Abstract

Introduction:

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a leading cause of blindness worldwide. Recent decades have seen rapid progress in the management of diabetic eye disease, evolving from pituitary ablation to photocoagulation and intravitreal pharmacotherapy. The advent of effective intravitreal drugs inhibiting anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) marked a new era in DR therapy. Sustained innovation in DR pharmacotherapy has since produced several promising biologics targeting angiogenesis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and neurodegeneration.

Areas covered:

This review surveys traditional, contemporary, and emerging therapeutics for DR, with an emphasis on anti-VEGF therapies, receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway inhibitors, integrin pathway inhibitors, gene therapy “biofactory” approaches, and novel systemic therapies. Some of these investigational therapies are being delivered intravitreally within sustained release implants for extended durability, and some investigational therapies are being delivered non-invasively via topical and systemic routes. These strategies hold promise for early and long-lasting treatment of DR.

Expert opinion:

The evolving therapeutic landscape of DR is rapidly expanding our toolkit for the effective and durable treatment of blinding eye disease, but further research is required to validate the efficacy of novel therapeutics and characterize real world outcomes.

Keywords: Diabetic macular edema, diabetic retinopathy, vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF

1. Introduction

The global prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) has reached epidemic proportions, affecting 1 in 10 adults aged 20-79 worldwide [1]. The increasing prevalence of sedentary lifestyles and Western dietary habits, alongside global population aging, is expected to drive the prevalence of DM as high as 1 in 8 adults by 2045 [1]. Diabetic retinopathy (DR) and diabetic macular edema (DME) are among the most common and specific complications of DM [2]. Within the first two decades of diagnosis, virtually 100% of individuals with Type 1 DM and 60% of those with Type 2 DM will go on to develop some degree of DR [3]. Currently, 1 in 3 patients with DM have some degree of DR, and nearly 1 in 15 have vision-threatening proliferative DR (PDR) or DME [2]. Therefore, the progressive and ultimately blinding nature of uncontrolled DR places it among the leading causes of blindness [2]. In addition to the significant socioeconomic and healthcare burden associated with visual impairment [4,5], several studies have demonstrated the severity of DR to be correlated with higher rates of psychological distress [6] and overall poorer quality of life [7].

Given these societal implications, there has been great interest in the development of novel therapies for DR. This review covers the pathophysiology and treatment of DR, with an emphasis on anti-VEGF therapies, receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway inhibitors, integrin pathway inhibitors, gene therapy “biofactory” approaches, and novel systemic therapies. These strategies may hold promise for the early treatment of DR, as some investigational therapies are being delivered intravitreally within sustained release implants for extended durability, and some investigational therapies are being delivered non-invasively via topical and systemic routes.

1.1. Pathophysiology

The various metabolic mechanisms, pathologic processes, and systemic comorbidities involved in the development and progression of DR each provide important targets for disease-modifying therapeutics. Moreover, the clinical features of DR represent important biomarkers of disease severity and prognosis. The ability to readily monitor these changes via simple funduscopic examination provides invaluable clinical data to guide management and assess response to intervention.

The retinal vasculature, lacking autonomic innervation, relies exclusively upon local autoregulatory mechanisms to maintain physiologic blood flow. Pericytes and endothelial cells of the capillary walls play a critical role in this process by regulating capillary wall contractility and vasomotor response to perfusion pressure [8]. Hyperglycemia-induced pericyte loss and endothelial dysfunction are among the earliest hallmarks of DR [9], compromising retinal vascular autoregulation and altering physiologic hemodynamics. Metabolic derangements involving the advanced glycation end products (AGEs), protein kinase C (PKC), polyol, and hexosamine pathways additionally cause the thickening of the capillary basement membrane (BM) and breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier [10], increasing vascular permeability and contributing to mechanical retinal disruption as plasma and lipids leak into the local tissue. The AGE and PKC pathways are further activated by circulating lipids and fatty acids, potentially enhancing microvascular injury in systemic hyperlipidemia [11]. Finally, a chronic low-grade inflammatory state in DM is thought to promote leukostasis and platelet aggregation, causing capillary occlusion and consequent retinal ischemia [12]. In the advanced stages of DR, chronic retinal hypoxia triggers the release of angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) isoforms [13] and angiopoietins [14] (Figure 1). The resulting pathologic endothelial cell proliferation causes retinal neovascularization, significantly increasing the risk of vision-threatening complications.

Figure 1. Key angiogenic factors and receptors implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema.

The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family consists of six major signaling proteins (VEGF-A through F). VEGF-A has been identified as the primary driver of angiogenesis in neovascular retinal disease. VEGF proteins interact with VEGF receptors (VEGFR) and neuropilin (Nrp) receptors on endothelial surfaces to promote neovascularization and vascular permeability. Placental growth factor (PIGF) has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of DR via its interactions with VEGFR-1. A second pathway involving interactions between angiopoietin (Ang) signaling proteins and endothelial tyrosine kinases (Tie) has also been implicated in angiogenesis. These signaling proteins and their receptors represent attractive targets for novel DR therapeutics. Image reproduced from [198], © 2017 mjeltsch, licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 license.

Several clinically observable features of DR correlate directly with these processes (Figure 2). Focal areas of weakness in retinal capillary walls due to pericyte and endothelial loss result in outpouchings observed clinically as microaneurysms (MAs), while breakdown of the capillary blood-retinal barrier causes intraretinal dot and blot hemorrhages. DME – the most common vision-threatening complication of DR [15] – develops as lipoproteins, crystalloids, and plasma leak through damaged capillary walls and accumulate in the inner and outer plexiform layers as serous fluid and hard exudates (HEs). Capillary obstruction and tissue hypoperfusion due to impaired autoregulation, BM thickening, leukostasis, and platelet aggregation results in cotton wool spots (CWS), venous beading, and capillary dropout on retinal angiography. Finally, endothelial proliferation driven by chronic microvascular ischemia results in the formation of visible intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMA) and neovascularization (NV), with consequent vision-threatening complications such as vitreous hemorrhage (VH) and tractional retinal detachment (TRD).

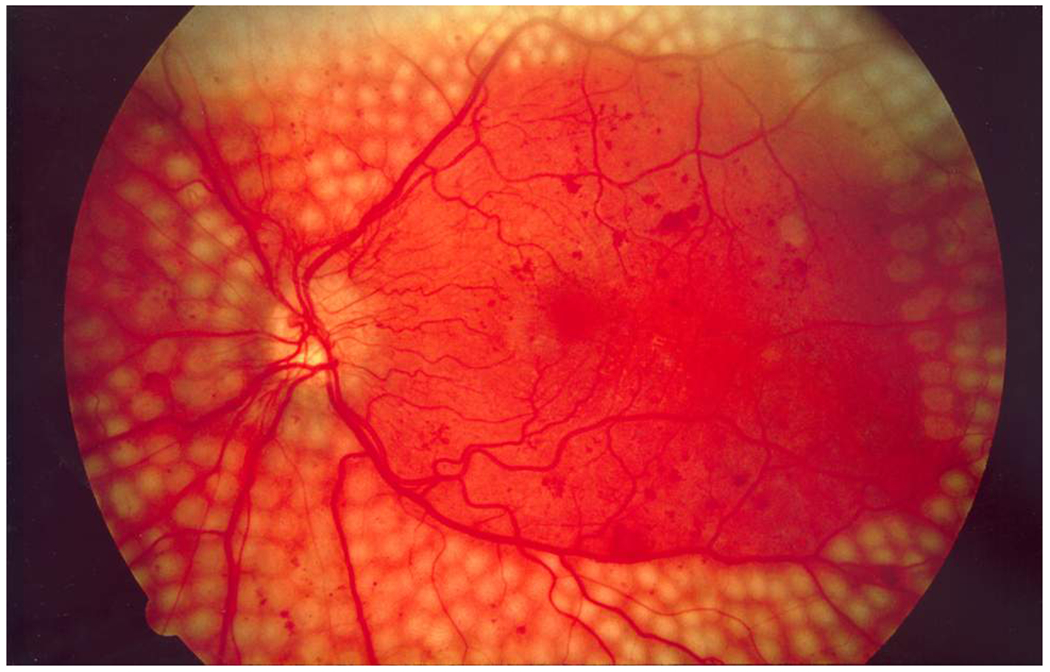

Figure 2. Clinical features of diabetic retinopathy.

(a) The clinical appearance of severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, with intraretinal hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, hard exudates, and venous beading visible in the photo. Reproduced from [199], © 2016 Besenczi et al., licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons BY 4.0 license. (b) Proliferative diabetic retinopathy involves neovascularization of the disc, seen here, or neovascularization elsewhere in the retina. Public domain image from National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health.

1.2. Definitions and disease staging

DR is divided into two broad stages: Non-proliferative DR (NPDR) and PDR. NPDR represents the earlier stages of the disease, characterized (progressively) by retinal MAs, intraretinal hemorrhages, HEs, venous beading, and IRMAs. In the later stages of DR, the development of neovascularization (NV) defines the onset of PDR and portends a poorer visual prognosis. Subsequent retinal complications include VH, fibrovascular membrane formation, and TRD.

Since the late 1960s, a concerted international goal has been to design standardized, evidence-based disease classification schemes to guide DR screening, intervention, and research. These efforts ultimately yielded the Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale (DRSS), which was implemented in the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) trial. The DRSS features 13 multifaceted stages of DR, determined by evaluating stereoscopic fundus photographs of seven standardized retinal fields [16]. DME may develop in any stage and is identified by retinal thickening and/or the presence of HEs; DME that occurs within 500 µm of the macular center is additionally termed clinically significant macular edema (CSME) when observed clinically and center-involving DME (CI-DME) when observed on OCT. CSME is classically an indication for interventional therapy due to its heightened threat to visual acuity [17].

Owing to its precision, reproducibility, and prognostic value [18], the DRSS has since become widely accepted as a gold-standard for diagnosing and staging DR, and tracking disease progression in clinical trials. A 2- or 3-step change in DRSS score has been validated as a signifier of clinically significant change in disease severity [19] and is accepted by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a primary endpoint demonstrating the disease-modifying efficacy of novel therapeutics.

While these classification systems have found great utility in research, their complexity limits widespread clinical implementation. In 2003, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) developed a simplified five-stage International Clinical Disease Severity Scale for DR to address this concern with a system that could be implemented practically and consistently in a broad range of clinical contexts [20]. Based on major features of the DRSS, the scale includes four stages of NPDR (none, mild, moderate, severe) and a final stage for PDR.

1.3. Overview of therapeutic strategies for DR

The recognition of DR as a major cause of vision loss in the mid-1900s led to the implementation of several early interventions to prevent blindness. By the 1960s, these ranged from conservative measures, such as daily aspirin intake, to aggressive surgical interventions, such as pituitary ablation (hypophysectomy) in vision-threatening PDR. However, these therapies were inconsistent in efficacy and often associated with systemic morbidity. The advent of retinal photocoagulation and its subsequent validation as a safe and effective therapy for DR marked a key breakthrough in DR therapy. The later development of minimally-invasive pars plana vitrectomy in the 1970s and efficacious intravitreal pharmacotherapies in the 2000s have further transformed the therapeutic landscape of DR.

The contemporary approach to managing DR currently consists of four major strategies: systemic risk factor modification, retinal photocoagulation, pharmacotherapy, and vitreoretinal surgery. In recent years, biological therapies targeting the various pathophysiologic mechanisms of DR have emerged as important disease-modifying treatments for DR and DME. In what follows, we first provide a brief overview of the traditional approaches to DR/DME – namely systemic risk factor modification and phototherapy for DR – followed by a detailed review of contemporary and novel pharmacotherapeutics for the treatment of diabetic eye disease, with particular emphasis on the emerging role of biological therapeutics.

2. Systemic risk factor modification

Tight control of blood glucose is a mainstay of DR prevention and management. Multiple landmark randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have demonstrated a major reduction in the rates of DR development and progression when intensive glycemic control (IGC) is implemented early in DM, targeting a hemoglobin A1c of 7.0% [21–24]. The protective effects of early ICG have been found to last up to thirty years [25,26]. Conversely, it is known that many patients will go on to develop some degree of DR regardless of glycemic control [27], and patients with long-standing uncontrolled DM may derive less benefit from ICG later in the disease course [28,29]. Glycemic control may consequently play only a partial role in managing DR, and is most critical early in the disease course. In patients with a prior history of uncontrolled DM, alternative disease-modifying therapeutics may frequently be required to prevent vision-threatening complications, even alongside the implementation of ICG.

Hypertension is additionally recognized as a major risk factor for the development and progression of DR [30], although an association between hypertension and DME is not as clearly established [31,32]. Tight blood pressure control is currently considered an essential strategy in managing DR, and has been found to modestly reduce the risk of DR-related complications for up to 5 years [33]. However, intensive blood pressure control does not appear to be sufficient to protect against CSME, PDR, or long-term vision loss in DM [33].

Hyperlipidemia is another common comorbidity in patients with DM [34], and a modest risk factor for developing DR and DME [35]. Anti-hyperlipidemics significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular complications in patients with DM and may also benefit those with DR [36]. There is mounting evidence that fenofibrate therapy in patients with DR significantly slows the progression of retinopathy and may reduce the risk of DME [36–39]. However, this benefit interestingly appears to be independent of serum lipid levels [36]. While fenofibrate is not widely employed in treating DM or DR at this time [40], these findings suggest that fenofibrate warrants further exploration as a potential low-cost oral therapy for reducing the risk of DR progression and ophthalmic complications. A Phase III trial (DRCR.net Protocol AF) is currently recruiting.

3. Light and laser therapy

Retinal photocoagulation involves administering high-intensity pulses of light energy to the retina, which are absorbed by pigments in the RPE and choroid (e.g., melanin) and converted into thermal energy. The local rise in tissue temperature denatures intracellular proteins and causes focal destruction (coagulative necrosis) of the RPE and outer retinal layers [41]. Although this process results in tissue atrophy and permanent chorioretinal scars, photocoagulation has been demonstrated to improve inner retinal oxygenation and relieve tissue hypoxia [42] and is of undeniable benefit in the management of PDR and DME [43].

In the late 1970s, the Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DRS) demonstrated that diffuse laser panretinal photocoagulation (PRP; Figure 3) of the peripheral retina reduces the risk of severe vision loss in PDR by 60% at 2 years [44]. The ETDRS later validated a similar protocol for the treatment of PDR as well as severe NPDR [45]. Long-term follow-up studies have demonstrated the remarkable and durable benefits of PRP in preventing severe vision loss from PDR, with 84% of treated patients retaining BCVA of 20/40 or better in at least one eye [46]. The significant findings of the DRS and ETDRS have established PRP as the enduring first-line standard of care for PDR. However, PRP may result in long-term visual side-effects such as visual field constriction, decreased color vision, contrast sensitivity, night vision, and/or reduced light-to-dark adaptation [47]. Other potential complications include retinal detachment, worsening macular edema, choroidal effusion, and choroidal neovascularization [47].

Figure 3. Pan-retinal (scatter) laser photocoagulation for proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) is currently the standard of care for the treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) and has been demonstrated to be more effective than targeted laser therapy. In this patient with PDR, dense chorioretinal PRP scars are seen in the near periphery extending to the arcades and as close as three disc-diameters from the macular center temporally. Public domain image from National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health.

The ETDRS additionally validated two protocols for macular photocoagulation in the treatment of clinically significant DME: Focal laser photocoagulation of leaking microaneurysms or IRMAs identified on fluorescein angiography or grid laser photocoagulation for areas of diffuse edema [48]. Focal/grid photocoagulation can be safely applied as close as 500µm from the macular center or disc margin and significantly reduces the risk of severe vision loss in patients with CSME [17,49]. However, macular photocoagulation increases the risk of permanent scotomata or inadvertent foveal injury.

While modern intravitreal anti-VEGF injections have largely replaced macular photocoagulation in treating DME due to their equivalent or superior efficacy and safety profile [50–53], PRP remains the standard of care for PDR. Laser therapy additionally remains a viable alternative to IVT in specific situations, such as for refractory or non-central DME, patients with unreliable follow-up or contraindications to anti-VEGF therapy, and in contexts without access to modern pharmacotherapies [54,55]. Recent technological innovations have aimed to improve the safety profile of phototherapy for diabetic eye disease while maintaining therapeutic efficacy, particularly in treating DME [43]. These advances include non-destructive subthreshold laser therapies [56] such as the MicroPulse system (IRIDEX Corp), as well as novel laser delivery systems such as the pattern scanning laser (PASCAL, Topocon Corp) and navigated laser photocoagulation (NAVILAS, OD-OS Inc).

4. Targeted pharmacotherapy

4.1. Corticosteroids

Early targeted pharmacotherapy for diabetic eye disease consisted mainly of corticosteroid IVT. In addition to their well-established anti-inflammatory properties, intraocular corticosteroids decrease vascular permeability, inhibit the expression of angiogenic factors, and potentially exert neuroprotective effects on the retina [57]. Corticosteroids, therefore, are highly effective for treating diabetic eye disease, particularly DME [58]. However, long-term use of intraocular corticosteroids is commonly associated with complications such as cataract formation and elevated intraocular pressure [59], somewhat limiting clinical usage, especially in pseudophakic patients. Currently, there are three major options for intraocular corticosteroid therapy: intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide (IV-TA), a biodegradable dexamethasone intravitreal implant, and a non-biodegradable fluocinolone acetonide implant.

The considerable efficacy of IV-TA as an adjunct to focal/grid photocoagulation in the treatment of refractory DME has been well established [59–68]. IV-TA may also be a useful adjunct to PRP in managing high-risk PDR with CSME [64,69–72]. However, the effects of IV-TA alone are short-lived as compared to photocoagulation [65,73,74], and repeated IV-TA injections may be required to achieve sustained benefits [60], increasing the risk of cataract formation/progression and ocular hypertension [74,75]. Each IV-TA injection is also associated with a significantly higher risk of endophthalmitis compared to non-steroidal IVT [76,77]. Despite its efficacy, IV-TA is therefore not a first-line therapy for DME, and is not FDA-approved for this indication.

Sustained-release intravitreal steroid implants have been developed to improve the risk/benefit profile associated with recurrent IV-TA injections. Ozurdex (Allergan) is an intravitreal, biodegradable dexamethasone implant that is safe, effective, and FDA-approved for the treatment of DME [78,79]. The dexamethasone intravitreal implant may be beneficial in cases of DME unresponsive to anti-VEGF injections, as an adjunct to macular photocoagulation [80], or as a first-line therapy in vitrectomized or pseudophakic patients [81,82]. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant has also been shown to prevent progression of NPDR and PDR and may improve disease severity in the long term [83]. It is of particular utility in vitrectomized eyes, where its therapeutic effects have been found to last longer than anti-VEGF agents [84]. Finally, due to its sustained effects, the dexamethasone implant may be more cost-effective than recurrent anti-VEGF injections for DME in certain contexts [85]. A non-biodegradable fluocinolone acetonide sustained delivery device (Iluvien, Alimera Sciences) is also now FDA-approved for the treatment of recalcitrant DME, with therapeutic effects lasting up to 3 years [86,87].

The validation of intravitreal therapy (IVT) as a safe and effective means of treating ocular disease has transformed the field of ophthalmology. In addition to being less destructive, better tolerated, and overall safer than retinal photocoagulation, IVT may be administered in cases where media opacities preclude the use of laser therapy. However, IVT often requires long-term, recurrent monthly injections, which are burdensome and suboptimal without reliable patient follow-up. Each IVT session is also associated with a risk of rare but serious complications such as endophthalmitis, elevated intraocular pressure, retinal detachment, crystalline lens injury or dislocation, and systemic drug absorption [88]. Multiple novel pharmacotherapeutics have therefore been investigated to reduce risk, increase efficacy, and extend durability of IVT. Novel drug delivery strategies have also been explored as alternatives to IVT, including surgically implanted reservoirs, suprachoroidal gene therapy, eyedrops, and oral agents.

4.2. Conventional VEGF inhibitors

One of the major retinal responses to ischemia is the secretion of hypoxia-regulated growth factors that promote neovascular vasoproliferation to meet tissue metabolic demand [89]. VEGF signaling is the most widely studied driver of endothelial cell proliferation, vascular permeability, and neovascularization in ischemic retinal disease [90]. VEGF expression, particularly VEGF-A, consequently plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of PDR [91] and contributes significantly to the development of DME [92]. Biological anti-VEGF agents have therefore found great success in the treatment of DME [93,94] and DR [95]. Anti-VEGF IVT is now the first-line standard of care for DME, and an important adjunct to PRP in the management of PDR.

The aptamer pegaptanib (Macugen, Eyetech Pharmaceuticals, Inc), a direct inhibitor of the VEGF-A 165 isoform [96], was the first commercially available intravitreal anti-VEGF agent. However, it has since been superseded by newer, superior intravitreal anti-VEGF agents blocking the activity of all VEGF-A isoforms. These include ranibizumab (Lucentis, Novartis Ophthalmics), bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech), and aflibercept (Eylea, Regeneron).

Ranibizumab is a recombinant monoclonal antibody fragment approved for the treatment of nAMD in 2005 [97] and subsequently for DR and DME in 2015. Ranibizumab binds strongly to all VEGF-A isoforms [97], resulting in more complete VEGF-A blockade than pegaptanib. Several large RCTs – including the READ-2 [98], READ-3 [99], RESOLVE [100], DRCR.net Protocol I [101,102] and Protocol T [103], RESTORE [104,105], REVEAL [106], and RISE/RIDE [107,108] studies – have established the long-term safety and efficacy of ranibizumab in treating CSME, with or without adjunctive macular laser therapy. These trials have demonstrated significant improvements in BCVA, degree of DME, and quality of life following treatment with intravitreal ranibizumab, with equivalent or superior long-term outcomes compared to photocoagulation alone [102,105]. Early ranibizumab IVT has been shown to be more effective than delayed intervention [108]. Adjunctive dexamethasone injection may improve resorption of DME, but has not been found to impact visual outcome in eyes treated with ranibizumab [109].

Ranibizumab is also effective in improving DRSS score in eyes with moderate-to-severe NPDR and reducing risk of conversion to PDR [110,111]. In eyes with PDR, the PRIDE [112], PROTEUS [113], and DRCR.net Protocol S [114] studies found that ranibizumab therapy may result in superior visual outcomes, fewer long-term complications, and lower vitrectomy rates as compared to PRP alone. Secondary analysis of pooled data from the RISE and RIDE trials additionally demonstrated regression in DR severity and a significant reduction in rate of conversion to PDR in patients with DME treated with ranibizumab [110,115]. In patients with VH, the DRCR.net Protocol N trial and others demonstrated that intravitreal ranibizumab improves BCVA [116,117], but may only reduce vitrectomy rate in mild-to-moderate VH [116]. In the United States, intravitreal Ranibizumab is dosed at 0.3mg per injection for DME or DR [110,111]. Higher-dose ranibizumab 0.5mg, as is used in nAMD and macular edema associated with retinal vein occlusions, has not demonstrated significantly superior efficacy in DME or PDR [99,115].

A ranibizumab port delivery system (Susvimo, Genentech) has been developed to allow continuous drug delivery and reduce the need for recurrent intravitreal injections. After surgical implantation of a refillable intraocular reservoir, the port delivery system requires as few as two treatments per year to achieve equivalent efficacy to monthly ranibizumab in nAMD for up to two years [118]. However, this system has been associated with an increased risk of endophthalmitis compared to IVTs, affecting up to 2% of study patients and often occurring in the context of conjunctival retraction or erosion [119]. The port delivery system with ranibizumab was FDA-approved for nAMD in 2021, with a black-box warning regarding endophthalmitis risk. Two ongoing Phase 3 RCTs, PAVILION and PAGODA, are assessing the use of a 24-week Susvimo regimen in DR and DME, respectively, and are expected to conclude in 2024.

Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds all VEGF-A isoforms and is FDA approved for intravenous use in a number of systemic malignancies. Intravitreal administration of bevacizumab was proposed around the same time as the early ranibizumab trials in 2005 as an off-label, more cost-effective alternative for nAMD [120]. Multiple studies have since established intravitreal bevacizumab as a safe and effective therapy for a range of ophthalmic indications, including DME [121–124] and as an adjunct to PRP in PDR [125,126]. The BOLT study additionally demonstrated the superiority of bevacizumab over macular laser for CSME [124,127]. Others have found bevacizumab to be as effective as ranibizumab in the treatment of DME [122,128], and secondary analysis of the DRCR.net Protocol T trial suggests that bevacizumab may also be as effective as ranibizumab in improving DRSS score in both NPDR and PDR over the long term [129]. However, bevacizumab is not currently FDA-approved for ophthalmic use and requires on-demand compounding for intravitreal administration. Nevertheless, owing largely to its significant cost-effectiveness over other anti-VEGF agents [130], intravitreal bevacizumab remains commonplace in the treatment of over 50 ophthalmic disorders [131].

Aflibercept is a soluble fusion protein decoy receptor that strongly binds all VEGF-A isoforms, as well as related angiogenic factors VEGF-B and placental growth factor (PGF), acting as a “VEGF trap” to inhibit activation of the VEGF pathway [132]. The VIVID and VISTA trials established the safety and efficacy of intravitreal aflibercept 2mg in the treatment of DME, demonstrating improvements in visual function and macular thickness superior to those seen with macular photocoagulation and sustained for up to 3 years [133,134]. These findings led to the FDA approval of intravitreal aflibercept 2mg for treating DME in 2015. In the DRCR.net Protocol T study, aflibercept was associated with superior visual outcomes compared to bevacizumab at 2 years in eyes with baseline BCVA of 20/50 or worse [103,122]. The PANORAMA [135] and DRCR.net Protocol W [136] studies, as well as secondary analysis of the Protocol T data [129], additionally found aflibercept IVT to be associated with a clinically significant (2-step) improvement in DRSS score among eyes with moderate to severe NPDR, although fixed-dosing (e.g. every 16 weeks) may be necessary to sustain these improvements over the long term [135,136]. The DRCR.net Protocol AB trial results suggest that early aflibercept IVT may result in similar long-term visual outcomes as early vitrectomy with PRP for PDR, but with slower recovery of BCVA, higher likelihood of recurrence, less impact on NV regression [137].

Despite the success of these IVTs, cost-benefit analyses of the Protocol T data have not found the difference in long-term visual outcomes to support the cost-effectiveness of aflibercept or ranibizumab over bevacizumab in DME at current drug pricing [130,138]. The necessity for recurrent therapy also increases the risk and costs associated with IVT, and may result in poorer patient compliance due to significant treatment burden. Consequently, patients with DME in practice tend to receive fewer injections and exhibit worse outcomes than patients enrolled in RTCs [139,140]. There is a critical need to develop novel IVTs that can maintain more significant and lasting effects with fewer treatment sessions.

4.3. Emerging VEGF inhibitors

The validation of intravitreal therapy (IVT) as a safe and effective means of treating ocular disease has transformed the field of ophthalmology. In addition to being less destructive, better tolerated, and overall safer than retinal photocoagulation, IVT may be administered in cases where media opacities preclude the use of laser therapy. However, IVT often requires long-term, recurrent monthly injections, which are burdensome and suboptimal without reliable patient follow-up. Each IVT session is also associated with a risk of rare but serious complications such as endophthalmitis, elevated intraocular pressure, retinal detachment, crystalline lens injury or dislocation, and systemic drug absorption [88]. Multiple novel pharmacotherapeutics have therefore been investigated to reduce risk, increase efficacy, and extend the durability of IVT. Novel drug delivery strategies have also been explored as alternatives to IVT, including surgically implanted reservoirs, suprachoroidal gene therapy, eyedrops, and oral agents.

Brolucizumab (Beovu, Novartis) is a small single-chain variable antibody fragment that inhibits all VEGF-A isoforms and is FDA-approved for treating nAMD and DME [141]. The exceptionally low molecular weight and high molecular stability of the brolucizumab antibody fragment allow high-concentration injections and efficient retinal drug penetration [142]. Three RCTs (KITE, KESTREL, and KINGFISHER) have demonstrated superior outcomes and durability of brolucizumab 6mg over aflibercept 2mg in DME [142,143]. However, although its risk/benefit profile is overall favorable, brolucizumab may be associated with higher rates of retinal vasculitis and vaso-occlusive complications compared to other anti-VEGF agents [141,144]. Such complications require early recognition and prompt intervention [145], necessitating careful post-injection surveillance.

Conbercept (Lumitin, Chengdu Kanghong Biotech) is a recombinant anti-VEGF fusion protein with a similar structure to aflibercept, acting as a VEGF trap to bind all isoforms of VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and PIGF with high affinity [146]. Early studies and the Phase 3 PHOENIX RCT suggested conbercept may be a promising new anti-VEGF IVT for nAMD; however, two additional Phase 3 RCTs (PANDA-1 and PANDA-2) studying conbercept in nAMD failed to demonstrate non-inferiority compared to aflibercept 2mg. While the Phase 3 SAILING trial has demonstrated the superiority of conbercept over macular photocoagulation for treating DME [147], further research is required to evaluate its efficacy compared to other available anti-VEGF agents.

KSI-301 (Kodiak Sciences), also known as tarcocimab, is an anti-VEGF antibody biopolymer conjugate designed for extended half-life to increase intraocular durability [148] and has been assesed in nAMD [149], retinal vein occlusion[150] and NPDR. However, further development was discontinued after 2 Phase 3 RCTs in DME failed to meet their primary endpoints.

Finally, OPT-302 (Opthea Limited) is an anti-VEGF R3 receptor fusion protein that binds and blocks the activity of VEGF-C and VEGF-D. A recent Phase 2a Trial (NCT03397264) studying combined therapy with OPT-302 and aflibercept has demonstrated clinically significant visual acuity gain in patients with refractory DME treated with combination therapy [151]. These findings suggest the utility of combined inhibition of multiple VEGF isoforms in patients with refractor DME. Further research is ongoing.

4.4. Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Three major VEGF receptor (VEGFR) tyrosine kinases have been implicated in DR/DME pathogenesis, with variable affinity for VEGF family isoforms [152]: VEGFR-1 is stimulated by VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and PIGF; VEGFR-2 is stimulated by VEGF-A, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D; and VEGFR-3 is stimulated by VEGF-C and VEGF-D. VEGFR-2 is the predominant receptor involved in angiogenic signaling and regulation of vascular permeability, contributing significantly to the development of PDR and DME in response to VEGF-A upregulation [153]. However, evidence suggests that VEGF-A inhibition by conventional anti-VEGF IVT may upregulate the expression of other angiogenic factors, such as VEGF-C and VEGF-D [154]. Pan-VEGF inhibition via VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) is therefore an attractive strategy to mitigate the downstream effects of VEGF overexpression in ischemic retinopathy and potentially improve outcomes in recalcitrant disease.

Vorolanib is a small molecule TKI that binds all three VEGFRs, effectively blocking all VEGF activity in the target tissue [155]. Vorolanib has been integrated into a bioerodible intravitreal implant to treat neovascular retinal disease (EYP-1901, EyePoint Pharmaceutical). A Phase I RCT is currently ongoing to evaluate the safety of EYP-1901 in nAMD (DAVIO), and a Phase 2 RCT (PAVIA) has recently begun to evaluate the safety EYP-1901 in NPDR (NCT05383209).

Axitinib is another small molecule TKI that inhibits all three VEGFRs. CLS-AX (Clearside Biomedical) is a suprachoroidal injection of axitinib that has been developed as a potential bi-annual therapy for nAMD [156]. A Phase I/IIa trial, OASIS, recently reported positive safety results in nAMD [157]. This therapy could be assessed in DR in the future. Similarly, a hydrogel-based intravitreal axitinib implant has also been developed by Ocular Therapeutix (OTX-TKI), and a Phase I RCT recently reported positive preliminary safety data in nAMD [158]. Ocular Therapeutix plans to further investigate the utility of OTX-TKI in DR.

4.5. Angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway inhibitors

Angiopoietin (Ang) growth factors are produced by vascular support cells such as capillary pericytes to promote vascular development and maturation [159]. Ang-1 and Ang-2, along with their vascular endothelial transmembrane receptor (Tie2), have been found to play important roles in the regulation of inflammation, vascular stability, vessel permeability, and angiogenesis in diabetic eye disease [159]. The angiopoetin-Tie2 pathway is, therefore an attractive target for novel DR therapeutics.

Faricimab (Vabysmo, Genentech) is a novel anti–Ang-2/anti-VEGF antibody developed for intravitreal injection in the treatment of nAMD and DME [160]. It is hypothesized that dual inhibition of both the VEGF and Ang-Tie pathways by faricimab may result in more potent and durable therapeutic effects than anti-VEGF therapy alone. This has been confirmed by multiple large trials, including the Phase 3 TENAYA and LUCERENE RCTs [161], which demonstrated that faricimab injections administered at fixed intervals of up to every 16 weeks are safe and non-inferior to aflibercept injections every 8 weeks in nAMD. The Phase 2 BOULEVARD RCT additionally demonstrated superior visual outcomes in DME treated with monthly faricimab compared to monthly ranibizumab [160], while the Phase 3 YOSEMITE and RHINE RCTs demonstrated non-inferior visual gains and superior anatomic outcomes with faricimab dosed up to every 16 weeks versus aflibercept every 8 weeks [162]. Faricimab may therefore decrease the treatment burden associated with other anti-VEGF agents, consequently improving patient compliance. The FDA approved intravitreal faricimab for use in both DME and nAMD in early 2022 [163]. Faricimab is also being assessed in a phase 2 study (MAGIC, NCT05681884) in patients with NPDR.

4.6. Integrin pathway inhibitors

Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane glycoprotein receptors that act as cell adhesion molecules, allowing cell adhesion to and migration along proteins in the extracellular matrix. Integrins also play key roles in inflammation, vascular leakage, angiogenesis, neurodegeneration, and fibrosis [164]. A number of integrins have been specifically implicated in the pathophysiology of proliferative vitreoretinal disorders through their roles in the vitreous interphase and at neovascular fronds [165]. Integrins may therefore represent promising therapeutic targets in DME and PDR [165].

Risuteganib (Luminate, Allegro Ophthalmics) is an intravitreally-administered synthetic oligopeptide that binds and inhibits four integrin heterodimers [166]. A phase IIb RCT comparing risuteganib to bevacizumab in DME has produced promising results with durability up to 12 weeks [167]. Additional intravitreal integrin inhibitors under investigation have included THR-687 (Oxurion) [168], volociximab (Ophthotech Corporation) [169], and AG-73305 (Allgenesis Biotherapeutics) [170]. A topical (eyedrop) anti-integrin agent, originally named SF0166 (SciFluor) [171,172] and now named OTT166 (Ocuterra Therapeutics) [173], is also being investigated.

4.7. Gene therapy

Gene therapy is a novel retinal therapy approach that modifies cellular gene expression by introducing synthetic genetic material into the intracellular space to prevent, halt, or reverse a disease process [174]. Gene therapy has the potential to induce durable therapeutic effects by permanently altering the local genome to produce therapeutic proteins continuously. In recent years, gene therapy has been gaining momentum as a viable means of treating a range of ophthalmic disorders, including both classical inherited retinal diseases [175] and multifactorial retinal diseases, such as AMD [176], uveitis [177], and DR [178]. In 2017, the FDA approved the gene therapy voretigene neparvovec (Luxturna, Spark Therapeutics) for Leber congenital amaurosis [179], marking a historic landmark as the first gene therapy approved for the treatment of an inherited human disease.

RGX-314 (REGENXBIO Inc.) is a novel gene therapy “biofactory” intervention for neovascular retinal diseases that delivers a transgene coding for an anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody fragment to the retina via an adeno-associated virus 8 vector. The drug is administered via a single subretinal or suprachoroidal injection, and is designed to induce lasting cellular expression of anti-VEGF antibodies within the retina. Two Phase IIb/III trials (ASCENT and ATMOSPHERE) are currently evaluating the subretinal delivery of RGX-314 in nAMD, while a Phase II trial (AAVIATE) is evaluate suprachoroidal delivery in nAMD. An additional Phase II clinical trial (ALTITUDE) is evaluating the safety of suprachoroidal RGX-314 in DR, with encouraging preliminary findings [180].

4.8. Novel systemic therapies

Systemic (oral) pharmacotherapies for DR/DME are attractive non-invasive alternatives to IVT, potentially treating both eyes simultaneously and conveniently while avoiding risks of endophthalmitis and retinal detachment. However, oral therapy may result in less efficient drug delivery to the target retinal tissue while increasing the risk of systemic side effects as a drug is delivered throughout the body and potentially retained in adipose tissue.

APX3330 (Ocuphire Pharma) is an orally-administered small molecule selective inhibitor of the Ref-1/APE1 protein, a multifunctional enzyme that promotes the growth of tumor endothelial and endothelial progenitor cells via the reduction-oxidation pathway [181]. APE1/Ref-1 activity is thought to play a key role in retinal neovascularization [182], and pre-clinical trials have suggested that local and systemic administration of APX3330 may reduce retinal oxidative stress and inhibit chorioretinal neovascularization [183,184]. A Phase IIb clinical trial (ZETA-1) assessing orally administered APX3330 in patients with NPDR and mild PDR recently failed to meet its primary endpoint of 2-step improvement in DRSS score after 24 weeks of treatment, although data from the trial supports a clinically meaningful reduction in the rate of DR progression [185] and further research is planned.

Other systemic DR pharmacotherapies in development include an oral Rho kinase 1/2 inhibitor (OPL-0401, Valo Health) [186], a guanylate cyclase activator (BAY 1101042, Bayer Pharmaceuticals) [187], an cannabinoid receptor 2 agonist (RG-7774, BioWorld MedTech) [188], and a connexin43 hemichannel blocker (Tonabersat) [189].

6. Conclusion

The pathophysiology of DR involves a complex interplay of diverse biochemical and molecular signaling pathways, contributing to the onset and progression of blinding retinal disease. The multitude of metabolic mechanisms, pathological processes, and associated health conditions contributing to the emergence and advancement of DR present significant opportunities for therapeutic interventions aimed at slowing or reversing the disease process. Such treatments include risk factor modification strategies, retinal photocoagulation, targeted pharmacotherapies, and ultimately surgical intervention for severe, vision-threatening complications.

Recent years have seen a surge in innovation and research into novel therapies for treating diabetic eye disease. Most prominently, advances in pharmacotherapeutics have resulted in the development of promising intravitreal, suprachoroidal, topical, and oral therapies, as well as novel intraocular implant and reservoir systems to increase the durability of existing pharmacotherapies. In addition to targeting VEGF molecules, these novel therapeutics disrupt a broad range of mechanisms implicated in DR pathogenesis, from RTK inhibition to gene therapy, offering the potential for synergistic or adjunctive treatment. These developments offer hope for improved clinical outcomes and quality of life among patients with DR. However, sustained progress in the field remains necessary to fulfill the unmet need for safe, durable, and convenient long-term therapy to prevent blinding diabetic eye disease.

7. Expert opinion

DR represents a major cause of vision loss worldwide, especially among the working-age population. With the rising global prevalence of DM, the incidence of blinding diabetic eye disease is expected to increase proportionally. The clinical features of DR are useful biomarkers of disease severity, forming the basis of the DRSS grading system to assess disease progression and guide management. The severity of retinopathy and the presence of DME determine the therapeutic approach to DR, which includes systemic risk factor modification, retinal photocoagulation, pharmacotherapy, and vitreoretinal surgery.

Modification of systemic risk factors, particularly BG and BP, is essential for the successful management of diabetic eye disease. Ample evidence has demonstrated the importance of early, tight control of BG and BP to prevent development and progression of DR. In mild NPDR, control of BG and BP represents the mainstay of treatment, commonly targeting hemoglobin A1c ≤ 7%. Educating patients about the serious risks of vision loss and emphasizing the importance of risk factor modification is crucial during this stage.

As DR progresses, targeted intervention becomes necessary to prevent vision loss. In the advanced stages of DR, neovascularization defines progression to vision-threatening PDR. PRP is the most effective therapy at this stage, significantly reducing the risk of severe vision loss. Patients with severe NPDR may also benefit from PRP, although it is common practice to defer destructive photocoagulation in these asymptomatic patients. Following development of VH, poor funduscopic visualization may preclude PRP, and early pars plana vitrectomy should be considered; the benefit of anti-VEGF therapy for VH has not been clearly established [116]. PRP may also help stabilize extra-macular TRD, while vitrectomy is necessary for TRD acutely threatening the macular center.

It has additionally been suggested that combined PRP and anti-VEGF IVT may lead to superior initial outcomes in PDR [190], although evidence supporting the long-term efficacy of combination therapy is lacking. There is also some evidence to suggest non-inferiority of anti-VEGF monotherapy for PDR compared to PRP [114,191,192]. However, patients treated with anti-VEGF monotherapy who are lost to follow up may exhibit worse outcomes compared to those treated with PRP alone [193]. Caution must therefore be taken before employing anti-VEGF monotherapy in PDR, and patients must be prepared to adhere to consistent follow up.

DME, the most common vision-threatening complication of DR, may accompany any stage of disease. Focal macular photocoagulation is highly effective in the treatment of CSME and reduces risk of moderate vision loss. However, macular photocoagulation destroys retinal tissue, and may itself cause iatrogenic vision loss. Since the advent of anti-VEGF IVT, numerous large-scale RCTs have established the superior efficacy of anti-VEGF IVT over laser monotherapy for CSME. Anti-VEGF IVT monotherapy has therefore replaced photocoagulation as the first-line standard of care for the treatment of DME, and macular photocoagulation should be reserved as adjunctive therapy for refractory CSME due to its higher risk profile. Best corrected visual acuity worse than 20/32 due to CSME is a reasonable indication for initiating anti-VEGF IVT. In eyes with baseline BCVA better than 20/50, the DRCR.net Protocol T study suggests equivalent efficacy of bevacizumab, ranibizumab, and aflibercept IVT; in eyes 20/50 or worse, aflibercept has been associated with superior visual outcomes compared to bevacizumab at 2 years [103,122]. However, a subsequent DRCR.net trial demonstrated no significant difference in visual outcomes over a two-year period between aflibercept monotherapy versus treatment with bevacizumab with a switch to aflibercept in the case of suboptimal response [194].

Compared to anti-VEGF IVT, corticosteroid IVT may be associated with a higher risk of ocular hypertension and cataract formation. Therefore, corticosteroid IVT has more recently been employed as second-line therapy in phakic patients with DME, except in resource-limited settings without access to anti-VEGF agents. In such practice settings, IV-TA is sometimes combined with macular photocoagulation to maintain long-term therapeutic efficacy, but further study is required. Sustained-release corticosteroid implants also increase durability and may be especially helpful in pseudophakic patients and patients with DME refractory to anti-VEGF IVT.

Anti-VEGF IVT has important limitations. Most significantly, current anti-VEGF agents require recurrent, monthly dosing regimens, increasing the cumulative risk of complications such as endophthalmitis or retinal detachment. Furthermore, monthly dosing can be logistically and financially burdensome for patients, contributing to inconsistent follow up and risk of relapse. Notably, over 40% of eyes treated with anti-VEGF IVT for CSME may require adjuvant focal macular photocoagulation for recalcitrant disease [103,122]. Successful management of DME, therefore, requires a personalized approach with IVT, photocoagulation, or both. The chosen therapeutic strategy must consider clinical setting, resource availability, follow-up reliability, and response to treatment.

Novel intravitreal drugs targeting VEGF, VEGFR receptors, angiopoietins, and integrin heterodimers may provide the opportunity to treat diabetic eye disease more effectively by targeting multiple disease pathways. For example, in the treatment of DME, dual-pathway inhibition of Ang-2 and VEGF by faricimab has demonstrated improved durability, after monthly loading doses, over on-label bimonthly dosing of aflibercept, after monthly loading doses. Other innovative strategies include surgically implanted reservoirs and port delivery systems to provide sustained release drug and decrease treatment burden. However, surgical device implantation is associated with higher rates of endophthalmitis, vitreous hemorrhage, and other adverse events such as device dislodgement. Gene therapy biofactory approaches (which lead to local production of anti-angiogenic proteins) have emerged as another intriguing avenue for overcoming the current limitations of frequent administration and transient therapeutic effects in the treatment of DR and DME. Other novel drug delivery methods, such as eye drops and oral agents, may offer the opportunity for potentially safer, non-invasive treatment of diabetic eye disease, though the efficacy of these therapies remains unproven.

In summary, recent therapeutic advances continue to improve our ability to manage diabetic eye disease and prevent vision-threatening complications of DR and DME. Anti-VEGF IVT has now supplanted macular photocoagulation as the first-line therapy for DME; while PRP monotherapy remains the first-line standard of care for PDR, there is increasing use of intravitreal anti-VEGF agents, often in combination with PRP.

However, despite the success of these therapies, there remains an unmet need for safe, effective, and durable treatment modalities for both DME and PDR. There is also a need for low-risk, long-acting agents that can effectively halt or reverse disease progression during the early, asymptomatic stages of NPDR, prior to the development of PDR or DME. As the prevalence of DM continues to increase worldwide, sustained progress in this field will be necessary to fulfill the need for safe, durable, and convenient interventional strategies to prevent and treat blinding diabetic eye disease.

Article highlights.

Diabetic retinopathy is among the most common complications of diabetes mellitus, and a leading cause of blindness worldwide.

The management of diabetic retinopathy and its complications consists of four major strategies: modification of systemic risk factors, retinal photocoagulation, targeted pharmacotherapy, and vitrectomy.

In recent years, intravitreal anti-VEGF therapies such as bevacizumab, ranibizumab, and aflibercept have largely replaced destructive macular photocoagulation as first-line therapy for diabetic macular edema (DME).

While pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) remains first-line standard of care for treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), there is increasing use of intravitreal anti-VEGF agents, often in combination with PRP.

Treatment of non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, prior to the development of PDR or even DME, remains a high priority, and while intravitreal anti-VEGF therapies have been FDA-approved, they suffer from limited therapeutic durability and require strict adherence to serial treatment sessions in order to achieve disease remission.

Therapies to potentially improve the safety, efficacy, and/or durability of targeted treatment for NPDR are in clinical trials and include receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EYP-1901, OTX-TKI), angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway inhibitors (faricimab), integrin pathway inhibitors (topical OTT166), gene therapy “biofactory” approaches (RGX-314), and novel systemic therapies (oral APX3330).

Funding

This work is supported by funding from National Eye Institute grant numbers R01 EY027779 and R01 EY032080 to AB and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB) to the Department of Ophthalmology, Indiana University.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

T Ciulla reports employment by, and holds equity in, Clearside Biomedical. A Bhatwadekar is an ad hoc pharmacist at CVS Health/Aetna and the manuscript contents do not reflect that of CVS Health/Aetna. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- [1].International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed [Internet]. Brussels, Belgium; 2021. [cited 2022 Oct 19]. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yau JWY, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. Global Prevalence and Major Risk Factors of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:556–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fong DS, Aiello L, Gardner TW, et al. Retinopathy in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 Suppl 1:S84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Köberlein J, Beifus K, Schaffert C, et al. The economic burden of visual impairment and blindness: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Moshfeghi AA, Lanitis T, Kropat G, et al. Social Cost of Blindness Due to AMD and Diabetic Retinopathy in the United States in 2020. Ophthalmic Surgery, Lasers and Imaging Retina. 2020;51:S6–S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Khoo K, Man REK, Rees G, et al. The relationship between diabetic retinopathy and psychosocial functioning: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:2017–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sharma S, Oliver-Fernandez A, Liu W, et al. The impact of diabetic retinopathy on health-related quality of life. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 2005;16:155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kur J, Newman EA, Chan-Ling T. Cellular and physiological mechanisms underlying blood flow regulation in the retina and choroid in health and disease. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2012;31:377–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hammes H-P, Lin J, Renner O, et al. Pericytes and the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes. 2002;51:3107–3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Roy S, Kim D. Retinal capillary basement membrane thickening: Role in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2021;82:100903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lim LS, Wong TY. Lipids and diabetic retinopathy. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2012;12:93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tang J, Kern TS. Inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2011;30:343–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Caldwell RB, Bartoli M, Behzadian MA, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2003;19:442–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Whitehead M, Osborne A, Widdowson PS, et al. Angiopoietins in Diabetic Retinopathy: Current Understanding and Therapeutic Potential. Journal of Diabetes Research. 2019;2019:e5140521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Girach A, Lund-Andersen H. Diabetic macular oedema: a clinical overview. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2007;61:88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Grading Diabetic Retinopathy from Stereoscopic Color Fundus Photographs—An Extension of the Modified Airlie House Classification: ETDRS Report Number 10. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:786–806. ** ETDRS study paper describing the DRSS classification system of diabetic retinopathy.

- [17].Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study research group. Photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study report number 1. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study research group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103:1796–1806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Silva PS, Cavallerano JD, Haddad NMN, et al. Peripheral Lesions Identified on Ultrawide Field Imaging Predict Increased Risk of Diabetic Retinopathy Progression over 4 Years. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:949–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Zhang J, Strauss EC. Sensitive Detection of Therapeutic Efficacy with the ETDRS Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:4385–4393. * Validation of a 2- or 3-step change in DRSS score as a signifier of clinically significant change in disease severity

- [20].Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL, Klein RE, et al. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1677–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). The Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The Effect of Intensive Treatment of Diabetes on the Development and Progression of Long-Term Complications in Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group. Effects of Intensive Glucose Lowering in Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:2545–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ismail-Beigi F, Craven T, Banerji MA, et al. Effect of intensive treatment of hyperglycaemia on microvascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an analysis of the ACCORD randomised trial. The Lancet. 2010;376:419–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Martin CL, Trapani VR, Backlund J- YC, et al. Physical Function in Middle-aged and Older Adults With Type 1 Diabetes: Long-term Follow-up of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:2037–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nathan DM. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study at 30 Years: Overview. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ipp E, Kumar M. A Clinical Conundrum: Intensifying Glycemic Control in the Presence of Advanced Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:2192–2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Azad N, Agrawal L, Bahn G, et al. Eye Outcomes in Veteran Affairs Diabetes Trial (VADT) After 17 Years. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:2397–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].The ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Intensive Blood Glucose Control and Vascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wong T, Mitchell P. The eye in hypertension. The Lancet. 2007;369:425–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Aroca PR, Salvat M, Fernández J, et al. Risk factors for diffuse and focal macular edema. J Diabetes Complications. 2004;18:211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Vitale S, Maguire MG, Murphy RP, et al. Clinically significant macular edema in type I diabetes. Incidence and risk factors. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1170–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Do DV, Wang X, Vedula SS, et al. Blood pressure control for diabetic retinopathy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2015. [cited 2022 Dec 24]; Available from: 10.1002/14651858.CD006127.pub2/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [34].Assmann G, Schulte H. The Prospective Cardiovascular Münster (PROCAM) study: Prevalence of hyperlipidemia in persons with hypertension and/or diabetes mellitus and the relationship to coronary heart disease. American Heart Journal. 1988;116:1713–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chou Y, Ma J, Su X, et al. Emerging insights into the relationship between hyperlipidemia and the risk of diabetic retinopathy. Lipids Health Dis. 2020;19:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].ACCORD Study Group and ACCORD Eye Study Group. Effects of Medical Therapies on Retinopathy Progression in Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:233–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shi R, Zhao L, Wang F, et al. Effects of lipid-lowering agents on diabetic retinopathy: a Meta-analysis and systematic review. Int J Ophthalmol. 2018;11:287–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Keech A, Mitchell P, Summanen P, et al. Effect of fenofibrate on the need for laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy (FIELD study): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2007;370:1687–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Meer E, Bavinger JC, Yu Y, et al. Association of Fenofibrate Use and the Risk of Progression to Vision-Threatening Diabetic Retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2022;140:529–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Frank RN. Use of Fenofibrate in the Management of Diabetic Retinopathy—Large Population Analyses. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2022;140:533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sramek C, Paulus Y, Nomoto H, et al. Dynamics of retinal photocoagulation and rupture. J Biomed Opt. 2009;14:034007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Stefánsson E The therapeutic effects of retinal laser treatment and vitrectomy. A theory based on oxygen and vascular physiology. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2001;79:435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Everett LA, Paulus YM. Laser Therapy in the Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Macular Edema. Curr Diab Rep. 2021;21:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].The Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Photocoagulation Treatment of Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: Clinical Application of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DRS) Findings, DRS Report Number 8. Ophthalmology. 1981;88:583–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].The Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Techniques For Scatter And Local Photocoagulation Treatment Of Diabetic Retinopathy: Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Report No. 3. International Ophthalmology Clinics. 1987;27:254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chew EY, Ferris FL, Csaky KG, et al. The long-term effects of laser photocoagulation treatment in patients with diabetic retinopathy: The early treatment diabetic retinopathy follow-up study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1683–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Reddy SV, Husain D. Panretinal Photocoagulation: A Review of Complications. Seminars in Ophthalmology. 2018;33:83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].The Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Treatment Techniques and Clinical Guidelines for Photocoagulation of Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:761–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema: Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study report no. 4. International ophthalmology clinics. 1987;27:265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Herold TR, Langer J, Vounotrypidis E, et al. 3-year-data of combined navigated laser photocoagulation (Navilas) and intravitreal ranibizumab compared to ranibizumab monotherapy in DME patients. PLOS ONE. 2018;13:e0202483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mitchell P, Bandello F, Schmidt-Erfurth U, et al. The RESTORE Study: Ranibizumab Monotherapy or Combined with Laser versus Laser Monotherapy for Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Payne JF, Wykoff CC, Clark WL, et al. Long-term outcomes of treat-and-extend ranibizumab with and without navigated laser for diabetic macular oedema: TREX-DME 3-year results. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2021;105:253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Prünte C, Fajnkuchen F, Mahmood S, et al. Ranibizumab 0.5 mg treat-and-extend regimen for diabetic macular oedema: the RETAIN study. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2016;100:787–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Zur D, Loewenstein A. Should we still be performing macular laser for non-centre involving diabetic macular oedema? Yes. Eye. 2022;36:483–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Mueller I, Talks JS. Should we still be performing macular laser for non-centre involving diabetic macular oedema? No. Eye. 2022;36:485–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Scholz P, Altay L, Fauser S. A Review of Subthreshold Micropulse Laser for Treatment of Macular Disorders. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1528–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Silva PS, Sun JK, Aiello LP. Role of Steroids in the Management of Diabetic Macular Edema and Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Seminars in Ophthalmology. 2009;24:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Lattanzio R, Cicinelli MV, Bandello F. Intravitreal Steroids in Diabetic Macular Edema. In: Bandello F, Zarbin MA, Lattanzio R, et al. , editors. Developments in Ophthalmology [Internet]. S. Karger AG; 2017. [cited 2023 Jan 7]. p. 78–90. Available from: https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/459691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gillies MC, McAllister IL, Zhu M, et al. Intravitreal Triamcinolone Prior to Laser Treatment of Diabetic Macular Edema: 24-Month Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:866–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gillies MC, Sutter FKP, Simpson JM, et al. Intravitreal triamcinolone for refractory diabetic macular edema - Two-year results of a double-masked, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1533–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Grover DA, Li T, Chong CC. Intravitreal steroids for macular edema in diabetes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2008. [cited 2023 Jan 7]; Available from: 10.1002/14651858.CD005656.pub2/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [62].Jeon S, Lee WK. EFFECT OF INTRAVITREAL TRIAMCINOLONE IN DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA UNRESPONSIVE TO INTRAVITREAL BEVACIZUMAB. RETINA. 2014;34:1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Larsson J, Kifley A, Zhu M, et al. Rapid reduction of hard exudates in eyes with diabetic retinopathy after intravitreal triamcinolone: data from a randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2009;87:275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Maia OO, Takahashi BS, Costa RA, et al. Combined Laser and Intravitreal Triamcinolone for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy and Macular Edema: One-year Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2009;147:291–297.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Yilmaz T, Weaver CD, Gallagher MJ, et al. Intravitreal Triamcinolone Acetonide Injection for Treatment of Refractory Diabetic Macular Edema: A Systematic Review. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:902–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Lam DSC, Chan CKM, Mohamed S, et al. Intravitreal Triamcinolone plus Sequential Grid Laser versus Triamcinolone or Laser Alone for Treating Diabetic Macular Edema: Six-Month Outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:2162–2167.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kang SW, Sa H-S, Cho HY, et al. Macular Grid Photocoagulation After Intravitreal Triamcinolone Acetonide for Diffuse Diabetic Macular Edema. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2006;124:653–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Elman MJ, Aiello LP, Beck RW, et al. Randomized Trial Evaluating Ranibizumab Plus Prompt or Deferred Laser or Triamcinolone Plus Prompt Laser for Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1064–1077.e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Zein WM, Noureddin BN, Jurdi FA, et al. Panretinal photocoagulation and intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for the management of proliferative diabetic retinopathy with macular edema. Retina. 2006;26:137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Liu L, Wu X, Geng J, et al. IVTA as Adjunctive Treatment to PRP and MPC for PDR and Macular Edema: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Avci R, Kaderli B. Intravitreal triamcinolone injection for chronic diabetic macular oedema with severe hard exudates. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Choi KS, Chung J, Lim SH. Laser Photocoagulation Combined with Intravitreal Triamcinolone Acetonide Injection in Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy with Macular Edema. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2007;21:11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. A Randomized Trial Comparing Intravitreal Triamcinolone Acetonide and Focal/Grid Photocoagulation for Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1447–1459.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Beck RW, Edwards AR, et al. Three-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing focal/grid photocoagulation and intravitreal triamcinolone for diabetic macular edema. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:245–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Jonas JB, Degenring RF, Kreissig I, et al. Intraocular Pressure Elevation After Intravitreal Triamcinolone Acetonide Injection. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:593–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Mishra C, Lalitha P, Rameshkumar G, et al. Incidence of Endophthalmitis after Intravitreal Injections: Risk Factors, Microbiology Profile, and Clinical Outcomes. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2018;26:559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].VanderBeek BL, Bonaffini SG, Ma L. The Association between Intravitreal Steroids and Post-Injection Endophthalmitis Rates. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2311–2315.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Boyer DS, Yoon YH, Belfort R, et al. Three-Year, Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial of Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1904–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Haller JA, Kuppermann BD, Blumenkranz MS, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an intravitreous dexamethasone drug delivery system in patients with diabetic macular edema. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2010;128:289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Callanan DG, Gupta S, Boyer DS, et al. Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant in Combination with Laser Photocoagulation for the Treatment of Diffuse Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1843–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Boyer DS, Faber D, Gupta S, et al. DEXAMETHASONE INTRAVITREAL IMPLANT FOR TREATMENT OF DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA IN VITRECTOMIZED PATIENTS. RETINA. 2011;31:915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Gillies MC, Lim LL, Campain A, et al. A randomized clinical trial of intravitreal bevacizumab versus intravitreal dexamethasone for diabetic macular edema: the BEVORDEX study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:2473–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Iglicki M, Zur D, Busch C, et al. Progression of diabetic retinopathy severity after treatment with dexamethasone implant: a 24-month cohort study the ‘DR-Pro-DEX Study.’ Acta Diabetol. 2018;55:541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Chang-Lin J-E, Attar M, Acheampong AA, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a sustained-release dexamethasone intravitreal implant. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Montes Rodríguez P, Mateo Gabás J, Esteban Floría O, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dexamethasone compared with aflibercept in naïve diabetic macular edema. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 2022;20:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Campochiaro PA, Brown DM, Pearson A, et al. Sustained Delivery Fluocinolone Acetonide Vitreous Inserts Provide Benefit for at Least 3 Years in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2125–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Cunha-Vaz J, Ashton P, Iezzi R, et al. Sustained Delivery Fluocinolone Acetonide Vitreous Implants: Long-Term Benefit in Patients with Chronic Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1892–1903.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Ghasemi Falavarjani K, Nguyen QD. Adverse events and complications associated with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents: a review of literature. Eye (Lond). 2013;27:787–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Apte RS, Chen DS, Ferrara N. VEGF in Signaling and Disease: Beyond Discovery and Development. Cell. 2019;176:1248–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90]. Witmer AN, Vrensen GFJM, Van Noorden CJF, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factors and angiogenesis in eye disease. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2003;22:1–29. * Comprehensive review of the key role of VEGF in proliferative eye disease

- [91].Stitt AW, Curtis TM, Chen M, et al. The progress in understanding and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2016;51:156–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Das A, McGuire PG, Rangasamy S. Diabetic Macular Edema: Pathophysiology and Novel Therapeutic Targets. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1375–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Li AS, Veerappan M, Mittal V, et al. Anti-VEGF agents in the management of diabetic macular edema. Expert Review of Ophthalmology. 2020;15:285–296. [Google Scholar]

- [94].Ehlers JP, Yeh S, Maguire MG, et al. Intravitreal Pharmacotherapies for Diabetic Macular Edema: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2022;129:88–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Chatziralli I, Loewenstein A. Intravitreal Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Agents for the Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy: A Review of the Literature. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Ng EWM, Shima DT, Calias P, et al. Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Ferrara N, Damico L, Shams N, et al. Development of ranibizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antigen binding fragment, as therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2006;26:859–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Nguyen QD, Shah SM, Heier JS, et al. Primary End Point (Six Months) Results of the Ranibizumab for Edema of the mAcula in diabetes (READ-2) study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2175–2181.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Sepah YJ, Sadiq MA, Boyer D, et al. Twenty-four-Month Outcomes of the Ranibizumab for Edema of the Macula in Diabetes - Protocol 3 with High Dose (READ-3) Study. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:2581–2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Massin P, Bandello F, Garweg JG, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Ranibizumab in Diabetic Macular Edema (RESOLVE Study). Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2399–2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Elman MJ, Aiello LP, et al. Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1064–1077.e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Bressler SB, Glassman AR, Almukhtar T, et al. Five-Year Outcomes of Ranibizumab With Prompt or Deferred Laser Versus Laser or Triamcinolone Plus Deferred Ranibizumab for Diabetic Macular Edema. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2016;164:57–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103]. Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al. Aflibercept, Bevacizumab, or Ranibizumab for Diabetic Macular Edema: Two-Year Results from a Comparative Effectiveness Randomized Clinical Trial. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1351–1359. **Landmark DRCR.net Protocol T trial demonstrating the superior efficacy of aflibercept over bevacizumab or ranibizumab in eyes with baseline visual acuity worse than 20/50, and equivalent efficacy among the three drugs in eyes with baseline visula acuity better than 20/50.

- [104].Schmidt-Erfurth U, Lang GE, Holz FG, et al. Three-Year Outcomes of Individualized Ranibizumab Treatment in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema: The RESTORE Extension Study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1045–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Mitchell P, Massin P, Bressler S, et al. Three-year patient-reported visual function outcomes in diabetic macular edema managed with ranibizumab: the RESTORE extension study. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2015;31:1967–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Ishibashi T, Li X, Koh A, et al. The REVEAL Study: Ranibizumab Monotherapy or Combined with Laser versus Laser Monotherapy in Asian Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1402–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]