Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) resulting from chronic inflammation is a crucial issue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Although many reports established that intestinal resident CX3CR1high macrophages play an essential role in suppressing intestinal inflammation, their function in colitis-related CRC remains unclear. In this study, we found that colonic CX3CR1high macrophages, which were positive for MHC-II, F4/80 and CD319, promoted colitis-associated CRC. They highly expressed Col1a1, Tgfb, II10, and II4, and were considered to be fibrocytes with an immunosuppressive M2-like phenotype. CX3CR1 deficiency led to reductions in the absolute numbers of CX3CR1high fibrocytes through increased apoptosis, thereby preventing the development of colitis-associated CRC. We next focused statins as drugs targeting CX3CR1high fibrocytes. Statins have been actively discussed for patients with IBD and reported to suppress the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis. Statin treatment after azoxymethane/dextran sulfate sodium-induced inflammation reduced CX3CR1high fibrocyte counts and suppressed colitis-associated CRC. Therefore, CX3CR1high fibrocytes represent a potential target for carcinogenesis-preventing therapy, and statins could be safe therapeutic candidates for IBD.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel diseases, Inflammation, Colorectal neoplasms, Macrophages, Fibrocytes, CX3CR1, Statin

Subject terms: Cancer microenvironment, Gastrointestinal cancer, Monocytes and macrophages

Introduction

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are the most abundant immune cells in many tumors, and they exhibit diverse functions in some cancers and contribute to the development of carcinogenesis by inhibiting cancer immunity and producing the extracellular matrix1. TAMs are responsible for angiogenesis, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and the induction of regulatory T cells (Tregs) around tumors2. However, the role of TAMs in chronic inflammation-CRC remains unclear.

TAMs differentiate from both circulating monocytes that infiltrate tumors and tissue-resident macrophages (TRMs) that exist in inflamed tissue. Recent studies illustrated that inflammatory macrophages and TRMs in the intestine are derived from the same precursor, namely bone marrow (BM) monocytes3.

Geissmann et al.4 revealed that two functional subsets of peripheral blood (PB) monocytes were distinguished by the expression of CX3CR1 and CCR2 in both mice and humans. Sunderkotter et al.5 reported that three subpopulations of mouse PB monocytes, namely Ly6C−/low, Ly6Cint, and Ly6Chigh cells, differed in their inflammatory responses. Furthermore, the recruitment of Ly6Chigh monocytes to the inflamed colon was reported to depend on CCR2 expression6, and Ly6Chigh monocytes matured to colonic TRMs or proinflammatory macrophages in different situations7. Accordingly, circulating Ly6Chigh monocytes constantly replenish colonic CX3CR1high macrophages3.

The critical antiinflammatory roles of CX3CR1high macrophages in the colonic lamina propria (LP) were established in murine models of infectious colitis, drug-induced colitis, and T cell-dependent colitis8–11. Colonic TRMs, which are CX3CR1highCD11c+ macrophages, mediated the maintenance of Foxp3 expression in Tregs via the IL-10 pathway in experiments on drug-induced or T cell-dependent colitis10.

CX3CR1+ macrophages can exert protumor effects via the production of antiinflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-ß and extracellular matrix in some tumors1. For example, IL-10 in the tumor microenvironment induces the production of Tregs, thereby inhibiting cancer immunity. Although several reports indicated that CX3CR1 deficiency exacerbates intestinal inflammation and early-phase carcinogenesis12, no reports have evaluated late phase inflammation-associated carcinogenicity in vivo. Via long-term observation in the azoxymethane and dextran sulfate sodium (AOM/DSS) model of CRC, we previously demonstrated that CCR2+ monocytes and their progenies, namely fibrocytes, which were positive for both CD45 and type I collagen (ColI), aggravate fibrosis13 and that the angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker irbesartan suppressed the development of CRC by inhibiting the invasion of CCR2+ monocytes and fibrocytes into the colonic LP14.

In addition to their lipid-lowering effects, statins, which inhibit hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase, are known to suppress inflammation, induce apoptosis in some cancer cells and hematopoietic cells, and modulate angiogenesis, thus inhibiting the growth of a wide variety of cancer cells15. Several studies demonstrated that statins such as pravastatin (PRA), rosuvastatin, pitavastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin prevented the development of DSS-induced colitis and AOM/DSS-induced CRC in mice16–19. However, some studies reported conflicting results regarding the role of statins in the progression of tumors20, and the mechanism by which statins inhibit CRC development remains unclear.

In this study, we investigated the role of CX3CR1high fibrocytes in the development of colitis-associated CRC and examined whether statins can prevent CRC development by inhibiting the accumulation of CX3CR1high fibrocytes in the inflamed colon. The results suggest that CX3CR1high fibrocytes represent a potential therapeutic target to reduce the future risk of carcinogenesis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and that statins are safe therapeutic candidates.

Results

CX3CR1+ hematopoietic cells are related to the occurrence of colitis-associated carcinogenesis

To investigate the pathophysiological role of the CX3CR1/CX3CL1 (fractalkine) axis in colitis-associated carcinogenesis, we used a well-established model of CRC induced by AOM/DSS in CX3CR1gfp mutant mice, in which Cx3cr1 was inactivated following germline insertion of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene. Although CX3CR1 activity is normal in CX3CR1gfp/+ (CX3CR1 wild type [WT]) mice, CX3CR1gfp/gfp (CX3CR1 knock out [KO]) mice lack CX3CR1 expression. The protocol is summarized in Fig. 1a. In reference to our previous report14, mice were fed 1% DSS for one week, followed by water for 2 weeks, for three cycles. Although AOM/DSS treatment increased disease activity index (DAI) score, no significant difference in DAI score was observed between CX3CR1 WT and CX3CR1 KO mice during three cycles of DSS administration (Fig. 1b). Twenty weeks after AOM injection, which occurred nearly 3 months after the last DSS treatment, colons were harvested. In both groups, tumors occurred predominantly in the rectum. Despite similar levels of colitis, CX3CR1 KO mice displayed significantly fewer tumors than CX3CR1 WT mice (P < 0.0001, Fig. 1c, e). The maximum tumor diameter was significantly smaller in CX3CR1 KO mice than that in CX3CR1 WT mice (P < 0.05, Fig. 1e). Histological analysis of colon sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin also demonstrated that invasive tumor progression was dramatically reduced in CX3CR1 KO mice (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Colon tumor formation in CX3CR1 wild-type (WT) and CX3CR1-deficient mice after azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate (AOM/DSS) treatment. (a) Treatment scheme of the AOM/DSS model. (b) The disease activity index (DAI) score was monitored three times per week during the experimental period in AOM/DSS-treated CX3CR1gfp/+ (WT) mice and CX3CR1gfp/gfp (knockout [KO]) mice (n = 10/group). (c) Macroscopic view of the colonic lumen. Tumors developed in the distal to middle colon. (d) Representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained images of paraffin-embedded colon sections obtained from AOM/DSS-treated CX3CR1 WT and CX3CR1 KO mice. Scale bars, 200 μm. (e) Number of neoplasms and size of the largest neoplasm, as measured 20 weeks after AOM injection, in AOM/DSS-treated CX3CR1 WT and CX3CR1 KO mice (n = 10/group). *P < 0.05 and ****P < 0.0001 by an unpaired Student’s t-test. (f, g) Number of neoplasms and size of the largest neoplasm, as measured 20 weeks after AOM injection, in AOM/DSS-treated bone marrow chimeric mice, which were generated as described in the Materials and Methods (n = 10/group). **P < 0.01 by an unpaired Student’s t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

CX3CR1 is expressed on the surface of hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells such as epithelial cells25. To evaluate the contribution of hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic CX3CR1+ cells to colitis-associated carcinogenesis, we next generated BM chimeric mouse, in which donor and recipient mice were either CX3CR1 WT or CX3CR1 KO mice, and those chimeric mice were treated with AOM/DSS. The number of tumors in the colon was significantly lower in C57BL/6J-Ly5.1 mice reconstituted with CX3CR1 KO mouse-derived BM cells (CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice) than that in C57BL/6J-Ly5.1 mice reconstituted with CX3CR1 WT mouse-derived BM cells (CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice; P < 0.01, Fig. 1f). Conversely, the number of tumors did not differ between CX3CR1 WT mice reconstituted with C57BL/6J-Ly5.1 mouse-derived BM cells and CX3CR1 KO mice reconstituted with C57BL/6J-Ly5.1 mouse-derived BM cells (Fig. 1g). Therefore, BM-derived CX3CR1+ cells might play a crucial role in the occurrence of colitis-associated carcinogenesis.

CX3CR1high macrophages, a major resource of TAMs, are significantly associated with colitis-associated carcinogenesis

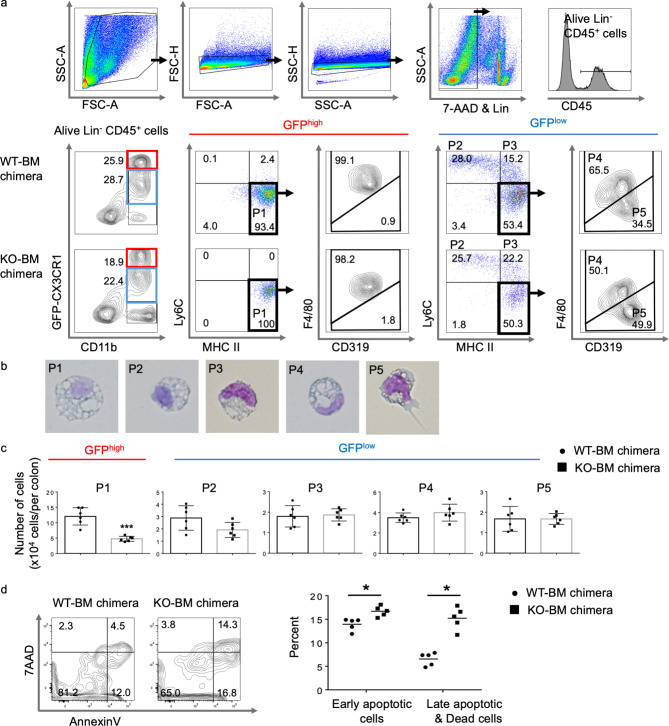

We quantified the numbers of hematopoietic cells in the colonic LP of both CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice using flow cytometry. No significant differences in the numbers of neutrophils, eosinophils, B cells, T cells, and NK cells were detected between CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice (data not shown). As presented in Fig. 2a, CD11b+ cells, from which Ly6G+ neutrophils and sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectin F positive eosinophils were excluded, were subdivided into three distinct populations based on GFP (CX3CR1) expression: GFP−, GFPlow, and GFPhigh. Almost all GFP-CX3CR1highCD11b+ cells displayed high MHC-II and F4/80 expression and low CD319 (signaling lymphocytic activation molecule family-7), and they lacked Ly6C (population 1 [P1]). These cells were large with prominent cytoplasmic vacuoles, and they were considered macrophages (Fig. 2a, b).

Fig. 2.

Monocyte-derived cells in the colonic lamina propria (LP) in azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate (AOM/DSS)-treated CX3CR1 wild-type (WT)-bone marrow (BM) and CX3CR1 knockout (KO)-BM chimeric mice. (a) Flow cytometry representative density and dot plots of the colonic LP of AOM/DSS-treated CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice. Isolated colonic LP cells were first gated on size and singularity, and lineage- and 7-AAD positive cells were eliminated. The lineage cocktail consisted of antibodies targeting B220, CD3, Ly6G, NK1.1, and Siglec F. Alive lineage−CD45+CD11b+ monocyte-derived cells were divided into GFP-CX3CR1high population (P1) and four GFP-CX3CR1low populations (P2, P3, P4, and P5). (b) Morphological assessment of cell-sorted macrophages (P1, P4), monocytes (P2, P3), and dendritic cells (P5). (c) The absolute cell numbers for each fraction in the colonic LP of CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice are presented (n = 6/group). ***P < 0.001 by an unpaired Student’s t-test.

(d) Flow cytometry with annexin V/7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) staining of colonic GFP+ macrophages isolated from CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice. The right panel presents the proportions of early apoptotic cells (annexin V+7-AAD−) and late apoptotic/dead cells (annexin V+7-AAD+) among GFP-CX3CR1+ macrophages (n = 5/group). *P < 0.05 by an unpaired Student’s t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

GFP-CX3CR1lowCD11b+ cells were divided into four subpopulations based on Ly6C, MHC-II, F4/80, and CD319 expression. P2 cells exhibited high Ly6C expression but lacked MHC-II. P3 cells were similar to P2 cells, excluding their positivity for MHC-II. Together with their morphological appearance, P2 and P3 cells were identical to Ly6Chigh inflammatory monocytes. The remaining GFP-CX3CR1lowCD11b+ cells expressed high levels of MHC-II but lacked Ly6C. They were subdivided into F4/80+CD319low (P4) and F4/80−CD319high fractions (P5; Fig. 2a). Despite being smaller, P4 cells were morphologically similar to P1 cells, and they were considered macrophages (Fig. 2b). P5 cells had dendrites extending from the cell surface and few cytoplasmic vacuoles, and they were considered dendritic cells (Fig. 2b).

We compared the presence of these five subpopulations in both CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice at 20 weeks after AOM injection. The absolute number of P1 cells was significantly decreased in the colonic LP of CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice compared to that in CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice (P < 0.001, Fig. 2c). The counts of other fractions in the colonic LP were similar between CX3CR1 KO-BM and CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice (Fig. 2c). These results demonstrate that GFP-CX3CR1highCD11b+Ly6C−MHC-II+F4/80+CD319low macrophages (P1 cells) might contribute to the occurrence of colitis-associated carcinogenesis.

CX3CR1 deficiency promotes apoptosis in CX3CR1high macrophages in the colonic LP

To determine the cause of decreased GFP-CX3CR1high macrophage counts in CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice, we incubated GFP-CX3CR1+CD11b+ macrophages, which were isolated from the colonic LP cells of untreated CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice, and apoptosis was assessed and quantified by annexin V/7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) staining and flow cytometry. Among colonic GFP-CX3CR1+ macrophages, the proportion of early apoptotic (annexin V+7AAD−) cells was slightly higher (14% vs. 17%, P < 0.05) and that of late apoptotic or dead cells (annexin V+7AAD+) was significantly higher (6% vs. 15%, P < 0.05) in CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice than in CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice (Fig. 2d). Therefore, CX3CR1 is believed to be responsible for promoting macrophage survival, and the absolute number of GFP-CX3CR1high macrophages, but not CX3CR1low monocytes and macrophages, decreased, probably because of increase in apoptotic cells in CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice.

CX3CR1 deficiency inhibits the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines, ColI, and matrix metalloproteinases in mouse rectal tissue

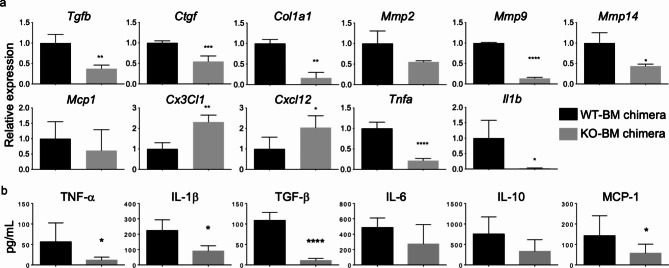

CX3CR1+ macrophages in some organs promote fibrosis, EMT, and carcinogenesis26–29. We evaluated the expression of several genes related to inflammatory and fibrotic responses in rectal tissues and the plasma concentrations of cytokines and chemokines in CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice.

As depicted in Fig. 3a, the mRNA levels of Tgfb, Ctgf, Col1a1, Mmp9, Mmp14, Tnfa, and Il1b were significantly lower in the rectal tissues of CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice than in those of CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice. Contrarily, the mRNA levels of Cx3cl1 and Cxcl12 were higher in rectal tissues from CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice than those from CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice. The plasma concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, TGF-β, and MCP-1 were significantly lower in CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice than in CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice, whereas plasma IL-6 and IL-10 concentrations did not differ between both chimeric mice (Fig. 3b). These data indicate that CX3CR1 deficiency in hematopoietic cells might result in inhibition of the TGF-β–CTGF signaling pathway, which plays an important role in fibrosis, and reductions in the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β, which are proinflammatory and procarcinogenic cytokines in the inflamed colon30,31.

Fig. 3.

Gene expression of cytokines, chemokines, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in rectal tissues and the plasma concentrations of cytokines and chemokines in CX3CR1 wild-type (WT)-bone marrow (BM) and CX3CR1 knockout (KO)-BM chimeric mice. (a) The histograms present mRNA expression relative to that of Gapdh for Tgfb, Ctgf, Col1a1, Mmp2, Mmp9, Mmp14, Mcp1, Cx3cl1, Cxcl12, Tnfa, and Il1b in rectal tissues obtained from CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice (n = 4/group). All gene expressions were normalized to Gapdh mRNA levels. The experiments were performed three times, and similar results were obtained. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 by an unpaired Student’s t-test. (b) Multiplex assay of chemokine and cytokine plasma concentrations in CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice (n = 8/group, pooled from two independent experiments).

*P < 0.05 and ****P < 0.0001 by an unpaired Student’s t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

CX3CR1 deficiency reduces the number of CD45+CD11b+ColI+ fibrocytes in the colonic LP

We previously reported that CCR2+ monocytes in PB differentiated into fibrocytes, which were defined as CD45+ColI+ cells, and that CCR2+ fibrocytes expressed CX3CR113. Fibrocytes have been demonstrated to contribute to both organ fibrosis and carcinogenesis in humans and murine models32.

In histological analysis of colon sections, we confirmed that some populations of GFP-CX3CR1+ cells expressed procollagen I, which is precursor of ColI (Fig. 4a). The numbers of GFP-CX3CR1+ and GFP-CX3CR1+procollagen I+ cells were significantly lower in CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice than in CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively; Fig. 4b). The proportion of GFP-CX3CR1+procollagen I+ cells among all GFP-CX3CR1+ cells in the colon was significantly smaller in CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice than in CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice (24.1% vs. 52.5%, P < 0.01). The percentage of CD45+CD11b+ColI+ fibrocytes was lower in colonic LP cells from CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice than in those from CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice (Fig. 4c, lower left).

Fig. 4.

CX3CR1high fibrocytes producing immunosuppressive cytokines and type I collagen (ColI). (a) Frozen colon sections obtained from CX3CR1 wild-type (WT)-bone marrow (BM) and CX3CR1 knockout (KO)-BM chimeric mice (n = 3, respectively) 20 weeks after azoxymethane (AOM) injection. The panels present GFP-CX3CR1 in green, procollagen I in red, and TO-PRO3 in blue. White arrows indicate GFP+procollagen I+ cells. Scale bars, 50 μm. (b) The histograms present the number of GFP-CX3CR1+ and GFP-CX3CR1+procollagen I+ cells in the colons of CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice. The experiments were performed twice, and similar results were obtained. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by an unpaired Student’s t-test. (c) Flow cytometry representative dot plots of the colonic lamina propria (LP) cells of AOM/dextran sodium sulfate-treated CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice. To identify fibrocytes, surface staining for lineage markers (B220, CD3, Ly6G, NK1.1, and Siglec F), CD45, CD11b and F4/80, and intracellular staining for Col I were performed. Isolated colonic LP cells were first gated on size and singularity, and lineage- and Zombie Aqua positive cells were eliminated. The two dot plots on the lower left present a representative flow cytometry image of CD11b and ColI in lineage−CD45+ cells. The lower middle dot plot depicts the expression of F4/80 and GFP-CX3CR1 in lineage−CD11b+ColI+ fibrocytes. The lower right panel presents the percentage of GFP-CX3CR1+ColI+F4/80+ fibrocytes among CD45+ cells in the colonic LP of CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice. The red and blue columns indicate the GFP-CX3CR1high and GFP-CX3CR1low populations, respectively. Data were presented from three experiments. **P < 0.01 by an unpaired Student’s t-test.

(d) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of CD319 (SLAMF7) and ColI in the colonic GFP-CX3CR1high (red) and GFP-CX3CR1low macrophages (blue) of CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice compared to appropriate isotype controls (gray). (e) The histograms present the mRNA expression of some genes in colonic GFP-CX3CR1high and GFP-CX3CR1low macrophages obtained from 6–10 CX3CR1 WT mice. The mRNA expression of Col1a1, Tgfb, Il10, Il4, Arg1, and Nos2 is presented relative to that of Gapdh. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 by an unpaired Student’s t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

CX3CR1high macrophages produce ColI and immunosuppressive cytokines.

Although all CD45+CD11b+ColI+ fibrocytes expressed F4/80, they consisted of two populations based on their GFP-CX3CR1 expression (Fig. 4c, lower center). The GFP-CX3CR1high population, but not the GFP-CX3CR1low population, was mainly decreased in CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice compared to the findings in CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice (Fig. 4c, lower right).

Although both GFP-CX3CR1high and GFP-CX3CR1lowCD11b+ macrophages, which were sorted from colonic LP cells in CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice, expressed CD319 at the same level, ColI was more highly expressed in GFP-CX3CR1high macrophages than in GFP-CX3CR1low macrophages (Fig. 4d). The GFP-CX3CR1high macrophages more highly expressed Col1a1, Tgfb, Il10, and Il4 than GFP-CX3CR1low macrophages, but their expression of Arg1 as an M2-like marker and Nos2 as an M1-like marker was similar (Fig. 4e).

These results indicate that colonic CX3CR1high macrophages are true fibrocytes that exhibit an immunosuppressive M2-like phenotype, as Nos2 is reported to be induced in both M1 and M2 macrophage31. Based on these results, CX3CR1 deficiency might prevent the development of AOM/DSS-associated CRC by reducing the counts of CX3CR1high immunosuppressive M2-like fibrocytes in the inflamed colon.

PRA accelerates apoptosis in CX3CR1high fibrocytes and prevents colitis-associated carcinogenesis by inhibiting CX3CL1/CX3CR1 signaling

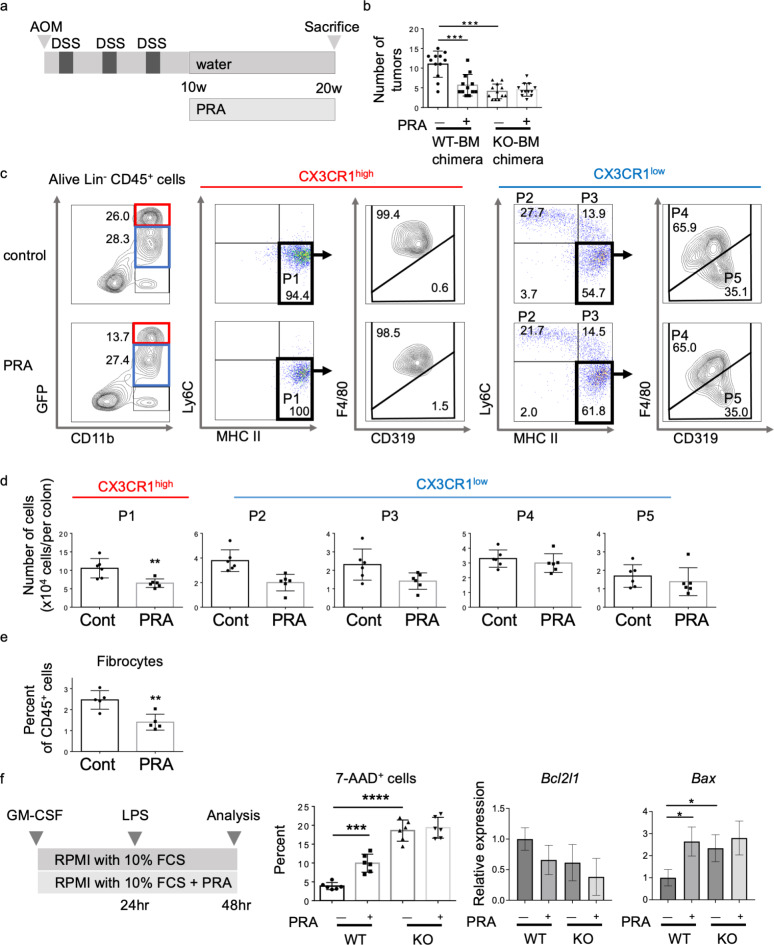

It has been reported that statins influence cytokine production by human macrophages and decrease their CX3CR1 expression via geranylgeranylation-dependent Rac1 activation24. Recently, some groups reported that statins can reduce the risk of CRC in patients with and without IBD33,34. Because CX3CR1 deficiency abrogated AOM/DSS-associated carcinogenesis, we next investigated whether statin treatment could prevent carcinogenesis through modulating CX3CR1+ macrophage counts in the colonic LP.

To explore the effect of PRA during the tumor progression phase in our colitis-associated carcinogenesis model, we administered PRA to both CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice for 10 weeks after AOM injection and three cycles of DSS administration (Fig. 5a). In CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice, the number of colon tumors was significantly lower in the PRA-treated group than in the control group. However, PRA did not reduce the number of colon tumors in CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice (Fig. 5b). Flow cytometry revealed the significant reductions of GFP-CX3CR1high macrophages (P1) and CD45+CD11b+Col I+ fibrocytes but not GFP-CX3CR1low monocytes (P2, P3), macrophages (P4) and dendritic cells (P5) in the colonic LP in PRA-treated mice (Fig. 5c–e).

Fig. 5.

Suppression of CX3CR1high fibrocytes by pravastatin (PRA) inhibits colitis-associated carcinogenesis. (a) Treatment scheme of the azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate (AOM/DSS) model with or without PRA. (b) The number of neoplasms at 20 weeks after AOM injection was compared between control and PRA-treated CX3CR1 wild-type (WT)-bone marrow (BM) and CX3CR1 knockout (KO)-BM chimeric mice (n = 12/group). ***P < 0.001 by a one-way ANOVA. (c) Flow cytometry representative density and dot plots of the colonic lamina propria (LP) of AOM/DSS-injured CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice treated with or without PRA. Lineage (Ly6G, Siglec F, B220, CD3)−CD11b+ macrophages from the LP of CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice treated with or without PRA were divided into GFP-CX3CR1high macrophages (P1), GFP-CX3CR1low monocytes (P2 & P3), macrophages (P4), and dendritic cells (P5).

(d) The absolute cell numbers for the five fractions in the colonic LP of control and PRA-treated mice are presented (n = 6/group). **P < 0.01 by an unpaired Student’s t-test.

(e) The proportion of GFP-CX3CR1+CD45+CD11b+ColI+ fibrocytes among CD45+ cells in the colonic LP of control and PRA-treated mice is presented (n = 5/group). **P < 0.01 by an unpaired Student’s t-test. (f) In vitro apoptosis assay of BM monocytes isolated from CX3CR1 WT and CX3CR1 KO mice. The left panel depicts the experimental scheme. Monocytes, which were incubated in medium containing the control or PRA, were treated with lipopolysaccharide for 24 h. The middle panel presents the proportion of apoptotic cells (7-AAD+ cells) compared between control and PRA-treated CX3CR1 WT and CX3CR1 KO mice (n = 6/group). The right two panels show the expression of mRNA of Bcl2l1 and Bax compared between control and PRA-treated CX3CR1 WT and CX3CR1 KO mice. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 by a one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

To examine the influence of PRA on apoptosis in macrophages, we incubated monocytes, which were freshly isolated from the BM of CX3CR1 WT and CX3CR1 KO mice, in the presence or absence of 10 µg/ml PRA and analyzed the surface phenotype and viability of these cultured cells (Fig. 5f, left). Although PRA did not change the expression of surface markers including CX3CR1 on macrophages incubated for 2 days (data not shown), it promoted apoptosis in monocyte-derived cells from CX3CR1 WT mice but not in those from CX3CR1 KO mice (Fig. 5f, middle). We further analyzed the expression of anti- and pro-apoptotic genes, including Bcl2l1, Bax, and Casp3, in these cultured macrophages. PRA significantly increased the mRNA level of Bax in monocyte-derived cells from CX3CR1 WT mice but not in those from CX3CR1 KO mice (Fig. 5f, right). However, there was no significant change in the mRNA expression level of Bcl2l1 and Casp3 (data not shown) among these cultured cells from CX3CR1 WT and CX3CR1 KO mice, in the presence or absence of 10 µg/ml PRA.

The mRNA levels of Ctgf, Col1a1, Tnfa, Mmp2, Mmp9, and Mmp14 in rectal tissues were significantly suppressed by PRA treatment compared to the findings in control mice (Fig. 6a). The plasma concentrations of TGF-β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were significantly lower in PRA-treated mice than in control mice (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of the production of proinflammatory cytokines and metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the inflamed rectum by pravastatin (PRA). (a) The histograms present the mRNA expression of Tgfb, Ctgf, Col1a1, Tnfa, Mmp2, Mmp9, Mmp14, and Il1b relative to that of Gapdh in rectal tissues obtained from the control (n = 4) and PRA-treated groups (n = 4). The experiments were performed three times, and similar results were obtained. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 by an unpaired Student’s t-test.

(b) Multiplex assay of cytokine plasma concentrations in the control and PRA-treated groups (n = 8/group, pooled from three independent experiments). *P < 0.05 by an unpaired Student’s t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

Therefore, PRA could reduce the number of GFP-CX3CR1high macrophages and fibrocytes in the inflamed colon by inducing their apoptosis, thereby preventing the development of CRC.

Discussion

Colonic TRMs (CX3CR1high macrophages) have been reported to be crucial in tissue vascularization and the suppression of intestinal inflammation via Treg activation at steady state10,11,35,36. Some authors described the role of CX3CR1high macrophages in the development and progression of colitis and colitis-associated CRC. Kostadinova et al.37 demonstrated that inflammatory macrophage infiltration into the intestinal submucosa after DSS ingestion was attenuated in CX3CR1 KO mice together with a reduction of intestinal inflammation. Zheng et al.26 found that enhanced CX3CR1 expression was associated with poor prognosis in patients with colon cancer, whereas liver metastasis in mice with colon cancer was significantly inhibited in mice lacking CX3CR1. Kuboi et al.38 also demonstrated that blockade of the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis by antiCX3CR1 antibody inhibited the colitis-triggered inflammatory cascade by dislodging crawling monocytes and inhibiting their patrolling behavior. On the contrary, Medina-Contreras et al.8 revealed that the translocation of commensal bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes was markedly increased and the severity of DSS-induced colitis was dramatically enhanced in CX3CR1 KO mice. Furthermore, Marelli et al.39 reported that CX3CR1 KO mice failed to resolve intestinal inflammation despite high IL-10 production, leading to an increased severity of colitis and a higher number of adenomatous polyps in chemical and genetic models of colon carcinogenesis. Because of the incompatible results of these prior studies, it remains unclear whether the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis promotes or suppresses colitis-associated CRC.

The aforementioned controversial findings regarding the role of CX3CR1high cells in the development of colitis and CRC might be explained by differences in the timing of the analysis, namely the early or late phase of inflammation. Previous reports illustrated that TAMs can be classified into M1-like macrophages (antitumor phenotype) and M2-like macrophages (protumor phenotype) and that M1-like and M2-like macrophages play important roles in the early and late phase of inflammation, respectively40,41. In this study, we focused on the late stage of CRC development at 20 weeks after AOM injection, nearly 3 months after the third DSS dose, to clarify whether the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis promotes or suppresses colitis-associated CRC.

Our study had three important findings. First, BM-derived CX3CR1high macrophages were significantly related to the development and progression of colitis-associated carcinogenesis. Second, they were positive for CD11b, F4/80, MHC-II, and CD319, which is expressed in fibrocytes42, and they expressed Col1a1, Tgfb, Il10, and Il4, which are considered markers of M2-like macrophages. Third, PRA induced apoptosis in CX3CR1high macrophages and inhibited the development of colitis-associated CRC by reducing CX3CR1high fibrocytes in the colon.

We previously reported that targeted deletion of CCR2 in BM-derived cells and treatment with irbesartan, which is reported to act as a CCR2 antagonist, prevented intestinal fibrosis and colitis-associated CRC by inhibiting the accumulation of CCR2+ monocytes, CCR2+CX3CR1+ macrophages, and CCR2+ fibrocytes in the inflamed colon13,14, whereas little is known regarding colitis-associated CRC development in CX3CR1 KO mice. In this study, we found that the number of tumors in the colon was significantly lower in CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice than in CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice, suggesting that the inhibition of inflammatory-related tumorigenesis was associated with reduced number of BM-derived CX3CR1high macrophages.

Fibrocytes are BM-derived cells with both the inflammatory features of macrophages and the tissue remodeling properties of fibroblasts. It has been reported that differentiated fibrocytes and macrophages share several phenotypes42 and that uptake of secreted ColI by hematopoietic cells accounts for the fibrocyte population43,44. However, in this study, we confirmed that GFP-CX3CR1highCD45+CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages highly produced ColI and were thought to be true fibrocytes. As they also expressed Il10, Il4, and Tgfb, they were comparable to M2-like macrophages, which have been reported to induce immunosuppression and contribute to the progression of tumorigenesis1,2,12. CX3CL1 promoted monocyte survival45, whereas CX3CR1 deficiency increased macrophages apoptosis in some organs and cancers26,28,46–48, consistent with our results. The CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis has been reported to contribute to skin carcinogenesis by regulating the accumulation of CX3CR1+ TAMs with an M2-like phenotype, making them a good target for preventing skin cancers49. Our present data also suggest that treatment targeting CX3CR1high macrophages and fibrocytes might be more effective for preventing the development of CRC.

In addition to their lipid-lowering effects, statins possess a variety of pleiotropic effects, such as inhibiting cell proliferation, enhancing apoptosis, modulating tumor microenvironment, thereby inhibiting the growth of a wide variety of cancer cells15,50. Although several types of statins were administered alone or in combination with other anticancer agents in numerous clinical trials51, the precise mechanisms of their antitumor effects remain unclear.

In this study, we found that PRA inhibited further formation of colon tumors even when it was administered after multiple colon tumors had developed in CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice treated with AOM/DSS. Furthermore, PRA reduced the counts of CX3CR1highCD11b+Ly6C−MHC-II+F4/80+CD319low fibrocytes in the inflamed colon and significantly promoted apoptosis in cultured monocyte-derived cells isolated from CX3CR1 WT mice but not in those obtained from CX3CR1 KO mice in vitro. Statins are known to be efficacious in both hematopoietic cells and epithelial cells, including cancer cells52,53. However, PRA did not inhibit the growth of any tumor cell line in vitro54, but it significantly suppressed tumor growth in animal xenografts55, indicating that PRA has indirect effects on tumor proliferation.

Based on our findings and prior results, we speculate that CX3CR1high macrophages and fibrocytes are the therapeutic targets of PRA and that PRA leads to a gradual decrease in TAM counts by inducing their apoptosis. However, this study was performed to clarify the effect of PRA in the colitis-associated CRC model. IBD contributes to the tumor initiation and progression in colitis-associated CRC, which arise from precursor dysplastic lesions. On the other hand, most sporadic CRC are thought to develop from polyps through adenomatous change. Further experiments are needed because the immuneprofiling pattern of colitis-associated CRC might be different from that of sporadic CRC.

One limitation of this study is that we used mice with conventional CX3CR1 KO opposed to monocyte/macrophage-specific conditional KO of CX3CR1. As CX3CR1 is expressed on circulating monocytes, tissue macrophages, and tissue dendritic cells as well as T cells and NK cells56, whether our present finding that CX3CR1 deficiency prevents the development of AOM/DSS-associated CRC is related to reduced counts of immunosuppressive M2-like macrophages or other types of leukocytes was not clarified. Yu et al.57 reported that the counts of DX5+CD3– NK cells and monocyte/macrophages but not CD3+ T cells or B220+ B cells were reduced in the lungs of CX3CR1 KO mice compared to the findings in CX3CR1 WT mice. Yan et al.58 also reported that CX3CR1 KO mice had a reduced proportion of functional CD8+ cytotoxic T cells within B16F10 mouse melanoma tumors. Furthermore, some reports illustrated that CX3CR1 blockade abrogated the ability of NK cells to clear intravenously injected YAC tumor cells from murine lungs or kill CX3CL1-expressing K562 erythroleukemia cells59,60. In this study, we found no differences in the numbers of B cells, T cells, and NK cells in the colon between CX3CR1 WT-BM and CX3CR1 KO-BM chimeric mice. Further studies using single-cell RNA sequencing in conditional KO mice should be conducted to determine the contribution of colonic resident macrophages to the tumor microenvironment in CRC.

In summary, we revealed that CX3CR1high fibrocytes with an M2-like phenotype contributed to colitis-associated CRC by producing extracellular matrix and immunosuppressive cytokines. Tumorigenesis involves multiple stages, including initiation, promotion, progression, and metastasis. M2 macrophages promote tumor survival and tumor growth during the development of advanced tumors41. CX3CR1 deficiency and PRA significantly reduced the number of M2-like CX3CR1high fibrocytes by inducing their apoptosis, thereby preventing the progression of colitis-associated CRC. The repositioning of statins could be useful for patients with IBD.

Materials and methods

Animals

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Research Committee, Mie University, Japan (approval number: 25-1). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines and regulations for animal experiment. This study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. Breeding pairs of CX3CR1gfp/gfp (CX3CR1 KO) mice (B6.129P2(Cg)-Cx3cr1tm1Litt/J, C57BL/6-Ly5.2 background), in which GFP was expressed at the locus of the CX3CR1 gene, and C57BL/6J-Ly5.1 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). C57BL/6-Ly5.2 mice were purchased from SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice were crossbred with C57BL/6-Ly5.2 mice to produce CX3CR1gfp/+ heterozygous (CX3CR1 WT) mice. All mice were bred and maintained at the Institute of Laboratory Animals, Mie University (Tsu, Japan). Male C57BL/6J-Ly5.1 mice (10–12 weeks old) were irradiated with a single 10-Gy dose of total irradiation using a 4 × 106 V linear accelerator. Then, 5 × 106 BM total nucleated cells obtained from 10-week-old female CX3CR1 WT mice and CX3CR1 KO mice were injected into irradiated male C57BL/6J-Ly5.1 mice. Meanwhile, male CX3CR1 WT mice and CX3CR1 KO mice received a single i.v. injection of 5 × 106 BM total nucleated cells obtained from 10-week-old female C57BL/6J-Ly5.1 mice after being irradiated with a single 10-Gy dose of total irradiation. AOM/DSS treatment started 8 weeks after BM transplantation. We used the colitis-associated carcinogenesis model as described previously. Although almost all of the BM chimeric mice treated with 2% DSS died within 10 weeks, using 1% DSS allowed the mice to survive longer and to be evaluated for carcinogenesis 20 weeks after AOM injection. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 10 mg/kg AOM (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). One week after AOM treatment, mice were given 1% DSS (MW 36–50 kDa, MP Biochemicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) dissolved in drinking water for 7 days, followed by water alone for 2 weeks. DSS treatment was repeated for three cycles. AOM/DSS-induced colitis was scored using the DAI, which assesses weight loss, stool consistency, and bleeding21. DAI score was measured three times per week. Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation after anesthesia with isoflurane 10 or 20 weeks after AOM injection.

BM chimeric mice were treated with PRA (Fujifilm, Japan) dissolved in drinking water (400 mg/L) for 10–20 weeks22. The estimated PRA dose was 40 mg/kg body weight per day. Controls received water without PRA.

Tissue preparation

Mouse colons were harvested and fixed with 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde for 8 h at room temperature as previously reported14. Some tissue blocks were embedded in paraffin after dehydration in a graded alcohol series. Other tissue blocks were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde, embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT medium (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA, USA), rapidly frozen via submersion in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C. Tissue blocks were cut into 5-µm-thick sections using a microtome or cryostat.

Histological analysis

Serial sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The images were captured per section at ×100 magnification using an Olympus BX41 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 10×/0.40 numerical aperture objective lens and an Olympus Camedia C-5060 camera.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Frozen colon sections were treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS−) for 1 h and blocking reagents containing 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h. Afterward, they were incubated with antiprocollagen 1A1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), followed by Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated donkey antigoat IgG (Molecular Probes Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Nuclei were stained with TO-PRO3 iodide (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA). As a negative control, sections were stained without antiprocollagen 1A1 antibody, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated donkey antigoat IgG. The sections were examined using an Olympus IX81 FV1000 laser-scanning confocal microscope.

Isolation of PB cells and colonic LP cells

PB cells and colonic LP cells were isolated using a modification of our previously reported method14. Blood was collected from anesthetized mice via cardiac puncture using a heparinized syringe. After red blood cell removal using ammonium–chloride–potassium lysis buffer, white blood cells were pelleted via centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 min at room temperature and resuspended in 400–600 µL of PBS− containing 0.1% BSA. The colons were resected, opened longitudinally, and washed with saline to remove the intestinal contents. Next, they were cut into 0.5-cm pieces, which were washed twice with Hanks’ balanced salt solution without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (HBSS−) containing 2.5% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1 mM dithiothreitol and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine to remove the mucus. Subsequently, epithelial cells were removed via incubation with HBSS− containing 2.5% FCS, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine with shaking (200 rpm) at 37 °C for 30 min. The colonic pieces were then digested in HBSS− containing 2.5% FCS, 1.0 mg/mL collagenase VIII (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 0.1 mg/mL DNase I (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ, USA) with shaking (200 rpm) at 37 °C for 30 min. The resultant cell suspensions were sequentially passed through cell strainers (70 μm), resuspended in 40% Percoll (GE Healthcare UK, Little Chalfont, UK), and layered on top of 75% Percoll following centrifugation at 2500 rpm for 20 min at room temperature. Cells residing at the interface between the two Percoll layers were collected, washed twice with PBS−, and resuspended in 0.1% BSA PBS− for use in further experiments.

Flow cytometry

Isolated cells were incubated with antimouse CD16/CD32 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) to block nonspecific Fc receptors. Then, the cell surface was stained with the corresponding mixture of fluorescently labeled monoclonal antibodies against B220, CD3, CD11b, CD45, F4/80, MHC-II (IA/IE), Ly6C, Ly6G, Siglec F, and NK-1.1 (BioLegend). The lineage cocktail consisted of antibodies targeting B220, CD3, Ly6G, NK1.1, and Siglec F. 7-AAD and Zombie Aqua Fixable Viability Kit (BioLegend) was used to discriminate live and dead cells. Isolated cells were first gated by size and CD45 expression. Next, lineage-positive and dead cells were eliminated. To stain the intracellular antigens after surface labeling, cells were fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequentially incubated with rabbit anticollagen type I (Rockland, Limerick, PA, USA) and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (Invitrogen). Data were acquired using LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences) and processed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA) with the appropriate isotype controls to determine the gating. The sample size of FACS data was small. Because more than 8 h were needed to isolate cells from the colonic LP and perform staining for flow cytometry, we limited the number of mice to maintain experimental repeatability. Cell sorting was performed using FACSAria II (BD Biosciences). Some of the sorted cells were spun onto glass slides, dried, and stained using a Rapid Romanowsky staining kit (Raymond A. Lamb Ltd).

Ex vivo apoptosis assay

Annexin V (BioLegend) and 7-AAD were used to identify early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and dead cells23. CX3CR1+ macrophages, which were CD11b+Ly6C−F4/80+, were isolated from colonic LP cells and then incubated in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium containing 10% FCS for 6 h. Monocytes, which were freshly isolated from the BM of CX3CR1 WT and CX3CR1 KO mice, were incubated in RPMI medium containing 10% FCS in the presence or absence of 10 µg/mL PRA and analyzed the surface phenotype and viability of these cultured cells. Then, the incubated macrophages were stained with APC-annexin V and 7-AAD according to the manufacturers’ protocols.

Apoptosis assay of BM-cultured macrophages

Monocytes were isolated from BM total nuclear cells from CX3CR1 WT and CX3CR1 KO mice using the EasySep Mouse Monocyte Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). On day 1, these isolated monocytes were divided on 24 well-plates at a density of 1.0 × 105 cells/well and incubated in RPMI medium containing 10% FCS, GM-CSF (100 ng/mL) and without or with PRA (10 mg/mL) for 24 h24. On day 2, these incubated cells were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (100 ng/mL). On day 3, these incubated cells were stained with antibodies against CD11b, CD45, F4/80, IA/IE, Ly6C, and 7-AAD, followed by flow cytometry. Total RNA was extracted from these cells using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and converted to complementary DNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Analysis of gene expression in rectal tissue and BM-cultured macrophages

Total RNA was extracted from frozen rectal samples and BM-cultured macrophages using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and converted to complementary DNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Quantitative real-time PCR of the complementary DNA was performed using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System Upgrade (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with the default settings. The following primers were used: Tgfb1 (Mm01178820_m1), Ctgf (Mm01192933_g1), Col1a1 (Mm00801666_g1), Mmp2 (Mm00439498_m1), Mmp9 (Mm00442991_m1), Mmp14 (Mm00485054_m1), Mcp1 (Mm00441242_m1), Cx3cl1 (Mm00436454_m1), Cxcl12 (Mm00445553_m1), Tnfa (Mm00443259_g1), Il1b (Mm00434228_m1), Casp3 (Mm01195085_m1), Bcl2l1 (Mm00437783_m1), Bax (Mm00432051_m1) and Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1). Gapdh was amplified as internal control. Relative quantification was done by using the 2−△△Ct method.

Analysis of gene expression in colonic macrophages

Total RNA was extracted from sorted macrophages using an RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) and converted to complementary DNA using SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Digital PCR was performed using 5 µL of the eluted RNAs collected from sorted GFPlow and GFPhigh macrophages obtained from 10 CX3CR1 WT-BM chimeric mice. Digital PCR was performed using a QuantStudio 3D Digital PCR System platform consisting of a QuantStudio 3D Instrument, a Dual Flat Block GeneAmp PCR System 9,700, and a QuantStudio 3D Digital PCR Chip Loader (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reverse transcription was performed at 50 °C for 10 min, followed by inactivation/initial denaturation at 96 °C for 5 min. The PCR protocol consisted of 40 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s and annealing/extension at 56 °C for 1 min, followed by final extension at 60 °C for 5 min. Data analysis was performed with the online version of the QuantStudio 3D AnalysisSuite (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The following primers were used: Col1a1 (Mm00801666_g1), Tgfb1 (Mm01178820_m1), Il10 (Mm01288386_m1), Il4 (Mm00445259_m1), Arg1 (Mm00475988_m1), and Nos2 (Mm00440502_m1). Gapdh was amplified as an internal control.

Cytokine quantification

Cytokine levels in plasma samples obtained from mice were determined using the LEGENDplex Mouse Inflammation Panel (BioLegend) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the plasma samples were diluted 2-fold with Assay Buffer and incubated with the mixed beads for 2 h at room temperature with shaking. Next, they were incubated with detection antibodies for 1 h. Without washing, samples were incubated with streptavidin–phycoerythrin conjugate for 30 min. Then, the samples were washed and suspended in 200 µL of wash buffer. Data were acquired on BD LSRFortessa and analyzed using LEGENDplex Data Analysis Software (BioLegend).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were analyzed by an unpaired Student’s t-test or a one-way ANOVA where appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Experimental Animal Facility of Mie University for their help with animal care and Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the following: concept and design of the study (K.H. and M.M.); performing experiments (K.H., M.M., N.Ku., M.Y., K.N., T.S. and I.T.); analysis and interpretation of data (K.H., M.M., N.Ku., I.T. and N.Ka.); drafting the article (K.H. and M.M.) and final approval of the version to be submitted (all authors).

Funding

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) for 2019–2021 (to M.M., Grant 19K08442) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the 2015 Okasan-Kato Foundation (to M.M.) and the 2017 Mie Medical Association Foundation (to M.M.).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ma, R. Y., Black, A. & Qian, B. Z. Macrophage diversity in cancer revisited in the era of single-cell omics. Trends Immunol.43, 546–563 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denardo, D. G. & Ruffell, B. Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol.19, 369–382 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bain, C. C. et al. Constant replenishment from circulating monocytes maintains the macrophage pool in the intestine of adult mice. Nat. Immunol.15, 929–937 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geissmann, F., Jung, S. & Littman, D. R. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity19, 71–82 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunderkötter, C. et al. Subpopulations of mouse blood monocytes differ in maturation stage and inflammatory response. J. Immunol.172, 4410–4417 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zigmond, E. et al. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity37, 1076–1090 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bain, C. C. et al. Resident and pro-inflammatory macrophages in the colon represent alternative context-dependent fates of the same Ly6Chi monocyte precursors. Mucosal Immunol.6, 498–510 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medina-Contreras, O. et al. CX3CR1 regulates intestinal macrophage homeostasis, bacterial translocation, and colitogenic Th17 responses in mice. J. Clin. Invest.121, 4787–4795 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zigmond, E. et al. Macrophage-restricted interleukin-10 receptor deficiency, but not IL-10 deficiency, causes severe spontaneous colitis. Immunity40, 720–733 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kayama, H. et al. Intestinal CX3C chemokine receptor 1(high) (CX3CR1(high)) myeloid cells prevent T-cell-dependent colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A109, 5010–5015 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, M. et al. Critical role for the microbiota in CX3CR1 + intestinal mononuclear phagocyte regulation of intestinal T cell responses. Immunity49, 151–163e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marelli, G., Belgiovine, C., Mantovani, A., Erreni, M. & Allavena, P. Non-redundant role of the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 in the anti-inflammatory function of gut macrophages. Immunobiology222, 463–472 (2017a). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuroda, N. et al. Infiltrating CCR2 + monocytes and their progenies, fibrocytes, contribute to colon fibrosis by inhibiting collagen degradation through the production of TIMP-1. Sci. Rep.9, 8568 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hachiya, K. et al. Irbesartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, inhibits colitis-associated tumourigenesis by blocking the MCP-1/CCR2 pathway. Sci. Rep.11, 19943 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma, S. & Ma, C. C. H. Recent development in pleiotropic effects of statins on cardiovascular disease through regulation of transforming growth factor-beta superfamily. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev.22, 167–175 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sasaki, M. et al. The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitor pravastatin reduces disease activity and inflammation in dextran-sulfate induced colitis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.305, 78–85 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naito, Y. et al. Rosuvastatin, a new HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitor, reduces the colonic inflammatory response in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Int. J. Mol. Med.17, 997–1004 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasui, Y. et al. A lipophilic statin, pitavastatin, suppresses inflammation-associated mouse colon carcinogenesis. Int. J. Cancer121, 2331–2339 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei, A. et al. Atorvastatin promotes the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and attenuates murine colitis. Immunology149, 432–446 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann, P., Roumeguère, T., Schulman, C. & Van Velthoven, R. Use of statins and outcome of BCG treatment for bladder cancer. N Engl. J. Med.355, 2705–2707 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito, R. et al. Interferon-gamma is causatively involved in experimental inflammatory bowel disease in mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol.146, 330–338 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorza-Gil, E., García-Arevalo, M., Favero, B. C., Gomes-Marcondes, M. C. C. & Oliveira, H. C. F. Diabetogenic effect of pravastatin is associated with insulin resistance and myotoxicity in hypercholesterolemic mice. J. Transl Med.17, 285 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamura, A. et al. C/EBPβ is required for survival of Ly6C- monocytes. Blood130, 1809–1818 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu, H. et al. The differential statin effect on cytokine production of monocytes or macrophages is mediated by differential geranylgeranylation-dependent Rac1 activation. Cell. Death Dis.10, 880 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivas-Fuentes, S., Salgado-Aguayo, A., Arratia-Quijada, J. & Gorocica-Rosete, P. Regulation and biological functions of the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis and its relevance in solid cancer: a mini-review. J. Cancer12, 571–583 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng, J. et al. Chemokine receptor CX3CR1 contributes to macrophage survival in tumor metastasis. Mol. Cancer12, 141 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmall, A. et al. Macrophage and cancer cell cross-talk via CCR2 and CX3CR1 is a fundamental mechanism driving lung cancer. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med.191, 437–447 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amsellem, V. et al. Roles for the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 and CCL2/CCR2 chemokine systems in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol.56, 597–608 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng, X., Zhang, J., Xiao, Z., Dong, Y. & Du, J. CX3CL1-CX3CR1 interaction increases the population of Ly6C(-)CX3CR1(hi) macrophages contributing to unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced fibrosis. J. Immunol.195, 2797–2805 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okayasu, I. et al. A novel method in the induction of reliable experimental acute and chronic ulcerative colitis in mice. Gastroenterology98, 694–702 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Popivanova, B. K. et al. Blocking TNF-alpha in mice reduces colorectal carcinogenesis associated with chronic colitis. J. Clin. Invest.118, 560–570 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips, R. J. et al. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest.114, 438–446 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ananthakrishnan, A. N. et al. Statin use is associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.14, 973–979 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodríguez-Miguel, A. et al. Statins and colorectal cancer risk: a population-based case-control study and synthesis of the epidemiological evidence. J. Clin. Med.11, 896 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.De Schepper, S. et al. Self-maintaining gut macrophages are essential for intestinal homeostasis. Cell175, 400–415e13 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murai, M. et al. Interleukin 10 acts on regulatory T cells to maintain expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 and suppressive function in mice with colitis. Nat. Immunol.10, 1178–1184 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kostadinova, F. I. et al. Crucial involvement of the CX3CR1-CX3CL1 axis in dextran sulfate sodium-mediated acute colitis in mice. J. Leukoc. Biol.88, 133–143 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuboi, Y. et al. Blockade of the fractalkine-CX3CR1 axis ameliorates experimental colitis by dislodging venous crawling monocytes. Int. Immunol.31, 287–302 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marelli, G. et al. Heme-oxygenase-1 production by intestinal CX3CR1 + macrophages helps to resolve inflammation and prevents carcinogenesis. Cancer Res.77, 4472–4485 (2017b). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray, P. J. et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity41, 14–20 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mantovani, A., Allavena, P., Marchesi, F. & Garlanda, C. Macrophages as tools and targets in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.21, 799–820 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hashimoto, M. et al. Fibrocytes differ from macrophages but can be infected with HIV-1. J. Immunol.195, 4341–4350 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madsen, D. et al. The non-phagocytic route of collagen uptake: a distinct degradation pathway. J. Biol. Chem.286, 26996–27010 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kleaveland, K. R. et al. Fibrocytes are not an essential source of type I collagen during lung fibrosis. J. Immunol.193, 5229–5239 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White, G. E., Mcneill, E., Channon, K. M. & Greaves, D. R. Fractalkine promotes human monocyte survival via a reduction in oxidative stress. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol.34, 2554–2562 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karlmark, K. R. et al. The fractalkine receptor CX₃CR1 protects against liver fibrosis by controlling differentiation and survival of infiltrating hepatic monocytes. Hepatology52, 1769–1782 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Landsman, L. et al. CX3CR1 is required for monocyte homeostasis and atherogenesis by promoting cell survival. Blood113, 963–972 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lionakis, M. S. et al. CX3CR1-dependent renal macrophage survival promotes Candida control and host survival. J. Clin. Invest.123, 5035–5051 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ishida, Y. et al. Pivotal involvement of the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis for the recruitment of M2 tumor-associated macrophages in skin carcinogenesis. J. Invest. Dermatol.140, 1951–1961e6 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bonetti, P. O., Lerman, L. O., Napoli, C. & Lerman, A. Statin effects beyond lipid lowering–are they clinically relevant? Eur. Heart J.24, 225–248 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Bello, E., Zwergel, C., Mai, A. & Valente, S. The innovative potential of statins in cancer: new targets for new therapies. Front. Chem.8, 516 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ishikawa, S. et al. Statins inhibit tumor progression via an enhancer of zeste homolog 2-mediated epigenetic alteration in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer135, 2528–2536 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jang, H. J. et al. Statin induces apoptosis of human colon cancer cells and downregulation of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor via proapoptotic ERK activation. Oncol. Lett.12, 250–256 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Menter, D. G. et al. Differential effects of pravastatin and simvastatin on the growth of tumor cells from different organ sites. PLOS ONE6, e28813 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coimbra, M. et al. Liposomal pravastatin inhibits tumor growth by targeting cancer-related inflammation. J. Control Release148, 303–310 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang, J. & Patel, J. M. Role of the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis in chronic inflammatory lung diseases. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med.3, 233–244 (2010). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu, Y. R. A. et al. Defective antitumor responses in CX3CR1-deficient mice. Int. J. Cancer121, 316–322 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan, Y. et al. CX3CR1 identifies PD-1 therapy-responsive CD8 + T cells that withstand chemotherapy during cancer chemoimmunotherapy. JCI Insight3, 563 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Robinson, L. A. et al. The chemokine CX3CL1 regulates NK cell activity in vivo. Cell. Immunol.225, 122–130 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang, X., Wei, H., Wang, H. & Tian, Z. Involvement of interaction between fractalkine and CX3CR1 in cytotoxicity of natural killer cells against tumor cells. Oncol. Rep.15, 485–488 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.