Summary

Environmental lipids are essential for fueling tumor energetics, but whether these exogenous lipids transported into cancer cells facilitate immune escape remains unclear. Here, we find that CD36, a transporter for exogenous lipids, promotes acute myeloid leukemia (AML) immune evasion. We show that, separately from its established role in lipid oxidation, CD36 on AML cells senses oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL) to prime the TLR4-LYN-MYD88-nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway, and exogenous palmitate transfer via CD36 further potentiates this innate immune pathway by supporting ZDHHC6-mediated MYD88 palmitoylation. Subsequently, NF-κB drives the expression of immunosuppressive genes that inhibit anti-tumor T cell responses. Notably, high-fat-diet or hypomethylating agent decitabine treatment boosts the immunosuppressive potential of AML cells by hijacking CD36-dependent innate immune signaling, leading to a dampened therapeutic effect. This work is of translational interest because lipid restriction by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved lipid-lowering statin drugs improves the efficacy of decitabine therapy by weakening leukemic CD36-mediated immunosuppression.

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

CD36 on AML cells suppresses T cell proliferation independently of lipid oxidation

-

•

OxLDL and palmitate synergize to inhibit T cell activity via CD36 signaling in AML cells

-

•

Targeting CD36 signaling with statins improves the efficacy of decitabine therapy in AML

Guo et al. find that OxLDL and palmitate uptake by AML cells synergistically upregulates CD36-mediated innate immune signaling to suppress T cell activity. High-fat-diet or decitabine treatment dampened the therapeutic effect by hijacking CD36 signaling. Targeting the CD36 immunosuppressive pathway with statins improves the efficacy of decitabine therapy in AML.

Introduction

Hypomethylating agents (HMAs) are approved epigenetic drugs for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes,1,2 and the addition of the BCL2 inhibitor to HMAs can greatly increase their anti-AML efficacy by blocking amino acid metabolism in leukemia stem cells.3,4,5 Derepression of tumor-suppressor genes by DNA demethylation is the most likely mechanism of action of HMAs.6 Recently, HMAs have been reported to evoke viral mimicry-mediated innate immune signaling in tumor cells and enhance immune responses.7,8 However, other studies show that in certain settings, HMAs induce the expression of immunosuppressive molecules in cancer cells and that T cell function is inhibited after HMAs treatment in AML.9,10,11 Given that HMAs in combination with immune checkpoint blockade therapy have shown limited clinical benefit in AML,12,13,14 clarity surrounding tumor immunity during HMA therapy will improve the benefit of this combination therapy.

Increased lipid accumulation is a common metabolic alteration in the tumor microenvironment (TME).15,16,17 In addition to providing energy for cancer cell growth and migration,18,19,20,21 environmental lipids contribute to an immunosuppressive TME.17,22,23,24 For these reasons, it is thought that high blood fat fuels cancer progression.25 CD36 is a major transporter of environmental long-chain free fatty acids (FAs), such as palmitate.26 The FA-transporter role of CD36 has been shown to induce lipid peroxidation in CD8+ T cells and activate FA oxidation (FAO) in cancer cells.18,21,24,27,28 In addition, CD36 triggers innate immune signaling by acting as a classic receptor for pathogen-associated molecular patterns and damage-associated molecular patterns, such as oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL), in macrophages and dendritic cells.29,30 However, how these two roles of CD36 collaborate to influence the innate immune response and whether CD36 on cancer cells facilitates immune escape remain unclear.

In this study, we found that OxLDL and palmitate synergistically activated the CD36-TLR4-MYD88-nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) innate immune signaling axis, but not lipid oxidation, thereby enhancing the ability of AML cells to suppress T cell proliferation and negatively affecting outcomes. High blood fat or treatment with the HMA drug decitabine boosted the immunosuppressive potential of AML cells in a CD36-dependent manner, which can be inhibited by lipid-lowering statin drugs.

Results

CD36 on AML cells suppresses T cell activity

Consistent with previous reports,18,31 we found that CD34+ bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMCs) sorted from 6 patients with AML displayed a 2- to 5-fold increase in FA transport rate compared to CD34+ cord blood cells by using a fluorescent long-chain FA analog, BODIPY-dodecanoic acid (Figure S1A), and the rate of FA uptake in CD34+ AML cells and an AML cell line (MV4-11) was reduced by sulfosuccinimidyloleate (SSO), a CD36 inhibitor (Figure S1B). Flow cytometry confirmed elevated CD36 levels in CD34+ AML cells and AML cell lines compared with CD34+ cord blood cells, as well as with an erythroid leukemia cell line (K-562) (Figures S1C and S1D). Then, we overexpressed an empty vector (OE control [Ctrl]), Cd36 (OE Cd36), or a Cd36 mutant lacking the final 10 amino acids of the C terminus required for plasma membrane localization (OE Cd36 mutant)32 in mouse C1498 AML cells, which originally showed low CD36 levels (Figure S1E). Intravenous implantation of these engineered cells into C57BL/6 mice showed that OE Cd36, but not the OE Cd36 mutant, shortened the survival time compared to OE Ctrl (Figure S1F). Then, the OE Cd36 C1498 cells were modified by CRISPR-Cas9 to produce Cd36 knockout (Cd36KO) cells and control cells (Cd36NC) which were labeled with green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Figure S1G). Cd36 KO decreased the AML progression in BM and spleen of C57BL/6 recipients (Figures S1H and S1I), confirming a previously documented role for CD36 in promoting AML malignancy.31,33

Given that no significant differences were observed in the growth kinetics of Cd36KO cells compared with Cd36NC cells in vitro (Figure S1J) and that AML samples34 with high CD36 expression had lower infiltration of T cells and natural killer (NK) cells compared with AML samples with low CD36 expression (Figure S1K), we tested whether CD36 exerted its oncogenic activity by tuning the immune system. We observed that the prolonged survival conferred by Cd36 KO in immunocompetent C57BL/6 models was severely attenuated in immunodeficient NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Sug/JicCrl (NOG) recipients (Figure 1A). Moreover, treating C57BL/6 recipients with neutralizing antibodies showed that depletion of T cells, but not of NK cells, diminished the anti-AML effect of Cd36 KO (Figures 1B and S1L). Next, we established a humanized mouse model by reconstituting human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in NOG-double KO (major histocompatibility complex double KO) mice (PBMC-NOG) (Figure S1M). Then, we selected MV4-11 cells, which showed no dependence on CD36 in DepMap,35 to generate CD36KO and CD36NC lines by CRISPR-Cas9 (Figures S1N and S1O) and injected them subcutaneously into PBMC-NOG mice, respectively. Compared with control, CD36 KO restricted the growth of MV4-11 cells, elevated the percentage of human T cells, and reduced expression of the exhaustion marker PD-1 in human CD8+ T cells (Figures 1C–1F). Next, OE Cd36 C1498 cells expressing ovalbumin (OVA) as a model tumor antigen were established. After verifying that these cells presented the OVA-derived SIINFEKL peptide on H-2Kb (Figure S1P), we knocked out Cd36 by CRISPR-Cas9 and found that Cd36 KO decreased the abundance of C1498 cells while increasing the abundance of T cells that specifically bound the H-2Kb/OVA tetramer in the spleen of the C57BL/6 recipients (Figures 1G and 1H). In addition, Cd36 KO increased the activation marker CD107a while decreasing co-inhibitory receptors, including PD-1 and LAG-3, in antigen-specific T cells (Figures 1I and 1J). Furthermore, CD8+ T cells isolated from the recipients transplanted with Cd36KO C1498 cells exhibited an enhanced killing effect toward OVA-C1498 cells in vitro as compared to those isolated from control recipients (Figure 1K). To test whether tumor-specific memory T cells were generated by CD36 inhibition, we subcutaneously implanted C1498 cells into C57BL/6 mice in addition to spleen-derived T cells from either Cd36KO C1498 cell-challenged mice or treatment-naive mice. None of 5 mice that received T cells from treatment-naive mice rejected C1498 cells, whereas 3 of 5 mice that received T cells from the Cd36KO C1498 cell-challenged mice rejected C1498 cells (Figure 1L). These 3 mice also rejected a subsequent rechallenge with an even higher number of C1498 cells (Figure 1L). These data suggest that CD36 on AML cells suppresses T cell activity.

Figure 1.

CD36 on AML cells suppresses T cell proliferation

(A and B) C57BL/6 mice or NOG mice (n = 5 per group) intravenously injected with 2 × 106 Cd36NC or Cd36KO C1498 cells were treated with or without antibodies (150 μg/mouse, 3 times/week, intraperitoneal [i.p.]) for 2 weeks after injection and were monitored for survival.

(C–F) 1 × 107 CD36NC or CD36KO MV4-11 cells were subcutaneously injected into PBMC-NOG mice (n = 5 per group). Tumor size (C), human T cells in PB (D and E), and PD-1+ cells in human CD3+CD8+ T cells in PB (F) were monitored 30 days after injection.

(G–K) C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 per group) intravenously injected with 5 × 106 Cd36NC or Cd36KO C1498-OVA cells were sacrificed 18 days after injection. Leukemia cells (G), tetramer+ T cells (H), and the expression of activation (I) or inhibitory (J) markers in tetramer+ T cells in spleen were examined. (K) CD8+ T cells purified from GFP− splenocytes of the recipients were further used for T cell killing assay.

(L) C1498 cells (5 × 105 cells per mouse) were subcutaneously implanted into C57BL/6 mice. Meanwhile, spleen T cells (3 × 106 cells per mouse) from naive mice or Cd36KO C1498 cell-challenged mice were adoptively transferred into these mice, respectively (n = 5 per group). Tumor size was monitored. Arrow indicates the day of rechallenge in 3 mice that had eliminated leukemia with a higher number of C1498 cells (1 × 106 cells per mouse).

(M) CD36NC and CD36KO MV4-11 cells were used for CFSE assay. The percentages of proliferating T cells were determined by CFSE dilution (n = 3).

(N and O) Different kinds of MV4-11 cells (N) or C1498 cells (O) were used for T cell proliferation assay. T cells were counted after co-culture (n = 3).

Data are shown as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. ns, not significant.

Then, we cultured CD36NC or CD36KO MV4-11 cells together with human T cells in vitro and conducted carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dilution assay. CFSE+ T cell proliferation was recovered by CD36 KO (Figure 1M). When MV4-11 cells and T cells were cultured in separate Transwells, CD36 KO still increased the number of T cells (Figure 1N). Likewise, C1498 cells with OE Cd36, but not those with the OE Cd36 mutant, had an increased ability to suppress mouse T cells (Figure 1O). These results indicate that CD36 on AML cells directly suppresses T cell proliferation.

CD36 on AML cells mediates T cell suppression independently of FAO

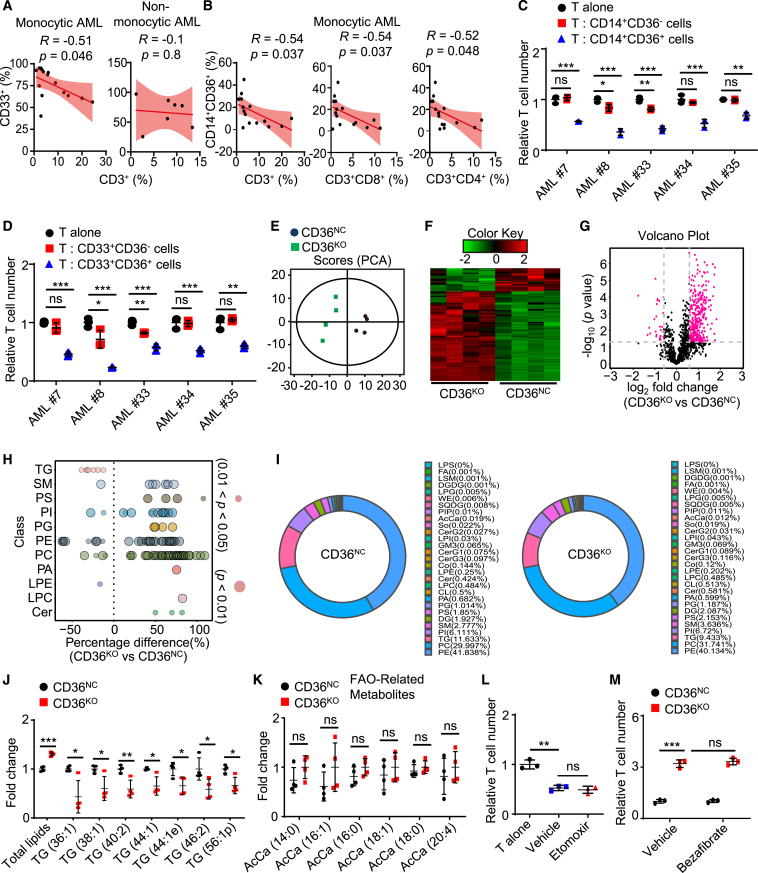

Monocytic AML (French-American-British M4 and M5 subtypes) suppresses T cell function,36 and, consistently, we noticed that monocytic AML showed high expression of CD36 in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort (Figure S2A). Flow cytometry analysis of BMMCs from 22 patients confirmed that the frequency of CD33+ AML cells was negatively correlated with the frequency of CD3+ T cells in monocytic AML (R = −0.51, p = 0.046) but not in non-monocytic AML (Figure 2A). Moreover, in monocytic AML, the frequency of CD14+CD36+ AML cells, but not that of CD14+CD36− AML cells or other AML cells, was negatively correlated with the frequency of CD3+ T cells (R = −0.54, p = 0.037) (Figures 2B and S2B). Further, the frequency of CD14+CD36+ AML cells was negatively correlated with the frequency of CD3+CD4+ T cells (R = −0.52, p = 0.048) and CD3+CD8+ T cells (R = −0.54, p = 0.037) but not with the frequency of CD3−CD56+ NK cells (Figures 2B and S2C). Then, we sorted CD14+CD36+ cells, CD14+CD36− cells, CD33+CD36+ cells, and CD33+CD36− cells from 5 patients with monocytic AML and cultured them with autologous T cells. CD14+CD36+ cells and CD33+CD36+ cells, but not CD14+CD36− cells or CD33+CD36− cells, substantially suppressed T cell proliferation (Figures 2C and 2D). These data suggest that CD36 preferentially expressed on monocytic AML cells causes T cell suppression.

Figure 2.

CD36 on AML cells mediates T cell suppression independently of FAO

(A and B) Flow cytometry analysis of the BMMCs from 15 patients with monocytic or 7 non-monocytic AML. Scatterplot showing the correlations between different cell types.

(C and D) Different kinds of AML cells sorted from 5 patients with monocytic AML were used for T cell proliferation assay.

(E–K) Principal-component analysis (E), heatmap (F), volcano plot (G), bubble plot (H), pie chart (I), and representative lipids altered (J and K) showing the changes of lipidome in CD36NC and CD36KO MV4-11 cells (n = 4).

(L and M) MV4-11 cells stimulated with etomoxir (50 μM) or bezafibrate (5 μM) for 3 days were further used for T cell proliferation assay (n = 3).

Data are shown as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. ns, not significant.

As reported previously,18,27 we found that a BCL-2 inhibitor (ABT-737) and cytarabine (Ara-C), but not an HMA drug (decitabine), synergized with CD36 depletion to reduce the growth of AML cells in vitro (Figures S2D–S2F), and these synergistic anti-AML effects disappeared under the inhibitor of CPT1A (etomoxir), a rate-limiting enzyme for FAO (Figures S2G and S2H), confirming a role for the CD36-FAO axis in promoting the survival of AML cells under stress.18,27 However, we found that the expression of CPT1A was low in monocytic AML and was positively correlated with the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in patients with AML (R = 0.32, p < 0.001) (Figures S2I and S2J). Spectrometry-based lipidomics showed that CD36 KO markedly altered the cellular lipid composition in MV4-11 cells (Figures 2E–2G). Specifically, CD36 KO increased the levels of total lipids, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, ceramides, and sphingomyelins, as well as decreased the level of triglycerides (Figures 2H–2J). In contrast, CD36 KO did not affect the concentrations of a series of FAO-related metabolites (acyl carnitine) (Figure 2K). Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and subsequent analysis using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) showed that CD36 KO downregulated pathways involved in innate immune and inflammatory signaling but did not affect lipid-oxidation-related programs in MV4-11 cells (Figures S2K and S2L). Pre-treating MV4-11 cells with an FAO inhibitor did not affect their ability to suppress T cell proliferation (Figure 2L), and conversely, pre-treatment with bezafibrate, an FAO agonist, failed to restore the immune inhibitory effects of CD36KO MV4-11 cells (Figure 2M). These results indicate that CD36 on AML cells mediates T cell suppression independently of FAO.

OxLDL and palmitate synergize to suppress T cell activity via CD36-mediated innate immune signaling in AML cells

On the basis of our aforementioned findings (Figure S2L), we postulated that CD36 mediated T cell suppression by activating signaling. APOC2-CD36 autocrine signaling promotes AML progression.33 However, we found that Apoc2 KO delayed AML progression in a T cell-independent manner (Figures S3A and S3B). CD36-mediated OxLDL uptake activates lipid-peroxidation-mediated signaling as well as Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated signaling.22,29 We found, using fluorescently conjugated OxLDL and flow cytometry, that CD34+ cells from 6 patients with AML displayed a 4- to 6-fold increase in OxLDL transport rate relative to CD34+ cord blood cells, and the uptake of OxLDL was far less efficient in SSO-treated AML cells than in vehicle-treated AML cells (Figures S3C and S3D). We cultivated THP-1 cells, another human monocytic AML cell line, in complete medium (CM), lipid-deprived medium (LDM), or LDM supplemented with OxLDL or other lipid species, including LDL, high-density lipoprotein, palmitate, arachidonic acid, and oleic acid, for 3 days before co-culture with human T cells. After co-culture, T cell counting showed that the ability to suppress T cell proliferation was low in THP-1 cells pre-treated with LDM compared with those cultured in CM, and inhibition of T cell proliferation could be restored by LDM supplemented with OxLDL but not by LDM supplemented with other lipids (Figures 3A and S3E). Interestingly, LDM supplemented with OxLDL and palmitate further increased the immunosuppressive function of THP-1 cells compared with LDM supplemented with OxLDL alone (Figure 3A), whereas LDM supplemented with OxLDL and other FAs failed to do this (Figure S3F). Likewise, pre-treating CD36NC MV4-11 cells, but not CD36KO MV4-11 cells, with OxLDL and palmitate resulted in synergistic inhibition of T cell proliferation (Figure 3B). These data show that OxLDL and palmitate synergize to suppress T cell activity via CD36.

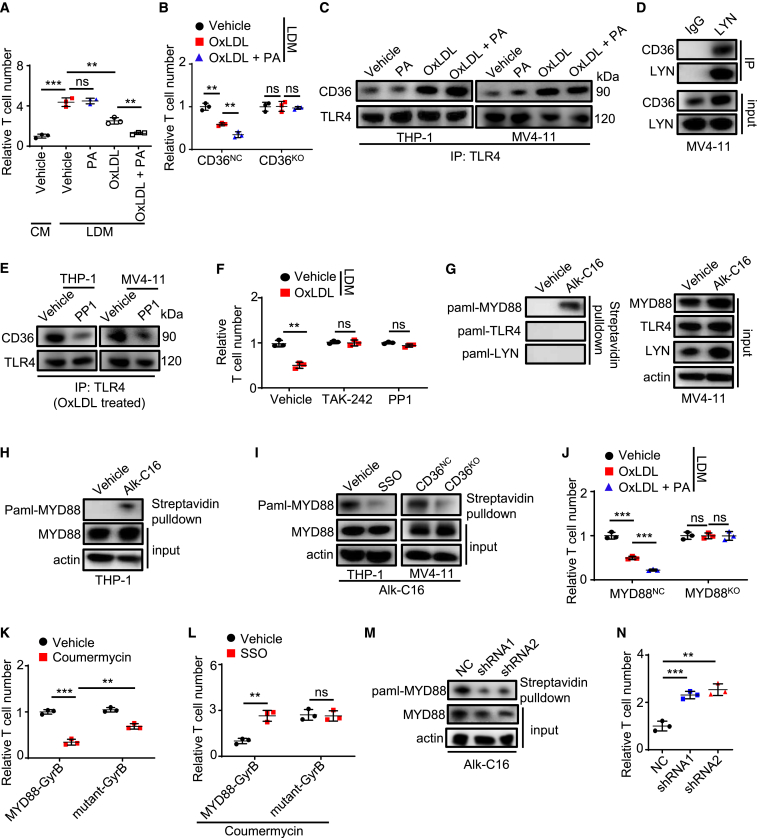

Figure 3.

OxLDL and PA synergize to suppress T cell activity via CD36-mediated innate immune signaling in AML cells

(A and B) THP-1 cells (A) or MV4-11 cells (B) stimulated in CM or LDM supplied with different lipids (palmitate [PA], 20 μM; OxLDL, 25 μg/mL) for 3 days were further used for T cell proliferation assay (n = 3).

(C–E) Immunoblot analysis of TLR4 (C and E) or LYN (D) precipitated proteins. (C and E) AML cells were treated with different reagents (PA, 20 μM; OxLDL, 25 μg/mL; PP1, 10 μM) for 5 h before immunoprecipitation.

(F) MV4-11 cells treated with LDM supplied with different reagents (OxLDL, 25 μg/mL; TAK-242, 10 μM; PP1, 10 μM) for 3 days were further used for T cell proliferation assay (n = 3).

(G–I) AML cells labeled with a chemical probe (alk-C16) for 4 h in the absence (G and H) or presence of SSO (50 μM) (I) were used for palmitoylation assay.

(J) MYD88NC or MYD88KO MV4-11 cells stimulated in LDM supplied with different lipids (PA, 20 μM; OxLDL, 25 μg/mL) for 3 days were further used for T cell proliferation assay (n = 3).

(K and L) MYD88-GyrB or MYD88 mutant-GyrB MV4-11 cells stimulated with different reagents (coumermycin, 1 ng/mL; SSO, 50 μM) for 3 days were further used for T cell proliferation assay (n = 3).

(M and N) ZDHHC6NC or ZDHHC6KD MV4-11 cells were used for MYD88 palmitoylation assay (M) or T cell proliferation assay (n = 3) (N).

Data are shown as mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. ns, not significant.

We next explored the downstream signaling of OxLDL. Expression of the lipid peroxidation suppressor GPX4 was high in monocytic AML (Figure S3G), and treatment with the antioxidant vitamin E (α-tocopherol) did not affect the ability of lipid-stimulated MV4-11 cells to suppress T cell proliferation (Figure S3H), excluding the involvement of lipid-peroxidation-mediated signaling. The TLR pathway was downregulated in CD36KO MV4-11 cells (Figure S2L) and was enriched in patients with AML with CD36 high expression (Figure S3I). Immunoprecipitation (IP) assay showed that the association of CD36 and TLR4, which was also highly expressed on AML cells (Figure S3J), was enhanced by OxLDL but not by palmitate (Figure 3C). Palmitate failed to further enhance this association caused by OxLDL (Figure 3C). The activation of TLR4 requires LYN,29 and we found that LYN interacted with CD36 in AML cells (Figure 3D). The LYN inhibitor PP1 decreased the OxLDL-induced association of TLR4 and CD36 (Figure 3E). Moreover, when pre-treated with PP1 or the TLR4 inhibitor TAK-242, OxLDL-simulated MV4-11 cells failed to suppress T cell proliferation (Figure 3F). We further determined that the CD36 expression was strongly correlated with the expression of TLR4 (R = 0.57, p < 0.001) and LYN (R = 0.51, p < 0.001) in AML in TCGA database (Figure S3K). Collectively, these results indicate that OxLDL triggers the formation of the CD36-LYN-TLR4 complex in AML cells, which suppresses T cell proliferation.

Post-translational S-palmitoylation affects signaling transduction as well as leukemogenesis,37,38,39 which prompted us to test whether palmitate enhanced CD36 signaling through palmitoylation. We employed a Click-iT assay in which alkynyl palmitate (alk-C16) was incorporated into cultured AML cells, followed by protein labeling with biotin azide. Streptavidin pull-down and immunoblot analysis showed that the TLR signaling transducer MYD88, whose expression was correlated with the expression of CD36 in AML (R = 0.54, p < 0.001) (Figure S3L), but not TLR4 or LYN, was labeled by the palmitoylation probe (Figures 3G and 3H). MYD88 palmitoylation was decreased after CD36 inhibition and was not induced by OxLDL (Figures 3I and S3M). MV4-11 cells, which showed no dependence on MYD88 in DepMap, were then engineered to knock out MYD88 using CRISPR-Cas9 (Figures S3N and S3O). The addition of lipids to LDM enhanced the ability of MYD88NC MV4-11 cells to suppress T cell proliferation but had no effect on MYD88KO MV4-11 cells (Figure 3J). Then, we generated MYD88KO MV4-11 cells stably expressing a fusion protein comprising a MYD88C133A mutant, which impairs the palmitoylation of MYD88,40 and a subunit of Escherichia coli DNA gyrase (MYD88 mutant-GyrB). As a control, a fusion protein comprising MYD88 and GyrB (MYD88-GyrB) was also generated in MYD88KO MV4-11 cells. These fusion proteins dimerize only upon binding with coumermycin,41,42 thereby eliciting the TLR signal to bypass TLR4. Coumermycin enhanced the ability of MYD88-GyrB MV4-11 cells to suppress T cell proliferation, and this effect was completely blocked by novobiocin, a competitive inhibitor of coumermycin, confirming that this system did not trigger non-specific activation (Figure S3P). Under coumermycin treatment, MV4-11 cells expressing MYD88 mutant-GyrB showed a decreased ability to inhibit T cells compared with those expressing MYD88-GyrB (Figure 3K). In addition, CD36 inhibition decreased the immune inhibitory capacity of MV4-11 cells expressing MYD88-GyrB but not those cells expressing MYD88 mutant-GyrB (Figure 3L), implicating MYD88 palmitoylation as a downstream event regulated by CD36.

ZDHHC6, which is the major palmitoyl acyltransferase that targets MYD88,40 interacted with MYD88 in AML cells (Figure S3Q), and ZDHHC6 knockdown by short-hairpin-mediated RNA reduced MYD88 palmitoylation and decreased the ability of MV4-11 cells to suppress T cell proliferation (Figures 3M, 3N, S3R, and S3S). Although endogenous palmitate promotes MYD88 palmitoylation,40 inhibiting FASN, a rate-limiting enzyme for endogenous palmitate synthesis, with C75 only affected the immunosuppressive function of MV4-11 cells in the absence of exogenous palmitate (Figure S3T). These data indicate that palmitate uptake via CD36 facilitates ZDHHC6-mediated MYD88 palmitoylation, which contributes to the immunosuppressive effect of AML cells.

CD36 upregulates NF-κB signaling and expression of PD-L1 and ARG1 to suppress T cell activity

One major downstream pathway of MYD88 is NF-κB signaling.40 We found that CD36 KO downregulated the NF-κB pathway and the level of phosphorylated-p65 (p-p65) in AML cells (Figures 4A and S2L), and the NF-κB pathway was enriched in patients with AML with high CD36 expression (Figure S4A). The addition of lipids to LDM enhanced the ability of vehicle-treated-MV4-11 cells to suppress T cell proliferation but had no effect on NF-κB inhibitor (SC75741)-treated MV4-11 cells (Figure 4B). Likewise, CD36 KO or MYD88 KO did not affect the immunosuppressive function of MV4-11 cells in the presence of SC75741 (Figures 4C and 4D). We transduced OE Cd36 C1498 cells with a construct to express the dominant-negative form of IκBα (OE Cd36IκB-SR), which is a repressor of NF-κB signaling.43 As expected, p65 was sequestered within the cytoplasm in OE Cd36IκB-SR cells (Figure S4B), and OE Cd36IκB-SR blocked the accelerated AML progression caused by OE Cd36 in a T cell-dependent manner (Figure 4E), indicating that NF-κB acts as a major signal of this immunosuppressive axis.

Figure 4.

CD36 upregulates NF-κB signaling and expression of PD-L1 and ARG1 to suppress T cell activity

(A) The expression of p-p65 and p65 in Cd36NC and Cd36KO C1498 cells was detected by western blot.

(B) MV4-11 cells stimulated in LDM supplied with different reagents (PA, 20 μM; OxLDL, 25 μg/mL; SC75741, 5 μM) for 3 days were further used for T cell proliferation assay (n = 3).

(C and D) Different kinds of MV4-11 cells were used for T cell proliferation assay (n = 3). SC75741 (5 μM) was added.

(E) C57BL/6 mice (n = 8 per group) intravenously injected with different kinds of C1498 cells (2 × 106/mice) were treated with antibodies (150 μg/mouse, 3 times/week, i.p.) for 2 weeks after injection and were monitored for survival.

(F) Chromatin IP followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) occupancy profiles of p65 at PD-L1 gene locus in THP-1 cells.

(G and H) C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 per group) intravenously injected with 2 × 106 Cd36NC or Cd36KO C1498 cells were treated with or without antibodies (150 μg/mouse, 3 times/week, i.p.) for 2 weeks and were sacrificed 18 days after injection for analysis (G) or monitored for survival (H). (G) The expression of PD-L1 in BM C1498 cells was detected by flow cytometry.

(I) The expression of ARG1 in CD36NC and CD36KO MV4-11 cells was detected by flow cytometry (n = 3).

(J) CD36NC or CD36KO MV4-11 cells were used for T cell proliferation assay (n = 3). Nor-NOHA (0.5 mM) was added.

(K) Different kinds of AML cells sorted from 3 patients were probed for p-p65, PD-L1, and ARG1.

Data are shown as mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. ns, not significant.

The CD36 expression was positively correlated with the PD-L1 expression, which is an inhibitory checkpoint molecule regulated by NF-κB,44 in AML (R = 0.41, p < 0.001) but not in other cancers (Figure S4C). PD-L1 expression and the PD-1 checkpoint pathway were also enriched in patients with AML who highly expressed CD36 (Figure S4D). An analysis of published chromatin IP followed by sequencing data45 revealed a strong p65 binding site in the PD-L1 promoter in THP-1 cells (Figure 4F). Cd36 KO decreased the protein level of PD-L1 in C1498 cells, as well as attenuated anti-PD-L1 antibody-mediated survival prolongation of AML mice (Figures 4G and 4H). ARG1 secretion is regulated by NF-κB and is known to suppress T cell activity.46 Indeed, CD36 KO downregulated the expression of ARG1 in MV4-11 cells (Figure 4I), and the ARG1 inhibitor Nor-NOHA was unable to decrease the ability of MV4-11 cells to inhibit T cells when CD36 was depleted (Figure 4J). Accordingly, CD33+CD36+ human AML cells displayed a 1.8- to 3-fold increase in the protein levels of p-p65, PD-L1, and ARG1 relative to CD33+CD36− human AML cells (Figure 4K). These data show that NF-κB-dependent expressions of PD-L1 and ARG1 promote the immunosuppressive activity of CD36-expressing AML cells.

Lipid deprivation by statin targets CD36 to delay AML progression

A high-fat diet (HFD) increases the levels of OxLDL and palmitate in the serum of mice.47 Thus, we postulated that an HFD may accelerate AML progression by enhancing CD36 pathway. To test this hypothesis, we fed C57BL/6 mice with an HFD or a standard control diet (CD) for 12 weeks (Figure S5A) and found that HFD-fed mice showed faster AML progression in different organs and shorter survival time than CD-fed mice (Figures S5B–S5D), whereas Cd36 KO blocked the accelerated AML progression caused by the HFD (Figure S5E). Notably, under conditions of CD36 KO, the survival times of CD-fed and HFD-fed AML mice were similarly shortened when T cells were depleted (Figure S5E), demonstrating that the accelerated AML progression caused by the HFD depends on CD36-mediated T cell suppression.

Fluvastatin, which can decrease OxLDL levels in the serum of HFD-fed mice,48 impedes leukemic progression by targeting 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR) in AML cells.49 However, we found that fluvastatin showed the anti-AML effects in HFD-fed mice transplanted with HmgcrKO C1498 cells but not in those transplanted with Cd36KO C1498 cells (Figures 5A, S5F, and S5G). Moreover, fluvastatin showed no therapeutic effect on HFD-fed AML mice when T cells were absent (Figure 5B). Consistently, compared to NOG mice, the anti-AML effects of fluvastatin were stronger in PBMC-NOG mice (Figures 5C and 5D). As expected, the tumor-infiltrating T cells or T cells in PB of PBMC-NOG mice were elevated by fluvastatin (Figures 5E and 5F). In a patient-derived xenograft model, fluvastatin also decreased the percentage of human CD33+ AML cells while expanding the population of engrafted human CD3+ T cells in the BM of the recipients (Figures 5G and 5H). These data suggest that targeting CD36 by statin delays AML progression.

Figure 5.

Statin delays AML progression by targeting CD36

(A and B) HFD C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 per group) intravenously injected with 1 × 106 Cd36NC or Cd36KO C1498 cells were treated with or without reagents (fluvastatin, 40 mg/kg, 5 times/week, intragastric [i.g.]; antibodies, 150 μg/mouse, 3 times/week, i.p.) for 2 weeks after injection and were monitored for survival.

(C–F) NOG mice (C) or PBMC-NOG mice (D–F) subcutaneously injected with 1 × 107 MV4-11 cells were treated with or without fluvastatin (40 mg/kg, 5 times/week, i.g.) for 2 weeks after injection (n = 5 per group). Tumor was monitored for 13 (C) or 28 days (D–F) after injection. (E) Tumors from 3 recipients were dissected for immunohistochemistry staining with anti-human CD3 antibody. Right corner images were magnified from the red highlighted region. Black arrowheads indicate CD3+ cells. Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) Quantification of human T cells in PB.

(G and H) NOG mice (n = 5 per group) intravenously implanted with 5 × 106 BMMCs from patients with AML were treated with or without fluvastatin (40 mg/kg, 5 times/week, i.g.) for 2 weeks starting 7 days after implantation. 3 days after the last treatment, percentages of human AML cells (G) and human T cells (H) in BM were tested.

Data are shown as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. ns, not significant.

Decitabine treatment enhances the CD36 immunosuppressive pathway in AML cells

A recent report shows that T cell function is inhibited in patients with AML who relapsed after HMA therapy.11 We tested whether CD36 played a role in this situation. We divided 8 AML cell lines into two groups according to their sensitivity to the HMA drug decitabine obtained from DepMap50 (Figures 6A and 6B) and found that decitabine-resistant cell lines (OCIAML3, THP-1, MV4-11, NOMO1) had higher CD36 mRNA and protein levels than decitabine-sensitive cell lines (U937, OCIAML2, MOLM-13, NB4) (Figures 6C and 6D). Moreover, decitabine elevated CD36 expression in AML cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 6E and 6F). As expected, SSO blocked the enhanced lipid uptake rate in AML cells caused by decitabine (Figures S6A and S6B). Given that the CD36 promoter was hypermethylated in AML in TCGA database (Figure 6G), we tested whether CD36 upregulation caused by decitabine may be associated with demethylation of the CD36 promoter. The high-throughput next-generation sequencing based on bisulfite sequencing PCR was employed. According to two CpG island locations in the CD36 promoter region reported previously,51,52 we designed two amplicons (amplicon 1, 323 bp; amplicon 2, 236 bp) and observed sharp reductions in CpG methylation levels in these amplicons that contained a total of 6 methylated positions in decitabine-treated AML cells (Figure 6H). The survival-prolonging effect of decitabine was attenuated in mice implanted with OE Cd36 cells compared with OE Ctrl cells (Figure 6I). When this experiment was repeated with HFD-fed mice, OE Cd36 resulted in nearly complete resistance to decitabine (Figure 6J), indicating that the enhancement of CD36 contributes to decitabine resistance in AML.

Figure 6.

AML cells enhance the CD36 immunosuppressive pathway in response to decitabine treatment

(A and B) Drug sensitivity AUC (area under the curve) values of decitabine in AML cell lines based on data from the Cancer Target Discovery and Development (CTD2) network.

(C and D) The mRNA (C) and protein (D) levels of CD36 in 4 decitabine-resistant and 4 decitabine-sensitive AML cell lines are shown.

(E and F) AML cells were stimulated with decitabine for 3 days. Then, the mRNA (E) and protein (F) levels of CD36 were determined (n = 3).

(G) CD36 promoter methylation profile based on the ages of patients with AML in TCGA database. The beta value indicates the level of DNA methylation, ranging from 0 (unmethylated) to 1 (fully methylated).

(H) AML cells stimulated with decitabine (4 μM) for 3 days were used for next-generation sequencing based on bisulfite sequencing PCR (n = 3). Heatmaps show the CpG methylation level at the promoter region of CD36. Two amplicons were used.

(I and J) HFD or CD C57BL/6 mice (n = 6 per group) intravenously injected with 1 × 106 different kinds of C1498 cells were treated with or without decitabine (0.4 mg/kg, 3 times/week, i.p.) for 2 weeks after injection and were monitored for survival.

(K) THP-1 cells were stimulated with decitabine for 3 days. Then, the protein levels of PD-L1 and ARG1 were detected by flow cytometry (n = 3).

(L) MV4-11 cells stimulated with decitabine (4 μM) for 3 days were further used for T cell proliferation assay (n = 3). Nor-NOHA (0.5 mM) was added.

(M) C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 per group) intravenously injected with 2 × 106 Cd36NC or Cd36KO C1498 cells were treated with different reagents (decitabine, 0.4 mg/kg, 3 times/week, i.p.; antibodies, 150 μg/mouse, 3 times/week, i.p.) for 2 weeks after injection and were monitored for survival.

(N and O) CD33+ cells from 12 patients with AML were stimulated with decitabine (4 μM) for 2 days. Then, the protein levels of ARG1, PD-L1, and CD36 were detected by flow cytometry.

(P) CD33+ cells from 6 patients with AML stimulated with or without decitabine (4 μM) or SSO (50 μM) for 3 days were further used for T cell proliferation assay (n = 3).

Data are shown as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. ns, not significant.

To understand the underlying mechanisms, we conducted RNA-seq of vehicle-treated and decitabine-treated THP-1 cells (Figure S6C). KEGG enrichment analysis showed that the NF-κB and TLR pathways were enhanced by decitabine (Figures S6D and S6E). GO enrichment analysis showed that FA binding, but not the lipid-oxidation-related gene sets, was activated by decitabine (Figures S6F and S6G). We obtained similar results when vehicle-treated and decitabine-treated MV4-11 cells were examined (Figures S6H–S6J). Moreover, the TLR, NF-κB, and PD-L1 pathways, but not the lipid-oxidation-related gene sets, were downregulated by CD36 KO under decitabine treatment (Figure S6K). Decitabine only induced a slight activation of the type I interferon pathway, which was observed in THP-1 cells but not in MV4-11 cells (Figures S6G and S6J). We verified that decitabine, but not other drugs, including a BCL-2 inhibitor, Ara-C, or doxorubicin, increased the protein levels of PD-L1 and ARG1 in THP-1 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 6K and S6L–S6N). As expected, the ARG1 inhibitor decreases the immunosuppressive potential of CD36NC MV4-11 cells, but not the CD36KO MV4-11 cells, under decitabine treatment (Figure 6L). Likewise, combined treatment with anti-PD-L1 antibody and decitabine showed a synergetic anti-AML effect on mice transplanted with Cd36NC C1498 cells but not on those transplanted with Cd36KO C1498 cells (Figure 6M). Decitabine treatment promoted CD36 expression in 8 of 12 AML samples, which were defined as responders (Figures 6N and 6O). Among these responders, decitabine also increased the levels of PD-L1 and ARG1 (Figures 6N and 6O). Accordingly, decitabine enhanced the ability of CD33+ AML cells sorted from 6 responders to suppress T cell activity, which was blocked by SSO treatment (Figure 6P). Together, our results demonstrate that decitabine enhances the CD36 immunosuppressive pathway in AML cells.

Statins improve the efficacy of decitabine therapy in AML

We tested whether statins could improve the efficacy of decitabine therapy in murine models. Fluvastatin and decitabine showed synergetic anti-AML effects on mice transplanted with Cd36NC C1498 cells but not on those transplanted with Cd36KO C1498 cells (Figure 7A) or on those transplanted with Cd36NC C1498 cells whose T cells were depleted (Figure 7B). Then, we used cell-line-derived xenograft models. Fluvastatin combined with decitabine strongly inhibited the growth of decitabine-resistant MV4-11 cells and restored the percentage of human T cells in PBMC-NOG mice (Figures 7C and 7D). Moreover, the synergetic anti-AML effect of fluvastatin and decitabine was strong in the PBMC-NOG model but not in the NOG model established by THP-1 cells, another decitabine-resistant cell line (Figure 7E). These data suggest that statin improves the efficacy of decitabine therapy by targeting CD36.

Figure 7.

Statin combined with decitabine delays AML progression

(A and B) C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 per group) intravenously implanted with 2 × 106 Cd36NC or Cd36KO C1498 cells were treated with different reagents (decitabine [Dec], 0.4 mg/kg, 3 times/week, i.p.; antibodies, 150 μg/mouse, 3 times/week, i.p.; fluvastatin [Flu], 40 mg/kg, 5 times/week, i.g.) for 2 weeks after implantation and were monitored for survival.

(C–E) NOG or PBMC-NOG mice (n = 5 per group) subcutaneously injected with 1 × 107 MV4-11 cells (C and D) or THP-1 cells (E) were treated with different drugs (Dec, 0.4 mg/kg, 3 times/week, i.p.; Flu, 40 mg/kg, 5 times/week, i.g.) for 2 weeks after injection. Tumor size or human T cells in PB were monitored 13 (E) or 28 days (C and D) after injection.

(F–I) Response rates for selected subgroups (F and I) and blood lipid values for selected subgroups (H) were shown. (G) Odds ratios for achievement of CR estimated by multivariate analyses.

Data are shown as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. ns, not significant.

To understand the clinical relevance of our findings, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of 153 patients with AML who were treated with decitabine-based chemotherapy. The level of total cholesterol was positively correlated with the level of LDL-cholesterol in the serum of these patients (R = 0.41, p < 0.001) (Figure S7A). Of these patients, 9 had received a statin drug as background therapy (Figure S7B). First, we divided the 144 patients who had not been on statin therapy into a high blood fat group (n = 13) and a normal blood fat group (n = 131) according to the level of total cholesterol (Figure S7B). There was no significant difference in the baseline characteristics between these two groups (Table S1). After the first cycle of decitabine therapy, the overall response rate (ORR) and complete remission (CR) rate in patients with normal blood fat were 68.7% and 58.8%, respectively, compared with 38.5% and 23.1% (p = 0.068 and p = 0.016), respectively, for patients with high blood fat (Figure 7F). Moreover, patients with or without good cytogenetics had CR rates of 80% and 51.9% (p = 0.039), respectively (Figure S7C). Other variables were not associated with the CR rate (Figure S7C). Next, we conducted multivariate analysis and found that the corresponding multivariable odds ratio for CR was 4.661 (1.196, 18.161; p = 0.027), in favor of patients with normal blood fat (Figure 7G). These data suggest that high blood fat dampens the CR rate of decitabine therapy in AML.

As expected, patients with background statin use (n = 9) had lower levels of blood fat compared with patients with high blood fat who had not been on statin therapy (n = 13) (Figure 7H). There was no significant difference in the baseline characteristics between these two groups (Table S2), but patients with statin treatment had higher ORR (77.8%) and CR (77.8%) rates (p = 0.099 and p = 0.027) compared with patients without statin treatment (Figure 7I). These data suggest that statins improve the CR rate of decitabine therapy in AML with high blood fat.

Discussion

AML cells reprogram metabolic pathways to meet their bioenergetics and biosynthetic demands, which include modified lipid metabolic features. However, whether and how lipid metabolism regulates AML immunity is less addressed. In this work, we demonstrate that CD36 acts as signaling receptor in addition to its role as lipid transporter to promote T cell suppression activity of AML cells and consequently affects AML progression.

Previous reports show that CD36 activates lipid peroxidation in T cells or facilitates FAO in AML cells treated with drugs.18,22,27 Due to a low level of the FAO rate-limiting enzyme CPT1A and a high level of the lipid peroxidation suppressor GPX4 in monocytic AML cells, we found that CD36 activated signaling, but not the lipid oxidation program, to drive T cell suppression. Another report showed that Apoc2, another ligand of CD36, promoted AML progression.33 In our study, we found that Apoc2 did not affect the T cell suppression activity of AML cells. These studies suggest that the role of CD36 in AML cells is multifunctional and that the CD36-mediated downstream program depends on the lineage identity of AML cells, CD36 ligands, and the stresses AML cells face. CD36 is also expressed by immune cells. We did not explore the role of CD36 on these immune cells in AML in the present study.

Previously, it is hypothesized that palmitate is a TLR4 agonist.53 A recent paper showed that TLR4 is not a receptor for palmitate but mediates palmitate-induced signaling, leaving the responsible mechanisms unclear.54 We showed that OxLDL primed TLR4-MYD88 signaling by binding to CD36, while palmitate uptake via CD36 further facilitated TLR4-MYD88 signaling by MYD88 palmitoylation. Our discoveries provided a mechanistic explanation for how exogenous palmitate is involved in TLR4 signaling. Although MYD88 requires endogenous-palmitate-dependent palmitoylation,40 we observed that the inhibition of endogenous palmitate synthesis affected AML cells cultured without exogenous palmitate. Thus, MYD88 palmitoylation in AML cells may favor reliance on CD36-dependent exogenous palmitate uptake over de novo palmitate synthesis. Nevertheless, when exogenous palmitate is absent, de novo palmitate synthesis acts as a backup mechanism to maintain the MYD88 palmitoylation. However, whether this CD36-dependent synergistic signaling model reported in our study also applies to other CD36-expressing cells needs further study.

HMAs evoke cGAS-mediated or MDA5-mediated signaling in cancer cells, leading to enhanced immunogenicity of cancer cells.7,8 However, the clinical efficacy of HMA monotherapy has been limited. We demonstrated that decitabine promoted immune evasion by upregulating the CD36-TLR4 axis in AML cells. Thus, HMA treatment may act as a double-edged sword, providing anti-tumor effects while also inducing immunosuppressive pathways to dampen efficacy. Studies have shown limited clinical benefit from combination therapy with HMAs and anti-PD-L1 drugs in human AML.13 We consider that multiple immunosuppressive mechanisms are activated in human AML under HMA treatment. As such, PD-L1-targeting therapy is not enough to reverse the immunosuppressive microenvironment. In our study, CD36 also increased the expression of ARG1 to evade HMA therapy. Thus, targeting CD36 combined with HMAs may be more effective than anti-PD-L1 drugs combined with HMAs. The short half-life of CD36 antibodies limits their potential clinical application.23,33 In contrast, statins have been prescribed to millions of patients over close to three decades.55 Here, we showed that combined treatment with statin and decitabine exerted a strong anti-AML effect by blocking CD36. A retrospective analysis of our single-center clinical study also supported that background statin use improved the decreased CR rate caused by high blood fat in patients with AML. However, clinical data from larger cohorts are needed to further verify this. Moreover, besides CD36, the leukocyte Ig-like receptor subfamily B (LILRBs) are reported to inhibit T cell anti-tumor responses through activating NF-κB in AML cells.56 Given that AML cells may maintain NF-κB signaling by different ways, targeting both LILRBs and CD36 is needed to block immune evasion in treating human AML.

Limitations of the study

Because CD36 is also expressed by immune cells, CD36 conditional KO mice are needed to further test the role of CD36 in the AML microenvironment. Besides, probably due to a limited cohort size, we did not observe significant differences in progression-free survival and overall survival among patients with normal blood fat, patients with high blood fat, and patients with background statin use in retrospective analysis. Clinical data from larger cohorts are needed to further verify the independent prognostic and predictive values of this lipid-CD36 axis.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3033S; RRID: AB_331284 |

| NF-κB p65 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 8242S; RRID: AB_10859369 |

| β-Actin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3700S; RRID: AB_2242334 |

| MYD88 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4283S; RRID: AB_10547882 |

| LYN | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2796S; RRID: AB_2138391 |

| Lamin-B1 | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-374015; RRID: AB_10947408 |

| MYD88 | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-74532; RRID: AB_1126429 |

| TLR4 | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-293072; AB_10611320 |

| LYN | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-7274; AB_627897 |

| Normal mouse IgG | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-2025; AB_737182 |

| CD36 | Abcam | Cat# ab133625; RRID: AB_2716564 |

| ZDHHC6 | Abcam | Cat# ab121423; RRID: AB_11129943 |

| CD3 | Abcam | Cat# ab135372; RRID: AB_2884903 |

| TLR4 | CUSABIO Technology | Cat# CSB-PA001434 |

| InVivoPlus anti-mouse NK1.1 | BioXcell | Cat# BE0036; RRID: AB_1107737 |

| InVivoMab anti-mouse CD8β | BioXcell | Cat# BE0223; RRID: AB_2687706 |

| anti-mouse CD4 | BioXcell | Cat# BP0003-1; RRID: AB_1107636 |

| InVivoPlus anti-mouse PD-L1 | BioXcell | Cat# BP0101; RRID: AB_10949073 |

| InVivoPlus mouse IgG2a | BioXcell | Cat# BE0085; RRID: AB_1107771 |

| InVivoPlus rat IgG1 | BioXcell | Cat# BE0088; RRID: AB_1107775 |

| InVivoPlus rat IgG2b | BioXcell | Cat# BP0090; RRID: AB_1107780 |

| Phospho-NFκB p65 (Ser529) Antibody, PE | Invitrogen | Cat# MA5-37165; RRID: AB_2897099 |

| Arginase 1 Antibody, APC | Invitrogen | Cat# 17-3697-80; RRID: AB_2734834 |

| Anti-human PD-L1-PE-Cy7 | Invitrogen | Cat# 25-5983-41; RRID: AB_1907369 |

| Anti-mouse PD-1-BV785 | BioLegend | Cat# 135225; RRID: AB_2563680 |

| Anti-mouse LAG-3-BV785 | BioLegend | Cat# 125219; RRID: AB_2566571 |

| Anti-human PD-1-PE-Cy7 | BioLegend | Cat# 329917; RRID: AB_2159325 |

| Anti-human CD8-FITC | BioLegend | Cat# 344704; RRID: AB_1877178 |

| Anti-human CD14-BV421 | BioLegend | Cat# 301830; RRID: AB_10959324 |

| Anti-mouse TIM3-PE | eBioscience | Cat# 12-5870-82; RRID: AB_465974 |

| OVA257-264 (SIINFEKL) peptide bound to H-2Kb Antibody, APC | eBioscience | Cat# 17-5743-80; RRID: AB_1311288 |

| Anti-mouse CD36-APC | eBioscience | Cat# 17-0362-82; RRID: AB_2734967 |

| Anti-mouse PD-L1-PE-Cy7 | eBioscience | Cat# 25-5982-82; RRID: AB_2573509 |

| Anti-human TLR4-APC | eBioscience | Cat# 17-9917-41; RRID: AB_2016622 |

| Anti-mouse CD107a-BV421 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 564347; RRID: AB_2738760 |

| Anti-human CD33-BV421 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562854; RRID: AB_2737405 |

| Anti-human CD36-APC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 561822; RRID: AB_398480 |

| Anti-human CD36-FITC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555454; RRID: AB_2291112 |

| Anti-human CD34-FITC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555821; RRID: AB_396150 |

| Anti-human CD34-APC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 561209; RRID: AB_10683161 |

| Anti-human CD45-APC-Cy7 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 557833; RRID: AB_396891 |

| Anti-human CD56-PE-Cy5 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555517; RRID: AB_395907 |

| Anti-human CD4-BV421 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562424; RRID: AB_11154417 |

| Anti-human CD4-PE | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555347; RRID: AB_395752 |

| Anti-human CD3-PE | BD Biosciences | Cat# 566683; RRID: AB_2744380 |

| Anti-human CD3-PE-Cy7 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 557749; RRID: AB_396855 |

| Anti-human CD3-APC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555342; RRID: AB_398592 |

| Anti-human CD3-PerCP | BD Biosciences | Cat# 552851; RRID: AB_394492 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Human samples | Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital | N/A |

| Human samples | Ruijin Hospital | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Human IL-3 | PEPROTECH | Cat# 200-03 |

| Human IL-6 | PEPROTECH | Cat# 200-06 |

| Human SCF | PEPROTECH | Cat# 300-07 |

| Human TPO | PEPROTECH | Cat# 300-18 |

| Human IL-2 | R&D Systems | Cat# BT-002 |

| Mouse IL-2 | R&D Systems | Cat# 402-ML |

| APC-conjugated H-2Kb OVA Tetramer-SIINFEKL | MBL | Cat# TS-5001-2C |

| Protease inhibitor cocktail | Selleck | Cat# B14001 |

| Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail | Selleck | Cat# B15001 |

| Sulfosuccinimidyl oleate | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-112847 |

| SC75741 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-10496 |

| Fluvastatin | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-14664 |

| C75 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-12364 |

| Bezafibrate | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-B0637 |

| Etomoxir | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-50202 |

| ABT-737 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-50907 |

| Cytarabine | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-13605 |

| Coumermycin A1 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-N7452 |

| Novobiocin | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-B0425A |

| TAK-242 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-11109 |

| PP1 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-13804 |

| Decitabine | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-A0004 |

| α-Tocopherol | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-N0683 |

| Busulfan | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-B0245 |

| Nor-NOHA | ApexBio Technology | Cat# C5407 |

| OxLDL | Solarbio | Cat# IL2150 |

| LDL | Solarbio | Cat# IL2110 |

| HDL | Solarbio | Cat# IL2130 |

| Palmitate | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 10006627 |

| Oleic acid | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 90260 |

| Arachidonic Acid | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 90010 |

| CFSE | Biolegend | Cat# 423801 |

| SIINFEKL peptide | Nanjing Peptide Biotech | N/A |

| alkynyl palmitate | click chemistry tools | Cat# 1165 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| StemSpan SFEM II | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat# 09605_C |

| EasySep Human Cord Blood CD34 Positive Selection Kit III | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat# 17897 |

| Protein Enrichment Kit for capture of alkyne-modified proteins | click chemistry tools | Cat# 1441 |

| Fatty Acid Uptake Assay Kit | Abnova | Cat# KA4084 |

| Oxidized LDL Uptake Assay Kit | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 601180 |

| Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit | Sangon Biotech | Cat# C510001 |

| Pan T cell Isolation Kit, human | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-096-535 |

| Pan T cell Isolation Kit II, mouse | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-095-130 |

| Mouse CD8+ T cell Isolation Kit | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat# 19853 |

| T cell Activation/Expansion Kit, mouse | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-093-627 |

| T cell Activation/Expansion Kit, human | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-091-441 |

| Deposited data | ||

| ChIP-seq data of p65 | Lin et al.45 | GSE103477 |

| RNA-seq data of CD36KO vs. CD36NC MV4-11 cells | This paper | GSE209783 |

| RNA-seq data of decitabine-treated vs. untreated THP-1 cells | This paper | GSE200510 |

| RNA-seq data of decitabine-treated vs. untreated MV4-11 cells | This paper | GSE225384 |

| RNA-seq data of AML patients | Li et al.34 | GSE37642 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| MV4-11 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-9591 |

| HEK-293T | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3216 |

| MOLM-13 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC 544 |

| OCIAML2 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC 99 |

| OCIAML3 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC 582 |

| NOMO1 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC 542 |

| SET2 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC 608 |

| U937 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1593.2 |

| C1498 | ATCC | Cat# TIB-49 |

| THP-1 | ATCC | Cat# TIB-202 |

| NB4 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC 207 |

| K-562 | ATCC | Cat# CCL-243 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Sug/JicCrl (NOG) mice | Vital River | Cat# 408 |

| C57BL/6JNifdc mice | Vital River | Cat# 219 |

| NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1SugB2mem1TacH2-Ab1tm1Doi/JicCrl (NOG-dKO) mice | Vital River | Cat# 411 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| shRNA sequences | This paper | Table S4 |

| sgRNA sequences | This paper | Table S4 |

| primers used for RT-PCR | This paper | Table S4 |

| primers used for NGS-BSP | This paper | Table S4 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pMD2.G | Addgene | Cat# 12259 |

| psPAX2 | Addgene | Cat# 12260 |

| LentiGuide Puro-P2A-EGFP | Addgene | Cat# 137729 |

| lentiCas9-Blast | Addgene | Cat# 52962 |

| pLKO.5 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# SHC201 |

| pLV-EF1a-IRES-Neo | Addgene | Cat# 85139 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Graphpad Prism v8 | Graphpad Prism | https://www.graphpad-prism.cn/?c=i&a=prism |

| Flowjo v10 | Flowjo | https://www.flowjo.com |

| Depmap portal | Barretina et al.50 | https://depmap.org/portal |

| SPSS Version 20 | IBM SPSS | https://www.ibm.com/cn-zh/spss |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Shi Jun (junshi@sjtu.edu.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

The RNA-seq data and ChIP-seq data were obtained from the GEO (GSE103477 and GSE37642). Other RNA-seq data analyzed in this study have been deposited at GEO (GSE209783, GSE200510, and GSE225384). They are publicly available at the time of publication and are listed in the key resources table. Freely available software and algorithms used for analysis are also listed in the key resources table. Original western blot images and microscopy data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Cell lines and cell culture

MV4-11 (ATCC, CRL-9591), MOLM-13 (DSMZ, ACC 554), OCIAML2 (DSMZ, ACC 99), OCIAML3 cells (DSMZ, ACC 582), NOMO1 (DSMZ, ACC 542), SET2 (DSMZ, ACC 608), U937 (ATCC, CRL-1593.2), C1498 (ATCC, TIB-49), THP-1 (ATCC, TIB-202), NB4 (DSMZ, ACC 207), and K-562 (ATCC, CCL-243) were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco). HEK-293T were cultured in DMEM (Gibco). All media were supplemented with 1% Glutamax (Gibco), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), 10% FBS (Gibco). In some experiments, 10% lipid-deprived FBS (PAN biotech, P30-3402) were used. All cell lines were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All cell lines were validated via short tandem repeat profiling prior to use. All cells were routinely tested for Mycoplasma (Universal Mycoplasma Detection Kit, ATCC, 30-1012K).

Human samples

Human samples were obtained after receiving informed consents from AML patients and healthy donors admitted to the Department of Hematology in Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital and Ruijin Hospital according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Human Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital approved the protocol for the recruitment of AML patients and healthy volunteers (SH9H-2022-T226-2). Human primary AML samples and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy donors were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. Healthy human CD34+ cells were isolated using EasySep Human Cord Blood CD34 Positive Selection Kit III (STEMCELL Technologies). Then, these samples were frozen in FBS (Gibco) with 10% DMSO and stored in liquid nitrogen. Primary human AML samples were culture in StemSpan SFEM II (STEMCELL Technologies) supplemented with 20 ng/mL human IL-3, 10 ng/mL human IL-6, 100 ng/mL human SCF, 50 ng/mL human TPO (all from Peprotech), and 1% Glutamax (Gibco). Primary leukemic samples used in different experiments were summarized in Table S3.

Mice model

C57BL/6JNifdc mice, NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Sug/JicCrl (NOG) mice, and NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1SugB2mem1TacH2-Ab1tm1Doi/JicCrl (NOG-dKO) mice were purchased from Charles River and maintained at Shanghai Branch of Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technologies Co. Ltd. For each experiment, the same gender- and age-matched mice were used and randomly allocated to each group. For the subcutaneous tumor model, the tumor size was calculated as (width × width × length) cm3. The maximal tumor measurement was 2 cm in diameter. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines provided by Shanghai Branch of Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technologies Co. Ltd (P2019091).

For mouse AML allograft, 6-8-week-old wild-type C57BL/6 mice or NOG mice were used for transplantation. Mouse C1498 cells were resuspended in 50–200 μL PBS for each mouse for intravenous or subcutaneous implantation. For subcutaneously implanted mice, tumor sizes were determined by caliper measure. For survival curve experiments, death was recorded when moribund animals were euthanized. For high-fat diet model, C57BL/6 mice were fed a high-fat diet (D12492, 60 kcal% fat, Research Diets) and the control group (age-matched mice) was fed a standard diet for 12 weeks. To determine whether CD36 knockout generated tumor-specific memory T cells, spleen T cells from Cd36KO C1498 cell-challenged mice or from naive mice were isolated by using mouse T cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Then, we conducted adoptive transfer of spleen T cells (3 × 106 cells per mouse) from Cd36KO C1498 cell-challenged mice into normal recipients C57BL/6 mice. Three out of five transplanted mice rejected C1498 cells (5 × 105 cells per mouse), and these mice further resisted to rechallenge with higher numbers (1 × 106 cells per mouse) of C1498 cells. Of five mice that received adoptive transfer of spleen T cells (3 × 106 cells per mouse) from naive mice, none rejected C1498 cells (5 × 105 cells per mouse). For antibody treatment, the isotype control antibody, anti-CD8 antibody, anti-NK1.1 antibody, anti-CD4 antibody, or anti-PD-L1 antibody (150 μg/each mouse, 3 times/week, i.p.) were injected for two continuous weeks after leukemic cells implantation. For drug treatment, fluvastatin (40 mg/kg, 5 times/week, i.g.), or decitabine (0.4 mg/kg, 3 times/week, i.p.) were injected for two continuous weeks after leukemic cells implantation.

For human AML xenografts, 6-8-week-old NOG mice or NOG-dKO mice were used for transplantation. 1 × 107 MV4-11 cells or THP-1 cells were resuspended in 50–100 μL PBS for each mouse for subcutaneous implantation. Tumor sizes were determined by caliper measure. For the human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMC)-humanized model, 1 × 107 hPBMCs were injected intravenously into each NOG-dKO mouse. Three weeks after implantation, mice had 70% engraftment of human T cells. Then, 1 × 107 MV4-11 cells or THP-1 cells were subcutaneously implanted. Tumor sizes were determined by caliper measure. For drug treatment, fluvastatin (40 mg/kg, 5 times/week, i.g.), or decitabine (0.4 mg/kg, 3 times/week, i.p.) were injected for two continuous weeks after leukemic cells implantation. For primary PDXs, each NOG mouse was sublethally pretreated with busulfan (30 mg/kg/day). One day later, 5 × 106 primary bone marrow mononuclear cells from AML patients, which contain leukemia cells and other normal compartments such as normal haematopoietic stem progenitor cells and autologous T cells were injected intravenously into each NOG mice followed by treatment with vehicle or fluvastatin (40 mg/kg, 5 times/week, i.g.) for two continuous weeks starting 7 days later after leukemic cells implantation. 3 days after the last treatment, animals were sacrificed for flow cytometry analysis.

Method details

Retrospective clinical analysis

153 patients with newly diagnosed primary or secondary AML according to the International Working Group criteria was enrolled in this study. Patients diagnosed with acute promyelocytic leukemia were excluded from this study. The study procedures and informed consent forms were approved by the ethic committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Jiangsu Province Hospital with number 2011-SR-085. All patients or their legal trustee provided written informed consent. All patients were administered decitabine at a dose of 15 mg/m2 intravenously (day 1–5) and granulocyte colonystimulating factor of 300 μg/d (day 0–9) for priming in combination with cytarabine 10 mg/m2 q12h (day 3–9) and aclarubicin 10 mg/d (day3–6) (D-CAG) as induction therapy. A median number of 2 cycles of the D-CAG regimen (range from 1 to 7 cycles) were administrated. Hydroxyurea was permitted as rescue medication to control white blood cells (WBC) to <5.0 × 109/L but was discontinued at least 24 h before decitabine treatment. Red cells and platelets were infused if hemoglobin (Hb) was under 70 g/L or platelet count under 20 × 109/L. Patients who did not achieve complete remission (CR) or partial remission (PR) were offered alternative therapies. Post-remission therapy consisted of 4–6 cycles D-CAG or conventional chemotherapy. Cytogenetic risk groups and treatment response were determined by European Leukemia Net and International Working Group criteria. Mutation analysis of seven relevant molecular marker genes was carried out. CR was defined as normalization of bone marrow blasts (≤5% blasts) and peripheral blood neutrophil count ≥1.0 × 109/L, platelet count >100 × 109/L. PR was defined as morphologic complete remission and 5–15% blasts with a decrease of at least 50% of total bone marrow blasts. The overall response rate (ORR) incorporated rates of CR and PR. D-CAG regimen was registered on ChicTR with number 11001700. Among patients without statin therapy, patient whose total cholesterol values in serums before treatment were over 5.17 mmol/L were included in the high blood fat subgroup, other patients were included in the normal blood fat. Statin therapy was identified from investigator reports of concurrent medication use, and subjects with any statin use while receiving D-CAG regimen were included in the statin subgroup. Patients with high blood fat who had not been on statin therapy were included in the no statin subgroup.

Compounds and drugs

Sulfosuccinimidyl oleate, SC75741, Fluvastatin, C75, Bezafibrate, Etomoxir, ABT-737, Cytarabine, Coumermycin A1, Novobiocin, TAK-242, PP1, Decitabine, α-Tocopherol, Doxorubicin, and Busulfan were purchased from MedChemExpress and reconstituted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or sterile PBS according to the solubility for use. Nor-NOHA were purchased from ApexBio Technology and reconstituted in DMSO according to the solubility for use. Palmitate, Oleic acid, and Arachidonic Acid were purchased from Cayman Chemical and were dissolved in ethanol at 70°C to yield a concentration of 200 mM. This stock solution was then diluted 1:10 in 10% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (Sangon Biotech, A602448) at 55°C for 10 min. Fatty acid solutions (20 mM) were sterile filtered before use in stimulation experiments. Negative controls, that is, cells to which no fatty acid was added, were treated with the fatty acid solvent to exclude effects mediated by the vehicle. OxLDL, LDL, and HDL were obtained from Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology. For in vivo animal experiments, anti-mouse NK1.1 antibody, anti-mouse CD8 antibody, anti-mouse CD4 antibody, isotype control antibody, and anti-mouse PD-L1 were purchased from Bio X cell.

Fatty acid or OxLDL uptake assay

For fatty acid uptake assay, BODIPY-Dodecanoic acid was purchased from Abnova (Fatty Acid Uptake Assay Kit). Briefly, cells were serum starved for 30 min. BODIPY-Dodecanoic acid was added to the medium to a final concentration of 1 μM. After 30 min, cells were harvested and determined by flow cytometry analysis. In some experiments, cells were serum starved for 30 min and pretreated with SSO (50 μM) for another 30 min, then these cells were incubated with 1 μM BODIPY-Dodecanoic acid for 30 min before flow cytometry analysis.

For OxLDL uptake assay, cells were incubated in PBS containing OxLDL-DyLight-488 (1:20 dilution, Oxidized LDL Uptake Assay Kit, Cayman Chemical, #601180). After 30 min, cells were harvested and determined by flow cytometry analysis. In some experiments, cells were pretreated with SSO (50 μM) for 30 min, then these cells were incubated with OxLDL-DyLight-488 for 30 min before flow cytometry analysis.

CFSE assay

Human T cells were isolated from PBMCs of healthy donors by using human T cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and stained with CFSE (Biolegend) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Then, these T cells (1 × 105 per well) were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28-coated beads (Miltenyi Biotec) and 50 U/ml human IL-2 (R&D Systems) in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) containing 10% FBS (Gibco) and cultured alone or co-cultured with AML cells at 16:1 ratio in 96-well plates for 3 days. After culture, the percentages of proliferating T cells were determined by CFSE-dilution.

T cell proliferation assay

T cells were isolated from spleen by using mouse T cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) or isolated from PBMCs of healthy donors or AML patients by using human T cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Then, these T cells (1 × 105 per well) were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28-coated beads (Miltenyi Biotec) and 50 U/ml IL-2 (R&D Systems) in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) containing 10% FBS (Gibco) and cultured alone or co-cultured with unstimulated or stimulated AML cells at 16:1 ratio in the lower chambers of a 96-well transwell plate (pore size, 0.4 μM, #3381, CORNING) for 3 days. AML cells were cultured in the upper chamber of transwell inserts. After culture, the numbers of T cells were determined by counting.

T cell killing assay

GFP− splenocytes from leukemic mice were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) containing 10% FBS (Gibco), 65 IU/mL mouse IL-2 (R&D Systems), and 7.5 μg/mL SIINFEKL peptide (Nanjing Peptide Biotech) for 5 days. Then, CD8+ T cells were isolated by using mouse CD8+ T cell Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies) and then co-cultured with C1498-OVA cells at 8:1 ratio for 4 h. After that, cells were counted and were determined by flow cytometry analysis. Then, the cell number of C1498-OVA cells were calculated.

Co-immunoprecipitation and western blot

For co-immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, and 10% glycerol, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Selleck) for 30 min at 4°C with constant shaking. Then protein supernatants were collected through centrifuge at 13,000g for 10 min. The protein lysates were incubated with magnetic beads (Invitrogen) pre-labeled with LYN antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-7274), TLR4 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-293072), MYD88 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-74532), or normal mouse IgG (Santa Cruz, sc-2025) overnight at 4°C with constant rotation. The immunoprecipitates were then wash five times with lysis buffer and used for immunoblotting.

For western blot, cells were collected and lysed in SDS lysis buffer (containing 2% SDS) with boiling at 95°C for 10 min. Protein lysates were loaded on 8–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel for running and then transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in TBST, the membranes were incubated with the the following antibodies overnight 4°C with constant rotation: p-p65 (Cell Signaling Technology; 3033S), p65 (Cell Signaling Technology; 8242S), actin (Cell Signaling Technology; 3700S), Lamin-B1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-374015), MYD88 (Cell Signaling Technology; 4283), CD36 (abcom; ab133625), ZDHHC6 (abcom; ab121423), TLR4 (CUSABIO Technology; CSB-PA001434), LYN (Cell Signaling Technology; 2796S). Membranes were then washed in TBS-T and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for appropriate time. Signals were visualized using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore). Specific cellular compartment fractionations were carried out using the nuclear/cytoplasmic extraction kit (Sangon Biotech).

Palmitoylation assay

Cells were labeled with DMSO or alkynyl palmitate (click chemistry tools) for 4 h. In some experiments, SSO (50 μM) were added. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1% SDS, phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Selleck)) followed by click reaction with biotin azide (click chemistry tools). Proteins were precipitated with 100% methanol for 2 h at −80°C and recovered by centrifugation at 14,000g for 10 min. The pellets were dissolved in suspension buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% SDS). Labeled cellular proteins were enriched using streptavidin agarose (click chemistry tools) at room temperature with rotation for 3 h. Protein-bound streptavidin agarose beads were washed 3 times and bound proteins were eluted and processed with western blot analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using the EZ-press RNA purification kit (EZBioscience) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was synthesized through reverse transcription of RNA using ReverTra Ace-αTM (TOYOBO). Quantitative real-time PCR reactions were performed using TB Green Premix Ex Taq (Takara) on the ABI7500 or Vii7 system (Thermo Fisher). Primer sequences for the detection of target genes are acquired from online resource (https://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/) and are listed in Table S4.

Flow cytometry analysis and sorting

Anti-human flow cytometry antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences: CD34-FITC/APC, CD36-APC/FITC, CD33-BV421, CD3-PE/PE-Cy7/APC/PerCP, CD4-BV421/PE, CD45-APC-Cy7, CD56-PE-Cy5. Anti-human flow cytometry antibodies were also purchased from BioLegend: CD14-BV421, PD-1-PE-Cy7, CD8-FITC. Anti-human PD-L1-PE-Cy7 was purchased from Invitrogen. Anti-human TLR4-APC was purchased from eBioscience. Anti-mouse flow cytometry antibodies were purchased from eBioscience: CD36-APC, PD-L1-PE-Cy7, TIM3-PE, APC-conjugated α-OVA257-264 (SIINFEKL) peptide bound to H-2Kb. Anti-mouse flow cytometry antibodies were also purchased from BioLegend: PD-1-BV785, LAG-3-BV785. Anti-mouse CD107a-BV421 was purchased from BD Biosciences. APC-conjugated H-2Kb OVA Tetramer-SIINFEKL was purchased from MBL. For intracellular staining, AML cells were stained for surface markers followed by fixation treatment (eBioscience). After that, cells were stained for intracellular antigens by anti-p-p65-PE (invitrogen) and anti-ARG1-APC (invitrogen). The flow cytometric data were collected with a BD Calibur or LSRII (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using FlowJo software. In the sorting experiment, the stained cells were sorted out with a cell sorter (BD FACSAria).

shRNA sequences, sgRNA sequences, and DNA constructs

Scramble control shRNA or targeting shRNA, designed by an online tool (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/gpp/public/seq/search), were cloned into pLKO.5 plasmid (Sigma-Aldrich, SHC201), individually. Scramble control sgRNA or targeting sgRNA, designed by an online tool (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/gppx/crispick/public), were cloned into LentiGuide Puro-P2A-EGFP plasmid (addgene, #137729; a gift from Fredrik Wermeling), individually. Cd36 cDNA, Cd36 mutant cDNA, OVA cDNA, IκB-SR cDNA, MYD88-GyrB cDNA, MYD88 mutant-GyrB cDNA, were cloned into pLV-EF1a-IRES-Neo plasmid (addgene, #85139; a gift from Tobias Meyer), individually. shRNA sequences and sgRNA sequences are listed in Table S4.

Virus packaging and transduction

For lentivirus packaging, the target vector were mixed with package plasmid psPAX2 (Addgene, #12260; a gift from Didier Trono) and pMD2.G (Addgene, #12259; a gift from Didier Trono) at a ratio of 4:3:1 and transfected into the HEK-293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Lentiviral particles were collected 48 h and 72 h after transfection and filtered. For lentivirus transduction, cells were cultured in medium as mentioned above with virus-contaning supernatant supplemented with 8 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma) for 2 consecutive days. The medium was then refreshed, and cells were cultured for further selection by appropriate cell sorting or antibiotics.

CRISPR-Cas9-based gene knockout in AML cells

lentiCas9-Blast plasmid (Addgene, #52962; a gift from Feng Zhang) was used to produce Cas9-expressing lentivirus. Then, AML cells were infected with these lentivirus. After selection, surviving cells were infected with sgRNA-expressing lentivirus. GFP+ cells were sorted into a 96-well plate as a single cell per well. After cell expansion, knockout cells were verified by western blotting, flow cytometry analysis, or RT-PCR.

Absolute quantitative lipidomics

The experiments and data analysis were supported by Shanghai Applied Protein Technology. Reagents including MS-grade methanol, MS-grade acetonitrile, HPLC-grade 2-propanol were purchased from Thermo Fisher. HPLC-grade formic acid, HPLC-grade ammonium formate and Tert-butyl Methyl Ether (MTBE) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For sample preparation and lipid extraction, lipids were extracted according to MTBE method. Briefly, samples were first spiked with appropriate amounts of internal lipid standards and then homogenized with 200 μL water and 240 μL methanol. After that, 800 μL of MTBE was added and the mixture was treated with ultrasound for 20 min at 4°C followed by sitting still for 30 min at room temperature. The solution was centrifuged at 14,000× g for 15 min at 10°C and the upper layer was obtained and dried under nitrogen. For LC-MS/MS method for lipid analysis, reverse phase chromatography was selected for LC separation using CSH C18 column (1.7μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, Waters). The lipid extracts were re-dissolved in 200 μL of 90% isopropanol/acetonitrile, centrifuged at 14,000× g for 15 min, and finally 3 μL of sample was injected. Solvent A was acetonitrile-water (6:4, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid and 0.1 mM ammonium formate, and solvent B was acetonitrile–isopropanol (1:9, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid and 0.1 mM ammonium formate. The initial mobile phase was 30% solvent B at a flow rate of 300 μL/min. It was held for 2 min, and then linearly increased to 100% solvent B in 23 min, followed by equilibrating in 5% solvent B for 10 min. Mass spectra was acquired by Q-Exactive Plus in positive and negative modes, respectively. ESI (Electron Spray Ionization) parameters were optimized and preset for all measurements as follows: source temperature, 300°C; capillary temperature, 350°C; the ion spray voltage was set at 3000 V, S-Lens RF Level was set at 50% and the scan range of the instruments was set at 200–1800 m/z. Identification of lipids was performed by LipidSearch software (Thermo Fisher Scientic), which is a widely used search engine for the identification of lipid species based on MS/MS math. LipidSearch contains more than 30 lipid classes and more than 1,500,000 fragment ions in the database. Both mass tolerance for precursor and fragment were set to 5 ppm.

Immunohistochemistry

Haematoxylin staining and immunostaining were performed on paraffin sections of tumors. Antibodies used were against human CD3 (Abcam).

Bioinformatics analyses

p65 ChIP-seq data for THP-1 cells were obtained from GSE103477. ChIP-seq data were processed by Cistrome analysis pipeline and was loaded to UCSC genome browsers for visualization.

Next-generation sequencing-based bisulfite sequencing PCR

CD36 promoter region-specific DNA methylation was assessed by next generation sequencing-based bisulfite sequencing PCR (NGS-BSP). In brief, we designed two amplicons that contained a total of 6 methylated positions in CD36 promoter region according to the previous two reports that have detected human CD36 methylation successfully.51,52 Primers for amplicon 1 and amplicon 2 were listed in Table S4. One microgram of genomic DNA was converted using a ZYMO EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo, D5005), and one-twentieth of the elution product was used as the template for PCR amplification with 35 cycles using a KAPA HiFi HotStart Uracil+ ReadyMix PCR Kit (Kapa, KK2801). For each sample, the BSP products of multiple differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were pooled equally, 5′-phosphorylated, 3′-dA-tailed, and ligated to a barcoded adapter using T4 DNA ligase (NEB, M0202S). The barcoded libraries from all samples were sequenced on the Illumina platform.

Quantification and statistical analysis