Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to report the clinical and functional outcomes, complication rates, implant survivorship and the progression of tibiofemoral osteoarthritis (OA), after new inlay or onlay patellofemoral arthroplasty (PFA), for isolated patellofemoral OA. Comparison of different implant types and models, where it was possible, also represented one of the objectives.

Methods

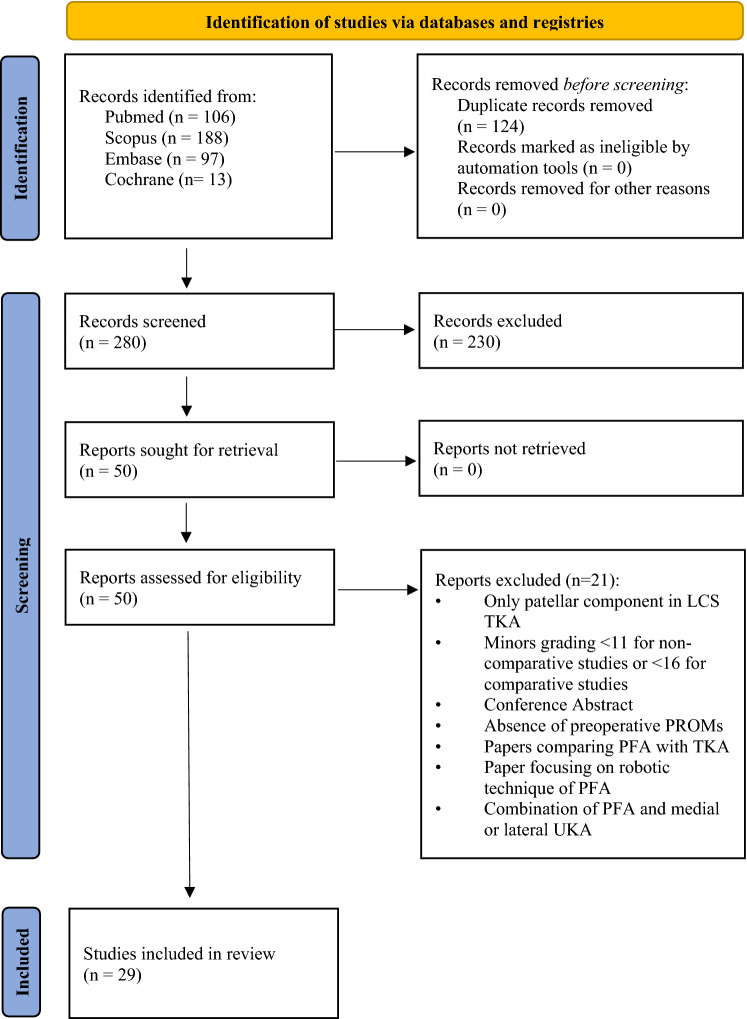

A systematic literature search following PRISMA guidelines was conducted on PubMed, Scopus, Embase and Cochrane databases, to identify possible relevant studies, published from the inception of these databases until 11.11.2022. Randomized control trials (RCTs), case series, case control studies and cohort studies, written in English or German, and published in peer-reviewed journals after 2010, were included. Not original studies, case reports, simulation studies, systematic reviews, or studies that included patients who underwent TKA or unicompartmental arthroplasty (UKA) of the medial or lateral compartment of the knee, were excluded. Additionally, only articles that assessed functional and/or clinical outcomes, patient-reported outcomes (PROMs), radiographic progression of OA, complication rates, implant survival rates, pain, as well as conversion to TKA rates in patients treated with PFA, using inlay or onlay trochlea designs, were included. For quality assessment, the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) for non-comparative and comparative clinical intervention studies was used.

Results

The literature search identified 404 articles. 29 of them met all the inclusion criteria following the selection process. Median MINORS for non-comparative studies value was 12.5 (range 11–14), and for comparative studies 20.1 (range 17–24). In terms of clinical and functional outcomes, no difference between onlay and inlay PFA has been described. Both designs yielded satisfactory results at short, medium and long-term follow-ups. Both designs improved pain postoperatively and no difference between them in terms of postoperative VAS has been noted, although the onlay groups presented a higher preoperative VAS. When comparing the inlay to onlay trochlea designs, the inlay group displayed a lower progression of OA rate.

Conclusion

There is no difference in functional or clinical outcomes after PFA between the new inlay and the onlay designs, with both presenting an improvement in most of the scores that were used. A higher rate of OA progression was observed in the onlay design group.

Level of evidence

III.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00167-023-07404-0.

Keywords: Patellofemoral arthroplasty, Patellofemoral replacement, PFA, PFR, Inlay, Onlay, Clinical outcomes, Functional outcomes, PROMs, Complications rate, Progression of OA, Progression of osteoarthritis, Pain, Implant survivorship, Systematic review

Introduction

Patellofemoral arthroplasty (PFA) for treatment of isolated patellofemoral osteoarthritis (OA) remains until today a controversial subject due to inconsistent results found throughout the existing literature [20, 26]. Patient selection, surgical technique, as well as implant choice have a direct effect on clinical outcomes. Historically, the first patellofemoral joint replacement was a vitallium cell patella cap designed by McKeever in 1955 [31]. Nowadays, PFA implant designs can be divided into two larger groups: inlay and onlay PFA.

First generation inlay designs, such as the Richard and Lubinus prosthesis, introduced back in 1979 [8], replaced only the worn cartilage, leaving the subchondral bone untouched. Short-term outcomes, were however not promising, with a low rate of patient satisfaction, but a high conversion rate to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [9, 45, 47]. The second-generation, or onlay design, was introduced in the 1990s. Contrary to the first-generation inlay designs, the onlay trochlea prosthesis completely replaced the anterior compartment of the knee, providing a possibility of correcting trochlea rotation or for dysplasia [46].

Due to potential complications of onlay designs, such as patellar catching or anterior notching, overstuffing, alongside an increased bone loss when compared to inlay designs, new generation inlay trochlea implants have been introduced [18, 21, 28, 34]. These implants aim to reproduce the complex kinematics of the patellofemoral joint with less mechanical and patellofemoral complications, increased implant stability and no alteration to the soft tissue tension or extensor mechanism [11, 13, 15, 16, 41].

Up-to-date studies, which report or compare clinical or functional outcomes, complication rates, revision or conversion rates, as well as progression of OA between different trochlea designs, are limited. Hence, the aim of this study is to report the clinical and functional outcomes, complication rates, implant survivorship and the progression of the tibiofemoral OA, after inlay or onlay PFA. Comparison of different implant types and models, where it is possible, also represents one of the objectives. The extended information provided from this systematic review will help physicians improve the patients’ management, functional, clinical outcomes and, therefore, patient satisfaction.

Materials and methods

A systematic literature search following PRISMA guidelines [37] was conducted on PubMed, Scopus, Embase and Cochrane databases to identify possible relevant studies, published from the inception of these databases until 11.11.2022. The study protocol has been registered and approved by Prospero (CRD42022330285). The search strategy can be found in Additional Material 9. Randomized control trials (RCTs), case series, case control studies and cohort studies, written in English or German, and published in peer-reviewed journals after 2010, were included in the title and abstract screening of this review. Not original studies, case reports, simulation studies, systematic reviews, or studies that included patients who underwent TKA or unicompartmental arthroplasty (UKA) of the medial or lateral compartment of the knee, were excluded. In a second step, full text analysis was performed by two authors. Articles that assessed functional and/or clinical outcomes, patient-reported outcomes (PROMs) (i.e. Knee Society Score [KSS], Oxford Knee Score [OKS], Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index [WOMAC], Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS], American Knee Society Score [AKSS], Visual Analog scale [VAS], Hungerford and Kenna Score [HKS], International Knee Documentation Committee Score [IKDC], International Knee Society Score [IKS], Anterior Knee Pain Score [AKP], etc.), radiographic progression of OA, complication rates, implant survival rates, pain, as well as conversion to TKA rates in patients treated with PFA, using inlay or onlay trochlea designs, were included. Additionally, only articles presenting their results in numerical data form were considered. Finally, surgical technique studies, abstract only studies, studies reporting outcomes after PFA with additional UKA, robotic PFA, or reporting outcomes of the patellar components of TKA, or comparing PFA with TKA, as well as studies which did not report preoperative data, have been also excluded. In case of discrepancy regarding eligibility criteria a third author was consulted.

Quality assessment

In order to assess the quality of the included studies, the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) for non-comparative and comparative clinical intervention studies was used [44]. The global ideal score for non-comparative studies was 16 and for comparative studies 24. The level of evidence of each included study war also reported. With the sole purpose of improving the systematic review’s quality, articles which did not meet a score of at least 11 for non-comparative studies or at least 16 for comparative studies according to MINORS have been excluded.

Data extraction

Title, author names, study design, year and journal of publication, abstract, level of evidence, follow-up time, design of the trochlea implant, clinical outcomes, functional outcomes, revision rates, complication rates, conversion to TKA rates, progression of OA, as well as reported pain levels and PROMs were extracted into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (MS Microsoft, USA).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described with means and standards deviations or medians and ranges. Categorical variables were reported with absolute and relative frequencies. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The literature search identified 404 publications in the initial screening process. Twenty-nine of them met all the inclusion criteria following the selection process. A detailed overview of the process is shown in Fig. 1. Median MINORS for non-comparative studies value was 12.5 (range 11–14), and for comparative studies 20.1 (range 17–24). Results from a total number of 1,761 patients were evaluated (median age at surgery 53 years, range 22–92 years). The reported median body mass index (BMI) was 26.4 (range 20–50.8). Several scores (OKS, KSS, KOOS, WOMAC, VAS, IKDC, AKP, HKS, IKS, Hospital for Special Surgery Patellofemoral Score [HSS-PF], University of California Los Angeles Score [UCLA], Short Form-36 Items [SF-36], Short Form-12 Items [SF-12], Melbourne Knee Score, Lysholm, Tegner, Kujala, Bartlett), alongside postoperative range of motion (ROM), implant survivorship, rate of complications, conversion to TKA and progression of OA, were used to evaluate clinical and functional outcomes. The detailed characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process according to the PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews [37]. LCS low contact stress, TKA total knee arthroplasty, PROMs patient-reported outcome measures, PFA patellofemoral arthroplasty, UKA unicondylar knee arthroplasty

Table 1.

Overview of reported patients

| Author (year) | Number of knees (patients) | Study type | Mean/median age, years (SD, range) |

Gender male (%) | Mean/median BMI (SD, range) | Mean/median follow-up time, months (SD, range) |

Level of evidence | MINORS Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beckmann [5] | 20 knees (20 patients) | Retrospective cohort | 46.4 (40–52) | nm | nm | 12 (8–44) | III | 17/24 |

| Bernard [7] | 153 knees (119 patients) | Retrospective cohort | 55.8 (nm) | 14% | 29.5 (nm) | 60 (± 31.2) | III | 23/24 |

| Feucht [16] | 30 knees (30 patients) | Retrospective cohort | 48.5 (± 8) | 73% | 27 (± 3) | 25.5 (± 10.5) | III | 24/24 |

| Feucht [17] | 41 knees (41 patients) | Retrospective cohort | 48 (± 13) | 39% | 26 (± 3.5) | 24 (nm) | III | 18/24 |

| Imhoff [22] | 35 knees (34 patients) | Prospective case series | 49 (± 14, 22–79) | 69% | 27 (± 3) | 65 (± 7, 60–90) | III | 14/16 |

| Imhoff [23] | 30 knees (28 patients) | Prospective cohort | 42 (± 13) | 52% | 28 (± 3) | 24 (nm) | II | 18/24 |

| Laursen [25] | 18 knees (18 patients) | Retrospective case series | 50 (± 12) | 33% | 28 (± 3.9) | 24 (nm) | IV | 11/16 |

| Patel [38] | 16 knees (16 patients) | Prospective case series | 63 (46–83) | 50% | 27.2 (22.5–30) | 24.1 (6–34) | III | 13/16 |

| Pogorzelski [40] | 62 knees (62 patients) | Prospective case series | 46 (± 11) | 42% | 27 (± 6) | 73 (± 25) | III | 14/16 |

| Zicaro [50] | 19 knees (15 patients) | Prospective case series | 54 (44–65) | 6% | nm | 35.2 (25–54) | III | 11/16 |

| Sarda [43] | 44 knees (40 patients) | Retrospective case series | 61.7 (43–84) | 23% | nm | 54 (36–96) | IV | 14/16 |

| Mofidi [33] | 34 knees (28 patients) | Retrospective case series | nm | 36% | nm | 12 (nm) | IV | 11/16 |

| Yadav [49] | 51 knees (49 patients) | Prospective case series | 54.4 (23–79) | 25% | nm | 50.4 (nm) | III | 13/16 |

| Beitzel [6] | 22 knees (22 patients) | Prospective cohort | 46.4 (± 9.3, 28–67) | 64% | 26.1 (± 2.6, 21.6 –30.8) | 24 (nm) | II | 22/24 |

| Davies [14] | 52 knees (44 patients) | Prospective case series | 60.7 (38–84) | 32% | nm | 42 (24–60) | III | 13/16 |

| Al-Hadithy [4] | 53 knees (41 patients) | Retrospective case series | 62.2 (39–86) | 24% | nm | 37 (12–70) | IV | 13/16 |

| Akhbari [3] |

61 knees (57 patients) |

Prospective case series | 66.1 (± 10.1) | 11% | nm | 61.1 (14–148) | III | 14/16 |

| Goh [19] | 51 knees (51 patients) | Retrospective case series | 52.7 (± 7.5, 39–72) | 14% | 28.7 (± 5.5, 20–43) | 49.2 (26.4–73.2) | IV | 13/16 |

| Willekens [48] | 35 knees (31 patients) | Retrospective case series | 53 (23–105) | 16% | nm | 55 (23–105) | IV | 12/16 |

| Ahearn [1] | 101 knees (83 patients) | Retrospective cohort | 60 (26–86) | nm | nm | 85 (60–105) | III | 11/16 |

| Konan [24] | 51 knees (47 patients) | Prospective case series | 57 (37–69) | 57% | 27.6 (22–34) | 85.2 (60–132) | III | 13/16 |

| Osarumwense [36] | 49 knees (36 patients) | Retrospective case series | 59 (39–80) | 36% | 30 (22–41) | 40 (24–58) | IV | 11/16 |

| Morris [35] | 45 knees (35 patients) | Retrospective case series | 55 (32–80) | 14% | 30.6 (18.8–50.8) | 31 (12–80) | IV | 13/16 |

| Dahm [12] | 61 knees (61 patients) | Retrospective case series | 56 (± 10.4) | 7% | 30 (± 4.9) | 48 (24–72) | IV | 13/16 |

| Ajnin [2] | 43 knees (32 patients) | Retrospective case series | 53 (42–62) | 22% | 34 (24–44) | 64 (30–119) | IV | 12/16 |

| Metcalfe [32] | 558 knees (429 patients) | Prospective case series | 58.8 (25–92) | 18% | nm | Minimum 24 (nm) | III | 11/16 |

| Bohu [10] | 74 knees (64 patients) | Retrospective case series | 59.6 (± 11.8, 31.3–82.1) | 19% | nm | 90 (± 85, 24–240) | IV | 11/16 |

| Rammohan [42] | 103 knees (79 patients) | Retrospective case series | 58 (42–78) | 32% | nm | 72 (24–132) | IV | 13/16 |

| Marullo [30] | 120 knees (97 patients) | Retrospective cohort | 66.5 (57–75) | 17% | nm | 73 (± 36) | IV | 19/24 |

BMI body mass index (kilogram/meter2), SD standard deviation, MINORS methodological index for non-randomized studies, nm not mentioned

In terms of OKS, 13 included studies, have reported improved postoperative scores, when compared to preoperative ones [1–4, 14, 19, 24, 32, 33, 36, 38, 42, 48]. No difference was observed between inlay and onlay implants, in terms of OKS [16]. Although, a couple of studies, which do not mention p values or confidence intervals do exist [14, 33], the overwhelming majority of the findings qualify as statistically significant (p < 0.05). Patients have been followed at short, short to medium, medium and long terms. Collected data can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of reported OKS

| Author (year) |

No. of knees | Implant type | Follow-up period (months) (SD, range) | Preoperative mean/median OKS (SD, range) | Postoperative mean/median OKS (SD, range) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mofidi [33] | 34 | FPV | 6 and 12 (nm) | 30 (± 6)* | 21 (± 12)* | nm |

| Davies [14] | 52 | FPV | 12 (nm) | 30.4 (16–44)* | 19 (3–41)* | nm |

| Al-Hadithy [4] | 53 | FPV | 12 (nm) | 19.7 (4–37)** | 32.1 (nm)** | < 0.05 |

| Akhbari [3] | 61 | Avon | 60 (nm) | 20.8 (± 7.9)** | 31.8 (± 8.7)** | < 0.001 |

| Goh [19] | 51 | Sigma HP | 24 (nm) | 32.2 (± 7.8)* | 22.3 (± 9.4)* | < 0.001 |

| Willekens [48] | 35 | Avon | 53 (23–105) | 10.5 (7–14)** | 32.1 (24.3–39)** | < 0.001 |

| Ahearn [1] | 101 | Journey | 60 (nm) | 18 (nm)** | 30 (21–42)** | < 0.001 |

| Konan [24] | 51 | Avon | 85 (60–132) | 18 (5–32)** | 38 (28–42)** | < 0.0005 |

| Osarumwense [36] | 49 | Gender Solutions | 40 (24–58) | 19 (5–32)** | 38 (28–42)** | < 0.0005 |

| Patel [38] | 16 | HemiCap Wave | 24.1 (6–34) | 19 (2–30)** | 35 (10–44)** | < 0.01 |

| Ajnin [2] | 43 | FPV | 65 (30–119) | 18 (5–35)** | 29 (19–45)** | 0.003 |

| Metcalfe [32] | 558 | Avon | 180 (nm) | 19 (14–25)** | 35 (20–41)** | 0.004 |

| Rammohan [42] | 103 | Journey | 60 (± 12, 24–108) | 18 (15–21)** | 37 (31–41)** | < 0.0001 |

OKS Oxford knee score, SD standard deviation, nm not mentioned, FPV Femoro-Patella Vialla, HP high performance, * Old OKS, ** New OKS

When discussing WOMAC, seven studies state that both inlay and onlay designs yield improved postoperative scores [1, 16, 17, 22, 23, 32, 40]. Feucht et al. also directly compared WOMAC scores, between onlay and inlay designs at a median follow-up of two years. There was no difference between the reported scores in the two groups [16]. WOMAC scores were reported at medium- and long-term follow-ups. All reported results are statistically significant (p < 0.05). Collected data can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Overview of reported WOMAC

| Author (year) |

No. of knees | Implant type | Follow-up period (months) (SD, range) |

Preoperative mean/median WOMAC (SD, range) |

Postoperative mean/median WOMAC (SD, range) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imhoff [23] | 30 | HemiCap Wave | 24 (nm) | 60.6 (± 17.9) | 85.2 (± 10.9) | < 0.001 |

| Ahearn [1] | 101 | Journey | 85 (60–105) | nm | 22 (15–35)* | < 0.001 |

| Feucht [16] | 30 (15 vs. 15) | Journey and HemiCap Wave | 25.5 (nm) |

63 (± 14) (HemiCap Wave) 51 (± 24) (Journey) |

78 (± 18) (HemiCap Wave) 78 (± 19) (Journey) |

< 0.05 |

| Metcalfe [32] | 558 | Avon | 180 (nm) | 62 (48–70)* | 35 (23–45)* | 0.013 |

| Imhoff [22] | 24 | HemiCap Wave | 60 (nm) | 63 (± 18, 58–71) | 74 (± 20, 68–84) | 0.011 |

| Feucht [17] | 41 | HemiCap Wave | 24 (nm) | 67.8 (± 13.6) | 79.0 (± 15.3) | < 0.05 |

| Pogorzelski [40] | 62 | HemiCap Wave | 60 (± 25) | 67 (± 16) | 77 (± 19) | 0.003 |

WOMAC Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index, SD standard deviation, nm not mentioned, FPV femoro-patella vialla, HP high performance, * Reverse WOMAC

In the case of ROM, 12 studies were identified for data extraction. The majority of the studies reported an increase in the postoperative ROM when compared to preoperative values [1, 12, 19, 24, 27, 35, 38, 43, 50]. Contrary to the majority, Al-Hadithy et al. reported no change in ROM, when comparing preoperative values to 12-months follow-up ones [4]. Furthermore, Ajnin et al. actually reported a decrease in ROM values at a median follow-up of 65 months (range: 30–119), when compared to preoperative values [2]. No studies were found which directly compared ROM values between onlay and inlay designs. ROM was reported preoperatively and postoperatively at short-, short-to-medium-, medium and long-term follow-ups. Collected data can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Overview of reported ROM

| Author (year) | No. of knees | Implant type | Follow-up period (months) (SD, range) | Preoperative mean/median ROM (SD, range) | Postoperative mean/median ROM (SD, range) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarda [43] | 44 | Avon | 54 (36–96) | 116º (100º-140º) | 125º (100º-140º) | < 0.05 |

| Mofidi [33] | 34 | FPV | 6 and 12 (nm) | nm | 116º (60º-130º) | nm |

| Al-Hadithy [4] | 53 | FPV | 12 (nm) | 120º (nm) | 120º (nm) | < 0.05 |

| Ahearn [1] | 101 | Journey | 85 (60–105) | 115º (105º-120º) | 120º (115º-120º) | n.s |

| Konan [24] | 51 | Avon | 85 (60–132) | 116º (98º-130º) | 121º (98º-129º) | nm |

| Liow [27] | 51 | Sigma HP | 24 (nm) | 126.6º (± 14.1º) | 129.2 (± 12.1º) | n.s |

| Morris [35] |

45 (26, 15,4) |

Vanguard, Gender Solutions and Kinematch |

27 (5–80) | 118.6º (90º-144º) | 121.8º (105º-144º) | nm |

| Dahm [12] | 59 | Avon | 48 (24–72) | 123º (± 9.0º) | 125º (± 6.1º) | n.s |

| Patel [38] | 16 | HemiCap Wave | 24.1 (6–34) | 115º (nm) | 120º (nm) | n.s |

| Ajnin [2] | 43 | FPV | 65 (30–119) | 115º (95º-130º) | 110º (90º-130º) | n.s |

| Marullo [30] | 120 | Gender Solutions | 84 (± 30, 24–142) | 110º (110º-120º) | 120º (nm, 120º-130º) | < 0.001 |

| Goh [19] | 51 | Sigma HP | 24 (nm) | 120.6º (± 14.1º) | 125.9º (± 12.1º) | n.s |

Regarding KSS, almost all of the nine analysed studies reported an increase in both postoperative clinical/objective scores and functional scores, when compared to preoperative ones [5, 7, 12, 19, 30, 35, 43, 50]. Both currently circulating variants of KSS were used (KSS 1989 and KSS 2011). With the notable exceptions of Morris et al. [35], who did not mention the statistical significance and Bernard et al. [7], who did present his findings as statistically non-significant, the remaining majority of analysed studies reported their findings as statistically significant (p < 0.05). The KSS scores were reported preoperatively and postoperatively at short to medium, medium and long-term follow-ups. Collected data can be found in Table 5.

Table 5.

Overview of reported KSS

| Author (year) |

No. of knees | Implant type | Follow-up period (months) (SD, range) |

Preoperative mean/median KSS (SD, range) | Postoperative mean/median KSS (SD, range) |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical*/ Objective** |

Functional | Clinical*/ Objective** |

Functional | |||||

| Sarda [43] | 44 | Avon | 54 (36–96) | nm | 57 (23–95)* | nm | 85 (28–100)* | < 0.05 |

| Goh [19] | 51 | Sigma HP | 24 (nm) | 58.5 (± 19.9)** | 65.9 (± 14.3)** | 89.8 (± 12.0)** | 82.8 (± 12.0)** | < 0.001 |

| Osarumwense [36] | 49 | Zimmer Gender Solutions | 40 (24–58) | nm | nm | 94 (89–100)** | 100 (10–100)** | < 0.0005 |

| Morris [35] | 45 (26,.15, 4) |

Vanguard, Gender Solutions and Kinematch |

27 (5–80) | 59.4 (35–90)* | 56 (29–95)* | 82.4(49–100)* | 62.8 (30–100)* | nm |

| Dahm [12] | 59 | Avon | 48 (24–72) | 51.4 (± 7.3, 37–88)** | 56.0 (± 10.9, 20–70)** | 89.9 (± 13.3, 57–100)** | 77.6 (± 20.6, 15–100)** | 0.0001 |

| Zicaro [50] | 17 | HemiCap Wave | 35.2 (± 13.2, 25–54) | 39.8(± 13.7)* | nm | 82.5(± 6.3)* | nm | < 0.0001 |

| Beckmann [5] | 20 | HemiCap Wave | 12 (nm) | 60 (± 5.3, 60–70)* a | nm | 90 (± 8.3, 70–90)* a | nm | 0.006 |

| Bernard [7] | 153 | Avon | 60 (± 30) | 58 (± 13.4)** a | 62.2 (± 23.5)** a | 76 (± 14.3)** a | 77.3 (± 23.5)** a | n.s |

| Marullo [30] | 120 | Gender Solutions | 84 (± 30, 24–142) | 57 (52–67)* | 60 (45–56)* | 94 (89–99)* | 90 (80–96) | < 0.001 |

KSS knee society score, SD standard deviation, nm not mentioned, ns not significant, FPV Femoro-Patella Vialla, HP high performance, * Old KSS (1989), ** New KSS (2011)

aValues from multiple groups combined into one overall group

In addition, various other PROMs were reported. AKSS was reported by three studies, at short and long-terms intervals [1, 25, 43]. They have found improved scores postoperatively when compared with preoperative ones. Tegner score was reported by five studies [7, 12, 23, 30, 40]. Furthermore, Kujala score [42, 48, 50], Lysholm score [16, 42, 50], KOOS [1, 12, 38], SF-12 and SF-36 [1, 19, 38] UCLA [12, 30], MKS [19, 43], HKS [3], IKS [10], IKDC [23], AKP [10] and HSS-PF [50] were also presented. A small difference in Lysholm score values between inlay and onlay designs has been reported at a median follow-up period of 25.5 months (range not given), with the inlay group scoring slightly higher (66 ± 11 vs. 57 ± 22) [16]. With the notable exception of Mofidi et al. [33] all other authors present their findings as statistically significant (p < 0.05). The collected scores were reported preoperatively and postoperatively at short to medium, medium and long-term follow-ups. Collected data can be found in Table 6.

Table 6.

Overview of reported PROMs

| Author (year) |

No. of knees | Implant type | Type of score | Follow-up period (months) (SD, range) | Preoperative mean/median value (SD, range) | Postoperative mean/median value (SD, range) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarda [43] | 44 | Avon | MKS | 54 (36–96) | 10 (5–21) | 25 (11–30) | < 0.05 |

| Mofidi [33] | 34 | FPV | AKSS total score | 6 and 12 (nm) | 49 (± 12) | 80 (± 20) | n.s |

| AKSS functional | 42 (± 12) | 65.5 (± 16) | n.s | ||||

| Akhbari [3] | 61 | Avon | HKS | 60 (nm) | 40 (25–55) | 80 (70–95) | < 0.001 |

| Goh [19] | 51 | Sigma HP | MKS | 24 (nm) | 12.6 (± 4.6) | 24.5 (± 5.8) | < 0.001 |

|

SF-36 PCS |

26.8 (± 4.7) | 45.4 (± 12) | 0.0001 | ||||

| SF-36 MCS | 45.9 (± 13) | 48.7 (± 15.6) | n.s | ||||

| Imhoff [23] | 30 | HemiCap Wave | Tegner | 24 (nm) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–5) | 0.005 |

| IKDC | 41.1 (± 12.9, nm) | 58.4 (± 14.9, nm) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Willekens [48] | 35 | Avon | KOOS | 53 (23–105) | 32.9 (25–42) | 57.6 (42.3–72.5) | < 0.001 |

| Kujala | 35 (27.5–44) | 55 (40.3–73.3) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Ahearn [1] | 101 | Journey | AKSS pain | 85 (60–105) | nm | 33 (20–50) | < 0.001 |

| AKSS functional | nm | 63 (45–85) | 0.002 | ||||

|

SF-12 PCS |

nm | 33.8 (31.2–36.4) | nm | ||||

|

SF-12 MCS |

nm | 45.3 (42.9–47.7) | nm | ||||

| Feucht [16] | 30 (15 vs. 15) | Journey and HemiCap Wave | Lysholm | 25.5 (nm) |

34 (± 11) (HemiCap Wave) 32 (± 20) (Journey) |

66 (± 11) (HemiCap Wave) 57 (± 22) (Journey) |

< 0.05 |

| Laursen [25] | 18 | HemiCap Wave |

AKSS clinical |

12 (nm) | 49.4 (± 4.5) | 85.3 (± 8.7) | < 0.01 |

|

AKSS functional |

50 (± 4.5) | 87.8 (± 7.7) | < 0.01 | ||||

| Dahm [12] | 59 | Avon | Tegner | 48 (24–72) | 2.3 (± 0.9, 0–4) | 3.8 (± 1.2, 0–5) | 0.0001 |

| UCLA | 3.4 (± 0.5, 2–5) | 5.8 (± 1.8, 2–9) | 0.0001 | ||||

| Patel [38] | 16 | HemiCap Wave | KOOS | 24.1 (6–34) | 39 (5–64) | 55 (33–85) | < 0.01 |

|

SF-36 PCS |

32 (19–40) | 53 (19–70) | < 0.01 | ||||

|

SF-36 MCS |

42 (18–55) | 45 (20–62) | n.s | ||||

| Zicaro [50] | 17 | HemiCap Wave | Lysholm | 35.2 (± 13.2, 25–54) | 31.9 (± 14.5) | 85.8 (± 9.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Kujala | 32.1 (± 17.5) | 79.3 (± 10.7) | < 0.0001 | ||||

| HSS-PF | 15.9 (± 15.4) | 90.6 (± 6.6) | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Ajnin [2] | 43 | FPV | Kujala | 65 (30–119) | 35 (15–74) | 58 (24–91) | 0.002 |

| Bohu [10] | 30 | Hermes | IKS | 240 (nm) | 36.3 (± 11.8) | 42.3 (± 22.1) | 0.03 |

| AKP | 47.2 (± 17.8) | 72.5 (± 14.6) | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Rammohan [42] | 103 | Journey | Lysholm | 60 (± 12, 24–108) | 27 (20–42) | 81 (60–89) | 0.0008 |

| Kujala | 33 (23.5–42.5) | 63.5 (44.3–78.5) | 0.0009 | ||||

| Modified Tegner | Level 2 | Level 3 | 0.023 | ||||

| Bartlett | 13 (9–14) | 25 (18–30) | 0.0002 | ||||

| Bernard [7] | 153 | Avon | Tegner | 60 (± 30) | 2 (± 1)a | 4 (± 1)a | n.s |

| Pogorzelski [40] | 62 | HemiCap Wave | Tegner | 60 (± 25) | 3 (± 2) | 4 (± 1) | < 0.001 |

| Marullo [30] | 120 | Gender Solutions | UCLA | 84 (± 30, 24–142) | 3 (2–4) | 5 (3–7) | < 0.001 |

| Tegner | 2 (1–2) | 3 (2–3) | < 0.001 |

PROMs patient reported outcome measures, SD standard deviation, nm not mentioned, n.s. not significant, MKS Melbourne knee score, AKSS American knee society score, HKS Hungerford and Kenna score, PROMs patient reported outcomes, SF-36 short form-36 items, SF-12 short form-12 items, PCS physical component score, MCS mental component score, IKDC international knee documentation committee score, KOOS knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score, UCLA University of California Los Angeles, HSS-PF hospital for special surgery patellofemoral score, IKS international knee society score, AKP anterior knee pain score

aValues from multiple groups combined into one overall group

Nine out of ten identified studies have reported a statistically significant reduction in perceived pain (p < 0.05) [5, 16, 22, 23, 25, 30, 40, 48, 50]. When comparing onlay designs with inlay ones, Feucht et al. showed that although both groups exhibited the same mean postoperative VAS value (4 ± 3), the mean preoperative VAS value was much higher in the onlay group (8 ± 2), when compared to the inlay group (6 ± 2) [16]. Scores have been reported preoperatively and postoperatively at short, short to medium, medium and long-term follow-ups. Collected data can be found in Table 7.

Table 7.

Overview of reported VAS

| Author (year) |

No. of knees | Implant type | Follow-up period (months) (SD, range) |

Preoperative mean/median VAS (SD, range) | Postoperative mean/median VAS (SD, range) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imhoff [23] | 30 | HemiCap Wave | 24 (nm) | 6.2 (± 2) | 3.1 (± 2.4) | < 0.001 |

| Willekens [48] | 35 | Avon | 53 (23–105) | 7.6 (6.7–8.5) | 4.1 (2.3–5.8) | < 0.001 |

| Konan [24] | 51 | Avon | 85 (60–132) | nm | 8 (7–9) | < 0.001 |

| Laursen [25] | 18 | HemiCap Wave | 12 (nm) | 7.5 (± 0.8) | 3.8 (± 1.3) | < 0.01 |

| Zicaro [50] | 17 | HemiCap Wave | 35.2 (± 13.2, 25–54) | 8 (± 0.9) | 2.5 (± 1.9) | 0.000 |

| Beckmann [5] | 20 | HemiCap Wave | 12 (nm) | 7 (± 0.8, 6–8) | 2 (± 0.8, 1–4) | < 0.001 |

| Imhoff [22] | 24 | HemiCap Wave | 60 (nm) | 6 (± 2, 5–7) | 3 (± 3, 2–4) | < 0.001 |

| Feucht [16] | 30 (15 vs. 15) | Journey and HemiCap Wave | 25.5 (nm) |

6 (± 2) (HemiCap Wave) 8 (± 2) (Journey) |

4 (± 3) (HemiCap Wave) 4 (± 3) (Journey) |

< 0.05 |

| Pogorzelski [40] | 62 | HemiCap Wave | 60 (± 25) | 6 (± 2) | 3 (± 2) | < 0.001 |

| Marullo [30] | 120 | Gender Solutions | 84 (± 30, 24–142) | 8 (7–9) | 2 (1–3) | < 0.001 |

VAS visual analog scale, SD standard deviation, nm not mentioned

In the case of reported complications, complication rates and implant survivorship, the present findings tend to exhibit a high degree of heterogeneity. In total, 19 studies were identified [1–3, 5, 7, 10, 19, 22, 24, 25, 30, 32, 36, 38, 40, 42, 43, 49, 50]. Complication rates varied greatly among analysed studies, from as low as 0.0% [25, 36] to as high as 35.3% [49] or even 41.2% [50]. The most commonly reported complication was patellar maltracking, followed closely by anterior knee pain [1–3, 5, 7, 10, 19, 22, 24, 30, 32, 38, 42, 43, 49, 50]. Reported revision rates also exhibited an elevated degree of heterogeneity between them, with some studies stating low revision rates of 3.8% [42] or 3.9% [24], and others reporting high revision rates such as 50.0% [22] or even 55.0% [5]. No studies directly compared the type and rate of complications, or the rate of revisions between onlay and inlay type of prostheses. Results were reported postoperatively at short-to-medium-, medium- and long-term follow-ups. Collected data can be found in Table 8.

Table 8.

Overview of reported complications and revision rate

| Author (year) |

No. of knees | Implant type | Follow-up period (months) (SD, range) |

Complication rate (%) |

Type of complication | Revision rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarda [43] | 44 | Avon | 54 (36–96) | 10 (20.5%) | Patellar maltracking; Anterior knee pain | 4 (9.1%) |

| Yadav [49] | 51 | LCS | 54.4 (23–79) | 18 (35.3%) | Patellar maltracking | 10 (19.6%) |

| Akhbari [3] | 61 | Avon | 120 (nm) | nm | Patellar maltracking | 4 (6.6%) |

| Goh [19] | 51 | Sigma HP | 49 (26–73) | nm | Patellar maltracking; Anterior knee pain | 4 (7.8%) |

| Ahearn [1] | 101 | Journey | 85 (60–105) | 7 (7.1%) | Patellar maltracking Anterior knee pain Superficial wound infection; Deep wound infection; Broken trochlear component | 12 (11.9%) |

| Konan [24] | 51 | Avon | 85 (60–132) | 1 (2.0%) | Anterior knee pain | 2 (3.9%) |

| Laursen [25] | 18 | HemiCap Wave | 72 (nm) | 0 (0.0%) | nm | 5 (27.8%) |

| Osarumwense [36] | 49 | Zimmer Gender Solutions | 40 (24–58) | 0 (0.0%) | nm | 2 (4.1%) |

| Patel [38] | 16 | HemiCap Wave | 24.1 (6–34) | 3 (18.8%) | Deep wound infection; Keloid scaring; Synovitis | 1 (6.3%) |

| Zicaro [37] | 17 | HemiCap Wave | 35.2 (±13.2, 25–54) | 7 (41.2%) | Anterior knee pain; Patellar maltracking; ITB syndrome Joint stiffness; Non-union of the TAT | 2 (11.8%) |

| Metcalfe [32] | 558 | Avon | 180 (nm) | nm | Anterior knee pain; Femoral loosening; Button wear; Patellar maltracking; Avascular necrosis of the femoral condyle | 105 (18.8%) |

| Ajnin [2] | 43 | FPV | 65 (30–119) | 11 (25.6%) | Anterior knee pain; Joint stiffness; Superficial knee infection | 6 (13.9%) |

| Beckmann [5] | 20 | HemiCap Wave | 29 (21–42) | nm | Anterior knee pain; Patellar malltracking | 11 (55.0%) |

| Bohu [10] | 30 | Hermes | 240 (nm) | nm | Patellar malltracking | 10 (33.3%) |

| Imhoff [22] | 24 | HemiCap Wave | 60 (nm) | 6 (25.0%) | Anterior knee pain; Synovitis; Component disassembly | 12 (50.0%) |

| Rammohan [42] | 103 | Journey | 60 (±12, 24–108) | 13 (12.6%) | Anterior knee pain; Patellar malltracking; Meniscal tear; Superficial knee infection; Haematoma; Patellar fracture | 4 (3.9%) |

| Bernard [7] | 153 | Avon | 60 (±30) | 5 (3.3%) | Deep wound infection; Synovitis; Patellar maltracking; Patellar fracture; Deep vein thrombosis | 10 (6.5%) |

| Pogorzelski [40] | 62 | HemiCap Wave | 60 (±25) | nm | nm | 14 (22.6%) |

| Marullo [30] | 120 | Gender Solutions | 84 (±30, 24–142) | nm | Patellar maltracking; Infection; Haemarthrosis | 9 (7.5%) |

In terms of progression of OA and conversion to TKA, an elevated variance in findings has been noted between the 23 analysed studies [1–4, 6, 7, 10, 12, 16, 19, 22–25, 30, 32, 36, 38, 40, 42, 43, 48, 49]. Reported rates of OA progression varied from as low as 0.0% [22, 23] and 3.9% [24, 49] at 24 and 60 months follow-up, up to 32.2% [12] and even 53.3% [16] at a median follow-up period of 48 months (range: 24–72 months) and 25.5 months (range not given) follow-ups. When comparing the rate of OA progression between inlay and onlay designs, Feucht et al. found a notable difference, with the reported rate of OA progression being 0.0% in the inlay group and 53.3% in the onlay group [16]. In the case of conversion to TKA, the reported rates of conversion vary from 0.0% [38] and 0.8% [30], at a reported median of 24.1 months (range: 6–34 months) and 84 months (range: 24–142 months) follow-ups, up to 27.8% [25] and 30.0% [10], at 6 and 20 years follow-ups. No difference in reported rates of conversion to TKA has been noted [16]. Results were analysed at short-, short-to-medium-, medium- and long-term follow-ups. Collected data can be found in Table 9.

Table 9.

Overview of reported progression of OA

| Author (year) |

No. of knees | Implant type | Follow-up period (months) (SD, range) |

Progression of OA (%) |

Conversion to TKA rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarda [43] | 44 | Avon | 54 (36–96) | 3 (6.8%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| Yadav [49] | 51 | LCS | 54.4 (23–79) | 2 (3.9%) | 5 (9.8%) |

| Beitzel [6] | 22 | Journey | 24 (nm) | nm | 1 (4.5%) |

| Al-Hadithy [4] | 53 | FPV | 12 (nm) | 6 (11.3%) | 2 (3.8%) |

| Akhbari [3] | 61 | Avon | 120 (nm) | 3 (4.9%) | 3 (4.9%) |

| Goh [29] | 51 | Sigma HP | 49 (26–73) | 2 (4.0%) | 2 (4.0%) |

| Imhoff [23] | 30 | HemiCap Wave | 24 (nm) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.3%) |

| Willekens [48] | 35 | Avon | 53 (23–105) | 10 (28.6%) | 3 (8.6%) |

| Ahearn [1] | 101 | Journey | 85 (60–105) | 8 (7.9%) | 8 (7.9%) |

| Konan [23] | 51 | Avon | 85 (60–132) | 2 (3.9%) | 2 (3.9%) |

| Feucht [16] | 30 (15 vs. 15) | Journey and HemiCap Wave | 25.5 (nm) |

Journey 8 (53.3%) HemiCap Wave 0 (0.0%) |

Journey 1 (6.7%) HemiCap Wave 1 (6.7%) |

| Laursen [25] | 18 | HemiCap Wave | 72 (nm) | 5 (27.8%) | 5 (27.8%) |

| Osarumwense [36] | 49 | Zimmer Gender Solutions | 40 (24–58) | 2 (4.1%) | 2 (4.1%) |

| Dahm [12] | 59 | Avon | 48 (24–72) | 19 (32.2%) | 2 (3.4%) |

| Patel [38] | 16 | HemiCap Wave | 24.1 (6–34) | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Metcalfe [32] | 558 | Avon | 180 (nm) | 61 (10.9%) | 61 (10.9%) |

| Ajnin [2] | 43 | FPV | 65 (30–119) | 5 (11.6%) | 6 (13.9%) |

| Bohu [10] | 30 | Hermes | 240 (nm) | 9 (30.0%) | 9 (30.0%) |

| Imhoff [22] | 24 | HemiCap Wave | 60 (nm) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (25.0%) |

| Rammohan [42] | 103 | Journey | 60 (± 12, 24–108) | 9 (8.7%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| Bernard [7] | 153 | Avon | 60 (± 30) | 9 (5.9%) | 9 (5.9%) |

| Pogorzelski [40] | 62 | HemiCap Wave | 60 (± 25) | 12 (19.4%) | 12 (19.4%) |

| Marullo [30] | 120 | Gender Solutions | 84 (± 30, 24–142) | 5 (4.2%) | 1 (0.8%) |

OA osteoarthritis, SD standard deviation, nm not mentioned, TKA total knee arthroplasty

Discussion

The main finding of the present review was that both onlay and inlay PFA yield satisfactory clinical and functional outcomes at short-, medium- and long-term follow-ups. No difference between designs has been described, although only one study from Feucht et al. [16] directly compared onlay and inlay designs using WOMAC and Lysholm scores, which presented a small and statistically non-significant difference in favour of the inlay design. Both designs improved pain postoperatively and no difference between them in terms of postoperative VAS has been noted, although the onlay group presented a higher preoperative VAS [16].

Regarding complication rates, implant survivorship and revision rates, the studies presented a high degree of heterogeneity between them. The most common complication described was the patella maltracking, followed closely by anterior knee pain.

One interesting finding of the study pertains to the progression of OA in the tibiofemoral compartment. When comparing the inlay and onlay trochlea designs Feucht et al. [16] found a statistically significant difference, in favour of the inlay group.

There are several systematic reviews in the literature, which report on PROMs and survivorship of the patellofemoral arthroplasty [29, 39, 46]. However, this is the first systematic review, which undertakes such a comprehensive analysis of postoperative outcomes. Additionally, none of them presents the results of both onlay designs and the new inlay designs. Pisanu et al. noted satisfactory results at short to mid-term follow-ups, and a 10 years survivorship of 90% with onlay designs, whereas inlay type of prosthesis showed disappointing results, with high rates of complications and failures [39]. This might be due the fact that included studies had reported results of first generation inlay designs only.

The systematic review of Lonner et al. based on the Australian National Joint Registry also described a 5-year cumulative revision rate of more than 20% in the case of inlay, and less than 10% when discussing onlay [29]. This is also because only first generation inlay designs were analysed. Progression of tibiofemoral OA after a successful PFA was found as the most common reason for failure [29].

This study has several limitations. First of all, the lack of more than one available studies in the literature, which directly compared the new inlay type of trochlea prosthesis, with the onlay design. Furthermore, no available RCTs pertaining to this subject have been found in the current literature. Another weakness is the retrospective type of the majority of the included studies, which could have led to an unknown selection bias. Another important aspect is that there are no studies reporting at mid- and long-term follow ups regarding the new inlay type of prosthesis, meaning that safe conclusions, with regards to the clinical and functional outcomes, and the survivorship of this type of prosthesis should be drawn with all due caution. Lastly, many authors were consultants for the companies designing the type of prostheses investigated in the respective studies, which might have led to a conflict of interest.

This systematic review provides physicians with valuable information to improve patient management, functional and clinical outcomes, and increase patient satisfaction.

Conclusion

There is no difference in functional or clinical outcomes after PFA between the new inlay and the onlay designs, with both presenting an improvement in most of the scores that were used. A higher rate of OA progression was observed in the onlay design group.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their thanks to Silvia Reichl, Iris Spörri and Felix Amsler, for offering their invaluable research knowledge as guidance, when conducting this systematic review.

Abbreviations

- AKP

Anterior knee pain score

- AKSS

American knee society score

- BMI

Body mass index

- HKS

Hungerford and Kenna score

- HSS-PF

Hospital for special surgery patellofemoral score

- IKDC

International knee documentation committee score

- IKS

International knee society score

- KOOS

Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score

- KSS

Knee society score

- MINORS

Methodological index for non-randomized studies

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- OKS

Oxford knee score

- PFA

Patellofemoral arthroplasty

- PF-CAT

Physical function-computerized adaptive test

- PROMs

Patient-reported outcomes measures

- RCT

Randomized control trial

- ROM

Range of motion

- SF-12

Short form-12 items

- SF-36

Short form-36 items

- TKA

Total knee arthroplasty

- UCLA

University of California Los Angeles score

- UKA

Unicondylar knee arthroplasty

- VAS

Visual analog scale

- WOMAC

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities arthritis index

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M-PS, GN, and MTH; Methodology: M-PS, GN; Data curation: M-PS, GN and AL; Writing—original draft preparation: M-PS and GN; Writing—review and editing: MTH, AL, GN and M-PS; Supervision: MTH; project administration: M-PS and GN. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Basel. This research received no external funding.

Data availability

Data is stored on personal storage and available on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Michael T. Hirschmann is a consultant for Medacta™, Symbios™ and Depuy Synthes™. The rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because unlike primary research, no new personal, sensitive or confidential information has been collected from participants. Only publicly available documents were used for the systematic review.

Informed consent

Due to the nature of the study, no “Informed Consent” was necessary.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Manuel-Paul Sava and Georgios Neopoulos have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Ahearn N, Metcalfe AJ, Hassaballa MA, Porteous AJ, Robinson JR, Murray JR, Newman JH. The journey patellofemoral joint arthroplasty: a minimum 5 year follow-up study. Knee. 2016;23(5):900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ajnin S, Buchanan D, Arbuthnot J, Fernandes R. Patellofemoral joint replacement - mean five year follow-up. Knee. 2018;25(6):1272–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhbari P, Malak T, Dawson-Bowling S, East D, Miles K, Butler-Manuel PA. The Avon patellofemoral joint replacement: mid-term prospective results from an independent centre. Clin Orthop Surg. 2015;7(2):171–176. doi: 10.4055/cios.2015.7.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Hadithy N, Patel R, Navadgi B, Deo S, Hollinghurst D, Satish V. Mid-term results of the FPV patellofemoral joint replacement. Knee. 2014;21(1):138–141. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckmann J, Merz C, Huth J, Rath B, Schnurr C, Thienpont E. Patella alta and patellar subluxation might lead to early failure with inlay patello-femoral joint arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(3):685–691. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-4965-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beitzel K, Schöttle PB, Cotic M, Dharmesh V, Imhoff AB. Prospective clinical and radiological two-year results after patellofemoral arthroplasty using an implant with an asymmetric trochlea design. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(2):332–339. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernard CD, Pareek A, Sabbag CM, Parkes CW, Krych AJ, Cummings NM, Dahm DL. Pre-operative patella alta does not affect midterm clinical outcomes and survivorship of patellofemoral arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(5):1670–1677. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06205-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blazina ME, Fox JM, Del Pizzo W, Broukhim B, Ivey FM. Patellofemoral replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;144:98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Board TN, Mahmood A, Ryan WG, Banks AJ. The Lubinus patellofemoral arthroplasty: a series of 17 cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(5):285–287. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0645-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohu Y, Klouche S, Sezer HB, Gerometta A, Lefevre N, Herman S. Hermes patellofemoral arthroplasty: annual revision rate and clinical results after two to 20 years of follow-up. Knee. 2019;26(2):484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2019.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannon A, Stolley M, Wolf B, Amendola A. Patellofemoral resurfacing arthroplasty: literature review and description of a novel technique. Iowa Orthop J. 2008;28:42–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahm DL, Kalisvaart MM, Stuart MJ, Slettedahl SW. Patellofemoral arthroplasty: outcomes and factors associated with early progression of tibiofemoral arthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(10):2554–2559. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson PA, Rivenburgh D. Focal anatomic patellofemoral inlay resurfacing: theoretic basis, surgical technique, and case reports. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008;39(3):337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies AP. High early revision rate with the FPV patello-femoral unicompartmental arthroplasty. Knee. 2013;20(6):482–484. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dirisamer F, Schöttle P. Die degenerative Erkrankung des Patellofemoralgelenks: diagnose und stadiengerechte Therapie. Zurich: AGA-Knie-Patellofemoral-Komitee; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feucht MJ, Cotic M, Beitzel K, Baldini JF, Meidinger G, Schöttle PB, Imhoff AB. A matched-pair comparison of inlay and onlay trochlear designs for patellofemoral arthroplasty: no differences in clinical outcome but less progression of osteoarthritis with inlay designs. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(9):2784–2791. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feucht MJ, Lutz PM, Ketzer C, Rupp MC, Cotic M, Imhoff AB, Pogorzelski J. Preoperative patellofemoral anatomy affects failure rate after isolated patellofemoral inlay arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2020;140(12):2029–2039. doi: 10.1007/s00402-020-03651-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh KM, Merican AM, Iranpour F, Deehan DJ, Amis AA. The effect of overstuffing the patellofemoral joint on the extensor retinaculum of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(10):1211–1216. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0830-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goh GS, Liow MH, Tay DK, Lo NN, Yeo SJ. Four-year follow up outcome study of patellofemoral arthroplasty at a single institution. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(6):959–963. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassaballa MA, Porteous AJ, Newman JH. Observed kneeling ability after total, unicompartmental and patellofemoral knee arthroplasty: perception versus reality. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12(2):136–139. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0376-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollinghurst D, Stoney J, Ward T, Pandit H, Beard D, Murray DW. In vivo sagittal plane kinematics of the Avon patellofemoral arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(1):117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.02.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imhoff AB, Feucht MJ, Bartsch E, Cotic M, Pogorzelski J. High patient satisfaction with significant improvement in knee function and pain relief after mid-term follow-up in patients with isolated patellofemoral inlay arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(7):2251–2258. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imhoff AB, Feucht MJ, Meidinger G, Schöttle PB, Cotic M. Prospective evaluation of anatomic patellofemoral inlay resurfacing: clinical, radiographic, and sports-related results after 24 months. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(5):1299–1307. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2786-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konan S, Haddad FS. Midterm outcome of Avon patellofemoral arthroplasty for posttraumatic unicompartmental osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(12):2657–2659. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laursen JO. High mid-term revision rate after treatment of large, full-thickness cartilage lesions and OA in the patellofemoral joint using a large inlay resurfacing prosthesis: HemiCAP-Wave®. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(12):3856–3861. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leadbetter WB, Ragland PS, Mont MA. The appropriate use of patellofemoral arthroplasty: an analysis of reported indications, contraindications, and failures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;436:91–99. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000172304.12533.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liow MH, Goh GS, Tay DK, Chia SL, Lo NN, Yeo SJ. Obesity and the absence of trochlear dysplasia increase the risk of revision in patellofemoral arthroplasty. Knee. 2016;23(2):331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lonner JH. Patellofemoral arthroplasty: the impact of design on outcomes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008;39(3):347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lonner JH, Bloomfield MR. The clinical outcome of patellofemoral arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2013;44(3):271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marullo M, Bargagliotti M, Vigano M, Lacagnina C, Romagnoli S. Patellofemoral arthroplasty: obesity linked to high risk of revision and progression of medial tibiofemoral osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2022;30(12):4115–4122. doi: 10.1007/s00167-022-06947-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKeever DC. Patellar prosthesis. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1955;37-A(5):1074–1084. doi: 10.2106/00004623-195537050-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metcalfe AJ, Ahearn N, Hassaballa MA, Parsons N, Ackroyd CE, Murray JR, Robinson JR, Eldridge JD, Porteous AJ. The Avon patellofemoral joint arthroplasty: two- to 18-year results of a large single-centre cohort. Bone Jt J. 2018;100-B(9):1162–1167. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B9.BJJ-2018-0174.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mofidi A, Bajada S, Holt MD, Davies AP. Functional relevance of patellofemoral thickness before and after unicompartmental patellofemoral replacement. Knee. 2012;19(3):180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monk AP, van Duren BH, Pandit H, Shakespeare D, Murray DW, Gill HS. In vivo sagittal plane kinematics of the FPV patellofemoral replacement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(6):1104–1109. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1717-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris MJ, Lombardi AV, Jr, Berend KR, Hurst JM, Adams JB. Clinical results of patellofemoral arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9 Suppl):199–201. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osarumwense D, Syed F, Nzeako O, Akilapa S, Zubair O, Waite J. Patellofemoral joint arthroplasty: early results and functional outcome of the Zimmer gender solutions patello-femoral joint system. Clin Orthop Surg. 2017;9(3):295–302. doi: 10.4055/cios.2017.9.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel A, Haider Z, Anand A, Spicer D. Early results of patellofemoral inlay resurfacing arthroplasty using the HemiCap wave prosthesis. J Orthop Surg. 2017;25(1):2309499017692705. doi: 10.1177/2309499017692705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pisanu G, Rosso F, Bertolo C, Dettoni F, Blonna D, Bonasia DE, Rossi R. Patellofemoral arthroplasty: current concepts and review of the literature. Joints. 2017;5(4):237–245. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pogorzelski J, Rupp MC, Ketzer C, Cotic M, Lutz P, Beeck S, Imhoff AB, Feucht MJ. Reliable improvements in participation in low-impact sports following implantation of a patellofemoral inlay arthroplasty at mid-term follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(10):3392–3399. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06245-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Provencher M, Ghodadra NS, Verma NN, Cole BJ, Zaire S, Shewman E, Bach BR., Jr Patellofemoral kinematics after limited resurfacing of the trochlea. J Knee Surg. 2009;22(4):310–316. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rammohan R, Gupta S, Lee PYF, Chandratreya A. The midterm results of a cohort study of patellofemoral arthroplasty from a non-designer centre using an asymmetric trochlear prosthesis. Knee. 2019;26(6):1348–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2019.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarda PK, Shetty A, Maheswaran SS. Medium term results of Avon patellofemoral joint replacement. Indian J Orthop. 2011;45(5):439–444. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.83761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(9):712–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tauro B, Ackroyd CE, Newman JH, Shah NA. The Lubinus patellofemoral arthroplasty. A five- to ten-year prospective study. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2001;83(5):696–701. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B5.0830696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der List JP, Chawla H, Zuiderbaan HA, Pearle AD. Survivorship and functional outcomes of patellofemoral arthroplasty: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(8):2622–2631. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3878-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Jonbergen HP, Werkman DM, Barnaart LF, van Kampen A. Long-term outcomes of patellofemoral arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willekens P, Victor J, Verbruggen D, VandeKerckhove M, Van Der Straeten C. Outcome of patellofemoral arthroplasty, determinants for success. Acta Orthop Belg. 2015;81(4):759–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yadav B, Shaw D, Radcliffe G, Dachepalli S, Kluge W. Mobile-bearing, congruent patellofemoral prosthesis: short-term results. J Orthop Surg. 2020;20(3):348–352. doi: 10.1177/230949901202000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zicaro JP, Yacuzzi C, AstoulBonorino J, Carbo L, Costa-Paz M. Patellofemoral arthritis treated with resurfacing implant: clinical outcome and complications at a minimum two-year follow-up. Knee. 2017;24(6):1485–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is stored on personal storage and available on request.