Abstract

Background

Cellulitis is a clinical diagnosis with several mimics and no gold standard diagnostic criteria. Misdiagnosis is common. This review aims to quantify the proportion of cellulitis misdiagnosis in primary or unscheduled care settings based on a second clinical assessment and describe the proportion and types of alternative diagnoses.

Methods

Electronic searches of Medline, Embase and Cochrane library (including CENTRAL) using MeSH and other subject terms identified 887 randomised and non-randomised clinical trials, and cohort studies. Included articles assessed the proportion of cellulitis misdiagnosis in primary or unscheduled care settings through a second clinical assessment up to 14 days post initial diagnosis of uncomplicated cellulitis. Studies on infants and patients with (peri-)orbital, purulent and severe or complex cellulitis were excluded. Screening and data extraction was conducted independently in pairs. Risk of bias was assessed using a modified risk of bias tool from Hoy et al. Meta-analyses were undertaken where ≥ 3 studies reported the same outcome.

Results

Nine studies conducted in the USA, UK and Canada, including a total of 1600 participants, were eligible for inclusion. Six studies were conducted in the inpatient setting; three were in outpatient clinics. All nine included studies provided estimates of the proportion cellulitis misdiagnosis, with a range from 19 to 83%. The mean proportion misdiagnosed was 41% (95% CI 28 to 56% for random effects model). Heterogeneity between studies was very high both statistically (I2 96%, p-value for heterogeneity < 0.001) and clinically. Of the misdiagnoses, 54% were attributed to three conditions (stasis dermatitis, eczematous dermatitis and edema/lymphedema).

Discussion

The proportion of cellulitis misdiagnosis when reviewed within 14 days was substantial though highly variable, with the majority attributable to three diagnoses. This highlights the need for timely clinical reassessment and system initiatives to improve diagnostic accuracy of cellulitis and its most common mimics.

Trial Registration

Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/9zt72).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-023-08229-w.

KEY WORDS: cellulitis, erysipelas, pseudocellulitis, misdiagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Non-purulent cellulitis is a bacterial infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues characterised by pain, redness, edema and induration.1 It is typically caused by the pathogens Streptococcus pyogenes and increasingly Staphylococcus aureus.2,3 Commonly diagnosed in primary care and emergency department (ED) settings,4 it is costly and resource intensive. In the USA, there are an estimated 14.5 million cellulitis cases per year, 650,000 hospital admissions and an associated cost of approximately US$3.7 billion.5 In England, the inpatient cost of lower limb cellulitis for 2010 was approximately £96 million.4

Making the diagnosis of cellulitis is based on clinical assessment. Given the absence of pus with non-purulent cellulitis, bacterial cultures are usually not feasible.6 A systematic review by Patel et al. identified that there are no gold standard diagnostic criteria for cellulitis.7 As such, patients may be diagnosed with cellulitis mimics or ‘pseudocellulitis’, which is an alternate diagnosis misdiagnosed as cellulitis due to having a similar clinical presentation. Several conditions can mimic cellulitis.8 This makes diagnosis challenging and studies have reported misdiagnosis rates between 28 and 33%.8–10 Challenges in accurately diagnosing cellulitis lead to increased costs and suboptimal resource utilisation. Misdiagnosis also contributes to the inappropriate clinical care by exposing patients who do not have an infectious cause for their symptoms to unnecessary antibiotics,11 increasing the likelihood of antibiotic resistance and iatrogenic complications.12

Although several studies have investigated the rate of cellulitis misdiagnosis, this has been conducted in variable settings using a range of definitions.8,13,14 Some studies have used routinely collected data such as a change in diagnosis during hospital stay without any clinical reassessment10,15, making the true rate of misdiagnosis difficult to interpret. Further insight into the proportion of cellulitis misdiagnosis and the alternative diagnoses that contribute to misdiagnosis may inform clinical assessment and management, policy, and guidelines. The aim of this systematic review was to quantify the proportion of cellulitis misdiagnosis based on a second clinical assessment (either in-person or telemedicine). In addition, we aimed to determine the types and proportion of alternative diagnoses initially misdiagnosed as cellulitis.

METHODS

Protocol and Registration

The protocol for this review was developed prospectively using the MethodsWizard (https://sr-accelerator.com/#/methods-wizard), and is available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/9zt72). The review is reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.16 Any deviations from the protocol are reported in the relevant methods section.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included studies evaluating patients of any gender or age, except studies of infants (< 12 months old) which were excluded. Included patients had to have a working diagnosis of cellulitis at any anatomical site except papers focused solely on (peri-)orbital cellulitis. We also excluded studies of patients focusing on purulent or complicated cellulitis (such as abscess at initial assessment, severe sepsis or necrotizing soft tissue infections). To avoid selection bias, studies were excluded if they included only inpatients not responding to antibiotics, patients whose cellulitis trajectory was deemed to require specialist consultation/expertise and inpatients receiving intravenous antibiotics.

The initial diagnosis of cellulitis could be made by any clinician (e.g. general practitioner/family doctor, or other primary care or ED clinician), and the later (second) diagnosis could be made by either the same or another clinician (e.g. internist, infectious disease physician, dermatologist or skin specialist).

Studies were included when the primary location of presentation was a primary or unscheduled care setting, such as general practice, family medicine, ED, urgent care centre or aged care facility. If the setting of the study was unclear, the study was excluded.

We included randomised controlled trials of any design (e.g. parallel, factorial), non-randomised controlled clinical trials and cohort studies. We excluded all other types of primary studies and reviews of any type (systematic, narrative or scoping reviews).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with cellulitis misdiagnosis, as judged by a second clinical assessment at up to 14 days post-initial diagnosis (e.g. by a second diagnostician or by additional clinical information at follow-up including pathology results such as blood tests or swab culture, imaging such as ultrasound and clinical progression such as non-response to treatment). The secondary outcomes were alternative final diagnoses (type, number and timing), and the body site of misdiagnosed cellulitis (e.g. upper limb, lower limb, other body parts).

Search Strategy

The search was designed in PubMed by an information specialist, using a combination of MeSH and other subject terms, synonyms and search filters. The following automation tools were used in the design of the search: Word Frequency Analyser (to generate a preliminary set of search terms), SearchRefinery (to adjust the precision of the search) and the Polyglot Search Translator (to translate the search string from PubMed to the remaining databases). 17,18

The following databases were searched from inception until 21 June 2022: Medline (via PubMed), Embase (via Elsevier) and Cochrane Library including CENTRAL. Full search strategies are reproduced in Appendix 1.

No publication type or language restrictions were applied. We included studies whose results were available in full; we included conference abstracts if another public record with results was available (e.g. preprint, clinical trial registration with results). For studies published only as conference abstracts, we contacted the authors to obtain results and included the abstracts where this information was provided.

To supplement the database searches, we performed a forward (citing) and backwards (cited) citation analysis on 2 August 2022 using SpiderCite (https://sr-accelerator.com/#/spidercite).

Study Selection and Screening

Screening by title and abstract was conducted independently by four authors in pairs (RN, GK, KY, LH). Full texts of the included studies were obtained by one author (JC), and the full texts were independently screened by the same authors (in pairs) against the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies at both the title-abstract and full-text stages were resolved by consensus or by referring to a third author. The following Systematic Review Accelerator (https://sr-accelerator.com/) automation tools were used to assist the screening process: Deduplicator (to deduplicate the search results for screening), Screenatron (to conduct the screening) and Disputatron (to assist with identifying and resolving the disputes).

The screening process was recorded in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (see Fig. 1) and a list of studies excluded at the full-text screening stage is provided in Appendix 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Data Extraction

A standardised form (initially piloted on two included studies) was used for data extraction of characteristics of studies, the primary and secondary outcomes and assessment of risk of bias.

Two pairs of study authors (RN, GK, KY, LH), independently extracted the following data from included studies:

Study characteristics: authors, location, design, follow up duration, setting

Participants: N, gender, initial diagnosis, body site of initial diagnosis, clinician who made the initial diagnosis, clinician(s) who made the revised diagnosis, timepoint of the revised diagnosis

Outcomes: primary—proportion of misdiagnosis; secondary—differing final diagnosis (type, number, timing), site of misdiagnosis (e.g. limb, another body part)

Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved by consensus or by referring to a third author.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias of the included studies was independently assessed by two authors (PG, AS). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or by referring to a third author. Because the primary outcome is a prevalence question, the risk of bias was assessed using a modified risk of bias tool from Hoy et al.19 Each potential source of bias was rated as low or high, and the following domains were assessed:

Was the study population a close representation of the national population in relation to relevant variables?

Was the potential for incomplete outcome data minimised?

Was an acceptable (standardised) case definition used in the study?

Was the instrument to measure the parameter of interest valid and reliable?

Was the same mode of data collection used for all participants?

Data Analysis

We used individual participants as the unit of analysis; where reported otherwise by the study (e.g. mean value for the group), we extracted the data as it was reported.

For the primary outcome, we calculated the percentage of participants with misdiagnoses, and undertook meta-analyses only when meaningful (i.e. 3 or more studies reported on the same outcome). Meta-analysis was conducted using STATA 16; we used the I2 statistic to measure heterogeneity among the included trials and used a random effects model. We did not assess publication bias because fewer than 10 studies were included.

For the secondary outcomes, we calculated the frequencies of differing final diagnosis, their type and timing, as well as the site of misdiagnosis; those outcomes are tabulated and reported narratively.

Dealing with Missing Data

We contacted the study authors for missing or additional data.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

If data was sufficient, the following subgroup analyses were planned:

By body site of cellulitis: lower limb vs upper limb vs other

By setting of initial presentation: primary care vs emergency department

By patient status: admitted vs non-admitted patient

By history of previous cellulitis: Yes vs No

By clinician specialty for the second diagnosis

By in-person vs telemedicine assessment

The following sensitivity analyses were planned, if applicable:

Including vs excluding studies with 3 or more study domains rated at high risk of bias

By study design (RCT vs cohort studies).

RESULTS

The electronic database search, forward and backward citation analysis and a search of clinical trial registries yielded 887 studies to screen after deduplication. A total of 54 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and 45 studies were excluded (see Table S1 in Appendix 2). Nine studies (a total of 1600 patients) met the final inclusion criteria for both the qualitative and quantitative analysis (see Fig. 1). No studies were excluded due to the setting of assessment being unclear.

Included STUDIES

Of the nine included studies, six were conducted in the USA (Arakaki8, David9, Gupta20, Ko21, Li13, Raff22), two in the UK (Levell4, Mistry23) and one in Canada (Demir24). Three studies were randomised trials, and the remainder were observational studies (three prospective cohort, two retrospective cohort and one cross-sectional). Study sample sizes ranged from 29 to 635 patients. All studies included adults (age ≥ 18 years) with cellulitis; one study also included paediatric patients (David9). Six studies were conducted in the inpatient setting; three were in outpatient clinics. Two papers4,23 involved referral to a cellulitis clinic as part of their model of care for the management of outpatient cellulitis, rather than a consultation service for diagnostic uncertainty or severe/complex cellulitis (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| First author (country, year) | Study design | Setting | Study arms | Total patients | Age years (range*) |

Female sex (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Araraki et al (USA, 2014) |

RCT | Outpatient internal medicine clinic | 2 |

29 (20—intervention; 9—control) |

58 (N/A)—intervention 59 (N/A)—control |

17 (59) |

|

David et al (USA, 2011) |

Prospective cohort | Inpatient ward or observation unit | 1 | 145 |

45 years (SD 19) |

61 (42%) |

|

Demir et al (Canada, 2021) |

Cross sectional cohort | Inpatient | 1 | 52 |

64 years (IQR 52–76) |

24 (46%) |

|

Gupta et al (USA, 2019) |

RCT (pilot) | Inpatient | 3 |

45 (15 in each arm) |

57.9 years (SD 16.2) |

21 (47%) |

|

Ko et al (USA, 2018) |

RCT | Inpatient ward or observation unit | 2 |

170 (88—intervention; 82—control) |

58.8 years (SD 19.2) |

70 (40%) |

|

Levell et al (England, 2011) |

Retrospective cohort | Outpatient dermatology clinic | 1 | 635 |

66 years (range 18–99) |

317 (50%) |

|

Li et al (USA, 2018) |

Prospective cohort | Inpatient ward or observation unit | 1 | 116 |

58.4 years (SD 19.1) |

63 (54%) |

|

Mistry (England, 2019) |

Retrospective cohort | Outpatient dermatology clinic | 1 | 373 | Not reported | Not reported |

|

Raff (USA, 2021) |

Prospective cohort | Inpatient | 1 | 30 |

54 years (SD 18) |

12 (40%) |

RCT randomised controlled trial, SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range

*Expressed as either a mean with standard deviation or median with interquartile range

Risk of Bias

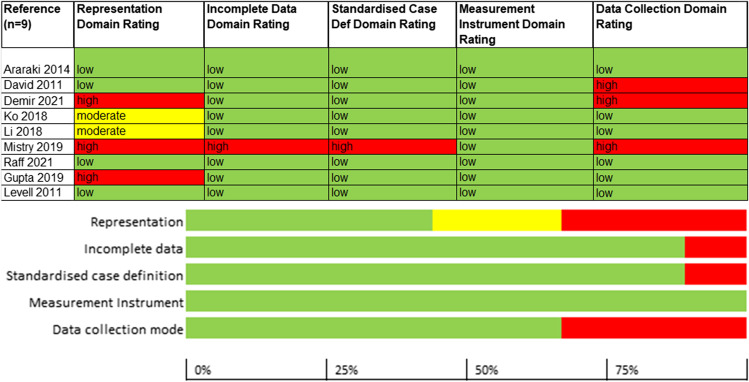

The risk of bias was assessed for five domains: representation, incomplete data, standardised case definition, measurement instrument and data collection mode.

For the representation domain, which evaluated whether the study population was a close representation of the population who get cellulitis, four out of nine studies were rated at low risk of bias. Two studies were rated at moderate risk of bias owing to potential for non-representationality, e.g. due to inclusion of selected cellulitis patient population in the study (e.g. just those admitted to the hospital), and three studies were rated at high risk of bias due to inclusion of only a subset of patients in the analysed data. Eight studies were rated at low risk of bias in the incomplete data domain. The single study23 rated at high risk of bias was so rated due to paucity of data reported for both the patients with and without cellulitis. A single study23 was rated high risk of bias in the standardised case definition domain, due to non-reporting of the characteristics of patients excluded from the study population; the remaining studies were rated at low risk of bias. All studies were rated at low risk of bias for the measurement of the parameter of interest (cellulitis identification). Finally, one-third of the studies were at high risk of bias for the data collection mode domain, due to lack of longer-term follow-up; the remaining studies were rated at low risk of bias (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias of the included studies.

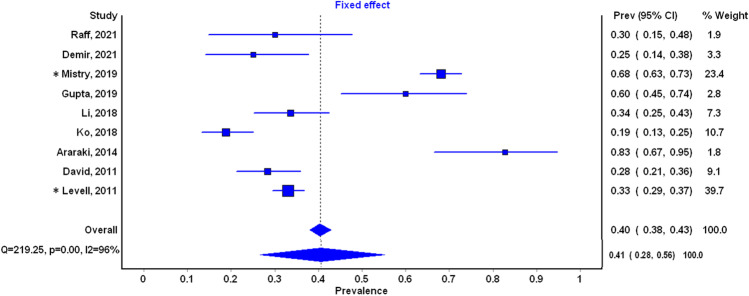

Primary Outcome: Proportion Misdiagnosed

All nine included studies provided estimates of the proportion misdiagnosed, with a range from 19 to 83% (see Fig. 3). On average, the proportion misdiagnosed was 41% (95% CI 28 to 56% for random effects model). Heterogeneity between studies was very high both statistically (I2 96%, p-value for heterogeneity < 0.001) and clinically (see Table 2).

Figure 3.

Cellulitis misdiagnosis proportion. Random effects diamond presented below the fixed effect diamond. *Retrospective studies.

Table 2.

Cellulitis Misdiagnoses: Initial and Final Assessors of the Diagnosis

| First author (Country, year) |

Initial assessor | Second assessor | Timing of second assessment | Cellulitis misdiagnosis (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Araraki (USA, 2014) |

Primary care physicians | Dermatologist | Same day | 24/29 (83%) |

|

David (USA, 2011) |

Emergency medicine physicians | Dermatologist or infectious diseases specialist | Within 24 h | 41/145 (28%) |

|

Demir (Canada, 2021) |

Predominantly emergency medicine physicians, plus outpatient and inpatient clinicians | Infectious diseases specialist | Unclear. Likely, within 24 h of commencing treatment for cellulitis | 13/52 (25%) |

|

Gupta (USA, 2019) |

Unclear | Dermatologist (30—teledermatology; 15—onsite dermatology) | Within 24 h (intervention) or at 14 days (control) | 27/45 (60%) |

|

Ko (USA, 2018) |

Emergency physicians | Dermatologist | Within 24 h | 32/170 (19%) |

|

Levell (England, 2011) |

Primary care physicians, emergency physicians, inpatient physicians, outpatient physicians | Dermatology nurse or dermatology junior doctor or dermatologist | Typically within 24 h. Less than 14 days | 210/635 (33%) |

|

Li (USA, 2018) |

Emergency physicians | Dermatologist | Within 24 h | 39/116 (34%) |

|

Mistry (England, 2019) |

Primary care physicians, emergency physicians, inpatient physicians | Dermatology nurse or dermatologist | Typically within 24 h. Less than 14 days | 254/373 (68%) |

|

Raff (USA, 2021) |

Emergency physicians | Dermatologist | Unclear. Likely less than 24 h, presumed to be less than 14 days | 9/30 (30%) |

Secondary Outcomes

We looked at two other outcomes:

Body site of cellulitis: Six out of nine studies reported on the site of cellulitis. The most common site was lower limb for both cellulitis (90.1%) and pseudocellulitis (93.2%.) The next most common site was upper limb with 5.7% for cellulitis and 2.3% for pseudocellulitis.

Type and frequencies of misdiagnoses: Of the misdiagnoses, 54% were attributed to three conditions (stasis dermatitis, eczematous dermatitis and edema/lymphedema), where the remaining 46% were attributed to over 30 conditions (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Types of Alternative Diagnoses Initially Misdiagnosed as Cellulitis (Ordered from Most to Least Frequent)

| Arakaki, 2014 N = 18 (%) |

David, 2011 N = 41 (%) | Demir, 2021 N = 13 (%) |

Gupta, 2019 N = 27 (%) |

Ko et al., 2018 N = 27 (%) | Levell, 2011 N = 210 (%) |

Li, 2018 N = 41 (%) |

Mistry, 2019 N = 254 (%) | Raff, 2021 N = 9 (%) |

Total N = 640 (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stasis dermatitis | 3 (16.6) | 15 (36.6) | 5 (38.5) | 5 (18.5) | 7 (25.9) | 9 (22.0) | 83 (32.6) Ϯ | 3 (33.3) | 130 (20.3) | |

| Eczematous dermatitis | 4 (22.2) | 3 (11.1) | 118 (56.2) Ϯ | 2 (22.2) | 127 (19.8) | |||||

| Edema/lymphedema | 2 (15.4) | 2 (7.4) | 14 (6.6) | 71 (28) | 89 (13.9) | |||||

| Lipodermatosclerosis | 1 (3.7) | 9 (4.3) | 10 (1.6) | |||||||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2 (4.9) | 8 (3.8) | 10 (1.6) | |||||||

| Contact dermatitis | 1 (5.6) | 2 (7.4) | 6 (14.6) | 9 (1.4) | ||||||

| Erythema migrans | 3 (16.6) | 5 (18.5) | 1 (11.1) | 9 (1.4) | ||||||

| Ulcers | 8 (3.8) | 8 (1.3) | ||||||||

| Nonspecific dermatitis | 2 (4.9) | 4 (9.8) | 6 (0.9) | |||||||

| Trauma related inflammation | 2 (4.9) | 4 (9.8) | 6 (0.9) | |||||||

| Gout | 1 (5.6) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (1) | 5 (0.8) | ||||||

| Erythema nodosum | 1 (5.6) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (7.4) | 4 (0.6) | ||||||

| Vasculitis | 1 (3.7) | 3 (1.4) | 4 (0.6) | |||||||

| Viral rash | 3 (7.3) | 3 (0.5) | ||||||||

| Deep wound infection | 3 (7.3) | 3 (0.5) | ||||||||

| Chronic wound | 3 (7.3) | 3 (0.5) | ||||||||

| Haematoma | 1 (5.6) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (0.5) | ||||||

| Psoriasis | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (0.3) | |||||||

| Thrombophlebitis | 2 (4.9) | 2 (0.3) | ||||||||

| Arthropod reaction | 2 (11.1) | 2 (0.3) | ||||||||

| Superficial wound | 2 (15.4) | 2 (0.3) | ||||||||

| Cryoglobulinemia | 1 (3.7) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (0.3) | |||||||

| Flexor tenosynovitis | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (0.3) | |||||||

| Vestibulitis | 1 (3.7) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (0.3) | |||||||

| Molluscum Contagiosum | 1 (5.6) | 1 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Impetigo | 1 (3.7) | 1 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Lymphangitis | 1 (3.7) | 1 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Abscess | 1 (3.7) | 1 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Paronychia | 1 (5.6) | 1 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Osteomyelitis | 1 (3.7) | 1 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Bursitis | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Myositis | 1 (3.7) | 1 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Calciphylaxis | 1 (3.7) | 1 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Alcoholic liver disease | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Other | 18 (43.9) | 4 (30.8) | 10 (37) | 46 (22) | 9 (22.0) | 100 (39.4) | 187 (29.2) |

*Li (2018) included patients with multiple diagnoses

ϮThis includes both eczematous dermatitis and stasis dermatitis

We also summarised several other study design features including setting, speciality and timing:

Setting of initial presentation: Four of nine studies initially diagnosed cellulitis in the ED. Three studies diagnosed cellulitis in varied locations including primary care, ED and inpatient and outpatient settings. Primary care practitioners alone provided the initial diagnosis in one study.

Clinician specialty for the initial diagnosis: Initial assessors were emergency physicians (4 studies), primary care physicians (1 study) or a combination of both (3 studies). In the remaining study, it was unclear who the initial assessor was. All initial assessments were done in-person.

Clinician specialty for the second diagnosis: Second diagnoses were provided by dermatology staff in seven studies. This could be a dermatologist, dermatology trainee or specialist nurse. One study had an infectious diseases specialist as second assessor. The remaining study had either a dermatologist or infectious disease specialist. One study utilised a dermatologist using teledermatology as second assessor.

Timing of second diagnosis: The timing of the second assessment was unclear in two studies, however strongly implied to be within 14 days of initial diagnosis. Four studies reported it within 24 h. Two reported it as ‘usually within 24 h’. The remaining study reported that it was done ‘the same day’.

Subgroup Analyses

There was insufficient data to conduct quantitative subgroup analyses for the planned subgroups.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed for different study designs (RCT vs cohort studies, and prospective vs retrospective studies). The proportion of misdiagnosis in the RCTs was 52% (95% CI 17–86 and 39% in cohort studies (95% CI 24–55)). The proportion of misdiagnosis in the prospective studies was 32% (95% CI 28–35) compared to 46% (95% CI 43–49%) in the retrospective studies.

DISCUSSION

Interpretation of Results

This systematic review identified nine studies involving patients diagnosed with cellulitis in primary or unscheduled care who had a second clinical assessment to confirm or refute the original diagnosis. The majority of second assessors were dermatologists and when recorded, the timing of the second assessment was within the first 24 h. The average proportion of cellulitis misdiagnosis was 41% and highly variable (range 19 to 83%). Most misdiagnoses (54%) were cases of stasis dermatitis, eczematous dermatitis and edema/lymphedema.

Prior Studies

Previous reviews have examined misdiagnosis rate, diagnostic criteria and time to response to treatment. Despite several differences in methods, our results are similar to Cutler et al.25 who found the prevalence of cellulitis misdiagnosis to be 39%. Their review excluded outpatients in their meta-analysis and included only dermatologists and infectious disease specialists to make the reference diagnosis. A systematic review by Patel et al. found that studies describing diagnostic tools for lower limb cellulitis had a high risk of bias in at least one domain and that the overall quality of data was low.7 Given that cellulitis remains a clinical diagnosis, our systematic review highlights the impact of a timely clinical reassessment to distinguish cellulitis from pseudocellulitis. A systematic review by Yadav et al. identified that the optimal time to assess response to treatment is between 48 and 96 h.11 This same timeframe could be utilised to also review accuracy of diagnosis.

Strengths and Limitations

There are several strengths to this review. We conducted a comprehensive electronic search across multiple databases followed by a forward and backward citation analysis and search of clinical trial registries. Studies included both inpatient and outpatient settings where the initial diagnosis was made by primary care and emergency clinicians who most commonly first encounter patients with potential cellulitis. Furthermore, patient inclusion was clinical and non-validated clinical decision tools were avoided. We minimised selection bias by excluding studies which only assessed more complex patients such as patients referred for specialist consultation, or inpatients not responding to antibiotics.

This systematic review also has several limitations. This review did not assess cases of cellulitis initially misdiagnosed as other conditions. In two studies, the timing of the second clinical assessment was unclear. If the time to second assessment was prolonged (e.g. several days), a different diagnostic assessment may have occurred where lack of response to antibiotics may strengthen the case for an alternative diagnosis. Alternatively, a delayed second review may fail to detect cellulitis misdiagnosis due to the natural course of the mimic being one of improvement, as there is no gold standard test for diagnosing cellulitis and it is possible that the second assessor misdiagnoses a pseudocellulitis variant. No included study involved a second assessment by the same clinician and there may be an inherent bias if a different assessor makes the second diagnosis. Despite our best efforts to minimise selection bias, the included studies did not necessarily include all consecutive patients with cellulitis and as such the overall misdiagnosis rate may have been overestimated. Additionally, we cannot state that no patients with (peri-)orbital cellulitis and abscess of sepsis were included, but based on the data presented and communications with authors inclusion of these cases would be rare and unlikely influence the overall results. We used the Hoy risk of bias tool19 that addresses prevalence rather than diagnostic accuracy. This tool does not address how patient selection, timing to second assessment and a lack of diagnostic standardisation could result in bias. These factors could result in both an under- and overestimate of misdiagnosis prevalence; however, we cannot comment on the overall size and direction of this bias. This meta-analysis identified significantly heterogenous results which could be explained by patient factors, disease factors, clinician factors and the timing and/or setting of the index and secondary clinical assessment. We are unable to comment on which factors contributed most; however, this heterogeneity likely contributes to variation in the prevalence of diagnosis at both initial and second assessment and provides further impetus to improve diagnostic criteria. Lastly, included studies were conducted in the US, UK and Canada with access to timely second review, which may affect generalizability.

Clinical Implications

The proportion of patients with cellulitis misdiagnosis is substantial though estimates are highly variable. This has implications for health systems, clinicians and patients. The included studies used specialist review, most within 24 h of initial diagnosis. All patients, especially those in whom the cellulitis diagnosis is not clearcut, ideally need a review for safety-netting within 48 to 96 h as highlighted in another systematic review.11 Failure to respond to antibiotics in this timeframe should prompt consideration of an alternative diagnosis. If there is ongoing diagnostic uncertainty at review, a specialist consultation (dermatology or infectious diseases) may be appropriate. To embed such an approach health care systems would need to consider rapid review clinics or similar systems, but access to such a service is not routinely available.

To improve diagnostic accuracy, the incorporation of clinical decision tools or pathways which provide prompts for consideration of pseudocellulitis diagnoses such as stasis and eczematous dermatitis and edema/lymphedema may be useful. Since over half of misdiagnoses in this study are attributable to these three conditions, targeted education on differentiation is warranted. Lastly, the substantial misdiagnosis rate highlights the need for shared decision-making. Patients should be routinely informed about the potential of misdiagnosis and given clear follow-up instructions. These initiatives would require a well-considered implementation strategy.

Research Implications

The James Lind Alliance Cellulitis Priority Setting Partnership is a multidisciplinary group established to identify the most important cellulitis research questions.26 Identifying the best diagnostic criteria for cellulitis was the second ranked cellulitis research priority. Future studies should assess the impact of educational interventions to improve diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, the potential benefit of telemedicine to diagnose cellulitis and track clinical response versus failure should be explored. Further studies assessing misdiagnosis would ideally be prospective and conducted in different health care settings. Such research would include all consecutive patients with an initial diagnosis of cellulitis with repeat assessments at set timepoints extending beyond 48 h by both the initial diagnostician and a second independent specialist. Such prospective research may further inform a more robust ‘gold standard’ definitions of cellulitis.

CONCLUSION

The proportion of patients with a cellulitis misdiagnosis when reviewed by a specialist within 24 h was high (41%) and highly variable (range 19 to 83%). Most misdiagnoses were cases of stasis dermatitis, eczematous dermatitis and edema/lymphedema. This highlights the need for timely clinical reassessment and system initiatives to improve diagnostic accuracy of cellulitis and its most common mimics.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

RN, KY, LH, PG and GK conceived the question; JC conducted the search; RN, LH, KY and GK screened the abstracts and full texts and collected the data. PG and AMS conducted the risk of bias assessments and conducted the statistical analysis. RN drafted the first version of the manuscript with all authors reviewing and approving. GK is the guarantor and accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish. The corresponding author RN attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding

LH was funded under Career Development Award (2020) from Health Research Council, New Zealand. Nil other to declare.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

The lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as registered have been explained.

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

Nil to declare.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Rachael Nightingale, Email: rachael.nightingale@health.qld.gov.au.

Krishan Yadav, Email: kyadav@toh.ca.

Laura Hamill, Email: drlaurahamill@gmail.com.

Paul Glasziou, Email: pglaszio@bond.edu.au.

Anna Mae Scott, Email: ascott@bond.edu.au.

Justin Clark, Email: jclark@bond.edu.au.

Gerben Keijzers, Email: gerben.keijzers@health.qld.gov.au.

References

- 1.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10–52. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaniotakis I, Gartzonika CG, Gaitanis G, Levidiotou-Stefanou S, Bassukas ID. Causality evaluation of bacterial species isolated from patients with community-acquired lower leg cellulitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(9):1583–1589. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Lower limb cellulitis and its mimics: Part II. Conditions that simulate lower limb cellulitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(2):177.e1–177.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levell NJ, Wingfield CG, Garioch JJ. Severe lower limb cellulitis is best diagnosed by dermatologists and managed with shared care between primary and secondary care. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(6):1326–1328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: A Review. JAMA. 2016;316(3):325–337. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chira S, Miller LG. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common identified cause of cellulitis: a systematic review. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(3):313–317. doi: 10.1017/s0950268809990483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel M, Lee SI, Akyea RK, et al. A systematic review showing the lack of diagnostic criteria and tools developed for lower-limb cellulitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(6):1156–1165. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arakaki RY, Strazzula L, Woo E, Kroshinsky D. The impact of dermatology consultation on diagnostic accuracy and antibiotic use among patients with suspected cellulitis seen at outpatient internal medicine offices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(10):1056–1061. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.David CV, Chira S, Eells SJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in patients admitted to hospitals with cellulitis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(3):1. doi: 10.5070/D39GN050RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weng QY, Raff AB, Cohen JM, et al. Costs and Consequences Associated With Misdiagnosed Lower Extremity Cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(2):141–146. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yadav K, Krzyzaniak N, Alexander C, et al. The impact of antibiotics on clinical response over time in uncomplicated cellulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s15010-022-01842-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: A multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of Early Dermatology Consultation for Inpatients Diagnosed With Cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):537–543. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georgesen C, Karim SA, Liu R, Moorhead A, Falo LD, Jr, English JC., 3rd Inpatient eDermatology (Teledermatology) Can Help Meet the Demand for Inpatient Skin Disease. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(7):872–878. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biglione B, Cucka B, Chand S, et al. Distinguishing clinical features for pseudocellulitis in pediatric inpatients: A retrospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39(4):570–573. doi: 10.1111/pde.15014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark J, Glasziou P, Del Mar C, Bannach-Brown A, Stehlik P, Scott AM. A full systematic review was completed in 2 weeks using automation tools: a case study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;121:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark JM, Sanders S, Carter M, et al. Improving the translation of search strategies using the Polyglot Search Translator: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Libr Assoc. 2020;108(2):195–207. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2020.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta P, Tolliver S, Zhang M, Schumacher E, Kaffenberger BH. Impact of dermatology and teledermatology consultations for patients admitted with cellulitis: A pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):513–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of Dermatology Consultation on Outcomes for Patients With Presumed Cellulitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):529–536. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raff AB, Ortega-Martinez A, Chand S, et al. Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy with Infrared Thermography for Accurate Prediction of Cellulitis. JID Innov. 2021;1(3):100032. doi: 10.1016/j.xjidi.2021.100032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mistry K, Sutherland M, Levell NJ. Lower limb cellulitis: low diagnostic accuracy and underdiagnosis of risk factors. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44(5):e193–e195. doi: 10.1111/ced.13930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demir KK, McDonald EG, de L'Étoile-Morel S, et al. Handheld infrared thermometer to evaluate cellulitis: the HI-TEC study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(12):1814–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cutler TS, Jannat-Khah DP, Kam B, Mages KC, Evans AT. Prevalence of misdiagnosis of cellulitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2022 doi: 10.1002/jhm.12977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas KS, Brindle R, Chalmers JR, et al. Identifying priority areas for research into the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of cellulitis (erysipelas): results of a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(2):541–543. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.