Key words: Enteric endocrine system, enteric nervous system, gut physiology, intestinal parasites, teleost

Abstract

Most individual fish in wild and farmed populations can be infected with parasites. Fish intestines can harbour protozoans, myxozoans and helminths, which include several species of digeneans, cestodes, nematodes and acanthocephalans. Enteric parasites often induce inflammation of the intestine; the pathogen provokes changes in the host physiology, which will be genetically selected for if they benefit the parasite. The host response to intestinal parasites involves neural, endocrine and immune systems and interaction among these systems is coordinated by hormones, chemokines, cytokines and neurotransmitters including peptides. Intestinal fish parasites have effects on the components of the enteric nervous and endocrine systems; mechanical/chemical changes impair the activity of these systems, including gut motility and digestion. Investigations on the role of the neuroendocrine system in response to fish intestinal parasites are very few. This paper provides immunohistochemical and ultrastructural data on effects of parasites on the enteric nervous system and the enteric endocrine system in several fish–parasite systems. Emphasis is on the occurrence of 21 molecules including cholecystokinin-8, neuropeptide Y, enkephalins, galanin, vasoactive intestinal peptide and serotonin in infected tissues.

Introduction

Parasitism is a close association in which parasites may influence their hosts at several organizational levels (Barber and Wright, 2005). Often these effects of parasites on the hosts increase the parasite's likelihood of transmission (Poulin, 1998). The alimentary canal of fish has been shown to be a favourite place for the growth, establishment and reproduction of enteric parasites (Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021a). Intestinal parasites often induce changes in the morphology of the host tissue that might affect organ physiology (Fairweather, 1997). Inflammation due to fish enteric helminths is well documented (Dezfuli et al., 2000, 2011a, 2011b; Taraschewski, 2000; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021a, 2022) and consists of a complex series of homoeostatic mechanisms involving circulatory, immune, nervous and endocrine systems (Serna-Ducque and Esteban, 2020; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021a). In at least some host–parasite systems, changes in host physiology are caused by parasite action on the fish neuroendocrine system (NES) (Øverli et al., 2001; Herbison, 2017; Helland-Riise et al., 2020).

Several amines, peptides and other molecules permit communication between nervous, endocrine and immune cells, which often produce neuromodulators (O'Dorisio and Panerai, 1990). Some publications have recorded the essential role of the NES in inflammatory processes caused by intestinal parasites in mammals (see Fairweather, 1997). Interestingly, most mammalian enteric neuropeptides also are present in fish and probably act in the same way (Holmgren, 1985). The number of studies concerning the physiological role of neuromodulators of the fish enteric NES is growing (Bosi et al., 2007; Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Takei and Loretz, 2011; Blanco et al., 2017; Ceccotti et al., 2018). The NES controls and regulates intestinal physiology and in fish with enteric parasites this system is challenged with an overload. A recent review by Serna-Duque and Esteban (2020) suggested 3 types of neuroendocrine responses against parasites: fight, protect and escape.

In wild fish, parasitic infections are frequent (Feist and Longshaw, 2008) and in cultured fish parasites and diseases reduce reproductive performance and have a negative impact on feed conversion efficiency, which influences animal welfare (Shinn et al., 2015). Indeed, fish parasites decrease host growth (Hoai, 2020), in some cases provoke mortality (Tavares-Dias and Martins, 2017), some parasites are zoonotic and may challenge food safety (Levsen et al., 2018). The purpose of this investigation was to detect and then compare the occurrence and distribution of putative neuromodulators in the intestine of several fish species infected with parasites.

The gut NES

During digestion, in the lumen of the alimentary canal food is reduced to small nutritive molecules absorbed for the body energy balance and waste is ejected. According to Takei and Loretz (2011) the lumen represents a continuum with the environment, the ‘outside world’, which makes the lumen a gateway for the entrance of pathogens. Fish living in water are continuously challenged with a plethora of micro-organisms, pollutants and parasites. The activities involved in the physiological control of vertebrate gut function, including defence against pathogens, are mediated by the NES (Palmer and Greenwood-Van Meerveld, 2001; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021a) formed by the enteric nervous system (ENS) and the enteric endocrine system (EES) (Takei and Loretz, 2011) (Fig. 1).

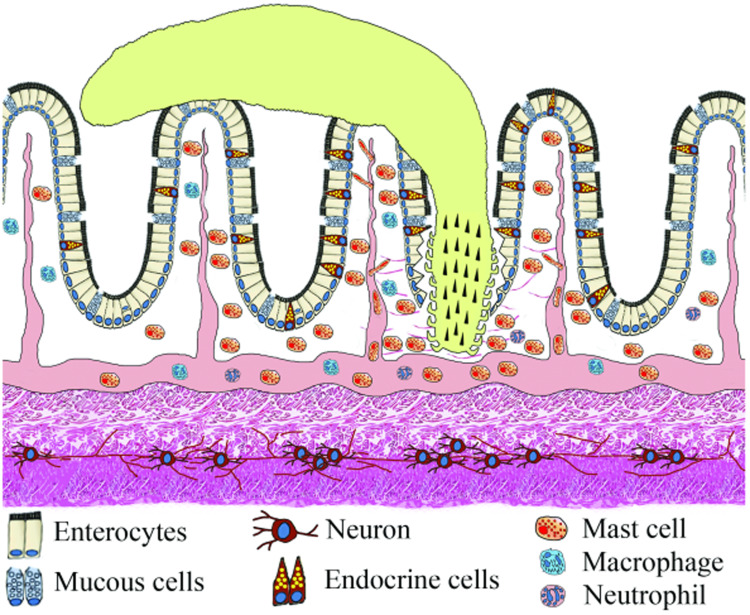

Fig. 1.

Schematic view of the intestinal wall of fish with attached acanthocephalan. The intestinal mucosa is lined by a simple columnar epithelium consisting of typical epithelial cells with a sparse intermingling of mucus cells and ECs. Note the presence of the myenteric plexus with neurons between 2 muscle layers.

In fish, the ENS consists of neurons scattered in the gut wall or aggregated in small groups interconnected with nerve fibres and nerve bundles, named myenteric plexus, running between the inner circular and the outer longitudinal muscle layers (Furness, 2006a; Ceccotti et al., 2018) (Figs 1 and 2A). Fish lack a well-organized submucosal plexus to innervate the mucosa; nevertheless, in some instances the nerve fibres were reported in the tunica propria-submucosa (Ceccotti et al., 2018). The extrinsic autonomic nervous system controls the ENS through the cranial vagus nerve and the spinal splanchnic nerves (Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Blanco et al., 2021). The neurons of the ENS innervate each component of the gut wall (muscle, epithelium, blood vessels and innate immune cells located in the connective layer beneath the epithelium) (Furness, 2006a).

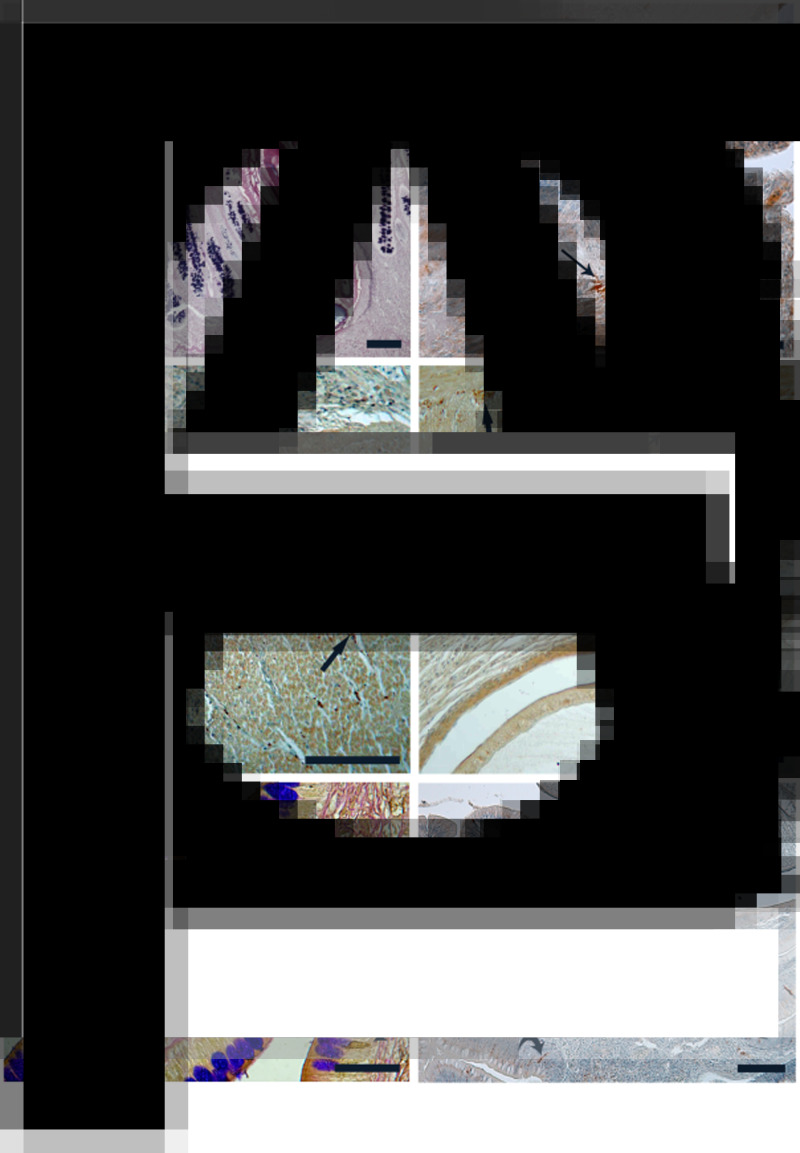

Fig. 2.

Components of the enteric nervous system and EES in several fish–helminth systems. (A) Salmo trutta infected with Pomphorhynchus laevis (out of microscope field), showing neurons of the myenteric plexus (thick arrows) and nerve fibres (thin arrows) immunoreactive to the anti-SP between the inner and outer intestinal muscle layers. The curved arrows indicate ECs in the epithelium. In the tunica propria-submucosa, numerous SP-positive mast cells are evident (arrowheads). CML, LML, circular and longitudinal muscle layer of tunica muscularis; TM, tunica mucosa; TPS, tunica propria-submucosa; scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Oncorhynchus mykiss parasitized with Eubothrium crassum (out of microscope field) showing 2 open-type ECs immunoreactive to anti-CCK8 in the rainbow trout intestinal epithelium; 1 of them is near a mucus cell (asterisk). Note the neuropod (thin arrow) of the cell on the right; scale bar: 10 μm. (C) Esox lucius harbouring Acanthocephalus lucii (out of microscope field), showing 2 closed-type ECs immunoreactive to anti-somatostatin-14 in the gastric epithelium of the pike. The neuropod is evident in the top left EC (thin arrow); scale bar: 20 μm.

The EES is considered the largest endocrine organ in the body (Ahlman and Nilsson, 2001; Blanco et al., 2021). The main components of the EES are the endocrine cells (ECs, Figs 1 and 2B, C), many of which are randomly scattered in the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract and sometimes are in close proximity to nerve fibres and immune cells (Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Stakenborg et al., 2020). There are 2 morphologically distinct types of ECs, ‘open’ and ‘closed’. The first type is a spindle-shaped cell, with its basal region near the basement membrane of the epithelium and the subtle apex exposed to the intestinal lumen (Takei and Loretz, 2011; Kulkarni et al., 2018; Blanco et al., 2021) (Fig. 2B). The closed type EC is also situated near the basal membrane, but does not reach the epithelial apex (Takei and Loretz, 2011; Kulkarni et al., 2018; Blanco et al., 2021) (Fig. 2C). The ECs, also called ‘paraneurons’ (Fujita and Kobayashi, 1977; Day and Salzet, 2002; Takei and Loretz, 2011), pick up luminal/tissue stimuli with their membrane receptors and release specific chemical messengers from an axonal-like process at their basolateral membrane, called the ‘neuropod’ (Takei and Loretz, 2011; Latorre et al., 2016; Kulkarni et al., 2018; Bosi et al., 2020) (Fig. 2B and C). The proximity of the ECs to mucous cells and mast cells might suggest their involvement in fish immune responses to the pathogens (Bosi et al., 2015; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2017, 2021a) (Fig. 3) and their connection with sensory neurons of the gut plexuses are consistent with the role of the ECs in direct transmission of information to the brain (Kaelberer et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2021).

Fig. 3.

Close relationship between ECs and epithelial components of the innate defence against parasites. Both images are from Silurus glanis intestine infected with the cestode Glanitaenia osculata (not shown). (A) ECs (curved arrows) immunoreactive to anti-serotonin close to the epithelial mucus cells (thin arrows). Immunohistochemistry counterstained with the Alcian blue/periodic acid Schiff method (AB/PAS). The AB/PAS stain reveals mucus cells in blue, magenta or violet depending on their content of acidic, neutral or mixed (acidic + neutral) mucins; scale bar: 50 μm. (B) ECs (curved arrows) immunoreactive to anti-met-enkephalin near intraepithelial mast cells (thick arrows). Mast cells are magenta due to periodic acid Schiff. Immunohistochemistry counterstained with the AB/PAS stain; scale bar: 50 μm.

The ENS–EES can function independently from the brain and spinal cord and are able to direct several physiological functions of the gastrointestinal tract without receiving commands from the central nervous system (Furness, 2006a). The ECs detect several substances, each of them inducing an intracellular signal that leads to the release of a specific signal molecule, mainly a peptide (Sternini et al., 2008; Blanco et al., 2021). The released signal molecule can act locally on the neighbouring tissue components, or enter the circulatory system to reach more distant cells (Blanco et al., 2021).

The interactions between components of the ENS–EES are mediated by several signal molecules produced by them, and some other molecules are secreted by cells of the innate immune system (Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Hernández-Bello et al., 2010; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021a). In the past, ECs were classified based on the nature of the molecular signal they produce; recently molecular biology assays revealed they are more complex than previously recognized and are able to express and secrete different hormones and neurotransmitters in relation to the gut regions where they are located (Ye and Rawls, 2021).

The primary stimulus for the physiological activity of the gut is the ingestion of food, and its progression along the alimentary canal stimulates the ECs (Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Takei and Loretz, 2011). The sequential contraction and relaxation of the smooth muscle layer ensures mixture and the progressive movement of the digesta along the alimentary canal; the secretive/absorptive activity of the gut mucosa, pancreas and liver reduces the size of the food particles and macromolecules to small nutritional molecules that can be absorbed (Holmgren and Olsson, 2009). Several authors have reviewed the molecules involved in fish physiological activity (Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Volkoff et al., 2009; Takei and Loretz, 2011; Volkoff, 2016; Serna-Duque and Esteban, 2020; Blanco et al., 2021), thus, in the following sections only a brief description of signal molecules and their main functions will be provided.

The NES control of gut motility

The main excitatory neurotransmitter in the fish gut is acetylcholine (Szabó et al., 1991; Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Ceccotti et al., 2018). Several other peptides like tachykinin substance P (SP) and galanin function as co-transmitters in cholinergic gut neurons (Furness, 2000; Bosi et al., 2004, 2006, 2007; Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Ceccotti et al., 2018). Seemingly, the contraction of the smooth muscle cells is regulated by the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and the amine serotonin (Shahbazi et al., 1998; Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Ceccotti et al., 2018). It has been mentioned that the largest neuronal population in the myenteric plexus of the fish gut is formed by serotonergic neurons (Olsson et al., 2008b; Ceccotti et al., 2018). Other molecules that function as excitatory neurotransmitters in the gut neurons of fish are well known. For example, the peptide ghrelin, which signals satiety, is secreted by endocrine epithelial cells of the stomach and modulates the contraction of smooth muscle cells (Olsson et al., 2008a; Holmgren and Olsson, 2009).

In the fish gut, relaxation of smooth muscle cells is mainly induced by vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), pituitary adenylate-cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) and by nitric oxide gas (Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Takei and Loretz, 2011; Ceccotti et al., 2018). Nitric oxide is not stored in the cell but is synthesized on demand by activation of a specific enzyme, neuronal-nitric oxide synthase (n-NOS) (Furness, 2006b).

Some signal molecules modulate gut muscle peristalsis: their release alone or in combination with other substances can induce contraction or relaxation of the organ. In addition to its excitatory function, the peptide CGRP can inhibit gut muscle motility (Shahbazi et al., 1998; Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Ceccotti et al., 2018). The peptide bombesin can stimulate stomach smooth muscle cells, although it was considered as a weak inhibitor of muscle contraction in some fish species (Holmgren and Jönsson, 1988; Holmgren and Olsson, 2009). The main function of somatostatin is the inhibition of gastric acid secretion (Chu and Schubert, 2013; Bohórquez and Liddle, 2015). Notwithstanding, the inhibition of cholinergic neurons of the smooth muscle cells by somatostatin has also been documented in fish stomach (Grove and Holmgren, 1992a, 1992b; Holmgren and Olsson, 2009).

The NES control of alimentary physiology

In vertebrates, specific brain regions regulate feeding behaviour under the influence of molecular signals, produced by the brain itself or by the gut and its annexes (Volkoff, 2016). The feeding activity is inhibited or stimulated in the presence of molecular signals released by neurons of the hypothalamus as well as neurons of ENS, and/or ECs of EES (Volkoff, 2016).

Several signal molecules are involved in the control and regulation of the gastrointestinal status and consequently of the fish feeding behaviour (Le Bail and Boeuf, 1997; Takei and Loretz, 2011). The signal molecules with orexigenic action are ghrelin, galanin, neuropeptide Y (NPY) and β-endorphin. Conversely, gastrin/cholecystokinin8 (CCK8), gastrin releasing peptide (GRP)/bombesin, PACAP, VIP, CGRP, tachykinins and serotonin are considered anorectic signal molecules (Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Takei and Loretz, 2011; Volkoff, 2016).

When digesta enters the fish proximal intestine, the local release of glucagon inhibits gastric acid secretion and acts as a short-term signal for the ingestion of food (Olsson and Holmgren, 2001; Takei and Loretz, 2011). The ECs secrete CCK8, which induces gall bladder contraction and the entrance of bile in the intestinal lumen (Volkoff, 2016). Moreover, CCK8 stimulates the synthesis and secretion of pancreatic enzymes (Rønnestad et al., 2007; Takei and Loretz, 2011; Volkoff, 2016; Blanco et al., 2021).

Intra-cerebroventricular or -peritoneal injections of bombesin, CCK8, PACAP and VIP inhibit food intake in fish (Himick and Peter, 1994a, 1994b; Matsuda et al., 2005; Volkoff et al., 2009). The effects of the different neuroendocrine molecules on fish feeding behaviour are several and variegated; many molecules are involved in food intake or prohibit food intake. For instance, CCK8 stimulates cholinergic neurons to reduce gastric emptying (Olsson et al., 1999) and simultaneously stimulates the gallbladder to release bile (Aldman and Holmgren, 1995). Both CCK8 and CGRP are synthesized by neurons and ECs and are involved in several functions like control of peristalsis, vasodilation and regulation of food intake concurrently with other signal molecules (Shahbazi et al., 1998; Martínez-Álvarez et al., 2009).

With reference to orexigenic signal molecules, galanin injected in the fish brain influenced the feeding behaviour of tench, Tinca tinca, and goldfish, Carassius auratus (Guijarro et al., 1999; Volkoff and Peter, 2001; Volkoff, 2016). Another orexigenic peptide, NPY is expressed in the fish brain and intestine and its increase induces feeding activity (Volkoff, 2016). Ghrelin treatment can negatively affect food uptake in the rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, and the Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar. Conversely, the same molecule increased foraging activity in brown trout, Salmo trutta. Thus, the function of ghrelin in fish feeding behaviour seems to be species-specific (Volkoff, 2016). All of the studies on molecules involved in fish feeding activity were conducted on uninfected fish, or did not specify whether the fish were infected. To better understand host–parasite interactions, more studies on both uninfected and infected fish are needed.

The NES control of intestinal immunity

In fish, the amine serotonin is synthesized by neurons, ECs and immune cells, primarily by mast cells (Bosi et al., 2005a, 2005b, 2015; Dezfuli et al., 2011a; Ceccotti et al., 2018). The tachykinin SP is a pro-inflammatory peptide, secreted by mast cells (Powell et al., 1991; Serna-Duque and Esteban, 2020). Moreover, the endogenous opioids leu- and met-enkephalin are reported in the intestinal mast cells of diverse fish species (Bosi et al., 2005b; Dezfuli et al., 2009; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2018b). In the gut as in other organs, mast cells are strategically located at perivascular sites and very close to enteric nervous fibres (Dezfuli et al., 2015; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2016; Serna-Duque and Esteban, 2020).

Serotonin, SP and enkephalins are common signal molecules of nervous, endocrine and immune systems, respectively (Bosi et al., 2005b; Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Dezfuli et al., 2012; Gabanyi et al., 2016; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2018b). The immunomodulatory role of serotonin and other pro-inflammatory molecules in inflammation mechanisms was reported in Wang et al. (2018) and Serna-Duque and Esteban (2020). An update on the involvement of the NES in the fish immune response to parasites is presented in the recent review by Sayyaf Dezfuli et al. (2021a).

Effects of parasites on the gut NES of fish

Effects of intracellular parasites

Very limited investigations have been done on the effects of intracellular parasites on the NES of fish gut. Pioneering studies were done on the turbot Scophthalmus maximus harbouring the myxozoan Enteromyxum scophthalmi (Bermúdez et al., 2007; Losada et al., 2014; Robledo et al., 2014) and on the channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus, infected with the bacterium Edwardsiella ictaluri (Li et al., 2012). In the fish gut, E. scophthalmi penetrates into the epithelial cells where it grows and proliferates, damaging cells and invading the epithelium of other digestive canal regions (Redondo et al., 2004; Bermudez et al., 2007). This myxozoan provokes a severe enteritis, epithelial cell desquamation and high fish mortality (Branson et al., 1999).

The effects of E. scophthalmi on the ENS–EES of the turbot are summarized in Table 1. In the parasitized turbot, a high number of ECs immunoreactive to the antibodies anti-CCK8, somatostatin, serotonin, SP, leu- and met-enkephalin were noticed in comparison with the uninfected fish (Bermúdez et al., 2007; Losada et al., 2014). In the same host–parasite system, Robledo et al. (2014) found that the gene expressions for gastrin/CCK-like peptide, CCK2-receptor, gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) and galanin receptor 1 are all downregulated in turbot harbouring the myxozoan. Concerning bombesin, glucagon and VIP, a reduced number of neuroendocrine components was observed in the turbot infected with the myxozoan (Bermúdez et al., 2007; Losada et al., 2014). Moreover, Bermúdez et al. (2007) showed an increase in the number of macrophages immunoreactive to the antibodies anti-SP and -leu-enkephalin in the gut regions that are heavily parasitized with E. scophthalmi.

Table 1.

Effect of intestinal intracellular parasites’ occurrence on the NES of fish

| Host–parasite system | Scophthalmus maximus | Ictalurus punctatus | Paralichthys olivaceus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuro-hormones | Enteromyxum scophthalmi | Edwardsiella ictaluri | Edwardsiella tarda |

| Bombesin | Ns, ECs | ||

| CCK8 | ECs | ||

| Gastrin/CCK | RNA-seq | ||

| CCK-2rec | RNA-seq | ||

| GIP | RNA-seq | ||

| Galanin receptor 1 | RNA-seq | ||

| Ghrelin | RNA-seq | ||

| Glucagon | ECs | ||

| PYY | RNA-seq | ||

| Somatostatin | ECs | RNA-seq | |

| Leu-enkephalin | ECs, MAs | ||

| Met-enkephalin | |||

| SP | Ns, MCs | ||

| VIP | Ns, ECs | ||

| PACAP | RNA-seq | ||

| CGRP | RNA-seq | ||

| Serotonin | Ns, ECs |

Source: Bermúdez et al. (2007); Li et al. (2012); Nam et al. (2013); Losada et al. (2014); Robledo et al. (2014).

Ns, neurons; ECs, endocrine cells; MAs, macrophages; MCs, mast cells.

The normal-reversal acronym indicates an increase-decrease of immune-positive cells or gene expression, respectively.

The Gram-negative bacterium E. ictaluri is an aetiologic agent of enteric septicaemia of the channel catfish; the pathogen is considered responsible for high fish mortality (Li et al., 2012). Catfish experimentally infected with E. ictaluri showed a changed transcriptional response, which increased from 693 genes at 3 h to 1035 genes at 3 days post-infection (Li et al., 2012). Among the detected genes, only 3 were related to peptides of the NES, namely ghrelin, peptide YY (PYY) and somatostatin; they were downregulated in the catfish harbouring bacteria (Li et al., 2012). Nonetheless, high expression of a species-specific variant of PACAP (PACAP-related peptide, PRP) was detected in the intestine and pyloric caeca of the olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus infected with Edwardsiella tarda (Nam et al., 2013). The experimental evidences suggested a regulatory role of PRP in the intestinal immune system of the olive flounder infected with the bacterium (Nam et al., 2013).

Effects of trematodes

Recent insight into histopathology due to different species of fish trematodes (flukes) was presented in Sayyaf Dezfuli et al. (2021a). Most trematodes are not a serious threat to fish health; however, some species that occur in non-gut sites are more pathogenic. Mass mortality in cultured marine species leading to significant socio-economic losses was attributed to flukes (Power et al., 2020). Most intestinal adult flukes attach to the mucosa by sucker(s) (Fig. 4A) and feed mainly on epithelial cells (Jennings, 1968). The parasites destroy the mucosal epithelium covering the intestinal folds, causing local inflammation and cell necrosis (Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021a).

Fig. 4.

Fish infected with intestinal digeneans. (A) The digenean Helicometra fasciata (arrow) attached with its sucker (arrowheads) to an intestinal fold (curved arrow) of the European eel. Azan Mallory stained; scale bar: 100 μm. (B) ECs (curved arrows) immunoreactive to anti-met-enkephalin in the intestinal epithelium of the Squalius cephalus infected with a digenean (d); scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Chelon saliens parasitized with Dicrogaster contractus (out of microscope field). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide-immunoreactive ECs (curved arrows), and neurons and nerve fibres (thin arrows) in the infected mullet intestine; scale bar: 100 μm.

There are several studies on the histopathological effects of trematode infection in fish intestine (Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2018a, 2021a; Dumbo and Avenant-Oldewage, 2019). In comparison with other helminth taxa, such as Acanthocephala, the shallow attachment of trematodes to the intestinal mucosa (Fig. 4B) did not seem to induce massive engagement of the host EES. Similarly, neurons and nerve fibres of the myenteric plexus immunoreactive to the anti-PACAP did not show changes in number between uninfected mullet, Chelon saliens, and conspecifics infected with the intestinal trematode Dicrogaster contractus (this study) (Fig. 4C).

Effects of Cestoda

The class Cestoda includes less than 5000 species of intestinal parasites of vertebrates. The alteration of fish feeding behaviour by cestodes has been documented in the stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus, the second intermediate host for the tapeworm Schistocephalus solidus (Barber and Huntingford, 1995; Ranta, 1995). The presence of S. solidus reduces the level of monoamines in the brain, making the fish more active in feeding (Øverli et al., 2001). Furthermore, this cestode manipulates host behaviour via the immune and neuroendocrine axis, which aids transmission to the definitive host, fish-eating birds (Scharsack et al., 2013).

The effects of cestodes on the ENS–EES of the fish gut have been studied in diverse host–parasite systems (Table 2). The damage to the gut mucosa is mainly due to specialized structures of the scolex including the bothria and suckers. In the brown trout infected with Cyathocephalus truncatus, the most infected gut region was the tract where the bile duct opens (Dezfuli et al., 2000), probably because worm development and growth are stimulated by the bile components (Smyth, 1969). Most cestode species do not cause severe damage to the intestinal wall because they do not penetrate deeply into the gut wall (Dezfuli et al., 2010) (Fig. 5A). Nevertheless, in some exceptions (e.g. Monobothrium wageneri in T. tinca) worms reach the muscle layer, destroying the intestinal wall architecture and provoking an intense inflammatory response (see Dezfuli et al., 2011b).

Table 2.

Results of the effects of intestinal cestodes on the NES of fish

| Host–parasite system | Salmo trutta | Oncorhynchus mykiss | Coregonus lavaretus | Silurus glanis | Anguilla anguilla |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuro-hormones | Cyathocephalus truncates | Eubothrium crassum | Dibothriocephalus dendriticus | Glanitaenia osculata | Proteocephalus macrocephalus |

| Bombesin | ECs | ECs | Ns, ECs | ||

| CCK8 | ECs | ECs | |||

| Gastrin | ECs | ECs | |||

| GRP | ECs | ||||

| Glucagon | ECs | ECs | |||

| NPY | – | ||||

| Secretin | ECs | ||||

| Met-enkephalin | Ns, ECs, MCs | ECs | |||

| Galanin | Ns | ECs | |||

| SP | Ns, ECs, MCs | Ns, MCs | |||

| NOS | – | Nsa | |||

| VIP | Ns | – | |||

| PACAP | Nsa | ||||

| CGRP | ECs | – | |||

| Serotonin | Ns, ECs | Ns, MCs | ECs |

Source: Dezfuli et al. (2000, 2003, 2007a, 2007b); Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., (2017); Bosi et al. (2005a); unpublished data of this study.

Ns, neurons; ECs, endocrine cells; MCs, mast cells.

–, not detected.

The normal-reversal acronym indicates an increase-decrease of immune-positive cells, respectively.

This study.

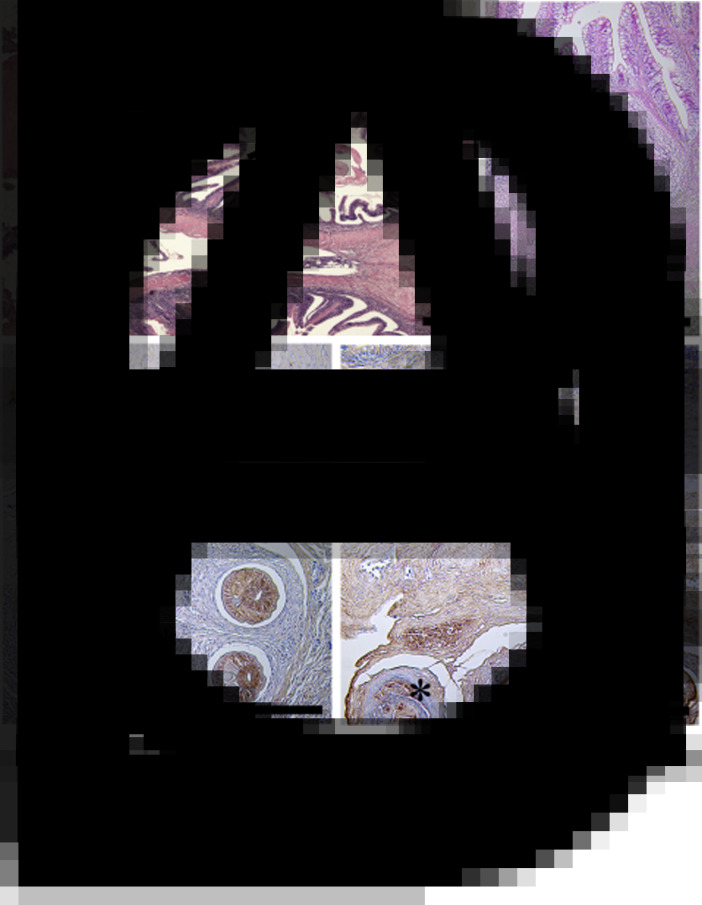

Fig. 5.

EES in fish infected with intestinal cestodes. (A) Silurus glanis parasitized with G. osculata (arrow). IF, intestinal fold. Haematoxylin–eosin stain; scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Salmo trutta infected with Cyathocephalus truncatus (arrow). ECs (curved arrows) immunoreactive to anti-glucagon in the intestinal epithelium are evident; scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Numerous ECs (curved arrows) immunoreactive to anti-CCK8 in the intestine of O. mykiss infected with the cestode E. crassum (arrow). The asterisk indicates a pyloric caecum. M, muscle layer; scale bar: 500 μm. (D) High number of ECs (curved arrows) in the intestinal epithelium of the stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus parasitized with cestodes (not shown); scale bar: 50 μm.

In the brown trout–C. truncatus system, the presence of cestodes was associated with a low number of ECs secreting some of the main digestive neuro-hormones in comparison with non-parasitized fish (Dezfuli et al., 2000) (Table 2, Fig. 5B). In contrast, in the stickleback– and rainbow trout–cestode systems, more CCK8-secreting ECs were documented (Bosi et al., 2005a) (Table 2, Fig. 5C and D). In Dibothricephalus dendriticus-infected internal organs of the powan, Coregonus lavaretus, the larvae become encapsulated and numerous mast cells containing SP and serotonin were seen inside the cyst (Dezfuli et al., 2007b). Moreover, within the C. lavaretus stomach wall, an increase in nervous elements containing bombesin, SP and galanin was reported around the encysted larvae (Dezfuli et al., 2007b) (Table 2).

In the myenteric plexus of the intestine of parasitized Salmoniformes, Dezfuli et al. (2000, 2007b) reported an increase in the number of nervous components secreting modulators such as met-enkephalin (Fig. 6A), galanin, SP, VIP and serotonin. Herein, we observed a greater number of nerve fibres immunoreactive to anti-PACAP in the intestine of the European eel, Anguilla anguilla harbouring Proteocephalus macrocephalus (Fig. 6B) than were seen in uninfected eel. Moreover, in some fish–parasite systems, met-enkephalin and serotonin were observed in a high number of mast cells (see Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Enteric nervous system and EES in fish infected with intestinal cestodes. (A) Salmo trutta infected with C. truncatus (arrowhead). Epithelial ECs (curved arrows) and nerve fibres (thick arrows) in the inner circular muscle layer, both immunoreactive to anti-met-enkephalin; scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Anguilla anguilla harbouring Proteocephalus macrocephalus (not shown). High magnification of neurons and nerve fibres (thick arrows) immunoreactive to pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide in the myenteric plexus; scale bar: 100 μm.

Effects of Acanthocephala

Taxon Acanthocephala is a relatively small group of helminths of about 1200 species (Smales, 2015) that infects the digestive tract of a wide range of vertebrates, particularly fish (]Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021a). Acanthocephalans are easily recognizable by their attachment organ, a retractable proboscis covered with hooks (Fig. 7A) that enables them to firmly attach to the host's gut wall (Sayyaf Dezfuli and Giari, 2022). Within this taxon, members of several genera, e.g. Pomphorhynchus and Acanthocephalus, cause extensive damage to their host intestine and visceral serosa by deep penetration of the proboscis; damage was heavier in fish intestines with the highest intensity of infection (Taraschewski, 2000; Dezfuli et al., 2002, 2011a). Recently the first papers reporting severe effects of an acanthocephalan in a farmed fish have been published. Several records dealt with outbreaks of Neoechinorhynchus buttnerae on farmed tambaqui, Colossoma macropomum, in Brazil. The parasite infects 100% of the tambaqui population, impairing host food uptake with impacts on host growth and great economic losses (Silva-Gomes et al., 2017). Tambaqui is the most produced fish species in Amazonian and Brazilian aquaculture and N. buttnerae is the main obstacle to success for tambaqui farming. Considering the severity of economic losses in Brazilian aquaculture caused by N. buttnerae, the perception that acanthocephalans are harmless parasites of fish should be revised.

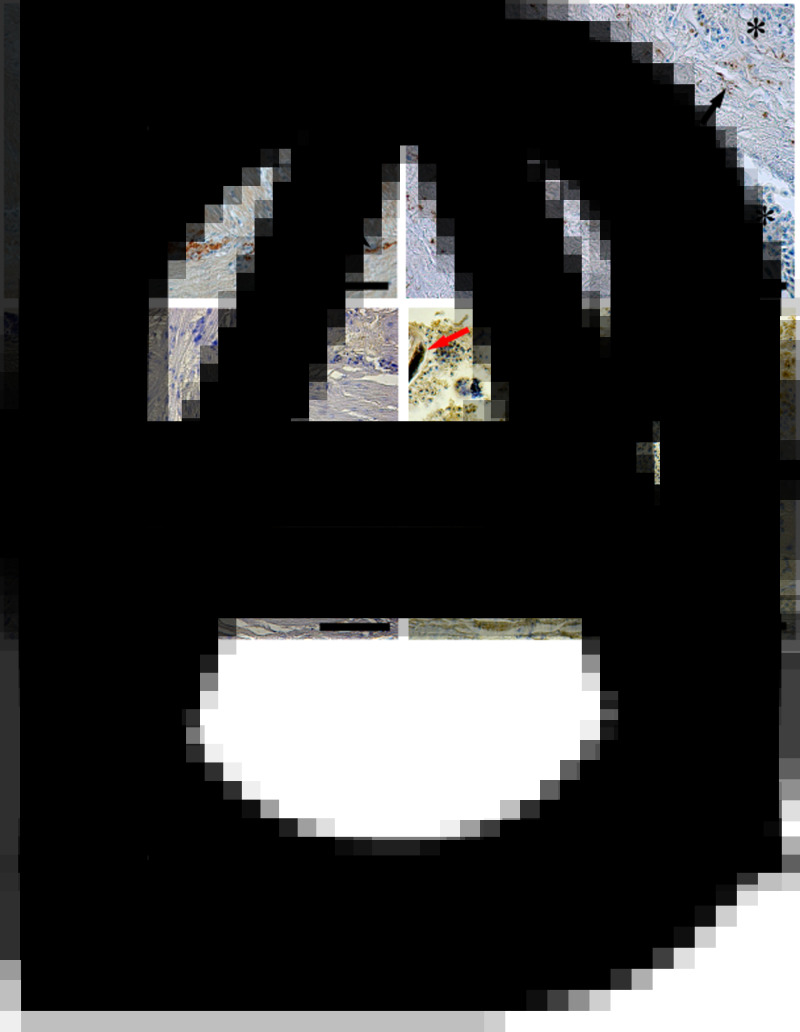

Fig. 7.

Fish intestine infected with acanthocephalans. (A) Salmo trutta parasitized with Dentitruncus truttae, parasite proboscis (arrow) reached tunica propria-submucosa (asterisk). AB/PAS; scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Squalius cephalus harbouring P. laevis, showing anti-galanin immunoreactive neurons and nerve fibres (thick arrows) in the myenteric plexus of the parasitized chub. The thin arrows show subtle nerve fibres in the connective capsule (asterisk) around the bulb of the acanthocephalan (not shown); scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Salmo trutta infected with P. laevis. High number of nerve endings (arrows) immunoreactive to anti-VIP in inner circular muscle layer of fish intestine. The asterisk indicates the acanthocephalan proboscis; scale bar: 50 μm. (D) Salmo trutta–P. laevis system, showing neurons and nerve fibres (thick arrows) of the myenteric plexus immunoreactive to anti-VIP. Note the occurrence of numerous nerve endings in longitudinal muscle layers (thin arrows). The asterisk shows the bulb of worm surrounded by a connective capsule (cc); scale bar: 50 μm. (E) Coregonus lavaretus infected with D. truttae (not shown), several ECs (curved arrows) immunoreactive to anti-SP in the intestinal epithelium are evident. The ECs are close to mucus cells secreting mainly mixed mucins (acid + neutral, deep violet stain, AB/PAS); scale bar: 50 μm. (F) Squalius cephalus–P. laevis system. In the intestinal epithelium of the infected chub, a high number of ECs (curved arrows) immunoreactive to anti-met-enkephalin are visible. The asterisk indicates the acanthocephalan; scale bar: 100 μm.

The acanthocephalan Pomphorhynchus laevis parasitizes freshwater fishes like brown trout (Dezfuli et al., 2002), chub, Squalius cephalus (Bosi et al., 2005b, 2015), common barbel, Barbus barbus and the Welsh catfish, Silurus glanis (Dezfuli et al., 2011a) (Table 3). In brown trout, P. laevis occupied the posterior part of the middle intestine, behind the pyloric caeca region, especially when it co-occurred with the cestode C. truncatus (Dezfuli et al., 2002). The effects of P. laevis on the NES of different hosts are summarized in Table 3, which shows the increase/decrease of cell densities detected with immunohistochemical protocols. Changes were evident in the neurons that secrete putative modulators of smooth muscle cell activity (galanin, CGRP, SP, VIP, n-NOS) (Fig. 7B–D), and in the ECs that produce anorexi-orexigenic hormones (CCK8, glucagon, NPY) (Dezfuli et al., 2002; Bosi et al., 2005b, 2015) (Table 3). In this study in the intestine of the common barbel, we observed an increase in the number of ECs secreting leu-enkephalin and SP when P. laevis occurred (Table 3, Fig. 7E). Likewise, we noticed a high number of ECs producing leu-enkephalin and SP in the intestine of C. lavaretus infected with Dentitruncus truttae (Table 3, Fig. 7F). In the intestinal connective capsule around the P. laevis bulb and proboscis, we observed nervous fibre network immunoreactive to bombesin, SP and galanin (Fig. 7B) (Dezfuli et al., 2002; Bosi et al., 2005b). Moreover, a high number of cells secreting endogenous opioids were found in parasitized intestine of some fish species. These results support the important role of these modulators in the physiological mechanisms of the fish digestive tract (Dezfuli et al., 2002, 2011a; Bosi et al., 2005b, 2015). Indeed, in the intestine of common barbel and Welsh catfish harbouring P. laevis, the occurrence of mast cells at the site of infection and their positive immunoreactivity to enkephalins and serotonin antibodies were reported by Dezfuli et al. (2011a).

Table 3.

Results of the effects of acanthocephalan infection on the NES of fish

| Host–parasite system Neuro-hormones | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bombesin | Ns, ECs | Ns | |||||

| CCK8 | ECs | Ns, ECs | |||||

| Gastrin | ECs | ||||||

| GRP | Ns | ||||||

| Glucagon | ECs | ||||||

| NPY | ECs | ECs | |||||

| Secretin | ECs | – | |||||

| Leu-Enkephalin | ECs | ECsa | ECs, MCs | ECsa | |||

| Met-ENKEPHALIN | Ns, ECs | MCs | MCs | ECs | MCs | ECs | MCs |

| β-Endorphin | ECs | ||||||

| Galanin | Ns, ECs | ||||||

| SP | Ns, ECs | ECsa | Ns | ECsa | MCs | ||

| NOS | Ns | ||||||

| VIP | Ns | Ns | |||||

| CGRP | Ns, ECs | ||||||

| Serotonin | Ns, ECs, MCs | ECs, MCs | MCs | ECs, MCs | Ns, MCs | ECs | MCs |

Source: Dezfuli et al. (2002, 2003, 2008, 2009, 2011a); Sayyaf Dezfuli et al. (2018b); Bosi et al. (2005b, 2015); unpublished data of this study.

Ns, neurons; ECs, endocrine cells; MCs, mast cells.

–, not detected.

The normal-reversal acronym indicates an increase-decrease of immune-positive cells, respectively.

Host–parasite system: A: Salmo trutta–Pomphorhynchus laevis; B: Salmo trutta–Dentitruncus truttae; C: Coregonus lavaretus–Dentitruncus truttae; D: Squalius cephalus–Pomphorhynchus laevis; E: Barbus barbus–Pomphorhynchus laevis; F: Silurus glanis–Pomphorhynchus laevis; G: Esox lucius–Acanthocephalus lucii.

This study.

Effects of Nematoda

Nematoda or roundworms are estimated to be more than 40 000 species, inhabiting a broad range of environments (Anderson, 2000). About 7000 species are estimated to be parasites of animals and plants. Several nematode species infect fish as definitive or paratenic hosts, occurring free in the gut lumen or encysted in internal organs and filet (Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021a, 2021c). Nematodes' affinity for a specific organ site depends on their nutritional and/or environmental requirements, and on the fish species (Bahlool et al., 2012; Moravec and Justine, 2020). The host tissue responses to invading nematodes range from acute to chronic inflammation and encapsulation of the parasite (Fig. 8A and B) (Bahlool et al., 2012; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021a, 2021b, 2021c).

Fig. 8.

Fish intestine parasitized with nematodes. (A) Nematode (arrow) inside the C. lavaretus pyloric caecum is evident. Haematoxylin–eosin stain; scale bar: 200 μm. (B) Anguilla anguilla intestine is infected with Contracaecum rudolphii larva (asterisk) between the tunica propria-submucosa (TS) and tunica muscularis (TM). Haematoxylin–eosin stain; scale bar: 200 μm. (C) Microphotograph shows C. rudolphii larvae inside a cyst (asterisk) on the outer surface of the eel gut. In the myenteric plexus, neurons and nerve fibres (arrows) are immunoreactive to the anti-met-enkephalin; scale bar: 200 μm. (D) Some C. rudolphii larvae in 2 cysts on external surface of the eel gut, neurons and nerve fibres (arrows) of the myenteric plexus immunoreactive to anti-leu-enkephalin are visible; scale bar: 200 μm.

Liver seems to be one of the most preferred organs for nematodes, often with a high intensity of infection and the entire parenchyma occupied by parasites (Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2016, 2021c). Similar findings were noticed in the liver of Gymnotus inaequilabiatus and Micromesistius poutassou infected respectively with the nematodes Brevimulticaecum sp. and Anisakis simplex. In fish liver, nerve fibres of sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation run along the portal triad, which includes branches of the hepatic artery, the portal vein and the biliary duct, although no intraparenchymal nerve fibres were observed in the trout liver (Esteban et al., 1998; Peinado et al., 2002).

An increase in the number of ECs secreting some neuromodulators was reported in the intestine of the flounder, Platichthys flesus parasitized with A. simplex (Table 4) (Dezfuli et al., 2007a). Moreover, in the same host–parasite system, bombesin- and galanin-positive nerve fibres showed a higher density in the myenteric plexus of infected vs uninfected P. flesus intestine (Table 4). Similarly, in fish parasitized with acanthocephalans (Fig. 7B), bombesin nerve fibres formed a fine net among connective cells of the capsule surrounding the parasite (Dezfuli et al., 2002, 2007a). In recent immunohistochemical tests on A. anguilla parasitized with the extraintestinal larvae of the nematode Contracaecum rudolphii, we observed an increased density of nerve fibres containing endogenous opioids, n-NOS and PACAP (Table 4, Fig. 8C and D).

Table 4.

Results of the effects of nematode on the NES of fish

| Host–parasite system | Platichthys flesus | A. anguilla | A. anguilla |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuro-Hormones | Anisakis simplex in the intestine | Contracaecum rudolphii in the intestine | Anguillicoloides crassus in the SB |

| Bombesin | Ns, ECs | ||

| Glucagon | – | ||

| NPY | ECs | ||

| Secretin | – | ||

| Leu-enkephalin | Nsa | ||

| Met-enkephalin | Nsa | ||

| Galanin | Ns | ||

| n-NOS | Ns | ||

| SP | – | ||

| VIP | – | Ns | |

| CGRP | Ns | ||

| Serotonin | Ns, ECs |

The nematode Anguillicoloides crassus infects the swim bladder (SB) of at least 6 eel species (Lefebvre et al., 2012). Several authors have suggested that the parasite impairs organ functions and significantly compromises the success of the eels' spawning migration (Pelster et al., 2016). In the SB of the European eel parasitized with A. crassus, Sayyaf Dezfuli et al. (2021b) noticed an increase in intramural neurons and nerve fibres immunoreactive to CGRP, n-NOS, VIP and serotonin antibodies (Table 4, Fig. 9A–C). Furthermore, in the same host–parasite system, ECs positive to NPY and serotonin antibodies were scattered among the gas gland cells of the epithelium of the SB (Table 4, Fig. 9D) (Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021b).

Fig. 9.

SB of A. anguilla infected with the nematode Anguillicoloides crassus (not shown). (A) Nerve fibres (thick arrows) immunoreactive to the anti-CGRP are numerous in the infected SB. Many subtle nerve fibres (thin arrow) are near blood vessels; scale bar: 50 μm. (B) The arrows indicate several nerve fibres immunoreactive to anti-VIP in a region rich in blood vessels (asterisks); scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Large ganglia with numerous neurons immunoreactive to anti-n-NOS in the tunica muscularis (TM) of the infected eel SB. E, epithelium; TPS, tunica propria-submucosa; scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Numerous anti-NPY immunoreactive ECs (curved arrows) in the epithelium of the infected eel SB. The blood vessels are ectatic and filled with erythrocytes (asterisks). The red thick arrows indicate 2 parasite larvae; scale bar: 100 μm.

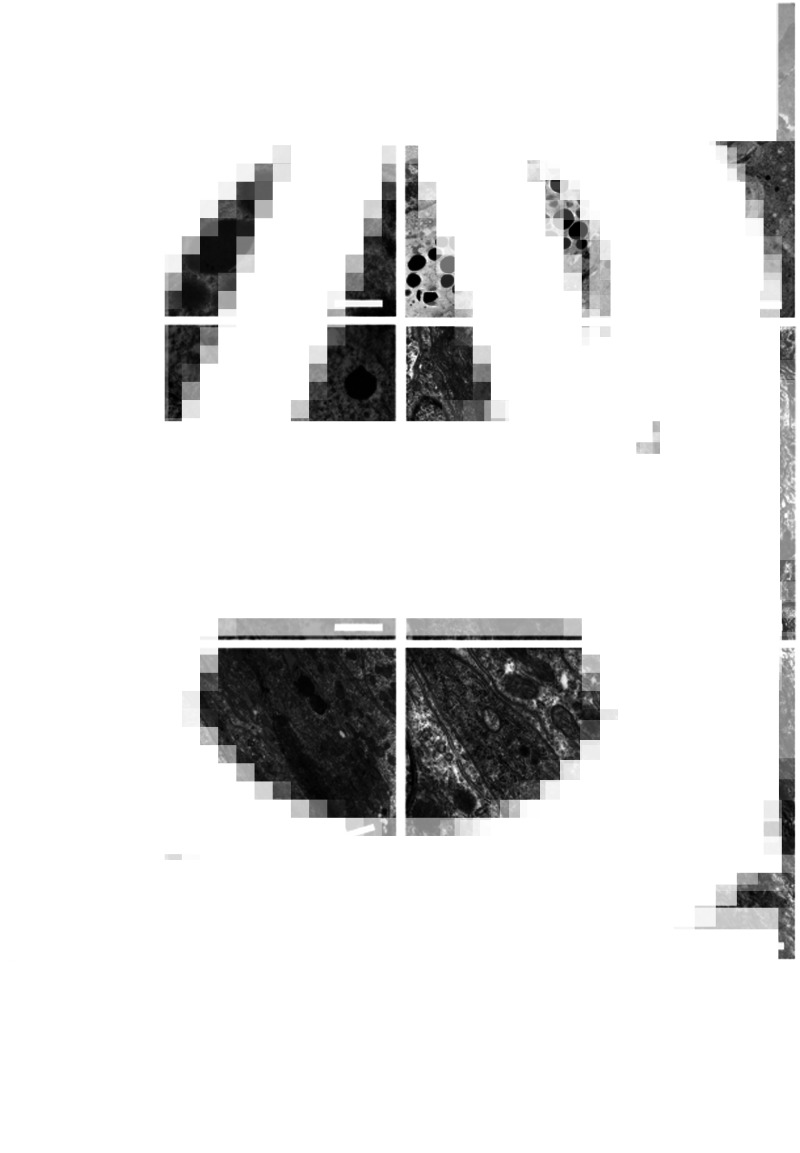

Effects of parasites at ultrastructural levels

By transmission electron microscope occurrence of enteric ECs in different fish–parasite systems was documented. Figure 10A shows the contact between an EC and mast cell in the epithelium of a mullet harboured an acanthocephalan. ECs were present also in tunica-propria-submucosa of the intestine of some fish species (e.g. S. trutta infected with acanthocephalan, Fig. 10B) (Dezfuli et al., 2000, 2003). In all fish, the ECs were readily characterized by the shape and electron density of their secretory granules (Fig 10A, C and D). The ECs with euchromatic nucleus (Fig. 10A–F) were approximately elongated in shape. Some ECs though were seen lodged between the basal portion of some epithelial cells without a free border towards the gut lumen (Fig. 10A, C, D, E and F). The cytoplasms of the ECs were darker than those of the surrounding cells and were observed to contain numerous round-to-oval-shaped secretory granules (Fig. 10A–F). The secretory granules were of approximately similar sizes and were filled with a finely electron-dense material (Fig 10A–F). Free ribosomes and rough endoplasmic reticulum with long cisternae were frequently seen next to secretory granules (Fig. 10F). In all fish species, ECs contained few mitochondria and did not possess well-developed Golgi complexes.

Fig. 10.

Transmission electron micrographs of neuroendocrine cells in the intestine of different fish species infected with helminths. In all neuroendocrine cells, numerous small electron-dense granules in cytoplasm are evident. (A) Intestine of Chelon ramada infected with digeneans; within the epithelium a neuroendocrine cell (arrow) is attached to a mast cell (asterisk); scale bar: 0.80 μm. (B) A neuroendocrine cell (arrow) and a mast cell within the tunica propria-submucosa of the intestine of C. lavaretus harbouring a nematode; scale bar: 3 μm. (C) A neuroendocrine cell (arrow) between nuclei of 2 intestinal epithelial cells of E. lucius parasitized with an acanthocephalan; scale bar: 1.4 μm. (D) Micrograph shows a neuroendocrine cell (arrow) within the epithelium of A. anguilla intestine infected with digeneans; scale bar: 2 μm. (E) A neuroendocrine cell (arrow) within the intestinal epithelium of S. glanis harbouring a cestode; scale bar: 3 μm. (F) In a higher magnification of Fig. 2, several small electron-dense granules are visible near the rough endoplasmic reticulum (arrows) in the cytoplasm; scale bar: 0.6 μm.

Effects of parasites on gut physiology

Intestinal parasites induce a regional inflammation altering the morphological structure of the gut wall, which affects biochemical and physiological homoeostasis (Fairweather, 1997; Palmer and Greenwood-Van Meerveld, 2001). The inflammation induces changes in the ENS with neuronal loss and/or hyper-innervation with consequences for nervous functions (Kulkarni et al., 2018). In addition, the structural changes induced by intestinal parasites can affect the EES with alterations in the gastrointestinal tract's normal functions (Fairweather, 1997; Palmer and Greenwood-Van Meerveld, 2001). Several host–parasite systems were investigated to clarify the mechanisms underlying changes in host physiology and behaviour (Klein, 2003; Thomas et al., 2005), nevertheless, the reasons for most changes remain unknown (Shaw and Øverli, 2012).

Alterations induced by parasites depend on parasite density (Weinersmith et al., 2016). In California killifish Fundulus parvipinnis experimentally infected with the brain-encysting trematode Euhaplorchis californiensis, parasite density determines the level at which the pathogen influences serotonin neural transmission (Helland-Riise et al., 2020). Little is known about the effects of intestinal parasites on the NES of the alimentary canal; conversely, many papers have been published on this topic in healthy/uninfected fish.

Often, the effects on fish tissue depend on the pathogen's intensity of infection. Accordingly, in the E. scophthalmi–turbot and E. ictaluri–channel catfish systems, high intensity of infection and its detrimental effects on the intestinal epithelium were responsible for severe enteritis and fish high mortality (Branson et al., 1999; Redondo et al., 2004; Li et al., 2012). Many digenean and cestode species, with their shallow attachment to the intestinal mucosa, do not cause appreciable tissue damage. In contrast, numerous acanthocephalan species, with the hook-covered holdfast on their proboscis, cause severe changes to normal gut architecture (Taraschewski, 2000; Dezfuli et al., 2002, 2003, 2010, 2011a). In the following sections, we discuss the effects of fish intestinal parasites on the main physiological mechanisms.

Neuroendocrine and immune system interactions in infected fish

Several studies have pointed out the essential role of the ENS–EES in inflammatory processes caused by intestinal parasites (Fairweather, 1997; Bosi et al., 2005a, 2005b, 2015; Halliez and Buret, 2015; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2017, 2021a). The correct release of cytokines, hormones and neuropeptides relies on interaction between the immune, nervous and endocrine systems (Lomax et al., 2006; Di Giovangiulio et al., 2015). One of the most important effects of parasites on their hosts is the activation of the innate and adaptive immune system, thanks to release of signal molecules, like the opioids leu- and met-enkephalin, by host cells (Mola et al., 2004; Nardocci et al., 2014; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2018b). In host–fish systems investigated so far, an increase in the number of ECs and/or nervous components containing enkephalins has been observed in parasitized vs uninfected fish (Bosi et al., 2005b, 2015; Dezfuli et al., 2011a; Losada et al., 2014; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2017). The opioids are signal molecules involved in the communication between neuroendocrine and immune systems (Stefano et al., 2017). Indeed, enkephalins were often found in mast cells (Bosi et al., 2005b; Dezfuli et al., 2009, 2011a; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2018b) and macrophage aggregates (Losada et al., 2014). The occurrence of intestinal parasites is associated with mucous hypersecretion and enkephalins are involved in mucous discharge (Zoghbi et al., 2006; Bosi et al., 2015; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2017). In the case of enteric helminth infection, the overproduction and release of mucous at the luminal surface has been considered a defence against parasites (Dezfuli et al., 2010; Bosi et al., 2017).

In fish gut, serotonergic neurons are the largest neuronal population of the myenteric plexus (Anderson and Campbell, 1988; Olsson et al., 2008b; Ceccotti et al., 2018) and serotonin is stored and secreted by macrophages, mast cells and T lymphocytes (Margolis and Gershon, 2016; Herr et al., 2017; Serna-Duque and Esteban, 2020). Moreover, serotonin is synthesized by ECs as a paracrine hormone (Bermúdez et al., 2007; Dezfuli et al., 2008, 2011a; Bosi et al., 2015; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2017, 2021b). In almost all known host–parasite systems, infected fish have more ECs containing serotonin than do uninfected conspecifics. In parasitized fish, high amounts of serotonin are consistent with a pro-inflammatory activity, whereas the higher number of neurons immunoreactive to serotonin indicates neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory functions (Serna-Duque and Esteban, 2020). In the gut epithelium of Welsh catfish harbouring the tapeworm Glanitaenia osculata, serotonin-containing ECs were observed close to the mucous and mast cells, suggesting an endocrine–immune interaction (Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2017). In the intestine of S. cephalus parasitized with an acanthocephalan, opioid peptides and the cholinergic co-mediator galanin were documented in ECs very near to the mucous cells (Bosi et al., 2015). Intestinal mucous cells are considered a component of the mucosal immune system with a key role in regulating inflammation (Johansson and Hansson, 2014; Bosi et al., 2015, 2017).

The expression of SP in different immunocompetent cells (Stoyanova and Gulubova, 2002; Bermudez et al., 2007) and its pro-inflammatory activity (Maggi, 1997) are well known. The tachykinin SP was noticed in the neuroendocrine and immune components of turbot infected with myxozoans (Bermudez et al., 2007) and in fish parasitized with tapeworms and acanthocephalans (Dezfuli et al., 2002, 2007b; Bosi et al., 2005b; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2018b; this study). Moreover, Nam et al. (2013) found a high expression of a PRP in the intestine and pyloric caeca of P. olivaceus infected with E. tarda. The administration of this peptide in vivo to olive flounder embryonic cells showed a stimulatory effect on tumour necrosis factor-α at the transcriptional level, suggesting its role in the modulation of the immune system (Nam et al., 2013).

Parasites can avoid the host's innate immune system by modifying their own molecular carbohydrate composition (Hammerschmidt and Kurtz, 2005) or by interfering with the host's cell-mediated immunity (Scharsack et al., 2004). It has been suggested that protozoans and metazoans have the capacity to deal with a broad range of host cellular and humoral elements, which allows the parasite to survive longer (Buchmann, 2012). In a host–parasite system, the complex interactions between the immune system and ENS–EES present a challenge to developing a deep understanding of direct or indirect manipulation of the host immune physiology (Thomas et al., 2005; Scharsack et al., 2007). For instance, studies on infected invertebrates suggested that excretory/secretory molecules of the parasites activate elements of the host immune system, which in turn affect its nervous system (Adamo, 2002; Scharsack et al., 2007). Furthermore, it seems that parasite-produced excretory and secretory molecules presumed to be key players in clinical manifestation of disease in humans possess a general biological role in invertebrates and lower vertebrates as well (Mehrdana and Buchmann, 2017). In sum, ‘Coevolution of hosts and parasites has resulted in a tight interaction between innate and adaptive immune elements in the host and a rich but, to a certain extent, unexplored array of immune evasion mechanisms in the parasites’ (Buchmann, 2014).

Neuroendocrine control of neurogenesis in infected fish

The gut is the largest microbial, endocrine and immune organ in both humans and mice (Kulkarni et al., 2017, 2018). Based on experimental assays, humans have been shown to replace about 90% of their myenteric neurons every 2 weeks by a dynamic balance between neuronal apoptosis and neurogenesis. Monoamines such as serotonin are involved in neuronal recruitment and re-sculpting of the neuronal network in response to changes of their internal homoeostasis or of the environmental state (Adamo, 2002). Barber and Wright (2005) suggested that, thanks to these monoamines, parasites can virtually manipulate their hosts' physiology and behaviour.

Some Acanthocephala genera, e.g. Pomphorhynchus and Southwellina, penetrate deeply through the gut wall to create a strong attachment and thereby cause extensive damage. As a result, the formation of a connective capsule around the worm praesoma was evident (Dezfuli et al., 2002). The connective capsule is formed by epithelioid cells, mast cells, fibrocytes and macrophage aggregates (Dezfuli et al., 2007b). In S. trutta and S. cephalus infected with P. laevis, within the capsule a subtle nerve fibre network immunoreactive to bombesin/GRP, VIP and CGRP was observed among the fibrocytes and immune cells (Dezfuli et al., 2002; Bosi et al., 2005b). Moreover, in the stomach and intestine of C. lavaretus, nerve fibres containing bombesin and SP were found in the connective capsule tissue around encysted plerocercoides of D. dendriticus (Dezfuli et al., 2007b). Our evidence from several fish–parasite systems suggests that it is likely that the neo-formed neural network in the inflammatory tissue used the abovementioned neuropeptides as neurotransmitters (Dezfuli et al., 2004; Bosi et al., 2005b). Indeed, it is reasonable to postulate that the new neural network has a role in angiogenesis, recruitment of immune cells and tissue repair in cases of chronic inflammation, which commonly occurs at the site of attachment of many acanthocephalans (Dezfuli et al., 2002, 2007b).

Neuroendocrine control of intestinal muscle cells in infected fish

Parasites seem to induce the synthesis of neuromodulators that have an inhibitory effect on host muscle cells (Serna-Duque and Esteban, 2020). In fish infected with enteric helminths, more synthesis and secretion of inhibitory neurotransmitters provoke relaxation of the gut musculature, which is essential for the holdfast mechanism of the parasite (Foster and Lee, 1996; Dezfuli et al., 2000; Serna-Duque and Esteban, 2020). Relaxation of the intestinal muscle might prevent rejection of the parasite and increases the retention and processing times of digesta in the intestine, which all benefit the parasite (Takei and Loretz, 2011). Foster and Lee (1996) found a homologue porcine VIP peptide synthesized by the nematode Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, which reduces the amplitude of contraction of uninfected rat intestine in vitro. Apparently, secretory/excretory molecules produced by the parasite could prevent its rejection from the host intestine (Foster and Lee, 1996). Conversely, in turbot intestine infected with the myxozoan E. scophthalmi, Bermúdez et al. (2007) and Losada et al. (2014) found fewer neurons immunoreactive to VIP and bombesin. This contrast might indicate that the regulatory mechanism suitable for an intestinal myxozoan differs from that for enteric worms (Bermúdez et al., 2007).

Fish endoparasitic helminths can invade and colonize organ(s), the host produces active or partly effective immune responses against new infections, meanwhile, the established worms might survive for longer time; such phenomenon is called concomitant immunity and is a result of an elaborate interaction between host and helminth and relies on immune regulation and immune evasion (Buchmann, 2012). The influence of intestinal pathogens on gut motility is detailed in the recent review by Serna-Duque and Esteban (2020), who proposed 3 types of fish responses to parasites.

Neuroendocrine control of food intake in infected fish

Structural integrity of the intestine is necessary for normal control of food intake and food processing (Gay et al., 2003). Many intestinal parasites affect the intestine's structural components, primarily ENS and EES (Mercer and Chappell, 2000; Losada et al., 2014; Bosi et al., 2015). The occurrence of gastrointestinal parasites in mammals (Mercer et al., 2000) and in fish (de Matos et al., 2017) is often associated with a reduction in the host food intake. Similarly, heavy infections of rainbow trout with the protozoan Cryptobia salmositica (Lowe-Jinde and Zimmerman, 1991) and of Atlantic salmon with the copepod Lepeophtheirus salmonis (Dawson et al., 1999) resulted in reduced food intake by the host fish. Plerocercoid of S. solidus (Cestoda) occurs in the body cavity of the small fish G. aculeatus; the presence of the parasite affects the host brain by reducing monoaminergic activity and enhancing the immune response (Øverli et al., 2001). Sticklebacks parasitized with the cestode increase their food intake rates (Ranta, 1995; Barber and Wright, 2005). Nevertheless, whether intestinal parasites increase or decrease food intake by the host fish varies by species of host and parasite, infection intensity and which organ is infected (Lowe-Jinde and Zimmerman, 1991; Ranta, 1995; Dawson et al., 1999; Barber and Wright, 2005). Alteration of the major anorexi-orexigenic factors in the gut of parasitized fish will be discussed below.

Ghrelin

In fish, the action of ghrelin is species-specific (Blanco et al., 2021). Its secretion promotes food intake in C. auratus and cavefish, Astyanax fasciatus mexicanus (Unniappan et al., 2004; Penney and Volkoff, 2014; Blanco et al., 2017) but, when peripherally administrated to rainbow trout (Jönsson et al., 2010) and channel catfish (Schroeter et al., 2015), ghrelin showed an anorexigenic activity. The ghrelin gene is downregulated in channel catfish infected with E. ictaluri (Li et al., 2012), suggesting a synthesis reduction likely related to increased food intake. No data are available on changes in ghrelin levels for fish parasitized with intestinal helminths.

Gastrin/CCK8

Gastrin and CCK8 share the same 5 C-terminal amino acids. In the immunohistochemical method, the use of polyclonal antibodies for these peptides can produce a cross-reaction in the intestinal ECs.

In the digestive tract of infected fish, gastrin stimulates gastric acid secretion by oxyntopeptic cells of the stomach and promotes cell proliferation, which induces gut epithelial hypertrophy (Dezfuli et al., 2003). In goldfish, suppression of food intake is observed 45 min after intraperitoneal injection of CCK8, and the effect is dose-dependent (Himick and Peter, 1994a; Volkoff et al., 2003; Penney and Volkoff, 2014; Zhang et al., 2017). An increased number of ECs immunoreactive to CCK8 was observed in turbot infected with myxozoans and downregulation of gastrin mRNA expression was found in the same host–parasite system (Bermúdez et al., 2007; Robledo et al., 2014). Similarly, the cestodes C. truncatus in S. trutta and Eubothrium crassum in O. mykiss induced a decrease in ECs immunoreactive to gastrin and an increase of cells positive to CCK8 in comparison with uninfected conspecifics (Dezfuli et al., 2000; Bosi et al., 2005a). In fish–acanthocephalan systems, the ECs secreting gastrin and CCK8 were less in number, thus, it was suggested that the occurrence of intestinal helminths might increase host food intake (Dezfuli et al., 2002, 2003; Bosi et al., 2005a).

Glucagon

In vertebrates, a 29 amino acid peptide chain forms glucagon, which has an anorexigenic effect (Navarro et al., 1993; Le Bail and Boeuf, 1997; Moon, 1998). The post-prandial release of glucagon induces high glucose plasma levels and increases lipolytic activity (Navarro et al., 1993; Moon, 1998). In fish, the peripheral administration of glucagon-like peptide-1 abolishes food intake (Blanco et al., 2017), thanks to mRNA increase expression of specific signal molecules in the brain (Polakof et al., 2011).

In fish, a significant reduction in the number of ECs secreting glucagon was observed in the turbot parasitized with myxozoans (Losada et al., 2014), and in different fish species infected with cestodes (Dezfuli et al., 2003; Bosi et al., 2005a) and acanthocephalans (Bosi et al., 2005b). Low synthesis and secretion of glucagon in the presence of intestinal pathogens increase fish appetite, which benefit the enteric parasites (Bosi et al., 2005a, 2005b).

NPY/PYY

The NPY family includes 4 peptides, namely NPYa, NPYb, PYYa and PYYb, all derived from a single ancestral gene (Larhammar et al., 1998; Yan et al., 2017). In fishes, after synthesis the occurrence or disappearance of each of the 4 peptides depends on the teleost species (Sundstrom et al., 2008). The main physiological action of the NPY family of peptides is the regulation of appetite and alimentary behaviour. In fish, central or peripheral administration of NPY increased food intake (Aldegunde and Mancebo, 2006; Kiris et al., 2007; Yokobori et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2013). However, conflicting results have been found in parasitized fish. With reference to myxozoan, reduced PYY-mRNA expression was reported in channel catfish infected with E. ictaluri (Li et al., 2012). In the brown trout–P. laevis system a low number of NPY-secreting ECs was found (Dezfuli et al., 2002), whereas in the chub–P. laevis system more cells synthesize NPY (Bosi et al., 2005b). Surprisingly, no difference in ECs immunoreactive to NPY was observed in Salmoniformes infected with cestodes (Dezfuli et al., 2000; Bosi et al., 2005a) and in P. flesus parasitized with the nematode A. simplex (Dezfuli et al., 2007a).

The interaction between NPY and several appetite modulators and growth factors is well established (Volkoff et al., 2003, 2005; Volkoff, 2006). For example, NPY inhibited the expression of CCK8 and PACAP, and on the other hand, increased the expression levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin-like growth factor-2. According to Zhou et al. (2013), NPY increases host food intake and energy metabolism. Our results on fish–helminth systems indicate alteration of the components involved in the secretion of NPY (Dezfuli et al., 2002; Bosi et al., 2005b).

Bombesin/GRP

Bombesin and the related GRP are involved in the inhibition of gastric emptying and regulation of gastric acid secretion (Holmgren, 1985). Bombesin was observed in nerve fibres of the connective axis of the fish intestinal folds and myenteric plexus; therefore, it might be reasonable to presume it has a role in regulation of mucosal secretion and stimulation of gut motility (Holmgren, 1985; Dezfuli et al., 2002, 2007a, 2007b; Bosi et al., 2005b). Indeed, peripheral administration of bombesin/GRP inhibits food intake in C. auratus and carp, Cyprinus carpio, indicating its anorectic effect (Beach et al., 1988; Himick and Peter, 1994b; Merali et al., 1999).

Losada et al. (2014) mentioned that the low number of ECs immunoreactive to bombesin found in infected turbot is in favour of gastric emptying and reduction of the fish's sensation of satiety. The presence of cestodes or acanthocephalans in the intestine of 2 Salmoniformes species was associated with fewer bombesin/GRP-secreting ECs, probably associated with a starvation sensation (Dezfuli et al., 2002, 2003; Bosi et al., 2005a; Losada et al., 2014). Nevertheless, in the stomach of C. lavaretus, infected with the cestode D. dendriticus, the number of ECs immunoreactive to bombesin was higher than in uninfected powan (Dezfuli et al., 2007b). Our data on bombesin in the stomach of C. lavaretus differed from those in the intestine of 2 other Salmoniformes species. An explanation might be the same as that provided above for peptides by Losada et al. (2014); namely, bombesin has different physiological roles in the stomach and the intestine. With this in mind, it might be reasonable to presume, the occurrence of the ECs immunoreactive to bombesin in 2 organs with different functions could differ.

Secretin/VIP/PACAP

Secretin, VIP and PACAP belong to the same peptide superfamily. The release of secretin stimulates pancreatic bicarbonate secretion to neutralize acidic chyme in the passage from stomach to the intestine (Whitmore et al., 2000). In S. trutta infected with the cestode C. truncatus and/or the acanthocephalan P. laevis, a low number of ECs immunoreactive to secretin have been seen (Dezfuli et al., 2003). However, no significant difference was observed in the number of ECs positive to secretin in O. mykiss harbouring the cestode E. crassum and uninfected fish (Bosi et al., 2005a). Secretin seems to be a tetrapod hormone with no orthologue in teleosts undiscovered yet (Roch et al., 2009; Takei and Loretz, 2011). Therefore, the immunoreactivity found in the parasitized intestine of S. trutta and O. mykiss probably was due to a cross-reaction against molecular haptens belonging to a peptide of the same superfamily.

The occurrence of VIP as a neurotransmitter in the myenteric plexus of fish has been documented in several accounts since the late 1990s (Kiliian et al., 1997; Olsson and Holmgren, 1997, 2000). VIP stimulates gastric acid secretion, inhibits smooth muscle contraction and has a vasodilatory effect on the gastrointestinal circulatory system (Kågstrom and Holmgren, 1997; Olsson and Holmgren, 1997). The peptide PACAP is related to VIP and initially it was isolated from the ovine hypothalamus as an activator of cyclic adenosine monophosphate production in pituitary cells (Hirabayashi et al., 2018). It is presumed that in teleost evolution the specific whole-genome duplication raised 2 types of PACAPs (PACAP1 and PACAP2) and 2 types of PACAP receptors (PAC1Rs and PAC1Ra) (On and Chow, 2016; Nakamachi et al., 2019). PACAP is a neuromodulator inhibiting smooth muscle activity in fish (Matsuda et al., 2000; Li et al., 2015) and with its anorectic effect, this peptide suppresses food intake in goldfish and zebrafish, Danio rerio, after intra-cerebroventricular administration (Sekar et al., 2017; Nakamachi et al., 2019). Indeed, VIP is also a signal molecule with anorectic effects (Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Takei and Loretz, 2011; Volkoff, 2016).

Most of our knowledge on this peptide family in infected fish concerns VIP and an increase of the peptide in neural myenteric immunoreactive components occurring in the presence of a parasite (Dezfuli et al., 2002; Bosi et al., 2005b). A greater component of PACAP/VIP-ergic nerve elements is involved in inhibition of gut motility (see above). In the intestine of turbot infected with E. scophthalmi, a decrease in the number of epithelial ECs secreting VIP was observed and the authors postulated an effect of the peptide on gut mucosa (Bermúdez et al., 2007).

Effects of parasite on the regulation of SB physiology

SB is a hydrostatic organ and provides neutral buoyancy (Pelster et al., 2016). In physostomous teleosts it is connected to the gut. European eel reproduction depends on a spawning migration of 5000–7000 km from the European coast to the Sargasso Sea over about 5 months. This long-distance journey induces high physiological stress especially on the eel's SB.

The eel SB wall has 4 distinct layers with an architectural aspect very similar to the anterior intestine. The innermost layer facing the SB lumen is the mucosa; it has a simple cuboidal epithelium containing gas gland cells, which form folds. A set of extrinsic and intrinsic ganglia regulates the inflation/deflation of gas in the SB and this mechanism is controlled by the autonomic nervous system (Nilsson, 2009). It has been mentioned that the presence of adult A. crassus in the lumen reduces the gas-secreting capacity of gas gland cells and SB wall elasticity (Würtz and Taraschewski, 2000; Barry et al., 2014). Recently, morphological differences between infected and uninfected SB appeared in Sayyaf Dezfuli et al. (2021b). The SB with no parasites has small intramural ganglia, with thin and few nerve fibres. In contrast, infected SB possesses large ganglia and many fibres containing CGRP, n-NOS and VIP and they are abundant especially in regions rich in blood vessels (Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021b). In fish SB, CGRP, n-NOS and VIP have a vasodilator effect and increase the flow through the gas gland cells (Lundin and Holmgren, 1984; Finney et al., 2006). In addition, serotonin and VIP respectively cause contraction and relaxation of the smooth muscle cells in the SB (Finney et al., 2006). Many ECs secreting NPY and serotonin were noticed in the SB; most likely they have a defensive role against the pathogens (Wang et al., 2018; Sayyaf Dezfuli et al., 2021b).

Conclusions and future directions

In fish as in other animals the main function of the digestive canal is to acquire food, then proceed with intake of vital nutrients. Diet of fishes varies in relation to their habitats and species (Bakke et al., 2010). Digestion is a very complex process that relies on both endocrine and neuronal systems (Olsson and Holmgren, 2001; Holmgren and Olsson, 2009), including a great number of signal molecules, namely neuro-hormonal modulators affecting fish digestion and feeding behaviour (Holmgren and Olsson, 2009; Serna-Duque and Esteban, 2020; Blanco et al., 2021). Intestinal motility is involved in the breakdown and transport of food and is fundamental for nutrient intake (Gräns and Olsson, 2011). Any disorder in intestinal motility caused by pathogens or inappropriate diet results in the fish obtaining less nutrients from food. Moreover, motility is a well-coordinated process that relies on intrinsic and extrinsic factors including the innate properties of the smooth muscles, hormones and nerves (Gräns and Olsson, 2011).

Both wild and farmed fish can harbour pathogens in their gut. Parasites can change host gastrointestinal physiology; recent reviews related to the NES and intestines of parasitized fish include Wang et al. (2018), Serna-Duque and Esteban (2020) and Sayyaf Dezfuli et al. (2021a). This study focuses on the effects of parasites on the occurrence of neuroendocrine molecules responsible for gut motility and food intake in several fish species from the wild.

The intestinal nematode N. brasiliensis of rodents secretes and releases a VIP homologue peptide, which directly inhibits the function of smooth muscle in the gut (Foster and Lee, 1996), increasing the time of retention and processing of digesta and greatly benefiting the parasite (Takei and Loretz, 2011). This scenario found in the rodent–nematode system could also be true for many fish-enteric helminths, especially for cestodes and acanthocephalans, which lack an alimentary canal and gain nutrients through their specialized tegument. Furthermore, in most fish–parasite systems the occurrence of intestinal worms induces an increase or decrease of signal molecules with orexigenic and/or anorexigenic effects. Alteration of neuro-hormone synthesis and secretion in fish often increases food intake by the host with clear advantages for the parasite.

Parasites produce and release molecules that act against the host immune system (Buchmann, 2012, 2014, 2022a, 2022b) or influence some gut physiological functions. Very few observations are available on these molecules in fish–helminth systems (Bahlool et al., 2013; Franke et al., 2014; Mehrdana and Buchmann, 2017). It is interesting that, using mass spectrometry, Maeda et al. (2019) detected 546 different proteins collected from the body surface of Strongyloides venezuelensis, a gastrointestinal nematode of rats. About 20.1% of these proteins were identified as eukaryotic signal peptides, and among them, there were 2 histone family proteins (Maeda et al., 2019). Histones have antimicrobial properties in the human intestine (Kai-Larsen et al., 2007); nonetheless, histone-like molecules excreted/secreted by S. venezuelensis presumably modify and/or maintain the gut microbiota environment in favour of the parasite (Maeda et al., 2019). In a similar survey in fish, Hébert et al. (2015) found 4 out of 94 proteins excreted/secreted by the cestode S. solidus. Given the high protein sequence homology with stickleback host proteins, it was postulated that these proteins could modulate host physiology and behaviour (Barber et al., 2017). Moreover, Ye et al. (2021) demonstrated a relationship between the release of catabolic molecules from the bacteria E. tarda and stimulation of the vagal sensory ganglia by ECs in the zebrafish intestine. Poulin (2010) stated that any changes induced in host physiology that benefit the parasite should be genetically selected for.

Parasites are known to respond to the cellular and humoral components of the host immune system (Buchmann, 2022b). However, most of the mechanisms involved in the interaction between parasite and fish are still unknown. Increasing the number of fish–parasite model systems in the wild and in experimental assays will help to fill that void. There is a dearth of information on the impact of parasites on fish gut physiology and feeding behaviour. Future research using modern genomic and transcriptomic techniques will give us more information about the role of the ENS and EES against enteric parasites.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor J. Russell Stothard (editor-in-chief of Parasitology) and Professor John T. Ellis (deputy and special issues editor) for this special thematic collection, for inviting us to contribute this article. The authors also thank G. Servadei and F. Donzellini from the University of Ferrara for help in the first draft of the graphical abstract.

Footnotes

Until 2016, in all his articles Bahram Dezfuli appeared as Dezfuli B. In 2016 another author with the same surname (Dezfuli) and initial (B) working on human cancer started to publish as Dezfuli B. To avoid this homonymy and problems in bibliometric analyses, since 2016, the first part of the surname (Sayyaf) was added to Dezfuli thus in all subsequent articles, Bahram Sayyaf Dezfuli appears as Sayyaf Dezfuli B.

Author contributions

G. B.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation and writing – original draft. B. J. M.: editing. F. P.: investigation and validation. B. S. D.: methodology, investigation, data curation and funding acquisition.

Financial support

This work was supported in part by local grants from the University of Ferrara to B. Sayyaf Dezfuli (FAR 2021).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare having no conflict of interest.

References

- Adamo SA (2002) Modulating the modulators: parasites, neuromodulators and host behavioural change. Brain Behavior and Evolution 60, 370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlman H and Nilsson O (2001) The gut as the largest endocrine organ in the body. Annals of Oncology 12, S63–S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldegunde M and Mancebo M (2006) Effects of neuropeptide Y on food intake and brain biogenic amines in the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Peptides 27, 719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldman G and Holmgren S (1995) Intraduodenal fat and amino acids activate gallbladder motility in the rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. General and Comparative Endocrinology 100, 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RC (2000) Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their Development and Transmission. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C and Campbell G (1988) Immunohistochemical study of 5-HT-containing neurons in the teleost intestine: relationship to the presence of enterochromaffin cells. Cell and Tissue Research 254, 553–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahlool QZM, Skovgaard A, Kania P, Haarder S and Buchmann K (2012) Microhabitat preference of Anisakis simplex in three salmonid species: immunological implications. Veterinary Parasitology 190, 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahlool QZM, Skovgaard A, Kania PW and Buchmann K (2013) Effects of excretory/secretory products from Anisakis simplex (Nematoda) on immune gene expression in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Fish & Shellfish Immunology 35, 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakke AM, Glover C and Krogdahl Å (2010) Feeding, digestion and absorption of nutrients. Fish Physiology 30, 57–110. [Google Scholar]

- Barber I and Huntingford FA (1995) The effect of Schistocephalus solidus (Cestoda: Pseudophyllidea) on the foraging and shoaling behaviour of three-spined sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus. Behaviour 132, 1223–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Barber I and Wright HA (2005) Effects of parasites on fish behaviour: interactions with host physiology. Fish Physiology 24, 110–149. [Google Scholar]

- Barber I, Mora AB, Payne EM, Weinersmith KL and Sih A (2017) Parasitism, personality and cognition in fish. Behavioural Processes 141, 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry J, McLeish J, Dodd JA, Turnbull JF, Boylan P and Adams CE (2014) Introduced parasite Anguillicola crassus infection significantly impedes swim bladder function in the European eel Anguilla anguilla (L). Journal of Fish Diseases 37, 921–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach MA, McVean A, Roberts MG and Thorndyke MC (1988) The effects of bombesin on the feeding of fish. Neuroscience Letters 32, S46. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez R, Vigliano F, Quiroga MI, Nieto JM, Bosi G and Domeneghini C (2007) Immunohistochemical study on the neuroendocrine system of the digestive tract of turbot, Scophthalmus maximus (L.), infected by Enteromyxum scophthalmi (Myxozoa). Fish & Shellfish Immunology 22, 252–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco AM, Bertucci JI, Valenciano AI, Delgado MJ and Unniappan S (2017) Ghrelin suppresses cholecystokinin (CCK), peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in the intestine, and attenuates the anorectic effects of CCK, PYY and GLP-1 in goldfish (Carassius auratus). Hormones and Behavior 93, 62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco AM, Calo J and Soengas JL (2021) The gut–brain axis in vertebrates: implications for food intake regulation. Journal of Experimental Biology 224, jeb231571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohórquez DV and Liddle RA (2015) Gastrointestinal hormones and neurotransmitters. In Feldman M, Friedman LS and Brandt LJ (eds), Sleisenger and Fortran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Saunders/Elsevier, pp. 36–54. [Google Scholar]