This randomized clinical trial investigates if patients who undergo nonpalliative surgery for abdominal cancer should receive early specialist palliative care.

Key Points

Question

Should patients undergoing nonpalliative surgery for cancer receive early specialist palliative care?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 235 adults undergoing nonpalliative abdominal operations for cancer, there was no evidence that a specialist palliative care intervention improved quality of life, time alive out of the hospital, or survival.

Meaning

In this trial, early specialist palliative care did not significantly improve outcomes for patients undergoing abdominal operations for cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Specialist palliative care benefits patients undergoing medical treatment of cancer; however, data are lacking on whether patients undergoing surgery for cancer similarly benefit from specialist palliative care.

Objective

To determine the effect of a specialist palliative care intervention on patients undergoing surgery for cure or durable control of cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a single-center randomized clinical trial conducted from March 1, 2018, to October 28, 2021. Patients scheduled for specified intra-abdominal cancer operations were recruited from an academic urban referral center in the Southeastern US.

Intervention

Preoperative consultation with palliative care specialists and postoperative inpatient and outpatient palliative care follow-up for 90 days.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The prespecified primary end point was physical and functional quality of life (QoL) at postoperative day (POD) 90, measured by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G) Trial Outcome Index (TOI), which is scored on a range of 0 to 56 with higher scores representing higher physical and functional QoL. Prespecified secondary end points included overall QoL at POD 90 measured by FACT-G, days alive at home until POD 90, and 1-year overall survival. Multivariable proportional odds logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to test the hypothesis that the intervention improved each of these end points relative to usual care in an intention-to-treat analysis.

Results

A total of 235 eligible patients (median [IQR] age, 65.0 [56.8-71.1] years; 141 male [60.0%]) were randomly assigned to the intervention or usual care group in a 1:1 ratio. Specialist palliative care was received by 114 patients (97%) in the intervention group and 1 patient (1%) in the usual care group. Adjusted median scores on the FACT-G TOI measure of physical and functional QoL did not differ between groups (intervention score, 46.77; 95% CI, 44.18-49.04; usual care score, 46.23; 95% CI, 43.08-48.14; P = .46). Intervention vs usual care group odds ratio (OR) was 1.17 (95% CI, 0.77-1.80). Palliative care did not improve overall QoL measured by the FACT-G score (intervention vs usual care OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.75-1.58), days alive at home (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.69-1.11), or 1-year overall survival (hazard ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.50-1.88).

Conclusions and Relevance

This randomized clinical trial showed no evidence that early specialist palliative care improves the QoL of patients undergoing nonpalliative cancer operations.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03436290

Introduction

In the past 2 decades, cancer care has evolved to include specialist palliative care (ie, consultation with a palliative care specialist) concurrent with tumor-directed therapies, rather than after these therapies fail. In patients with advanced malignancies, specialist palliative care initiated concurrently with chemotherapy improves patient quality of life (QoL), reduces anxiety and depression, and in some studies, prolongs survival compared with standard oncologic care.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 These data led the American Society of Clinical Oncology to recommend including specialist palliative care along with active treatment for advanced malignancies.10

The next step in this field’s evolution is to determine the role of specialist palliative care for patients undergoing nonpalliative surgery for cancer. Many operations for gastrointestinal, urologic, and gynecologic malignancies impose burdensome recovery and have high rates of cancer recurrence.11,12,13,14 Despite the burdens of treatment and chances of recurrence, specialist palliative care is typically not delivered to these patients until the end of life, if at all.15,16,17,18 There is a dearth of evidence on the effectiveness of specialist palliative care delivered along with tumor-directed surgery. A recent expert consensus panel convened by the National Institutes of Health advocated for trials of specialist palliative care interventions among oncologic surgical patients to fill this evidence gap.19

To address this need, we conducted the Surgery for Cancer With Option of Palliative Care Expert (SCOPE) trial, a single-center, randomized clinical trial (RCT) of a specialist palliative care intervention initiated preoperatively and continued postoperatively for patients undergoing major operations for abdominal malignancies with intent to cure or provide durable oncologic control. Based on the meta-analytic finding that specialist palliative care improves QoL in medical oncology trials, we hypothesized that patients receiving the intervention would have higher postoperative physical and functional QoL compared with patients receiving usual care (ie, surgery without specialist palliative care consultation).20 Our secondary hypotheses were that the intervention would improve overall postoperative QoL, increase the time patients spent alive at home postoperatively, and improve overall survival, again based on analogous results from palliative care trials and meta-analyses in medical populations.1,2,4,20,21

Methods

Trial Design and Population

We conducted this assessor-blind RCT at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, a tertiary referral center, with enrollment from March 1, 2018, through October 28, 2021. The institutional review board approved the protocol (Supplement 1). The study time line is available in the eAppendix in Supplement 2. The trial procedures and the a priori–specified statistical analysis plan have been published.22,23 The trial was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the trial. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines.

Patients were eligible if they were at least 18 years old and were scheduled for 1 of the following 8 operations with the intent to provide cure or durable oncologic control of a suspected or confirmed malignancy: (1) partial or total gastrectomy, (2) partial hepatectomy, (3) partial or total pancreatectomy, (4) partial or total colectomy or proctectomy, (5) radical cystectomy, (6) pelvic exenteration, (7) cytoreductive surgery (CRS) after neoadjuvant therapy for ovarian or endometrial cancer, or (8) CRS and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Compared with the other operations, colectomy and proctectomy cause relatively lower burdens of morbidity and mortality; therefore, patients undergoing colectomy or proctectomy had to meet 1 of the following additional inclusion criteria to make them more comparable with the other patients: (1) age at least 65 years, (2) presence of metastatic disease, and/or (3) local invasion requiring resection of other viscera or body wall. Details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in the trial protocol (Supplement 1). After obtaining written informed consent, patients were randomly assigned to receive a specialist palliative care intervention or usual care. Once enrolled and randomized, patients were included in the study even if the clinical situation changed between enrollment and the scheduled operative date resulting in change or cancellation of operation.

Trial-Group Assignment and Intervention

Patients were approached by research staff (A.H., E.M.) either in person at their preoperative clinic visit or by phone based on review of the surgical schedule. After the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, all patient enrollment was conducted by phone. After consent, the patients were randomly assigned to the intervention or usual care group in a 1:1 ratio using a permuted-block randomization sequence with blocks of 6 and 8, stratified by surgical specialty and implemented using the Research Electronic Data Capture randomization module.24 At enrollment, the study coordinator also collected baseline demographic and psychometric data. Participants identified their race and ethnicity from options defined by the investigators, which included the racial and ethnic categories defined by the US Census (ie, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and White) as well as an option for other race or ethnicity for patients who did not identify as one of these racial categories. Race and ethnicity were collected to describe the demographic makeup of the study population.

The specialist palliative care intervention comprised 4 elements: (1) a preoperative consultation with a board-certified palliative care physician or nurse practitioner in clinic or by phone, (2) inpatient specialist palliative care physician or nurse practitioner visits at least twice weekly during the postoperative hospital stay, (3) 3 follow-up clinic visits or phone calls with a palliative care specialist between hospital discharge and postoperative day (POD) 90; and (4) an inpatient specialist palliative care visit whenever the patient was readmitted to the hospital. Initial consultations generally lasted 20 to 60 minutes, whereas subsequent encounters usually lasted 10 to 30 minutes. The content of these encounters was specified in an intervention manual, and fidelity was assessed by review of the documentation by the palliative care physician or nurse practitioner documentation (eAppendix in Supplement 2). In both inpatient and outpatient settings, palliative care physicians or nurse practitioners provided active medical management of issues they identified in consultation with the patients’ surgical teams and were available for follow-up for any symptoms. After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, all outpatient encounters were conducted by phone.

Outcome Assessments

Timing of end points was anchored so that day 0 was the date of operation or the date that the operation was originally scheduled if the patient’s clinical condition changed and they did not have an operation. All outcomes were assessed by phone by assessors who were distinct from the rest of the study staff and who remained blinded to each patient’s treatment assignment. Assessors collected 90-day patient-reported and caregiver-reported outcomes beginning on POD 90 and would continue contacting patients for up to 60 days to collect these outcomes. The primary outcome was 90-day physical and functional QoL as measured by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G) Trial Outcome Index (TOI). The FACT-G assesses QoL across 4 domains (physical, social/family, emotional, and functional). The TOI represents the sum of the scores on the physical and functional subscales.25

Secondary outcomes included 90-day overall QoL as assessed by the FACT-G total score, days alive at home on POD 1 to 90 (defined as days that a patient was alive, not admitted to a health care facility, and did not have an emergency department visit, which was assessed by patient report on or about POD 30, 60, and 90 and corroborated by medical record review), and overall survival at 1 year. Exploratory outcomes at 90 days included anxiety as measured by the Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Information System (PROMIS) Anxiety 6a short form, depression as measured by the PROMIS Depression 6a short form, caregiver burden as measured by the Zarit Burden Interview administered to the patient’s primary caregiver, and the size of the patient’s life space as measured by the Life-Space Assessment.26,27,28 A study oncologist (B.F.T.) examined patient records to determine whether adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy would be recommended if the patient’s performance status permitted it. In the subset of patients for whom adjuvant therapy would be recommended, time from surgery to initiation of adjuvant therapy (based on patient report) was an exploratory outcome.

Statistical Analysis

This trial was designed to evaluate 196 patients (98 per group) to have 80% power to detect clinically relevant differences, at least 3.60 points difference between groups for the FACT-G TOI score, and 7.24 points difference in the FACT-G total score (assuming an SD of 9 and 18.10 for the FACT-G TOI score and the FACT-G total score, respectively).25 Because the primary outcome was obtained at 90 days, power for this trial was estimated based on those who would not be lost to follow-up or deceased. We had conservatively estimated that a very small proportion would be deceased, and 20% would be lost to follow-up; therefore, we planned to randomly assign 236 patients to treatment groups and to achieve follow-up with 196 patients.

All outcomes were analyzed using univariate methods and multivariable regression methods adjusting for covariates: type of cancer, baseline frailty measured by risk analysis index, age at randomization, and sex. For outcomes with baseline measures, the baseline measures were also adjusted for in the models. Adjusted analyses were considered the primary analyses.

Proportional odds logistic regression was used for analyzing the primary outcome, physical and functional QoL, and other continuous secondary and exploratory outcomes at 90 days. Adjusted medians and odds ratios (ORs) along with their 95% CIs were reported as model results. Cox proportional hazards regression and Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used for analyzing 1-year overall survival. Fine-Gray competing risk regression and cumulative incidence curves were used for analyzing the time from surgery to initiation of adjuvant therapy, considering death as the competing risk. For time-to-event models, hazard ratios (HRs) along with their 95% CIs were reported as model results.

We analyzed all data using an intention-to-treat approach. Differential follow-up between the 2 randomization arms at 90 days were evaluated using a Kaplan-Meier curve for time to dropout. All patients were included for the analysis of 1-year overall survival and days alive at home in 90 days.

Missing covariate data were imputed using model-based single imputation because the percentage of missing data was low (<3%). The level of statistical significance for all end points was a 2-sided P value < .05, and no multiple comparison adjustments were made for secondary and exploratory outcomes, per the statistical analysis plan. All statistical analyses were conducted by the trial’s biostatistics team (R.R., O.M.O.) using statistical software R, version 4.0.5 (R Project for Statistical Computing) and in accordance with the statistical analysis plan published in April 2021.23

Results

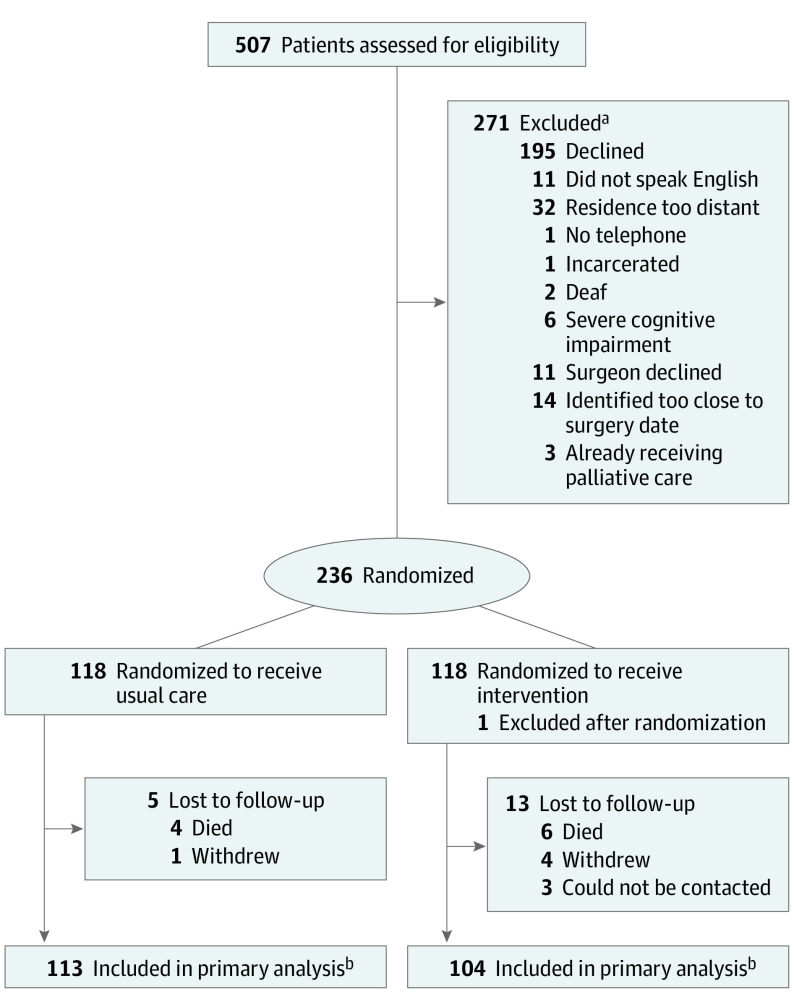

Of 507 potentially eligible patients, 236 consented to participate and were randomly assigned to treatment groups (118 to usual care, 118 to intervention). After randomization, we discovered that 1 patient in the intervention group met an exclusion criterion (receiving specialist palliative care before enrollment), resulting in postrandomization exclusion. The CONSORT patient randomization diagram is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Patient Enrollment and Follow-up: Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Diagram.

FACT-G indicates Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; TOI, Trial Outcome Index.

aPatients could meet multiple exclusion criteria; individual counts do not sum to total.

bPatients who were fully or partially assessed were listed in the CONSORT diagram. Patients whose partially missing data were 50% or greater in the related FACT-G domains were not included in the analysis cohort as the FACT-G TOI and total scores could not be computed based on the FACT-G score computation guidelines.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 235 included participants. The median (IQR) age was 65.0 (56.8-71.1) years, 141 were male (60.0%), and 94 were female (40.0%). Patients self-identified with the following race and ethnicity categories: 1 Asian (0.4%), 9 Black (3.8%), 2 Hispanic (0.9%), 224 White (95.3%), and 1 other race or ethnicity (0.4%). The most common operations were radical cystectomy (87 [37%]), partial or total pancreatectomy (36 [15%]), and partial hepatectomy (31 [13%]). The most common types of malignancies were bladder cancer (86 [37%]), colorectal cancer (57 [24%]), and pancreatic cancer (20 [9%]). Most patients (139 [59%]) received neoadjuvant therapy before their operations. Patients in the intervention and usual care groups had similar rates of having their operations cancelled or aborted and of major postoperative complications (eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 2).

Table 1. Patient Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Control group, No. (%) (n = 118) | Intervention group, No. (%) (n = 117) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 66.60 (57.80-71.60) | 62.30 (56.60-69.30) |

| Female | 48 (41) | 46 (39) |

| Male | 70 (59) | 71 (61) |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Black | 4 (3) | 5 (4) |

| White | 113 (96) | 111 (95) |

| Othera | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic ethnicity | 116 (98) | 117 (100) |

| Currently married | 88 (75) | 85 (73) |

| Highest education level | ||

| High school or less | 24 (20) | 31 (26) |

| Some college | 28 (24) | 27 (23) |

| College degree | 48 (41) | 42 (36) |

| Postgraduate | 17 (14) | 17 (15) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Annual income | ||

| <$50 000 | 35 (30) | 36 (31) |

| $50 000-$99 999 | 37 (31) | 42 (36) |

| ≥$100 000 | 36 (31) | 30 (26) |

| Unknown | 10 (8) | 9 (8) |

| Cancer type | ||

| Bladder | 43 (36) | 43 (37) |

| Colorectal | 30 (25) | 27 (23) |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 7 (6) | 13 (11) |

| Appendiceal (including LAMN and HAMN) | 7 (6) | 9 (8) |

| Gastric | 5 (4) | 5 (4) |

| Ovarian | 3 (3) | 5 (4) |

| Other malignancies | 18 (15) | 9 (8) |

| Benign disease | 5 (4) | 6 (5) |

| Cancer stage | ||

| 0/Benign disease | 7 (6) | 6 (5) |

| I | 15 (13) | 9 (8) |

| II | 26 (22) | 28 (24) |

| III | 33 (28) | 33 (28) |

| IV/Metastatic/recurrent | 37 (31) | 41 (35) |

| Scheduled operation | ||

| Radical cystectomy | 44 (37) | 43 (37) |

| Partial or total pancreatectomy | 17 (14) | 19 (16) |

| Partial hepatectomy | 14 (12) | 17 (15) |

| CRS/HIPEC | 16 (14) | 12 (10) |

| Colectomy/proctectomy | 11 (9) | 11 (9) |

| Partial or total gastrectomy | 8 (7) | 6 (5) |

| CRS | 4 (3) | 6 (5) |

| Colectomy and partial hepatectomy | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Pelvic exenteration | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Received neoadjuvant therapy | 65 (55) | 74 (63) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 3 (2-6) | 3 (2-6) |

| RAI frailty score, median (IQR) | 37 (35-42) | 37 (35-41) |

| ASA class | ||

| II | 17 (14) | 18 (15) |

| III | 98 (83) | 95 (81) |

| IV | 3 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Not recorded | 0 | 1 (1) |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CRS, cytoreductive surgery; HAMN, high-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm; HIPEC, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy; LAMN, low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm; RAI, risk analysis index.

Other race not stated to avoid potential identification of study participant.

Table 2 compares the receipt of specialist palliative care between the intervention group and the control (usual care) group. Of the 117 intervention group patients, 114 (97%) received specialist palliative care, whereas only 1 control group patient (1%) received specialist palliative care before POD 90. Among the intervention group, 77 patients (66%) received all the elements of the intervention as prescribed by the intervention manual.

Table 2. Specialist Palliative Care Delivery.

| Characteristic | Control group, No. (%) (n = 118) | Intervention group, No. (%) (n = 117) |

|---|---|---|

| Received any palliative care encounter | 1 (1) | 114 (97) |

| Received at least 1 outpatient palliative care encounter | 0 | 114 (97) |

| No. of outpatient encounters among those with at least 1, median (IQR) | 0 | 4 (3-4) |

| Received at least 1 inpatient palliative care encounter | 1 (1) | 110 (94) |

| No. of inpatient encounters among those with at least 1, median (IQR) | 2 (2-2) | 2 (1-3) |

| Received all elements of intervention per manual | NA | 77 (66) |

| Received preoperative intervention per manual | NA | 110 (94) |

| Received postoperative inpatient intervention per manual | NA | 106 (91) |

| Received postoperative outpatient intervention per manual | NA | 85 (73) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

The results for the primary, secondary, and exploratory outcomes appear in Table 3,25,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 along with their baseline values (where applicable) and estimates of the minimal clinically important differences (MCID) from the literature. The primary outcome, FACT-G TOI, did not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups (intervention score, 46.77; 95% CI, 44.18-49.04; usual care score, 46.23; 95% CI, 43.08-48.14; P = .46). Intervention vs usual care group OR was 1.17 (95% CI, 0.77-1.80) (Figure 2). We did not detect a statistically significant or clinically meaningful difference between groups in any secondary or exploratory outcomes. Palliative care did not improve overall QoL measured by the FACT-G score (intervention vs usual care OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.75-1.58), days alive at home (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.69-1.11), or 1-year overall survival (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.50-1.88). The cumulative incidence curves for time to initiation of adjuvant therapy are given in the eFigure in Supplement 2 for the 107 patients judged appropriate for adjuvant therapy (55 in the usual care group and 52 in the intervention group).

Table 3. Primary, Secondary, and Exploratory Outcomes.

| Outcome | Instrument name; score range; and interpretation MCID estimate | Unadjusted, median (IQR) | Adjusted OR or HR (95% CI) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care group | Intervention group | ||||||

| Baseline | 90 d | Baseline | 90 d | ||||

| Primary outcome | |||||||

| Physical and functional QoL | FACT-G TOI; scoring: 0-56, higher is better; MCID, 2-323 | 44.00 (38.00-51.00) | 45.00 (39.00-50.00) | 43.00 (34.80-50.00) | 45.00 (36.20-50.00) | 1.17 (0.77-1.80)a | .46 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||

| Overall QoL | FACT-G; scoring: 0-108, higher is better; MCID: 3-723 | 87.40 (76.00-95.00) | 91.00 (79.50-98.30) | 85.00 (72.90-94.00) | 88.00 (72.80-99.00) | 1.09 (0.75-1.58)a | .66 |

| Days alive at home | Scoring: 0-90, higher is better; MCID: 1.527,28 |

NA | 83 (79-85) | NA | 84 (76-86) | 0.87 (0.69-1.11)a | .26 |

| Overall survival (1 year) | Lower hazard is better | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.97 (0.50-1.88)b | .92 |

| Exploratory outcomes | |||||||

| Anxiety | PROMIS anxiety T score; scoring: 39.1-82.7, lower is better; MCID: 3-529,30,31 |

51.10 (45.70-55.80) | 46.00 (39.10-54.20) | 52.80 (46.00-59.30) | 46.20 (39.10-55.00) | 0.98 (0.65-1.50)a | .94 |

| Depression | PROMIS depression T score; scoring: 38.4-80.3, lower is better; MCID: 3-529,30,31 | 46.10 (38.40-53.60) | 44.90 (38.40-52.20) | 48.50 (38.40-53.80) | 47.40 (38.40-54.50) | 0.92 (0.58-1.48)a | .74 |

| Caregiver burden | Zarit Burden Interview; scoring: 0-48, lower is better; MCID: 4.432,33 |

NA | 7.00 (2.50-12.00) | NA | 6.00 (2.00-13.25) | 0.97 (0.61-1.53)a | .90 |

| Life space | Life Space Assessment; scoring: 0-120, higher is better; MCID: 2334 |

78.00 (68.00-100.00) | 78.00 (56.00-92.00) | 78.00 (62.00-93.50) | 70.00 (49.50-87.00) | 0.76 (0.49-1.17)a | .22 |

| Time to adjuvant therapy | Higher hazard is better | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.13 (0.79-1.63)b | .51 |

Abbreviations: FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; HR, hazard ratio; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Information System; QoL, quality of life; TOI, Trial Outcome Index.

OR that an intervention patient has a higher score than a usual care patient.

HR of intervention group to usual care group.

Figure 2. Primary and Secondary Study Outcomes.

A, Physical and functional quality of life at 90 days. B, Overall quality of life at 90 days. C, Days alive at home through 90 days. D, Overall survival at 1 year. FACT-G indicates Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; TOI, Trial Outcome Index.

For the overall cohort, the median (IQR) baseline scores on the FACT-G TOI and FACT-G total score were 43.00 (36.00-50.00) and 86.00 (74.80-94.60), respectively, both of which are higher than what is reported for the general US population.37 Changes in these outcomes from baseline to 90 days were smaller than the MCID, as were the changes in anxiety, depression, and life space from baseline to POD 90 (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Prior studies have similarly shown minimal changes in QoL from baseline to POD 90 in patients undergoing major cancer operations.38,39,40,41 Thus, this patient population had relatively high baseline QoL, and by POD 90, QoL had mostly recovered to near the baseline level. These findings suggest that these surgical patients likely have low palliative care needs compared with other cancer populations.

Discussion

The strong evidence of the benefits of specialist palliative care for patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer begs the question whether patients undergoing surgery for cancer would similarly benefit from specialist palliative care, and findings from this RCT answer that question. This investigation did not demonstrate any meaningful benefit of the specialist palliative care intervention for patients undergoing major nonpalliative cancer operations. The primary outcome, physical and functional QoL at 90 days, was almost identical between the intervention and usual care groups. Similarly, we detected no statistically significant or clinically meaningful differences between the intervention and usual care groups for any secondary or exploratory outcome. These results do not support routine integration of palliative care specialists into the care of these surgical patients.

Given the study’s strengths, the most likely explanation for these results is that this intervention does not improve these outcomes for this patient population. We delivered the intervention consistently and with high fidelity among the patients in the intervention group. At the same time, delivery of specialist palliative care to the usual care group was almost nonexistent. Thus, the lack of differences in outcomes between the groups did not reflect a failure to separate the groups with respect to receiving the intervention. Moreover, the study achieved follow-up rates of over 95% for surviving patients, and analysis did not indicate that the groups were statistically different at POD 90 with respect to death or attrition, making it unlikely that differential response rates influenced these results. We exceeded the follow-up estimates assumed in our power calculations. Outcomes assessors remained blinded to treatment assignment, minimizing the risk of bias in the collection of outcomes.

It is important to interpret these results in light of the burgeoning evidence on specialist palliative care interventions for patients with cancer. Based on RCT evidence over the last 15 years, specialist palliative care has moved further upstream in the cancer care continuum: from an alternative to active treatment, to a complement for noncurative treatment, to an adjunct for curative intent treatment. Landmark RCTs by Bakitas et al1 in 2009 and Temel et al2 in 2010 demonstrated the benefits of specialist palliative care for patients who are undergoing active treatment (ie, chemotherapy) for metastatic solid tumors. These results triggered further research on palliative care interventions for patients with cancer: a 2016 meta-analysis20 included 23 RCTs of palliative care interventions, mostly in patients with advanced cancer, and found that palliative care interventions consistently improved QoL, symptom burden, advanced care planning, and patient and caregiver satisfaction, while simultaneously reducing health care utilization. The SCOPE trial aimed to answer whether specialist palliative care should again move upstream in the cancer care continuum to coincide with nonpalliative surgical treatment of solid tumors of the abdomen. The results of the trial suggest that such a shift would not be a wise use of limited specialist palliative care resources.

Limitations

Interpretation of these results must be tempered by the study’s limitations. The intervention may have improved aspects of the patient experience not measured by the study, but the clinical significance of such potentially unmeasured benefits is difficult to articulate because the intervention did not improve QoL, mood, life space, or survival, nor did it reduce caregiver burden or health care utilization. These patients may also be too early in their cancer trajectory to benefit from specialist palliative care, and a later intervention may benefit this population. An additional limitation is that the results of this single-center study may not be generalizable to other settings, especially because our population underrepresents patients in ethnic and racial minority groups and overrepresents those with higher education and ability to travel for care. Finally, this heterogenous patient population may not have had sufficient palliative care needs to benefit from the intervention, whereas other surgical populations may benefit. The recently completed multicenter Perioperative Palliative Care Surrounding Cancer Surgery for Patients and Their Family Members (PERIOP-PC) trial of specialist palliative care for patients undergoing resections of foregut malignancies will address several of these limitations of the SCOPE trial.42

Conclusions

The results of this RCT suggest that surgeons, anesthesiologists, and perioperative care teams adequately meet the palliative care needs for most of their patients undergoing major cancer operations. Some of these patients may have more needs and would benefit from specialist palliative care, and the lack of adverse effects demonstrated in this study should reassure referring clinicians that specialist palliative care is unlikely to distress or harm patients. Although it is important to increase the availability of specialist palliative care to populations proven to benefit from it, it is equally important to make sure that specialist palliative care is available when the clinical situation calls for it, and surgeons should not hesitate to request the assistance of palliative care specialists when their clinical judgment dictates. Future studies should look to surgical populations, such as patients undergoing organ transplant, with higher symptom burdens for whom specialist palliative care could offer benefit.

Trial Protocol

eAppendix.

eFigure. Cumulative Incidence of Initiation of Adjuvant Therapy

eTable 1. Operative Details

eTable 2. Cancer Type and Stage by Operation

eTable 3. Change in Patient Reported Outcomes From Baseline to 90 Days in 235 Included Patients

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741-749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721-1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early vs delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1438-1445. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):834-841. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, et al. Emergency department-initiated palliative care in advanced cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):591-598. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrell B, Sun V, Hurria A, et al. Interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(6):758-767. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun V, Grant M, Koczywas M, et al. Effectiveness of an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention for family caregivers in lung cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(20):3737-3745. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc TW, Kavanaugh A, et al. Effectiveness of integrated palliative and oncology care for patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):238-245. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96-112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bengtsson A, Andersson R, Ansari D. The actual 5-year survivors of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma based on real-world data. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):16425. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73525-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cashin P, Sugarbaker PH. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for colorectal and appendiceal peritoneal metastases: lessons learned from PRODIGE 7. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12(suppl 1):S120-S128. doi: 10.21037/jgo-2020-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuh B, Wilson T, Bochner B, et al. Systematic review and cumulative analysis of oncologic and functional outcomes after robot-assisted radical cystectomy. Eur Urol. 2015;67(3):402-422. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, noninferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9990):249-257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62223-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heller DR, Jean RA, Chiu AS, et al. Regional differences in palliative care utilization among geriatric colorectal cancer patients needing emergent surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23(1):153-162. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-3929-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheffield KM, Boyd CA, Benarroch-Gampel J, Kuo YF, Cooksley CD, Riall TS. End-of-life care in Medicare beneficiaries dying with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(21):5003-5012. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefkowits C, Binstock AB, Courtney-Brooks M, et al. Predictors of palliative care consultation on an inpatient gynecologic oncology service: are we following ASCO recommendations? Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133(2):319-325. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yefimova M, Aslakson RA, Yang L, et al. Palliative care and end-of-life outcomes following high-risk surgery. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(2):138-146. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lilley EJ, Cooper Z, Schwarze ML, Mosenthal AC. Palliative care in surgery: defining the research priorities. Ann Surg. 2018;267(1):66-72. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2104-2114. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quinn KL, Shurrab M, Gitau K, et al. Association of receipt of palliative care interventions with health care use, quality of life, and symptom burden among adults with chronic noncancer illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324(14):1439-1450. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.14205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shinall MC Jr, Hoskins A, Hawkins AT, et al. A randomized trial of a specialist palliative care intervention for patients undergoing surgery for cancer: rationale and design of the Surgery for Cancer with Option of Palliative Care Expert (SCOPE) Trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):713. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3754-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orun OM, Shinall MC Jr, Hoskins A, et al. Statistical analysis plan for the Surgery for Cancer with Option of Palliative Care Expert (SCOPE) trial: a randomized controlled trial of a specialist palliative care intervention for patients undergoing surgery for cancer. Trials. 2021;22(1):314. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05256-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy (FACIT) measurement system: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker PS, Bodner EV, Allman RM. Measuring life-space mobility in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(11):1610-1614. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652-657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith AW, Jensen RE. Beyond methods to applied research: realizing the vision of PROMIS®. Health Psychol. 2019;38(5):347-350. doi: 10.1037/hea0000752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferguson MT, Kusre S, Myles PS. Minimal clinically important difference in days at home up to 30 days after surgery. Anaesthesia. 2022;77(2):196-200. doi: 10.1111/anae.15623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myles PS, Shulman MA, Heritier S, et al. Validation of days at home as an outcome measure after surgery: a prospective cohort study in Australia. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e015828. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bryant AL, Deal AM, Battaglini CL, et al. The effects of exercise on patient-reported outcomes and performance-based physical function in adults with acute leukemia undergoing induction therapy: Exercise and Quality of Life in Acute Leukemia (EQUAL). Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17(2):263-270. doi: 10.1177/1534735417699881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, Stump TE, Kean J, Talib TL, Haggstrom DA, Monahan PO. PROMIS 4-item measures and numeric rating scales efficiently assess SPADE symptoms compared with legacy measures. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;115:116-124. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yost KJ, Eton DT, Garcia SF, Cella D. Minimally important differences were estimated for 6 patient-reported outcomes measurement information system—cancer scales in advanced-stage cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(5):507-516. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghahramani N, Chinchilli VM, Kraschnewski JL, Lengerich EJ, Sciamanna CN. Improving caregiver burden by a peer-led mentoring program for caregivers of patients with chronic kidney disease: randomized controlled trial. J Patient Exp. 2022;9:23743735221076314. doi: 10.1177/23743735221076314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sloan JA. Assessing the minimally clinically significant difference: scientific considerations, challenges and solutions. COPD. 2005;2(1):57-62. doi: 10.1081/COPD-200053374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanzino D, Sander E, Mansch B, Jones A, Gill M, Hollman J. Life space assessment in spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2016;22(3):173-182. doi: 10.1310/sci2203-173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J, Webster K, Cella D. General population and cancer patient norms for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G). Eval Health Prof. 2005;28(2):192-211. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sommer MS, Vibe-Petersen J, Stærkind MB, et al. Early initiated postoperative rehabilitation enhances quality of life in patients with operable lung cancer: Secondary outcomes from a randomized trial. Lung Cancer. 2020;146:285-289. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Juszczak K, Gastecka A, Adamowicz J, Adamczyk P, Pokrywczyńska M, Drewa T. Health-related quality of life is not related to laparoscopic or robotic technique in radical cystectomy. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2020;29(7):857-863. doi: 10.17219/acem/121937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moaven O, Votanopoulos KI, Shen P, et al. Health-related quality of life after cytoreductive surgery/HIPEC for mucinous appendiceal cancer: results of a multicenter randomized trial comparing oxaliplatin and mitomycin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(3):772-780. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-08064-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu JB, Tam V, Zenati MS, et al. Association of robotic approach with patient-reported outcomes after pancreatectomy: a prospective cohort study. HPB (Oxford). 2022;24(10):1659-1667. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2022.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aslakson RA, Chandrashekaran SV, Rickerson E, et al. A multicenter, randomized controlled trial of perioperative palliative care surrounding cancer surgery for patients and their family members (PERIOP-PC). J Palliat Med. 2019;22(S1):44-57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eAppendix.

eFigure. Cumulative Incidence of Initiation of Adjuvant Therapy

eTable 1. Operative Details

eTable 2. Cancer Type and Stage by Operation

eTable 3. Change in Patient Reported Outcomes From Baseline to 90 Days in 235 Included Patients

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement