Abstract

IWS1 is a key assembly factor of the RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) elongation complex, and its overexpression is associated with worse outcomes in patients with liposarcoma (LPS). This study aimed to identify compounds that can disrupt the IWS1/Spt6 interaction and assess their biological effects in dedifferentiated LPS (DDLPS). Using the AlphaFold-predicted structure of IWS1, we identified a core binding region (AA 545–694) for its interaction with Spt6. Through molecular modeling and virtual screening, Ketotifen and Desloratadine were predicted as candidate inhibitors. Both were predicted to mimic Spt6 phenylalanine (F217) and disrupt the complex, which was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation. Functional assays showed that treatment with either compound reduced migration, invasion, and spheroid formation in DDLPS cell lines. Additionally, increased nuclear localization of IWS1 was observed. These findings suggest Ketotifen and Desloratadine as promising inhibitors of the IWS1/Spt6 interaction, with potential applications in reducing the invasive properties of human LPS.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-07215-y.

Subject terms: Sarcoma, Virtual screening, Cell invasion, Collective cell migration

Introduction

Liposarcoma (LPS) is a malignant adipocytic tumor that constitutes 20% of soft tissue sarcomas and 30% of retroperitoneal sarcomas1,2. There are 5 subtypes of LPS, with dedifferentiated LPS (DDLPS) representing the most aggressive subtype2,3. DDLPS has a 5-year overall survival rate of 60-70%, along with a metastatic occurrence rate ranging between 10 and 20%1,4. Surgical resection remains the only curative approach to DDLPS, and the use of adjuncts like radiotherapy and chemotherapy remain controversial for patients with resectable disease5–7. For patients with advanced disease, first-line treatment is doxorubicin and its combination with alkylating agents8,9. While other systemic therapies including antimetabolites, anti-microtubules, tyrosine-kinase inhibitors, and immunotherapy have been tested in patients with metastatic and recurrent LPS, their efficacy is limited and there has been no significant improvement in survival in nearly 30 years7. Genotypically, DDLPS is characterized by the amplification of chromosome region 12q13-15, particularly high level amplification of MDM2 (12q15) and CDK4 (12q14.1)3,10,11but it is still unclear if targeting the p53-MDM2 pathway will be sufficient to improve patient outcomes12. To this end, novel targets to treat DDLPS represent a significant unmet clinical need.

In our previous work, we reported that upregulation of IWS1 is associated with the reduction in overall survival and worse disease-specific survival and an increase in the number of recurrences in patients with DDLPS13. Taken together, these findings suggest IWS1 may be an important target to treat patients with DDLPS. Yet, the mechanism by which IWS1 increases DDLPS progression and whether it can be targeted therapeutically is unknown.

IWS1 is a protein located in the cell nucleus and is an central component of the RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) elongation complex during transcription14. The complete form of the human IWS1 protein has 819 residues, with a highly conserved central domain of amino acid (AA) residues 583–695. This conserved domain is the main, structured component of IWS1, while the remaining domains of IWS1 are largely unstructured15. The dense population of acidic residues in the N-terminal unstructured portion may contribute to potential interaction with histones and downstream DNAs. Whereas the structured domain of IWS1 interacts with a catalytic unit of RNAPII and mulitple transcription factors, IWS1 is best known to bind Spt616, which is a positive transcription elongation factor and a histone chaperone that is important for genome stability17. The association of IWS1 and Spt6 is important for the export and splicing of mRNA16,18. Mutations in either IWS1 or Spt6 that disrupt the formation of the IWS1/Spt6 complex result in impaired growth rates of yeast cells19. The IWS1/Spt6 interface is contained within the conserved, structured domain. This interface features the shape complementarity between a conserved and solvent-exposed phenylalanine residue, F217 (F249 in yeast) in Spt6 and a concave-shaped, generally hydrophobic binding site in IWS120. This well-defined and immutable protein-protein interaction surface provides a promising target to develop therapeutics that disrupt the functional interaction of IWS1/Spt6.

The rationale for finding a potent ligand to inhibit the formation of the IWS1/Spt6 complex is to suppress the growth, migration, and invasion of cancer cells. The aim of this study was to identify lead structures from virtual screening that can disrupt the IWS1/Spt6 complex. Using molecular docking, we were able to identify several classes of FDA-approved drugs to be repurposed as inhibitors of the IWS1/Spt6 complex formation. Among the top-ranked ligands from the prediction, Ketotifen and Desloratadine were selected for experimental validation. Ketotifen and Desloratadine are two antihistamines with structural similarities. They both have an isolated piperidine ring with a basic nitrogen as well as a bulky three-ring-fused backbone. The side aromatic rings add the rigidity of the scaffold, while the central seven-membered ring introduces a bent overall shape with some flexibility. Herein, we show that both compounds disrupt IWS1/Spt6 complex, reduce migration and invasion ability of DDLPS cells, and significantly decrease spheroid growth rate in vitro. When Ketotifen and Desloratadine were used at the working concentrations determined in this study, neither drug affected cell viability while mitigating the aggressive behavior of DDLPS cell lines.

Results

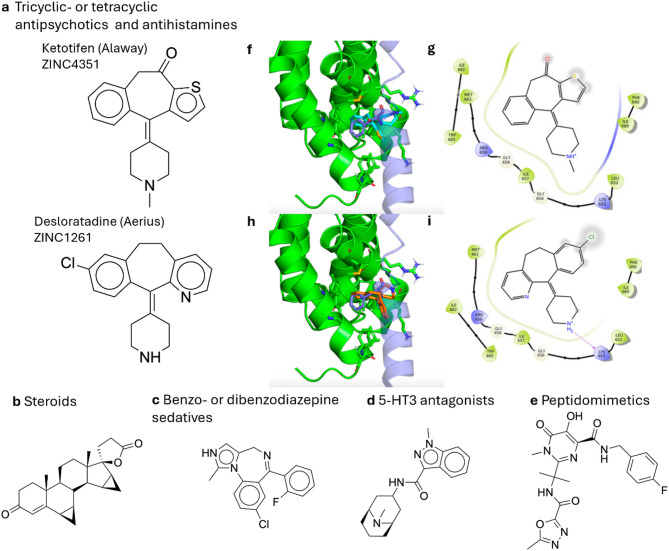

The major categories of lead structures discovered from the preliminary virtual screening

From the preliminary virtual screening of 1,605 unique ligands, 1,604 valid-docked poses were obtained within the grid box of the precomputed receptor affinity maps. To discover the inherent structures that are common in the top-rated ligands, a global filter using a cutoff molecular weight of 500 Da was applied based on Lipinski’s Rule of Five. The remaining 1426 ligands were included in subsequent analysis. Due to the nonlinear scaling in the total scores and the wide presence of chlorine and sulfur in the ligand dataset, ligands were ranked by total scores under the modified scoring function instead of binding efficiency. In addition, since the FDA-approved ligands do not uniformly populate the chemical space, representative lead structures from the top-rated ligands were categorized with respect to their chemical structures and usage (Fig. 1a-e). These include the following major categories: (1) Tricyclic- or tetracyclic antipsychotics and antihistamines (Fig. 1a), which contain inherent core structures found in Ketotifen and Desloratadine. (2) Steroids (Fig. 1b), which resemble hormones and their ability to permeate the nuclear membrane where IWS1 is located. (3) Benzo- or dibenzodiazepine sedatives (Fig. 1c) that contain similar puckered ring structures and a diazepine core important for P450-mediated metabolic hydrolysis21. These compounds exhibit a unique ring opening that occurs through hydrolysis of the imine in an acidic but physiologically relevant environment22. (4) 5-HT3 antagonists (Fig. 1d), which are used to suppress gastrointestinal (GI) side effects like nausea and vomiting that can occur from other types of systemic cancer therapies23. (5) Peptidomimetics (Fig. 1e) that can spontaneously fold into a similar build as Spt6, and thus competitively disrupt the binding of Spt6 and IWS1.

Fig. 1.

Representative compounds of specified drug classes (a–e) that were ranked by the predicted binding affinity as the top 5% (approximately the 80 ligands with the best 80 Vina docking scores) in the preliminary virtual screening. (f–i) The predicted binding modes and the protein-ligand interaction diagrams of Ketotifen and Desloratadine. In the 3D structures, the protein receptor IWS1 is colored green. The assumed position of Spt6 in the IWS1/Spt6 is generated by aligning the receptor structure and IWS1 in a known experimental structure of the IWS1/Spt6 complex (PDB ID: 2XPO). Spt6 is colored in blue and the conserved, to-be-replaced phenylalanine residue of Spt6 is shown in the licorice drawing style as it overlaps with docked ligands. (f) The 3D structure of the top-scored pose of Ketotifen which is colored cyan. (g) The protein-ligand interaction diagram for the top-scored pose of Ketotifen. (h) The 3D structure of the top-scored pose of Desloratadine which is colored red. (i) The protein-ligand interaction diagram for the top-scored pose of Desloratadine.

Based on the inherent core structures of the top-ranked ligands, the intrinsic geometric features of the IWS1 protein receptor, and the shape complementarity with its native binding partner Spt620, we posit that a potent competitive inhibitor would be a wedge-shaped, spirocyclic, or puckered polycyclic compound. In addition, the ideal compound would also contain a small aromatic headgroup to mimic the phenylalanine residue of Spt6 to complement the evolutionary conserved binding site on IWS1. This hypothesis was derived from the findings that this scaffold stands out from the 5% top-scored ligands and is therefore based on shape complementarity, which is crucial to the predicted binding affinities. The finding indicates that there are many FDA-approved drugs with this scaffold that may be of interest for further testing, providing easily accessible options for further experiments with well-established drug profiles, including solubility and toxicity. However, it does not imply that this scaffold is superior to other scaffolds that are potential fits for the binding pocket. For initial selection of compounds for biological validation, we avoided controlled substances and compounds that were not commercially available. The predicted binding modes of Ketotifen and Desloratadine, the two experimentally validated hits in this work, are displayed in overlay with the supposed position of Spt6 in the IWS1/Spt6 complex (Fig. 1f–i).

From the predicted binding poses, the residues of IWS1 that interact with Ketotifen and Desloratadine are mostly nonpolar and include L652, G658, M662, I682, and W685. Interestingly, these are all complementary to the phenylalanine residue of Spt6 (F217). In the top-ranked poses, Ketotifen fills the cavity with the phenyl ring, while Desloratadine does it with the unsubstituted pyridinyl substructure. Additionally, in the top-ranked pose of Desloratadine, the protonated piperidine nitrogen forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of K653. This interaction aligns with the predicted properties of the binding pocket, where the polar and charged groups, such as the piperidine, are favored near solvent-accessible residues like K653 and R659.

Biological validation

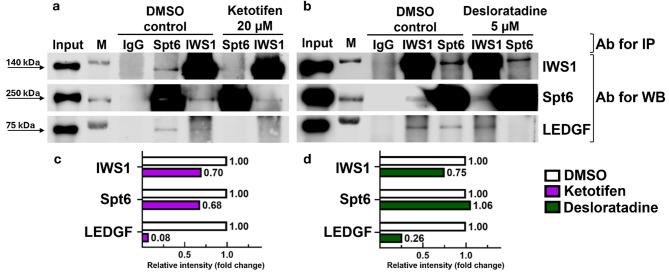

Disruption of IWS1/Spt6 complex

To test the interaction of Ketotifen and Desloratadine with IWS1 and other factors of the RNAPII assembly complex, co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) was performed. After a 48-hour treatment of cells with Ketotifen at a concentration of 20 µM, the complex of IWS1 with its bound proteins (including the binding partner of our interest Spt6) was pulled down. As shown in Fig. 2, the amount of precipitated complex was decreased substantially when treated with Ketotifen (Fig. 2a, c). This result was obtained using both IWS1 and Spt6 antibodies in separate immunoprecipitation reactions to eliminate the variability in the efficiency of the antibodies used for the complex precipitation. Regardless of which antibody was used to pull down the complex, the reduction in complex formation in the presence of Ketotifen was observed. Similarly, the treatment with Desloratadine at a concentration of 5 µM for 48 h caused a reduction in the amount of the precipitated complex (Fig. 2b, d). Notably, we also probed the immunoprecipitated complex with an antibody that binds LEDGF, a known component of RNAPII complex that binds IWS124. We found that both Ketotifen and Desloratadine treatments reduced the IWS1/LEDGF complex formation. Taken together, these results suggested that the identified compounds were capable of disrupting physical interactions between IWS1 and Spt6.

Fig. 2.

Co-Immunoprecipitation assays showing disruption of IWS1/Spt6 complex after 48-hour treatment with 20 µM Ketotifen (a) or 5 µM Desloratadine (b) and respective quantified data (c,d). IgG isotype control, M marker, Ab antibody. Western blot images are representatives of two (n = 2) independent experiments. Bar diagrams presented in (c,d) represent the densitometry-based quantification of bands obtained in the western blot representative experiment presented in (a,b). Protein extracts (Input) were immunoprecipitated with IWS1 (column IWS1) or Spt6 (column Spt6) antibody and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Protein-protein interactions were immunodetected using IWS1, Spt6, and LEDGF antibodies. Since samples immunoprecipitated with IWS1 or Spt6 antibodies were subsequently immunodetected with Spt6 and IWS1 antibodies, overexposure naturally occurred for samples immunoprecipitated and immunodetected with the antibody against the same protein representing both the protein in the complex as well as free protein. Samples immunoprecipitated with IWS1 antibody and immunodetected with Spt6 antibody (or immunoprecipitated with Spt6 antibody and immunodetected with IWS1 antibody) demonstrate the protein in the complex only. The blots were cropped for the presentation of target bands, and the original blots with multiple exposures are presented in Supplementary data (Figure S7).

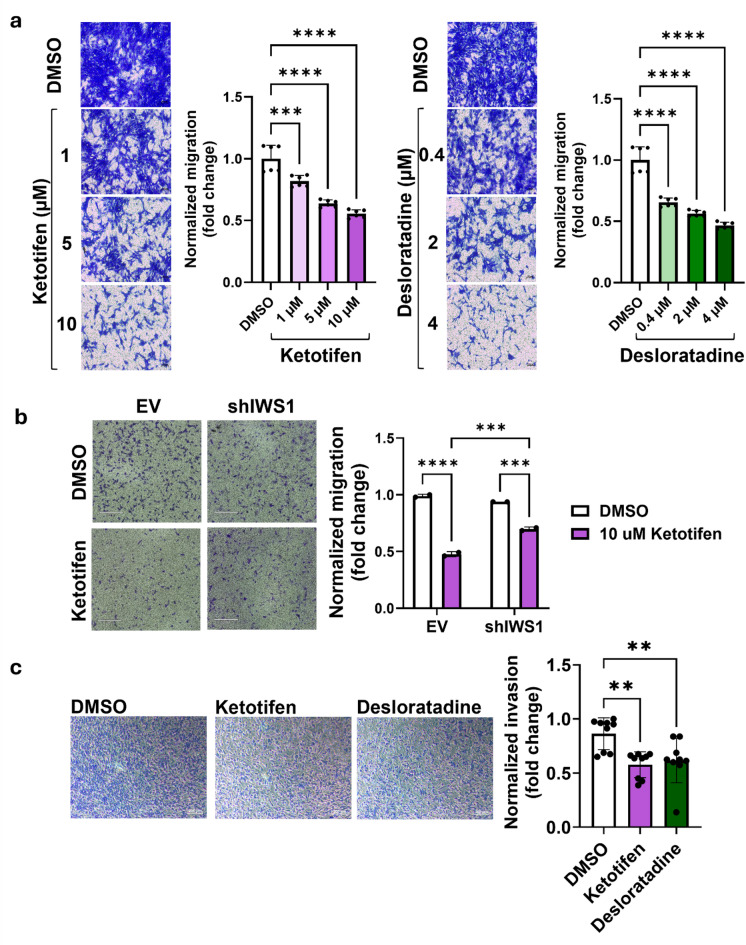

Suppression of migration and invasion

To determine the working range of drug concentrations when cell viability is not affected but IWS1 inhibition effect on cells may have reached the saturation point, we performed a cell viability assay on a DDLPS cell line Lipo863, which showed IC50 concentration of 63 µM and 14 µM for Ketotifen and Desloratadine, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Importantly, the IC50 values for the compounds tested on a non-cancer fibroblast cell line NIH/3T3 were also in the micromolar range (84 µM and 19 µM when treated with Ketotifen and Desloratadine, respectively), demonstrating a low off-target cytotoxicity of drugs (Supplementary Fig. S1b). Since IC50 values for both the DDLPS cell line and fibroblast cell line are in the same range, cell death caused by Ketotifen and Desloratadine does not seem to be cancer-specific.

Previously, we have shown that LPS cells with IWS1 knockdown demonstrate less migratory ability and invasiveness in vitro and form a smaller number of lung nodules in vivo13. To test if treatment with Ketotifen and Desloratadine leads to the previously observed phenotype due to pharmacological inhibition of IWS1, we carried out transwell migration and invasion assays. Migration of the DDLPS cell line, Lipo863, was significantly reduced when cells were treated with either Ketotifen or Desloratadine. Moreover, this effect was dose-dependent: 1, 5 and 10 µM solutions of Ketotifen decreased migration ability by 18, 36 and 44% (p = 0.0002, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001); 0.4, 2 and 4 µM Desloratadine by 34, 44 and 53% (all three p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3a). To determine if the Ketotifen effect on ability of cells to migrate depends on the cellular expression of IWS1, we used IWS1 knockdown cells (shIWS1) to compare the effect of Ketotifen on cells with and without IWS1 expression13. While decreasing the migratory ability of control cells (EV) by 52% (p < 0.0001), the Ketotifen treatment affected migration of the IWS1 knockdown cells (shIWS1) only by 30% (p = 0.0001) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Drug effect on cell migration and invasion. (a) Dose-dependent decrease in migratory ability of Lipo863 cells after 48-hour treatment with Ketotifen and Desloratadine. Scale bar: 100 μm. (b) Decrease in migratory ability of shIWS1 cells and EV (non-target shRNA control) of Lipo863 cell line after 24-hour treatment with 10 µM Ketotifen. Scale bar: 530 μm. (c) Drug effect on cell invasion. Decrease in invasion of Lipo246 cell line after 48-hour treatment with 20 µM Ketotifen or 4 µM Desloratadine. Scale bar: 200 μm. Cells were treated with drugs for 48 h prior to 24-hour transwell migration or invasion assays. One-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (a, c) or two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (b) was applied. The normalized migration of cells is displayed as mean, each error bar represents the standard deviation (SD) from the mean value from two (n = 2) (a, b) or three (n = 3) (c) biological replicates, each biological replicate is presented as three black dots representing technical replicates. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Invasiveness is another important parameter used to characterize the aggressive behavior of cancer cells. To test the effect of Ketotifen and Desloratadine on the invasiveness of cells, we used the invasive DDLPS cell line Lipo246, as compared to the invasion ability of DDLPS cells in our lab (data not shown). After incubating cells with 20 µM Ketotifen and 4 µM Desloratadine for 48 h, we observed a significant decrease in invasion ability of Lipo246 cells by 30% and 25%, respectively (p = 0.0018, p = 0.006) (Fig. 3c). Thus, these results suggested both compounds inhibit cancer cell migration and invasion in an IWS1 dependent manner.

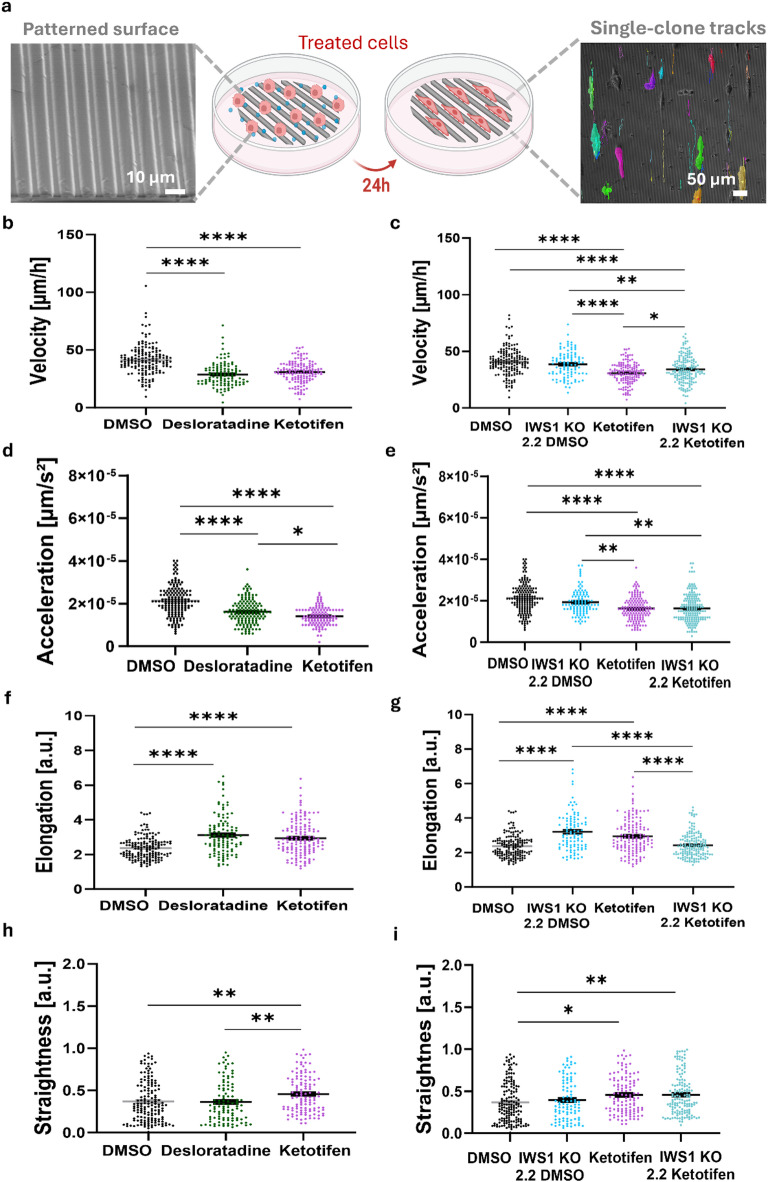

The ability of cancer cells to invade surrounding tissues is central to metastasis, and analyzing migration properties such as elongation, velocity, acceleration, and straightness, provides valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying their invasive behavior25. For that, various in vitro systems have been developed to study directional tumor cell migration guided by structural cues26–29. To mimic these structures, we utilized line-patterned surfaces that simulate the structural cues encountered by tumor cells during dissemination, enabling directed cell migration along the patterns for evaluating motility behaviors.

Cell migration was assessed by seeding 7.5 × 103 Lipo863 cells on textured Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) surfaces in regular culture medium, followed by treatment with 20 µM Ketotifen or 4 µM Desloratadine for 24 h and time-lapse imaging every 10 min over a 16-hour period (Supplementary video 1–6). To quantify the migratory behavior (e.g., velocity, acceleration, elongation, and straightness) at the single-cell level, we performed automated cell tracking, by analyzing segmented images (Fig. 4a) produced through supervised learning with the Nikon NIS.AI software. The results demonstrated that cells treated with Ketotifen and Desloratadine have reduced migratory velocities, ranging between 28 and 31 μm/h, corresponding to velocity reductions of 23% and 30%, respectively, when compared to DMSO-treated cells (both p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4b). To test whether the effects of drug treatment depend on presence of IWS1, we generated IWS1 knockout (IWS1 KO) clones using CRISPR-Cas9 and compared Ketotifen treatment effect on parental cells versus IWS1 KO group (Fig. 4c, e, g, i). Notably, when treating parental cells with Ketotifen, velocity has decreased by 23%, while treatment of IWS1 KO cells caused a reduction in velocity by only 16% when compared to DMSO-treated cells (both p < 0.0001) suggesting an IWS1-dependent nature of velocity reduction (Fig. 4c). Moreover, Ketotifen-treated parental cells exhibited the lowest velocity among all groups, including IWS1 KO cells treated with Ketotifen (p = 0.0453). In support of these findings, acceleration was also significantly reduced in Ketotifen and Desloratadine-treated cells by 24% and 34% respectively compared to DMSO (both p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4d). Similar to velocity, trends were observed in the acceleration data across all groups of IWS1 KO cells (Fig. 4e). Taken together these results suggest that while IWS1 contributes to the effects of Ketotifen on migration, part of the reduction in velocity and acceleration may be due to off-target effects.

Fig. 4.

Lipo863 cells exhibit reduced invasiveness in response to drug treatment on aligned structural cues. (a) SEM micrograph of the PDMS-patterned surface designed to influence cell behavior upon drug treatment, showing cell alignment along the patterned surface after 24 h. Single cells were tracked, and their motility parameters were quantified from their migration patterns. Quantification of (b-c) velocity, (d-e) acceleration, (f-g) elongation, and (h-i) straightness, demonstrates a reduction in velocity and acceleration, along with increased elongation and directional persistence (straightness), suggesting a lower motility rate of the drug-treated cells on aligned surfaces. (n = ~ 200). All error bars are shown as SEM *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001, One-way ANOVA was applied followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for post hoc analysis.

When measuring the elongation of the cells migrating on the patterned surfaces, Ketotifen and Desloratadine-treated cells had a higher elongation rate compared to DMSO-treated cells (both p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4f). Moreover, both IWS1 KO cells treated with DMSO and parental cells treated with Ketotifen showed similar trends with increased elongation compared to DMSO-treated parental cells (both p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4g). IWS1 KO cells treated with Ketotifen did not demonstrate higher elongation compared to parental cells treated with Ketotifen. While the addition of Ketotifen did reduce elongation in IWS1 KO cells compared to IWS1 KO treated with DMSO (p < 0.0001), these results suggest that the effect of Ketotifen is, in part, dependent on IWS1 and not entirely a result of off-target effects.

Finally, we quantified the directional movement of the cells in our analysis by straightness, which reflects the cell’s ability to maintain a consistent trajectory along a single axis throughout the entire experiment, and the absence of any chemotactic cues. Both parental and IWS1 KO cells treated with Ketotifen present a higher straightness compared to the DMSO group (p = 0.0057, p = 0.0064), suggesting this phenomenon is independent of IWS1(Fig. 4h, i) like velocity and acceleration. No changes in cells straightness were observed following Desloratadine treatments (Fig. 4h).

Reduction in spheroid formation

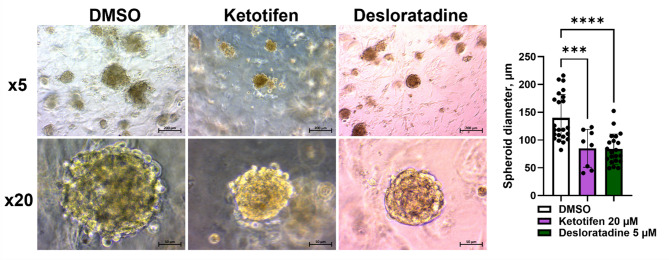

Three-dimensional culture systems more accurately mimic tissue-like structures and in vivo drug responses, and are commonly used in preclinical studies to model drug concentration gradients and assess efficacy30–32. We evaluated the impact of the treatment on spheroid formation by growing spheroids in the presence of 20 µM Ketotifen or 5 µM Desloratadine. While spheroids formed in both treated and DMSO control groups, their number and size of spheroids were significantly reduced. Specifically, spheroid diameter decreased from 140 μm in DMSO-treated to 54 and 55 μm with Ketotifen or Desloratadine, corresponding to reduction of 61 and 60%, respectively (p = 0.001, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Representative microscopic images of spheroids of Lipo863 cells after 14-day treatment with 20 µM Ketotifen and 5 µM Desloratadine. Spheroids in treatment groups are characterized by smaller diameter. Microscopic images are representatives of two (n = 2) independent experiments with Lipo863 cell line. Additionally, two (n = 2) independent experiments were conducted with Lipo224 cell line, and the results are presented in Supplementary data (Figure S6). One-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons was applied. Bar diagram represents the mean of spheroid diameter from one experiment, each black dot represents one spheroid. Each error bar represents the standard deviation (SD) from the mean value. Scale bar: 200 μm in images with x5 magnification and 50 μm in images with x20 magnification. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

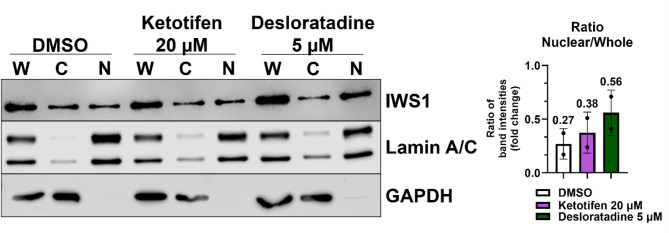

Drug effect on IWS1 cell distribution

Cells often compensate the drug effect by upregulating the targeted protein33. Furthermore, the inhibited protein bound to a small molecule can change intracellular localization, distribution, and utilization of the protein34. To test if Ketotifen or Desloratadine affected the location of IWS1 within the nucleus, we isolated nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions from drug-treated cells and analyzed IWS1 expression by Western blot. The fraction analysis revealed that the ratio of IWS1 expression between the nuclear fraction and whole cell lysate increased by 41% for 20 µM Ketotifen and by 107% for 5 µM Desloratadine as compared to DMSO (Fig. 6), suggesting the compound treatments led to more nucleus accumulation of IWS1.

Fig. 6.

Separation of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins of Lipo863 cells after 48-hour treatment with 20 µM Ketotifen and 5 µM Desloratadine. Subcellular fractions are abbreviated as W for whole cell lysate, C for cytoplasmic fraction and N for nuclear fraction. The upper panel shows immunoblotting results for IWS1, the middle panel for nuclear marker Lamin A/C, and the lower panel for cytoplasmic marker GAPDH. The ratio of nuclear fraction to whole cell lysate of IWS1 expression was increased by 0.38 for 20 µM Ketotifen and by 0.56 for 5 µM Desloratadine compared to DMSO with a ratio of 0.27. Western blot image is a representative of two (n = 2) independent experiments. Western blot bands presented in the figure were quantified by densitometry, and the ratio of nuclear fraction (N) to whole cell lysate (W) was calculated and presented in the bar. The Nuclear/Whole ratio is displayed as mean with black dots representing individual ratios from two independent experiments; each error bar represents the standard deviation (SD). The blots were cropped for presentation of target bands, and the original blots of two independent experiments with their corresponding densitometry analysis are presented in Supplementary data (Figure S8).

Discussion

IWS1 is a transcription elongation factor and a downstream effector of AKT that plays a key role in the progression of multiple types of cancer13,35. In the present study, we used computational methods to identify compounds that bind to the structured domain of IWS1 where it interacts with Spt6. Two top-ranked candidates of the in silico modeling, Ketotifen and Desloratadine, possess a characteristic tricyclic fused-ring system. Both compounds demonstrated the ability to disrupt the interaction of IWS1 with other members of the RNAPII complex (LEDGF/Spt6). Treatment of DDLPS cancer cell lines with Ketotifen or Desloratadine decreased migration and invasion in vitro further supporting the ability of these compounds to alter cancer cell phenotype.

This work is the first to our knowledge to describe compounds able to disrupt the binding of IWS1 to other coassembly factors within the RNAPII complex. Molecular docking is a fast and efficient method to select promising ligands based on shape-complementary and empirical knowledge of protein-ligand binding, although this approach does not fully replace empirical validation. IWS1 is a challenging target to work with from a structure-based drug discovery perspective, due to the presence of large, unstructured domains on both the N- and C- terminus. The binding site used for this study is partly composed of residues that are close to the N-terminal unstructured domain. Thus, the conformation of the hypothetical binding site may be more flexible and adapt to the ligand through the induced-fit process. The use of molecular docking in this work provides insights into multiple promising categories of drug molecules with the essential space-filling core to fill the hydrophobic concave area on IWS1 in a way like that of Spt6. Moreover, the central seven-membered ring may also be decorated on the side that is opposite to the inner side of the binding site, as shown by the absence of the protein-ligand interaction surface contour. While there are limitations, these ligands are valuable starting structures for further derivatization of more complicated scaffolds to achieve better selectivity and bioavailability. Derivatization as such and efforts toward lead optimization are underway.

IWS1 is known to interact with multiple transcription factors and serves as a central binding hub during the assembly of the RNAP II transcription elongation complex24. In the presence of our lead compounds, Co-IP of IWS1 and Spt6 resulted in decreased binding of IWS1 and Spt6. In addition, the amount of IWS1 bound to another RNAP II transcription factor, LEDGF, was also reduced. This implies that binding of LEDGF to IWS1 may depend on conformational changes induced by the binding of IWS1 and Spt6. Based on our in silico predictions, Ketotifen and Desloratadine are mostly binding to the nonpolar residues within the structured region of IWS1 that are responsible for the interaction with Spt6 and include L652, G658, M662, I682, and W685. Upon binding of our lead compounds, a conformational change may occur that disrupts the TND/TIM binary interactions with other binding partners like LEDGF. Interestingly, we observed an increase in the expression of IWS1 when cells were treated with these compounds. Furthermore, when we performed cell fractionation, analyzing nuclear and cytosolic proteins separately, we observed an enrichment of IWS1 in the nuclear fraction but no change in cytosolic fraction of IWS1. Taken together, these findings suggest that the binding of IWS1 to Ketotifen/Desloratadine may disrupt the endogenous translocation mechanism between the nucleus and cytoplasm resulting in bound IWS1 accumulating in the nucleus. Indirectly this implies binding of the compounds to IWS1, but further investigation is warranted to characterize the impact of binding IWS1 on its function in transcription elongation specifically.

When characterizing the role of our compounds on cellular phenotype, we found that treatment with both Ketotifen and Desloratadine reduced spheroid size and number in human DDLPS cell lines. In addition, treatment with these compounds effectively reduced cell invasion and migration in a dose dependent manner, mimicking what happens when IWS1 expression is reduced using siRNA13. This was true in all cell lines except for the migration of Lipo246 (Supplementary Fig. S2). It is important to note that IWS1 expression in Lipo246 is significantly lower compared to other DDLPS cell lines used in the study, which may explain a weaker effect of IWS1 inhibitors on this cell line. Different expression levels of IWS1 and the characteristically heterogeneous nature of LPS may lead to variability of treatment effect amongst human DDLPS cell lines. As such, the expression of IWS1 may be an important biomarker to selecting patients for this approach.

Our results demonstrate that Lipo863 cells undergo cytoskeletal and morphological rearrangements, aligning to the patterned surfaces and that these are affected in the absence of IWS1 (Supplementary Videos). Treatment with Desloratadine or Ketotifen led to a significant reduction in cell migration at the single-clone level, as indicated by decreased velocity and acceleration compared to control groups. In addition, Ketotifen-treated cells exhibited even lower migration velocity compared to all groups, including the Ketotifen-treated IWS1 KO group. When evaluating cell elongation, Desloratadine and Ketotifen treatments resulted in higher elongation rates than controls. This increased elongation correlated with reduced velocity and directional movement, suggesting that the cells adopted a mesenchymal-like migration pattern, characterized by elevated cell-matrix adhesion and prolonged interaction with their surroundings36,37. Consequently, this may account for the lower motility rate compared to cells that migrate faster. Additionally, axially persistent migration, where cells maintain directional movement over time, further supports the mesenchymal-like migration behavior observed in these cells. This corresponds to our previous findings showing that downregulation of IWS1 impacts both epithelial–mesenchymal and mesenchymal–epithelial transition programs in LPS13. Taken together, these results suggest that inhibiting IWS1 reduces cell motility and invasion without affecting cell viability.

There are several limitations to the current study. In addition to its interactions with IWS1, our data suggests that Ketotifen and Desloratadine have off-target effects and likely bind proteins that also participate in the regulation of cellular migration and invasion. To this end, when IWS1 expression was knocked down using lentiviral transfection or knocked out using CRISPR-Cas9, the effect of Ketotifen and Desloratadine on DDLPS cells was blunted but persisted. To identify non-specific interactions and to decrease working concentrations, further studies are needed. For the resemblance to the TFIIS N-terminal domain (TND), the interaction pattern between IWS1 and Spt6 falls under the category of TND/TIM motifs, which is a common protein-protein interaction motif among various transcription elongation factors38. Thus, the major class of off-target inhibitory effects to avoid includes the competitive inhibition of other TND homologs. In practice, additional virtual screening could be performed to avoid the ligands with high affinity towards the susceptible TND homologs. Furthermore, the binding spectrum of the prioritized ligand scaffolds needs to be analyzed to avoid binding with non-TND homolog targets24. With careful review of observed inhibitory effects of ligands with similar scaffolds, scaffold generalization and structure optimization could be a highly rewarding direction for future projects. Additionally, the current structural model from AlphaFold, along with the rigid-receptor molecular docking approach, are insufficient to reveal the consequences of drug binding to the dynamics of IWS1. Lastly, the lack of in vivo validation and the use of these compounds in preclinical models of DDLPS is a significant limitation. Current efforts are first underway to optimize the interaction with IWS1 and confirm binding using more robust approaches beyond Co-IP in live cells39.

In conclusion, using computational methods, we were able to identify FDA-approved chemical compounds with the ability to disrupt IWS1 binding with other members of the RNAPII complex. Two candidates, Ketotifen and Desloratadine, altered cell phenotype in an IWS1-dependent manner in DDLPS cells at concentrations well below cytotoxic concentrations. These compounds or a close derivative thereof may hold promise as a novel inhibitor of IWS1 and provide an important tool to study the impact of IWS1-mediated transcription elongation in cancer biology.

Methods

Computational methods

Identification of a druggable site at the IWS1/Spt6 interface

In the AlphaFold-predicted structure40,41 for human IWS1 (UniProt: Q96ST2; Last updated in AlphaFold DB version 2022-11-01, created with the AlphaFold Monomer v2.0 pipeline), the domain for AA 545–694 was chosen as the structured core of IWS1. Since the IWS1/Spt6 interface is contained within this region, it was used as the truncated receptor model of IWS1 for further in silico studies. Moreover, the predicted positions of most residues in this region show very high model confidence and very low expected position errors compared to the NMR-resolved structures (PDB ID: 6ZV1). Lastly, the AA 545–694 region is known to have the highest sequence conservation across many species, including humans42.

The truncated receptor model was then imported to the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software package43. Next, the model underwent a two-step structure preparation consisting of residue protonation state determination by the Protonate3D method44 and structure minimization in the Amber14:EHT force field, where the receptor’s non-hydrogen atoms were tethered by restraints with a strength of 10 and a buffer of 0.25. Lastly, the Site Finder function was used to identify the most druggable sites over the prepared receptor. Amongst the top-ranking sites, the putative binding site was constructed using the following residues: L652, K653, G656, I657, G658, R659, M662, I682, W685, S686, and I689. The binding site has a concave shape to accommodate the complementary phenylalanine of Spt6, which is conserved across species including humans.

Construction of the ligand dataset for the preliminary virtual screening

As of November 2022, there were 2,115 unique entries on the ZINC20 database that belong to the FDA-approved subset45. To screen compounds with improved membrane permeability, a filtering condition of − 0.5 < logP < 5 was applied using the computed partition coefficients logP(o/w) in MOE46. The filtered ligand set consisted of 1,103 unique ZINC entries. The 2D representations of the filtered library were exported in the Tripos mol2 format. These entries were then imported into MOE and underwent the ligand preparation process using the Wash method. This method involves rebuilding 3D coordinates with preserved chirality and enumerating the possible ionization states at pH 7. The remaining 1,605 unique ligand structures were then subject to an independent molecular docking calculation as described below.

Molecular Docking calculation

The receptor on IWS1 was converted to a united-atom model using the utility tool “prepare_receptor” in the ADFR suite47. Program AutoGrid FR48 was used to inspect the receptor and generate the grid information. Specifically, a 15.0 Å × 15.0 Å × 15.0 Å cubic box centered at the supposed position of the complementary phenylalanine residue of Spt6 was chosen as the search space for docking. This box encompasses the vast majority of the putative binding site with the exception of the solvent-exposed side (Supplementary data, Figure S9). The solvent-exposed side was intentionally omitted since the contour is trivial at this site49. The prepared ligand structures were converted to the pdbqt format using the python package Meeko50 which enables atom typing for docking with enhanced sampling of macrocycles51. Lastly, AutoDock (RRID: SCR_012746) Vina version 1.2.352 was used to run the docking calculations at an exhaustiveness of 32, and the python binding of version 1.2.5 with a modified scoring function was utilized to re-score the top-ranked poses. All docking calculations were replicated to ensure the reproducibility of the general trends and major outcomes. To address limitations in the default scoring in Vina v1.2.3, particularly biases introduced by glue atoms (used for enhanced macrocycle sampling) and the conservative rotatable bond penalties, we applied a modified scoring function that adjusted rankings to better reflect realistic binding potential. This methodological adjustment ensured that ligands with flexible macrocycles were objectively evaluated alongside smaller or more rigid scaffolds. The full details of receptor preparation, docking grid creation, ligand library curation, and scoring corrections are provided in the Supplementary Data.

Biological validation methods

Cell culture

Human DDLPS cell lines Lipo863 (p60), Lipo246 (p49), Lipo224 (p80) were established as previously reported53 and kindly provided by Dr. Raphael E. Pollock through cryopreserved stocks. Cell line NIH/3T3 (p3) (RRID: CVCL_0594) was kindly provided by Dr. Hua Zhu. Frozen stocks were re-analyzed every 6 months for any changes in cell biology. All cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Corning, 10-013-CV) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, SH30070.03) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Thermo Scientific, 15140-122) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cell lines were periodically checked for mycoplasma using the MycoAlert PLUS Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, LT07-710). All cell lines were used fewer than 10 passages before experiments were conducted.

Small molecules stock preparations

Chemical compounds were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich: Ketotifen (K2628) and Desloratadine (D1069). Stocks of the drugs were freshly prepared in DMSO at 50 mM and diluted directly in cell culture media for further experiments. For the negative control, DMSO was used at the same volume as the drug in the culture media.

In vitro dose-response

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2,000 cells/well (5–7% confluency) and treated with Ketotifen or Desloratadine for 48 h. Cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, G3580). Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using Synergy H1 Multimode Reader (BioTek). IC50 values were calculated with GraphPad Prism 10 (RRID: SCR_002798) using nonlinear regression variable slope four-parameter function with default settings.

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

IWS1/Spt6 complex was immunoprecipitated as follows: Lipo863 cells were seeded at 4 × 106 cell/dish (~ 20% confluency) on 15 cm Petri dishes following the 48-hour treatment with Ketotifen or Desloratadine and DMSO as a negative control. When cells reached 85–95% confluency, they were washed three times with cold PBS and lysed on the plate with 500 µL of the Lysis Buffer. Cells were scraped from the plate, collected in a separate 1.5 mL tube, and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C on an end-over-end rotator. The sample was sonicated with several short ultrasonics pulses of 1–2 s and pauses of 1–2 s using 120 Sonic Dismembrator (Fisherbrand). The sample was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 7 min at 4 °C using Centrifuge 5425 R (Eppendorf). The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and the protein concentration was measured using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, 23225). To improve binding kinetics for the primary antibodies, pre-incubation step with primary antibody was performed: 1.5 mg of the total protein was mixed with 10 µL (10 µg) of anti-IWS1 antibody or 10 µL (1.17 µg) of anti-Spt6 antibody. For the isotype control, 1 µL (2.5 ug) of the Rabbit mAb IgG XP Isotype Control was used. The composition of the Lysis buffer and the information about the antibodies are presented in Supplementary data (Table S2). The reaction mixture was incubated overnight at 4 °C on an end-over-end rotator. For the co-immunoprecipitation reaction, Dynabeads Protein G Immunoprecipitation Kit (Invitrogen, 10007D) was used; the reaction was performed at a ratio of 1.5 mg of total protein per 50 µL (1.5 mg) of magnetic beads and was incubated for 25 min at RT on an end-over-end rotator. All washing steps were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bound proteins were eluted in 30 µL of 1x Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad, 1610747) and analyzed by western blotting. Protein expression was quantified in Fiji software (RRID: SCR_002285)54 and analyzed in GraphPad Prism 10 (RRID: SCR_002798).

Transfections and infections

Cells with knocked-down expression of IWS1 were obtained as described earlier13. Briefly, IWS1 shRNA (shIWS1) and control shRNA (EV) lentiviral particles were used to generate the stable transduction of Lipo863 cell line. To generate lentiviral particles, the lentiviral vector pLKO.1 shRNA against human IWS1 (shIWS1), pLKO.1 TRC non-hairpin control (Addgene #10879 RRID: Addgene_10879) as well as packaging plasmid psPAX2 (Addgene #12260 RRID: Addgene_12260) and enveloping plasmid pMD2.G (Addgene #12259 RRID: Addgene_12259) were used. Lentiviruses were packaged in HEK 293T cells at 70–80% confluency (2 × 106 cells on a 10 cm Petri dish) (RRID: CVCL_0063) by transient transfection of lentiviral constructs and packaging constructs using X-tremeGENE™ HP DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche, 6366244001). Lentiviral supernatants were collected at 48 h post-transfection and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter. Lipo863 cells at 60–70% confluency (4–5 × 106 cells) were infected with viral particles in the presence of 8 µg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, TR-1003-G) for 8 h and selected for stable infection for 72 h with 2 µg/mL puromycin (MilliporeSigma, 54-041-1). IWS1 expression was confirmed using PCR and western blot analysis.

gRNA design and generation of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated KO cells

Five guide RNAs (gRNAs) were designed using CHOPCHOP web tool (RRID: SCR_015723)55. gRNA with the highest given score were chosen, the score included amongst other parameters efficiency and number of off-targets. Guides were cloned into the pX459 vector (Addgene # 62988 RRID: Addgene_62988) using standard cloning methods. Plasmids were validated by Sanger sequencing. gRNAs were validated and assessed by protein expression on Western blot, and the most efficient guide was used for single-cell clones generation (selected gRNA sequence: 5′-TACAGCGGCGACCAGTCAGG-3′). Lipo863 cells were transfected with IWS1-targeting pX459 construct using Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, L3000015) at 60–70% confluency (4–5 × 106 cells on 10 cm Petri dish) according to the manufacturer’s protocol56. Cells were then recovered at 37 °C for 48 h and followed by selection with puromycin (2 µg/mL) for 72 h. Individual cells were sorted into wells of 96-well plates with a FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences). Clones were allowed to grow out from a single cell for 1–2 months. Single-cell clones were screened for IWS1 expression by Western blot. Genomic DNA of clones validated for loss of IWS1 expression was analyzed by Sanger sequencing to identify a single insertion or deletion introduced to ensure clonality. Sequences were analyzed using TIDE software57.

Transwell migration and invasion

Migration was assessed by seeding 5 × 104 cells in the insert with 8.0 μm Pore Polycarbonate Membrane (Corning, 3422). Invasion was evaluated by seeding 1 × 105 cells in the BioCoat Matrigel Invasion Chambers with 8.0 μm PET Membrane (Corning, 354480). Cells were pre-treated at the initial seeding density of 1–2 × 106 cells (20–30% confluency) in 20 µM Ketotifen, 4 µM of Desloratadine, or DMSO as a negative control for 48 h. The upper chamber contained DMEM serum-free medium, and the lower chamber used DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS as a chemoattractant. Both the upper and lower chambers contained either 20 µM Ketotifen, 4 µM Desloratadine, or DMSO. After 24 h, the inserts were washed with PBS, fixed with 70% ethanol for 15 min, and stained with crystal violet solution (Sigma-Aldrich, V5269) for 1 h. Images were taken at x5 magnification using an Axio Vert.A1 FL LED Inverted Photo Microscope (Zeiss). The crystal violet stain was eluted from the inserts using 10% acetic acid. The absorbance was then measured at 595 nm using a Synergy H1 Multimode Reader (BioTek) and analyzed in GraphPad Prism 10 (RRID: SCR_002798).

Patterned substrates fabrication

Microtextured surfaces for cell migration were fabricated by replica molding of Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) from photolithographically patterned silicon wafers. Silicon wafers were prepared by treating them with Hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) and spin-coating with a positive photoresist (AZ1512) at 2500 rpm for 60 s. The coated wafers were then soft-baked on a hot plate at 115 °C for 1 min. A parallel array of ridges and grooves (3 μm wide, 3 μm tall, spaced 3 μm apart) was patterned on the photoresist using contact lithography, followed by 1 min in the MF-419 developer. A 10:1 mixture of 184 Silicone elastomer base and curing agent (Sylgard) was then poured onto the patterned silicon wafer and spin-coated (Laurell Technologies, WS-650MZ-23NPPB). The PDMS was degassed under vacuum and then cured at 65 °C for 2 h. Finally, the PDMS was demolded from the wafer, cut into 12 mm circular shapes, placed in 24-well plates, and sterilized for single-cell migration experiments. The morphology of the wafers and the substrates was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), as shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

Cell migration imaging and analysis

To assess the migratory behavior of DDLPS cells using this platform, we first determined the optimal cell density for accurate tracking. Lipo863 cells were plated in triplicate at six different densities in 24-well plates (2.4 × 105, 1.2 × 105, 6 × 104, 3 × 104, 1.5 × 104, and 7.5 × 103 cells per well). Based on this evaluation, a density of 7.5 × 103 cells per well (3–5% confluency) was selected as optimal for further analysis. The culture plate was then left stationary for 4 hours to allow for the adhesion of cells. Cells were then treated with 20 µM Ketotifen, 4 µM of Desloratadine, or DMSO as a negative control. Following 24 h of treatment, cells were imaged at x20 magnification via time-lapse microscopy every 10 min for over 16 h with a cell culture chamber (Okolab) mounted on an inverted Nikon Ti2 microscope. Cells were maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 20.4% O2, and 92% relative humidity throughout the experiment.

The Nikon NIS.AI software was used to train a machine learning model for cell segmentation on 100 images of varying cell shapes and conditions. The model, trained with manually annotated labels using supervised learning, was optimized over 1490 iterations with a 256 × 256 patch size. The segmented images were analyzed to extract quantitative data on cell behavior, including migration velocity, acceleration, elongation, and straightness (directionality). Custom Python scripts (RRID: SCR_008394) were used to process and visualize the data, which were then compiled for statistical analysis to assess single-cell migration dynamics under different experimental conditions.

3D cell culture: matrigel ECM scaffold method

Cells were seeded into Matrigel as previously reported58. Briefly, Matrigel/cell suspension mix was prepared by gently mixing Matrigel (Corning) and Lipo863 or Lipo224 cells suspended by culture media at a ratio of 1:1 on ice. 50 µL of this Matrigel/cell suspension mix was gently pipetted into each well of a pre-warmed 24-well cell culture plate, forming domes with a final cell density of 2000 cells/well. The plate was incubated for 3 min at 37 ℃ to allow Matrigel to solidify, then flipped upside down (quickly to avoid drips) and incubated for another 15–20 min. The plate was finally returned to right-side up orientation and 500 µL of pre-warmed culture media per well were added along the side of the well to avoid direct destruction of the Matrigel dome. Plate was then incubated at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2. Growth medium containing 20 µM Ketotifen or 4 µM Desloratadine was changed every 2–3 days. Cultures were maintained until day 14. Pictures were taken at x5 and x20 magnification using Axio Vert.A1 FL LED Inverted Photo Microscope (Zeiss). Spheroid diameter was measured in Fiji software (RRID: SCR_002285)54 and analyzed in GraphPad Prism 10 (RRID: SCR_002798).

Cell fractionation

Lipo863 cells were seeded at 20–30% confluency (1–2 × 106 cells) on 10 cm Petri dishes and treated with 20 µM Ketotifen or 4 µM Desloratadine and DMSO as a negative control for 48 h. To isolate nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, modified Rapid, Efficient And Practical (REAP) method for subcellular fractionation was used59. Briefly, after cells have reached 85–95% confluency, they were washed three times with cold PBS, scraped from the plate in 1 mL of cold PBS, and collected into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube. The sample was pelleted at 300 × g for 1 min using Centrifuge 5425 R (Eppendorf), the supernatant was discarded, and the pelleted cells were gently triturated using a pipette tip in 900 µL of cold Lysis buffer: 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma -Aldrich, I8896) in PBS, cOmplete Mini, EDTA-free (Roche, 11836170001), Pierce Phosphatase Inhibitor Mini Tablets (Thermo Scientific, A32957). 150 µL of the lysate was transferred to a separate tube and mixed with 150 µL of RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling, 9806 S) and 100 µL of 4× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, 1610747). This sample was used as a whole cell lysate and kept on ice until the sonication step. The remaining sample was centrifuged at 300 × g for 1 min, and 150 µL of the supernatant was transferred to a separate tube, mixed with 150 µL of RIPA buffer, and 100 µL of 4× Laemmli sample buffer. This sample was used as a cytosolic fraction and kept on ice. The remaining supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended again in 1 mL of cold Lysis buffer and centrifuged at 300 × g for 1 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet (~ 20 µL) was resuspended in 130 µL of RIPA buffer and mixed with 50 µL of 4× Laemmli sample buffer and used as a nuclear fraction. Samples of whole cell lysate and nuclear fraction were sonicated using 120 Sonic Dismembrator (Fisherbrand), and all samples were incubated at 95 °C for 5 min. 10 µL of whole cell lysate and cytosolic fraction sample and 5 µL of nuclear fraction sample were used for western blotting analysis. Antibodies against GAPDH and Lamin A/C were used as cytosolic and nuclear markers, respectively. Antibody against IWS1 was used to analyze IWS1 expression in samples. The ratios of IWS1 expression in nuclear fraction to cytosolic fraction, nuclear fraction to whole cell lysate, and cytosolic fraction to whole cell lysate were calculated in Image Lab software (Bio-Rad).

Western blot analysis

Equal amounts of proteins were loaded and electrophoresed using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, 1620112). After blocking with EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (Bio-Rad, 12010020), the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against GAPDH, IWS1, SPT6, LEDGF, and then with secondary antibodies Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked or Mouse Anti-Rabbit IgG (Light-Chain Specific), HRP-linked. Information about antibodies is provided in Supplementary data (Table S2). Membranes were developed using SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Scientific, 34075). Protein bands were visualized with Odyssey Fc Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Transwell migration and invasion experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3) and duplicate (n = 2), respectively. One-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons or two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons was applied. The results were normalized and presented as mean with error bars representing the standard deviation (SD) from the mean value.

For the migration experiment using aligned structural cues, statistical analyses were performed to evaluate differences in cell behavior between experimental groups. Data normality was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test, while outliers were identified with the ROUT method (Q = 1%). For normally distributed data, a One-way ANOVA was applied followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for post hoc analysis. All data are graphed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and significance was determined at p < 0.05. Each treatment group included n = 3 replicates, with n = 3 videos per well, and approximately 200 cells were identified and analyzed per treatment.

For spheroid formation, two independent experiments were conducted with each of two DDLPS cell lines: Lipo863 and Lipo224. One-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons was applied. The bar diagram represents the mean of spheroid diameter; each error bar represents the standard deviation (SD) from the mean value; each black dot represents one spheroid.

For fraction analysis, western blot image is a representative of two independent experiments. The Nuclear/Whole ratio is displayed as mean with black dots representing individual ratios from two independent experiments; each error bar represents the standard deviation (SD) from the mean value.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by Steps for Sarcoma, the Buckeye Cruise for Cancer, and the American Cancer Society (https://doi.org/10.53354/ACS.CSDG-24-1259694-01-RMC.pc.gr.222005). We are especially grateful to Luciana and Tom Ramsey and Lisa Cisco and Chris Quinn for their contributions and support. We extend our sincere thanks to the Buckeye Bocce Bash and to Monica and Tex Hysell, as well as Katie Smith, for their generous financial support. Computational resources were generously provided by the Ohio Supercomputer Center. We would like to thank Dr. Diogo Santos-Martins in the Center for Computational Structural Biology at the Scripps Research Institute for valuable discussions on the molecular docking calculations. We also would like to thank Anthony Vetter from Nikon for his guidance with image analysis. Illustrations were created using BioRender.

Author contributions

M.G., Y.H., E.K.T., A.I.S., O.C., A.L., R.P., D.G., H.Z., C.M.H., and J.D.B. conceived the experiments. M.G., Y.H., C.K., E.K.T., A.I.S., S.T., N.S., N.N.T., O.C., K.D., A.L., Y.X., and Z.Z. conducted the experiments. M.G., Y.H., C.K., E.K.T., A.I.S., N.S., N.N.T., O.C., and K.D. analyzed the results. All authors interpreted the data. M.G. and Y.H. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The computational data is available in the ZENODO repository (10.5281/zenodo.15556178). The other datasets generated and analyzed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Conyers, R., Young, S. & Thomas, D. M. Liposarcoma: molecular genetics and therapeutics. Sarcoma2011 (483154). 10.1155/2011/483154 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Sbaraglia, M., Bellan, E. & Dei Tos, A. P. The 2020 WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: news and perspectives. Pathologica113, 70–84. 10.32074/1591-951x-213 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Traweek, R. S. et al. Targeting the MDM2-p53 pathway in dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Front. Oncol.12, 1006959. 10.3389/fonc.2022.1006959 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gootee, J. M. et al. Treatment facility: an important prognostic factor for dedifferentiated liposarcoma survival. Fed. Pract.36, S34–s41 (2019). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu, X. et al. Recurrence of locally invasive retroperitoneal dedifferentiated liposarcoma shortly after surgery: A case report and literature review. Med. (Baltim).103, e37604. 10.1097/md.0000000000037604 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Bree, E. et al. Retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma: emerging therapeutic strategies. Cancers (Basel). 15. 10.3390/cancers15225469 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Kyriazoglou, A. et al. Well-differentiated liposarcomas and dedifferentiated liposarcomas: systemic treatment options for two sibling neoplasms. Cancer Treat. Rev.125, 102716. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2024.102716 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Italiano, A. et al. Advanced well-differentiated/dedifferentiated liposarcomas: role of chemotherapy and survival. Ann. Oncol.23, 1601–1607. 10.1093/annonc/mdr485 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGovern, Y., Zhou, C. D. & Jones, R. L. Systemic therapy in metastatic or unresectable Well-Differentiated/Dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Front. Oncol.7, 292. 10.3389/fonc.2017.00292 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thway, K. Well-differentiated liposarcoma and dedifferentiated liposarcoma: an updated review. Semin Diagn. Pathol.36, 112–121. 10.1053/j.semdp.2019.02.006 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou, M. Y., Bui, N. Q., Charville, G. W., Ganjoo, K. N. & Pan, M. Treatment of De-Differentiated liposarcoma in the era of immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2410.3390/ijms24119571 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Somaiah, N. & Tap, W. MDM2-p53 in liposarcoma: the need for targeted therapies with novel mechanisms of action. Cancer Treat. Rev.122, 102668. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2023.102668 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, Y. et al. Phosphorylation of IWS1 by AKT maintains liposarcoma tumor heterogeneity through preservation of cancer stem cell phenotypes and mesenchymal-epithelial plasticity. Oncogenesis12, 30. 10.1038/s41389-023-00469-z (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fianu, I., Dienemann, C., Aibara, S., Schilbach, S. & Cramer, P. Cryo-EM structure of mammalian RNA polymerase II in complex with human RPAP2. Commun. Biol.4, 606. 10.1038/s42003-021-02088-z (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang, L., Fletcher, A. G., Cheung, V., Winston, F. & Stargell, L. A. Spn1 regulates the recruitment of Spt6 and the swi/snf complex during transcriptional activation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol.28, 1393–1403. 10.1128/MCB.01733-07 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoh, S. M., Cho, H., Pickle, L., Evans, R. M. & Jones, K. A. The Spt6 SH2 domain binds Ser2-P RNAPII to direct Iws1-dependent mRNA splicing and export. Genes Dev.21, 160–174. 10.1101/gad.1503107 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller, C. L. W. & Winston, F. The conserved histone chaperone Spt6 is strongly required for DNA replication and genome stability. Cell. Rep.42, 112264. 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112264 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoh, S. M., Lucas, J. S. & Jones, K. A. The Iws1:Spt6:CTD complex controls cotranscriptional mRNA biosynthesis and HYPB/Setd2-mediated histone H3K36 methylation. Genes Dev.22, 3422–3434. 10.1101/gad.1720008 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonald, S. M., Close, D., Xin, H., Formosa, T. & Hill, C. P. Structure and biological importance of the Spn1-Spt6 interaction, and its regulatory role in nucleosome binding. Mol. Cell.40, 725–735. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.014 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diebold, M. L. et al. The structure of an Iws1/Spt6 complex reveals an interaction domain conserved in TFIIS, Elongin A and Med26. EMBO J.29, 3979–3991. 10.1038/emboj.2010.272 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moorthy, G. S., Jogiraju, H., Vedar, C. & Zuppa, A. F. Development and validation of a sensitive assay for analysis of midazolam, free and conjugated 1-hydroxymidazolam and 4-hydroxymidazolam in pediatric plasma: application to pediatric Pharmacokinetic study. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci.1067, 1–9. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.09.030 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thangadurai, S., Dhanalakshmi, A. & Kannan, M. Separation and detection of certain benzodizepines by Thin-Layer chromatography. Malaysian J. Forensic Sci.4, 47–53 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machu, T. K. Therapeutics of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists: current uses and future directions. Pharmacol. Ther.130, 338–347. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.02.003 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cermakova, K. et al. A ubiquitous disordered protein interaction module orchestrates transcription elongation. Science374, 1113–1121. 10.1126/science.abe2913 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stuelten, C. H., Parent, C. A. & Montell, D. J. Cell motility in cancer invasion and metastasis: insights from simple model organisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 18, 296–312. 10.1038/nrc.2018.15 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallego-Perez, D. et al. Microfabricated mimics of in vivo structural cues for the study of guided tumor cell migration. Lab. Chip. 12, 4424–4432. 10.1039/c2lc40726d (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallego-Perez, D. et al. On-Chip clonal analysis of Glioma-Stem-Cell motility and therapy resistance. Nano Lett.16, 5326–5332. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b00902 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duarte-Sanmiguel, S. et al. Guided migration analyses at the single-clone level uncover cellular targets of interest in tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cell populations. Sci. Rep.10, 1189. 10.1038/s41598-020-57941-8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burger, G. A., van de Water, B., Le Devedec, S. E. & Beltman, J. B. Density-Dependent migration characteristics of Cancer cells driven by pseudopod interaction. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.10, 854721. 10.3389/fcell.2022.854721 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaicharoenaudomrung, N., Kunhorm, P. & Noisa, P. Three-dimensional cell culture systems as an in vitro platform for cancer and stem cell modeling. World J. Stem Cells. 11, 1065–1083. 10.4252/wjsc.v11.i12.1065 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edmondson, R., Broglie, J. J., Adcock, A. F. & Yang, L. Three-dimensional cell culture systems and their applications in drug discovery and cell-based biosensors. Assay. Drug Dev. Technol.12, 207–218. 10.1089/adt.2014.573 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Rijt, A., Stefanek, E. & Valente, K. Preclinical testing techniques: paving the way for new oncology screening approaches. Cancers (Basel). 15. 10.3390/cancers15184466 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Palmer, A. C. & Kishony, R. Opposing effects of target overexpression reveal drug mechanisms. Nat. Commun.5, 4296. 10.1038/ncomms5296 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen, A. A. et al. Dynamic proteomics of individual cancer cells in response to a drug. Science322, 1511–1516. 10.1126/science.1160165 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanidas, I. et al. Phosphoproteomics screen reveals Akt isoform-specific signals linking RNA processing to lung cancer. Mol. Cell.53, 577–590. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.018 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridley, A. J. et al. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science302, 1704–1709. 10.1126/science.1092053 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedl, P., Locker, J., Sahai, E. & Segall, J. E. Classifying collective cancer cell invasion. Nat. Cell. Biol.14, 777–783. 10.1038/ncb2548 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cermakova, K., Veverka, V. & Hodges, H. C. The TFIIS N-terminal domain (TND): a transcription assembly module at the interface of order and disorder. Biochem. Soc. Trans.51, 125–135. 10.1042/bst20220342 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yin, Y. et al. Quantification of binding of small molecules to native proteins overexpressed in living cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc.146, 187–200. 10.1021/jacs.3c07488 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with alphafold. Nature596, 583–589. 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varadi, M. et al. AlphaFold protein structure database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res.50, D439–D444. 10.1093/nar/gkab1061 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fischbeck, J. A., Kraemer, S. M. & Stargell, L. A. SPN1, a conserved gene identified by suppression of a Postrecruitment-Defective yeast TATA-Binding protein mutant. Genetics162, 1605–1616. 10.1093/genetics/162.4.1605 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) v. 2022.02 (Chemical computing group ULC, 910–1010 (2023). Sherbrooke St. W., Montreal, QC H3A 2R7, Canada.

- 44.Labute, P. Protonate3D: assignment of ionization States and hydrogen coordinates to macromolecular structures. Proteins75, 187–205. 10.1002/prot.22234 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Irwin, J. J. et al. ZINC20—A free Ultralarge-Scale chemical database for ligand discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model.60, 6065–6073. 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00675 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soliman, K., Grimm, F., Wurm, C. A. & Egner, A. Predicting the membrane permeability of organic fluorescent probes by the deep neural network based lipophilicity descriptor DeepFl-LogP. Sci. Rep.11, 6991. 10.1038/s41598-021-86460-3 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ravindranath, P. A., Forli, S., Goodsell, D. S., Olson, A. J. & Sanner, M. F. AutoDockFR: advances in Protein-Ligand Docking with explicitly specified binding site flexibility. PLoS Comput. Biol.11, e1004586. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004586 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, Y., Forli, S., Omelchenko, A., Sanner, M. F. & AutoGridFR Improvements on AutoDock affinity maps and associated software tools. J. Comput. Chem.40, 2882–2886. 10.1002/jcc.26054 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ravindranath, P. A. & Sanner, M. F. AutoSite: an automated approach for pseudo-ligands prediction-from ligand-binding sites identification to predicting key ligand atoms. Bioinformatics32, 3142–3149. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw367 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meeko v. 0.4.0.

- 51.Forli, S. & Botta, M. Lennard-Jones potential and dummy atom settings to overcome the AUTODOCK limitation in treating flexible ring systems. J. Chem. Inf. Model.47, 1481–1492. 10.1021/ci700036j (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eberhardt, J., Santos-Martins, D., Tillack, A. F. & Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new Docking methods, expanded force field, and Python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model.61, 3891–3898. 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peng, T. et al. An experimental model for the study of well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcoma; deregulation of targetable tyrosine kinase receptors. Lab. Invest.91, 392–403. 10.1038/labinvest.2010.185 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 676–682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Labun, K. et al. CHOPCHOP v3: expanding the CRISPR web toolbox beyond genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res.47, W171–W174. 10.1093/nar/gkz365 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geng, B. C. et al. A simple, quick, and efficient CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing method for human induced pluripotent stem cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 41, 1427–1432. 10.1038/s41401-020-0452-0 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brinkman, E. K., Chen, T., Amendola, M. & van Steensel, B. Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res.42, e168. 10.1093/nar/gku936 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tahara, S. et al. Comparison of three-dimensional cell culture techniques of dedifferentiated liposarcoma and their integration with future research. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.12, 1362696. 10.3389/fcell.2024.1362696 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki, K., Bose, P., Leong-Quong, R. Y., Fujita, D. J. & Riabowol, K. REAP: A two minute cell fractionation method. BMC Res. Notes. 3, 294. 10.1186/1756-0500-3-294 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The computational data is available in the ZENODO repository (10.5281/zenodo.15556178). The other datasets generated and analyzed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.