Abstract

Background

Ineffective dissemination of cancer research and information among the public contributes to cancer inequities. Dissemination rarely involves efforts to engage non-research audiences and end-users in developing effective messaging. Efforts to promote equity in clinical trial participation may benefit from marketing strategies traditionally applied in the business sector. Black Americans suffer the highest death rates from most cancers than any other race/ethnicity, yet only 5% of patients enrolled in cancer clinical trials are Black. Our team used a marketing strategy framework to create a culturally responsive public service announcement (PSA) video to increase awareness of clinical trials among Black audiences.

Methods

We partnered with a marketing recruitment firm and a marketing agency to conduct six focus groups (n = 54) with social support networks of Black cancer survivors and Black community members. Maximum variation sampling was used to recruit a national sample of eligible participants that varied in age, education, geographic region, and gender. Focus groups were conducted over three phases that informed script development, script and storyline testing, and sought feedback on the PSA video post-production. We used the Marketing and Clinical Trials Reference Model to guide marketing strategies, data collection, video content development and production. We used rapid qualitative data analysis techniques to identify themes for each phase to guide PSA development.

Results

Partnered with a film production company, we produced a 2-min PSA video that uses professional actors and storytelling and marketing techniques to describe clinical trials, provide relevant statistics, address barriers to participation expressed by participants, and provide credible resources to seek further information. We also produced 30 s and 60 s versions of the PSA to accommodate different marketing media outlets. Participants felt the videos were engaging and relatable and that the messaging was clear. The videos ignited meaningful discussions about clinical trial participation and motivated participants to share the information learned.

Conclusions

Using marketing communication strategies is a low-tech, pragmatic approach to effectively produce health information that is meaningful, can be tailored for specific audiences, and disseminated to broader audiences.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-24194-x.

Keywords: Dissemination, Clinical trials, Marketing, Communication, Cultural tailoring, Health information, Black Americans

Contributions to the literature

Dissemination of public health and cancer research is often passive and is often limited to academic methods of dissemination. Evidence-based dissemination strategies that are informed by and developed for public audiences and groups of focus may improve public knowledge and discourse of health information.

Our study demonstrates how marketing strategies may be an effective method to increase public awareness and knowledge about cancer clinical trials, particularly among underrepresented groups.

Our study provides a pragmatic approach to using marketing techniques and can be used to develop health communication tools that are low-cost and easily shared and accessed.

Background

Ineffective dissemination of cancer research, education, and interventions among the public contributes to cancer inequities [1, 2]. Efforts to disseminate public health research tend to be passive, housed behind paywalls, or are limited to academic methods of dissemination (e.g., professional journal publications, academic conferences, seminars, workshops) [1, 3, 4]. Moreover, dissemination rarely involves efforts to engage non-academic audiences, end-users, and the general public in developing effective messaging. This is especially problematic in the decision-making processes associated with clinical trial (CT) participation.

Inclusion of patients from racial/ethnic minority groups into cancer CTs is a major barrier to health equity. In 2022, a total of 3,516 patients participated in cancer CTs in the U.S. leading to approval of 10 novel therapeutics approved by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. However, only 3% of enrolled participants in these trials were Black [5]. Compounding the severity of this disparity, Black Americans make up 13.6% of the U.S. population [6], yet have the highest death rates and shortest survival rates of any racial/ethnic group for most cancers, and are more likely to be diagnosed at later stages [7]. Lack of representation of racial/ethnic minority groups in cancer CTs limits scientific innovation, exacerbates mistrust, compromises the generalizability of clinical research findings, and increases cancer inequities [8, 9].

Marketing communication strategies, typically employed in business settings, may be particularly effective in closing racial gaps in CT participation and promoting health equity. Dissemination of educational tools and marketing strategies are essentially absent from CT research, yet CTs require formal voluntary buy-in, participation, and commitment [10]. To address inefficiencies in cancer information dissemination and disproportionate underrepresentation of Black Americans in cancer CTs, our team developed a culturally responsive public service announcement (PSA) video to increase awareness of CTs among Black audiences using community-engaged approaches. We conducted market research using focus groups (FGs) with a broad audience of Black community members, cancer survivors, and family members of cancer survivors. FGs were facilitated by a professional marketing agency to create the PSA video designed to be easily disseminated using multiple platforms. FGs were used to develop the educational content, motivational messaging, and to guide creation of the narrative storyline. The purpose of this paper is to describe the development of the FOR US (Fostering Opportunities in Research Using marketing Strategies) PSA using a marketing framework and strategies.

Methods

Theoretical framework for the development of the FOR US PSA

IRB approval from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center was obtained for all research processes (RG1122736) on October 10, 2022 and we complied with the SQRQ reporting guidelines for qualitative research [11].

We adapted the Marketing and Clinical Trials Reference Model [10] (hereafter referred to as the Reference Model) to guide marketing strategies for the development of the FOR US PSA video. Adaptations to the original model focused on integrating community-engaged approaches with marketing strategies. The Reference Model describes requirements for successful marketing of a CT and consists of four marketing domains and 12 strategic components (Table 1). The Reference Model domains were used to inform FG data collection, video script and content development, and video production. The four domains and adapted components are:

Building brand values, which comprises a) integrating brand and cultural values by describing what a trial is and is not and acknowledging cultural attitudes and beliefs; b) gaining legitimacy and prestige by positively associating with prestigious or credible individuals and institutions to garner credibility; and c) signaling worthiness by cultivating buy-in through communicating potential benefits that will be delivered.

Product and market planning, which comprises a) providing simple, comprehensive processes by providing messaging that is easy to understand, b) devising strategies for overcoming resistance by identifying and addressing barriers to participation, and c) adopting an explicit marketing plan that identifies the target audience and specific marketing strategies for varying levels of buy-in.

Making the sale which comprises a) engaging active sponsors, champions, and change agents by garnering input and support from credible sources, b) employing tailoring strategies to ensure that messages and materials are distinctive to the needs of the target group, and c) achieving buy-in by disseminating information that is widely accessible.

Maintaining engagement which comprises a) building trust by providing accurate and truthful information, b) utilizing positive framing while maintaining transparency by clearly communicating the benefits, risks, and requirements related to CT participation, and c) normalizing messaging by increasing public knowledge about CTs through dissemination efforts that are available to the general public.

Table 1.

Adapted marketing and clinical trials reference model8

| Domain | Component | Example Development Focus Group Question | How Applied in Development & Script |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Building Brand Values |

• Integrate brand and cultural values by conveying what CTs intend to deliver to patients, providers, and medicine and incorporating cultural values in messaging • Gain legitimacy by understanding factors needed for credibility to support decision-making • Signal worthiness by examining factors that help target audiences realize and identify with potential benefits of a clinical trial |

• What are the important factors to highlight when recommending a clinical trial for Black cancer patients? • Are there key organizations or individuals whose involvement as a messaging partner would help build trust in CTs? |

• Clearly stated the purpose of clinical trial and directly acknowledged medical mistrust due to racism • Stated the importance of CTs while valuing autonomy in decision-making |

| 2. Product and Market Planning |

• Provide simple, complete, messaging that is easy to understand and tested by target audience • Devise strategies for overcoming resistance by understanding and barriers and offer strategies to address them • Adopt an explicit marketing plan that defines marketing strategies for audiences at varying levels of buy-in |

• What marketing strategies will most effectively alert Black cancer patients and the public to the existence and the benefits of the CTs? • What are the key questions that Black cancer survivors and Black Americans in the general public would have about a clinical trial? |

• Script used conversational tone • Acknowledged psychosocial barriers to participation and addressed them • Developed a 5-step dissemination & marketing plan |

| 3. Making the Sale |

• Engage active sponsors, champions, change agents to promote trust • Employ tailoring strategies to ensure messaging is culturally sensitive, responsive, and appropriate • Achieve buy-in through dissemination media that is widely and easily accessible |

• What type of information do you think is important for Black cancer patients to know about when deciding of whether to participate in clinical trial? • What media formats would be most appropriate to disseminate the targeted intervention through? |

• Used Black actors in PSA, one who represented a medical expert • Content developed and grounded with direct insight and feedback from representative target audience • PSA to be distributed using multiple media platforms that are easily accessible |

| 4. Maintaining Engagement |

• Build trust by providing accurate information from trustworthy sources • Utilize positive framing while maintaining transparency about multiple aspects of clinical trial participation • Normalize messaging and knowledge about CTs |

• What information about the results of CTs would be important to Black Americans in the general public to know? |

• Relayed importance of clinical trial participation while acknowledging barriers and negative perceptions • URL links provided cancer center, foundation, and government weblinks at end of video • Dissemination plan accessible to public and not housed behind paywalls |

Recruitment, data collection, and PSA development

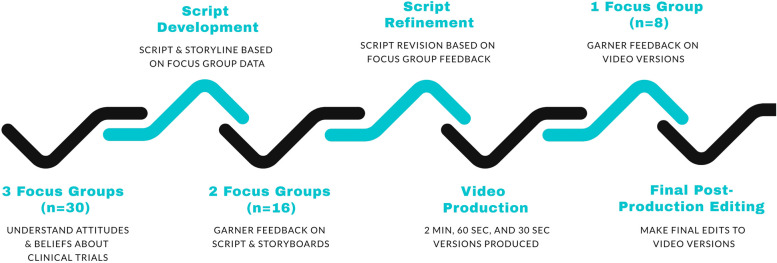

We engaged a professional recruitment firm specializing in recruitment for qualitative marketing and academic research and a marketing agency to conduct six FGs over three project phases between November 15, 2022 and July 19, 2023. Phase 1 FGs focused on understanding perceptions of CTs and informed the script development and PSA content, look, and tone. Phase 2 FGs focused on script testing and sought feedback on the PSA script and storyboard. Finally, a Phase 3 FG, which was conducted post-video production, tested different iterations of the PSA. The PSA video development process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PSA video development process

Individuals were eligible to participate if they were community members who identified as Black/African American and aged 18 years and older. For three FGs, an additional eligibility criterion was that participants were cancer survivors and/or household members of cancer survivors. Using maximum variation sampling to ensure that our PSA was relevant to Black audiences with different demographic considerations, the firm recruited, screened, provided a study information document, and collected non-disclosure agreements from a national sample of Black participants (n = 54) across the three phases of FGs who varied in age, geographic region, education, and gender (Table 2). All FGs were conducted by the marketing consultant using video conferencing software and semi-structured FG guides, that were co-developed by the marketing consultant and the research team. All FGs were recorded and averaged 60 min in length. A research team member was present for each focus group as a notetaker. Participants received a $100 incentive for their time. All research activities were approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Table 2.

All focus group demographic characteristics (n = 54)

| Demographic characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean | 45.6 |

| Range | 19–76 |

| Gender Identity | |

| Female | 27 (50.0) |

| Male | 27 (50.0) |

| Region | |

| East | 14 (25.9) |

| Midwest | 15 (27.8) |

| South | 13 (24.1) |

| West | 12 (22.2) |

| Rural | |

| Yes | 12 (22.2) |

| No | 42 (77.8) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 1 (1.9) |

| Completed high school or GED | 16 (29.6) |

| More than high school | 37 (68.5) |

| Participated in clinical trial | |

| Yes | 8 (14.8) |

| No | 46 (85.2) |

| Focus group stratification | |

| General population (mixed ages) | 42 (77.8) |

| Affected1 (mixed ages) | 12 (22.2) |

1Household member or caregiver of person diagnosed with cancer

Phase 1 clinical trial perceptions & script development

Phase 1 FGs (n = 3 FGs, n = 30 participants) informed the PSA content and script development. Focus group questions captured components of each domain of the Adapted Marketing and Clinical Trials Reference Model including beliefs, barriers, and motivating factors related to participation, CT awareness, desired messaging and images, marketing influencers/desired sources of information, and dissemination preferences (Table 2).

Phase 2 script testing

Phase 2 FGs (n = 2, 16 participants) sought feedback on the PSA script and storyboard. The first FG was conducted with Black individuals from the general population and the second FG was conducted with Black individuals who were personally diagnosed or lived with persons who were ever diagnosed with cancer (i.e., affected group). Focus group questions ascertained that the Reference Model component strategies were used for video content, dissemination plan, and our overall research approach. During FGs, participant volunteers role-played the script, which was also displayed on-screen, followed by FG questions and discussion.

Phase 3 video production and testing

We engaged a media production company to produce the video. During pre-production, we auditioned and secured actors and finalized shooting location and dates. During production, we filmed the video with directing input from the research team to ensure the script was delivered as intended. During post-production, multiple iterations of video and sound editing were conducted to produce 30 s, 60 s, and 2-min versions of the video.

Once completed, we conducted 1 online FG (n = 8 participants) to test each video time-version. Each version was played for participants, followed by discussion. Focus group questions captured general reactions, content expectations, views about content and tone, opinions about differences in versions and length considerations, and dissemination recommendations.

Data analysis

Data analysis procedures were similar across all three phases of the FGs. All FGs were recorded, professionally transcribed verbatim, and de-identified prior to analysis. Rapid qualitative data analysis [12, 13], which balances efficiency and rigor and is an appropriate approach when results are utilized to guide future data collection efforts.

This analysis was completed by marketing consultants, who also have expertise in qualitative data analysis, in collaboration with the research team. The research team reviewed all transcripts and analysis reports from the consultants and discussed findings thoroughly during weekly team meetings. Using a rapid thematic qualitative analysis methodology, analysts first read through the Phase 1 FG transcripts (n = 3) to identify patterns and major themes conveyed by participants. They used inductive analysis approaches to examine the patterns and themes in the FG data to understand participants perceptions around CTs. They also used deductive approaches to explore barriers and facilitators to CT participation based on existing knowledge of this topic. Deductive approaches were also used to identify PSA development recommendations about the storyline, character choices, setting, and script. Analysts then produced a summary report that included major themes and subthemes, PSA recommendations conveyed by participants, and exemplar quotes. This report was reviewed and discussed among analysts and research team members in a series of debrief meetings prior to drafting the PSA script. In collaboration with a professional screenwriter, we first drafted a creative brief to capture the general ideas for the PSA, then finalized a storyline and concept, and then produced the PSA script through multiple iterations of edits.

For the Phase 2 FG analysis, the analysts again used a rapid thematic qualitative analysis approach wherein they first read through the Phase 2 FG transcripts (n = 2) to identify patterns and major themes. Given that these findings would be used to refine the script and creative content prior to the PSA production, they used mostly deductive approaches to understand participants’ perceptions of authenticity regarding the PSA’s specific language, tone, and characters. Next, analysts produced a report that summarized findings, areas of agreement and disagreement among participants, key themes, recommendations for changes, and exemplar quotes. Finally, we refined the script and creative content based on these findings and prepared for the PSA production.

To complete the analysis of the Phase 3 FG (n = 1), conducted post PSA production, the analysts used the same methods employed in the Phase 1 and 2 FG analysis, with a focus on understanding how the participants perceived the PSA and its messaging, and to determine if there was an optimal length for the PSA. Again, analysts produced a report that summarized findings, areas of agreement and disagreement among participants, key themes, recommendations for changes, and exemplar quotes.

Results

Focus group results

Phase 1 CTs Perceptions and Script Development focus groups provided the basis of our script and storyline and resulted in five overarching themes:

Clinical trial mistrust due to experiences of racism persists but diminishes with younger respondents or those who had already participated in CTs. Participants believed in and wanted the scientific information, but they did not trust the sources of information or the health care system. They often referred to Black Americans being used as guinea pigs in research. They also wanted the PSA to acknowledge “the elephant in the room,” i.e., racism. Mistrust was less pronounced with younger participants and those who had already participated in a clinical trial.

Exemplar quote 1: “I just think that historically, the trust has been shattered. For us, no one’s ever had our best interests at heart. So, it’s just hard. Even though part of you [feels] scientifically, yes, you should probably be a part of this, there’s always going to be something in the back of our minds.”

-

2)

Clinical trial trust-building was associated with transparency from medical experts, hearing directly from CT participants, and information relayed by someone in the Black community. Participants felt that trust-building was facilitated by who is delivering the message, what they say, and how they say it. Participants expressed that concerns about trust can be addressed by providing factual information using sincere language delivered by credible and representative sources. They were more trusting of information from medical experts who conveyed not only the benefits, but also the risks associated with participating in a clinical trial. They also wanted to hear about personal experiences from individuals who had participated in CTs themselves. Most participants desired getting information from people in the Black community who could acknowledge and address concerns of the Black community and felt that representation was vitally important. Participants were not interested in seeing celebrities in the PSA.

Exemplar quote 2: “I would have to see [in the PSA] Black doctors, Black nurses, people that look like me. Representation matters.”

-

3)

Invasive procedures impact views on risks and benefits of participation. Participants were more amenable to participating in a CT if procedures were less invasive.

Exemplar quote 3: “It depends on what kind of clinical trial. I wouldn’t want to do like an injection, a clinical trial. But if it was something like trying out a topical cream or shampoo, or testing out new products…But as far as a clinical trial with anything injected into my body, no.”

-

4)

Messages that are not coercive, yet are transparent and support decision-making, are more credible. Participants valued reaching their own conclusions and decisions after having comprehensive information about a trial (benefits, risks, and potential side effects) and did not want to be coerced. They also desired the autonomy to do their own research with credible sources.

Exemplar quote 4: “I just feel like access to their [researchers] research and the good and the bad that’s happening due to the clinical trials would definitely be very beneficial to me and in a way, compel me to do the clinical trial on my own.”

-

5)

Sharing the PSA on social media with links to primary resources was recommended. Facebook and Instagram were commonly used and referenced social media platforms. Participants wanted exposure to the information through social media with links to reliable websites for more in-depth information.

Exemplar quote 5: “I learned so much from social media that I wasn’t even taught in grade school. Of course, you verify your sources and whatever links that are shared on that social media, but I’m definitely putting social media high on my list.”

After incorporating Phase 1 focus group findings and applying the Reference Model components to develop a script, storyline, and storyboards, we conducted focus groups to gather feedback on the script. The story depicted a father and daughter reminiscing about a relative who passed away from cancer. The father is currently diagnosed with cancer and was presented the option of a CT by his provider, but he expressed skeptism about participating. The daughter, a healthcare provider, used this as an opportunity to provide information to her father about CTs. At the end, the father decided to learn more about CTs. URL links to two cancer centers, a cancer-focused foundation, and clinicaltrials.gov were provided (permissions to publish URLs were acquired and granted from each organization). Overall, the storyline was well-received by all in both focus groups, with some stylistic feedback about the opening scene. Interestingly, focus group discussions extended beyond the script content and triggered meaningful conversations about beliefs and attitudes about CTs.

Phase 2 Script Testing focus groups also resulted in 5 overarching themes:

Participants felt the storyline and script were informative, culturally representative, realistic, and understandable.

Participants saw themselves in the characters and family dynamics.

The opening scene should be altered to avoid racial stereotypes.

The storyline elicited a desire to pursue additional information about CTs before deciding about participation.

The script triggered discussion about factors impacting low clinical trial participation and ineffective information dissemination to Black communities.

Exemplar quote 1: “It makes me want to look into CTs and maybe how I can spread the word or participate myself. [I feel] motivated, empowered. The more I know, the more you know.”

Exemplar quote 2: “I related those characters to people in my life that I know have really felt that way about clinical trials and medicine in general who lived during that time when it just was scary as a Black person to go into a medical facility.”

Exemplar quote 3: “So for me, it hits home because now I can, I didn’t have those conversations. My parents didn’t have those conversations with me, but I’m for surely gonna have those conversations with my daughter and hopefully that keeps going on from generation to generation so this can stop.”

Based on participant feedback, the script was refined, and we decided to produce a full 2-min version, a 60 s version and a 30 s version of the video for different media outlets and attention spans (e.g., participants stated that the longer video may be best shown on YouTube and shorter videos on TikTok or Instagram). Videos were tested in Phase 3. Overall, the videos received positive feedback and elicited the desired result, to motivate individuals to seek more information about CTs.

All video versions were shown in Phase 3 Video Testing focus groups. Five key themes were identified:

Participants felt the videos were relatable, believable, and the messaging was clear.

Participants voiced learning something new and felt the statistics provided were important.

Participants preferred the 2-min version of the video. The longer time duration was not considered an issue because the information was perceived as relevant, informative, engaging, and factual.

The tone for most participants hit the mark, except two participants felt the videos elicited feelings of guilt.

The videos did not change participants’ views about CTs in either direction, but it made all of them want to learn more about CTs and provoked meaningful conversation about CTs.

Exemplar quote 1: “I was trying to understand why I feel this way, I kind of felt guilty cuz I was like, hmm, do I need to talk to my family about this? Am I doing enough? That kind of kept coming up a little bit. Not as prevalent as the inquisitive feeling though.”

Exemplar quote 2: “I actually learned something – the stats really caught my ear…providing the website as a reference to find out more was really important.”

Exemplar quote 3: “It would make me wanna pursue things, ask more questions, get more information. It would start the conversation for sure — that uncomfortable conversation that a lot of people don’t want to have.”

During post-production, we decided to produce 2 versions of the 60 s video and 2 versions of the 30 s video. Versions differed in that one 30 and 60 s version were racially-tailored and provided statistics about clinical trial participation rates and barriers among Black Americans and the other version was not racially tailored (did not include statistics and cultural barriers) and could be applicable to any audience. Video playlists are publicly available for viewing and sharing [14, 15].

A summary of focus group themes is provided in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Focus group themes

Discussion

The challenge of ensuring equitable and diverse participation in CTs necessitates innovative approaches to recruitment strategies. Drawing upon the foundational principles of the Marketing and Clinical Trials Reference Model [10], our study was able to successfully recruit participants, elicit key themes, and develop a culturally-responsive PSA that reflected beliefs and attitudes about Black Americans’ participation in cancer CTs. While the concept of marketing has a questionable role in healthcare, marketing principles can help achieve organizational missions in cost-effective ways that minimize waste [16]. Clinical studies that have embraced marketing principles have effectively bridged the gap between clinical research and target communities, underscoring the significance of culturally tailored messaging and strategic dissemination of information. In the CRASH-2 trial [17], a large multinational trial of antifibrinolytic therapy in trauma patients, the Reference Model [10] was applied to overall trial management. By developing brand values, providing simple processes, engaging stakeholders, and achieving buy-in from the public, the trial was able to successfully recruit over 20,000 patients within 4 years. The Reference Model principles adapted by trials such as CRASH-2 have overlap with community-based research principles, such as engaging the community in defining and explaining the research problem to increase the relevance of the research question and interventions for the community of interest [18].

Barriers to equitable cancer clinical trial participation, particularly for Black Americans, are factors related to patients, providers, health systems, and CTs [19]. Our findings are consistent with previous qualitative research on Black Americans’ perception of CTs demonstrating historical abuses as a potential factor for lower enrollment, but noted perceptions shifting with younger generations [20]. Additionally, our findings also emphasize the importance of increased representation of Black physicians and members of the research team, as representation was felt to be vitally important. Notably, phase 1 focus group members stressed they were not receptive to messaging from celebrities and valued authenticity in messaging.

Despite conventional beliefs that Black Americans are less likely to agree to participate in trials, patient decision-making as the primary barrier to participation has been upended by recent studies showing Black and White patients agreed to participate in trials at similar rates when offered [21]. Structural barriers such as a lack of available trials where Black Americans receive care or exclusive eligibility criteria play a significant role in trial enrollment disparities. Findings from phase 1 focus groups of this study support autonomy in decision making around trials. Participants endorsed believing in the science and wanting to hear from medical experts and individuals who participated in CTs, but ultimately wanted to be able to come to their own conclusions and decisions without feeling coerced. Marketing strategies that aim to provide credible, trust-worthy information and sources, while respecting individual autonomy in decision-making may be most effective in increasing awareness and participation in CTs.

Our work builds upon previous research in the field by incorporating target audience feedback into the design, editing, and evaluation of the final PSA product. Story-based health promotion interventions are more effective than non-narrative approaches, especially in racial/ethnic minority communities [22–26] and dissemination of research to nonacademic and nonscientific audiences is more effective when messages elicit emotion, align with values, and demonstrate usefulness [1, 10]. Understanding sociocultural experiences, learning about the needs and values, and listening to the voices of target groups and communities increases authenticity, reflectiveness, and effectiveness of health communications. Our approach provides rich annotation of the data with life experiences of Black breast cancer patients, family members, and community members, incorporated into the script of the PSA to enhance authenticity.

Guidance and application of the domains and components from the Marketing and Clinical Trials Reference Model resulted in a PSA that resonated with and was highly acceptable by representatives from our groups of focus. Feedback from phase 2 and 3 focus groups demonstrated that the script and video themes were believable, representative, and action-provoking to seek out more information about CTs. The PSA incorporated statistics related to clinical trial participation rates among Black Americans which left participants feeling empowered to disseminate this information in their own communities, a perception seen in prior studies [20]. Having feedback on the script through phase 2 focus groups led us to alter the opening scene to culturally tailor the PSA in a manner that was representative, meaningful, and respectful of cultural values. Upon final production of the PSA, feedback from the phase 3 focus group was largely positive and participants felt the messaging was believable and provoked meaningful dialogue about clinical trial decision making.

The production cost for the full version of the video was $35,000, which included production staffing (director, production coordinator, photography director, audio engineer, two camera operators, hair and make-up artist), professional talent auditions and payment, location costs, voice-over talent, music licensing, and post-production editing. In general, video production costs vary based upon several factors (e.g., production quality, use of professional talent and production company, number of cameras used, use of animation, etc.) and can range from no costs (e.g., video shot on smart phone) on upwards. Future work will evaluate the efficacy of low/no cost video production versus higher cost professional video production on viewer acceptability and behavior change.

Our next steps are to implement a 5-step Marketing and Dissemination Plan developed by our marketing consultant. Currently, we are piloting the video with a sample of Black cancer patients to assess the impact of the FOR US PSA on trust in information, knowledge about CTs, and decision-making self-efficacy among Black patients diagnosed with cancer and determine the acceptability of the intervention.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated a pragmatic approach to using marketing communication techniques to create a low-tech solution to disseminating health information that can be easily shared, accessed, and adapted using multiple media platforms. These techniques resulted in an educational tool that can be used in clinical and community settings, and can be tailored for specific groups. Utilizing marketing strategies to increase awareness and facilitate decision-making about cancer CTs offers the opportunity to tailor messaging to specific audiences, garner feedback about attitudes and beliefs from end-users to create meaningful, applicable, creative, and informational content, and disseminate health information to broader audiences.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our marketing partners, SolidLine Media, Blockbeta Marketing, and Focus Insite, for their support with this project. We would also like to thank the V Foundation for Cancer Research, Andy Hill CARE Fund, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, and University of Illinois Chicago for funding this research.

Abbreviations

- CT

Clinical trial

- FG

Focus group

- PSA

Public service announcement

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: VH, LC, RN, KH; JS; Methodology: VH, LC, RN, KH, RB; Analysis & Interpretation: RB, MK, VH, LC, EC; Writing – Original Draft: VH, LC, RN; Writing – Review & Editing: VH, LC, RN, KH, AW, KS, EC, RB, MK, TG, JS; Visualization: VH; Project Administration: AW, KS; Funding Acquisition: VH, KH, RN, LC.

Funding

This research was supported through funding from the V Foundation for Cancer Research and supplemental support from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and the University of Illinois Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval to conduct this human subjects research was obtained by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center institutional review board on October 10, 2022 (RG1122736). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for participating in the study and a waiver of documentation of informed consent was approved by the IRB.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brownson RC, Eyler AA, Harris JK, Moore JB, Tabak RG. Getting the word out: new approaches for disseminating public health science. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(2):102–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milkman KL, Berger J. The science of sharing and the sharing of science. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):13642–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brownson RC, Jacobs JA, Tabak RG, Hoehner CM, Stamatakis KA. Designing for dissemination among public health researchers: findings from a national survey in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1693–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabak RG, Stamatakis KA, Jacobs JA, Brownson RC. What predicts dissemination efforts among public health researchers in the United States? Public Health Rep. 2014;129(4):361–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Drug trials snapshots summary report 2022. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2022. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/drug-trials-snapshots.

- 6.U.S. Census Bureau. Quick facts United States population estimates 2023 [updated July 1, 2023. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/.

- 7.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures for African American/Black people 2022–2024. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2022. 10.17226/26479. [PubMed]

- 9.Bierer BE, White SA, Meloney LG, Ahmed HR, Strauss DH, Clark LT. Achieving diversity, inclusion, and equity in clinical research. Cambridge and Boston, MA: Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard (MRCT Center). 2020. Available from: https://mrctcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Bierer-Diversity-McKinsey-RD-5-Nov-2020-min.pdf.

- 10.Francis D, Roberts I, Elbourne DR, Shakur H, Knight RC, Garcia J, et al. Marketing and clinical trials: a case study. Trials. 2007;8(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nevedal AL, Reardon CM, OpraWiderquist MA, Jackson GL, Cutrona SL, White BS, et al. Rapid versus traditional qualitative analysis using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implement Sci. 2021;16(1): 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gale RC, Wu J, Erhardt T, Bounthavong M, Reardon CM, Damschroder LJ, et al. Comparison of rapid vs in-depth qualitative analytic methods from a process evaluation of academic detailing in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1): 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.FOR US Video Playlist, Fred Hutch tagline 2024. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLqNTTfHY8wLwbNF8q0yGkrihImYFnPjfS.

- 15.FOR US Video Playlist, University of Illinois Chicago tagline 2024. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLqNTTfHY8wLwbNF8q0yGkrihImYFnPjfS.

- 16.Mitchell EJ, Sprange K, Treweek S, Nixon E. Value and engagement: what can clinical trials learn from techniques used in not-for-profit marketing? Trials. 2022;23(1):457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald AM, Treweek S, Shakur H, Free C, Knight R, Speed C, et al. Using a business model approach and marketing techniques for recruitment to clinical trials. Trials. 2011;12:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hébert JR, Braun KL, Meade CD, Bloom J, Kobetz E. Community-based participatory research adds value to the National Cancer Institute’s research portfolio. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015;9 Suppl(1):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Awidi M, Al HS. Participation of Black Americans in cancer clinical trials: current challenges and proposed solutions. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(5):265–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riggan KA, Rousseau A, Halyard M, James SE, Kelly M, Phillips D, et al. “There’s not enough studies”: views of black breast and ovarian cancer patients on research participation. Cancer Med. 2023;12(7):8767–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schell SF, Luke DA, Schooley MW, Elliott MB, Herbers SH, Mueller NB, et al. Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perrier M-J, Martin Ginis KA. Changing health-promoting behaviours through narrative interventions: a systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2018;23(11):1499–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borrayo EA, Rosales M, Gonzalez P. Entertainment-education narrative versus nonnarrative interventions to educate and motivate Latinas to engage in mammography screening. Health Educ Behav. 2017;44(3):394–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee H, Fawcett J, DeMarco R. Storytelling/narrative theory to address health communication with minority populations. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30:58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreuter MW, Green MC, Cappella JN, Slater MD, Wise ME, Storey D, et al. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(3):221–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreuter MW, Holmes K, Alcaraz K, Kalesan B, Rath S, Richert M, et al. Comparing narrative and informational videos to increase mammography in low-income African American women. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:S6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.