Abstract

Background

Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) is frequently associated with moderate to severe postoperative pain, necessitating effective analgesic strategies to enhance patient comfort and facilitate recovery. Identifying effective pain management methods after ACLR is crucial. This study aims to explore the best analgesia method with the local infiltration analgesia (LIA) and femoral nerve block (FNB) after ACLR.

Methods

Cochrane Library databases, PubMed, MEDLINE and Embase were searched from inception to April 2024 with the following terms: “anterior cruciate ligament” AND “reconstruction” AND “femoral nerve block” AND “local infiltration analgesia” AND “pain score” AND “morphine consumption” AND “analgesia duration” AND “complication”.

Results

A total of 8 Level 1 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in Meta analysis. The pain score of the FNB group was significantly lower than that of the LIA group at 8 to 12 h after the operation (MD = 1.78; 95% CI, [0.53, 3.03]; P = 0.005). There was no significant difference in pain scores between the two groups at 0 to 4, 4 to 8, and 12 to 24 h postoperatively. Within 24 h after surgery, there was no significant difference in intravenous morphine equivalent consumption between the two groups (MD = 3.76; 95% CI, [-0.82, 8.33]; P = 0.11). In terms of analgesic duration, there was also no significant difference between the two groups (MD = -3.03; 95% CI, [-7.34, 1.28]; P = 0.17). However, the incidence of nausea in the LIA group was higher than that in the FNB group (OR = 2.06; 95% CI, [1.03, 4.14]; P = 0.04).

Conclusion

The FNB is superior to LIA for intraoperative control of postoperative pain in the first 8 to 12 h after ACLR. But there was no significant difference in pain control at other time points, morphine consumption, and analgesic duration between the two groups within 24 h after surgery. The LIA group had a higher incidence of nausea within 24 h after surgery.

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, Local infiltration analgesia, Femoral nerve block, Pain

Introduction

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a critical structure in the knee joint, and injuries to this ligament are prevalent, particularly among athletes and active individuals. The incidence of ACL injuries has been reported to range from 68 to 100 per 100,000 individuals annually, with a significant number requiring surgical intervention, specifically anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction [1]. ACLR is an effective, safe, and cost—effective method. However, patients commonly experience moderate to severe postoperative pain, particularly within the first 24—48 h. Without proper pain management, often achieved through narcotic analgesia, the recovery process may be prolonged, and healthcare costs could increase [2]. Traditional opioid-based analgesia, while effective, poses risks of side effects and dependency, prompting the need for alternative pain management strategies. Pain management in post-ACLR patients remains a significant challenge, often requiring multimodal strategies [3].

Regional anesthesia is commonly employed for postoperative analgesia in ACLR outpatient clinics and has been shown to reduce unplanned hospitalization, discharge time and opioid consumption [4, 5]. FNB is a commonly used regional anesthetic technique for reducing postoperative pain in ACLR patients [6]. In a specific study where FNB was added to spinal anesthesia [7], it showed better analgesic effects and lower opioid consumption. However, it cannot be simply generalized that FNB has superior analgesic efficacy and lower opioid consumption compared to all standard analgesia methods. Nevertheless, some reports suggest that there may be numerous postoperative adverse events associated with FNB, such as antalgic ambulation, quadriceps weakness, nausea, numbness, partial motor block, and an increased risk of falls. However, few specific studies have specifically investigated these side effects [8–11]. Additionally, some research has indicated functional deficits persisting up to six months post-surgery due to FNB [12, 13].

LIA developed over 40 years ago, involves the injection of local anesthetics directly into the surgical site [14, 15]. Its simplicity and the ease with which it allows for leg movement are primary reasons for its widespread adoption by orthopedic surgeons [16]. Recent studies on ACLR patients have shown that LIA could also alleviate pain and expedite recovery [2, 17]. Furthermore, these strategies have been reported to limit postoperative opiate consumption and reduce the incidence of postoperative complications [18–20].

Several prior studies have sought to compare the efficacy of LIA and FNB in ACLR patients, but the results have been inconsistent [2, 17, 21, 22]. Due to the limited sample size, these trials have not yielded definitive conclusions. A previous systematic review and meta-analysis exploring the analgesic efficacy of LIA versus FNB after ACLR concluded that FNB provides superior postoperative analgesia compared to LIA. However, this study had limitations including low quality and considerable heterogeneity among the included literature in the combined data analysis [23]. Consequently, our review was to conduct a meta-analysis of all level 1 RCTs comparing subjective pain scores, morphine consumption, analgesic duration and the incidence of complications within the first 24 h after primary ACLR in patients receiving LIA versus FNB. Through this study, a more specific analgesic regimen can be provided for post-ACLR patients, so as to facilitate early discharge, quicker recovery of related functions, and earlier return to sports activities. It is hypothesized that the efficacy of LIA in managing early postoperative pain is no less than that of FNB.

Methods

Data sources and search strategies

According to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines and checklist [24], the review was conducted. All literature about the use of LIA or FNB for patients with their primary ACLR published from inception to April 15, 2024 was identified. Two authors conducted a literature search in April 15, 2024 independently using the following databases: the Cochrane Library databases, PubMed, MEDLINE and Embase. Each search contained a different combination of the following terms: “anterior cruciate ligament” AND “reconstruction” AND “femoral nerve block” AND “local infiltration analgesia” AND “pain score” AND “morphine consumption” AND “analgesia duration” AND “complication”. Systematic review registration was approved on May 16, 2024 with the PROSPERO international register of systematic reviews (submission ID: CRD42021249149).

Selection criteria

Trials were included based on the PICOS criteria (i.e., patients, intervention, comparator, outcome, study design). Inclusion criteria consisted of (1) patients who underwent their initial ACLR surgery; (2) studies reporting that undergoing initial ACLR surgery with LIA and FNB; (3) studies about pain-related outcomes at rest with pain scores (pain scores which reported as verbal, visual or numerical rating scales [NRS] were all converted to a standardised 0–10 scale, known as visual analog scale [VAS], in the same way, if using a VAS of 0–100 mm for pain assessment, it was also converted to a 0–10 scale) [17], intravenous (i.v.) morphine consumption (all opioids were converted into i.v. equivalent doses of morphine [MEQs]) [25, 26], postoperative analgesic duration (the time from the end of surgery to first requirement of morphine) [27] and the incidence of complication within the first 24 h after ACLR surgery (eg, nausea and vomiting, sedation, and pruritis); (4) level 1 RCTs studies.

Studies of LIA include only those in which local injection is given injections pre- or intraoperatively (i.e., before or immediately after wound closure).

Exclusion criteria included non-English articles, level 2–5 evidence studies, studies that examined outcomes in patients treated with combined anesthesia, studies that provided postoperative LIA, studies that did not report results within 24 h after surgery, studies with a sample size of fewer than five patients, and studies that had only abstracts but no full texts.

Study selection

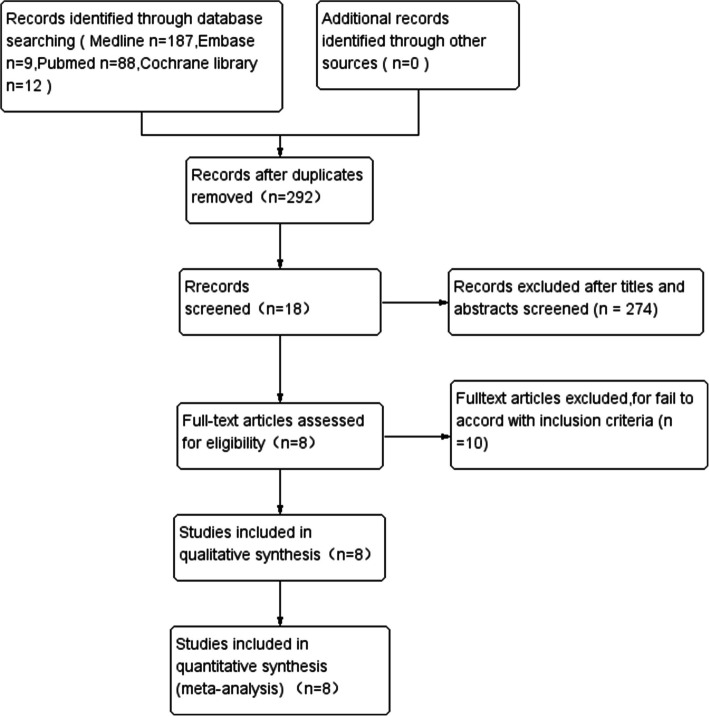

Two independent reviewers performed the initial search records. The titles and abstracts were independently screened by the two reviewers. The full text will be read if reviewers meet the predefined inclusion criteria. The flowchart of study selection is shown in Fig. 1. After application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 8 studies were identified for analysis. To ensure that all available studies were identified, references cited in the included articles were cross-referenced for inclusion if they were overlooked during the initial search, during which no further studies were identified.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart for inclusion in the study

Data extraction

Two investigators independently extracted data from the included literature, including the first author’s last name, year of publication, sample size, sex ratio, age, and detailed implementation methods for each group. General data characteristics for all included studies will be summarized in the same standardized collection form. Any disagreement between the investigators will be resolved through discussion. When necessary, a third researcher steps in to help reach a consensus with all the investigators. For example, during the extraction of data on the type of local anesthetic used in a study, one investigator might interpret it as ropivacaine 0.2% based on the text, while the other thought it could be 0.5% due to a misprint in the table. In such a case, after initial discussion, they would consult a third researcher. The third researcher would carefully review the entire study, including any additional information in the methods or results sections. If there was still uncertainty, they would search for erratum or contact the original study authors for clarification. This approach ensures the accuracy of the extracted data.

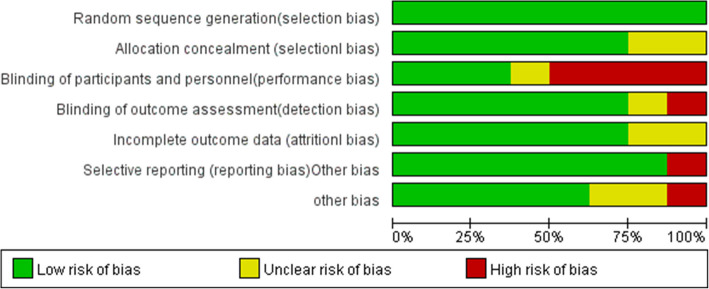

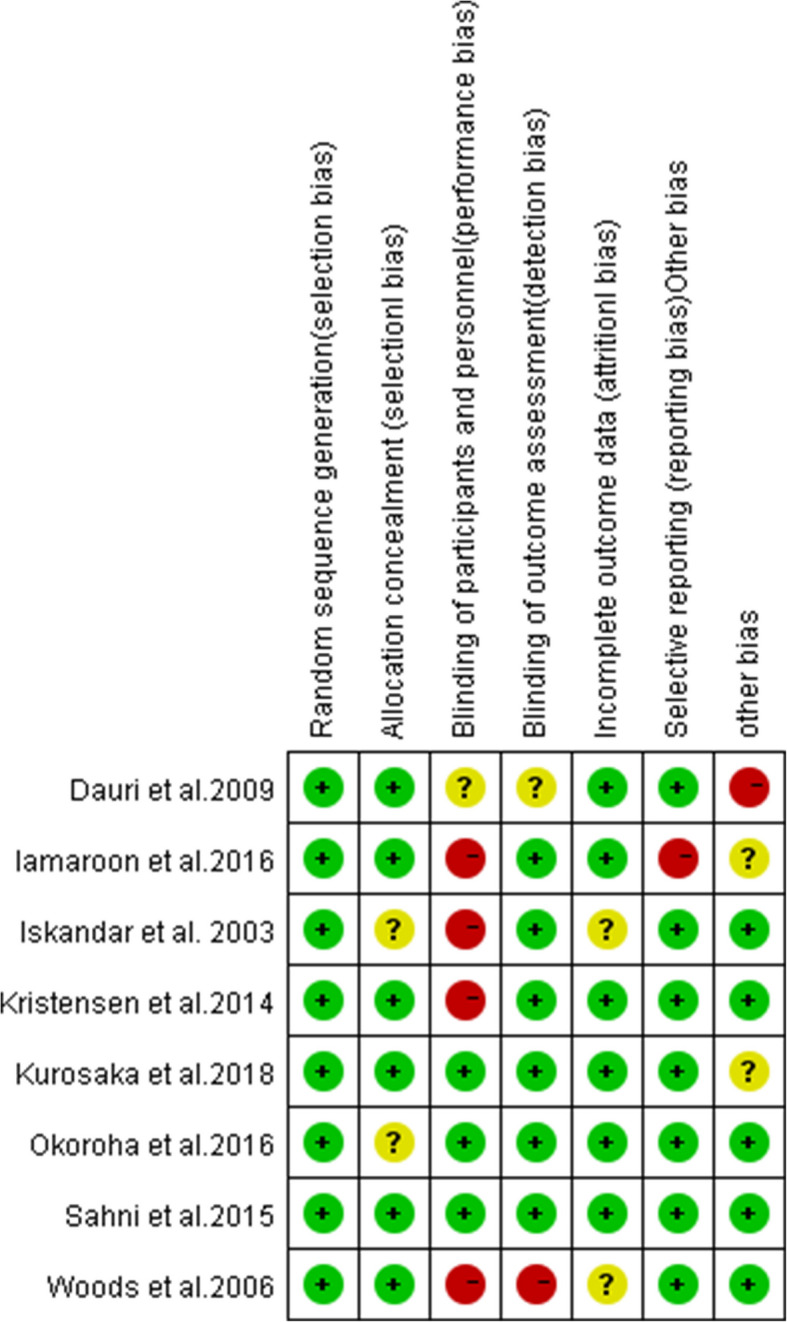

Risk of bias assessment

The cochrane risk of bias tool was used to evaluate the risk of bias of each RCT by another two authors. Each article will be evaluated according to the following seven items: allocation concealment, double blindness, incomplete outcome, selective reporting, randomization process, and measurements of results and other bias. Each item will be described as a low risk of bias, a high risk of bias, or an unclear risk of bias [28].

Statistical analysis

Review Manager 5.3 will be performed for all statistical analyses. Mean difference (MD) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CIs) will be used for assessing all continuous data. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs will be used to calculate dichotomous data. P-value < 0.05 is regarded as statistically significant. Depending on the value of P (PQ) and I2 with the standard χ2 test and I2 statistic, the statistics and quantity of heterogeneity will be estimated, respectively. When I2 ≥ 50% and P < 0.1, the heterogeneity will be considered to be significant, and then a random effect model will be adopted. Otherwise, a fixed-effect model will be chosen [29]. Publication bias was not assessed because it was not considered necessary if there were < 10 studies in a comparison.

Results

Search results

A total of 8 level RCTs were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis, and the rest were excluded for various reasons, as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1, with a number of 566 participants were included in the review [17, 21, 22, 27, 30–33]. Table 1 shows the general data characteristics and the primary intraoperative anesthetic modality of the included literature. According to our assessment (Figs. 2 and 3), the risk of bias for all trials was low. In all of the included studies, there were no significant differences in patient age or gender. Research data were derived from texts, tables, and charts in the included literature. One is approximated by the median and range [30].

Table 1.

General data characteristics of included trials

| Reference | LIA/FNB | LIA | FNB | Anesthetic strategy | Postoperative analgesia | Primary outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| patients (n) | Gender male | Age (mean) | Solution | Technique | Solution | Technique | ||||

| Dauri et al. 2009 [32] | 25/25 | 18/16 | 25/25 | Ropivacaine 0.2% | Continuous infusion through an intra-articular and a subcutaneous catheter witha a rate of 2 ml/h for each catheter | A single injection of 0.75% ropivacaine 25 mL and 30 μg clonidine for FNB was followed by continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine 7 mL/h | Nerve stimulation | Single-shot FNB and sciatic nerve block with 0.75% ropivacaine 25 mL, clonidine 30 μg and combined with propofol sedation | Intravenous (i.v.) patient-controlled analgesia with morphine, ketorolac as rescue analgesic | Pain score |

| Iamaroon et al. 2016 [21] | 20/20 | 20/18 | 28.2/27.3 | Bupivacaine 0.25% | 15 ml entered the knee joint, and 5 ml infiltrated along the incision and portal vein | Bupivacaine 0.25% 20 ml for Single-shot FNB | Ultrasound guided | Spinal anesthesia with hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% 3 ml | Acetaminophen, celecoxib, i.v. morphine | Duration of analgesia |

| Iskandar et al. 2003 [27] | 40/40 | 31/20 | 28.3/26.8 | 1% 20 ml Ropivacaine | Intra-articular infiltration | 1% 20 ml Ropivacaine | Nerve stimulation | General anesthesia | Ketoprofen, Proparacetamol, ketoprofen, i.v. patient-controlled analgesia of morphine | Duration of analgesia |

| Kristensen et al. 2014 [17] | 28/27 | 21/19 | 29.3/25.6 | Ropivacaine 0.2% 40 ml with adrenaline 5 μg/ml | Infiltration of the harvest site followed by an intra-articular injection | Ropivacaine 0.2% 20 ml | Ultrasound guided | General anesthesia | Acetaminophen, i.v. fentanyl, oral morphine | Pain score |

| Kurosaka et al. 2018 [31] | 69/60 | 27/28 | 27.1/25.5 | 40 mL 7.5 mg/mL of ropivacaine,0.5 mL 10 mg/mL of morphine hydrochloride hydrate, 1 mL 40 mg of methylprednisolone, 2.5 mL 20 mg/mL of ketoprofen | Ten ml into infrapatellar fat pad, 12 mL into medial and lateral synovial/capsule above the meniscus,12 mL into every visible region around the hamstring harvest site, 5 mL into subcuticular tissues of portals, and 5 mL into subcuticular tissues of all incision cites | Ropivacaine | ultrasonographic | General anesthesia | . Intravenous PCA fentanyl, oral 200 mg of celecoxib | pain score |

| Okoroha et al. 2016 [30] | 41/41 | 25/24 | 27.6/27.0 | 20 mL of liposomal bupivacaine (266 mg) was mixed with 10 mL of saline solution | Intra-articular infiltration | 40 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine | ultrasound guided | General anesthesia | hydromorphone,hydrochloride,hydrocodonee,acetaminophen | pain score |

| Sahni et al. 2015 [22] | 20/20 | 16/17 | 29.3/27.1 | Bupivacaine 0.25% 30 ml with clonidine 1 μg/kg | Intra-articular infiltration | Bupivacaine 0.25% 20 ml with clonidine 0.5 μg/kg | Ultrasound combined with nerve stimulation | Spinal anesthesia | Intravenous diclofenac, i.v. fentanyl | Duration of analgesia |

| Woods et al. 2006 [33] | 45/45 | 25/17 | 31.1/33.3 | Bupivacaine 0.5% 20 ml with adrenaline 5 μg/ml and morphine 10 mg | Intra-articular infiltration | Ropivacaine 0.5% 30–40 ml with clonidine 100 μg followed by a continuous infusion of ropivacaine 0.2% with a rate of 4 ml/h | Nerve stimulation | General anesthesia | Acetaminophen, oral oxycodone, hydromorphone | Pain score |

FNB femoral nerve block, LIA Local infiltration analgesia

Fig. 2.

Risk bias of the included trials

Fig. 3.

Summary of bias risk of the included trials

Results of the meta-analysis

Postoperative pain

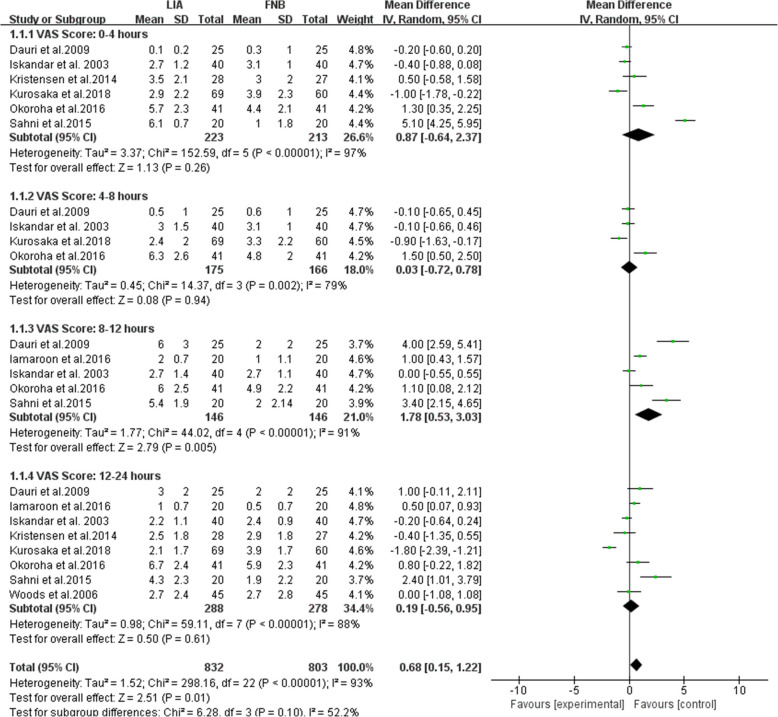

A subgroup analysis was performed for comparing VAS score after surgery of ACL reconstruction with LIA and FNB at 0 to 4 h, 4 to 8 h, 8 to 12 h, and 12 to 24 h. Five researches on 292 patients mentioned the VAS score at 8 to 12 postoperative hours [21, 22, 27, 30, 32], with the FNB group showing a lower score than the LIA group, (MD = 1.78; 95% CI, [0.53, 3.03]; P = 0.005; I2 = 91%). Six studies on 436 patients were assessed VAS score at 0 to 4 h [17, 22, 27, 30–32], there was no significant difference between the LIA and FNB groups (MD = 0.87; 95% CI, [− 0.64, 2.37]; P = 0.26; I2 = 97%). Similar findings were observed at 4 to 8 [27, 30–32] and 12 to 24 [17, 21, 22, 27, 30–33]postoperative hours separately (MD = 0.03; 95% CI, [− 0.72, 0.78]; P = 0.94; I2 = 79%) (MD = 0.19; 95% CI, [− 0.56, 0.95]; P = 0.61; I2 = 88%). All the VAS score results are shown in Fig. 4. Heterogeneity of the all study was evident, so we tried to trace the source of the variance.

Fig. 4.

Pain scores at rest in 0 to 4 h, 4 to 8 h, 8 to 12 h, and 12 to 24 h postoperative period. FNB, femoral nerve block; LIA, local infiltration analgesia; IV, inverse variance

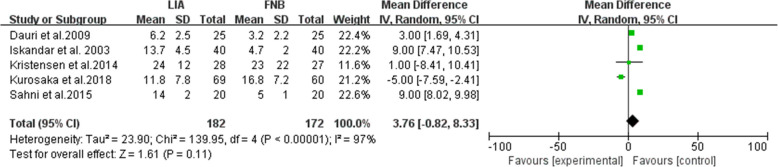

Morphine consumption

Five studies on 354 patients reported the intravenous (i.v.).morphine equivalent consumption within the first 24-h postoperative period [17, 22, 27, 31, 32], pooled data revealed that there was no significant difference between the LIA and FNB groups (MD = 3.76; 95% CI, [− 0.82, 8.33]; P = 0.11; I2 = 97%; Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Intravenous (i.v.) morphine equivalent consumption, within 24 h postoperative period, mg

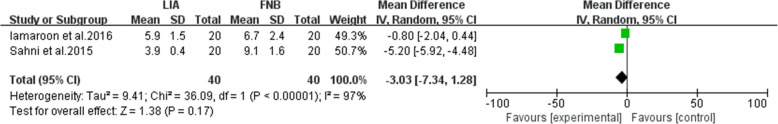

Analgesic duration

Two studies on 80 patients reported the duration of analgesia [21, 22], which showed that there was no significant difference between the LIA and FNB groups (MD = − 3.03; 95% CI, [− 7.34, 1.28]; P = 0.17; I2 = 97%; Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Duration of analgesia; hour

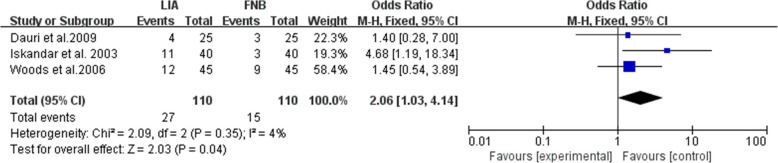

Complications

The major postoperative complications mentioned in the literature included in our study were nausea, vomiting, fatigue, dizziness, pruritus and sedation. Three studies reported the number of cases of nausea within the first 24-h postoperative period [27, 32, 33], with the incidence of nausea in the LIA group was higher than that in the FNB group (OR = 2.06; 95% CI, [1.03, 4.14]; P = 0.04; I2 = 4%; Fig. 7). Because of the limited number of studies reporting other complications, a meaningful statistical analysis was not possible. Other complications showed no significant difference within 24 h after surgery, as shown in Table 2.

Fig. 7.

Nausea (complications) within 24 h postoperative period

Table 2.

Complications within 24 h postoperative period

| Side Effect Reported | Studies | Group | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIA | FNB | |||||||

| Events | Total | Events | Total | |||||

| Nausea | Iskandar et al. 2003 [27] | 11 | 40 | 11 (27.5) | 3 | 40 | 3 (7.5) | 0.037 |

| Woods et al.2006 [33] | 12 | 45 | 11 (24.4) | 9 | 45 | 9 (20.0) | 0.400 | |

| Dauri et al.2009 [32] | 4 | 25 | 4 (16.0) | 3 | 25 | 3 (12) | 0.68 | |

| Vomiting | Iskandar et al. 2003 [27] | 5 | 40 | 5 (12.5) | 2 | 40 | 2 (5) | 0.43 |

| Nausea or vomiting | Kurosaka et al.2018 [31] | 7 | 69 | 7 (10) | 7 | 60 | 7 (17) | 0.78 |

| Sedation | Iskandar et al. 2003 [27] | 8 | 40 | 8 (20.0) | 1 | 40 | 1 (2.5) | 0.03 |

| Pruritus | Kurosaka et al.2017 [31] | 2 | 69 | 2 (2.9) | 3 | 60 | 3 (5) | 0.54 |

FNB femoral nerve block, LIA Local infiltration analgesia

Discussion

Pain management efficacy

In this meta-analysis of Level 1 RCTs comparing LIA and FNB after ACLR, the FNB group demonstrated a significantly lower pain score than the LIA group 8—12 h post-surgery [21, 22, 27, 30, 32]. However, there was no significant difference in pain scores between the two groups at 0–4 [17, 22, 27, 30–32], 4–8 [27, 30–32], and 12–24 [17, 21, 22, 27, 30–33] hours post—operation. These results deviated from the initial hypothesis that LIA’s efficacy in managing early postoperative pain was no less than that of FNB. The main finding of our review is not consistent with the findings of Iskandar et al. [27], might be attributed to various factors. Differences in patient characteristics across studies may also contribute to the discrepancies. For example, age can influence pain perception and recovery ability. Elderly patients may have a lower pain tolerance and slower recovery [34], which could affect the analgesic effects of LIA and FNB differently. Additionally, patients’ pre-operative sports levels might play a role. Athletes with higher—intensity exercise habits may have different postoperative pain experiences and requirements for analgesia compared to sedentary individuals [35]. Moreover, surgical techniques, such as the type of graft used in ACLR (hamstring tendon, patellar tendon, etc.) and the fixation method, can vary among studies. These differences in surgical procedures may lead to different degrees of tissue damage and inflammation, thus interfering with the assessment of the analgesic effects of the two methods [36].

Morphine consumption and analgesic duration

Within the first 24—hour postoperative period, the pooled data from five studies involving 354 patients showed no significant difference in intravenous morphine equivalent consumption between the LIA and FNB groups [17, 22, 27, 31, 32]. Additionally, data from two studies on 80 patients indicated no significant difference in analgesic duration. This suggests that, in terms of morphine consumption and analgesic duration, neither LIA nor FNB has a clear advantage within the first 24 h after ACLR [21, 22].

Postoperative complications

Regarding postoperative complications of ACLR, the analysis of three studies revealed that the incidence of nausea within the first 24—hour postoperative period was higher in the LIA group than in the FNB group [27, 32, 33]. However, due to the limited number of studies reporting other complications such as vomiting, fatigue, dizziness, pruritus, and sedation, a meaningful statistical analysis for these complications was not possible. Overall, apart from nausea, there was no significant difference in other complications between the two groups within 24 h after surgery. Different types of anesthesia, such as general anesthesia and spinal anesthesia, may influence the incidence of PONV. General anesthesia acts on the central nervous system, which might have a different impact on the chemoreceptor trigger zone compared to spinal anesthesia. Additionally, sedation protocols can also play a role. Some sedatives may increase the risk of PONV, while others may have a mitigating effect.

Heterogeneity and limitations

Although the study focuses only on clinical trials I, there are still several limitations that could have an impact on the results. The high I2 values in many analyses indicated significant heterogeneity among the included studies. This heterogeneity stemmed from differences in intervention measures, such as the dosage, timing, type of local anesthetics and the injection composition used in LIA and FNB. These differences can result in different drug effects, affecting postoperative pain control and recovery, and interfering with the accurate assessment of the effects of the two analgesic methods.

The type of anesthesia varied across the included studies. Some studies used general anesthesia, some used spinal anesthesia, and one study used peripheral nerve blocks as the anesthetic technique. This diversity in anesthesia types can potentially influence the results in multiple ways. Different anesthesia methods have distinct mechanisms of action, which may affect pain perception and control post-operation [37]. For example, general anesthesia acts on the central nervous system, spinal anesthesia blocks nerve conduction at the spinal level, and peripheral nerve blocks target specific nerves. These differences can interfere with the accurate assessment of the analgesic effects of LIA and FNB. Moreover, different anesthesia methods can cause varying physiological responses in patients, such as different impacts on the cardiovascular and respiratory systems [38]. These responses may indirectly affect the postoperative recovery process and the occurrence of complications, thus confounding the interpretation of the results related to LIA and FNB.

Furthermore, the local anesthetic solutions vary significantly, not only between different studies but also among groups within the same study. For instance, different concentrations of local anesthetics like ropivacaine (0.2% vs 0.5%) and bupivacaine (0.25% vs 0.5%) were used across studies. Additionally, within the same study, some groups had adjuvant drugs such as clonidine or adrenaline added to the local anesthetic solution, while others did not [17, 32]. These discrepancies have a crucial impact on the interpretation of the results. Different concentrations of local anesthetics have different effects on nerve conduction blockade, with higher concentrations potentially providing stronger and more prolonged blockade but also increasing the risk of adverse reactions [39]. The addition of adjuvant drugs alters the overall pharmacological properties of the local anesthetic solution. Clonidine can enhance analgesic effects and prolong the duration of action, and adrenaline can constrict blood vessels and slow down the absorption rate of local anesthetics, which may interfere with the assessment of the analgesic effects of LIA and FNB [33]. Therefore, in future research aiming to compare the analgesic effects of LIA and FNB more precisely, it would be advisable to standardize the anesthesia method as much as possible. Alternatively, when designing the study and analyzing the data, the impact of anesthesia method differences should be fully considered. Meanwhile, the impact of these differences should be fully considered during data analysis to accurately interpret the research results.

Another important aspect that requires attention is the difference in postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) between the LIA and FNB groups. Although there was no significant difference in opioid consumption between the two groups, the incidence of nausea in the LIA group was higher than that in the FNB group. It is crucial to note that in one study, the LIA group had morphine in their solution [31]. Morphine, as an opioid, is a well—known trigger for PONV. It can stimulate the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the body, leading to an increased likelihood of nausea and vomiting. This factor may have confounded the assessment of the true risk of PONV associated with LIA and FNB. It might have overestimated the risk of PONV in the LIA group and potentially masked some of the factors in the FNB group that could contribute to PONV. In future research, it is necessary to standardize the composition of local anesthetic solutions to avoid the addition of drugs that are likely to cause PONV, such as morphine, unless it is the specific variable being studied. If the impact of a particular drug like morphine is under investigation, it should be clearly labeled, and a more in—depth analysis of its influence on PONV should be conducted. When analyzing the factors contributing to PONV, other variables such as the type of anesthesia, duration of surgery, and patient—specific factors should be controlled to rule out confounding effects. This will enable a more accurate assessment of the relationship between LIA, FNB, and PONV, providing a more reliable basis for clinicians to select appropriate analgesic regimens in the future.

On the other hand, our study was unable to evaluate the effects of different analgesic techniques on postoperative functional recovery. The outcome of the included studies rarely involved reports of active recovery. In addition, more and more clinical researches have adopted an intra-articular LIA technique in ACLR. Still a previous study in vitro showed that both bupivacaine and ropivacaine used for intra-articular LIA have chondrotoxic properties [40], leading to that cartilage is almost wholly lost within 12 months after knee arthroscopy [41]. Therefore, it is unclear whether this method might provide equivalent analgesic effects for the FNB without the risk of cartilage dissolution in the knee joint [42]. Many studies are still needed to verify the effectiveness of LIA for postoperative analgesia after ACLR.

The outcome evaluation indicators and methods were diverse. Different patient self—reported pain scores (VAS, digital score scale) [30] or measurement scales (VAS, 0—10, VAS, 0—100 mm) were used in terms of outcome evaluation [31, 32], and different opioids are used as emergency analgesics and converted to intravenous morphine consumption injections [21]. All these may lead to inconsistencies in the results and affect the accuracy and comparability of the data.

Moreover, gray literature and non—English studies were excluded from the search strategy, which might have affected the comprehensiveness of the results. Another point that needs attention, in this study, after careful evaluation, the number of included literatures is limited. Conducting subgroup analyses according to some factors (e.g., by age, gender, or surgical technique, …) would result in too few literatures in each subgroup to draw reliable conclusions. Therefore, we will not perform these subgroup analyses in this study.

Although the Cochrane risk-bias tool showed a low risk of bias for all included trials, publication bias was a potential concern as it was not assessed due to the relatively small number of included studies, it could exist. Studies with positive results are more likely to be published, which may lead to an over—representation of certain findings. If studies that show no difference or less favorable results for a particular analgesic method are not published, it can distort the overall picture of the efficacy of LIA and FNB.

It is also important to acknowledge that our meta—analysis included only 8 RCTs and showed a scarcity of extensive sample RCT studies. So we used a random-effects model to incorporate the heterogeneity among researches [43]. As suggested, a more robust result in meta—analysis is typically obtained when there are at least 10 RCTs with adequate sample size. The relatively small number of included studies in our research leads to certain limitations. With a smaller sample size, the statistical power of the study is insufficient, which may prevent the accurate detection of subtle but clinically significant differences between LIA and FNB. For example, when analyzing postoperative pain scores, morphine consumption, and other indicators, the smaller sample size makes the results more susceptible to the influence of individual differences and minor differences in study designs, reducing the reliability of the conclusions. However, it should be noted that all the studies included in our review are level 1 RCTs, which have relatively high—quality evidence. In the current situation where there is a lack of more eligible studies, the results of our study can still provide some reference for clinical practice. In future research, efforts should be made to expand the sample size and include more high—quality RCTs. Researchers can broaden the search scope, not only relying on the current databases but also exploring other relevant professional databases and gray literature to comprehensively collect studies. Additionally, it is encouraged to conduct more large—sample RCTs to further clarify the differences in the effects of LIA and FNB in postoperative pain management, providing a more solid basis for clinicians to select better analgesic regimens.

Contribution to literature and clinical practice

Regarding the concern that femoral blocks are generally considered to provide better analgesia than local infiltration in the first few postoperative hours, this meta—analysis still contributes significantly to the medical literature. Previous studies on this topic had limitations such as small sample sizes, varying study qualities, and high data heterogeneity, which made the conclusions less definitive [23]. Our study adhered strictly to the PICOS criteria and included 8 level 1 randomized controlled trials, which are of relatively high quality. By conducting a meta—analysis of these high—quality evidences, we were able to evaluate the differences between the two analgesic methods more accurately and reliably, providing more persuasive evidence for clinical practice. Moreover, our study did not merely focus on postoperative pain scores. We comprehensively analyzed multiple indicators, including morphine consumption, analgesic duration, and the incidence of complications within the first 24 h after surgery.

In clinical practice, based on our findings, when choosing an analgesic method for ACLR patients, clinicians should consider the different needs of patients at various postoperative time points. For the first 8—12 h after surgery, FNB is a better choice for pain control. However, considering the overall 24—hour period, factors such as the incidence of nausea and individual patient differences should also be taken into account. If a patient is more sensitive to nausea, FNB may be more suitable, while for patients with other special conditions, a more personalized analgesic plan needs to be developed. This multi—dimensional analysis allows clinicians to have a more comprehensive understanding of the efficacy and safety of the two analgesic methods, facilitating the development of more rational analgesic regimens. Although the results of this study may provide some basis for formulating analgesic regimens for post—ACLR patients, whether it can truly facilitate early discharge, quicker recovery of related functions, and earlier return to sports activities still needs further verification.

Future research directions

With the development of medicine, continuous updates and optimizations in clinical practice are required. Our study serves as a foundation for subsequent research. Future research could focus on comparing alternative techniques such as adductor canal block, femoral cutaneous nerves block, and IPACK block with LIA and FNB. These studies should comprehensively assess analgesic efficacy, side—effect profiles, and impact on postoperative functional recovery. Additionally, it is essential to standardize intervention measures, outcome assessment indicators, and methods. Multi—center and large—sample study designs are needed to further verify the research results, fully consider and control potential confounding factors, For example, individual differences among patients, including age, gender, basic health status, pain tolerance, etc., as well as differences in surgical operations (such as operation duration, surgical complexity, etc.), and improve the reliability of the research and its clinical application value. Given that the current study was unable to evaluate the effects of different analgesic techniques on postoperative functional recovery, more studies are required to verify the effectiveness of LIA for postoperative analgesia after ACLR. This will promote the conduct of more in—depth and standardized studies, thus driving the development of this field in medicine.

Conclusion

In conclusion, FNB provides superior analgesia compared to LIA within the first 8–12 h postoperatively. Additionally, the incidence of nausea within 24 h after surgery is lower in the FNB group. For patients with a high risk of nausea and vomiting, such as those with a history of motion sickness or previous adverse reactions to opioids, FNB may be a more suitable option considering its lower incidence of nausea within 24 h after surgery. On the other hand, for patients who require earlier mobilization and have concerns about muscle weakness associated with FNB, LIA could be considered, while closely monitoring for potential nausea and other complications. Clinicians can enhance patients’ postoperative comfort, minimize nausea—related complications, and facilitate recovery by selecting the appropriate analgesic method based on these findings. It also enables healthcare providers to make more informed decisions for optimizing pain management in ACLR patients.

Regarding pain control from 0—24 h post—surgery, morphine consumption, and analgesic duration, LIA does not outperform FNB. However, it must be emphasized that the results of this study should be interpreted with great caution. As mentioned in the limitations, the high heterogeneity among the included studies, which was caused by differences in intervention measures, anesthesia types, and local anesthetic solutions, has the potential to influence the outcomes. Thus, when making clinical decisions, healthcare providers should take into account the unique characteristics of each patient, including age, pain tolerance, and underlying health conditions, as well as the specific surgical details. Thus, for ACLR patients, FNB is recommended as an effective analgesic approach.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

WJ M and DM Z contributed the same to the article, conceptualization (lead) and in writing, reviewing, and editing the manuscript, software (lead); formal analysis (lead); PC L writing the original draft (lead) and writing, reviewing, and editing the manuscript (equal);L L, MP Y and J Z contributed to acquisition of data; WJ M and DM Z and PC L, contributed to analysis and interpretation of data; J L, and PC L contributed to revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the fnal version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific research project of Sichuan Provincial Health Commission [grant numbers 19PJ087].

Data availability

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wenjuan Ma and Dongmei Zhao are co-first authors.

References

- 1.Donelon TA, Edwards J, Brown M, Jones PA, O Driscoll J, Dos Santos T. Differences in biomechanical determinants of ACL injury risk in change of direction tasks between males and females: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med Open 2024;10(1). 10.1186/s40798-024-00701-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Chen J, Wang X. The efficacy and safety of local infiltration analgesia vs femoral nerve block after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a retrospective trial protocol. Medicine. 2021;100(3):e23895. 10.1097/MD.0000000000023895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walczak BE, Bernardoni ED, Steiner Q, Baer GS, Donnelly MJ, Shepler JA. Effects of general anesthesia plus multimodal analgesia on immediate perioperative outcomes of hamstring tendon autograft ACL reconstruction. Jbjs Open Access. 2023;8(1). 10.2106/JBJS.OA.22.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Williams BA, Kentor ML, Vogt MT, Vogt WB, Coley KC, Williams JP, et al. Economics of nerve block pain management after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: potential hospital cost savings via associated postanesthesia care unit bypass and same-day discharge. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(3):697–706. 10.1097/00000542-200403000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall-Burton DM, Hudson ME, Grudziak JS, Cunningham S, Boretsky K, Boretsky KR. Regional anesthesia is cost-effective in preventing unanticipated hospital admission in pediatric patients having anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Region Anesth Pain M. 2016;41(4):527–31. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leathers MP, Merz A, Wong J, Scott T, Wang JC, Hame SL. Trends and demographics in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the United States. J Knee Surg. 2015;28(5):390–4. 10.1055/s-0035-1544193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guirro UB, Tambara EM, Munhoz FR. Femoral nerve block: assessment of postoperative analgesia in arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2013;63(6):483–91. 10.1016/j.bjane.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards MD, Bethea JP, Hunnicutt JL, Slone HS, Woolf SK. Effect of adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block on quadriceps strength, function, and postoperative pain after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review of level 1 studies. Am J Sport Med. 2020;48(9):2305–13. 10.1177/0363546519883589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grevstad U, Mathiesen O, Valentiner LS, Jaeger P, Hilsted KL, Dahl JB. Effect of adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block on quadriceps strength, mobilization, and pain after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, blinded study. Region Anesth Pain M. 2015;40(1):3–10. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Runner RP, Boden SA, Godfrey WS, Premkumar A, Samady H, Gottschalk MB, et al. Quadriceps strength deficits after a femoral nerve block versus adductor canal block for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, single-blinded, randomized trial. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(9). 10.1177/2325967118797990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Dixit A, Prakash R, Yadav AS, Dwivedi S. Comparative study of adductor canal block and femoral nerve block for postoperative analgesia after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament tear repair surgeries. Cureus J Med Science. 2022;14(4):e24007. 10.7759/cureus.24007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krych A, Arutyunyan G, Kuzma S, Levy B, Dahm D, Stuart M. Adverse effect of femoral nerve blockade on quadriceps strength and function after ACL reconstruction. J Knee Surg. 2015;28(1):83–8. 10.1055/s-0034-1371769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo TD, Ashraf A, Dahm DL, Stuart MJ, McIntosh AL. Femoral nerve block is associated with persistent strength deficits at 6 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in pediatric and adolescent patients. Am J Sport Med. 2015;43(2):331–6. 10.1177/0363546514559823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stebler K, Martin R, Kirkham KR, Lambert J, De Sede A, Albrecht E. Adductor canal block versus local infiltration analgesia for postoperative pain after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a single centre randomised controlled triple-blinded trial. Brit J Anaesth. 2019;123(2):e343–9. 10.1016/j.bja.2019.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yung EM, Brull R, Albrecht E, Joshi GP, Abdallah FW. Evidence basis for regional anesthesia in ambulatory anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: part III: local instillation analgesia-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(3):426–37. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lefevre N, Klouche S, de Pamphilis O, Herman S, Gerometta A, Bohu Y. Peri-articular local infiltration analgesia versus femoral nerve block for postoperative pain control following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: prospective, comparative, non-inferiority study. Orthop Traumatol Sur. 2016;102(7):873–7. 10.1016/j.otsr.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristensen PK, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, Storm JO, Thillemann TM. Local infiltration analgesia is comparable to femoral nerve block after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring tendon graft: a randomised controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(2):317–23. 10.1007/s00167-013-2399-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baverel L, Cucurulo T, Lutz C, Colombet, Cournapeau J, Dalmay F, et al. Anesthesia and analgesia methods for outpatient anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop Traumatol Sur 2016;102(8S):S251–5. 10.1016/j.otsr.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Bailey L, Griffin J, Elliott M, Wu J, Papavasiliou T, Harner C, et al. Adductor canal nerve versus femoral nerve blockade for pain control and quadriceps function following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon autograft: a prospective randomized trial. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(3):921–9. 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.10.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch JR, Okoroha KR, Lizzio V, Yu CC, Jildeh TR, Moutzouros V. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for pain control after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective randomized trial. Am J Sport Med. 2019;47(2):355–63. 10.1177/0363546518815874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iamaroon A, Tamrongchote S, Sirivanasandha B, Halilamien P, Lertwanich P, Surachetpong S, et al. Femoral nerve block versus intra-articular infiltration: a preliminary study of analgesic effects and quadriceps strength in patients undergoing arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Med Assoc Thai. 2016;99(5):578–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahni N, Panda N, Jain K, Batra Y, Dhillon M, Jagannath P. Comparison of different routes of administration of clonidine for analgesia following anterior cruciate ligament repair. J Anaesth Clin Pharm. 2015;31(4):491–5. 10.4103/0970-9185.169070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirkham KR, Grape S, Martin R, Albrecht E. Analgesic efficacy of local infiltration analgesia vs. femoral nerve block after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesia. 2017;72(12):1542–53. 10.1111/anae.14032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Plos Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grape S, Kirkham KR, Baeriswyl M, Albrecht E. The analgesic efficacy of sciatic nerve block in addition to femoral nerve block in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesia. 2016;71(10):1198–209. 10.1111/anae.13568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon DB, Stevenson KK, Griffie J, Muchka S, Rapp C, Ford-Roberts K. Opioid equianalgesic calculations. J Palliat Med. 1999;2(2):209–18. 10.1089/jpm.1999.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iskandar H. Femoral block provides superior analgesia compared with intra-articular ropivacaine after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Region Anesth Pain M. 2003;28(1):29–32. 10.1053/rapm.2003.50019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X, Zhou J, Mao G, Yu Q, Wu X, Sun H, et al. Effects of adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block in patients with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Medicine. 2019;98(36):e16763. 10.1097/MD.0000000000016763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okoroha KR, Keller RA, Marshall NE, Jung EK, Mehran N, Owashi E, et al. Liposomal bupivacaine versus femoral nerve block for pain control after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective randomized trial. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(9):1838–45. 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurosaka K, Tsukada S, Nakayama H, Iseki T, Kanto R, Sugama R, et al. Periarticular injection versus femoral nerve block for pain relief after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(1):182–8. 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.08.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dauri M, Fabbi E, Mariani P, Faria S, Carpenedo R, Sidiropoulou T, et al. Continuous femoral nerve block provides superior analgesia compared with continuous intra-articular and wound infusion after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Region Anesth Pain M. 2009;34(2):95–9. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31819baf98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woods GW, O’Connor DP, Calder CT. Continuous femoral nerve block versus intra-articular injection for pain control after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(8):1328–33. 10.1177/0363546505286145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.AlMakadma Y, Simpson K. Opioid therapy in non-cancer chronic pain patients: trends and efficacy in different types of pain, patients age and gender. Saudi J Anaesth. 2013;7(3):291. 10.4103/1658-354X.115362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thornton C, Baird A, Sheffield D. Athletes and experimental pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2024;25(6):104450. 10.1016/j.jpain.2023.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao L, Lu M, Deng M, Xing J, He L, Wang C. Outcome of bone–patellar tendon–bone vs hamstring tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Medicine. 2020;99(48):e23476. 10.1097/MD.0000000000023476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hemmings HC, Riegelhaupt PM, Kelz MB, Solt K, Eckenhoff RG, Orser BA, et al. Towards a comprehensive understanding of anesthetic mechanisms of action: a decade of discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019;40(7):464–81. 10.1016/j.tips.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fu G, Xu L, Chen H, Lin J. State-of-the-art anesthesia practices: a comprehensive review on optimizing patient safety and recovery. BMC Surg 2025;25(1). 10.1186/s12893-025-02763-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Yu Y, Cui L, Qian L, Lei M, Bao Q, Zeng Q, et al. Efficacy of perioperative intercostal analgesia via a multimodal analgesic regimen for chronic post-thoracotomy pain during postoperative follow-up: a big-data, intelligence platform-based analysis. J Pain Res. 2021;14:2021–8. 10.2147/JPR.S303610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piper SL, Kim HT. Comparison of ropivacaine and bupivacaine toxicity in human articular chondrocytes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(5):986–91. 10.2106/JBJS.G.01033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noyes FR, Fleckenstein CM, Barber-Westin SD. The development of postoperative knee chondrolysis after intra-articular pain pump infusion of an anesthetic medication: a series of twenty-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(16):1448–57. 10.2106/JBJS.K.01333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koh IJ, Chang CB, Seo ES, Kim SJ, Seong SC, Kim TK. Pain management by periarticular multimodal drug injection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized, controlled study. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(5):649–57. 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xin S, Heels-Ansdell D, Walter SD, Guyatt G, Swiontkowski M. Is a subgroup claim believable? A user’s guide to subgroup analyses in the surgical literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(3):e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article.