Abstract

Background

Social media listening is a new approach for gathering insights from social media platforms about users’ experiences. This approach has not been applied to analyse discussions about Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in China.

Aims

We aimed to leverage multisource Chinese data to gain deeper insights into the current state of the daily management of Chinese patients with AD and the burdens faced by their caregivers.

Methods

We searched nine mainstream public online platforms in China from September 2010 to March 2024. Natural language processing tools were used to identify patients and caregivers, and categorise patients by disease stage for further analysis. We analysed the current state of patient daily management, including diagnosis and treatment, choice of treatment scenarios, patient safety and caregiver concerns.

Results

A total of 1211 patients with AD (66% female, 82% aged 60–90) and 756 caregivers for patients with AD were identified from 107 556 online sources. Most patients were derived from online consultation platforms (43%), followed by bulletin board system platforms (24%). Among the patients categorised into specific disease stages (n=382), 42% were in the moderate stage. The most frequent diagnostic tools included medical history (97%) and symptoms (84%). Treatment options for patients with AD primarily included cholinesterase inhibitors, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists and antipsychotics. Both quantitative and qualitative analysis of patients who experienced wandering (n=92) indicated a higher incidence of wandering during the moderate stage of the disease. Most caregivers were family members, with their primary concerns focusing on disease management and treatment (90%), followed by daily life care (37%) and psychosocial support (25%).

Conclusions

Online platform data provide a broad spectrum of real-world insights into individuals affected by AD in China. This study enhances our understanding of the experiences of patients with AD and their caregivers, providing guidance for developing personalised interventions, providing advice for caregivers and improving care for patients with AD.

Keywords: cognition disorders

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Our research aimed to leverage multisource Chinese data to gain deeper insights into the current state of the daily management of Chinese patients with AD and the burdens faced by their caregivers.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This research innovatively used online data to explore the experiences and challenges faced by patients with AD and their caregivers.

The findings resonated with previous studies on diagnostic methods and treatment choices, addressing a research gap by quantifying incidents of wandering among patients with AD.

Introduction

From 1980 to 2020, the population of individuals aged 60 years and above in China surged, rising from 6.9% to 18.7% of adults.1 This profound ageing of China’s population has been paralleled by a persistent and alarming increase in the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The China AD Report states that in 2019, 13.1 million people in China were affected by AD and related dementia, with a higher prevalence and mortality rate than the global averages,2 highlighting the severity of the issue. However, AD prevention and management in China face numerous challenges. First, patients with AD experience suboptimal diagnostic and treatment rates, with a particularly alarming underdiagnosis rate exceeding 90% in rural areas.3 Furthermore, a large proportion of individuals with dementia in China remain untreated with pharmacological interventions.4 Additionally, current treatments are insufficient to achieve satisfactory clinical outcomes or halt disease progression. Access to professional care is limited, and most patients with AD rely on informal home-based care.5 The lack of effective treatments and inadequate care systems place a significant financial and psychological burden on caregivers, affecting their well-being and the quality of care they provide.6

Social media listening (SML) is a new approach to harnessing information derived from social media platforms to generate insights into users’ experiences.7 In addressing AD prevention and management challenges in China, SML has emerged as a promising tool, leveraging web data to aid dementia care by generating and analysing vast datasets, and offering real-time patient perspectives.8 SML streamlines the time-consuming process of patient recruitment, accelerates research and minimises recall biases.9 By capturing diverse experiences not typically reflected in clinical trials or patient preference studies, SML ensures a more comprehensive understanding of dementia care.10 This unbiased assessment of patient perspectives complements traditional research methods, fostering effective, patient-centred strategies. While previous studies have focused on patients with AD on international platforms like YouTube, Twitter and Facebook, these are less accessible in China.11 12 However, the widespread access to the internet and mobile applications allows patients in China to easily obtain medical advice and consultations, regardless of their geographical location. As the integration of blockchain technology and artificial intelligence progresses, natural language processing (NLP) can classify the mood and tone in text to help identify and alleviate psychological stress experienced by patients with AD, enhance their mood and reduce loneliness, offering real-world insights into their burdens.12

To date, existing literature on SML for Chinese patients with AD is sparse. This lack of research represents a significant gap in our understanding of this vulnerable population, as their voices and perspectives are crucial for developing effective healthcare strategies. By analysing the experiences of Chinese patients with AD and their caregivers, we aimed to gain insights into diagnosis, treatment and management features including caregiver experiences and issues such as wandering, to inform AD market development. We also seek to use advanced NLP technology, such as large language models (LLMs), to understand the feelings and unmet needs of Chinese patients with AD.

Methods

Data source and collection

We collected multisource data from various major online platforms in China, including online consultation platforms (Haodaifu, Chunyu Doctor), e-commerce platforms (Tmall, JD.com), bulletin board system (BBS) platforms (Weibo, WeChat) and social media platforms (Douyin, Kuaishou, Xiaohongshu) (figure 1). We used AD-related keywords, such as “Alzheimer” (阿尔茨海默), “AD”, “Alzheimer Disease”, “Senile dementia” (老年痴呆), “dementia” (认知症), “cognitive impairment” (认知障碍), “NMDA receptor antagonists” (NMDA 受体拮抗剂), “glutamate receptor antagonists” (谷氨酸受体拮抗剂), “cholinesterase inhibitors” (胆碱酯酶抑制剂), to collect information. Data collection spans from September 2010 to March 2024, with adjustments made for the platforms’ available history. Considering some platforms became publicly accessible from 2016 (BBS) or 2017 (e-commerce), and some social media sites emerged in recent years, we collected all historical data from these newer social media sites.

Figure 1. Flowchart of stakeholder identification and platform type from which online text was extracted. *Patient information was identified first, and caregiver information was then extracted from the patient-related text based on whether the caregiver perspective exists. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; BBS, bulletin board system.

Ethical considerations

All data used and presented in this study were obtained from publicly accessible sources without accessing password-protected information. Patients’ privacy was respected, and online content was anonymised in compliance with data privacy obligations. No individual patient data requiring consent has been presented.

Data extraction and analysis

Given the colloquial language used by patients, traditional methods are challenging. Therefore, we used various NLP tools to process and analyse text (figure 2). Named-entity recognition (NER) is a subtask of NLP that involves identifying and classifying named entities in text, such as names of people, organisations and locations. In this study, we used the ‘knowledge mining’ interface from PaddleNLP (https://github.com/PaddlePaddle/PaddleNLP) to find self-defined types of entities from text. For example, NER can identify and categorise symptoms, medication names, dosages and patient outcomes. It segments sentences into words and determines their types, allowing us to select necessary labels for each analytical dimension to examine the original content mentioned by patients, such as identifying ‘AD’ under the ‘disease category’ or ‘donepezil’ under the ‘drug category’. In this study, we extracted entities including people, roles, symptoms, medicine and other related items from the text. Meanwhile, we used pkuseg (https://github.com/lancopku/pkuseg-python), a commonly used tokeniser for Chinese, for multidomain word segmentation. LLMs are computational models known for their capacity in general-purpose language generation and NLP tasks.13 In this study, we used generative pretrained transformer 4 (GPT-4) (https://openai.com/gpt-4), a renowned LLM developed by OpenAI for two main tasks: (1) summarising language from different stakeholders to understand their requirements and focus during diagnosis and treatment, diagnostic tools, reasons for online consultation, etc and (2) deriving tagging systems based on the content, and then applying the labels to categorise stakeholders’ requirements, focus, triggers for treatment switch, and so on. When applying GPT-4, prompt engineering was used to optimise results.14 Tactics included providing accurate background information of the disease, and one-shot/few-shot prompting. Here is an example of a drug treatment prompt: ‘Identify AD-related drug treatments. Pay attention to detail and make independent judgements. Summarise any AD drug treatments mentioned. If none are mentioned, return: no relevant information.’ This demonstrates how we use LLM’s summarisation and extraction capabilities to achieve our goals.

Figure 2. Overall workflow and algorithm tools used in the study. *Experts will conduct manual checks on the analytical results. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; BBS, bulletin board system; NER, named-entity recognition; LLMs, large language models.

Stakeholder identification

Considering platform diversity, we employed tailored methods to identify patients. The methodology is shown in online supplemental figure 1. For online consultation platforms, we used two steps to check whether a consultation was an AD-related case. First, if the consultation contained keywords like “diagnosed”, “diagnosis”, “suffering from” or “affected by” followed by AD-related terms, it was deemed a clear AD diagnosis. Additionally, if AD-related keywords were followed by ‘X years’, it indicated a history of AD. Second, we extracted entities including diseases, symptoms, examination terms and medications. For AD-related entities, GPT-4 was used to confirm whether it was an AD case. For e-commerce platforms, we filtered AD-related product comments by searching for AD-related keywords or identifying comments that contained AD-related keywords. Patients were then defined by deduplicating the comments based on username, product, comment and location (if available). For BBS and social media platforms, if person entities and AD-related keywords existed in the context (for BBS) or username and introduction (for social media), the article/post/user would be included in the patient pool. Once the patient pool was established, LLM was used to identify whether a caregiver’s perspective was present. Therefore, the expression of patient information in this paper includes both the patient’s own expression and the caregiver’s paraphrasing. To validate the above methodology, a dedicated team of trained experts meticulously reviewed the patient pool. In the case of discrepancies, the expert assessment was prioritised.

Patient segmentation

To understand patients’ perspectives at different disease stages, we categorised them into three groups: mild, moderate and severe, based on the severity of clinical symptoms affecting daily life,15 using a three-step process (online supplemental figure 2). First, we extracted self-reported descriptions. For example, if the content stated that the patient was diagnosed with severe AD, they would be categorised into the severe group. Second, for those who did not mention their disease stage, we leveraged GPT-4 to categorise them based on the descriptions of AD stages (online supplemental table 1). Third, for cases that cannot be recognised by GPT-4, we did the segmentation based on patients’ behaviours and symptoms. In detail, each text was converted into a list of tokens using pkuseg tokeniser, and symptoms were extracted for expert review to determine the disease stage.

Results

Patient cohort and demographics

Overall, we identified 1211 patients from nine online platforms (figure 1), mainly from online consultation platforms (43%), followed by BBS platforms (24%), e-commerce platforms (23%) and new media platforms (10%). Demographics are shown in table 1. Among 884 patients with gender information, the majority were female. Most identified patients were from Zhejiang, Guangdong and Beijing. Most (82%) were aged 60–90 years. Of the 382 patients with clear disease stages, 42% were classified as having moderate AD, followed by severe AD (34%) and mild AD (24%). Most patients had illness durations of 1–5 years or 5–10 years.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients with AD.

| Demographics | Number of patients,n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender (n=884) | |

| Female | 582 (66) |

| Male | 302 (34) |

| Province* (n=363) | |

| Zhejiang | 35 (10) |

| Guangdong | 33 (9) |

| Beijing | 31 (9) |

| Shandong | 26 (7) |

| Shanghai | 23 (6) |

| Jiangsu | 22 (6) |

| Hebei | 20 (6) |

| Hubei | 20 (6) |

| Hunan | 18 (5) |

| Sichuan | 15 (4) |

| Patient’s age (years)† (n=528) | |

| <50 | 6 (1) |

| [50, 60) | 44 (8) |

| [60, 70) | 124 (23) |

| [70, 80) | 153 (29) |

| [80, 90) | 156 (30) |

| [90, 100) | 44 (8) |

| ≥100 | 1 (0) |

| Disease stage (n=382) | |

| Mild | 90 (24) |

| Moderate | 162 (42) |

| Severe | 130 (34) |

| Duration of AD (n=489) | |

| <1 year | 79 (16) |

| 1 year≤n<5 years | 171 (35) |

| 5 years≤n<10 years | 107 (22) |

| 10 years≤n<20 years | 50 (10) |

| ≥20 years | 2 (0) |

| Unknown‡ | 80 (16) |

A total of 363 patients provided self-reported geographical information; provinces with the top 10 patient count are presented.

Patient age refers to the age of the patient at the time of consultation or publication of content.

‘Unknown’ duration of AD means either of the two situations: (1) 20 patients filled out the form as ‘several years of AD’ but did not specify the exact duration; (2) 57 patients selected the duration of AD as ‘more than half a year’ on Haodaifu, the longest available option, without specifying the duration.

AD, Alzheimer’s disease.

Current diagnosis and treatment

A total of 622 patients mentioned diagnostic tools (online supplemental table 2), with the most common being medical history (97%) and symptoms (84%), followed by physical examinations (41%) and imaging (23%). Cognitive and neurological examinations were less frequently reported. Among patients with moderate and severe AD, other professional examinations, such as blood tests, peripheral blood biomarker tests and cerebrospinal fluid tests, were common. Among 252 patients who sought online consultations, most visited tertiary hospitals in first-tier or new first-tier cities, primarily in the neurology department (60%), with others visiting psychiatry, geriatrics and other specialties.

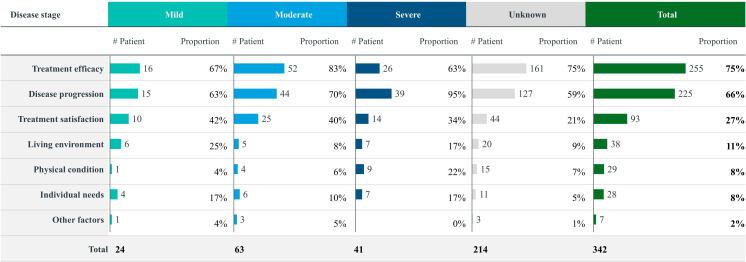

Treatment for AD can be categorised into pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. Among 511 patients who mentioned pharmacotherapy, the most common medications were cholinesterase inhibitors (58%), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists (43%) and antipsychotic drugs (29%) (online supplemental figure 3). Regarding pharmacological treatment concerns, patients were primarily focused on efficacy (76%). Compared with patients with mild and severe AD, those with moderate AD were more concerned about comorbidities, while patients with severe AD were significantly more focused on drug accessibility. Overall, treatment modifications were mainly driven by therapeutic efficacy (75%) and disease progression (66%) (figure 3). Among patients with mild and moderate AD, inadequate efficacy, side effects and the availability of new drugs were the main reasons for changes in treatment related to efficacy, while for patients with severe AD, disease progression, such as deterioration and the onset of new symptoms, was the predominant factor. Non-pharmacological treatments were used across all disease stages, including physical exercise (56%), cognitive training (27%) and dietary adjustments (25%). Among 602 patients who mentioned either pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatments, 38% used combination therapy, 26% used only one drug and 21% used a drug alongside non-pharmacological treatment. The most common combination therapy was memantine with physical exercise (online supplemental figure 4).

Figure 3. Reasons for patients’ treatment switch in different disease stages. ‘Other factors’ refers to the patient mentioning changes in treatment without specifying the reasons.

Patient safety: wandering as an example

A total of 92 patients were reported to have experienced wandering (table 2). Most were aged between 60 and 90 years, with a slight female preponderance. The majority were observed at the moderate stage (39%), and the typical duration of AD was 1–5 years or 5–10 years. Wandering occurred mostly once (43%), followed by multiple times (29%). Triggers were often unknown, but hallucinations/delusions may contribute. Patients who were able to go out alone were more prone to wandering, especially in unfamiliar environments. Caregivers noted the activities of 30 patients during these episodes of disappearance, with most patients being lost while trying to return home. Others were found walking, buying food or hallucinating.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the patients with AD who experienced wandering.

| Demographic | Number of patients,n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (n=92) | |

| [50, 60) | 4 (4) |

| [60, 70) | 16 (17) |

| [70, 80) | 15 (16) |

| [80, 90) | 19 (21) |

| [90, 100) | 3 (3) |

| Unknown* | 35 (38) |

| Gender (n=92) | |

| Female | 48 (52) |

| Male | 38 (41) |

| Unknown* | 6 (7) |

| Disease severity (n=92) | |

| Mild | 9 (10) |

| Moderate | 36 (39) |

| Severe | 16 (17) |

| Unknown* | 31 (34) |

| Duration of AD (n=92) | |

| <1 year | 4 (4) |

| 1 year≤n<5 years | 17 (18) |

| 5 years≤n<10 years | 15 (16) |

| 10 years≤n<20 years | 5 (5) |

| Unknown* | 51 (55) |

| Frequency of wandering (n=92) | |

| One time | 40 (43) |

| Multiple times | 27 (29) |

| Unknown* | 25 (27) |

| Scenarios of wandering (n=92) | |

| Unknown | 62 (67) |

| Returning home | 10 (11) |

| Walking/Strolling | 5 (5) |

| Looking for someone | 3 (3) |

| Shopping for groceries | 3 (3) |

| Others† | 9 (10) |

‘Unknown’ indicates the lack of specific information about the patient who experienced wandering as mentioned in the context.

'Others’ include activities such as getting a haircut, taking the bus, riding a bike, etc.

AD, Alzheimer’s disease.

Caregiver self-portrait analysis

Caregivers play an essential role in supporting patients with AD, who are often unable to live independently. In this study, we identified 756 AD caregivers from online platforms, predominantly the children of the patients. Throughout AD progression, home-based care remains the primary mode of caregiving (87%). Especially in the mild stage, 97% of caregivers choose home-based care. However, as the disease progresses, there is increasing adoption of community and institutional care, reflecting the increasing complexity of care needs and the necessity for more specialised care provisions. Among 705 caregivers, 90% focused on disease management, 37% on daily life care and 25% on psychosocial support (online supplemental table 3). As the disease progresses, caregivers’ focus shifts from disease management and treatment towards an increased emphasis on meeting the evolving demands for daily life care, disease progression monitoring and prognosis assessment (figure 4). This shift indicates the increasing demands on caregivers to manage patients’ daily life needs. They also face challenges related to self-care, fatigue and the need for medical or rehabilitation services. Family and community support become crucial as the disease advances.

Figure 4. Caregiver topics of concern.

Discussion

Main findings

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use NER and LLM tools to analyse over a decade of online data (2010–2024) on SML regarding Chinese patients with AD and their caregivers. The strengths of this study include the utilisation of various types of online platforms and cutting-edge LLM methods. By incorporating some of the most popular social platforms in China, this study ensures broad coverage and enhances the generalisability of its findings. This study captures prevalent dementia themes on social media while providing detailed insights into specific aspects of the condition. The NLP tools and GPT-4 used are currently stable and well-established,16 17 fulfilling our research’s text processing needs.

Consistent with previous studies, patients with AD identified in this analysis were predominantly women (66%),18 and most were aged 70–90 years (59%). Among 382 patients with confirmed disease stages, moderate AD was the most frequently reported (42%), with a reported disease duration of 1–5 years or 5–10 years. Social media insights discussions shed light on evolving diagnostic methods for AD, from traditional medical history, symptoms and imaging to new biomarker techniques for early and accurate AD diagnosis.

Our findings on AD treatment choices aligned with prior studies, with cholinesterase inhibitors, NMDA receptor antagonists and antipsychotics being the most commonly used therapies.19 These treatments are likely preferred for their potential to improve cognitive function and slow disease progression. Treatment adjustments were primarily influenced by efficacy and disease progression, reflecting patient concerns and priorities across different disease stages. Patients placed significant emphasis on drug efficacy (75%), reflecting their keen interest in treatment effectiveness, which is crucial for managing the progressive nature of AD and its impact on quality of life. Patients with moderate AD expressed greater concerns due to more challenging clinical symptoms,20 while those with severe AD prioritised drug accessibility, possibly reflecting the physical, logistical or financial challenges in obtaining necessary medications. Non-pharmacological interventions like physical exercise, cognitive training and dietary modifications21 22 play a significant role in managing AD and are widely adopted across all disease stages. Most patients chose a combination of drug and non-pharmacological treatment, with memantine and physical exercise being common choices, highlighting the acceptance and advantages of a comprehensive treatment strategy for AD management.

A key focus of this study was the analysis of patients with AD who experienced getting lost, which occurred more frequently during the moderate stage due to episodic memory impairment and cognitive decline. Patients with mild AD often live independently, while those with severe AD, who have limited mobility and are frequently bedridden, have a lower risk of getting lost.23 In fact, episodes of getting lost can occur at any stage of dementia, often leaving family caregivers unprepared.24 Early symptoms of AD often include spatial disorientation, typically emerging within 2 years after the clinical onset and increasing the risk of getting lost.25 As a globally prevalent issue, alarming statistics indicate that up to 70% of patients with dementia experience at least one episode of getting lost.26 Our study revealed that 43% of patients with AD reported one lost incident, while 29% experienced multiple episodes, addressing a critical research gap in understanding the prevalence of getting lost among patients with AD. Following an initial incident, patients often adapt by staying within familiar areas, avoiding unfamiliar places and limiting outdoor activities within the community.26 Due to this behavioural adaptation and increased caregiver vigilance, measures like closer monitoring, tracking devices and restrictions on unsupervised outings are taken.25,27 Consequently, a significant portion of patients experience only one lost incident. However, it is crucial to recognise that AD progression can still lead to lost episodes even within familiar environments.28 29 Furthermore, not all patients with AD and their caregivers implement proactive measures to forestall the recurrence of getting lost.27 The inadequate preventive strategies adopted by some caregivers contribute substantially to the elevated risk of repeated lost incidents. One study found that after a 2.5-year follow-up, 40% of patients with initial episodes experienced new lost events, highlighting the ongoing challenge.25

Similar to previous studies,18 19 22 most caregivers in our analysis were adult children, while spouses accounted for <10%, contrasting with studies showing spousal caregivers are more active online.30 This discrepancy may be due to differences in the specific social forums. A longitudinal study examining both quantitative and qualitative aspects of caregiver discussions on social platforms suggested high engagement in activities of daily living.11 As disease advances, family and community support becomes increasingly important.

Limitations

Limitations exist in this study. First, it relies on online data, which introduces selection bias, favouring internet-proficient, urban and younger individuals, limiting generalisability. This constraint echoes similar limitations in previous research, where online data often fail to capture the full diversity of demographic profiles. Furthermore, despite efforts to include all patients with AD on digital platforms, inadvertent exclusions persist, challenging the validity and reliability of the study’s conclusions. In addition, the unstructured nature of free-text data may lead to inaccuracies and misinterpretation, and hinder trend analysis over time. Finally, distinguishing between patient and caregiver perspectives is challenging, potentially introducing bias due to limited observation.

Implications

This study provides a large sample of patients with AD and their caregivers, contributing to the understanding of their real-world experiences in China. The study aligns with previous research emphasising the importance of large-scale, real-world data for complex diseases like AD. While offering a snapshot of social media insights, future research could track and predict key terms for early AD diagnosis. Additionally, enhancing engagement analysis using NLP on user interactions in public forums deserves future exploration.

Supplementary material

Biography

Nan Zhi obtained her Doctor of Medicine degree in Neurology from Peking Union Medical College, China, in 2011. During her doctoral programme, she focused on the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment in ischaemic cerebrovascular disease, specifically by developing animal models of cerebral small vessel disease. She is currently an attending physician in the Department of Neurology at Shanghai Renji Hospital, affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China. Her primary research interests include vascular and neurodegenerative diseases related to cognitive impairment, with a particular focus on Alzheimer’s disease. Her key research findings have been published in journals such as Aging-US and European Journal of Neurology.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (2021ZD0201804, GW).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study was reviewed by the Research Ethics Committee of Renji Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine and deemed exempt from review as it did not meet the definition of ‘human or animal subject research’.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Zhang H-G, Fan F, Zhong B-L, et al. Relationship between left-behind status and cognitive function in older Chinese adults: a prospective 3-year cohort study. Gen Psychiatr. 2023;36:e101054. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ren R, Qi J, Lin S, et al. The China Alzheimer report 2022. Gen Psychiatr. 2022;35:e100751. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2022-100751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang H, Xie H, Qu Q, et al. The continuum of care for dementia: needs, resources and practice in China. J Glob Health. 2019;9:020321. doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia J, Zuo X, Jia X-F, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia in neurology outpatient departments of general hospitals in China. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:446–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.06.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao W, Jones C, Wu M-LW, et al. Healthcare professionals’ dementia knowledge and attitudes towards dementia care and family carers’ perceptions of dementia care in China: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31:1753–75. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiao CY, Wu HS, Hsiao CY. Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:340–50. doi: 10.1111/inr.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook N, Mullins A, Gautam R, et al. Evaluating patient experiences in dry eye disease through social media listening research. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8:407–20. doi: 10.1007/s40123-019-0188-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt AL, Rodriguez-Esteban R, Gottowik J, et al. Applications of quantitative social media listening to patient-centric drug development. Drug Discov Today. 2022;27:1523–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2022.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humphrey L, Willgoss T, Trigg A, et al. A comparison of three methods to generate a conceptual understanding of a disease based on the patients’ perspective. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;1:9. doi: 10.1186/s41687-017-0013-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrar M, Lundt L, Franey E, et al. Patient perspective of tardive dyskinesia: results from a social media listening study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:94. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachmann P. Caregivers’ experience of caring for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease: a content analysis of longitudinal social media communication. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4412. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tahami Monfared AA, Stern Y, Doogan S, et al. Stakeholder insights in Alzheimer’s disease: natural language processing of social media conversations. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;89:695–708. doi: 10.3233/JAD-220422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo R, Xu J, Zhang Y, et al. Pkuseg: a toolkit for multi-domain chinese word segmentation. arXiv. 2019:190611455. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meskó B. Prompt engineering as an important emerging skill for medical professionals: tutorial. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e50638. doi: 10.2196/50638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19:1598–695. doi: 10.1002/alz.13016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeung A, Iaboni A, Rochon E, et al. Correlating natural language processing and automated speech analysis with clinician assessment to quantify speech-language changes in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13:109. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00848-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z, Zhang H, Yang X, et al. Assess the documentation of cognitive tests and biomarkers in electronic health records via natural language processing for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Int J Med Inform. 2023;170:104973. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tahami Monfared AA, Stern Y, Doogan S, et al. Understanding barriers along the patient journey in Alzheimer’s disease using social media data. Neurol Ther. 2023;12:899–918. doi: 10.1007/s40120-023-00472-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isaacson RS, Seifan A, Haddox CL, et al. Using social media to disseminate education about Alzheimer’s prevention & treatment: a pilot study on Alzheimer’s universe (www.AlzU.org) J Commun Healthc. 2018;11:106–13. doi: 10.1080/17538068.2018.1467068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soria Lopez JA, González HM, Léger GC. Alzheimer’s disease. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;167:231–55. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804766-8.00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamasaki T. Preventive strategies for cognitive decline and dementia: benefits of aerobic physical activity, especially open-skill exercise. Brain Sci. 2023;13:521. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13030521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parums DV. A review of the current status of disease-modifying therapies and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Med Sci Monit. 2024;30:e945091. doi: 10.12659/MSM.945091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zvěřová M. Clinical aspects of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Biochem. 2019;72:3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2019.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S-H, Wu S-FV, Liu C-Y, et al. Experiences of family caregivers taking care getting lost of persons with dementia: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24:452. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-05891-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pai MC, Lee CC. The incidence and recurrence of getting lost in community-dwelling people with Alzheimer’s disease: a two and a half-year follow-up. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puthusseryppady V, Morrissey S, Aung MH, et al. Using GPS tracking to investigate outdoor navigation patterns in patients with Alzheimer disease: cross-sectional study. JMIR Aging. 2022;5:e28222. doi: 10.2196/28222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams S, Sammut A, Blaxland W. Boundary crossing and boundary violation by service providers and carers in dementia care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18:565–7. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206214029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenbaum RS, Gao F, Richards B, et al. 'Where to?' remote memory for spatial relations and landmark identity in former taxi drivers with Alzheimer’s disease and encephalitis. J Cogn Neurosci. 2005;17:446–62. doi: 10.1162/0898929053279496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Algase DL, Moore DH, Vandeweerd C, et al. Mapping the maze of terms and definitions in dementia-related wandering. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11:686–98. doi: 10.1080/13607860701366434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni C, Song Q, Malin B, et al. Examining online behaviors of adult-child and spousal caregivers for people living with Alzheimer disease or related dementias: comparative study in an open online community. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e48193. doi: 10.2196/48193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.