Summary

Trauma care in India has made significant progress in the past two decades. However, a coordinated and concerted effort has sometimes been lacking. Information on the various aspects of injury prevention, trauma education, and prehospital and in-hospital trauma care in India has been available in a fragmented manner so far. This comprehensive review aims to understand in detail and bring together the various facets of injury prevention and trauma care in India, including the efforts being put at various levels to tackle the problem. The article also includes a detailed SWOT analysis, assessing strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats and suggests strategies to overcome them.

Keywords: Geography; Healthcare disparities; Health Care Quality, Access, And Evaluation; Information Dissemination

Introduction

India is the most populous country in the world and has a growing economy. Estimates suggest that the Indian economy, currently ranked fifth with over 4 trillion dollars in Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is likely to grow to US$5 trillion, becoming the third largest in 5 years. The economic growth is across a wide span of sectors, and the nation is using its strength in informational technology, services, agriculture, and manufacturing to grow the economy. A young and adept workforce is enabling the growth of this nation into a future industrial powerhouse. Along with the growth in industrialization and urbanization, highway infrastructure, fast-moving automotive, and public transport provide necessary access to this large country. However, these factors are also unfortunately responsible for increasing trauma burden across the nation.

19 Indians die every hour due to road traffic injuries (RTIs).1 This translates to 9.5 deaths for every 100 000 people. For comparison, Sweden reports only 2 deaths per 100 000 population since initiating ‘Vision Zero’.2 In 2022, nearly 33.8% (155 781 accidents) of all RTIs in India were fatal. Barring the transient dip during the COVID-19 years, the number of road accidents has remained steady (461 312 accidents in 2022), with a gradual rise in fatalities (168 491 deaths) (figure 1a). Another cause for concern is that while highways account for only 5% of the country’s road network, 55% of all RTIs occur on highways and account for 60% of all RTI-related mortalities.1 The morbidity rate from RTIs is equally alarming, with a disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) rate per 100 000 population of 1212 (95% uncertainty levels 978–1419).3 A worrying fact is that the data may not accurately reflect the actual situation as it is sourced from police records, does not account for deaths after 30 days, and many incidents in rural areas go unreported.4 Two independent estimates of RTI-related deaths from 20175 and 20196 showed 82% and 40% more deaths than the available data for those years. Data on injuries other than RTIs are even more poorly captured. As per WHO estimates for India, falls (225 000 deaths), deliberate self-harm (173 000 deaths), and interpersonal violence (51 000 deaths) were the biggest contributors to injury-related deaths.7

Figure 1. (a) Trends in road accidents and fatalities from 2018 to 2022. (b) Accident severity among states and union territories. Courtesy: Road Accident in India Report, Ministry of Road Transport and Highway.

As an example, traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major public health problem in India. An epidemiological study from the country has shown that almost 70% of all RTI-related fatalities involve a head injury, with 32% of them being due to isolated head injuries.8 Collation of these figures with the data available from governmental resources1 shows that at least 110 000 TBI injuries occur secondary to RTIs in India yearly. Due to the heterogeneity of care across India, outcomes of these TBIs vary significantly across different regions. A useful surrogate marker for outcome assessment is the fatality rate (persons killed per 10 000 vehicles). About 50% of the states have a fatality rate above the national average of 5.2.1 The low fatality rate of 1.2 in the National Capital Territory of Delhi reflects the better prehospital and neurotrauma care available in the city, with data from the Apex Level 1 Trauma Center showing equivalent outcomes to those in developed countries (table 1).9 This indicates that regional trauma systems could improve neurotrauma outcomes in LMICs. An important area that is still lacking is the neurorehabilitation of post-traumatic patients, particularly with TBI and spinal cord injuries. Studies show that there are 7.6 million patients living with TBI and spinal cord injury in India as of 2019.10 Estimates show that there are roughly 40 265 rehabilitation professionals, 3263 speech specialists, 2500 neurologists, 1800 neurosurgeons, and 200 palliative care physicians in India, catering to a population of 1.38 billion individuals.11 Addressing this epidemic requires a multifaceted approach, and several initiatives have been undertaken at various levels. However, access to comprehensive information on these efforts remains limited for healthcare professionals. There is a lack of available literature that describes the current state of trauma performed in a comprehensive fashion. Additionally, initiatives across key domains—including prehospital care, in-hospital management, injury prevention, and trauma education—often function in isolation. This review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of current strategies aimed at reducing injury-related mortality and morbidity, spanning the continuum of care from prehospital management to rehabilitation. Furthermore, it seeks to evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) associated with developing a countrywide trauma initiative uniquely suited for the largest country in the subcontinent.

Table 1. In-hospital mortality of patients with TBI across various countries.

| Study year | Data from | Mortality rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Minor head injury | Moderatehead injury | Severehead injury | ||

| Kagan and Baker 199443 | High-income country | 26.7 | NA | NA | 41.4 |

| Fakhry et al 200444 | High-income country | 28.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| Udekwu et al 200445 | High-income country | 21 | NA | NA | 31.5 |

| De Silva et al 200946 | High-income countries | NA | 8 | 14 | 30 |

| De Silva et al 200946 | Low-income and middle-income countries | NA | 5 | 15 | 51 |

| Agrawal et al 20159 | Delhi, India | 22 | 2 | 12 | 36 |

NA, not available; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Methods

The current manuscript was compiled by a team of expert trauma care providers working in various facets of trauma care, including prehospital care, trauma systems, trauma education including ATLS, trauma surgery, and emergency medicine. The authors were chosen based on their research profile, subject matter expertise, and a robust ongoing engagement with trauma development across the country. Each author was provided with a subsection based on their area of expertise. Each author then performed a systematic search of the following databases—MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Google Scholar using the keywords relevant to their section. Search terms included a combination of natural language phrases and Medical Subject Headings terms using ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ functions that captured their topics—India, trauma, burden, mortality, DALY, head injury, TBI, systems, registry, prehospital care, education, ATLS, trauma life support, health expenditure, insurance, economics and health schemes. During the course of the review, the lack of scientific literature on various facets of trauma care in India was glaring. The search was then extended to include targeted gray literature from governmental and non-governmental sources such as National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog, Ministry of Road Transport and Highways database, Directorate General of Health Services website, WHO, International Road Federation, ATLS India, National Medical Commission, and National Board of Examinations. Much of the information in the final manuscript is from publicly sourced data.

Results

Status of trauma care in India: the 4 Es

The National Road Safety Policy12 on preventing and improving RTIs in India is centered on the 3 Es—engineering, enforcement, and education—initially proposed by Julien Harvey.13 This has been expanded to include a fourth E-Emergency care. More recently, engineering has been subdivided to focus on road and vehicular engineering. The government passed the Good Samaritan Law14 in 2016 and amended the 29-year-old Motor Vehicles Act in 2019. This marked an essential step in bringing legislation on road safety into the 21st century by protecting good Samaritans, increasing the fines for traffic violations, bringing legislative accountability for poor road and vehicular engineering, and establishing a National Road Safety Board, among other measures.15 Policy-makers have also rolled out a voluntary star rating—Bharat New Car Assessment Programme, based on the Global NCAP—to improve vehicular safety standards. Both governmental and non-governmental organizations have taken an interest in educating common people about trauma. Multiple organizations are carrying out Road Safety Campaigns, and individual level 1 centers have also been conducting layperson trauma first responder courses to educate the public on basic airway, stop-the-bleed, and spine immobilization interventions. However, a structured national evidence-based education program is currently lacking.

Current emergency care systems in India

The initial major thrust on the various aspects of emergency and injury care services from the Ministry of Health, Government of India (MOH) has been predominately trauma-care centric, with the recent shift encompassing all the domains of emergency conditions (see box 1 for details).

Box 1. Central government schemes/initiatives.

Ninth Five Year Plan (1997–2002) and 10th Five Year Plan (2002–2007)

Pilot Project for strengthening emergency facilities along the highways.

11th Five Year Plan (2007–2012)

Assistance for capacity building for developing trauma care facilities in government hospitals on national highways.

116 trauma care centers envisaged along the Golden Quadrilateral highway corridor.

105/116 trauma care centers functional.

12th Five Year Plan (2012–2017)

Capacity building for developing trauma care facilities in government hospitals on national highways.

Funds for 80 trauma care facilities have been released out of 85 approved facilities.

Beyond 12th Five Year Plan

National Program for Prevention and Management of Trauma and Burn Injuries

Strengthening and upgrading of graded levels of trauma care facilities (levels 1, 2 and 3, ie, L-1 L-2 and L-3, level-1 being the highest level) and burn units, procurement of equipment and provisioning of manpower for 3 years in state government medical colleges and district hospitals.

Capacity building for doctors, nurses, paramedics, and community.

Awareness generation and Information, Education and Communication (IEC) campaigns.

Establishment of National Injury Surveillance, Capacity Building and Trauma Registry Center for collection, collation, maintenance, analysis, and reporting of data, as well as for capacity building activities.

Strengthening of rehabilitation centers at L-2 Trauma Care Facilities (TCFs).

Prehospital care in India

As of 2024, the most extensive organized prehospital trauma care system in the country works under the ambit of the National Ambulance Service (NAS), which is run under the National Health Mission (NHM). These services are popularly called the ‘1-0-8 or 1-0-2 emergency ambulance services’. ‘Dial 108’ is predominantly an emergency response system designed to attend to patients with critical illnesses and trauma. At the time of the launch of the National Rural Health Mission (a sub-mission of NHM) in 2005, no such ambulance network existed. Currently, 10 993 ambulances are being supported under 108 emergency transport systems by the NHM.16 These services are run on a public–private partnership model, where capital expenditure is provided by each state government, which calls for proposals and outsources contracts using a quality and cost-based criteria model. The AIS 125 standard for Ambulance Services (National Ambulance Code) categorizes ambulances into four main categories: A–D, with D being the most advanced (Advanced Life Support Ambulances). It also gives a detailed set of criteria for equipment and staffing of ambulances in the country.17 Ambulances under the NAS cover primary transfers from scene to hospital and interfacility transfers. These ambulances are staffed by one driver and one emergency medical technician (EMT). The EMTs are allied healthcare professionals exposed to 6 weeks of foundation training for Basic EMT certification. The training of EMTs has a classroom phase, a simulation center phase, an ambulance phase, and a hospital phase. Skills assessments use an objectively structured clinical evaluation methodology.

The 2021 annual report of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) did observe an overall improvement in ambulance services under the NHM, mainly regarding availability and accessibility. However, the ground reality shows significant gaps and avenues for improvement. A national-level survey results submitted to the government think tank NITI Ayog18 suggest that even though 91% of hospitals had in-house ambulances, trained paramedics needed to assist ambulance services were present only in 34%. Most hospitals lacked a prehospital arrival notification system, and trauma systems had a larger representation of government over private hospitals despite variability in proximity. An observational study of trauma patients in the prehospital setting evaluated the population that uses ambulance services.19 It confirmed three important findings suggested by previous studies. First, having a centralized emergency medical services (EMS) system rather than hospital-based ambulance transport allowed patients to be transported to the right level of care as required rather than a single predesignated facility. Second, the private healthcare sector in India was found to be largely unregulated, with providers who were underqualified or even unqualified to manage trauma. Additionally, corruption may exacerbate poor care, increasing costs or even creating barriers to care access.20 The study showed that prehospital data such as age, abnormal mental status, abnormal blood pressure or oxygenation, mobility, and multisystem injury predict 30-day mortality and could be used to triage patients to higher levels of care, potentially reducing morbidity and mortality. A critical finding was that the free-of-charge EMS system cared predominantly for patients most at risk for further impoverishment from their injuries—a rural/tribal (74%) and economically disadvantaged population (97%)—and transported them to primarily public hospitals (81%).

A review of the prehospital care scenario in the country described the current situation as ‘fragmented’.21 The review highlighted the need for a nationwide triage policy, standardized care protocols, world-class ambulance services augmented with effective paramedics, a robust prehospital notification system, an expansion of blood banks, and the lack of a structured training program for EMTs. In addition to training EMTs, educating the lay bystanders is an important component of prehospital care. A single pilot study from southern India reported that a structured layperson first responder training program had the ability to save lives.22

Emergency preparedness: a countrywide assessment

‘Emergency and Injury Care at Secondary and Tertiary Level Centers in India’—A Report of Current Status on Country Level Assessment18 was a national benchmark study carried out with the financial support of NITI Aayog and conducted by the Department of Emergency Medicine, Jai Prakash Narayan Apex Trauma Center (JPNATC), All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, which is the WHO Collaborating Center for emergency medicine and trauma care in the South East Asia Region. The report evaluated emergency departments (EDs) nationwide and compared them to government and private hospitals. As per the report, the ED accounted for 6%–12% of all patient visits to the hospital but only 5%–6% of overall hospital beds. Around 24% of these visits in adults and 9% in the pediatric age group were following trauma, and there was a huge burden of medicolegal cases (up to 21%). The report summarized their findings, concluding that hospital-based emergency and injury care suffered due to a lack of an integrated approach, as services providing trauma care, cardiac care, and pediatric and obstetric care were being provided at isolated centers. The lack of ED leadership, floor management, standard operating procedures, adequate infrastructure and manpower, and poor availability of critical care, round-the-clock operative care, blood transfusion services, and dedicated funds have worsened the situation. The live observation during this study revealed that door-to-resuscitation initiation time in critically ill or injured patients takes more than 15 min in 21%–52% of hospitals, and door-to-CT-scan time in patients with TBI was more than 45 min in 50% of tertiary care centers (medical colleges). Efforts have to be thus focused on a collaborative, protocolized approach to improve emergency preparedness throughout the country.

Trauma registries

The potential lack of data following the emergence of trauma centers in India was accompanied by the concurrent development of trauma registries. Initial efforts to establish trauma registries in India were localized and lacked standardization. Recognizing this gap, national initiatives, such as the National Trauma Registry supported by the (MoHFW, aimed to create a centralized database.23 Various states and institutions have also developed their registries. The trauma registries in India are designed to fulfill all four traditional components: data collection, data management, data analysis, and data reporting. Notable efforts at developing Indigenous trauma registries include the Australia–India Trauma Systems Collaboration24 25 and the Toward Improved Trauma Care Outcomes registry,26 27 both of which are currently closed. Others include the Trauma Registry–CMC (T-ReCS), a low-resource, single-center, fully software-based registry, and the Tamil Nadu Accident and Emergency Care Initiative (TAEI), the country’s first statewide trauma registry program.28 29 Several challenges hinder the effective implementation of trauma registries in India30,32: limited financial resources, inadequate staffing, lack of trained personnel, insufficient infrastructure, challenges in ensuring accuracy and data completeness, utilization of registry data for quality improvement, and political and bureaucratic hurdles to inform policy and practice based on registry data.

Despite these challenges, lessons learnt from the individual registry programs show that data-driven insights have facilitated identifying high-risk areas, optimizing resource allocation, and developing targeted interventions such as establishing trauma centers and implementing road safety measures. The development of regional trauma registries built on a similar platform will enable the eventual goal of a national registry in the future

Trauma training and education in India

In recent years, trauma education in India has witnessed significant progress, with a notable emphasis on specialized programs tailored to address the escalating burden of traumatic injuries. There are, at present, three avenues for training in trauma surgery: the Master of Surgery (MS) in Traumatology and Surgery, the Master of Chirurgiae (MCh) in Trauma Surgery and Critical Care, and the Fellowship of the National Board (FNB) in Trauma and Acute Care. These programs nurture surgeons in delivering comprehensive care, from initial patient assessment and resuscitation to surgical intervention and postoperative critical care, all while emphasizing the importance of rehabilitation.33 The MS in Traumatology and Surgery program is a foundational postgraduate course, and the MCh in Trauma Surgery and Critical Care is a specialized program following basic postgraduate surgical education. The FNB program focuses on both trauma and acute care surgery.34,36 These varied courses aim to strengthen trauma care at multiple levels, with the MS program improving trauma care at levels 2 and 3 centers and the MCh and FNB programs aimed at level 1 centers. However, at present, these courses are available only in select government and private institutions, limiting accessibility, awareness, and popularity. Also, with the graduated pool of these surgeons practicing a mix of trauma surgery, emergency general surgery, and surgical critical care to varying degrees depending on the institution/place of work, there is a lack of clarity regarding the exact role of this new cadre of ‘trauma surgeons’.33

Alongside the development of specialized trauma training, disseminating the fundamental tenets of trauma care has been an important area of focus through the Advanced Trauma Life Support Course (ATLS). The ATLS Course commenced in India in 2007 with Dr. Chris Kaufman, International ATLS Chair, visiting the JPNATC, AIIMS, New Delhi. A Memorandum of Understanding was then undertaken between the Indian Society of Trauma and Acute Care to develop the first ATLS site. An entity named ‘ATLS India’ was created to develop and promote the ATLS Program in India. Back-to-back provider and instructor courses were held at the first site from 9 April 2009 to 16 April 2009. After that, the growth of new sites was slow during the first decade but has since picked up, with currently 35 active sites successfully running multiple courses throughout the year (table 2).

Table 2. ATLS provider courses in India.

| No. | Year | ATLS provider courses | ATLS instructor courses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of participants | No. of courses | Total no. of participants | No. of courses | ||

| 1 | 2009 | 176 | 11 | 42 | 4 |

| 2 | 2010 | 483 | 30 | 42 | 4 |

| 3 | 2011 | 490 | 28 | 33 | 3 |

| 4 | 2012 | 596 | 34 | 46 | 4 |

| 5 | 2013 | 676 | 38 | 55 | 5 |

| 6 | 2014 | 811 | 45 | 48 | 4 |

| 7 | 2015 | 832 | 46 | 53 | 5 |

| 8 | 2016 | 1250 | 69 | 35 | 3 |

| 9 | 2017 | 986 | 54 | 23 | 2 |

| 10 | 2018 | 589 | 40 | 48 | 4 |

| 11 | 2019 | 1214 | 77 | ||

| 12 | 2020 | 498 | 30 | ||

| 13 | 2021 | 1008 | 63 | ||

| 14 | 2022 | 1456 | 91 | ||

| 15 | 2023 | 1658 | 107 | ||

| 16 | 2024 | 760 | 48 | ||

| Total | 13 483 | 811 | 425 | 38 | |

ATLS, Advanced Trauma Life Support.

In India, the courses are conducted the same way they are in the USA. The lecture sessions have a similar organization, but the lecturers are allowed to deviate to local languages to provide context to local conditions pertaining to trauma. For example, women often ride in the back seat without helmets while traveling in a two-wheeler. Additionally, wearing a dupatta or a cloth covering can potentially get caught in the rear wheel and cause accidents. These regional contexts make the teaching very effective. It is routine around the country to see participation from faculty in orthopedics, neurosurgery, urology, and anesthesia, with significant engagement in lectures and skills stations. The skill stations are strictly structured as per ATLS specifications. Course sites varied from government to private hospitals. The leadership team conducting these courses is incredibly involved, and most keep aside their daily practice for 3 days for the ATLS in-person course. The participants were predominantly faculty at assistant to professor level, with few residents. These candidates belonged to various disciplines, with emergency medicine leading the way, followed by orthopedics, anesthesia, and general surgery. This is a change to what is seen in the USA. Each site often conducts more than 4–5 courses a year. The cost of the course varies from 10 000 to 25 000 Indian Rupees. This is considered reasonable by local standards. The conducting universities do not view it as an economic initiative and run the course in a no-profit-no-loss manner.

In India, ATLS is seen as a way to introduce trauma as a separate discipline, language, and way of thinking. It is an important component of the system aimed to streamline trauma care and systematically integrate trauma into the thinking of physicians of all disciplines. It is particularly relevant to primary healthcare officers, often the first caregivers once the EMS ambulance is activated and the patients are taken to the nearest primary care facility. In a 10-year follow-up of ATLS participants, most felt that the course changed their outlook on what to do with trauma drastically.37 Despite these successes, the ATLS Course, unlike the BLS and ACLS courses, has not been made mandatory by the two bodies controlling standards of postgraduate education in India.

Economics of trauma care in India: public funding, out-of-pocket expenses and insurance

The economic landscape of trauma care in India is a complex mix of public funding, out-of-pocket expenses (OOPE), erratic insurance coverage, and flagship government policies such as the ‘Ayushmaan Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana’ (AB-PMJAY) of the central government and the ‘Nammai Kaakkum 48’ (NK-48) scheme of Tamil Nadu. Public funding in trauma care has experienced gradual enhancements, with the EMS program under NHM being a classic example. Other regional success stories, such as the NK-48 scheme, which provides a fixed coverage of costs for critically injured patients within 48 hours of trauma, serve as a model for other states. Another scheme from Tamil Nadu, the Chief Minister’s Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme, offers coverage for definitive trauma care beyond 48 hours for select injuries, predominantly orthopedics, among other general medical/surgical services.

Nevertheless, despite similar endeavors by different state governments across the country, a glaring disparity persists between demand and supply. A single-center study estimated the mean OOPE for RTI patients at the time of hospitalization to be US$400 (95% CI US$344 to US$456) and for non-RTI patients to be US$369 (95% CI US$313 to US$425).38 Data from the National Representative Health Survey39 revealed that 49.3% of injury-affected households experienced catastrophic health expenditure, with 17.8% falling into poverty and 52.1% using distressed sources due to OOPE for hospitalization. Penetration of personal insurance coverage, which is a cornerstone in shaping the economic landscape of trauma care in any country, is poor. Governmental initiatives like the AB-PMJAY, a flagship healthcare insurance scheme launched by the central government in 2018 geared toward extending healthcare coverage to economically disadvantaged segments, hold promise, yet their implementation and penetration vary among states. Persistent hurdles such as delayed claim settlements and restricted coverage for specialized trauma interventions obstruct the widespread dissemination of these schemes. The limited societal penetration of private insurance schemes adds to the burden of injury-related morbidity among the lower middle class. Also, it acts as a deterrent to private hospitals participating in trauma care.

TAEI: a success story

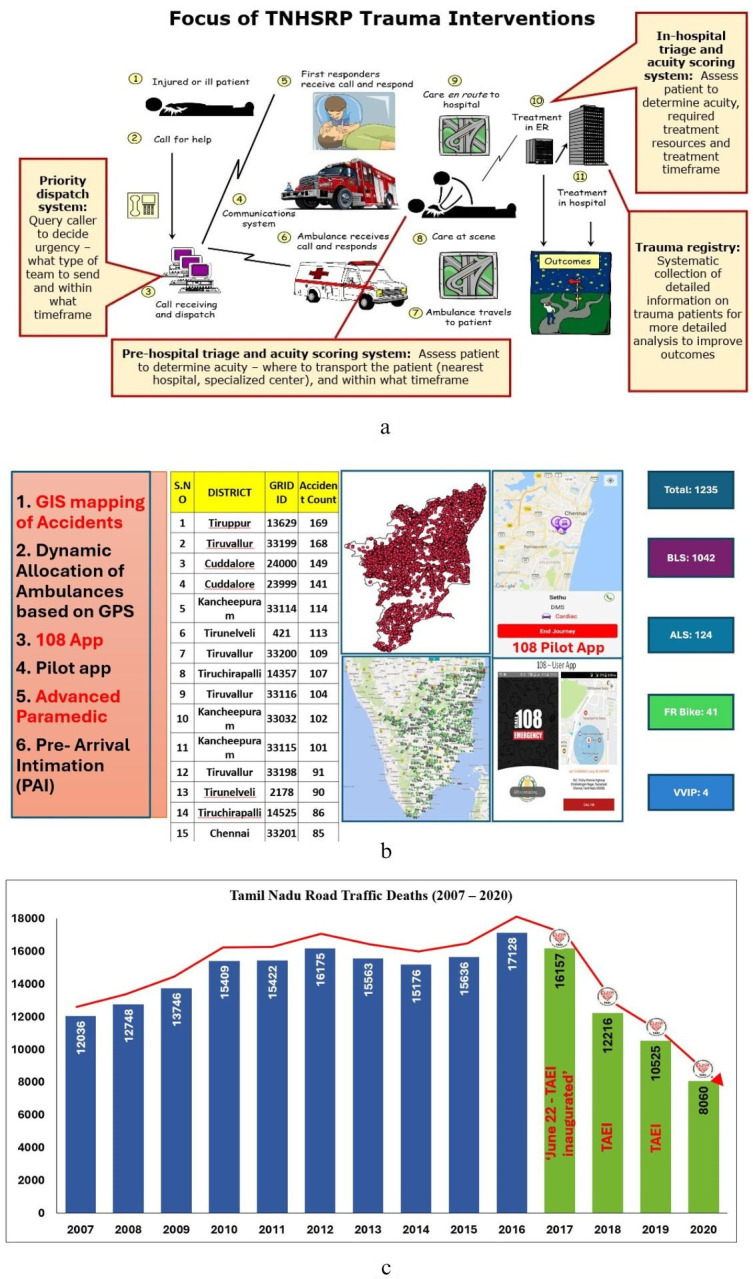

The state of Tamil Nadu in South India has a population of 7.2 crores (72 million) and has one of the highest incidences of RTIs and TBI in the country. The state had consistently seen an increase in road injuries over the years, and in response, the government of Tamil Nadu in 2017 adopted the TAEI program. The program used the existing extensive healthcare system comprising 38 government medical college hospitals and 20 district hospitals in addition to others to attempt to form a regional system (figure 2a,b). The stated main objectives of TAEI include, among others:

Figure 2. (a) Utilization of existing healthcare resources to develop the Tamil Nadu Accident and Emergency Initiative (TAEI) under the Tamil Nadu Health Services Reform Program (TNHSRP). ER- Emergency Room (b) Initial deployment and promulgation of the TAEI program in Tamil Nadu. (c) Data suggestive of reduction in fatalities after initiation of the TAEI program. Picture courtesy: TNHSRP, TAEI and GVK-EMRI.

To attain the State Development Goals—to halve the number of deaths (to 8500 per annum) and injuries from road traffic accidents by 2023.

Standardize management of all emergencies.

Triage and ensure definitive treatment within the golden hour.

To identify and designate TAEI centers based on caseload per location as level 1, level 2, or level 3 centers and emergency stabilization centers in inaccessible routes of emergency ambulance transportation.

This is one of the few statewide trauma systems initiated in India. They were aided by geo-mapping and advanced EMS systems developed by GVK-EMRI (GVK-Emergency Management and Research Institute). With many of the measures instituted, a reduction in mortality was seen, as noted in the publicly available data (figure 2c).40 41 These regionalized trauma and emergency care systems are based on the special environmental assessment of vulnerabilities, disaster-proneness, and unique requirements of the population served, such as inner-city, urban, rural and remote/tribal communities. The long-term implications and continued measurement of the success of TAEI remain to be validated over time.

Discussion

Trauma and emergency systems in India: a SWOT analysis

While trauma is considered a newer specialty in India, there are major strengths in how trauma is conducted, and systematic implementation is possible in India. There are collaborating opportunities, and given that the discipline is relatively new, it offers ample opportunities for system-wide adaptation. Additionally, India has significant capacity-building expertise and structured EMS and ambulance systems.

However, the lack of a centralized system is a major shortcoming. Health is deemed a ‘state’ initiative, opening the potential for differing standards across states (figure 1b). While prehospital care has improved dramatically, it is still uncoordinated due to the lack of a standardized field triage protocol, accredited training program for EMTs, prehospital notification system, and trauma center designation. Despite upcoming trauma educational initiatives nationwide, the demand for organizing fellowships and MS in traumatology is not huge. This remains a major stumbling block in the provision of trauma care throughout the country. Postgraduate training in emergency care is a great initiative. Lack of uniform research facilities across the country, fewer quality improvement programs, and very few rehabilitation centers remain major threats to implementing a countrywide system that must accommodate the threats of a growing population, urbanization, and industrialization (figure 3).

Figure 3. SWOT analysis of trauma care in India. SWOT, strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

What can be done now? Establishing a trauma system statewide and integration with a national governing authority are the first steps (table 3). Currently, no organization oversees trauma center designation, accreditation, and verification. For example, the Committee on Trauma of the American College of Surgeons incorporates advocacy, education, trauma center and trauma system resources, best practice creation, outcome assessment, and continuous quality improvement initiatives. India could come up with its own verification organization building on these principles. The Directorate General of Health Services under the MoH has formulated infrastructure and manpower guidelines for developing trauma care facilities along national highways.42 The Operational Guidelines for the Management of Common Emergencies, Burns, and Trauma at the Primary Care Level, the Operational and Technical Guidelines on Emergency Services at the District Hospital, and the Guidelines for Operation Theatres are in place and being followed. Besides, focusing on emergency care services yields impactful improvements in health outcomes with simple, low-cost interventions, such as reorientation of existing systems, frameworks, resources, and processes. Second, resource allocation and training for the next generation of surgeons, nurses, and other practice providers in trauma is urgently needed. In this regard, the growth of ATLS and the Advanced Trauma Care for Nurses (ATCN) programs in India is an encouraging sign. Similarly, postgraduate training in emergency care is another successful initiative. Starting in 2009, more than 345 postgraduate emergency medicine (MD/DNB) seats are available in more than 46 government medical colleges and other academic institutions. The economics of trauma care needs a long-term solution. Increasing the free-of-cost/subsidized healthcare coverage provided by the government while improving insurance coverage among the general public may be the long-term solution. Finally, an emphasis on rehabilitation after trauma and teaching basic research methodologies among clinicians have the potential to develop local, economical solutions to improve the care of critically injured trauma patients.

Table 3. What can be done? The first steps.

| Categories | Specifics |

|---|---|

| Develop standards and coordinating authority. | Establish Indian committee on trauma (similar to American college of surgeons-committee on trauma).Establish statewide trauma systems. |

| Provide resources for prehospital care with better communication. | Establish coordination between prehospital and hospital care in the government sector and public hospitals (TAEI as an example).Improve coordination within tiered care (levels I–IV). |

| Education and workforce | Establish more trauma programs at medical schools.Establish a multi-disciplinary critical care program.Increase ATLS education—make it mandatory for all physicians—including in rural areas.Train more EMTs and paramedical staff in trauma (Take GVKEMRI as an example).Train more specialty nursing in trauma (ATCN). |

| Postinjury and rehabilitation | Establish physical medicine and rehabilitation programs at medical schools.Establish a multidisciplinary rehab program for TBI/spinal cord injury.Train more physical therapists.Train occupational therapists to integrate patients back into society. |

ATCN, Advanced Trauma Care for Nurses; ATLS, Advanced Trauma Life Support; ETN, emergency medical technician; TAEI, Tamil Nadu Accident and Emergency Care Initiative; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

This review has its limitations. The paucity of literature on multiple aspects of trauma care meant that much of the evaluation was done by experts involved in various facets of trauma care. A targeted literature search and the usage of gray literature, while unavoidable, may not give the best representation of the current burden. We postulated that having a published review will serve as a platform for future discussion with the governmental agencies and may lead to necessary improvements in trauma care rendered throughout India.

Conclusions

Trauma care in India, much like the nation itself, is characterized by a diverse array of stakeholders striving to reduce the burden of injuries and enhance the quality of care. As the country with the world’s largest youth population, the loss of life and disability due to trauma poses a significant challenge to its aspirations of becoming a global economic powerhouse. A unified, systematic approach that integrates all facets of trauma care—including cost-effectiveness—while concurrently advancing quality improvement, research, and education is essential for addressing this critical public health issue.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the EMTs and others involved with prehospital care for their tireless work and unbridled enthusiasm in providing care to the neediest at critical time points following trauma.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: Not Applicable.

References

- 1.RA_2022_30_Oct.pdf. https://morth.nic.in/sites/default/files/RA_2022_30_Oct.pdf Available.

- 2.IRF world road safety dashboard-public. 2024. https://agilysis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/3fed15af97c443acb53277ef95be6e36 Available.

- 3.Behera DK, Singh SK, Choudhury DK. The burden of transport injury and risk factors in India from 1990 to 2019: evidence from the global burden of disease study. Arch Public Health. 2022;80:204. doi: 10.1186/s13690-022-00962-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prachi Salve I com & GN Why India’s data on road crash deaths is unreliable. 2021. https://scroll.in/article/1007963/why-indias-data-on-road-crash-deaths-is-unreliable Available.

- 5.Menon GR, Singh L, Sharma P, Yadav P, Sharma S, Kalaskar S, Singh H, Adinarayanan S, Joshua V, Kulothungan V, et al. National Burden Estimates of healthy life lost in India, 2017: an analysis using direct mortality data and indirect disability data. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e1675–84. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global health estimates. 2024. https://www.who.int/data/global-health-estimates Available.

- 8.Kumar A, Lalwani S, Agrawal D, Rautji R, Dogra T. Fatal road traffic accidents and their relationship with head injuries: An epidemiological survey of five years. Indian J Neurotrauma. 2008;05:63–7. doi: 10.1016/S0973-0508(08)80002-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal D, Ahmed S, Khan S, Gupta D, Sinha S, Satyarthee GD. Outcome in 2068 patients of head injury: Experience at a level 1 trauma centre in India. Asian J Neurosurg. 2016;11:143–5. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.145081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Neurological Disorders Collaborators The burden of neurological disorders across the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e1129–44. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00164-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Professionals working under physiotherapy and occupational therapy. 2024. https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=108358 Available.

- 12.Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India National road safety policy. 2024. https://morth.nic.in/national-road-safety-policy-1 Available.

- 13.Groeger JA. In: Handbook of traffic psychology. Porter BE, editor. Academic Press; San Diego: 2011. Chapter 1 - How Many E’s in Road Safety? pp. 3–12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Notification_dated_21.01.2016_regarding_Good_Samaritan.pdf. https://morth.nic.in/sites/default/files/circulars_document/Notification_dated_21.01.2016_regarding_Good_Samaritan.pdf Available.

- 15.MV Act English.pdf. https://morth.nic.in/sites/default/files/notifications_document/MV%20Act%20English.pdf Available.

- 16.National health mission ERS/patient transport service. 2024. https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=1217&lid=189 Available.

- 17.227201553254PMAIS-125_Part_2_F.pdf. https://hmr.araiindia.com/Control/AIS/227201553254PMAIS-125_Part_2_F.pdf Available.

- 18.AIIMS_STUDY_1.pdf. https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2021-12/AIIMS_STUDY_1.pdf Available.

- 19.Newberry JA, Bills CB, Matheson L, Zhang X, Gimkala A, Ramana Rao GV, Janagama SR, Mahadevan SV, Strehlow MC. A profile of traumatic injury in the prehospital setting in India: A prospective observational study across seven states. Injury. 2020;51:286–93. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2019.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel V, Parikh R, Nandraj S, Balasubramaniam P, Narayan K, Paul VK, Kumar AKS, Chatterjee M, Reddy KS. Assuring health coverage for all in India. The Lancet. 2015;386:2422–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.JEMS: EMS, Emergency Medical Services - Training, Paramedic,EMT News Emergence of EMS in India. 2017. https://www.jems.com/international/emergence-of-ems-in-india/ Available.

- 22.Ramachandra G, Ramana Rao GV, Tetali S, Karabu D, Kanagala M, Puppala S, Janumpally R, Rajanarsing Rao HV, Carr B, Brooks SC, et al. Active bleeding control pilot program in India: Simulation training of the community to stop the bleed and save lives from Road Traffic Injuries. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;11:100729. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brief- National Programme for Prevention & Management of Trauma & Burn Injuries.pdf. https://dghs.gov.in/WriteReadData/userfiles/file/Trauma%20Care/Brief-%20National%20Programme%20for%20Prevention%20&%20Management%20of%20Trauma%20&%20Burn%20Injuries.pdf Available.

- 24.AITSC+inaugural+report_low+res.pdf. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b761ed3f93fd491065f7839/t/5c787bb0e4966bc9454b8d7f/1551399905619/AITSC+inaugural+report_low+res.pdf Available.

- 25.Misra P, Majumdar A, Misra MC, Kant S, Gupta SK, Gupta A, Kumar S. Epidemiological Study of Patients of Road Traffic Injuries Attending Emergency Department of a Trauma Center in New Delhi. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2017;21:678–83. doi: 10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_197_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy N, Gerdin M, Ghosh S, Gupta A, Kumar V, Khajanchi M, Schneider EB, Gruen R, Tomson G, von Schreeb J. 30-Day In-hospital Trauma Mortality in Four Urban University Hospitals Using an Indian Trauma Registry. World J Surg. 2016;40:1299–307. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3452-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roy N, Kizhakke Veetil D, Khajanchi MU, Kumar V, Solomon H, Kamble J, Basak D, Tomson G, von Schreeb J. Learning from 2523 trauma deaths in India- opportunities to prevent in-hospital deaths. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:142. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2085-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.G.O.575.pdf. https://tnhsp.org/tnhsrp/images/files/go/G.O.575.pdf Available.

- 29.Login page. 2024. https://taei.co.in/ Available.

- 30.O’Reilly GM, Gabbe B, Braaf S, Cameron PA. An interview of trauma registry custodians to determine lessons learnt. Injury. 2016;47:116–24. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenkrantz L, Schuurman N, Arenas C, Jimenez MF, Hameed MS. Understanding the barriers and facilitators to trauma registry development in resource-constrained settings: A survey of trauma registry stewards and researchers. Injury. 2021;52:2215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2021.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joshipura MK, Shah HS, Patel PR, Divatia PA, Desai PM. Trauma care systems in India. Injury. 2003;34:686–92. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(03)00163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar S. Trauma and Emergency Surgery—a Career with Passion. Indian J Surg. 2021;83:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s12262-021-02940-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.FNB-Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2021.pdf. https://nbe.edu.in/mainpdf/curriculum/FNB-Trauma%20and%20Acute%20Care%20Surgery%202021.pdf Available.

- 35.MS-Traumatology-surgery.pdf. https://www.nmc.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/MS-Traumatology-surgery.pdf Available.

- 36.The Times of India; 2023. New course in trauma surgery & critical care begins at AIIMS-P.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/patna/new-course-in-trauma-surgery-critical-care-begins-at-aiims-p/articleshow/102186107.cms Available. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rattan A, Gupta A, Kumar S, Sagar S, Sangi S, Bannerjee N, Nambiar R, Jain V, Ravi P, Misra MC. Does ATLS Training Work? 10-Year Follow-Up of ATLS India Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prinja S, Jagnoor J, Chauhan AS, Aggarwal S, Ivers R. Estimation of the economic burden of injury in north India: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2015;385:S57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60852-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nanda M, Sharma R. Financial burden of injury care in India: evidence from a nationally representative sample survey. J Public Health (Berl) 2025;33:127–39. doi: 10.1007/s10389-023-01981-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sengodan VC, Sivagnanam M, Kandasamy K. Impact of Tamil Nadu accident and emergency care initiative (TAEI) programme on orthopaedic emergency fixation: Lesson from Coimbatore for low income countries. Int J Orthop Sci. 2020;6:480–6. doi: 10.22271/ortho.2020.v6.i1i.1911. http://www.orthopaper.com/archives/?year=2020&vol=6&issue=1 Available. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.pdfpage_tn_6cZSIgn_2023_08_04.pdf. 2024 https://tnsta.gov.in/pdfpage/pdfpage_tn_6cZSIgn_2023_08_04.pdf Available.

- 42.Operational_Guidelines_Trauma.pdf. https://dghs.gov.in/WriteReadData/userfiles/file/Operational_Guidelines_Trauma.pdf Available.

- 43.Kagan RJ, Baker RJ. The impact of the volume of neurotrauma experience on mortality after head injury. Am Surg. 1994;60:394–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fakhry SM, Trask AL, Waller MA, Watts DD, IRTC Neurotrauma Task Force Management of brain-injured patients by an evidence-based medicine protocol improves outcomes and decreases hospital charges. J Trauma. 2004;56:492–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000115650.07193.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Udekwu P, Kromhout-Schiro S, Vaslef S, Baker C, Oller D. Glasgow Coma Scale Score, Mortality, and Functional Outcome in Head-Injured Patients. J Trauma. 2004;56:1084–9. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000124283.02605.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Silva MJ, Roberts I, Perel P, Edwards P, Kenward MG, Fernandes J, Shakur H, Patel V, CRASH Trial Collaborators Patient outcome after traumatic brain injury in high-, middle- and low-income countries: analysis of data on 8927 patients in 46 countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:452–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]