Abstract

Introduction

There have been many calls globally to intentionally incorporate equity-oriented practices into health research to effectively tackle structural inequalities and prevent the creation of new ones. Several toolkits, guidelines, and training modules have emerged to help research teams integrate equity into research conduct. The adoption of these resources and conversion to practice is varied. Developing a deeper understanding of what these variations are and what drives them may help improve both tools and practice in the global research space. Our aim was to document lessons from diverse ongoing public health research projects on how equity is integrated across research stages, what this entails, and what challenges remain.

Methods

Following an institute-wide appraisal process, we identified five research projects carried out from a networked group of research institutes in India and Australia that offered lessons on addressing equity in the conduct of research. We developed five case studies of these projects using an equity in research heuristic by carrying out 22 in depth interviews and one yarning session (an indigenous knowledge generation and exchange method). We spoke with Principal Investigators, research team members, partner organization members, and community representatives. The interviews covered various aspects, such as the context of the study, team building, study design, and analysis. We asked both about strategies for as well as challenges faced when embedding equity into research processes and phases. We analyzed the transcripts using ATLAS.ti version 23, relying on a deductive coding approach aligned with an existing 8quity heuristic.

Results

Across stages of a research project, efforts were made to integrate equity considerations in all five of our case studies, whether explicitly equity focused (N = 2) or not (N = 3). All studies attempted to locate research in context. For non-equity focussed studies, this was done even when not desired by donors; it was common across project types to have longstanding engagement in particular communities and topic areas. This in turn shaped the formulation of research questions. Equity focused projects invested in inclusion of community members as research team members, while other forms of diversity were prioritised by other teams. All studies placed emphasis on capacity strengthening–for team members (especially those newly joining and not from the community), community members, and health providers. Governance of studies employed strategies like being embedded/living in communities, ensuring engagement (on weekends and evenings), and informal outreach, even as this was sometimes challenging to operationalise. Equity focused projects were concerned with power and coloniality and made explicit efforts to reflect upon and address this. Analysis across studies was concerned with disaggregated analysis; in equity studies, intersectionality approaches were adopted, as was foregrounding indigenous research methods and ensuring respect in attribution of analysis. Marshalling science for better health and greater social justice was a proposition common to all studies, although equity focused studies focused not just on the “what” of their question, but the “how” of conducting research. Impact was an imperative of all case studies, research was seen with a long -term view; the research institution itself having to change to support equity focused and equity in projects.

Conclusion

Case studies of equity integration in research revealed strategies as well as challenges. Many strategies as well as challenges were shared across studies, whether focused on health equity as a topic or not. Overall equity-focused projects had more leeway to focus on process related aspects within study scope, although all studies found ways to change “how” research was done. There is a critical need to frame equity integration not merely as an individual project exercise, but also something that requires institutional backstopping and support.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12939-025-02593-1.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health equity as the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among populations due to social, economic, demographical, or geographical factors or other dimensions of inequality like sex, gender, ethnicity, disability, or sexual orientation [1]. Braveman adds to the definition, stating it as an ethical value based on distributive justice and fairness, linked to human rights [2]. Equity is integral to not just the analysis of research outcomes but the very endeavour of research. Global health research has been evolving from focussing on addressing inequities in health outcomes to paying greater attention to equity in the conduct of research itself [3]. In recent years, the decolonisation movement and growing advocacy around equity in research governance and partnership have highlighted the inequities inherent in the field of global health research [4, 5]. This is accompanied by calls for transforming knowledge production practices to make them more equitable and strength-based [6, 7].

Over the years, researchers and institutions across the globe have developed toolkits and frameworks that help researchers integrate equity into the conduct of research. Some of these resources include the Health Equity Research Impact Assessment by Castillo and Harris [8], The USAID checklist on health equity programming [9], and a toolkit by Plamondon that identifies actions that help integrate equity into research [10]. The American Medical Association and the American Medical College Association have jointly developed a toolkit for using language, narratives, and concepts related to health equity research [11]. Toolkits like EquiPar offer guidance on managing equitable partnerships between research teams with questions that help teams reflect on people management, research activities, and resource management questions [12].

Across this set of resources and in research training globally, several principles are emerging as critical to equity integration across phases of research. To start with, diversity, equity, and inclusion of research teams have evolved to be key considerations in equitable research conduct, with funding guidelines and institutional policies actively promoting diversity in research teams [13–16]. As teams, not individuals, conduct research, diversity in research teams could improve problem-solving skills [17, 18], and make them more productive, leading to better research outcomes [19, 20]. The need for inclusive teams and researchers with lived experiences related to the study topic is analogized by Abimbola to the Indian parable of blind men describing an elephant to researchers describing social realities that they have only studied, which is accurate when from their own positionalities but could be altogether inaccurate comparing to the lived realities [36]. A study that assessed the literature on global health partnerships suggested that more efforts must be made to build equitable alliances between institutions in the global north and south, acknowledging the broader political and economic context [21]. Understanding the power relations between the researcher and the participants or communities is essential in building equitable research partnerships.

Research priority setting and the determination of research questions are a key area where equity considerations must take root. The involvement of communities in such processes is encouraged by various institutions and research sub-disciplines in public health; guidance for this is offered across quarters and methods, drawing from relational ethics [22].

As part of the design and conduct of research, partnering with communities, putting people at the heart of the research process, and co-producing research have gained traction globally. co-production of research outcomes with communities as research partners is central to the concept of participatory research methods [23]. The power dynamics of research design and governance need careful consideration, and participatory research methods are based on respectful engagement with community members [24]. Research priority setting is an This creates demands of methods, as Kennedy and colleagues point out, noting the value of culturally safe research methods like yarning, that draw from indigenous communities and may be offer promise in decolonising research practice, alongside researcher reflexivity and data custodianship that foregrounds Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations [25].

The diversity of research participants is a significant determinant in improving the robustness of research findings and a core equity consideration [26]. During analysis, it is recommended that researchers specifically explore inequalities between and within underserved groups; recommended frameworks for this include SGBA (Sex and gender-based Analysis) and PROGRESS Plus (Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, and Social capital and more) are used widely [27, 28].

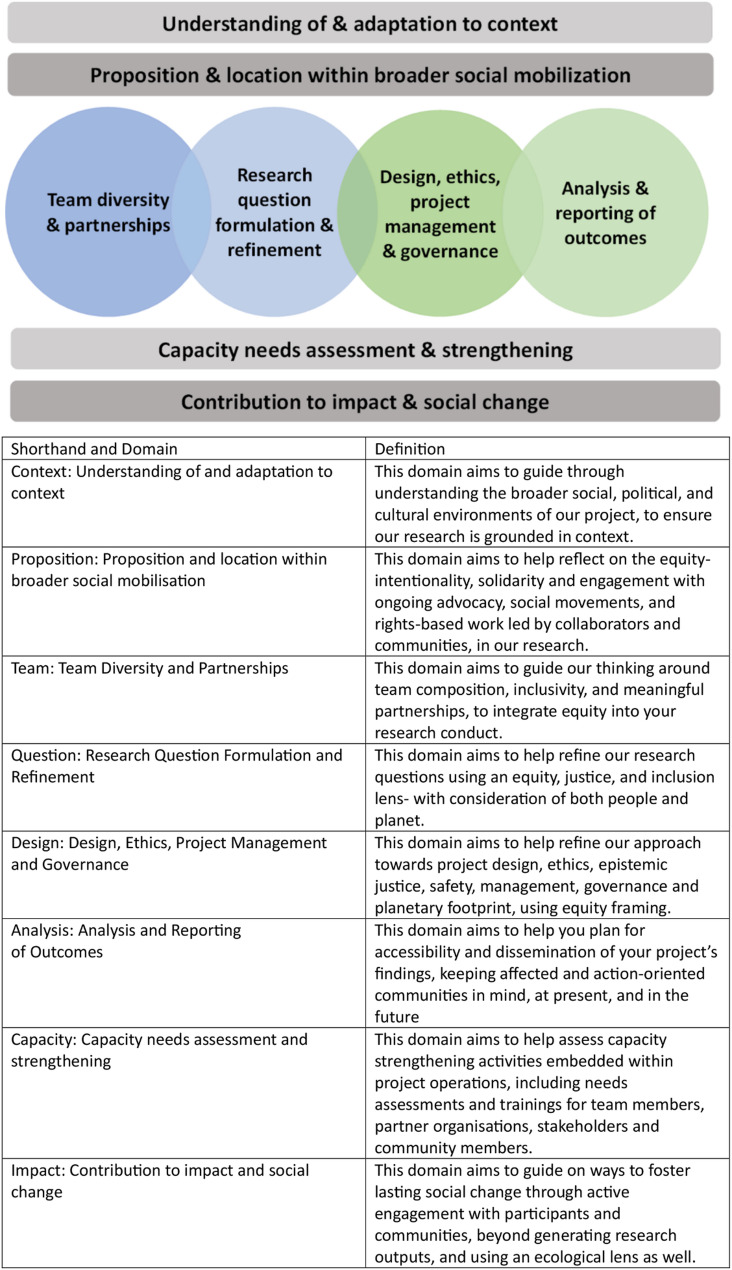

Researchers at the George Institute for Global Health (TGI) compiled and analysed the literature around health equity and developed a tool called “8Quity” as part of the institutional agenda to integrate equity into research conduct and managing partnerships [29]. Initially designed for researchers at TGI, and now being shared externally owing to the interest it has generated, the 8quity toolkit has eight domains that follow a research project trajectory from understanding the context of the study, proposition, framing the research question, team formation, design and governance, analysis of outcomes, capacity strengthening, and impact for communities (see Fig. 1). The toolkit has a set of questions for each of the eight domains for researchers to reflect upon research practices, along with resources to refer to for improving the understanding of concepts related to equity in research processes (see Supplementary File A). In addition, the we have been developing a glossary, case studies, a resource inventory and additional prompts and reflection tools for researchers.

Fig. 1.

Domain areas of 8quity tool.

Source: Authors, adapted from Kakoti et al. [29]

This paper presents the case studies that were developed, focusing on ongoing research projects in the TGI offices in India and Australia. We opted for a qualitative approach to understanding the perspectives of researchers and their teams, but also other actors involved in the research process. From across these perspectives and drawing from a diversity of study types, we were interested in strategies used for equity integration in research, but also enablers and barriers associated with them.

Method

The current study was informed by an earlier exercise in our institution, which involved the piloting of the 8Quity tool developed by Kakoti et al., which corresponded to literature that convey the idea of each domain in the tool [29]. Following the pilot, a case study design was adopted to document best practices in integrating equity into research methods from five research projects conducted in two of the four TGI offices.

Case study methods were used to document the experiences of researchers in integrating equity across the stages of a research project, emphasizing lessons, best practices, barriers, and challenges faced while considering equity dimensions across the typical phases of a research project. The developed case studies were later condensed and thematically arranged using Baurn and Clarke’s thematic analysis approach [30] across the eight domains of the 8quity tool.

Data collection was carried out by an early-career researcher (MK) with a master’s in Developmental Studies, a mid-career male Research Fellow (HS) with a postgraduate degree in public health, and a senior program director with a doctorate in public health (DN) between May 2023 and July 2024. A community-based researcher was hired to conduct the interviews in Telugu.

Sampling

To arrive at an initial list of projects, we used information from the earlier pilot exercise with the 8Quity tool, the administrative project database of The George Institute for Global Health, and snowballing within the institute. We used a variation sampling approach (Table 2), seeking to identify projects across:

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies selected,

| Location | India | Australia | India | Australia | India |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project code | SCKU | STX | EPM | GUM | ARS |

| Number of participants | 2400 | 36 (planned) | 75 (planned) | 100 | 10,100 |

| Study period in years | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Study topic | Renal disease (disease/ condition focused) | Injury prevention (disease/ condition focused) | Pharmaceutical Policy and Regulation (health system building block focused) | Indigenous health (population focussed) | Health Equity in Urban areas (population focused) |

| Design | Longitudinal Observational study | Community based RCT | Health Policy and Systems Research (website review, regulatory review, Key informant Interviews) | Indigenous research methods, Participatory Action Research, Evidence synthesis, | Participatory Action Research |

| Designed to study Health Equity | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Governance | TGI PI | TGI PI | External PI | TGI PI | External PI |

-

(i)

The institution’s three strategy pillars (Better Treatment, Better Care, and Healthier Societies),

-

(ii)

Types of study design,

-

(iii)

Size and duration of study, and.

-

(iv)

Research governance models (led by TGI, not led by TGI, large and small teams, conducted in just one country or multi-sited work, etc.).

Study participant selection

For each project, we approached the study teams, briefed them about the study purpose, and requested that they recommend participants for our study. From those recommendations we conducted in-depth interviews, which included Principal Investigators, research staff including a Research Fellows (RF) and Research Assistants (RA), the Program Manager (PM), and two project stakeholders (project participant/community representative/partner representative/funder representative). Most of the participants (n = 17) were employees of TGI, and were familiar to the interviewers. TGI maintains an employee database with short bios and contact details of every employee, which could be used if the interviewer or participant from TGI wanted to know more about each other and the nature of the work. To interview external stakeholders, the concerned project PI introduced the research team to them through emails.

Three topic guides (Supplementary File B) were used to conduct the interviews, with questions adapted from the 8Quity tool questionnaire. The topic guide was tailored for each category of the interviewee, i.e., the PI, Research staff, and other project stakeholders like members of civil society, and state health department staff.

A total of 26 participants were interviewed from five projects.

Data analysis

Online interviews were recorded in Microsoft Teams with built in, AI-enabled transcriptions in English. The Microsoft Teams-generated transcripts were checked and edited by the interviewer and a third-party professional transcription service provider. In-person interviews were recorded using a voice recorder, and interviews in Hindi and Telugu were translated and transcribed to English by a third-party agency. The transcripts and recordings were moved into a secure TGI drive with researcher-only access. DN and HS did the coding process, and DN reviewed the overall coding for quality and reliability through coding discussions and review meetings. A deductive thematic coding approach was used to index the code and themes [30]. A set of pre-defined codes based on the topic guide questions was used to guide the coding and indexing of the data using Atlas.Ti 22 software. Findings were then thematically organized based on the 8Quity domain areas depicted in Fig. 1, lessons/best practices, enablers/barriers to integrating equity in a research project, and a narrative summary of these findings developed for each case study. The case studies and the findings were categorized based on tags such as geography, study design, and research topic, among others. The draft case studies were sent back to project teams for content approval. After the approval, the data from the case studies were consolidated and thematically arranged.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee in the George Institute for Global Health (project 02/2023). A two-step consent process was adopted for conducting the interviews. First, a written informed consent was obtained from the participants through a Participant Consent Form (PCF) wherein they noted their willingness to participate in the research study.Every participant was sent detailed information about the proposed research work, and topic guide well in advance through email. In-depth semi-structured interviews of approximately 45 min were conducted in person (n = 6 interviews) and via Microsoft Teams (n = 20 interviews) in participant language of preference (English, Hindi or Telugu Second, precaution to prevent deductive disclosure of identity was taken for which a post-confidentiality form (adapted from [31] was shared with the participants post the interviews offering them a range of confidentiality options to choose from. All the participants provided written informed consent and recorded oral consent. The recordings were transcribed by a professional third-party agency that had signed non-disclosure agreements with TGI.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of a total of 26 participants, more than half (57%) of the participants we interviewed were women. We observed that women occupied key decision-making roles; four out of five were principal investigators. A gender balance was observed in senior research staff roles (see Table 1). All the research studies we included for the current study had a study period of 3–5 years. Two of the studies were being conducted in Australia, and three had fieldwork in India. The number of study participants ranged from 36 to 10,100. (See Table 2)

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Study participant | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Principal Investigator | 1 | 4 |

| Program Head, Research Fellow/Research Assistant | 5 | 7 |

| Program Manager | 1 | 1 |

| State Health Department staff | 1 | 1 |

| Scientist, Government Research organization | 1 | 0 |

| Civil Society Organization staff (partners)or community members | 2 | 2 |

| 11* | 15* |

*This table notes the total number of respondents. Four of them were involved in one yarning session

We noted that two of the studies (GUM and ARS) had an explicit orientation towards health equity. Both employed the method of participatory action research, which then affected many aspects of the study – from question, to design, to analysis, as well as context, proposition, capacity-strengthening and impact. Further, this was made possible in the case of both these studies because they were five years in duration. The other study designs seen included an observational study, a Randomized Controlled Trial, a cross sectional mixed methods health policy and systems research study as well as two Participatory Action Research (PAR) studies.

Detailed information on each case was drawn out to look at each 8quity domain (see Supplementary File C). Drawing from this, a narrative summary of findings was developed, corresponding to the 8 sections of 8quity; namely context, team, question, capacity, design, analysis, proposition, and impact.

We found substantial investment across all study designs and types – whether focused on equity or not – in locating research in context and remaining appraised of context over the period of the research study. A PI described the process as explicitly not involving research, but rather building relationships, as follows:

for the first several months, we did nothing. We just went into the community, we spoke to the community, we tried to build bridges with them, try to identify what are the various social groups that have influence in the region and who we can talk to, to make them partners.…we strongly took a lot of help from ASHA, because they belong to the community, and this being a health issue, we have to do it with support from the local community. when we developed our field force, we hired people from within the same community (SKU2).

It was very common to have community consultation – whether formal or formal – in the initial period of setting up a study. In two cases (SCKU, ARS), efforts were made to reside in communities where research was taking place, and to be part of the everyday. It was noted by SCKU scholars that donors may not be interested in these aspects – instead focusing on the core research question, which meant that directing resources towards this aspect of the research process would be vexed. The existing evidence base was canvased (STX, GUM, ARS) and researchers had a strong understanding of context based on longstanding work in the area and/or engagement with field sites (GUM, STX, SCKU).

In setting up teams, it was found that attention to diversity of experience – including lived experience (GUM), and “of brains” (STX) in the hiring process, was seen as being critical. A stated challenge was the lack of diversity and relevant experience in applicant pools (STX, SCKU), as explained by a PI:

it’s actually not the label of whether they’re young, old, male, female, prefer not to say, transgender, whatever. It’s not the actual label, it’s the way they think. It’s the diverse. It’s how they thought from a research leadership perspective. It’s actually having a diversity of brains that is what’s important. And it just so happens that by sort of striving for that, then you do end up getting like a diversity across all the other labels (STX 1).

It was less clear, however, who decides what an adequate threshold of diversity is. In earlier discussions about inclusion, TGI teams have also noted that some ways of ensuring diversity may be intrusive, triggering, and/or violative of privacy (e.g. asking people about their sexual orientation, lived experience) – of which teams must also be mindful. An enabler of diversity and inclusion in recruitment was donor emphasis: “We reflected on gender, and in fact, the proposal requires you to complete a gender equity statement, so that made us kind of pause and think about gender from various dimensions” (EPM 1). The GUM team reflected on developing a human resource plan for hiring and ensuring career progress for candidates from underserved population groups and specific steps to foster cultural safety, like keeping the First Nations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) flag inside the office premises. Strategies were also designed to hire and retain candidates with skill sets like art, which are not often recognized as core research skills in biomedical research institutes.

With respect to research question formulation, case studies revealed variation in the process. In some cases, questions emerged from long-time engagement of the research team with the issue (STX) or consultations with community members to identify areas of research (GUM)., in the case of SCKU, the research institute reached out to an open call by the government to study a public health issue. The government decision to invite a research institute was due to long-term public outrage around the issue In another case, the question was driven by an earlier seed grant and the interest of the PI (EPM) as well as academic partners in LMICs, to explore an extremely understudied area, as explained by a project lead:

People haven’t done a lot of research in this area and I see it as a kind of really neglected area that you’ve, you know, all governments have to do it. So all pharmacy-related stuff has to be regulated, all health facility-related stuff has to be regulated but there’s been relatively little research on how we can do that better. (EPM1)

In another case, defining the question involved engagement of the research team with community members and organisations working with them (ARS). This was built into the proposal development process. The scope of the grant required the team to focus on the health and wellness of the underserved population through community-based participatory action research. Through a literature review and expert consultations, the team identified waste workers in tier two cities of India as the population they needed to work with. The specific research areas and interventions were developed following community consultations. It was noted that it was not always possible to derive questions solely from community perspectives, but rather build community perspectives into latter stages of the research question formulation process, which all projects attempted to do. It was noteworthy that this variation did not appear to be different for explicitly equity focused questions as compared to other questions.

Capacity strengthening was a component of all studies. A view common to all projects, was articulated thus:

we have always understood capacity strengthening as something that we all need in the project… not something that LMIC researchers or partners need. We have also understood it as something that we all need and different partners are in different positions of expertise to share capacity and strengthen each other. So that’s kind of the premise that we started out with. Including community members. Community members have all sorts of skills, and knowledge that they also bring and we are learning from that. So that’s always been the kind of premise. (ARS4)

The specific content of capacity strengthening varied substantially, catering to need and context, although all studies had scope (though not all had funding) for higher education (e.g. Masters and doctoral training owing to institutional partnerships with reputed international academic, degree-awarding institutions) of team members. As per need, we learned of staff training on instrumentation (e.g. Sample collection) (SCKU), orientation for non-indigenous team members (GUM), language training (in English, SCKU), as well as chances to go to short trainings and conferences offered by partnering academic institutions and collaborators (STX, EPM, ARS). In some cases, community members (ARS) or area health providers were offered trainings (SCKU) on areas of identified need, or opportunities for multi-sited exchange and learning were offered (ARS, EPM). In GUM, training was led by community members for the team, while in most other cases, research team members were supporting training, including on gender sensitisation in communities, for team members, and outreach/engagement staff (SCKU, ARS). in EPM it was reported that only senior members of the project team had training on health equity related issues (as part of their role in the institution/organisational norms).

Ethics and governance aspects of study design involved the use of diverse strategies to foreground equity were attempted. Among the strategies, being embedded in communities throughout the duration of the study (as, indeed, before) has been important in many projects (SCKU, ARS) as the researchers noted long term relations staying in the project site and hiring community members to research teams helped to build trust in communities and evolved a continuous and evolving understanding of community priorities and realities. In GUM, a reference group representing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups – including those with lived experience of the health issue being addressed in the study, was ensured and has provided guidance throughout the study period. In ARS, researchers have relied on informal consultations and interactions and regular steer from community-based organisations to get inputs into the research process. EPM has received similar steer from advisory group members, where, because the topic relates to governance, care was taken to specifically include government representatives in this capacity. Many teams reported challenges that arose with keeping this focus on equity, including the extra, unaccounted for and often unpaid labour that it entailed to visit communities after their hours of work or on weekends (which suited study participants better), ensuring that care coordination was ensured.). For equity focused studies, a great deal of emphasis was placed on community engagements – ensuring the quality of these was high and thought through - and also, being mindful of power. In GUM, researchers reported their concerted efforts at ensuring tokenism would be avoided and that the country’s colonial past (in the case of Australia) and that the team or the work never lost sight of the context of stolen lands from the community. ARS team found that community members were already doing two jobs and had little time to spend for research, the team started shadowing the community members with their permission to learn more about the challenges in work, The team reflected that community members acted as guides and validated the research findings than formally working as co-researchers. The ARS team was also conscious of changing power dynamics in the course of research, noting that

But of course, being involved in a research project also sets them [participating community members] apart from other community members in the sense that it gives them a bit of elevated status and also gives them access to income, which people are looking to see ‘Oh, they got something out of the project.’ So then it immediately creates a new set of power dynamics. (ARS 4)

The ARS team was mindful of the power shifts arising in communities and tried to include people from different backgrounds. For example, although labour unions working in the area were collaborators, those who were not part of formal associations were also included. The SCKU team had to conduct lab test of bio markers of study cohort as part of the research study, the teams faced the challenge of people not selected as participants (even family members of recruited participants) approaching them for lab services and they partnered with the local public health facility and arranged for the people to do same test at free of cost.

When it came to analysis, the possibilities of disaggregated, subgroup, or intersectional analysis arose. In relation to this, many teams reflected on the demographic and other characteristics of study participants. For instance, the GUM team noted that the population they were working with is a small proportion of the overall population in Australia but that including them – and therefore data on them - was nonetheless important (notwithstanding “sample size” considerations). In another project (SCKU), the PI noted that

people belong to more or less the same class, and you know, you can’t identify a great deal of heterogeneity. So, for example, if you look at the socio-economic category and use the Kuppusamy scale, most of them will fall in the lowest category. (SCKU 2)

An advisor to one of our case study projects noted that integrating equity into analysis needs to be planned very early in the research project. It might require careful planning and specific strategies to power a sample for a disaggregated analysis. As one scholar noted:

I think if it is not envisaged at the outset, the purpose is defeated. You (cannot) just decide to do a subgroup analysis at the end.… if it is not forwarded at the outset, then I think it is a wrong strategy to do a subgroup analysis towards the end because you may not even be able to pick up these. (EPM 4)

In another project (STX), albeit confined to urban areas, subgroup analysis was planned from the outset and was part of study design:

It’s still in metropolitan areas, but across different socioeconomic parts of [name of city], and we did a whole series of focus group work where we did really try to go out, get regional, and we tried to get different demographics - grandparents, parents, mums, dads, culturally and linguistically diverse groups. Yeah. That’s kind of the extent of what we were doing that I’d say it would be under an equity umbrella (STX 1).

In the ARS team, intersectionality was adopted as an analytical lens: An RA working in a southern Indian site explained the term, and how it was core to the research around marginalized communities:

…larger thing is the status of migrant workers. And then within that, we have these different categories of their religion, mostly primarily Muslims, and how this status of being a migrant plus a Bengali, how’s it like doubly disadvantaged here because, you know, if you were a migrant and a Bengali, when all you will be called the Bangladeshi (foreigner in India). So, then the state becomes very antagonistic towards them. Then within that, there are these other hierarchies, not just caste and gender, but also the role of the labor itself (ARS 3).

In the two participatory action research studies, community participation in analysis had not, at the time of interview, taken place. But there were community views on whose data and knowledge it was. A perspective on this was shared by a researcher from the GUM team:

If somebody is Aboriginal and they have done all the research, they have gathered all the data for you, and they’re the leading publisher. They are not the person whose name is at the end of the paper. And, yeah, so it’s just being… it’s more of being respectful (GUM 2).

In GUM, emphasis was placed on the specific use of strength-based approaches and indigenous research approaches and epistemologies, including the use of dance, art, and music for knowledge transfer, as well as methods like yarning to derive insights and gather data. These were not seen as “scientific,” they noted, by journals and others in the scientific community, and the publications required protracted correspondence between authors and editors, with the former justifying the value of indigenous methods of research and impact it generated in these communities. This additional back and forth – and the commensurate delay in publication – was a tradeoff they had made in service of equity.

With respect to proposition, in all studies – both equity and not equity-focused in scope - the role of science in improving population health and health systems was key: in SCKU, understanding disease aetiology was oriented towards reducing risk burden and eventually evaluating interventions related to this. In STX, improving seatbelt behaviour and adherence to reduce child injury was a priority. In EPM, enhancing the regulatory ecosystem to ensure both access to and safety of medicines was proposed. GUM looked to employ indigenous research methodologies led by indigenous researchers on burns and injuries but also to contribute to the decolonisation of health research. ARS was employing participatory approaches to support minoritized workers communities in understanding and transforming their (determinants of) health.

Apart from this, some projects offered direct support in communities hosting studies. SKDU established a counselling centre and kept oversight on diagnostics and drug supplies of relevant medicines in the communities of study. Health care access was enhanced, and a policy change was even introduced to incentivise treatment. In ARS, researchers reported supporting health care-seeking, crowdfunding (during COVID) to support grassroots organisations and local crisis management that would be related to ongoing advocacy or developmental concerns. A community member had this to say:

They taught us a lot. From what I understood, they taught us the things about our work how we can fight for, and to what extent we can fight for them. Another point was regarding to our health. For women like us, what we should do during work and how we should do it, and what kind of rights women have. (ARS5)

Having a propositional approach was often part of a larger trajectory of impact that all projects were concerned with. In some cases, population and system level changes were seen as a result of the research underway. Based on their research findings, the SCKU research team provided information to communities such that many started changing their drinking water practices; they also managed to catalyse government intervention to reduce groundwater contamination (only after which, study results were permitted to be published). Two other studies were taking on the regulatory context (around road safety and medicines) and admitted that this was both difficult and a longer term process as well as a difficult area to do research in the first place (STX, EPM). This is because changing regulatory policy involves advocacy and mobilisation of a range of actors and sectors beyond health (i.e. in the legislative space or in sectors like commerce, transport) where there were vested interests (related to lowering costs or increasing profit) that were not non-aligned with securing health.

The ARS team was circumspect about emerging power dynamics where those involved with the study (mentioned earlier), with remuneration and having a greater deal of information and potentially even access to other powerful actors, would be changing intra-community dynamics and that this would have to be tracked and addressed longer term. Another key challenge affecting impact that the researchers mentioned was managed the delicate role in balancing the relationship between the community and the system, as its often not possible to have an adversarial stance toward either of them. An RF explained:

You’re positioned between communities and systems; I think sometimes you also have to balance those two things out. we’re a research organization; we’re not activists, so there’s not an adversarial stance that you take…I mean, if tomorrow we go to court (supporting the community)… the system is not going to be very happy with it (ARS 1).

Finally, in a yarn, members of the GUM team reflected that transformation of the research institute itself was an important step in making social change:

Things that were seemingly small can actually create a huge difference in terms of creating that enabling environment, and it was, and it was difficult at the start to get, bring leadership on that journey of recognizing why those things are actually important. So things such as having an acknowledgement of country and welcome to country protocol or policy for the office and purchasing flags that are there in the reception or in the hub where, you know, you can come in as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person and see yourself represented there rather than seeing the Australian flag. (GUM YRN)

Discussion

We developed five case studies using the 8quity tool as the reference and mapped the information collected through interviews against the 8 domains of equity tool. The case studies captured how study teams have conceived the idea of equitable conduct of research while employing diverse study designs and data collection approaches. It must be clarified at the outset that the 8quity tool does not (yet) provide instruction or recommended practice for equity integration in studies; rather, by looking reflexively at studies in our own institution, we hoped to develop a sense of what is already done, what is not possible, and what may be feasibly recommended. This exercise follows an earlier cataloguing of what is recommended (but not always done) [29], and is meant to help further develop a menu of recommended research practices that have been carried out. We present our findings relative to the literature in this section, going domain by domain.

To understand the context of the study, research teams have employed a variety of methods such as desk reviews, being embedded, observations, local NGO partnership, consultations and having a reference group. These methods align with contextual inquiry methods described in eHealth research [32]. The methods used by the teams have helped them to understand the context and adapt the study base on these learnings. This is a dynamic process that challenges research convention, as described by Thomas:

The idea that illuminating complex situations needs inquiry to be participatory, multiperspective and build communities challenges the hallowed idea of ‘objective’ research, in which the researcher is purposefully separated from the object of study. The logic of the authors is irresistible – a single snapshot cannot see much of what is going on in a complex evolving situation, so researchers need to use a variety of different kinds of snapshots, coupled with a locally understood narrative that together can illuminate more of the unfolding story [33].

This idea of snapshots is attempted by all case studies, we found, albeit using varying mechanisms. Further study could explore what other methods there are for this or indeed what the use of particular methods yields in terms of understanding, and what tradeoffs there may be (for example, an NGO partnership may constrain perspectives (of other NGOs, actors), while being embedded may constrain the ability of all or any research team member to participate.

Linked to this, we learned that study team members moved to study sites, had informal engagement with the community, and hired locally to build relations with the community and understand the research context. Building an inclusive team was a major consideration for all the project leads; some teams expressed practical difficulties in making research teams inclusive, and others offered practical steps to make them. All the PIs and program managers we interviewed spoke about the efforts to maintain the diversity of research teams in terms of age, gender, sexual orientation, education, and geography. The challenges in building and keeping teams inclusive remain; a barrier mentioned was the lack of a diverse candidate pool to choose from when the hiring process occurred. This could be a reflection of existing structural inequalities where only people from a certain class or gender have access to resources and opportunities to attain technical skills that are demanded in modern-day biomedical research, especially in LMICs like India, where inequalities exist in access to even primary education [34]. It could also be because not enough efforts are made by hiring managers to reach out to potential candidates; for example, job advertisements in English on organization websites, list-servs, and professional communities could miss out on people who do not have access to these resources. It is important here to acknowledge the colonial roots of global health research, the threat of epistemic injustice which values only certain kinds of credentials and expertise as valid [35]; and the concomitant call to “decolonize global health” by addressing power dynamics within and across transnational research partnerships and among funders [35–38]. It has also been found that people, especially minorities, connect with and are more productive in organizations that share their social values and could correlate with their identities [39].

Research projects ensured involvement of community members in the research question design and implementation or set up a reference group comprising of community members to advise the implementation of their study. In 2025, WHO launched a guidance on the ethics of research priority setting directed at funders, policy-makers, research institutions, research teams and researchres, as well as community organisations, professional associations and advocacy groups [40]. The guidance underscores the need to optimize social value, respect obligations, assess and justify harms, while also ensuring that processes followed in research priority setting are fair. Researchers are specifically directed to prioritise the needs of groups they are already working with, else to optimize social value of research [40]. This principle, though not expressly articulated by participants, appears to align with their motivation.

Capacity strengthening was a major focus across projects, and included instances of research team members with lived experience of the study topic supporting the capacity strengthening of other team members, as well as adoption of Indigenous research methods. Many donors now are asking for explicit research capacity strengthening components in grants and there is definitely room for this aspect of research conduct to develop and expand [41, 42]. Strategies were seen at individual and environmental levels – in alignment with Vogel et al. [43] At the individual level, our case studies included doctoral training as well as on-the-job skill training. At the environmental level, research teams have made efforts to enhance the capabilities of local partners and communities; the SCKU project offered specialist training to local health workers, ARS project provided training to community members based on needs assessment. A DFID practice paper on capacity building mentions focusing on strengths and unleashing staff potential along with local ownership and contextual research as part of capacity-strengthening exercises [44]. While skill-building exercises receive priority, it was noted that sessions on Equity, Diversity, and inclusion were often limited to senior members; these sessions must be made available to all the research staff members and research participants to foster leadership. Use of strength-based approaches for capacity strengthening by the GUM team and capability approach by ARS team focus are based on appreciating the value of Indigenous knowledge and lived experiences of community members respectively, these are very crucial in a time where epistemic injustice prevails and knowledge systems from underserved communities and LMICs are overlooked by the global research community [45]. There was less emphasis in our study on institutional or organizational practices to promote equity, however, which could include financial support to team members to shore up training or support the extra outreach often involved in engaging communities. This would be a critical area of further inquiry.

The research projects selected for the current study were long-term projects which gave the projects enough time to effectuate their design slowly, build relations, and plan co-production with communities. The case studies describe several strategies that TGI research teams have put into practice to improve community participation; the GUM and STX teams used community advisory groups that advise the research project at every stage with the group is comprised of people with lived experience, this involvement has enhanced the trust from the communities leading to sustainable research outcomes, The Decode Me Study [46] from the UK, also uses a similar strategy and has a patient advisory group guiding the research process. Methods like member checking, covering travel costs and coordination with employers to enhance participation were seen in our study and are identified strategies to mitigate the risk of tokenism in research, and to get accurate perspectives about the lives of research participants, and generating outcomes that matter to the lives of the people involved [47].

A common challenge during analysis of study data was generalizability, which can sometimes be a pretext for ignoring or not examining variation and lack of homogeneity that often exists in groups of study participants. Disaggregating data, looking for intersections of data, and supplementing with new information [48] can help researchers to use an equity lens and understand differences within communities and actually bridge gaps in universal coverage or access. Further, carrying out heterogeneity or specificity focused analyses are already a gold standard in global health disciplines. In our study, research teams mentioned the use of dimensions of inequalities like age, sex, education, socioeconomic status, etc., to analyze data added to the robustness of research findings. Two of the five study teams (GUM, ARS) used a qualitative approach to look at the data while three had a mixed methods design with quantitative and qualitative components (SCKU EPM and STX). The availability of disaggregated data is key to equity analysis, and collecting these data points powered to provide insights requires extensive time and resources; in countries like India, the publicly available national level data sets provide disaggregated data but are not powered to interpret data at village level. The research teams also pointed out that the intersectionality lens is a powerful tool for analyzing and interpreting data. While constant long-term engagement with communities gave the researchers accurate information about the different lives of individuals within a community, short-term projects with tight budgets often won’t be able to afford extensive data collection or engage non-academic actors or maintain long-term engagements with communities [49].

The case studies, while planning long-term and short-term outcomes for the community, aimed to be propositional in that they nested in more significant social movements like decolonizing health research. The GUM Case study explains how researchers working with Indigenous groups are fighting with the system to bring respect to Indigenous methods of research and, in the process, have built a project that ensures respect and value for researchers and communities belonging to the nation. The ARS project also places itself in a larger struggle and uses a rights-based approach to support communities by fostering community action to improve health and well-being. The EPM project could also be seen as part of a movement to bring accountability to communities by improving the regulations to control the market forces.

Our participants were circumspect about framing and claiming impact from their (as yet unfinished) research projects, noting that indeed a larger time horizon would be needed to assess this. Various frameworks for research impact have existed for a long time [8, 50], although their uptake and impact are unclear. At our institution, research impact is an organizational priority: toolkits, reporting frameworks and SOPs have been introduced over the past five years for this purpose. It will remain to be seen what the impact of such institutional efforts are, because the time horizon of impact requires more than just an individual researcher or project focus on impact. This is another critical area of further inquiry as well as organizational reform for institutions. It is also an area of consideration for research funders to consider – going beyond typical metrics of journal publication, which hare already hampered by skewed representation and exclusionary practices [51, 52].

Conclusion

Case studies of equity integration in research at a of health research institute revealed strategies as well as barriers to equity integration. Studies that were focused on health equity as a topic had some overlapping and some distinct equity related strategies and challenges as compared to studies that were not – for distinct reasons. Overall equity-focused projects had more attention and leeway to focus on process related aspects of studies, although equity integration was prominent in all study types. It may be possible for wider adoption and scale-up of equity integration, but this would likely require institutional support as it does not appear to be in the purview of many projects in their existing design.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank scholars at the George Institute for Global Health in Australia and India for their candour and openness to this process. We are grateful to our CEO, Prof Anushka Patel for her support of this work and the organisational transformation of which it is part.

Author contributions

DN conceived of the project, supported the acquisition and analysis of data and contributed to the original, revisions and final drafting of this work. MK obtained funding, undertook the acquisition and analysis of data, and contributed to revisions. HS undertook acquisition and analysis of data and created the first draft of the manuscript as well as to revisions. All authors have approved the submitted version and agree to be personally accountable for their contributions.

Funding

This analysis was supported by an internal grant awarded to the Health Equity Action Lab by the George Institute for Global Health. DN is supported by a Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance Fellowship (Grant no. IA/CPHS/23/1/507013).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was issued by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the George Institute for Global Health (Project Number 02/2023). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, in addition to which all data collection was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations in India and Australia.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

8/30/2025

In the Funding section of this article, the information relating to the Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance Fellowship was omitted. The article has been updated to rectify the error.

References

- 1.Health equity [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-equity

- 2.Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(4):254–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar M, Atwoli L, Burgess RA, Gaddour N, Huang KY, Kola L, et al. What should equity in global health research look like? Lancet. 2022;400(10347):145–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCoy D, Kapilashrami A, Kumar R, Rhule E, Khosla R. Developing an agenda for the decolonization of global health. Bull World Health Organ. 2024;102(2):130–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwete X, Tang K, Chen L, Ren R, Chen Q, Wu Z, et al. Decolonizing global health: what should be the target of this movement and where does it lead us? Global Health Res Policy. 2022;7(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Divorcing. ‘Global Health’ from ‘global health’: Heuristics for the future of a social organization and an idea| Journal of Critical Public Health [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 2]. Available from: https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/jcph/article/view/78017

- 7.Unfair knowledge practices in global health. a realist synthesis| Health Policy and Planning| Oxford Academic [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 2]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/heapol/article/39/6/636/7655451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Castillo EG, Harris C. Directing research toward health equity: a health equity research impact assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(9):2803–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program. Checklist for Health Equity Programming [Internet]. USAID. 2011. Available from: https://www.mchip.net/sites/default/files/Checklist%20for%20MCHIP%20Health%20Equity%20Programming_FINAL_formatted%20_2_.pdf

- 10.Plamondon KM. A tool to assess alignment between knowledge and action for health equity. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Medical Association [Internet]. [cited 2022 Feb 1]. Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative and Concepts. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/about/ama-center-health-equity/advancing-health-equity-guide-language-narrative-and-concepts-0

- 12.Goodman C, Bond V. The EquiPar Tool Supporting Equitable Partnerships for Research Projects [Internet]. London UK: London School of Tropical Medicine; [cited 2024 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/media/67776

- 13.Asmal L, Lamp G, Tan EJ. Considerations for improving diversity, equity and inclusivity within research designs and teams. Psychiatry Res. 2022;307:114295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health Research Authority [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 13]. Increasing the diversity of people taking part in research. Available from: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/best-practice/increasing-diversity-people-taking-part-research/

- 15.Kurt A, Blass E. Measuring diversity practice and developing inclusion. Dimensions. 2010;1(1):59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hattery AJ, Smith E, Magnuson S, Monterrosa A, Kafonek K, Shaw C et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in research teams: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Race Justice. 2022;21533687221087373.

- 17.Hong L, Page SE. Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(46):16385–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jr KG. Scientific American Blog Network. [cited 2022 Apr 11]. Diversity in STEM: What It Is and Why It Matters. Available from: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/voices/diversity-in-stem-what-it-is-and-why-it-matters/

- 19.Cooke A, Kemeny T. Cities, immigrant diversity, and complex problem solving. Res Policy. 2017;46(6):1175–85. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell LG, Mehtani S, Dozier ME, Rinehart J. Gender-Heterogeneous working groups produce higher quality science. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e79147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plamondon KM, Brisbois B, Dubent L, Larson CP. Assessing how global health partnerships function: an equity-informed critical interpretive synthesis. Global Health. 2021;17(1):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bridget Pratt. Sharing power in global health research: an ethical toolkit for designing priority-setting processes that meaningfully include communities. International Journal for Equity in Health. 20(127). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Nelson E. A Resource Guide for Community Engagement and Involvement in Global Health Research [Internet]. NIHR; 2019 [cited 2022 May 3]. Available from: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/14708

- 24.Loewenson R, Laurell AC, Hogstedt C, D’Ambruoso L, Shroff Z. Participatory action research in health systems: a methods reader [Internet]. TARSC, AHPSR, WHO, Canada IDRC. Equinet; 2014 [cited 2024 Oct 10]. Available from: https://abdn.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/participatory-action-research-in-health-systems-a-methods-reader

- 25.Michelle Kennedy R, Maddox K, Booth S, Maidment C, Chamberlain, Dawn Bessarab. Decolonising qualitative research with respectful, reciprocal, and responsible research practice: a narrative review of the application of yarning method in qualitative aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Int J Equity Health. 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Mbuagbaw L, Aves T, Shea B, Jull J, Welch V, Taljaard M, et al. Considerations and guidance in designing equity-relevant clinical trials. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Neill J, Tabish H, Welch V, Petticrew M, Pottie K, Clarke M, et al. Applying an equity lens to interventions: using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rotz S, Rose J, Masuda J, Lewis D, Castleden H. Toward intersectional and culturally relevant sex and gender analysis in health research. Soc Sci Med. 2021;114459. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kakoti M, Nambiar D, Bestman A, Garozzo-Vaglio D, Buse K. How to do (or not to do)…how to embed equity in the conduct of health research: lessons from piloting the 8Quity tool. Health Policy Plan. 2023;38(4):571–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association; 2012.

- 31.Kaiser K. Protecting respondent confidentiality in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(11):1632–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kip H, de Jong NB, Wentzel J. The contextual inquiry. eHealth research, theory and development. Routledge; 2018.

- 33.Thomas P. Understanding context in healthcare research and development. Lond J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2014;6(5):103–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garg MK, Chowdhury P, Sk MIK. An overview of educational inequality in india: the role of social and demographic factors. Front Educ. 2022;7:871043. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Besson E. How to identify epistemic injustice in global health research funding practices: a decolonial guide| BMJ Global Health. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 14]; Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/7/4/e008950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Lawrence DS, Hirsch LA. Decolonising global health: transnational research partnerships under the spotlight. Int Health. 2020;12(6):518–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panel® E, Forbes. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Council Post: 13 Ways To Seek Out More Diverse Candidates For Critical Positions. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbescoachescouncil/2021/08/20/13-ways-to-seek-out-more-diverse-candidates-for-critical-positions/

- 38.How To Reach Underrepresented Groups In Your Hiring Process [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.hrfuture.net/workplace-culture/strategy/diversity-inclusion/how-to-reach-underrepresented-groups-in-your-hiring-process/

- 39.Nichols AD, Axt J, Gosnell E, Ariely D. A field study of the impacts of workplace diversity on the recruitment of minority group members. Nat Hum Behav. 2023;7(12):2212–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organisation. WHO guidance on the ethics of health research priority setting [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ethics/who-rps-ethics-guidance-consultation-draft-051124.pdf?sfvrsn=5d30b74b_6

- 41.Sitthi-amorn C, Somrongthong R. Strengthening health research capacity in developing countries: a critical element for achieving health equity. BMJ. 2000;321(7264):813–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fosci M, Loffreda L, Velten L, Johnson R. Research Capacity Strengthening in LMICs [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5d42be4eed915d09d8945db9/SRIA_-_REA_final__Dec_2019_Heart___003_.pdf

- 43.Vogel I. Research Capacity Strengthening Learning from Experience [Internet]., London UK. UKCDS; 2012 [cited 2025 Jan 2]. Available from: https://www.ukcdr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/UKCDS_Capacity_Building_Report_July_2012.pdf

- 44.Capacity Building in Research [Internet], London UK. DFID; 2010 [cited 2025 Jan 2]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a749d72ed915d0e8e399a26/HTN_Capacity_Building_Final_21_06_10.pdf

- 45.Bhaumik S. On the nature and structure of epistemic injustice in the neglected tropical disease knowledge ecosystem. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024;18(12):e0012781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DecodeME [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Home. Available from: https://www.decodeme.org.uk/

- 47.Rolfe DE, Ramsden VR, Banner D, Graham ID. Using qualitative health research methods to improve patient and public involvement and engagement in research. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Analyzing. & Interpreting Data with an Equity Lens [Internet]. Government Accountability Office; 2021 [cited 2025 Jan 2]. Available from: https://cdn.ymaws.com/algaonline.org/resource/resmgr/resources/guides_and_reports/DEI_Data_Analysis_Guide_rev.pdf

- 49.Chamberlain SA, Gruneir A, Keefe JM, Berendonk C, Corbett K, Bishop R, et al. Evolving partnerships: engagement methods in an established health services research team. Res Involv Engagem. 2021;7(1):71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hinrichs-Krapels S, Grant J. Exploring the effectiveness, efficiency and equity (3e’s) of research and research impact assessment. Palgrave Commun. 2016;2(1):16090. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pai MF. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Global Health Research Needs More Than A Makeover. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/madhukarpai/2019/11/10/global-health-research-needs-more-than-a-makeover/

- 52.Ramani S, Whyle EB, Kagwanja N. What research evidence can support the decolonisation of global health? Making space for deeper scholarship in global health journals. Lancet Global Health. 2023;11(9):e1464–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.