Abstract

The immediate goals of pharmacological management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are to minimise symptoms and improve exercise performance. The longer-term goals are to reduce the future risk of exacerbations, lung function decline and mortality. It is now recognised that a subset of COPD patients have type 2 inflammation, which is identified by the presence of higher blood eosinophil counts (BEC). Individuals with higher BEC show a greater response to pharmacological interventions targeting type 2 inflammation, including inhaled corticosteroids and the monoclonal antibody, dupilumab. The use of BEC as a biomarker to guide pharmacological treatment has enabled a precision medicine approach in COPD. This article reviews recent advances in the pharmacological treatment of COPD, encompassing the optimum use of inhaled combination treatments and the evidence to support the use of the novel inhaled phosphodiesterase inhibitor ensifentrine and monoclonal antibodies in patients with COPD.

Key Points

| Blood eosinophil counts identify a subset of COPD patients with type 2 inflammation. |

| COPD patients with higher blood eosinophil counts demonstrate a more favourable response to pharmacological interventions targeting type 2 inflammation. |

| New concepts in the pharmacological treatment of stable COPD include moving treatments towards earlier stages of disease and targeting high risk individuals. |

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death and a major public health challenge worldwide. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a generally progressive condition that is primarily caused by long-term exposure to tobacco smoke and/or the inhalation of toxic particles and gases from household, occupational or outdoor air pollution [1–4]. The resulting chronic inflammation leads to airway narrowing, manifesting as chronic bronchitis and bronchiolitis, and alveolar destruction (emphysema) [4]. Individuals often have predisposing factors that can amplify the risk of developing COPD or the rate of disease progression, such as abnormal lung development, an enhanced inflammatory response to chronic irritants, or increased susceptibility to bacterial or viral infections [4, 5].

Patients with COPD typically experience a range of pulmonary symptoms including breathlessness, cough, and sputum production, in addition to systemic complications such as reduced exercise tolerance, frailty and fatigue [4]. Acute exacerbations, characterized by a sudden worsening of respiratory symptoms that may require hospitalisation, can be fatal or result in a prolonged decline in health and quality of life [4]. Importantly, both COPD and its exacerbations are complex, heterogeneous and systemic disorders, meaning that they require a personalised approach to their assessment and management [6, 7]. The overall management of patients with COPD requires the implementation of personalised pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Non-pharmacological management forms an important component of COPD care, encompassing opportunities such as physical exercise/pulmonary rehabilitation, smoking cessation support, education and self-management [4].

The immediate goals of pharmacological management in COPD patients are to minimise symptoms and improve exercise performance. The longer-term goal is to reduce the future risk of exacerbations, lung function decline and mortality. The use of inhaled treatments is common in COPD, aiming to optimise the therapeutic index (benefits vs risks) by targeting drug delivery into the lungs while minimising systemic exposure. Inhaled bronchodilators address the fundamental physiological issue of airflow obstruction in COPD, improving lung function and thereby reducing dyspnoea [8]. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are anti-inflammatory drugs that can prevent exacerbations, and recent advances have enabled the identification of responders and non-responders to ICS using clinical and biomarker characteristics (precision medicine) [9].

The use of combination inhalers with two or three drugs with different mechanisms of action is now commonplace in clinical practice. Clinical trials have provided evidence that single inhaler triple therapy prevents mortality in a subgroup of COPD [10, 11]. The concepts of precision medicine and mortality prevention have led to a re-organisation of the use of inhaled treatments in clinical practice. Furthermore, positive late-phase clinical trial results leading to regulatory approval of the novel inhaled phosphodiesterase inhibitor ensifentrine and the systemically administered monoclonal antibody dupilumab that targets type 2 (T2) inflammation have provided new options for the treatment of COPD [12–14].

The Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report aims to provide evidence-based recommendations for the management of COPD [4]. The updated GOLD 2025 report contains important changes with respect to pharmacological management, reflecting new clinical trial evidence and the availability of new treatment options (dupilumab and ensifentrine) for patients with COPD [15]. We review the changing landscape of COPD pharmacological treatment, focusing on recent advances, the optimum use of inhaled combination treatments and the evidence to support the use of ensifentrine and dupilumab in clinical practice. We also consider the future of COPD pharmacological management.

Type 2 Inflammation in COPD

The recognition that a subgroup of COPD patients show evidence of pulmonary T2 inflammation has led to significant advances in COPD pharmacological treatment, which will be explained later. This section will explain the nature of T2 inflammation in COPD.

The primary role of eosinophils is to defend against helminth infections, while these cells can also contribute to antimicrobial defence [16, 17]. Increased eosinophil numbers are recognised as part of the T2 inflammatory profile in asthma, which also includes basophils and mast cells along with the key cytokines interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5 and IL-13 [18]. Interleukin-4 contributes to the differentiation of T-helper (Th)-2 lymphocytes from naïve cluster of differentiation (CD)4+ T-lymphocytes and induces immunoglobulin E (IgE) class switching of B-lymphocytes [19]. Interleukin-5 stimulates eosinophilopoiesis from the bone marrow and primes eosinophils for tissue extravasation from the vasculature [20], and IL-13 induces goblet cell hyperplasia with increased production of mucin (MUC)5AC, and airway smooth muscle proliferation and contraction [21]. Aberrant T2 immune responses contribute to the pathophysiology of airway remodelling in asthma by causing goblet cell hyperplasia and mucus plugging, tissue fibrosis and smooth muscle proliferation and hyper-responsiveness [22].

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease studies of tissue samples from the large and small airways have shown increased eosinophil counts in a sub-group of patients, while induced sputum sampling has also shown that a subset of COPD patients have eosinophilic inflammation defined as sputum eosinophil counts > 3% [23–25]. These findings indicate the presence of T2 inflammation in some, but not all COPD patients. This concept is further supported by airway sampling studies that have reported higher gene or protein expression levels of T2 mediators, including IL-5 and IL-13, in COPD patients who have higher eosinophil counts [17, 24].

A common debate is whether the presence of higher eosinophil counts and/or T2-mediator levels in COPD patients is due to a missed clinical diagnosis of asthma [26]. Against this argument are airway gene expression studies showing that the nature of T2 inflammation differs in asthma compared to COPD [26]. For example, 12 genes from bronchial brush samples were associated with blood eosinophil counts (BEC) in COPD patients, 1197 were associated with BEC in asthma patients, and only one cystatin SN (CST1) overlapped between COPD and asthma patients [27]. In a different study using bronchial brush and sputum samples to examine gene expression, four of six 6 well-known asthma genes were higher in eosinophilic COPD patients: chemokine ligand (CCL)26, CST1, IL-13, calcium-activated chloride channel regulator 1 (CLCA1), with the discordance for periostin (POSTN) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 (SERPINB2) highlighting that different pathways are involved in T2 inflammation in COPD versus asthma [28]. Type 2 inflammation is present in a subset of COPD patients, and represents an opportunity for targeted anti-inflammatory treatment.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers have many potential applications in clinical medicine; for example, biomarkers may be diagnostic, prognostic, predict treatment response and/or be used to monitor the effect of a pharmacological intervention [29]. It is not necessary for a biomarker to fulfill all of these properties to be useful; a biomarker can be used for just one of these purposes. A validation process should be followed to ensure that the biomarker gives reliable results, and that any limitations of the biomarker are understood [30]. Plasma fibrinogen is currently the only COPD biomarker that has been formally recognised by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) after submission of validation and qualification data [31]. While this biomarker is prognostic with regard to exacerbations and all-cause mortality [31], the threshold used for prediction of worse clinical outcomes excludes the majority of patients [32]. Subsequently, this biomarker has not been used regularly to enrich clinical trials for patients who are more likely to exacerbate as it limits recruitment to a narrow population.

Multiple studies have shown that BEC can serve as a biomarker to detect T2 inflammation in the lungs of COPD patients. Blood and lung eosinophil counts show a positive correlation in most studies, while COPD patients with higher BEC display airway gene expression profiles compatible with increased T2 inflammation [17, 23, 27, 28]. While most of these studies have been positive, negative findings or weak associations have been reported, which can reflect a lack of laboratory accuracy if BEC are only reported to one significant figure (e.g. 0.1/0.2/0.3 cells/µL).

Higher BEC have been observed in COPD patients (median: 200 cells/µL) compared to healthy non-smoking (median: 100–120 cells/µL [33, 34]) and current smoking individuals (median: 140 cells/µL [33]). This difference is driven by a subgroup of COPD patients with elevated BEC, ≥ 300 cells/µL, accounting for approximately 19–37% of patients [33, 35–40]. Blood eosinophil counts are prone to circadian variation [41, 42]. Furthermore, higher BEC counts are prone to greater variability over longer time periods (weeks or months), while lower BEC are more likely to be stable, with similar findings reported for sputum and lung eosinophil counts [25, 39, 40, 43]. While a stable biomarker profile is easier to interpret in clinical practice, these findings suggest dynamic inflammatory processes which can fluctuate in COPD patients with a susceptibility to develop T2 inflammation, while persistently low BEC identify a stable T2 low sub-group. While a single BEC is useful as a guide, multiple BEC increase confidence in the identification of COPD patients without T2 inflammation demonstrated by persistently low BEC. A study investigating the phenotype of patients based on repeated BEC over time demonstrated that patients with persistently high BEC during the stable state are more likely to suffer an exacerbation that is eosinophilic in nature (89% of exacerbations were eosinophilic in this group) [44]. Interestingly, eosinophilic exacerbations also occurred in patients with lower BEC during the stable state although at a much lower frequency.

Blood eosinophil counts enable the identification of COPD patients with T2 inflammation, facilitating the selection of appropriate pharmacological treatment in clinical practice and enriching clinical trials for the target population. Recent evidence supports BEC as prognostic markers with regard to lung function decline, as this has been demonstrated in younger healthy non-smokers, smokers and COPD patients [45–48].

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) is a non-invasive measure of airway inflammation that is used as a biomarker of T2 airway inflammation in asthma, with diagnostic utility and providing predictive ability for response to pharmacological intervention, notably monoclonal antibodies targeting T2 inflammation [49]. Whilst a relationship between FeNO levels and sputum eosinophil counts exists in both COPD and asthma [50, 51], FeNO is a biomarker of IL-13 activity as this cytokine drives inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase activity [52]. The utility of FeNO in COPD is limited by the effect of current smoking on FeNO levels; current smoking suppresses FeNO levels [50]. Nevertheless, a subgroup of COPD patients without concomitant asthma displays elevated FeNO [50, 53], with persistently high FeNO levels (≥ 20 ppb) being associated with a greater risk of exacerbation [54].

Bronchodilators

There are two well established classes of bronchodilator delivered by inhalation for the treatment of COPD; β2 agonists and muscarinic antagonists [55]. Beta-2 agonists bind to receptors on airway smooth muscle cells, thereby increasing cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels [55]. Muscarinic antagonists prevent acetylcholine binding to muscarinic M3 cell surface receptors on airway smooth muscle cells [55]. These different mechanisms both cause relaxation of smooth muscle tone, and can be combined in clinical practice for additive benefits. Short-acting β2 agonists (SABAs) and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMAs) are rapid onset to allow fast symptom relief, while long-acting β2 agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) are used for regular maintenance treatment to address symptoms and improve exercise performance [4]. Longer-acting bronchodilators are administered either once or twice a day. While both of these drug classes are generally well tolerated, higher doses of β2 agonists may cause tremor and tachycardia while muscarinic antagonists may cause dry mouth, glaucoma and urine retention [56, 57].

Studies of lung tissues using different techniques including in situ hybridisation and radioligand binding assays have demonstrated variations in muscarinic receptor and β-adrenoceptor levels depending on the anatomical location in the airway tree [58], with greater β-adrenoceptor expression in the distal lung.

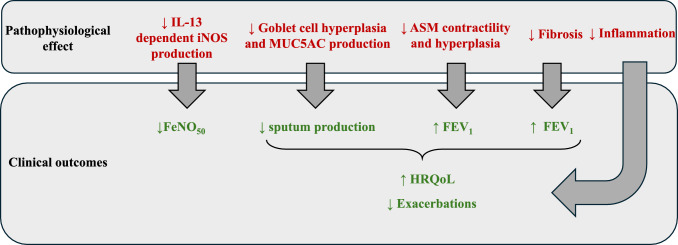

Long-acting bronchodilator (LABD) monotherapies improve various measurements of lung function in COPD patients; for example, decreasing small airway resistance and gas trapping whilst increasing forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) [59, 60]. These changes are associated with reduced dyspnoea and improved quality of life, while there is also a reduction in exacerbation rates [8, 59, 61, 62]. Single inhaler LAMA/LABA combinations provide greater clinical benefits compared to LABD monotherapy with regard to improvements in lung function, symptoms and quality of life [61–65]. Furthermore, subgroup analyses of clinical trials focusing on individuals who were not taking inhaled maintenance treatment reported similar results, supporting the GOLD recommendation to use LAMA/LABA combinations as first-line treatment for newly diagnosed COPD patients with significant dyspnoea [66–71]. For individuals with fewer symptoms, a LABD monotherapy could be first-line treatment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

GOLD recommendations for initial pharmacological treatment for COPD. CAT COPD assessment test, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICS inhaled corticosteroid, GOLD global initiative for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, LABD long-acting bronchodilator, LAMA long acting muscarinic antagonist

Clinical trials in COPD patients with a history of exacerbations have provided some evidence that LAMA/LABA combinations are superior to LABD monotherapy for exacerbation prevention, although the magnitude of benefit is small (< 15% exacerbation reduction), and the results have been inconsistent [72, 73]. However, the broad range of benefits of LAMA/LABA treatment on lung function, symptoms and quality of life compared to LABD monotherapy forms the basis for the GOLD recommendation to use these combinations as a treatment escalation from LABD monotherapy [4].

Inhaled Corticosteroids (ICS)

Corticosteroids exert anti-inflammatory effects by forming a complex with the glucocorticoid receptor that translocates to the nucleus to modify gene transcription [74, 75]. While the delivery of corticosteroids by inhalation decreases systemic exposure, the use of ICS is still associated with adverse systemic effects such as osteoporosis in COPD patients [76]. Furthermore, the risk of pneumonia is increased by ICS use in a subgroup of COPD patients with other risk factors including increasing age, lower FEV1, lower body mass index (BMI) and previous pneumonia episodes [4]. It is therefore important to judge the potential for benefit versus risk for each patient individually before initiating ICS treatment.

Inhaled corticosteroids can be delivered through an ICS/LABA or ICS/LABA/LAMA (triple therapy) combination inhaler. Clinical trials in COPD patients with a history of exacerbations have consistently demonstrated superiority of triple therapy over ICS/LABA, due to the benefits of additional LAMA treatment on lung function, quality of life and exacerbations [77, 78]. Consequently, GOLD recommends triple therapy, rather than ICS/LABA, as the preferred treatment option for COPD patients with exacerbations where ICS treatment is being considered [4]. The Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease recommends that escalation to triple therapy is considered for COPD patients who are being treated with ICS/LABA and require further treatment for symptoms or exacerbations. Key concepts in the use of triple therapy for COPD are now discussed and summarised in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Triple therapy (ICS/LABA/LAMA) in the treatment of stable COPD, in comparison to LABA/LAMA therapy. BEC blood eosinophil count, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CV cardiovascular, HRQoL health-related quality of life, ICS inhaled corticosteroid, GOLD global initiative for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, LABD long-acting bronchodilator, LAMA long-acting muscarinic antagonist, T2 Type 2

Precision Medicine Approach to ICS Use

The InforMing the Pathway of COPD Treatment (IMPACT) (n = 10,355) and the ETHOS study (n = 8588) are the largest clinical trials of triple therapy in COPD, enrolling individuals with exacerbations in the previous year despite maintenance inhaled treatment which comprised mainly double or triple combinations [77, 78]. In these studies, the benefit of ICS could be determined by comparing triple therapy against LAMA/LABA; the exacerbation rate reduction was approximately 25% in both studies. While the majority of individuals in these studies had ≥ 2 moderate exacerbations or 1 severe exacerbation in the previous year, there was still a benefit of ICS in the subgroup with one exacerbation previously. Similarly, the TRIBUTE study enrolled COPD patients on LABD monotherapy or a double combination in real life (prior triple therapy use was not allowed; n = 1532) and showed a benefit of triple therapy versus LAMA/LABA in the subgroup with one exacerbation in the previous year [79]. Overall, these subgroup analyses indicate the potential for ICS to benefit COPD patients with one or more exacerbations in the previous year.

Post hoc and pre-specified analyses of clinical trials have consistently reported that the ICS benefit is greater at higher BEC [80]. Modelling the relationship between BEC and the ICS treatment effect has shown that the ICS benefit rises incrementally with BEC above approximately 100 eosinophils/µL, with no benefit below this threshold [81–83]. These findings can be explained by the relationship between BEC and pulmonary T2 inflammation already discussed, with T2 inflammation being the target of ICS [9]. Interestingly, we previously reviewed clinical trials that investigated the effects of ICS on bronchial biopsy or sputum cell counts and found that only a minority of studies reported that ICS reduced lung eosinophil numbers while more studies reported a reduction in lymphocytes or mast cell counts [9]. Furthermore, bronchial biopsy gene expression analysis has shown that ICS reduce the expression levels of T2 genes including genes involved in mast cell function [84]. Overall, higher BEC seem to identify COPD patients with a profile of T2 inflammation encompassing components that are sensitive to ICS treatment (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pharmacological treatment for stable COPD. BEC blood eosinophil count, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CV cardiovascular, HRQoL health-related quality of life, ICS inhaled corticosteroid, IL interleukin, GOLD global initiative for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, T2 Type 2

The Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease recommend that BEC can help identify COPD patients who are more likely to respond to ICS treatment, with > 100 eosinophils/µL identifying potential responders while > 300 eosinophils/µL identifies individuals who are very likely to respond [4]. Blood eosinophil counts should be used alongside clinical assessment of exacerbation risk, and the potential for ICS-related adverse effects. Two recent post hoc analyses of the Fluticasone Salmeterol on COPD Exacerbations (FLAME) and The Inhaled Steroids in Obstructive Lung Disease in Europe (ISOLDE) studies (n = 3362 and n = 751, respectively) have identified that BEC change during ICS treatment (BEC measured on ICS treatment minus BEC off ICS) may provide additional information as a biomarker for treatment response with respect to exacerbation reduction [85, 86]. In up to 40% of patients, BEC was reduced with ICS therapy, and these patients appeared to gain more benefit from ICS (reduced rate of exacerbations and reduced lung function decline) with no significant pneumonia burden. Conversely, BEC increased with ICS treatment in 20% of participants; in these patients, ICS had a deleterious effect with an increased rate of exacerbations, accelerated lung function decline and increased pneumonia risk. For patients whose BEC did not change significantly, baseline BEC counts remained a useful guide for ICS administration. Blood eosinophil count change in these studies was analysed either after initiation of ICS at randomisation or withdrawal of ICS during the run-in period. Blood eosinophil count change on ICS treatment is a promising biomarker that, upon prospective clinical validation, could be considered in clinical practice.

An analysis of the IMPACT study and a post hoc pooled analysis of ICS/LABA clinical trials reported that the effect of ICS was reduced in current smokers [81, 87]. There are other analyses that align with these findings [88, 89], although many sub-group analyses of large clinical trials have shown no difference between current and ex-smokers with regard ICS effect [90]. The positive results in IMPACT and the post hoc ICS/LABA analysis may reflect the sample size and statistical power. The mechanism underlying this current smoking effect is unclear; however, one plausible explanation is that current smoking causes oxidative stress and dysregulation of innate immune function that is insensitive to corticosteroid treatment [9].

Mortality

The IMPACT and ETHOS clinical trials reported all-cause mortality as a pre-specified endpoint; on-treatment mortality was reduced by 42% and 46% for triple therapy versus LAMA/LABA, respectively [77, 78], with comparable results for off-treatment analysis [10, 11]. The large sample size of these studies facilitated these analyses, and the results were either statistically significant or nominally significant. The most likely explanation for these findings is that the ICS-related exacerbation reduction led to an associated benefit on mortality. The ETHOS study reported that both the exacerbation and mortality benefit increased at higher BEC [11], underscoring the probable association between these outcomes.

The influence of ICS withdrawal on exacerbation and mortality outcomes in these studies has been debated, as this is an issue relevant to patients on ICS treatment in real life who were subsequently randomised to receive LAMA/LABA treatment [91]. However, the treatment effect (triple vs LAMA/LABA) on exacerbations in the ETHOS study was not influenced by prior ICS use [11]. Furthermore, in both studies it has been reported that the ICS-related mortality benefit was maintained throughout the study period without an excess of events shortly after randomisation due to abrupt ICS withdrawal. Moreover, even if there was an influence of ICS withdrawal on mortality, this would still support the concept that ICS prevent mortality in selected COPD patients. There have been questions raised about the possible inclusion of patients with asthma in these studies [92]. It should be noted that the patients included were being treated for COPD in real life and met the diagnostic criteria for COPD based on symptoms, smoking history and lung function. Consequently. the issue is whether some patients had asthma in addition to COPD, despite efforts from the investigators to exclude patients with asthma. The beneficial response to ICS, in terms of both exacerbations and mortality, was associated with higher BEC. The over-simplification that these COPD patients with higher BEC have asthma is not supported by scientific data, as the nature of T2 inflammation in COPD patients with higher BEC is different from T2 inflammation in asthma [26–28, 93, 94].

The effects of ICS/LABA on all-cause mortality was evaluated in moderate COPD with increased cardiovascular risk but not enriched for high exacerbation risk in The Study to Understand Mortality and Morbidity in COPD (SUMMIT) study (n = 16,485) [95]. The negative results for the primary analysis of all-cause mortality highlight that the benefit of ICS on mortality is only observed in selected COPD patients, and IMPACT and ETHOS indicate that higher exacerbation risk individuals are those most likely to benefit.

Cardiovascular Risk

It is well recognised that COPD patients commonly have cardiovascular co-morbidities [96]. There are several studies that have shown that the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke is increased during and immediately after an exacerbation [97, 98]. There are different mechanisms that can explain the association between exacerbations and cardiovascular events, including increased systemic inflammation and hypoxia during exacerbations [96]. There is evidence to suggest that ICS reduced cardiovascular events in the ETHOS study; a post hoc analysis showed a benefit of triple therapy versus LAMA/LABA with regard to time to first major adverse cardiac event (MACE) and time to first cardiac adverse event [99]. This analysis does not prove that triple therapy reduced cardiovascular events that were specifically related to exacerbations, but nevertheless supports the potential for ICS-related cardiovascular risk reduction in COPD patients with high exacerbation risk. The European Respiratory Society’s study on Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (EUROSCOP) reported fewer ischaemic cardiac events with ICS versus placebo (3.0 vs 5.3%, respectively, p = 0.048), although the population had milder COPD compared to ETHOS with less background use of LABDs as the study was conducted over 20 years ago [100]. In contrast, a large retrospective study using UK primary care data (n = 113,353) showed no protective effect of ICS on MACE events [101]. The SUMMIT study, conducted in COPD patients with increased cardiovascular risk but not enriched for increased exacerbation risk showed no benefit of ICS on mortality [95]. Taken together, ETHOS and SUMMIT suggest that any benefit of ICS on cardiovascular outcomes is more likely to be observed in COPD patients with more exacerbations, as these events increase cardiovascular risk. Further prospective studies are needed to investigate the potential of ICS to improve cardiovascular outcomes and the COPD subgroups where such benefit is most likely.

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors reduce the hydrolysis of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which are intracellular second messengers [102]. Phosphodiesterase-4 is an isoenzyme that is highly expressed in immune cells, thereby promoting pro-inflammatory signalling. The orally administered PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast prevents cAMP breakdown to provide anti-inflammatory effects [102]. While roflumilast has shown benefits on exacerbation prevention in COPD clinical trials, the side-effect profile of this drug has limited its use in clinical practice [103, 104]. These side effects arise from systemic exposure and include gastrointestinal disturbance, nausea and weight loss.

The delivery of PDE inhibitors by inhalation provides a way to reduce systemic exposure and optimise the therapeutic index (benefit vs risk). A key aim of inhaled delivery is to ensure adequate lung exposure; however, the formulation and delivery system dictate the fraction of the drug delivered to the lungs and, importantly, the smaller airways in the distal lung, which is a key anatomical location of disease pathophysiology in COPD [105]. One of the potential advantages of systemic administration is the potential for drug distribution evenly throughout the lungs, including the distal airways. Functional respiratory imaging suggests that roflumilast reduces lobar hyperinflation, presumably through anti-inflammatory effects on the distal airways [106]. Despite this beneficial pharmacological activity in the distal lungs, the systemic adverse effects of roflumilast can be problematic for many COPD patients.

Phosphodiesterase-3 inhibition prevents the breakdown of both cAMP and cGMP levels [102]. Phosphodiesterase-3 is expressed in smooth muscle cells but has lower expression on immune cells compared to PDE4 [107]. Ensifentrine targets the inhibition of both PDE3 and PDE4, with higher potency for PDE3 versus PDE4 in vitro [108]; this pharmacological profile suggests potential for both bronchodilator and anti-inflammatory effects. It has been developed as a formulation for nebulisation in order to reduce systemic exposure.

During early clinical development, a single ensifentrine and salbutamol (a short-acting beta agonist) dose was observed to have similar peak bronchodilator effects [109]. Ensifentrine was also shown to provide additive bronchodilator effects when added to a beta-agonist or a muscarinic antagonist [109]. The addition of ensifentrine to a LAMA over 4 weeks led to improved FEV1 and quality of life. Dose-ranging studies indicated that 3 mg was optimal for dosing twice daily [110]. The phase 3 ENHANCE-1 and -2 (Ensifentrine as a Novel inhaled Nebulised COPD therapy) studies investigated ensifentrine versus placebo over 24 weeks (n = 763 and 790, respectively) (study design and key results shown in Fig. 4) [14]. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with a modified Medical Research Council score ≥ 2 were recruited to enrich for individuals with greater dyspnoea. Patients who were using long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy, with or without ICS, were enrolled and continued their prior inhaled treatment. Individuals using LAMA/LABA combinations or triple therapy were excluded. Ensifentrine significantly improved average FEV1 over 12 hours post-dose versus placebo at Week 12 (primary endpoint) in both studies, with mean differences of 87 and 94 mL (p < 0.001). There was an improvement in quality of life at Week 24 in one of these studies, while breathlessness was significantly improved in both studies with the treatment difference for the transition dyspnoea index (TDI) being 0.9–1.0 (p < 0.001). It is notable that individuals with greater dyspnoea were included, which may have facilitated the magnitude of the TDI treatment effect observed, which was larger than observed in many previous studies of other LABDs.

Fig. 4.

Ensifentrine as a Novel inhaled Nebulised COPD thErapy (ENHANCE-1 and -2). AUC area under the curve, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, E-RS EXACT- respiratory symptoms tool, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 second, HRQoL health-related quality of life, ICS inhaled corticosteroid, GOLD global initiative for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, LABD long-acting bronchodilator, LAMA long-acting muscarinic antagonist, mMRC modified medical research questionnaire, RR risk ratio, SGRQ Saint George’s respiratory questionnaire, TDI transition dyspnoea index

The ENHANCE studies were not specifically designed to investigate exacerbations, as there was no specific inclusion of patients with higher exacerbation risk. The relatively low exacerbation rates in the placebo arms (approximately 0.42/year) reflect the study design. While ensifentrine reduced exacerbation rates by 36% and 43%, for ENHANCE-1 and –2 respectively, the effect of this drug in COPD patients with high exacerbation risk remains to be investigated.

Ensifentrine was well tolerated, in line with the expectation that inhaled delivery would limit the occurrence of systemic PDE4-related adverse effects. The incidence of typical PDE4-related adverse effects, such as diarrhoea, was similar in the active and placebo groups in the ENHANCE studies [14]. There was a low incidence of mental health adverse events with ensifentrine treatment suggesting some impact of systemic exposure and mirroring similar cases with roflumilast.

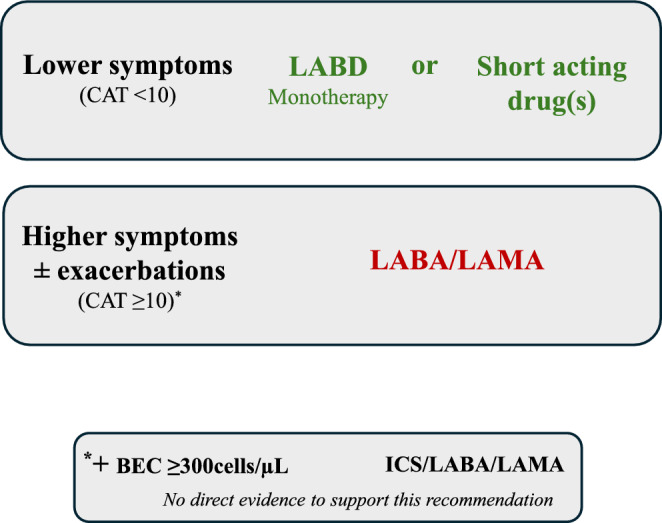

Dupilumab

The IL-4 receptor α (IL-4Rα) acts as a shared receptor for both IL-4 and IL-13 [111]. Interleukin-4 increases Th2 cell activation and IgE production, while IL-13 causes airway remodelling, mucus hypersecretion and smooth muscle constriction and hyperplasia [19]. Increased IL-13 gene expression in the airways is a feature of COPD with higher BEC, implicating IL-13 as a component of T2 inflammation in COPD [28]. Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that blocks signalling through IL-4Rα and is an effective treatment for both atopic dermatitis and severe asthma with T2 inflammation [112, 113]. Dupilumab reduces exacerbation rates and improves lung function and symptoms in patients with asthma [113]. Furthermore, functional respiratory imaging has demonstrated that dupilumab reduces mucus plug scores in moderate to severe asthma patients with evidence of T2 inflammation [114]. A likely mechanism for this observation is that dupilumab inhibits the effect of IL-13 on mucin production [115, 116].

BOREAS and NOTUS (n = 939 and 935, respectively) are phase 3, parallel-group, placebo-controlled clinical trials with very similar designs that have reported positive results for dupilumab (300 mg every 2 weeks) over 1 year in COPD patients with evidence of T2 inflammation [12, 13]. The key inclusion criteria were a history of 2 moderate or 1 severe exacerbation in the previous year, chronic bronchitis, using triple therapy prior to the study and BECs ≥ 300 cells/µL at screening. Dupilumab demonstrated efficacy in both the BOREAS and NOTUS studies on the primary endpoint of exacerbations, with 30% and 34% rate reductions, respectively [12, 13].

There were treatment-related improvements in other clinical endpoints including pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (mean difference at 12 weeks of + 83 mL and + 82 mL, in BOREAS and NOTUS, respectively; p < 0.001 for both) [12, 13]. This positive effect of dupilumab on lung function was observed as early as 4 weeks and so is unlikely to be only related to exacerbation prevention. The actions of IL-13 with regard to smooth muscle constriction and hyperplasia is relevant here, with dupilumab blocking these effects. Dupilumab antagonism of IL-13–induced mucus hyper-secretion and airway remodelling may also contribute to lung function improvements in COPD. In the sub-group of patients with a baseline FeNO50 level of ≥ 20 ppb at baseline, improvements in FEV1 at 12 weeks were more striking (mean difference of +124 mL and +141 mL, respectively; p = 0.002 and 0.001, respectively) [12, 13]. Quality of life measured using total Saint George’s respiratory questionnaire (SGRQ) score was also improved with dupilumab compared to placebo (mean difference at 52 weeks of −3.4 in both studies, although this was only statistically significant in the BOREAS study, p = 0.002). Key pathophysiological consequences of blocking signalling via the IL4Rɑ in the treatment of stable COPD are presented in Figure 5, alongside associated clinical outcomes from the phase 3 studies of dupilumab.

Fig. 5.

Blocking signalling via the IL-4Rɑ (dupilumab) in the treatment of stable COPD. ASM airway smooth muscle, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, FeNO fractional exhaled nitric oxide, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 second, HRQoL health-related quality of life, iNOS inducible nitric oxide synthase, IL interleukin, MUC5AC mucin 5AC

Future Opportunities in COPD Pharmacological Treatment

Targeting Type-2 Inflammation

The NOTUS and BOREAS studies demonstrated the positive effects of targeting the cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 in COPD patients with BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL [12, 13]. In contrast, clinical trials using monoclonal antibodies to specifically target eosinophils have produced mostly negative results for the primary endpoint analysis of exacerbation rates. Mepolizumab targets IL-5 while benralizumab targets the IL-5 receptor (IL-5Rα); both reduce the release of eosinophils by the bone marrow, while benralizumab also depletes eosinophils by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity [111, 117]. Mepolizumab and benralizumab have been evaluated in phase 3 studies that enrolled COPD patients with two moderate or one severe exacerbation in the previous year [118, 119]. Mepolizumab focused on COPD patients with BECs ≥ 150 cells/µL at screening or ≥ 300 cells/µL in the previous year for the primary analysis, but it was observed that the benefit on exacerbations was greater at higher BEC in a pre-specified analysis, e.g., there was a 23% exacerbation rate reduction (95% CI 0.63–0.94) at ≥ 300 cells/µL (n = 1136) [119]. For benralizumab, the pre-defined population for the primary endpoint analysis had BEC ≥ 220 cells/µL at screening; a pre-specified exploratory analysis showed that higher BEC, ≥ 3 exacerbations in the previous year and receiving triple inhaled therapy were all factors that increased the treatment effect of benralizumab (n = 145 included in the exploratory analysis) [120]. Subsequent phase 3 studies have been designed and are ongoing, for both mepoluzimab and benralizumab, that have focused on including patients who are more likely to respond to treatment, with higher exacerbation risk and BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL. Studies in patients with asthma have reported that these anti–IL-5 monoclonal antibodies are generally well tolerated, with depletion of eosinophils not leading to adverse pathophysiological consequences [121]. However, in geographical regions where parasitic infection is common, eosinophil depletion may be problematic due to the role of these cells in providing host defence against helminths, for example through the release of granule proteins.

Benralizumab has recently been assessed as an acute intervention in eosinophilic exacerbations of COPD using a primary endpoint of treatment failure defined as a composite of death, admission to hospital, and any need for re-treatment requiring systemic glucocorticoids or antibiotics within 90 days [122]. For COPD and asthma patients (n = 158), compared to standard of care (oral corticosteroids [OCS]), results of treatment with benralizumab (± OCS), showed a significant difference between groups in proportion to treatment failure within 90 days favouring benralizumab; OR 0.26 [95% CI 0.13–0.56], p = 0·0005. Specifically, in COPD patients with a BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL at the time of exacerbation, treatment with benralizumab resulted in a 57% relative reduction in time to treatment failure (p = 0.027). This study is a promising example of how targeted treatments may be used at the time of exacerbations to facilitate recovery and reduce the need for additional treatment.

The Epithelium as a Driver of Airway Inflammation

The airway epithelium acts as a protective barrier against inhaled particulate matter and microbes. Chronic cigarette smoking causes repetitive injury to the airway epithelium, causing pathophysiological changes such as epithelial hyperplasia, reduced barrier function and mucus hypersecretion [123]. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is characterised by small airway remodelling and destruction [105]. Small airway remodelling also occurs with ageing in non-smokers; the features include reduced alveolar tethering associated with increased neutrophil numbers in the alveolar septum and luminal narrowing due to epithelial expansion [124]. In COPD patients, neutrophil-associated alveolar attachment loss is further increased, while increased airway wall thickness due to remodelling is also apparent. These observations highlight that inflammation and remodelling in the airway epithelium, sub-epithelium and alveolar attachments combine to produce the pathophysiological features of COPD.

Alarmins are cytokines that are secreted after cellular injury or external stimulation. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and IL-33 are alarmins that are expressed by bronchial epithelial cells; these play upstream roles in the co-ordination of T2 and non-T2 inflammatory responses [125]. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin promotes the differentiation of T-helper 2 cell through interactions with dendritic cells, while also activating T2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) [126]. Additionally, TSLP can modulate the activity of innate immune cells such as macrophages and neutrophils [127]. Release of TSLP from epithelial cells in vitro is induced by viral infection [128]. The number of cells expressing TSLP mRNA in the epithelial layer are increased in the bronchial biopsies of COPD patients compared to non-smoking controls [129], and protein levels of TSLP are increased in sputum supernatants and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of COPD patients compared to smoking and non-smoking controls [129, 130].

Tezepelumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to TSLP and is used in the treatment of severe asthma [131]. Interestingly, clinical trials in asthma have shown that tezepelumab has clinical benefits in individuals with and without evidence of T2-high biomarker expression, although the effect size was greater in T2-high individuals. However, the clinical benefit in asthma patients with low levels of T2 biomarkers reflects the potential of anti-TSLP treatment across both T2 and non-T2 inflammatory pathways. The phase 2 COURSE study investigated the effects of tezepelumab in COPD patients with ≥2 exacerbations in the previous year who were using triple therapy (n = 333) [132]. While this study failed to meet the primary endpoint in the overall population (17% exacerbation rate reduction, p = 0.10), a key secondary aim was to identify potential responder subgroups. It was observed that the effects of tezepelumab were greater in COPD patients with BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL.

Interleukin-33 binds to the interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 (IL1RL1, also known as ST2) receptor to upregulate IL-5 and IL-13 production by mast cells and ILC2 cells, while interferon (IFN)-γ production by Th1 T-cells is induced by IL-33. Interleukin-33 can also induce NET formation in neutrophils and increase release of IFN-γ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α from macrophages, suggesting that IL-33 biological activity is not confined to T2 inflammatory pathways. Nevertheless, serum and sputum levels of IL-33 are positively correlated with blood and sputum eosinophil numbers, supporting a potential role for IL-33 in T2 inflammation. Interleukin-33 can exert ST2 independent actions following oxidation through RAGE/EGFR receptors in epithelial cells, impairing epithelial wound closure and increasing goblet cell numbers, features which are observed in COPD pathophysiology.

Sputum IL-33 protein levels and the numbers of IL-33–positive small airway epithelial cells are increased in COPD patients compared to controls [133, 134]. Interleukin-33 is strongly expressed by airway basal cells, but IL-33 expression reduces in differentiating intermediate cells and is absent in fully differentiated cell types [135, 136]. In areas of small airway epithelial remodelling in COPD, the numbers of IL-33–positive intermediate cells are higher compared to areas of normal epithelium, indicating increased basal cell differentiation [137].

Itepekimab targets IL-33; while this drug showed no overall effect on exacerbations in a phase 2 study (n = 343), a post hoc analysis demonstrated that ex-smokers have a 42% exacerbation rate reduction (p = 0·006) while there was no benefit in current smokers [138]. Astegolimab targets the ST2 receptor (which binds IL-33). A phase 2 study (n = 81) in COPD patients showed no effect on exacerbations, although the limited sample size likely hindered this evaluation [139]. However, astegolimab significantly improved quality of life. Tozorakimab is a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-33. A phase 2 study in COPD patients (n = 135) with a previous history of ≥ 1 exacerbation showed no significant benefit of tozorakimab versus placebo on the primary endpoint of FEV1 improvement at 12 weeks (24 mL; p = 0.22) [140]. However, the benefit of tozorakimab on lung function and COPDcompEX (a measurement associated with and predictive of exacerbations) was increased in the subgroup of individuals with higher exacerbation risk (≥ 2 previous exacerbations).

These early-phase studies with monoclonal antibodies targeting the IL-33 pathway have enabled the design of ongoing late-phase trials, which will further investigate whether anti-IL-33 treatment is less effective in current smokers. Any such treatment modification may be due to reduced IL-33 expression in the basal epithelial cells of current smokers. Additionally, anti-IL33 treatments reduce blood and sputum eosinophil counts [138, 141, 142], suggesting that these drugs may have greater efficacy in COPD patients with evidence of T2 inflammation. Consequently, it remains to be determined whether these drugs have broad anti-inflammatory effects or are more suitable for COPD patients with higher levels of T2 biomarkers.

Pulmonary Microbiome

Cohort studies have demonstrated an imbalance (dysbiosis) in the pulmonary microbiome in COPD patients with as many as 76.7% of patients showing increased abundance of potentially pathogenic bacteria in the stable state [17]. When compared to healthy individuals, COPD patients demonstrate reduced diversity and increased abundance of Proteobacteria including Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis [143–145]. Dysbiosis of the pulmonary microbiome in stable COPD patients is associated with endotypes of airway inflammation; sputum neutrophil numbers are correlated with increased airway bacterial load while eosinophil numbers are inversely correlated with airway bacterial load [146–148]. This relationship is most striking in COPD patients colonised with H. influenzae who display increased neutrophil and decreased eosinophil counts compared to non-colonised individuals [25, 148, 149]. Whilst it is unclear why COPD patients with elevated eosinophilic inflammation have reduced airway pathogenic bacteria, it is possible that eosinophils themselves are contributing to bacterial clearance, or that an environment characterised by increased T2 inflammation is unfavourable to colonisation by bacteria such as H. influenzae [17]. For example, pulmonary levels of H. influenzae-specific IgA and IgM are higher in eosinophilic compared to non-eosinophilic COPD patients, suggesting that a high T2 environment favours immunoglobulin-mediated clearance of H. influenzae [150].

There is evidence from cohort studies and clinical trials of stable COPD patients that ICS use reduces airway bacterial diversity and increases abundance of pathogenic species, particularly H. influenzae [9, 151, 152]. These changes occur in COPD patients with lower BEC [153], suggesting the risks of ICS use can be mitigated by targeting COPD patients with higher BEC. This raises the important issue of how novel treatments including monoclonal antibodies may affect the airway microbiome in COPD patients. In a sub-group of COPD patients (n = 94) from the GALATHEA study, the effect of benralizumab on the airway microbiome was examined in sputum by 16sRNA analysis [154]. Compared to baseline, there were no significant changes in the composition or diversity of the airway microbiome at Weeks 24 and 56 following benralizumab treatment, with no differences between placebo and active treatment. Whilst limited in sample size, this study suggests that direct depletion of eosinophils does not significantly impact the airway microbiome in COPD patients with T2 inflammation.

The use of agents that specifically aim to modify the pulmonary microbiome in COPD patients, such as probiotics, is receiving attention. Evidence from COPD animal models suggests administration of probiotics, including Lactobacillus, via intranasal or oral routes can reduce airway inflammation and lung damage [155]. The therapeutic effects observed after oral administration implicate the gut-lung-axis in COPD pathophysiology, with evidence that dysbiosis of gut microbiome in COPD patients also occurs [156]. Correcting the gut microbiome may have beneficial effects on the lung microbiome. Whilst the mechanisms of action are unclear, this may be related to compromised mucosal defence and increased systemic inflammation.

Overall, the presence of dysbiosis in COPD, coupled with the fact that some COPD patients are colonised with pathogenic bacteria in the stable state and experience exacerbations due to these bacteria [157], strongly implicates the pulmonary microbiome in pathophysiology of this disease and the associated clinical outcomes. The associations between the microbiome and inflammation markers suggest that manipulation of one of these components may modify the other.

Making Progress: The Next Steps

While recently, there has been considerable progress in the pharmacological management of COPD, the key issues and next steps need to be defined as this will enable the continued development of novel treatments and optimisation of existing treatments. In the opinion of the authors, progress can be made by addressing the following key issues.

Optimising the Use of Inhaled Treatments

Evidence from clinical trials supports the precision medicine approach to the use of ICS, guided by clinical characteristics and BEC to identify likely responders and non-responders to inhaled triple therapy [80]. However, in real-world clinical practice there are delays in the initiation of triple therapy for appropriate patients. Given the evidence that triple therapy can reduce mortality in high-exacerbation risk individuals with T2 inflammation [11], there is a need to identify these individuals and ensure appropriate treatment is given. The current GOLD recommendations suggest that triple therapy is considered as a treatment option for initial pharmacological management in patients with both high exacerbation risk and high BEC, but acknowledge the lack of direct evidence to support this recommendation [15]. This is a future need for evidence generation, as it will enable an earlier and more aggressive intervention approach, rather than a slower stepwise approach, which often causes a delay in the time taken to receive the optimum treatment (triple therapy). In addition, the benefits of ICS on cardiovascular risk should be further explored, as this is an opportunity to further understand and optimise the use of triple therapy.

Ensifentrine is a novel bronchodilator that has demonstrated improvements in lung function, dyspnoea and quality of life [14]. However, the clinical trials did not investigate the effect of ensifentrine in addition to LAMA/LABA or triple therapy, and the effect of ensifentrine in a high exacerbation risk population has not yet been defined (Fig. 4). While these remain gaps in knowledge, the GOLD report has recommended that ensifentrine may be used to treat dyspnoea, but there is insufficient evidence to support a positive recommendation for exacerbation prevention [15]. Further clinical trials are needed to enable our understanding of the effect of ensifentrine in COPD patients with high exacerbation risk. The potential anti-inflammatory effects of ensifentrine are not well understood, but may help to target exacerbation prevention. Nevertheless, physicians may have the opportunity to prescribe ensifentrine to such patients and evaluate clinical benefit on an individual basis. Ensifentrine is currently marketed as a nebulised formulation; the development of other formulations such as a metered dose or dry powder inhaler, may facilitate wider patient access.

An important advance in the last decade has been the increased use of double- or triple-combination inhalers to decrease the number of inhalers that a patient uses [77–79]. This reduction can avoid the situation where a patient uses multiple inhalers with different operating requirements including inhalation rate. The simplification afforded by combination inhalers can increase the likelihood of the correct inhalation procedure being followed and increase adherence [158]. In future, it would be preferable that any novel inhaled drugs, such as ensifentrine, do not create complexity for the patient by increasing the number of inhalers with different operating instructions. Ideally, novel molecules could be added to existing treatments to make combination inhalers, requiring optimisation of co-formulation for inhalation. It is also important that novel combination inhalers ensure that recent advances in inhalation technology are used to optimise the drug fraction delivered to the lungs [159].

Optimising the Use of Biological Treatments

The successful clinical trial programme with dupilumab has led to optimism that other biological treatments, currently being investigated in phase 3 studies, may in future be licensed for the treatment of COPD. While some treatments are specifically targeted at T2 inflammation, it remains to be seen whether anti-alarmin treatments can have broader actions. There are also monoclonal antibodies in clinical development that have two or three active sites, known as bispecific or trispecific molecules, respectively [160]. These have commonly been designed to include one binding site for IL-13 plus another targeting an alarmin, with the aim of addressing T2 inflammation plus the potential for impacting non-T2 mechanisms.

The design and inclusion criteria of the clinical trials with biologics have to date focused on the selected group of COPD patients with moderate to severe disease and experiencing multiple exacerbations. These patients already have considerable lung pathology including small airway remodelling and destruction with or without emphysema. There is potential for biological treatments to have beneficial effects in other COPD subgroups. There is increasing recognition of the need to understand the earlier stages of COPD, in order to identify younger individuals with high risk but less lung damage who may benefit from therapeutic interventions. Moving our focus towards slowing or stopping disease progression at an earlier stage is the goal.

The concept of targeting disease activity is well established in other chronic inflammatory diseases. Inflammatory processes that can be reversed with treatment are considered to be active components of the disease [161, 162]. Earlier interventions in the natural history of the disease that targets disease activity have the potential to prevent or reduce permanent end-organ damage. For example, a treatment target in rheumatoid arthritis is to suppress inflammation and joint swelling in order to prevent the subsequent development of joint deformities [163]. The state of low disease activity (LDA) is a target in chronic inflammatory diseases as this prevents disease progression, and minimises the risk of permanent end-organ damage, which causes chronic symptoms. The term ‘remission’ applies to the scenario where LDA has been achieved and there is an absence of symptoms (or a very low symptom burden) [164–166]. Remission can only be achieved in COPD if clinical trials move towards generating evidence in the earlier stages of disease where there is less lung damage, otherwise COPD patients will always have a significant symptom burden despite optimised treatment. However, LDA remains a worthwhile treatment goal even if remission cannot be achieved.

The current and future use of biologics in COPD clinical practice should focus on the treatment target of LDA, in line with the way that other chronic inflammatory diseases are managed. While we currently lack biomarkers of disease activity in COPD, exacerbations can serve as a surrogate. It has been proposed that a treatment target for COPD is no exacerbations alongside no worsening of lung function or symptoms at follow up [167]; this indicates a stable state associated with LDA. While the concepts of LDA and disease stability need to be further developed in COPD, these are practical goals that can provide treatment targets for physicians and patients.

Exacerbation events are currently defined by treatment administered by the physician or the need for hospitalisation. This subjective definition, with the possibility that some events are missed, has led to proposals for a more objective definition of exacerbations [168]. Exacerbations cause increased cardiovascular and mortality risk [96, 169], meaning that any reduction in exacerbations on an individual basis is likely to be clinically beneficial. However, using exacerbations to assess the benefit of a novel treatment in an individual COPD patient with infrequent exacerbation events (e.g., 1/year) presents practical difficulties. Developing other measurements related to disease activity, such as biomarkers and imaging, and using symptoms and lung function assessments may enable a more holistic and comprehensive assessment of the effects of novel interventions on disease activity [167].

The use of biological treatments during an exacerbation is a promising avenue. This may increase the (appropriate) access that patients have to biologics, as well as targeting inflammation processes at their peak and therefore most dangerous in terms of clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

There have been considerable advances in the landscape of COPD pharmacological treatment, with the implementation of precision medicine for the use of ICS alongside the successful registration of dupilumab and ensifentrine as novel treatments. There are other monoclonal antibodies in late-phase trials, which may further enhance the treatment choice available. The challenge of patient selection for these novel treatments is key. There are new concepts emerging that will improve the use of inhaled and systemic treatments. Among these, moving treatments towards earlier stages of disease coupled with the identification and targeting of patients with higher risk, are crucial.

Acknowledgements

DS is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Declarations

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding for this paper.

Conflict of interest

DS has received personal fees from Adovate, Aerogen, Almirall, Apogee, Arrowhead, AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, CONNECT Biopharm, Covis, CSL Behring, DevPro Biopharma LCC, Elpen, Empirico, EpiEndo, Genentech, Generate Biomedicines, GlaxoSmithKline, Glenmark, Kamada, Kinaset Therapeutics, Kymera, Menarini, MicroA, OM Pharma, Orion, Pieris Pharmaceuticals, Pulmatrix, Revolo, Roivant Sciences, Sanofi, Synairgen, Tetherex, Teva, Theravance Biopharma, Upstream and Verona Pharma. AGM has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi and has received non-financial support from Verona pharma, all not related to this work. AH has received honoraria for lecturing from Chiesi. AB has no conflicts to declare.

Availability of data

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

DS, AH, AM and AB contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Collaborators GCoD. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403(10440):2100–32. 10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Collaborators GCoD. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403(10440):2133–61.10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00757-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Sin DD, Ron D, Agusti A, et al. Air pollution and COPD: GOLD 2023 committee report. Eur Respir J. 2023. 10.1183/13993003.02469-2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agusti A, Celli BR, Criner GJ, et al. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease 2023 report: GOLD executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2023. 10.1183/13993003.00239-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange P, Celli B, Agustí A, et al. Lung-function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):111–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1411532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agustí A, Bafadhel M, Beasley R, et al. Precision medicine in airway diseases: moving to clinical practice. Eur Respir J. 2017. 10.1183/13993003.01655-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathioudakis AG, Janssens W, Sivapalan P, et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: in search of diagnostic biomarkers and treatable traits. Thorax. 2020;75(6):520–7. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-214484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathioudakis AG, Vestbo J, Singh D. Long-acting bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: which one(s), how, and when? Clin Chest Med. 2020;41(3):463–74. 10.1016/j.ccm.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lea S, Higham A, Beech A, Singh D. How inhaled corticosteroids target inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2023. 10.1183/16000617.0084-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipson DA, Crim C, Criner GJ, et al. Reduction in all-cause mortality with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(12):1508–16. 10.1164/rccm.201911-2207OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez FJ, Rabe KF, Ferguson GT, et al. Reduced all-cause mortality in the ETHOS trial of budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter, parallel-group study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(5):553–64. 10.1164/rccm.202006-2618OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatt SP, Rabe KF, Hanania NA, et al. Dupilumab for COPD with blood eosinophil evidence of type 2 inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(24):2274–83. 10.1056/NEJMoa2401304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatt SP, Rabe KF, Hanania NA, et al. Dupilumab for COPD with type 2 inflammation indicated by eosinophil counts. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(3):205–14. 10.1056/NEJMoa2303951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anzueto A, Barjaktarevic IZ, Siler TM, et al. Ensifentrine, a novel phosphodiesterase 3 and 4 inhibitor for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trials (the ENHANCE trials). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;208(4):406–16. 10.1164/rccm.202306-0944OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.GOLD. Global strategy for prevention, diagnosis and management of COPD: 2025 Report. 2025.

- 16.Arnold IC, Munitz A. Spatial adaptation of eosinophils and their emerging roles in homeostasis, infection and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2024;24(12):858–77. 10.1038/s41577-024-01048-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higham A, Beech A, Singh D. The relevance of eosinophils in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: inflammation, microbiome, and clinical outcomes. J Leukoc Biol. 2024;116(5):927–46. 10.1093/jleuko/qiae153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolkhir P, Akdis CA, Akdis M, et al. Type 2 chronic inflammatory diseases: targets, therapies and unmet needs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22(9):743–67. 10.1038/s41573-023-00750-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keegan AD, Leonard WJ, Zhu J. Recent advances in understanding the role of IL-4 signaling. Fac Rev. 2021;10:71. 10.12703/r/10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pelaia C, Vatrella A, Busceti MT, et al. Severe eosinophilic asthma: from the pathogenic role of interleukin-5 to the therapeutic action of mepolizumab. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2017;11:3137–44. 10.2147/dddt.S150656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Espinosa K, Bossé Y, Stankova J, Rola-Pleszczynski M. CysLT1 receptor upregulation by TGF-beta and IL-13 is associated with bronchial smooth muscle cell proliferation in response to LTD4. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(5):1032–40. 10.1067/mai.2003.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H, Fahy JV. The Cytokines of Asthma. Immunity. 2019;50(4):975–91. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beech A, Singh D. Eosinophils and COPD. In: Wedzicha JA, Allinson JP, Calverley PMA, eds. COPD in the 21st Century (ERS Monograph). Sheffield, European Respiratory Society, 2024:149–167. 10.1183/2312508X.10007023.

- 24.Kolsum U, Damera G, Pham TH, et al. Pulmonary inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with higher blood eosinophil counts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(4):1181–4. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beech A, Jackson N, Singh D. Identification of COPD inflammatory endotypes using repeated sputum eosinophil counts. Biomedicines. 2022. 10.3390/biomedicines10102611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beech A, Higham A, Booth S, Tejwani V, Trinkmann F, Singh D. Type 2 inflammation in COPD: is it just asthma? Breathe (Sheff). 2024;20(3):230229. 10.1183/20734735.0229-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.George L, Taylor AR, Esteve-Codina A, et al. Blood eosinophil count and airway epithelial transcriptome relationships in COPD versus asthma. Allergy. 2020;75(2):370–80. 10.1111/all.14016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higham A, Beech A, Wolosianka S, et al. Type 2 inflammation in eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Allergy. 2021;76(6):1861–4. 10.1111/all.14661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stockley RA, Halpin DMG, Celli BR, Singh D. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease biomarkers and their interpretation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(10):1195–204. 10.1164/rccm.201810-1860SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulvanny A, Pattwell C, Beech A, Southworth T, Singh D. Validation of sputum biomarker immunoassays and cytokine expression profiles in COPD. Biomedicines. 2022. 10.3390/biomedicines10081949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller BE, Tal-Singer R, Rennard SI, et al. Plasma fibrinogen qualification as a drug development tool in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Perspective of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease biomarker qualification consortium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(6):607–13. 10.1164/rccm.201509-1722PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh D, Criner GJ, Dransfield MT, et al. InforMing the PAthway of COPD Treatment (IMPACT) trial: fibrinogen levels predict risk of moderate or severe exacerbations. Respir Res. 2021;22(1):130. 10.1186/s12931-021-01706-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolsum U, Southworth T, Jackson N, Singh D. Blood eosinophil counts in COPD patients compared to controls. Eur Respir J. 2019. 10.1183/13993003.00633-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartl S, Breyer MK, Burghuber OC, et al. Blood eosinophil count in the general population: typical values and potential confounders. Eur Respir J. 2020. 10.1183/13993003.01874-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watz H, Tetzlaff K, Wouters EF, et al. Blood eosinophil count and exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids: a post-hoc analysis of the WISDOM trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(5):390–8. 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamad GA, Cheung W, Crooks MG, Morice AH. Eosinophils in COPD: how many swallows make a summer? Eur Respir J. 2018. 10.1183/13993003.02177-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yun JH, Lamb A, Chase R, et al. Blood eosinophil count thresholds and exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(6):2037-47 e10. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeiger RS, Tran TN, Butler RK, et al. Relationship of blood eosinophil count to exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):944-54 e5. 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Long GH, Southworth T, Kolsum U, et al. The stability of blood eosinophils in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):15. 10.1186/s12931-020-1279-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Southworth T, Beech G, Foden P, Kolsum U, Singh D. The reproducibility of COPD blood eosinophil counts. Eur Respir J. 2018. 10.1183/13993003.00427-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Durrington HJ, Gioan-Tavernier GO, Maidstone RJ, et al. Time of day affects eosinophil biomarkers in asthma: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(12):1578–81. 10.1164/rccm.201807-1289LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Rossem I, Hanon S, Verbanck S, Vanderhelst E. Blood eosinophil counts in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: adding within-day variability to the equation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(6):727–9. 10.1164/rccm.202105-1162LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Higham A, Singh D. Stability of eosinophilic inflammation in COPD bronchial biopsies. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(6):2004167. 10.1183/13993003.04167-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baraldi F, Bartlett-Pestle S, Allinson JP, et al. Blood eosinophil count stability in COPD and the eosinophilic exacerbator phenotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2025. 10.1164/rccm.202407-1287RL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Çolak Y, Afzal S, Marott JL, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG, Lange P. Type-2 inflammation and lung function decline in chronic airway disease in the general population. Thorax. 2024;79(4):349–58. 10.1136/thorax-2023-220972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee SH, Ahn KM, Lee SY, Kim SS, Park HW. Blood eosinophil count as a predictor of lung function decline in healthy individuals. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(1):394-9.e1. 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan WC, Bourbeau J, Nadeau G, et al. High eosinophil counts predict decline in FEV(1): results from the CanCOLD study. Eur Respir J. 2021. 10.1183/13993003.00838-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong YS, Park HY, Ryu S, et al. The association of blood eosinophil counts and FEV(1) decline: a cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2024. 10.1183/13993003.01037-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murugesan N, Saxena D, Dileep A, Adrish M, Hanania NA. Update on the role of FeNO in asthma management. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023. 10.3390/diagnostics13081428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Higham A, Beech A, Dean J, Singh D. Exhaled nitric oxide, eosinophils and current smoking in COPD patients. ERJ Open Res. 2023. 10.1183/23120541.00686-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berry MA, Shaw DE, Green RH, Brightling CE, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. The use of exhaled nitric oxide concentration to identify eosinophilic airway inflammation: an observational study in adults with asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(9):1175–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Escamilla-Gil JM, Fernandez-Nieto M, Acevedo N. Understanding the cellular sources of the fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) and its role as a biomarker of type 2 inflammation in asthma. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:5753524. 10.1155/2022/5753524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Annangi S, Nutalapati S, Sturgill J, Flenaugh E, Foreman M. Eosinophilia and fractional exhaled nitric oxide levels in chronic obstructive lung disease. Thorax. 2022;77(4):351–6. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-214644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alcazar-Navarrete B, Ruiz Rodriguez O, Conde Baena P, Romero Palacios PJ, Agusti A. Persistently elevated exhaled nitric oxide fraction is associated with increased risk of exacerbation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2018. 10.1183/13993003.01457-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh D. New combination bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current evidence and future perspectives. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(5):695–708. 10.1111/bcp.12545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sears MR. Adverse effects of beta-agonists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(6):S322–8. 10.1067/mai.2002.129966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barnes PJ. The role of anticholinergics in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 2004;117(Suppl 12A):24s–32s. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ikeda T, Anisuzzaman AS, Yoshiki H, et al. Regional quantification of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and beta-adrenoceptors in human airways. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166(6):1804–14. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kew KM, Mavergames C, Walters JA. Long-acting beta2-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(10):CD010177. 10.1002/14651858.CD010177.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koch A, Pizzichini E, Hamilton A, et al. Lung function efficacy and symptomatic benefit of olodaterol once daily delivered via Respimat(R) versus placebo and formoterol twice daily in patients with GOLD 2–4 COPD: results from two replicate 48-week studies. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:697–714. 10.2147/COPD.S62502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Donohue JF, Maleki-Yazdi MR, Kilbride S, Mehta R, Kalberg C, Church A. Efficacy and safety of once-daily umeclidinium/vilanterol 62.5/25 mcg in COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107(10):1538–46. 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bateman ED, Chapman KR, Singh D, et al. Aclidinium bromide and formoterol fumarate as a fixed-dose combination in COPD: pooled analysis of symptoms and exacerbations from two six-month, multicentre, randomised studies (ACLIFORM and AUGMENT). Respir Res. 2015;16(1):92. 10.1186/s12931-015-0250-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maltais F, Bjermer L, Kerwin EM, et al. Efficacy of umeclidinium/vilanterol versus umeclidinium and salmeterol monotherapies in symptomatic patients with COPD not receiving inhaled corticosteroids: the EMAX randomised trial. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):238. 10.1186/s12931-019-1193-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferguson GT, Karpel J, Bennett N, et al. Effect of tiotropium and olodaterol on symptoms and patient-reported outcomes in patients with COPD: results from four randomised, double-blind studies. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):7. 10.1038/s41533-016-0002-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singh D, Gaga M, Schmidt O, et al. Effects of tiotropium + olodaterol versus tiotropium or placebo by COPD disease severity and previous treatment history in the OTEMTO® studies. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):73. 10.1186/s12931-016-0387-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kerwin EM, Jones PW, Bjermer LH, et al. How can the findings of the EMAX trial on long-acting bronchodilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease be applied in the primary care setting? Chron Respir Dis. 2023;20:14799731231202256. 10.1177/14799731231202257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maleki-Yazdi MR, Singh D, Anzueto A, Tombs L, Fahy WA, Naya I. Assessing short-term deterioration in maintenance-naïve patients with COPD receiving umeclidinium/vilanterol and tiotropium: a pooled analysis of three randomized trials. Adv Ther. 2017;33(12):2188–99. 10.1007/s12325-016-0430-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ferguson GT, Fležar M, Korn S, et al. Efficacy of tiotropium + olodaterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by initial disease severity and treatment intensity: a post hoc analysis. Adv Ther. 2015;32(6):523–36. 10.1007/s12325-015-0218-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Buhl R, de la Hoz A, Xue W, Singh D, Ferguson GT. Efficacy of tiotropium/olodaterol compared with tiotropium as a first-line maintenance treatment in patients with COPD who are naïve to LAMA, LABA and ICS: pooled analysis of four clinical trials. Adv Ther. 2020;37(10):4175–89. 10.1007/s12325-020-01411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]