Abstract

Background

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive lymphoma that arises from malignant transformation of B lymphocytes. Outcome of patients with DLBCL has been significantly improved by rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) therapy, which is regarded “gold standard” of DLBCL therapy. It is unfortunate that febrile neutropenia, a decrease of the neutrophil count in the blood accompanying fever, is one of the most common complications that DLBCL patients receiving R-CHOP regimen experience. Given the critical role of neutrophils against bacterial and fungal infections, neutropenia could be deadly. While the association between R-CHOP therapy and neutropenia has been well-established, the negative effect of DLBCL cells on the survival of neutrophils has not been clearly understood. Our previous study have shown that conditioned medium (CM) derived from Ly1 DLBCL cells induces apoptosis in murine neutrophils ex vivo. Additionally, Ly1 CM and doxorubicin synergize to further enhance apoptotic rate in neutrophils, possibly contributing to neutropenia in DLBCL patients.

Objective

We investigated the mechanism and genes that regulate neutrophil apoptosis induced by secretome of DLBCL cells, which would give insight into the potential role of DLBCL in neutropenia.

Method

Murine neutrophils were isolated from bone marrow in C57BL6/J mice using flow cytometry. QuantSeq 3' mRNA-sequencing was conducted on neutrophils following exposure to CM derived from Ly1 DLBCL cells or murine bone marrow cells (control). Quantseq 3′mRNA sequencing data were aligned to identify differentially expressed mRNAs. Next, the expression of genes related to neutrophil apoptosis and proliferation were analyzed and Gene classification and ontology were analyzed.

Result

We identified 1196 (198 upregulated and 998 downregulated) differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Ly1 DLBCL co-culture group compared to the control group. The functional enrichment analyses of DEGs in co-culture group revealed significant enriched in apoptosis process, and immune system process in gene ontology and the highly enriched pathway of various bacterial infection, leukocyte transendothelial migration, apoptosis, and cell cycle in KEGG pathway. Importantly, Bcl7b, Bnip3, Bmx, Mcl1, and Pim1 were identified as critical regulators of neutrophil apoptosis, which may be potential drug targets for the treatment of neutropenia. We are currently testing the efficacy of the activators/inhibitors of the proteins encoded by these genes to investigate whether they would block DLBCL-induced neutrophil apoptosis.

Conclusion

In the present study, bioinformatic analyses of gene expression profiling data revealed the crucial genes involved in neutrophil apoptosis and gave insight into the underlying mechanism. Given our data, it may be likely that novel opportunities for the treatment of neutropenia, and eventually improvement of prognosis of DLBCL patients, might emerge.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13258-023-01404-7.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cell-cycle, DLBCL, Neutropenia, Proliferation, R-CHOP

Introduction

Diffuse Large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), accounting for 30% of new cases of NHL every year (Sant et al. 2010; Siegel et al. 2019). Although approximately 50–60% of patients are cured with immunochemotherapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) (Coiffier et al. 2002; Habermann et al. 2006), more than 30% of patients are refractory to these regimens or relapse after achieving remission, with a particularly poor prognosis (Friedberg 2011). Therefore, the development of effective therapies for DLBCL through understanding of disease pathogenesis and the cancer microenvironment regulated by lymphoma are required.

Neutrophils are polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes, accounting for 50–70% of the myeloid-derived white blood cells in human blood and more than 1000 cells are mass-produced per day. When infected with microorganisms such as bacteria or viruses, neutrophils are one of the first innate immune cells to respond. They constantly patrol the organism, and when they detect any signs of microbial infection, they quickly travel to the site of infection and to kill pathogens by phagocytosis (Borregaard 2010; Stark et al. 2005). Neutrophils also produce several cytokines and other inflammatory factors that regulate the immune system and enhance the response of other immune cells (Cassatella 1995).

Neutropenia refers to lower-than-normal levels of neutrophils in the blood, and since the function of neutrophils is to kill microorganisms, the occurrence of neutropenia is a leading cause of the risk of life-threatening infections. Chemotherapy is known to suppresses the hematopoietic system, impairing host immune mechanisms, leading to neutropenia as the most serious and common side effect (Crawford et al. 2004). Hence, not only the dose of chemotherapy is limited (Gandhi et al. 2005; Verstappen et al. 2003), but when neutropenia occurs during treatment increase the risk of recurrence and mortality from lymphoma by delay, re-duction, or early termination of chemotherapy. Additionally, a previous study demonstrated that the development of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia (CIN) is associated with overexpression of G-CSF receptor signaling pathway markers and suggest that increased CIN frequency during R-CHOP chemotherapy is associated with DLBCL altering the bone marrow environment and G-CSF receptor signaling pathway even in chemotherapy-naïve state (Kim et al. 2021). Although, considerable literature has demonstrated an association with chemotherapy on neutropenia and the importance of primary dose limiting toxicity for chemotherapy, neutropenia remains a prevalent problem. Most of the research has focused on chemotherapy as the main cause of neutropenia (Caggiano et al. 2005; Lyman et al. 2003, 2005, 2014), but the correlation between the pathogenesis of neutropenia and cancer cells is overlooked.

In this study, we sought to identify the genes and mechanism underlying neutrophil apoptosis induced by DLBCL cells. Major apoptosis- and growth arrest-related genes were revealed in mRNA sequencing analysis. Additionally, we investigated how these genes might interact to be associated with apoptosis in neutrophils, highlighting potential novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of neutropenia in patients with DLBCL.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Murine bone marrow cells from C57BL/6JJmsSlc mice, human DLBCL cell line Ly1 cells and mouse DLBCL cell line A20 cells were culture in RPMI-1640 medium (Hyclone, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Melbourne, VIC, Australia), 1% L-glutamine, 1% N-2hydrocyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Measurement of apoptosis by flow cytometry

The rate of neutrophil apoptosis was investigated in murine bone marrow cells treated with Ly1-derived conditioned medium (1 × 106 cells/ml), A20-derived conditioned medium (2 × 106 cells/ml) or mouse bone marrow cell-derived conditioned medium (2 × 106 cells/ml) in the presence or absence of doxorubicin. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, bone marrow cells were harvested and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rat anti-CD11b (cat No. #561,688, BD biosciences, San Jose, CA), allophycocyanin-conjugated rat anti-mouse Ly-6G (cat No. #560,599, BD biosciences), and propidium iodide (cat No. #51-66211E, BD biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The neutrophil apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry (BD Aria fusion) analysis.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

The transcription levels of Bnip3 and Bmx were measured by qRT-PCR. RNAs from FACS-sorted neutrophils after treatment with A20-derived CM in mouse bone marrow cells were extracted using TRIzol reagent (Favorgen, FATRR 001, Wien, Austria). PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Takara, RR047A, Kusatsu-shi, Japan) was used for cDNA synthesis. Real-time qRT-PCR was conducted using TOPreal qPCR PreMIX SYBR Green with low ROX (Enzynomics, RT500M). The sequences of the primers are listed below:

TBP Forward: 5′- GGAATTCCCATCTTTAGTCCAATGAT -3′

TBP Reverse: 5′- GTCAGAGTTTGAGAATGGAAGAGTT -3′

Bnip3 Forward: 5′- TCCAGCCTCCGTCTCTATTTATAATG -3′

Bnip3 Reverse: 5′- CAGCAGATGAGACAGTAACAGAGAT -3′

Bmx Forward: 5′- ATGGGAATGTACACTGTGTCCTTATT -3′

Bmx Reverse: 5′- GATGGGGTATTTCTTTGAGCATACTC -3′

RNA isolation, library construction and mRNA sequencing analysis

Murine bone marrow cells were co-cultured with 1 × 106 Ly1 cells or 2 × 106 murine bone marrow cells in 6-well chamber plate with 8-μm Polycarbonate membrane (PC) for 24 h, followed by sorting of neutrophils using a flow cytometer (BD Aria fusion). The total RNA of murine neutrophils was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA quality was measured with Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using the RNA 6000 Nano Chip (Agilent Technologies, Amstelveen, The Netherlands). Library was constructed by QuantSeq 3’mRNA-seq Library Prep Kit (Lexogen Inc., Vienna, Austria) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The finished library was purified from PCR components and then high-throughput sequencing was conducted by single-end 75 sequencing using NextSeq 500 (Illumina, Inc., USA). In this analysis, the murine bone marrow cells co-cultured with Ly1 cells were defined as the co-culture group; the murine bone marrow cells co-cultured with murine bone marrow cells were defined as the control group. Thus, a total of six libraries were divided into two co-cultured and control groups with three replicates. QuantSeq 3′mRNA sequencing reads were aligned using Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg 2012). Bowtie2 indices were either generated from the genome assembly sequence or the representative transcript sequences for aligning to the genome and transcriptome, respectively. The alignment files were used for collecting transcripts, estimating abundances, and detecting differential expression of genes. For the condition-specific analysis, read data mapped for each gene was normalized using the ‘reads per kilobase per million mapped reads’ (RPKM) method (Mortazavi et al. 2008). The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between two conditions were identified using the DEGseq package in the R statistical environment (Wang et al. 2010). In this analysis, MA-plot-based method with random sampling model is widely used to detect the intensity-dependent ratio of transcriptome data. The Z-score of two conditions was estimated and converted to a two-sided p value. For multiple testing correction, calculated p values were adjusted to false discovery rate (FDR) values using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). Genes with fold changes > 1.5, RPKM value > 4 and FDR < 0.05 were determined to be differentially expressed. Next, the DEG data was converted into a processed format for downstream analysis with functional enrichment using the Excel-based Differentially Expressed Gene analysis (EXDEGA) software v4. 0. 3 (EBIOGEN, Seoul, South Korea), an analysis tool that facilitates the analysis of numerous data from microarray according to the classified GO terms. The boxplot was created by ggplot2, an R script package, using the log2-transformed raw gene expression data as input. The DEGs related to apoptosis and proliferation were analyzed by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Mapper tools (https://www.genome.jp/av/mapper/, accessed on 8 September 2022). Gene classification and ontology were analyzed using Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/, accessed on 8 September 2022).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistically significant differences were calculated by a non-parametric Mann–Whiney U test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with Tukey’s post hoc test using the Microsoft Office Excel and GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Receiver operation characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed using the pROC R script package. The p value of ROC analysis is the differential expression level of a gene (p value = 1 − pt(abs(t), n − 1). All experiments were repeated at least three times independently.

Results

DLBCL cells and doxorubicin synergize to enhance apoptosis in neutrophils

Our previous study demonstrated that Ly1 human DLBCL cells induced apoptosis in neutrophils, which was confirmed using murine bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 J mice ex vivo. Also, combinatory treatment with Ly1 conditioned medium (CM) and doxorubicin, one of the components of R-CHOP regimen, elicited synergistic effect on apoptosis in neutrophils. We confirmed the reproducibility of the above results by analyzing neutrophil apoptosis in murine bone marrow cells using Ly1 CM (Fig. 1A, C). These data suggest that human DLBCL cells not only induce apoptosis in neutrophils, but also that DLBCL cooperates with doxorubicin to induce neutrophil apoptosis, potentially contributing to neutropenia in patients undergoing DLBCL treatment.

Fig. 1.

DLBCL cell line-derived conditioned medium induced neutrophil apoptosis in mouse bone marrow cells. Neutrophil apoptosis was measured by FACS analysis after treatment with DLBCL-derived CM or control (murine bone marrow cell-derived) CM for 24 h. Representative flow cytometry plots and percentages of propidium iodide (PI) positive cells in neutrophils (CD11b + Ly6G +) from C57BL/6 J mice bone marrow cells are shown. Apoptotic rates in neutrophils after treatment with Ly1 CM (A) or A20 CM (B) were quantified. C Neutrophil apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry following treatment with Ly1 CM and/or doxorubicin (0–5 μM) for 24 h. Representative flow cytometry plots and percentages of PI + cells in neutrophils (CD11b + Ly6G +) are shown. Apoptotic rates in neutrophils after treatment with Ly1 CM and/or doxorubicin were quantified. The two-tailed Mann–Whitney test was used to calculate statistical significance (*p < 0.05). D Neutrophils were sorted from normal bone marrow cells of C57BL/6 J mice (n = 3) using flow cytometry (collected CD11b and Ly6G double positive cells). Neutrophil apoptosis was measured using PI staining followed by FACS analysis in collected neutrophils treated with Ly1 or A20 CM for 24 h. Apoptotic rates in neutrophils after treatment with Ly1 CM or A20 CM were quantified. Statistical significance was calculated using the two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (*p < 0.05). E Relative expression levels of Bnip3 and Bmx were measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) after neutrophils were sorted using flow cytometry from C57BL/6 J mouse bone marrow cells following treatment with A20 CM for 24 h (n = 3, *p < 0.05)

To exclude possible artefacts caused by using cells of different species (human Ly1 cells and murine bone marrow cells), we repeated the experiments using A20 murine DLBCL cells. As shown in Fig. 1B, CM derived from A20 cells induced neutrophil apoptosis more than twofold compared to control in mouse bone marrow cells, demonstrating that cell death in neutrophils is efficiently induced by DLBCL cells originated from human and mouse. These data suggest that neutrophil apoptosis may be triggered by molecules highly conserved between human and mouse.

Given that bone marrow is composed of many different types of cells, such as normoblasts, myeloblasts, monocytes, myelocytes, lymphocytes, megakaryocytes, fibroblasts, macrophages, and adipocytes, the data in Fig. 1A–C raises a question as to whether neutrophil apoptosis is mediated by the direct interaction between neutrophils and DLBCL cells or it is caused by the indirect interaction involving another type of cells in the bone marrow. To directly test this, we FACS sorted neutrophils and exposed them to either Ly1 or A20 cells, followed by analysis of neutrophil apoptosis by PI-staining. The results demonstrate that treatment with CM derived from Ly1 or A20 cells increased apoptotic rate of neutrophils by more than fourfold compared with the control group (Fig. 1D). These data suggest that induction of neutrophil apoptosis by DLBCL cells does not require activity of other types of cells in the bone marrow and secretome derived from DLBCL cells is responsible for this process.

To understand the mechanism of neutrophil apoptosis by DLBCL-derived CM, we measured the expression levels of transcription factors related to pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins of Bcl-2 family members in neutrophils using qRT-PCR after exposure to A20-CM (Fig. 1E). Treatment with A20 CM significantly increased levels of pro-apoptotic Bnip3 while it significantly decreased anti-apoptotic Bmx levels. Bnip3 exerts its pro-apoptotic function by activating BAX or BAK, inducing disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential (Kubli et al. 2007). BMX encodes tyrosine kinase and functions as a negative regulator of BAK activation (Fox and Storey 2015). Taken together, DLBCL cells regulates transcription of pro- and anti-apoptotic genes, which may be associated with neutrophil apoptosis, and possibly, neutropenia.

To identify genes related to neutrophil apoptosis more comprehensively, we exposed murine bone marrow cells to Ly1 CM, confirmed neutrophil apoptosis, and sorted neutrophils using CD11b and Ly6G markers, followed by mRNA sequencing analysis.

mRNA sequencing analysis indicated that co-culture with DLBCL cells regulates gene expression associated with apoptosis and growth arrest in neutrophils

To determine gene expression profile associated with neutrophil apoptosis, we isolated mRNAs and conducted Quantseq 3′mRNA sequencing, which identified 165 upregulated and 741 downregulated genes. To examine whether control sample and co-cultured sample had differential gene expression pattern, we conducted principal component analysis (PCA). PCA results showed that first principal component (PC1) included 33% of variance, second principal component (PC2) included 22.9% of variance and third principal component (PC3) included 21.7% of variance (Figure S1A). PCA score plot showed that samples co-cultured with Ly1 and control sample were separated into two group, indicating that two groups had differential gene expression profiles (Figure S1B).

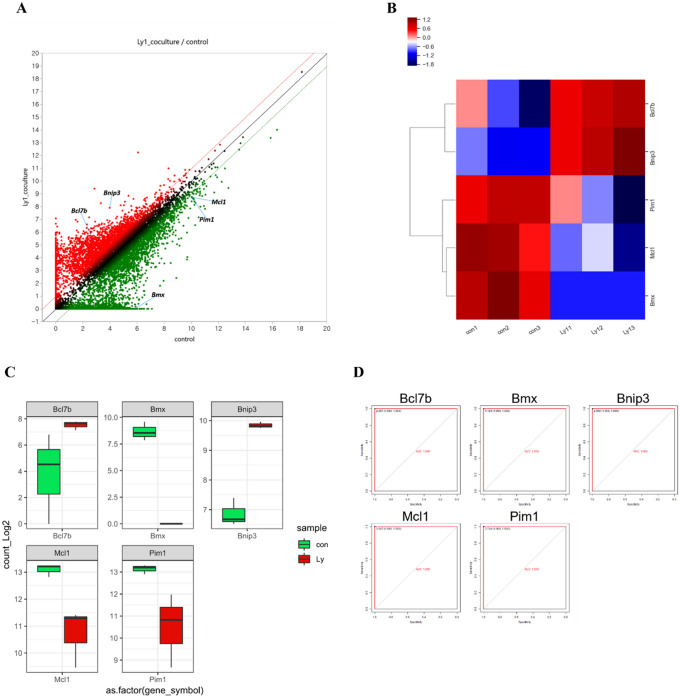

Co-culture with Ly1 cells modulates expression of apoptosis-related genes (Fig. 2A, B). Ly1 cells led to downregulation of anti-apoptotic gene such as Pim1, Mcl-1 and BMX (Fig. 2C). Mcl-1 encodes an anti-apoptotic protein of Bcl-2 family member. Mcl-1 inhibits apoptosis by binding pro-apoptotic protein and preventing release of cytochrome c in mitochondria (Fleischer et al. 2006). Conversely, Pro-apoptotic gene expression such as Bnip3 and Bcl7b increased when neutrophils were co-cultured with Ly1 cells (Fig. 2C). To assess the statistically significant gene expression, ROC analysis of cell apoptosis-associated genes was conducted. The closer the Area under the curve (AUC) is to 1.000, the better sensitivity and accuracy (Kumar and Indrayan 2011). The apoptosis-related genes have an AUC value of 1.000, indicating that there is statistical significance between the control group and the one co-cultured with Ly1 cells (Fig. 2D, Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Co-culture with Ly1 cells modulates expression of apoptosis-related genes. A Scatter plot of neutrophils co-cultured with Ly1 cells. (Fold change ≥ 2; RPKM value ≥ 4; FDR < 0.05). B Heatmap of apoptosis-related genes in neutrophils. C Boxplot of cell apoptosis-related genes in neutrophil cells. Green and red boxes indicate gene expression of control and neutrophils co-cultured with Ly1 cells, respectively. D The ROC curve of the 5 apoptosis-related genes (Bmx, Mcl1, Pim1, Bnip3, and Bcl7b), which show the statistically significant differences in the expression between the control group and the neutrophils co-cultured with Ly1 cells

Table 1.

ROC analysis in apoptosis-related genes

| Factor | Individual AUC | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bmx | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.05179201 |

| Mcl1 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.0105602 |

| Pim1 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.01572302 |

| Bnip3 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.001658633 |

| Bcl7b | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.03726025 |

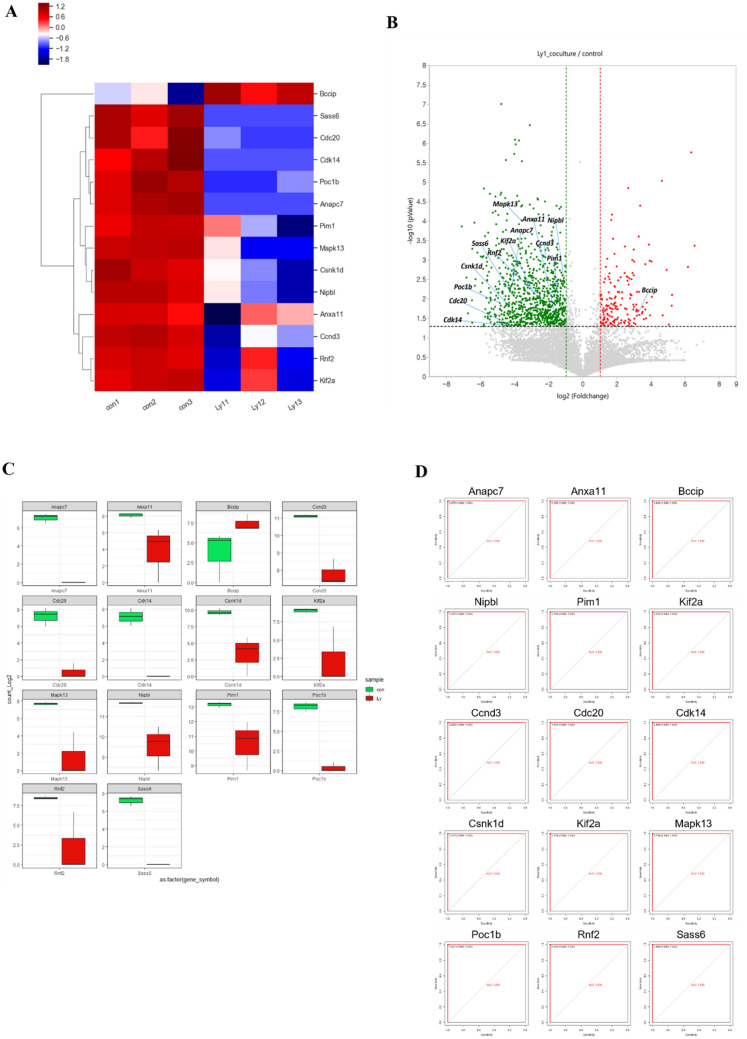

Also, co-culture with Ly1 cells decreased gene expression associated with cell cycle progression (Fig. 3A, B). Compared to the control, Kif2a, Rnf2, Ccnd3, Anxa11, NipbI, Csnk1d, Mapk13, Pim1, Anapc7, Poc1b, Cdk14, Cdc20 and Sass6 were downregulated and Bccip was upregulated in the Ly1 co-cultured group (Fig. 3C). CDC20 gene product is involved in anaphase-promoting complex (APC) activation. Activated APC by CDC20 induces ubiquitination of securin, ultimately destruction of securin and activation of seperase. Seperase triggers cohesion degradation of the sister chromatid, and leads to the separation of sister chromatid by mitotic spindle (Alberts et al. 2002). Cyclin D3 encoded by CCND3 forms complex with cyclin dependent kinase 4 and 6 (CDK4/6). Cyclin D3/CDK complex promotes G1 to S phage progression (Sawai et al. 2012). Conversely, transcriptional expression of BCCIP was significantly increased in co-cultured group with Ly1 cells (Fig. 3C). BCCIP is BRCA2 and p21 interacting protein and decreases p21 expression, thereby inhibiting G1 to S phase progression (Meng et al. 2004). To evaluate the validity of gene expression, we performed ROC curves of cell proliferation-related genes. The results demonstrated that the AUC value of a cell proliferation-associated gene of 1.000, indicating that the genes have significant ability for discriminate between control and Ly1 co-cultured group (Fig. 3D, Table 2). Collectively, our mRNA sequencing analyses showed that Ly1 CM upregulates expression of apoptosis- and growth arrest-related genes in neutrophils.

Fig. 3.

Co-culture with Ly1 cells modulates expression of proliferation-related genes. A Clustering heatmap of cell cycle-associated genes in neutrophils co-cultured with Ly1 cells compared to control. B Volcano plot of cell cycle progression-related gene in neutrophils. C Boxplot of cell proliferation-related genes in neutrophil cells. Green and red boxes indicate gene expression of control and neutrophils co-cultured with Ly1 cells, respectively. D The ROC curve of the 14 proliferation-associated genes (Kif2a, Rnf2, Ccnd3, Anxa11, NipbI, Csnk1d, Mapk13, Pim1, Anapc7, Poc1b, Cdk14, Cdc20, Sass6, and Bccip), which show the statistically significant difference in the expression between the control group and the neutrophils co-cultured with Ly1 cells

Table 2.

ROC analysis in cell proliferation-related genes

| Factor | Individual AUC | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pim1 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.01572302 |

| Kif2a | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.01395522 |

| Rnf2 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.008165494 |

| Ccnd3 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.001858891 |

| Anxa11 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.0110703 |

| Nipbl | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.008839778 |

| Csnk1d | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.02273147 |

| Mapk13 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.00287914 |

| Anapc7 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.01695522 |

| Poc1b | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.02501962 |

| Cdk14 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.06061531 |

| Cdc20 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.05760779 |

| Sass6 | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.02001423 |

| Bccip | 1.000 | 100 | 100 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.1036159 |

GO analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs

To investigate the functional enrichment of mRNA in control and Ly1 co-culture groups, we performed categorization and enrichment analysis using the GO enrichment analysis. A total of 1196 DEGs were classified into three categories: Biological process (BP), Cellular component (CC), and Molecular function (MF) through GO enrichment analysis (Figure S2). The GO analysis for DEG was most enriched in the CC category, was notably involved in cytoplasm, membrane, nucleus, and cytosol. In BP category, DEGs were mainly enriched in apoptosis process, immune system process, and protein phosphorylation. In the MF category, protein binding, transferase activity and ATP binding were enriched.

KEGG analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs

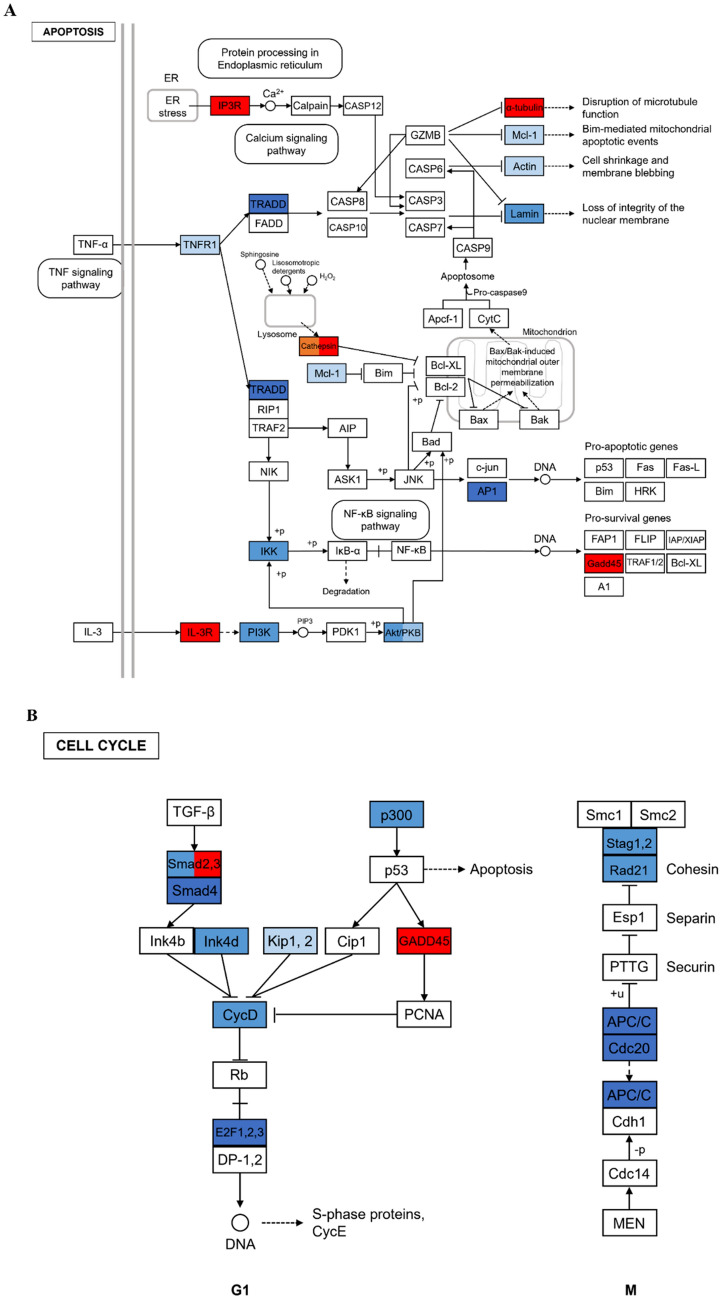

To improve our understanding of the downregulated DEGs in Ly1 co-culture group, DEGs were classified into pathway and enrichment analysis using the KEGG database. In the 1196 DEGs annotated with KEGG data, 198 were upregulated and 998 were downregulated. The KEGG pathway analyses revealed that upregulated 198 DEGs were related to 21 KEGG pathways (Table S1). The most enriched pathway was protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum, followed by ribosomes, Coronavirus disease and Parkinson disease. Also, pathways involved in cell survival and proliferation including ferroptosis, biosynthesis of amino acids, apoptosis and FoxO signaling pathways, and immune responses such as cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, antigen processing and presentation, and IL-17 signaling are upregulated. In addition, 998 downregulated DEGs were related to 71 KEGG pathways in Ly1 co-culture group. The highly enriched pathways were various bacterial infection, leukocyte transendothelial migration, and regulation of actin cytoskeleton. In addition, immune-associated pathways were regulated such as chemokine signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, and T cell receptor signaling pathway. The KEGG pathway analyses show that the DEGs involved in apoptosis and cell cycle were significantly downregulated in Ly1 co-culture group (Fig. 4A, B). Including Mcl-1, which encodes an anti-apoptotic protein, 11 genes related to TNF-R1, TRADD, Actin, Lamin, PI3K, Akt/PKB, IKK, and AP1 were downregulated in apoptosis. In the cell cycle, 13 genes related to Smad2, 3, Smad4, Ink4d, Kip1, 2, CycD, E2f1, 2, 3, p300, Stag1, 2, Rad21, APC/C, and Cdc20 were downregulated. These data suggest that co-culture with Ly1 inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in neutrophils.

Fig. 4.

Representative pathways resulted from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis. The adopted KEGG pathway map for A apoptosis and B cell cycle in neutrophil cells co-cultured with Ly1 cells. The red color represents upregulation and the blue means downregulation, which has color variation according to the expression intensity

Discussion

The evidence of crosstalk between cancer cells and neutrophils has been accumulated. For example, neutrophils play an important role in shaping the tumor microenvironement; the presence of tumor infiltrating neutrophils (TINs) has been associated with worse prognosis in several cancers. Additionally, cancer cells can regulate neutrophil abundance and function by secreting soluble mediators. Our data that DLBCL cells induce apoptosis in neutrophils may add another aspect of the interaction be-tween cancer cells and neutrophils.

One of the most common adverse effects that cancer patients experience during chemotherapeutic treatment is chemotherapy-induced neutropenia (CIN), which may put patients at risk of developing febrile neutropenia (FN) and decreasing survival rates (Kuderer et al. 2006). Introduction of granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSFs) reduced the incidence of CIN, leading to improvement of patient outcomes (Kuderer et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2015). It is interesting to note that frequencies of FN vary among patients with different types of cancers, such as breast cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), who did not receive G-CSFs (Averin et al. 2021). Our previous and current data demonstrating that DLBCL cells can kill neutrophils ex vivo imply that cancer cells may contribute, at least partly, to neutropenia.

On the Basis of the mRNA sequencing result, our study revealed that expression of apoptosis and proliferation-related genes (Pim1, Mcl-1, BMX, Bnip3, Bcl7b, CDC20, and CCND3) were modified by DLBCL cells in neutrophils. Our previous results suggested that DLBCL cells may contribute to neutropenia by inducing apoptosis, and this current study identified the genes involved in this process, which gives insight into the underlying mechanism and the potential drug targets that may promote survival of neutrophils.

Doxorubicin, one of the components of R-CHOP, acts on cancer cells by intercalation into DNA and disruption of DNA repair and generating free radicals that damage cell membranes, DNA and proteins (Thorn et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2014). Typical side effects of doxorubicin include fever or chills and neutropenia (Carvalho et al. 2009). We demonstrated that DLBCL cells and doxorubicin cooperate to enhance apoptosis in neutrophils. It has been shown that HIV-NHL patients treated with EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin) regimen and elderly DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP demonstrated a significant impact of Myc rearrangement; both groups of patients have inferior prognosis, lower event-free survival (EFS), and severe neutropenia (Kühnl et al. 2017; Ramos et al. 2020). Intriguingly, Ly1 that we used to obtain conditioned media is considered double-hit lymphomas (DHLs) with rearrangement of both Myc and Bcl-2 (Li et al. 2019). Given that intrinsic mechanisms of cancer cells, including (epi)genetics, shape the secretome and neutrophil functions (Duits and de Visser 2021), we speculate that abnormal expression of Myc in Ly1 DLBCL cells may be associated with negative impact of Ly1 secretome on neutrophil viability, which can be further enhanced by chemotherapy.

We believe that this study highlights two important implications in regards to neutropenia. (i) Hitherto, the impact of cancer cells on neutrophils has not been well-characterized and the focus has been on chemotherapeutic agents. Our data clearly suggest that cancer cells can kill neutrophils and patients with cancer may be more vulnerable to infections than healthy counterparts, even before initiation of chemotherapy. Additionally, given our results demonstrating the synergistic effect of cancer cells and chemotherapeutic drugs on neutrophil apoptosis, chemotherapy regimen and schedules may need to be established accordingly so that residual cancer cells are completely eradicated. (ii) This study gives insight into the mechanism and potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of neutropenia. Our data demonstrate that secretome derived from DLBCL cells elicits neutrophil apoptosis without activity of other types of cells. Future experiments will focus on identification of the responsible molecules (ligands) in the secretome and their cognate receptors on neutrophils, followed by development of therapeutic intervention strategies. For example, antibodies could be generated to inactivate the ligands and/or their receptors, and small peptides could be used to interrupt the interaction between the ligands and their receptors. Additionally, given that pro-apoptotic Bcl7b and Bnip3 appear to be involved in apoptosis of neutrophils, it would be considerable to co-administer inhibitors of these molecules along with chemotherapeutic agents.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: B-EJ, J-EL, S-WK, and H-JS; methodology: B-EJ, J-EL, HJJ, EGP, and DHL; software: B-EJ, J-EL, HJJ, EGP, and DHL; validation: B-EJ, J-EL; formal analysis: HJJ, EGP, and DHL; investigation: B-EJ, J-EL, HJJ, EGP, and DHL; data curation: B-EJ, J-EL, HJJ, EGP, and DHL; writing—original draft preparation: B-EJ, J-EL, HJJ, EGP, DHL, Y-SS, H-SK, S-WK, and H-JS; writing—review and editing: B-EJ, Y-SS, H-SK, S-WK, and H-JS; visualization: B-EJ, J-EL, HJJ, EGP, and DHL; supervision: Y-SS, H-SK, S-WK, and H-JS; project administration: S-WK, H-JS; funding acquisition: S-WK, H-JS; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Biomedical Research Institute Grant (20200018), Pusan National University Hospital to H.-J.S.

Ddata availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Institutional review board statement

The animal protocol used in this study was reviewed and approved by the Pusan National University-Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (PNU-2021-3056).

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Byeol-Eun Jeon, Ji-Eun Lee, and Jungwook Park have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ho-Jin Shin, Email: hojinja@hanmail.net.

Sang-Woo Kim, Email: kimsw@pusan.ac.kr.

References

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002) Intracellular control of cell-cycle events. In: Molecular biology of the cell, 4th edn. Garland Science

- Averin A, Silvia A, Lamerato L, Richert-Boe K, Kaur M, Sundaresan D, Shah N, Hatfield M, Lawrence T, Lyman GH, Weycker D. Risk of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in patients with metastatic cancer not receiving granulocyte colony-stimulating factor prophylaxis in US clinical practice. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:2179–2186. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05715-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Borregaard N. Neutrophils, from marrow to microbes. Immunity. 2010;33:657–670. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano V, Weiss RV, Rickert TS, Linde-Zwirble WT. Incidence, cost, and mortality of neutropenia hospitalization associated with chemotherapy. Cancer. 2005;103:1916–1924. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho C, Santos RX, Cardoso S, Correia S, Oliveira PJ, Santos MS, Moreira PI. Doxorubicin: the good, the bad and the ugly effect. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:3267–3285. doi: 10.2174/092986709788803312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassatella MA. The production of cytokines by polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Immunol Today. 1995;16:21–26. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Brière J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, Morel P, Van Den Neste E, Salles G, Gaulard P, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J, Dale DC, Lyman GH. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: risks, consequences, and new directions for its management. Cancer. 2004;100:228–237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duits DEM, de Visser KE. Impact of cancer cell-intrinsic features on neutrophil behavior. Semin Immunol. 2021;57:101546. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2021.101546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer B, Schulze-Bergkamen H, Schuchmann M, Weber A, Biesterfeld S, Müller M, Krammer PH, Galle PR. Mcl-1 is an anti-apoptotic factor for human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JL, Storey A. BMX negatively regulates BAK function, thereby increasing apoptotic resistance to chemotherapeutic drugsBMX mediates chemoresistance through BAK inhibition. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1345–1355. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg JW. Relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:498–505. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi TK, Bartel SB, Shulman LN, Verrier D, Burdick E, Cleary A, Rothschild JM, Leape LL, Bates DW. Medication safety in the ambulatory chemotherapy setting. Cancer. 2005;104:2477–2483. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, Gascoyne RD, Cassileth PA, Cohn JB, Dakhil SR, Woda B, Fisher RI, Peterson BA, Horning SJ. Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3121–3127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DY, Nam J, Chung J-S, Jeon BE, Lee JH, Jo J-C, Kim S-W, Shin H-J. Predictive parameters of febrile neutropenia and clinical significance of G-CSF receptor signaling pathway in the development of neutropenia during R-CHOP chemotherapy with prophylactic pegfilgrastim in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Res Treat. 2021 doi: 10.4143/crt.2021.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubli DA, Ycaza JE, Gustafsson ÅB. Bnip3 mediates mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death through Bax and Bak. Biochem J. 2007;405:407–415. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J, Cosler LE, Lyman GH. Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia in adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106:2258–2266. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J, Lyman GH. Impact of primary prophylaxis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on febrile neutropenia and mortality in adult cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2007 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühnl A, Cunningham D, Counsell N, Hawkes EA, Qian W, Smith P, Chadwick N, Lawrie A, Mouncey P, Jack A, et al. Outcome of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP: results from the UK NCRI R-CHOP14v21 trial with combined analysis of molecular characteristics with the DSHNHL RICOVER-60 trial. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1540–1546. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Indrayan A. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for medical researchers. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s13312-011-0055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Gupta SK, Han W, Kundson RA, Nelson S, Knutson D, Greipp PT, Elsawa SF, Sotomayor EM, Gupta M. Targeting MYC activity in double-hit lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements with epigenetic bromodomain inhibitors. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0761-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman GH, Morrison VA, Dale DC, Crawford J, Delgado DJ, Fridman M, OPPS Working Group. ANC Study Group Risk of febrile neutropenia among patients with intermediate-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma receiving CHOP chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:2069–2076. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000119262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman GH, Lyman CH, Agboola O. Risk models for predicting chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Oncologist. 2005;10:427–437. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-6-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman GH, Abella E, Pettengell R. Risk factors for febrile neutropenia among patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2014;90:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Lu H, Shen Z. BCCIP functions through p53 to regulate the expression of p21Waf1/Cip1. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:1457–1462. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.11.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos JC, Sparano JA, Chadburn A, Reid EG, Ambinder RF, Siegel ER, Moore PC, Rubinstein PG, Durand CM, Cesarman E, et al. Impact of Myc in HIV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with EPOCH and outcomes with vorinostat (AMC-075 trial) Blood. 2020;136:1284–1297. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant M, Allemani C, Tereanu C, De Angelis R, Capocaccia R, Visser O, Marcos-Gragera R, Maynadié M, Simonetti A, Lutz J-M, Berrino F, the HAEMACARE Working Group Incidence of hematologic malignancies in Europe by morphologic subtype: results of the HAEMACARE project. Blood. 2010;116:3724–3734. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai CM, Freund J, Oh P, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Bretz JC, Strikoudis A, Genesca L, Trimarchi T, Kelliher MA, Clark M, et al. Therapeutic targeting of the cyclin D3: CDK4/6 complex in T cell leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark MA, Huo Y, Burcin TL, Morris MA, Olson TS, Ley K. Phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils regulates granulopoiesis via IL-23 and IL-17. Immunity. 2005;22:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn CF, Oshiro C, Marsh S, Hernandez-Boussard T, McLeod H, Klein TE, Altman RB. Doxorubicin pathways: pharmacodynamics and adverse effects. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2011;21:440. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32833ffb56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstappen CC, Heimans JJ, Hoekman K, Postma TJ. Neurotoxic complications of chemotherapy in patients with cancer: clinical signs and optimal management. Drugs. 2003;63:1549–1563. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Feng Z, Wang X, Wang X, Zhang X. DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:136–138. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Baser O, Kutikova L, Page JH, Barron R. The impact of primary prophylaxis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factors on febrile neutropenia during chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:3131–3140. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2686-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Teves SS, Kemp CJ, Henikoff S. Doxorubicin, DNA torsion, and chromatin dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1845:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.