Abstract

Purpose

To determine the dose of melatonin with an optimal pharmacokinetic profile and to test whether this dose reduces the prevalence of delirium in mechanically ventilated ICU patients as compared to placebo.

Methods

DEMEL, a multicenter adaptive phase 2b/3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial included patients at 20 health centers in France from February 1st, 2019 through January 5th, 2021. Patients were randomized (1:1:1) to receive either placebo or low (0.3 mg) or high (3 mg) dose melatonin enterally at 9:00 p.m. for 14 consecutive nights or until death or ICU discharge, whichever came first. The interim primary endpoint (activity stage) was the percentage of patients who achieved an optimal melatonin pharmacokinetic profile 24 h after starting study treatment; the final primary endpoint (efficacy phase) was the percentage of patients who experienced delirium between randomization and day 14 (or until death or ICU discharge, whichever came first). Delirium was assessed twice daily using the Confusion Assessment Method for ICU.

Results

We randomized 355 patients and included 334 in the primary analysis. At the preplanned analysis of the activity stage performed in 75 patients, the low-dose melatonin group had the highest rate of optimal pharmacokinetic profiles (12/24, 50%) when compared with the high-dose melatonin group (6/25, 24%) and the placebo group (0/26). Therefore, the Steering Committee recommended that the high-dose melatonin group be discontinued and that the low-dose melatonin group be selected to continue in the efficacy phase along with the placebo group. At the end of the efficacy stage, there was no difference in the final primary outcome of delirium incidence between the low-dose melatonin group and the placebo group: 80/147 (54.4%) vs 85/154 (55.2%), risk ratio, 0.986 [95% CI 0.803 to 1.211]; key secondary outcomes were also similar between groups. These included sleep quality, delirium-free, coma-free, and ventilator-free days at day 28; ICU and hospital length of stay; mortality at day 28, in the ICU, and in hospital; as well as long-term outcomes such as quality of life and postintensive care syndrome at day 90.

Conclusions

This randomized clinical trial found that the low-dose of melatonin (0.3 mg nightly) achieved a better pharmacokinetic profile than the high-dose (3 mg nightly), but did not change the incidence of delirium compared to placebo in mechanically ventilated critically-ill patients.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrial.gov website (NCT03524937).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00134-025-08002-z.

Keywords: Delirium, Melatonin, Ventilation, Pharmacokinetics

Take-home message

| In this multi-arm, multi-stage, randomized clinical trial involving 355 patients, the pharmacokinetic profile of melatonin 0.3 mg nightly for 14 nights outperformed that of melatonin 3 mg nightly in the “activity” stage of the trial. Melatonin 0.3 mg nightly was selected for the “efficacy” stage of the trial, but did not reduce the prevalence of delirium compared with placebo in the final analysis. |

Introduction

Delirium is an acute disorder in attention and awareness with additional disturbances in cognition. Delirium was reported in up to 80% of mechanically ventilated patients. Delirium has been associated with poor outcomes in critically ill patients, including higher mortality, longer duration of mechanical ventilation and lengths of stay, with cognitive impairment after discharge in survivors [1].

Disturbances of sleep and circadian integrity are frequent in the critically-ill [2] and have been implicated in delirium pathophysiology. For example, alterations in the circadian rhythm of melatonin excretion in patients receiving mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit (ICU) were more profound in delirious patients as compared to their counterparts [3]. Melatonin is a pleiotropic neurohormone produced by the pineal gland during the hours of darkness, with peak concentrations of ~ 100 pg/mL between 02:00 and 04:00 h [4], while bright light suppresses its production in the early morning [5]. Nightly melatonin peak accelerates sleep initiation and improves sleep maintenance and efficiency [6]. Treatment with melatonin is safe, inexpensive, and widely used in the community [7]. Recent clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, anxiety, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption suggest administering melatonin over no melatonin in adult patients admitted to the ICU [8]. However, the certainty of evidence is low, as previous randomized controlled trials (RCT) that explored the use of melatonin or melatonin receptor agonists for delirium prophylaxis in the ICU found conflicting results [9–16]. Of note, none specifically focused on mechanically ventilated patients, and none examined low-dose melatonin (all dosages were > 3 mg) except for a small feasibility study (< 25 patients per arm) that was not designed to assess clinical outcomes [17]. Such higher doses may induce a “hangover” effect due to increased/prolonged plasma concentration with drowsiness during the late morning, jeopardizing the reset of the circadian clock [18, 19]. Recent guidelines highlight the need for RCTs to determine the optimal dosing of melatonin [8] and to include mechanically ventilated patients in future studies [20]. To address these uncertainties, we conducted a RCT based on two primary hypotheses: (1) a lower dose of melatonin (0.3 mg nightly—suggested as physiologic in pharmacokinetic studies) [18, 21] may offer a more favorable pharmacokinetic profile than a higher dose (3 mg nightly—the most commonly used oral dose in RCTs); and (2) the optimal melatonin dosing regimen may help prevent the onset of delirium in mechanically ventilated ICU patients.

Methods

Study and design

The Delirium and MELatonin (DEMEL) trial was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial incorporating an adaptive seamless phase 2b/3 multiarm multistage design that enrolled patients receiving mechanical ventilation in the ICU in 20 health centers in France from February 2019 to January 2021 (details on the health centers are available in the eAppendix in electronic supplementary material 2). The study was designed to evaluate two dosing regimens of melatonin (0.3 vs 3 mg nightly) for achieving pharmacokinetic targets (activity stage) and to test the efficacy of the best-performing dosing regimen in preventing delirium (efficacy stage) in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation in the ICU. We used an interim analysis at the end of the activity stage to select the best performing melatonin dosing regimen to continue accrual for fully powered efficacy analysis. The first and final versions of the protocol and a summary of changes are available in the Trial Protocol in electronic supplementary material 1. A central institutional ethics review board (Comité de Protection des Personnes, Ile de France VII, Paris, France) approved this trial (N°. RIPH1: 2018–04-06, N°. EUDRACT: 2017–003321-14, N°. ANSM: 2018–03-00007) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Each patient or next of kin provided written informed consent (eMethods 1 in electronic supplementary material 2). This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Patients

All adult patients (≥ 18 years) receiving invasive mechanical ventilation with an expected length of stay greater than 48 h in the ICU were eligible for the study. Main exclusion criteria included delirium onset before or at randomization, invasive mechanical ventilation of more than 48 h prior to randomization, no enteral route available, pregnancy and lactation, patients with conditions that would make assessments for delirium unreliable (like alcohol withdrawal syndrome, cardiac arrest, stroke, traumatic brain injury or neurosurgery), hypersensitivity to melatonin, medications that interact with melatonin or modify its metabolism, and hepatic impairment. The full list of eligibility criteria is available in the eMethods 2 in electronic supplementary material 2.

Randomization and masking

Centralized randomization using random block sizes between 2 and 6 was stratified by center, with a 1:1:1 ratio (placebo, lower melatonin dose and higher melatonin dose) during the activity stage and a 1:1 ratio (placebo, best performing melatonin dosing regimen) during the efficacy stage. Clinical staff, investigators, trial statisticians, and patients remained blinded. The statisticians were unblinded only after the statistical plan was finalized, data collection completed, and the database locked.

Trial interventions

Immediately after randomization, patients began receiving placebo, 0.3 mg of melatonin or 3 mg of melatonin, all of which were administered via the enteral route once nightly at 9:00 p.m. for 14 nights, or until hospital discharge or death, whichever came first. We selected 3 mg as the higher dose because it is the most commonly used in RCTs, and 0.3 mg as the lower dose, as it represents a dose suggested as physiologic in pharmacokinetic studies [18, 21]. The study product (melatonin or placebo) was formulated as a compounded syrup with a predefined concentration of immediate-release melatonin and was provided in sealed glass bottles. The syrup's volume, visual appearance, taste, and smell, as well as the size and color of the vials, were identical across the three groups to maintain blinding. Study treatment was discontinued in the event of inability to use the enteral route, or food intolerance with vomiting. The details of the study treatment are provided in eMethods 1 in electronic supplementary material 2. Patient compliance was defined as adherence to assigned treatment for 75% or more of the time recommended by the protocol or until death or hospital discharge, whichever occurred first. In all groups, current recommendations for the management of patients under mechanical ventilation were followed, including the use of a local protocol for sedation (with a target Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale typically maintained between 0 and -1 during sedation) [22] and for ventilator weaning [23, 24] in each center. Standard care in the participating ICU incorporated a sleep and delirium prevention strategy, including the ABCDE bundle (Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium monitoring/management, and Early mobility) [25]. Although there is no current consensus on the choice of curative pharmacological treatment for delirium, antipsychotic neuroleptics were recommended in cases of delirium with agitation, as per usual practice of participating centers [26, 27].

Primary and secondary outcomes

The interim primary outcome (activity stage) was the percentage of patients with an optimal pharmacokinetic profile of melatonin 24 h after initiation of study treatment. A pharmacokinetic profile was considered optimal if the change in melatonin concentration (i.e., compared to the baseline concentration before study treatment administration) [19] was > 1000 pg/mL at peak (i.e., 30 min after administration) and < 100 pg/mL at 8:00 a.m. in the next morning [28]. The concentration of melatonin was measured in a blinded fashion using mass spectroscopy during the second administration of the study drug [29].

The final primary outcome (efficacy stage) was the percentage of patients who developed delirium between randomization and day 14 (or death or ICU discharge whichever occurred first). Delirium was assessed throughout the study period in a blinded manner by clinical nurses and physicians using the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) [30], administered twice daily by trained staff (using the French-translated CAM-ICU manual) [31] to all evaluable patients, defined as those with a Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale (RASS) [32] score ≥ –3 and assessed at least two hours after cessation of sedative drugs [33]. Patients were diagnosed as delirious if the CAM-ICU was positive at least once and/or if they were treated with antipsychotic neuroleptics due to the onset of delirium between two assessments [34].

Secondary outcomes at day 14 (or until death or ICU discharge, whichever came first) were delirium days, delirium- and coma-free days, cumulative doses of sedatives and opioids, use of sleep aid drugs, neuroleptics and physical restraints, use of physiotherapy and clinical assessment of muscle strength (using the Medical Research Council scale) [35], use of earplugs and eye masks and clinical assessment of sleep (measured daily using the Richards–Campbell questionnaire administered by the patient and/or bedside nurse) [36]. Secondary outcomes at day 28 were duration of mechanical ventilation, ventilator-free days, length of stay (ICU and hospital), and mortality (ICU, hospital, and at day 28). Secondary outcomes at day 90 included quality of life (Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36) [37], dependence (Activities of Daily Living [38] and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living) [39], anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale) [40], and post-traumatic stress (Impact of Event Scale-Revised) [41] in survivors. Furthermore, the incidence of all adverse events was monitored. Complete definitions of study outcomes are available in eMethods 3 in electronic supplementary material 2.

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

Sample size calculation for the primary end points and all statistical analyses including those used to compare secondary outcomes are detailed in eMethods 4 in electronic supplementary material 2 and statistical analysis plan in electronic supplementary material 3. We aimed to include 75 patients in the activity stage and 345 patients overall for the study.

Primary end point analyses were performed according to randomization group on intention-to-treat basis and additional supportive analyses were performed on the per-protocol population who did not deviate from the protocol, as defined in eMethods 4 in electronic supplementary material 2. For the primary endpoints analyses, the approach described by Friede et al.[42] was used, making use of all data collected during the two phases and the different randomization arms. All analyses were conducted using complete cases without imputing missing data, in accordance with a predefined statistical analysis plan and using Stata, version 16.1 (Stata Corp) and R, version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Statistical tests were 2-tailed and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data analyses were performed from June 2023 to September 2024.

Results

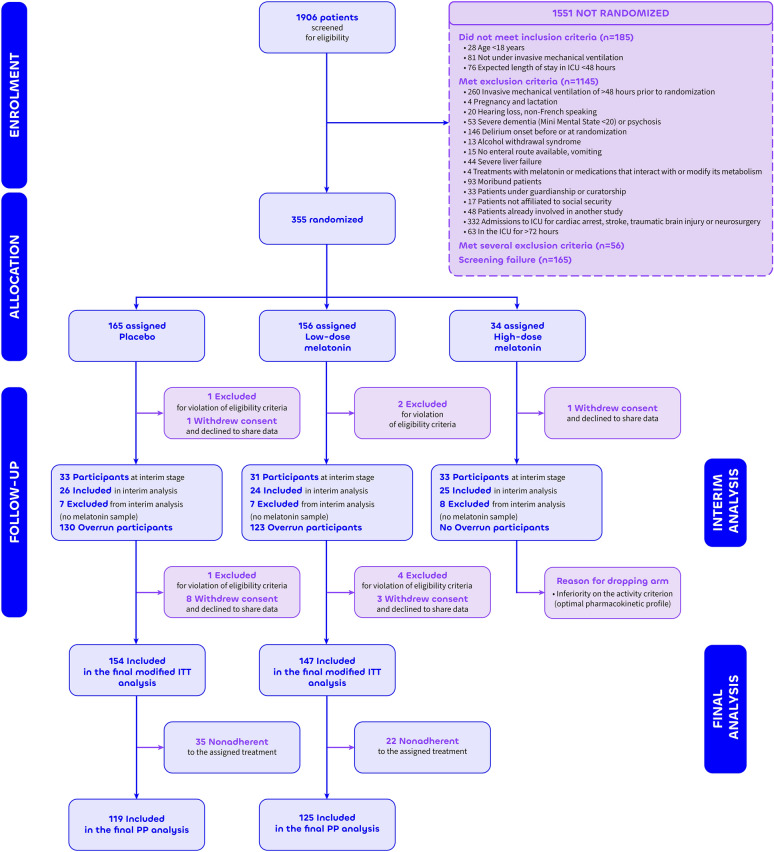

From February 1st, 2019 to January 5, 2021, a total of 1906 patients were screened of whom 355 patients (mean age ± standard deviation, 63.6 ± 13.6 years; 237 (67%) men and 118 (33%) women; race and ethnicity information were not collected) were randomized to receive placebo (165 patients; 46%), low-dose melatonin (156 patients; 44%), and high-dose melatonin (34 patients, 10%),

Of the 355 patients randomized, 21 patients were removed from the main analysis for withdrawal of consent and refusal to share data (n = 13) or violation of eligibility criteria after protocol review (n = 8); the remaining 334 patients (median [IQR] age, 66.0 [57.0;73.0] years; 224 (67%) men and 110 (33%) women) composed the intention-to-treat population (Fig. 1, Table 1). Acute respiratory failure was the main reason for intubation (233 patients; 71%). The median [IQR] time from intubation to randomization was 1.00 [0.00;1.00] day. Baseline characteristics, including severity scores and risk score for delirium showed no clinically relevant differences among the 3 groups (Table 1). Patient compliance was high (≥ 75%) in all groups (P = 0.41; eTable 1 in electronic supplementary material 2).

Figure 1.

Study Flow Chart.adefined as spending < 75% of time on assigned treatment from randomization to day 14 (or until death or discharge from intensive care unit, whichever comes first), ITT intention-to-treat, PP per protocol

Table 1.

General characteristics of patients, by study group

| Characteristic | N | Placebo N = 154 |

Low-dose melatonin N = 147 |

High-dose melatonin N = 33 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | ||||

| Gender, women | 334 | 50 (32.5%) | 47 (32.0%) | 13 (39.4%) |

| Age, years | 334 | 64.0 [56.0;71.0] | 68.0 [58.5;74.0] | 65.0 [55.0;72.0] |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 309 | 26.4 [23.1;31.6] | 26.5 [23.0;30.6] | 27.0 [23.7;29.2] |

| Past history | ||||

| Smoking | ||||

| Non smoker | 324 | 91 (61.9%) | 84 (58.3%) | 19 (57.6%) |

| Current | 24 (16.3%) | 28 (19.4%) | 8 (24.2%) | |

| Past | 32 (21.8%) | 32 (22.2%) | 6 (18.2%) | |

| COPD suspected or diagnosed | 327 | 29 (19.5%) | 37 (25.5%) | 10 (30.3%) |

| SAS with CPAP therapy | 318 | 9 (6.2%) | 14 (10.0%) | 2 (6.3%) |

| Hypertension | 326 | 75 (50.3%) | 66 (45.8%) | 18 (54.5%) |

| Heart failure | 326 | 16 (10.7%) | 19 (13.2%) | 7 (21.2%) |

| Stroke | 327 | 8 (5.3%) | 5 (3.5%) | 1 (3.0%) |

| Moderate cognitive impairmenta | 327 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 3 (9.1%) |

| Seizure | 328 | 6 (4.0%) | 6 (4.1%) | 1 (3.0%) |

| Psychiatric disease | 328 | 5 (3.3%) | 3 (2.1%) | 2 (6.1%) |

| Psychotropic drug | 328 | 21 (14.0%) | 22 (15.2%) | 4 (12.1%) |

| Benzodiazepine | 328 | 14 (9.3%) | 13 (9.0%) | 1 (3.0%) |

| Antidepressant | 328 | 15 (10.0%) | 6 (4.1%) | 1 (3.0%) |

| Neuroleptic | 328 | 5 (3.3%) | 4 (2.8%) | 3 (9.1%) |

| Other psychotropic drug | 328 | 5 (3.3%) | 5 (3.4%) | 1 (3.0%) |

| Drug addiction | 328 | 5 (3.3%) | 4 (2.8%) | 4 (12.1%) |

| Alcoholism | 328 | 21 (14.0%) | 16 (11.0%) | 5 (15.2%) |

| Cirrhosis | 328 | 5 (3.3%) | 8 (5.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Diabetes | 328 | 37 (24.7%) | 40 (27.6%) | 12 (36.4%) |

| Chronic renal failure | 328 | 26 (17.3%) | 20 (13.8%) | 7 (21.2%) |

| Immunosupression | 328 | 30 (20.0%) | 29 (20.0%) | 11 (33.3%) |

| Steroids at admission | 328 | 14 (9.3%) | 13 (9.0%) | 5 (15.2%) |

| Metastatic cancer | 328 | 5 (3.3%) | 8 (5.5%) | 3 (9.1%) |

| Hemopathy | 328 | 7 (4.7%) | 2 (1.4%) | 2 (6.1%) |

| HIV–AIDS | 328 | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (0.7%) | 3 (9.1%) |

| Other immunosupression | 328 | 15 (10.0%) | 11 (7.6%) | 1 (3.0%) |

| ICU | ||||

| Main reason for intubation | ||||

| Respiratory distress | 329 | 100 (66.7%) | 111 (76.0%) | 22 (66.7%) |

| Shock | 25 (16.7%) | 22 (15.1%) | 3 (9.1%) | |

| Coma | 10 (6.7%) | 6 (4.1%) | 3 (9.1%) | |

| Other | 15 (10.0%) | 7 (4.8%) | 5 (15.2%) | |

| Infection at admission | ||||

| None | 328 | 39 (26.0%) | 31 (21.4%) | 11 (33.3%) |

| Pulmonary | 81 (54.0%) | 101 (69.7%) | 16 (48.5%) | |

| Other | 30 (20.0%) | 13 (9.0%) | 6 (18.2%) | |

| PRE-DELIRICb | 229 | 0.32 [0.26;0.39] | 0.35 [0.27;0.42] | 0.32 [0.23;0.39] |

| E-PRE-DELIRIC risk scorec | 313 | 0.38 [0.31;0.44] | 0.40 [0.33;0.46] | 0.42 [0.35;0.49] |

| SOFA score at randomization | 325 | 7.0 [5.0;10.0] | 7.0 [5.0;10.0] | 8.0 [6.0;11.0] |

| SAPS II score at admission | 326 | 36.0 [26.0;49.0] | 33.5 [27.0;45.3] | 37.0 [32.0;45.0] |

ICU Intensive care unit, SAS Sleep apnea syndrome, CPAP Continuous Positive Airway Pressure, COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus, AIDS Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment , SAPS II Simplified Acute Physiology Score II

Data are number (%) or median [25%;75% percentiles]

aMini-Mental State Examination between 20 and 23 [60]

bThe delirium prediction model (PRE-DELIRIC) includes ten variables assessed during the 24h following ICU admission for prediction of delirium during ICU stay [61]. The calculated probability is a decimal value between 0 and 1 representing the probability of the patient developing delirium during ICU stay

cThe early prediction model for delirium (E-PRE-DELIRIC) includes nine variables assessed at ICU admission for early prediction of delirium in critically-ill patient [34]. The calculated probability is a decimal value between 0 and 1 representing the probability of the patient developing delirium within the first few days of ICU admission.

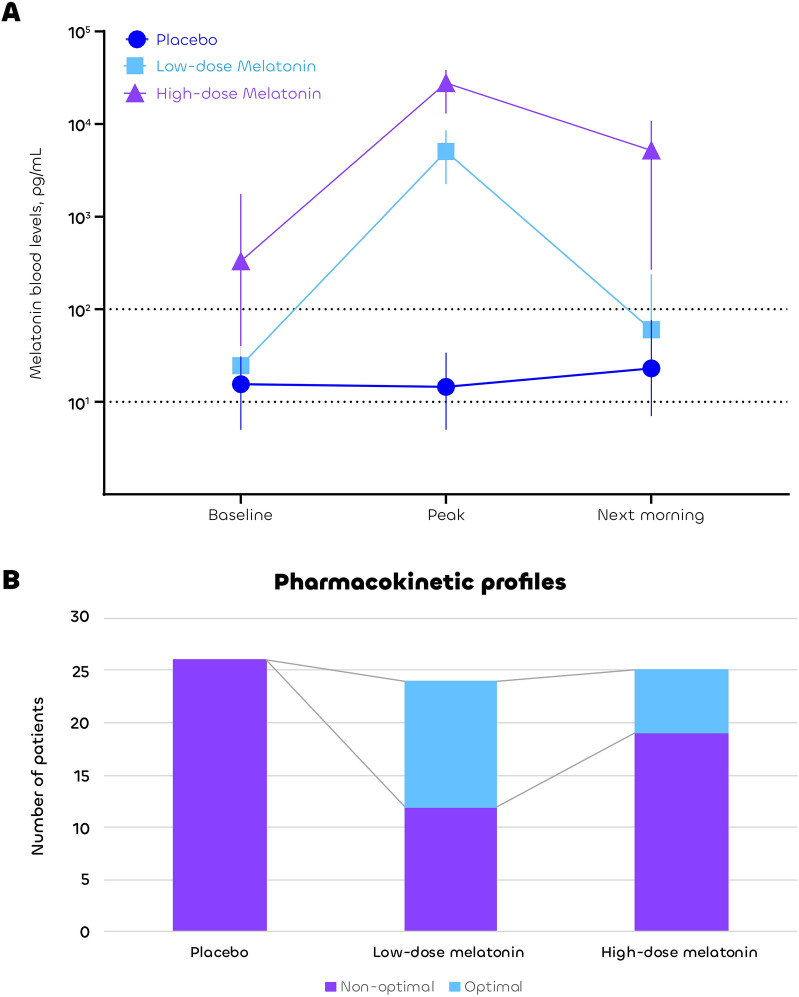

Activity stage

Of the 102 patients included at the activity stage, 27 were excluded from the interim analysis (one for violation of eligibility criteria, four for consent withdrawal, and 22 due to incomplete pharmacokinetic profiles). The most of the missing pharmacokinetic data were attributable to technical limitations and occurred at similar rates across the control, low-dose, and high-dose melatonin groups (7/33, 7/31, and 8/33, respectively; p = 0.96; see Fig. 1). The remaining 75 patients constituted the interim analysis population, with no clinically relevant differences observed among the three groups (eTable 2 in electronic supplementary material 2). The pharmacokinetics of melatonin showed wide inter-individual variability in all groups, with consistently low levels (< 100 pg/mL) and no peak in the placebo group (Fig. 2A). The low-dose melatonin group had the highest rate of the interim primary outcome of optimal pharmacokinetic profiles (12/24, 50%) as compared to the high-dose melatonin group (6/25, 24%) and the placebo group (0/26, 0%) (Fig. 2B). Therefore, the Steering Committee recommended that the high-dose melatonin group be discontinued and that the low-dose melatonin group be selected to continue in the efficacy phase along with the placebo group.

Fig. 2.

Melatonin blood levels (Panel A) and pharmacokinetic profiles (Panel B). Panel A shows the median and interquartile range of melatonin blood concentrations at baseline, peak, and next morning (Log scale). Panel B shows the number of patients with optimal and non-optimal pharmacokinetic profiles

Efficacy stage

Of the 334 intention-to-treat patients, 33 high-dose melatonin patients were removed from the final analysis due to arm discontinuation; the remaining 301 patients composed the final analysis population, with no clinically relevant difference between the low-dose melatonin group (n = 147) and the placebo group (n = 154) (Table 1). The median [IQR] number of assessments per patient was 19.0 [10.3;27.0] and 16.0 [10.5;27.0] in the low-dose melatonin and the placebo group, respectively. Delirium assessment was attempted at 96.4% [89.2;100] and 96.4% [85.7;100] of all available time points in the low-dose melatonin and placebo groups, respectively.

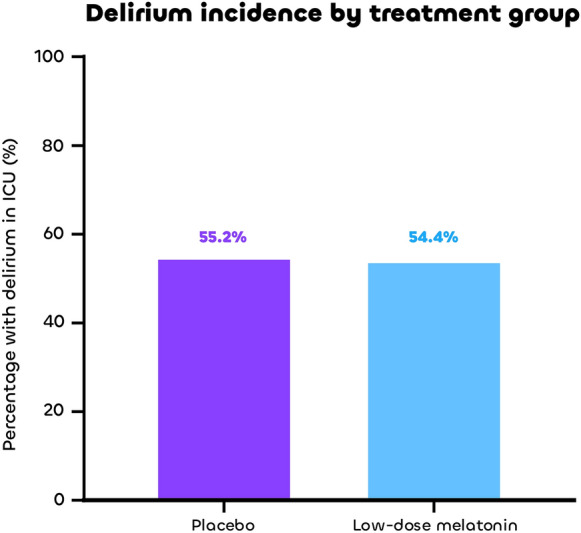

There was no difference in the final primary outcome of delirium incidence between the low-dose melatonin group and the placebo group: 80/147 (54.4%) vs 85/154 (55.2%), risk ratio (RR), 0.986 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.803 to 1.211] (Fig. 3). Sleep depth and latency were worse with low-dose melatonin compared to placebo when assessed by the nurse, but all sleep parameters were similar between groups when assessed by the patient. All other key secondary outcomes were also similar between groups at day 14 (including delirium days, delirium- and coma-free days, cumulative doses of sedatives and opioids, use of sleep aid drugs and neuroleptics and global clinical assessment of sleep), day 28 (including duration of mechanical ventilation, ventilator-free days, length of stay, and mortality), and day 90 (including quality of life, dependence, anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress in survivors) (Table 2). One serious adverse event potentially related to the study drug (a prolonged coma) was reported in a patient from the low-dose melatonin group. Findings of the per-protocol analysis were similar to those of the intention-to-treat analysis (eTable 3 in electronic supplementary material 2). Comparisons involving the high-dose group had limited statistical power and did not yield additional insights (eTable 4 in electronic supplementary material 2). There was no evidence of a between-center effect (eResults in electronic supplementary material 2).

Fig. 3.

Delirium incidence by treatment group

Table 2.

Outcomes of patients with placebo and low-dose melatonin

| Characteristic | N | Placebo N = 154 |

Low-dose melatonin N = 147 |

p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Participant with delirium in ICU | 301 | 85 (55.2%) | 80 (54.4%) | 0.91 |

| Secondary outcomes at day 14 | ||||

| Delirium | ||||

| Number of possible time points per patient | 301 | 23.0 [13.0;28.0] | 20.0 [11.5;28.0] | 0.58 |

| Number of coma and/or delirium assessments per patient | 301 | 19.0 [10.3;27.0] | 16.0 [10.5;27.0] | 0.68 |

| Number of delirium assessments per patient | 301 | 9.0 [4.00;14.0] | 9.0 [4.00;13.0] | 0.78 |

| Days with possible assessment of delirium | 301 | 4.00 [1.00;6.8] | 5.0 [2.00;7.0] | 0.29 |

| Delirium days | 301 |

0.0 [0.0;1.75]; 1.16 ± 1.74 |

0.0 [0.0;2.0]; 1.32 ± 2.04 |

0.75 |

| Fraction of delirium days | 240 | 23.1 [0.00;50.0] | 20.0 [0.00;42.9] | 0.54 |

| Delirium-free days | 301 | 2.00 [0.00;5.0] | 3.00 [0.00;5.0] | 0.39 |

| Fraction of delirium-free days | 240 | 76.9 [50.0;100] | 80.0 [57.1;100] | 0.54 |

| Days with possible assessment of coma and/or delirium | 301 | 9.0 [5.0;13.0] | 9.0 [6.0;13.0] | 0.96 |

| Delirium- and coma-free days | 301 | 2.00 [0.00;5.0] | 3.00 [0.00;4.00] | 0.41 |

| Fraction of delirium- and coma-free days | 297 | 33.3% [0.00;71.4] | 40.0% [0.00;70.0] | 0.33 |

| Psychotropic drugs and physical restraints | ||||

| Cumulative doses of propofol, mg [if any] | 199 | 4,095 [944;13,185] | 4,800 [1,278;14,080] | 0.56 |

| Cumulative doses of sufentanyl, µg [if any] | 243 | 800 [250;2,617] | 734 [246;2,359] | 0.79 |

| Cumulative doses of midazolam, mg [if any] | 176 | 380 [105;1,360] | 272 [89.5;925] | 0.23 |

| Requiring ketamine | 288 | 20 (13.7%) | 19 (13.4%) | 0.94 |

| Requiring dexmedetomidine | 287 | 7 (4.8%) | 8 (5.7%) | 0.74 |

| Requiring neuroleptic for delirium | 298 | 28 (18.4%) | 22 (15.1%) | 0.44 |

| Requiring a sleep aid drug | 298 | 53 (34.9%) | 47 (32.2%) | 0.62 |

| Requiring hydroxyzine [among patients with a sleep aid prescribed] | 100 | 28 (52.8%) | 30 (63.8%) | 0.27 |

| Requiring benzodiazepine [among patients with a sleep aid prescribed] | 100 | 33 (62.3%) | 22 (46.8%) | 0.12 |

| Requiring another sleep aid drug [among patients with a sleep aid prescribed] | 100 | 12 (22.6%) | 6 (12.8%) | 0.20 |

| Requiring physical restraints | 297 | 121 (80.1%) | 124 (84.9%) | 0.28 |

| Physiotherapy and muscle strength | ||||

| MRC score | 96 | 48.0 [41.8;55.3] | 48.0 [37.8;55.3] | 0.57 |

| Motor physiotherapy | ||||

| None | 298 | 45 (29.6%) | 36 (24.7%) | 0.22 |

| Passive | 40 (26.3%) | 31 (21.2%) | ||

| Active | 67 (44.1%) | 79 (54.1%) | ||

| Type of active physiotherapy | ||||

| Helped to stand up | 145 | 11 (16.7%) | 16 (20.3%) | 0.059 |

| Helped to sit up | 50 (75.8%) | 47 (59.5%) | ||

| Other | 5 (7.6%) | 16 (20.3%) | ||

| Earplugs and eye masks | ||||

| Use of earplugs | 297 | 4 (2.6%) | 4 (2.7%) | > 0.99 |

| Use of eye masks | 297 | 3 (2.0%) | 2 (1.4%) | > 0.99 |

| Sleep evaluated by the nurse | ||||

| Number of possible time points per patient | 294 | 3.00 [1.00;5.0] | 3.00 [1.00;5.0] | 0.61 |

| Sleep depth | 226 | 59.6 [40.0;71.8] | 49.4 [26.9;65.0] | 0.004 |

| Sleep latency (time to fall asleep) | 221 | 65.0 [45.2;78.8] | 55.0 [33.7;72.1] | 0.042 |

| Awakenings from sleep | 224 | 56.9 [40.0;75.0] | 50.0 [35.0;70.6] | 0.21 |

| Ability to return to sleep | 221 | 66.1 [42.7;81.5] | 60.0 [34.9;76.3] | 0.13 |

| Sleep quality | 215 | 55.0 [35.0;71.1] | 49.4 [25.0;68.5] | 0.18 |

| Total (mean score) | 226 | 62.3 [40.2;74.0] | 51.0 [32.8;69.6] | 0.022 |

| Noise level | 215 | 67.5 [50.0;80.0] | 60.0 [50.0;74.3] | 0.12 |

| Sleep evaluated by the patient | ||||

| Number of possible time points per patient | 294 | 0.00 [0.00;2.00] | 0.00 [0.00;2.00] | 0.70 |

| Sleep depth | 121 | 44.5 [19.5;65.4] | 45.7 [22.5;64.4] | 0.64 |

| Sleep latency (time to fall asleep) | 119 | 46.0 [25.0;68.8] | 55.0 [31.3;75.0] | 0.12 |

| Awakenings from sleep | 120 | 50.0 [20.0;70.0] | 50.0 [26.9;75.8] | 0.63 |

| Ability to return to sleep | 119 | 42.5 [17.5;70.0] | 50.0 [25.0;77.5] | 0.40 |

| Sleep quality | 121 | 46.5 [17.6;66.2] | 47.5 [25.8;70.0] | 0.36 |

| Total (mean score) | 122 | 44.2 [21.3;69.3] | 47.2 [31.5;70.5] | 0.35 |

| Noise level | 117 | 66.8 [50.0;80.0] | 73.3 [50.0;83.3] | 0.32 |

| Secondary outcomes at day 28 | ||||

| Days on invasive mechanical ventilation | 290 | 8.0 [2.50;21.0] | 8.0 [3.00;26.0] | 0.57 |

| Ventilator-free days at day 28 | 290 | 15.0 [0.00;25.0] | 16.0 [0.00;25.0] | 0.90 |

| Length of stay in ICU, days | 292 | 11.5 [6.0;21.3] | 10.0 [5.0;19.0] | 0.41 |

| Length of stay in hospital, days | 204 | 18.0 [12.0;28.0] | 17.0 [11.0;27.0] | 0.51 |

| Died in ICU | 301 | 36 (23.4%) | 32 (21.8%) | 0.78 |

| Died in hospital | 301 | 39 (25.3%) | 40 (27.2%) | 0.79 |

| 28-day mortality | 301 | 43 (27.9%) | 40 (27.2%) | 0.90 |

| Secondary outcomes at day 90 | ||||

| Health-related quality of life (SF-36) | ||||

| Physical functioning | 132 | 70.0 [42.5;85.0] | 65.0 [40.0;85.0] | 0.56 |

| Physical role | 132 | 25.0 [0.00;50.0] | 25.0 [0.00;75.0] | 0.56 |

| Bodily pain | 133 | 61.0 [41.0;82.0] | 52.0 [41.0;83.0] | 0.75 |

| General health | 132 | 52.0 [37.8;74.3] | 52.0 [42.8;70.8] | 0.79 |

| Vitality | 132 | 45.0 [30.0;60.0] | 47.5 [31.3;65.0] | 0.68 |

| Social functioning | 133 | 75.0 [50.0;87.5] | 87.5 [53.1;100] | 0.19 |

| Emotional role | 132 | 66.7 [33.3;100] | 66.7 [0.00;100] | 0.33 |

| Mental health | 132 | 68.0 [52.0;80.0] | 70.0 [56.0;87.0] | 0.45 |

| Dependence | ||||

| ADL | 129 | 6.0 [5.5;6.0] | 6.0 [5.5;6.0] | 0.56 |

| IADL | 127 | 8.0 [5.0;8.0] | 7.0 [5.0;8.0] | 0.63 |

| Anxiety and depression | ||||

| HADS-A | 125 | 5.0 [3.00;8.0] | 5.0 [3.00;8.0] | 0.78 |

| HADS-D | 125 | 4.00 [1.00;8.0] | 4.00 [2.00;8.0] | 0.94 |

| Post-traumatic stress | ||||

| I-ESR | 119 | 10.0 [5.0;22.0] | 13.0 [4.25;24.0] | 0.62 |

ICU Intensive care unit, SF-36 Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36, ADL Activities of Daily Living, IADL Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, HADS-A Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale for anxiety, HADS-D Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale for depression, I-ESR Impact of Event Scale-Revised, MRC Medical research council scale

Data are number (%) or median [25, 75% percentiles]

aFisher's exact test

Wilcoxon rank sum test

Discussion

In this multicenter, adaptive, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multiarm, multistage study, melatonin 0.3 mg nightly had a better pharmacokinetic profile than 3 mg nightly, but was not associated with a reduction in delirium incidence compared with placebo in mechanically ventilated patients. There were no major differences between the groups in secondary outcomes.

A total of nine randomized controlled trials have investigated the use of melatonin or melatonin receptor agonists for delirium prevention in the ICU, with mixed results [43]. Some studies reported beneficial effects in cardiovascular care units, whereas no significant benefit was observed in general ICUs [43]. This discrepancy may reflect the potential cardiovascular-specific effects of melatonin in the former, while delirium in general ICU populations likely involves more complex and multifactorial mechanisms. Notably, our study is the first to specifically focus on critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients. Critically ill patients are particularly susceptible to circadian disruption, mainly due to the severity of illness, sensory deprivation, and exposure to environments with inadequate sound and lighting [44]. The melatonin secretion profile is considered one of the most robust markers of human circadian rhythm in chronobiology [45]. We found a major alteration of endogenous melatonin secretion in the placebo group, suggesting a loss of circadian rhythm in critically-ill patients, with a loss of the nocturnal physiological peak, as previously reported [46, 47]. In healthy adults, endogenous melatonin secretion is induced at dusk, with a peak of approximately 60–100 pg/mL around midnight and a low "residual" concentration (typically < 10 pg/mL) during the day [6]. The vast majority (> 75%) of patients in the 3 mg melatonin group had a nonoptimal pharmacokinetic profile, with blood melatonin concentrations too often above physiological levels in the next morning. The higher pre-dose melatonin levels observed in the high-dose group are attributable to incomplete elimination from the first dose. A pharmacokinetic analysis by Bourne et al. previously showed that 10 mg of melatonin lead to a supratherapeutic level of melatonin in the morning [19]. Critically ill patients show accelerated absorption and impaired elimination of melatonin as compared to healthy volunteers [19, 46]. These increased/prolonged plasma concentrations may induce “hangover” effects [18, 48].

Melatonin 0.3 mg had a better pharmacokinetic profile than melatonin 3 mg, but did not reduce delirium or improve sleep when compared with placebo. The primary outcome (incidence of delirium) was similar between groups and all 48 secondary outcomes were also similar between groups, except for two items of the nurse-administered sleep questionnaire, the accuracy of which may be affected by subjectivity, variability in nurse skill, and limited patient interaction, among other factors. Only half of the patients had an optimal pharmacokinetic profile with the low-dose melatonin tested. The risk of prolongation of supra-physiologic levels throughout the next day may remain significant with this regimen. Whether even lower doses of melatonin (e.g., 0.1 mg nightly) may better match physiological concentration warrants further research. Optimizing a personalized pharmacokinetic profile based on plasma melatonin levels appears unfeasible in standard clinical practice, as such measurements are technically challenging and rarely performed in routine hospital settings.

Delirium is a complex syndrome, with multiple factors related to the patient, the ICU environment, and medications [34]. Nonpharmacological interventions (earplugs, eye masks, light therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy…) have generally been ineffective when used alone [49–51]. Because the development of delirium is multifactorial, the interventions that are needed may be multidimensional in nature. Further research is needed on the combination of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions in this area [20].

The strengths of our study include its design: a double-blind approach that minimized detection bias, a high overall compliance rate (> 80%), and an adaptive, multiarm, multistage methodology that enabled the exploration of the best-performing melatonin dose in terms of pharmacokinetics while allowing the discontinuation of the poorly performing arm during the study. In addition, our study focused on mechanically ventilated patients with a high severity of illness across a large number of centers, with a median duration of mechanical ventilation exceeding one week. Finally, we assessed both delirium and sleep, as well as long-term patient-centered outcomes.

Our study had several limitations. First, we investigated only two dose regimens of melatonin; an even lower dose could theoretically be of interest to better mimic the normal physiological circadian rhythm of melatonin [28], as the 0.3 mg nightly dose did not achieve the optimal pharmacologic profile in half of the cases. It remains unclear whether an agonist with greater selectivity for the MT1 receptor, such as ramelteon, may offer superior clinical benefits (particularly through improved effects on sleep-onset difficulties) as compared to melatonin [52]. Second, the intervention was limited to 14 days. Whether longer exposure to melatonin might influence its efficacy needs to be investigated; however, delirium typically occurs within the first days of ICU stay. Third, the overall high use of physical restraints (> 80%) may have affected the intervention's impact on the outcome [53]. Fourth, some delirium assessments were missing, but > 96% of time points were assessed. Fifth, sleep assessments made by patients and nurses are inherently subjective and prone to variability, and may differ significantly from objective measurements of sleep, such as those obtained through polysomnography [54]. In addition, the sample size was calculated based on an estimated 30% incidence of delirium by day 14, derived from available literature and institutional data at the time [55]. However, the actual incidence observed was closer to 50%, similar to that reported in other recent RCTs [56]. A substantial decrease in the number of patients included in the final analysis was also observed and as the study population was limited to mechanically ventilated patients with an expected ICU stay of more than 48 h, the generalizability of our findings to other ICU populations may be limited. Of note, the prespecified selection process based on the pharmacokinetic profile during the activity stage was ultimately consistent with the results observed at the efficacy stage, with numerically higher rates of ICU delirium in the high-dose melatonin group (66.7%) compared to the low-dose (54.4%) and control groups (56.0%). These findings align with those of a recent large RCT evaluating a comparable high dose (4 mg), which also found no effect on the prevention of ICU delirium [9]. Given the large number of secondary outcomes assessed, the results should be interpreted as exploratory. Reported p values are unadjusted and are presented for descriptive purposes, with the aim of generating hypotheses and informing future research. Finally, the long-term follow-up assessing postintensive care syndrome and health-related quality of life did not include cognitive function, which could be altered by melatonin treatment [57].

In conclusion, this randomized adaptive clinical trial found that the low dose of melatonin (0.3 mg nightly) achieved a better pharmacokinetic profile than the high dose (3 mg nightly), but did not change the incidence of delirium as compared to placebo in mechanically ventilated critically-ill patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The DEMEL Investigators: Nicolas de Prost, Guillaume Carteaux, Segolène Gendreau, Gaëtan Plantefève, Olivier Pajot, Amélie Chenal, Damien Roux, Coralie Gernez, Noémie Zucman, Muriel Fartoukh, Vincent Labbé, Guillaume Voiriot, Luc Haudebourg, Morgane Faure, Alexandre Demoule, Jean-François Timsit, Lila Bouadma, Etienne de Montmollin, Gael Bourdin, Audrey Large, Fanny Doroszewsky, Louis-Marie Galerneau, Guillaume Rigault, Clara Candille, Christophe Guitton, Mickaël Landais, Nicolas Chudeau, Mickael Le Moal, Maryse Louistisserand, Kmar Hraiech, Tommaso Maraffi, Frédérique Schortgen , Cecilia Tabra Osorio, Malo Emery, Anne Sophie Le Floch, Raphaël Favory, Sébastien Préau, Julien Poissy, Jonathan Zarka, Susanna Bolchini, Antonin Michaud, Antonin Hugerot, Jean Dellamonica, Samir Jaber, Jérome Devaquet, Daniel Da Silva, Jean François Georger, Didier Chevenne, Olivier Thirion, Bernard Do, Lauriane Segaux.

We would like to thank all those who worked on or participated in making the DEMEL study a success, including the patients enrolled in this study, all the site staff who helped to enroll participants, and all the health care professionals who cared for the patients throughout this protocol. In particular, we would like to thank Romain Sonneville, MD, PhD (Department of Intensive Care, Hôpital Bichat, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, France) and Didier Chevenne, MD (Laboratory of Biochemistry-Hormonology, Hôpital Robert-Debré, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, France) for serving on the scientific committee. We thank Amel Gouja and Samia Baloul (Département de Santé Publique, Unité de Recherche Clinique, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Henri-Mondor, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Créteil, France) for their help with the data collection. We thank Olivier Thirion and Bernard Do (Unité Pharmaceutique Essais Recherche Clinique, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Henri-Mondor, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Créteil, France) for their help in preparing study treatment and placebo. These contributors received no compensation beyond their regular salaries.

This trial was an investigator-initiated study with financial support from French Health Ministry (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique Inter-Régional 2017). The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author contributions

Drs Razazi and Mekontso Dessap had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Razazi, Audureau, Mekontso Dessap. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Razazi, Audureau, Mekontso Dessap. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Audureau. Obtained funding: Razazi, Mekontso Dessap. Administrative, technical, or material support: Razazi, Mekontso Dessap. Supervision: Razazi, Mekontso Dessap.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Université Paris-Est Créteil. Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique Inter-Régional 2017

Data availability

See electronic supplementary material 5

Declarations

Conflict of interest

AMD reports grants from and personal fees from Fischer Paykel, Baxter, Air Liquide, and Addmedica, all outside the submitted work.

KR received lecture fees from MSD, Shionogi, and a travel grant from Pfizer outside the submitted work. JDR reports grants and personal fees from Fischer Paykel. NT disclosed payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations from Fisher&Paykel outside this work, NT is supported by Pfizer and Gilead for attending meetings and/or travel outside this work. SN reports personal fees from Pfizer, Shionogi, Biomérieux, Fisher and Peykel, Mundi Pharma and Medtronic. RS reports a grant from LFB outside the submitted work.

No other disclosures were reported.

Footnotes

The DEMEL Investigators are listed in full in the electronic supplementary material 4 and in the acknowledgements.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Armand Mekontso Dessap, Email: armand.dessap@aphp.fr.

For the CARMAS and the REVA research networks, on behalf of the DEMEL Investigators:

Nicolas de Prost, Guillaume Carteaux, Segolène Gendreau, Gaëtan Plantefève, Olivier Pajot, Amélie Chenal, Damien Roux, Coralie Gernez, Noémie Zucman, Muriel Fartoukh, Vincent Labbé, Guillaume Voiriot, Luc Haudebourg, Morgane Faure, Alexandre Demoule, Jean-François Timsit, Lila Bouadma, Etienne Montmollin, Gael Bourdin, Audrey Large, Fanny Doroszewsky, Louis-Marie Galerneau, Guillaume Rigault, Clara Candille, Christophe Guitton, Mickaël Landais, Nicolas Chudeau, Mickael le Moal, Maryse Louistisserand, Kmar Hraiech, Tommaso Maraffi, Frédérique Schortgen, Cecila Tabra Osorio, Malo Emery, Anne Sophie le Floch, Raphaël Favory, Sébastien Préau, Julien Poissy, Jonathan Zarka, Susanna Bolchini, Antonin Michaud, Antonin Hugerot, Jean Dellamonica, Samir Jaber, Jérome Devaquet, Daniel da Silva, Jean François Georger, Didier Chevenne, Olivier Thirion, Bernard Do, and Lauriane Segaux

References

- 1.Stollings JL, Kotfis K, Chanques G et al (2021) Delirium in critical illness: clinical manifestations, outcomes, and management. Inten Care Med 47:1089–1103. 10.1007/s00134-021-06503-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olofsson K, Alling C, Lundberg D, Malmros C (2004) Abolished circadian rhythm of melatonin secretion in sedated and artificially ventilated intensive care patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 48:679–684. 10.1111/j.0001-5172.2004.00401.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dessap AM, Roche-Campo F, Launay J-M et al (2015) Delirium and circadian rhythm of melatonin during weaning from mechanical ventilation: an ancillary study of a weaning trial. Chest 148:1231–1241. 10.1378/chest.15-0525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claustrat B, Leston J (2015) Melatonin: physiological effects in humans. Neurochirurgie 61:77–84. 10.1016/j.neuchi.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewy AJ, Wehr TA, Goodwin FK et al (1980) Light suppresses melatonin secretion in humans. Science 210:1267–1269. 10.1126/science.7434030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brzezinski A (1997) Melatonin in humans. N Engl J Med 336:186–195. 10.1056/NEJM199701163360306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nickkholgh A, Schneider H, Sobirey M et al (2011) The use of high-dose melatonin in liver resection is safe: first clinical experience. J Pineal Res 50:381–388. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00854.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis K, Balas MC, Stollings JL et al (2025) A focused update to the clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, anxiety, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med 53:e711–e727. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wibrow B, Martinez FE, Myers E et al (2022) Prophylactic melatonin for delirium in intensive care (Pro-MEDIC): a randomized controlled trial. Inten Care Med 48:414–425. 10.1007/s00134-022-06638-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ford AH, Flicker L, Kelly R et al (2020) The healthy heart-mind trial: randomized controlled trial of melatonin for prevention of delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc 68:112–119. 10.1111/jgs.16162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vijayakumar HN, Ramya K, Duggappa DR et al (2016) Effect of melatonin on duration of delirium in organophosphorus compound poisoning patients: a double-blind randomised placebo controlled trial. Indian J Anaesth 60:814–820. 10.4103/0019-5049.193664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishikimi M, Numaguchi A, Takahashi K et al (2018) Effect of administration of ramelteon, a melatonin receptor agonist, on the duration of stay in the ICU: a single-center randomized placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med 46:1099–1105. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatta K, Kishi Y, Wada K et al (2014) Preventive effects of ramelteon on delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. JAMA Psychiat 71:397–403. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbasi S, Farsaei S, Ghasemi D, Mansourian M (2018) Potential role of exogenous melatonin supplement in delirium prevention in critically Ill patients: a double-blind randomized pilot study. Iran J Pharm Res 17:1571–1580 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan W, Li C, Song X et al (2022) Prophylactic melatonin for delirium in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 101:e31411. 10.1097/MD.0000000000031411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukundarajan R, Soni KD, Trikha A (2023) Prophylactic melatonin for delirium in intensive care unit: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Indian J Crit Care Med 27:675–685. 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burry LD, Williamson DR, Detsky ME et al (2025) Low-dose melatonin for prevention of delirium in patients who are critically ill: a multicenter, randomized. Placebo-Controlled Feasibility Trial Chest S0012–3692(25):00003. 10.1016/j.chest.2024.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harpsøe NG, Andersen LPH, Gögenur I, Rosenberg J (2015) Clinical pharmacokinetics of melatonin: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 71:901–909. 10.1007/s00228-015-1873-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourne RS, Mills GH, Minelli C (2008) Melatonin therapy to improve nocturnal sleep in critically ill patients: encouraging results from a small randomised controlled trial. Crit Care 12:1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knauert MP, Ayas NT, Bosma KJ et al (2023) Causes, consequences, and treatments of sleep and circadian disruption in the ICU: an official american thoracic society research statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 207:e49–e68. 10.1164/rccm.202301-0184ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brzezinski A (1997) Melatonin in humans. N Engl J Med 336:186–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K et al (2013) Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 41:263–306. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boles J-M, Bion J, Connors A et al (2007) Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J 29:1033–1056. 10.1183/09031936.00010206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quintard H, I’her E, Pottecher J et al (2019) Experts’ guidelines of intubation and extubation of the ICU patient of French Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine (SFAR) and French-speaking Intensive Care Society (SRLF) : In collaboration with the pediatric Association of French-speaking Anaesthetists and Intensivists (ADARPEF), French-speaking Group of Intensive Care and Paediatric emergencies (GFRUP) and Intensive Care physiotherapy society (SKR). Ann Intensive Care 9:13. 10.1186/s13613-019-0483-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ICU Liberation Bundle (A-F). In: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM). https://sccm.org/clinical-resources/iculiberation-home/abcdef-bundles?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 19 Apr 2025

- 26.Andersen-Ranberg NC, Poulsen LM, Perner A et al (2023) Haloperidol vs. placebo for the treatment of delirium in ICU patients: a pre-planned, secondary Bayesian analysis of the AID-ICU trial. Inten Care Med 49:411–420. 10.1007/s00134-023-07024-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mortensen CB, Andersen-Ranberg NC, Poulsen LM et al (2024) Long-term outcomes with haloperidol versus placebo in acutely admitted adult ICU patients with delirium. Inten Care Med 50:103–113. 10.1007/s00134-023-07282-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vural EMS, van Munster BC, de Rooij SE (2014) Optimal dosages for melatonin supplementation therapy in older adults: a systematic review of current literature. Drugs Aging 31:441–451. 10.1007/s40266-014-0178-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carter MD, Wade Calcutt M, Malow BA et al (2012) Quantitation of melatonin and n-acetylserotonin in human plasma by nanoflow LC-MS/MS and electrospray LC-MS/MS: Melatonin and N-acetylserotonin quantitation. J Mass Spectrom 47:277–285. 10.1002/jms.2051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR et al (2001) Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA 286:2703–2710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Resource Language Translations. https://www.icudelirium.org/medical-professionals/downloads/resource-language-translations. Accessed 24 May 2025

- 32.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ et al (2002) The richmond agitation-sedation scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166:1338–1344. 10.1164/rccm.2107138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel SB, Poston JT, Pohlman A et al (2014) Rapidly reversible, sedation-related delirium versus persistent delirium in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189:658–665. 10.1164/rccm.201310-1815OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wassenaar A, van den Boogaard M, van Achterberg T et al (2015) Multinational development and validation of an early prediction model for delirium in ICU patients. Intensive Care Med 41:1048–1056. 10.1007/s00134-015-3777-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleyweg RP, Van Der Meché FGA, Schmitz PIM (1991) Interobserver agreement in the assessment of muscle strength and functional abilities in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Muscle Nerve 14:1103–1109. 10.1002/mus.880141111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamdar BB, Shah PA, King LM et al (2012) Patient-nurse interrater reliability and agreement of the richards-campbell sleep questionnaire. Am J Crit Care 21:261–269. 10.4037/ajcc2012111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heyland DK, Hopman W, Coo H et al (2000) Long-term health-related quality of life in survivors of sepsis. Short Form 36: A valid and reliable measure of health-related quality of life. Crit Care Med. 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW et al (1963) Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185:914–919. 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawton MP, Brody EM (1969) Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9:179–186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S (2003) Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale - revised. Behav Res Ther 41:1489–1496. 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friede T, Parsons N, Stallard N et al (2011) Designing a seamless phase II/III clinical trial using early outcomes for treatment selection: an application in multiple sclerosis. Statist Med 30:1528–1540. 10.1002/sim.4202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan Y, Yang Y, Zhu W et al (2023) Melatonin intervention to prevent delirium in the intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 14:1191830. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1191830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mundigler G, Delle-Karth G, Koreny M et al (2002) Impaired circadian rhythm of melatonin secretion in sedated critically ill patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 30:536–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mirick DK, Davis S (2008) Melatonin as a biomarker of circadian dysregulation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 17:3306–3313. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mistraletti G, Sabbatini G, Taverna M et al (2010) Pharmacokinetics of orally administered melatonin in critically ill patients. J Pineal Res 48:142–147. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mistraletti G, Paroni R, Umbrello M et al (2019) Different routes and formulations of melatonin in critically ill patients. A pharmacokinetic randomized study. Clin Endocrinol. 10.1111/cen.13993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bourne RS, Mills GH (2006) Melatonin: possible implications for the postoperative and critically ill patient. Intensive Care Med 32:371–379. 10.1007/s00134-005-0061-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teng J, Qin H, Guo W et al (2023) Effectiveness of sleep interventions to reduce delirium in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care 78:154342. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2023.154342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smonig R, Magalhaes E, Bouadma L et al (2019) Impact of natural light exposure on delirium burden in adult patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation in the ICU: a prospective study. Ann Intensive Care 9:120. 10.1186/s13613-019-0592-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bannon L, McGaughey J, Verghis R et al (2019) The effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions in reducing the incidence and duration of delirium in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 45:1–12. 10.1007/s00134-018-5452-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kato K, Hirai K, Nishiyama K et al (2005) Neurochemical properties of ramelteon (TAK-375), a selective MT1/MT2 receptor agonist. Neuropharmacology 48:301–310. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Micek ST, Anand NJ, Laible BR et al (2005) Delirium as detected by the CAM-ICU predicts restraint use among mechanically ventilated medical patients. Critical Care Med. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000164540.58515.BF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Donnell D, Silva EJ, Münch M et al (2009) Comparison of subjective and objective assessments of sleep in healthy older subjects without sleep complaints. J Sleep Res 18:254–263. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00719.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salluh JI, Wang H, Schneider EB et al (2015) Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 10.1136/bmj.h2538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS et al (2018) Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med 379:2506–2516. 10.1056/NEJMoa1808217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tseng P-T, Zeng B-Y, Chen Y-W et al (2022) The dose and duration-dependent association between melatonin treatment and overall cognition in alzheimer’s dementia: a network meta- analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Curr Neuropharmacol 20:1816–1833. 10.2174/1570159X20666220420122322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J et al (1996) The SOFA (sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. on behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the european society of intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med 22:707–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F (1993) A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA 270:2957–2963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12:189–198. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Den Boogaard M, Schoonhoven L, Maseda E et al (2014) Recalibration of the delirium prediction model for ICU patients (PRE-DELIRIC): a multinational observational study. Intensive Care Med 40:361–369. 10.1007/s00134-013-3202-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

See electronic supplementary material 5