Abstract

Purpose

Neutrophil gelatin lipase carrier protein (NGAL) has been used as an early biomarker to predict acute kidney injury (AKI). However, the predictive value of NGAL in urine and blood in children with acute kidney injury in different backgrounds remains unclear. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to explore the clinical value of NGAL in predicting AKI in children.

Methods

Computerized databases were searched for relevant the studies published through August 4th, 2022, which included PUBMED, EMBASE, COCHRANE and Web of science. The risk of bias of the original included studies was assessed by using the Quality Assessment of Studies for Diagnostic Accuracy (QUADA-2). At the same time, subgroup analysis of these data was carried out.

Results

Fifty-three studies were included in this meta-analysis, involving 5,049 patients, 1,861 of whom were AKI patients. The sensitivity and specificity of blood NGAL for predicting AKI were 0.79 (95% CI: 0.69–0.86) and 0.85 (95% CI: 0.75–0.91), respectively, and SROC was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.86–0.91). The sensitivity and specificity of urine NGAL for predicting AKI were 0.83 (95% CI: 0.78–0.87) and 0.81 (95% CI: 0.77–0.85), respectively, and SROC was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.86–0.91). Meanwhile, the sensitivity and specificity of overall NGAL (urine and blood NGAL) for predicting AKI in children were 0.82 (95% CI: 0.77–0.86) and 0.82 (95% CI: 0.78–0.86), respectively, and SROC was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.86–0.91).

Conclusion

NGAL is a valuable predictor for AKI in children under different backgrounds. There is no significant difference in the prediction accuracy between urine NGAL and blood NGAL, and there is also no significant difference in different measurement methods of NGAL. Hence, NGAL is a non-invasive option in clinical practice. Based on the current evidence, the accuracy of NGAL measurement is the best at 2 h after cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and 24 h after birth in asphyxiated newborns.

Systematic Review Registration

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier: CRD42022360157.

Keywords: predictive value, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, children, acute kidney injury, meta-analysis

1. Background

At present, acute kidney injury is a great challenge for both adults and children in clinical practice, which occur more frequently in patients with cardiac surgery or in critically-ill children (1, 2). AKI affects almost 20%–50% of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care units (3, 4). However, there has been no recognized unified tool for the early prediction of AKI up to now, and many researchers have introduced machine learning into the field (5–7). Machine learning and single-factor prediction can complement each other. Efficient predictors are the key to improving the accuracy of machine learning predictions. However, for a single predictor, the accuracy of AKI diagnosis can be combined with other factors by using machine learning. Thus, improvement requires the combination of various effective predictors. Several studies have explored various predictors of AKI, including kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) (8), liver lipase-binding protein (L-FABP) (8, 9), NGAL (10, 11), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 (TIMP-2) and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) (12–14), etc.

Recent studies have found that NGAL seems to have good predictive ability for AKI, but its predictive ability for AKI in children in different backgrounds is still unclear, and there is no evidence-based evidence to explore whether it is derived from blood or urine. To evaluate the accuracy of NGAL in predicting AKI occurrence in different backgrounds, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis and aimed to provide a reference for the development or update of assessment tools for AKI in children in clinical practice.

2. Methods

The systematic review was implemented strictly according to PRISMA-2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) and prospectively registered on PROSPER (ID: CRD42022360157).

2.1. Literature search strategies

We systematically searched Pubmed, Cochrane, Embase, and Web of Science databases for relevant studies published between 2005 and 2022. The age of participants ranged from 0 to 18. The search strategy adopted the combination of subject headings and free words. No restrictions were imposed on regions or languages. The detailed searching strategies are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Studies including pediatric patients with complete records about NGAL;

-

2.

Studies including high levels of NGAL without limitation to the obvious cutoff value;

-

3.

Studies whose original types were RCTs, cohort studies, or case-control studies.

2.2.2. Exclusion criteria

-

1.

When it was not possible to distinguish whether NGAL was present in children or adults in a study, we considered excluding the study;

-

2.

If a study had a large number of missing values about NGAL, and the missing values were not effectively processed, the study was excluded;

-

3.

One of the following outcome indicators cannot be extracted directly or indirectly: sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic four-table, OR value.

2.3. Study selection and data extraction

The retrieved studies were imported into EndNote, and the titles and abstracts were screened to include the initial studies that met the inclusion criteria. After downloading and reviewing the full text of all potentially eligible studies, we included the eligible studies against the same eligibility criteria in our systematic review. We developed a standard data extraction spreadsheet before data extraction. Extraction content included the title, the first author's name, publication year, study type, NGAL source and measurement methods, AKI occurrence backgrounds and time, NGAL optimal cut-off threshold, the number of patients with AKI and the total number of study cases, sensitivity and specificity. The above literature screening and data extraction were independently carried out by two investigators (ZZ and CB) and cross-checked after completion. Any disagreements would be resolved by a third investigator (X-DQ).

2.4. Quality assessment

The quality and risks of bias of the initially included studies were assessed by two researchers independently (ZZ and CB) with the help of the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool (15). This tool consists of four key domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, flow and timing. The risks of bias in all studies were assessed according to these four domains and the applicability concerns were evaluated according to the former three: these areas were marked as the following responses: “Yes”, “No” or “Unclear”. For the evaluation of the risk of bias, if all of the questions in a domain were marked with “Yes” responses, the domain would be ranked as a low risk of bias. Any questions in a domain marked with “No” responses suggested a high risk of bias.

2.5. Statistical analysis

We conducted a meta-analysis in which a bivariate mixed effects model in the “Midas” command of Stata 15.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) was used to assess sensitivity (SEN), specificity (SEP), positive likelihood ratio (PLR), negative likelihood ratio (NLR), and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR). We calculated the point estimates with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). A summary receiver operating characteristic curve (SROC) was drawn and the area under the curve (AUC) at 95% CI was calculated. Deek's funnel plot was used to evaluate the publication bias, and the Q statistic and I2 statistic were used to test for heterogeneity. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Literature screening results

Overall, 1,298 relevant studies were retrieved from the database, of which 556 duplicates were excluded. After screening the titles and abstracts of the remaining 742 studies, 665 studies were excluded. After screening the full text, 24 studies were excluded and 53 met the eligibility criteria (10, 11, 16–65). The flowchart of the literature screening method is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature screening. AKI acute kidney injury, area under the AUC curve, NGAL neutrophil gelatin release-associated lipoprotein.

3.2. Study characteristics

Of the 53 included studies published between 2005 and 2022, which included 5,048 patients, 1,861 patients had AKI, with an incidence rate of 36.8%. Among them, 34 studies (10, 11, 16–18, 20–22, 24, 27–29, 31–34, 39, 42–45, 47, 48, 52, 53, 55–58, 61–65) measured urine NGAL, 14 studies (24, 26, 30, 36–38, 41, 46, 49–51, 54, 59, 60) measured blood NGAL, and 5 studies (19, 25, 35, 40, 42) measured blood and urine simultaneously. The included studies were conducted in 20 countries worldwide, including 11 studies in European countries (19, 20, 30, 33–36, 38, 54, 58, 65), 12 studies in the United States (10, 11, 32, 40, 42, 45, 49, 50, 53, 61, 62, 66), 20 studies in Asian countries (16, 18, 22, 24, 25, 27–29, 31, 33, 39, 41, 43, 44, 48, 51, 52, 55, 56, 59), 9 studies in African countries (24, 37, 46, 47, 49, 57, 60, 63, 64), and 1 study from Canada (17). Two studies were multi-centered (26, 33), and the remaining studies were single-centered. The included studies covered various backgrounds of AKI. Among them, 15 studies reported AKI occurred after CPB surgery (11, 19, 21, 24, 33, 36, 40, 42, 46, 50, 53, 56, 58, 65, 66), 12 studies reported AKI occurred in asphyxiated neonates (22, 28, 30, 31, 35, 37–39, 47, 51, 54, 57), and the remaining 26 studies reported AKI occurred in children hospitalized for a variety of diseases, including sepsis, burns, solid tumors, post-liver transplantation, nephrotoxic drug use, imaging, and preterm, neonatal congenital heart disease, neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia, neonatal general surgery, etc. The diagnostic criteria for AKI used in the original studies varied and were mainly divided into the following three: pediatric risk, injury, failure, loss, final and end stage (PRIFLE) (67), Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) (68) and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) (69). The most frequently used measurement method for blood or urine NGAL in the included studies was enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and 7 studies used immunoturbidimetry (17, 19, 22, 51, 54, 58, 61), 2 studies used chemiluminescence microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) (20, 33), and 1 study used Fluorescence-based immunoassay (IFA) (36). The main characteristics and details of all included study are shown in Table 1, and the quality assessment of the 53 included studies is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies of AKI in children.

| No | Author | Study Design | Country | NGAL source | Determination method | Diagnostic criteria | Pathogenesis background (y) | Events | Sample size | Hospital departments | Boy's Proportion | Age stage | Sampling Time (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jaya Mishra | Cohort study | USA | Urine/Blood | ELISA | pRIFLE | CPB | 20 | 71 | Admission | 0.63 | Children | 2 (after CPB) |

| 2 | Catherine L Dent | Cohort study | USA | Blood | ELISA | pRIFLE | CPB | 45 | 120 | Admission | 0.53 | Children | 2 (after CPB) |

| 3 | Michael Zappitelli | Cohort study | USA | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | Critically-ill children | 106 | 140 | PICU | 0.54 | Children | 48 (after admission) |

| 4 | Michael Bennett | Cohort study | USA | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | CPB | 99 | 196 | Admission | 0.53 | Children | 2 (after CPB) |

| 5 | Derek S. Wheeler | Cohort study | USA | blood | ELISA | pRIFLE | Sepsis | 22 | 143 | PICU | 0.65 | Children | 24(after admission) |

| 6 | Catherine D | Cohort study | USA | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | CPB | 60 | 220 | Admission | 0.48 | Children | 2 (after CPB) |

| 7 | Catherine D | Cohort study | USA | Urine/blood | ELISA | pRIFLE | CPB | 112 | 373 | Admission | 0.53 | Children/Neonates | 2 (after CPB) |

| 8 | O.G. El-Farghali | Case-control | Egypt | blood | ELISA | AKIN | Critically-ill Neonates | 34 | 60 | NICU | 0.57 | Neonates | 48 (after admission) |

| 9 | Fatina I. Fadel | Cohort study | Egypt | blood | ELISA | pRIFLE | CPB | 19 | 40 | PICU | 0.50 | Children | 2 and 12 (after CPB) |

| 10 | Zaccaria Ricci | Case-control | Italy | blood | IFA | pRIFLE | CPB | 90 | 160 | PICU | 0.55 | Children | 24 (after admission) |

| 11 | Kosmas Sarafidis | Case-control | Greece | Urine/Blood | ELISA | KDIGO | Asphyxiated Neonates | 8 | 13 | NICU | 0.77 | Neonates | 24 (after birth) |

| 12 | S. B. Hoffman | Cohort study | USA | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | Critically-ill Neonates | 15 | 35 | NICU | 0.60 | Neonates | 24 (after admission) |

| 13 | Amira peco-Antic | Cohort study | Serbia | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | CPB | 18 | 112 | Admission | 0.58 | Children | 24 (after CPB) |

| 14 | N. E. Raggal | Cohort study | Egypt | blood | ELISA | KDIGO | Asphyxiated Neonates | 12 | 30 | NICU | 0.57 | Neonates | 6 (after birth) |

| 15 | Stefanie Seitz | Cohort study | Germany | Urine | CMIA | pRIFLE | CPB | 76 | 139 | Admission | 0.55 | Children | 2 (after CPB) |

| 16 | Doaa Mohammed Youssef | Cohort study | Egypt | Blood | ELISA | pRIFLE | Critically-ill Neonates | 13 | 60 | PICU | 0.47 | Children | at the time of admission |

| 17 | Jianyong Zheng | Cohort study | China | Urine | ELISA | AKIN | CPB | 29 | 58 | Admission | 0.67 | Children | 4 (after CPB) |

| 18 | A.J.Alcaraz | Cohort study | Spain | Urine | Immunoturbidimetry | pRIFLE | CPB | 42 | 106 | PICU | 0.58 | Children | 1 (after CPB) |

| 19 | Kosmas Sarafidis | Case-control | Greece | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | Preterm neonates | 11 | 22 | NICU | 0.50 | Neonates | at the time of admission |

| 20 | Yilmaz Tabel | Case-control | Turkey | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | Preterm neonates | 6 | 50 | NICU | 0.58 | Neonates | 24 (after admission) |

| 21 | Sevgi Yavuz | Cohort study | Turkey | Urine/Blood | ELISA | pRIFLE | burned children | 6 | 22 | PICU | 0.55 | Children | at the time of admission |

| 22 | M. A. Almalky | Case-control | Egypt | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | solid tumors | 14 | 30 | Admission | 0.50 | Children | at the end of the chemotherapy protocol |

| 23 | Farida Essajee | Cohort study | Kenya | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | Asphyxiated Neonates | 60 | 108 | NICU | 0.60 | Neonates | 24 (after birth) |

| 24 | B. Pejovic | Case-control | Serbia | Blood | ELISA | KDIGO | Asphyxiated Neonates | 73 | 108 | NICU | 0.60 | Neonates | 2 and 4 (after birth) |

| 25 | Piotr Surmiak | Cohort study | Poland | Blood | ELISA | AKIN | Heart syndrome | 8 | 21 | NICU | 0.38 | Neonates | During childbirth |

| 26 | Alexandra JM Zwiers | Cohort study | TheNetherlands | Urine | CMIA | pRIFLE | Critically-ill Neonates | 35 | 100 | NICU | 0.66 | Neonates | 6 (after admission) |

| 27 | Mohammed Farouk M | Cohort study | Egypt | Blood | ELISA | pRIFLE | Sepsis | 30 | 65 | PICU | 0.49 | Children | 24 (after admission) |

| 28 | C. Channanayaka | Cohort study | India | Blood | Immunoturbidimetry | KDIGO | Asphyxiated Neonates | 3 | 30 | NICU | 0.50 | Neonates | 6 (after birth) |

| 29 | Mehmet Yekta Oncel | Case-control | Turkey | Urine | ELISA | AKIN | Asphyxiated Neonates | 15 | 41 | NICU | 0.56 | Neonates | 24 (after birth) |

| 30 | M. Hanna | Case-control | USA | Urine | Immunoturbidimetry | KDIGO | Critically-ill Neonates | 25 | 45 | NICU | 0.44 | Neonates | 24 (after admission) |

| 31 | V. Tanigasalam | Cohort study | India | Urine | ELISA | AKIN | Asphyxiated Neonates | 55 | 120 | NICU | 0.57 | Neonates | 6 (after birth) |

| 32 | M. Baumert | Cohort study | Poland | Blood | Immunoturbidimetry | AKIN | Asphyxiated Neonates | 8 | 43 | NICU | 0.53 | Neonates | 24 (after birth) |

| 33 | A. T. Elmas | Case-control | Turkey | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | Preterm neonates | 13 | 64 | NICU | 0.48 | Neonates | 24 (after birth) |

| 34 | YU’E SONG | Case-control | China | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | Asphyxiated Neonates | 48 | 93 | NICU | 0.56 | Neonates | 24 and 48 (after birth) |

| 35 | Neamatollah Ataei | Cohort study | Iran | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | Admission | 13 | 96 | Admission | 0.56 | Children | within 6 h of admission |

| 36 | Jameela Abdulaziz Kari | Cohort study | Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | Critically ill children | 22 | 40 | PICU | 0.45 | Children | at the time of admission |

| 37 | Kathleen G. Brennan | Cohort study | USA | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | CPB | 17 | 76 | NICU | 0.70 | Neonates | 4 (after CPB) |

| 38 | Dana Y. Fuhrman | Cohort study | USA | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | undergoing liver transplantation | 6 | 16 | PICU | 0.56 | Children | within 6 h after transplant |

| 39 | Nastaran Khosravi | Case-control | Iran | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | Critically-ill Neonates | 75 | 156 | NICU | 0.48 | Neonates | at the time of admission |

| 40 | Hui LI | Cohort study | China | Blood | ELISA | KDIGO | Nephrotoxic medication | 20 | 62 | Admission | 0.53 | Children | 24 (after admission) |

| 41 | Zhen Wang | Cohort study | China | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia-related | 27 | 196 | NICU | 0.48 | Neonates | 24 (after admission) |

| 42 | Fumiya Yoneyama | Case-control | Japan | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | CPB | 47 | 103 | NICU | 0.52 | Children | at the time of admission |

| 43 | Ying Zhang | case-control | China | Urine | Immunoturbidimetry | KDIGO | Asphyxiated Neonates | 37 | 110 | NICU | 0.67 | Neonates | 24 (after birth) |

| 44 | Yamini Agarwal | Cohort study | India | Blood | ELISA | pRIFLE | CI-AKI | 35 | 100 | PICU | 0.60 | Children | at 6 h after contrast |

| 45 | Walaa H Ali | Case-control | Egypt | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | Asphyxiated Neonates | 18 | 45 | NICU | 0.62 | Neonates | 6 (after birth) |

| 46 | Bhattacharjee Aniruddha | Cohort study | India | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | CPB | 42 | 76 | PICU | 0.67 | Children | 6 (after CPB) |

| 47 | Nugroho Setia Budi | Case-control | Indonesia | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | Sepsis | 17 | 30 | PICU | 0.70 | Children | at the time of admission |

| 48 | Cara L. Slagle | Cohort study | USA | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | general surgical procedures | 33 | 141 | NICU | 0.55 | Neonates | 24 (after general surgical) |

| 49 | Vijai Williams | Case-control | India | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | DKA | 35 | 66 | PICU | 0.50 | Children | 48 (after admission) |

| 50 | Anthony Batte | Case-control | Uganda | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | SCA | 35 | 185 | Admission | 0.58 | Children | 2 (after admission) |

| 51 | Slobodan Galić | Cohort study | Croatia | Urine/Blood | Immunoturbidimetry | KDIGO | CPB | 25 | 100 | Admission | 0.51 | Children | 6 and 12 (after CPB) |

| 52 | Sudeep K Kapalavai | Cohort study | India | Urine | ELISA | pRIFLE | Critically ill Children | 59 | 130 | PICU | 0.55 | Children | 6 (after admission) |

| 53 | Kelly R. McMahon | Cohort study | Canada | Urine | ELISA | KDIGO | Nephrotoxic medication | 46 | 156 | Admission | 0.50 | Children | at early cisplatin visits |

| 22 | 127 | 0.51 | at late cisplatin visits |

1. children are younger persons aged > 28 days, Neonates are babies born 0–28 days. 2. PRIFLE, pediatric risk, injury, failure, loss, final and end stage; AKIN, Acute Kidney Injury Network; KDIGO, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes.

3.3. Quality assessment

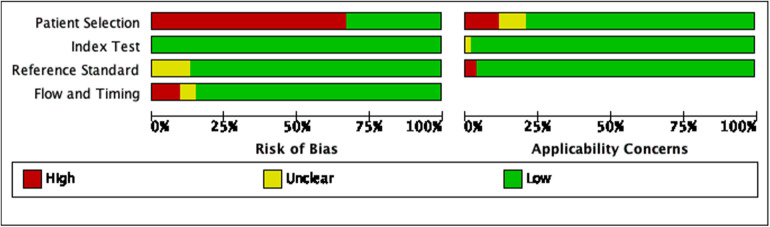

Of all included studies, 19 studies used case-control studies (11, 16, 19, 22, 24, 29, 31, 34–36, 38, 39, 43, 48, 49, 52, 57, 61, 64), and the remaining 34 used cohort studies; 7 studies did not report whether the interpretation of the gold standard results was blinded (26, 29, 38, 43, 45, 48, 57); 4 studies did not report whether there was an appropriate time interval between the trial under review and the gold standard (10, 32, 49, 64), and 3 studies had an inappropriate time interval between the trial under review and the gold standard (19, 31, 65); patients in 2 studies received two or more different gold standards (42, 56); in the matching of the included patients' backgrounds and evaluation questions, 3 studies had a high risk of bias because of the special NGAL measurement methods (20, 33, 36)and 1 study had a high risk of bias because the overall ages of the patients were too old (62). Two studies have a high risk of bias in the evaluation of the applicability of the gold standard (31, 56). The specific evaluation results are shown in Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S1.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph.

3.4. Meta-analysis

3.4.1. Predictive accuracy of overall NGAL for AKI in children

Of these 53 studies, 9 studies were multiarm predictive diagnostic studies (17, 19, 25, 31, 35, 38, 40, 42, 46), thus equaling 64 for the total number of meta-analyses. A bivariate effect model was used to perform a meta-analysis of NGALto predict AKI in children, with a sensitivity of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.77–0.86), specificity of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.78–0.86), and an SROC of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.86–0.91), DOR 21 (95% CI: 14–31), PLR (Positive likelihood ratio) 4.6 (95% CI: 3.6–5.8), NLR (Negative likelihood ratio) 0.22 (95% CI: 0.17–0.29). The results of the subgroup analysis can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis (sensitivity analysis) of prediction of AKI by overall NGAL.

| Subgroup | Levels | Number | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | SROC (95% CI) | DOR (95% CI) | PLR (95% CI) | NLR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design | cohort study | 22 | 0.80[0.70,0.87] | 0.80[0.72,0.85] | 0.87[0.83–0.89] | 16[9,29] | 3.9[2.8,5.4] | 0.25[0.16,0.38] |

| case-control study | 42 | 0.82[0.77,0.87] | 0.83[0.78,0.87] | 0.90[0.87–0.92] | 23[13,40] | 4.9[3.6,6.7] | 0.21[0.16,0.29] | |

| Determination method | ELISA | 54 | 0.83[0.78,0.87] | 0.83[0.78,0.86] | 0.90[0.87–0.92] | 23[15,36] | 4.8[3.8,6.1] | 0.21[0.16,0.27] |

| IFA | 1 | 0.81 | 0.74 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| CMIA | 2 | 0.75–0.89 | 0.73–0.95 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Immunoturbidimetry | 7 | 0.82[0.73,0.88] | 0.79[0.61,0.90] | 0.86[0.82–0.88] | 16[5,53] | 3.8[1.8,7.9] | 0.23[0.14,0.39] | |

| Diagnostic criteria | pRIFLE | 33 | 0.83[0.75,0.88] | 0.85[0.79,0.89] | 0.91[0.88–0.93] | 27[14,52] | 5.4[3.8,7.8] | 0.20[0.14,0.30] |

| AKIN | 6 | 0.85[0.78,0.90] | 0.88[0.82,0.92] | 0.93[0.91–0.95] | 43[22,85] | 7.2[4.7,11.1] | 0.17[0.11,0.25] | |

| KDIGO | 25 | 0.79[0.72,0.84] | 0.76[0.69,0.81] | 0.84[0.81–0.87] | 12[7,19] | 3.3[2.5,4.2] | 0.28[0.21,0.38] | |

| Pathogenesis background | CPB | 21 | 0.85[0.74,0.92] | 0.88[0.83,0.92] | 0.93[0.90–0.95] | 41[17,97] | 7.1[4.8,10.4] | 0.17[0.10,0.30] |

| Asphyxiated Neonates | 15 | 0.83[0.77,0.88] | 0.80[0.70,0.87] | 0.88[0.85–0.91] | 20[9,43] | 4.1[2.6,6.6] | 0.21[0.15,0.30] | |

| Critically ill children | 17 | 0.72[0.63,0.80] | 0.74[0.63,0.82] | 0.79[0.75–0.82] | 7[4,14] | 2.7[1.9,4.1] | 0.37[0.27,0.53] | |

| Critically-ill Neonates | 11 | 0.83[0.74,0.90] | 0.81[0.73,0.88] | 0.89[0.86–0.92] | 22[12,40] | 4.5[3.1,6.5] | 0.20[0.13,0.32] | |

| Hospital departments | Admission | 20 | 0.83[0.75,0.89] | 0.84[0.77,0.90] | 0.91[0.88–0.93] | 27[11,62] | 5.3[3.4,8.4] | 0.20[0.13,0.32] |

| NICU | 27 | 0.83[0.79,0.87] | 0.80[0.74,0.85] | 0.89[0.86–0.91] | 21[13,32] | 4.3[3.2,5.7] | 0.21[0.16,0.27] | |

| PICU | 17 | 0.75[0.61,0.85] | 0.82[0.71,0.89] | 0.86[0.82–0.88] | 13[6,31] | 4.1[2.5,6.6] | 0.31[0.19,0.50] | |

| Age stage | Neonates | 28 | 0.85[0.80,0.90] | 0.82[0.76,0.87] | 0.91[0.88–0.93] | 27[15,49] | 4.9[3.5,6.7] | 0.18[0.13,0.25] |

| children | 36 | 0.78[0.71,0.84] | 0.82[0.76,0.87] | 0.87[0.84–0.90] | 17[9,29] | 4.4[3.1,6.1] | 0.26[0.19,0.36] | |

| Overall | 64a | 0.82[0.77,0.86] | 0.82[0.78,0.86] | 0.89[0.86–0.91] | 21[14,31] | 4.6[3.6,5.8] | 0.22[0.17,0.29] |

Since several included studies were multi-armed diagnostic tests, they also met our exclusion criteria. For each arm, it also met our inclusion criteria, so its overall number would outnumber the number of studies.

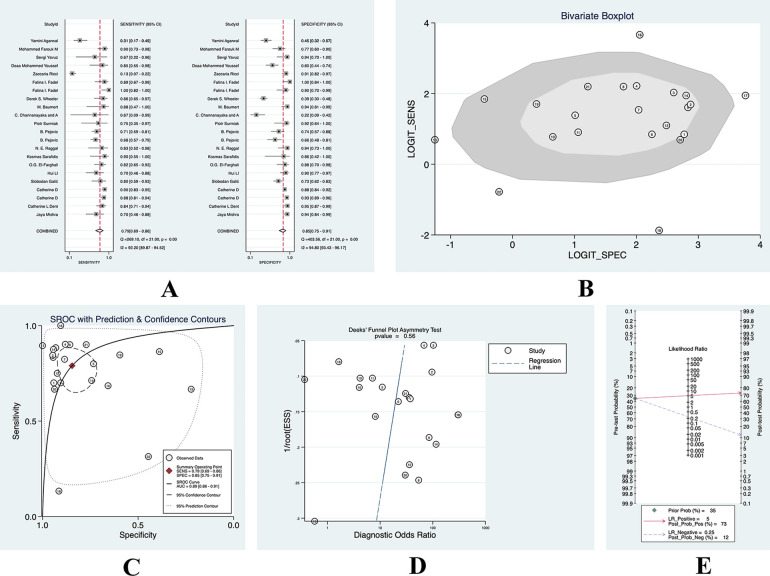

We found that AKI occurred in 35% of these included patients, and we used its incidence as the prior probability. With a PLR of 5 (95% CI: 3.6–5.8), the probability of being diagnosed with AKI by a diagnostic test was 0.71 and the probability of being diagnosed with non-AKI was 0.11, and we found that there was no significant publication bias. (See Figure 3 for details).

Figure 3.

(A) forest plot of overall sensitivity and specificity; (B) boxplot of overall heterogeneity; (C) overall SROC curve; (D) overall deeks funnel chart; (E) nomogram of overall clinical utility.

3.4.2. Prediction of AKI in children by NGAL in blood

After summing up all studies that measured blood NGAL, 22 studies on blood NGAL for predicting AKI were found. A bivariate effect model was used for the analysis, and the results are shown in Supplementary Table S2. The sensitivity was 0.79 (95% CI: 0.69–0.86), the specificity was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.75–0.91), and the SROC was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.89). 0.86–0.91), DOR 21 (95% CI: 9–48), PLR 5.1 (95% CI: 3.0–8.6), and NLR 0.25 (95% CI: 0.16–0.39).

Because the overall incidence of AKI of the patients we included was 35%, we still used the incidence of 35% as the prior probability. When the PLR was 5.1 (95% CI: 3.0–8.6), the probability of being diagnosed with AKI was 0.73 based on diagnostic tests and the probability of non-AKI was 0.12. See Figure 4 for details.

Figure 4.

(A) sensitivity-specificity forest plot of blood NGAL; (B) heterogeneity—polygonal boxplot of blood NGAL; (C) SROC curve of blood NGAL; (D) deeks funnel diagram of blood NGAL; (E) clinical utility nomogram of blood NGAL.

3.4.3. Prediction of AKI in children by NGAL in urine

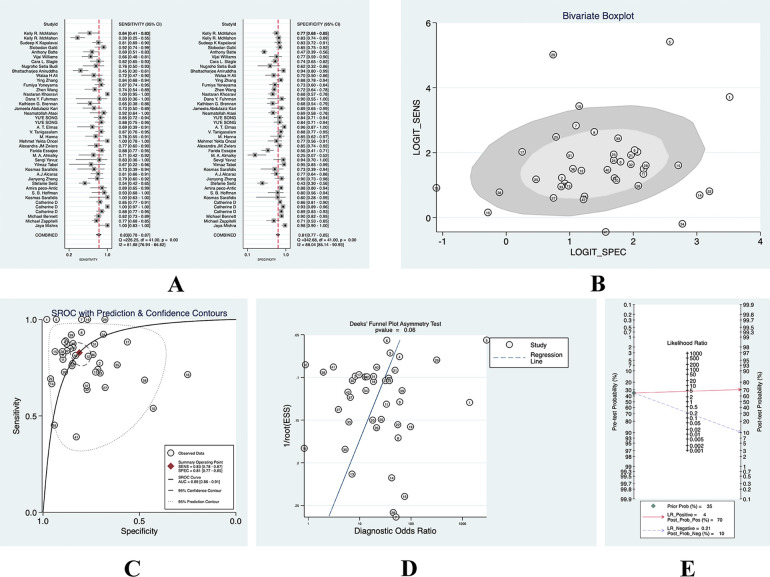

After summing all studies that measured urine NGAL, a total of 42 studies on urine NGAL for predicting AKI were found. The bivariate effect model was also used for analysis. The results are shown in Supplementary Table S3. The sensitivity was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.78–0.87), the specificity was 0.81 (95% CI: 0.77–0.85), and the SROC was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.86–0.91), DOR 21 (95% CI: 13–33), PLR 4.4 (95% CI: 3.5–5.6), and NLR 0.21 (95% CI: 0.16–0.28).

We still adopted the 35% incidence of AKI as the prior probability. When the PLR was 4.4 (95% CI: 3.0–8.6), the probability of being diagnosed with AKI by diagnostic tests was 0.70, and the probability of being diagnosed as non-AKI was 0.10. See Figure 5.

Figure 5.

(A) sensitivity-specificity forest plot of urine NGAL; (B) heterogeneity—polygonal boxplot of urine NGAL; (C) SROC curve of urine NGAL; (D) deeks funnel diagram of urine NGAL; (E) clinical utility nomogram of urine NGAL.

3.4.4. Measurement time

In the included studies, the urine or blood used to measure NGAL was collected at different times in different AKI backgrounds. For children after CPB surgery, the measurement time of NGAL was mainly in 2 h after surgery. The meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy reported a sensitivity of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.80–0.95), a specificity of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.83–0.94), SROC of 0.96 (95% CI: 0.93–0.97). For asphyxiated neonates, the measurement time of NGAL was mainly within 24 h after birth. The meta-analysis of the diagnostic tests reported a sensitivity of 0.88 (95% CI: 0.82–0.92), a specificity of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.71–0.90), SROC of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.87–0.92). After meta-analyzing all studies on the measurement time of NGAL after CPB and asphyxiated neonates, we found that the overall measurement accuracy was not as high as 2 h after CPB and 24 h after birth in asphyxiated neonates. The latter seemed to have a more ideal DOR, so we suggested that these time points were the reasonable sampling for AKI in both cases. See Table 3.

Table 3.

Meta-analysis (sensitivity analysis) of NGAL in predicting AKI after CPB.

| Subgroup | Number | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | SROC (95% CI) | DOR (95% CI) | PLR (95% CI) | NLR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After CPB (hours) | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| 1 | 1 | 0.82 | 0.76 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | 11 | 0.90[0.80,0.95] | 0.90[0.83,0.94] | 0.96[0.93–0.97] | 80[24,269] | 9.0[5.0,16.1] | 0.11[0.05,0.23] |

| 4 | 3 | 0.63–0.87 | 0.68–0.89 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 6 | 2 | 0.45–0.95 | 0.85–0.95 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 12 | 2 | 0.8–0.89 | 0.73–1 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 24 | 2 | 0.13–0.91 | 0.88–0.91 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Overall | 21 | 0.85[0.74,0.92] | 0.88[0.83,0.92] | 0.93[0.90–0.95] | 41[17,97] | 7.1[4.8,10.4] | 0.17[0.10,0.30] |

| Asphyxiated Neonates (after birth, hours) | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| 0 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.895 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | 1 | 0.69 | 0.657 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | 1 | 0.719 | 0.743 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 6 | 4 | 0.8 | 0.895 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 24 | 7 | 0.88[0.82,0.92] | 0.82[0.71,0.90] | 0.90[0.87–0.92] | 34[16,72] | 4.9[2.9,8.5] | 0.15[0.10,0.22] |

| 48 | 1 | 0.875 | 0.843 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Overall | 15 | 0.83[0.77,0.88] | 0.80[0.70,0.87] | 0.88[0.85–0.91] | 20[9,43] | 4.1[2.6,6.6] | 0.21[0.15,0.30] |

4. Discussion

We found NGAL had a high predictive value for AKI in children. There were no significant differences between blood and urine NGAL. At the same time, we also found that the measurement time of NGAL was mainly 2 h after CPB, and the main measurement time for asphyxiated neonates was 24 h after birth.

L. Taddeo et al. (70) conducted a systematic review in 2017 to evaluate the accuracy of NGAL which was taken as the biomarker of AKI in children. It analyzed a total of 13 studies including 1,629 children, and its combined sensitivity for urine NGAL was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.62–0.85), the combined specificity was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.88–0.96). When the number of included studies increased to 53 and the number of cases increased to 5,048 patients, the results of this study consist with those of previous studies.

We also found reports on other AKI predictors in recent years. H. M. Jia et al. (71) conducted a systematic review evaluating the effects of urinary tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 [TIMP-2] and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 [IGFBP7] on the early diagnostic value of acute kidney injury, which included 9 eligible published studies with 1,886 cases. The combined sensitivity was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.79–0.87), and the specificity was 0.55 (95% CI: 0.52–0.57). We noticed that these two predictors had high predictive accuracy for the occurrence of AKI, however, its accuracy for the people without AKI was not enough. Compared with these two factors, NGAL had significantly improved sensitivity and specificity in predicting AKI. M. Fazel et al. (72) conducted a systematic review to assess the accuracy of Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (Kim-1) in predicting AKI in children within 12 h after admission, including 13 articles, which showed that the final AUC of urinary Kim-1 in predicting AKI was 0.69 (95% CI: 0.62–0.77), and its conclusion also suggested that Kim-1 seemed to have a moderate value in predicting AKI in children. P. Susantitaphong et al. (9) conducted a meta-analysis on 7 cohort studies. For urinary L-FABP, the sensitivity of for the diagnosis of AKI was 74.5% (95% CI: 60.4%–84.8%), and the specificity was 77.6% (95% CI: 61.5%–88.2%). In general, the current predictors of AKI in children include TIMP-2, IGFBP7, Kim-1, L-FABP, etc. Our study shows that NGAL seems to have a better predictive effect.

NGAL has different predictive accuracy in different AKI occurrence backgrounds. A. Haase-Fielitz et al. (73) conducted a systematic review that included 2,527 adults and 1,342 children who had undergone cardiac surgery. The results showed that urine NGAL could be used for the early prediction of AKI after cardiac surgery, but it did not carry out a meta-analysis, nor did it delve into the occurrence time of AKI and the measurement time of NGAL after cardiac surgery. F. F. Zhou et al. (74) researched on the diagnostic accuracy of NGAL within 12 h after cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury (CSA-AKI), including 24 studies (with 33 datasets of 4,066 patients). The overall sensitivity was 0.68 (95% CI: 0.65–0.70), and the specificity was 0.79 (95% CI: 0.77–0.80). After we expanded the number of included studies and the number of patients, we found that NGAL measurement performed 2 h after CPB had the best diagnostic performance for AKI.

Bellos et al. (75) conducted a systematic review of the accuracy of serum and urine NGAL in detecting AKI in neonates with perinatal asphyxia. A total of 11 studies were included, with a total of 652 cases. The sensitivity of serum NGAL in this study was 0.818 (95% CI: 0.668–0.909), and the specificity was 0.870 (95% CI: 0.754–0.936). The results of it are consistent with our results in the subgroup analysis of AKI associated with asphyxiated neonates, but this study did not conduct an analysis or draw conclusions on the best time for NGA1 measurement in asphyxiated neonates, so our study filled this gap.

This systematic review has the following advantages: (1) On the basis of previous studies, it comprehensively explored the predictive value of NGAL for children with AKI based on the results of many studies in recent years. (2) Among the newly discovered predictors of AKI in children in recent years, no matter it is from blood or urine, NGAL is a valuable predictor, which can provide a basis for the future clinical measurement of AKI, so that predictor samples can be collected through a non-invasively way and reduce patients' pain. (3) It is even found that there is no significant difference in various measurement methods, which can reduce the waste of medical resources caused by different measurement methods in clinical practice. (4) In addition, this study can also provide a reasonable choice of sampling or measurement time for predicting certain diseases leading to AKI. Effective predictors are essential for improving the predictive accuracy of risk models. Our research shows that NGAL has a good predictive value and can be included into the risk stratification models based on machine learning to improve their predictive accuracy.

However, we noticed some limitations. First, there was huge discrepancy between the number of studies which measure blood, urinary or both NGAL. Second, in the analyzed studies, there is various time gap between trial and gold standard analysis, and the AKI definition is also variable. Third, for the measurement time of some AKI backgrounds (such as sepsis, burns, solid tumors, use of nephrotoxic drugs, angiography-related, neonatal general surgery, etc.), due to the limited number of relevant reports, it may still be cautious to conclude in this regard.

5. Conclusion

NGAL is a valuable predictor for AKI in children with different backgrounds, and there is no significant difference in the predictive value of NGAL in urine and blood, which can provide a non-invasive choice for clinical practice. According to the current evidence, the accuracy of NGAL measurement is the best at 2 h after CPB and 24 h after birth in asphyxiated newborns. At the same time, we also noticed that there is no significant difference in different measurement methods of NGAL, which can provide guidance for the development and verification of assessment tools for the risk of AKI in children in the future. This variable can also be introduced into the machine learning method, and in the future, it is expected to develop a popular and clinically practical simple prediction system for the prediction of AKI in children based on the machine learning method.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the researchers and study participants for their contributions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

ZZ: Conceptualization/design, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Supervision/oversight, Resources, Writing—drafting the initial manuscript, Writing—review or editing of the manuscript; BC: Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Writing—drafting the initial manuscript, Writing—review or editing of the manuscript; FT: Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—review or editing of the manuscript; XL: Conceptualization/design, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Supervision/oversight, Writing—drafting the initial manuscript, Writing—review or editing of the manuscript; DX: Conceptualization/design, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision/oversight, Resources, Writing—drafting the initial manuscript, Writing—review or editing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2023.1147033/full#supplementary-material.

References

- 1.Lameire NH, Bagga A, Cruz D, De Maeseneer J, Endre Z, Kellum JA, et al. Acute kidney injury: an increasing global concern. Lancet. (2013) 382(9887):170–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60647-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rewa O, Bagshaw SM. Acute kidney injury-epidemiology, outcomes and economics. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2014) 10(4):193–207. 10.1038/nrneph.2013.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Jboor W, Almardini R, Al Bderat J, Frehat M, Al Masri H, Alajloni MS. Acute kidney injury in critically ill child. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. (2016) 27(4):740–7. 10.4103/1319-2442.185236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nawaz S, Afzal K. Pediatric acute kidney injury in North India: a prospective hospital-based study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. (2018) 29(3):689–97. 10.4103/1319-2442.235172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickkers P, Darmon M, Hoste E, Joannidis M, Legrand M, Ostermann M, et al. Acute kidney injury in the critically ill: an updated review on pathophysiology and management. Intensive Care Med. (2021) 47(8):835–50. 10.1007/s00134-021-06454-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng PY, Chen YT, Wang CH, Chiu KM, Peng YS, Hsu SP, et al. Prediction of the development of acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery by machine learning. Crit Care. (2020) 24(1):478. 10.1186/s13054-020-03179-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong J, Feng T, Thapa-Chhetry B, Cho BG, Shum T, Inwald DP, et al. Machine learning model for early prediction of acute kidney injury (AKI) in pediatric critical care. Crit Care . (2021) 25(1):288. 10.1186/s13054-021-03724-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parikh CR, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Garg AX, Kadiyala D, Shlipak MG, Koyner JL, et al. Performance of kidney injury molecule-1 and liver fatty acid-binding protein and combined biomarkers of AKI after cardiac surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2013) 8(7):1079–88. 10.2215/CJN.10971012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Susantitaphong P, Siribamrungwong M, Doi K, Noiri E, Terrin N, Jaber BL. Performance of urinary liver-type fatty acid-binding protein in acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. (2013) 61(3):430–9. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zappitelli M, Washburn KK, Arikan AA, Loftis L, Ma Q, Devarajan P, et al. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is an early marker of acute kidney injury in critically ill children: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. (2007) 11(4):R84. 10.1186/cc6089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett M, Dent CL, Ma Q, Dastrala S, Grenier F, Workman R, et al. Urine NGAL predicts severity of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a prospective study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2008) 3(3):665–73. 10.2215/CJN.04010907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devarajan P. Update on mechanisms of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2006) 17(6):1503–20. 10.1681/ASN.2006010017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beitland S, Waldum-Grevbo BE, Nakstad ER, Berg JP, Trøseid AS, Brusletto BS, et al. Urine biomarkers give early prediction of acute kidney injury and outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit Care. (2016) 20(1):314. 10.1186/s13054-016-1503-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honore PM, Nguyen HB, Gong M, Chawla LS, Bagshaw SM, Artigas A, et al. Urinary tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 for risk stratification of acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med. (2016) 44(10):1851–60. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. (2011) 155(8):529–36. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams V, Jayashree M, Nallasamy K, Dayal D, Rawat A, Attri SV. Serial urinary neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin in pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis with acute kidney injury. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. (2021) 7(1):20. 10.1186/s40842-021-00133-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMahon KR, Chui H, Rassekh SR, Schultz KR, Blydt-Hansen TD, Mammen C, et al. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and kidney injury molecule-1 to detect pediatric cisplatin-associated acute kidney injury. Kidney360. (2022) 3(1):37–50. 10.34067/KID.0004802021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapalavai SK, Ramachandran B, Krupanandan R, Sadasivam K. Usefulness of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a predictor of acute kidney injury in critically ill children. Indian J Crit Care Med. (2022) 26(5):634–8. 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galić S, Milošević D, Filipović-Grčić B, Rogić D, Vogrinc Ž, Ivančan V, et al. Early biochemical markers in the assessment of acute kidney injury in children after cardiac surgery. Ther Apher Dial. (2022) 26(3):583–93. 10.1111/1744-9987.13736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zwiers AJ, de Wildt SN, van Rosmalen J, de Rijke YB, Buijs EA, Tibboel D, et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin identifies critically ill young children with acute kidney injury following intensive care admission: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. (2015) 19(1):181. 10.1186/s13054-015-0910-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng J, Xiao Y, Yao Y, Xu G, Li C, Zhang Q, et al. Comparison of urinary biomarkers for early detection of acute kidney injury after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery in infants and young children. Pediatr Cardiol. (2013) 34(4):880–6. 10.1007/s00246-012-0563-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Zhang B, Wang D, Shi W, Zheng A. Evaluation of novel biomarkers for early diagnosis of acute kidney injury in asphyxiated full-term newborns: a case-control study. Med Princ Pract. (2020) 29(3):285–91. 10.1159/000503555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Youssef DM, Esh AM, Helmy Hassan E, Ahmed TM. Serum NGAL in critically ill children in ICU from a single center in Egypt. ISRN Nephrol. (2013) 2013:140905. 10.5402/2013/140905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoneyama F, Okamura T, Takigiku K, Yasukouchi S. Novel urinary biomarkers for acute kidney injury and prediction of clinical outcomes after pediatric cardiac surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. (2020) 41(4):695–702. 10.1007/s00246-019-02280-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yavuz S, Anarat A, Acartürk S, Dalay AC, Kesiktaş E, Yavuz M, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin as an indicator of acute kidney injury and inflammation in burned children. Burns. (2014) 40(4):648–54. 10.1016/j.burns.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wheeler DS, Devarajan P, Ma Q, Harmon K, Monaco M, Cvijanovich N, et al. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a marker of acute kidney injury in critically ill children with septic shock. Crit Care Med. (2008) 36(4):1297–303. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318169245a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z, Jin L, Shen T, Zhan SJSV. The value of urine NAG, NGAL combined with serum Cys-C in early diagnosis of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia-related acute kidney injury. Signa Vitae. (2020) 16(2):109–13. 10.22514/sv.2020.16.0055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanigasalam V, Bhat BV, Adhisivam B, Sridhar MG, Harichandrakumar KT. Predicting severity of acute kidney injury in term neonates with perinatal asphyxia using urinary neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin. Indian J Pediatr. (2016) 83(12–13):1–5. 10.1007/s12098-016-2178-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabel Y, Elmas A, Ipek S, Karadag A, Elmas O, Ozyalin F. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as an early biomarker for prediction of acute kidney injury in preterm infants. Am J Perinatol. (2014) 31(2):167–74. 10.1055/s-0033-1343770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Surmiak P, Baumert M, Fiala M, Walencka Z, Więcek A. Umbilical neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin level as an early predictor of acute kidney injury in neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. BioMed Res Int. (2015) 2015:360209. 10.1155/2015/360209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song Y, Sun S, Yu Y, Li G, Song J, Zhang H, et al. Diagnostic value of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for renal injury in asphyxiated preterm infants. Exp Ther Med. (2017) 13(4):1245–8. 10.3892/etm.2017.4107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slagle CL, Goldstein SL, Gavigan HW, Rowe JA, Krallman KA, Kaplan HC, et al. Association between elevated urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and postoperative acute kidney injury in neonates. J Pediatr. (2021) 238:193–201. e2. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seitz S, Rauh M, Gloeckler M, Cesnjevar R, Dittrich S, Koch AM. Cystatin C and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: biomarkers for acute kidney injury after congenital heart surgery. Swiss Med Wkly. (2013) 3:w13744. 10.4414/smw.2013.13744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarafidis K, Tsepkentzi E, Diamanti E, Agakidou E, Taparkou A, Soubasi V, et al. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin to predict acute kidney injury in preterm neonates. A pilot study. Pediatr Nephrol. (2014) 29(2):305–10. 10.1007/s00467-013-2613-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarafidis K, Tsepkentzi E, Agakidou E, Diamanti E, Taparkou A, Soubasi V, et al. Serum and urine acute kidney injury biomarkers in asphyxiated neonates. Pediatr Nephrol. (2012) 27(9):1575–82. 10.1007/s00467-012-2162-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ricci Z, Netto R, Garisto C, Iacoella C, Favia I, Cogo P. Whole blood assessment of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin versus pediatricRIFLE for acute kidney injury diagnosis and prognosis after pediatric cardiac surgery: cross-sectional study*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2012) 13(6):667–70. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182601167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raggal NE, Khafagy SM, Mahmoud NH, Beltagy SE. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a marker of acute kidney injury in asphyxiated neonates. Indian Pediatr. (2013) 50(5):459–62. 10.1007/s13312-013-0153-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pejović B, Erić-Marinković J, Pejović M, Kotur-Stevuljević J, Peco-Antić A. Detection of acute kidney injury in premature asphyxiated neonates by serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (sNGAL)–sensitivity and specificity of a potential new biomarker. Biochem Med (Zagreb). (2015) 25(3):450–9. 10.11613/BM.2015.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oncel MY, Canpolat FE, Arayici S, Alyamac Dizdar E, Uras N, Oguz SS. Urinary markers of acute kidney injury in newborns with perinatal asphyxia (.). Renal Fail. (2016) 38(6):882–8. 10.3109/0886022X.2016.1165070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mishra J, Dent C, Tarabishi R, Mitsnefes MM, Ma Q, Kelly C, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet. (2005) 365(9466):1231–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74811-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, Xu Q, Wang Y, Chen K, Li J. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for predicting high dose methotrexate associated acute kidney injury in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. (2020) 85(1):95–103. 10.1007/s00280-019-03980-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krawczeski CD, Woo JG, Wang Y, Bennett MR, Ma Q, Devarajan P. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin concentrations predict development of acute kidney injury in neonates and children after cardiopulmonary bypass. J Pediatr. (2011) 158(6):1009–15.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.12.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khosravi N, Seirafianpour F, Mashaiekhi M, Safari S, Khalesi N, Otukesh H, et al. Importance of urinary NGAL relative to Serum creatinine level for predicting acute neonatal kidney injury. Iranian J Neonatol. (2020) 11(4):21–4. 10.22038/ijn.2020.43344.1719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kari JA, Shalaby MA, Sofyani K, Sanad AS, Ossra AF, Halabi RS, et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and serum cystatin C measurements for early diagnosis of acute kidney injury in children admitted to PICU. World J Pediatr. (2018) 14(2):134–42. 10.1007/s12519-017-0110-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffman SB, Massaro AN, Soler-García AA, Perazzo S, Ray PE. A novel urinary biomarker profile to identify acute kidney injury (AKI) in critically ill neonates: a pilot study. Pediatr Nephrol. (2013) 28(11):2179–88. 10.1007/s00467-013-2524-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fadel FI, Abdel Rahman AM, Mohamed MF, Habib SA, Ibrahim MH, Sleem ZS, et al. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as an early biomarker for prediction of acute kidney injury after cardio-pulmonary bypass in pediatric cardiac surgery. Arch Med Sci. (2012) 8(2):250–5. 10.5114/aoms.2012.28552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Essajee F, Were F, Admani B. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in asphyxiated neonates: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Nephrol. (2015) 30(7):1189–96. 10.1007/s00467-014-3035-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elmas AT, Karadag A, Tabel Y, Ozdemir R, Otlu G. Analysis of urine biomarkers for early determination of acute kidney injury in non-septic and non-asphyxiated critically ill preterm neonates. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2017) 30(3):302–8. 10.3109/14767058.2016.1171311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El-Farghali OG, El-Raggal NM, Mahmoud NH, Zaina GA. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a predictor of acute kidney injury in critically-ill neonates. Pak J Biol Sci. (2012) 15(5):231–7. 10.3923/pjbs.2012.231.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dent CL, Ma Q, Dastrala S, Bennett M, Mitsnefes MM, Barasch J, et al. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin predicts acute kidney injury, morbidity and mortality after pediatric cardiac surgery: a prospective uncontrolled cohort study. Crit Care. (2007) 11(6):R127. 10.1186/cc6192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chandrashekar C, Venkatkrishnan AJ. Clinical utility of serum neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL) as an early marker of acute kidney injury in asphyxiated neonates. J Nepal Paediatr Soc. (1990) 36(2):121. 10.3126/jnps.v36i2.14985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Budi NS, Utariani A, Hanindito E, Semedi BP, Asmaningsih N. The validity of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker of acute kidney injury in pediatric patients with sepsis. Crit Care Shock. (2021) 24(2):93–103. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brennan KG, Parravicini E, Lorenz JM, Bateman DA. Patterns of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and acute kidney injury in neonates receiving cardiopulmonary bypass. Children (Basel, Switzerland). (2020) 7(9). 10.3390/children7090132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baumert M, Surmiak P, Więcek A, Walencka Z. Serum NGAL and copeptin levels as predictors of acute kidney injury in asphyxiated neonates. Clin Exp Nephrol. (2017) 21(4):658–64. 10.1007/s10157-016-1320-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ataei N, Ameli S, Yousefifard M, Oraei A, Ataei F, Bazargani B, et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and cystatin C in early detection of pediatric acute kidney injury; a diagnostic accuracy study. Emergency (Tehran, Iran). (2018) 6(1):e2. PMID: . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aniruddha B, Sharma N, Acharya AK, Patnaik S, Ramamurthy H. Comparative evaluation of AKIN, KDIGO and pRIFLE criteria and urinary biomarkers in prediction of AKI following cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB-AKI) in children. Eur J Mol Clin Med. (2021) 8(4):1790–9. Available at: https://www.embase.com/records?subaction=viewrecord&id=L2016608737. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ali WH, Ahmed HH, Hasanin HM, Kamel LH, Ahmed WO. Value of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in predicting acute kidney injury in neonates with perinatal asphyxia. Curr Pediatr Res. (2021) 25(9):919–28. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alcaraz AJ, Gil-Ruiz MA, Castillo A, López J, Romero C, Fernández SN, et al. Postoperative neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin predicts acute kidney injury after pediatric cardiac surgery*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2014) 15(2):121–30. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agarwal Y, Rameshkumar R, Krishnamurthy S, Senthilkumar GP. Incidence, risk factors, the role of plasma NGAL and outcome of contrast-induced acute kidney injury in critically ill children. Indian J Pediatr. (2021) 88(1):34–40. 10.1007/s12098-020-03414-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Afify M, Maher S, Ibrahim N, Mahmoud W. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in infants and children with sepsis-related conditions with or without acute renal dysfunction. Clin Med Insights Pediatr. (2016) 10(9):85–9. 10.4137/CMPed.S39452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hanna M, Brophy PD, Giannone PJ, Joshi MS, Bauer JA, RamachandraRao S. Early urinary biomarkers of acute kidney injury in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. (2016) 80(2):218–23. 10.1038/pr.2016.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fuhrman DY, Kellum JA, Joyce EL, Miyashita Y, Mazariegos GV, Ganoza A, et al. The use of urinary biomarkers to predict acute kidney injury in children after liver transplant. Pediatr Transplant. (2020) 24(1):e13608. 10.1111/petr.13608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Batte A, Menon S, Ssenkusu JM, Kiguli S, Kalyesubula R, Lubega J, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is elevated in children with acute kidney injury and sickle cell anemia, and predicts mortality. Kidney Int. (2022) 102(4):885–93. 10.1016/j.kint.2022.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Almalky MA, Hasan SA, Hassan TH, Shahbah DA, Arafa MA, Khalifa NA, et al. Detection of early renal injury in children with solid tumors undergoing chemotherapy by urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. Mol Clin Oncol. (2015) 3(6):1341–6. 10.3892/mco.2015.631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peco-Antić A, Ivanišević I, Vulićević I, Kotur-Stevuljević J, Ilić S, Ivanišević J, et al. Biomarkers of Acute Kidney Injury in Pediatric Cardiac Surgery. (2013) 46(13-14):1244–51. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krawczeski CD, Goldstein SL, Woo JG, Wang Y, Piyaphanee N, Ma Q, et al. Temporal relationship and predictive value of urinary acute kidney injury biomarkers after pediatric cardiopulmonary bypass. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2011) 58(22):2301–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Akcan-Arikan A, Zappitelli M, Loftis LL, Washburn KK, Jefferson LS, Goldstein SL. Modified RIFLE criteria in critically ill children with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. (2007) 71(10):1028–35. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute kidney injury network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. (2007) 11(2):R31. 10.1186/cc5713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Andrassy KM. Comments on “KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease”. Kidney Int. (2013) 84(3):622–3. 10.1038/ki.2013.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Filho LT, Grande AJ, Colonetti T, Della ÉSP, da Rosa MI. Accuracy of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for acute kidney injury diagnosis in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Nephrol. (2017) 32(10):1979–88. 10.1007/s00467-017-3704-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jia HM, Huang LF, Zheng Y, Li WX. Diagnostic value of urinary tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 for acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis. Crit Care. (2017) 21(1):77. 10.1186/s13054-017-1660-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fazel M, Sarveazad A, Mohamed Ali K, Yousefifard M, Hosseini M. Accuracy of urine kidney injury molecule-1 in predicting acute kidney injury in children; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Acad Emerg Med. (2020) 8(1):e44. PMID: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haase-Fielitz A, Haase M, Devarajan P. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a biomarker of acute kidney injury: a critical evaluation of current status. Ann Clin Biochem. (2014) 51(Pt 3):335–51. 10.1177/0004563214521795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou F, Luo Q, Wang L, Han L. Diagnostic value of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for early diagnosis of cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2016) 49(3):746–55. 10.1093/ejcts/ezv199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bellos I, Fitrou G, Daskalakis G, Perrea DN, Pergialiotis V. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as predictor of acute kidney injury in neonates with perinatal asphyxia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr. (2018) 177(10):1425–34. 10.1007/s00431-018-3221-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.