Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. Approximately 20–30% of women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer eventually develop metastatic disease. Current biomarkers, such as CA15-3 and CEA, detect metastasis in only 60–80% of cases, underscoring the need for improved diagnostic tools. This study investigates the potential of circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 as biomarkers for noninvasive monitoring of breast cancer progression.

Methods

In a prospective study conducted in Taiwan, 396 patients were enrolled, alongside a retrospective study of 134 plasma samples from Western populations. cfDNA was extracted, subjected to sodium bisulfite conversion, and the methylation levels of GCM2 and TMEM240 were measured using QMSP. Monte Carlo analysis assigned 70% of the dataset to a training set and 30% to a validation set, repeated 1000 times. Performance metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were averaged to ensure robustness, supporting the use of combined GCM2 and TMEM240 for monitoring treatment response and tumor burden.

Results

The training set, consisting of 166 breast cancer patients (13.3% with recurrence or metastasis), was utilized to establish the biomarker detection cutoff. Validation in a separate cohort of 325 patients (20% with recurrence or metastasis) demonstrated superior performance compared to CA15-3 and CEA, achieving 95.1% accuracy, 89.4% sensitivity, 96.5% specificity, 86.8% positive predictive value (PPV), and 97.3% negative predictive value (NPV). Monte Carlo analysis of the training data revealed an average sensitivity of 95.7%, specificity of 90.3%, and accuracy of 91.5%, while validation data achieved 92.8% sensitivity, 89.5% specificity, and 90.3% accuracy across 1000 replicates. Positive cases were significantly associated with late-stage disease (P < 0.001), larger tumors (P = 0.002), distant metastasis (P < 0.001), and disease progression (P < 0.001). For monitoring treatment response and tumor burden, decreased methylation levels were observed in patients responding well to treatment, whereas increased levels were noted in cases of cancer progression or prior to metastasis.

Conclusions

Overall, detecting methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 in plasma offers a novel, accurate, and noninvasive method for monitoring breast cancer progression.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13148-025-01939-4.

Keywords: Breast cancer, GCM2, TMEM240, Circulating cell-free DNA, Methylation biomarker

Background

Breast cancer has now overtaken lung cancer as the world’s most commonly diagnosed cancer and is the second leading cause of cancer death among women worldwide [1–3] while also significantly contributing to global cancer mortality rates. International efforts are crucial for addressing the escalating burden of this disease, particularly in transitioning countries where the incidence of breast cancer is rapidly increasing and mortality rates remain high [4]. That said, breast cancer metastases, not the primary tumor, are responsible for more than 90% of cancer-related deaths [5]. Nearly 20–30% of patients with early-stage disease develop metastases over the disease course [6]. Advanced breast cancer, in which the cancer has metastasized to various organs, may not be completely curable with currently available treatments [7], primarily because of the development of multidrug resistance, which hampers treatment and prognosis [7].

Tumorigenesis involves the initiation and promotion of molecular abnormalities, including the activation of oncogenes and the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) [8]. The initiation and progression of cancer, which is conventionally considered a genetic disease, involve epigenetic abnormalities [9] such as DNA methylation defects and aberrant covalent histone modifications, which occur in all cancers throughout the natural history of tumor formation. These changes are detectable during early onset, progression, and ultimately recurrence and metastasis [9, 10].

There is an urgent clinical need for a relatively noninvasive system, such as blood testing, for monitoring treatment response and disease progression during cancer treatment. Cancer antigen 15-3 (CA15-3) levels are widely assessed for the early detection of recurrent breast cancer in current clinical practice. However, analyzing only CA15-3 as a tumor marker is insufficient for monitoring patients with breast cancer after surgical treatment [11]. Although clinically useful for some patients with metastatic breast cancer, the CA15-3 level has a sensitivity of only 60–70% [12–16]. Even the simultaneous use of serum markers CA15-3 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) results in diagnosing metastasis in up to 60–80% of patients with breast cancer early [13–17], while according to our unpublished data, the simultaneous use of both CA15-3 and CEA resulted in the early diagnosis of metastasis in less than 50% of patients with breast cancer. No dynamic monitoring system is currently available for accurately measuring the complete treatment response and predicting recurrence in current clinical practice. Circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in plasma can be used for the noninvasive sampling of cancer cells obtained from patients with breast cancer [18]. Cells (both cancerous cells and cells in the tumor microenvironment) release cfDNA through a combination of apoptosis, necrosis, and active secretion. Multiple genetic and epigenetic alterations are found in cfDNA [19]. For example, hypermethylated circulating glial cells missing transcription factor 2 (GCM2) has been reported as a noninvasive breast cancer-specific biomarker in both TCGA data and Taiwanese breast cancer patients, across all major breast cancer subtypes [20]. The GCM2 gene encodes a transcription factor that is required for parathyroid development. Mutation of the C-terminal conserved inhibitory domain of GCM2 can cause primary hyperparathyroidism [21]. Following surgery in breast cancer patients, there is a significant decrease in circulating methylated GCM2, indicating that circulating GCM2 levels in breast cancer patients could serve as novel biomarkers for posttreatment monitoring, aiding in the detection of residual tumors [20]. Additionally, analysis of data from Taiwanese individuals in the TCGA database revealed that hypermethylation of transmembrane protein 240 (TMEM240) is associated with poor hormone therapy response in patients with breast cancer [22]. TMEM240 encodes a transmembrane protein primarily found in the brain and cerebellum. In studies from various countries, including France, Germany, the Netherlands, Colombia, Japan, and China, mutations in TMEM240 have been linked to spinocerebellar ataxia 21 (SCA21), leading to cognitive impairment and movement disorders, suggesting that the pathogenic mechanism underlying SCA21 may involve early gliosis and lysosomal impairment caused by mutant TMEM240 [23–27]. Hypermethylation of TMEM240 has also been observed in colorectal cancer [28, 29]. Previously reported findings have indicated that circulating methylated TMEM240 levels gradually decrease in Taiwanese patients with nonprogressive breast cancer and increase in those with disease progression, demonstrating a remarkable predictive accuracy of 96.1%. Notably, this predictive accuracy surpassed that of CA15-3 and CEA when assessing disease progression within a cohort of 57 patients [22]. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the potential of the simultaneous plasma detection of methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 in improving the prediction of residual disease and tumor progression in breast cancer patients. This evaluation was conducted with a large and highly diverse sample size, encompassing various racial groups.

Methods

Study design

A total of 38, 114, and 14 patients from TMU-H, TMU-SH, and Dx Biosamples, respectively, were selected to form the training group (earlier collection), while the validation group (latter collection) included 53, 152, 92, and 28 patients from TMU-H, TMU-SH, Precision for Medicine LLC, and Audubon Bioscience Co, respectively.

In addition to traditional cutoff determination and validation, this grouping facilitated the development of a monitoring model. We further used the Monte Carlo replicates module in R software to automatically partition the patient dataset into training (70%) and validation (30%) sets. The prospective and retrospective data were used to determine and validate the cutoff for the monitoring model. The designs of all the studies are detailed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study design and patient grouping in the establishment of the monitoring model

Patients and plasma collection

In a prospective study conducted in Taipei, Taiwan, we enrolled a total of 414 patients between 2016 and 2023. These patients were carefully monitored and included individuals with various stages of breast cancer, ranging from Stage 0 to Stage IV. The study participants were recruited from the Breast Medical Center at Taipei Medical University Hospital (TMU-H), as well as the Breast Medical Center and Division of Hematology/Oncology at Shuang Ho Hospital (TMU-SH). A total of 48 breast cancer patients were lost to follow-up after diagnosis. Additionally, 13 breast cancer patients withdrew from the clinical trial because of difficulties in or refusal of drawing an additional tube of blood.

Blood sample collection, cfDNA extraction, and cfDNA methylation analysis were conducted according to a predefined schedule, which included time points before surgery, 24 h after surgery, every 3 months during the initial 2 years posttreatment, and every 6 months during the subsequent 3 years. In addition to blood samples, clinical biomarkers and medical imaging data, including the levels of CA15-3 and CEA, and data from MRI, abdominal ultrasound, CT scans, bone scans, and breast ultrasound, were collected to monitor patients’ health and treatment progress comprehensively. The pathological diagnoses of these patients were confirmed through microscopic examination of patient specimens by two researchers. Sections of cancerous tissue and corresponding noncancerous tissues were assessed by a senior pathologist. Clinical data, including variables such as age, sex, tumor type, TNM tumor stage, menopausal state, and the statuses of tumor markers estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), were prospectively gathered from the medical records of TMU-H and TMU-SH. Prior to the collection of clinical data and samples, written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All clinical data, including the diagnosis of breast cancer, were obtained and confirmed by licensed medical doctors. The diagnostic assessments were further reviewed by Dr. Chin-Sheng Hung to ensure clinical accuracy.

We also conducted a retrospective study involving 134 plasma samples from Western populations. Among these, 120 samples were collected from US breast cancer patients, originating from two distinct sources: 92 from Precision for Medicine LLC. in Norton, MA, USA, and 28 from Audubon Bioscience Co. in New Orleans, LA, USA. An additional 14 plasma samples were obtained from Eastern European breast cancer patients through Dx Biosamples LLC in San Diego, CA, USA. The clinical characteristics of the enrolled breast cancer patients in the training and validation cohorts are shown in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Circulating cell-free DNA extraction

Blood samples were collected via Streck BCT cfDNA tubes (Streck, La Vista, NE, USA), and a double centrifugation process was employed to isolate the plasma. cfDNA was extracted with the EG-Breast Blood Test-P1, EG cfDNA extraction Kit (EG BioMed Co. Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. The EG-Breast Blood Test-P1 is a qualitative qPCR-based assay designed to detect methylated cfDNA in human plasma using the EG BioMed testing system. It consists of three integrated components: (A) the EG cfDNA Extraction Kit, used to isolate cfDNA from plasma samples; (B) the EG Bisulfite Conversion Kit, used to perform bisulfite conversion and purification of the extracted cfDNA; and (C) the EG-breast blood test kit, used to detect and analyze methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 through methylation-specific PCR. First, one mL of plasma sample is incubated with proteinase K, SDS and magnetic beads for each reaction. After shaking, the tubes are centrifuged, and the magnetic beads are separated. The supernatant is carefully removed, and Extr-Wash is added to resuspend the magnetic beads. After another centrifugation and magnetic separation, ethanol is added, and the process is repeated. The samples are air-dried and transferred into nonmagnetic racks, and Extr-Elution is added to each microtube. After vortexing and spinning, the eluate containing the extracted cfDNA is transferred into fresh microtubes. After cfDNA extraction, the magnetic bead-containing microtubes are discarded, and the eluted cfDNA solution is cooled for subsequent processing. The entire volume is then used for the sodium bisulfite conversion reaction.

Sodium bisulfite conversion of cfDNA

Sodium bisulfite conversion was conducted with the EG-Breast Blood Test-P1, EG bisulfite conversion kit (EG BioMed Co. Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. The sodium bisulfite conversion process involves incubating the mixture with a Bis-HQ solution. The Bis-HQ solution contains hydroquinone and sodium bisulfite and is used to protect DNA from degradation during the bisulfite conversion process. Next, magnetic beads and binding buffer are added, and the mixture is incubated. Then, microtubes containing the mixture are placed on a magnetic rack to separate the magnetic beads from the supernatant. Bis-Wash solution is added to each microtube, and the magnetic beads are resuspended on a shaker. After another round of magnetic separation, Bis-D solution is added to each microtube, and the magnetic beads are resuspended again. Following multiple wash steps and air-drying on a heater, the samples are transferred to nonmagnetic racks. Bis-Elution solution is added to each microtube, and the magnetic beads are resuspended. The eluate, containing bisulfite-converted DNA, is collected and transferred to fresh microtubes. The bisulfite-converted DNA mixture is then cooled before proceeding to the next step of qPCR analysis.

TaqMan quantitative methylation-specific PCR

After DNA bisulfite conversion, the cfDNA methylation levels of GCM2 and TMEM240 were measured via TaqMan quantitative methylation-specific PCR (QMSP) with an EG-breast blood test kit and a Cobas LightCycler z480 (Roche, Germany) [20, 22]. The beta-actin (ACTB) gene was used as an internal control for input cfDNA. The QMSP conditions were as follows: preincubation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles of amplification at 95 °C for 10 s and at 60 °C for 10 s. The entire bisulfite-converted cfDNA sample was equally divided into nine aliquots, with three replicates each for GCM2, TMEM240, and ACTB PCR assays. The specificity of the GCM2 and TMEM240 methylation end products was confirmed by bisulfite amplicon Sanger sequencing (Fig. S1). The primer and probe sequences, along with the reaction conditions used for the TaqMan qMSP assays, are listed in Table S3. These primers and probes were specifically designed to target regions that exhibit low methylation in normal tissue and high methylation in tumor tissue, as shown in our previous studies [22, 28, 30].

Quality assessment of cfDNA methylation assays

The adequacy and quality of cfDNA input for each assay are evaluated using a methylation-specific PCR (MSP-PCR) assay targeting the internal control gene ACTB. The primers and probe for ACTB are designed to amplify both methylated and unmethylated cfDNA, serving as an endogenous control for assessing both cfDNA input quantity and extraction efficiency.

Based on prior clinical validation studies using plasma samples, a crossing point (Cp) value of ACTB below 35.5 is defined as the threshold for acceptable extraction efficiency. Cp values exceeding 35.5 indicate reduced cfDNA recovery, and values above 36.0 are generally associated with failed amplification of target methylation markers. Therefore, a Cp value of ACTB < 35.5 is required to ensure reliable assay performance.

Each assay run also includes an independent extraction positive control (ePC), which undergoes the complete workflow alongside the test samples. The ACTB Cp value of the ePC must likewise be below 35.5 to validate the extraction and assay quality for that batch.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to compare circulating GCM2 methylation level, circulating TMEM240 methylation level, and clinical data, including age, sex, tumor type, TNM tumor stage, breast cancer subtype, and tumor status between groups. Comparisons of the hypermethylation and hypomethylation curves were performed with the log-rank test. p values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. In addition to accuracy, other commonly used measures for evaluating classification, such as the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, false positive rate, and false negative rate, are also reported.

Creation of a monitoring model with the Monte Carlo replicates module

To further evaluate the overall performance of the circulating GCM2 methylation level, circulating TMEM240 methylation level, and internal control ACTB level in detecting disease progression, we used Su and Liu’s biomarkers [31]. This method can also accommodate an imbalanced distribution of outcomes resulting from the low prevalence of disease progression in the population. In our study, we randomly split the data into two datasets at a 7:3 ratio. Specifically, we used 70% of the original data to train a classification model and find the optimum threshold (i.e., that which led leading to the maximum AUC) for the classification. Then, with the optimum threshold and the estimated classification model, we used the remaining 30% of the data to examine how consistent the prediction and the true outcomes were for validation. We repeated this procedure 1,000 times and reported the average results. All the analyses were performed in R.

Results

Determining the cutoff value for detecting circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 in plasma for predicting tumor progression

To assess the cutoff value for detecting circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 in plasma for predicting tumor progression, we employed a training group comprising 14 Eastern European and 152 Taiwanese breast cancer patients. Of these 166 breast cancer patients, 13.3% experienced tumor recurrence or distant metastasis. Within this cohort, 56.0% of the participants were younger than 55 years, and all were female. Notably, 92.8% of the patients were diagnosed with the IDC subtype of breast cancer. A significant portion (77.1%) of the participants had stages II and III breast cancer, emphasizing the need for continuous monitoring to detect potential cancer progression events (Table S1).

Cutoff thresholds for GCM2 and TMEM240 were determined using Cp values in relation to clinical outcomes. A sample was classified as “POSITIVE” if it met any of the following criteria:

GCM2: Cp value < 40.0 in at least one replicate and TMEM240: Cp value < 41.0 in at least one replicate; or

TMEM240: Cp value < 41.0 in at least two replicates.

Samples not meeting these criteria were classified as “NEGATIVE.” These same thresholds were subsequently applied to the validation cohort to confirm their robustness and predictive utility.

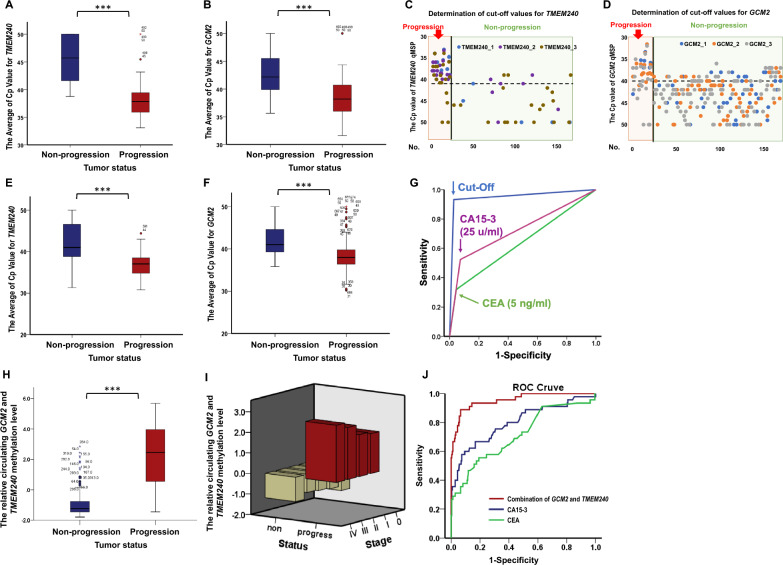

By analyzing these samples, we found that the average Cp values in both the TMEM240 and GCM2 QMSP results were lower in the progression group than in the nonprogression group (Fig. 2A and B). A two-dimensional scatter plot was subsequently generated to visualize the data and determine the cutoff values. Subsequent analysis revealed that the progression group tended to have a TMEM240 Cp value lower than 41.0 and a GCM2 Cp value lower than 40.0 Conversely, in the nonprogression group, the Cp value of TMEM240 tended to be greater than 41.0, whereas the Cp value of GCM2 tended to be greater than 40.0 (Fig. 2C and D).

Fig. 2.

Distribution and performance of TMEM240 and GCM2 methylation levels in breast cancer progression. In the training group, box plots compare the average Cp values of TMEM240 (A) and GCM2 (B) between nonprogression and progression groups (166 subjects). Scatter plots display cfDNA methylation levels for TMEM240 (C) and GCM2 (D), showing progression patients in the orange area (left) and nonprogression patients in the green area (right). The Y-axis represents Cp values from qPCR, and the X-axis corresponds to individual patient numbers, with data based on three technical replicates per patient. In the validation group, bar charts show the average Cp values of TMEM240 (E) and GCM2 (F) for nonprogressive (left) and progressive (right) patients (325 subjects), with differences evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U test (***, p < 0.001). (G) ROC curves are based on classifications using the defined cutoff value for combined circulating GCM2 and TMEM240 methylation levels and are compared with CA15-3 and CEA levels for monitoring breast cancer progression. (H) Bar chart displaying combined GCM2 and TMEM240 methylation levels, calculated via the second Monte Carlo replicates module using Su and Liu’s method. (I) Methylated cfDNA of GCM2 and TMEM240 in plasma across different stages at diagnosis. (J) ROC curves further compare the predictive performance of combined GCM2 and TMEM240 methylation levels against CA15-3 and CEA levels in monitoring breast cancer progression

According to these cutoff values, the EG-breast blood test demonstrated an accuracy of 97.0%, a sensitivity of 81.8%, a specificity of 99.3%, a positive predictive value (PPV) of 94.7%, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 97.3%.

Clinical validation of circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 levels for monitoring recurrence or progression in breast cancer patients

To further evaluate whether the combined detection of circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 could be used to monitor for recurrence or progressive disease in breast cancer patients according to the defined cutoff values, we validated the system with the data from 120 breast cancer patients from the USA and 205 patients from Taiwan. Of the 325 patients, 66 (20.3%) experienced tumor recurrence or distant metastasis. Among the 259 patients without cancer progression, 55 (21.2%) showed no detectable methylated GCM2 in their plasma across all three PCR replicates, and 200 (77.2%) had no detectable methylated TMEM240. In contrast, among the 66 patients with recurrence or metastasis, only 4 (6.0%) had no detectable methylation of either GCM2 or TMEM240 in all three replicates.

In this population, the proportions of individuals older than 55 years and those younger than 55 years were roughly equal. Similar to the training group, over 90% of the patients in the validation group were diagnosed with the IDC subtype of breast cancer. Additionally, 75.5% of these individuals were diagnosed with stage II or III breast cancer, indicating a clinical need for tracking potential progression in breast cancer patients (Table S2).

The raw data of the validation set were exported to an Excel file, and a box chart was created to visualize the average Cp values for TMEM240 and GCM2 (Fig. 2E and F). Overall, in the progression group, the Cp values of TMEM240 and GCM2 were lower than 40.0, whereas in the nonprogression group, the Cp value of TMEM240 was greater than 40.0.

Analysis of the performance of these biomarkers revealed that the combined detection of circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 via reagent analysis outperformed the levels of CA15-3 and CEA in terms of sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV, NPV, and AUC; notably, the proposed system demonstrated a greater sensitivity for the progression group (Table 1). The combination of circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 demonstrated an accuracy of 95.1%, a sensitivity of 89.4%, a specificity of 96.5%, a PPV of 86.8%, an NPV of 97.3%, and an AUC of 0.930. In comparison, use of the serum markers CA15-3 and CEA, commonly used to detect recurrence and metastasis in breast cancer patients in clinical practice, exhibited lower sensitivity (54.3 and 32.6%, respectively) and AUC values (0.737 and 0.639, respectively) (Fig. 2G).

Table 1.

Performance of the combined detection of circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 in the validation set

| Test | Na | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||||||

| GCM2 & TMEM240 | 325 | 89.4 | 96.5 | 95.1 | 86.8 | 97.3 | 0.930 |

| CA15-3 | 291 | 54.3 | 93.1 | 86.9 | 59.5 | 91.6 | 0.737 |

| CEA | 293 | 32.6 | 95.1 | 85.3 | 55.6 | 88.3 | 0.639 |

| Western Patients | |||||||

| GCM2 & TMEM240 | 95 | 92.3 | 89.3 | 90.5 | 85.7 | 94.3 | 0.904 |

| CA15-3 | 74 | 55.2 | 75.6 | 67.6 | 59.3 | 72.3 | 0.654 |

| CEA | 75 | 34.5 | 89.1 | 68.0 | 66.7 | 68.3 | 0.617 |

aFor some categories, the number of samples (n) was lower than the overall number analyzed because some clinical data of blood samples were unavailable

In addition, the performance of the combined detection of circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 in a Western population was evaluated in this clinical study. Previous studies conducted in white populations have reported consistent findings, specifically that the combined detection of circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 maintains a similar accuracy and sensitivity across different races. In this study, the combined detection of circulating methylated GCM2 and the TMEM240 demonstrated an accuracy of 90.5%, a sensitivity of 92.3%, a specificity of 89.3%, a PPV of 85.7%, an NPV of 94.3%, and an AUC of 0.904 for the Western population. In comparison, the use of markers CA15-3 and CEA yielded lower sensitivity (55.2 and 34.5%, respectively) and AUC values (0.654 and 0.617, respectively) (Table 1).

Analysis of the monitoring model created by the Monte Carlo replicates module with Su and Liu’s classification method

To further validate the effectiveness of the combined detection of circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 in plasma and create a real-time monitoring model, we employed Su and Liu’s classification method [31], an AUC-based classification approach suitable for multiple biomarkers. The average Cp value of GCM2, average Cp value of TMEM240, and average Cp value of ACTB were included in the model for calculation. This method can effectively handle imbalanced outcome distributions, which often occur due to the low prevalence of disease in the population. To ensure the robustness of our evaluation, we randomly divided the data into two sets at a 7:3 ratio. Specifically, 70% of the data were used to train the classification model and determine the optimal threshold (i.e., that which resulted in the maximum AUC) for classification. Using the optimal threshold and the estimated classification model, we subsequently examined the consistency between the predictions and true outcomes using the remaining 30% of the data. We repeated this procedure 1,000 times and reported the average results. All the processes for grouping and analysis were conducted in R.

The results demonstrated that Su and Liu’s method consistently exhibited high sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy across the 1,000 replicates. Specifically, the classification model generated using the training data exhibited an average sensitivity of 0.957, an average specificity of 0.903, and an average accuracy of 0.915. Furthermore, when the classification model was applied to the test data, the results showed an average sensitivity of 0.928, an average specificity of 0.895, and an average accuracy of 0.903 across the 1,000 replicates (Table 2). To investigate the correlation between elevated methylation levels of circulating TMEM240 and GCM2 and clinical parameter variations, patients were categorized into high (positive) and low (negative) methylation groups using cutoff values determined by the Monte Carlo replicates module and the method developed by Su and Liu. The positive patients were significantly more likely to be older (P = 0.002), have late-stage disease (P < 0.001), have larger tumors (P = 0.002), have distant metastasis (P < 0.001), and have disease progression (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Performance of Combined Methylation Markers Using Su and Liu’s Method

| Parameter | Training Set (70%) | Validation Set (30%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nonprogressive (sample size, n) | 182 | 77 |

| Progressive (sample size, n) | 52 | 23 |

| Accuracy | 0.915 | 0.903 |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | 0.964 | 0.912 |

| Sensitivity | 0.957 | 0.928 |

| Specificity | 0.903 | 0.895 |

| False Positive Rate | 0.097 | 0.105 |

| False Negative Rate | 0.043 | 0.072 |

Table 3.

Association of clinical parameters with different levels of circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 in patients

| Characteristics | All N (%)2 |

Model by Su and Liu’s method1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive3 | |||

| Overall | 340 | (100.0) | 243(71.1) | 96(28.3) |

| Age | ||||

| < 55 y/o | 170 | (51.1) | 132(77.6) | 38(22.4) |

| > 55 y/o | 163 | (48.9) | 101(62.0) | 62(38.0)** |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 330 | (99.4) | 233(70.6) | 97(29.4) |

| Male | 2 | (0.6) | 0(0.0) | 2(100.0)* |

| Histological type | 238 | |||

| IDC | 220 | (92.4) | 180(81.8) | 34(18.2) |

| ILC | 9 | (3.8) | 6(66.7) | 3(33.3) |

| Mucinous | 5 | (2.1) | 5(100.0) | 0(0.0) |

| Mixed | 4 | (1.7) | 3(75.0) | 1(25.0) |

| Stage at diagnosis | 323 | |||

| 0 | 1 | (0.3) | 1(100.0) | 0(0.0) |

| I | 48 | (14.9) | 42(87.5) | 6(12.5) |

| II | 190 | (58.8) | 142(74.7) | 48(25.3) |

| III | 56 | (17.3) | 40(67.9) | 16(32.1) |

| IV | 28 | (8.7) | 10(32.1) | 18(67.9)*** |

| Tumor size at diagnosis | ||||

| < 2 cm | 97 | (31.3) | 78(80.4) | 19(19.6) |

| > 2 cm and < 5 cm | 178 | (57.4) | 130(73.0) | 48(27.0) |

| > 5 cm | 21 | (6.8) | 10(47.6) | 11(52.4)** |

| On the chest wall/skin | 14 | (4.5) | 8(57.1) | 6(42.9) |

| Lymph nodes at diagnosis | 319 | |||

| 0 | 155 | (48.6) | 117(75.5) | 38(24.5) |

| At least one | 164 | (51.4) | 111(67.7) | 53(32.3) |

| Metastasis at diagnosis | 314 | |||

| No | 278 | (88.5) | 216(77.7) | 62(23.3) |

| Yes | 36 | (11.5) | 9(25.0) | 27(75.0)*** |

| Subtype | ||||

| luminal A type | 103 | (44.0) | 91(88.3) | 12(11.7) |

| luminal B type | 78 | (33.3) | 64(82.1) | 14(17.9) |

| HER2 type | 25 | (10.7) | 19(76.0) | 6(24.0) |

| Basal-like (TNBC) | 28 | (12.0) | 21(75.0) | 7(25.0) |

| Tumor status | 340 | |||

| Nonprogressive | 259 | (76.2) | 227(87.6) | 32(12.4) |

| Progressive | 81 | (23.8) | 7(8.6) | 74(91.4)*** |

1Data compared with the Pearson X2 test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001

2For some categories, the number of samples (n) was lower than the overall number analyzed because clinical data were unavailable

3Patients were classified as positive or negative based on a cutoff value determined using a logistic regression model developed according to the methodology of Su and Liu, with 5,000 bootstrap replicates

Su and Liu-based logistic regression model for monitoring disease progression using methylated cfDNA in breast cancer

To evaluate relative methylation levels in individual patients, we developed a progression scoring model based on the methylation status of selected markers. Using a validation cohort, we applied a logistic regression model based on the methodology described by Su and Liu, incorporating 5,000 bootstrap replicates. Only models achieving 90% accuracy and false positive and false negative rates below 10% were retained, resulting in a total of 1,748 models. The average regression coefficients derived from these models are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Regression coefficients and cutoff value for cfDNA methylation-based progression score

| GCM2 | TMEM240 | IC_A | Cutoff Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bootstrap Coefficient | − 0.01973888 | − 0.19878571 | − 0.1467272 | − 17.52127 |

| Bootstrap Standard Error | 0.0067762 | 0.0120404 | 0.045404 | 1.941738 |

The scoring formula is as follows:

Score = −0.01973888 GCM2—0.19878571 TMEM240—0.14672717 IC_A + 17.52127.

Decision Rule:

If Score > 0, the sample is classified as progression.

If Score 0, the sample is classified as no progression.

These "relative methylation levels" reflect the weighted contribution of each marker to the progression score. While the formula can be updated as more data become available, we expect future coefficient estimates to remain within the confidence intervals established by the bootstrap standard errors.

A box chart was created to visualize the relative methylation levels of circulating TMEM240 and GCM2, which were calculated via the Monte Carlo replicates module and analyzed with Su and Liu’s classification method (Fig. 2H). To analyze the methylated cfDNA of GCM2 and TMEM240 in plasma across different stages at diagnosis, patients with disease progression exhibited high levels of methylated cfDNA of GCM2 and TMEM240 across all stages. In contrast, patients without disease progression showed low levels of methylated cfDNA of these biomarkers regardless of the stage (Fig. 2I). Overall, in the progression group, the relative methylation levels of TMEM240 and GCM2 were greater than those in the nonprogression group. The AUC of the model was 0.930. In comparison, the use of markers CA15-3 and CEA exhibited lower AUCs (0.737 and 0.639, respectively) (Fig. 2J).

Monitoring the treatment response and tumor burden of breast cancer patients

We hypothesized that tumor burden in breast cancer patients could be dynamically assessed by monitoring circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 following treatment. To evaluate this, we monitored their methylation levels every 3–6 months posttreatment, alongside routine blood tests for CA15-3 and CEA. Patient H205, who had a good outcome, showed a gradual decrease in the abnormal methylation of GCM2 and TMEM240 (Fig. 3A) in their plasma after treatment. In contrast, in the plasma of patient SH524, there was a clear and gradual elevation in the abnormal methylation levels of GCM2 and TMEM240 prior to the development of distant metastasis (Fig. 3B). The plasma of patient H223 demonstrated increases in the abnormal methylation levels of circulating GCM2 and TMEM240 as her breast cancer progressed and decreases when the patients receive adequate treatment (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Real-time monitoring of circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 in patients with breast cancer following treatment. Breast cancer patients with a good prognosis (A), with distant metastasis (B), and with distant metastasis who subsequently received adequate treatment (C). The Y-axis represents the relative methylation level, which was calculated with the Monte Carlo replicates module and analyzed with Su and Liu’s method. The X-axis represents months after treatment

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that circulating methylated GCM2 and TMEM240 provide high diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity for monitoring breast cancer progression. Compared to conventional serum markers CA15-3 and CEA, our assay significantly improves detection rates, particularly in early progression. This is consistent with prior literature emphasizing the limitations of protein-based biomarkers and the growing relevance of cfDNA methylation markers in cancer surveillance [12–17, 20, 32–34]. Prior studies have shown the potential of methylation-based assays for early detection and recurrence monitoring across various cancers, including breast, colorectal prostate, and lung cancer [35–37]. Our results extend these findings by demonstrating that the combination of GCM2 and TMEM240 methylation signatures achieves superior performance not only in Taiwanese patients but also in a Western cohort. This highlights the cross-ethnic applicability of our biomarkers, addressing a critical gap in cfDNA biomarker generalizability. Additionally, GCM2 is frequently hypermethylated across both histological subtypes—such as invasive ductal carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma—and molecular subtypes, including luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched, and triple-negative breast cancer (Fig. S2). Early detection of an increase in tumor burden in patients with cancer recurrence and distant metastasis is crucial for timely treatment. As a key element of follow-up care and surveillance after the completion of primary breast cancer treatment, early detection aims to improve survival by identifying and treating recurrent disease while it is still potentially curable. This approach enables more effective salvage surgery and treatment, increasing the likelihood of a successful outcome [38], while also helping prevent the spread of cancer cells to multiple organs, keep the tumor in a manageable state, and potentially extend patient survival. When employed with a noninvasive approach, early detection not only reduces patient discomfort and inconvenience but also facilitates frequent testing. This increased comfort and convenience result in greater risk tolerance among patients, as they are more willing to accept potential risks associated with the test owing to the substantial benefits of early detection.

In the realm of breast cancer progression diagnostics, imaging techniques frequently reveal ambiguous lesions that may hinder accurate diagnosis. Blood tests can complement imaging techniques, enhancing diagnostic precision. However, the commonly used CA15-3 and CEA markers lack the necessary sensitivity [12–17], and there is a consensus against routine supplemental imaging for asymptomatic patients due to insurance coverage limitations. The emergence of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)-based minimal residual disease (MRD) tests holds great promise for enhancing sensitivity in detecting disease recurrence or progression. In our study, although dynamic changes in methylation appeared to parallel clinical progression, rather than consistently precede it, some early signals were noted. Because our cutoff values were established based on imaging-confirmed progression, biomarker positivity in our current model is aligned with radiologic findings. However, as shown in Fig. 3B and C, we observed that methylation levels of GCM2 and TMEM240 began to rise prior to radiographic evidence of progression. While the increase was modest, the upward trend—particularly the slope—suggests that methylation dynamics may serve as an early indicator of disease progression. Further prospective studies with predefined time points and longitudinal sampling will be essential to rigorously evaluate the lead time of these methylation markers in comparison to conventional clinical tools.

Surgical interventions for patients with breast cancer often result in postoperative artifacts, particularly with the increasing use of oncoplasty, which complicates imaging interpretation. This can lead to unnecessary biopsies, creating anxiety for patients. A highly sensitive blood test, such as the one we are developing, could mitigate these issues by providing a noninvasive monitoring tool, thus offering convenience and reassurance to postsurgical patients.

In clinical practice, for patients with stage II or III breast cancer, the detection of recurrence or metastasis through blood tests remains challenging, often requiring expensive procedures such as CT, MRI scans or bone scans to obtain a definitive diagnosis. In countries such as the USA, where such procedures are expensive, they are not routinely performed and are typically reserved for patients with overt symptoms. By this stage, however, it is likely that the disease has progressed to a point where therapeutic intervention may not be sufficiently effective. A sensitive blood test could address these limitations, providing an early and cost-effective means of monitoring for recurrence or metastasis, thus facilitating prompt and potentially life-saving treatments. Liquid biopsies are integral to this process, providing a noninvasive, real-time method that can be repeatedly used for thorough monitoring. Among various epigenetic markers, cfDNA methylation is the most extensively studied. The potential of the level of DNA methylation as a diagnostic indicator has been explored by examining the features of 5mC [39]. Sequencing-based, PCR-based, and microarray-based methods are commonly employed to detect these methylation changes in cfDNA. Recent research has revealed distinctive methylation patterns between cancer samples and noncancerous samples, reinforcing the role of DNA methylation as a valuable tool for detecting cancer [32–34].

However, DNA methylation assays have some limitations. When using EDTA blood collection tubes, it is essential to process samples within two hours to prevent leukocyte lysis and the release of genomic DNA (gDNA), which can compromise the accuracy of cfDNA-based analyses [40]. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), a tumor-derived fraction of cfDNA, is typically present at low concentrations in plasma—often representing less than 1% of total cfDNA. In breast cancer, the proportion of methylated ctDNA is even lower, generally comprising less than 5% of total cfDNA [37]. The abundant background gDNA resulting from blood cell lysis caused by improper use of the assay has become a major obstacle to accurately measuring cfDNA [41]. While the use of cfDNA-specific collection tubes allows blood to be stored at room temperature for more than three days, these tubes are sixty times more expensive than standard EDTA tubes. Moreover, the capacities of blood collection tubes differ considerably in the preservation of blood samples. Therefore, suitable blood collection devices should be selected to minimize gDNA contamination and standardize blood sample processing to achieve more accurate and reliable clinical analysis of cfDNA [41], which contain blood stabilization reagents (preservation solutions) reported to inactivate virus activity [42], possibly significantly reducing biohazard risks compared with those of regular blood samples.

Additionally, cfDNA fragments are typically 166 bp long, matching the combined length of nucleosome-wrapped and linker DNA and indicating specific nuclease cleavage, and are released from cells through processes such as apoptosis. The quality of cfDNA can be affected by various preanalytical factors, such as the collection and storage method. Research shows that while these factors do not affect the size of cfDNA, they can influence its fragmentation patterns and end sequences, demonstrating the complexity of cfDNA analysis [43]. Therefore, the single-stranded, fragmented, and fragile nature of cfDNA, as well as the lack of protein wrapping and protection due to its origination from apoptotic or necrotic cells, complicate storage and increase the complexity of analysis.

Detecting cfDNA in plasma presents significant challenges because of its inherent characteristics. In healthy individuals, cfDNA is present in low quantities, approximately 0–10 ng/ml in plasma, whereas in breast cancer patients, the concentration increases to approximately 15 ng/ml [44]. Additionally, cfDNA has a short half-life, ranging from 16 min to 2.5 h, depending on various physiological and pathological factors [45]. These properties pose substantial difficulties in accurately detecting and quantifying cfDNA. The detection of tumor-derived cfDNA is technically challenging due to its low abundance in the bloodstream and its rapid degradation. This challenge is compounded by the release of cfDNA from noncancerous cells, which introduces substantial background noise and interferes with the identification of tumor-specific signals. These issues are particularly pronounced in early-stage cancer and in patients with minimal residual disease (MRD) following treatment, where tumor-derived cfDNA may be present at extremely low levels [46]. To overcome these limitations, highly sensitive and specialized analytical methods—such as digital PCR (dPCR), methylation-specific PCR (qMSP), and targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) incorporating unique molecular identifiers (UMIs)—are required to enable accurate detection and quantification of tumor-associated cfDNA [30, 47, 48]. In addition, the use of IVD-grade reagent kits developed in a GMP-certified facility is strongly recommended prior to clinical application. These kits are produced under strict quality control to ensure lot-to-lot consistency, stability, and reproducibility, thereby supporting reliable and accurate cfDNA analysis across different runs and time points. Furthermore, standardized operating procedures implemented through automated liquid handling systems help reduce variability and improve assay robustness, addressing the inherent challenges of cfDNA handling and enabling more consistent clinical performance.

Additionally, hypermethylation of TMEM240 has been shown to lead to the proliferation of breast cancer and colorectal cancer cells [22, 28]. Gene-specific demethylating approaches targeting TMEM240, such as CRISPR/dCas9-TET1-mediated DNA demethylation technology [49], may hold potential for treating patients with methylated circulating TMEM240 cfDNA. These methylation markers could also serve as companion diagnostics to guide therapeutic decisions.

The model developed in this study has potential for aiding in the development of personalized treatment plans by helping to identify patients who would benefit most from therapy and allow for better monitoring of treatment response. This targeted approach would enhance treatment efficacy and optimize breast cancer management.

Conclusions

The model developed in this study demonstrated superior accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV compared to the clinically commonly used markers CA15-3 and CEA. Additionally, the methylation levels of GCM2 and TMEM240 can also reflect the treatment status of breast cancer patients in real time. Therefore, detecting these methylation biomarkers in plasma provides a novel, accurate, and noninvasive method for monitoring breast cancer progression.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- GCM2

Glial cells missing transcription factor 2

- TMEM240

Transmembrane Protein 240

- ACTB

Beta-actin

- SCA21

Spinocerebellar ataxia 21

- CA15-3

Cancer antigen 15-3

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- cfDNA

Circulating cell-free DNA

- QMSP

Quantitative methylation-specific real-time polymerase chain reaction

- qPCR

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- TNBC

Triple-negative breast cancer

- TCGA

The cancer genome atlas

Author contributions

HTS and RKL designed the studies. CS Hung, PYW, CMS and LML collected and provided the clinical samples. PYW, KYC and CS Han performed the experiments. HTS, WWH, and RKL analyzed and interpreted the data. HTS, RKL and KYC drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NSC 113–2321-B-038 -006 from the National Science and Technology Council (Republic of China, Taiwan) and A-111-115 from EG BioMed Co., Ltd. (Republic of China, Taiwan).

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study has been approved by the Taipei Medical University—Joint Institutional Review Board and the Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Part authors are employees of EG BioMed Co. Ltd. and EG BioMed US Inc., whose company funded this study. HTS, RKL are employees of EG BioMed Co. Ltd. and EG BioMed US Inc., HTS, CMS, CSH and RKL hold stock in EG BioMed Co. Ltd. and EG BioMed US Inc., and report other support from EG BioMed Co. Ltd. and EG BioMed US Inc., during the conduct of the study. In addition, RKL has multiple patents in the field of cancer detection pending to EG BioMed Co. Ltd. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chin-Sheng Hung and Hsieh-Tsung Shen contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

References

- 1.Taiwan Health Promotion Administration: Cancer Registry Annual Report, 2017. Taiwan: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2019.

- 2.Statistics on causes of death in China in 2017 [https://www.mohw.gov.tw/cp-16-48057-1.html]

- 3.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, Mafra A, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2022;66:15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science. 2011;331:1559–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu W. Xu b overcoming resistance to endocrine therapy in hormone receptor-positive human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HR(+)/HER2(-)) advanced breast cancer: a meta-analysis and systemic review of randomized clinical trials. Front Med. 2021;15:208–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gote V, Nookala AR, Bolla PK. Pal D drug resistance in metastatic breast cancer: tumor targeted nanomedicine to the rescue. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekido Y, Fong KM, Minna JD. Progress in understanding the molecular pathogenesis of human lung cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1378:F21–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werner RJ, Kelly AD, Issa JJ. Epigenetics and precision oncology. Cancer J (Sudbury, Mass). 2017;23:262–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, Murtaza M, Biggs H, Rueda OM, Chin SF, et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duffy MJ, Evoy D. McDermott EW CA 15–3: uses and limitation as a biomarker for breast cancer. Clinica chimica acta; Int J Clin Chem. 2010;411:1869–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Wei Q, Dong D, Ren L. The role of TPS, CA125, CA15-3 and CEA in prediction of distant metastasis of breast cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;523:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W, Xu X, Tian B, Wang Y, Du L, Sun T, et al. The diagnostic value of serum tumor markers CEA, CA19–9, CA125, CA15–3, and TPS in metastatic breast cancer. Clinica chimica acta; Int J Clin Chem. 2017;470:51–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen AC, Sørensen PD, Jacobsen EH, Madsen JS, Brandslund I. Sensitivity of CA 15–3, CEA and serum HER2 in the early detection of recurrence of breast cancer. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51:1511–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lumachi F, Brandes AA, Ermani M, Bruno G, Boccagni P. Sensitivity of serum tumor markers CEA and CA 15–3 in breast cancer recurrences and correlation with different prognostic factors. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:4751–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirata BKB, Oda JM, Guembarovski RL, Ariza CB, de Oliveira CE. Watanabe MA Molecular markers for breast cancer: prediction on tumor behavior. Dis Markers. 2014;2014: 513158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z, Guo X, Tang L, Peng L, Chen M, Luo X, et al. Methylation analysis of plasma cell-free DNA for breast cancer early detection using bisulfite next-generation sequencing. Tumour Biol: J Int Soc Oncodev Biol Med. 2016;37:13111–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan JCM, Massie C, Garcia-Corbacho J, Mouliere F, Brenton JD, Caldas C, et al. Liquid biopsies come of age: towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:223–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang SC, Liao LM, Ansar M, Lin SY, Hsu WW, Su CM, et al. Automatic detection of the circulating cell-free methylated DNA pattern of GCM2, ITPRIPL1 and CCDC181 for detection of early breast cancer and surgical treatment response. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13: 1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guan B, Welch JM, Sapp JC, Ling H, Li Y, Johnston JJ, et al. GCM2-activating mutations in familial isolated hyperparathyroidism. Am J Human Genet. 2016;99:1034–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin RK, Su CM, Lin SY, Thi Anh Thu L, Liew PL, Chen JY, et al. Hypermethylation of TMEM240 predicts poor hormone therapy response and disease progression in breast cancer. Mol Med. 2022;28:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delplanque J, Devos D, Huin V, Genet A, Sand O, Moreau C, et al. TMEM240 mutations cause spinocerebellar ataxia 21 with mental retardation and severe cognitive impairment. Brain. 2014;137:2657–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Traschutz A, van Gaalen J, Oosterloo M, Vreeburg M, Kamsteeg EJ, Deininger N, et al. The movement disorder spectrum of SCA21 (ATX-TMEM240): 3 novel families and systematic review of the literature. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;62:215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yahikozawa H, Miyatake S, Sakai T, Uehara T, Yamada M, Hanyu N, et al. A Japanese family of spinocerebellar ataxia type 21: clinical and neuropathological studies. Cerebellum (London, England). 2018;17:525–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng S, Zeng J, He M, Zeng X, Zhou Y, Liu Z, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 21 exists in the Chinese Han population. Sci Rep. 2016;6: 19897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seki T, Sato M, Kibe Y, Ohta T, Oshima M, Konno A, et al. Lysosomal dysfunction and early glial activation are involved in the pathogenesis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 21 caused by mutant transmembrane protein 240. Neurobiol Dis. 2018;120:34–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang SC, Liew PL, Ansar M, Lin SY, Wang SC, Hung CS, et al. Hypermethylation and decreased expression of TMEM240 are potential early-onset biomarkers for colorectal cancer detection, poor prognosis, and early recurrence prediction. Clin Epigenetics. 2020;12: 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naumov VA, Generozov EV, Zaharjevskaya NB, Matushkina DS, Larin AK, Chernyshov SV, et al. Genome-scale analysis of DNA methylation in colorectal cancer using infinium HumanMethylation450 beadchips. Epigenetics. 2013;8:921–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang SC, Liao LM, Ansar M, Lin SY, Hsu WW, Su CM, et al. Automatic detection of the circulating cell-free methylated DNA pattern of GCM2, ITPRIPL1 and CCDC181 for detection of early breast cancer and surgical treatment response. Cancers (Basel). 2021. 10.3390/cancers13061375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su JQ. Liu JS Linear combinations of multiple diagnostic markers. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88:1350–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu MC, Oxnard GR, Klein EA, Swanton C, Seiden MV, Ccga Consortium. Sensitive and specific multi-cancer detection and localization using methylation signatures in cell-free DNA. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:745–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller BF, Li TRP, Margolin G, Petrykowska HM, Athamanolap P, Goncearenco A, et al. Leveraging locus-specific epigenetic heterogeneity to improve the performance of blood-based DNA methylation biomarkers. Clin Epigen. 2020;12:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu J, Zhao H, Huang Y, Xu S, Zhou Y, Zhang W, et al. Genome-wide cell-free DNA methylation analyses improve accuracy of non-invasive diagnostic imaging for early-stage breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Constâncio V, Nunes SP, Henrique R, Jerónimo C. DNA methylation-based testing in liquid biopsies as detection and prognostic biomarkers for the four major cancer types. Cells. 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Nunes SP, Moreira-Barbosa C, Salta S, Palma de Sousa S, Pousa I, Oliveira J et al. Cell-free DNA methylation of selected genes allows for early detection of the major cancers in women. Cancers. 2018;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Li L. Sun Y Circulating tumor DNA methylation detection as biomarker and its application in tumor liquid biopsy: advances and challenges. MedComm. 2020;2024(5): e766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneble EJ, Graham LJ, Shupe MP, Flynt FL, Banks KP, Kirkpatrick AD, et al. Current approaches and challenges in early detection of breast cancer recurrence. J Cancer. 2014;5:281–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong J, Muralidhar R, Wang L, Huang CC. Epigenetic modifications of cfDNA in liquid biopsy for the cancer care continuum. In: Biomed J. 20240322 edn; 2024: 100718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Diaz IM, Nocon A, Held SAE, Kobilay M, Skowasch D, Bronkhorst AJ, et al. Pre-analytical evaluation of streck cell-free DNA blood collection tubes for liquid profiling in oncology. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao Y, Li Y, Chen P, Li S, Luo J, Xia H. Performance comparison of blood collection tubes as liquid biopsy storage system for minimizing cfDNA contamination from genomic DNA. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33: e22670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Connor JJ, Voth L, Athmer J, George NM, Connelly CM. Fehr AR two commercially available blood-stabilization reagents serve as potent inactivators of coronaviruses. Pathogens. 2023;12:1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi T, Pan M, Shi H, Wang L, Bai Y. Ge q cell-free DNA fragmentomics: the novel promising biomarker. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mattox AK, Douville C, Wang Y, Popoli M, Ptak J, Silliman N, et al. The origin of highly elevated cell-free DNA in healthy individuals and patients with pancreatic, colorectal, lung, or ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. 2023;13:2166–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pessoa LS, Heringer M. Ferrer VP ctDNA as a cancer biomarker: a broad overview. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;155: 103109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma M, Verma RK, Kumar S, Kumar V. Computational challenges in detection of cancer using cell-free DNA methylation. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:26–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norton SE, Lechner JM, Williams T, Fernando MR. A stabilizing reagent prevents cell-free DNA contamination by cellular DNA in plasma during blood sample storage and shipping as determined by digital PCR. Clin Biochem. 2013;46:1561–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chae H, Sung PS, Choi H, Kwon A, Kang D, Kim Y, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA in Korean patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Lab Med. 2021;41:198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lei Y, Zhang X, Su J, Jeong M, Gundry MC, Huang YH, et al. Targeted DNA methylation in vivo using an engineered dCas9-MQ1 fusion protein. Nat Commun. 2017;8: 16026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.