Abstract

Sarcopenia affects 20%–40% of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients, significantly reducing muscle strength and functional capacity, leading to a decline in quality of life. This study reviews the impact of sarcopenia in COPD and evaluates effective therapeutic strategies. Findings suggest that pulmonary rehabilitation, combined with aerobic and resistance exercises, and supplemented with protein and vitamin D, enhances muscle function and reduces the prevalence of sarcopenia. Additionally, emerging interventions such as inspiratory muscle training, myostatin inhibitors, selective androgen receptor modulators, and hormonal therapies show promise in improving patient outcomes. A multidisciplinary approach, incorporating personalized exercise programs, targeted nutrition, and psychological support, is crucial for addressing the complex challenges of sarcopenia in COPD. Given its substantial burden, this research highlights critical strategies for optimizing care and improving functional outcomes in this high-risk population.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD, frailty, muscle loss, sarcopenia

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is currently ranked as the third leading cause of death globally; its prevalence and mortality rates are anticipated to rise in the years ahead[1]. By 2050, around 592 million people will be affected by COPD[2]. Being a significant age-related disease, COPD affects around 10% of adults aged 40 and above, posing considerable morbidity and mortality risks[3]. COPD is a condition marked by ongoing inflammation leading to structural lung changes, tissue destruction, and airflow restriction, thus making breathing challenging[4]. A varying number of pathological conditions like chronic bronchitis, emphysema, asthma, and cardiovascular manifestations in the form of hypertension and atherosclerosis may persist in COPD patients and are typically triggered by prolonged exposure to toxic gases or particles, such as those found in cigarette smoke[5].

A patient suffering from COPD presents with a range of symptoms with varying intensities; the most common complaint is respiratory symptoms, including dyspnea, chronic cough, and excessive sputum production; and some patients may also report less common problems such as wheezing, chest tightness, and chest congestion. Due to chronic systemic inflammation, the symptoms may also be accompanied by extrapulmonary effects like fatigue, decreased appetite (anorexia), unintended weight loss, increased decline in exercise capacity, and sleep disturbances. Moreover, psychiatric symptoms, including depression and anxiety, have also been reported. These symptoms tend to deteriorate as the disease progresses and significantly affect a patient’s day-to-day life and overall quality of life[6–8].

The impact of COPD extends beyond the lungs, often coexisting with conditions like cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, bone diseases, psychiatric diseases, and lung cancer. This complexity emphasizes the need for comprehensive management strategies addressing the disease’s pulmonary and extrapulmonary aspects[9]. Individuals with COPD aged 50 and older experience an annual muscle mass loss of about 1%–2%. Additionally, those between 50 and 60 years old and those over 60 show a decline in muscle strength of approximately 1.5% and 3.0% per year, respectively, showcasing the development of sarcopenia[10].

Sarcopenia is a systemic skeletal muscle condition characterized by a progressive decline in muscle mass and decline in function. This condition is linked to a heightened risk of adverse events, such as falls, reduced physical capabilities, frailty, and increased mortality[11]. It is common among COPD patients, with prevalence ranging from 20% to 40% as reported in cross-sectional studies from Greece and Korea. Depending on the classification criteria, it significantly impacts prognosis and physical function, exacerbates symptoms, and reduces the overall quality of life for individuals with COPD.[12–15]. Sarcopenia is a significant cause of frailty, with a prevalence of approximately 4%–17% in older adults and a mean prevalence of 9.9%, as reported in a systematic review[16]. Frailty is a medical condition in which individuals are excessively predisposed to internal and external stressors[17], which in turn leads to an increased risk of developing adverse health-related outcomes such as weakened strength, endurance, and decreased physiological function, elevating susceptibility to heightened dependency or mortality risk[18]. Muscle loss, or muscle atrophy, is defined as the loss or thinning of muscle tissue and a decrease in the muscle mass and muscle fiber cross-sectional area at the histological level[19]. Muscle loss has several causes but is broadly categorized into disuse atrophy, denervation atrophy, and pathologic atrophy.

Sarcopenia’s pathogenesis involves several intertwined factors. Metabolic changes, immobility, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and systemic inflammation collectively contribute to age-related muscle alterations. These factors increase cellular damage, with reactive oxygen species (ROS) believed to activate proteolytic pathways and trigger muscle cell apoptosis. As a result, oxidative stress markers may correlate with clinical measures used to diagnose sarcopenia, such as muscle strength, mass, and physical performance. However, whether this association remains consistent in individuals with COPD is uncertain[20,21].

Biomarkers are crucial in identifying and monitoring sarcopenia and frailty in COPD patients by providing objective measures of disease progression and response to treatment. They indicate underlying biological processes, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, muscle turnover, and metabolic dysfunction. Potential biomarkers investigated in these conditions include markers of muscle damage (e.g., creatine kinase), inflammation [e.g., C-reactive protein (CRP)], oxidative stress (e.g., malondialdehyde), and muscle turnover [e.g., myostatin (MSTN)]. Incorporating these biomarkers into clinical practice can aid in early detection, risk stratification, and personalized management strategies for COPD patients with sarcopenia and frailty[22–24].

Addressing sarcopenia and frailty in COPD is crucial for improving patient outcomes and quality of life due to their significant impact on functional capacity and disease progression. Interventions targeting these conditions can improve exercise capacity, reduce exacerbation frequency, enhance respiratory muscle strength, and increase overall functional status. By preserving muscle mass and function, these interventions can also help mitigate disability, improve independence, and ultimately enhance the overall well-being and longevity of COPD patients[25,26]. Interventions for sarcopenia and frailty in COPD include exercise training, for example, pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), nutritional support, and pharmacological options like anabolic agents. Exercise programs enhance muscle strength and overall physical function, while nutritional support ensures adequate protein intake to prevent muscle wasting. Pharmacological interventions, such as testosterone or selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs), promote muscle protein synthesis. Optimizing COPD management with bronchodilators, oxygen therapy, and exacerbation prevention also indirectly benefits muscle function and quality of life[27,28].

HIGHLIGHTS

Sarcopenia significantly exacerbates the symptoms of COPD, leading to increased muscle weakness, reduced exercise capacity, and a higher risk of falls and fractures, thereby deteriorating the quality of life and independence of patients.

Pulmonary rehabilitation programs, which include supervised and home-based exercises, education, and nutritional support, have been shown to substantially reduce the incidence of sarcopenia in COPD patients, enhancing their physical activity and reducing symptoms.

Combining aerobic and resistance exercises, along with dietary supplements rich in whey protein, leucine, and vitamin D, has been found to improve muscle mass and respiratory muscle strength, thereby managing sarcopenia effectively in COPD patients.

Even with variability in results, emerging therapies for sarcopenia, including selective androgen receptor modulators, myostatin inhibitors, tissue-engineered scaffolds, and metformin, show promising results and may benefit patients unresponsive to conventional therapies.

COPD patients with sarcopenia face reduced quality of life and higher risks of falls, cognitive decline, and depression. Personalized exercise, nutrition, and a patient-centered approach can help improve their well-being.

The existing research explores various aspects of sarcopenia or frailty in COPD, including its prevalence[15,26,29–31], pathogenesis[20,26], associated risk factors[15,26,29–32], impact on clinical outcomes[26,29,30], diagnosis[26,29], and treatment[15,26,33]. Nonetheless, there is a lack of literature that integrates these aspects, examines their interconnections, and assesses the impact on quality of life. Additionally, with the continuous introduction of novel treatment options, updating the literature is crucial to ensure better treatment alternatives.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of sarcopenia in COPD, highlighting its multifactorial causes – such as inflammation, hormonal imbalance, and oxidative stress – and its significant impact on function and quality of life. It outlines current diagnostic tools, including European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2) criteria, imaging, and emerging biomarkers like CAF22 and the creatinine/cystatin C (CysC) ratio. Management strategies are reviewed in detail, emphasizing PR, resistance training, targeted nutrition, and novel therapies such as SARMs, MSTN inhibitors, and neuromuscular stimulation. By consolidating recent findings, this review offers practical insights for early identification and tailored interventions in clinical practice. Through a comprehensive literature review, we aim to deepen our understanding and explore practical strategies to improve patient outcomes and quality of life in individuals with COPD, sarcopenia, and frailty. This manuscript complies with the TITAN Guidelines 2025[34]; no artificial intelligence tools were used in the generation, analysis, or writing of this work.

Methods

This narrative review was conducted following the SANRA (Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles) criteria to ensure methodological rigor and transparency[35]. A comprehensive search of electronic databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane, was conducted to identify relevant studies. Keywords used in the search encompassed “sarcopenia,” “COPD,” “Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease,” “muscle wasting,” “muscle strength,” “nutritional interventions,” “physical therapy,” “exercise programs,” “biomarkers,” “pulmonary rehabilitation,” and “targeted therapies.” The search included all studies up to March 2024, with no restrictions on study design. The selected studies were rigorously reviewed and analyzed to extract findings pertinent to sarcopenia in COPD, which were subsequently included in the paper. This narrative review comprehensively evaluated the included literature, prioritizing credibility and relevance to the review’s objectives. Individual studies were critically appraised to assess methodological rigor, reporting clarity, and potential biases despite the absence of formal quality assessment tools for a narrative review. Studies demonstrating robust methodologies and high quality were accorded more significant weight.

Mechanism of sarcopenia in COPD

Amongst the patients suffering from COPD, sarcopenia varies with musculature measurements, gender, disease severity, ethnicity, age[36], and IBODE (BMI, obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise ability) score[37]. Understanding the complex pathophysiology of sarcopenia is essential, and it is better understood now than it was a decade ago[38]. A study by He et al has shown that multiple factors contribute to the development of this syndrome, including but not limited to age, malnutrition, smoking, inflammatory pathways, dysregulation of protein metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction, skeletal muscle impairment, and oxidative stress[36]. A detailed analysis of these factors is beyond the scope of this review. However, the multi-factorial mechanisms related to COPD are briefly discussed below.

Age and gender differences

Approximately 15% of people aged 65 and above and nearly 50% of those over 80 have been estimated to have sarcopenia[39]; both aging and COPD are linked to a sedentary lifestyle and less physical activity (PA), which causes a gradual loss of neuromuscular junction (NMJ), i.e., progressive denervation of motor units[24]. This denervation-induced atrophy is due to apoptosis as indicated by the increase in the proapoptotic proteins Bax and caspases 3,7,8,10[30]. This leads to a communication breakdown between the nervous and muscular systems, resulting in a decline in muscle mass and strength, particularly affecting type II muscle fibers (fast, glycolytic fibers) by 20%–50%[31].

A meta-analysis conducted in 2021 by Choo et al in the Korean population has shown sarcopenia to be highly prevalent (13.1%) in their elderly population aged ≥65 years, among whom it is profound in males (14.9%) than females (11.4%) , this difference could be explained by several factors, including hormonal differences, baseline muscle mass, and lifestyle choices. The muscle mass in males is influenced by testosterone, which promotes protein synthesis and reduces muscle degeneration. It has been observed that low concentrations of testosterone can lead to muscle atrophy and sarcopenia. Conditions like hypogonadism exacerbate muscle loss in men, independent of age[40]. Moreover, this larger muscle mass is more prone to atrophy when sarcopenia sets in. Studies have shown that men experience a greater absolute decline in muscle mass due to larger initial muscle mass, even in mid-life[41]. Similarly, in women, estrogen has protective effects on muscles by reducing inflammation and promoting muscle regeneration. However, estrogen levels drop after menopause, and younger women benefit from its protective effects, which might help delay sarcopenia compared to men[42]. Additionally, lifestyle variables like greater use of alcohol and tobacco among Korean males might hasten muscle loss and adversely affect total muscle health[43].

Hormonal imbalances

The development of sarcopenia among COPD patients is critically linked with a fluctuation in the concentration of hormones, including increased catabolic hormones such as cortisol and decreased anabolic hormones like growth hormone (GH), testosterone, thyroid hormone, and insulin-like growth factor (IGF); this further exacerbates the loss of muscle mass and strength[44]. Malnutrition is a deficit in energy intake that contributes to decreased muscle mass. Recent developments reported by Damanti et al have shown that a deficiency of micronutrients like hypovitaminosis D due to low dietary intake, low sunlight exposure, and reduced expression of vitamin D receptors[45], in the skeletal muscle fibers, interacts with nucleocytoplasmic transcriptional processes regulating muscle growth. This potentially results in the loss of skeletal muscle mass (SMM)[46].

Smoking and lifestyle factors

Smoking, an unhealthy lifestyle choice, is coupled not only with COPD but skeletal muscle dysregulation as well, which substantiates the development of sarcopenia with COPD[47]. The most well-known cause of COPD is chronic smoking, and research has brought to our knowledge that exposure to cigarette smoke contributes to the development of skeletal muscle dysfunction long before pulmonary pathology is manifested[48]. Cigarette smoke[49] mediates the atrophy and degradation of muscle proteins in skeletal muscle fibers; this catabolism is associated with the activation of proteins targeted for proteasomal degradation in skeletal muscle, i.e., p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and upregulation of muscle-specific E3 ubiquitin ligases: muscle atrophy F-box protein (MAFbx/atrogin-1) and muscle ring finger-1 protein (MuRF1)[50]. This upregulation of MuRF1 results from NF-kB activation following CS exposure[51].

Inflammatory pathways

COPD pathogenesis is remarkably linked with raised serum levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, leucocytes[52], and various proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1beta (IL-1beta) that may affect the loss of SMM and function[53]. The expression of these pro-inflammatory cytokines and their receptors is significantly upregulated when muscle wasting occurs[54]. Muscle catabolism has been attributed to TNF-α in inflammatory diseases like COPD via indirect mechanisms[55]. These mechanisms are less clear, but one potential mechanism is the inhibition of myoblast differentiation, which could limit the regenerative strength of satellite cells after muscle injury[56]. TNFα is responsible for ubiquitin expression and accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins involved in muscle protein degradation[57]. Furthermore, chronic inflammation also affects muscle anabolism due to the synthesis of acute-phase proteins, which deplete the muscle reserves of amino acids for replenishment. Patients with COPD and sarcopenia show decreased glutamate and branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), resulting in higher whole-body myofibrillar protein breakdown[58].

Protein metabolism dysregulation

A study done in 2023 by Henrot et al suggested a disbalance of protein synthesis and degradation in sarcopenic COPD patients[59]. The muscle protein synthesis is regulated by the mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) pathway in response to anabolic stimuli such as IGF-1. However, in COPD-associated sarcopenia, defects in mTOR signaling, including reduced mTOR expression and activity, contribute to diminished protein synthesis, causing a reduction in SMM and strength[60]. Moreover, during acute exacerbations of COPD, IGF-1 levels are reduced and correspond with decreased muscle mass[61]. The two major proteolytic pathways are the ubiquitin-proteosome system (UPS) and the autophagy-lysosome pathway[62]. Degradation of misfolded or defective proteins is carried out mainly by the UPS[63]. Concurrently, muscle protein breakdown in COPD is further exacerbated by the disturbances in autophagy, a cellular response pivotal for removing damaged, dysfunctional organelles and contractile protein aggregates[64].

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Mitochondrial dysfunction is the core mechanism identified in sarcopenia and skeletal muscle aging[65]. With advancing age and chronic disease, the absence of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) histones and insufficient proofreading systems is responsible for a progressive increase in somatic mtDNA mutations[66,67]. This mtDNA damage results in the synthesis of dysfunctional components of the electron transport chain, leading to defective ATP production and overproduction of ROS[68]. This causes mitochondrial breakdown (mitophagy), leaving the muscle less energy-efficient[69].

Skeletal muscle impairment

Skeletal muscle impairment can be characterized by decreased muscle strength, endurance, and increased muscle fatigue[70]. With a shift of type 1 fiber proportion to type 2 fiber in sarcopenic patients with COPD, the muscle-wasting process in patients with COPD is accelerated[71]. Some in vitro studies have suggested that increased intracellular concentrations of ROS and reactive nitrogen species[72] affect the depolarization of membranes and transmission of action potential in cells by reducing the activity of Na+/K+ pumps, calcium pumps, and plasma pumps. These alterations limit the hydrolysis of ATP, forces generated by the interactions of actin and myosin filaments, and the rate of muscle shortening due to the reduced rate of myofilament relaxation[20].

Oxidative stress

One of the main mechanisms in the occurrence and progression of COPD is oxidative stress. Living organisms have superoxide anion (O2−) and nitric oxide anion (NO−) as the most important free radicals. Reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (RONS) induce lipid peroxidation of membrane phospholipids (RONS), which changes membrane structure and functional properties. Moreover, the oxidation or nitration of proteins by these reactive species can change the structure or chemistry of proteins, decreasing protein function. RONS can interact with DNA to cause DNA damage and deletions, mutations, and DNA-protein crosslinking[20]. The accelerated degradation of lung tissue is due to the inhibition of antiprotease processes via the release of excessive RONS by oxidative bursts of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and alveolar macrophages. The resolution of inflammation also delays RONS as they compromise the phagocytic ability of alveolar macrophages, leading to necrosis and emphysema[73]. With advancing research, it has been understood that the accumulation of oxidized proteins and altered proteostasis causes loss of muscle mass, motor units, individual muscle fibers, structural alterations, fragmentation of NMJs, and impaired muscle innervation, thereby playing a remarkable role in the development of sarcopenia[74].

Diagnosis of sarcopenia in COPD

Patients with COPD often experience a decline in muscle mass and strength, which can impact their exercise capacity, independence, and quality of life. This functional impairment is commonly linked to muscle weakness and weight loss. Patients with COPD typically suffer from muscle mass loss, particularly in their lower limb muscles, especially during exacerbations and in moderate-to-severe stages[15]. The prevalence of sarcopenia (a condition characterized by significant muscle loss) is high in COPD patients (ranging from 15% to 55%)[29], and low body mass index (BMI) and smoking are contributing factors. The rates of sarcopenia increase with worsening BMI, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and BODE (Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise capacity) index quartiles, indicating a poorer prognosis[10]. Ventilatory and peripheral muscles are affected, highlighting the importance of addressing muscle health in COPD management. Such an approach can help reduce hospitalization and mortality risks and improve overall quality of life[75].

The 2018 EWGSOP2 guidelines provide a detailed framework for diagnosing and assessing sarcopenia, integrating the SARC-F questionnaire with evaluations of muscle strength, muscle quantity or quality, and physical performance to enhance diagnostic precision and management[38]. Sarcopenia is classified into three stages: probable sarcopenia, sarcopenia, and severe sarcopenia. Probable sarcopenia is primarily identified by reduced muscle strength. If the simultaneous presence of reduced muscle quantity or quality is identified, then a diagnosis of sarcopenia is confirmed. The most advanced stage, severe sarcopenia, is characterized by meeting all three diagnostic criteria: reduced muscle mass, reduced muscle strength, and diminished physical performance, as summarized in Table 1[38].

Table 1.

Sarcopenia operational definition and cutoff points by European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2)[36]

| Parameters | Test and cutoff | Diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ||

| Reduced muscle strength1 | Grip strength: <27 kg | Grip strength: <16 kg | Probable sarcopenia |

| Chair standing: >15 s for five rises | Chair standing: >15 s for five rises | ||

| Reduced muscle quantity or quality2 | ASM: <20 kg | ASM: <15 kg | Sarcopenia |

| ASM/height2: <7.0 kg/m2 | ASM/height2: <5.5 kg/m2 | ||

| Reduced muscle performance3 | Gait speed: ≤0.8 m/s | Severe sarcopenia | |

| Short physical performance battery: ≤8 points | |||

| Timed up-and-go test: ≥20 s | |||

| 400-meter walk test: incomplete or ≥6 min for completion | |||

ASM: appendicular skeletal muscle mass; probable Sarcopenia: 1; sarcopenia: 1 and 2; severe sarcopenia: 1–3.

Imaging techniques

To diagnose sarcopenia, various imaging techniques are used, such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound[76]. CT and MRI are the best methods for analyzing body composition since they provide highly accurate 3D body imaging. Although concerns about radiation exposure often restrict the use of CT to 2D slices, it remains a reliable option. MRI uses non-ionizing radiation to assess muscle composition, but it faces challenges in cost and standardization. Ultrasound is portable, but it lacks standardized validation[76,77]. This is mainly due to variability in ultrasonography technique and measurements, alongside the absence of globally applicable normative data, which undermines its reliability. Moreover, arbitrary cutoff points add complexity to its clinical application, necessitating concerted efforts to establish consistency and enhance its utility[78].

DEXA is vital in muscle mass assessment and body composition due to its accuracy and tissue differentiation capability. It is cost-effective and emits lower radiation than CT, making it essential for a comprehensive body composition evaluation. DEXA measures muscle mass, emphasizing indices like appendicular lean mass[16] and height2-adjusted ALM index (ALMI) with EWGSOP-proposed cutoffs (ALMI < 7.0 kg/m2 for men, < 5.5 kg/m2 for women). However, the predictive value of ALMI is debated mainly due to limitations in estimating truncal fat/muscle. It may not be ideal for assessing visceral fat or muscle quality compared to CT/MRI. However, it was noted that variations in brands of DEXA equipment and patient-specific factors contribute to inconsistent results, making data comparison more challenging, and adjustments like ASM/ht2 may be less accurate in individuals with high BMI[38]. Nonetheless, it remains valuable in clinically confirming sarcopenia, especially when other causes of low muscle strength are ruled out.[79–81]. Densitometry, including air displacement plethysmography, offers precision but lacks regional data, as it only measures overall body density, including total body fat and lean tissue[77]. However, it cannot measure their distribution, such as the anterior compartment of the thigh, due to more significant muscle loss in lower limbs[81]. Bio-electrical impedance analysis (BIA) faces limitations in measuring visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and ectopic fat. DEXA excels in whole-body fat and lean tissue measurement but shows diminished accuracy for VAT, particularly in obese individuals. CT and quantitative MRI excel in quantifying ectopic fat. Each method has distinct strengths, with DEXA remaining prominent for comprehensive assessment[77].

Anthropometric measurements, muscle strength, and physical performance tests

In addition to diagnosing sarcopenia, DEXA can also be used to monitor osteoporosis[82], which is particularly crucial for sarcopenic COPD patients who are more susceptible to it[83]. In cases where DEXA access is limited, clinicians can rely on anthropometric measurements like BMI, calf circumference, mid-upper arm circumference, and skin fold thickness. Although these measurements correlate with muscle mass and health status, accuracy diminishes with age due to fat distribution changes and skin elasticity loss. Adjusting for age, sex, or BMI can improve correlation with DEXA-measured lean mass[84]. Despite their limitations, CT, MRI, and US imaging allow detailed characterization of regional muscle changes undetectable by DEXA or BIA. This is crucial for understanding muscle composition alterations like fat infiltration in conditions such as sarcopenic obesity[85].

Alongside imaging, muscle strength, anthropometric, and physical performance tests are essential in diagnosing sarcopenia[86]. Various validated tools exist for muscle strength measurement, including handgrip strength measured via a dynamometer and the chair stand test, which assesses lower-extremity strength by measuring the time to rise from a seated position. Additionally, physical performance tests such as the stair climb power test (SCPT), timed get up-and-go (TGUG) test, and short physical performance battery evaluate leg power, speed, and lower-extremity function, respectively. Also, the usual gait speed, the 6-minute walk test (6MWD), and the SCPT are recommended[87–89]. Handgrip strength <27 kg for men and <16 kg for women, or a gait speed <0.8 m/s in the 6MWD, serve as cutoff parameters for sarcopenia[12,90]. Additionally, recent studies indicate the TGUG test, with a cutoff value of >10.38 s, is a good predictor of sarcopenia[91]. Consequently, incorporating regular sarcopenia screening into routine COPD management, supported by the availability of diverse screening and diagnostic tools, can enable early detection and timely interventions. This approach can help slow muscle loss, enhance quality of life, and reduce the risk of further complications.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers associated with muscle mass, strength, and function encompass various indicators, ranging from inflammatory biomarkers to clinical parameters, hormones, oxidative damage products, and antioxidants. Among these markers, emerging ones like plasma concentrations of procollagen type III N-terminal peptide (P3NP) have garnered attention for their potential to reflect the ongoing process of skeletal muscle remodeling. P3NP, generated through the cleavage of procollagen type III, contributes to the production of collagen III, an essential protein found in soft connective tissues, skin, and muscle. Monitoring P3NP levels offers valuable insights into tissue dynamics, potentially indicating muscle health and adaptation[92]. NMJ biomarkers like arginine levels are significant as enhanced neurotrypsin-induced agrin cleavage destabilizes NMJs, initiating sarcopenia[93].

Research exploring the efficacy of the serum creatinine (Cr) to serum CysC ratio, termed the sarcopenia index (SI), in predicting clinical outcomes among elderly patients experiencing acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) shows promise. This index, proposed as a surrogate marker for sarcopenia, correlates with muscle mass and adverse outcomes in COPD. Specifically, a Cr/CysC ratio below 0.71 indicates an increased risk of AECOPD exacerbations, providing a cost-effective method for assessing sarcopenia[94–97]. However, Tang et al[98] indicated that the Cr/CysC ratio, being a potentially valuable biomarker for predicting adverse outcomes in the elderly, may not serve as a reliable surrogate marker for sarcopenia because the common comorbid condition in COPD[99], such as chronic kidney disease[100], can also influence serum Cr levels. While serum Cr and CysC are readily measured in clinical practice, more robust validation is needed before their use can be recommended in clinical settings[26]. Exploring how Cr/CysC ratios correlate with various comorbid conditions could enhance their clinical applicability.

Urinary titin, correlating with blood markers and muscle atrophy in intensive care patients, also holds potential as a non-invasive biomarker for sarcopenia[26]. While individuals with COPD exhibit systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, there is an unexpected rise in the levels of the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD). However, the status of other antioxidant enzymes like catalase[101] and paraoxonase 1 presents conflicting findings. Notably, the total radical trapping antioxidant parameter emerges as a significant biomarker linked with muscle mass, strength, and physical performance in COPD patients, with reduced levels increasing the risk of sarcopenia. Furthermore, advanced oxidation protein products demonstrate associations with sarcopenia metrics, indicating potential pathways for oxidative damage in muscle tissues[102].

Recent research underscores the diagnostic promise of biomarkers like C-terminal agrin fragment-22 (CAF22), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF). In COPD, the fluctuating CAF22, BDNF, and GDNF reflect NMJ changes, highlighting its adaptability. Exercise-induced reduction in CAF22 levels may support NMJ repair, while diminished BDNF and GDNF levels suggest compromised NMJ repair in COPD, worsening sarcopenia. PR elevates NF levels, indicating exercise’s protective role in NMJ function[75]. MicroRNAs (miRs) also show promise due to their role in skeletal muscle health; mir-133a showed the strongest correlation with handgrip strength, while miR-133a, miR-434-3p, and miR-455-3p correlated most strongly with appendicular SMM index. Integrating these findings into clinical practice could enhance sarcopenia diagnosis and monitoring in the elderly[103]. IL-6, SPARC (osteonectin), MIF (macrophage migration inhibitory factor), and IGF-1 are potential muscle health and exercise response biomarkers. Plasma extracellular heat shock protein 72 (eHsp72) and circulating skeletal muscle-specific troponin T (sTnT) may also be helpful – elevated MIF levels in muscle damage hint at a link to glucose metabolism in sarcopenia. SPARC’s roles in muscle health and aging remain unexplored. IGF-1 activates muscle growth pathways and aids in regeneration. Serum sTnT levels rise post-muscle injury and in neuromuscular disorders but decline after strength training in older adults. This suggests its potential as an index for assessing exercise effects on muscle function. However, their association with COPD remains unproven[104,105].

While a range of diagnostic tools for sarcopenia in COPD are currently utilized in practice, we identified a critical need for further investigation, emphasizing the creation of dependable and consistent diagnostic tools. Key priorities include evaluating and defining standardized cutoff points for imaging and biomarkers to assess skeletal muscle, particularly in sarcopenic obesity.

Therapeutic interventions to address sarcopenia in COPD

The goal of treating and managing sarcopenia in COPD patients should be to supplement the diet’s lack of certain nutrients, like protein and vitamin D. This can be done through PA, dietary counseling, medicine, and supplements[28]. Researchers have made significant advances in understanding the benefits of PR programs for patients with various respiratory conditions. This includes improvements in exercise tolerance and quality of life for individuals with chronic respiratory disorders and those critically ill with COPD, regardless of their muscle mass or weight[28,106,107]. Figure 1 summarizes the therapeutic interventions.

Figure 1.

An overview of therapeutic interventions for sarcopenia in COPD, including pulmonary rehabilitation, exercise regimens, dietary supplements, hormone therapies, and emerging therapies (created with canva.com).

Pulmonary rehabilitation

PR helps patients improve their ability to exercise and enhances their quality of life, reducing symptoms like dyspnea. It includes exercise, education, behavior modification, and nutritional therapy as part of a comprehensive treatment approach[28]. The PR program, lasting 8 weeks, involves multidisciplinary exercises and education sessions, including supervised and home sessions[108]. During PR, the patient receives psychological support regarding the treatment plan to relieve symptoms (malaise and dyspnea), cut on medical care (especially bed days), and exercise to increase physical strength. The International Working Group on Sarcopenia criteria produced the highest frequency of sarcopenia in COPD patients, regardless of PR status, according to a study on sarcopenia criteria. According to the Asian Working Group on sarcopenia (AWGS) and EWGSOP criteria, the incidence of sarcopenia in COPD patients was 21.82% before PR; it was subsequently reduced to 7.27%. PR dramatically decreased the incidence of sarcopenia in those with COPD, regardless of the parameters.

A study was conducted to see how PR improved the PA of patients with sarcopenia in COPD, which involves aerobic exercises, counseling, and emotional support, with at least three sessions lasting 2–4 h each week. The exercise regimen included brisk walking, using a treadmill or a stationary bicycle for at least 30 min to reach 60%–80% of the peak work rate. During the program, the patient’s walking speed was measured with a 4-meter walking test (m/s), and their step count was recorded (steps/day). The results showed a significant increase in walking speed after PR, with a 24% improvement. This improvement was seen in 39 out of the 55 patients studied. Yet, well-planned clinical trials with an impartial evaluation of PA in COPD patients are required[109–111]. However, existing literature also highlights some contrasting results; a study by Jones et al[108] demonstrated that sarcopenia in COPD did not have an impact on response to PR in the majority of the patients, while in some patients, it did lead to the reversal of sarcopenia, specifically, those with an SMM index[86] or functional performance near the cutoff threshold at baseline.

Exercise regimens

Exercise is fundamental in managing both COPD and sarcopenia. In COPD, aerobic exercise enhances tolerance, breathlessness, and muscle fiber composition, while interval training offers alternatives for those struggling with continuous exertion. Progressive strength training similarly improves muscle mass and strength. Resistance, aerobic, balance, and flexibility exercises are essential for sarcopenia, preventing muscle wasting and enhancing function. Determining exercise intensity can be challenging, but methods like the 6-min walk test,[112] perceived exertion[112] rating, and heart rate monitoring are commonly used alternatives to VO2 max testing, which is crucial for exercise training. Monitoring for exercise-induced desaturation, particularly in severe COPD cases, is essential. If oxygen levels drop below 90%, halting aerobic activity is advised. Additionally, considering air pollution’s impact on lung health, exercising indoors may be necessary for the elderly living in areas with high fine particle levels. Combining aerobic and resistance exercises is recommended, with circuit training showing promising results in improving mobility and muscle function in the elderly[26,28,113]. However, some studies reported conflicting findings, with some reporting enhanced exercise tolerance and reduced breathlessness, yet no change in muscle mass[114]. In contrast, others reveal no difference in training outcomes, regardless of oxygen supplementation[115].

The findings of our study highlight the quintessential role of structured PR programs. When we integrate RT and aerobic exercises, we see the enhancement of muscle function and a low incidence of sarcopenia in individuals with COPD. It is, therefore, advisable that healthcare professionals appropriately prescribe PR for patients with concomitant sarcopenia and COPD, tailoring exercise programs according to each patient’s capabilities and progressively intensifying the regimen (progressive overload) as tolerated. PR promotes physical function and bolsters respiratory capacity, providing a multifaceted benefit for managing COPD. This strategy could be employed through hospital-based or community-centered programs and expanded to include home-based activities, which may improve patient accessibility and long-term adherence.

Inspiratory muscle training

An analysis found six studies on inspiratory muscle training (IMT) that fit the criteria of being randomized trials with sarcopenia in COPD patients, having a treatment method and control group, using a resistance, threshold, or current device for IMT, and measuring physiological (such as inspiratory muscle strength) and clinical outcomes (such as dyspnea score). These studies involved 169 COPD patients, with each study having between 17 and 32 subjects, lasting from 2 months to 1 year. The results showed positive outcomes, supporting the effectiveness of IMT in improving inspiratory muscle function, exercise performance, and reducing dyspnea[116]. IMT could significantly benefit patients with COPD who experience significant dyspnea and inspiratory muscle weakness. When IMT is routinely integrated into the management of patients with concomitant sarcopenia and COPD, clinicians can address both respiratory function and muscle maintenance. Training programs should be personalized, with gradual resistance increases, and paired with regular assessments of inspiratory muscle strength to track progress and adjust intensity as needed.

Dietary supplements, weight loss management, and resistance training

Various clinical studies show that dietary supplements exceptionally high in whey protein, leucine, essential amino acids, and vitamin D maintain respiratory muscle strength and increase fat-free mass (FFM) in obese/frail older adults, reducing the risk of sarcopenia. The most crucial dietary supplementation is leucine, a BCAA with several benefits in curbing sarcopenia. This includes stimulating muscle protein synthesis and enhancing myosatellite cells. Several other benefits of leucine are attributable to abating the muscle loss stemming from sarcopenia[117,118]. Increased muscle protein turnover signaling in COPD, or enhanced myogenic signaling, indicates molecular changes related to muscle remodeling and repair. This phenomenon is particularly noticeable in COPD patients who also have sarcopenia[119–123].

Although vitamin D supplementation for the control of sarcopenia has been controversial, there is considerable evidence in favor of using Vitamin D to improve sarcopenia. For instance, Okubo et al[124] discovered that vitamin D supplementation (2000 IU once daily for 12 months) may significantly increase the muscle mass and grip strength of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Furthermore, adding Vitamin D with protein supplementation and exercise showed a substantial increment in grip strength and a trend toward increasing muscle mass[125].

However, in a study by Prokopidis et al, which included 10 randomized controlled trials, no significant improvement in muscle strength or muscle mass was observed in the vitamin D supplement group[126]. The need to investigate what factors contribute to variability in response to vitamin D supplementation for sarcopenia management is urgent. Including larger, more diverse sample sizes would comprehensively evaluate vitamin D’s efficacy.

Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB), a metabolite of the BCAA leucine, is popular among athletes and bodybuilders for increasing strength, muscle mass, and exercise performance. HMB modulates chronic inflammation by reducing the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and inhibiting the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of the activated B cells (NF-κB), which is a signaling pathway that is crucial in the inflammatory response[127]. Studies show its supplements can prevent muscle damage and loss in healthy individuals and those with chronic diseases. HMB also helps older adults maintain muscle mass and may prevent atrophy from factors like bed rest. However, more research is needed to confirm its effectiveness in pathological conditions[128,129].

Other nutritional supplements that can treat sarcopenia include probiotics and anti-inflammatory nutrients[130]. Liu et al found in their study that the levels of Prevotella in the intestinal tract of multi-ethnic patients with sarcopenia in western China were significantly reduced compared to the control group[131]. A systematic review including 10 clinical investigation studies found that lactobacillus and bifidobacteria may help restore age-related muscle atrophy[132]. Chen et al found that Lactobacillus casei may regulate the occurrence and progression of age-related sarcopenia through the gut–muscle axis[133]. Furthermore, Omega 3 supplementation can help prevent or improve sarcopenia progression[134].

Moreover, weight loss management and resistance training are the most important protective measures to slow muscle mass and strength decline. A study by Stoever et al showed that resistance training improved the grip strength of the trial population by 9%[135]. Cunha et al found that RT could improve physical function and increase SMM[136]. Shen et al compared the effectiveness of different exercise interventions for elderly patients with sarcopenia. They found that resistance training, in combination with balance and aerobic training, was the most efficacious intervention in improving the quality of life[137]. Park et al conducted a 15-week compound exercise program for female sarcopenia patients who were older than 60, and the compound exercise group showed improvements in inflammation and anabolic effects of secondary sarcopenia[138]. Yoga has proven to improve protein utilization and help maintain the balance between protein breakdown and synthesis, which may benefit individuals with sarcopenia[139].

The quality of amino acids in food is essential in stimulating protein synthesis[140] and aiming for multimodal interventions needed to correct energy and protein imbalances, specific nutrient deficiencies, androgen depletion, and targeted exercise. In addition, interventions that consider the course of the disease are likely to be essential to effectively addressing the common and costly nutritional problem associated with COPD[7]. Therefore, clinicians should consider including targeted supplements such as whey protein, vitamin D, and leucine in the treatment regimen, particularly for those who have difficulty achieving adequate nutrition through diet alone, and advising routine follow-ups will enable healthcare providers to modify dietary recommendations to meet the evolving needs of each patient.

Hormone therapies

GH plays a vital role in encouraging muscle growth and development by engaging various signaling pathways that regulate muscle mass. One of the key pathways involved is the PI3K/AKT pathway, which triggers protein synthesis and prevents protein breakdown. Notably, PA activates this pathway, which is linked to the IGF-I and insulin receptors. Both insulin and IGF-I support protein synthesis in skeletal muscle. The AKT pathway has three isoforms (AKT1, AKT2, and AKT3), with AKT1 being particularly important for growth regulation. Protein production in the body is influenced by the muscle’s energy levels, which are essential for ATP-dependent processes. This synthesis is carefully regulated.

Over the years, studies[26,141,142] have demonstrated the potential benefits of GH supplementation in COPD patients, including increases in body weight, muscle mass, and respiratory muscle strength, albeit with inconsistent results. However, clinicians must exercise caution while prescribing GH supplementation as it is linked to significant adverse effects, including insulin resistance, cardiovascular complications, gynecomastia, carpal tunnel syndrome, soft tissue edema, and arthralgias[143].

Moreover, in both healthy young adults and sarcopenic patients, the use of testosterone by administering nandrolone decanoate (ND) through intramuscular injection while undergoing PR led to an increase in FFM without enhancing exercise capacity compared to those who did not receive the treatment. However, ND improved exercise performance among patients receiving glucocorticoid therapy. The long-term effects of testosterone, another FFM booster, and post-supplement cessation remain uncertain. Nevertheless, as with GH, testosterone usage also carries the risk of dose-dependent severe side effects on the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal (GI), and endocrine systems, underscoring the importance of careful hormone administration. These compounds encompass anabolic steroids, which potentially serve as an intermediate measure to enhance healing outcomes[26,141,142].

Although these therapies may enhance healing and improve outcomes, their use requires careful consideration. Clinicians must weigh the potential benefits of muscle mass against cardiovascular and endocrine risks. However, owing to the plethora of adverse health concerns, no sex steroid supplementation has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of sarcopenia.

Hormones undoubtedly play a critical role in the pathogenesis of sarcopenia; further longitudinal research is needed to explore how fluctuations in hormone levels over a life course contribute to sarcopenia progression and to identify opportunities for effective interventions tailored to different life stages.

Ghrelin and antioxidant therapies

Ghrelin was discovered in 1999 as an endogenous ligand for GH secretagogue receptor 1a (GHSR1a). Because of different advantageous impacts on the metabolism of multiple systems, the pharmacological focus of the endogenous ghrelin framework is broadly viewed as an essential way to deal with anorexia, cachexia, sarcopenia, cardiomyopathy, neurodegenerative problems, renal and pneumonic infection, GI disorders, provocative problems, and metabolic disorder treatment[144]. Ghrelin promotes appetite and feeding, therefore helping to prevent weight loss. This effect could be beneficial in the treatment of sarcopenia, particularly in COPD patients who have reduced appetite and inadequate calorie intake[143]. A study[144] reported improved exercise capacity in COPD patients following ghrelin supplementation, although another study[145] found no improvement in muscle strength or functionality. For sarcopenic patients to continue to have healthy skeletal muscle function, it is essential to regulate their levels of ROS and reactive nitrogen species[146]. These molecules are critical for glucose absorption and muscular contraction, and their concentration rises with exercise. To guard against oxidative damage, the body possesses natural antioxidant defenses. Options for treating oxidative stress include increasing the synthesis of antioxidant proteins like SOD and Gpx and scavenging free radicals. Also, glutathione is essential for muscle cells to retain the right balance of antioxidants. In COPD patients with sarcopenia, supplements such as N-acetyl cysteine can assist in increasing glutathione levels, which lowers oxidative stress and improves muscle fatigue. Furthermore, treatment with a glutathione precursor (F1) reduces lipid peroxidation, enhances the reduced glutathione (GSH) to oxidized glutathione (GSSG) GSH/GSSG ratio, lowers IL-6, and raises Akt phosphorylation, suggesting that the Akt/mTOR pathway plays a role in protein synthesis signaling. Although antioxidant therapies should not be considered a replacement for primary treatments, they may serve as a complementary approach by alleviating muscle fatigue and supporting overall muscle function.

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) uses electrodes applied to the skin to stimulate specific muscles externally, causing contractions that are not controlled. NMES is a valuable tool for sarcopenic patient education because of its portability, low ventilatory burden, low side effects, and suitability for immobile patients. It can be used as a frequent treatment at home[145].

Emerging therapies

Several notable emerging therapies target the pathways linked to sarcopenia, therefore acting as effective treatment options.

Selective androgen receptor modulators and selective estrogen receptor modulators

SARMs are non-steroidal, tissue-specific, nonvirilizing, nonaromatizable, and orally active anabolic drugs that increase muscle mass and enhance physical function in healthy and sick persons. SARMs work on the same muscle-building pathways as traditional steroid androgens but without causing unwanted side effects on the prostate, skin, and hair at doses that produce muscle growth and improved function. They may also offer a treatment for cancer, cachexia, and muscle wasting[147]. SERMs are structurally different compounds that interact with intracellular estrogen receptors in target organs as estrogen receptor agonists or antagonists[148]. Just like SARMs have relatively fewer side effects than their androgen counterparts, SERMs also have fewer side effects than estrogen itself. While evidence on the effects of SERMs on muscle mass and strength remains limited, research has shown that SERMs can help maintain body weight and increase FFM over extended periods in older post-menopausal women, with only minor side effects[149,150].

However, the FDA has not approved SARMS for sarcopenia due to inconsistent muscle function results[150]. Future RCTs testing its efficacy and safety compared to other pharmacological drugs for sarcopenia may unveil their true potential. It is, therefore, imperative for clinicians to stay up to date on these ground-breaking novel therapies, as they may soon be taught in regular medical practice for patients with severe sarcopenia or those who do not respond to conventional treatment options.

MSTN inhibitors

MSTN, also known as growth differentiation factor-8, inhibits muscle growth by activating a pathway that promotes protein breakdown and muscle atrophy[151]. Blocking MSTN has become a therapeutic focus, with drugs designed to prevent MSTN binding or signaling to its receptors. Notable drugs, including landogrozumab[152] and trevogrumab[153], monoclonal antibodies specifically targeting MSTN, showed mixed results in early clinical trials by increasing muscle mass,[49,154] but not consistently improving muscle function. SRK-015, another MSTN inhibitor, remains in trials and shows promise for spinal muscular atrophy[155].

Bimagrumab[156] is another medicine that is an entirely human monoclonal immunizer that hinders the activin type II receptors, inhibiting MSTN’s function and other negative skeletal muscle regulators. Over 16 weeks, bimagrumab treatment safely enhances SMM and mobility for those with slow walking speeds in older patients with sarcopenia. However, functional capacity does not improve in patients with poor muscle mass and COPD[157,158]. Furthermore, soluble forms of activin A receptor type 2A (ACVR2) drugs like ramatercept (ACE-031) act as competitive ACVR2 ligands to inhibit MSTN signaling[159]. Ramatercept initially increased muscle fiber growth in mouse models but had to be discontinued due to adverse events unrelated to muscle, such as epistaxis, telangiectasias, gum bleeding, and erythema[160,161]. ACE-2494, a modified version of ACE-031, showed potential but was halted due to immune responses among trial participants[162].

Follistatin, a natural MSTN antagonist, binds MSTN to block its effects on muscle[163,164]. Researchers developed follistatin fusion proteins and gene therapies to harness its muscle-growth properties while aiming to reduce systemic side effects. Fusion proteins encompassing Acceleron Pharma-engineered proteins like FST288-Fc[165] and ACE-083[166] localize muscle growth effects[167], minimizing the potential side effects associated with systemic treatments. ACE-083 showed increased muscle volume in trials but limited functional improvements[168], leading to halted trials[169,170].

Moreover, regarding gene therapy, gene delivery of follistatin isoforms, such as FST-344, has shown encouraging results in conditions like Becker muscular dystrophy[171]. Early trials demonstrated muscle hypertrophy, reduced fibrosis, and improved muscle structure in patients with Becker muscular dystrophy and sporadic inclusion body myositis[172,173]. New advancements in vector engineering using adeno-associated viruses for muscle-specific expression also enhance the effectiveness and safety of follistatin gene therapies[112].

Although MSTN inhibition via drug and gene therapies holds the potential for muscle mass enhancement, achieving corresponding functional improvements has proven difficult. Each approach – targeting MSTN directly, employing receptor antagonists, or utilizing follistatin-based gene therapies – carries distinct advantages, disadvantages, and limitations. Ongoing research has been done to optimize these novel therapeutic approaches to achieve the highest possible efficacy with minimal adverse effects. This represents a critical advancement toward viable interventions for muscle-wasting conditions.

Tissue-engineered scaffolds

Since the skeletal muscle tissue has limited inherent regenerative capacity, external interventions are often required following damage. One of these extrinsic interventions includes tissue engineering (TE), which presents a promising strategy, employing three-dimensional biomaterial scaffolds designed to mimic the muscle’s natural extracellular matrix structure, which supports the growth and formation of new muscle tissue[174]. The design of effective scaffolds for skeletal muscle TE involves several considerations, such as replicating the structure, alignment, and environment of natural muscle to guide cell orientation and achieve functional muscle constructs.

Critical scaffold materials and technologies include natural polymers, such as fibrin, alginate, chitosan, and collagen, which are biocompatible and biodegradable with adjustable features that support muscle tissue formation by integrating growth factors and cell adhesion motifs[175,176]. Synthetic polymers, including PGA, PEG, and PCL, offer adjustable properties and customizable degradation rates, enhancing versatility and providing a more economical option for TE applications[176]. Hybrid and decellularized scaffolds combine natural and synthetic elements to balance compatibility and structural resilience.

Engineered muscle tissues are useful for drug testing. For example, a 3D bioengineered senescent muscle model developed by Rajabian et al[177] displayed signs of aged muscle (e.g., reduced regenerative capacity and metabolic alterations), creating a valuable platform for testing potential therapies for conditions like sarcopenia. Though not yet tailored specifically for sarcopenia, these TE strategies offer a foundation for developing future targeted treatments for age-related muscle loss as regenerative medicine advances.

Metformin

The rise in sarcopenia among the aging population necessitates the creation of preventive measures. An experiment involving calorie restriction revealed that the diabetes medication metformin, taken orally at doses of 100 or 300 mg/kg/day, was able to delay the onset of sarcopenia in 19–24-month-old rats by slowing muscle fiber deterioration and preventing necrosis, sclerotic changes, and damage to connective tissue. Metformin antidiabetic biguanide also improves the flow of nutrients, aids in fiber digestion, enhances muscle strength, and reverses age-related weight loss in rats[178].

While individual therapeutic approaches show promise, addressing the variations in findings requires thoroughly exploring their comparative effectiveness. It is crucial to investigate how each intervention, encompassing targeted nutrition, personalized exercise programs, novel pharmacological therapies, and psychological support, performs relative to others. The effectiveness of a combined therapeutic approach that integrates these interventions in managing and mitigating sarcopenia warrants examination. Understanding the long-term outcomes of integrated therapeutic strategies compared to individual interventions is essential to optimize sarcopenia management and improve patient outcomes.

Patient perspective and quality of life

Many COPD patients experience sarcopenia, and this combined condition can significantly deteriorate a patient’s quality of life. Simple tasks like walking, climbing stairs, and even self-care become daunting. COPD dispossesses patients of their independence and autonomy, leading to frustration and emotional distress[179]. On top of that, muscle weakness and fatigue worsen shortness of breath during activities, further restricting daily life significantly[180].

Increased risk of falls

A study by Lippi et al found that COPD patients have a higher risk of falls and fractures compared to the general population. Sarcopenia in COPD patients further increases the risk of osteopenia and osteoporosis, making it an independent risk factor for low bone mineral density[181].

Myokines and muscle function

In sarcopenic patients who experience a loss of muscle mass and strength, limited PA can decrease myokines’ release, signaling molecules produced by muscle cells[182]. Cigarette smoke exposure disrupts muscle function in COPD by increasing a protein called MSTN and decreasing another called Fndc5. This appears to happen through specific signaling pathways (p-Erk1/2 and p-Smad3/PGC-1α). These findings point to these pathways as potential targets for future therapies to prevent muscle weakness in COPD[183].

Cognitive impact of reduced myokine production

Myokines have been shown to play a crucial role in maintaining brain health, and their decreased production due to reduced PA in sarcopenic patients could negatively impact cognitive function. Exercise triggers the release of myokines from muscles. These travel through the bloodstream and directly influence the brain. Myokines promote brain cells’ growth, connections, and adaptability, ultimately sharpening memory, learning, and overall thinking abilities. However, inactivity, obesity, and aging can disrupt myokine production. This disrupts the link between muscles and the brain, potentially leading to cognitive decline[101].

Psychological effects and depression

A study by Zhenzhen Li et al found that older people in Western China with sarcopenia were more likely to feel sad or depressed. This was especially true for those with severe sarcopenia. The study also found that having fewer muscles was a more significant risk factor for feeling depressed than having weak muscles[184].

Barriers to healthcare in remote areas

Remote areas create a double burden for COPD patients, and distance limits healthcare access, while social/economic factors and healthcare system hurdles add further difficulty. These include a lack of transportation, insurance, complex medications, and side effects. Even a patient’s knowledge can affect their ability to get proper care[181].

Strategies for managing challenges

Fortunately, there are strategies to manage these challenges; incorporating an exercise program can be highly advantageous. This program should ideally include resistance training at least 2–3 times per week to build muscle mass, along with activities like walking, cycling, or swimming to improve cardiovascular health. Balance and flexibility training can also be crucial in reducing falls and enhancing mobility. Nutritional interventions, such as protein intake and adequate amounts of vitamin D and calcium, are also beneficial[185]. Advanced care planning designates a trusted healthcare surrogate to make decisions aligned with the patient’s values and goals. Additionally, by combining exercise and education, PR programs significantly improve the quality of life for those with breathing difficulties. Such programs can be combined with targeted medications, and for some, cognitive behavioral therapy may be recommended to manage stress and anxiety[186].

Assessing health-related quality of life

Studies on COPD often use questionnaires to assess patient health-related quality of life (HRQOL). The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ) are standard tools[187,188]. These questionnaires are more sensitive than generic HRQOL measures at detecting changes in a patient’s condition[188]. The CRQ is a famous research questionnaire measuring how chronic respiratory illness affects a person’s overall well-being. The SGRQ questionnaire assesses how respiratory problems affect a person’s daily life. It has questions about symptoms, limitations in activities, and overall well-being. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more incredible difficulty managing daily life due to respiratory issues. Each questionnaire has its strengths, and combining both generic and disease-specific tools in COPD and management can provide a more comprehensive picture of a patient’s well-being[187].

Personalized COPD exercise programs

COPD exercise programs should be personalized. Targeted resistance training strengthens muscles for patients with weak legs and moderate breathlessness, aiding daily activities. However, electrical muscle stimulation might be a gentler option for those with severe breathlessness. Whole-body exercises like walking or moderate-intensity cycling help patients limited by their heart rate. Exercise intensity is adjusted based on a cycling test to ensure safety and effectiveness for those limited by breathing[189]. Resistance training for at least 6 months and tailored nutrition significantly improve muscle strength and function in sarcopenia. This combined approach is more effective than either therapy alone. Early intervention with ongoing assessment and adjustments based on inflammation and disease state is critical to maximize recovery and quality of life[28,190].

Patient-centered approach

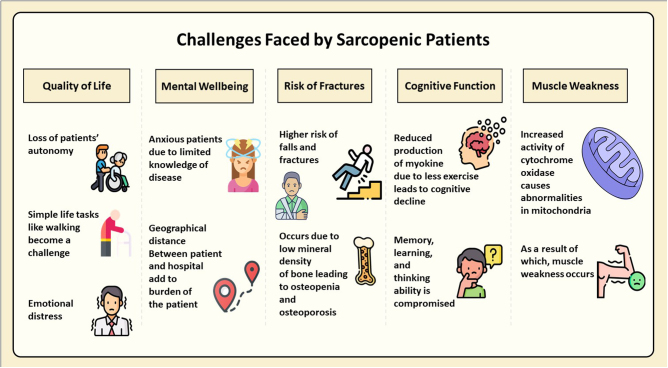

COPD patients associated with sarcopenia face a complex challenge. Open communication with their doctor is vital. A strong patient–doctor bond can help them manage COPD effectively, stick with treatment plans, and regain lost activity levels. This positive psychology goes beyond just the physical aspects of the disease[72]. A patient-centered approach that integrates tailored exercise programs, targeted nutritional interventions, and psychological support can significantly enhance quality of life. Early intervention and ongoing monitoring are essential, allowing for adjustments based on individual needs and disease progression[191,192]. Figure 2 summarizes the challenges faced by sarcopenic patients.

Figure 2.

Challenges faced by sarcopenic patients (created with Microsoft PowerPoint using icons from flaticon.com).

Conclusion

Sarcopenia in COPD presents a complex challenge. A patient-centered approach combining exercise programs, targeted nutrition, and psychological support can significantly improve the quality of life for patients. Early intervention, ongoing monitoring, and open communication between patients and healthcare providers are essential for optimizing treatment success. Further research is needed to assess the long-term efficacy and safety of emerging treatments, such as MSTN inhibitors and SARMs, in comparison to conventional approaches for mitigating sarcopenia in COPD patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Pranjal Kumar Singh for his assistance in the preparation of the figure. His involvement and support were greatly appreciated during the development of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Published online 16 July 2025

Contributor Information

Muhammad Hamza Khan, Email: ihamzakhan145@gmail.com.

Maham Fatima, Email: mahamfatima4567@gmail.com.

Ahmad Adnan, Email: walinad92@yahoo.com.

Alishba Jawaid, Email: alishjawaid00@gmail.com.

Syed Muhammad Hassan, Email: hassan1murshid@gmail.com.

Muhammad Talal, Email: muhammadtalal1999@gmail.com.

Shazia Rahim, Email: Shaziaraheem1@gmail.com.

Zaib Un Nisa Mughal, Email: mughalzaibunisa@gmail.com.

Aly Omer Patel, Email: Aliomerpatel17@outlook.com.

Achit Kumar Singh, Email: achitsingh007@gmail.com.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was not required for this review.

Consent

Informed consent was not required for this review.

Sources of funding

None.

Author contributions

M.H.K.: conceptualization, validation, supervision, writing – review and editing. M.F.: writing – review and editing, visualization. A.A.: writing – review and editing, supervision. A.J.: writing – original draft, visualization. S.M.H.: writing – original draft. M.T.: writing – review and editing. S.R.: writing – original draft. Z.U.N.M.: writing – original draft. A.O.P.: writing – original draft. A.K.S.: writing – original draft.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

None.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Muhammad Hamza Khan.

Provenance and peer review

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

References

- [1].Chen S, Kuhn M, Prettner K, et al. The global economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for 204 countries and territories in 2020-50: a health-augmented macroeconomic modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2023;11:e1183–e1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Boers E, Barrett M, Su JG, et al. Global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease through 2050. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2346598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chen H, Luo X, Du Y, et al. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease in adults aged 40 years and above: data from NHANES 2013-2018. BMC Pulm Med 2023;23:318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Agarwal AK, Raja A, Brown BD. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441988/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Upadhyay P, Wu CW, Pham A, et al. Animal models and mechanisms of tobacco smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 2023;26:275–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Miravitlles M, Ribera A. Understanding the impact of symptoms on the burden of COPD. Respir Res 2017;18:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Collins PF, Yang IA, Chang YC, et al. Nutritional support in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): an evidence update. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:S2230–S2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stage KB, Middelboe T, Stage TB, et al. Depression in COPD–management and quality of life considerations. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2006;1:315–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effects beyond the lungs. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Costa TM, Costa FM, Moreira CA, et al. Sarcopenia in COPD: relationship with COPD severity and prognosis. J Bras Pneumol Sep-Oct 2015;41:415–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA. Sarcopenia. Lancet 2019;393:2636–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tsekoura M, Tsepis E, Billis E, et al. Sarcopenia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a study of prevalence and associated factors in Western Greek population. Lung India 2020;37:479–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Choi YJ, Kim T, Park HJ, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with sarcopenia. Life (Basel) 2023;13:1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lee DW, Choi EY. Sarcopenia as an independent risk factor for decreased BMD in COPD patients: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys IV and V (2008-2011). PLoS One 2016;11:e0164303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Benz E, Trajanoska K, Lahousse L, et al. Sarcopenia in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28:190049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:392–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Proietti M, Cesari M. Frailty: what is It? Adv Exp Med Biol 2020;1216:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381:752–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yin L, Li N, Jia W, et al. Skeletal muscle atrophy: from mechanisms to treatments. Pharmacol Res 2021;172:105807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ma K, Huang F, Qiao R, et al. Pathogenesis of sarcopenia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front Physiol 2022;13:850964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Calvani R, Joseph AM, Adhihetty PJ, et al. Mitochondrial pathways in sarcopenia of aging and disuse muscle atrophy. Biol Chem 2013;394:393–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol Rev 2008;88:1379–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kurita N, Kamitani T, Wada O, et al. Disentangling associations between serum muscle biomarkers and sarcopenia in the presence of pain and inflammation among patients with osteoarthritis: the SPSS-OK study. J Clin Rheumatol 2021;27:56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Curcio F, Ferro G, Basile C, et al. Biomarkers in sarcopenia: a multifactorial approach. Exp Gerontol. 2016;85:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cho J, Choi Y, Sajgalik P, et al. Exercise as a therapeutic strategy for sarcopenia in heart failure: insights into underlying mechanisms. Cells 2020;9:2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].van Bakel SIJ, Gosker HR, Langen RC, et al. Towards personalized management of sarcopenia in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:25–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mandsager K, Harb S, Cremer P, et al. Association of cardiorespiratory fitness with long-term mortality among adults undergoing exercise treadmill testing. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e183605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kim SH, Shin MJ, Shin YB, et al. Sarcopenia associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Bone Metab 2019;26:65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sepulveda-Loyola W, Osadnik C, Phu S, et al. Diagnosis, prevalence, and clinical impact of sarcopenia in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020;11:1164–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hanlon P, Guo X, McGhee E, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, trajectories, and clinical outcomes for frailty in COPD. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2023;33:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yu Z, He J, Chen Y, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2024;19:e0300730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhou J, Liu Y, Yang F, et al. Risk factors of sarcopenia in COPD patients: a meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2024;19:1613–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Huang W-J, Ko C-Y. Systematic review and meta-analysis of nutrient supplements for treating sarcopenia in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Aging Clin Exp Res 2024;36:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Agha RA, Mathew G, Rashid R, et al. , TITAN Group. Transparency in the reporting of artificial intelligence – the TITAN guideline. Premier J Sci 2025;10:100082. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA – a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev 2019;4:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].He J, Li H, Yao J, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in patients with COPD through different musculature measurements: an updated meta-analysis and meta-regression. Front Nutr 2023;10:1137371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dudgeon D, Baracos VE. Physiological and functional failure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure and cancer: a debilitating intersection of sarcopenia, cachexia and breathlessness. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2016;10:236–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019;48:16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Burton LA, Sumukadas D. Optimal management of sarcopenia. Clin Interv Aging 2010;5:217–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Saad F, Rohrig G, von Haehling S, et al. Testosterone deficiency and testosterone treatment in older men. Gerontology 2017;63:144–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Siparsky PN, Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE, Jr. Muscle changes in aging: understanding sarcopenia. Sports Health 2014;6:36–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Geraci A, Calvani R, Ferri E, et al. Sarcopenia and menopause: the role of estradiol. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:682012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Choo YJ, Chang MC. Prevalence of sarcopenia among the elderly in Korea: a meta-analysis. J Prev Med Public Health 2021;54:96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dhillon RJ, Hasni S. Pathogenesis and management of Sarcopenia. Clin Geriatr Med 2017;33:17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Damanti S, Azzolino D, Roncaglione C, et al. Efficacy of nutritional interventions as stand-alone or synergistic treatments with exercise for the management of Sarcopenia. Nutrients 2019;11:1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kupisz-Urbańska M, Płudowski P, Marcinowska-Suchowierska E. Vitamin D deficiency in older patients-problems of Sarcopenia, drug interactions, management in deficiency. Nutrients 2021;13:1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Nan Y, Zhou Y, Dai Z, et al. Role of nutrition in patients with coexisting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sarcopenia. Front Nutr 2023;10:1214684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Degens H, Gayan-Ramirez G, and van Hees HW. Smoking-induced skeletal muscle dysfunction: from evidence to mechanisms. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:620–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wagner KR, Fleckenstein JL, Amato AA, et al. A phase I/IItrial of MYO-029 in adult subjects with muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol 2008;63:561–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]