ABSTRACT

The pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of remimazolam, a ultra‐short‐acting benzodiazepine, has been investigated for procedural sedation and anesthesia, but its pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and optimal dosing for ICU sedation are still unclear. This prospective, single‐center, double‐blind randomized controlled trial studied ICU adults on mechanical ventilation for over 24 h. Participants were divided into three groups, each receiving a 0.2 mg/kg remimazolam loading dose in less than a minute, followed by maintenance doses of 0.1, 0.3, or 0.5 mg/kg/h. Plasma concentrations of remimazolam and its metabolites were measured using UPLC‐MS/MS, and pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using one‐compartmental methods with WinNolin. The study also assessed pharmacodynamic indicators (RASS score) and the impact of the clinical indicators on pharmacokinetic parameters. The study on 36 ICU patents using a one‐compartment model found that after 24 h of continuous intravenous remimazolam infusion, the drug had a median clearance rate of 22.23 mL/kg/min and a volume of distribution of 2656.58 mL/kg. The half‐life was 101.791 min in ventilated patients, while its metabolites had a slower clearance rate of 0.49 mL/kg/min and an longer half‐life of 656.02 min. Sedation levels were mild to moderate at dosed of 0.1–0.3 mg/kg/h. Liver function significantly affected remimazolam metabolism, influencing the half‐life (R 2 = 0.36, p = 0.00013) and clearance (R 2 = 0.13, p = 0.04). The pharmacokinetic study indicates that remimazolam is effective and safe for ICU patients on mechanical ventilation, with a 24‐h infusion demonstrating rapid clarence and a clear dose‐effect relationship. It provides mild to moderate sedation at 0.1–0.3 mg/kg/h, but caution is advised for patients with severe liver dysfunction due to its impact on drug metabolism.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05480787

Keywords: intensive care, mechanical ventilation, pharmacokinetics, remimazolam, sedation

1. Introduction

Sedation is an indispensable component of treatment for critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation to improve care and outcomes, but the best sedative remains controversial. Midazolam, a benzodiazepine, is not recommended by PADIS guidelines due to its prolonged effects, complex interactions, and high delirium risk [1]. Its long‐acting metabolites also cause accumulation [2]. The hypnotics propofol [GABA(A) receptor agonist] and dexmedetomidine (elective α2‐adrenergic agonist) are dependent on liver and kidney metabolism, posing a burden on the liver and kidney and increasing the risk of adverse reactions such as respiratory and cardiovascular suppression. In addition, dexmedetomidine does not reliably achieve all depths of sedation. Despite various options, the ideal sedative for ventilated adults remains unestablished.

Remimazolam is an ultra‐short‐acting benzodiazepine with a rapid and predictable onset and offset profile, no accumulation and extended effect, and no dependence on organ elimination for short‐term sedation such as procedural sedation. Therefore, remimazolam has garnered growing attention as a potential drug for ICU sedation [3, 4]. Remimazolam was designed as a “soft drug”, which may be attributed to the additional carboxylic ester linkage, contributing to its favorable properties for sedation compared to midazolam [5]. Nonetheless, although the efficacy and safety of remimazolam have been determined in the context of sedation for endoscopic procedures and general anesthesia, its suitable use in ICU sedation, especially when sedation should be longer than 24 h and dosing regimens for varying levels of RASS scores remains unknown [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. The pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and the appropriate dosage of remimazolam infusion in ICU sedation require further study. Therefore, this study conducted a preliminary assessment of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of remimazolam in ICU patients with mechanical ventilation for a 24‐h continuous intravenous infusion.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective, single‐center, double‐blind randomized controlled clinical trial included adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation in 24 h infusion of remimazolam tosylate from July 2022 to December 2022. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, and informed consent was obtained from patients for specimen collection.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of Patients

All adult patients aged 18 years and above who were expected to be mechanically ventilated for longer than 24 h were eligible for screening. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) known or suspected allergy to target drugs or allergy to related drugs applied in the trial; (2) pregnancy or lactation period; (3) acute or chronic severe neurological disorder and any other disease interfering with the Richmond Agitation‐Sedation Scale (RASS) assessment; (4) long‐term use of anti‐anxiety drugs or hypnotics such as benzodiazepines or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs); (5) acute or chronic renal insufficiency requiring dialysis; and (6) severe ARDS or other disease that requires continuous deep sedation and/or paralysis.

2.3. Randomization and Interventions

All patients who met the inclusion criteria were divided into three groups by a computer‐generated random number method, and each group was administered a different dosage of remimazolam tosylate. The study drugs were given for a 24 h period. Patients and nurses involved in patient care were blinded to the randomization and interventions.

The Critical‐Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) score was used for analgesic medical dosing, and a score of 0 was achieved by the infusion of analgesic medication (remifentanil, 0.5–15 μg/kg/h). A loading dose of 0.2 mg/kg of remimazolam was rapidly administered over 1 min. The subsequent maintenance doses of remimazolam were 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 mg/kg/h, respectively. Two investigators independently assessed the RASS score, and the average score was recorded. Deep sedation was defined as a RASS score of −5 to −4, moderate sedation as a score of −3, and mild sedation as −2 to 0. A rescue dose of dexmedetomidine (0.2–0.7 μg/kg/h) was administered if patients were agitated.

Hemodynamic parameters, including mean blood pressure (MAP), heart rate, and pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2), were monitored using invasive arterial pressure during remimazolam administration. Tachycardia was defined as a heart rate exceeding 100 beats per minute (bpm), bradycardia as below 50 bpm, hypoxemia as the SpO2 under 90%, and hypotension as systolic blood pressure (SBP) below 90 mmHg or a decrease of more than 20% from baseline [11]. In the absence of hypotension, concurrently monitor the blood pressure trend during pharmacological intervention. Persistent hypotension was treated with norepinephrine.

2.4. Drug Concentration Determination Method

All venous blood samples (3 mL) were collected into EDTA tubes at 5, 20, and 24 h following the initiation of the remimazolam infusion and 10, 30, 50, 90, 140, and 240 min post‐infusion. Within 30 min of collection, the blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and then stored at −80°C for further analysis. In this study, the concentration of remimazolam and its metabolites in human plasma samples was detected by an established ultra‐high performance liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (UPLC‐MS/MS) method [12]. Remimazolam tosylate and its metabolites were supplied by Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine Co. Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). All parameters met the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) standards and the China National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) guidelines for the validation of bioanalytical methods.

2.5. Pharmacokinetic Analysis

All data from the pharmacokinetic experiments were analyzed with WinNolin 8.3. In addition, a single‐compartment model was established using the plasma concentration‐time data of remimazolam and its metabolite of the 0.5 mg/kg/h group. The metabolic process of remimazolam was determined to fit a single‐compartment model based on the shape of the plasma concentration‐time semi‐logarithmic curve and the Akaike information criterion (AIC) value. Subsequently, a linear model with one compartment was used to establish the pharmacokinetic models. The specific code for the single‐compartment model was calculated using the following equation: deriv (A 1 = −K m*A 1), deriv (A 2 = K m*A 1 − K e*A 2), C = A 1/V, where A 1 is the amount of remimazolam administered, A 2 is the amount of remimazolam metabolite, C is the concentration of remimazolam, K m is the rate of conversion of remimazolam to its metabolite, and K e is the rate of elimination of remimazolam metabolite. The established pharmacokinetics model was validated using data from the 0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg/h dosing groups to assess the predictive capability and generalizability. The area under the concentration‐time curve from time zero to the last measurable time point (AUC0–t ) was calculated using the linear/log trapezoidal method. The area under the concentration‐time curve from time zero to infinity (AUC0–∞) was calculated using the formula AUC0–∞ = AUC0–t + C t /λz, where C t represents the final detectable concentration and λz represents the elimination rate constant. The elimination rate constant (λz) was estimated using linear least‐squares regression analysis applied to the concentration‐time data obtained during the terminal log‐linear phase.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons of the groups were conducted using R4.2.0. The chi‐squared test or Fisher's exact test was used to analyze differences between groups in the descriptive analysis of the categorical data, which was expressed as the number of instances and percentages (n, %). Continuously measured data following normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD, and the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test was performed to compare groups; otherwise, they were expressed as median (interquartile ranges, IQRs) and compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Statistically significant correlations were defined as those with p values < 0.05. Furthermore, the relationship between baseline data and pharmacokinetic parameters was analyzed by Pearson correlation analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

A total of 36 participants were included and completed the study. Among them, 11 individuals were administered remimazolam at a dosage of 0.5 mg/kg/h, 13 received 0.3 mg/kg/h, and 12 received 0.1 mg/kg/h as sedation maintenance. However, one patient diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B exhibited an extremely prolonged half‐life (524.31 min) and a relatively high concentration at 5 h after infusion (1969.62 ng/mL). The patient was excluded during the model establishment. The remaining 35 participants had a mean age of 60.8 with a standard deviation of 14.0 years (Table 1). Among these participants, 28 (80.00%) were male. The average BMI of the participants was 23.63 kg/m2, with a standard deviation of 3.19 kg/m2. The baseline demographics among the three treatment groups showed no significant differences except for two variables: sex (p = 0.045) and albumin (ALB) (p = 0.026).

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics.

| Variable | Total | 0.1 mg/kg/h | 0.3 mg/kg/h | 0.5 mg/kg/h | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 35) | (n = 12) | (n = 13) | (n = 10) | ||

| Male, n (%) | 28 (80.0%) | 7 (58.3%) | 11 (84.6%) | 10 (100.0%) | 0.045 |

| Age (year) | 60.80 14.25 | 58.92 18.41 | 64.54 12.80 | 58.20 10.10 | 0.501 |

| Hight (cm) | 170.00 [168.00, 173.00] | 171.50 [168.50, 175.00] | 170.00 [166.00, 172.00] | 170.00 [168.25, 171.00] | 0.813 |

| Weight (kg) | 67.94 9.99 | 65.42 9.35 | 68.31 10.59 | 70.50 10.24 | 0.501 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.63 3.19 | 22.70 3.09 | 23.87 3.34 | 24.43 3.15 | 0.432 |

| APACHE II score | 14.97 5.31 | 14.58 5.63 | 16.46 4.46 | 13.50 5.95 | 0.407 |

| SOFA score | 6.29 3.08 | 6.17 3.01 | 5.69 3.54 | 7.20 2.57 | 0.516 |

| Child–Pugh score | 6.00 [5.00, 7.00] | 6.00 [5.00, 7.00] | 7.00 [5.75, 8.00] | 5.00 [5.00, 6.00] | 0.009 |

| Drinking | 12 (34.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 5 (38.5%) | 5 (50.0%) | 0.241 |

| Reasons for ICU admission | |||||

| Medical | 6 (17.2%) | 3 (25.0%) | 2 (15.3%) | 1 (10.0%) | 0.088 |

| Surgical | 23 (65.7%) | 8 (66.7%) | 6 (46.2%) | 9 (90.0%) | |

| Trauma | 6 (17.1%) | 1 (8.3%) | 5 (38.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Remifentanil infusion | |||||

| Dose, mg | 43.43 33.16 | 35.00 11.68 | 59.23 49.57 | 33.00 11.60 | 0.092 |

| Norepinephrine infusion | |||||

| Ever used | 23/35 | 9/12 | 7/13 | 7/10 | 0.280 |

| Dose (μg/kg/min) | 0.13 0.11 | 0.12 0.11 | 0.13 0.12 | 0.13 0.10 | 0.954 |

| Dopamine infusion | |||||

| Ever used | 9/35 | 0/12 | 3/13 | 6/10 | 0.006 |

| Dose (μg/kg/min) | 0.98 0.65 | 0.45 0.14 | 1.26 0.93 | 0.99 0.47 | 0.411 |

| WBC (109/L) | 11.37 4.44 | 10.87 4.61 | 10.62 3.98 | 12.95 4.84 | 0.421 |

| HGB (g/L) | 108.91 20.83 | 111.92 20.63 | 104.62 24.10 | 110.90 17.37 | 0.653 |

| PLT (109/L) | 134.00 [116.50, 157.00] | 140.50 [131.00, 174.25] | 128.00 [87.00, 149.00] | 127.50 [118.00, 188.25] | 0.504 |

| PT(s) | 13.30 [12.60, 14.40] | 13.75 [12.52, 14.60] | 13.60 [12.70, 14.40] | 12.80 [12.38, 13.75] | 0.692 |

| ALT (U/L) | 23.70 [12.50, 35.60] | 19.55 [11.03, 26.77] | 28.20 [12.80, 42.40] | 21.95 [18.33, 36.68] | 0.398 |

| AST (U/L) | 41.50 [24.50, 108.15] | 48.95 [19.48, 94.07] | 37.40 [24.70, 137.20] | 42.05 [31.98, 51.50] | 0.921 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 18.70 [13.35, 34.75] | 18.40 [16.45, 37.47] | 18.70 [12.70, 26.40] | 31.10 [14.75, 35.68] | 0.578 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 0.00 [0.00, 7.60] | 0.00 [0.00, 1.43] | 0.00 [0.00, 10.60] | 2.45 [0.00, 13.02] | 0.367 |

| IBIL (μmol/L) | 12.30 [8.10, 20.85] | 12.95 [7.90, 33.22] | 12.30 [8.70, 15.80] | 13.10 [8.68, 21.02] | 0.804 |

| ALB (g/L) | 37.01 5.98 | 37.82 5.94 | 33.78 5.80 | 40.24 4.42 | 0.026 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 10.15 [6.92, 12.49] | 10.28 [6.74, 11.08] | 10.92 [8.57, 15.09] | 7.94 [6.42, 10.40] | 0.412 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 84.70 [58.35, 102.30] | 66.10 [50.62, 91.45] | 85.50 [55.10, 123.40] | 86.80 [72.85, 93.00] | 0.336 |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/mL) | 606.30 [166.35, 1476.50] | 738.90 [163.35, 3089.00] | 372.10 [97.69, 1056.00] | 707.85 [483.57, 1046.28] | 0.644 |

| cTnT (μg/L) | 77.71 [29.59, 407.05] | 119.60 [18.70, 672.43] | 38.37 [26.82, 83.70] | 77.35 [44.25, 408.68] | 0.595 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 0.99 [0.37, 8.12] | 0.78 [0.15, 1.70] | 1.49 [0.44, 11.63] | 0.98 [0.56, 7.72] | 0.487 |

| IL‐6 (pg/mL) | 120.07 [32.70, 239.10] | 99.96 [40.23, 258.78] | 70.70 [27.40, 141.10] | 120.44 [51.80, 382.03] | 0.754 |

Note: Categorial data were presented as number or percentages; continuous variables with normal distribution were presented as mean ± SD, variables with skewed distribution were expressed as median (interquartile range).

Abbreviations: ALB, albumin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatine; cTNT, cardiac troponin T; HGB, hemoglobin; ICU, intensive care unit; IL‐6, Interleukin‐6; NT proBNP, N‐Terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; PCT, procalcitonin; PLT, platelet; PT, prothrombin; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; TBIL, total bilirubin; WBC, white blood cell count.

3.2. Pharmacokinetics of Remimazolam

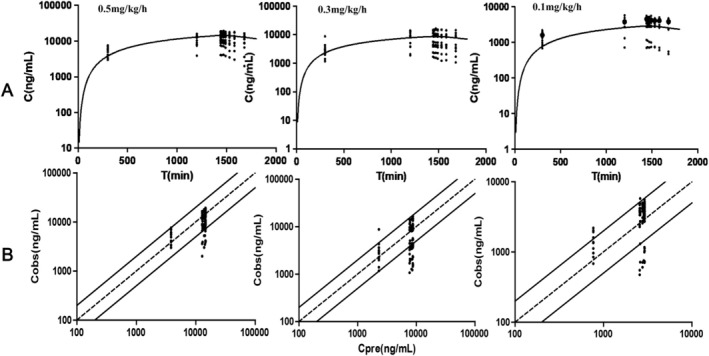

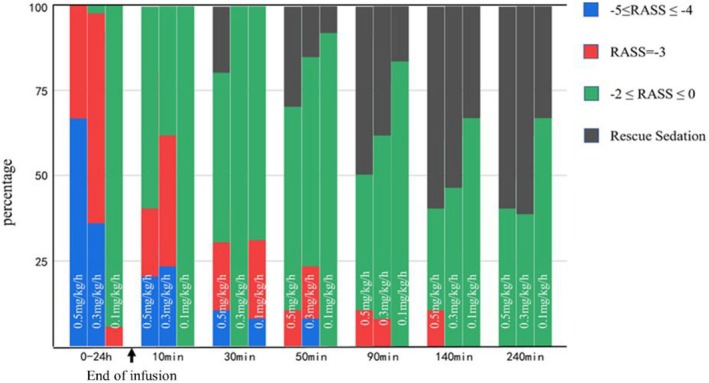

All blood samples were collected according to the scheduled time points, and a total of 35 subjects were included in the data analysis (Table 2) The conversion rate of remimazolam to its metabolite (K m) was determined to be 0.018 min−1, while the elimination rate of the remimazolam metabolite (K e) was found to be 0.00078 min−1. A one‐compartment model with linear disposition and elimination described remimazolam and metabolite plasma pharmacokinetics and was similar to a two‐compartment model to describe plasma pharmacokinetics (difference in Akaike Information Criterion [dAIC]: −4.91). To analyze the plasma pharmacokinetics, one compartment modeling was applied. Figure 1 illustrates the drug concentration‐time profiles for the three distinct dose groups, demonstrating the efficiency of the model fitting. Figure 2 portrays the drug concentration‐time profiles for the metabolite and the model fitting efficiency. Regardless of the changes in dosage, the 0.5 mg/kg/h group exhibited only negligible variations in the half‐life, clearance (CL), volumes of distribution (V d), and mean residence time (MRT) compared to the other groups. The observed AUC values were correlated with the administered dosage. The median mean clearance rate of remimazolam during continuous infusion is 22.23 mL/min/kg, with a median half‐life of 101.791 min. Remimazolam showed a short MRT of 78.51 min and large V d (2656.58 [IQR, 2147.14–4028.14] mL/kg). The metabolite of remimazolam exhibited a protracted elimination process, characterized by a low clearance rate (0.49 mL/kg/min) and an extended half‐life (656.02 min). The distribution volume of remimazolam metabolites is 574.08 mL/kg, and its median MRT is 645.96 min. Throughout the 24‐h remimazolam infusion, no dexmedetomidine rescue was required. All subjects were achieved satisfactorily sedated depth differing by dose: 0.5 mg/kg/h resulted in deep sedation, 0.3 mg/kg/h in moderate sedation, and 0.1 mg/kg/h in mild sedation(Figure 3).

TABLE 2.

Pharmacokinetics parameters of remimazolam and metabolite.

| Parameters | Overall | 0.1 mg/kg/h | 0.3 mg/kg/h | 0.5 mg/kg/h | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remimazolam | |||||

| t 1/2 (min) | 101.79 [77.00, 155.09] | 108.69 [75.59, 150.21] | 115.51 [86.35, 218.89] | 92.12 [62.35, 167.48] | 0.389 |

| AUC0–t (μg min/mL) | 370.29 [172.99, 623.97] | 136.53 [95.66, 513.86] | 360.89 [209.584, 876.04] | 464.53 [372.09, 546.49] | 0.013 |

| AUC0–∞ (μg min/mL) | 401.96 [177.22, 712.33] | 138.09 [98.09, 518.40] | 365.40 [215.47, 1084.21] | 461.53 [375.25, 562.00] | 0.010 |

| λz (L/min) | 0.006 [0.004, 0.009] | 0.006 [0.004, 0.009] | 0.006 [0.003, 0.008] | 0.007 [0.005, 0.01] | 0.136 |

| V d (mL/kg) | 2656.58 [2147.14, 4028.14] | 2524.34 [942.25, 3587.22] | 2585.83 [2239.25, 4361.87] | 3047.07 [2243.05, 5326.41] | 0.466 |

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 22.23 [11.68, 31.83] | 17.92 [6.01, 24.52] | 19.70 (6.69, 33.45) | 26.00 (21.38, 31.98) | 0.149 |

| MRT (min) | 78.51 [66.00, 90.58] | 75.70 [66.03, 84.61] | 89.87 [70.64, 101.27] | 70.84 [57.61, 83.70] | 0.268 |

| Metabolite | |||||

| t 1/2 (min) | 656.02 [363.66, 1219.28] | 435.99 [249.09, 1379.09] | 656.02 [520.81, 1233.96] | 708.89 [454.07, 1630.50] | 0.411 |

| AUC0–t (μg min/mL) | 5145.10 [3636.00, 10227.66] | 3653.46[2729.65, 4221.03] | 8550.49 [3786.87, 10391.08] | 11063.64 [7939.58, 13444.99] | 0.001 |

| AUC0–∞ (μg min/mL) | 12834.54 [5947.28, 30552.86] | 6256.00 [4234.82, 12278.36] | 9698.90 [6353.84, 40974.70] | 23435.96 [12039.16, 64757.68] | 0.022 |

| λz (L/min) | 0.0009 [0.0004, 0.0014] | 0.0013 [0.0005, 0.0023] | 0.0008 [0.0004, 0.0012] | 0.0009 [0.0004, 0.0013] | 0.513 |

| V d (mL/kg) | 574.08 [417.32, 786.64] | 412.66 [245.14, 575.69] | 742.23 [404.28, 1418.18] | 646.31 [499.36, 786.64] | 0.074 |

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 0.49 [0.31, 0.80] | 0.38 [0.20, 0.57] | 0.74 [0.23, 1.44] | 0.51 [0.28, 1.05] | 0.542 |

| MRT (min) | 645.96 [370.38, 1632.42] | 710.09 [201.48, 4840.98] | 706.15 [416.26, 1985.09] | 642.69 [321.58, 3200.00] | 0.969 |

Note: Categorial data were presented as number or percentages; continuous variables with normal distribution were presented as mean ± SD, variables with skewed distribution were expressed as median (interquartile range).

Abbreviations: AUC0–∞, area under the curve corresponding to the moment of the 0 to the time at infinity; AUC0–t , area under the curve corresponding to the moment of the 0 to the last point; CL, clearance; MRT, mean residence time; t 1/2, half‐time; V d, apparent volume of distribution.

FIGURE 1.

The goodness of fit plot for the one compartment model. (A) Semi‐logarithmic plot of concentration‐time profiles of remimazolam. (B) Predicted vs. observed concentration for remimazolam within 0.5–2 fold error range. C obs observed values of concentration, C pre predicted value of concentration.

FIGURE 2.

The goodness of fit plot for the one compartment model. (A) Semi‐logarithmic plot of concentration‐time profiles of remimazloam metabolite. (B) Predicted vs. observed concentration for remimazolam within 0.5–2 fold error range. C obs observed values of concentration, C pre predicted value of concentration.

FIGURE 3.

RASS scores of different groups.

3.3. Covariate Effects

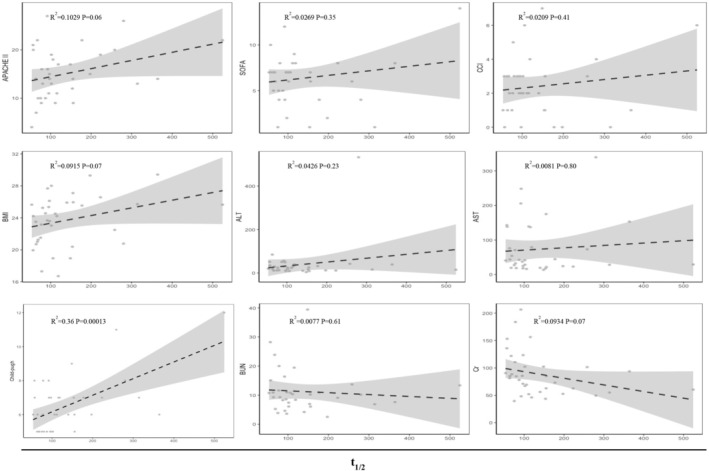

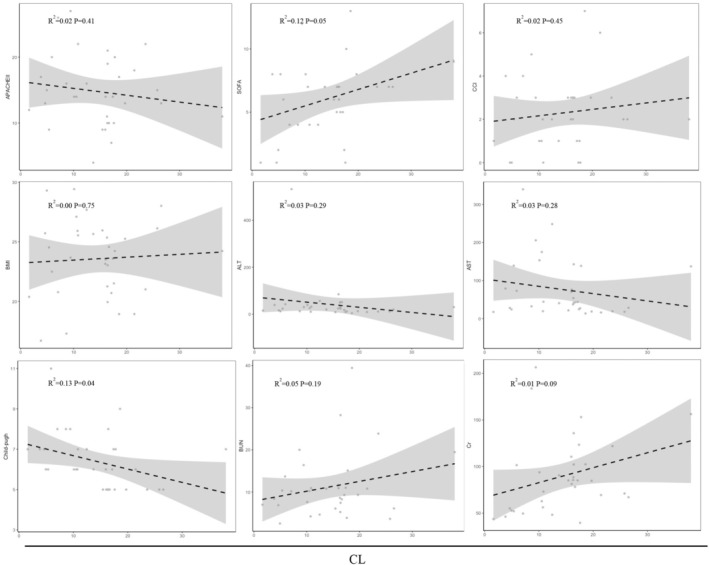

The covariates of baseline data showed their impact on the pharmacokinetics of remimazolam, as displayed in Figures 4 and 5. Similarly, the covariates of liver function laboratory parameters, including alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), exhibited no significant effect. The results of our correlation analysis suggest that the Child–Pugh score exerts a substantial influence on the half‐life (R 2 = 0.36, p = 0.00013) and clearance rate (R 2 = 0.13, p = 0.04). However, other renal laboratory measurements, as well as scores representing disease severity, did not provide any substantial evidence of a significant relationship with half‐life and clearance.

FIGURE 4.

Pearson correlation analysis of baseline data and half‐time.

FIGURE 5.

Pearson correlation analysis of baseline data and clearance.

3.4. Hemodynamics Effects

No instances of hypotension, heart rate abnormality, and hypoxemia were observed during remimazolam administration. Nevertheless the patient did not exhibit hypotension during the 24 h infusion of remimazolam, there was a notable statistical variance observed in relation to the baseline blood pressure. The mean baseline value for MAP was 85.01 ± 11.84 mmHg. The patient's average MAP at the time of administration was 86.19 ± 10.07 mmHg, which showed no significant difference compared to the time of administration. However, the average MAP at 30 min and 1 h after administration exhibited significant differences compared to the average MAP at the time of administration (86.19 [SD 10.07] vs. 78.07 [SD 11.58], p = 0.0002; 86.19 [SD 10.07] vs. 80.12 [SD 11.85] mmHg, p = 0.006). The MAP further showed differences until 30 min after discontinuation of the medication; no significant difference in MAP was observed from 30 min after discontinuation of remimazolam (86.19 [SD 10.07] vs. 84.45 [SD 10.51], p = 0.43). Over the 24 h of remimazolam administration, no instances of hypoxemia were reported, and no adverse effect on heart rate was observed upon discontinuation of the medication.

4. Discussion

Remimazolam is a relatively new ultra‐short‐acting sedation agent that was extensively studied and used in clinical practice for procedural sedation and general anesthesia [4, 6, 9]. Previous studies have shown remimazolam is a safe and effective alternative for sedation in mechanically ventilated patients [3, 13]. Consistent with prior research, our study revealed the successful administration of remimazolam as a sedative in patients undergoing intubation in the intensive care unit (ICU), with manageable hemodynamic adverse effects. The pharmacokinetic research data demonstrated that the pharmacokinetic profile of remimazolam in ICU patients undergoing intubation aligned closely with the one‐compartment model. Contrary to prior research in general anesthesia and endoscopy, the administration of a maintenance dose of 0.1–0.3 mg/kg/h of remimazolam effectively sustained light to moderate sedation levels among intubated patients in the ICU [14, 15, 16]. Nevertheless, research has revealed that compromised liver function can result in decreased drug clearance and extended half‐life. These findings hold paramount significance in guiding sedation management for ICU intubated patients in clinical practice.

The selection of different models may be because of differences in dosing regimen, sampling scheme, study population, and analytical method. In this study, the pharmacokinetic parameters of remimazolam were initially calculated and evaluated using a one‐compartment model. In our model development, we chose the one‐compartment model as it was simpler and still a good fit, even though the AIC values of the one‐compartment and two‐compartment models were close. Nevertheless, both the semi‐logarithmic plot and AIC suggest that our model aligns with the one‐compartment model. Taking into account the physiological aspect, remimazolam, an ester drug, undergoes rapid metabolism by the enzyme carboxylesterase 1 (CES‐1), primarily located in the liver. The distributional metabolic process of remimazolam followed linear kinetics. Previous studies have explored the potential of two and three‐compartment models as structural PK models in humans, and the one‐compartment model was found to be optimal with our dataset [10, 17, 18]. Besides, our experimental design involved high‐temporal‐resolution sampling for 24 h following the cessation of infusion, which differed from the majority of other studies employing shorter sampling periods. Empirical evidence revealed a more favorable correspondence with the drug‐time profiles of remimazolam and its metabolite using the one‐compartment model, which was consistent with a previously reported article [19]. In the initial assessment, remimazolam demonstrated large V d and rapid clearance with a terminal elimination half‐life of 101.79 min, compared with a terminal elimination half‐life for midazolam of 3.34 ± 1.47 h and dexmedetomidine for 122 [IQR, 86–192] min [20, 21]. Analogous to the alterations in pharmacokinetic parameters of the analgesics and sedatives frequently used in the ICU, remimazolam did exhibit an extended half‐life or prolonged efficacy when used as a continuous infusion [22]. This issue appeared controversial because there was currently no studies on the prolonged elimination half‐life of remimazolam after infusion, but previous articles reported a terminal half‐life of 65.6 min for remimazolam after 4 h continuous infusion and a terminal half‐life of 37.8–70.0 min after the single ascending dose infusion [18, 19]. Our study indicated that the terminal half‐life of remimazolam is 101.79 min following a 24‐h infusion period, similar to the changes in pharmacokinetic parameters observed in continuous infusion and intermittent administration of midazolam and propofol [23, 24, 25, 26]. In critically ill patients, modifications in plasma protein binding and the presence of multi‐organ disease may lead to reduced elimination and an increased V d. Conversely, in ICU patients without significant end‐organ disease in our study, remimazolam clearance does not have been diminished, thereby prolonging the elimination half‐life. In studies conducted by Peking University First Hospital and University Hospital Erlangen, the clearance of remimazolam was 20.8 ± 4.7 mL/min/kg in a 2 h continuous infusion and 1.15 ± 0.12 L/min in a 4 h continuous infusion, which showed a comparable clearance compared to our 24 h continuous infusion results [18, 19]. Based on the final population PK model, remimazolam was found to distribute into a small steady‐state V d (35.4 ± 4.2 L) in healthy volunteers, which is smaller than the V d (2656.58 mL/kg) in our single‐compartment model [18]. This trend of pharmacokinetic alterations was anticipated, as the distribution of lipophilic drugs was often reported to be slightly higher in critically ill patients compared to a healthy population. This indicated that the clearance rate of remimazolam remains consistent even when administered at high doses to patients in ICU, regardless of increased distribution and extended infusion durations. Nevertheless, its half‐life was prolonged in comparison to intravenous injection and short‐term infusion.

Remimazolam is rapidly and extensively metabolized by liver carboxylesterase, leading to the production of a pharmacologically inert carboxylic acid metabolite called CNS7054. This metabolite demonstrates significantly lower affinity, approximately 300 times less, when compared to the original compound [27]. The elimination half‐life of CNS7054 was 116 ± 22 min after a bolus dose, far shorter than our median half‐life of 656.02 min [18]. In comparison to the metabolite conversion rate of 0.018 min−1 observed in our study, previous research documented a rate of 0.024 min−1, demonstrating a similar trend in our findings. Our remimazolam metabolite exhibited a low clearance rate (0.49 mL/kg/min), which is lower than the clearance of CNS7054 reported in previous studies (0.078 ± 0.017 L/min) after a bolus dose. Due to variations in model structures, direct comparisons between the results of this study and others are not feasible. The prolonged half‐life, a decreased V d and slower clearance rate of the metabolite observed after continuous infusion administration may be attributed to the specific drug delivery method employed in our study. Since CNS7054 was pharmacologically inactive, its extended half‐life in patients after continuous infusion did not have any clinical significance.

During the 24‐h continuous infusion of remimazolam, the RASS scores of the participants were assessed throughout the infusion duration to ascertain the attained levels of sedation. Due to the novelty or limited research on remimazolam, comprehensive data regarding its precise dosage recommendations for patients in the ICU are still lacking. In our pilot study, the dose of 1 mg/kg/h, which is recommended for general anesthesia, resulted in the patient remaining deeply sedated (RASS = −5) throughout the 24‐h infusion. Therefore, it was apparent that the dose of 1 mg/kg/h was excessive for ICU light or moderate sedation, and this dose‐finding study explored lower doses to determine the appropriate dosage range for ICU light sedation. This dose‐finding study identified a range of doses (0.1–0.5 mg/kg/h) that achieved the desired level of sedation for ICU patients without causing excessive sedation. However, patients maintained a profound sedative state when subjected to a continuous infusion of 0.5 mg/kg/h, experienced a moderate level of sedation at 0.3 mg/kg/h, and only achieved a mild sedation level at 0.1 mg/kg/h for the majority of the time. There was no variation in the dosage of analgesics administered among the different groups during the drug consumption process. Considering the safety and efficacy properties, the continuous infusion of remimazolam was recommended at 0.1–0.3 mg/kg/h in mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU. This information provides valuable guidance in optimizing the use of remimazolam in the ICU setting.

An analysis was conducted to investigate how demographics and laboratory covariates, such as albumin, bilirubin, and creatinine can influence the pharmacokinetics of remimazolam. From an evidence‐based perspective, the metabolism of remimazolam seems to be independent of hepatic and renal function [9]. Previous studies had shown that patients with severe hepatic impairment, as indicated by Child–Pugh scores of 10 or higher, exhibit a 38.1% increase in exposure, as measured by higher values for AUC(0–∞) (171 ng▪ h/mL), compared to individuals with normal liver function (132 ng ▪h/mL). The recovery to a fully awake state of consciousness was slower for subjects in the hepatically impaired groups (moderate 12.1 min; severe 16.7 min) compared with healthy control subjects (8.0 min). In our research, numerous covariate effects were examined, revealing no statistically significant impact on the study outcomes. These covariates included variables such as age, sex, BMI, history of alcohol consumption, liver enzymes, and renal function. The correlation analysis showed a significant difference in liver function and drug half‐life for all 35 patients, indicating caution is needed for potential overdosing in patients with liver impairment [10].

Furthermore, the hemodynamics profile of remimazolam was comparable across all groups. Hypotension and bradycardia have been reported as potential side effects associated with the infusion of various sedation agents, particularly propofol and dexmedetomidine infusions. Septic patients without shock who received continuous infusions of propofol and dexmedetomidine showed similar frequencies of negative hemodynamic events [28]. During the examination of vasoactive drug utilization, no statistically significant difference was found in the administration of norepinephrine; however, a notable discrepancy was observed in the administration of dopamine among various dosage cohorts. Nevertheless, in our study, the incidence of hypotension with remimazolam over 24 h was low. However, there may be fluctuations in blood pressure during the medication process, which can differ from the patient's baseline blood pressure values. There were no differences in the dosages of vasoactive drugs administered during the drug delivery process. One plausible explanation is that a subset of the patients included in our study had undergone surgical procedures, thereby potentially introducing variables such as intraoperative bleeding and postoperative vascular tension imbalance.

Nonetheless, the present study has several limitations. Firstly, our study incorporated a small patient sample size and limited concentration measurements during the distribution phase due to ethical concerns about blood drawing. Collecting more comprehensive samples during the distribution and elimination phases to simulate continuous infusion data in ICU patients could better clarify the PK characteristics of remimazolam. Secondly, a high number of post‐surgical patients were included, whereas those on continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) were excluded. Besides, the BMI of participants was not diverse, which helped reduce subject variability for this preliminary study. Further studies focusing on specific pathophysiological states are necessary to investigate the metabolism of remimazolam in these patient populations. Thirdly, plasma carboxylesterase concentrations were not considered in the covariate study as carboxylesterase is predominantly expressed in the liver and minimally in serum plasma [29]. Despite elevated liver function markers (ALT, AST) indicating acute liver injury, no covariate effects on remimazolam pharmacokinetics were noted. Nevertheless, patients with higher Child–Pugh scores showed a decrease in clearance and extended half‐life, consistent with previous research [10]. Additional studies are needed to investigate the relationship between carboxylesterase activity, Child–Pugh score, and remimazolam pharmacokinetics.

In conclusion, remimazolam maintains rapid clearance and a one‐compartment distribution even after a 24‐h infusion, but has a longer half‐life in ICU patients than with shorter infusions. For ICU sedation, 0.5 mg/kg/h is suitable for deep sedation, while 0.1–0.3 mg/kg/h is appropriate for light to moderate sedation. It shows promise for intubated ICU patients, with manageable hemodynamic adverse effects. Hepatic dysfunction can cause drug accumulation, and caution is essential, so careful dosing is essential. Clinicians should tailor doses to individual needs and monitor for adverse effects.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: M.S. and X.Z. Acquisition of data: L.S., W.Z., and Y.L. Data and project management: J.H., Y.Z., and H.W. Data cleaning and analysis: L.S., H.W., and Y.L. Interpreted the data: J.H., Y.Z., and X.Z. Drafting of the manuscript: J.H. and Y.Z. Approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors.

Ethics Statement

All of the participants signed an informed consent form before data or sample collection, according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the patients who have contributed to this paper. We would like to thank all doctors who referred patients to our clinic and thank all patients for their trust.

Hu J., Zhao Y., Shao L., et al., “Pharmacokinetic Properties and Therapeutic Effectiveness of Remimazolam in ICU Patients With Mechanical Ventilation: A Preliminary Study,” Pharmacology Research & Perspectives 13, no. 3 (2025): e70130, 10.1002/prp2.70130.

Funding: This work was supported partially by grants from China International Medical Foundation (NO. Z‐2017‐24‐2028‐06 and NO.Z‐2018‐35‐2001) and a grant from Jiangsu Research Hospital Association for Analgesia and Sedation in the Critically ill (NO. SYHKJ‐QG‐2025‐01).

Jing Hu and Yuhan Zhao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Mengxiang Su, Email: sumengxiang@cpu.edu.cn.

Xiangrong Zuo, Email: zuoxiangrong@njmu.edu.cn.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- 1. Devlin J. W., Skrobik Y., Gélinas C., et al., “Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU,” Critical Care Medicine 46, no. 9 (2018): e825–e873, 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dubovsky S. L. and Marshall D., “Benzodiazepines Remain Important Therapeutic Options in Psychiatric Practice,” Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 91, no. 5 (2022): 307–334, 10.1159/000524400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tang Y., Yang X., Yu Y., et al., “Remimazolam Besylate Versus Propofol for Long‐Term Sedation During Invasive Mechanical Ventilation: A Pilot Study,” Critical Care 26, no. 1 (2022): 279, 10.1186/s13054-022-04168-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Keam S. J., “Remimazolam: First Approval,” Drugs 80, no. 6 (2020): 625–633, 10.1007/s40265-020-01299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Egan T. D., “Is Anesthesiology Going Soft?: Trends in Fragile Pharmacology,” Anesthesiology 111, no. 2 (2009): 229–230, 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ae8460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee A. and Shirley M., “Remimazolam: A Review in Procedural Sedation,” Drugs 81, no. 10 (2021): 1193–1201, 10.1007/s40265-021-01544-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chae D., Kim H. C., Song Y., Choi Y. S., and Han D. W., “Pharmacodynamic Analysis of Intravenous Bolus Remimazolam for Loss of Consciousness in Patients Undergoing General Anaesthesia: A Randomised, Prospective, Double‐Blind Study,” British Journal of Anaesthesia 129, no. 1 (2022): 49–57, 10.1016/j.bja.2022.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pastis N. J., Yarmus L. B., Schippers F., et al., “Safety and Efficacy of Remimazolam Compared With Placebo and Midazolam for Moderate Sedation During Bronchoscopy,” Chest 155, no. 1 (2019): 137–146, 10.1016/j.chest.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sneyd J. R. and Rigby‐Jones A. E., “Remimazolam for Anaesthesia or Sedation,” Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 33, no. 4 (2020): 506–511, 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stohr T., Colin P. J., Ossig J., et al., “Pharmacokinetic Properties of Remimazolam in Subjects With Hepatic or Renal Impairment,” British Journal of Anaesthesia 127, no. 3 (2021): 415–423, 10.1016/j.bja.2021.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang L., Wang Y., Ma L., et al., “Cardiopulmonary Adverse Events of Remimazolam Versus Propofol During Cervical Conization: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Drug Design, Development and Therapy 17 (2023): 1233–1243, 10.2147/dddt.S405057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou Y., Wang H., Jiang J., and Hu P., “Simultaneous Determination of Remimazolam and Its Carboxylic Acid Metabolite in Human Plasma Using Ultra‐Performance Liquid Chromatography‐Tandem Mass Spectrometry,” Journal of Chromatography. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences 976‐977 (2015): 78–83, 10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen X., Zhang J., Yuan S., and Huang H., “Remimazolam Besylate for the Sedation of Postoperative Patients Undergoing Invasive Mechanical Ventilation in the ICU: A Prospective Dose–Response Study,” Scientific Reports 12, no. 1 (2022): 19022, 10.1038/s41598-022-20946-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borkett K. M., Riff D. S., Schwartz H. I., et al., “A Phase IIa, Randomized, Double‐Blind Study of Remimazolam (CNS 7056) Versus Midazolam for Sedation in Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy,” Anesthesia and Analgesia 120, no. 4 (2015): 771–780, 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doi M., Morita K., Takeda J., Sakamoto A., Yamakage M., and Suzuki T., “Efficacy and Safety of Remimazolam Versus Propofol for General Anesthesia: A Multicenter, Single‐Blind, Randomized, Parallel‐Group, Phase IIb/III Trial,” Journal of Anesthesia 34, no. 4 (2020): 543–553, 10.1007/s00540-020-02788-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pambianco D. J., Borkett K. M., Riff D. S., et al., “A Phase IIb Study Comparing the Safety and Efficacy of Remimazolam and Midazolam in Patients Undergoing Colonoscopy,” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 83, no. 5 (2016): 984–992, 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eisenried A., Schuttler J., Lerch M., Ihmsen H., and Jeleazcov C., “Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Remimazolam (CNS 7056) After Continuous Infusion in Healthy Male Volunteers: Part II. Pharmacodynamics of Electroencephalogram Effects,” Anesthesiology 132, no. 4 (2020): 652–666, 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schuttler J., Eisenried A., Lerch M., Fechner J., Jeleazcov C., and Ihmsen H., “Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Remimazolam (CNS 7056) After Continuous Infusion in Healthy Male Volunteers: Part I. Pharmacokinetics and Clinical Pharmacodynamics,” Anesthesiology 132, no. 4 (2020): 636–651, 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sheng X. Y., Liang Y., Yang X. Y., et al., “Safety, Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties of Single Ascending Dose and Continuous Infusion of Remimazolam Besylate in Healthy Chinese Volunteers,” European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 76, no. 3 (2020): 383–391, 10.1007/s00228-019-02800-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iirola T., Ihmsen H., Laitio R., et al., “Population Pharmacokinetics of Dexmedetomidine During Long‐Term Sedation in Intensive Care Patients,” British Journal of Anaesthesia 108, no. 3 (2012): 460–468, 10.1093/bja/aer441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jakob S. M., Ruokonen E., Grounds R. M., et al., “Dexmedetomidine vs Midazolam or Propofol for Sedation During Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation: Two Randomized Controlled Trials,” JAMA 307 (2012): 1151–1160, 10.1001/jama.2012.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saari T. I., Uusi‐Oukari M., Ahonen J., and Olkkola K. T., “Enhancement of GABAergic Activity: Neuropharmacological Effects of Benzodiazepines and Therapeutic Use in Anesthesiology,” Pharmacological Reviews 63, no. 1 (2011): 243–267, 10.1124/pr.110.002717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swart E. L., Zuideveld K. P., De Jongh J., Danhof M., Thijs L. G., and Strack van Schijndel R. M., “Comparative Population Pharmacokinetics of Lorazepam and Midazolam During Long‐Term Continuous Infusion in Critically Ill Patients,” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 57, no. 2 (2004): 135–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beigmohammadi M. T., Hanifeh M., Rouini M. R., Sheikholeslami B., and Mojtahedzadeh M., “Pharmacokinetics Alterations of Midazolam Infusion Versus Bolus Administration in Mechanically Ventilated Critically Ill Patients,” Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 12, no. 2 (2013): 483–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iirola T., Aantaa R., Laitio R., et al., “Pharmacokinetics of Prolonged Infusion of High‐Dose Dexmedetomidine in Critically Ill Patients,” Critical Care 15 (2011): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McKeage K. and Perry C. M., “Propofol: A Review of Its Use in Intensive Care Sedation of Adults,” CNS Drugs 17 (2003): 235–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hu Q., Liu X., Wen C., Li D., and Lei X., “Remimazolam: An Updated Review of a New Sedative and Anaesthetic,” Drug Design, Development and Therapy 16 (2022): 3957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benken S., Madrzyk E., Chen D., et al., “Hemodynamic Effects of Propofol and Dexmedetomidine in Septic Patients Without Shock,” Annals of Pharmacotherapy 54, no. 6 (2020): 533–540, 10.1177/1060028019895502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Di L., “The Impact of Carboxylesterases in Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics,” Current Drug Metabolism 20, no. 2 (2019): 91–102, 10.2174/1389200219666180821094502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.