Abstract

Conventional drug delivery systems are challenged by concerns related to systemic toxicity, repetitive doses, drug concentrations fluctuation, and adverse effects. Various drug delivery systems are developed to overcome these limitations. Nanomaterials are employed in a variety of biomedical applications such as therapeutics delivery, cancer therapy, and tissue engineering. Physiochemical nanoparticle assembly techniques involve the application of solvents and potentially harmful chemicals, commonly at high temperatures. Genetically engineered organisms have the potential to be used as promising candidates for greener, efficient, and more adaptable platforms for the synthesis and assembly of nanomaterials. Genetically engineered carriers are precisely designed and constructed in shape and size, enabling precise control over drug attachment sites. The high accuracy of these novel advanced materials, biocompatibility, and stimuli‐responsiveness, elucidate their emerging application in controlled drug delivery. The current article represents the research progress in developing various genetically engineered carriers. Organic‐based nanoparticles including cellulose, collagen, silk‐like polymers, elastin‐like protein, silk‐elastin‐like protein, and inorganic‐based nanoparticles are discussed in detail. Afterward, viral‐based carriers are classified, and their potential for targeted therapeutics delivery is highlighted. Finally, the challenges and prospects of these delivery systems are concluded.

Keywords: abiotic nanomaterials, genetically manipulation, nanoparticles, non‐viral vectors, surface modifications

The organic and viral‐based genetically engineered carriers are classified, and their potential for targeted therapeutics delivery is highlighted. Also, the challenges and prospects of these delivery systems are concluded.

1. Introduction

Low solubility, rapid clearance, and adverse effects are the main limitations of conventional drug administration approaches. To overcome these inadequacies, various organisms and nanocarriers have been developed.[ 1 , 2 ] Nanotechnology has introduced operative nanoplatforms in drug delivery systems that have led to various progressive materials for the safe delivery and release of a wide variety of therapeutic agents into targeted sites.[ 3 ] As a result, an ordered structure must be developed that could allow for a continuous release of the drug while overcoming first‐pass metabolism and pharmacological adverse effects. In recent years, nanostructures have been used to achieve continuous drug release with fewer adverse effects and a potent pharmacological response. Overexpression of the efflux pump, self‐repairing capability, modified targets, or enhanced drug metabolism all enable cancer cells developing a defense mechanism. These factors may have an impact on the treatment process, increasing the utility of specific nanocarriers that can bypass all of the defense mechanisms. These nanostructures are also used as a carrier molecule or transporter for vaccinations, drugs, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), proteins, and other substances.[ 4 ] Although nanocarriers might carry various agents to the targeted sites, the design and synthesis of these nanomaterials show some disadvantages in pharmaceutical applications. As a result, a solution is required to improve the control of the particles.[ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] For instance, the shape and size of modified carriers can be precisely controlled, which can offer the exact control on the attachment of drugs.[ 9 ] Also, engineered materials can be used as noble candidates to greener, eco‐friendly, and high‐throughput systems to synthesize and assemble nanomaterials, even on the manufacturing scale.[ 10 ] Additionally, genetic engineering propose control over the macromolecules used to construct nanocarriers. This ability permits exclusive properties such as specific biodegradation profiles and fully modified polymer and nanocarrier structures to be engineered and adjusted as required in some specific applications.[ 11 ]

Genetic engineering and bio‐fabrication are used as a unique method to synthesize organic nanoparticles such as protein‐based polymers, which can create structures with a thin molecular distribution. Different protein‐based polymers such as elastin‐based polypeptides can be synthesized using chemical methods. Though, some disadvantages get up when more complex structures require to be made, such as challenges related to purification and polydispersity and the effect of by‐products on the physical properties of the final product. The beginning of recombinant DNA technology and cloning techniques opened up a novel way in order to the manufacture of synthetic organic nanomaterials. This new assay intended several problems derived from the chemical synthesis methods, such as polydispersity, the need for organic solvents, and elimination of their residues.[ 12 ] The development of drug delivery systems using such biopolymers, including silk‐elastin‐like proteins (SELP), silk‐like proteins (SLP), elastin‐like protein (ELP), and polysaccharides has improved significantly over the years.[ 13 , 14 ] Inorganic nanoparticles such as gold, silver, copper, iron oxide, and zinc, are biocompatible and nontoxic with considerably stable structure compared with organic nanomaterials. These nanomaterials are highly considered drug delivery carriers because of their great cellular uptake capability and low toxicity.[ 15 , 16 ] Functionalizing inorganic nanomaterials using genetically engineered polymer nanostructures can enhance their biocompatibility and bio‐functionality. The synthesis of plasmonic nanomaterials through genetic engineering of SELPs is an example of catalyzing a more comprehensive examination of the dynamic control in plasmonic nanoplatforms and provided a suitable carrier in drug delivery.[ 17 ]

Recently, the mixture of viral and bacterial nanocarriers with small molecules allowed encapsulating drugs and modified genetic materials into microorganisms. This assay permits the delivery of the therapeutic cargo encapsulated in the organisms to targeted sites due to the enchanting targeting potentials of these organisms.[ 18 ] Virus‐like particles (VLPs), for example, have an effective transfer strategy for delivering their contents by mimicking the virus's mechanism. VLPs provide numerous benefits, including rapid synthesis, facile scaling, and high cell membrane penetration.[ 19 , 20 ] The probability of genetically modifying the proteins inside VLPs brands them a promising system to various applications. The viruses are effective immune activators and natural delivery vectors of genetic materials to their host; therefore, VLPs can be promising carriers for drug delivery.[ 21 ] The different types of these engineered viral platforms are non‐enveloped VLPs, such as hepatitis B core antigen (HbcAg), cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV), cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV), tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), Johnson grass chlorotic stripe mosaic virus (JgCSMV), adeno‐associated viruses, P22, MS2, bacteriophage QB (Qubevirus durum), and reovirus that have been chemically or genetically engineered as drug delivery or vaccine carriers.

The current review focuses on drug delivery organisms and nanocarriers. An overview of the use of genetically engineered organic, modified‐inorganic, and viral nanostructures for drug delivery, as well as their frailties and advancements, are presented. In this review, we present a systematic overview of the recent developments and applications of genetically engineered nanoparticles in drugs, pro‐drugs, peptides, as well as nucleic acid components delivery. Ultimately, challenges and future tendencies in this area are emphasized, where such engineered assays will be of great importance and have the potential to be translated from benchtop to bedside (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the synthesis of the genetically engineered organic, inorganic, and virus‐like nanostructures for drug delivery applications.

2. Genetically Engineered Compounds: Overview

Drug delivery systems can aid in the regulation of drug loading, controlled release, and release site, resulting in improved therapeutic outcomes and decreased toxicity and increased hydrophilicity, circulation time, and drug protection from undesired degradation.[ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ] Polymers are attractive options for drug delivery because of their ability to solve many strong drugs, stability, and chemical compounds via polymer chain alteration, copolymerization, block polymer length, and cross‐link with both side groups and the polymer backbone.[ 26 , 27 ] Generally, polymers fall into one of two categories such as natural polymers (starch, chitosan, gelatin, collagen, and albumin) and synthetic polymers (including polyorthoesters, polyesters, and polyanhydrides). Although synthetic polymers have physicochemical properties and high diversity, they have been challenged industrially for low compatibility, bulk hydrolysis, and acid degradation yields for drug delivery systems. As a result, using convergent science, focused research has been considered to overcome the mentioned limitations using natural polymers, genetic engineering, and biosynthesis.[ 28 , 29 ] In addition, with the development and complexity of drugs, the control of their properties and their transfer in the drug delivery systems require more accuracy that synthetic polymers cannot achieve more.[ 30 ]

Genetic engineering is used as a recombinant method to synthesize proteins or sometimes polysaccharide‐based polymers. This may make these structures have a narrow molecular weight distribution besides a well‐defined monomer composition, stereochemistry, and sequence. Genetically engineered protein‐based polymer nanocarriers possess advantages for gene/drug delivery such as biocompatibility, degradability without acidic degradation products, and homogeneity. Since chemical polymerization methods lead to the distribution of heterogeneous molecular weights of polymers, genetic engineering methods are considered for researches due to the synthesis of materials with homogeneous molecular weight distributions.[ 31 , 32 ] Therefore, polymers consisting of polypeptide chains provided through genetic engineering have useful and unique properties that with natural decomposition of these products, minimal toxicity is indicated. Another advantage of producing recombinant protein polymers is that they are homogenous and repeatable from batch to batch for use in the pharmaceutical industry. Recombinant proteins are biodegradable, stimuli‐responsive, have an increased therapeutic index, are targeted, have the ability to modify, can combine different amino acid sequence modules to create different libraries in amino acid synthesis, and have more detailed control over structure–function relationships. Recombinant proteins are biodegradable, stimuli‐responsive, have an increased therapeutic index, are targeted, have the ability to modify, can combine with different amino acid sequences to produce different amino acid libraries, and have more detailed control over structure–function relations.[ 13 , 33 ] However, in order to synthesize these genetically engineered polymer‐based proteins, first, a macromolecule (protein) is designed and then oligonucleotide (gene) encoding a protein is synthesized chemically and litigated into a recombinant vector. Finally, purification step is done. One of the most convenient methods is immobilized metal affinity chromatography.

Furthermore, the low cost of larger‐scale production in biomedical systems has resulted in the use of large‐scale recombinant protein polymers in a variety of important therapeutic applications, including drug delivery. Consequently, there has been an increased interest in recent years using recombinant protein‐based biopolymers such as SLP, ELP, and SELP in genetic engineering for the development of drug delivery systems. Inverse temperature transition actions, elasticity and amphiphilic, stabilization through physical cross‐links, and greater mechanical strength are all advantages of ELP‐ and SLP‐based engineered protein for drug delivery. Their communal features include enzyme‐controlled degradation, compatible, customizable chemistry and biomaterial characteristics, consistency in polymers, adaptable drug loading, and comparatively low‐cost construction and scale up.[ 13 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]

Recently, cell membrane coating technology showed great consideration in the field of nanomedicine. Particularly, cell membrane‐coated nanoparticles, especially engineered NPs have established to be efficient drug delivery systems due to their long circulation times.[ 37 , 38 ] A novel assay in order to construct targeting ligands arises from the progresses in genetic engineering. This genetic engineering indicates the control of protein expression levels on the cell membrane through gene transfection. C1498 gene transfection for overexpression of VLA‐4 and extraction of the genetically modified membrane‐coated polymer nanoparticles core loaded with dexamethasone can be used to treat pulmonary inflammation. In fact, the biomimetic cell membrane exhibits a higher affinity for target cells that overexpress vascular cell adhesion protein 1 (VCAM‐1), thus increasing pulmonary inflammation more effectively by increasing the accumulation of VLA‐NP in the lung.[ 39 ] In the following section, genetically engineered organic‐based macromolecules (such as proteins and polysaccharides) are represented. Then, genetically engineered organic‐based macromolecules coated inorganic materials are introduced.

3. Genetically Engineered Organic‐Based Nanoparticles

Natural polymers have received much attention in many medical fields as wound dressings, adsorbents, drug delivery, and medical scaffolds due to properties such as metabolic compatibility, nontoxicity, and resemblance to body tissue. The most important natural polymers in this regard are polysaccharides, proteins and polyamides, and polyesters. Methods used to produce natural polymers include:[ 40 , 41 ]

Direct use of biodegradable material (cellulose)

Direct consumption of degradable animal polymers (collagen)

Genetic engineering for better natural polymers (ELPs, SLPs)

Microbial fermentation and access to materials such as polyhydroxyalkanoates

Genetic engineering methods, which are the main focus of this review, will be discussed in detail in the following sections. Typically, nanosizing is a method to overcome poor aqueous solubility of drugs in pharmacology. Although cellulose and its derivatives have dimensions of 5–30 nm, they are widely used as nanocarriers in stabilization and drug delivery. For instance, Valo et al. have described a nanofibrillar cellulose matrix as stabilizer for nanoparticles to protect, store, and release hydrophobic drugs or genetically modified fusion proteins.[ 42 ] At this work, anti‐solvent precipitation method was used to precipitate itraconazole, hydrophobic drug nanoparticle, in order to synthesis nanoparticles with either hydrophobics or genetically modified fusion protein and then binded to the cellulose. The results showed that by encapsulating the nanoparticles with cellulose, the processability and solubility rate were improved. Another type of recombinant polypeptide synthesized by genetic engineering technology is collagen mimetic peptide (CMP). CMP has numerous unique advantages including excellent structural controllability, high bioactivity, high biocompatibility, and elimination of animal‐derived viruses as well as wide range of functions. Luo and co‐worker investigated the self‐assembly mechanism of CMP using hydrophilic glycidol and hydrophobic Y‐glycidyl ether oxypropyl trimethoxysilane.[ 43 ] The results revealed that the agent's hydrophilic interactions and hydrophobicity on CMP sub‐chains produce long‐term nucleation‐growth, which altered the structure and morphology of CMP (Figure 2 ). The interaction through hydrophilic agents promotes the formation of nanofiber structures, whereas hydrophobic agents promote to microspheric structures, which could be beneficial in various biomedical applications.

Figure 2.

A) Schematic and B) representing SEM images of the self‐assembly of pure collagen (CMP), (GCD/CMP), (GLH/CMP). Reproduced with permission.[ 43 ] Copyright 2021, Springer Nature. Abbreviation: CMP: Mimetic peptide; GCD/CMP: Glycidol‐modified CMP. GLH/CMP: Y‐glycidyl ether oxypropyl trimethoxysilane‐modified CMP.

Elastin is one of the structural proteins present in connective tissue and has elastic properties. The amino acid in the structure of elastin is “hydroxyproline,” which is also present in the structure of collagen and forms a hydrogen bond and strengthens the structure of collagen.[ 12 ] From this perspective, one of the synthetic biopolymers that have many applications in medicine and biotechnology is elastin‐like polypeptide. ELP is a synthetic biopolymer engineered and derived from the amino acid sequence contained in the hydrophobic parts of tropolastin, which has the ability to self‐aggregate as an intelligent polymer. The amino acid sequence of the elastin‐like polypeptide often consists of a repetitive sequence (palindrome) consisting of five amino acids VPGXG. X can be any amino acid except proline. The entry of proline alters the hydrophobic bonds to bind the ELP. ELP, on the other hand, is a heat‐reactive polypeptide that has a temperature‐dependent self‐aggregation property. For this synthetic protein, a reaction temperature is defined as the reverse transfer temperature (Reversible or Inverse Transition Temperature) or the minimum critical temperature of the solution.[ 44 ] Fabrication formats (e.g., films and hydrogels) also improve utility of polymer‐based systems.[ 45 ] ELP are thermally responsive polypeptides that are soluble in solutions at 37 °C, but which aggregate above 42 °C. Moreover, as drugs become more complex, the control of drug delivery becomes more difficult.[ 46 ] Therefore, the properties required to match drug delivery demands need a level of customization that has not been achievable using synthetic polymer drug delivery systems. Unique features make ELPs perfectly suited to address current drug delivery challenges and lead to the development of ELP‐based therapies for the treatment of diseases—such as cancer and diabetes—and wound healing, and the development of bioengineering methods facilitates the design and fabrication of biocompatible, responsive, and multi‐faceted drug delivery systems. Many studies have been done on the thermosensitive ELP with reversible nano‐ and micro‐particles via coacervation.[ 47 ] The processes of ELP phase transition, biodegradation, pharmacokinetics, and tumor localization in the nude mice with labeled method have been well‐described in a study by Liu et al.[ 48 ] These researches were successfully labeled with two different ELPs with 14C; thermal responsive ELP1 showed that accumulation was higher in heated tumors than in cold tumors. ELP optimal molecular size determination is important because it affects the success rate of therapeutic agents to cross the tumor vessels. On the other hand, Na et al. have investigated enhanced cellular uptake of drug in tumor cells using synthase the ELP‐liposome‐drug conjugate (Figure 3 ).[ 49 ] They studied thermosensitive drug release properties and evaluated its cellular uptake efficiency under hyperthermic and normothermic conditions. Also, drug accumulation was carried out with flow cytometry and confocal microscopy inside tumor cells. The result has shown that higher ELP‐liposome‐drug conjugate internalization occurs in the ELP‐modified liposomes when compared to ELP‐unmodified liposomes. In vivo laboratory imaging results showed that intrarenal concentrations and distributions for ELP‐63 and ELP‐95 proteins are higher in the renal cortex due to their lower molecular weight, and the dose is approximately twice that of high‐molecular‐weight ELP proteins within the cortex. Other researches have shown that ELP‐conjugated cargo and their accumulation increase with repeated cycles of hyperthermia. Also, in hypothermic tissues, they have a lower toxicity than hyperthermic tissues. Therefore, with this method, they achieved controlled drug delivery due to the difference in their accumulation and removal in tissues in drug delivery.[ 50 ]

Figure 3.

A) Synthesis of ELP‐modified liposomes. B) Confocal images of HeLa cells incubated in the culture media with DOX: a) Control, b) PEG‐liposomes, and c) ELP‐modified liposomes. C) Mean fluorescence intensity of liposomes identified through the flow cytometry assay: a) Control, b) PEG‐liposomes, and c) ELP‐modified liposomes. Mean and S.D. are shown (n = 3). Reproduced with permission.[ 49 ] Copyright 2012, Elsevier. Abbreviation: ELP: Elastin‐like protein; DOX: Doxorubicin; PEG: Polyethylene glycol.

Another type of genetically engineered is silk‐like polymers (SLPs) with structures consisting of amoebic silk‐like blocks Gly–Ala–Gly–Ala–Gly–Ser. Actually, silk is a filamentous protein made by spiders and insects such as silkworms. There is a variety of silks that exist naturally. They have excellent mechanical properties, high strength, ductility, biocompatibility, and biodegradability. Also, silk materials are not limited to natural fibers, but some silk materials have been modified. Like chemically modified silk materials, composite materials and synthetic materials are decomposed and synthesized by enzymatic polymerization which can be a natural matrix effective for drug delivery.[ 51 , 52 ] Concerning genetically engineered silk‐like polymers, they have been mainly restricted to those designed on the repetition of the sequences [GGAGQGGYGGLGSQ‐GAGRGGLGGQGGAG] and [GPGGYGGPGQQGPGGYAPGQQPSGPGS] from the silk produced by the Nephila clavipes major ampullate glands 1 and 2, respectively.[ 14 ] Some modifications of those base sequences have also been discovered. Some of them were applied to control the grade of crystallinity, though some other modifications have been added to functionalize the polymers, such as the incorporation of RGD cell attachment sequences. They commonly are deliberated to be block copolymers with greatly conserved repeats of short side‐chain amino acids as hydrophobic blocks and short sequences.[ 14 ]

Because polymers consist of only silk blocks with very low aqueous solubility and low flexibility, copolymerizing them with elastin‐like blocks increases their flexibility and hydrophilicity while reducing total crystallization. Block copolymers such as SELPs are obtained using genetic engineering techniques that can be used to control physicochemical properties by modifying the composition and sequence of the copolymer.[ 36 ] In general, the structure of these polymers is denoted by the symbol, where they are a silk‐like block denoted by s, which is composed primarily of GAGAGS repeats, and elastin‐like sequences with the VPGVG amino acid sequence, denoted by the symbol E.[ 53 , 54 ] The potential uses of these polymers in drug delivery systems and tissue engineering are under study. Although, in spite of the growth in studies with SELP, little is recognized about the crucial self‐assembly properties of these polymers.[ 55 ] However, increasing the number of repeats of elastin blocks reduces the crystal structures of silk and leads to an increase in water solubility of the entire SELP block at low temperatures. This property is very important for purification of protein polymers and pharmaceutical formulations. Therefore, in drug delivery applications, this SELP with the interactions of hydrophobic blocks and the formation of micelle core in water with self‐assembly force as nanocarriers have been highly considered by researchers.[ 56 , 57 ]

By regulating the ratio of elastin to silk blocks, various shapes such as nanoparticles, hydrogels and nanofibers can be produced reversibly or irreversibly. Due to the outstanding physical and unique properties of silk and elastane copolymers, they have been extensively studied in the fields of tissue engineering and drug delivery. Xia et al. have investigated the self‐assembly behavior of SELPs by adjusting the ratio of silk‐to‐elastin blocks in two stages.[ 58 ] The results showed that increasing temperature and the resulting hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions led to nanostructures with reversible or irreversible properties self‐assembled. They for the first time showed that recombinant SELPs under a two‐step self‐assembly process in aqueous solutions were first formed by hydrogen bonding between blocks to form micellar‐like particles with mainly silk block GAGAGS which are hydrophobic units as the core structure and elastin blocks as corona, which can be controlled by adjusting the ratio of silk blocks to elastin (Figure 4 ). In the second stage, the behavior of these micelles in response to temperature was investigated. By fine‐tuning the ratio of silk blocks to elastin, various structures such as nanoparticles, hydrogels, or nanofibers were produced in a reversible or irreversible manner. Since it was found that Her2 overexpression in tumors is higher than that of healthy tissue, a new approach is developed for agents targeting the Her2 in cancer treatment. In this ELP field, Florczak et al.[ 59 ] designed various hybrids of spider silk with binding domain different from Her2 receptor by genetic engineering to control the drug delivery systems (Figure 5 ). The behavior of release of doxorubicin (DOX) on the aqueous solution properties of MS1, H2.1MS1, and H2.2MS1 spheres was investigated. The results showed that release rate at pH 4.5 were faster than it was at pH 7.4.

Figure 4.

Self‐assembly of micellar‐like nanoparticles in T‐responsive. Reproduced with permission.[ 58 ] Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society.

Figure 5.

A) Bioengineering of the spider silk. B) Cellular uptake of the silk spheres on the SKOV3 and SKBR3 cells, which were treated with spheres prepared of fluorescently labeled control MS1 and silk proteins H2.1MS1 and H2.2MS1. Scale bar = 10 µm. C) Behavior of release of DOX. Reproduced with permission.[ 59 ] Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society.

One of the most significant parameters that can be used to change the properties of copolymers is how the sequence of monomers is located in the copolymers. The polymerization procedure and the sequence distribution of various monomer units in the copolymer depend on the placement, reaction ratio, and instantaneous composition of the monomer. The sequence distribution of monomers or amino acids by controlling the polymerization temperature, concentration of reactants, and the process can lead to a variety of copolymers.[ 60 , 61 ] Recombinant DNA methods are one of the techniques to attain precise control over macromolecular structure. Protein polymers synthesized using genetic engineering contain amino acids such as sequential polypeptides and poly (amino acids), which are homopolymers or random copolymers made by polymerizing an amino acid or a mixture of amino acids.[ 62 ]

Micelles with hydrophilic blocks (poly L‐amino acid) and hydrophobic (poly ethylene oxide) composed of block copolymers using chemical methods or biosynthesis have been proposed as drug carriers to increase blood circulation.[ 63 ] However, due to the lack of resistance of these polyethylene's, the application caused a number of limitations. The development of polyamide‐derived biomass as an engineered biopolymer has created an emerging interest in sustainable chemistry and engineering. High‐performance natural materials, including silk and elastin, are composed mainly of poly (amino acids) and small amounts of short peptides, suggesting that poly (amino acids) could be substituted for oil‐derived polymers. However, for the creation and development of biomass‐based polymers such as silk and elastin, the synthesis and design of poly (amino acid) materials is under consideration.[ 64 ] This synthetic methodology allows the precision of genetic protein synthesis in the synthesis of new macromolecular structures for drug delivery. The following are examples of the application of these polymers in the field of drug delivery, such as ELPs, ELPBCs, SELPs. Table 1 reports sample ELPs/SELP‐based sequences for drug delivery applications.[ 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 ]

Table 1.

Samples Elastin‐like protein (ELPs)/silk elastin‐like protein (SELP)‐based sequences in the drug delivery fields

| Functions | Material Format | Drug/targeting | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELPs | Micelles | Anticancer cell | [65] |

| SELP‐47K | Film | Antibiotic/Ciprofloxacin | [66] |

| SELP | Matrix‐metalloproteinase | Doxorubicin | [67] |

| ELPs | Hydrogel | Wound repair | [68] |

| ELPBCs | Micelle | Anticancer drug | [69] |

| ELP | Gel‐like | Radionuclide | [70] |

| Elastin‐mimetic polypeptide | Tailor‐made | Doxorubicin and rhodamine‐GFLG | [71] |

| ac‐ELP‐H1 | Particle | c‐My | [72] |

| ELP | Particle | Doxorubicin | [73] |

| SynB1–ELP | Particle | Doxorubicin | [74] |

SELP, silk‐elastin‐like proteins; SLP, silk‐like proteins; ELP, elastin‐like protein; ELPBCs, elastin‐like polypeptide diblock copolymers.

Tailor‐made polysaccharide depending on multiple structures has been offered as a novel concept in recent years, which will open new windows for biomaterial universe.[ 75 , 76 ] Xanthan gum is an essential food ingredient and is produced by Xanthomonas campestris (X. campestris).[ 77 , 78 ] It has a cellulose‐like backbone with a (3 1) linked ‐d‐Man‐(2 1) chain, ‐β‐d‐GlcA‐(4 → 1). Every second glucose unit has a —d‐Man side chain (Man, mannose; GlcA, glucuronic acid).[ 79 ] In a recent study, eight polysaccharides have been synthesized with uniformly distributed repeating units and different rheological properties (Figure 6 ).[ 80 ] The synthesized polysaccharides were produced in X. campestris CGMCC 15155 using marker less gene knockout and gene overexpression methods. The findings revealed that their distinct homogenous primary structures controlled their individual secondary structures and rheological features, particularly the terminal mannose, pyruvyl group, and acetyl group connected to the internal mannose of the side chain. Both the terminal mannose residue and the inner acetyl group might stabilize the double helix structure; however, the terminal mannose residue improved while the internal acetyl group decreased solution viscosity and modulus.

Figure 6.

The primary structures of customized xanthan in Xanthomonas campestris and their biosynthetic pathways.[ 80 ]

4. Genetically Engineered Organic Compounds Decorated Inorganic Nanoparticles

Inorganic nanomaterials have been extensively investigated in biomedical sciences for the past few decades due to their exciting physicochemical properties. Through synthesis of various kinds of nanomaterials and modifying them, new horizons can open up for exciting biomedical applications. For instance, modified nanomaterials are employed for magnetic separation, as carrier for targeted drug and gene delivery, and diagnostic imagining. For instance, by giving them a magnetic resonance contrasts or making them fluorescent it is easy to track them once implanted in the body.[ 5 , 24 ] Generally, this kind of nanomaterials contain two parts: metallic nanoparticles constitute the core part, and polymeric (mainly) biomaterials are used in the shell or surface part. On the one hand, these methods arrange a proper physical layer for conjugation of bio macromolecules; on the other hand, they prevent unwanted physiochemical interaction in the body.[ 81 , 82 ] Furthermore, their stability and protection from microbial attack, by comparison with organic nanoparticles, has made them even more important for biomedical applications. Inorganic nanomaterial can be classified in four separate groups based on their origin: metal‐based nanoparticles, carbon‐based nanoparticles, ceramic nanoparticles, quantum dots metal‐based nanoparticles. Metal‐based nanoparticles, such as gold, silver, copper, iron oxide, and zinc, have attracted scientist over a century. Synthesizing nanoparticles in different shapes (nano cage, nano shell), size, and their surface functionalization, which provides a wide range of potential applications, can be named the most important advantages of this class of biomaterials.[ 83 , 84 , 85 ]

For many years metallic nanoparticles have been investigated for various biological applications including, bioactive delivery, drug delivery, and preconcentration of target analytes, as a vehicle for gene delivery, and imaging.[ 86 ] Generally, metallic nanoparticles can be categorized into noble metal nanoparticles (especially gold and silver) and magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) (iron oxide). Both have promising features that draw attention to themselves and reduce side effects of conventional treatments. Noble metallic present a great application in optical, imaging fields, photo thermal therapy on account of their surface plasmon resonance. For instance, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are used in therapeutic strategy due to their ability to convert light into heat. An example includes AuNPs that have been injected into tumor systematically or locally to increase the temperature to a sufficient level under laser irradiation, as a consequence inducing localized cell death. In addition, these nanoparticles possess an excellent antimicrobial activity toward numerous microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Even though this raises concerns regarding the affection on healthy human cells by various mechanisms, burgeoning technology has allowed synthesizing them in a novel method to reduce their adverse effects on human bodies.[ 87 , 88 ] Numerous studies have been reported on the use of genetically engineered polymers modified with inorganic nanomaterials. To tune the temperature response in plasmonic gold, genetic engineering has been used to design thermo‐responsive and photonic core–shell nanoparticles. Using gold nanoparticles as core, researchers synthesized SELP polymers with amino acid sequences [(GVGVP)4(GGGVP)(GVGVP)3(GAGAGS)4] as shells and investigated temperature response on self‐assembly of the SELP shell. It was indicated that the β‐silk structure stabilizes the structure of nanoparticles in response to the temperature. Also, with increasing temperature to 60 °C, nanoparticles accumulate and form a square state (Figure 7 ).[ 17 ]

Figure 7.

Thermoresponsive plasmonic gold/silk‐elastin protein core–shell nanoparticles. A) Schematic of functionalized gold nanoparticles with SELPs. B) (a) Representative TEM images of functionalized gold nanoparticles in the individual form at 25 °C and (b) in aggregated form when heated to 60 °C. C,D) Variable‐temperature UV−vis extinction spectra of the functionalized gold nanoparticles at room temperature and when heated to 60 °C. E) Thermal cycles of functionalized gold nanoparticles between 25 and 60 °C were monitored by UV−vis spectroscopy indicating good reversibility. Reproduced with permission.[ 17 ] Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society.

MNPs display a unique magnetic and heat‐medicated inherent as well as being biodegradable and biocompatibility. Due to their innate characteristics, MNPs are easily used in targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia‐based therapies. Hyperthermia based on the heat that these nanoparticles generate in an alternating magnetic field.[ 89 , 90 , 91 ] Furthermore, by applying external magnetic fields and under specific conditions, the drug loaded on MNP can be directed to specific point in body, and accuracy of it depends on the depth of the targeted part. Magnetite (γ‐Fe2O3) and magnetite (Fe3O4) superparamagnetic nanoparticles are the major MNPs used in drug delivery.[ 91 ]

A magnetic responsive system was developed using ELPs and superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs). The magnetic characteristics were attained by entrapping SPIONs in the polymeric matrix to manage microparticle targeting and monitoring. The results showed that prepared microparticles showed a round shape and brown color, suggesting the successful encapsulation of SPIONs in the polymeric matrix. Furthermore, fabricated microparticles demonstrated cytocompatibility toward in vitro cell model and indicated efficient drug encapsulation with a two‐phase release profile. Taken together, this study highlighted the drug delivery potential of these systems for various biomedical applications.[ 92 ]

Recently, carbon allotropes: fullerenes, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene oxide (GO), carbon and graphene, quantum dots, and their size, shape, and surface properties, as well as antimicrobial behavior, have received tremendous attention and have opened up a gateway for pharmaceutical applications.[ 93 ] Furthermore, a significant part of the human body comprises carbon, so it can be said to be a biocompatible material. The application as a drug delivery system is common in carbon‐based nanoparticles; they can be used to carry biological molecules including DNA, proteins, and drugs. Drug compounds are loaded on the surface or inside these structures. Targeting and simultaneous transfer of two or more compounds are other features of these particles in drug delivery; especially the graphene‐based nanoparticles have a remarkable position in this area due to their unique structure, high surface area, and existence of several functional groups, including carboxyl, epoxy (in GO), suggesting an excellent loading capability for a variety of fluorescent probes and drugs.[ 94 ]

Elastin‐like polypeptide was used to functionalize graphene‐based nanomaterials in order to investigate stimuli‐responsiveness behavior and control their physical, colloidal properties such as bioactivity of graphene. By combining the thermal responsiveness of ELP with photothermal capabilities of GO sheets, the fabricated hybrids demonstrated responsiveness toward nIR light. Furthermore, the ELP coating inhibited the aggregation properties of GO sheets at higher concentration and enabled the dispersion in organic solvents. Such graphene–protein nanocomposite materials showed promising stimuli‐responsive properties for drug delivery application (Figure 8 ).[ 95 ]

Figure 8.

A) Schematic illustration on the preparation of stimuli‐responsive graphene‐based materials functionalized with elastin‐like polypeptides. B) Images of ELP(V50)‐treated graphene oxide solutions before and after the inverse temperature transition (a); image of significant and reversible aggregation of ELP(V50GB)‐treated graphene oxide after the inverse temperature transition (b). c) The nIR‐induced aggregation of ELP(V50GB)‐treated graphene oxide is shown in a series of photos taken over the course of 4 min. The arrow indicates the nIR beam's position. C) Fluorescent images of cells remaining on a) RGD‐ELP(V40GB)‐treated reduced graphene oxide and b) ELP(V40GB)‐treated reduced graphene oxide. c) Average cell number and area of cells on treated reduced graphene oxides. Reproduced with permission.[ 95 ] Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society. Abbreviation: ELP: Elastin‐like protein.

5. Nanoscale Genetically Engineered Viral Platforms

Nanotechnology facilitated the way, which we prevent, detect, and cure diseases. This progress has been made feasible by viruses, which can operate as prefabricated nano‐scaffolds with unique features that can be easily modified.[ 96 ] Viruses are called natural nanomaterials as they have a genetically content, such as nucleic acids, encircled through a protein coat capsid and are in the size of 20–500 nm. The removal of genetic biomaterial results in an empty capsid that can be used to host drugs, enzymes, antibodies, or aptamers. These genetic engineering leads to precision drug delivery and targeted therapy. VLPs are nanoscale constructs composed of assembled viral proteins that are non‐infectious because they lack viral genetic material. The viral structural proteins can be expressed and self‐assembled in a variety of live or cell‐free expression methods, after which the viral structures can be assembled and reconstructed. VLPs have unique properties that allow them to create innovative platforms for medicine and biotechnology by combining techniques from each of these disciplines.[ 97 ] The following sections describe some chemically or genetically engineered VLPs that have been used as a vehicle for drug delivery or vaccine carriers. Recently different ligands have been functionalized to VLPs, and their targeting capacity has been examined in vitro and in vivo, which have been proposed to use as vehicles for cargo delivery as shown in Figure 9 .

Figure 9.

Virus‐like particles (VLPs) act as highly effective drug delivery vehicles. The surface of VLPs modified and functionalized with biomolecules. These ligands can be used to target specific cells, which can overcome the numerous challenges with delivering therapeutic cargo. After extravasation, VLPs target specific cells and trigger internalization while escaping the immune system. The VLPs escape the endosome after endocytosis and subsequently disassemble to release their cargo.

Viral capsids are most attractive natural structures for variety of biological applications due to their extreme stability in high temperatures, across a wide range of pH, and in organic solvent–water mixtures. Because of these characteristics, as well as their inherent biocompatibility, viruses have been developed as actively targeted delivery platforms, which can improve recent drug delivery methods.[ 98 , 99 ] In the current section, different nanostructures based on genetically engineered viruses and their application in drug delivery will be reviewed.

5.1. MS2

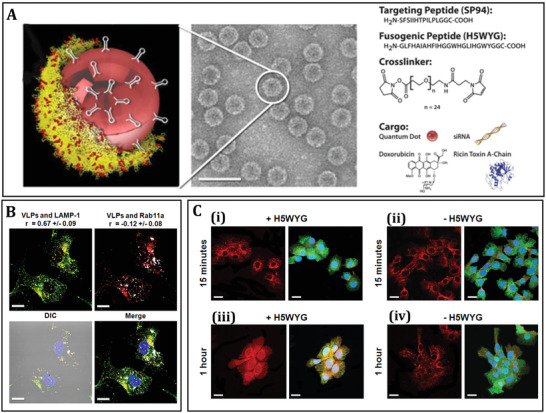

MS2 bacteriophage‐derived VLPs are icosahedral capsids with 22–29 nm in diameter and are formed by self‐assembling 180 copies of a single coat protein (CP). These VLPs are a unique delivery platform, and their desirable properties made them a popular research field in recent years due to many reasons. First, these can be used as a carrier for bacteriophage capsids to transfer epitope peptides, Ribonucleic acid (RNAs) or DNAs, and drugs in a cost‐effective and convenient manner. Second, they can act as excellent adjuvants, inducing both arms of immune responses.[ 100 ] Because of their rapid assembling nature in the presence of nucleic acids, researchers succeeded to encapsulate DOX, cisplatin, 5‐fluorouracil, siRNA cocktails, and protein toxin (ricin toxin A‐chain (RTA)) inside modified MS2 VLPs. Similarly, MS2 VLPs have been used for the selective distribution of chemotherapeutic drugs human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HCC) after functionalizing with a displayed targeting peptide (SP94). At sub‐nanomolar drug concentrations, all drug formulations tested with this platform resulted in selective cytotoxicity. This experiment used MS2's potential to encapsidate nucleic acids to demonstrate that delivering different anti‐tumor agents within VLPs caused cancer cells growth arrest and apoptosis. These modified VLPs had a great affinity for HCC cells, with limited uptake in healthy cells, and have a cytotoxic effect at minimal dosage. The SP94‐targeted VLPs encapsidated with drugs such as DOX, cisplatin, and 5‐fluorouracil have shown selective destruction of the HCC cell line Hep3B even at the lowest concentration (1 nm) of drug loading. In addition, at <150 pm concentration of siRNA, encapsidated SP94‐targeted VLPs suppressed the expression of cyclin family members, and induced growth arrest and apoptosis in Hep3B. Similarly, without damaging the control cells, nearly 100% of Hep3B cells are killed by MS2 VLPs loaded with RTA (at a concentration of 100 fm) and modified to co‐display SP94 targeting peptide and a histidine‐rich fusogenic peptide (H5WYG) that promotes endosomal escape. Because of their tolerance of multivalent peptide display and capacity to selectively encapsidate a range of cargos, MS2 VLPs induce selective tumor cytotoxicity in vitro (Figure 10 ).[ 101 ]

Figure 10.

Bacteriophage MS2 virus‐Like particle‐based cell‐specific delivery induces selective cytotoxicity in tumor cell. A) The procedure of developing HCC‐specific MS2 VLPs that encapsulate different therapeutic and imaging components is depicted in this diagram. Using a suitable cross‐linker, nanoparticles (e.g., quantum dots), protein toxins, and DOX are attached to the pac site. Targeting peptides can be added to cargo‐loaded VLPs to increase selective internalization by cancer cells, fusogenic peptides can be added to promote endosomal escape of internalized VLPs, and PEG can be added to minimize nonspecific interactions and the humoral immune response to coat protein. Using a heterobifunctional cross‐linker with a PEG spacer arm, peptides having a C‐terminal cysteine residue are attached to lysine residues (red) on the outer capsid surface (yellow). B) Internalization of Alexa Fluor 555‐labeled SP94‐targeted VLPs (red) occurs via an endocytotic pathway, as evidenced by their punctate presence within HCC. The positive Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) between SP94‐targeted VLPs and Alexa Fluor 488‐labeled LAMP‐1 (green) as well as the near‐zero R‐value between SP94‐targeted VLPs and Alexa Fluor 647‐labeled Rab11a (white), a marker for recycling endosomes, show that SP94‐targeted VLPs are directed to lysosomes upon endocytosis by HCC. C) Hep3B cells were treated to SP94‐targeted VLPs (red) for 15 min or 1 h. In (i) and (iii), VLPs were co‐modified with SP94 peptide and H5WYG peptide, while in (ii) and (iv), VLPs were co‐modified with SP94 peptide alone. VLPs co‐modified with the SP94 targeting peptide and the H5WYG fusogenic peptide get disseminated in the cytoplasm of Hep3B cells after endocytosis, but VLPs changed with just SP94 remain in endosomes. Alexa Fluor 555 was used to label VLPs. Hoechst 33342 and CellTracker Green CMDFA were used to label the cells. Scale bars = 10 µm. Reproduced with permission.[ 101 ] Copyright 2011, Elsevier. Abbreviation: HCC: Human hepatocellular carcinoma; LAMP‐1: Lysosomal‐associated membrane protein 1; Rab11a: Ras‐related protein Rab‐11A.

5.2. MSN‐SH

VLPs have recently been used as an effective vector for delivering the CRISPR/‐Cas9 system (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats [CRISPR]‐associated protein 9 [Cas9]) for cancer gene therapy. In this study, researchers used a virus‐like nanoparticle (VLN) as a flexible nanoplatform for co‐delivering the CRISPR/Cas9 system and biomolecule for effective tumor therapy. In order to construct VLN, axitinib, a small molecule of tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is loaded into the pores of surface‐thiolated mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN‐SH) and the pores were then sealed using disulfide bonds to link ribonucleoprotein (RNP) to MSN‐SH (RMSN). Afterward, VLN was produced by encapsulating RMSN with a lipid layer containing PEG2000‐DSPE, which prevents enzymatic degradation of RNP in the physiological condition and extends half‐life in the circulation. VLN releases RNPs and small molecules in response to the reduced microenvironment inside tumor cells, leading in the combinatorial modulation of several signaling paths (Figure 11 ).[ 102 ]

Figure 11.

Schematic illustration of axitinib‐loaded VLN synthesis. A) Axitinib and the CRISPR/Cas9 system are loaded into the mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN)‐based core, which is further enclosed with a lipid shell in VLN's core–shell structure. B) In response to the reductive microenvironment, VLN releases the CRISPR/Cas9 system and drug. Reproduced with permission.[ 102 ] Copyright 2020, Elsevier. Abbreviation: GSH: Glutathione; Axi: Axitinib; VLN: Virus‐like nanoparticle.

A CRISPR/Cas9 with a single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting the programmed death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1) encoding gene (sgPD‐L1) was used to disrupt the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and increase the effectiveness of VLN in cancer therapy.

In vitro and in vivo experiments have shown that the tumor growth was effectively suppressed in cancer cells using VLN by disruption of pathway of the PD‐1/PD‐L1 and reinvigoration of exhausted T cells. Additionally, VLN was capable of delivering Axi to the tumor, leading in a reduction in the number of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the tumor microenvironment. T‐cell‐mediated anti‐tumor immunity was increased when immunosuppressive Tregs were reduced, and as a result, tumor development was inhibited.

By delivering Cas9 protein, sgRNA, and small molecule, VLN exhibited synergistic control of multiple pathways in tumors, demonstrating VLN's potential as a generic platform for the development of advanced combination therapies against malignant tumors (Figure 12 ). These results show that VLN is able to deliver gene/drug systems to tumor tissue more efficiently, and provide a solid basis for efficient gene editing in tumors and reduction of side effects in normal tissues.[ 102 ]

Figure 12.

The VLN‐sgPD‐L1 anti‐tumor activity in melanoma mice model. A) Administration timelines and procedures for various formulations. B) Tumor growth curves in PBS, VLN‐sg (carrying a sgRNA without PD‐L1 targeting sequence), free RNP‐sgPD‐L1, RMSN‐sgPD‐L1, and VLN‐sgPD‐L1 mice. C) Survival curves for mice received several formulations. D) Body weight changes in mice after treatment with various formulations. E) Analysis of PD‐L1 immunofluorescence in each treatment group. Alex Fluor 594 (red) and DAPI (blue) were used to counterstain PD‐L1 and nuclei, respectively. Scale bars = 100 m. F) Levels of IFN‐ʏ and TNF‐α in mice treated with various formulations. Representative plots (G) and quantitative analysis (H) of CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes infiltration in treated tumors assessed by flow cytometry (gated on CD45+ CD3+ cells). I) Immunofluorescence image of the tumors revealed infiltrating CD4+ T cells (red) and infiltrated CD8+ T cells (green). The nuclei of the cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 100 µm. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. The significant levels are shown as **p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. Reproduced with permission.[ 102 ] Copyright 2020, Elsevier. Abbreviation: VLN; Virus‐like nanoparticle; sgRNA: Single guide RNA; PBS: Phosphate buffered saline; PDL‐1: Programmed death‐ ligand‐1; INF: Interferons; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; RNP: Ribonucleoprotein; MSN: Mrsoporous silica nanoparticle.

5.3. PhMV

The use of nanoparticle‐based delivery vehicles to control drug release might improve chemotherapy safety and effectiveness. Using a combination of chemical conjugation and stacking interactions the prodrug 6‐maleimidocaproyl‐hydrazone DOXDOX‐EMCH) was loaded into the empty core of VLPs derived from Physalis mottle virus (PhMV). After cellular absorption, an acid‐sensitive hydrazine linker present in the DOX‐EMCH prodrug releases the doxorubicin in the slightly acidic tumor microenvironment or acidic endosomal/lysosomal compartments. To reduce nonspecific absorption and promote biocompatibility, the exterior surface of VLP was coated with polyethylene glycol (PEG). The DOX‐EMCH molecule's pH‐sensitive hydrazone bond permits DOX to be released in the tumor microenvironment or after absorption into the endosome/lysosome. After incubation at 37 °C for 48 h, the higher DOX was released at pH 5.2 (67%) than at pH 6.4. While quicker and efficient DOX release from the DOX‐PhMV‐PEG particles was observed under conditions that mimicked the tumor microenvironment or endosome/lysosome, the cargo was retained during normal circulation. On the other hand, the release profile plateaued after 48 h at pH 7.4 with less than 10% of the drug released. According to in vitro analysis, the free DOX was more effectively absorbed into tumor cells than the VLPs. In fact, PhMV‐based VLPs are greatly biocompatible, with elongated circulation times and a preference to accumulate in tumors. PhMV‐based VLPs could offer a greatly appropriate system in order to develop effective drug delivery system formulations. The anti‐tumor activity of VLPs was evaluated against a breast cancer (MDA‐MB‐231) xenograft tumor model in NCr nude mice. Results show that the tumor sizes in the control group grew rapidly, whereas in the PhMV‐PEG particle control group, tumor development was considerably inhibited. This could suggest that VLPs have potential to stimulate an innate immune response in the tumor microenvironment independently. In mice treated with DOX‐PhMV‐PEG particles, tumor growth was significantly inhibited and in some cases completely disappeared, indicating that the particles aggregated in the tumors released DOX on demand, which destroyed the tumor cells with high efficacy.[ 98 ]

5.4. HBc‐Virus‐Like Particle

Epilepsy is characterized by a transitory brain malfunction caused by a rapid aberrant discharge of excitatory neurons in the brain. 30% of epilepsy patients acquire antiepileptic drug resistance and experience uncontrollable seizures, referred to as refractory epilepsy.[ 103 ] Epilepsy refractory to antiepileptic drugs is linked to the formation of the blood–brain barrier, which prevents them from entering the brain.[ 101 ] Protein nanocages (NCs) have been discussed extensively as a viable drug delivery technique for clinical treatment because of their biocompatibility and biodegradability. In a series of protein NCs, the hepatitis B core protein (HBc) has been extensively studied for biomedical applications. HBc can be synthesized and self‐assembled using well‐known expression techniques, as well as modified using various peptides.[ 104 ] As a delivery vehicle, an HBc VLP might provide several benefits, including preventing drug deterioration and improving drug delivery to specific sites. In addition, genetic engineering can transform HBc VLPs into hollow VLPs that lack undesired viral genes and hence are replication‐deficient and non‐infectious. Furthermore, brain tumor targeting efficacy of HBc VLP may also be improved by modification of various peptides.

In order to facilitate the delivery of the epileptic drug, phenytoin, to the brain, Zhao et al. successfully developed a delivery system by inserting a brain targeting TGN peptide in to the nanocage of the HBc protein. The results from this study in pilocarpine‐induced epilepsy models demonstrate 2.4‐fold increase in selective brain tissue target and nearly 100 times improvement in the antiepileptic efficiency using this nanocage. Both in vivo mice and in vitro human neural cell studies established that TGN‐Hepatitis B core (TGN‐HBc) nanocages shows low cytotoxicity and high penetrating ability. Rather than disrupting the blood brain barrier, these effects are done by facilitating the brain target peptide TGN (Figure 13 ). The result showed higher PHT accumulation in the brains of TGN‐HBc animals and the PTH concentration stretched about 92 ng g−1 in brain 1 h after the injection. These outcomes also revealed strong signal distribution in the liver and kidney, which showed that TGN‐HBc nanocages have major brain targeting efficiency.[ 105 ]

Figure 13.

TGN‐HBc nanocages efficiently target the brain. A) In vivo imaging of Cy5.5‐labeled TGN‐HBc nanocages in the brain and HBc nanocages as a control at various time points. B) The fluorescence intensity of the brain region was used to quantify TGN‐HBc nanocages and HBc nanocages. C) The ex vivo brain images and fluorescence data from two mentioned groups (i) and the rate of fluorescence retention in brains of each group (ii). *p ˂ 0.05, **p ˂ 0.01). (n = 3). Reproduced with permission.[ 105 ] Copyright 2020, Elsevier. Abbrevition: HBc: Hepatitis B core.

A dual‐targeted delivery system containing TGN brain targeting peptide and tumor vascular preferred ligand RGD was also developed using HBc protein–VLP delivery system for glioblastoma targeting. Yes‐associated protein (YAP) acts as a transcriptional co‐activator of the Hippo Pathway, which regulates cell proliferation and death. YAP was recognized in chicken as a binding protein of nonreceptor tyrosine kinase YES1. The interaction is arbitrated through a proline‐rich region of YAP and the SH3 domain of YES1.[ 106 ] Glioma cell invasion and migration may be enhanced by overexpression of YAP. The incorporation of YAP siRNA into a dual‐targeted delivery system has the potential to cause apoptosis in tumor cells and prevent tumor invasion. Given the limited effects of siRNA, paclitaxel (PTX) co‐packaging could have some therapeutic potential. Although PTX is widely used as an anticancer agent, a limited amount of it reaches the brain. As a result, it has restricted anti‐tumor activity while having significant adverse effects at high doses. Based on these data, the particles of PTX/siRNA@TGN/RGD‐HBc VLPs were created by packaging the delivery system with PTX and YAP siRNA. The drug loading content of 23.28 ± 2.24% and an encapsulating efficiency of 76.09 ± 10.44% were reported for PTX@TGN/RGD‐VLP system. After 24 h at room temperature and pH 7.4, ≈40% of the PTX was released. The combination of chemotherapy and gene therapy showed potent synergistic anti‐tumor effects by increasing the apoptosis rate and inhibiting tumor invasion with limited cytotoxicity. Combination treatment using several approaches, including several targets and various therapeutic agents, could have beneficial therapeutic efficacy for invasive glioblastoma. These results showed that the use of carrier was nontoxic for this application and it could be used in a variety of drug delivery applications in the future.[ 107 ]

5.5. JgCSMV

Johnson grass chlorotic stripe mosaic virus (JgCSMV) empty shells were investigated as VLP nanoparticles for drug delivery application. In a recent study, JgCSMV‐VLPs were introduced as a cheaper and safer platform for the large‐scale nanoparticle synthesis. A recombinant VLPs of JgCSMV were produced by cloning of this virus coat protein (CP) gene into pBI121 vector and then introduced into Agrobacterium rhizogenes, which was explored as a nano‐container for DOX for administrating into human cells. In a tobacco hairy‐root expression system, Alemzadeh and colleagues reported that the in the absence of viral RNA, the JgCSMV‐CP coat can be expressed and in vivo test also confirms the assembling of recombinant protein into empty shells of VLPs.[ 108 ] Researchers have examined the possibilities of employing the empty shells of icosahedral JgCSMV as carriers for drug delivery in this context. The particle form appeared to be compact at low pH, but swelling and opening of pores occurred as the pH increased due to structural transition. DOX loading inside the VLP core may benefit from porous structures and reversible mechanisms. The DOX can be encapsulated within the JgCSMV‐VLP by diffusing via the pores and electrostatically interact with glutamic acid and aspartic acid residues present inside the capsids. According to the results of this investigation, each VLP can encapsulate an average of 2500 DOX molecules.[ 108 ]

5.6. Qβ

VLPs have attracted widespread attention in the nanomedicine field as carriers of various agents with different molecular functions with the possibility for precise cellular delivery, inspired by natural viruses' innate polyvalency and tissue tropism.[ 109 ] The VLPs, which are derived from bacteriophage Qß (Qubevirus durum) have been extensively manipulated in order to be used in cell targeting, imaging, and immunology. In this regard, Crooke and colleagues developed a VLP‐macrolide conjugate platform for intracellular drug delivery in the situation of pulmonary infections. This study established the ability of macrolides to guide a VLP to the lungs, most likely by selective accumulation in pulmonary macrophages. Among all the ligands examined, azithromycin prompted the greatest macrophage uptake in vitro, and uptake was shown to be dependent on both the macrolide's orientation and density on the particle surface. In mice, azithromycin conjugation guided VLPs to the lungs, where they accumulated significantly within 2 h after systemic injection.

These findings indicate that this novel class of bio‐conjugates may represent an effective technique for pulmonary infection drug delivery.[ 110 ]

5.7. CPMV

The new treatment used by researchers designing Cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV) nanoparticles for human cancer therapy is eCPMV. eCPMV preserves all of CPMV's well‐known capsid proteinaceous structural properties, but without the RNA genomes. As a result, eCPMV is non‐replicative and thus non‐infectious in humans.[ 111 ] CPMVs can hold molecules in their protein capsids for long periods, distinguish between cancerous and normal cells, be picked up and collect within tumor cells, and then release their cargo biomolecules until internalized.[ 112 ] Because of these characteristics, CPMVs are very good at supplying toxic substances to tumor cells while missing the normal host cells, making them potent pharmacological vectors in cancer therapy.

Efficient tumor entry, tumor cell internalization, and affecting of the loaded CPMVs to the endolysosome were achieved using CPMVs covalently loaded with the chemotherapeutic agent's DOX, but cargo release was delayed before the internalized CPMV particles were steadily metabolized by the tumor cells for just a few days.[ 113 ] DOX was covalently conjugated using the EDC/NHS to the carboxylate groups of the native CPMV (Figure 14A) to produce CPMV‐DOX, or amide bond was created using an eight‐atom spacer arm cross‐linker with a disulfide bond with amine group on the surface of CPMV to produce CPMV‐SS‐DOX (Figure 14B).

Figure 14.

The conjugation process for preparing A) CPMV‐DOX and B) CPMV‐SS‐DOX. C) Aqueous suspensions of wild‐type CPMV (a) and CPMV‐DOX (b) are depicted schematically. D) Time course study using confocal scanning microscopy showing cellular uptake of CPMV (Green: CPMV, red: Endolysosomes, blue: nuclei). Reproduced with permission.[ 113 ] Copyright 2013, American Chemical Society. Abbreviation: CPMV: Cowpea mosaic virus; DOX: Doxorubicin.

Tissue culture methods were used to assess the cell viability and drug effectiveness of CPMV‐SS‐DOX and CPMV‐DOX. CPMV nanoparticles in their natural state are biocompatible and do not seem to be cytotoxic (Figure 14). The cell‐killing ability of CPMV‐DOX conjugates was demonstrated. When analyzing CPMV‐SS‐DOX and CPMV‐DOX, they discovered major variations in cellular toxicity trends. CPMV‐SS‐DOX's effectiveness was similar to that of the free drug. Information shows that when DOX is bonded to CPMV through a disulfide bridge, the effective dose remains unchanged. This is due to a disulfide‐bridge dissociation in the culture medium enables doxorubicin from CPMV to be released before cellular uptake. Therefore, CPMV‐SS‐DOX resembles free DOX in its operation. However, targeting techniques may be used to enhance any design additionally. Cardiotoxicity is caused by the free drug, which limits its therapeutic use. Conjugation of a receptor‐targeted CPMV nanoparticle with a covalent amide bond is required to have tissue‐specific delivery benefits.

In general, as compared to free DOX, the CPMV‐DOX compound is a more cytotoxic cause against HeLa cells at low dosages, while the cytotoxic impact is delayed as the concentration is increased. Without the usage of cell‐specific targeting agents on the capsid, the CPMV nanoparticles are steered to the endolysosomal compartment of the cells. After all, the platform technology can be further developed to add targeting ligands that fit a patient's clinical profile, paving the way for the advancement of customized cancer medicines.[ 113 ]

5.8. TMV

Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) nanoparticles with self‐replicating properties have frequently been applied in order to drug delivery; though, when recombinantly released, TMV proteins can combine into several states, such as simple monomers and micron‐long helical rods. To supplement the existing spherical‐ and rod‐shaped protein materials, it would be beneficial to create a new and secure morphology.

Disk‐shaped nanoparticles are an under‐appreciated but theoretically fascinating morphology for drug delivery. Disks may have an advantage over other morphologies in that they may fit into narrow spaces and have greater penetration into tumor cells.

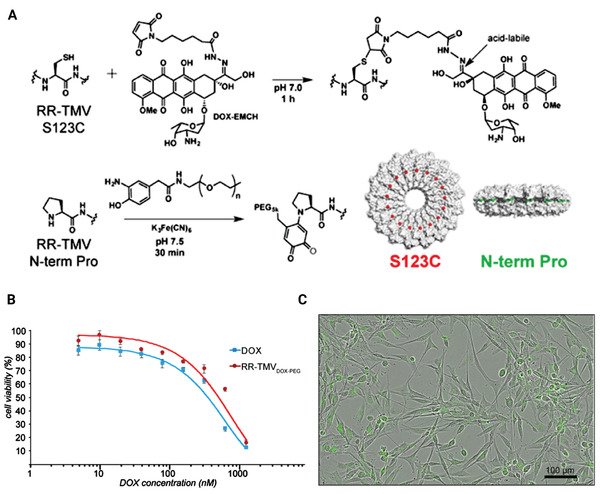

They present a TMV dual Arg mutant (RR‐TMV) which assembles into dual disks that remain similar throughout environmental changes. Further, DOX conjugated with these disks at non‐native cysteine and N‐terminus of PEG for drug delivery, and cell absorption and toxicity were tested.

Protein‐based nanoparticles are often bonded to PEG polymers to minimize immunogenicity and improve serum constancy as they are designed in order to drug delivery. Researchers tried to use these robust RR‐TMV disks for drug distribution applications now that they had them. DOX, a commonly applied drug in order to nanoscale drug delivery, was compressed onto the hydrazide maleimide linker EMCH and conjugated to the RR‐TMV disks at the S123C location through maleimide chemistry.[ 114 , 115 ] The PDA‐coated TMV exhibited a shorter plasma circulation time and wider distribution to various organs, such as liver, spleen, and lungs than uncoated TMV particles. Though, the ELISA test showed that PDA‐coated particles connect two times lesser to anti‐TMV antibodies removed through particle injection than uncoated particles, proposing that the PDA coat allows elusion from systemic antibody surveillance. TMV‐PDA particles were also cleared from organs after 7 days. The slower tissue clearance of the coated particles causes them appropriate in order to theranostic applications.[ 116 ]

The RR‐TMVDOX‐ PEG conjugates' drug delivery ability was then tested in vitro. When DOX‐treated and RR‐TMVDOX‐PEG‐treated cells were compared to cell controls after 3 weeks of incubation, substantial cell death was detected (Figure 15 ). The relaxed‐release profile of the hydrazone bond between EMCH and DOX is most likely responsible for the disparity in cell viability bends among RR‐TMVDOX‐PEG and DOX alone. As a result, RR‐TMV disks offer an exciting new nanostructure that will add to the form catalog of protein‐based biomaterials in order to in vitro drug delivery. Upcoming research will concentrate on understanding the RR‐TMV disks' special assembly state in addition to their biodistribution and transmission efficacies.[ 117 ]

Figure 15.

RR‐TMV DOX‐PEG conjugates are characterized. A) RR‐TMV disks were loaded with EMCH DOX at their S123C positions and aminophenolPEG5k at their N‐terminal prolines. B) Significant cell death observed after 72 h of incubation of U87MG glioblastoma cells with varying concentrations of RR‐TMVDOX‑PEG conjugates. C) U87MG cell uptake of RR‐TMVDOX‑PEG conjugates at 48 h. Reproduced with permission.[ 117 ] Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. Abbreviation: DOX: Doxorubicin; TMV: Tobacco mosaic virus; PEG: Polyethylene glycol.

5.9. CCMV

For effective drug delivery in cancer cells, ligands bioconjugation was used to create targeted nano‐delivery carriers from genetically engineered cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV) capsid. To achieve effective in vitro assembly lacking the usual payload, the capsid's RNA‐binding and hexamer‐forming domains were selectively removed by genetic engineering. To improve the stabilization, drug packing, and continuous release of a drug, the cavity of the nano‐scaffold was filled with DOX covalently attached gold NPs. At a pH of 4–8, the chimeric structure remained constant. This genetically engineered nano‐scaffold method displayed greatly detailed receptor‐mediated internalization (targeting) and high cytotoxicity toward folate receptor‐positive MCF7 cell lines. The current device could provide a customizable nano‐scaffold‐based framework for the development of cancer chemotherapeutics. In vitro assembly of genetically engineered CCMV capsid on DOX conjugated AuNPs was used to create a chimeric multipurpose drug delivery system, as seen in Figure 16 . The modified capsid proteins were made in Escherichia coli (E. coli) and bioconjugated with folic acid and DOX in the purposeful form separately. In vitro processing was applied to encapsidate DOX‐doped AuNPs in the inner cavity of these functionalized capsid proteins to improve the delivery vehicle. On MCF7 cells, the cytotoxicity of DOX conjugated reformed delivery carriers (GNPdox+, FADDSdox+, FA+DDSdox+, and GNPdox+:FA+DDS dox+) was compared to that of equimolar pure doxorubicin. Based on the free DOX concentration, 50–60% cellular cytotoxicity was detected after 48 h and 80–90% after 72 h. Pure DOX, on the other hand, demonstrated very low cytotoxicity up and about to 4.0 µm. The synthesis of targeted bioengineered DOX delivery vehicles to FR expressed cancer cells is demonstrated in this research (MCF7). Assembly of genetically modified and ligands conjugated, capsid proteins of CCMV developed the vehicle. To improve drug loading capability and boost drug efficiency, DOX conjugated AuNPs are placed in the internal cavity of these vehicles. During the in vitro release trial, this vehicle demonstrated selective DOX release in cellular lysosome mimicking situations. In FR‐positive cells, these carriers demonstrated uptake and cytotoxicity (MCF7).[ 118 ]

Figure 16.

A) The development of the chimeric drug delivery mechanism is depicted schematically. The CCMV virus's customized capsid proteins were folic acid, dye, and DOX separately. The right combination of these ligand bioconjugated capsids was constructed with DOX conjugated AuNPs at its center to create nanoparticulate targeted delivery vehicles. B) Cytotoxicity of various drug delivery system formulations toward MCF7 cells by XTT Assay. Reproduced with permission.[ 118 ] Copyright 2016, Nature. Abbreviation: DOX: Doxorubicin; CCMV: Cowpea chlorotic stripe mosaic virus.

5.10. CCMV with Heparin

Heparin is a glycosaminoglycan polysaccharide commonly applied as an anticoagulant in surgical procedures cases.[ 119 ] The CCMV capsid is a highly explored VLP as it can be grown in large quantities and undergoes swelling in various ionic strengths making it a popular choice for cargo packing. They discovered that heparin‐required peptide modified CCMV capsid proteins at physiological pH levels show unique heparin binding. Based on DLS measurements and TEM representation, co‐assembly with heparin capsids showed the size of about 20 nm. These findings suggest that VLPs are promising heparin‐binding materials, particularly when the connecting is adapted to physiological conditions and after extensive hematologic studies. Capsid creation relies on the amount of encapsulated compound, and great cargo ratios limit capsid development. The HBP in issue was chosen because of its great discernment and affinity for heparin, reducing off‐target connecting in complex biological settings.[ 120 ] The SrtA‐based approach was used to conjugate HBP to the CP N‐terminus. Finally, they demonstrated that CCMV capsid proteins functionalized with a heparin‐binding peptide at physiological pHs display unique heparin binding. Due to DLS and TEM classification, co‐assembly with heparin formed T = 1 capsids. The capsid formation was further confirmed by fast protein liquid chromatography findings, which showed a heparin concentration influence on capsid development. These findings suggest that VLPs are hopeful heparin‐binding materials under physiological relevant conditions.[ 121 ]

5.11. PhMV

Physalis mottle virus (PhMV)‐VLPs were genetically modified to show diagnostic and immunogenic epitopes in previous studies.[ 122 ] The surface of PhMV was investigated, and protocols for detailed functionalization of these surfaces with various agents were established. PhMV was modified with dyes, medications, and photosensitizers using a library of functionalization procedures, such as conjugation and noncovalent binding. Flow cytometry and confocal microscopy were used to classify the functionalized PhMV nanoparticles, and their cytotoxic efficiency was checked in a variety of cells.[ 122 ]

The VLPs were packed with fluorescein, rhodamine B, MTX dihydrochloride, or DOX hydrochloride. The VLPs were incubated overnight at room temperature with a molar extra of cargo molecules per atom. Since the virus is primarily stabilized through protein–protein interactions, drug encapsulation by particle disassembly and assembly is not feasible in the case of PhMV. As a result, they devised an infusion procedure for loading cargo into the VLPs.

In this study, they exposed MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells and ovarian cancer to a variety of concentrations of free DOX and equal concentrations of DOX in the DOX‐PhMV particles to see whether DOX maintained its cytotoxic function in the particles. Since DOX chemotherapy is applied to the first‐line and adjuvant care in women with breast or ovarian cancer, they preferred breast cancer and ovarian. Increased bacterial fermentation capability could be used to scale up the output of PhMV‐based VLPs, but expression in plants could achieve much greater scalability. PhMV does not replicate in mammals but is compatible and degradable as opposed to mammalian virus‐based structures, providing an extra layer of protection. The surface of PhMV particles will be decorated with shielding molecules to avoid clearance or targeting ligands to guide the particles to particular tissues and cells in future studies.[ 122 ]

5.12. MrNV

Hyperthermia therapy is a method of cancer treatment that involves exposing cancer patients' tumor tissues or other body parts to various temperatures.[ 123 ] Macrobrachium rosenbergii nodavirus (MrNV) is an icosahedral virus with several copies of the viral capsid protein, where each capsid contains polypeptide of 371 amino‐acids. In E. coli, the chimeric capsid protein encapsidates RNA molecules by self‐assembling into a VLP. MrNVLP is the name of the VLP.[ 124 ]

DOX is extremely toxic to healthy cells, particularly those in the cardiovascular system. As a result, a new drug delivery mechanism that can target DOX to targeted cells while having fewer side effects on normal cells is highly demanded. A DOX delivery system was developed based on a new thermally sensitive carrier based on MrNVLP. In this research, Folic acid ‐MrNVLP‐DOX (FA‐MrNVLP‐DOX) (Figure 17A), an FA‐conjugated MrNVLP filled with DOX, which is rich in HT‐29 cells and DOX is released at 43 °C. This study's multifunctional nanomaterial displayed precisely targeted distribution and thermally regulated release of DOX. FA‐MrNVLP‐DOX and MrNVLP‐DOX had entrapment efficiency of 5.06 ± 0.29% and 5.47 ± 0.13%, respectively (Figure 17B). MrNVLP‐DOX and FA‐MrNVLP‐DOX had loading performance of 2.1 ± 0.1% and 2.3 ± 0.2%, respectively. After 12 h at 37 °C, nearly half of the DOX was released from the nanoparticles, and the device only reached a full overall release of about 80% after 3 days. At 43 °C, however, roughly half of the DOX was released from the nanoparticles, and nearly all of the Dox was released within 1 day (Figure 17C). They developed a significant method in order to directly load DOX into MrNVLP in this study. FA conjugation to the VLP improved cellular uptake and aggregation of DOX in FR‐rich HT29. Furthermore, FA‐MrNVLP‐DOX improved DOX toxicity and apoptotic activity in HT29 cells. Other tumor‐targeting ligands could be expressed on MrNVLP using suitable cross‐linkers in addition to FA. MrNVLP's long‐term release profile and virtually complete release of all the loaded DOX at hyperthermia temperatures show that it may be a good choice for a thermally sensitive drug delivery system (Figure 17).[ 125 ] Table 2 lists some genetically engineered viruses that are employed in the delivery of drugs for treatment of different diseases.

Figure 17.

A) Focusing on the VLPs of Macrobrachium rosenbergii (M. rosenbergii) nodavirus, a schematic image of a drug delivery mechanism is seen (MrNVLP). Applying EDC and N‐hydroxysulfo‐succinimide, carboxylic acid groups of folic acid were conjugated with the amines of lysine residues found on the surface of MrNVLP (sulfo‐NHS). Via associations with the RNA molecules encapsidated within the nanoparticles, DOX biomolecules were injected into the cavity of FA‐conjugated MrNVLP. B) UV–vis spectra of the virus‐like particle of M. rosenbergii nodavirus (MrNVLP), free doxorubicin (DOX), DOX‐loaded MrNVLP (MrNv‐DOX), and DOX‐loaded‐and‐folic acid (FA)‐conjugated MrNVLP (FA‐MrNVLP‐DOX). C) Drug release profiles of DOX, MrNVLP‐DOX, and FA‐MrNVLP‐DOX for the first 18 h at 37 and 43 °C. Reproduced with permission.[ 125 ] Copyright 2019, Nature. Abbreviation: FA: Folic acid; EDC: 1‐ethyl‐3‐(3‐dimethyl aminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride; Sulfo‐NHS: N‐hydroxysulfosuccinimide; DOX: Doxorubicin.

Table 2.

Some examples of genetically engineered viral targeted for drug delivery applications

| Viral | Shape | Family | Drug | Disease | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P22‐SP | Icosahedral | Podoviridae | Ziconotide | HIV and cancer | [129] |

| P22 WB | Icosahedral | Podoviridae | Bortezomib (BTZ) | Cancer | [9] |

| tHBcAg | Icosahedral | Hepadnaviridae | Doxorubicin | Colorectal and cervical cancer | [130] |

| Reovirus | Icosahedral | Reiviridae | Doxorubicin, epirubicin, topotecan | Triple‐negative breast cancer | [131] |

| MCF7 specific fusion phage | Rode shape | Bacteriophages | Doxorubicin | Breast cancer | [132] |

5.13. P22‐SP

Ziconotide (Prialt), the first non‐opioid analgesic identified in the venom of the sea snail Conus magus, is being used to treat medical conditions in HIV and cancer patients. The peptide was encased in a viral container and administered across the BBB using a trojan horse approach, which has previously been described as a viable replacement for intrathecal injection in order to deliver ziconotide.[ 126 ]

A strategy for inducing disintegration of a nano container made from the viral capsid of the Salmonella typhimurium bacteriophage P22 is disclosed in physiologic conditions. The P22 capsid is an icosahedral lattice that self‐assembles when enough copies of the P22 scaffold protein are present.[ 127 ]

The Douglas group developed a strategy to package arbitrary gene yields into the P22 capsid shell by using standard recombination procedures to build a fusion protein including an uninformed carrier protein attached to the P22‐SP C‐terminus via a thrombin cleavage site.[ 128 ] The fluorescent proteins EGFP and mCherry, the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase D, and the HIV and cancer drug ziconotide were all loaded into the P22 capsid in this way.[ 129 ]

5.14. P22 WB