Abstract

Non-invasive diagnostic method based on radiomic features in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has attracted attention. This study aimed to develop a CT image-based model for both histological typing and clinical staging of patients with NSCLC. A total of 309 NSCLC patients with 537 CT series from The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) database were included in this study. All patients were randomly divided into the training set (247 patients, 425 CT series) and testing set (62 patients, 112 CT series). A total of 107 radiomic features were extracted. Four classifiers including random forest, XGBoost, support vector machine, and logistic regression were used to construct the classification model. The classification model had two output layers: histological type (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell) and clinical stage (I, II, and III) of NSCLC patients. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were utilized to evaluate the performance of the model. Seven features were selected for inclusion in the classification model. The random forest model had the best classification ability compared with other classifiers. The AUC of the RF model for histological typing and clinical staging of NSCLC patients in the testing set was 0.700 (95% CI, 0.641–0.759) and 0.881 (95% CI, 0.842–0.920), respectively. The CT image-based radiomic feature model had good classification ability for both histological typing and clinical staging of patients with NSCLC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10278-023-00792-2.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer, CT, Radiomic feature, Histological type, Clinical stage, Classification model

Introduction

Lung cancer is a leading cause of cancer-associated death worldwide [1]. In 2020, an estimated 2.2 million new lung cancer cases and almost 1.8 million lung cancer deaths occurred worldwide [1]. Lung cancer can be divided into small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) according to pathological classification, and NSCLC accounts for approximately 85% of all lung cancer cases [2]. In addition, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified NSCLC into three main types, including adenocarcinoma (~ 40%), squamous cell carcinoma (~ 30%), and large cell (~ 10%) [3–5]. The staging and histological type of NSCLC have an important impact on the treatment and prognosis of patients [6]. Thus, the accurate identification of the histological type and staging of NSCLC patients is of great significance for treatment decisions.

Imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) are widely used for tumor screening [5]. These imaging techniques provided a non-invasive method for the diagnosis, clinical staging, survival prediction, and monitoring of treatment effects in patients with NSCLC [7–9]. Experienced physicians may be able to infer the type of lung cancer based on clinical manifestations and imaging tests, while the histological types of poorly differentiated NSCLC can only be diagnosed by pathological examination of tumor tissue. Previous studies have reported that radiomic features extracted from imaging detection images can be used for histological typing and clinical staging of patients with NSCLC [10–13]. However, radiation exposure, high cost, and lack of necessary infrastructure limit the clinical application of PET/CT, and MRI detection also has the disadvantages of long acquisition time and high cost [14, 15]. In addition, the classification performance of the model may vary depending on the number of radiomic features and modeling methods. Therefore, a model for histological typing and clinical staging of NSCLC patients based on non-invasive detection and widely used in the clinical practice needs to be explored.

Herein, this study aimed to develop CT image-based classification model that could simultaneously output the histological type and clinical stage of NSCLC patients.

Methods

Data Source and Study Patients

Data in this study were obtained from the NSCLC subset of The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) database (https://wiki.cancerimagingarchive.net/display/Public/NSCLC-Radiomics) [16]. This collection contains 721 CT series from 422 NSCLC patients. For these patient’s pre-treatment CT scans, 3D volumes of the gross tumor volume and clinical outcomes were performed by radiation oncologist. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with newly diagnosed or untreated NSCLC; (2) patients with complete histological type and clinical stage data; (3) patients with pre-treatment CT images. The exclusion criteria were those who underwent surgery or chemoradiation therapy. After screening, 113 patients were excluded, including 182 CT series missing histological type and 2 missing clinical stage. A total of 309 NSCLC patients with 537 CT series were included in this study. This NSCLC dataset was conducted according to national laws and guidelines and approved by the appropriate local trial committee at Maastricht University Medical Center (MUMC1), Maastricht, The Netherlands [16].

Image Processing and Segmentation

All patient CT images were load and processed in the original DICOM format, which contains RTSTRUCT files for mapping subregions of the lesions. All CT image files were converted to NRRD format (the 3D image file and the binary mask tag file) for image feature extraction. For each patient’s pre-treatment CT scans, the segmentation of the gross tumor volume region of interest (ROI) was drawn by a radiation oncologist and was available in the NSCLC-TCIA database.

Feature Extraction and Selection

Feature extraction was performed by pyradiomics (http://readthedocs.org/projects/pyradiomics/), which is an open-source python package. Radiomic features obtained from CT images consist of the first-order intensity statistical features, 3D-shape features, and texture features, including the first-order features (18 features), size- and shape-based features (14 features), gray level co-occurrence matrices (GLCM) features (24 features), gray level size zone matrix (GLSZM) features (16 features), gray level run length matrix (GLRLM) features (16 features), neighborhood gray-tone difference matrix (NGTDM) features (5 features), and gray level difference matrix (GLDM) features (14 features). A total of 107 radiomic features were extracted. Detailed radiomic features are shown in Supplement Table 1.

All radiomic features were normalized by removing the mean and scaling unit variance so that the processed data conformed to a standard normal distribution. A total of 109 features were screened, including 107 radiomic features as well as age and gender. Feature selection was composed of two steps. First, Pearson correlation analysis was used for the initial selection of features, and feature selection was performed by calculating the absolute value of the correlation coefficient between each feature. Features with absolute values of correlation coefficients greater than 0.9 were defined as highly correlated features and were excluded. After the initial screening, 46 features were retained. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression was used for further screening of features. LASSO regression achieves variable selection by constructing a penalty function that compresses the coefficients of the variables and makes some regression coefficients zero. The number of variables entering the model decreases as λ changes, and the optimal regression coefficient is obtained when the mean squared error (MSE) is minimized (λ = 0.87) (Supplement Fig. 1). Finally, a total of 7 features were retained, including 6 radiomic features and age. The 6 radiomic features were as 2 first-order features (original firstorder 10Percentile and original firstorder Kurtosis), 1 size- and shape-based feature (original shape Sphericity), 1 GLSZM feature (original glszm ZoneEntropy), 1 GLRLM feature (original glrlm LongRunLowGrayLevelEmphasis), and 1 GLCM feature (original glcm Correlation). The algorithms for 6 radiomic features are presented in Supplement Table 2.

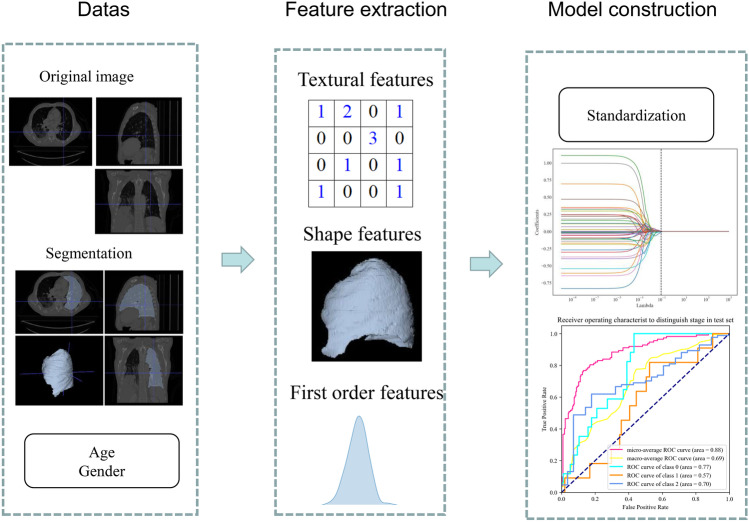

Classification Model

The constructed classification model had two output layers: (1) histological typing (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell); (2) clinical staging (I, II, and III). The 309 patients (537 CT series) were randomly grouped into the training set (247 patients, 425 CT series) and testing set (62 patients, 112 CT series) with a ratio of 8:2. The CT series of each patient was used as a whole for the analysis. Four classifiers including random forest (RF), XGBoost (XGB), support vector machine (SVM), and logistic regression (LR) were used to construct classification model. The parameters of the optimal models are shown in Supplement Table 3. Model performance was evaluated by the area under the curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The overview of the study workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of the current study

Statistical Analysis

Statistical description of the demographic characteristics of patients was described as the mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD) or number and percentage [n (%)], and the comparison between two datasets was performed by the chi-square test and Student’s t test. These statistical analyses were performed by SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Feature extraction and selection and model development were completed by Python 3.8 software (Python Software Foundation, DE, USA). The pyradiomics package was used for feature extraction, the MultiTaskLasso package was used for feature selection, the sklearn package was utilized for model development, and the multioutput package was utilized for multiple outputs of the model.

Results

Characteristics of Patients

A total of 309 NSCLC patients with 537 CT series were included in this study. The mean age of the patients was 68.65 ± 9.89 years and 209 (67.64%) patients were male. The number of patients with histological subtypes adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell was 51 (16.50%, 88 CT series), 147 (47.57%, 241 CT series), and 111 (35.92%, 208 CT series), respectively. The number of patients with clinical stages I, II, and III was 48 (15.53%, 85 CT series), 35 (11.33%, 59 CT series), and 226 (73.14%, 393 CT series), respectively. Detailed characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients

| Variables | Patients (n = 309, 537 CT series) | Training set (n = 247, 425 CT series) | Testing set (n = 62, 112 CT series) | Statistics | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | χ2 = 0.000 | 0.984 | |||

| Male | 209 (67.64%) | 167 (67.61%) | 42 (67.74%) | ||

| Female | 100 (32.36%) | 80 (32.39%) | 20 (32.26%) | ||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 68.65 ± 9.89 | 68.89 ± 9.83 | 67.72 ± 10.07 | t = 0.830 | 0.407 |

| Histological type, n (%) | χ2 = 0.047 | 0.977 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 51 (16.50%) | 41 (16.60%) | 10 (16.13%) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 147 (47.57%) | 118 (47.77%) | 29 (46.77%) | ||

| Large cell | 111 (35.92%) | 88 (35.63%) | 23 (37.10%) | ||

| Stage, n (%) | χ2 = 0.216 | 0.898 | |||

| I | 48 (15.53%) | 38 (15.38%) | 10 (16.13%) | ||

| II | 35 (11.33%) | 29 (11.74%) | 6 (9.68%) | ||

| III | 226 (73.14%) | 180 (72.87%) | 46 (74.19%) | ||

Comparison of Different Classification Models

Table 2 shows the classification performance of the four models for histological type and staging of NSCLC patients in the training set and testing set. The AUC of the RF, XGB, SVM, and LR models for histological typing of NSCLC patients in the testing set was 0.700 (95% CI, 0.641–0.759), 0.677 (95% CI, 0.617–0.737), 0.637 (95% CI, 0.576–0.699), and 0.631 (95% CI, 0.568–0.694), respectively. For the staging of NSCLC patients, the AUC of the RF, XGB, SVM, and LR models in the testing set was 0.881 (95% CI, 0.842–0.920), 0.858 (95% CI, 0.809–0.906), 0.842 (95% CI, 0.794–0.890), and 0.670 (95% CI, 0.609–0.732), respectively. The receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves of different models for histological typing and staging of NSCLC patients in the training set and testing set are shown in Fig. 2. DeLong test showed that the RF model presented good classification performance compared to other models in terms of both histological type and staging of NSCLC patients (Table 3). Therefore, the RF model was chosen to classify the histological type and stage of NSCLC patients.

Table 2.

Performances of the models for histological type and staging of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients in the training set and testing set

| Model | Dataset | Output | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | Accuracy (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | Training set | Histological type | 0.635 (0.590–0.681) | 0.793 (0.766–0.820) | 0.605 (0.560–0.651) | 0.813 (0.786–0.840) | 0.758 (0.730–0.786) | 0.740 (0.716–0.764) |

| Stage | 0.800 (0.762–0.838) | 0.840 (0.815–0.865) | 0.714 (0.674–0.755) | 0.894 (0.872–0.915) | 0.900 (0.883–0.917) | 0.827 (0.806–0.847) | ||

| Testing set | Histological type | 0.527 (0.434–0.619) | 0.750 (0.693–0.807) | 0.513 (0.422–0.604) | 0.760 (0.704–0.816) | 0.700 (0.641–0.759) | 0.676 (0.626–0.726) | |

| Stage | 0.750 (0.670–0.830) | 0.875 (0.832–0.918) | 0.750 (0.670–0.830) | 0.875 (0.832–0.918) | 0.881 (0.842–0.920) | 0.833 (0.793–0.873) | ||

| XGB | Training set | Histological type | 0.739 (0.697–0.781) | 0.689 (0.658–0.721) | 0.543 (0.503–0.584) | 0.841 (0.814–0.868) | 0.764 (0.736–0.791) | 0.706 (0.681–0.731) |

| Stage | 0.795 (0.757–0.834) | 0.842 (0.818–0.867) | 0.716 (0.675–0.757) | 0.892 (0.870–0.913) | 0.889 (0.870–0.908) | 0.827 (0.806–0.847) | ||

| Testing set | Histological type | 0.661 (0.573–0.748) | 0.589 (0.525–0.654) | 0.446 (0.370–0.521) | 0.776 (0.714–0.839) | 0.677 (0.617–0.737) | 0.613 (0.561–0.665) | |

| Stage | 0.750 (0.670–0.830) | 0.875 (0.832–0.918) | 0.750 (0.670–0.830) | 0.875 (0.832–0.918) | 0.858 (0.809–0.906) | 0.833 (0.793–0.873) | ||

| SVM | Training set | Histological type | 0.765 (0.724–0.805) | 0.552 (0.518–0.585) | 0.460 (0.424–0.497) | 0.824 (0.793–0.856) | 0.712 (0.683–0.741) | 0.623 (0.596–0.649) |

| Stage | 0.753 (0.712–0.794) | 0.853 (0.829–0.877) | 0.719 (0.677–0.761) | 0.873 (0.851–0.896) | 0.852 (0.829–0.876) | 0.820 (0.799–0.841) | ||

| Testing set | Histological type | 0.741 (0.660–0.822) | 0.504 (0.439–0.570) | 0.428 (0.358–0.497) | 0.796 (0.729–0.862) | 0.637 (0.576–0.699) | 0.583 (0.531–0.636) | |

| Stage | 0.750 (0.670–0.830) | 0.875 (0.832–0.918) | 0.750 (0.670–0.830) | 0.875 (0.832–0.918) | 0.842 (0.794–0.890) | 0.833 (0.793–0.873) | ||

| LR | Training set | Histological type | 0.826 (0.790–0.862) | 0.375 (0.343–0.408) | 0.398 (0.366–0.430) | 0.812 (0.773–0.850) | 0.634 (0.602–0.666) | 0.525 (0.498–0.553) |

| Stage | 0.692 (0.648–0.736) | 0.705 (0.674–0.735) | 0.539 (0.498–0.581) | 0.821 (0.793–0.848) | 0.741 (0.712–0.771) | 0.700 (0.675–0.726) | ||

| Testing set | Histological type | 0.821 (0.750–0.892) | 0.353 (0.290–0.415) | 0.388 (0.326–0.450) | 0.798 (0.719–0.877) | 0.631 (0.568–0.694) | 0.509 (0.455–0.562) | |

| Stage | 0.696 (0.611–0.782) | 0.487 (0.421–0.552) | 0.404 (0.335–0.473) | 0.762 (0.692–0.832) | 0.670 (0.609–0.732) | 0.557 (0.503–0.610) |

RF random forest, XGB XGBoost, SVM support vector machine, LR logistic regression, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value, AUC area under the curve, 95% CI 95% confidence interval

Fig. 2.

The receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves of different models for histological typing and staging of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients in the training set and testing set. A Histological typing in the training set; B histological typing in the testing set; C staging in the training set; D staging in the testing set. RF, random forest; XGB, XGBoost; SVM, support vector machine; LR, logistic regression

Table 3.

DeLong test for comparison of AUC between different models

| Outcome | Models | Dataset | AUC (95% CI) | Statistics | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histological type | RF | Training set | 0.758 (0.730–0.786) | Ref | |

| XGB | 0.764 (0.736–0.791) | 1.47380 | 0.141 | ||

| SVM | 0.712 (0.683–0.741) | −6.68246 | < 0.001 | ||

| LR | 0.634 (0.602–0.666) | − 6.96457 | < 0.001 | ||

| RF | Testing set | 0.700 (0.641–0.759) | Ref | ||

| XGB | 0.677 (0.617–0.737) | −2.89855 | 0.004 | ||

| SVM | 0.637 (0.576–0.699) | −3.97099 | < 0.001 | ||

| LR | 0.631 (0.568–0.694) | −2.03697 | 0.042 | ||

| Stage | RF | Training set | 0.900 (0.883–0.917) | Ref | |

| XGB | 0.889 (0.870–0.908) | −2.73597 | 0.006 | ||

| SVM | 0.852 (0.829–0.876) | −6.73715 | < 0.001 | ||

| LR | 0.741 (0.712–0.771) | −10.30520 | < 0.001 | ||

| RF | Testing set | 0.881 (0.842–0.920) | Ref | ||

| XGB | 0.858 (0.809–0.906) | −2.39091 | 0.017 | ||

| SVM | 0.842 (0.794–0.890) | −3.24426 | 0.001 | ||

| LR | 0.670 (0.609–0.732) | −6.50979 | < 0.001 |

AUC area under the curve, RF random forest, XGB XGBoost, SVM support vector machine, LR logistic regression

Performance of the RF Classification Model

Figure 3 presents the importance of the 7 features in the RF classification model. The most important variables in the RF model were age, radiomic features of original glrlm LongRunLowGrayLevelEmphasis, original firstorder 10Percentile, and original firstorder Kurtosis, with the importance ratio of variables being 0.198, 0.196, 0.185, and 0.121, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Feature importance of the random forest model

The AUC, accuracy, and specificity of the RF model for the histological typing of NSCLC patients in the testing set were 0.700 (95% CI, 0.641–0.759), 0.676 (95% CI, 0.626–0.726), and 0.750 (95% CI, 0.693–0.807), respectively. Similarly, the AUC, accuracy, and specificity of the RF model for the staging of NSCLC patients in the testing set were 0.881 (95% CI, 0.842–0.920), 0.833 (95% CI, 0.793–0.873), and 0.875 (95% CI, 0.832–0.918), respectively (Table 2).

Discussion

This study constructed a model for histological typing and clinical staging of NSCLC patients based on radiomic features extracted from CT images. We compared the classification performances of different classifiers for histological typing and clinical staging of NSCLC patients. The results indicated that compared with other classifiers, the RF model had better classification performance for histological typing and clinical staging of NSCLC patients, and the AUC of the RF model in the testing set was 0.700 and 0.881, respectively. Among the features incorporated into the classification model, first-order and texture radiomic features may play an important role in model performance.

Biopsy is the standard for histological classification, but it also has some drawbacks such as invasively, inability to provide spatial information, lack of systemic assessment, and possible complications [17]. Radiomic of tumors can noninvasively and repeatedly characterize lesions by extracting many quantitative features, such as pixel intensity, shape, and texture, to transform standard clinical imaging data into higher-dimensional, mineable data [18–20]. Our study constructed a histological typing and clinical staging model for NSCLC patients based on radiomic features extracted from CT images. CT is the more commonly used imaging technique in lung cancer patients, which can provide information on tumor location, size, shape, vacuoles, necrosis, calcification, and blood supply [21]. Our results found that first-order and texture radiomic features had an important role in our classification model. The importance of texture features in the model can also be found in previous studies [10, 11, 22]. This may be related to the fact that radiomic features of imaging can reflect tumor phenotypic differences, such as irregular shapes and heterogeneity. In addition, we considered patient demographic characteristics such as age and gender. Sex differences in NSCLC have been widely reported [23, 24]. The higher incidence of the adenocarcinoma histological subtype was more common in women [24]. However, our results showed that age contributed significantly to the model, but gender was not included in the model.

Studies of radiomic features for histological typing or clinical staging of patients with NSCLC have been reported [10, 11, 13, 25, 26]. Han et al. developed a model based on PET/CT images to distinguish histological subtypes of NSCLC patients, and the AUC of the model reached 0.824 [10]. Yu et al. constructed a CT image-based radiomic feature model for clinical staging of NSCLC patients, with an AUC of 0.82 [11]. Tang et al. developed a radiomic feature model based on MRI images for histological typing of NSCLC patients, and the AUC of their model reach 0.819 [13]. Guo et al. used a 3D deep learning approach (ProNet) to extract radiomic features of CT images used to distinguish subtypes of NSCLC, and the AUC of their model was 0.840 [27]. Furthermore, several studies have used radiomic features combined with clinical features and tumor markers to construct models for histological typing of NSCLC [28, 29]. Ren et al. used a combined model consisting of 2 clinical factors, 2 tumor markers, 7 PET radiomics, and 3 CT radiomic parameters in predicting NSCLC subtypes, and the model achieved an AUC of 0.901 on the validation set [28]. The combined use of different machine learning algorithms was also a way to improve the performance of the model. Song et al. used a combined Bagging-AdaBoost-SVM model to distinguish subtypes of NSCLC, and the AUC of their model was 0.815 [30]. Our model was constructed using 6 radiomic features from CT images and age. Our model can simultaneously classify the histological type and clinical stage of NSCLC patients, and the AUC of the model in the testing set was 0.700 and 0.881, respectively. Compared with previous studies, our model showed an improvement in staging performance for NSCLC, but no significant improvement in classification of histological type. In the terms of histological typing, our model performed classification of 3 subtypes of NSCLC, whereas previous studies only performed classification of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Moreover, our model was constructed based on CT images, which increased the range of clinical use of the model. Our model can simultaneously output the results of histological type and clinical stage of NSCLC patients compared with the previous single-output model. In addition, many reasons may affect the performance of the model, including differences in image types, feature extraction algorithms, feature selected methods, number of selected features, cohort size, and classifiers. Zhang et al. found that the performance of models based on radiomic features extracted from the same CT image dataset varied with the number of features and classifiers [31].

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small, which may affect the training effect of the model. Better predictive models may require studies with larger sample sizes. Second, there was a lack of external validation to confirm the generalizability of our results. Despite internal validation, external validation is required for the model to be used in clinical practice. Third, CT images used in this study were extracted from a single center. Model training with images collected from multiple centers may enhance the robustness and generalization ability of the model. Fourth, the performance comparison of models based on different images of the same patient such as PET/CT, CT, and MRI cannot be achieved due to the lack of corresponding images in the database. Fifth, the imbalance in the sample size of each histological subtype and stage may affect the accuracy of the results.

Conclusions

A model based on the radiomic features of CT images for histological typing and clinical staging of NSCLC patients was constructed. Compared with other classifiers, the random forest model had the best classification ability. This model may provide clinicians with a non-invasive tool for histological typing and clinical staging of NSCLC patients. In addition, better classification models that can be widely used in clinical practice may remain to be further explored.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

JL designed the study and wrote the manuscript. YY, XZ, ZW, and SL collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. JL critically reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This is an observational study. The XYZ Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sung H, et al.: Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 71:209–249, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Thai AA, Solomon BJ, Sequist LV, Gainor JF, Heist RS. Lung cancer. Lancet (London, England) 2021;398:535–554. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG. Introduction to The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus, and Heart. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2015;10:1240–1242. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholson AG, et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Advances Since 2015. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2022;17:362–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duma N, Santana-Davila R, Molina JR. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Epidemiology, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2019;94:1623–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ettinger DS, et al.: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 5.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN 15:504–535, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Wu J, et al. Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Quantitative Imaging Characteristics of (18)F Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT Allow Prediction of Distant Metastasis. Radiology. 2016;281:270–278. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016151829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Timmeren JE, et al. Longitudinal radiomics of cone-beam CT images from non-small cell lung cancer patients: Evaluation of the added prognostic value for overall survival and locoregional recurrence. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2019;136:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Timmeren JE, et al. Survival prediction of non-small cell lung cancer patients using radiomics analyses of cone-beam CT images. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2017;123:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han Y, et al. Histologic subtype classification of non-small cell lung cancer using PET/CT images. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2021;48:350–360. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04771-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu L, et al. Prediction of pathologic stage in non-small cell lung cancer using machine learning algorithm based on CT image feature analysis. BMC cancer. 2019;19:464. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5646-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ubaldi L, et al. Strategies to develop radiomics and machine learning models for lung cancer stage and histology prediction using small data samples. Physica medica : PM : an international journal devoted to the applications of physics to medicine and biology : official journal of the Italian Association of Biomedical Physics (AIFB) 2021;90:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2021.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang X, et al. Elaboration of a multimodal MRI-based radiomics signature for the preoperative prediction of the histological subtype in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Biomedical engineering online. 2020;19:5. doi: 10.1186/s12938-019-0744-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liam CK, Andarini S, Lee P, Ho JC, Chau NQ, Tscheikuna J. Lung cancer staging now and in the future. Respirology (Carlton, Vic) 2015;20:526–534. doi: 10.1111/resp.12489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magome T, et al. Evaluation of Functional Marrow Irradiation Based on Skeletal Marrow Composition Obtained Using Dual-Energy Computed Tomography. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2016;96:679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.06.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aerts HJ, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nature communications. 2014;5:4006. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirienko M, et al. Ability of FDG PET and CT radiomics features to differentiate between primary and metastatic lung lesions. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2018;45:1649–1660. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-3987-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chetan MR, Gleeson FV. Radiomics in predicting treatment response in non-small-cell lung cancer: current status, challenges and future perspectives. European radiology. 2021;31:1049–1058. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07141-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beig N, et al. Perinodular and Intranodular Radiomic Features on Lung CT Images Distinguish Adenocarcinomas from Granulomas. Radiology. 2019;290:783–792. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coroller TP, et al. Radiomic-Based Pathological Response Prediction from Primary Tumors and Lymph Nodes in NSCLC. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2017;12:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tailor TD, Schmidt RA, Eaton KD, Wood DE, Pipavath SN. The Pseudocavitation Sign of Lung Adenocarcinoma: A Distinguishing Feature and Imaging Biomarker of Lepidic Growth. Journal of thoracic imaging. 2015;30:308–313. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyun SH, Ahn MS, Koh YW, Lee SJ. A Machine-Learning Approach Using PET-Based Radiomics to Predict the Histological Subtypes of Lung Cancer. Clinical nuclear medicine. 2019;44:956–960. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu LH, et al. Sex-associated differences in non-small cell lung cancer in the new era: is gender an independent prognostic factor? Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2009;66:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paggi MG, Vona R, Abbruzzese C, Malorni W. Gender-related disparities in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer letters. 2010;298:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.E L, Lu L, Li L, Yang H, Schwartz LH, Zhao B: Radiomics for Classification of Lung Cancer Histological Subtypes Based on Nonenhanced Computed Tomography. Academic radiology 26:1245–1252, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Shen H, et al. A subregion-based positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) radiomics model for the classification of non-small cell lung cancer histopathological subtypes. Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery. 2021;11:2918–2932. doi: 10.21037/qims-20-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Y, et al. Histological Subtypes Classification of Lung Cancers on CT Images Using 3D Deep Learning and Radiomics. Academic radiology. 2021;28:e258–e266. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren C, et al. Machine learning based on clinico-biological features integrated 18F-FDG PET/CT radiomics for distinguishing squamous cell carcinoma from adenocarcinoma of lung. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2021;48:1538–1549. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05065-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao H, et al. The Machine Learning Model for Distinguishing Pathological Subtypes of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Frontiers in oncology. 2022;12:875761. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.875761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song F, et al. Radiomics feature analysis and model research for predicting histopathological subtypes of non-small cell lung cancer on CT images: A multi-dataset study. Medical physics. 2023;1–15:2023. doi: 10.1002/mp.16233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Oikonomou A, Wong A, Haider MA, Khalvati F. Radiomics-based Prognosis Analysis for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Scientific reports. 2017;7:46349. doi: 10.1038/srep46349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.