 971–987 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajagopalan, A., Lara, M. & Kroutil, W. Oxidative alkene cleavage by chemical and enzymatic methods. Adv. Synth. Catal.355, 3321–3335 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biermann, U., Bornscheuer, U., Meier, M. A. R., Metzger, J. O. & Schäfer, H. J. Oils and fats as renewable raw materials in chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.50, 3854–3871 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corma, A., Iborra, S. & Velty, A. Chemical routes for the transformation of biomass into chemicals. Chem. Rev.107, 2411–2502 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caron, S., Dugger, R. W., Ruggeri, S. G., Ragan, J. A. & Ripin, D. H. B. Large-scale oxidations in the pharmaceutical industry. Chem. Rev.106, 2943–2989 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappo, R., Allen, D. S., Lemieux, R. U. & Johnson, W. S. Osmium tetroxide-catalyzed periodate oxidation of Olefinic bonds. Can. J. Chem.33, 478–479 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang, D. & Zhang, C. Ruthenium-catalyzed oxidative cleavage of alkenes to aldehydes. J. Org. Chem.14, 4814–4818 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Travis, B. R., Narayan, R. S. & Borhan, B. Osmium tetroxide-promoted catalytic oxidative cleavage of Olefins: An organometallic ozonolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.124, 3824–3825 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu, W., Mei, Y., Kang, Y., Hua, Z. & Jin, Z. Improved procedure for the oxidative cleavage of alkenes by OsO4–NaIO4. Org. Lett.6, 3217–3219 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolaou, K. C., Adsool, V. A. & Hale, C. R. H. An expedient procedure for the oxidative cleavage of Olefinic bonds with PhI(OAc)2, NMO, and catalytic OsO4. Org. Lett.12, 1552–1555 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroeder, M. Osmium tetraoxide cis hydroxylation of unsaturated substrates. Chem. Rev.80, 187–213 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fatiadi, A. J. The classical permanganate ion: still a novel oxidant in organic chemistry. Synthesis 85–127 10.1055/s-1987-27859 (1987).

- 15.Kolb, H. C., VanNieuwenhze, M. S. & Sharpless, K. B. Catalytic asymmetric dihydroxylation. Chem. Rev.94, 2483–2547 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh, N. & Lee, D. G. Permanganate: A green and versatile industrial oxidant. Org. Process Res. Dev.5, 599–603 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dash, S., Patel, S. & Mishra, B. K. Oxidation by permanganate: synthetic and mechanistic aspects. Tetrahedron65, 707–739 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achard, T. & Bellemin-Laponnaz, S. Recent advances on catalytic osmium‐free olefin syn‐dihydroxylation. Eur. J. Org. Chem.6, 877–896 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher, T. J. & Dussault, P. H. Alkene ozonolysis. Tetrahedron73, 4233–4258 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Ornum, S. G., Champeau, R. M. & Pariza, R. Ozonolysis applications in drug synthesis. Chem. Rev.106, 2990–3001 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Audran, G., Marque, S. R. A. & Santelli, M. Ozone, chemical reactivity, and biological functions. Tetrahedron74, 6221–6261 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailey, P. S. The reactions of ozone with organic compounds. Chem. Rev.58, 925–1010 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiber, S. L., Claus, R. E. & Reagan, J. Ozonolytic cleavage of cycloalkenes to terminally differentiated products. Tetrahedron Lett.23, 3867–3870 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smaligo, A. J. et al. Hydroalkenylative C(sp3)-C(sp2) bond fragmentation. Science364, 681–685 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoelderich, W. F. & Kollmer, F. Oxidation reactions in the synthesis of fine and intermediate chemicals using environmentally benign oxidants and the right reactor system. Pure Appl. Chem.72, 1273–1287 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Criegee, R. Mechanism of ozonolysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.14, 745–752 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welz, O. et al. Direct kinetic measurements of Criegee intermediate (CH2COO) formed by reaction of CH2I with O2. Science335, 204–207 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassan, Z., Stahlberger, M., Rosenbaum, N. & Bräse, S. Criegee intermediates beyond ozonolysis: synthetic and mechanistic insights. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.60, 15138–15152 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Splitter, J. S. & Calvin, M. The photochemical behavior of some o-nitrostilbenes. J. Org. Chem.20, 1086–1115 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchi, G. & Ayer, D. E. Light catalyzed organic reactions. IV. The oxidation of alkenes with nitrobenzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc.78, 689–690 (1956). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheinbaum, M. L. The photochemical reaction of nitrobenzene and tolane. J. Org. Chem.29, 2200–2203 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hurley, R. & Testa, A. C. Photochemical n → π* Excitation of Nitrobenzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc.88, 4330–4332 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weller, J. W., Hamilton, G. A. The photo-oxidation of alkanes by nitrobenzene. J. Chem. Soc. D Chem. Commun. 1390–1391 10.1039/C29700001390 (1970).

- 34.Mayo, P. D., Charlton, J. L. & Liao, C. C. Photochemical synthesis. XXXV. Addition of aromatic nitro compounds to alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.93, 2463–2471 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okada, K., Saito, Y. & Oda, M. Photochemical reaction of polynitrobenzenes with adamantylideneadamantane: the X-Ray structure analysis and chemical properties of the dispiro N-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)-l,3,2-dioxazolidine product. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 23, 1731–1732 (1992).

- 36.Lu, C. et al. Intramolecular reductive cyclization of o-Nitroarenes via biradical recombination. Org. Lett.21, 1438–1443 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruffoni, A., Hampton, C., Simonetti, M. & Leonori, D. Photoexcited nitroarenes for the oxidative cleavage of alkenes. Nature610, 81–86 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wise, D. E. et al. Photoinduced oxygen transfer using nitroarenes for the anaerobic cleavage of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 15437–15442 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, B., Ren, H., Cao, H.-J., Lu, C. & Yan, H. A switchable redox annulation of 2-nitroarylethanols affording N-heterocycles: photoexcited nitro as a multifunctional handle. Chem. Sci.13, 11074–11082 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arriaga, D. K. & Thomas, A. A. Capturing primary ozonides for a syn-dihydroxylation of olefins. Nat. Chem.15, 1262–1266 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hampton, C., Simonetti, M. & Leonori, D. Olefin dihydroxylation using nitroarenes as photoresponsive oxidants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202214508 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sánchez-Bento, R., Roure, B., Llaveria, J., Ruffoni, A. & Leonori, D. A strategy for ortho-phenylenediamines synthesis via dearomative-rearomative coupling of nitrobenzenes and amines. Chem.9, 3685–3695 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitchell, J. K. et al. Photoinduced nitroarenes as versatile anaerobic oxidants for accessing carbonyl and imine derivatives. Org. Lett.25, 6517–6521 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matador, E. et al. A Photochemical strategy for the conversion of nitroarenes into rigidified pyrrolidine analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 27810–27820 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paolillo, J. M., Duke, A. D., Gogarnoiu, E. S., Wise, D. E. & Parasram, M. Anaerobic hydroxylation of C(sp3)–H bonds enabled by the synergistic nature of photoexcited nitroarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 2794–2799 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mykura, R. et al. Synthesis of polysubstituted azepanes by dearomative ring expansion of nitroarenes. Nat. Chem.16, 771–779 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Göttemann, L. T., Wiesler, S. & Sarpong, R. Oxidative cleavage of ketoximes to ketones using photoexcited nitroarenes. Chem. Sci.15, 213–219 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teng, K., Liu, Q., Lv, J. & Li, T. The application of nitroarenes in catalyst-free photo-driven reactions. ChemPhotoChem.8, e202300236 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jana, R. & Pradhan, K. Shining light on the nitro group: distinct reactivity and selectivity. Chem. Commun.60, 8806–8823 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gkizis, P. L., Triandafillidi, L. & Kokotos, C. G. Nitroarenes: The rediscovery of their photochemistry opens new avenues in organic synthesis. Chem.9, 3401–3414 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wise, D. E. & Parasram, M. Photoexcited nitroarenes as anaerobic oxygen atom transfer reagents. Synthesis34, 1655–1661 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu, X. et al. Photooxidation of polyolefins to produce materials with In-ChainKetones and improved materials properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.63, e202418411 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qin, H. Y. et al. Photoinduced bartoli indole synthesis by the oxidative cleavage of alkenes with nitro(hetero)arenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.63, e202416923 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cui, R. et al. Metal and photocatalyst-free amide synthesis via decarbonylative condensation of alkynes and photoexcited nitroarenes. Org. Lett.26, 8222–8227 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang, H., Jiang, Y., Yuan, W. & Lin, Y.-M. Modular assembly of acridines by integrating photo-excitation o-alkyl nitroarenes with copper-promoted cascade annulation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.63, e202409653 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paolillo, J. M., Saleh, M. R., Junk, E. W. & Parasram, M. Merging photoexcited nitroarenes with Lewis acid catalysis for the anaerobic oxidation of alkenes. Org. Lett.27, 2011–2015 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li, M. et al. Visible light-mediated [1 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction of nitroarenes and alkenes. Org. Chem. Front.12, 636–640 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berthet, M., Cheviet, T., Dujardin, G., Parrot, I. & Martinez, J. Isoxazolidine: a privileged scaffold for organic and medicinal chemistry. Chem. Rev.116, 15235–15283 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chiacchio, M. A., Giofrè, S. V., Romeo, R. & Chiacchio, U. Isoxazolidines as biologically active compounds. Curr. Org. Synth.13, 726–749 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

For the experimental procedures and data of NMR, see Supplementary Methods in the Supplementary Information file. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 2379082. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Data supporting the findings of this study are also available from the corresponding author upon request.