Abstract

Autologous cultured fibroblast injections for soft tissue augmentation are a potential alternative to other filler materials. No studies have compared autologous fibroblast injections and hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers for treating nasolabial folds (NLFs). To compare the efficacies and safeties of autologous cultured fibroblast injections and HA fillers for treating NLFs. This prospective, evaluator-blinded, pilot study enrolled 60 Thai female adult patients diagnosed with moderate to severe NLFs. They were randomized to receive either 3 treatments of autologous fibroblasts at 2-week intervals or 1 treatment with HA fillers. The primary outcome was the clinical improvement of the NLFs graded by 2 blinded dermatologists immediately after injection and at 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups. Objective measurement of the NLF volume was evaluated. Patient self-assessment scores, pain scores, and adverse reactions were recorded. Of the 60 patients, 55 (91.7%) completed the study protocol. The NLF volumes improved significantly in the autologous fibroblast group at all follow-ups relative to baseline (P = 0.000, 0.004, 0.000, 0.000, and 0.003). The patients in the autologous fibroblast group rated more noticeable NLF improvements than those in the HA filler group (3-month follow-up, 58.41% vs. 54.67%; 6-month follow-up, 52.50% vs. 46%; 12-month follow-up, 44.55% vs. 31.33%). No serious adverse reactions were recorded. Autologous fibroblast injections are safe and effective for treating NLFs. These injections also promise sustained growth of living cells, possibly leading to a greater persistence than shown by other fillers.

Subject terms: Clinical trials, Randomized controlled trials

Introduction

Skin aging is caused by genetic and environmental factors such as sun exposure, air pollution, smoking, alcohol abuse, and poor nutrition1. Histologically, aged skin has a thinner epidermis, atrophic dermis, and reduced amounts of subdermal adipose tissue, fibroblasts, and collagen2. The most common dermatological presentations of aging are xerosis, skin laxity, wrinkles, and benign lesions1.

Dermal fillers are commonly used for skin rejuvenation since they fill up wrinkles and replace soft-tissue volume lost due to aging3. Several types of fillers have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (US FDA), and they are categorized as temporary, semipermanent, and permanent4. Bovine collagen was the first US FDA-approved injectable filler. It has a short-lasting effect and is associated with hypersensitivity reactions5. Hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers have become popular. They offer a low immunogenic profile, safety, a range of applications, and reversibility with hyaluronidase6. However, severe complications have been reported. They include hypersensitivity reactions, foreign body granuloma, vascular occlusion, skin necrosis, and blindness7–9.

Autologous fat transfer (AFT) is another treatment option. It does not produce hypersensitivity reactions and granuloma formation because of the biocompatibility of the adipose tissues used10. However, in a retrospective study, 7 patients developed retinal artery occlusion after AFT, and they had a worse final best-corrected visual acuity than other injectables11.

In 2011, the US FDA approved Laviv (Azficel-T; Fibrocell Technologies, Inc., Exton, PA, USA) as an autologous fibroblast tissue filler to improve moderate to severe nasolabial folds (NLFs) in adults12. Autologous cultured fibroblast injections were safe and effective in improving wrinkles, acne scars, and other dermal defects for up to 12 months after administration with no known side effects13. Histologically, fibroblast injections stimulate collagen formation with a concomitant increase in the thickness and density of dermal collagen13. Other mechanisms include an induced proliferation of native fibroblasts, secretion of cofactors that can augment the dermis, and the growth of the transplanted fibroblasts14.

The objective of this study was to compare the efficacies and safeties of autologous cultured fibroblast injections and HA fillers for treating NLFs.

Materials and methods

This prospective, single-center, evaluator-blinded pilot study enrolled 60 Thai female adult patients. The women had expressed dissatisfaction with their NLFs, scoring − 1 or − 2 on the Subject Wrinkle Assessment Scale (Table 1). They also had moderate to severe NLF grades, documented using the Evaluator Wrinkle Assessment Scale (Table 2). Patients were excluded if they:

were pregnant or lactating

had a history of connective tissue disorder, skin cancers, or related diseases

had previous autologous fibroblast treatment

had treatment with fillers, lasers, or energy-based devices during the previous 12 months

had treatment using transdermal drug delivery, chemical peeling, or topical retinoid during the previous month

were allergic to collagen, meat, dairy products, gentamycin, amphotericin B, or related products

Table 1.

Subject Wrinkle Assessment Scale14.

| How do you feel about the wrinkles in the lower part of your face today? | |

|---|---|

| Score | Description |

| − 2 | I am very dissatisfied with the wrinkles of the lower part of my face |

| − 1 | I am dissatisfied with the wrinkles of the lower part of my face |

| 0 | I am somewhat satisfied with the wrinkles of the lower part of my face |

| + 1 | I am satisfied with the wrinkles of the lower part of my face |

| + 2 | I am very satisfied with the wrinkles of the lower part of my face |

Table 2.

Evaluator Wrinkle Severity Assessment Scale14.

| How do you rate the wrinkles in the lower part of the patient’s face today? | |

|---|---|

| Score | Description |

| 0 | No wrinkles visible |

| 1 | Just perceptible wrinkles |

| 2 | Shallow wrinkles |

| 3 | Moderately deep wrinkles (definite and distinct wrinkles) |

| 4 | Deep wrinkles, well-defined edges (prominent wrinkles, well defined edges) |

| 5 | Very deep wrinkles, redundant folds (very severe wrinkles, pronounced edges) |

The subjects were randomly divided following simple randomization procedures into 2 groups (“HA filler” and “autologous fibroblast”). The HA filler group was given a single injection of HA filler (Restylane; Q-Med AB, Uppsala, Sweden) on both NLFs (0.5 ml on each side) by using 22-guage cannula. The autologous fibroblast group was intradermally injected with autologous cultured fibroblasts on both NLFs (0.5 ml on each side) by using 30-guage needle. However, the fibroblast injections were administered in 3 sessions at 2-week intervals.

Autologous fibroblast preparation

Preoperatively, each patient from the autologous fibroblast group had tissue collected from the postauricular area. An injection of 2% lidocaine was given, and a 3-mm punch biopsy was performed. The donor site was closed with a single nylon (5.0) suture. The collected tissue was sterilized with povidone-iodine, and the fibroblasts were extracted with debris removal. Separation of epidermis from dermis was done using dispase in fibroblast basal medium at 2–4 °C for 1–4 h. Then, the dermis was cut into small pieces and digested in trypsin at 37 °C for 15 min to isolate dermal fibroblasts. Subsequently, the cells were cultured in fibroblast basal medium with 2% fibroblast growth medium, 1% penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) at 37 °C in a humidified air of 5% CO2 (PCO2 = 40 Torr). Media was changed every 3 days and the collected fibroblasts were then expanded to 20 × 106 cells per 1 mL of normal saline solution. As observed by light microscopy, the dermal fibroblasts were identified based on their spindle-shaped morphological features. Prior to injection, all specimens underwent standard laboratory testing: sterility using membrane filtration, endotoxin test using Limulus amoebocyte lysate, mycoplasma detection using quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and Gram staining.

Efficacy and safety assessment

The primary outcome of the study was the clinical improvement of the NLFs. The improvements were graded using a 5-point scale: 2 = “much improved,” 1 = “improved,” 0 = “no change,” − 1 = “worsened,” and − 2 = “much worsened.” Two blinded dermatologists subjectively evaluated photographs at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups. All clinical photographs were taken with identical camera settings, lighting, and positioning using a Canon PowerShot G9 standoff camera (OMNIA Imaging System, Canfield Scientific, Inc., Fairfield, NJ, USA).

In addition, the NLF facial volumes were objectively evaluated using three-dimensional photographs captured by a Vectra H1 Imaging System (Canfield Scientific Inc.) immediately after injection and at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups. Patients also performed self-assessments using the same 5-point scale at each follow-up visit. In addition, the patient pain experienced while the injections were being administered was rated using a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS). Any adverse reactions were recorded.

Statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics for Windows, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive analysis was used for demographic data. Nasolabial folds volume changes were calculated using repeated measures ANOVA and paired t-test. Subjective improvement evaluation was analyzed by using Wilcoxon signed-ranks test. A probability (P) value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Ethics Committee of the Siriraj Institutional Review Board approved this study (approval number si690/2014). The study was performed per the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before their enrollment.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Siriraj Institutional Review Board (Approval No. SI690/2014). Written informed consent was obtained for the publication and use of images prior to patients’ enrollment in the study. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its subsequent amendments and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT No. TCTR20220217002, 17/02/2022).

Results

Of the 60 female patients recruited, 55 (91.7%) completed the study protocol and were included in the final analysis. Five patients were withdrawn because they could not attend all follow-up visits. There were 30 patients in the HA group (mean age, 39.45 ± 9.89 years) and 25 in the autologous fibroblast group (mean age, 43.44 ± 8.91 years).

The objective evaluations of the volume differences in the NLFs using the Vectra H1 Imaging System are presented in Table 3. There was a significant volume improvement in the HA filler group immediately after and at the 1-month follow-up compared with baseline (P = 0.000 and 0.000, respectively). In contrast, the autologous fibroblast group showed significant volume improvements at all follow-ups compared with baseline (P = 0.000, 0.004, 0.000, 0.000, and 0.003). Furthermore, there was a significant difference between the 2 groups immediately after the HA filler injection and the first of the 3 fibroblast injections (P = 0.034).

Table 3.

Evaluation of the volume difference in the nasolabial folds using Vectra H1 Imaging System.

| Volume difference (ml) | HA filler Group | P-valuea | Autologous fibroblast group | P-valueb | P-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediately after | 0.43 ± 0.50 | 0.000* | 0.26 ± 0.31 | 0.000* | 0.034* |

| 1-month follow-up | 0.40 ± 0.83 | 0.000* | 0.17 ± 0.41 | 0.004* | 0.070 |

| 3-month follow-up | − 0.06 ± 1.41 | 0.733 | 0.20 ± 0.31 | 0.000* | 0.161 |

| 6-month follow-up | 0.03 ± 1.33 | 0.854 | 0.21 ± 0.35 | 0.000* | 0.335 |

| 12-month follow-up | − 0.34 ± 2.19 | 0.253 | 0.17 ± 0.38 | 0.003* | 0.095 |

*P value < 0.05.

P-valuea—comparing within HA filler group.

P-valueb—comparing within autologous fibroblast group.

P-valuec—comparing between HA filler group and autologous fibroblast group at the same time point.

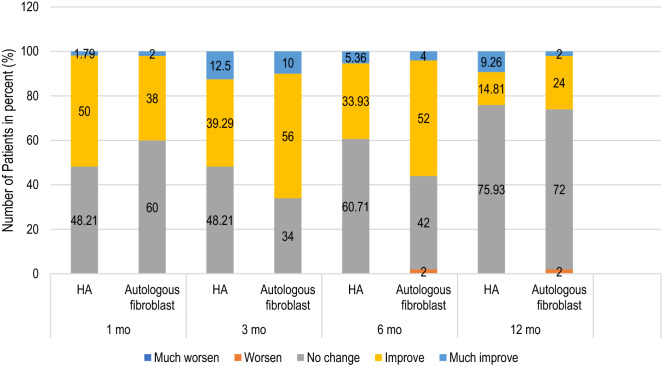

The subjective evaluations made by the 2 blinded dermatologists of the clinical improvements using the 5-point scale are illustrated in Fig. 1. In the HA group, most patients (50%) showed improvement during the 1-month follow-up compared with baseline. However, at the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups, most HA patients (48.21%, 60.71%, and 75.93%) were rated with no change. As for the autologous fibroblast group, most (60%) showed no change at the 1-month follow-up compared with baseline. At the 3- and 6-month follow-ups, a slight majority (56% and 52%) showed improvement. At the 12-month follow-up, 72% of the autologous fibroblast group showed no improvement. Inter-rater reliability between evaluators was calculated by using kappa statistics. The correlation coefficient was 0.67 with the P-value of 0.00.

Figure 1.

Subjective assessments by blinded dermatologists of the HA and autologous fibroblast groups at all follow-ups.

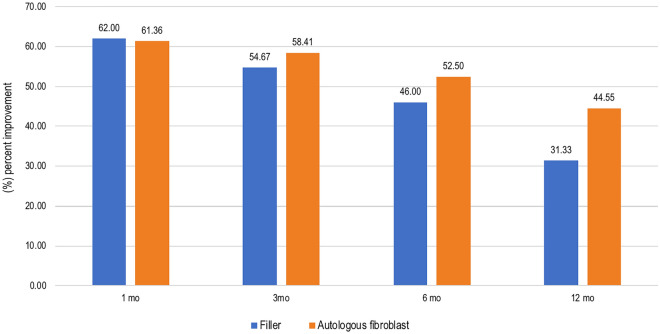

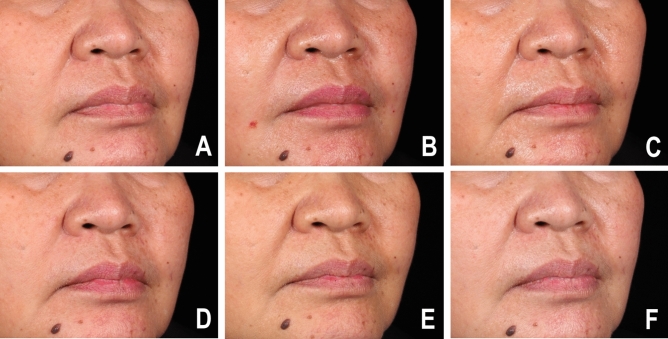

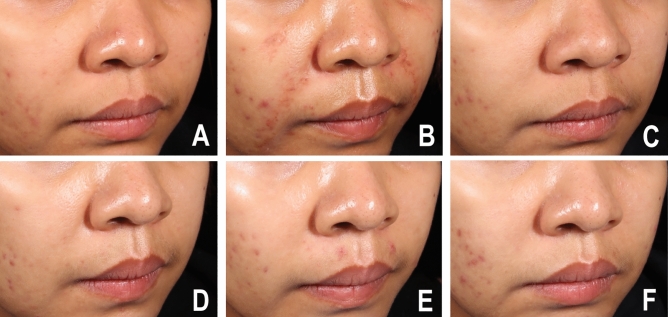

Patient self-assessment scores were recorded at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups (Fig. 2). Both treatment groups (62%, 61.36%) reported almost identical values at the 1-month follow-up (62% and 61.36%). At the 3-month follow-up, more patients in the autologous fibroblast group noticed improvement (58.41%) than in the HA group (54.67%). At the 6-month follow-up, 52.50% of the autologous fibroblast group reported improvement compared with 46% of the HA group. At the 12-month follow-up, 44.55% of the autologous fibroblast group said that there had been improvement, compared with 31.33% of the HA group. The clinical improvements to the NLFs after the HA filler and fibroblast injections are depicted in Figs. 3 and 4.

Figure 2.

Patient self-assessments of the improvement to NLFs at all follow-ups.

Figure 3.

Clinical photographs of an HA filler group participant at (A) baseline, (B) immediately after injection, (C) the 1-month follow-up, (D) the 3-month follow-up, (E) the 6-month follow-up, and (F) the 12-month follow-up.

Figure 4.

Clinical photographs of an autologous fibroblast group participant at (A) baseline, (B) immediately after injection, (C) the 1-month follow-up, (D) the 3-month follow-up, (E) the 6-month follow-up, and (F) the 12-month follow-up.

Regarding the patient pain scores, the HA group gave a score of 3.8 out of 10, whereas the autologous fibroblast group rated the injection pain as 5.36 out of 10. As to adverse reactions, 1 patient in the HA group reported a lump at the injection site. It improved after 2 months without any treatment. In the autologous fibroblast group, 1 patient experienced mild transient erythema, but it resolved spontaneously within a day. No serious adverse reactions were found during the study period.

Discussion

The aging process reduces the number of fibroblasts in the dermis and their ability to synthesize collagen and elastin15. Multiple dermal fillers for soft tissue augmentation are available on the market. One type, HA fillers, has become particularly popular in recent years16. An ideal filler should have permanence, good biocompatibility, chemical inertness, soft and easy-to-use consistency, and minimal adverse reactions17. However, even in the hands of the most experienced physicians, unwanted side effects can occur with dermal fillers. Because autologous fibroblasts offer long-term efficacy and an absence of allergic reactions, they are a natural alternative to filler materials18.

In the present study, the HA group demonstrated a significant volume improvement immediately after the HA injection and at the 1-month follow-up compared with baseline (P = 0.000 and 0.000, respectively). By contrast, the autologous fibroblast group had significant volume improvements at all follow-ups compared with baseline (P = 0.000, 0.004, 0.000, 0.000 and 0.003). These findings prove that using autologous fibroblast injections can produce sustained clinical improvements in skin that has suffered collagen degradation19. A previous study biometrically assessed the skin changes caused by autologous fibroblast injections. The research revealed significant increases in epidermal and dermal thicknesses after 6 months relative to the pretreatment values20.

In our study, most patients in the HA group had clinical improvements at the 1-month follow-up (50%) compared with baseline. However, no changes were detected at the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups. The autologous fibroblast group showed improvements only at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups.

Earlier investigations found that HA fillers in NLFs can show clinical results 1 month after injection, with satisfaction maintained at 6 months21. In our study, the HA fillers degraded over time, but the autologous fibroblast injections resulted in gradual improvements, as evidenced by our patient self-assessments. Fibroblast injections have previously been shown to require a more extended period before their effects are observed (at least 1–2 months following the completion of treatment) but without any risk of hypersensitivity reactions13. The findings of the current investigation are consistent with those of another study that used autologous fibroblasts in NLFs. That research observed sustained soft tissue augmentation at 3 months with continued clinical improvement at 6 months19. The more extended period before wrinkle improvement becomes apparent with autologous fibroblast injections than with HA fillers results from collagen deposition not using direct volume replacement. Consequently, fibroblast injections have a more gradual effect than HA fillers, which show immediate results14.

More autologous fibroblast patients than HA patients reported improvements in their NLFs at the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups. This finding is similar to the results of another study. It found that 81.6% of the patients treated with autologous fibroblasts demonstrated continued therapeutic benefits even at the 12-month follow-up13.

Other novel autologous fibroblast combinations have been formulated to produce a faster onset of results with more prolonged clinical efficacy. For instance, Jiang et al. combined autologous fibroblasts and keratin as a soft tissue filler. The researchers found that 90% of their patients had significant NLF improvements at the 1-month follow-up. In addition, the improvements were maintained in 93.8% of cases at the 24-month follow-up22. In other research, autologous fibroblasts combined with plasma gel (Fibrogel) showed persistent improvements in the infraorbital area and lower face at the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups, with minimal adverse reactions23.

Regarding adverse reactions in the present work, we had 1 patient in the autologous fibroblast group who experienced mild transient erythema. The condition resolved spontaneously within a day. Erythema is a commonly reported adverse reaction among patients injected with autologous fibroblasts14,20.

Currently, fibroblast injections are indicated for the treatment of NLFs. Autologous fibroblast treatment of NLFs is a promising option for patients. As autologous fibroblasts are not volume fillers, they are ideal for treating fine lines. On the other hand, possible disadvantages of autologous fibroblasts over HA fillers are their additional costs (which can be as high as 4 times when comparing to 1 cc of HA fillers) and the long lead time needed to harvest and culture the fibroblasts.

Our study was limited by its small sample size, and the follow-up duration might not be long enough to determine the maximum efficacy of the treatment. We recommend that further studies be conducted with larger sample sizes and longer follow-ups to establish the longevity of autologous fibroblast injection therapy.

Conclusions

Autologous fibroblast injections are safe and effective for treating NLFs. Unlike conventional dermal fillers, autologous cultured fibroblast cells are injected superficially and may require a more extended period to show improvement. They also promise sustained growth of living cells, possibly leading to a greater persistence than shown by other fillers.

Acknowledgements

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given their approval for this version to be published. Medical writing, editorial, and other assistance: The authors thank Ms Phonsuk Yamlexnoi, Ms Chutikan Kiatphansodsai, Ms Apichaya Jutaphonrakul, and Dr Surachet Sirisuthivoranunt for their assistance in recruiting subjects and managing the database. The authors express their gratitude to Mr Suthipol Udompunthurak for his assistance with the statistical analyses. The authors are also indebted to Mr David Park for English-language editing. We thank the patients who participated in the study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. R.W. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Material preparation, data collection, and analyses were performed by Y.-N.N., P.P., P.T., P.S., C.A., C.Y., Y.N., P.P., S.T., and U.P. Data interpretation and critical revision were performed by P.T., P.M., T.T., S.E., and W.M. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J.N.C.N., and all authors commented on subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research project was supported by the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University (grant number [IO] R015934006).

Data availability

The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

Financial competing interests. Saowalak Thanachaipiwat, Uraiwan Panich, and Rungsima Wanitphakdeedecha are the inventors of autologous fibroblast culture and preparation. Petty patent application has been filed by Institute for Technology and Innovation Management (INT), Mahidol University at the Department of Intellectual Property since March 10, 2022 with application number of 2203000625. The status of the application is now under reviewed. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to any aspect of this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Puizina-Ivić N. Skin aging. Acta Dermatovenerol. Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17(2):47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khavkin J, Ellis DA. Aging skin: Histology, physiology, and pathology. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2011;19(2):229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin JW, Kwon SH, Choi JY, et al. Molecular mechanisms of dermal aging and antiaging approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(9):2126. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu MH, Beynet DP, Gharavi NM. Overview of deep dermal fillers. Facial Plast. Surg. 2019;35(3):224–229. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1688843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann L, Kaufman J, Saghari S. Collagen fillers. Dermatol. Ther. 2006;19(3):134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JE, Sykes JM. Hyaluronic acid fillers: History and overview. Facial Plast. Surg. 2011;27(6):523–528. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiang YZ, Pierone G, Al-Niaimi F. Dermal fillers: Pathophysiology, prevention and treatment of complications. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017;31(3):405–413. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang CJ, Chon BH, Perry JD. Blindness after filler injection: Mechanism and treatment. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2021;29(2):359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodward J, Khan T, Martin J. Facial filler complications. Facial Plast Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2015;23(4):447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groen JW, Krastev TK, Hommes J, Wilschut JA, Ritt M, van der Hulst R. Autologous fat transfer for facial rejuvenation: A systematic review on technique, efficacy, and satisfaction. Plast Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 2017;5(12):e1606. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park SW, Woo SJ, Park KH, Huh JW, Jung C, Kwon OK. Iatrogenic retinal artery occlusion caused by cosmetic facial filler injections. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2012;154(4):653–662.e651. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt C. FDA approves first cell therapy for wrinkle-free visage. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29(8):674–675. doi: 10.1038/nbt0811-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss RA, Weiss MA, Beasley KL, Munavalli G. Autologous cultured fibroblast injection for facial contour deformities: A prospective, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial. Dermatol. Surg. 2007;33(3):263–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith SR, Munavalli G, Weiss R, Maslowski JM, Hennegan KP, Novak JM. A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of autologous fibroblast therapy for the treatment of nasolabial fold wrinkles. Dermatol. Surg. 2012;38(7 Pt 2):1234–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon KC, Lee HS, Han SK, Chung HY. Correcting nasojugal groove with autologous cultured fibroblast injection: A pilot study. Aesthet. Plast Surg. 2018;42(3):815–824. doi: 10.1007/s00266-017-1044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fallacara A, Manfredini S, Durini E, Vertuani S. Hyaluronic acid fillers in soft tissue regeneration. Facial Plast Surg. 2017;33(1):87–96. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1597685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold MH, Sadick NS. Optimizing outcomes with polymethylmethacrylate fillers. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2018;17(3):298–304. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng W, Zhang S, Liu D, Chai M, Wang J, Zhao Y. Preclinical safety studies on autologous cultured human skin fibroblast transplantation. Cell Transpl. 2014;23(1):39–49. doi: 10.3727/096368912X659844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.West TB, Alster TS. Autologous human collagen and dermal fibroblasts for soft tissue augmentation. Dermatol. Surg. 1998;24(5):510–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nilforoushzadeh MA, Zare S, Farshi S, et al. Clinical, biometric, and ultrasound assessment of the effects of the autologous fibroblast cells transplantation on nasolabial fold wrinkles. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021;20(10):3315–3323. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sood V, Nanda S. Patient satisfaction with hyaluronic acid fillers for improvement of the nasolabial folds in type IV & V skin. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2012;11(1):78–81. doi: 10.1007/s12663-011-0256-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang H, Guan Y, Yang J, Zhang J, Zhang Q, Chen Z. Using new autologous tissue filler improved nasolabial folds-single-armed pilot study. Aesthet. Plast Surg. 2021;45(6):2920–2927. doi: 10.1007/s00266-021-02608-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oram, Y., Deniz Akkaya, A., Güneren, E., Turgut, G. A novel autologous dermal filler based on cultured fibroblasts and plasma gel for facial wrinkles: Long term results. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 1–8 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.