Abstract

Aims:

Detrimental effects on health and well-being were reported during the COVID-19-induced lockdown periods in several countries, but these associations have not been studied in small-scale island societies. This study aimed to examine the lockdown period’s impact on general well-being, perceived stress and activity levels in the Faroe Islands.

Methods:

We used cross-sectional data from two extensive population-based surveys of the general health conducted in November 2019 (the pre-COVID survey; n=2906), and four to six weeks into the first national lockdown (the lockdown survey; n=1204).

Results:

A larger proportion of participants in the lockdown survey versus pre-COVID survey displayed excellent/very good self-rated health (68.1% vs. 62.0%; p<0.001), and the same pattern was observed for reporting good quality of life (85.7% vs. 82.7%; p<0.05). These associations remained statistically significant in a logistic regression model after adjusting for characteristics for which varying impact of the pandemic has been shown. Indicators of health behaviour showed that larger proportions of participants kept active during the lockdown survey versus pre-COVID survey, and these differences were statistically significant for physical, mental and spiritual activities (p<0.001). On the other hand, similar stress levels in the pre-COVID/lockdown periods were observed, but stratified analysis showed that participants with a high-stress level displayed better self-rated health in the lockdown period compared to the pre-COVID period (p=0.001).

Conclusions:

Findings indicate that self-reported health and quality of life improved during the early phase of the COVID lockdown, and individuals reported higher activity levels associated with good mental health during the COVID-19-induced lockdown period.

Keywords: Self-reported health, Act-Belong-Commit, mental health, quality of life, perceived stress and well-being

Introduction

Following the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, the contagion spread worldwide and was defined as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020 [1]. In response, authorities worldwide set out far-reaching measures to manage the pandemic, affecting the daily lives of whole populations in an unprecedented manner, with societal lockdown forcing social distancing and self-isolation of individuals. While considered necessary to handle what has been described as the most significant global crisis since World War II, such measures could themselves challenge the general well-being of populations [2].

The Faroe Islands, an archipelago in the North Atlantic with 53,500 inhabitants, saw their first case of COVID-19 on 3 March 2020 and have experienced periods with high levels of transmission interspersed between long periods of COVID-19 elimination. The Faroese authorities have been relatively successful in managing the contagion during periods of the pandemic. An active suppression strategy was employed early on, with a high degree of testing and rigorous tracking of cases and isolating of close contacts in compliance with guidelines laid down by the WHO [3,4]. However, during the first COVID-19 wave between March and April/May 2020, the Faroe Islands were in lockdown, and the vulnerability inherent in a small geographically isolated population may have affected health status, well-being and behaviour in a particular manner.

In other regions of the world, there were reports of detrimental effects of COVID-19-induced restrictions and regulations, covering general well-being, mental health and physical activity [2,5–10]. Time-series survey data from more than 200,000 Danish, Dutch, French and British individuals showed high levels of worry, anxiety and loneliness in the early phases of the lockdown, which gradually decreased with the reopening of society [9].

The Faroese Board of Public Health conducts extensive broad-scale surveys of the general health and well-being of the adult population every four years [11], with a new population-based survey undertaken in November 2019, a few months before the first lockdown period in the Faroe Islands (the pre-COVID survey). Because of the pandemic, the survey was repeated approximately four to six weeks into the first national lockdown, which lasted approximately six weeks (the lockdown survey). The pre-COVID survey can thus be applied as a baseline indicator of the general health status in the Faroe Islands, and the lockdown survey provides a comparative measure to evaluate the acute effect of the lockdown period. Due to the significant cultural, demographical and geographical differences between large continental countries and small-scale societies, the response to the lockdown in this population may differ from reports from larger societies.

In both the pre-COVID survey and the lockdown survey, questions on activity level in relation to the ‘ABCs of mental health’ (Act-Belong-Commit) concept were included [12]. The ABC concept, originally developed in Australia and described by Donovan et al., was conceived as a community-based mental health promotion campaign [12]. The concept is based on three simple messages or verbs to act on: act, belong, commit, that is, keeping active and engaged in the broadest sense, developing a strong sense of belonging and participating in community activities, and doing things that provide meaning and purpose in life [13]. There is substantial evidence that these three behavioural domains are associated with improved general health status [13–16]. The Faroese Board of Public Health has been working with the ABC concept since 2016, with various initiatives aimed at promoting mental health.

The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that the first COVID-19-induced lockdown impacted general well-being, perceived stress and ABC activities in the adult population in the Faroe Islands.

Methods

Study population

The study utilises data from two national population-based surveys conducted in 2019 and 2020. Both cross-sectional samples were based on random samples from the Faroese Population Registry.

In the 2019 Public Health Survey Faroes (the pre-COVID survey), a total of 5990 men and women aged 18–85 years (15.8% of the adult population) were invited to participate. The participants received a letter with instructions and a web address to an electronic questionnaire. Individuals aged ⩾60 years were given the option of answering the questionnaire on paper and returning it by regular mail. Invitation letters were sent in mid-November and early December 2019. When the data collection was completed in mid-January 2020, a total of 2906 (48.5%) questionnaires had been returned. Measures to increase the participation rate included announcements in the public media and a reminder phone call in mid-December.

Invitations for the 2020 Public Health Survey Faroes (the lockdown survey) were sent in late April 2020 during the first lockdown period and prior to the lifting of societal measures following the first COVID-19 wave. A total of 2108 men and women aged 18–75 years (5.9% of the adult population) were invited to participate with the exact same procedure as described for the pre-Covid questionnaire. When the data collection was completed by early May 2020, a total of 1204 (51.1%) questionnaires had been returned.

Questionnaires

The questionnaire for the pre-COVID survey was based on the 2015 Public Health Survey Faroes [11] with some alterations and additional questions, particularly concerning demographic and lifestyle information. The 2019 questionnaire had 93 questions on health, well-being and behaviour. The lockdown survey is an abridged version of the pre-COVID survey with a total of 67 questions: 52 were copied from the 2019 questionnaire, and 15 related to the pandemic situation were added.

Exposure

The exposure of interest is the COVID-19 lockdown, and comparisons of indicators of well-being, behavioural and lifestyle factors are made across the pre-COVID survey and the lockdown survey.

Measures of general well-being and perceived stress

In the study, we used self-rated health and quality of life as measurements of general well-being. Self-rated health was assessed by the question ‘How would you describe your general health?’, with the following response categories: ‘excellent’, ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘not so good’ and ‘poor’. For the analyses, the upper two response categories, ‘excellent’ and ‘very good’ health, were collapsed; ‘good health’ was kept as a separate category; and the categories ‘not so good’ and ‘poor’ were recoded into ‘poor health’. For the logistic regression models, ‘excellent’, ‘very good’ and ‘good’ were recoded into ‘good health’ in order to construct a dichotomous outcome from this variable. Quality of life was assessed by the question ‘How would you describe your quality of life?’, with the following response categories: ‘very poor’, ‘poor’, ‘neither good nor bad’, ‘good’ and ‘very good’. For all analyses, the categories ‘very poor’, ‘poor’ and ‘neither good nor bad’ were recoded into ‘fair/poor quality of life’, and the categories ‘good’ and ‘very good’ were recoded into ‘good quality of life’.

We used the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) by Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein [17] to assess stress level. The questions on the scale are related to the participants’ feelings and thoughts and the extent to which each respondent has experienced his/her life as unpredictable or stressful during the preceding four weeks. Each item was rated on a five-point scale, where 0=‘never’, 1=‘almost never’, 2=‘sometimes’, 3=‘fairly often’ and 4=‘very often’. All items were summed to obtain scale scores, where the higher the score, the higher the degree of perceived stress. Scores in the upper quintile were defined as having a high stress level, and scores in the lower four quintiles were thus defined as having a low stress level [18].

ABC activity

As indicators of health behaviour in our study, we used the ‘Act’ domain of the ABC concept, which was assessed in both surveys. Our focus is ABC activity, and the ‘Act’ domain comprises a broad definition of activity and entails keeping physically, mentally, socially and spiritually active. It is assessed by the questions ‘How many times a week: 1. Are you physically active?; 2. Do you do something requiring thinking and concentration?; 3. Do you have social contact with others?; 4. Do you engage in religious or spiritual activity?’, with the following response categories: ‘less than once a week’, ‘1–3 times per week’ and ‘4 or more times per week’.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (number and percentage) are used to describe the sample, stratified by survey, and statistical analyses of group comparisons based on nominal variables were done using chi-square tests.

In additional analyses, we furthermore evaluated the association between each survey and our selected well-being indicators – self-rated health, quality of life and PSS – in logistic regression models. This analytical strategy was chosen, since evidence has indicated differential impact of the pandemic and subsequent lockdown in different demographic groups with respect to health and well-being [2,6,7,9]. We present odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for a crude model with survey and self-rated health, quality of life and PSS (model 1). In a second model, we adjust for primary potential confounders: sex and age. In a third model, we further adjust for cohabitation status, educational level and work status (model 3). Age was kept as a continuous variable. Educational level was categorised as: ‘at university or in other training’, ‘no formal education or short training courses’, ‘trained/skilled’, ‘short higher education, two to three years’, ‘medium higher education, three to four years’, ‘long higher education, more than four years’ and ‘other education’.

Work status was categorised into: ‘salary earner’, ‘unemployed’, ‘early retiree’, ‘pensioner’ and ‘others’. Cohabitation status was categorised into: ‘single’, ‘married or in a registered partnership’, ‘cohabiting but not married’, ‘divorced’ and ‘widowed’.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows v27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Background characteristics

A total of 2906 (48.5%) participants in the pre-COVID and 1204 (57.1%) participants in the lockdown survey completed the questionnaire. The distribution of men and women was 47% and 53% in both surveys, with a mean age of 46 and 47 years in the pre-COVID survery and the lockdown survey, respectively. In both surveys, the majority had either no formal education, were skilled workers or had medium higher education with three to four years at university, were regular salary earners and living with a partner. Overall, the pre-COVID survey and the lockdown survey samples were similar regarding sex distribution, work and cohabitation status, whereas small differences were observed with respect to mean age and educational level (Table I).

Table I.

Descriptive characteristics of the two individual samples (pre-COVID (n=2906) and lockdown (n=1204)) and general well-being and perceived stress.

| Survey | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-COVID | Lockdown | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | Men | 1367 | 47.1 | 569 | 47.3 |

| Women | 1535 | 52.9 | 635 | 52.7 | |

| Age* (mean±SD) | 47.0±17.2 | 46.1±15.9 | |||

| Education** | Studying at university or in training | 159 | 6.0 | 76 | 6.9 |

| No formal education, or only short courses | 634 | 24.0 | 227 | 20.5 | |

| Trained or skilled | 603 | 22.8 | 262 | 23.6 | |

| Short higher education, 2–3 years | 123 | 4.6 | 63 | 5.7 | |

| Medium higher education, 3–4 years | 590 | 22.3 | 265 | 23.9 | |

| Long higher education, >4 years | 211 | 8.0 | 105 | 9.5 | |

| Other education | 326 | 12.3 | 110 | 9.9 | |

| Work status | Salary earner | 1814 | 67.6 | 762 | 67.4 |

| Unemployed | 112 | 4.2 | 65 | 5.7 | |

| Early retiree | 80 | 3.0 | 38 | 3.4 | |

| Pensioner | 369 | 13.8 | 133 | 11.8 | |

| Others | 307 | 11.4 | 133 | 11.8 | |

| Cohabitation | Single | 440 | 16.3 | 209 | 18.5 |

| Married or in a registered partnership | 1582 | 58.7 | 639 | 56.4 | |

| Cohabiting | 508 | 18.9 | 225 | 19.9 | |

| Divorced | 66 | 2.4 | 31 | 2.7 | |

| Widowed | 98 | 3.6 | 28 | 2.5 | |

| Self-rated health* | Excellent/very good | 1795 | 62.0 | 816 | 68.1 |

| Good | 885 | 30.6 | 337 | 28.1 | |

| Not so good/poor | 214 | 7.4 | 45 | 3.8 | |

| Quality of life** | Good | 2355 | 82.7 | 1021 | 85.7 |

| Fair/poor | 494 | 17.3 | 170 | 14.3 | |

| Perceived Stress Scale | Low level of stress | 2156 | 79.6 | 887 | 78.1 |

| High level of stress | 552 | 20.4 | 248 | 21.9 | |

Significant at p<0.001 (chi-square test).

Significant at p<0.05 (chi-square test).

General well-being

There was an apparent increase in self-rated health, with the proportion of participants who defined their health as excellent or very good being 62% in the pre-COVID survey and 68% in the lockdown survey. A similar difference was observed regarding participants reporting their quality of life as good, which increased from 83% to 86% between the surveys (Table I).

This difference in self-rated health between surveys remained statistically significant in logistic regression models after adjusting for sex and age: the OR for poor versus good self-rated health for the lockdown survey compared to the pre-COVID survey was 0.51 (95% CI 0.36–0.71). After further adjustment for cohabitation, educational level and work status, the OR for poor versus good self-rated health during lockdown compared with the pre-COVID survey was 0.50 (95% CI 0.35–0.72; Table II).

Table II.

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for reporting fair/poor as opposed to good self-rated health and quality of life and high as opposed to low-stress level, in the pre-COVID survery (n=2906) and the lockdown survey (n=1204).

| Crude | Adjusted* | Adjusted** | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value*** | OR | 95% CI | p-value*** | OR | 95% CI | p-value*** | ||

| Self-rated health | ||||||||||

| Survey | Pre-COVID | Ref. | – | <0.001 | Ref. | – | <0.001 | Ref. | – | <0.001 |

| Lockdown | 0.49 | 0.35–0.68 | 0.51 | 0.36–0.71 | 0.50 | 0.35–0.72 | ||||

| Quality of life | ||||||||||

| Survey | Pre-COVID | Ref. | – | 0.02 | Ref. | – | 0.01 | Ref. | – | 0.005 |

| Lockdown | 0.79 | 0.66–0.96 | 0.78 | 0.65–0.94 | 0.74 | 0.60–0.91 | ||||

| Perceived Stress Scale | ||||||||||

| Survey | Pre-COVID | Ref. | – | 0.307 | Ref. | – | 0.400 | Ref. | – | 0.520 |

| Lockdown | 1.09 | 0.92–1.29 | 1.08 | 0.91–1.28 | 1.06 | 0.88–1.28 | ||||

Adjusted for confounders of sex and age.

Adjusted for confounders as in model 2 and further adjusted for cohabitation, educational level and work status.

p-value from Wald test for overall association.

The association was also statistically significant for quality of life, with participants in the lockdown survey having lower odds of fair/poor quality of life (OR=0.78; 95% CI 0.65–0.94) compared to pre-COVID survey participants, after adjustment for sex and age. This association remained similar after further adjustment for cohabitation, educational level and work status: the OR for fair/poor quality of life for lockdown survery versus pre-COVID survey participants was 0.74 (95% CI 0.60–0.91; Table II).

PSS

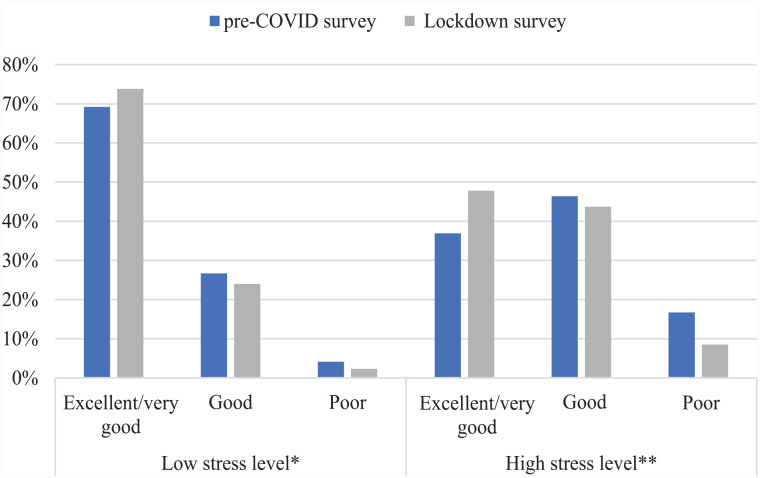

No statistically significant association was found for perceived stress level in the lockdown survey compared with the pre-COVID survey. However, when we examined the association between self-rated health in the pre-COVID survey and the lockdown survey stratified by stress level, there appeared to be a greater increase in self-rated health for participants with a high stress level than among participants with a low stress level (Figure 1). We see an increase of 11 percentage points in the reporting of good self-rated health from the pre-COVID survey to the lockdown survey for participants with high stress levels and a decrease of eight percentage points in the reporting of less poor self-rated health. The corresponding figures for participants with a low stress level were differences of five and two percentage points.

Figure 1.

Self-rated health in the pre-COVID survey and the lockdown survey stratified by stress level.

* Significant association between self-rated health and survey on a p<0.05 level with a chi-squared test.

** Significant association between self-rated health and survey on a p<0.001 level with a chi-squared test.

ABC activity

Activities related to the ‘Act’ domain of the ABC concept appeared to change from pre-COVID to lockdown, with statistically significant differences across surveys (Table III). A higher number of participants in the lockdown survey reported engaging in ABC-related activities compared to the pre-COVID survey, especially physical, mental and spiritual activities (p<0.001).

Table III.

Activities in the ‘Act’ domain during a normal week as reported in the pre-COVID survey and the lockdown survey.

| Pre-COVID survey | Lockdown survey | p-value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=2906 | N=1204 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Physically active | Less than once a week | 670 | 25.1 | 183 | 16.2 | <0.001 |

| 1–3 times per week | 1181 | 44.2 | 471 | 41.7 | ||

| ⩾4 times per week | 820 | 30.7 | 476 | 42.1 | ||

| Mentally active | Less than once a week | 689 | 26.1 | 216 | 19.3 | <0.001 |

| 1–3 times per week | 875 | 33.2 | 378 | 33.8 | ||

| ⩾4 times per week | 1072 | 40.7 | 525 | 46.9 | ||

| Socially active | Less than once a week | 144 | 5.4 | 51 | 4.5 | 0.1 |

| 1–3 times per week | 630 | 23.6 | 239 | 21.2 | ||

| ⩾4 times per week | 1893 | 71.0 | 840 | 74.3 | ||

| Spiritually active | Less than once a week | 1271 | 47.9 | 481 | 42.9 | <0.001 |

| 1–3 times per week | 908 | 34.2 | 376 | 33.5 | ||

| ⩾4 times per week | 474 | 17.9 | 265 | 23.6 | ||

p-values from chi-square test.

Discussion

Our results are the first to evaluate the differences in reporting of general well-being, perceived stress and activity levels from pre-COVID to the four to six weeks of COVID-19-induced lockdown in a small island population. Our study also provides a unique opportunity to investigate measurements of activities related to the ABC concept and potential changes from pre-COVID to lockdown in the Faroe Islands.

Our principal findings were that participants in the lockdown survey reported better self-rated health and quality of life compared with responses in the pre-COVID survey, and that higher levels of physical, mental and spiritual activity were reported during lockdown compared with responses to the pre-COVID survey. If we interpret the differences in reporting between surveys as actual changes in the general population during the period, it appears that the general well-being of the adult population in the Faroe Islands improved during lockdown, and we may speculate that this resulted from increasing activity levels related to the ABC concept [13].

Our results are in apparent contrast to findings from other studies, where several health indicators have been shown to be affected by COVID-19-induced restrictions and regulations, including general well-being, mental health and physical activity [5–9]. Indeed, in our data, the proportion of people who rated their health status as being excellent or very good changed from 62% to 68% from the pre-COVID survey to the lockdown survey. Quality of life also appeared to be significantly uprated after four to six weeks of lockdown, with 86% of respondents reporting their quality of life as good in the lockdown survey compared to 83% at baseline. The associations for self-rated health and quality of life with each survey were statistically significant, even after adjustment for potential confounders, with ORs of 0.50 and 0.74. The lockdown period of four to six weeks thus seemed to improve people’s perception of general well-being in a small-scale island society. The systematic review by Bonati et al. investigated the psychological impact of the COVID-19-induced quarantine on the general European adult population [7]. The authors reported that the COVID-19 pandemic posed an unprecedented threat to mental health and that anxiety, depression, distress and post-traumatic symptoms were frequently experienced during the COVID-19 lockdown [7]. Moreover, Niedzwiedz et al. demonstrated in the UK that psychological distress increased one month into lockdown [2], which also contrasts with our results. Our findings of improved well-being in the Faroe Islands therefore appear to diverge from findings from large continental countries [6,19], which may be associated with factors such as culture, trust in governmental and health authorities, COVID-19 strategy and geographical conditions, as well as the less severe outcomes of the pandemic in the Faroe Islands. The first fatality was seen late in 2020, and few patients with COVID-19 were hospitalised [3,4].

In line with the finding of improved well-being during lockdown, activity levels were also reported to be higher in response to our questions on the ‘Act’ domain of the ABC concept compared to the pre-COVID survey. The higher levels of activity may be a central or even explanatory factor in the higher self-reported well-being. Indeed, in a study by Stock et al., with data from 35,301 participants, the authors found a positive association between spending time outdoors and improved well-being during lockdown [20]. Other studies indicate that the specific impact of the pandemic also seems to be affected by contextual factors such as region and lockdown period [21]. For example, Cheval et al. found that in participants living in France or Switzerland, lockdown led to more time being spent walking and engaging in other moderate-level physical activity compared to the pre-COVID period [21]. In contrast, Savage et al. reported significant decreases in mental well-being and activity levels in the UK during the initial five weeks of lockdown, while perceived stress and time spent in sedentary activities increased [22]. Thus, in regions such as the Faroe Islands, where the population had easy access to nature and large open spaces and permission to go outside freely, lockdown may have been beneficial for general well-being. Since the Faroe Islanders rated physical, mental and spiritual activity levels higher during the lockdown, the period may have been perceived as a ‘time-out’ from daily routines.

A common issue raised during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the impact of the lockdown initiatives on frail, low-resilience and other high-risk groups [6,7,23,24]. In our comparison of the pre-COVID survey and the lockdown survey, no statistical between-survey differences were observed in the general stress level. Our results indicate that both low and high stress-level populations improved their self-rated health status during lockdown survey, with even more pronounced differences for individuals who reported high stress levels. This finding may support the ‘time-out’ hypothesis raised above and indicates that any positive impact from ‘slowing down our way of living’ might have brought the largest benefit to those reporting a high stress level. This finding also diverges from observations elsewhere [23], possibly indicating special responses in the Faroe Islands compared to larger communities and possibly rooted in close family ties and specific social structures [25]. One possible reason why individuals who reported high stress levels did not see a decrease in general well-being may relate to how the Faroe Islands handled the COVID-19 situation. Actions such as large-scale testing, contact tracing and isolation combined with social distancing led to the initial successful elimination of COVID by late April, despite a relatively high starting point [3]. Furthermore, the most vulnerable groups are less likely to participate in a survey such as ours. So, our method may not be the best for investigating lockdown effects on vulnerable groups.

Comparing data from two extensive surveys of the general health and well-being of the adult population conducted a few months before and during the first lockdown interval provided us with a unique opportunity to investigate the impact of the COVID-induced lockdown, which is a strength of our study. However, the use of two independent surveys rather than consecutive assessments of the same cohort does imply a limitation. Another limitation is the use of cross-sectional data, which does not allow us to infer causal associations. Finally, the pre-COVID survey was conducted during late autumn and early winter, while the lockdown survey was carried out during the spring. Because of the latitude of the Faroe Islands, there are large seasonal differences in the hours of daylight between these two periods, which may also have impacted our findings.

Conclusions

Our results indicate improvement in health behaviour and general well-being in the Faroe Islands during the initial four to six weeks of lockdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The differences in self-rated health and quality of life seen between a pre-COVID survey and a similar survey conducted during lockdown were accompanied by increasing activity levels related to the ABC concept. In this small island nation, the negative impact of lockdown appeared to be limited, while general well-being improved possibly by way of increased physical, mental and spiritual activity level.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants for their valued and appreciated participation. Thanks also to Professor emeritus Knud Juel for his helpful advice. We are also grateful for the statistical assistance we received from Heri á Rógvi and Heri Joensen. Finally, we would like to thank the Faroese Board of Public Health for their support, as well as Hildigunn Thomsen and Ólavur Jøkladal for technical assistance.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by the Faroese Board of Public Health.

ORCID iD: Vár Honnudóttir  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5511-0774

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5511-0774

References

- [1].World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19 (2022, accessed 13 April 2023).

- [2].Niedzwiedz CL, Green MJ, Benzeval M, et al. Mental health and health behaviours before and during the initial phase of the COVID-19 lockdown: longitudinal analyses of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2020;75:224–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Strøm M, Kristiansen MF, Christiansen DH, et al. Elimination of COVID-19 in the Faroe Islands: effectiveness of massive testing and intensive case and contact tracing. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2020;1:100011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kristiansen MF, Heimustovu BH, Borg S, et al. Epidemiology and clinical course of first wave coronavirus disease cases, Faroe Islands. Emerg Infect Dis 2021;27:749–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020;395:912–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fiorillo A, Sampogna G, Giallonardo V, et al. Effects of the lockdown on the mental health of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: results from the COMET collaborative network. Eur Psychiatry 2020;63:e87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bonati M, Campi R, Segre G. Psychological impact of the quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic on the general European adult population: a systematic review of the evidence. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2022;31:e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Varga TV, Bu F, Dissing AS, et al. Loneliness, worries, anxiety, and precautionary behaviours in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of 200,000 Western and Northern Europeans. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2021;2:100020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Clotworthy A, Dissing AS, Nguyen TL, et al. ‘Standing together – at a distance’: documenting changes in mental-health indicators in Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scand J Public Health 2021;49:79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Honnudóttir V, Hansen L, Veyhe AS, et al. Social inequality in type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Faroe Islands: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Public Health 2021;50:638–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Donovan R, Watson N, Henley N, et al. Mental health promotion scoping project: report to Healthway. Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer Control, Curtin University, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Donovan RJ, Anwar-McHenry J. Act-Belong-Commit: lifestyle medicine for keeping mentally healthy. Am J Lifestyle Med 2014;10:193–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Donovan RJ, Koushede VJ, Drane CF, et al. Twenty-one reasons for implementing the Act-Belong-Commit-‘ABCs of Mental Health’ campaign. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18: 11095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Santini ZI, Koyanagi A, Tyrovolas S, et al. The protective properties of Act-Belong-Commit indicators against incident depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment among older Irish adults: findings from a prospective community-based study. Exp Gerontol 2017;91:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Santini ZI, Nielsen L, Hinrichsen C, et al. Act-Belong-Commit indicators promote mental health and wellbeing among Irish older adults. Am J Health Behav 2018;42:31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Buhelt LP, Pisinger C, Andreasen AH. Smoking and stress in the general population in Denmark. Tob Prev Cessat 2021;7:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dettmann LM, Adams S, Taylor G. Investigating the prevalence of anxiety and depression during the first COVID-19 lockdown in the United Kingdom: systematic review and meta-analyses. Br J Clin Psychol 2022;61:757–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stock S, Bu F, Fancourt D, et al. Longitudinal associations between going outdoors and mental health and wellbeing during a COVID-19 lockdown in the UK. Sci Rep 2022;12:10580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cheval B, Sivaramakrishnan H, Maltagliati S, et al. Relationships between changes in self-reported physical activity, sedentary behaviour and health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in France and Switzerland. J Sports Sci 2021;39:699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Savage MJ, James R, Magistro D, et al. Mental health and movement behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic in UK university students: Prospective cohort study. Ment Health Phys Act 2020;19:100357. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Martinelli N, Gil S, Chevalère J, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on vulnerable people suffering from depression: two studies on adults in France. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Madsen KP, Willaing I, Rod NH, et al. Psychosocial health in people with diabetes during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark. J Diabetes Complicat 2021;35:107858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hayfield EA. Ethics in small island research: reflexively navigating multiple relations. Shima 2022;16:233–49. [Google Scholar]