Abstract

Increasing evidence indicates that the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) are correlated with the prognosis of various malignancies. This study aimed to evaluate the prognostic value of pre-treatment SII and LDH in patients with non-metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). We conducted a retrospective analysis of 756 patients with non-metastatic NPC. The optimal cut-off values for SII and LDH, determined using X-tile software, were 150 and 447, respectively. Independent prognostic factors for survival outcomes were identified using Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox regression analysis. Patients in the high SII group had significantly worse prognosis in 5-year OS (76.5 vs. 86.7%, p < 0.001), 5-year DMFS (77.3 vs. 85.4%, p < 0.001), and 5-year PFS (67.9 vs. 80.5%, p < 0.001) compared to the low SII group. Patients in the high LDH group had significantly worse prognosis in 5-year OS (72.1 vs. 85.0%, p < 0.001), 5-year DMFS (72.1 vs. 84.8%, p < 0.001), and 5-year PFS (63.7 vs. 77.7%, p < 0.001) compared to the low LDH group.Multivariate analysis showed that high SII and high LDH were significantly associated with poorer OS (p = 0.005 vs.p < 0.001), DMFS(p = 0.001 vs.p < 0.001), and PFS (p = 0.001 vs.p < 0.001). These results confirmed that both SII and LDH are independent prognostic factors for OS, DMFS, and PFS. In subgroup analysis, this predictive effect was more pronounced in locally advanced stages. Among patients with locally advanced NPC, the combination of SII and LDH showed the highest AUC values for predicting OS, DMFS, and PFS. Pre-treatment SII and LDH are important prognostic factors in patients with non-metastatic NPC. Furthermore, the combination of both provides a more accurate prognosis for patients with locally advanced NPC than either marker alone.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-14455-5.

Keywords: Serum lactate dehydrogenase, Systemic immune-inflammation index, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Prognosis

Subject terms: Cancer, Oncology

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignant tumor originating from the epithelial tissue of the nasopharyngeal mucosa, with a significant regional difference in incidence. According to data published by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 2020, approximately 133,354 new NPC cases and 80,008 NPC-related deaths were reported worldwide in 2018. Among them, China had 60,558 new cases of NPC, accounting for 46.8% of the global total1. With the application of intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), the local control and overall survival(OS) of NPC patients have significantly improved. Nevertheless, local recurrence and distant metastasis remain the primary causes of treatment failure2. This improvement is particularly notable in patients with early-stage NPC. However, treatment outcomes remain unsatisfactory for patients with locally advanced NPC. Moreover, over 70% of newly diagnosed cases present at a locally advanced stage. Therefore, accurately assessing prognosis before treatment, particularly in locally advanced patients, is critical to improving clinical management.

At present, the TNM staging system remains the gold standard for guiding treatment decisions and assessing prognosis in NPC patients. However, patients with the same stage of NPC often have different clinical outcomes despite undergoing similar treatment regimens. This may be attributed to TNM staging does not account for the biological heterogeneity of the tumor or the differences in patients’ responses to radiotherapy3. Therefore, identifying reliable prognostic indicators and individualized risk stratification is crucial for improving the clinical management of NPC.

In 1863, Virchow proposed that chronic inflammation affects tumor development4. Nowadays, many inflammatory biomarkers have been reported as prognostic factors for various cancers5,6. The systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), calculated as neutrophils (×10^9/L) × platelets (×10^9/L) / lymphocytes count (×10^9/L), was first introduced in hepatocellular carcinoma research in 2014 and has since been widely recognized as a prognostic marker in various malignancies5,7. SII is closely related to the prognosis of various solid tumors, such as lung cancer8 breast cancer9 prostate cancer10 bladder cancer11. Recently, several studies have explored the relationship between SII and prognosis in NPC; however, the results have been inconsistent12–17. For instance, some studies reported SII as an independent prognostic factor in NPC12–14. However, other studies15–17 reported conflicting results. Moreover, these studies primarily focused on only one or two endpoint outcomes.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) has been considered a reliable prognostic factor for NPC in multiple studies. One large-scale study indicated that elevated pre-treatment LDH levels are associated with poorer OS and progression-free survival (PFS)18. Zhang et al. found that dynamic changes in LDH levels during treatment could predict PFS in patients with recurrent or metastatic NPC19. Another study show that baseline LDH was associated with OS in NPC patients, although it was not an independent predictor of PFS20. Zhou et al. found that pre-treatment LDH levels correlated with the clinical stage of NPC, and patients with higher pre-treatment LDH levels exhibited poorer poorer 4-year OS, disease-free survival (DFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) rates. However, in multivariate analysis, only post-treatment LDH levels were identified as independent prognostic factors for OS21. Therefore, it is necessary to further investigate the impact of LDH levels on the prognosis of NPC patients.

LDH and the neutrophils, platelets, and lymphocytes values used to calculate the SII are easy to obtain and inexpensive to test. Consequently, we conducted a retrospective study on non-metastatic NPC patients who received IMRT with or without chemotherapy. The aim of this study was to investigate the predictive value of SII and LDH for various survival outcomes in NPC patients.

Materials and methods

Patient population

This was a retrospective study and clinical data of 756 non-metastatic NPC patients and treated at our institution from July 2005 to January 2010 were collected. Inclusion criteria: (1) Pathologically confirmed NPC, (2) First-time radiotherapy with IMRT technique, (3) Complete blood routine and biochemistry reports within one week prior to treatment, (4) Complete clinical data for TNM-8 staging. Exclusion criteria: (1) Combined blood diseases and other tumors, (2) Immunological and infectious diseases.

Basic clinical information before treatment was collected, including gender, age, T stage, N stage, clinical stage, pathological type, whether chemotherapy was administered, pre-treatment peripheral blood neutrophils, platelets, lymphocytes count, LDH level, and follow-up information. The calculation method for SII is: neutrophils (×10^9/L) × platelets (×10^9/L) / lymphocytes count (×10^9/L).

Treatment protocol and follow-up

All patients were treated with IMRT, and the detailed protocol and dose of IMRT have been described in previous studies22. The primary endpoints were overall survival (OS) and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), while the secondary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS) and local-regional recurrence-free survival (LRRFS). Patients were followed up every 2–3 months for the first 2 years after treatment, every 6 months for years 3–5, and annually thereafter. Follow-up continued until January 2010, with a median follow-up time of 92 months. All participants routinely underwent follow-up abdominal ultrasound, chest X-ray, nasopharyngoscopy, nasopharyngeal MRI, and whole-body bone ECT scan.

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian Provincial Cancer Hospital. Due to the retrospective nature of the research, the Ethics Committee of Fujian Provincial Cancer Hospital waived the requirement for informed consent.

Statistical analysis

The critical values of SII and LDH were determined using X-tile software. X-tile was selected for its capability to maximize survival differences between groups23. Age was dichotomized into a binary variable based on the median value. The relationships between SII, LDH and clinical datas was analyzed using the Chi-square test (with count data expressed as frequencies or percentages, and comparisons made using the Chi-square test). Survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank test. The proportional hazards assumption for SII and LDH was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals tests. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify independent prognostic factors. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Patients were classified into SII–LDH groups based on combinations of different SII and LDH values. The area under the ROC curve was compared to evaluate the diagnostic performance of SII-LDH, PNI, LDH, age, and N stage for OS, DMFS, and PFS. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 23.0 and R 4.1.2 software.

Results

Patient characteristics

Baseline clinical characteristics of study participants in different groups are presented in (Table 1). A total of 756 individuals were included in the study, consisting of 555 males (73.4%) and 201 females (26.6%). The median age at diagnosis was 45 years( range, 11–79 years). All patients were re-staged according to the current TNM-8 Criteria, with 214 (28.3%) classified as stage I-II and 542 (71.7%) as stage III-IVa. Based on the analysis results from X-tile software, the optimal cut-off values were 447 for SII and 150 for LDH. Comparing the baseline characteristics between the groups, there were no significant differences in clinical characteristics between different LDH groups, except for N stage. In the different SII groups, there were no significant differences in clinical characteristics except for T stage and TNM stage.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical variables of the study participants stratified by SII and LDH groups.

| Variable | Total n (%) | LDH | P | SII | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 150 | > 150 | ≤ 447 | > 447 | ||||

| Sex | 0.113 | 0.075 | |||||

| Male | 555(73.4) | 352(71.5) | 203(76.9) | 206(69.8) | 349(75.7) | ||

| Female | 201(26.6) | 140(28.5) | 61(23.1) | 89(30.2) | 112(24.3) | ||

| Age(years) | 0.053 | 0.523 | |||||

| ≤ 45 | 380(50.3) | 260(52.8) | 120(45.5) | 144(48.8) | 236(51.2) | ||

| > 45 | 376(49.7) | 232(47.2) | 144(54.5) | 151(51.2) | 225(48.8) | ||

| Histologic type | 0.878 | 0.522 | |||||

| I | 8(1.1) | 5(1.0) | 3(1.1) | 4(1.4) | 4(0.9) | ||

| II + III | 748(98.9) | 487(99.0) | 261(98.9) | 291(98.6) | 457(99.1) | ||

| T category | |||||||

| T1-2 | 323(42.7) | 209(42.5) | 114(43.2) | 0.852 | 156(52.9) | 167(36.2) | < 0.001 |

| T3-4 | 433(57.3) | 283(57.5) | 150(56.8) | 139(47.1) | 294(63.8) | ||

| N category | |||||||

| N0-1 | 495(65.5) | 339(68.9) | 156(59.1) | 0.007 | 205(69.5) | 290(62.9) | 0.063 |

| N2-3 | 261(34.5) | 153(31.1) | 108(40.9) | 90(30.5) | 171(37.1) | ||

| TNM stage | 0.644 | ||||||

| I + II | 214(28.3) | 142(28.9) | 72(27.3) | 105(35.6) | 109(23.6) | < 0.001 | |

| III + IVa | 542(71.7) | 350(71.1) | 192(72.7) | 190(64.6) | 352(76.4) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 0.764 | ||||||

| No | 187(24.7) | 120(22.4) | 67(25.4) | 84(28.5) | 103(22.3) | 0.057 | |

| Yes | 569(75.3) | 372(75.6) | 197(74.6) | 211(71.5) | 358(77.7) | ||

SII systemic immune-inflammation index, prognostic nutritional index, LDH lactate dehydrogenase.

Survival and prognostic values of SII and LDH

The overall median follow-up time was 92 months (range, 1-146 months). In the end, 186 patients (24.6%) died, and 263 (34.8%) experienced tumor progression, with 71 (9.4%) having local-regional recurrence and 158 (20.9%) having distant metastasis. The entire cohort had a 5-year OS rate of 80.4%, a DMFS rate of 80.5%, a PFS rate of 72.8%, and a LRRFS rate of 92.6%. The 7-year OS, DMFS, PFS, and LRRFS rates were 77.5, 78.8, 70.2, and 90.9%, respectively.

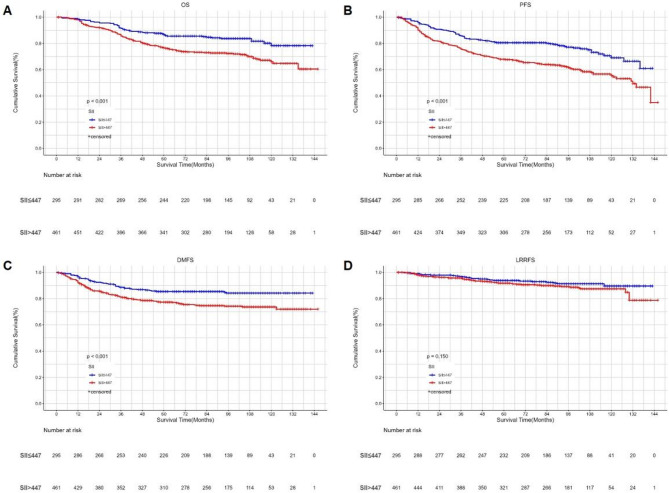

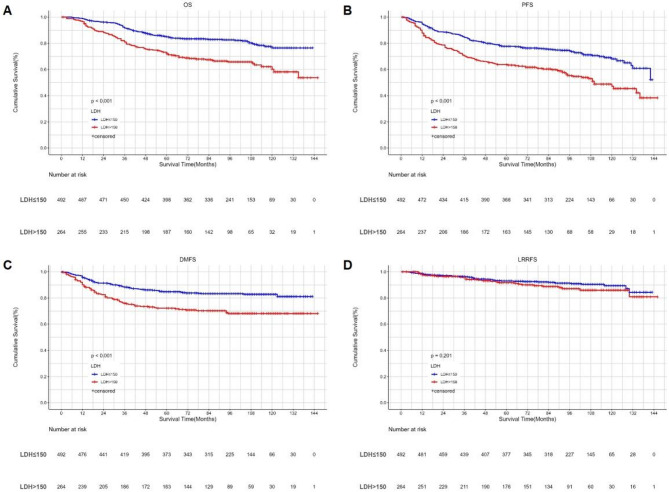

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that higher SII and LDH were significantly associated with shorter OS, DMFS, and PFS. However, they were not related to LRRFS. (Figures 1 and 2). The proportional hazards assumption for SII and LDH was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals. All P values exceeded 0.05, indicating that the proportional hazards assumption was not violated (Supplemental Digital Content, Figs. 1 and 2). Prognostic factors with significant results in univariate Cox analysis were included in the multivariate analysis (Table 2). The results showed that both SII and LDH were independent prognostic factors for OS (p < 0.001 vs. p = 0.005), DMFS (p < 0.001 vs. p = 0.001), and PFS (p < 0.001 vs. p = 0.001) in NPC patients, but neither was significantly related to LRRFS. Besides LDH and SII, age, T stage, and N stage were related to OS, DMFS, and PFS. The only independent prognostic factor for LRRFS was N stage.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan‒Meier survival curves of OS (A), PFS (B), DMFS (C) and LRRFS (D) between low and high SII groups according to the cut-of value. SII systemic immune-inflammation index, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, DMFS distant metastasis-free survival, LRRFS local-regional recurrence-free survival.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan‒Meier survival curves of OS (A), PFS (B), DMFS (C) and LRRFS (D) between low and high LDH groups according to the cut-of value. LDH serum lactate dehydrogenase, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, DMFS distant metastasis-free survival, LRRFS local–regional recurrence-free survival.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of clinicopathological parameters for 756 patients with nonmetastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma prognosis.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| OS | ||||

| Sex (Male/Female) | 0.823(0.585–1.157) | 0.262 | ||

| Age (≤ 45/ > 45) | 2.368(1.743–3.217) | < 0.001 | 2.526(1.853–3.443) | < 0.001 |

| Histologic type (I/II + III) | 2.259(0.316–16.134) | 0.416 | ||

| T classification (T1-2/T3-4) | 2.041(1.484–2.806) | < 0.001 | 1.957(1.235–3.101) | 0.004 |

| N classification (N0-1/N2-3 ) | 1.900(1.425–2.533) | < 0.001 | 1.849(1.310–2.610) | < 0.001 |

| TNM stage (I + II/III + IVa) | 2.541(1.689–3.821) | < 0.001 | 1.034(0.546–1.959) | 0.917 |

| Chemotherapy (No/Yes) | 1.392(0.968–2.004) | 0.074 | ||

| LDH (≤ 150/>150) | 2.093(1.570–2.791) | < 0.001 | 1.810(1.353–2.422) | < 0.001 |

| SII (≤ 447/ > 447) | 1.864(1.348–2.578) | < 0.001 | 1.605(1.155–2.231) | 0.005 |

| DMFS | ||||

| Sex (Male/Female) | 0.909(0.635–1.302) | 0.603 | ||

| Age (≤ 45/ > 45) | 1.495(1.090–2.050) | 0.013 | 1.897(1.473–2.444) | < 0.001 |

| Histologic type (I/II + III) | 1.788(0.250-12.776) | 0.562 | ||

| T classification (T1-2/T3-4) | 1.811(1.292–2.537) | 0.001 | 1.609(1.097–2.361) | 0.015 |

| N classification (N0-1/N2-3 ) | 2.196(1.607-3.000) | < 0.001 | 1.679(1.245–2.264) | 0.001 |

| TNM stage (I + II/III + IVa) | 2.322(1.514–3.559) | < 0.001 | 1.045(0.610–1.791) | 0.871 |

| Chemotherapy (No/Yes) | 1.904(1.233–2.941) | 0.004 | 1.168(0.821–1.662) | 0.388 |

| LDH (≤ 150/>150) | 2.010(1.471–2.746) | < 0.001 | 1.678(1.312–2.146) | < 0.001 |

| SII (≤ 447/ > 447) | 1.800(1.271–2.549) | 0.001 | 1.600(1.218–2.103) | 0.001 |

| PFS | ||||

| Sex (Male/Female) | 0.922(0.698–1.219) | 0.571 | ||

| Age (≤ 45/ > 45) | 1.803(1.406–2.311) | < 0.001 | 1.897(1.473–2.444) | < 0.001 |

| Histologic type (I/II + III) | 1.639(0.408–6.593) | 0.487 | ||

| T classification (T1-2/T3-4) | 1.781(1.374–2.308) | < 0.001 | 1.609(1.097–2.361) | 0.015 |

| N classification (N0-1/N2-3 ) | 1.820(1.428–2.320) | < 0.001 | 1.679(1.245–2.264) | 0.001 |

| TNM stage (≤ 150/>150) | 2.233(1.615–3.088) | < 0.001 | 1.045(0.610–1.791) | 0.871 |

| Chemotherapy (No/Yes) | 1.517(1.112–2.070) | 0.008 | 1.168(0.821–1.662) | 0.388 |

| LDH (≤ 150/>150) | 1.881(1.476–2.397) | < 0.001 | 1.678(1.312–2.146) | < 0.001 |

| SII (≤ 447/ > 447) | 1.830(1.399–2.395) | < 0.001 | 1.6000(1.218–2.103) | 0.001 |

| LRRFS | ||||

| Sex (Male/Female) | 1.274(0.770–2.108) | 0.346 | ||

| Age (≤ 45/ > 45) | 1.420(0.889–2.267) | 0.142 | ||

| Histologic type (I/II + III) | 0.884(0.123–6.369) | 0.902 | ||

| T classification (T1-2/T3-4) | 1.103(0.689–1.767) | 0.684 | ||

| N classification (N0-1/N2-3 ) | 2.559(1.603–4.085) | < 0.001 | 2.559(1.603–4.085) | < 0.001 |

| TNM stage (I + II/III + IVa) | 1.791(0.998–3.215) | 0.051 | ||

| Chemotherapy (No/Yes) | 1.386(0.772–2.488) | 0.274 | ||

| LDH(≤ 150/>150) | 1.363(0.846–2.194) | 0.203 | ||

| SII (≤ 447/ > 447) | 1.437(0.874–2.363) | 0.153 | ||

SII systemic immune-inflammation index, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, DMFS distant metastasis-free survival, LRRFS local-regional recurrence-free survival, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval.

Subgroup analysis stratified by clinical stage

We conducted further analysis to evaluate the roles of SII and LDH in early (stage I/II) and advanced (stage III-IVa) NPC patients separately. In stage III-IVa NPC patients, multivariate analysis indicated both SII and LDH remained independent prognostic factors for OS (p = 0.003 vs. p < 0.001), DMFS (p = 0.006 vs. p = 0.002), and PFS (p = 0.002 vs. p < 0.001), but neither was significantly related to LRRFS (Table 3). However, in the early stages, patients with higher SII and LDH levels showed a trend towards shorter OS, DMFS, and PFS, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.326 vs. 0.677, p = 0.554 vs. 0.050, p = 0.051 vs. 0.425).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of clinicopathological parameters for 542 patients with advanced( stage III-IVa) nasopharyngeal carcinoma prognosis.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| OS | ||||

| Sex (Male/Female) | 0.732(0.497–1.079) | 0.115 | ||

| Age (≤ 45/ > 45) | 2.674(1.912–3.739) | < 0.001 | 2.616(1.864–3.670) | < 0.001 |

| Histologic type (I/II + III) | 1.921(0.269–13.734) | 0.515 | ||

| T classification (T1-2/T3-4) | 1.363(0.895–2.075) | 0.149 | ||

| N classification (N0-1/N2-3 ) | 1.453(1.062–1.988) | 0.020 | 1.446(1.053–1.986) | 0.023 |

| TNM stage (I + II/III + IVa) | ||||

| Chemotherapy (No/Yes) | 0.732(0.470–1.139) | 0.166 | ||

| LDH (≤ 150/>150) | 2.321(1.700–3.170) | < 0.001 | 1.944(1.417–2.666) | < 0.001 |

| SII (≤ 447/ > 447) | 1.767(1.231–2.536) | 0.002 | 1.732(1.204–2.491) | 0.003 |

| DMFS | ||||

| Sex(Male/Female) | 0.755(0.498–1.146) | 0.187 | ||

| Age(≤ 45/ > 45) | 1.631(1.155–2.305) | 0.006 | 1.607(1.133–2.279) | 0.008 |

| Histologic type (I/II + III) | 1.537(0.215–10.994) | 0.668 | ||

| T classification (T1-2/T3-4) | 1.193(0.767–1.857) | 0.433 | ||

| N classification (N0-1/N2-3 ) | 1.791(1.264–2.538) | 0.001 | 1.741(1.224–2.476) | 0.002 |

| TNM stage (I + II/III + IVa) | ||||

| Chemotherapy (No/Yes) | 1.191(0.672–2.111) | 0.550 | ||

| LDH (≤ 150/>150) | 1.992(1.417-2.800) | < 0.001 | 1.705(1.206–2.408) | 0.002 |

| SII (≤ 447/ > 447) | 1.784(1.204–2.645) | 0.004 | 1.749(1.178–2.595) | 0.006 |

| PFS | ||||

| Sex (Male/Female) | 0.797(0.579–1.099) | 0.166 | ||

| Age (≤ 45/ > 45) | 1.964(1.494–2.582) | < 0.001 | 1.907(1.446–2.514) | < 0.001 |

| Histologic type (I/II + III) | 1.342(0.333–5.403) | 0.679 | ||

| T classification (T1-2/T3-4) | 1.200(0.852–1.691) | 0.298 | ||

| N classification (N0-1/N2-3 ) | 1.439(1.102–1.878) | 0.007 | 1.391(1.062–1.822) | 0.017 |

| TNM stage (≤ 150/>150) | ||||

| Chemotherapy (No/Yes) | 0.862(0.579–1.282) | 0.463 | ||

| LDH (≤ 150/>150) | 2.057(1.577–2.682) | < 0.001 | 1.777(1.356–2.328) | < 0.001 |

| SII (≤ 447/ > 447) | 1.673(1.239–2.259) | 0.001 | 1.625(1.202–2.197) | 0.002 |

| LRRFS | ||||

| Sex(Male/Female) | 1.064(0.590–1.918) | 0.838 | ||

| Age(≤ 45/ > 45) | 1.560(0.923–2.636) | 0.096 | ||

| Histologic type (I/II + III) | 0.712(0.098–5.151) | 0.737 | ||

| T classification (T1-2/T3-4) | 0.656(0.368–1.171) | 0.154 | ||

| N classification (N0-1/N2-3 ) | 2.491(1.425–4.355) | 0.001 | 2.491(1.425–4.355) | 0.001 |

| TNM stage (I + II/III + IVa) | ||||

| Chemotherapy (No/Yes) | 0.885(0.401–1.952) | 0.761 | ||

| LDH(≤ 150/>150) | 1.540(0.910–2.608) | 0.108 | ||

| SII (≤ 447/ > 447) | 1.142(0.658–1.981) | 0.637 | ||

SII systemic immune-inflammation index, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, DMFS distant metastasis-free survival, LRRFS local-regional recurrence-free survival, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval.

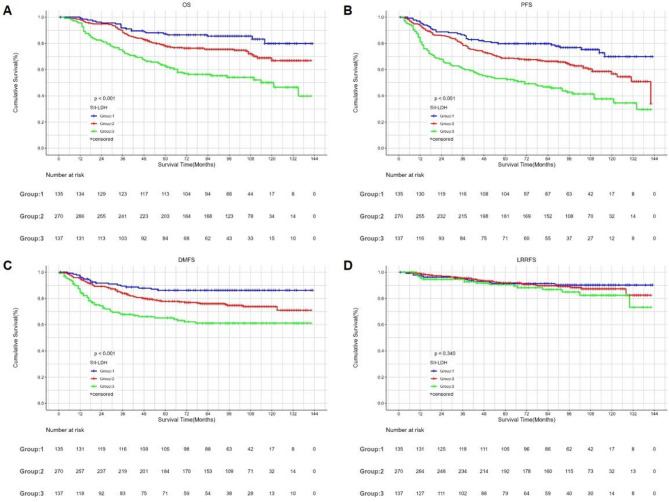

Combined prognostic value of PNI and LDH in Stage III-IVa patients

Stage III–IVa NPC patients were further stratified into three groups based on SII and LDH levels: Group 1 (high SII and high LDH), Group 2 (either high SII with low LDH or low SII with high LDH), and Group 3 (low SII and low LDH). There were significant differences among the three groups in OS (p < 0.001), DMFS (p < 0.001), and PFS (p < 0.001). However, the differences in LRRFS were not statistically significant. The 5-year OS, DMFS, and PFS rates for Groups 1, 2, and 3 were 87.2%, 77.9%, and 62.6%; 86.2%, 77.8%, and 65.2%; and 79.8%, 68.8%, and 53.2%, respectively (Fig. 3). When comparing the AUCs of SII, LDH, SII-LDH, age, and N stage, the AUC values of SII-LDH for OS, DMFS and PFS were higher than those of the other indices, at 0.645, 0.614, and 0.635, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan‒Meier survival curves of OS (A), PFS (B), DMFS (C) and LRRFS (D) between the SII-LDH groups according to the different levels of SII and LDH for patients with stage III–IVa. SII systemic immune-inflammation index, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, DMFS distant metastasis-free survival, LRRFS local–regional recurrence-free survival.

Fig. 4.

Predictive ability of SII, LDH, SII-LDH, N category and age for OS (A), PFS (B), and DMFS (C) by ROC curve analysis for patients with stage III–IVa. SII systemic immune-inflammation index, LDH lactated dehydrogenase, ROC receiver operating characteristic, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, DMFS distant metastasis-free survival.

Discussion

With the advancement of comprehensive management of NPC, the survival time and quality of life for NPC patients have significantly improved. However, approximately 70% of NPC patients are diagnosed at a locally advanced stage, and the rates of local recurrence and distant metastasis in this group remain high. Once metastasis occurs, the median survival time is significantly reduced. Currently, the prognosis and treatment decisions for NPC are based on the TNM staging system, which is determined by tumor anatomical factors. Growing evidence suggests that incorporating non-anatomical factors into the TNM staging system may enhance its prognostic accuracy and help optimize treatment strategies. Therefore, it is crucial to identify other predictive biomarkers that can recognize and differentiate patients at high risk of metastasis.

We found that pre-treatment SII and LDH are important prognostic factors for non-metastatic NPC patients receiving IMRT. To our knowledge, this is the first study to jointly analyze the impact of SII and LDH on multiple prognostic outcomes in non-metastatic NPC patients treated with IMRT according to the 8th edition staging system. We found that pre-treatment SII and LDH were significantly associated with OS, DMFS, and PFS, but not with LRRFS. Further subgroup analysis showed that in patients with locally advanced (stage III-IVa) NPC, SII and LDH remained independent prognostic factors for OS, DMFS, and PFS, and the combined value of SII and LDH in predicting OS, DMFS, and PFS was higher than that of other single indicators. However, in the early stage (I/II), patients with higher SII and LDH levels showed a trend towards shorter OS, PFS, and DMFS, but this was not statistically significant.

Studies on the impact of SII on the prognosis of NPC can be traced back to 2017. Jiang et al. found that SII was an independent prognostic factor for OS in NPC, with prognostic value superior to PLR, NLR, and MLR24. However, this study was based on TNM-7 staging, while the eighth edition is now widely used. Moreover, most patients in the study received 2D radiotherapy, while IMRT is now the primary radiotherapy technique. Oei et al. conducted a retrospective study on 585 stage I-IV NPC patients and found that pre-treatment SII is an independent prognostic factor for OS, PFS, and DMFS. After propensity score matching(PSM), SII remained significantly associated with OS, PFS, and DMFS14. Xiong et al. found that in stage III-IVa locally advanced NPC patients, pre-treatment SII > 402.10 was significantly associated with poor OS and PFS13. We conducted a retrospective study of 756 NPC patients who received IMRT, re-staged all eligible patients according to the TNM-8 guidelines, and performed a longer follow-up with analysis of more endpoint events. We found that pre-treatment SII was significantly associated with OS (P < 0.001), DMFS (P = 0.001), and PFS (P < 0.001) among non-metastatic NPC patients. Subgroup analysis was also conducted, and the results were consistent among patients with locally advanced NPC. Additionally, our analysis confirmed that SII was not an independent factor associated with LRRFS. This is consistent with the only study that analyzed LRRFS25. However, Zeng et al. found that SII was not an independent prognostic factor for OS and DFS in NPC patients17. Their study was based on the 7th edition of the TNM staging system and included only 255 patients, resulting in a small sample size, which may have limited the stability and reliability of the conclusions. Furthermore, several studies have found that SII does not have significant predictive value for OS and PFS15. The reason for this result may be that it was a study conducted on EBV DNA-negative patients. EBV DNA-negative patients have a much lower incidence of distant metastasis compared to EBV DNA-positive patients, leading to poor performance of SII in predicting survival in these patients. Therefore, these study results may not be applicable to patients with plasma EBV DNA positivity. Notably, studies have shown that in regions with a high incidence of NPC, more than 90% of patients test positive for plasma EBV DNA3.

The prognostic value of SII can be attributed to the biological roles of its components. SII is a comprehensive inflammatory marker calculated from neutrophil, platelet, and lymphocyte counts, reflecting both systemic inflammation and the immune status of cancer patients5,7. Neutrophils promote tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis via various mechanisms, including the induction of DNA damage, promotion of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and immunosuppressive factors26,27. Platelets also contribute significantly to tumor development and metastasis by forming protective microaggregates that shield tumor cells from immune clearance, secreting growth factors such as VEGF and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) to enhance angiogenesis and EMT, and suppressing natural killer (NK) cell function, thereby facilitating tumor progression28. Moreover, platelets mediate tumor cell adhesion to endothelial surfaces via P-selectin, further promoting tumor cell extravasation and distant metastasis29. These mechanisms collectively suggest that increased neutrophil and platelet levels contribute to tumor aggressiveness. In contrast, lymphocytes, as a crucial component of the immune system, exert anti-tumor effects through immune surveillance and the secretion of cytokines30. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), a key immune population within the tumor microenvironment (TME), can induce tumor cell apoptosis through cytotoxic functions, antigen presentation, and cytokine release, thereby impeding tumor progression and metastasis31. A reduced lymphocyte count may impair the host’s ability to recognize and eliminate tumor cells. Therefore, an elevated SII may reflect more aggressive tumor biology. Additionally, Somay et al. reported that systemic inflammation plays a critical role in the development of radiotherapy-related complications. It suggests that SII has multidimensional predictive potential in NPC and may serve as a potential biomarker for evaluating its prognosis32.

LDH is a key glycolytic enzyme that mediates the conversion of pyruvate to lactate and serves as a biomarker of tumor hypoxia33,34. In addition, as a pivotal metabolic regulator in the TME, elevated LDH activity leads to pathological accumulation of lactate. The resulting acidic microenvironment inhibits the activity of effector T cells and NK cells, while enhancing the immunosuppressive function of regulatory T cells (Tregs)35. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that LDHA maintains tumor cell stemness by promoting lactate metabolism and also plays a pivotal role in regulating resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, thereby facilitating tumor progression and recurrence36. Thus, elevated LDH levels are associated with hypoxic stress, immune dysfunction, therapeutic resistance, and tumor progression.

A large-scale study showed that elevated pre-treatment LDH levels are associated with poor OS and PFS18. Oei et al. conducted a retrospective study of 427 non-metastatic NPC patients and found that elevated pre-treatment LDH levels can serve as an independent predictor for OS and PFS, as well as for DMFS. This conclusion remained consistent even after PSM37. Jiang et al. developed a prognostic nomogram for patients with locally advanced NPC and showed that elevated LDH levels are associated with poorer OS38. This is consistent with our findings. However, the above two articles were based on the 7th edition staging. In our study, all patients were re-staged according to the 8th edition of the TNM system, and multiple survival endpoints were assessed. The results showed that pre-treatment LDH levels were independent prognostic factors for OS (P = 0.000), DMFS (P < 0.001), and PFS (P = 0.021), but not for LRRFS. Further subgroup analyses in patients with locally advanced NPC yielded consistent results. For early-stage NPC, even though the statistical tests were not significant, patients with lower LDH levels showed a trend towards longer OS, DMFS, and PFS. These results confirm that pre-treatment serum LDH can serve as a reliable prognostic factor for NPC patients. In the era of IMRT, the local-regional control rate of NPC is very high. All patients in our study received IMRT treatment, which might be one of the most important reasons why LDH has no significant impact on LRRFS. Additionally, patients with early clinical stage NPC generally have longer progression-free survival, and the number of cases with metastasis or death is relatively low at this stage. In our cohort, by the end of follow-up, only 44 out of 214 early-stage NPC patients had experienced disease progression, 27 had died, and 25 had developed metastasis. The small number of events might be the reason for the non-significant association in the early stage.

We further analyzed the combined prognostic value of SII and LDH in locally advanced NPC. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the combined prognostic value of these two factors in locally advanced NPC. Patients were stratified into three groups according to their SII and LDH levels. Patients with both low SII and LDH levels had better OS, DMFS and PFS. Furthermore, the AUCs of the combined SII–LDH index were higher than those of any individual indicator. This suggests that the combination of these two parameters is a powerful independent prognostic factor for patients with locally advanced NPC, and it is superior to any single indicator. This synergistic effect may arise from the integration of systemic immune-inflammatory status and tumor metabolic activity, helping to capture the tumor’s invasive characteristics more comprehensively across multiple dimensions, thereby enhancing the predictive ability for disease progression and outcomes. Luo et al. recently proposed an innovative perspective by conceptualizing NPC as an ecological disease, emphasizing the dynamic interactions between the tumor and the host microenvironment39. Within this framework, the SII and LDH levels investigated in our study may represent key ecological stressors that disrupt the tumor-host equilibrium, thereby promoting disease progression and influencing clinical outcomes.

In this study, age was identified as an independent prognostic factor for OS, PFS, and DMFS in patients with non-metastatic NPC, consistent with findings from several previous studies40,41. This association may be explained by age-related physiological decline, immunosenescence, and a higher burden of comorbidities in elderly patients41,42. In addition, elderly patients are more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage (III–IV) due to delayed recognition of early symptoms, which may further contribute to poor prognosis43. From a treatment perspective, elderly NPC patients tend to exhibit reduced tolerance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, along with a higher incidence of treatment-related complications, both of which may adversely affect treatment efficacy and survival outcomes44,45. Collectively, these clinical characteristics may compromise treatment efficacy and adversely affect survival outcomes in this patient population.

There are several limitations in our study. First, this is a retrospective study from a single center, which may lead to selection bias. Second, we only analyzed the impact of pre-treatment SII and LDH on the prognosis of non-metastatic NPC. Analyzing their dynamic changes might be more meaningful for prognosis. Third, prior to 2010, plasma EBV DNA was not routinely monitored at Fujian Provincial Cancer Hospital, so we were unable to assess EBV DNA data. Therefore, further multicenter, prospective studies incorporating SII and dynamic changes in LDH are needed to validate their predictive value in non-metastatic NPC patients.

In conclusion, our study shows that non-metastatic NPC patients with elevated pre-treatment SII and LDH have significantly poorer treatment outcomes. This association is particularly pronounced in patients with locally advanced disease. Furthermore, the combination of these two factors predicts the prognosis of locally advanced NPC patients more accurately than using SII or LDH alone. SII and LDH are cost-effective, stable biomarkers that are routinely measured in clinical practice. Assessing pre-treatment SII and LDH and combining them with the TNM staging system can help clinicians better individualize treatment, evaluate efficacy, and predict prognosis for NPC.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

C.X.Z.: Conceptualization and writing-original draft. Z.W.Z.: Study design and writing-original draft. Y.P.Z.: Data acquisition and Data analysis.B.J.C.: Manuscript revision, formal analysis.All authors have reviewed and given their approval for the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was sponsored by National Clinical Key Specialty Construction Program and Key Clinical Specialty Discipline Construction Program of Fujian, China. This study was supported by grants from the National Clinical Key Specialty Construction Program; Fujian Provincial Clinical Research Center for Cancer Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy (Grant Number: 2020Y2012). This research was also supported by grant from the Fujian Cancer Hospital Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Diagnosis and Treatment Center.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chunxia Zhang and Zhouwei Zhan contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin.71, 209–249 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Co, J., Mejia, M. B. & Dizon, J. M. Evidence on effectiveness of intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus 2-dimensional radiotherapy in the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Meta-analysis and a systematic review of the literature. Head Neck. 38 (Suppl 1), E2130–2142 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, Y. P. et al. Nasopharyng. Carcinoma Lancet394, 64–80 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt, A. & Weber, O. F. In memoriam of Rudolf virchow: a historical retrospective including aspects of inflammation, infection and neoplasia. Contrib. Microbiol.13, 1–15 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kou, J., Huang, J., Li, J., Wu, Z. & Ni, L. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis and responsiveness to immunotherapy in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta–analysis. Clin. Exp. Med.23, 3895–3905 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang, D. et al. Combined pretreatment neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival and prognosis in patients with non-metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a retrospective study. Sci. Rep.14, 9898 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu, B. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res.20, 6212–6222 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou, Y., Dai, M. & Zhang, Z. Prognostic significance of the systemic Immune-Inflammation index (SII) in patients with small cell lung cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol.12, 814727 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou, Y. et al. Predictive significance of systemic Immune-Inflammation index in patients with breast cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Onco Targets Ther.16, 939–960 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng, L., Yang, Y., Hu, X., Zhang, R. & Li, X. Prognostic value of the pretreatment systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Transl Med.21, 79 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng, J. et al. Preoperative systemic immune-inflammation index as a prognostic indicator for patients with urothelial carcinoma. Front. Immunol.14, 1275033 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao, J. et al. Predictive value of immunotherapy-induced inflammation indexes: dynamic changes in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Ann. Med.55, 2280002 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiong, Y. et al. Prognostic efficacy of the combination of the pretreatment systemic Immune-Inflammation index and Epstein-Barr virus DNA status in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. J. Cancer. 12, 2275–2284 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oei, R. W. et al. Prognostic value of inflammation-based prognostic index in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a propensity score matching study. Cancer Manag Res.10, 2785–2797 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan, X. et al. Prognostic value of systemic inflammation response index in nasopharyngeal carcinoma with negative Epstein-Barr virus DNA. BMC Cancer. 22, 858 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, Q., Yu, L., Yang, P. & Hu, Q. Prognostic value of inflammatory markers in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients in the Intensity-Modulated radiotherapy era. Cancer Manag Res.13, 6799–6810 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeng, X., Liu, G., Pan, Y. & Li, Y. Development and validation of immune inflammation-based index for predicting the clinical outcome in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Cell. Mol. Med.24, 8326–8349 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding, C. et al. Evaluation of a novel model incorporating serological indicators into the conventional TNM staging system for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol.151, 106725 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang, A. et al. Dynamic serum biomarkers to predict the efficacy of PD-1 in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Cell. Int.21, 518 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen, Z. et al. Pretreatment serum lactate dehydrogenase level as an independent prognostic factor of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the Intensity-Modulated radiation therapy era. Med. Sci. Monit.23, 437–445 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou, G. Q. et al. Prognostic implications of dynamic serum lactate dehydrogenase assessments in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Sci. Rep.6, 22326 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin, S. et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with reduced-volume intensity-modulated radiation therapy: report on the 3-year outcome of a prospective series. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.75, 1071–1078 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camp, R. L., Dolled-Filhart, M. & Rimm, D. L. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin. Cancer Res.10, 7252–7259 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang, W. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts the clinical outcome in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a propensity score-matched analysis. Oncotarget8, 66075–66086 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiong, Y., Shi, L., Zhu, L. & Peng, G. Comparison of TPF and TP induction chemotherapy for locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma based on TNM stage and pretreatment systemic Immune-Inflammation index. Front. Oncol.11, 731543 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koenderman, L. & Vrisekoop, N. Neutrophils in cancer: from biology to therapy. Cell. Mol. Immunol.22, 4–23 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang, S., Shi, J., Shen, J. & Fan, X. Metabolic reprogramming of neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment: emerging therapeutic targets. Cancer Lett.612, 217466 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, S. et al. The dynamic role of platelets in cancer progression and their therapeutic implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 24, 72–87 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlesinger, M. Role of platelets and platelet receptors in cancer metastasis. J. Hematol. Oncol.11, 125 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ménétrier-Caux, C., Ray-Coquard, I., Blay, J. Y. & Caux, C. Lymphopenia in cancer patients and its effects on response to immunotherapy: an opportunity for combination with cytokines?? J. Immunother Cancer. 7, 85 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraja, F. P. et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: from chemotactic recruitment to translational modeling. Front. Immunol.16, 1601773 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Somay., E. SELEK., U. Systemic inflammation score for predicting Radiation-Induced trismus and osteoradionecrosis of the jaw rates in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. UHOD: Int. J. Hematol. Oncol.33, 158–169 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pérez-Tomás, R. & Pérez-Guillén, I. Lactate in the tumor microenvironment: an essential molecule in cancer progression and treatment. Cancers (Basel) 12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Muz, B., de la Puente, P., Azab, F. & Azab, A. K. The role of hypoxia in cancer progression, angiogenesis, metastasis, and resistance to therapy. Hypoxia (Auckl). 3, 83–92 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen, J. et al. Lactate and lactylation in cancer. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther.10, 38 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Claps, G. et al. The multiple roles of LDH in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol.19, 749–762 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oei, R. W. et al. Pre-treatment serum lactate dehydrogenase is predictive of survival in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma undergoing Intensity-Modulated radiotherapy. J. Cancer. 9, 54–63 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang, Y., Qu, S., Pan, X., Huang, S. & Zhu, X. Prognostic nomogram for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Sci. Rep.10, 861 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo, W. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma ecology theory: cancer as multidimensional Spatiotemporal unity of ecology and evolution pathological ecosystem. Theranostics13, 1607–1631 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, W. M., Mo, Q. Y. & Zhu, X. D. Contribution of age at diagnosis to cancer-specific survival of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients receiving radiotherapy. Med. (Baltim).102, e34816 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zuo, Z. et al. Machine learning-derived prognostic signature for progression-free survival in non-metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 47, 112–128 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu, S. G. et al. Demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and survival outcomes according to age at diagnosis: A population-based analysis. Oral Oncol.73, 83–87 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin, Y. N. et al. The characteristics and survival outcomes in patients aged 70 years and older with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the Intensity-Modulated radiotherapy era. Cancer Res. Treat.51, 34–42 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lian, C. L. et al. Risk factors of early thyroid dysfunction after definitive radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Head Neck. 45, 2344–2354 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He, Y. Q. et al. A comprehensive predictive model for radiation-induced brain injury in risk stratification and personalized radiotherapy of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol.190, 109974 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.