Abstract

Background

Emergency department (ED) overcrowding and boarding has been shown to have negative effects on patient care. However, there has been less focus on the effects of overcrowding and boarding on resident education.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review to map the current literature on the educational effects of ED overcrowding, summarizing the current research findings and identifying gaps for future research. We sought to answer (1) How is overcrowding defined by individual studies? (2) What educational outcomes have been studied in overcrowding and how have they been measured? (3) What are the educational effects of physician‐in‐triage (PIT) care models? (4) What educational responses have been initiated in response to ED overcrowding? and (5) What are the effects of those educational responses? We searched Medline, Embase, ERIC, MedEdPortal, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Two authors independently extracted data. All authors performed quantitative and qualitative synthesis, consistent with best practice recommendations for scoping reviews.

Results

The initial search strategy identified 2570 articles, with 14 articles meeting inclusion criteria. The literature found perceptions of a negative impact of overcrowding and boarding on resident education. However, these negative perceptions have not consistently translated to demonstrably negative educational outcomes. Educational outcomes assessed include measures of resident productivity, procedural experience, in‐training examination scores, and perceived measures of teaching quality and educational value. Several studies assessed the impact of PIT models finding changes in the type and volume of patients seen by residents as a result.

Conclusions

This scoping review summarizes the existing literature assessing the educational impact of ED overcrowding and boarding as well as PIT models. The review provides context and insights for future research into these effects.

INTRODUCTION

Emergency department (ED) overcrowding occurs when existing patients in an ED saturate the capacities of the department, compromising the ability of the ED to deliver care to new patients presenting with emergent medical conditions. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 The causes of ED overcrowding are multifactorial and include high volumes of patients arriving to EDs, ED throughput, and the flow of patients out of the ED and into inpatient care spaces. 5 Morley et al. 6 conducted a systematic review looking into the causes and effects of ED overcrowding. They identified numerous high‐quality studies demonstrating negative effects on patient care including increased exposure to medical errors, delays in care, increased risk of readmission, increased inpatient length of stay, and increased inpatient mortality. Studies also identified negative effects on ED staff including increased violence against medical providers, increased stress, and nonadherence to best practice guidelines. This systematic review, however, did not explore the potential negative effects of ED overcrowding on resident education and training.

Heins et al. 7 were first to examine the literature looking for studies on the effects of ED overcrowding on the educational environment of the ED. Their 2005 commentary found no studies on the effect of ED crowding on educational outcomes. In the same year, Atzema et al. 8 published a resident perspective piece hypothesizing that ED crowding leads to decreased time for attending physician supervision and bedside teaching, potentially threatening the educational environment of the ED. Subsequently in 2008, Shayne et al., 9 as part of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Crowding Taskforce Education Workgroup, expanded on the reported search strategy of Heins et al. and identified two prospective studies based in the ED that reported perceived teaching quality was independent of ED census, clinician‐educator workload, and relative value units. Both the Heins paper and the Shayne paper asserted the need for additional research into the effects of ED overcrowding on the educational environment with Shayne et al. hypothesizing a number of possible positive and negative effects of ED overcrowding.

Since the published commentaries of Heins and Shayne, several new studies looking into the effects of ED overcrowding on educational outcomes have been published. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 These studies explored different educational outcomes and used varied measures of ED overcrowding. The effects they reported also varied from positive to neutral to negative. Several of these studies also explored the educational effects of operational responses to ED overcrowding (e.g., physicians in triage [PIT]), which were not addressed in prior reviews. 12 , 15 Given the presence of several new studies looking at the effect of ED overcrowding on educational outcomes, a scoping review of the literature is needed to contextualize the results of these studies, identify themes, and propose future research studies. The objective of this scoping review is to map and find gaps in existing literature examining the impact of ED overcrowding on resident education as well as the literature exploring the educational impact of PIT care models.

METHODS

We performed a scoping review to map the current literature on the educational effects of ED overcrowding, summarizing the current research findings and identifying gaps for future research. We followed best practice guidelines and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 We followed the six stages as defined by Levac et al.: 17 (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results; and (6) consultation.

Identifying the research question

The overarching purpose of this review was to map the current literature on the educational effects of ED overcrowding to inform current practices and identify gaps requiring future research. To address these goals, we sought to answer the following questions: (1) How is overcrowding defined by individual studies? (2) What educational outcomes have been studied in overcrowding and how have they been measured? (3) What are the educational effects of PIT care models? (4) What educational responses have been initiated in response to ED overcrowding? and (5) What are the effects of those educational responses?

Identifying relevant studies

In conjunction with an experienced medical librarian, we conducted a search of Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Web of Science (Clarivate), ERIC (ProQuest), MedEdPortal, and Google Scholar without restrictions on date. We filtered by human studies and English‐language studies. We used a comprehensive search strategy with both controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH terms) and keywords. The search strategy is available in Appendix S1. We also reviewed the bibliographies of identified studies and reviewed articles for potential missed articles. We consulted topic experts to help identify any further relevant studies.

Study selection

We included studies that assessed the effect of ED overcrowding on education in graduate medical education. Studies had to be original research articles. We excluded articles that did not assess the effect of overcrowding on resident education, that did not assess original research (e.g., systematic reviews, perspective, or commentary articles), were conducted outside of the United States or Canada, and that were not published in English. We chose to include only studies conducted in the United States and Canada as the two countries share roughly similar residency training models. Two investigators (JM and GH) independently evaluated titles and abstracts of studies for eligibility based on the above criteria. These investigators met regularly and discussed inclusion and exclusion criteria to clarify any issues or ambiguities as they arose. All abstracts meeting initial inclusion criteria were downloaded and reviewed as full‐text manuscripts. If there were disagreements about inclusion at the abstract screening stage, the article was selected for full‐text review. Two investigators (JM and GH) independently assessed manuscripts for inclusion in the final data analysis. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus with the addition of a third reviewer (JH) if needed.

Charting the data

We utilized the “descriptive‐analytic” model described by Arksey and O'Malley to guide data extraction and summarization. 16 Prior to data extraction, a database was constructed with all authors agreeing on the discrete data elements to be extracted from each paper (see Appendix S2). Two investigators (JH and JS) independently extracted data from the included studies. Before fully extracting all included papers, the investigators extracted a sample data set and then met to discuss and resolve discrepancies. Additionally, during the data extraction process, these investigators met regularly to clarify any issues or ambiguities as they arose.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

We synthesized and collated the data, performing both quantitative and qualitative analyses. For the quantitative portion, we have provided a descriptive summary of the extent, nature, and distribution of the studies included in this review. For the qualitative synthesis, we provided a narrative summary of the information addressing our study questions, identifying the current state of knowledge with an emphasis on the broader application of the findings and directions for future research as recommended by Levac et al. 17 This involved reviewing the key components of each study identified previously through charting of the data and then engaging in iterative discussions to arrive at consensus regarding the summative findings aligned with the research questions.

Consultation

We sought external consultation from physicians and physicians‐in‐training at various stages in their career to ensure that we identified the key literature and interpreted it appropriately. Our consultant group included those with expertise in residency education, operations, and resident physicians. With their feedback, we strengthened our discussion to highlight the downsides of using on‐shift teaching evaluations as an educational outcome measure and added additional specificity to proposed future research questions in our conclusion.

RESULTS

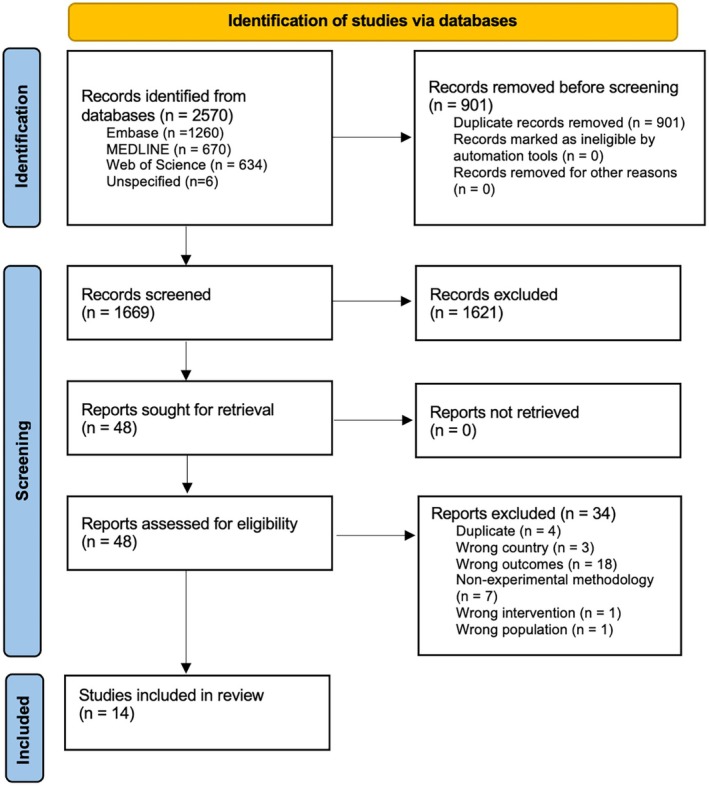

Our initial search strategy identified 2570 articles with 901 articles identified as duplicates, leaving 1669 articles for analysis (Figure 1). We screened titles and abstracts of these 1669 articles, excluding 1621 articles that did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. Forty‐eight articles underwent full‐text review. Of these 48 articles, 34 were excluded for assessing the wrong outcomes (n = 18), nonexperimental methodology (n = 7), wrong country (n = 3), duplication (n = 4), wrong intervention (n = 1), and wrong patient population (n = 1). This left 14 articles (11 full text and three abstracts) with experimental methodologies directly assessing the educational impact of overcrowding and/or the educational impact of operational responses to overcrowding. Of note, no studies examined educational interventions designed to mitigate the impact of overcrowding on trainee education.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study identification and review.

Of the 14 included studies, 10 were conducted at U.S. institutions, two were conducted at Canadian institutions, one was a U.S.‐wide survey of EM residencies, and one did not report location information. Of the 10 U.S.‐based studies with location data, six were performed on the East Coast (PA, NC, VA, NJ, MA), two in the South (TX, LA), one Midwest (IA), and one West Coast (CA). Of studies providing information regarding residency affiliation (n = 12), two were from 4‐year programs. The study periods for the included papers span from 2007 to 2023. A detailed description of the included studies is available in Appendix S2.

Defining overcrowding

Definitions of overcrowding varied significantly between papers. Most studies used a combination of subjective perceptions of how crowded a given shift was and some objective measure(s) of overcrowding. The National ED Overcrowding Study (NEDOCS) score was used in two papers. 13 , 21 The NEDOCS score is calculated based on the number of ED beds, number of hospital beds, total number of patients in the ED, number of patients on ventilators in the ED, number of admits in the ED, the longest waiting time for an admitted patient, and the longest waiting time for a waiting room patient. 22 The resulting score from this calculation allows the user to describe the level of crowding in an ED along a spectrum from not busy (0–20) to busy (20–60), extremely busy but not overcrowded (60–100), overcrowded (100–140), severely overcrowded (140–180), and dangerously overcrowded (>180). Other objective measures of overcrowding used in the included studies were EMS diversion time, 14 number of patients in the waiting room, ED occupancy as a percentage of ED treatment beds, number of admitted boarders, total patient care hours for all patients in the ED at a given time, and ED length of stay for all patients. 10 , 23

Through these measures, most of the papers sought to view overcrowding through a global lens, seeking to describe how crowded or overcrowded an ED was in general. Two papers, however, sought to define crowding through the lens of its impact on the time available for attendings to teach in the ED. 23 , 24 Atzema et al. 23 defined a crowded ED as one where the physician perceived the ED to be crowded and where they felt they were busy managing the ED. In that study, a shift that was perceived to be busy but where there were no beds to see patients was defined as “not crowded.” Atzema et al. 23 found this perception of crowding correlated with total ED LOS for all patients in a given shift. In contrast, several papers looked specifically at the negative impacts of boarding, which was described through varying measures of patients remaining in the ED after admission. 21 , 25 , 26 These papers view the educational impact of overcrowding through a lens of lost educational opportunities due to fewer patients being available to be seen by trainees.

Perceptions of impact on resident education

Several papers looked to assess the perceived impact of boarding and overcrowding on resident education. 25 , 27 Most recently, Goldflam et al. 25 conducted a survey of U.S. EM program directors gathering data on the perceived impact of boarding on resident education. Out of 161 responding program directors, they found that 65% felt boarding impacted resident education at least moderately, with 80% stating the impact on resident education was negative. The majority of program directors thought boarding negatively impacted a residents' ability to manage ED throughput/flow (70%), manage high volumes of patients per resident (66%), and manage the initial workup of undifferentiated patients (54%). 25 A 2009 cross‐discipline survey of residents at McGill University in Canada found that residents had a similar perspective on the impact of overcrowding on their education. 27 This study had several limitations including poor response rate (21%), incompletely described survey methodologies, and a single‐center survey population. However, 70% of responding residents felt overcrowding had a moderate to large negative impact on their training.

The papers by Goldflam et al. and Sabbah 27 represent program directors' and trainees' perspectives on resident education and training removed from the immediacy of the on‐shift educational experience. They found clear perceptions of a negative impact of overcrowding and boarding on resident education. Those findings, however, are inconsistent with studies that assessed perceptions of teaching and quality of education soon after clinical shifts. 10 , 11 , 14 , 24 Three studies used end‐of‐shift or end‐of‐encounter surveys to assess perceived teaching quality and educational value. 10 , 11 , 14 In each of these studies, ratings of educational value and perceived teaching quality did not correlate with perceived or objective measures of overcrowding. Kelly et al. 24 conducted a prospective, observational study assessing the relationship between resident perceived quality of teaching and attending clinical workload (as assessed by actual patient volume and perceived workload). They found no correlation of overall teaching scores and actual patient volume though did find a weak negative correlation between the attending perception of workload and overall teaching scores.

Impact on procedural volume

Three studies assessed the impact of overcrowding and boarding on resident procedural volume. 14 , 21 , 23 Atzema et al. 23 conducted a single‐center prospective observational study looking at the number of procedures offered to trainees and the number of procedures “given away” to consulting services during ED crowding. Using a definition of overcrowding focusing on the teaching bandwidth of attendings, they found no significant change in the mean number of procedures performed by trainees during ED overcrowding. However, they did find a significant number of procedures given away to consulting services during times of perceived crowding.

Conversely, studies by Wubben et al. 21 and Mahler et al. 14 did show negative impacts on the number of procedures performed by residents during ED overcrowding. Mahler et al. found the median number of procedures performed per shift decreased from 1.3 (95% CI 1–1.6) on nonovercrowded shifts to 0.9 (95% CI 0.6–1.2) on overcrowded shifts (defined as >2 h of EMS diversion). Wubben et al. 21 performed a retrospective study looking at the number of point‐of‐care ultrasounds (USs) performed on scanning shifts correlated with averaged scanning shift NEDOCS score and cumulative boarding hours during scanning shifts. Controlling for availability of US device and scanning shift characteristics, they found the mean NEDOCS score was significantly associated with decreased odds of successfully completing a scanning shift goals. When the mean NEDOCS score was >180, residents were able to obtain >14 scans <5% of the time. All the included studies provided data on the number of procedures performed in crowded versus noncrowded states but not on the types of procedures performed.

Impact on resident patient care opportunities

Three studies investigated the effects of overcrowding and boarding on resident patient volume and productivity. 13 , 14 , 26 Two of these studies found a negative impact of overcrowding and boarding on resident productivity. Mahler et al., using >2 h of EMS diversion as the definition of overcrowding, found residents reported seeing 1.6 fewer patients per shift on overcrowded shifts compared to nonovercrowded shifts. Moffett et al. 26 conducted a retrospective observational study over 4 years investigating the effect of hospital boarding on resident productivity (defined as patients seen per hour). Using a multivariable mixed model, they found that for every 100 additional hours of patient boarding, the number of patients residents saw per hour decreased by 0.022. They estimated, based on their median daily patient boarding of 261 h, that the elimination of boarding could result in 57.4 more patients seen per year per resident. Kirby et al. 13 also conducted a single‐center retrospective chart review over a 3‐year period of time looking at the effect of ED crowding on resident productivity. They found that the number of new patients seen per hour per resident increased from not crowded (NEDOCS <100) to “crowded” (NEDOCS 100–140) states. Productivity also increased comparing crowded (NEDOCS 100–140) to “overcrowded” (NEDOCS >140) states, though the increase in productivity was smaller suggesting a plateau of productivity in an overcrowded ED.

Impact of PIT on resident education

There were four studies that assessed the educational impact of PIT models. 12 , 15 , 28 , 29 PIT models are designed to improve patient flow, decrease left‐without‐being‐seen rates, and improve ED LOS. 30 , 31 In all of the included studies the PIT models implemented involved attending EM physicians. Resident physicians were not involved in the PIT processes in any of the included papers. In one paper, the PIT process was applied only to patients arriving by EMS. 29 In the remaining papers, the PIT models applied to all patients presenting to triage. 12 , 15 , 28 Two of these studies used retrospective chart reviews to assess the impact of the introduction of PIT on resident productivity. 12 , 28 Lovett et al. 28 found no difference in patients seen per hour by residents following the introduction of an attending in triage model, though their results were confounded by a simultaneous increase in ED volume observed during the study period. Jen et al. 12 found that the average number of patients per hour seen by residents slightly decreased following implementation (1.41–1.32, p < 0.01, 95% CI 0.05–0.13). They also found that the acuity of patients seen by residents increased following implementation of PIT, with the mean Emergency Severity Index score of patients seen decreasing from 3.0 to 2.68. Studies by Nicks et al. 15 and Ullo et al. 29 used survey methodologies to assess the perceived impact of PIT on the resident educational experience. In both of these studies, attendings and residents did not perceive an impact of the introduction of PIT on their overall educational experience. However, both studies found perceived negative impacts on medical knowledge, medical decision making, ability to generate differential diagnoses, and resident selection of diagnostics studies. These papers did not report data on the ordering practices of residents before and after the introduction of PIT or the types of labs and diagnostics studies done in PIT or offer a detailed look at the type of patients seen and discharged through PIT.

DISCUSSION

In this scoping review, we identified multiple studies examining the educational impact of boarding and overcrowding and studies examining the educational impact of PIT models used as a response to ED overcrowding. Of the studies included in this review, most looked to assess the impact of “ED overcrowding” instead of specifically assessing the impact of “ED boarding.” This is consistent with the framework established by Shayne et al. 9 However, this framework may be problematic. An overcrowded ED could be an ED bursting at the seams with active patients and no boarding. It is possible that in this version of an overcrowded ED the resident educational experience is improved; more patient encounters mean exposure to more breadth of pathophysiology, more procedural opportunities, and opportunities to manage multiple patients at once. It is also possible in this version of an overcrowded ED that the resident educational experience is harmed: less time for supervising physicians to teach, less time to solidify knowledge around disease processes, and less time to perform procedures. A “boarded” ED, however, is a version of an overcrowded ED that theoretically results in negative educational outcomes due to inpatient boarders creating an “educational dead space.” Beds that should have active patients for ED providers to see are filled instead by patients who have had their ED care completed and whose management is typically the responsibility of inpatient teams. This effectively shrinks the size of the ED, decreasing the number of patients residents are able to see, potentially decreasing procedural opportunities, and potentially decreasing opportunities for the simultaneous management of large volumes of patients. Both of these hypothetical overcrowded EDs could have equivalent NEDOCS scores but the ED with more inpatient boarders and more educational “dead space” is theoretically more likely to have a negative effect on the educational environment.

As we see in the published literature, the few studies that looked specifically at boarding consistently described negative educational outcomes (both perceived and objective). 21 , 25 , 26 Studies that looked at ED overcrowding in general had inconsistent signals of neutral or negative educational impacts. This is potentially due to the variable ways in which overcrowding was reported but it is also possible that the negative educational impacts of overcrowding are most detectable when more severe levels of overcrowding are present. For instance, Kirby et al. 13 found increases in resident productivity with increasing NEDOCS, but only 32% of the patients in their retrospective review arrived when NEDOCS was >140. This is in contrast to Wubben et al. where the mean NEDOCS for the entire study period was 157.4 and 23.2% of their US scanning shifts had a NEDOCS >180. 21 Future studies should seek to further investigate the specific educational effects of inpatients boarding in the ED separate from, and in addition to, other markers of overcrowding. Additionally future research should identify measures of overcrowding that correlate with educational outcomes and adequately report the severity of overcrowding and boarding in their study population.

There were a variety of educational outcomes assessed in the studies found in our review: knowledge‐based outcomes such as in‐training examination (ITE) scores, operational outcomes such as number of patients seen and USs/procedures performed, and perceptions of teaching quality and educational experience. Program directors perceive that boarding has a significant negative educational impact on residents ability to manage ED flow, manage multiple patients, and approach the undifferentiated patient. 25 Some of the published studies found decreases in patients seen by residents but further studies are needed to better characterize the loss of patient volume as a result of boarding and severe overcrowding. 14 , 26 Studies that used shift evaluations or assessments of teaching quality and educational value tended to find no differences in overcrowded ED environments. 10 , 11 , 14 , 24 These outcomes may be more representative of evaluators feelings toward an attending or could reflect an increase in explicit teaching (e.g., chalk talks) during downtime rather than a reflection of the functional educational environment of an ED (i.e., opportunities to see and evaluate patients, perform procedures). Individual institutional cultural differences may play a role here as well. For example, if a residency training program emphasizes knowledge acquisition through didactic experiences as opposed to experiential learning, they may be less likely to report negative educational impacts of ED overcrowding. Shift evaluation/teaching assessment outcomes also reflect point‐in‐time measurements and may miss the cumulative effects of seeing slightly fewer patients per shift and performing slightly fewer procedures per shift over the course of one's residency training. Additional research is needed to investigate how a resident's ability to manage ED flow and multiple simultaneous patient encounters is affected by boarding and severe overcrowding. Future studies could also seek to examine the impact of boarding, overcrowding, residency productivity, and procedural volume on longer term measures of trainee success (e.g., board passage rate, instances of remediation, peer review cases, malpractice claims).

Studies assessing the educational impact of PIT models have been limited by confounding factors, retrospective methods, and their single‐center nature. The studies that have been done found perceived negative impacts on resident medical decision making, differential diagnosis formation, and diagnostic test selection along with impacts on the number and acuity of patients seen by residents. These findings are echoed in program director concerns that the current state of boarding negatively impacts a residents' ability to approach the undifferentiated patient. 25 Further study into these impacts is warranted to better assess the ways in which residents cognitively approach and process undifferentiated patients as well as patients who have been through a PIT process. Additionally, the studies that have looked at the impact of PIT models have only assessed models with attending PIT. There were no studies assessing how having nonphysician practitioners (nurse practitioners or physician assistants) in triage impacts resident education. Finally, there were no studies assessing the integration of residents into a PIT model. The feasibility, benefits, and potential harms of a resident in triage model are unanswered questions.

Though the published literature suggests perceived and, sometimes, measurable negative impacts of ED overcrowding and boarding on resident education, we were unable to identify any studies assessing educational responses to ED overcrowding. This represents a gap in the literature and future studies should assess the role of curricula or combined educational/operational interventions designed to address the negative educational environment of an overcrowded or boarded ED.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations with this scoping review. First, we excluded studies that were not published in English and that occurred outside of the United States and Canada. This was done intentionally to exclude resident training systems and healthcare systems with significant differences to the United States and Canada. ED overcrowding and boarding is, however, an international problem and there may be literature examining the educational effects in those geographic regions not represented in this scoping review. 1 Second, we did not examine the impact of ED overcrowding and boarding on medical student or other health professional education. Many of the educational effects identified in this scoping review (decreases in patients available to be seen, decreases in procedural exposure) may translate to other learner groups who train in the ED. There may also be educational impacts unique to those learner groups not explored in this review.

CONCLUSIONS

We performed a scoping review of the literature assessing the educational impact of overcrowding and boarding on resident education as well as the educational impact of physicians in triage models. There is a strong perception that boarding and overcrowding negatively impact the resident training experience but studies looking directly at the educational impact of boarding and overcrowding have either shown no impact on educational outcomes or modest negative outcomes. However, the published studies are limited by single center methodologies. They have not adequately investigated the specific impacts of inpatient boarding (separate from overcrowding in general), and with few exceptions, they have not assessed the educational impacts at the most severe levels of overcrowding (e.g., National ED Overcrowding Study >180). Future investigators should seek to measure the educational impact of boarding and severe overcrowding by looking more deeply at the resident patient care experience. How many and what type of patient care opportunities do residents have? What are their procedural opportunities? How are opportunities to evaluate undifferentiated patients affected? How are opportunities to manage multiple patients simultaneously affected? Additionally, multicenter studies are needed to assess how site‐specific operational variables may affect these outcomes and to provide a more reliable measure of the educational impact of severe overcrowding, the boarding of inpatients in ED care spaces, and PIT models.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix S1.

Appendix S2.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the contributions of our consultants in adding to and refining our understanding of the impact of this literature base. We thank Alex Sheng, MD MPHE, Program Director, Brown University; Peter Moffett, MD, Program Director, Virginia Commonwealth University; Rebecca Bavolek, MD, FACEP, Program Director, UCLA; Emily Cloessner, MD, PGY‐3, Chief Resident, Washington University; Haley Plattner, MD, PGY‐3 Rush University; Rohit Anand, MD, PGY‐3, Emory University; Grace Lagasse, MD, Medical Director, University of South Alabama; and Hamza Ijaz, MD, Operations Fellow, Cornell University.

Hill J, Hickam G, Shaw J, et al. The effects of overcrowding, boarding, and physician‐in‐triage on resident education: A scoping review. AEM Educ Train. 2025;9:e70040. doi: 10.1002/aet2.70040

Supervising Editor: Jason Wagner

REFERENCES

- 1. Somma SD, Paladino L, Vaughan L, Lalle I, Magrini L, Magnanti M. Overcrowding in emergency department: an international issue. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(2):171‐175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kelen GD, Wolfe R, D'Onofrio G, et al. Emergency department crowding: the canary in the health care system. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2021;2:1‐26. doi: 10.1056/CAT.21.0217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Salway R, Valenzuela R, Shoenberger J, Mallon W, Viccellio A. Emergency department (ED) overcrowding: evidence‐based answers to frequently asked questions. Rev Médica Clínica Las Condes. 2017;28(2):213‐219. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sartini M, Carbone A, Demartini A, et al. Overcrowding in emergency department: causes, consequences, and solutions—a narrative review. Healthcare. 2022;10(9):1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asplin BR, Magid DJ, Rhodes KV, Solberg LI, Lurie N, Camargo CA. A conceptual model of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(2):173‐180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morley C, Unwin M, Peterson GM, Stankovich J, Kinsman L. Emergency department crowding: a systematic review of causes, consequences and solutions. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0203316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heins A, Farley H, Maddow C, Williams A. A research agenda for studying the effect of emergency department crowding on clinical education. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(6):529‐532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Atzema C, Bandiera G, Schull MJ, Coon TP, Milling TJ. Emergency department crowding: the effect on resident education. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(3):276‐281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shayne P, Lin M, Ufberg JW, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on education: blessing or curse? Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):76‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pines JM, Prabhu A, McCusker CM, Hollander JE. The effect of ED crowding on education. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(2):217‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoxhaj S, Moseley MG, Fisher A, O'Connor RE. Resident education does not correlate with the degree of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(4):S77. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jen M, Goubert R, Toohey S, Zuabi N, Wray A. Triage physicians in an academic emergency department: impact on resident education. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(3):e10567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kirby R, Robinson RD, Dib S, et al. Emergency medicine resident efficiency and emergency department crowding. Aem Educ Train. 2019;3(3):209‐217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mahler SA, McCartney JR, Swoboda TK, Yorek L, Arnold TC. The impact of emergency department overcrowding on resident education. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(1):69‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nicks BA, Mahler S, Manthey D. Impact of a physician‐in‐triage process on resident education. West J Emerg Med: Integrating Emerg Care Popul Heal. 2014;15(7):902‐907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19‐32. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thomas A, Lubarsky S, Durning SJ, Young ME. Knowledge syntheses in medical education: demystifying scoping reviews. Acad Med. 2017;92(2):161‐166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gottlieb M, Haas MRC, Daniel M, Chan TM. The scoping review: a flexible, inclusive, and iterative approach to knowledge synthesis. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(3):e10609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wubben BM, Chmielewski N, Heukelom PV, Wittrock C. The impact of emergency department crowding and patient boarding on resident point‐of‐care ultrasound education. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2024;5(3):e13220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weiss SJ, Derlet R, Arndahl J, et al. Estimating the degree of emergency department overcrowding in academic medical centers: results of the national ED overcrowding study (NEDOCS). Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(1):38‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Atzema CL, Stefan RA, Saskin R, Michlik G, Austin PC. Does ED crowding decrease the number of procedures a physician in training performs? A prospective observational study. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(9):1743‐1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kelly SP, Shapiro N, Woodruff M, Corrigan K, Sanchez LD, Wolfe RE. The effects of clinical workload on teaching in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(6):526‐531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goldflam K, Bradby C, Coughlin RF, et al. Is boarding compromising our residents' education? A national survey of emergency medicine program directors. AEM Educ Train. 2024;8(2):e10973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moffett P, Barrera L, Hickam G, et al. The effect of hospital boarding on emergency medicine resident productivity. West J Emerg Med: Integrating Emerg Care Popul Heal. 2024;26(1):S2–S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sabbah S. The impact of hospital overcrowding on postgraduate education: an emergency medicine resident's perspective through the lens of CanMEDS. CJEM. 2009;11(3):247‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lovett PB, Kahn JA, Davis‐Moon L, Mathew RG, Randolph FT, Lopez BL. Attending in triage: impact on resident experience. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(suppl 1):S250. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ullo M, Alexander A, Sugalski G. Perceived impact of physician‐in‐triage on resident education. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(6):1208‐1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Han JH, France DJ, Levin SR, Jones ID, Storrow AB, Aronsky D. The effect of physician triage on emergency department length of stay. J Emerg Med. 2010;39(2):227‐233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Partovi SN, Nelson BK, Bryan ED, Walsh MJ. Faculty triage shortens emergency department length of stay. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(10):990‐995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1.

Appendix S2.