Abstract

Introduction

In recent years, programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy was found to have favorable clinical outcomes in patients with extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC). The usefulness of early tumor shrinkage (ETS) has been reported in various types of cancers. Nevertheless, there have been few reports evaluating ETS in ES-SCLC. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the role of ETS in the clinical outcomes of patients with ES-SCLC receiving chemoimmunotherapy.

Methods

We prospectively identified 46 patients with ES-SCLC who received PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy at 10 institutions in Japan between September 2019 and October 2021. Of them, 35 patients were selected for analyses.

Results

The responders (progression-free survival [PFS] ≥ 6.0 mo) had significantly greater tumor shrinkage at the first evaluation than the nonresponders (PFS < 6.0 mo) (65.0% versus 53.7%, p = 0.03). We defined the cutoff value for ETS as a 57% change from the baseline on the basis of the receiver operating characteristic results to determine the optimal tumor shrinkage rate at the first evaluation for identifying responders. The patients with ES-SCLC who achieved ETS had longer PFS and overall survival than those who did not achieve ETS (5.6 versus 4.0 mo, log-rank test p = 0.001 and 15.0 versus 8.3 mo, log-rank test p = 0.02). In the multivariate analyses, ETS was significantly associated with PFS and overall survival (hazard ratio = 0.27, 95% confidence interval: 0.12–0.63, p = 0.002 and hazard ratio = 0.34, 95% confidence interval: 0.13–0.85, p = 0.02).

Conclusions

Our prospective observational study indicated that ETS was related to favorable clinical outcomes for patients with ES-SCLC receiving PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy.

Keywords: Extensive-stage-small cell lung cancer, PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy, Early tumor shrinkage, Objective response

Introduction

SCLC accounts for 15% of all lung cancer cases. The prognosis of extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC) is especially poor, accounting for approximately 70% of SCLC cases.1,2 The standard treatment for ES-SCLC has been cytotoxic chemotherapy in the past three decades.3 Recently, programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy was found to have better progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than platinum-etoposide chemotherapy.4, 5, 6

In advanced NSCLC, early tumor shrinkage (ETS) has been strongly correlated with PFS after treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors.7 Nevertheless, no previous studies have evaluated the relationship between ETS and the treatment efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy for patients with ES-SCLC in the real-world setting.

In this multicenter prospective study, we investigated the role of ETS on clinical outcomes in patients with ES-SCLC who received PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We prospectively enrolled patients diagnosed with having ES-SCLC who received PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy at 10 different institutions in Japan between September 2019 and October 2021. The inclusion criteria of this study were as follows: (1) patients aged 20 years or older; (2) patients with untreated advanced SCLC, with a pathologic diagnosis of SCLC confirmed by investigating the tumor tissue specimen; (3) patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 to 2; and (4) patients with assessable lesions on the basis of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines (version 1.1). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who were deemed inappropriate by the physician in charge of the study; (2) patients for whom evaluation using residual specimens after pathologic diagnosis was impossible; (3) patients who discontinued the treatment owing to adverse events (AEs); and (4) patients who did not receive the first evaluation at 6 to 10 weeks by computed tomography (CT) scans. The recommended course of chemotherapy was four courses on the basis of pivotal clinical trials.4, 5, 6

Because the median PFS period of PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide therapy in pivotal studies was approximately 5 to 6 months, we defined responders as those achieving PFS more than or equal to 6 months.4, 5, 6 On the basis of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, the optimal cutoff value for tumor shrinkage at the first evaluation to predict the responders was identified, and responders who achieved greater shrinkage were considered to have achieved ETS. Tumor shrinkage was calculated on the basis of RECIST guidelines (version 1.1). These assessments were carefully performed by an unblinded attending physician. The data cutoff date was August 31, 2022. The median follow-up time for the censored cases was 16.6 months. We prospectively reviewed each patient’s medical record and collected the following data: age, sex, ECOG PS, smoking status, AEs, treatment regimens, height, weight, tumor shrinkage at the first evaluation, maximum tumor shrinkage at baseline, objective response, PFS, and OS. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013), and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (ERB-C-1580) and each participating hospital and was registered at the University Medical Hospital Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000044048). All patients provided written informed consent before their participation in this prospective study. In addition, we provided informed consent from each hospital from trial initiation.

Efficacy Analysis

PFS was defined as the time from the start of PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy to the date of disease progression or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time from the first administration of PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy to death from any cause. All patients underwent conventional procedures, such as CT and magnetic resonance imaging, according to the RECIST version 1.1. Assessment of treatment efficacy using CT scans was performed every 6 to 12 weeks.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical tests were two sided, and statistical significance was set at p value less than 0.05. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze categorical variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the change in tumor size from baseline and age between responders and nonresponders. The ability of optimal tumor shrinkage at the first evaluation to predict responders was determined using ROC curve analysis. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences were compared using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used in the univariate and multivariate analyses to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). On the basis of pivotal studies, sex, age (≥70 y), ECOG PS (PS = 2), brain metastasis, and ETS were selected as covariates.4, 5, 6 The cutoff value for body mass index was determined according to a previous study.8 Statistical analyses were performed using EZR statistical software version 1.54.9

Results

Patient Characteristics With ES- SCLC

We enrolled 46 patients with ES-SCLC who received PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy at 10 different institutions in Japan. There were 11 patients excluded from the analysis because of the following reasons: seven patients discontinued treatment owing to AEs, one patient had received chemoradiotherapy, one patient had missing data, and two patients did not receive early evaluation (Fig. 1). Finally, we analyzed 35 patients in this study. There were 30 patients who received up to four courses of chemotherapy. Unfortunately, four patients could not complete the full four courses owing to disease progression. One patient developed pneumonitis after three courses of induction therapy and was treated with steroids. After the steroids were tapered, the patient received maintenance therapy with atezolizumab without receiving a fourth course of induction therapy.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of this study. ES-SCLC, extensive-stage SCLC; CRT, chemoradiotherapy.

The median age of the patients was 71.0 (range: 50–86) years, and 28 (80.0%) patients were male. There were 31 (88.6%) patients who had a PS of 0 or 1 and four patients (11.4%) who had a PS of 2. In addition, 26 patients (74.3%) received carboplatin, etoposide, and atezolizumab (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics | All Patients (N = 35) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median (range) | 71.0 (50–86) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 28 (80.0) |

| Female | 7 (20.0) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0 or 1 | 31 (88.6) |

| 2 | 4 (11.4) |

| Smoking status | |

| Current or former | 35 (100) |

| Stage | |

| Stage Ⅲ or Ⅳ | 34 (97.1) |

| Postoperative recurrence | 1 (2.9) |

| Regimen | |

| Carboplatin + etoposide + atezolizumab | 26 (74.3) |

| Platinum + etoposide + durvalumab | 9 (25.7) |

| Metastatic sites | |

| Brain | 6 (17.1) |

| Liver | 15 (42.9) |

Note: All values are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

Treatment Efficacy

The overall response rate in patients with ES-SCLC treated with PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy was 82.9%. The percentages of patients who achieved stable and progressive diseases were 11.4% and 5.7%, respectively. The median tumor shrinkage at the first evaluation and maximum tumor shrinkage from baseline were 57.0% and 59.0%, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The median PFS and OS periods were 4.8 (95% CI: 4.3–5.3) and 13.2 (95% CI: 8.3–19.4) months, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1A and B).

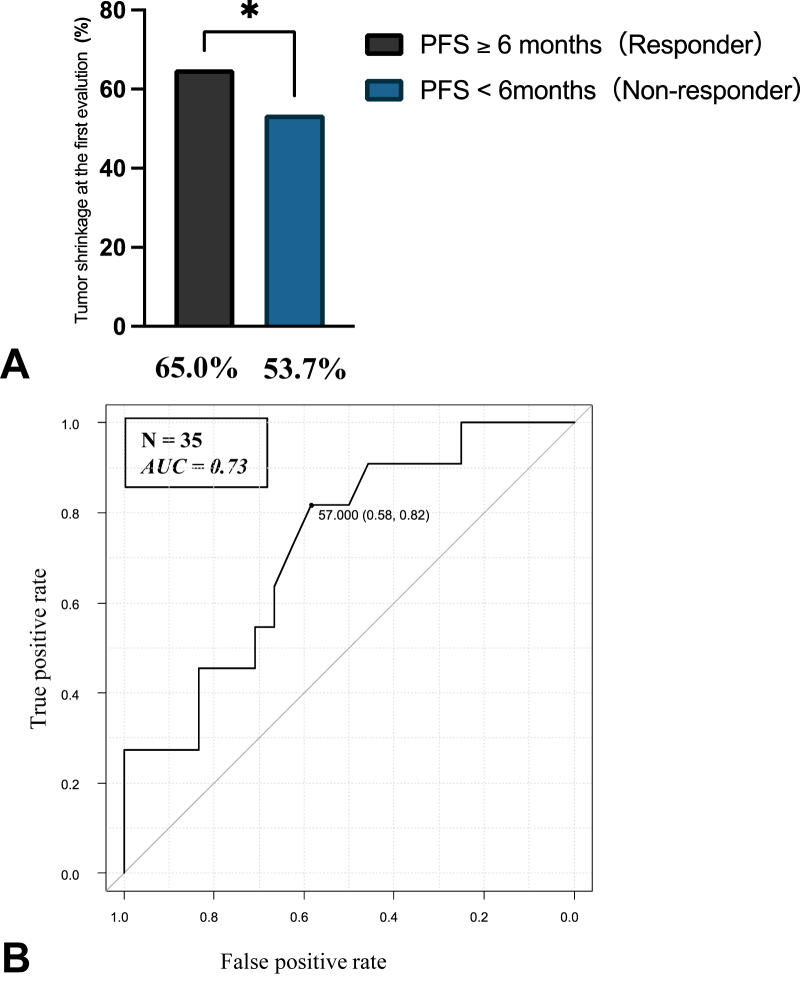

To evaluate the association between the tumor shrinkage at the first evaluation and treatment outcomes, we compared the characteristics between the responders and nonresponders. There was no significant difference in the characteristics of patients with ES-SCLC between the responders and nonresponders (Supplementary Table 2). The responders had significantly higher tumor shrinkage at the first evaluation than the nonresponders (65.0% versus 53.7%, p = 0.03) (Fig. 2A). The result of ROC curve analysis was used to determine the optimal cutoff value for the tumor shrinkage rate at the first evaluation to predict the responders (Fig. 2B). The area under the ROC curve was 0.73, and the optimal cutoff value for depth of shrinkage was 57.0%, which yielded a false-positive rate of 0.58 and a true-positive rate of 0.82. On the basis of these results, we defined the cutoff value for ETS as a 57% change from the baseline. The patients with ES-SCLC who achieved ETS had longer PFS and OS than those who did not achieve ETS (5.6 versus 4.0 mo, log-rank test p = 0.001 and 15.0 versus 8.3 mo, log-rank test p = 0.02) (Fig. 3A and B). Furthermore, we investigated 30 patients who received four courses of induction chemotherapy to evaluate the effects of ETS on patients with adequate induction therapies. The patients who achieved ETS (n = 17) had longer PFS and OS than those who did not achieve ETS (n = 13) (6.2 versus 4.5 mo, log-rank test p = 0.003 and 15.0 versus 8.4 mo, log-rank test p = 0.04) (Fig. 3C and D). The results of the Cox proportional hazards models for PFS and OS in patients with ES-SCLC who received chemoimmunotherapy are found in Table 2. In multivariate analyses, ETS was significantly associated with PFS and OS (HR, 0.27; 95% CI: 0.12–0.63; p = 0.002 and HR, 0.34; 95% CI: 0.13–0.85; p = 0.02, respectively). We also investigated clinical outcomes on the basis of RECIST criteria. The patients who achieved RECIST-based response (n = 29) had longer PFS compared with those who did not achieve response (n = 6) (5.1 versus 3.4 mo, log-rank test p = 0.03) (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Nevertheless, there was no significant difference in the OS between the patients who achieved RECIST-based response (n = 29) and those who did not (n = 6) (13.8 versus 10.8 mo, log-rank test p = 0.38) (Supplementary Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Association between PFS and the tumor shrinkage at the first evaluation. (B) Receiver operation to determine the optimal cutoff value for tumor shrinkage rate at the first evaluation to predict the responder. AUC, area under the curve; PFS, progression-free survival.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for (A) PFS compared with ETS (with ETS versus without ETS), (B) OS compared with ETS (with ETS versus without ETS), (C) PFS of patients who received four courses of induction chemotherapy (with ETS versus without ETS), (D) OS of patients who received four courses of induction chemotherapy (with ETS versus without ETS). PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI: confidence interval; ETS, early tumor shrinkage.

Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazard Models for PFS and OS in Patients With Extensive-Stage SCLC Who Received PD-L1 Inhibitor Plus Platinum-Etoposide Chemotherapy. Univariate and Multivariate Analyses

| Items | PFS (Univariate analysis) |

PFS (Multivariate analysis) |

OS (Univariate analysis) |

OS (Multivariate analysis) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Male | 0.76 (0.32–1.78) | 0.52 | 0.97 (0.38–2.47) | 0.94 | 0.76 (0.28–2.1) | 0.59 | 0.76 (0.24–2.4) | 0.64 |

| Age, y ≥70 | 1.55 (0.76–3.2) | 0.22 | 1.42 (0.67–3.0) | 0.36 | 1.2 (0.5–2.8) | 0.7 | 1.2 (0.48–3.02) | 0.7 |

| ECOG PS = 2a | 1.43 (0.5–4.1) | 0.5 | 2.1 (0.65–6.8) | 0.22 | 4.1 (1.3–13.0) | 0.02 | 5.4 (1.5–19.3) | 0.009 |

| Brain metastasis | 1.15 (0.47–2.8) | 0.76 | 1.1 (0.4–3.0) | 0.86 | 2.0 (0.77–5.1) | 0.16 | 1.6 (0.57–4.5) | 0.38 |

| Liver metastasis | 1.8 (0.9–3.6) | 0.1 | - | - | 1.4 (0.63–3.2) | 0.4 | - | - |

| Durvalumab regimenb | 0.63 (0.3–1.37) | 0.24 | - | - | 0.79 (0.3–2.1) | 0.64 | - | - |

| BMI > 25 | 0.8 (0.36–1.78) | 0.6 | - | - | 1.0 (0.37–2.7) | 1.0 | - | - |

| ETS (≥57%) | 0.28 (0.13–0.61) | 0.001 | 0.27 (0.12–0.63) | 0.002 | 0.37 (0.16–0.87) | 0.02 | 0.34 (0.13–0.85) | 0.02 |

PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; BMI, body mass index; ETS, early tumor shrinkage; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

ECOG PS = 2 versus ECOG PS 0 or 1.

Durvalumab regimen: platinum + etoposide + durvalumab versus atezolizumab regimen: platinum + etoposide + atezolizumab.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective real-world study to reveal that ETS in patients with ES-SCLC who received chemoimmunotherapy was associated with clinical outcomes. Patients with ES-SCLC who achieved ETS had longer PFS than those who did not. Furthermore, OS was longer in patients with ES-SCLC who achieved ETS than those who did not. Nevertheless, response based on the RECIST criteria did not improve OS. In clinical trials, tumor response based on the RECIST criteria is defined as at least a 30% reduction in the tumor size; however, this definition does not consider the timing of the response. ETS could be available earlier after the initial treatment and could predict long-term outcomes in patients with ES-SCLC who received PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy.

We identified an ETS value of 57% as the optimal cutoff value for predicting the long-term response to PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy in patients with ES-SCLC. This cutoff value was higher than those of previous reports of various malignancies treated with chemotherapy using a range of ETS cutoff values (10%–30%) to determine the predictors of PFS and OS.10,11 In general, SCLC tumors are highly sensitive to chemotherapy and have a high rate of tumor shrinkage.12 In a pivotal study of patients with ES-SCLC treated with chemoimmunotherapy, the maximum tumor shrinkage was approximately 60%, which is similar to the high tumor shrinkage observed in our study.6 These observations support a high cutoff value for ETS in patients with SCLC.

In a pivotal study, the addition of a PD-L1 inhibitor to chemotherapy has been reported to enhance tumor shrinkage in patients with ES-SCLC.6 Therefore, the choice of PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy in the first-line setting potentially increased the tumor shrinkage rate, leading to better clinical outcomes for patients with ES-SCLC.

Our study has some limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small. Second, only Japanese patients with ES-SCLC were included in this study; therefore, further large-scale investigations with a broader patient population are required to validate our findings.

Finally, we should consider the selection bias owing to study exclusion criteria, such as patients who discontinued treatment owing to AEs and those considered ineligible by the investigator.

In conclusion, our prospective observational study reveals that ETS correlates with treatment efficacy in patients with ES-SCLC treated with a PD-L1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy. Patients with ES-SCLC who achieved ETS have favorable clinical outcomes.

CRediT Author Contribution Statement

Masaki Ishida, Kenji Morimoto, Tadaaki Yamada: Study conception and design.

Masaki Ishida, Kenji Morimoto, Takayuki Takeda, Shinsuke Shiotsu, Koji Date, Taishi Harada, Nobuyo Tamiya, Yusuke Chihara, Yoshizumi Takemura, Takahiro Yamada, Hibiki Kanda: Obtained the clinical data.

Masaki Ishida, Kenji Morimoto, Tadaaki Yamada, Masahiro Iwasaku, Shinsaku Tokuda, Young Hak Kim, Koichi Takayama: Data interpretation.

Masaki Ishida, Kenji Morimoto, Tadaaki Yamada, Koichi Takayama: Manuscript preparation.

Ethics Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the institutional review board in Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (ERB-C-1580) and those of each respective hospital and registered at the University Medical Hospital Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000044048). Opt-out informed consent was provided at each hospital where the trial was conducted. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, their families, and all the investigators involved in this study. In addition, we thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for their help with the English language editing. The final version of the manuscript was read and approved by all the authors.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Tadaaki Yamada received grants from Pfizer, Ono Pharmaceutical, Janssen Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical, and personal fees from Eli Lilly. Takayama received grants from Chugai Pharmaceutical and Ono Pharmaceutical, and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi Sankyo, Japan. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Cite this article as: Ishida M, Morimoto K, Yamada T, et al. Early tumor shrinkage as a predictor of favorable treatment outcomes in patients with extensive-stage SCLC who received programmed cell death-ligand 1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy: a prospective observational study. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2023;4:100493.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the JTO Clinical and Research Reports at www.jtocrr.org and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtocrr.2023.100493.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Gazdar A.F., Bunn P.A., Minna J.D. Small-cell lung cancer: what we know, what we need to know and the path forward. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:725–737. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farago A.F., Keane F.K. Current standards for clinical management of small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7:69–79. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2018.01.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazzari C., Mirabile A., Bulotta A., et al. History of extensive disease small cell lung cancer treatment: time to raise the bar? A review of the literature. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:998. doi: 10.3390/cancers13050998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horn L., Mansfield A.S., Szczęsna A., et al. IMpower133 study group. First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2220–2229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu S.V., Reck M., Mansfield A.S., et al. Updated overall survival and PD-L1 subgroup analysis of patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer treated with atezolizumab, carboplatin, and etoposide (IMpower133) J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:619–630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paz-Ares L., Dvorkin M., Chen Y., et al. CASPIAN investigators. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394:1929–1939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawachi H., Fujimoto D., Morimoto T., et al. Early depth of tumor shrinkage and treatment outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer treated using nivolumab. Investig New Drugs. 2019;37:1257–1265. doi: 10.1007/s10637-019-00770-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortellini A., Bersanelli M., Buti S., et al. A multicenter study of body mass index in cancer patients treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors: when overweight becomes favorable. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:57. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0527-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cremolini C., Loupakis F., Antoniotti C., et al. Early tumor shrinkage and depth of response predict long-term outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with first-line chemotherapy plus bevacizumab: results from phase III TRIBE trial by the Gruppo Oncologico del Nord Ovest. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1188–1194. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinemann V., Modest D., Von Weikersthal L.F., et al. Independent radiological evaluation of objective response early tumor shrinkage, and depth of response in FIRE-3 (AIO KRK-0306) in the final Ras evaluable population. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:ii117. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demedts I.K., Vermaelen K.Y., van Meerbeeck J.P. Treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung carcinoma: current status and future prospects. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:202–215. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00105009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.