ABSTRACT

Salamanders have large and complex genomes, hampering whole genome sequencing. However, reduced representation sequencing provides a feasible alternative to obtain genome‐wide data. We present NewtCap: a sequence capture bait set that targets c. 7 k coding regions across the genomes of all true salamanders and newts (the family Salamandridae, also known as “salamandrids”). We test the efficacy of NewtCap, originally designed for the Eurasian Triturus newts, in 30 species, belonging to 17 different genera that cover all main Salamandridae lineages. We also test NewtCap in two other salamander families. We discover that NewtCap performs well across all Salamandridae lineages (but not in the salamander families Ambystomatidae and Hynobiidae). As expected, the amount of genetic divergence from the genus Triturus correlates negatively to capture efficacy and mapping success. However, this does not impede our downstream analyses. We showcase the potential of NewtCap in the contexts of; (1) phylogenomics, by reconstructing the phylogeny of Salamandridae, (2) phylogeography, by sequencing the four closely related species comprising the genus Taricha, (3) hybrid zone analysis, by genotyping two Lissotriton species and different classes of interspecific hybrids, and (4) conservation genetics, by comparing Triturus ivanbureschi samples from several wild populations and one captive‐bred population. Overall, NewtCap has the potential to boost straightforward, reproducible, and affordable genomic studies, tackling both fundamental and applied research questions across salamandrids.

Keywords: Caudata, exon capture, high throughput sequencing, hyb‐seq, target enrichment, Urodela

1. Introduction

One of the most challenging groups of animals to study genomically is the salamanders. These organisms have complex and large genomes that contain many repetitive elements compared to most other animals (e.g., they can be in the range of 10 to 40 times the size of a human genome; Gregory 2002; Litvinchuk et al. 2007; Sessions 2008; Sun et al. 2012; Gregory 2024; Smith et al. 2019). This is the primary reason that conducting whole genome sequencing and de novo genome assembly for salamanders is extremely costly in terms of money, time, and computational resources (Lou et al. 2021; Calboli et al. 2011).

Fortunately, reduced representation sequencing strategies are paving the way toward more straightforward, reproducible, and affordable genomic studies, especially in organisms with large and complex genomes (Good 2011; Zaharias et al. 2020). By focusing sequencing efforts on subsets of the genome, rather than the entire genome, valuable time and resources can be conserved, allowing for a greater number of samples to be processed (Andermann et al. 2019). Different types of genome‐subsampling techniques exist, broadly categorized as “non‐targeted” versus “targeted,” and their suitability varies, depending on the study species and research objectives (Da Fonseca et al. 2016; Lemmon and Lemmon 2013; Jones and Good 2016).

Non‐targeted approaches, such as Restriction site‐Associated DNA sequencing (RAD‐seq) and related techniques, are widely used in genetic mapping and population studies, including salamander studies (e.g., Hu et al. 2019; Rancilhac et al. 2019; Hubbs et al. 2022; Andrews et al. 2016; France, Babik, et al. 2025; Babik et al. 2024; Rodríguez et al. 2017; Burgon et al. 2021; Scott et al. 2024). While simple, scalable (Andermann et al. 2019), and having the key advantage of not needing to know the sequences of any loci beforehand, such non‐targeted approaches are known to yield missing data, underestimate genetic diversity, and call incorrect allele frequencies (Arnold et al. 2013; Rubin et al. 2012; Davey et al. 2013). This is due to restriction site polymorphisms that limit the phylogenetic signal for resolving deep evolutionary relationships (Dodsworth et al. 2019; Rubin et al. 2012; Lowry et al. 2017).

On the other hand, targeted methods such as target capture sequencing offer a strategy to achieve higher resolution and specificity, as they focus on pre‐selected (orthologous) loci (Mamanova et al. 2010; Harvey et al. 2016). With target capture sequencing, biotinylated RNA probes—or “baits”—that are complementary to the loci of interest are used, causing them to bind to the “target” regions, before streptavidin‐coated magnetic beads are used to “capture” them (Gnirke et al. 2009; Albert et al. 2007). The main advantage of using the target capture method over untargeted methods is that there will be higher efficiency, because enrichment of specific (usually coding) genomic regions of interest is more effectively achieved across samples (Grover et al. 2012; Andermann et al. 2019; Heyduk et al. 2016; Fitzpatrick et al. 2024). Furthermore, the flanking regions of targets can also provide information on more variable genomic regions such as introns (Jones and Good 2016; Zhou and Holliday 2012), and off‐target “bycatch” reads can provide additional data as well (Featherstone and McGaughran 2024; Guo et al. 2012).

Often, custom target capture baits are designed, which can be based on a draft genome or transcriptome reference; however, pre‐designed baits can be ordered as well (Bi et al. 2012; Andermann et al. 2019; Jimenez‐Mena et al. 2022). Over the last decade, many target capture bait sets have been tested and made publicly available for different types of organisms, ranging from micro‐organisms to macro‐organisms (e.g., Andermann et al. 2019; Grover et al. 2012; Heyduk et al. 2016; Khan et al. 2024; Quek and Ng 2024; Yu et al. 2023). For animals in particular, bait sets exist for certain groups of insects (e.g., Hymenoptera; Faircloth et al. 2015), snails (e.g., Eupulmonata; Teasdale et al. 2016), reptiles (e.g., Squamata; Schott et al. 2017; Singhal et al. 2017), fish (e.g., Acanthomorpha; Alfaro et al. 2018), and amphibians (e.g., Anura; Hutter et al. 2022). Salamander bait sets have also already been designed for particular genera (Ambystoma and Triturus; McCartney‐Melstad et al. 2016; Wielstra et al. 2019). As the target capture approach generally handles a certain degree of sequence divergence well, a bait set designed for one genus has great potential to work in other genera too (Bragg et al. 2016; Portik et al. 2016). Thus, it is worth exploring the potential transferability of such existing bait sets to related taxa.

We introduce “NewtCap:” a target capture bait set and protocol for salamanders of the family Salamandridae (which includes the “true salamanders” and the “newts”). The bait set, originally designed for Triturus newts (Wielstra et al. 2019), targets c. 7 k putative, orthologous, coding regions. Here, we provide an updated version of the lab protocol that cuts down on costs, time and DNA input. Furthermore, we investigate the efficacy of NewtCap across 30 different species and 17 genera of the Salamandridae family and test its efficiency in two distantly related species of other salamander families. Besides checking general performance, we assess the usefulness of NewtCap in the contexts of; (1) phylogenomics, by inferring a Salamandridae phylogeny, (2) phylogeography, by investigating the relationships among multiple individuals of four closely related Taricha species, (3) hybrid zone analysis, by calculating the hybrid index and heterozygosity for two Lissotriton species and interspecific hybrids of different cross types, and (4) conservation genetics, by determining the genetic relatedness of a captive‐bred Triturus ivanbureschi population to wild populations. Overall, we demonstrate that NewtCap is an important tool for molecular studies on salamandrids.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and DNA Extraction

We studied 73 individual salamanders in total, covering 30 species and 17 genera of the Salamandridae family (including nine interspecific hybrids of the genus Lissotriton), as well as two more distantly related samples (Table S1) from the families Ambystomatidae and Hynobiidae (Marjanović and Laurin 2013; Frost 1985). We obtained DNA extractions or genetic data from previous studies (Wielstra et al. 2019; De Visser et al. 2024; Kazilas et al. 2024; Mars et al. 2025; Kalaentzis et al. 2025; Robbemont et al. 2023; Pasmans et al. 2006; Valbuena‐Urena et al. 2013; Sequeira et al. 2022; France, De Visser, et al. 2024), as well as new samples for this study (provided by collaborators, see acknowledgments and Table S1).

We used the Promega Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), which is a salt‐based DNA extraction protocol (Sambrook and Russell 2001). The DNA from each sample was resuspended in 100 μL 1 × TE buffer before concentrations and purity were assessed via spectrophotometry, using the DropSense96 (Trinean, Gentbrugge, Belgium). As we used a minimum concentration of 150 ng/μL for library preparation, any sample found to be below was concentrated by vacuum centrifugation.

2.1.1. NewtCap: Laboratory Procedures

The target capture procedures are fully documented and included as Supporting Information (see under “Data Accessibility”). These protocols are rigorously optimized versions of those previously described (see Wielstra et al. 2019). Sonication of genomic DNA has been replaced with enzymatic fragmentation, resulting in a tenfold increase in library yield per ng of input DNA, in addition to time and cost savings. The volumes of all reagents in the library preparation were reduced by 75% compared to the manufacturers protocol to conserve reagents. Target capture protocols have been adapted from Mybaits V3.0 to the V4.0 kit and are fully compatible with Mybaits V5.0.

2.2. Library Preparation

DNA libraries were constructed using the NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol, with quarter volumes of all reagents and with the following modifications: 1,000 ng of extracted genomic DNA was used as input (6.5 μL at 154 ng/μL). The enzymatic shearing time at 37°C was adjusted to 6.5 min (as the minimum time of 15 min suggested by the manufacturer resulted in over‐digestion). After NEB adapter ligation and cleavage with the NEB USER enzyme, NucleoMag magnetic separation beads (Macherey‐Nagel, Düren, Germany) were used for double‐ended size selection targeting an insert size of 300 bp. Libraries were indexed with 8 cycles of PCR amplification, using unique combinations of custom i5 and i7 index primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Leuven, Belgium). NucleoMag beads were used again for a final cleanup before the libraries were resuspended in 22 μL of 0.1 × TE buffer. Library size distribution and concentration were measured using the Agilent 4150 TapeStation or 5200 Fragment analyzer system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), using the D5000 ScreenTape or DNF‐910 dsDNA Reagent Kit. We aimed for obtaining a final library concentration of at least 12 ng/μL.

2.3. Target Capture, Enrichment, and Sequencing

Libraries were equimolarly pooled in batches of 16, aiming for a total DNA mass of 4,000 ng (250 ng per sample). Vacuum centrifugation was then used to reduce the volume of each pool to 7.2 μL (556 ng/μL). We performed target capture with the MyBaits v4.0 kit (Arbor Biosciences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) previously designed for Triturus newts (Wielstra et al. 2019), which targets 7139 unique exonic regions (product Ref: # 170210–32). The manufacturer's protocol was employed with the following deviations: Blocks C and O were replaced with 5 μL of Triturus derived C0t‐1 DNA at 6,000 ng/μL (30,000 ng per pool). C0t‐1 DNA is enriched in repetitive sequences and acts as a blocking buffer to non‐specific targets in capture assays by hybridizing with repetitive sequences in the libraries (McCartney‐Melstad et al. 2016). Tissue to produce C0t‐1 DNA was derived from an invasive population of T. carnifex (Meilink et al. 2015).

The pooled libraries were incubated with the blocking buffer for 30 min, followed by hybridization for 30 h at 62°C. After capture of the hybridized baits with streptavidin‐coated beads and four cycles of washing, each pool was divided into equal‐volume halves. The first half was subject to 14 cycles of PCR amplification, followed by bead cleanup and resuspension in 22 μL of 0.1 × TE buffer. The concentration and fragment size distribution of the enriched pool were then measured with the TapeStation system, using the HS D5000 ScreenTape kit. If the final concentration was between 5 and 20 nM, then the same protocol was employed for the second half of the pool. If not, the number of post‐enrichment PCR cycles was altered to compensate. For each pool, 16 GB (1 GB per sample) of 150 bp paired‐end sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) by BaseClear B.V. (Leiden, the Netherlands).

2.3.1. Bioinformatics for Data Pre‐Processing

We followed a standard pipeline for cleaning up the raw reads and mapping the trimmed sequence data against reference sequences in a Linux environment (adapted from Wielstra et al. 2019). We describe the main steps and provide the scripts we used publicly through GitHub: https://github.com/Wielstra‐Lab/NewtCap_bioinformatics.

2.4. Quality Control and Read Clean‐Up

First, we clipped all reads to a maximum length of 150 bp using the BBDuk script by BBTools (BBMap ‐ Bushnell B. – https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/). Then we removed any leftover adapter contamination and low‐quality bases (or reads) using Trimmomatic v.0.38 (Bolger et al. 2014). Adapter sequences for the TruSeq2 multiplexed libraries were identified and removed. Leading and trailing bases were trimmed if the Phred score was < 5. We also removed reads in case the average Phred score in a sliding window (5′ to 3′) of a size of five base pairs dropped below 20, and we discarded all reads shorter than 50 bp. We monitored the quality of our sequences before and after trimming with FastQC (Andrews 2010) by using the summarizing “quality_check” function of SECAPR (Andermann et al. 2018).

2.5. Read Mapping and Variant Calling

Cleaned reads were mapped to the set of 7139 T. dobrogicus reference sequences with a maximum length of 450 bp (based on T. dobrogicus transcripts, see Wielstra et al. 2019) that were initially used for probe development. The reference FASTA file is provided as Supporting Information. Mapping was performed using the MEM algorithm from Burrows‐Wheeler Aligner v.0.7.17 (Li 2013), and we stored results in BAM format using SAMtools v.1.18 (Li et al. 2009; Danecek et al. 2021). We added read group information using the AddOrReplaceReadGroups function of Picard v.2.25.1, and PCR duplicates were flagged with Picard's MarkDuplicates (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). After doing so, the output was again saved in BAM format.

Next, we called variants using the HaplotypeCaller function of GATK v.4.1.3.0 (Auwera and O'connor 2020) including the ‐ERC GVCF option, and we used GATK's CombineGVCFs and GenotypeGVCFs functions to perform joint genotype calling to create multi‐sample (ms) gVCF files as input for downstream analyses. In case samples still needed to be added or removed from msgVCF files after joint genotyping, we did so using the view function of BCFtools v.1.15.1 (Danecek et al. 2021; Li 2011).

2.6. Downstream Analyses

2.6.1. Bait Performance Statistics

To evaluate the overall performance of the NewtCap baits, we calculated several statistics (Table S1). First, we counted the number of GB and reads contained in the raw FASTQ files for each sample. We also used the SAMtools' flagstat function to determine the total number of reads present in the (deduplicated) BAM files that passed quality control, as well as the percentage of these reads that successfully mapped to a reference sequence. We used SAMtools' coverage function to extract information on the mean depth of coverage, as well as the mean percentage of coverage for each target, and then averaged these per sample to provide an estimate of the “success rate.” Besides analyzing the contents of the BAM files, we checked how many sites were outputted in total in each separate, raw gVCF file by counting lines (as each non‐header line is one site). Then, we counted how many of those were considered SNPs and how many were considered INDELs by using the stats function of BCFtools (note that this is done before merging any files or applying any SNP filtering).

To estimate how the performance of NewtCap correlates with the level of genetic divergence from T. dobrogicus , the species that was used for bait design and as a reference for read mapping, we performed several statistical analyses. For these, we used a rough estimate of divergence times for lineages of Salamandridae (from De Visser et al. 2024). We explored the relationship between this estimated genetic divergence from T. dobrogicus and the following performance variables: (1) the percentage of mapped reads, (2) the percentage of reads marked as PCR duplicates, (3) the mean read depth number after deduplication, (4) the mean coverage of the sequence bases after deduplication, (5) the number of SNPs found in the raw gVCFs files, and (6) the number of INDELs found in the gVCF files. We calculated the correlation coefficients (r) between either of these variables and the estimated genetic divergence from T. dobrogicus . Depending on whether our data met the assumptions for parametric or non‐parametric testing, we either employed the Pearson correlation method or the Spearman's rank correlation method. We determined the level of significance using a two‐tailed test, with the p value threshold of p < 0.00833 to indicate statistical significance (implementing a Bonferroni correction on the usual threshold p < 0.05 for the six tests performed, as 0.05/8 = 0.00833). These analyses, including assumption checks such as testing for normality, were performed in Microsoft Excel 2024 (https://office.microsoft.com/excel).

2.6.2. Concatenated Phylogenetic Analyses in RAxML

To investigate the usefulness of NewtCap in the context of phylogenomics, we built phylogenetic trees with a Maximum Likelihood method using RAxML. We used NewtCap to reconstruct an existing Salamandridae tree that was originally built based on 5455 nuclear genes derived from transcriptome data (Rancilhac et al. 2021), by including 23 samples that cover at least one representative genus for each of the main clades in sensu (as described in Rancilhac et al. 2021). To further check the performance of NewtCap across true salamanders as well as for non‐salamandrid species, and to explore the position of the root, we added three additional samples in a second, extended analysis, namely the Salamandridae species Mertensiella caucasica (family Salamandridae) and two non‐salamandrid species Ambystoma mexicanum (family Ambystomatidae) and Paradactylodon gorganensis (family Hynobiidae). The raw msgVCF files for these two analyses, respectively, comprised 812,574 sites and 812,603 sites from across 7135 targets. Note that not all sites in the raw and intermediate gVCF and msgVCF files were necessarily polymorphic (i.e., invariant—or monomorphic—sites may still have been included, unless we specifically stated that these have been removed).

We applied quality filtering on the msgVCFs (which contained only the samples chosen for these phylogenetic analyses). First, we removed sites that showed heterozygote excess (p < 0.05) using BCFtools v.1.15.1, in order to rid paralogous targets (see Wielstra et al. 2019). Then, we used VCFtools v.0.1.16 to enforce the following strict filtering options: discarding INDELs (“‐‐remove‐indels”), filtering out sites with, for instance, poor genotype and mapping quality scores (“QD < 2”, “MQ < 40”, “FS > 60”, “MQRankSum < −12.5”, “ReadPosRankSum < −8”, and “QUAL < 30”; Poplin et al. 2017), and discarding sites with over 50% missing data (“‐‐max‐missing = 0.5”). At this stage, the intermediate msgVCF files contained, in total, 625,182 SNPs from across 7103 targets and 621,754 SNPs from across 7095 targets for the sets of 23 and 26 samples.

We converted the files into PHYLIP format with the “vcf2phylip.py” script (Ortiz 2019), which, by default, requires a minimum of four samples representing each SNP variant. Next, we performed an ascertainment bias correction by using the “ascbias.py” script (https://github.com/btmartin721/raxml_ascbias) to remove sites considered invariable by RAxML. The final PHYLIP file was used as input for RAxML v.8.2.12 (Stamatakis 2014), which we ran with 100 rapid bootstrap replicates, under the ASC_GTRGAMMA model, and with the Lewis ascertainment correction (Lewis 2001). We obtained the best‐scoring Maximum Likelihood tree out of the concatenation analyses.

To gain insights into the potential of NewtCap in a phylogeographical context, we also built a phylogenetic tree for the New World newt genus Taricha using RAxML. As input, we used a msgVCF file containing nine samples: eight Taricha samples covering four distinct species within the genus ( T. granulosa , T. rivularis , T. sierrae , and T. torosa , with two samples per species) and one sample of the sister‐genus Notophthalmus as outgroup (Table S1). The raw msgVCF file comprised 209,072 sites from 7059 targets. Subsequently, we performed the filtering steps as described above: rusing BCFtools v.1.14.1 to remove heterozygote excess (p < 0.05), and using VCFtools v.0.1.16 to discard INDELs (“‐‐remove‐indels”), filter out sites with poor quality scores (“QD < 2”, “MQ < 40”, “FS > 60”, “MQRankSum < −12.5”, “ReadPosRankSum < −8”, and “QUAL < 30”), and discard sites with over 50% missing data (“‐‐max‐missing = 0.5”). This left the intermediate msgVCF file with 180,385 SNPs from across 7048 targets. We visualized all phylogenies using FigTree v.1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

2.6.3. Hybrid Analyses and Conservation Genetics

To assess the usefulness of NewtCap in the context of hybridization studies, we used the R packages “triangulaR” (Wiens and Colella 2024), “ggplot2” (Wickham 2011) and “vcfR” (Knaus and Grunwald 2017) to build triangle plots. We investigated the target capture data of in total 15 Lissotriton individuals; three of each parental species ( L. vulgaris and L. montandoni ), as well as hybrids bred and reared in the lab: three F1 hybrids, three F2 hybrids, and three backcrosses (F1 × L. vulgaris ). We assembled a raw msgVCF file containing only these samples, which initially had data on 807,389 sites across in total 7135 targets. From this we extracted high‐quality SNPs as described before (by removing heterozygote excess, discarding indels, and filtering out sites with poor quality scores), except here we tolerated no missing data at all (i.e., we set VCFtools' “‐‐max‐missing” option to 1.0, instead of 0.5). The filtered msgVCF contained 532,332 SNPs from 6866 targets in total and was used as input for triangulaR.

The triangulaR package uses SNPs from an input VCF file that are estimated to be species‐diagnostic based on the parent species under a certain allele frequency threshold between “0” and “1,” where “1” equals a fixed difference between parental population (Wiens and Colella 2024). Thus, the threshold of 1 is employed when searching for two consistent, diverged, homozygous states in the parental populations. SNPs that pass this filter can then be used to calculate the hybrid index and heterozygosity for the samples analyzed. Considering that our parent populations did not comprise the actual parents of the hybrids included in our study and were represented by just three samples each, this complicated distinguishing species‐diagnostic SNPs from SNPs that only appeared diagnostic by chance. Therefore, we only extracted SNPs that were 100% species‐diagnostic (based on the information from the parental populations, by setting the allele frequency threshold to 1) and that were always heterozygous in the F1's. This extra functionality (i.e., filtering for heterozygosity in F1 hybrids) is currently not built into triangulaR, but we added this filtering option before conducting our calculations. We provide the customized R script in our GitHub repository.

To assess the performance of NewtCap in the context of a conservation genetic study we conducted a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Clustering Analysis (HCA) to determine the geographical origin of a captive‐bred population, which is presumed to originate from Cerkezköy in Turkey (Michael Fahrbach, pers. comm.). We used the R packages “gdsfmt” and “SNPRelate” (Zheng et al. 2012) on data from 24 Triturus ivanbureschi newts that originated from seven different wild populations and the captive population (i.e., three samples per population, see Table S1). Populations from the wild include both the glacial refugial area (Asia Minor and Turkish Thrace) and postglacially colonized area (the Balkans; Wielstra et al. 2017). We created a raw msgVCF file from these samples, which contained a total of 812,768 sites from across 7135 targets. We extracted high‐quality SNPs in the same way as we did for the hybrid studies (i.e., removing heterozygote excess, discarding indels, filtering out sites with poor quality scores, and allowing no missing data), and the filtered msgVCF that was used as input had a total of 486,891 SNPs from 5774 targets. We conducted the hybrid and conservation genetic analyses in Rstudio (Team_R_Studio 2021) using R v.4.1.2 (Team_R_Core 2020).

Finally, we were interested in the number of informative SNPs that we could find within Salamandridae species that are distantly related to T. dobrogicus . The most distantly related species for which we had more than one sample belonging to distinct populations in our dataset is Chioglossa lusitanica (Table S1), which is a true salamander, not a newt. Having more than one sample allows us to cross‐compare these populations. Thus, we extracted the variant information of the two C. lusitanica samples from the overall msgVCF file – filtered for high‐quality SNPs allowing no missing genotypes – that was used to estimate the genetic divergence from T. dobrogicus (De Visser et al. 2024). We quantified the number of SNPs that were homozygous in one sample and heterozygous in the other sample ‐ and vice versa. Additionally, we counted the number of SNPs that were homozygous in both samples, but for different alleles.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Performance of NewtCap

In total, we collected 149.0 GB of raw sequence data with, on average, 15,573,781 reads per sample (SD = 11,400,957, see Table S1 for the read counts per sample). On average, 42.6% (SD = 16.2%) of all reads were successfully mapped against the Triturus reference, and an average of 11.9% (SD = 10.6%) of all reads were marked as PCR duplicates. In the deduplicated BAM files, the mean read depth across all targets per sample varied widely and ranged from 5.9 X (SD = 27.9) in A. mexicanum and 8.2 X (SD = 27.8) in P. gorganensis to 122.2 X (SD = 345) in one of the Lissotriton hybrids. The mean coverage of the sequence bases of all targets ranged from 36.1% (SD = 30.3%) in P. gorganensis and 36.4% (SD = 31.3%) in A. mexicanum to 98.31% in two T. ivanbureschi samples (SD = 7.2% and SD = 6.9%). On average, the mean read depth was 60.5 X (SD = 183.2) across all samples, and the overall mean coverage of the sequence bases was 92.0% (SD = 13.7%). Details can be found in Table S1.

We discovered significant correlations between the genetic divergence from T. dobrogicus and several performance variables. Firstly, we found no significant correlation between the percentage of reads marked as PCR duplicates by Picard and the level of divergence from T. dobrogicus (Spearman's rank correlation test, R = 0.015, p = 0.91); however, we did find a negative correlation between the percentage of reads that map against the T. dobrogicus reference sequences and the amount of divergence from T. dobrogicus (Spearman's rank correlation test, R = −0.661, p < 0.001, Table 1). Furthermore, there is a negative correlation between the coverage of reference targets and the level of divergence from T. dobrogicus ‐ that is, the mean read depth and the mean coverage of the sequence bases both drop as the divergence from T. dobrogicus increases (Pearson correlation test for the mean read depth, R = −0.597, p < 0.001 and Spearman's rank correlation test for the mean coverage of the sequence bases, R = −0.918, p < 0.001; Table 1). Lastly, with increased divergence from T. dobrogicus , more SNPs and INDELs are discovered by BCFtools in the eventual gVCF files (Spearman's rank correlation test; R = 0.917 and p < 0.001 for SNPs, R = 0.899 and p < 0.001 for INDELs, Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Correlation statistics for the relationship between NewtCap performance variables and the estimated amount of species divergence from Triturus dobrogicus .

| Performance variable | Correlation test applied | R | R 2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of reads mapped | Spearman's rank | −0.661 | 0.440 | 3.6E‐10* |

| Percentage of PCR duplicates | Spearman's rank | 0.015 | < 0.001 | 0.910 |

| Mean read depth | Pearson | −0.597 | 0.357 | 3.8E‐08* |

| Mean coverage of sequence bases | Spearman's rank | −0.918 | 0.842 | 2.2E‐29* |

| Number of SNPs discovered | Spearman's rank | 0.917 | 0.841 | 2.7E‐29* |

| Number of INDELs discovered | Spearman's rank | 0.899 | 0.807 | 2.4E‐26* |

Note: For each of the separate performance variable the appropriate statistical test ‐ either the Spearman's rank or the Pearson correlation test ‐ was applied to determine whether the observed correlations were significant. Both the correlation coefficient (R) and its square value (R 2)Care provided, as well as the p value. Results with a p value lower than 0.008335 (including a Bonferroni correction, see Section 2) are marked with an asterisk.

3.2. Phylogenomics: Reconstruction of the Salamandridae Phylogeny

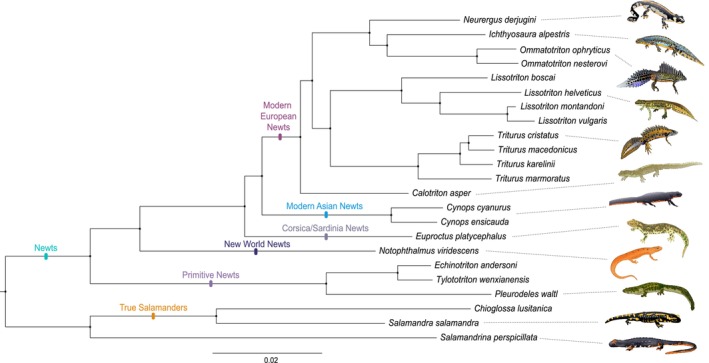

The fully resolved and highly supported Salamandridae phylogeny resulting from Maximum Likelihood analysis of concatenated data in RAxML was based on 204,600 polymorphic SNPs (Figure 1 and Figure S1). We recover the newts and the true salamanders as monophyletic groups. Within the newts, the modern European and modern Asian newts are sister lineages. Their closest relatives are the Corsica/Sardina newts. The New World newts are the sister lineage of this assemblage. Finally, these newt lineages coalesce with the primitive newts at the newt crown. The placement of the root on the branch connecting the newts and the clade containing the true salamanders and Salamandrina was confirmed by our extended phylogeny (based on 265,105 SNPs, Figure S2) that included two non‐Salamandridae salamander species ( A. mexicanum and P. gorganensis ), as well as an additional true salamander species ( M. caucasica , which is recovered as the sister lineage of Chioglossa).

FIGURE 1.

NewtCap‐based phylogeny of the Salamandridae family. The phylogeny is based on Maximum Likelihood inference of concatenated data of 204,600 informative SNPs using RAxML. Overall layout and clade labels conform to a previous transcriptome‐based phylogeny (Rancilhac et al. 2021). The tree is rooted on the branch separating the newts and the clade containing the true salamanders and Salamandrina (see also Figure S1 for the same tree, but with original labels, and Figure S2 for the additional, extended tree, including Ambystoma, Paradactylodon and Mertensiella, that confirms the root position adopted here). All nodes have a bootstrap support of 100%.

3.3. Phylogeography: Fully Resolved Relationships of Taricha

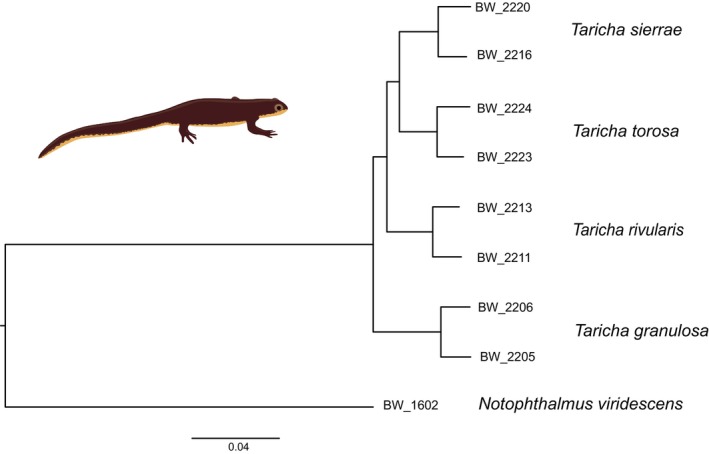

The Taricha phylogeny that resulted from the concatenated data used by RAxML to perform a Maximum Likelihood analysis was based on 9730 polymorphic SNPs. The tree was fully resolved and highly supported (Figure 2). All four Taricha species are recovered as reciprocally monophyletic. The basal bifurcation is between T. granulosa and the remainder. The subsequent split separates T. rivularis from T. torosa plus T. sierrae .

FIGURE 2.

A Taricha phylogeny obtained with NewtCap‐derived data. The phylogeny is based on Maximum Likelihood inference of concatenated data of 9,730 informative SNPs using RAxML. Notophthalmus is used to root the tree. All nodes have a bootstrap support of 100% (not shown).

3.4. Hybridization Studies: Lissotriton Hybrids and Backcrosses Detected

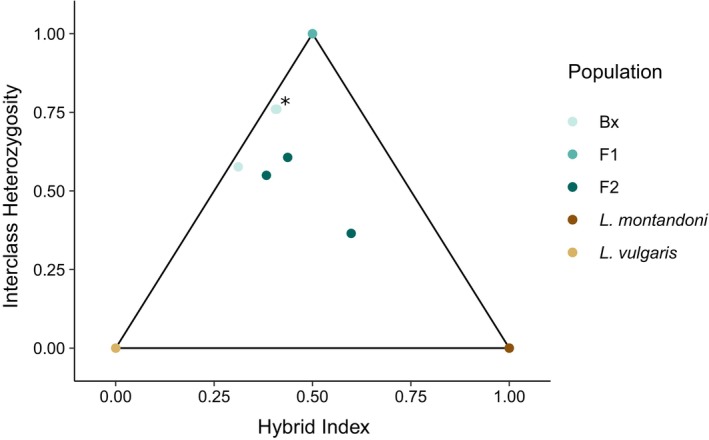

After quality filtering, we identified 666 SNPs that we consider species‐diagnostic (i.e., “ancestry‐informative”) for L. vulgaris versus L. montandoni in the target capture data based on the genotypes of the six parental species samples and three F1 hybrids. Those SNPs enabled us to calculate the hybrid indices and interclass heterozygosity values in F2 and backcross (“Bx”) hybrids, as visualized in a triangle plot (Figure 3). The backcross hybrids are placed along the edge of the triangle plot toward the appropriate parental species ( L. vulgaris ) whereas the F2 hybrids are placed more toward the center of the triangle plot.

FIGURE 3.

Triangle plot of different Lissotriton hybrid classes based on NewtCap‐derived data. The plot, based on 666 informative SNPs, shows the relationship between the hybrid index (the fraction of the alleles per individual that derived from each of the two parental species, also known as the ancestry) and the interclass heterozygosity (the fraction of the alleles per individual that is heterozygous for alleles from both parental species). The L. vulgaris individuals are in the bottom left corner, the L. montandoni individuals in the bottom right corner, and the F1 hybrid offspring in the top corner. The F2 and Bx (‘backcross’) hybrids are placed inside the triangle, with two Bx samples almost fully overlapping (marked with *).

3.5. Conservation Genetics: Separation of Triturus Populations and Chioglossa Subspecies

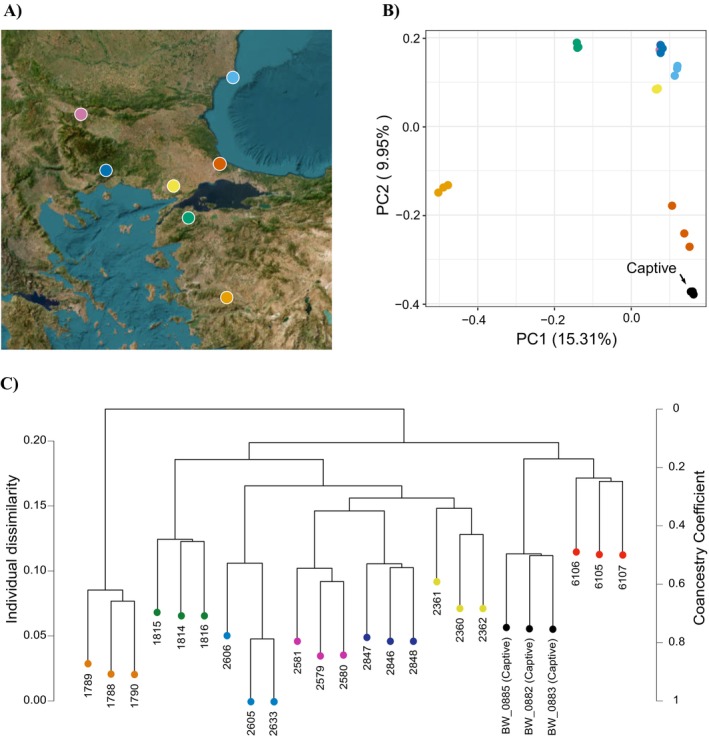

For the PCA and HCA analyses, the R calculations ended up being based on 9135 biallelic SNPs. Along the first and second Principal Components of the PCA, the four wild populations from the postglacially colonized area cluster together, whereas the three wild populations from the glacial refugial area stand relatively apart (Figure 4A,B). The captive‐bred individuals cluster closest to the Safaalan group, a population in Turkey just west of Istanbul, close to the presumed source locality Cerkezköy. The same pattern is observed in the HCA dendogram (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Genetic differentiation between wild and captive Triturus ivanbureschi populations based on NewtCap‐derived data. (A) The wild population localities (details in Table S1; four postglacial populations are represented by dark blue, light blue, yellow, and pink colors in Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey, and three populations from the glacial refugial area are represented by red, orange and green colors in Turkey). (B) A plot of the first versus the second Principal Component (PC) places the captive individuals closest to a population from just west of Istanbul. (C) The dendrogram produced by the HCA analysis, showing the Individual Dissimilarity as well as the Coancestry Coefficient, again shows that captive samples cluster with a population just west of Istanbul.

The check for high‐quality SNPs that display different genotypes in the two C. lusitanica samples originating from different subspecies, resulted in a list of over 10,000 polymorphic SNPs: we counted 8029 SNPs for which one individual was homozygous, and the other individual was heterozygous, and we discovered an additional 2301 informative SNPs where the individuals were both homozygous, but for alternate alleles.

4. Discussion

We introduce NewtCap, a target capture bait and reference set of 7139 sequences applicable to salamandrids. We show that NewtCap works effectively across all main lineages within the Salamandridae family. As anticipated, the target capture performance and mapping successes are influenced by the level of genetic divergence from T. dobrogicus , and we do see that—within Salamandridae—more off‐target regions are getting captured for more distantly related species. However, these influences appear to be minor and evidently do not hamper our downstream analyses: only for salamanders outside of the family Salamandridae does NewtCap provide data of insufficient quality. NewtCap thus proves to be a powerful tool to collect genomic data for Salamandridae studies regarding systematics (e.g., phylogenomics, phylogeography) and population genetics (e.g., hybrid studies, conservation genetics).

We encourage potential users to further tweak the NewtCap workflow. For instance, in terms of the laboratory protocol, researchers could consider: (1) replacing the C0t‐1 blocker with a standard blocker, (2) reducing the hybridization time, and (3) including more individuals per capture reaction. In terms of bioinformatics, the lower mapping rate observed in Salamandridae species more distantly related to T. dobrogicus does not necessarily only reflect decreased enrichment efficiency due to genetic divergence; the mapping rate is presumably also influenced by the reduced ability of the read mapper to align sequencing reads to more divergent reference sequences used in the bioinformatics pipeline (Bragg et al. 2016; Andermann et al. 2018). Users could explore applying different mapping settings, using alternative mapper tools, or making use of (or generating) substitute reference sequences for read alignment (Schilbert et al. 2020; Andermann et al. 2019).

Our findings demonstrate that the current NewtCap protocol can effectively be applied to any member of the family Salamandridae—the crown of which is dated as far back as c. 100 MYA (Steinfartz et al. 2007; De Visser et al. 2024). Our Salamandridae phylogeny perfectly matches the topology of a transcriptome‐based phylogeny (Rancilhac et al. 2021). Although a higher number of molecular markers does not necessarily result in a more accurate species tree (Mirarab et al. 2024; Zhang et al. 2021), independent RAxML analyses using different subsets of NewtCap data result in the same topology (with one notable exception, see; De Visser et al. 2024; France, De Visser, et al. 2024).

NewtCap has already recently been applied to study the systematics and taxonomy of certain modern European newts—including the genera Triturus (Wielstra et al. 2019; Kazilas et al. 2024), Lissotriton (Mars et al. 2025), Neurergus (Koster et al. 2025) and Ommatotriton (Kalaentzis et al. 2025). However, we show that NewtCap allows for a (putative) genome‐wide subsampling of thousands of markers for other Salamandridae lineages as well. Existing phylogenies of modern Asian newts (genera Cynops, Paramesotriton, and Pachytriton; Figure 1) rely on a limited amount of molecular markers and frequently fail to recover genera within the clade as monophyletic groups, presumably due to the intricate biogeographical history of this clade (Veith et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2008; Kieren et al. 2018). The New World newts (genera Taricha and Notophthalmus; Figure 1) have so far only been studied based on mtDNA and allozyme data (Lawson and Kilpatrick 2014; Gabor and Nice 2004; Whitmore et al. 2013; Kuchta and Tan 2006, 2005). Our Taricha phylogeny, the first one based on a considerable number of nuclear markers/SNPs, comprises a fully supported positioning of each of the four known species, with a topology that matches that of an existing mtDNA‐based phylogeny (Tan and Wake 1995; Tan 1993). For the Asian members of the primitive newts (genera Tylototriton and Echinotriton; see Figure 1), genetic resources have been scarce so far, which is why there is an outstanding call to conduct more extensive genomic research in order to better understand the evolution and taxonomy of the (sub)species of these lineages (Dufresnes and Hernandez 2022; Weisrock et al. 2006).

NewtCap performs well even for the sister clade of the newts, containing the “true salamanders” (Salamandra, Chioglossa, Mertensiella, Lyciasalamandra; see Figure 1) and the spectacled salamanders (Salamandrina). First, NewtCap provides empirical support for the recent suggestion that Salamandrina represents the sister lineage to the true salamanders instead of to all remaining salamandrids (Rancilhac et al. 2021). Salamandrina itself has so far only been studied with a relatively small number of markers (Mattoccia et al. 2011, 2005; Canestrelli et al. 2014; Hauswaldt et al. 2014; Veith et al. 2009; Weisrock et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2008). Chioglossa is a monotypic genus that is close to becoming threatened according to the IUCN Red List (IUCN_SSC_AMPHIBIAN_SPECIALIST_GROUP 2022). Conservationists generally identify monotypic taxa as “evolutionarily unique,” which helps justify elevated conservation imperatives (Liu et al. 2021; Vane‐Wright et al. 1991; Vitt et al. 2023). We obtained c. ten thousand informative SNPs distinguishing two individuals belonging to different C. lusitanica subspecies (Sequeira et al. 2022). The sister genus of Chioglossa, Mertensiella, is monotypic as well, but so far few populations have been studied and only with mtDNA (Tarkhnishvili et al. 2000; Weisrock et al. 2001).

Next to accentuating the potential of NewtCap in the context of conservation genetics, we emphasize that the tool can also be used to identify the degree of interspecific gene flow and geographical structuring. For example, to test hypotheses about species status and historical biogeography. Introgressive hybridization is increasingly recognized as a source of adaptive variation in natural populations (Fijarczyk et al. 2018; Li et al. 2016; Mallet 2005), but also as a source of genetic pollution in the case where non‐native and native individuals interbreed in nature (Quilodran et al. 2020; Wielstra et al. 2016; Simberloff 2013; Dufresnes et al. 2015). We identify different hybrid classes of Lissotriton newts and are able to differentiate between genetically distinct groups of T. ivanbureschi —and determine to which wild population a known, captive population is genetically most similar. Such applications are valuable for guiding wildlife management practices and conservation efforts that concern Salamandridae species both in situ and ex situ (Frankham et al. 2004; Ørsted et al. 2019; Weisrock et al. 2018). This is especially important considering that, out of all vertebrate groups, amphibians are facing the most drastic population declines and extinction rates observed in the Anthropocene (Stuart et al. 2004; Hayes et al. 2010; Sparreboom 2014; Lucas et al. 2024; Martel et al. 2013). Overall, by providing in the range of thousands to hundreds of thousands of high‐quality SNPs, NewtCap facilitates the molecular study of salamandrids whilst whole genome sequencing of the gigantic genomes of salamanders remains unattainable.

Author Contributions

Manon Chantal de Visser: conceptualization (equal), data curation (lead), formal analysis (lead), investigation (lead), methodology (equal), project administration (supporting), resources (equal), software (lead), validation (lead), visualization (lead), writing – original draft (equal), writing – review and editing (lead). James France: conceptualization (equal), data curation (supporting), methodology (equal), project administration (supporting), resources (lead), validation (lead), writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal). Evan McCartney‐Melstad: methodology (supporting), resources (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal). Gary M. Bucciarelli: data curation (supporting), methodology (supporting), resources (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal). Anagnostis Theodoropoulos: data curation (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal). Howard Bradley Shaffer: conceptualization (supporting), funding acquisition (supporting), resources (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal). Ben Wielstra: conceptualization (equal), funding acquisition (lead), methodology (equal), project administration (lead), resources (equal), supervision (lead), writing – original draft (equal), writing – review and editing (equal).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Data S1: ece371835‐sup‐0001‐SupinfoS1.zip.

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the European Research Council grant agreement No. 802759 and the Marie Skłodowska‐Curie grant agreement No. 655487. This work was performed using the compute resources from the Academic Leiden Interdisciplinary Cluster Environment (ALICE) provided by Leiden University. Daniele Canestrelli, Andrea Chiocchio, Michael Fahrbach, Willem Meilink, and Frank Pasmans contributed samples. The tissue sample of Notophthalmus viridescens (SMF 99040) was donated by the Senckenberg Research Institute and Nature Museum. The Taricha tissue samples were collected following protocols for animal welfare approved by UCLA and permitted by California Department of Fish and Wildlife (SCP # 12430). We would like to thank Erik‐Jan Bosch for making the scientific drawings of the salamanders used in Figure 1 under the open content License of Naturalis Biodiversity Center (CC BY‐NC‐ND 4.0), Benjamin Wiens for providing support with triangulaR adjustments, and Dr. Peter Scott for providing input on bioinformatic analyses. The Triturus ivanbureschi geographical map cut‐out (Figure 4A) was made thanks to OpenStreetMap and its contributors (CC BY‐SA 2.0), and we obtained the Taricha cartoon from Figure 2 copyright free via user “clker‐free‐vector‐images‐3736” through Pixabay.com.

de Visser, M. C. , France J., McCartney‐Melstad E., et al. 2025. “ NewtCap: An Efficient Target Capture Approach to Boost Genomic Studies in Salamandridae (True Salamanders and Newts).” Ecology and Evolution 15, no. 8: e71835. 10.1002/ece3.71835.

Funding: This work was supported by HORIZON EUROPE Marie Sklodowska‐Curie Actions (655487); H2020 European Research Council (802759).

Data Availability Statement

The samples used in this study are in compliance with national laws and the Nagoya Protocol and detailed information can be found in Supporting Information. Raw sequencing reads are accessible via BioProject “PRJNA1171613” (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1171613). The main bioinformatic steps and scripts are provided on our GitHub (https://github.com/Wielstra‐Lab/NewtCap_bioinformatics).

References

- Albert, T. J. , Molla M. N., Muzny D. M., et al. 2007. “Direct Selection of Human Genomic Loci by Microarray Hybridization.” Nature Methods 4: 903–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro, M. E. , Faircloth B. C., Harrington R. C., et al. 2018. “Explosive Diversification of Marine Fishes at the Cretaceous‐Palaeogene Boundary.” Nature Ecology & Evolution 2: 688–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andermann, T. , Cano A., Zizka A., Bacon C., and Antonelli A.. 2018. “SECAPR‐a Bioinformatics Pipeline for the Rapid and User‐Friendly Processing of Targeted Enriched Illumina Sequences, From Raw Reads to Alignments.” PeerJ 6: e5175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andermann, T. , Torres Jimenez M. F., Matos‐Maravi P., et al. 2019. “A Guide to Carrying out a Phylogenomic Target Sequence Capture Project.” Frontiers in Genetics 10: 1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, K. R. , Good J. M., Miller M. R., Luikart G., and Hohenlohe P. A.. 2016. “Harnessing the Power of RADseq for Ecological and Evolutionary Genomics.” Nature Reviews. Genetics 17: 81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S. 2010. “FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data.”

- Arnold, B. , Corbett‐Detig R. B., Hartl D., and Bomblies K.. 2013. “RADseq Underestimates Diversity and Introduces Genealogical Biases due to Nonrandom Haplotype Sampling.” Molecular Ecology 22: 3179–3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auwera, G. A. , and O'connor B. D.. 2020. Genomics in the Cloud: Using Docker, Gatk, and WDL in Terra. O'Reilly Media. [Google Scholar]

- Babik, W. , Marszalek M., Dudek K., et al. 2024. “Limited Evidence for Genetic Differentiation or Adaptation in Two Amphibian Species Across Replicated Rural‐Urban Gradients.” Evolutionary Applications 17: e13700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi, K. , Vanderpool D., Singhal S., Linderoth T., Moritz C., and Good J. M.. 2012. “Transcriptome‐Based Exon Capture Enables Highly Cost‐Effective Comparative Genomic Data Colection at Moderate Evolutionary Scales.” BMC Genomics 13: 1471–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, A. M. , Lohse M., and Usadel B.. 2014. “Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data.” Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragg, J. G. , Potter S., Bi K., and Moritz C.. 2016. “Exon Capture Phylogenomics: Efficacy Across Scales of Divergence.” Molecular Ecology Resources 16: 1059–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgon, J. D. , Vences M., Steinfartz S., et al. 2021. “Phylogenomic Inference of Species and Subspecies Diversity in the Palearctic Salamander Genus Salamandra .” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 157: 107063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calboli, F. C. , Fisher M. C., Garner T. W., and Jehle R.. 2011. “The Need for Jumpstarting Amphibian Genome Projects.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 26: 378–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canestrelli, D. , Bisconti R., and Nascetti G.. 2014. “Extensive Unidirectional Introgression Between Two Salamander Lineages of Ancient Divergence and Its Evolutionary Implications.” Scientific Reports 4: 6516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Fonseca, R. R. , Albrechtsen A., Themudo G. E., et al. 2016. “Next‐Generation Biology: Sequencing and Data Analysis Approaches for Non‐Model Organisms.” Marine Genomics 30: 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek, P. , Bonfield J. K., Liddle J., et al. 2021. “Twelve Years of SAMtools and BCFtools.” GigaScience 10: giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey, J. W. , Cezard T., Fuentes‐Utrilla P., Eland C., Gharbi K., and Blaxter M. L.. 2013. “Special Features of RAD Sequencing Data: Implications for Genotyping.” Molecular Ecology 22: 3151–3164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Visser, M. C. , France J., Paulouskaya O., et al. 2024. “Conserved Gene Content and Unique Phylogenetic History Characterize the ‘Bloopergene’ Underlying Triturus' Balanced Lethal System.” bioRxiv, 2024.10.25.620277.

- Dodsworth, S. , Pokorny L., Johnson M. G., et al. 2019. “Hyb‐Seq for Flowering Plant Systematics.” Trends in Plant Science 24: 887–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufresnes, C. , Dubey S., Ghali K., Canestrelli D., and Perrin N.. 2015. “Introgressive Hybridization of Threatened European Tree Frogs ( Hyla arborea ) by Introduced H. intermedia in Western Switzerland.” Conservation Genetics 16: 1507–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Dufresnes, C. , and Hernandez A.. 2022. “Towards Completing the Crocodile Newts' Puzzle With All‐Inclusive Phylogeographic Resources.” Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 197: 620–640. [Google Scholar]

- Faircloth, B. C. , Branstetter M. G., White N. D., and Brady S. G.. 2015. “Target Enrichment of Ultraconserved Elements From Arthropods Provides a Genomic Perspective on Relationships Among Hymenoptera.” Molecular Ecology Resources 15: 489–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, L. A. , and McGaughran A.. 2024. “The Effect of Missing Data on Evolutionary Analysis of Sequence Capture Bycatch, With Application to an Agricultural Pest.” Molecular Genetics and Genomics 299: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fijarczyk, A. , Dudek K., Niedzicka M., and Babik W.. 2018. “Balancing Selection and Introgression of Newt Immune‐Response Genes.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 285: 20180819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, B. M. , McCartney‐Melstad E., Johnson J. R., and Shaffer H. B.. 2024. “New Evidence Contradicts the Rapid Spread of Invasive Genes Into a Threatened Native Species.” Biological Invasions 26: 3353–3367. [Google Scholar]

- France, J. , Babik W., Dudek K., Marszałek M., and Wielstra B.. 2025. “Linkage Mapping vs Association: A Comparison of Two RADseq‐Based Approaches to Identify Markers for Homomorphic Sex Chromosomes in Large Genomes.” Molecular Ecology Resources :e70019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France, J. , De Visser M., Arntzen J. W., et al. 2024. “The Balanced Lethal System in Triturus Newts Originated in an Instantaneous Speciation Event.” bioRxiv, 2024.10.29.620207.

- Frankham, R. , Ballou J. D., and Briscoe D. A.. 2004. A Primer of Conservation Genetics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, D. R. 1985. Amphibian Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Association of Systematic Collections. [Google Scholar]

- Gabor, C. R. , and Nice C. C.. 2004. “Genetic Variation Among Populations of Eastern Newts, Notophthalmus viridescens : A Preliminary Analysis Based on Allozymes.” Herpetologica 60: 373–386. [Google Scholar]

- Gnirke, A. , Melnikov A., Maguire J., et al. 2009. “Solution Hybrid Selection With Ultra‐Long Oligonucleotides for Massively Parallel Targeted Sequencing.” Nature Biotechnology 27: 182–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good, J. M. 2011. “Reduced Representation Methods for Subgenomic Enrichment and Next‐Generation Sequencing.” Molecular Methods for Evolutionary Genetics 772: 85–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, T. R. 2002. “Genome Size and Developmental Complexity.” Genetica 115: 131–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, T. R. 2024. “Animal Genome Size Database [Online].” http://www.genomesize.com.

- Grover, C. E. , Salmon A., and Wendel J. F.. 2012. “Targeted Sequence Capture as a Powerful Tool for Evolutionary Analysis.” American Journal of Botany 99: 312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. , Long J., He J., et al. 2012. “Exome Sequencing Generates High Quality Data in Non‐Target Regions.” BMC Genomics 13: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, M. G. , Smith B. T., Glenn T. C., Faircloth B. C., and Brumfield R. T.. 2016. “Sequence Capture Versus Restriction Site Associated DNA Sequencing for Shallow Systematics.” Systematic Biology 65: 910–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauswaldt, J. S. , Angelini C., Gehara M., Benavides E., Polok A., and Steinfartz S.. 2014. “From Species Divergence to Population Structure: A Multimarker Approach on the Most Basal Lineage of Salamandridae, the Spectacled Salamanders (Genus Salamandrina) From Italy.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 70: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, T. B. , Falso P., Gallipeau S., and Stice M.. 2010. “The Cause of Global Amphibian Declines: A Developmental Endocrinologist's Perspective.” Journal of Experimental Biology 213: 921–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyduk, K. , Stephens J. D., Faircloth B. C., and Glenn T. C.. 2016. “Targeted DNA Region Re‐Sequencing.” In Field Guidelines for Genetic Experimental Designs in High‐Throughput Sequencing. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Q. , Chang C., Wang Q., et al. 2019. “Genome‐Wide RAD Sequencing to Identify a Sex‐Specific Marker in Chinese Giant Salamander Andrias davidianus .” BMC Genomics 20: 415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbs, N. W. , Hurt C. R., Niedzwiecki J., Leckie B., and Withers D.. 2022. “Conservation Genomics of Urban Populations of Streamside Salamander ( Ambystoma barbouri ).” PLoS One 17: e0260178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, C. R. , Cobb K. A., Portik D. M., Travers S. L., Wood P. L. JR., and Brown R. M.. 2022. “FrogCap: A Modular Sequence Capture Probe‐Set for Phylogenomics and Population Genetics for All Frogs, Assessed Across Multiple Phylogenetic Scales.” Molecular Ecology Resources 22: 1100–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group . 2022. “ Chioglossa lusitanica . The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022.” [Online]. 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T4657A89698017.en. [DOI]

- Jimenez‐Mena, B. , Flavio H., Henriques R., et al. 2022. “Fishing for DNA? Designing Baits for Population Genetics in Target Enrichment Experiments: Guidelines, Considerations and the New Tool supeRbaits.” Molecular Ecology Resources 22: 2105–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. R. , and Good J. M.. 2016. “Targeted Capture in Evolutionary and Ecological Genomics.” Molecular Ecology 25: 185–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaentzis, K. , Koster S., Arntzen J. W., et al. 2025. “Phylogenomics Resolves the Puzzling Phylogeny of Banded Newts (Genus Ommatotriton).” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 203: 108237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazilas, C. , Dufresnes C., France J., et al. 2024. “Spatial Genetic Structure in European Marbled Newts Revealed With Target Enrichment by Sequence Capture.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 194: 108043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R. , Biffin E., Van Dijk K. J., Hill R. S., Liu J., and Waycott M.. 2024. “Development of a Target Enrichment Probe Set for Conifer (REMcon).” Biology (Basel) 13: 361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieren, S. , Sparreboom M., Hochkirch A., and Veith M.. 2018. “A Biogeographic and Ecological Perspective to the Evolution of Reproductive Behaviour in the Family Salamandridae.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 121: 98–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus, B. J. , and Grunwald N. J.. 2017. “VcfR: A Package to Manipulate and Visualize Variant Call Format Data in R.” Molecular Ecology Resources 17: 44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster, S. , Polanen R., AVCı A., et al. 2025. “Discordance Between Phylogenomic Methods in Near Eastern Mountain Newts (Neurergus, Salamandridae).” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 211: 108386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchta, S. R. , and Tan A. M.. 2005. “Isolation by Distance and Post‐Glacial Range Expansion in the Rough‐Skinned Newt, Taricha granulosa .” Molecular Ecology 14: 225–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchta, S. R. , and Tan A.‐M.. 2006. “Lineage Diversification on an Evolving Landscape: Phylogeography of the California Newt, Taricha torosa (Caudata: Salamandridae).” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 89: 213–239. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, G. R. , and Kilpatrick E. S.. 2014. “Phylogeographic Patterns Among the Subspecies of Notophthalmus viridescens (Eastern Newt) in South Carolina.” Southeastern Naturalist 13: 444–455. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon, E. M. , and Lemmon A. R.. 2013. “High‐Throughput Genomic Data in Systematics and Phylogenetics.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 44: 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P. O. 2001. “A Likelihood Approach to Estimating Phylogeny From Discrete Morphological Character Data.” Systematic Biology 50: 913–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. , Davis B. W., Eizirik E., and Murphy W. J.. 2016. “Phylogenomic Evidence for Ancient Hybridization in the Genomes of Living Cats (Felidae).” Genome Research 26: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. 2011. “A Statistical Framework for SNP Calling, Mutation Discovery, Association Mapping and Population Genetical Parameter Estimation From Sequencing Data.” Bioinformatics 27: 2987–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. 2013. “Aligning Sequence Reads, Clone Sequences and Assembly Contigs With BWA‐MEM.” arXiv.

- Li, H. , Handsaker B., Wysoker A., et al. 2009. “The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools.” Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvinchuk, S. N. , Rosanov J. M., and Borkin L. J.. 2007. “Correlations of Geographic Distribution and Temperature of Embryonic Development With the Nuclear DNA Content in the Salamandridae (Urodela, Amphibia).” Genome 50: 333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. , Bosse M., Megens H. J., De Visser M., Groenen M. A. M., and Madsen O.. 2021. “Genetic Consequences of Long‐Term Small Effective Population Size in the Critically Endangered Pygmy Hog.” Evolutionary Applications 14: 710–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou, R. N. , Jacobs A., Wilder A. P., and Therkildsen N. O.. 2021. “A Beginner's Guide to Low‐Coverage Whole Genome Sequencing for Population Genomics.” Molecular Ecology 30: 5966–5993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, D. B. , Hoban S., Kelley J. L., et al. 2017. “Breaking RAD: An Evaluation of the Utility of Restriction Site‐Associated DNA Sequencing for Genome Scans of Adaptation.” Molecular Ecology Resources 17: 142–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, P. M. , Di Marco M., Cazalis V., et al. 2024. “Using Comparative Extinction Risk Analysis to Prioritize the IUCN Red List Reassessments of Amphibians.” Conservation Biology 38: e14316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet, J. 2005. “Hybridization as an Invasion of the Genome.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20: 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamanova, L. , Coffey A. J., Scott C. E., et al. 2010. “Target‐Enrichment Strategies for Next‐Generation Sequencing.” Nature Methods 7: 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marjanović, D. , and Laurin M.. 2013. “An Updated Paleontological Timetree of Lissamphibians, With Comments on the Anatomy of Jurassic Crown‐Group Salamanders (Urodela).” Historical Biology 26: 535–550. [Google Scholar]

- Mars, J. , Koster S., Babik W., et al. 2025. “Phylogenomics Yields New Systematic and Taxonomical Insights for Lissotriton Newts, a Genus With a Strong Legacy of Introgressive Hybridization.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 204: 108282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel, A. , Spitzen‐Van Der Sluijs A., Blooi M., et al. 2013. “ Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans sp. nov. Causes Lethal Chytridiomycosis in Amphibians.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: 15325–15329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattoccia, M. , Marta S., Romano A., and Sbordoni V.. 2011. “Phylogeography of an Italian Endemic Salamander (Genus Salamandrina): Glacial Refugia, Postglacial Expansions, and Secondary Contact.” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 104: 903–992. [Google Scholar]

- Mattoccia, M. , Romano A., and Sbordoni V.. 2005. “Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Analysis of the Spectacled Salamander, Salamandrina terdigitata (Urodela: Salamandridae), Supports the Existence of Two Distinct Species.” Zootaxa 995: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- McCartney‐Melstad, E. , Mount G. G., and Shaffer H. B.. 2016. “Exon Capture Optimization in Amphibians With Large Genomes.” Molecular Ecology Resources 16: 1084–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meilink, W. R. M. , Arntzen J. W., van Delft J. J. C. W., and Wielstra B.. 2015. “Genetic Pollution of a Threatened Native Crested Newt Species Through Hybridization With an Invasive Congener in the Netherlands.” Biological Conservation 184: 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Mirarab, S. , Rivas‐Gonzalez I., Feng S., et al. 2024. “A Region of Suppressed Recombination Misleads Neoavian Phylogenomics.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121: e2319506121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ørsted, M. , Hoffmann A. A., Sverrisdóttir E., Nielsen K. L., and Kristensen T. N.. 2019. “Genomic Variation Predicts Adaptive Evolutionary Responses Better Than Population Bottleneck History.” PLoS Genetics 15: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, E. M. 2019. “vcf2phylip v2. 0: Convert a VCF Matrix Into Several Matrix Formats for Phylogenetic Analysis.”

- Pasmans, F. , Bogaerts S., Woeltjes T., and Carranza S.. 2006. “Biogeography of Neurergus strauchii barani Öz, 1994 and N. s. strauchii (Steindachner, 1887) (Amphibia: Salamandridae) Assessed Using Morphological and Molecular Data.” Amphibia‐Reptilia 27: 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Poplin, R. , Ruano‐Rubio V., Depristo M. A., et al. 2017. “Scaling Accurate Genetic Variant Discovery to Tens of Thousands of Samples.” bioRxiv, 201178.

- Portik, D. M. , Smith L. L., and Bi K.. 2016. “An Evaluation of Transcriptome‐Based Exon Capture for Frog Phylogenomics Across Multiple Scales of Divergence (Class: Amphibia, Order: Anura).” Molecular Ecology Resources 16: 1069–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quek, Z. B. R. , and Ng S. H.. 2024. “Hybrid‐Capture Target Enrichment in Human Pathogens: Identification, Evolution, Biosurveillance, and Genomic Epidemiology.” Pathogens 13: 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilodran, C. S. , Montoya‐Burgos J. I., and Currat M.. 2020. “Harmonizing Hybridization Dissonance in Conservation.” Communications Biology 3: 391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rancilhac, L. , Goudarzi F., Gehara M., et al. 2019. “Phylogeny and Species Delimitation of Near Eastern Neurergus Newts (Salamandridae) Based on Genome‐Wide RADseq Data Analysis.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 133: 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rancilhac, L. , Irisarri I., Angelini C., et al. 2021. “Phylotranscriptomic Evidence for Pervasive Ancient Hybridization Among Old World Salamanders.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 155: 106967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbemont, J. , Van Veldhuijzen S., Allain S. J. R., et al. 2023. “An Extended mtDNA Phylogeography for the Alpine Newt Illuminates the Provenance of Introduced Populations.” Amphibia‐Reptilia 44: 347–361. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, A. , Burgon J. D., Lyra M., et al. 2017. “Inferring the Shallow Phylogeny of True Salamanders (Salamandra) by Multiple Phylogenomic Approaches.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 115: 16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, B. E. , Ree R. H., and Moreau C. S.. 2012. “Inferring Phylogenies From RAD Sequence Data.” PLoS One 7: e33394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J. , and Russell D. W.. 2001. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd ed. Coldspring‐Harbour Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schilbert, H. M. , Rempel A., and Pucker B.. 2020. “Comparison of Read Mapping and Variant Calling Tools for the Analysis of Plant NGS Data.” Plants (Basel) 9: 439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott, R. K. , Panesar B., Card D. C., Preston M., Castoe T. A., and Chang B. S.. 2017. “Targeted Capture of Complete Coding Regions Across Divergent Species.” Genome Biology and Evolution 9: 398–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, P. A. , Najafi‐Majd E., Yildirim Caynak E., Gidis M., Kaya U., and Bradley Shaffer H.. 2024. “Phylogenomics Reveal Species Limits and Inter‐Relationships in the Narrow‐Range Endemic Lycian Salamanders.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 202: 108205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira, F. , Arntzen J. W., Van Gulik D., et al. 2022. “Genetic Traces of Hybrid Zone Movement Across a Fragmented Habitat.” Journal of Evolutionary Biology 35: 400–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions, S. K. 2008. “Evolutionary Cytogenetics in Salamanders.” Chromosome Research 16: 183–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simberloff, D. 2013. Invasive Species: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, S. , Grundler M., Colli G., and Rabosky D. L.. 2017. “Squamate Conserved Loci (SqCL): A Unified Set of Conserved Loci for Phylogenomics and Population Genetics of Squamate Reptiles.” Molecular Ecology Resources 17: e12–e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. J. , Timoshevskaya N., Timoshevskiy V. A., Keinath M. C., Hardy D., and Voss S. R.. 2019. “A Chromosome‐Scale Assembly of the Axolotl Genome.” Genome Research 29: 317–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparreboom, M. 2014. “Salamanders of the Old World: The Salamanders of Europe, Asia and Northern Africa.”

- Stamatakis, A. 2014. “RAxML Version 8: A Tool for Phylogenetic Analysis and Post‐Analysis of Large Phylogenies.” Bioinformatics 30: 1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfartz, S. , Vicario S., Arntzen J. W., and Caccone A.. 2007. “A Bayesian Approach on Molecules and Behavior: Reconsidering Phylogenetic and Evolutionary Atterns of the Salamandridae With Emphasis on Triturus Newts.” Journal of Experimental Zoology. Part B, Molecular and Developmental Evolution 308B: 139–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, S. N. , Chanson J. S., Cox N. A., et al. 2004. “Status and Trends of Amphibian Declines and Extinctions Worldwide.” Science 306: 1783–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C. , Shepard D. B., Chong R. A., et al. 2012. “LTR Retrotransposons Contribute to Genomic Gigantism in Plethodontid Salamanders.” Genome Biology and Evolution 4: 168–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, A.‐M. 1993. Systematics, Phylogeny and Biogeography of the Northwest American Newts of the Genus Taricha (Caudata: Salamandridae). University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, A.‐M. , and Wake D. B.. 1995. “MtDNA Phylogeography of the California Newt, Taricha torosa (Caudata, Salamandridae).” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 4: 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkhnishvili, D. N. , Thorpe R. S., and Arntzen J. W.. 2000. “Pre‐Pleistocene Refugia and Differentiation Between Populations of the Caucasian Salamander ( Mertensiella caucasica ).” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 14: 414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team, R. Core . 2020. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Team, R. Studio . 2021. “RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R.”

- Teasdale, L. C. , Kohler F., Murray K. D., O'hara T., and Moussalli A.. 2016. “Identification and Qualification of 500 Nuclear, Single‐Copy, Orthologous Genes for the Eupulmonata (Gastropoda) Using Transcriptome Sequencing and Exon Capture.” Molecular Ecology Resources 16: 1107–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valbuena‐Urena, E. , Amat F., and Carranza S.. 2013. “Integrative Phylogeography of Calotriton Newts (Amphibia, Salamandridae), With Special Remarks on the Conservation of the Endangered Montseny Brook Newt (Calotriton arnoldi).” PLoS One 8: e62542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vane‐Wright, R. I. , Humphries C. J., and Williams P. H.. 1991. “What to Protect? ‐ Systematics and the Agony of Choice.” Biological Conservation 55: 235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Veith, M. , Bogaerts S., Pasmans F., and Kieren S.. 2018. “The Changing Views on the Evolutionary Relationships of Extant Salamandridae (Amphibia: Urodela).” PLoS One 13: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veith, M. , Steinfartz S., Zardoya R., Seitz A., and Meyer A.. 2009. “A Molecular Phylogeny of ‘True’ Salamanders (Family Salamandridae) and the Evolution of Terrestriality of Reproductive Modes.” Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 36: 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Vitt, P. , Taylor A., Rakosy D., et al. 2023. “Global Conservation Prioritization for the Orchidaceae.” Scientific Reports 13: 6718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisrock, D. W. , Hime P. M., Nunziata S. O., et al. 2018. “Surmounting the Large‐Genome “Problem” for Genomic Data Generation in Salamanders.” In Population Genomics: Wildlife, edited by Hohenlohe P. A. and Rajora O. P.. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Weisrock, D. W. , Macey J. R., Ugurtas I. H., Larson A., and Papenfuss T. J.. 2001. “Molecular Phylogenetics and Historical Biogeography Among Salamandrids of the “True” Salamander Clade: Rapid Branching of Numerous Highly Divergent Lineages in Mertensiella luschani Associated With the Rise of Anatolia.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 18: 434–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisrock, D. W. , Papenfuss T. J., Macey J. R., et al. 2006. “A Molecular Assessment of Phylogenetic Relationships and Lineage Accumulation Rates Within the Family Salamandridae (Amphibia, Caudata).” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 41: 368–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore, S. S. , Losee S., Meyer L., and Spradling T. A.. 2013. “Conservation Genetics of the Central Newt ( Notophthalmus viridescens ) in Iowa: The Importance of a Biogeographic Framework.” Conservation Genetics 14: 771–781. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. 2011. “ggplot2.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics 3: 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Wielstra, B. , Burke T., Butlin R. K., et al. 2016. “Efficient Screening for ‘Genetic Pollution’ in an Anthropogenic Crested Newt Hybrid Zone.” Conservation Genetics Resources 8: 553–560. [Google Scholar]

- Wielstra, B. , Burke T., Butlin R. K., and Arntzen J. W.. 2017. “A Signature of Dynamic Biogeography: Enclaves Indicate Past Species Replacement.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 284: 20172014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielstra, B. , McCartney‐Melstad E., Arntzen J. W., Butlin R. K., and Shaffer H. B.. 2019. “Phylogenomics of the Adaptive Radiation of Triturus Newts Supports Gradual Ecological Niche Expansion Towards an Incrementally Aquatic Lifestyle.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 133: 120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens, B. J. , and Colella J. P.. 2024. “triangulaR: An R Package for Identifying AIMs and Building Triangle Plots Using SNP Data From Hybrid Zones.” bioRxiv, 2024.03.28.587167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yu, P. L. , Fulton J. C., Hudson O. H., Huguet‐Tapia J. C., and Brawner J. T.. 2023. “Next‐Generation Fungal Identification Using Target Enrichment and Nanopore Sequencing.” BMC Genomics 24: 581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaharias, P. , Pante E., Gey D., Fedosov A. E., and Puillandre N.. 2020. “Data, Time and Money: Evaluating the Best Compromise for Inferring Molecular Phylogenies of Non‐Model Animal Taxa.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 142: 106660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. , Rheindt F. E., She H., et al. 2021. “Most Genomic Loci Misrepresent the Phylogeny of an Avian Radiation Because of Ancient Gene Flow.” Systematic Biology 70: 961–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P. , Papenfuss T. J., Wake M. H., Qu L., and Wake D. B.. 2008. “Phylogeny and Biogeography of the Family Salamandridae (Amphibia: Caudata) Inferred From Complete Mitochondrial Genomes.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 49: 586–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X. , Levine D., Shen J., Gogarten S. M., Laurie C., and Weir B. S.. 2012. “A High‐Performance Computing Toolset for Relatedness and Principal Component Analysis of SNP Data.” Bioinformatics 28: 3326–3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L. , and Holliday J. A.. 2012. “Targeted Enrichment of the Black Cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa) Gene Space Using Sequence Capture.” BMC Genomics 13: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1: ece371835‐sup‐0001‐SupinfoS1.zip.

Data Availability Statement

The samples used in this study are in compliance with national laws and the Nagoya Protocol and detailed information can be found in Supporting Information. Raw sequencing reads are accessible via BioProject “PRJNA1171613” (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1171613). The main bioinformatic steps and scripts are provided on our GitHub (https://github.com/Wielstra‐Lab/NewtCap_bioinformatics).