Germany, like other countries in Europe, is currently experiencing an international outbreak of imported diphtheria among refugees, presenting in most cases as cutaneous diphtheria ([1], European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) Rapid Risk Assessment: www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/diphtheria-cases-migrants-europe-corynebacterium-diphtheriae-2022.pdf).

Diphtheria is caused by toxigenic strains of Corynebacterium (C.) diphtheriae, C. ulcerans and (very rarely) C. pseudotuberculosis that produce the diphtheria toxin (DT) which is encoded by the tox gene. DT triggers local (pseudomembrane formation) and systemic (cardiac, nephrological and neurological) symptoms, with causal treatment only by rapid antitoxin administration.

C. diphtheriae is almost exclusively transmitted between humans. In Germany, most cases are associated with travel or migration; C. ulcerans and C. pseudotuberculosis are primarily transmitted zoonotically (via domestic and farm animals), typically within Germany. For the period 2010–2019, Germany reported the highest number of diphtheria cases within the WHO Europe Region, which includes 53 countries (2). In the past, classical respiratory diphtheria was the most common form of the disease in Germany (pharyngeal and/or laryngeal diphtheria, in vaccinated persons sometimes only presenting as pharyngitis or tonsillitis without pseudomembrane formation), but in recent years there have been almost exclusively cases of cutaneous diphtheria. This manifests as a secondary surgical-site infection (wound diphtheria) or cutaneous diphtheria of the classic ulcerative type, usually originating from superficial skin lesions (microtrauma, insect bites, burns); punched-out lesions or lesions covered with pseudomembranes are seen in patients with a typical disease course ([3], Figure 1). Mixed infections with staphylococci and streptococci are common.

Figure 1:

Cutaneous diphtheria

(Reprinted by courtesy of the Health Department of Sigmaringen, Sigmaringen, Germany)

When compared to respiratory diphtheria, which is primarily transmitted by droplets, cutaneous diphtheria is less contagious; the primary route of transmission is through close (skin) contact, but also through contaminated objects or surfaces. For decades, clusters and outbreaks of cutaneous diphtheria with toxigenic and non-toxigenic C. diphtheriae have been very rare in Germany; typically they have been associated with precarious circumstances such as homelessness, alcohol or drug dependence and/or cramped living conditions, especially when immunity to the diphtheria toxin is lacking or inadequate. Whereas in respiratory diphtheria, immediate antitoxin administration to neutralize DT not yet bound to cells is already required on suspicion of the disease, only very little DT is usually released in cases of cutaneous diphtheria; therefore, antitoxin therapy is generally not required except in case of more extensive injuries. Both types of disease manifestation should be treated with antibiotic eradication therapy using penicillin or erythromycin (www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/D/Diphtherie/Diphtherie.html).

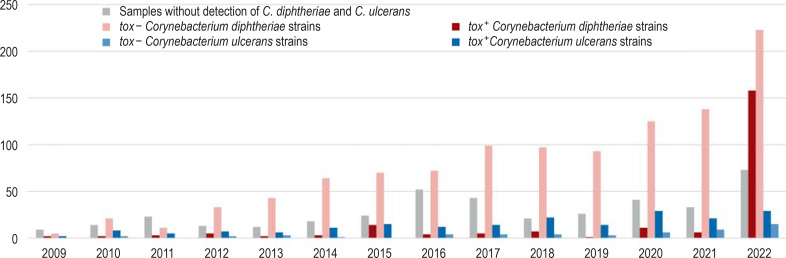

In the past 15 years, cases of cutaneous diphtheria have been caused mainly by zoonotic C. ulcerans contracted in Germany (approximately 1–20 cases/year), with occasional imported wound diphtheria cases caused by C. diphtheriae. In 2022, however, this picture changed abruptly: Since July 2022, a significant number of cases of imported diphtheria with tox+ C. diphtheriae strains has been observed in Germany among refugees primarily from Afghanistan and Syria. As of 5 March 2023, for example, at least 167 confirmed cases among recently arrived refugees have been reported to the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), almost all of which underwent laboratory testing at the German National Consiliary Laboratory on Diphtheria (NCLD, Konsiliarlabor für Diphtherie [KLD]) (Figure 2). A large proportion were diagnosed during medical examinations at reception centers, in some cases with the initial suspected diagnosis of scabies or mpox infection. Cases of cutaneous diphtheria were most common (n = 147), followed by cases of respiratory diphtheria (n = 15), while the remaining cases were asymptomatic or unspecified. There were no diphtheria-related deaths. So far, no secondary cases have occurred in Germany outside of shared accommodations, a fact that confirms the very low risk of infection for the general population. A high level of diphtheria immunity in the population is of great importance. There is a need to catch up on booster vaccinations with regard to this: In 2021, 53.4% of the population aged 18 and above had received a diphtheria vaccination in the preceding 10 years (5).

Figure 2:

Samples received at the German National Consiliary Laboratory on Diphtheria (NCLD), 2009–2022. Number of samples with detection of tox + Corynebacterium diphtheriae strains at the NCLD in 2022.

NCLD, German National Consiliary Laboratory on Diphtheria; tox-, gene for toxin production is missing; tox+, gene for toxin production is present

Whole genome sequencing of 156 C. diphtheriae strains of this cluster performed by the German National Consiliary Laboratory on Diphtheria identified five clinically indistinguishable clusters of ST-377 (n = 55), ST-384 (n = 27), ST-574 (n = 59), ST-466 (n = 4) sequence types and an additional cluster of ST-377 with (therapeutically relevant) erythromycin and clindamycin resistant strains (n = 11). At the same time, such clusters have also been observed among refugees in other European countries (1), with Germany having the highest number of cases. None of these clusters can be linked to a specific country of origin or a specific site (for example, a specific shared accommodation facility). Refugees’ route analyses by RKI and ECDC, as well as phylogenetic data from the German Consiliary Laboratory on Diphtheria suggest that infections occurred along the Balkan route.

In response to the current increase in diphtheria cases, specific antibiotic threshold values for C. diphtheriae and C. ulcerans were published by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) for the first time—based on data from the Pasteur Institute and the NCLD (www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints). All tox+ outbreak strains from 2022 cultured at NCLD tested as “I” for penicillin, i.e., sensitive at higher doses.

Thus, when examining refugees with skin lesions, a C. diphtheriae infection should be included in the differential diagnosis and swab material from the wound and throat should be sent to a microbiology laboratory for diphtheria testing after prior notification (special diagnostic testing). All potentially toxigenic corynebacteria should immediately be sent to the NCLD for further testing free of charge according to the RKI’s diphtheria guide, in particular for determining DT production using the Elek test (required by WHO case definition) and whole genome sequencing (extended reporting to the ECDC), if necessary. Furthermore, the vaccination status of patients, close contacts and caregivers should be checked and any missing vaccinations (basic immunization or booster shots) should be given. Information on eradication and post-exposure prophylaxis can be found in the RKI Guide to Diphtheria (www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/D/Diphtherie/Diphtherie.html).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the public health departments, state health authorities, shared accommodation facilities, outpatient and clinical facilities, and primary diagnostic microbiology laboratories, without whom the diphtheria surveillance conducted jointly by the RKI and the NCLD would not be possible.

Translated from the original German by Ralf Thoene, MD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

AS, AD, AB state that the German National Consiliary Laboratory on Diphtheria was supported as part of the RKI‘s Reference Laboratory Network (funded by the Federal Ministry of Health [BMG]).

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Badenschier F, Berger A, Dangel A, et al. Outbreak of imported diphtheria with Corynebacterium diphtheriae among migrants arriving in Germany, 2022. Euro Surveill. 2022;27 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.46.2200849. 2200849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muscat M, Gebrie B, Efstratiou A, Datta SS, Daniels D. Diphtheria in the WHO European region, 2010 to 2019. Euro Surveill. 2022;27 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.8.2100058. 2100058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sing A, Berger A, Dangel A, et al. Übertragung von Hautdiphtherie innerhalb einer Familie—Erster Diphtherie-Ausbruch in Deutschland seit fast 40 Jahren. Epid Bull. 2019;20:169–171. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dangel A, Berger A, Konrad R, Bischoff H, Sing A. Geographically diverse clusters of nontoxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae infection, Germany, 2016-2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1239–1245. doi: 10.3201/eid2407.172026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rieck T, Steffen A, Feig M, Siedler A. Impfquoten bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland - Aktuelles aus der KV-Impfsurveillance. Epid Bull. 2022;49:3–23. [Google Scholar]