Abstract

We report orthotopic (life-supporting) survival of genetically engineered porcine cardiac xenografts (with six gene modifications) for almost 9 months in baboon recipients. This work builds on our previously reported heterotopic cardiac xenograft (three gene modifications) survival up to 945 days with an anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody-based immunosuppression. In this current study, life-supporting xenografts containing multiple human complement regulatory, thromboregulatory, and anti-inflammatory proteins, in addition to growth hormone receptor knockout (KO) and carbohydrate antigen KOs, were transplanted in the baboons. Selective “multi-gene” xenografts demonstrate survival greater than 8 months without the requirement of adjunctive medications and without evidence of abnormal xenograft thickness or rejection. These data demonstrate that selective “multi-gene” modifications improve cardiac xenograft survival significantly and may be foundational for paving the way to bridge transplantation in humans.

Keywords: cardiac xenotransplantation, CRISPR, heart failure, pig heart, xenotransplantation

1 |. INTRODUCTION

We have reported previously almost 3-year survival of genetically engineered (GE) pig cardiac xenografts in an abdominal, nonload bearing heterotopic heart transplantation (HHTx) in baboons. Initial gene modifications in this model targeted hyperacute antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) and dysregulation of thrombosis, which included deletion of a carbohydrate antigen (α1,3-galactose) and insertion of human complement inhibitory protein (hCD46) along with human thrombomodulin, an inhibitor of thrombin (hTBM). We demonstrated the use of a non-B cell depleting, anti-CD40 (2C10R4) primatized monoclonal antibody (mAb)-based immunosuppressive regimen that led to rejection-free survival of 945 days,1 which has been reliably reproduced.2–6

Our initial efforts to translate these results in a life-sustaining orthotopic heart transplantation (OHTx) failed within 48 h due to perioperative cardiac xenograft dysfunction (PCXD).7,8 Recently, Längin et al. overcame PCXD in OHTx with the same GE xenografts and immunosuppression as in our HHTx, with the addition of nonischemic cardiac preservation and anti-inflammatory agents.3 However, survival was still limited due to observed diastolic failure from abnormal cardiac growth within 1 month. This posttransplantation xenograft growth is poorly understood, but 6-month recipient survival was achieved after the additional administration of temsirolimus (inhibitor of growth by mTOR, but also an immunosuppressive agent) along with strict blood pressure and heart rate control to prevent this growth. Withdrawing temsirolimus resulted in continuation of growth and ultimately xenograft failure. Recently, we observed that this growth is independent of heart rate and afterload reduction, suggesting an etiology separate from physiologic mismatch.9

Xenograft rejection is a result of endothelial cell activation by preformed antibodies against porcine antigens.10,11 This leads to hyperacute rejection (HAR) within minutes of transplantation, characterized by endothelial damage by antibody deposition, complement activation and intravascular thrombosis.12 However, several scientific discoveries have led to the ability to produce targeted modifications to porcine xenograft donors that reduce their immunogenicity and abrogate HAR. Knockout (KO) of xenogeneic carbohydrate antigens α1,3-galactose (Gal),13 SDa blood group antigen, (SDa)14,15 and N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc)16 have been shown to reduce antibody binding and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) against nonhuman primates and human sera alone and in combination.17 Rejection is further prevented by the additional expression of human complement regulatory proteins hCD46 and decay-accelerating factor (hDAF).18,19 Thrombotic microangiopathy and consumptive coagulopathy also play a role in rejection, possibly due to incompatible factors of thrombosis between porcine endothelial cells and recipient serum.20 Addition of factors that promote anti-coagulation, such as human thrombomodulin (hTBM), have been shown to prevent coagulation dysregulation and survival.1,3,21,22 Human anti-inflammatory (i.e., heme oxygenase-1 [hHO-1]) and anti-phagocytosis genes (i.e., hCD47), respectively, have also demonstrated a role in abrogating transplant rejection in vitro.23–25 Only recently, advances in genetic engineering techniques afforded the opportunity to produce porcine donors with all of these targeted modifications in combination.26,27

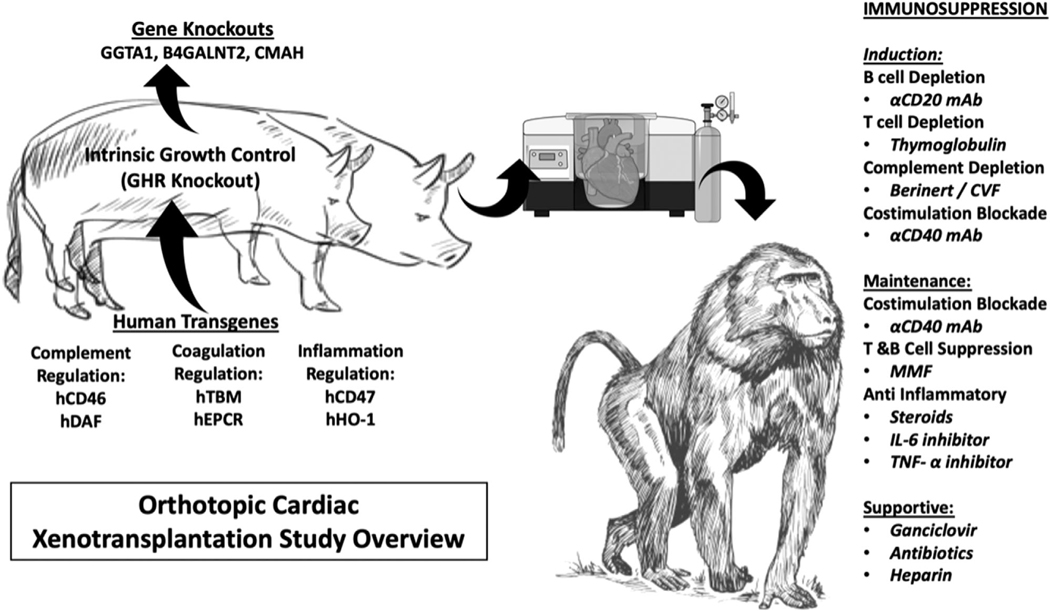

In this study, we examine the utility of “multi-gene” xenografts up to nine genetic modifications from GE pigs (Figure 1, Table 1). We also chronicle our experience with xenografts of less than nine-gene modifications, as very limited production and availability of these pigs limit our ability to test every gene iteration or have a larger number of transplants in each group, but still provide an opportunity to evaluate several genetic constructs of less than nine-genes.

FIGURE 1. Study overview.

Pig-to-baboon xenotransplantation was performed with genetically modified pigs of various combinations. An anti-CD40 mAb-based regimen was used, and xenograft survival was measured. After euthanasia, the graft was explanted and examined. Multimodal analyses were performed on both the graft and the recipient

TABLE 1.

Groups by knockout and human transgene expression. Human transgenes are categorized by thromboregulatory, complement regulation, and anti-inflammatory proteins. GGTA1 = α1,3-galactosyltransferase, β4GalNT2 = β1,4-N-acetylgalactosyltransferase, CMAH = CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase, TBM = thrombomodulin, EPCR = endothelial protein C receptor, DAF = decay accelerating factor, HO1 = hemeoxygenase, GHRKO = growth hormone receptor knockout. CMAH (−/−) = knockout homozygous at this locus, CMAH (+/−) = knockout heterozygous at this locus

| Gene Knockout/Knockin # | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Carbohydrate enzyme knockout | Other | Thromboregulatory | Complement regulation | Anti-inflammatory | |||||||

| B32608 | Group 1 | GGTA1 | TBM | CD46 | |||||||

| B32987 | GGTA1 | TBM | CD46 | ||||||||

| B33422 | GGTA1 | TBM | CD46 | ||||||||

| B32628 | GGTA1 | TBM | CD46 | ||||||||

| B33167 | Group 2 | GGTA1 | CD46 | DAF | |||||||

| B32638 | GGTA1 | β4GalNT2 | CMAH (−/−) | CD46 | DAF | ||||||

| B33156 | GGTA1 | β4GalNT2 | CMAH (−/−) | ||||||||

| B33060 | GGTA1 | β4GalNT2 | CMAH (−/−) | ||||||||

| B33121 | Group 3 | GGTA1 | β4GalNT2 | CMAH (+/−) | TBM | EPCR | CD46 | DAF | CD47 | HO1 | |

| B32988 | GGTA1 | β4GalNT2 | CMAH (+/−) | TBM | EPCR | CD46 | DAF | CD47 | HO1 | ||

| B33130 | Group 4 | GGTA1 | β4GalNT2 | GHRKO | TBM | EPCR | CD46 | CD47 | |||

| B32863 | GGTA1 | β4GalNT2 | GHRKO | TBM | EPCR | CD46 | CD47 | ||||

All baboon recipients were treated with our previously described anti-CD40-based IS regimen and transplanted with a life-supporting cardiac xenograft from a GE pig without additional immunosuppression or drugs to control cardiac growth and blood pressure. Here, we examine which “multi-gene” xenograft, in combination with our CD-40 mAb-based regimen, might produce survival conducive for initial human clinical trials.

2 |. RESULTS

2.1 |. GE pigs with relevant gene editing provide less immunogenic donor hearts for transplantation

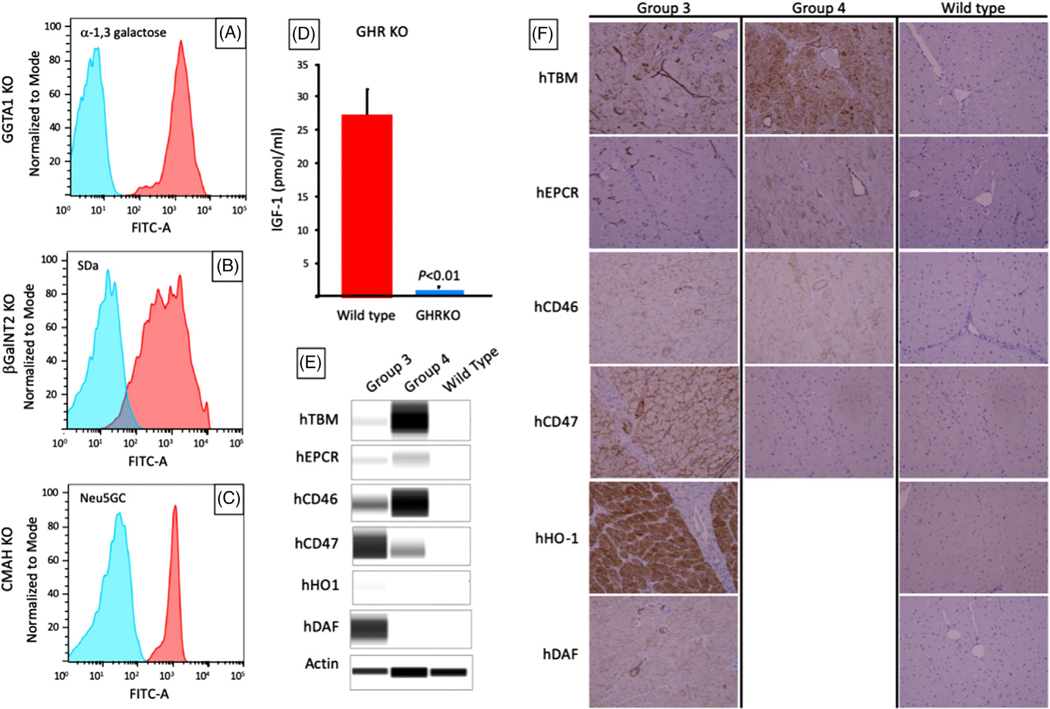

Correct, single copy targeting of transgene constructs to landing pads was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), Southern blot, and digital drop PCR. KO of α−1,3-galactosyltransferase (GGTA1, the enzyme responsible for synthesis of Gal) was confirmed by PCR for the presence of a disruptive NeoR insertion in exon 9.28 KO of genes encoding β1,4-N-acetylgalactosyltransferase (β4GalNT2, the enzyme responsible for synthesis of SDa), complete metabolic profile (CMP)-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH, the enzyme responsible for synthesis of Neu5Gc), and growth hormone receptor (GHR) were assessed by Next-Gen DNA sequencing (MiSeq, Illumina) for the presence of large or frameshifting indels. Phenotypes of GGTA1KO, B4GALNT2KO, and CMAHKO KO were confirmed by flow cytometry of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) stained with IB4 lectin, DBA lectin, and anti-Neu5Gc respectively, to reveal the absence of xenogeneic carbohydrate residues catalyzed by the knocked-out gene product (Figure 2A–C). Growth hormone receptor knockout (GHRKO) phenotype was determined by demonstrating reduced serum IGF-1 levels (Figure 2D) and body weight29 at 142 days of age (65.77 ± 9.17 kg vs. 32.27 ± 1.20 kg for GHR wild-type and GHRKO pigs, respectively; Mean ± SD; p < .01). Expression of individual transgenes was confirmed in tail biopsies of donor pigs prior to transplantation by western blot (Figure 2E) and demonstrated continued expression in explanted heart tissues by immunohistochemical staining (Figure 2F).

FIGURE 2. Xenograft phenotypes in long-term survivors.

(A–C) Flow cytometry showing the absence of a-1,3 galactose, SDa, and Neu5Gc antigens after knockout of GGTA1, B4GalNT2, and CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH), respectively in Group 2 pigs. Knockouts are shown in blue, wild types in red. CMAHKO (−/−) is shown in blue, whereas CMAHKO (+/−) has similar staining to wild type (not shown). (D) Serum IGF-1 levels in GHR knockout donors in Group 4 (blue) versus wild type pigs (red); (E) western blot of human transgenes expression in tail biopsies of Group 3 and 4 donor pigs. (F) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of explanted heart xenografts from Group 3 and 4 donors showing expression of human transgenes (x200)

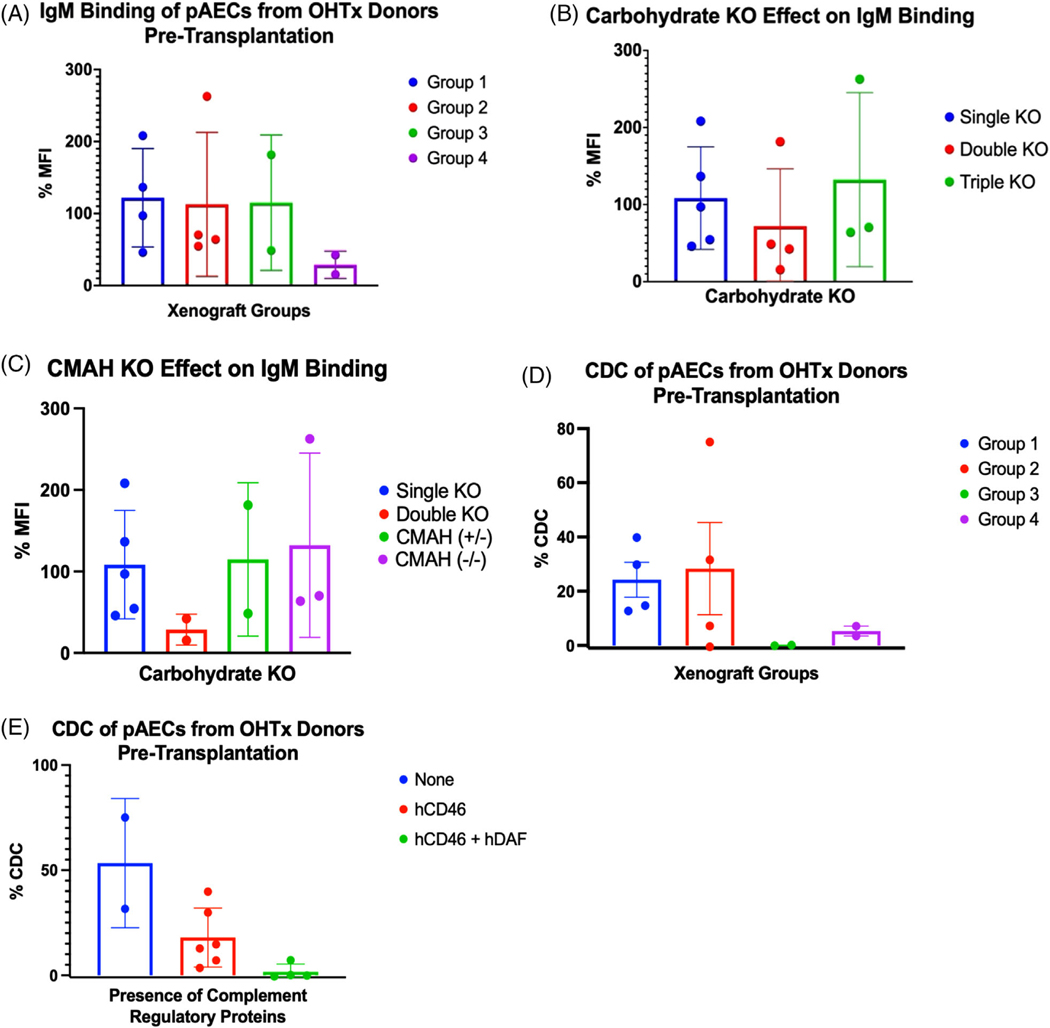

Multiple gene edits reduced the immunogenicity of cardiac xenografts as measured by antibody binding and CDC assays. Porcine aortic endothelial cells (pAECs) from OHTx pig donors with double carbohydrate KO (GGTA1KO and β4GalNT2KO) had reduced binding, compared to single carbohydrate KO (GGTA1KO), but paradoxically worsened with triple carbohydrate KO xenografts (GGTA1KO, β4GalNT2KO, and CMAHKO) (Figure 3A,B). CMAHKO (−/+) and CMAHKO (−/−) pAECs showed similar total IgM mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) by flow cytometry (Figure 3C), despite CMAHKO (−/−) having reduced anti-Neu5Gc staining by flow cytometry (Figure 2B). Group 3 xenografts produced the least amount of CDC, followed by Group four xenografts. CDC was elevated in Groups 1 and 2 and was markedly reduced with the addition of hCD46 and hDAF (Figure 3D,E).

FIGURE 3. Characterization of multi-gene cardiac xenografts.

(A) IgM binding of pAECs from either xenograft donors or donor litter mates exposed to serum from Groups 1–4 recipients prior to OHTx. (B) IgM binding from panel a, grouped by single, double or triple knockout (KO) xenografts. (C) IgM binding from (A) and (B), grouped by CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH) (+/−) versus (−/−). Single = GGTA1KO, double = GGTA1KO and B4GalNT2, triple = GGTA1KO, B4GalNT2, and CMAHKO. %MFI = MFI as a percent of control. Complement dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) and IgM binding were performed as triplicates and presented here as an average of triplicates. (D) CDC measured on pig aortic endothelial cells (pAECs) from either xenograft donors or donor litter mates exposed to serum from Group 1–4 recipients prior to orthotopic transplantation (OHTx). (E) CDC from panel (D), grouped by complement regulatory proteins hCD46 and hDAF

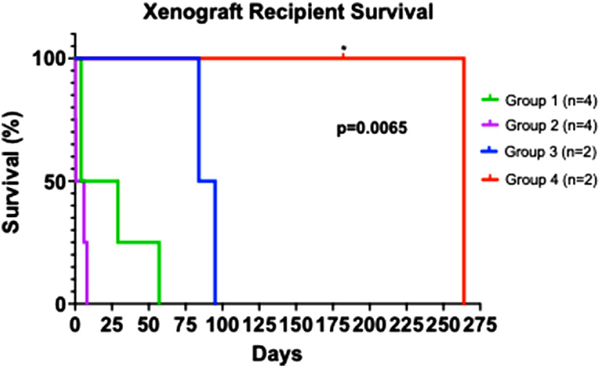

2.2 |. Consistent long-term survival of cardiac xenografts by progressive elimination of immunogenic pig antigens and expression of human transgenes

All recipients were comfortably weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) (Table S1), without any elaborative supportive measures, after successful life supporting OHTx from GE pigs with 3–9 gene modifications. Improved graft survival with progressive genetic modifications is summarized in Figure 4. Group 1 xenografts, with the gene construct similar to one used in our HHTx model (i.e., GGTA1KO, hTBM, and hCD46 [n = 4]), survived up to 57 days (mean = 23.5 ± 25.3). Single KO or triple knockout (TKO) xenografts in Group 2, without thromboregulatory proteins failed within 1 week. Survival did not improve despite the addition of complement regulatory proteins (CRP; hCD46 and hDAF) (Group 2, n = 4).

FIGURE 4. Recipient survival of Groups 1–4.

Survival defined as time after transplantation before requiring euthanasia for deteriorating condition. * = death censored for euthanasia required. All other grafts contained histologic evidence of cardiac abnormalities contributing to deterioration requiring euthanasia. p = .0065 by Log-rank (Mantel-cox) test, suggesting a significant difference in survival between Groups 1–4

GE pigs with nine gene modifications (GGTA1KO, B4GalNT2, CMAHKO, hTBM, hEPCR, hCD46, hDAF, hCD47, hHO1, referred to as Group 3) or seven gene modifications (GGTA1KO, B4GalNT2, hTBM, hEPCR, hCD46, hCD47, and GHRKO, referred to as Group 4) demonstrated significant prolongation of xenograft survival. Cardiac xenograft survival in Groups 3 (n = 2) was extended to a mean of 89.5 ± 7.8 days. In Group 4 (n = 2), xenograft survival was markedly prolonged to a mean of 223 ± 58.0 days. One xenograft functioned for 264 days prior to explantation (B33130), which is the longest reported life supporting xenograft survival to date. The other recipient (B32863) from Group 4 demonstrated reduced food intake from gingivitis and had to be euthanized on postoperative day (POD) #182 for weight loss over the allowed limit of our institution’s protocol. Overall, cardiac xenograft function was excellent on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) at the time of euthanasia (Videos 1 and 2).

2.3 |. Elimination of GHR gene from donor GE pigs resulted in cardiac xenografts with reduced growth and improved survival

To address intrinsic posttransplantation xenograft growth, pig donors’ GHR was knocked out in addition to the other genetic modifications as previously mentioned. As in Groups 1 and 2, adjuncts to reduce posttransplantation xenograft growth (temsirolimus and heart rate and afterload reducers) were not employed.

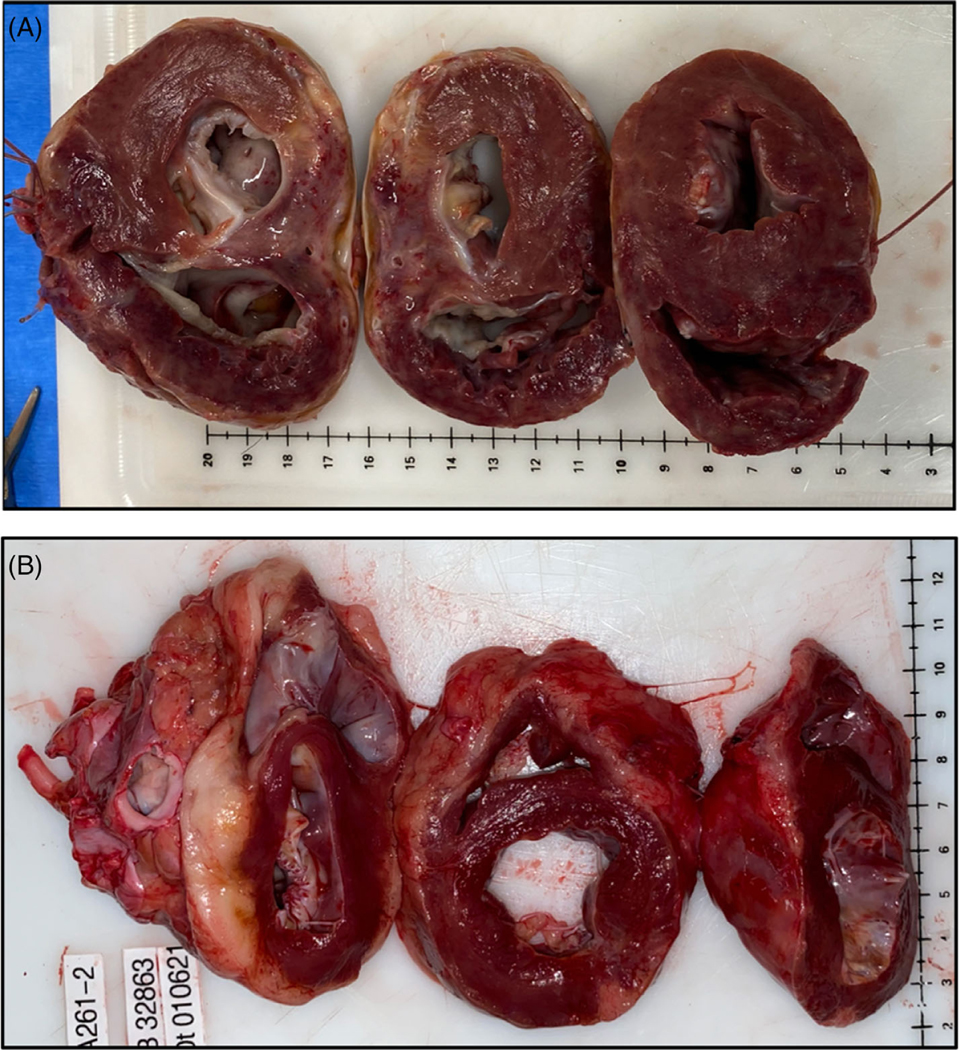

All xenografts from Groups 3 and 4 exhibited preserved systolic function posttransplantation and survival measured in months, but Group 3 xenografts (which have intact GHR) developed lower extremity edema, dyspnea, and lethargy by POD #84 and 95 and were subsequently euthanized. On TTE, significant ventricular wall thickening was observed. Cross-sections of the explanted hearts confirmed biventricular wall thickening (Figure 5A). Thus, ventricular wall thickening in Group 3 was delayed until POD #55, with additional gene modifications, but ultimately not prevented. Group 4 xenografts, that also lack functional GHR (GHRKO), continued to function without myocardial thickening on TTE for up to 264 days prior to explantation. No apparent xenograft thickness was seen on cross-sections of the explanted xenograft from this group either (Figure 5B). The explanted xenograft’s gross appearance was similar to a naive pig heart. Mean arterial pressures and heart rates were elevated compared to pig’s native ranges in Groups 3 and 4, consistent with prior studies.9 Despite the presence of this physiologic mismatch, and the absence of treatment, significant graft growth was not observed in Group 4.

FIGURE 5 |. GHRKO versus non-GHRKO xenografts.

(A) non-GHRKO grafts (Group 3) exhibited biventricular wall thickening. Here, B33121 survived 84 days prior to requiring euthanasia for symptoms of diastolic heart failure. (B) GHRKO graft (Group 4) exhibiting normal histology without thickening at 182 days post-transplantation. This animal (B32863) was euthanized for weight loss as required by our institutional animal care committee but was exhibiting excellent graft function

2.4 |. Histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation of xenografts demonstrates the advantage of multigene modifications of the cardiac xenograft

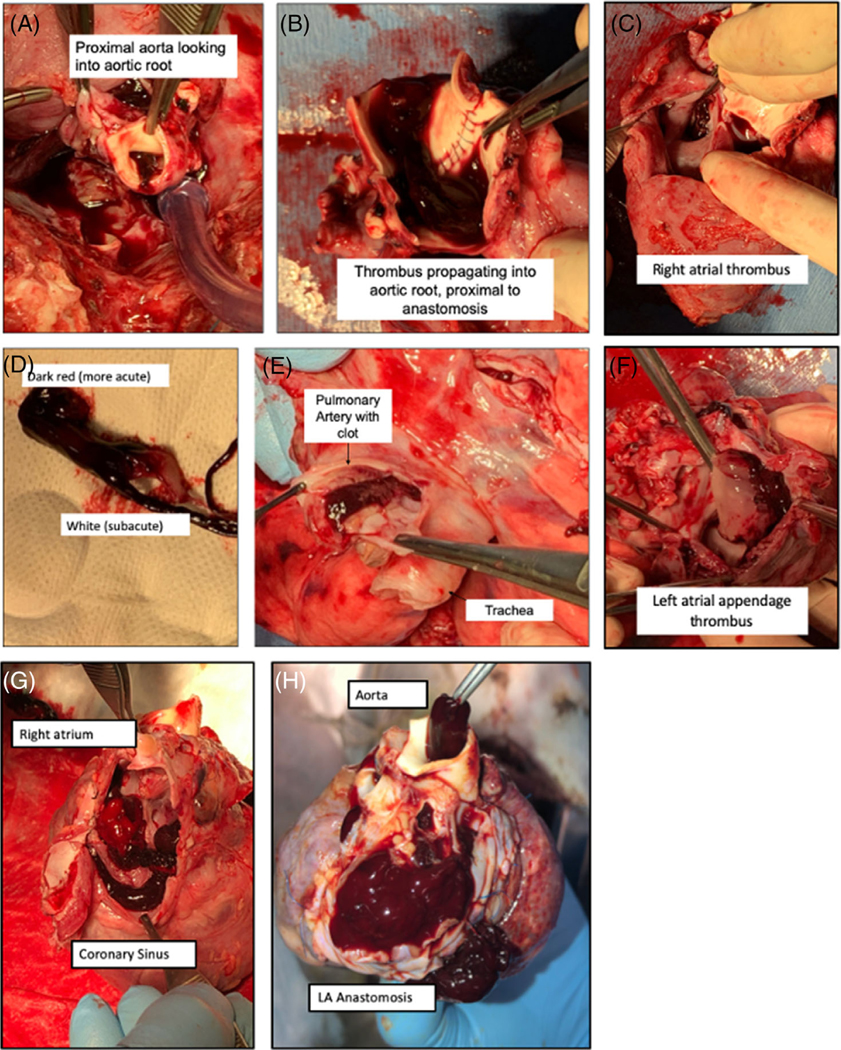

In Group 1 xenografts, with survival passed 48 h (and thus surpassed PCXD), endocarditis, monocyte and neutrophil infiltration, and fibrin thrombi were demonstrated (supplemental Figure 1). The presence of rejection versus an inflammatory process was difficult to interpret, but histologic and immunohistochemistry (IHC) examination indicating deposition of C4d, IgM, and IgG antibodies, along with non-gal antibody titer elevation in serum suggested AMR (B32628). Thrombotic complications were seen in 50% of xenografts without expression of thromboregulatory proteins (n = 4, Group 2). On gross postmortem examination, notable intracardiac thrombi were seen with propagation into the aorta, pulmonary arteries, and coronary sinus of some of these xenografts (Figure 6A). Histologic examination revealed intracardiac organizing thrombus, intravascular fibrin thrombi with regions of myocardial ischemia (Figure 6B).

FIGURE 6a. (A) Thrombotic complications in Group 2 (xenografts without thromboregulatory proteins).

panels (A–F), showing B33167’s xenograft at explantation. Consists of propagating thrombus of the aortic root (A, B, and D), left and right atrial thrombus (C and F) and pulmonary artery (E). Pulmonary artery and left atrium appear to have acute and subacute components. Intracardiac thrombosis of B33156 within coronary sinus (G), aorta, and pulmonary vasculature (H).

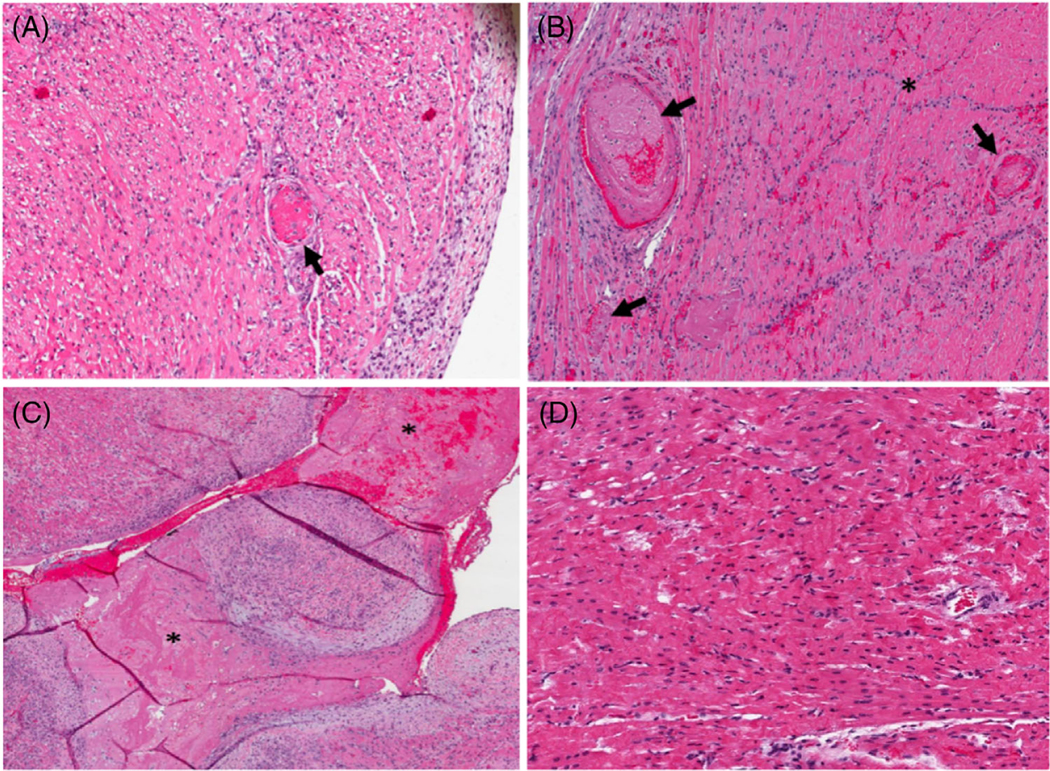

FIGURE 6b. (B) Histologic findings on Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) in Group 2 (xenografts without thromboregulatory proteins).

(A) B33167 right ventricle, 10× magnification. Fibrin thrombus (arrow) in a background of ischemic myocytes. (B) B33156 apex, 10× magnification. Fibrin thrombi (arrows) and a region of ischemic myocytes (asterisk). (C) B33156 left ventricle, 10× magnification. Note the intracardiac organizing thrombus (asterisk). (D) B33060 right ventricle, 10×, note contraction bands and hypereosinophilia, indicating an early necrotic process

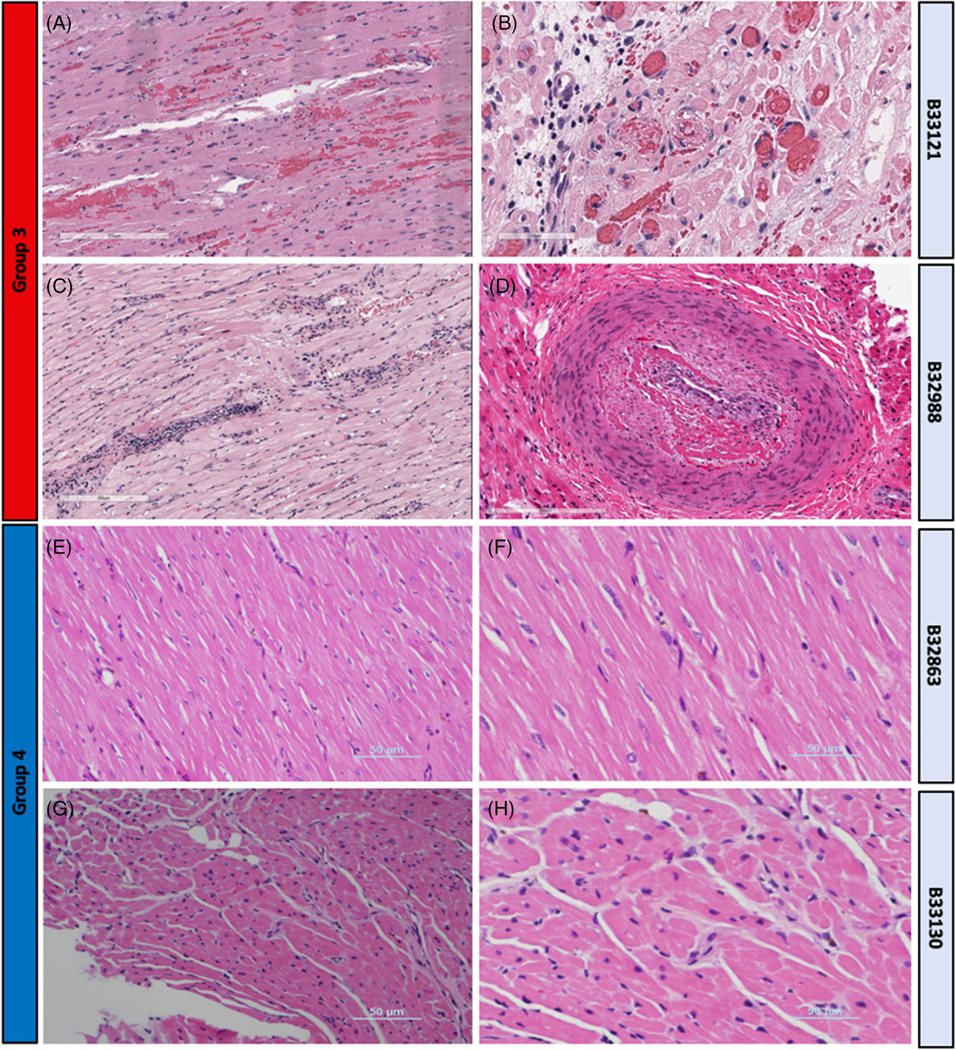

Group 3 xenografts showed the evidence of rejection within 3 months, with the progressive addition of human transgenes improving survival (Figure 4). Compared to grafts in Group 2, xenograft survival was significantly prolonged, but ultimately recipients were euthanized for symptoms developed in the presence of myocardial thickening. Gross examination of these explanted xenografts demonstrated ventricular wall thickening, as mentioned previously (Figure 5A). Space-filling inflammatory changes, edema, and fibrosis were present in those xenografts with wall thickening (Figure S2). There was no histologic evidence of frank hypertrophy, that is characterized by myocardial disarray, hypertrophy of myofibers, or irregular branching of cardiomyocytes. Although there was scattered evidence of anti-pig antibody deposition in other groups (Figure S4A,B), with less C4d staining with transgenes’ expression, evidence of AMR was dominant only in Group 3 xenografts. These findings include interstitial edema and interstitial hemorrhage, microvascular thrombosis, fibrosis, cellular infiltration, and endotheliitis (Figure 7A,B). The other Group 3 xenograft contained mild interstitial inflammation and chronic xenograft vasculopathy (CXV) (Figure 7C,D). Notably, however, a large acute septal infarct was present (Figure S2G).

FIGURE 7. H&E in long-term survivors between Groups 3 and 4.

(A) Group 3, B33121 LV (17X)- congestion, mild interstitial hemorrhage individual myofiber degeneration and necrosis. (B) Group 3, B33121 right ventricle (RV) (40X) veins with intravascular thrombosis. (C) Group 3, B32988 LV (14X) interstitial mononuclear lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, scant perivascular hemorrhage, myodegeneration. (D) Group 3, B32988 RV (20X) organized thrombus in muscular artery, consistent with chronic xenograft vasculopathy. (E) Group 4, B32863 RV (20X) normal myocardium without evidence of rejection. (F) Group 4, B32863 RV (20X) normal myocardium without evidence of rejection. (G) Group 4, B33130 RV (20X), endomyocardial biopsy on POD#220, normal myocardium without evidence of rejection. (H) Group 4, B33130 RV (40X), endomyocardial biopsy, normal myocardium without evidence of rejection

Group 4 xenografts consistently produced survival greater than 6 months, without evidence of growth, rejection, or inflammation. One (B32863) of the two recipients euthanized on POD# 182 demonstrated normal histology without the evidence of rejection or inflammation (Figure 7E,F). Endomyocardial biopsy was performed on the other long-term survivor (B33130) on POD# 220, and Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining also demonstrated normal histology (Figure 7G,H). Terminal histology of this xenograft on POD# 264 demonstrated some evidence of chronic vasculopathy of smaller vessels, which may have contributed to xenograft failure. A respiratory infection could not be ruled out, as four baboons in this recipient’s room died within a 1-week timeframe with respiratory symptoms. Group 4 xenografts demonstrate excellent biventricular function and minimal graft thickening, even in B33130 on POD# 260, just 4 days prior to explantation (Video 2).

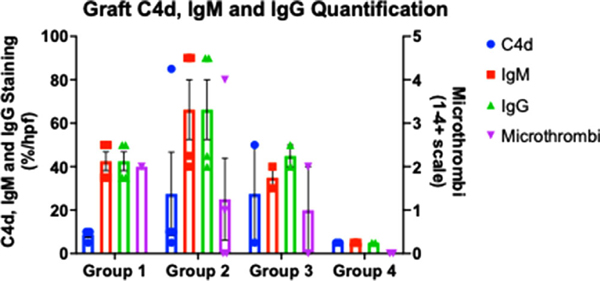

Quantification of C4d, IgM, IgG staining, and vascular microthrombi is summarized in Figure 8 and Figure S4A,B. Group 4 had the most favorable IHC staining, as demonstrated by minimal C4d, IgM, IgG, and microthrombi staining, followed by Group 1. C4d deposition was minimal in Groups 1 and 4, whereas IgM and IgG deposition was minimal only in Group 4. Xenografts containing CMAHKO (Groups 2 and 3) had the least favorable IHC staining with relatively high levels of both IgM, IgG staining, and C4d staining.

FIGURE 8. IHC quantification and microthrombi.

Presented as averages within each group. High power field was with 20x magnification, resulting in approximately an 870 micron field. Microthrombi were graded on a scale of 0–4+, where 1+≥ 0 capillaries stained; 2+≥ 1–5 capillaries stained; 3+≥ 5–10 capillaries stained, 4+≥ 10 capillaries stained, per high power field

2.5 |. Immunologic analysis in long-term versus short-term survivors

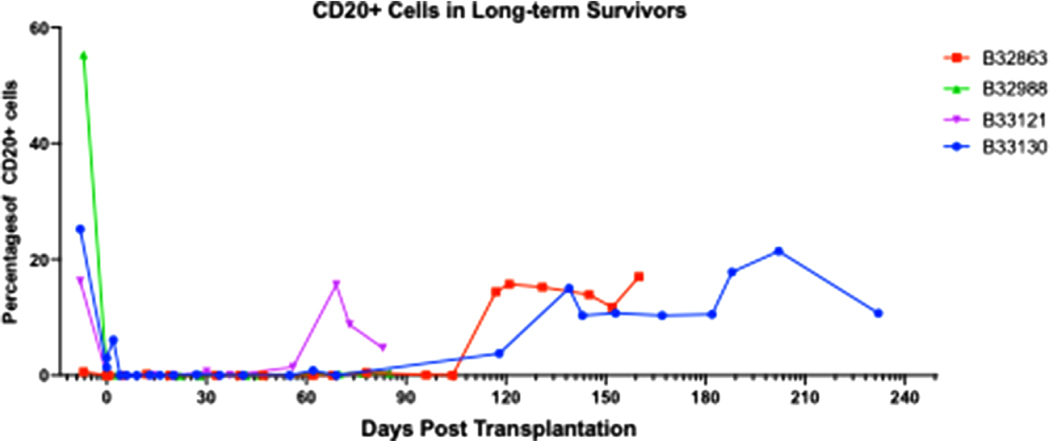

Immunophenotyping was performed on PBMCs from recipients longitudinally after transplantation. T and B-cell lymphocytes were depleted with anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) and Rituxan and confirmed by flow cytometry. CD3+ lymphocytes reconstituted within 48 h of transplantation. However, CD20+ lymphocyte depletion was for a prolonged period. In B33121, CD20+ lymphocytes re-emerged by 60 days; otherwise, all other long-term recipients reconstituted by 120 days, consistent with previous studies by our group (Figure 9).1,30

FIGURE 9. CD20+ cells in long-term survivors.

B-cell depletion is adequate after induction therapy, followed by reconstitution by 60–90 days after transplantation. Percent CD20+ cells calculated as a proportion of total CD3+ cells. Group 3 = B32988 and B33121; Group 4 = B32863 and B33130

Serum cytokine levels were measured after xenotransplantation in all the recipients receiving cardiac xenograft from all four groups. There were no observed differences in peripheral cytokine levels between short and long-term survivors or those with anti-inflammatory genes (Group 3, HO-1) (Figure S3). Additionally, circulating anti-pig non-gal IgG and IgM antibody levels did not rise significantly in any xenografts with early graft failure, even after AMR (Figure S5). There were no trends found between pretransplant non-gal IgG or IgM antibody levels and xenograft deposition postmortem.

2.6 |. Laboratory results demonstrate lasting protection from rejection in xenografts with multiple KOs and human complement, thrombosis, and inflammatory regulatory proteins

Complete blood count (CBC), CMP, coagulation parameters, and troponin I were collected at regular time intervals throughout the study (Figures S6–S9). Long-term survivors in Group 3 and 4 maintained normal kidney and liver function, whereas short-term survivors’ end-organ function was more variable (Figure S7).

Troponin levels peaked immediately after transplantation, consistent with ischemia/reperfusion insults on the xenograft followed by resolution down to 0.01–0.08 ng/ml out to 90 days, with a new baseline troponin between 0.10 and 0.94 ng/ml in those functioning past 3 months (i.e., Group 4) (Figure S8). Peak troponin after transplantation did not correlate with the incidence of PCXD or overall survival (R2 = 0.3446 and p = .1261). Most notably, troponin I correlated with rejection prior to xenograft dysfunction and resulted in troponin levels well over 1.0 ng/ml. Moreover, troponin was found to spike to levels well over baseline levels in the context of recipient stress, such as during central line-associated infections or examination under sedation and were unrelated to rejection episodes. After inciting events, troponin levels trended back to baseline.

Partial thromboplastin time (PTT), a measure of heparin anticoagulation levels, when targeting an activating clotting time (ACT) greater than twice baseline levels, was almost always >100 s. As seen in Figure S9, all long-term survivors achieved therapeutic anticoagulation to these levels but had periodic reductions in PTT. During these levels of relatively less anti-coagulation, troponin levels did not rise, and D-dimer, fibrinogen, and platelet levels remained normal.

3 |. DISCUSSION

Xenograft rejection is complex, and its mechanism appears much different from that of allografts. While allografts are predominantly rejected via cell-mediated mechanisms, xenografts are afflicted by a robust antibody-mediated process. Complex incompatibilities exist between donor pig and recipient nonhuman primates (and humans), which activates complement and induces dysregulation of coagulation.11 To date, AMR from preformed or induced antibodies to three carbohydrate antigens have been identified (Gal, SDa, and Neu5Gc).16,31,32 These factors have been addressed with immunosuppression, gene KO, and pigs expressing human transgenes developed in HHTx models of transplantation.1,33 As HHTx models were transitioned to OHTx, PCXD became a significant barrier but has now been mitigated with improved preservation of the donor organ. The longerterm survival, afforded by overcoming PCXD in OHTx, allows the investigation of various genetic modifications in life-supporting cardiac xenografts.

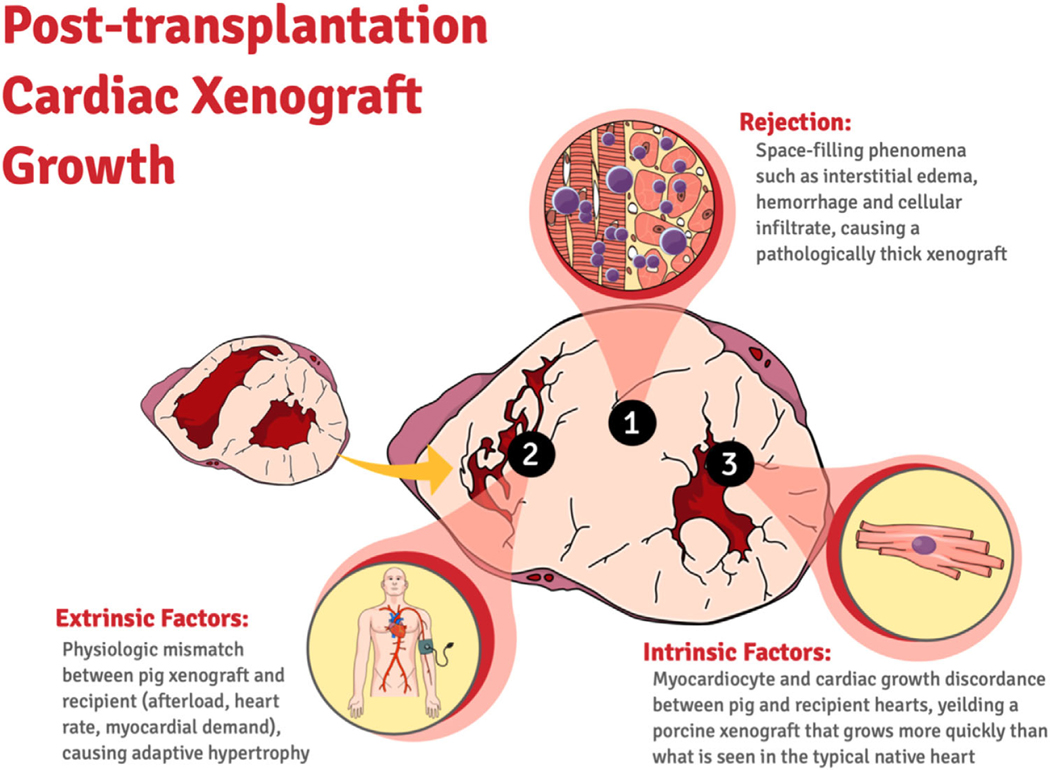

We have shown a stepwise increase, as permitted by the availability of GE pigs, in xenograft survival by addressing the main contributing factors of immunologic rejection with additional KOs and expression of human transgenes in pig donors. Select multi-gene xenografts demonstrate function for up to 264 days and exhibit minimal post-transplantation xenograft growth. Physiologic mismatch between pig xenograft and recipient baboon though present has not been shown to play a significant role in early graft failure. In our series, thickening was significantly delayed by additional transgene expression and KOs in Group 3 and was avoided in Group 4, and did not require afterload reduction, heart rate control, or Temsirolimus administration as previously suggested.34 The histological evidence presented in this study supports the idea that this growth, while multi-factorial, may have a rejection component that contributes significantly to ventricular wall thickness, xenograft dysfunction, and recipient demise. Temsirolimus has been used to mitigate “growth.” While an inhibitor of mTOR and intrinsic graft growth is also an immunosuppressive agent, and perhaps its role in suppressing graft growth is dependent on its anti-rejection effect. Indeed, in HHTx, we have not observed posttransplantation cardiac xenograft growth until rejection occurs from removing antiCD-40 mAb immunosuppression.1 In this study, intact GHR signaling in xenografts likely also contributes to posttransplantation growth in Group 3 (non-GHRKO xenografts) compared to Group 4 (GHRKO xenografts). A multi-factorial working model for posttransplantation xenograft growth is depicted in Figure 10. Much more work needs to be done on this topic to definitely conclude, which factors predominately contribute to posttransplantation xenograft growth and in which context.35 An ideal comparison would be between a GHRKO and GHR intact xenografts with otherwise the same genetics.

FIGURE 10. Potential mechanisms of posttransplantation cardiac growth in xenotransplantation.

Posttransplantation cardiac xenograft growth is likely caused by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, which includes rejection, intrinsic factors such as native xenograft growth. Other potential causes of growth include extrinsic factors such as physiologic mismatch leading to adaptive hypertrophy but were not observed in this study

Paradoxically, AMR continues to play a significant role in the nonhuman primate model with xenograft KO of Neu5Gc.16 We postulate that the immunologic and histopathologic results from Groups 2 and 3 are consistent with CMAHKO-related de novo neoantigen production, which may be driving AMR. This is also supported by demonstrating that CMAHKO has increased IgM binding compared to double KO xenografts (Figure 3C). As shown in Figure 2C, while heterozygous KO of CMAH is phenotypically null for Neu5Gc, these xenografts still have increased IgM binding compared to double KO xenografts (Figure 3C). However, this is purely a limitation of the NHP model, as humans already have a functional mutation of CMAH, which prevents B/T cell education of this antigen in humans and are tolerant to this potential neoantigen.36 Thus, xenografts with CMAHKO may not show accelerated rejection when transplanted in human recipients.37 While additional transgenes protected xenografts containing CMAHKO and delay graft failure, these constructs do not completely prevent it. The role of plasma cells cannot be ignored as the current immunosuppression used spares plasma cells. However, due to elimination of major antigens from the donor pigs, the strength of response to pig antigens is limited, but not eliminated.

As an alternative and complementary hypothesis to CMAHKO-related neoantigen production, we demonstrate a potential additive benefit of transgene expression. Specifically, hTBM, EPCR, hCD46, and hDAF. Survival was increased in xenografts that contained hTBM compared to grafts that did not. In xenografts that did not contain thromboregulatory proteins, thrombotic complications were present. This suggests that hTBM and other thromboregulatory proteins such as EPCR are equally important to xenograft protection and survival as immunomodulatory proteins. It is already known that there is an incompatibility between porcine-derived thrombomodulin from the endothelium to nonporcine circulating thrombin, and this contributes to the complex xenotransplantation rejection process. However, its role in preventing thrombosis in an OHTx has not been demonstrated yet. We also demonstrate a markedly reduced CDC with the addition of hCD46 expression with an additive benefit in combination with hDAF. This translated to a significant survival benefit when combined with xenografts containing coagulation regulatory proteins hTBM and hEPCR and anti-apoptotic protein hCD47 as seen in Groups 3 and 4, compared to Group 2.

Additionally, coronary vasculopathy was found in some xenografts of long-term survivors and possibly contributed to an acute myocardial infarction (MI) in one instance (B32988). The histology was somewhat similar to chronic allograft vasculopathy (CAV), which is characterized by diffuse and concentric intimal hyperplasia.38 It is known to be associated with intracoronary mural and occlusive thrombi and in some instances can lead to MI. CAV usually begins within the first year of transplant and is one of the leading causes of allograft failure.39 Its pathogenesis is poorly understood but likely has both immunologic and nonimmunologic causes.40–42 Randomized prospective studies have demonstrated that prophylactic treatment with statins reduces the rate of CAV and decreases mortality in heart transplantation patients.43 CXV, seen in some long term grafts, needs further evaluation, and possible role of antibody in its etiology needs to be explored.

One potential limitation to this study is the learning curve for the use of the XVIVO perfusion system. Our experiments were conducted sequentially, and initial grafts (Group 2) did not do well in spite of the XVIVO perfusion system. However, the team was trained by XVIVO and had XVIVO representatives present during the first several transplantations to ensure smooth operation of the platform. Groups 2–4 were treated identically in all regard but were only different in the number of KO and transgenes within the xenograft. This mitigates this potential confounder to the study’s conclusion that select “multi-gene” pig donor xenografts do far superiorly than those with less genes. As a case in point, Group 2 grafts were grouped together as grafts that uniformly lacked thromboregulatory proteins and many other transgenes from Groups 3 and 4. They did not survive long-term and showed increased deposition of complement on explanted xenografts. Antibody deposition was variable but increased in triple KO xenografts. Additionally, microscopic and macroscopic thrombotic phenomena occurred in two of the Group 2 recipients. Group 2 grafts containing hCD46 and hDAF, even in the absence of hTBM, did have a protective effect against graft complement deposition. However, overall survival was still limited. The survival outcomes and pathologic findings postmortem support an alternative interpretation that select multi-gene xenografts do better than others, and this is not simply a sequential experimentation, but perhaps a direct result of xenograft gene composition.

Another potential limitation to the study is the variation in genetics between groups. In terms of intergroup variation, the availability of genetically modified pigs is severely limited, and gene combinations also evolve based on the knowledge emerging in the field. This results in iterative changes in genetic engineering that may result in genotypes with several changes between groups. Evidence, albeit limited, in this series of animals receiving multi-gene cardiac xenografts, is the only study of its kind to date. However, despite a small samples size, it demonstrates a statistically significant difference in survival between groups (p = .0065). In terms of intragroup variability, there are six different set of genetics, but essentially only one set of genetics per group, except for Group 2. This group is grouped together as grafts that uniformly lacked thromboregulatory proteins, which, as stated above, uniformly did poorly and had a high incidence of thrombotic complications. Therefore, while somewhat heterogenous represents a group with similar clinical outcomes and insight into these particular genetic backbones in aggregate. We and some other leading groups in the field have an opinion that for clinical translation and to get to a stage where we can rely on immunosuppressive regimen similar to what is used clinically for allotransplantation, we need to manipulate the genetics of the donor pigs and make them less immunogenic. This was the reason we used pigs with extensive genetic modifications, and our results clearly indicate the beneficial role of this maneuver. Moreover, we did not observe any side effects of additional genetic modifications.

Results from Group 4 shared in this report are the first evidence of rejection free xenograft survival that provides a clinically translatable combination of GE pigs and target-specific immunosuppression without the need for additional adjuncts. It additionally provides insight and alternative solutions to address previously reported abnormal cardiac growth after OHTx transplantation. Our current immunosuppression protocol, summarized in Table 2, is based largely on our previously published regimen. Only additions included two anti-inflammatory agents administered during the first 3 months posttransplantation (etanercept and tocilizumab) based on observations by us and others that these adjuncts may improve survival. However, peripheral cytokine analysis does not suggest any major differences in peripheral cytokine level between short- and long-term survivors and those with anti-inflammatory genes such as HO-1. Thus, the utility of these adjuncts has yet to be supported by data but continues to be used nonetheless. The CD-40 co-stimulation blockade mAb used here (2C10R4) is not U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved for clinical use, but several clinical trials are in progress to test humanized forms of anti-CD40/CD40L mAb in transplant and autoimmune diseases (clinicaltrial.gov identifiers: NCT04711226, NCT04322149, NCT03781414, NCT03663335, NCT03905525, and NCT03610516).

TABLE 2.

Immunosuppression regimen. 125-mg Solu-Medrol is given before Rituxan, ATG at 20 mg/kg. Solu-Medrol 20 mg/Kg/daily is given for 3 days at any concern for rejection. BID = twice daily; IV = intraveneous, TID = three times daily, SC = subcutaneous

| Induction | Agent | Dose | Timing | Route | Pretreatment | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD20 | 19 mg/kg | Day −7, 0, 7 | IV infusion | Solu-Medrol, Benadryl, H2 blocker | To deplete B-cells | |

| ATG | 5 mg/kg | Day −2, −1 | IV infusion | Solu-Medrol, Benadryl, H2 blocker | To reduce number of T-cells | |

| Anti-CD40 (clone 2C10R4) CVF or Berinert | 50 mg/kg | Day −1 and 0 Day −1, 0, and 1 |

Slow IV infusion | None None |

Co-stimulation blockade. Suppression of both B- and T-cell response. To inhibit complement activity | |

| 50–100 U/kg | ||||||

| Tocilizumab | 8 mg/Kg | Day 0 | IV | None | Anti-inflammatory | |

| Etanercept | 0.7 mg/Kg | Day 0 | SC | None | Anti-inflammatory | |

| Maintenance | ||||||

| Anti-CD40 (clone 2C10R4) | 50 mg/kg | Days 3, 5, 9, 14 then weekly | Slow IV infusion | None | Co-stimulation blockade. Suppression of both B- and T-cell response. | |

| MMF | 20 mg/kg/2 h | BID, daily | IV infusion | None | B and T cell suppression | |

| Tocilizumab | 8 mg/Kg | Weekly until day 90 | IV | None | Anti-Inflammatory | |

| Etanercept | 0.7 mg/Kg | Weekly until day 60 | SC | None | Anti-inflammatory | |

| Solu-Medrol | 2 mg/kg | BID tapered off in 7 weeks | IV | None | Suppress inflammation | |

| Aspirin | 40 mg | Daily | Oral | None | Prevent platelet aggregation | |

| Heparin | 50–1000 U/h | Continuous | IV infusion | None | Maintain ACT 2X normal and prevent inflammation | |

| Supportive | ||||||

| Ganciclovir | 5 mg/kg/day | Daily | IV infusion | None | For CMV prophylaxis | |

| Cefazolin | 250 mg | TID daily for 7 days and whenever needed | IV | None | Infection prophylaxis and treatment | |

| Epogen | 200 U/kg | Day −7 to 7 then weekly | IM or IV | None | To increase hematocrit |

Abbreviations: ACT, activating clotting time; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CVF, cobra venom factor; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

4 |. CONCLUSION

In this study, we demonstrate clear preclinical efficacy to selective cardiac xenografts with carbohydrate antigen KOs, GHR KO and multiple human coagulation, complement and inflammatory regulatory proteins concomitantly with our proven immunosuppression protocol without any untoward side effects. Our results also demonstrate that removing Neu5Gc via CMAHKO may have detrimental effects in NHP models but should not be considered as evidence to not use CMAHKO xenografts in human xenotransplantation. Multigene xenografts may immediately reduce certain patients’ morbidity and mortality as a bridge to allotransplantation, who would otherwise die waiting for a heart.

5 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

5.1 |. Animals

Specific pathogen free Papio anubis baboons (Southwest National Primate Center, San Antonio TX or MD Anderson Cancer Center, Bastrop TX) weighing 15–30 kg were screened to eliminate specific pathogens of interest and used as recipients. Weight-matched GE German Landrace pigs (Revivicor Inc., Blacksburg, VA) were used as xenograft donors consecutively when of appropriate size. Xenografts contained KO of up to three known carbohydrate antigens, Gal, SDa, and Neu5Gc and expression of multiple human genes, including CD46, thrombomodulin (TBM), EPCR, CD47, and HO-1. A subset of these GE pigs also had KO of GHR. Expression of transgenes was consistent and at high levels across all pigs by Western blot and immunohistochemistry quantification. A list of all the GE donor pig with different combination of multiple gene used in the study are shown in Table 1. Euthanasia was performed for recipients with deteriorating condition of either cardiac or noncardiac origin. Death was an endpoint in the event of unexpected rapid cardiac deterioration. All animals were used in compliance with guidelines provided by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

5.2 |. Genetic engineering

Cardiac xenografts were produced from GE swine generated by somatic cell nuclear transfer as previously described.26 Transgene vectors expressing one, two, four, or two plus four recombinant human proteins were transfected into cultured fetal porcine fetal fibroblasts (Figure S10). Pigs in Group 1 harbored a multicopy minigene expressing human CD46 and a multicopy vector expressing human thrombomodulin (TBM) driven by the endothelial-specific porcine TBM promoter.44 Pigs in Group 2 contained a bi-cistronic vector containing a single copy each of human CD46 and human DAF, linked by a viral 2A sequence and driven by a single CAG promoter to ensure ubiquitous expression.26 In addition to this bi-cistronic vector, Group 3 pigs harbored a tetra-cistronic vector in which TBM and EPCR were linked by a 2A sequence and driven by a single endothelial-specific promoter, plus human CD47 and HO1, linked by a 2A sequence and driven by CAG. Finally, Group 4 pigs contained a single tetra-cistron, similar to the Group 3 version except that the CAG-driven bi-cistron was designed to express human CD46 and CD47. The functional activity of each transgene was characterized in in vitro assays as previously reported. All vectors in Groups 1–4 were targeted to preselected landing pads in the genome, facilitated by crispr/Cas9 and homologydirected repair. The groups also contained various carbohydrate KOs as previously indicated. The dominant carbohydrate antigen galactose-α1,3-galactose (Gal) was knocked out by insertional mutagenesis of the Ggta1 gene that encodes α1,3 galactosyl transferase.28 Two additional xenoantigens, Neu5Gc and SDa, were knocked out by crispr/Cas9-induced insertion and/or deletion mutations (indels) in genes encoding the enzymes that catalyze their synthesis, namely CMAH (cytidine monophosphate-N-neuraminic acid hydroxylase) and β4GalNT2 (β1,4-N-acetyl-galactosaminyltransferase), respectively. Lastly, GHR was knocked out with crispr/Cas9-induced indels to decrease the intrinsic growth of the heart.45,46

5.3 |. Immunosuppression

The immunosuppressive regimen for all recipient baboons included induction therapy and maintenance therapy, which is summarized in Table 2. Induction included anti-thymocyte globulin (Thymoglobulin; Genzyme, Cambridge, MA, USA; 5 mg/kg on days −2 and −1), anti-CD20 antibody (Rituxan; Genetech, San Francisco, CA, USA; 19 mg/kg on days, −7, 0, 7) for T and B cell suppression and anti-CD40 (clone 2C10R4)15 (NHP Reagent Resource, Worcester, MA, USA; 50 mg/kg on days −1, 0, 5, 9, 14 then per week) for blocking the CD40/CD154 co-stimulation pathway. Cobra venom factor (cobra venom factor (CVF); Quidel, San Diego, CA, USA; 50–100 Units; days −1, 0, and 1) or C1 Esterase Inhibitor (Berinert; CSL Behring, King of Prussia, PA, USA; 17.5un/kg; days −1, 0 and 1) was used to inhibit the complement activation. Maintenance immunotherapy included mycophenolate mofetil (MMF; Genzyme, Cambridge, MA, USA; 20 mg/kg bis in die (twice daily) (BID), daily) and anti-CD40 mAb (50 mg/kg) weekly. All recipient baboons received continuous heparin infusion to keep the activated clotting time (ACT) level twice the baseline. Ganciclovir (Roche, Nutley, NJ, USA; 5 mg/kg/day) was administered daily cytomegalovirus prophylaxis. Other medications included Epogen (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, California; 200 U/Kg) daily from day −7 to 7, and Cephazolin (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL, USA; 250 mg) daily for 7 days were given. If there was any sign of abnormal xenograft function, and there was clinical suspicion of rejection, rescue therapy was initiated with intravenous bolus dose of Solu-Medrol (20 mg/Kg for 3 days). Increased heparin dosage was also used to prevent thrombus formation, if needed and ACT was maintained twice the baseline. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor (Anti-TNFα) (Etanercept, Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA) and IL-6 inhibitors (Tocilizumab, Genentech, USA) was given for the first 3 months postoperatively.

5. |. Orthotopic transplantation

The surgical approach to cardiac xenotransplantation and perioperative care has been highlighted extensively elsewhere.47 Preoperative TTEs were conducted to ensure adequate cardiac function free of anatomic abnormalities deemed unsatisfactory for transplantation. Donor swine heart procurement was performed using 30cc/kg of blood cardioplegia with XVIVO heart solution (XHS) for induction preservation (XVIVO Perfusion, Gothenburg, Sweden). Cardiac preservation was performed using an XVIVO Perfusion system with XHS cardioplegia at 8°C, maintaining a perfusion pressure of 20 mmHg in the aortic root and physiological pH (7.2–7.6). In two experiments, prior to the availability of XVIVO technology, blood cardioplegia and storage preservation on ice were employed.

Life-supporting heart xenotransplantation was performed after placing the baboon recipient onto Aorto-bicaval CPB. Donor porcine xenografts were placed in the orthotopic position after native heart explantation, using a biatrial anastomosis technique.48

5.5 |. Postoperative care

A cardiac telemetry device (Data Sciences International [DSI] St. Paul, MN) was used to monitor hemodynamics, heart rhythm, and temperature postoperatively. Baboons were extubated after hemodynamic stability was achieved on minimal ionotropic support, and adequate cardiac function was demonstrated by transesophageal echocardiography. Drug administration, ionotropic support, and other supplemental drugs (if needed) were administered through a tunneled central line tethered through the recipient’s cage. Critical care nurses and physicians provided ICU level monitoring and management for the first 48–72 h postoperatively. As soon as deemed surgically appropriate, all baboons were placed on systemic heparin for an ACT goal of twice the baseline level. Recipient blood pressure and heart rate thresholds were not used to guide the use of any afterload reduction or chronotropic controlling agents.

5.6 |. Methods for evaluating xenograft function

Cardiac xenograft function was evaluated by telemetry (continuously; but weaned to intermittently every hour after 30 days) and TTE. The telemetry device (DSI, St. Paul, MN USA) was implanted into the recipient baboon’s chest as previously described to monitor the xenograft systolic and diastolic pressures, electrocardiogram, and the recipient’s temperature in our HHTx model.33,49 The telemetry device data were transmitted wirelessly to a receiver attached to the recipient’s cage and analyzed on Ponemah Software (DSI, St. Paul, MN USA). TTEs were obtained whenever the recipient was sedated, or as needed for clinical status change and need for evaluation.

5.7 |. Hematological and biochemical parameters of recipients

CBC, which includes white blood cell counts, hematocrit (HCT), red blood cells, hemoglobin, platelets, neutrophils, and monocytes were analyzed by hemoanalyzer (Abaxis Vetscan HM5C, ZOETIS, Parsippany, NJ) and histochemistry (Abaxis Vetscan VS2, ZOETIS, Parsippany, NJ), was performed weekly for the first 2 months and then biweekly until the xenograft was explanted. ACT and Troponin I levels were measured by iStat (Abbott Laboratories, Princeton, NJ, USA). IGF-1 levels were measured by Antech Diagnostics (Fountain Valley CA, USA).

5.8 |. Measurement of non-Gal IgG and IgM antibodies

Non-gal antibodies (IgG and IgM) titer was measured in heat inactivated baboon serum by flow cytometry using GTKO pAEC line (KO:15502).50 pAEC lines was from miniature swine, which was kindly provided by Dr. Hendrik-Jan Schuurman, formerly of Immerge Biotherapeutics. pAEC were isolated and cultured as previously described. Serum samples were collected from baboon before and after transplant every 2–3 days for month and biweekly thereafter. Flow cytometry was used to measure antibody binding (MFI) with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti human IgG (Cat # H10301) and IgM (Cat # H15101) antibodies (Invitrogen Corp, Waltham, MA, USA) to pAECs on a Cytek Aurora (Fremont, CA) Cytometer. The MFI of the cells was analyzed with Flowjo software (Flowjo LLC. Ashland, OR, USA) for each test serum and compared with that produced by the controls.

5.9 |. Cytotoxicity assay

Sera from recipient baboons was tested in a CDC assay utilizing pAEC with either donor or from the same genotype as donor (littermate). Heat inactivated baboon serum samples diluted to 25% in culture media were applied to confluent PAEC monolayers in 96 well plates for 30 min at 37°C. After incubation, serum dilutions were removed, and 7.5% rabbit complement (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) and IncuCyte Cytotox Red fluorophore reagent (Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany), diluted in culture media, were added to each well. Cells were imaged and counted every 10–15 m for 2 h using a BioTek Cytation 5 reader (Winooski, Vermont) with a CY5 (628/685) filter set and high contrast bright field optics. Percent cytotoxicity was calculated as the number of red fluorescent cells/total bright field cells counted x100. Three replicate wells per serum sample were counted, and the mean background cytotoxicity from two untreated wells (complement only, no serum) for each cell line was subtracted from final results.

5.10 |. FACS analysis for T and B cells phenotyping

Immuno-staining was performed on PBMCs with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies. Anti-human CD3 (Cat#556611& #552852), CD4 (Cat#560628), CD5 (566193), CD8 (Cat#563822), CD16 (Cat#561725), CD20 (Cat#641405), CD24 (Cat#561646), CD25 (Cat#561405), CD28 (Cat#560683), CD45 (Cat#563530), CD95 (Cat#561635), CD127 (Cat#562437), CD138 (Cat#562098), IgD (Cat#563313), and IgM (Cat#562618) mAbs from Pharmingen (BD Bioscience, San Francisco CA, USA) were used. Anti-human CD27 (Cat#302827) from Biolegend San Diego, CA, USA and anti CD19 (Cat#IM2470) from Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA were used. Anti-human CD21 (Cat#46–0219-42) and FoxP3 (Cat# 12–477742) were used from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific) Waltham, MA. Antibodies (3 or 4 microliter per million cells) were used as recommended or suggested by the manufacturers. Samples were run on Cytek Aurora (Fremont, CA, USA). Flow Cytometry analysis was performed using Flow Jo Software (Flowjo LLC. Ashland, OR, USA).

5.11 |. Histological evaluation of biopsies and explants of xenografts

Paraffin sections from multiple biopsies and sections of explanted xenografts were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for light microscopy. Sections were analyzed semi-quantitatively for the presence of hemorrhage, necrosis, thrombosis, and cellular infiltrates. Immunostaining for immunoglobulins (IgG (Cat# 760–2653), IgM (Cat# 760–2654) and complement (C3d (Cat#760–4522) and C4d (Cat# 760–4436) Roche Tissue Diagnostics) on paraffin section were performed. All the specimens were examined by an independent pathologist. Aperio Digital Pathology Slide Scanner was used with 20x magnification, resulting in a field approximately 870 microns field size. Fields were chosen that had the least amount of necrosis to prevent secondary deposition of IgG and then examined for capillary staining for IgG, IgM and C4d. Intensity was measured for C4d staining as 0: negative or equivocal staining 1+: faint positive staining 2+: strong positive staining in accordance with the Society of Cardiovascular Pathology, Association for European Cardiovascular Pathology, and the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation. Additionally, specimens were graded for microthrombi on a scale of 0–4+, where 1+≥ 0 capillaries stained; 2+≥ 1–5 capillaries stained; 3+≥ 5–10 capillaries stained, 4+≥ 10 capillaries stained, per high power field.

5.12 |. Endomyocardial biopsy

Venous vascular access was obtained percutaneously through the right femoral vein. A 7 Fr sheath was then advanced over a wire with a balloon-tipped catheter from the venous sheath into the right ventricle using X-ray guidance. A bioptome was then advanced through the sheath and using telemetry monitoring to detect premature ventricular contractions. The bioptome was then opened advanced, closed, and withdrawn to remove a tissue piece 1 mm cubed. For any given evaluation, 3–5 pieces are taken to be evaluated for pathological evidence of rejection. Venous closure was performed by manual pressure for 5–10 min.

5.13 |. Western blot of human transgene expression

hTBM, hEPCR, hCD46, hCD47, hHO-1, and hDAF-1 protein detection in liver tissue lysates were carried out on automated capillary western blotting system Simple WES (Protein simple, San Jose, CA, USA). Liver tissue lysates were obtained using TPER buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with protease inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total protein concentrations were quantified using BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Three micrograms of total protein was loaded into each well of 12–230 kDa WES separation module (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Anti-mouse detection module was used for mouse anti-human antibodies (hTBM, hEPCR, actin), and anti-rabbit detection was used for rabbit anti-human antibodies (hCD46,hDAF and hHO-1). Anti-sheep secondary antibodies were used for sheep anti-human CD47 antibody. All assays were run on manufacture’s recommended default program.

5.14 |. Immunohistochemical detection of human transgene expression

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Samples were sectioned at 4 μm, allowed to air-dry, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated through graded alcohols to water. Endogenous peroxidases were quenched using dual endogenous enzyme block (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) for 10 min. After washing with TBS-Tween buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), sections were blocked with serum free protein block (Agilent Technologies) for 5 min. Sections were gently drained, and 100 μl of antibody was dispensed onto each slide and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 30 min. After incubation slides were rinsed in wash buffer then incubated in 100 μl of EnVision+ Dual HRP secondary with 0.5% pig serum (Agilent Technologies) for 30 min. Slides were thoroughly rinsed in wash buffer. Antibody binding was then detected using 5-min incubation of 100 μl of diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB, Agilent Technologies). Slides were rinsed in running tap water, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated through graded alcohols and xylene, mounted on coverslips, and imaged. Positive staining was demonstrated by a deposition of brown pigment at the site of antibody binding.

5.15 |. Data analysis

All statistical analysis and graph tabulation were performed on GraphPad Prism 8 (San Diego, CA), including Kaplan–Meier curves and line graph plots.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding of this study is generously provided by public funding-NIAID/NIH U19 AI090959 “Genetically-engineered Pig Organ Transplantation into Non-Human Primates” and private funding by United Therapeutics

FUNDING INFORMATION

NIAID/NIH, Grant Number: U19 AI090959; United Therapeutics

Funding information

NIAID/NIH, Grant/Award Number: U19

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher’s website.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

David Ayares, Will Eyestone, Amy Dandro, Kasinath Kuravi, Lori Sorrels, and Todd Vaught are employed by Revivicor/United Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, et al. Chimeric 2C10R4 anti-CD40 antibody therapy is critical for long-term survival of GTKO.hCD46.hTBM pig-to-primate cardiac xenograft. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwase H, Ekser B, Satyananda V, et al. Pig-to-baboon heterotopic heart transplantation - exploratory preliminary experience with pigs transgenic for human thrombomodulin and comparison of three costimulation blockade-based regimens. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:211–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Längin M, Mayr T, Reichart B, et al. Consistent success in life-supporting porcine cardiac xenotransplantation. Nature. 2018;564:430–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah JA, Patel MS, Elias N, et al. Prolonged survival following pig-toprimate liver xenotransplantation utilizing exogenous coagulation factors and costimulation blockade. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg. 2017;17:2178–2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto T, Hara H, Foote J, et al. Life-supporting kidney xenotransplantation from genetically engineered pigs in baboons: a comparison of two immunosuppressive regimens. Transplantation. 2019;103:2090–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin J-S, Kim J-M, Min B-H, et al. Pre-clinical results in pigto-non-human primate islet xenotransplantation using anti-CD40 antibody (2C10R4)-based immunosuppression. Xenotransplantation. 2018;25:e12356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goerlich CE, Griffith B, Singh AK, et al. Blood cardioplegia induction, perfusion storage and graft dysfunction in cardiac xenotransplantation. Front Immunol. 2021;12:667093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dichiacchio L, Singh AK, Lewis B, et al. Early experience with preclinical peri-operative cardiac xenograft dysfunction in a single program. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;109:1357–1361. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.08.090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goerlich CE, Griffith B, Hanna P, et al. The growth of xenotransplanted hearts can be reduced with growth hormone receptor knockout pig donors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.07.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Rose AG, Cooper DK, Human PA, Reichenspurner H, Reichart B. Histopathology of hyperacute rejection of the heart: experimental and clinical observations in allografts and xenografts. J Heart Lung Transplant Off Publ Int Soc Heart Transplant. 1991;10:223–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohiuddin MM. Clinical xenotransplantation of organs: why aren’t we there yet? PLoS Med. 2007;4:e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuurman H-J, Cheng J, Lam T. Pathology of xenograft rejection: a commentary. Xenotransplantation. 2003;10:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuwaki K, Tseng Y-L, Dor FJMF, et al. Heart transplantation in baboons using alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pigs as donors: initial experience. Nat Med. 2005;11:29–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrne GW, Stalboerger PG, Du Z, Davis TR, Mcgregor CGA. Identification of new carbohydrate and membrane protein antigens in cardiac xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2011;91:287–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Good AH, Cooper DK, Malcolm AJ, et al. Identification of carbohydrate structures that bind human antiporcine antibodies: implications for discordant xenografting in humans. Transplant Proc. 1992;24:559562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estrada JL, Martens G, Li P, et al. Evaluation of human and non-human primate antibody binding to pig cells lacking GGTA1/CMAH/β4GalNT2 genes. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:194–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper DKC, Hara H, Iwase H, et al. Justification of specific genetic modifications in pigs for clinical organ xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2019;26:e12516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loveland BE, Milland J, Kyriakou P, et al. Characterization of a CD46 transgenic pig and protection of transgenic kidneys against hyperacute rejection in non-immunosuppressed baboons. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11:171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azimzadeh AM, Kelishadi SS, Ezzelarab MB, et al. Early graft failure of GalTKO pig organs in baboons is reduced by expression of a human complement pathway-regulatory protein. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roussel JC, Moran CJ, Salvaris EJ, Nandurkar HH, D’apice AJF, Cowan PJ. Pig thrombomodulin binds human thrombin but is a poor cofactor for activation of human protein C and TAFI. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:1101–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen B, Ramackers W, Tiede A, et al. Pigs transgenic for human thrombomodulin have elevated production of activated protein C. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:486–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh AK, Chan JL, Dichiacchio L, et al. Cardiac xenografts show reduced survival in the absence of transgenic human thrombomodulin expression in donor pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2019;26: e12465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ide K, Wang H, Tahara H, et al. Role for CD47-SIRP signaling in xenograft rejection by macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:5062–5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saraiva Camara NO, Parreira Soares M. Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), a protective gene that prevents chronic graft dysfunction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:426–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen B, Ramackers W, Lucas-Hahn A, et al. Transgenic expression of human heme oxygenase-1 in pigs confers resistance against xenograft rejection during ex vivo perfusion of porcine kidneys. Xenotransplantation. 2011;18:355–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eyestone W. Gene-edited pigs for xenotransplantation. In: Cooper DKC and Byrne G, eds. Clinical Xenotransplantation: Pathways and Progress in the Transplantation of Organs and Tissues Between Species. Springer International Publishing; 2020:121–140. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer K, Kraner-Scheiber S, Petersen B, et al. Efficient production of multi-modified pigs for xenotransplantation by ‘combineering’, gene stacking and gene editing. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai Y, Vaught TD, Boone J, et al. Targeted disruption of the alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene in cloned pigs. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinrichs A, Kessler B, Kurome M, et al. Growth hormone receptordeficient pigs resemble the pathophysiology of human Laron syndrome and reveal altered activation of signaling cascades in the liver. Mol Metab. 2018;11:113–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohiuddin MM, Corcoran PC, Singh AK, et al. B-cell depletion extends the survival of GTKO.hCD46Tg pig heart xenografts in baboons for up to 8 months. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg. 2012;12:763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ladowski J, Martens G, Estrada J, Tector M, Tector J. The desirable donor pig to eliminate all xenoreactive antigens. Xenotransplantation. 2019;26:e12504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutz AJ, Li P, Estrada JL, et al. Double knockout pigs deficient in N-glycolylneuraminic acid and galactose α−1,3-galactose reduce the humoral barrier to xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goerlich CE, DiChiacchio L, Zhang T, et al. Heterotopic porcine cardiac xenotransplantation in the intra-abdominal position in a non-human primate model. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):10709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Längin M, Konrad M, Reichart B, et al. Hemodynamic evaluation of anesthetized baboons and piglets by transpulmonary thermodilution: normal values and interspecies differences with respect to xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2019;27:e12576. 10.1111/xen.12576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goerlich CE, Singh A, Treffalls JA, Griffith B, Ayares D, Mohiuddin MM. An intrinsic link to an extrinsic cause of cardiac xenograft growth after xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2022;29:e12724. 10.1111/xen.12724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamamoto T, Iwase H, Patel D, et al. Old World Monkeys are less than ideal transplantation models for testing pig organs lacking three carbohydrate antigens (Triple-Knockout). Sci Rep. 2020;10:9771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto T, Hara H, Ayares D, Cooper DKC. The problem of the “4th xenoantigen” after pig organ transplantation in non-human primates may be overcome by expression of human “protective” proteins. Xenotransplantation. 2020;28:e12658. 10.1111/xen.12658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka H, Swanson SJ, Sukhova G, Schoen FJ, Libby P. Early proliferation of medial smooth muscle cells in coronary arteries of rabbit cardiac allografts during immunosuppression with cyclosporine A. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:2062–2065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lund LH, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: thirty-first official adult heart transplant report—2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:996–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaczmarek I, Deutsch MA, Kauke T, et al. Donor-specific HLA alloantibodies: long-term impact on cardiac allograft vasculopathy and mortality after heart transplant. Exp Clin Transplant Off J Middle East Soc Organ Transplant. 2008;6:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gullestad L, Simonsen S, Ueland T, et al. Possible role of proinflammatory cytokines in heart allograft coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:999–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis SF, Yeung AC, Meredith IT, et al. Early endothelial dysfunction predicts the development of transplant coronary artery disease at 1 year posttransplant. Circulation. 1996;93:457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wenke K, Meiser B, Thiery J, et al. Simvastatin initiated early after heart transplantation: 8-year prospective experience. Circulation. 2003;107:93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wuensch A, Baehr A, Bongoni AK, et al. Regulatory sequences of the porcine THBD gene facilitate endothelial-specific expression of bioactive human thrombomodulin in single- and multitransgenic pigs. Transplantation. 2014;97:138–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hinrichs A, Riedel EO, Klymiuk N, et al. Growth hormone receptor knockout to reduce the size of donor pigs for preclinical xenotransplantation studies. Xenotransplantation. 2020;28:e12664. 10.1111/xen.12664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwase H, Ball S, Adams K, Eyestone W, Walters A, Cooper DKC. Growth hormone receptor knockout: relevance to xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2020;28:e12664. 10.1111/xen.12652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goerlich CE, Griffith BP, Treffalls J, et al. A standardized approach to orthotopic (life-supporting) porcine cardiac xenotransplantation in a non-human primate model. Research Square. 2021. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1138842/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Shumway NE, Lower RR, Stofer RC. Transplantation of the heart. Adv Surg. 1966;2:265–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horvath KA, Corcoran PC, Singh AK, et al. Left ventricular pressure measurement by telemetry is an effective means to evaluate transplanted heart function in experimental heterotopic cardiac xenotransplantation. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:2152–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Azimzadeh AM, Byrne GW, Ezzelarab M, et al. Development of a consensus protocol to quantify primate anti-non-Gal xenoreactive antibodies using pig aortic endothelial cells. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:555–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.